Abstract

Elimination of cerebellar granule cells early during postnatal development produces abnormal neural organization that retains immature characteristics in the adult, including innervation of each Purkinje cell by multiple climbing fibers from the inferior olive. To elucidate mechanisms underlying development of the olivocerebellar projection, we studied light-microscopic morphology of single olivocerebellar axons labeled with biotinylated dextran amine in adult rats rendered agranular by a single postnatal X-irradiation.

Each reconstructed olivocerebellar axon gave off ∼12 climbing fibers, approximately twice as many as in normal rats. Terminal arborizations of climbing fibers made irregular tufts in most areas, whereas they were arranged vertically in a few mildly affected areas. Each climbing fiber terminal arborization innervated only part of the dendritic arbor of a Purkinje cell, and multiple climbing fibers innervated a single Purkinje cell. These climbing fibers originated either from the same olivocerebellar axon (pseudomultiple innervation) or from distinct axons (true multiple innervation). Abundant non-climbing fiber thin collaterals projected to all cortical layers. Although the longitudinal pattern of the zonal olivocerebellar projection was generally observed, lateral branching, including bilateral projections, was relatively frequent.

These results suggest that the granule cell-parallel fiber system induces several important features of olivocerebellar projection: (1) organization of the climbing fiber terminal arborization tightly surrounding Purkinje cell dendrites, (2) elimination of pseudo- and true multiple innervations establishing one-to-one innervation, (3) retraction of non-climbing fiber thin collaterals from the molecular layer, and (4) probable refinement of the longitudinal projection domains by removing aberrant transverse branches.

Keywords: Purkinje cell, granule cell, parallel fiber, synapse elimination, x-rays, development, neuroanatomy, nervous system abnormality

The structure of the cerebellar cortex in the normal adult animal is characterized by the regular organization of local circuits (Ramón y Cajal, 1911) and by the longitudinal and lateral compartmentalizations determined by olivocerebellar and corticonuclear projections (Groenewegen and Voogd, 1977; Buisseret-Delmas and Angaut, 1993) and biochemical markers (Eisenman and Hawkes, 1993; Bailly et al., 1995; Herrup and Kuemerle, 1997). In the cerebellar cortex in normal adult animals, individual climbing fibers, the distal portion of olivocerebellar axons (Sugihara et al., 1999), form nonconverging one-to-one innervation on single Purkinje cells with their dense terminal arborization (Eccles et al., 1966; Palay and Chan-Palay, 1974; Rossi et al., 1991).

X-irradiation at newborn periods is a standard experimental technique to produce a granuloprival cerebellum (Bailly et al., 1996). This treatment prevents proliferation of precursors in the external germinal layer, producing cerebellar cortex atrophy with several immature characteristics at adulthood such as hypoplastic granular and molecular layers and multilayered Purkinje cells (Altman and Anderson, 1972;Crepel et al., 1976b; Altman and Bayer, 1997). Among other abnormalities in the olivocerebellar projection in X-irradiated rats is the multiple innervation of Purkinje cells by climbing fibers, demonstrated electrophysiologically (Woodward et al., 1974; Crepel et al., 1976b, 1981; Puro and Woodward, 1977c; Crepel and Delhaye-Bouchaud, 1979; Benoit et al., 1984; Mariani et al., 1987,1990; Fuhrman et al., 1994, 1995). Multiple innervation of Purkinje cells by climbing fibers was originally described in newborn rats (Crepel et al., 1976a; Puro and Woodward, 1977a; Mariani and Changeux 1981a,b; Mariani, 1983), but multiple innervation in adulthood has also been demonstrated, along with granule cell loss and Purkinje cell abnormalities, in the cerebellum of several mutants includingweaver, staggerer, and reeler (Crepel and Mariani, 1976; Puro and Woodward, 1977b; Mariani, 1982) and of ferrets after viral infection (Benoit et al., 1987). Mutant adult mice deficient in molecules of postsynaptic signaling cascades exhibit moderate climbing fiber redundancy with loss of parallel fiber–Purkinje cell synapses (GluRδ2 mutant, Kashiwabuchi et al., 1995) or without obvious granule cell-related abnormalities (the other cases studied, Kano et al., 1995, 1997, 1998; Offermanns et al., 1997;Watase et al., 1998).

Significant structural abnormalities have been reported in the granuloprival cerebellum, including axosomatic climbing fiber synapses on Purkinje cells and aberrant development of mossy fibers, Purkinje cells, and Golgi cell dendrites (Altman and Anderson, 1972;Llinás et al., 1973; Crepel et al., 1976b; Sotelo, 1977; Bailly et al., 1990, 1998). The morphology of climbing fibers multiply innervating a single Purkinje cell has been described recently in the cerebellum of rats with mild granule cell loss induced pharmacologically (Bravin et al., 1995; Zagrebelsky and Rossi, 1999), but the structural fate of olivocerebellar axon terminals and projection patterns in the granuloprival cerebella are not known.

The morphology of individual olivocerebellar axons labeled with biotinylated dextran amine (BDA) is detailed in X-irradiated rats in this study. Abnormal aspects of their climbing fiber and non-climbing fiber terminations are analyzed, and mechanisms underlying morphogenesis of the olivocerebellar projection are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experiments were performed on three irradiated adult Wistar rats, three control littermates, and another control adult Wistar rat (for retrograde labeling of Purkinje cells). The body weights of the irradiated and control animals were 128–290 and 277–530 gm, respectively, at the date of the tracer injections. No significant changes in the body weight were observed during the survival period of 8 days. Surgery and animal care conformed to The Principles of Laboratory Animal Care (National Institutes of Health publication number 85–23, revised in 1985) and also to Guiding Principles for the Care and Use of Animals in the Field of Physiological Sciences (The Physiological Society of Japan, 1988), and to the guidelines established by le Comité National d'Éthique pour les Sciences de la Vie et de la Santé.

X-Irradiation. A single dose of 500 rads of x-rays was delivered to the cerebellum on postnatal day 5 as described elsewhere (Crepel et al., 1976b; Fuhrman et al., 1994; Bailly et al., 1996) in half a litter of pups. The irradiation was strictly limited to the cerebellum and subjacent brainstem with lead protection. The irradiated and nonirradiated control pups were fed normally and kept until adulthood (4.5–6 months), when they underwent tracer injections. The decrease in body weight of the irradiated animals was presumably related to the relative chronic malnutrition caused by ataxia. We assume that the anatomical findings in the irradiated rats were specific X-irradiation effects rather than results from secondary undernutrition, because undernutrition similar to or even more severe than that observed in our irradiated rats produced no significant changes in simple spike activity (Latham et al., 1982) or synapse–neuron ratios (Warren and Bedi, 1990) and no multiple innervation of Purkinje cells by climbing fibers (J. Mariani and F. Crepel, unpublished observations) in adulthood in the rat.

Surgical procedures and tracer application. Experimental procedures for tracer injection and histochemical visualization were as previously described (Sugihara et al., 1999). All rats were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (130 mg/kg, body weight) and xylazine (8 mg/kg) and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus with the head 45° nose-down. Heart rate and rectal temperature were continuously monitored. Supplemental doses of ketamine (13 mg/kg) and xylazine (1 mg/kg) were given every 30 min starting 1 hr after the initial dose and if the rat showed evidence of incomplete anesthesia, e.g., an increase of the heart rate of >20%. An electric heating pad was used to keep the rectal temperature at ∼35°C. The foramen magnum was opened, and the inferior olive was approached with glass injection pipette from the dorsal surface of the caudal medulla. BDA (catalog #D-1956; 10,000 MW; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was dissolved in saline at a concentration of 15%. A glass micropipette (tip diameter, 4 μm) was filled with this solution and inserted into the inferior olive. The field potential recorded from the pipette was monitored to locate the inferior olive by its synchronous and rhythmical spontaneous activity (Sugihara et al., 1995). Pressure injections (0.01–0.05 μl) were made in two to four points in the right inferior olive. Pipettes were left in situ for 5 min after the pressure injection. For retrograde labeling of Purkinje cells, BDA was injected into the right fastigial and interposed cerebellar nuclei (0.2 μl) through a hole made in the right occipital bone after BDA injection into the inferior olive in one irradiated and one control rat. The wound was cleaned with povidone–iodine, and antibiotics (cefmetazole) were applied to the wound before suturing.

Fixation and histochemistry. After a survival period of 8 d, the animals were deeply anesthetized with ketamine (150 mg/kg) and xylazine (12 mg/kg), and perfused through the ascending aorta. Chilled perfusate (400 ml, 4°C) containing 0.8% NaCl, 0.8% sucrose, and 0.4% glucose in 0.05 m phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, was followed by cold fixative (200 ml, 4°C) containing 5% paraformaldehyde, 1% picric acid, 0.23% NaOH, and 4% sucrose in 0.05m sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4, ∼4°C, ∼200 ml) delivered over 30 min. The cerebellum and medulla oblongata were dissected and kept in the same fixative overnight at 4°C. After rinsing in 30% sucrose in phosphate buffer (0.01 m), pH 7.4, for 6 hr, the tissue was embedded in 15% gelatin containing 25% sucrose and 0.01 m phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 (31°C), for 20 min, before hardening at 4°C. The block was kept in tanning solution containing 20% formalin, 25% sucrose, and 0.01 mphosphate buffer, pH 7.4, (4°C) for 2–3 d. Parasagittal sections of 50 μm thickness were then cut with a freezing microtome. Serial sections were collected in multicellular containers, incubated with biotinylated HRP–avidin complex (Standard ABC kit KT-4000; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and revealed with diaminobenzidine. The sections were mounted on chrome alum-gelatinized slides, dried overnight, and coverslipped with Permount. Some sections were counterstained with thionin.

Light microscopic reconstruction. Axonal trajectories of single labeled olivocerebellar axons were reconstructed from serial parasagittal sections using a three-dimensional imaging microscope (model R400; Edge Scientific Instrument, Santa Monica, CA) equipped with a camera lucida apparatus with objectives of 20, 40, 60, and 100×. Cut ends of an axon on one section were connected properly to the corresponding cut ends of the same axon on the successive sections (Shinoda et al., 1981). Some reconstructed terminal arborizations were converted into frontal and horizontal views by taking into account the depth of the labeled axons and swellings within the sagittal sections, which was read from the microscope focus dial. The nomenclature for cerebellar lobules in the normal adult rat (Larsell, 1952; Voogd, 1995) was used to designate presumably equivalent lobules in the irradiated rat. The density of Purkinje cells was measured by counting the number of Purkinje cell nuclei observed within a given square area in a section.

RESULTS

Morphology of cerebellar layers and Purkinje cells

The cerebella of X-irradiated rats were much smaller than those of control animals. The width of the cerebellum between left and right paraflocculus was 9.4–11.1 mm in irradiated rats and 13.8–15.1 mm in controls. The rostrocaudal dimension of the cerebellum measured between the apices of lobules III and IX at the midline was 3.2–3.4 mm in irradiated rats and 6.8–7.8 mm in controls. The dorsoventral extent of the cerebellum measured between lobules I and VI at the midline was 3.0–3.6 mm in irradiated rats, and 5.6–5.8 mm in controls. These differences indicated that the cerebellar volume of irradiated rats was ∼18% of the control volume. However, because the cerebellar nuclei and the deep cerebellar white matter were of nearly normal size in irradiated rats, this value underestimates the shrinkage of the cerebellar cortex.

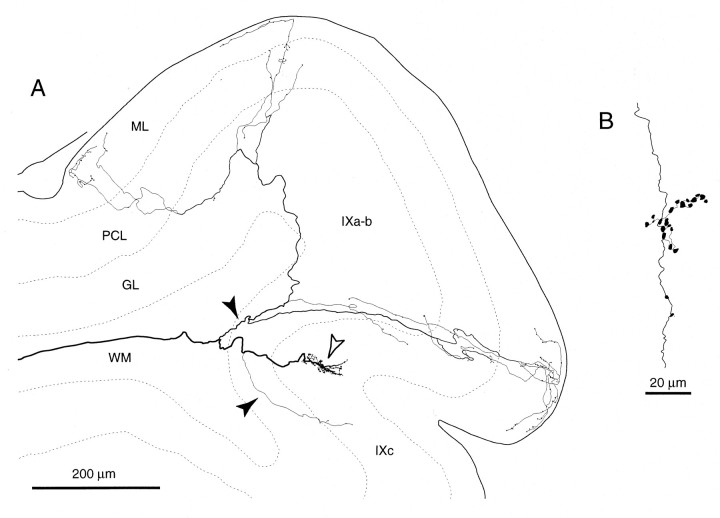

The molecular layer of irradiated rats (∼20- to 50-μm-thick) was much thinner than in control rats (200–300 μm) (Fig.1, black bars). Purkinje cell somata were scattered in a 80- to 150-μm-thick multilayer, fourfold to sixfold thicker than the Purkinje cell monolayer in the controls (Fig. 1, white bars). The granular layer in irradiated rats was thin (∼50-μm-thick) and had such a sparse cellular component that the border between the granular layer and the white matter was rather vague. These data on cerebellar atrophy in irradiated rats were in agreement with previous measurements (Mariani et al., 1987; Fuhrman et al., 1994).

Fig. 1.

Photomicrographs of counterstained sagittal sections of the cerebellar cortex of an X-irradiated rat (A) and the cerebellar cortex of a control rat (B). Tilted black bars indicate the molecular layer, and white bars indicate the Purkinje cell layer. Dots indicate the surface of the cerebellar folium of vermal lobule V. Scale bar, 200 μm.

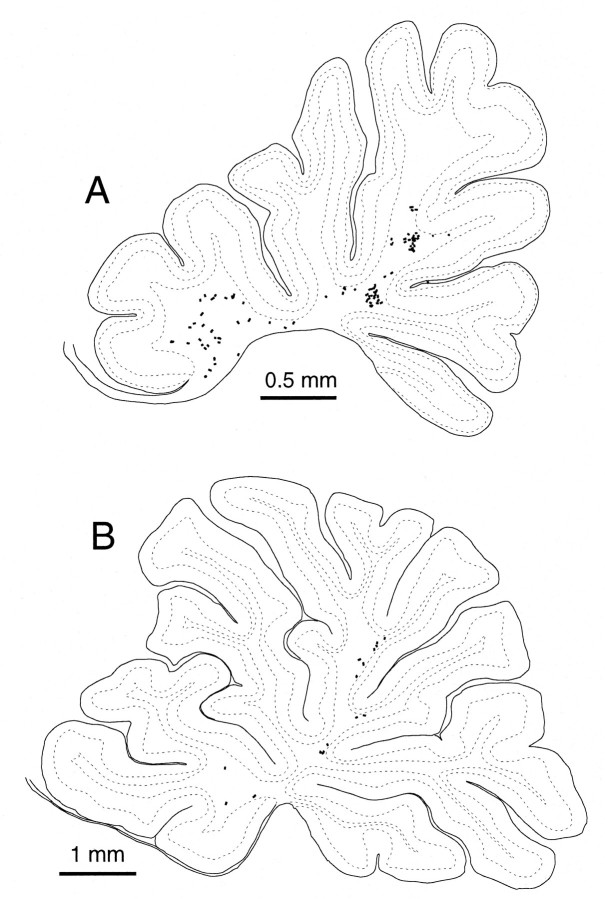

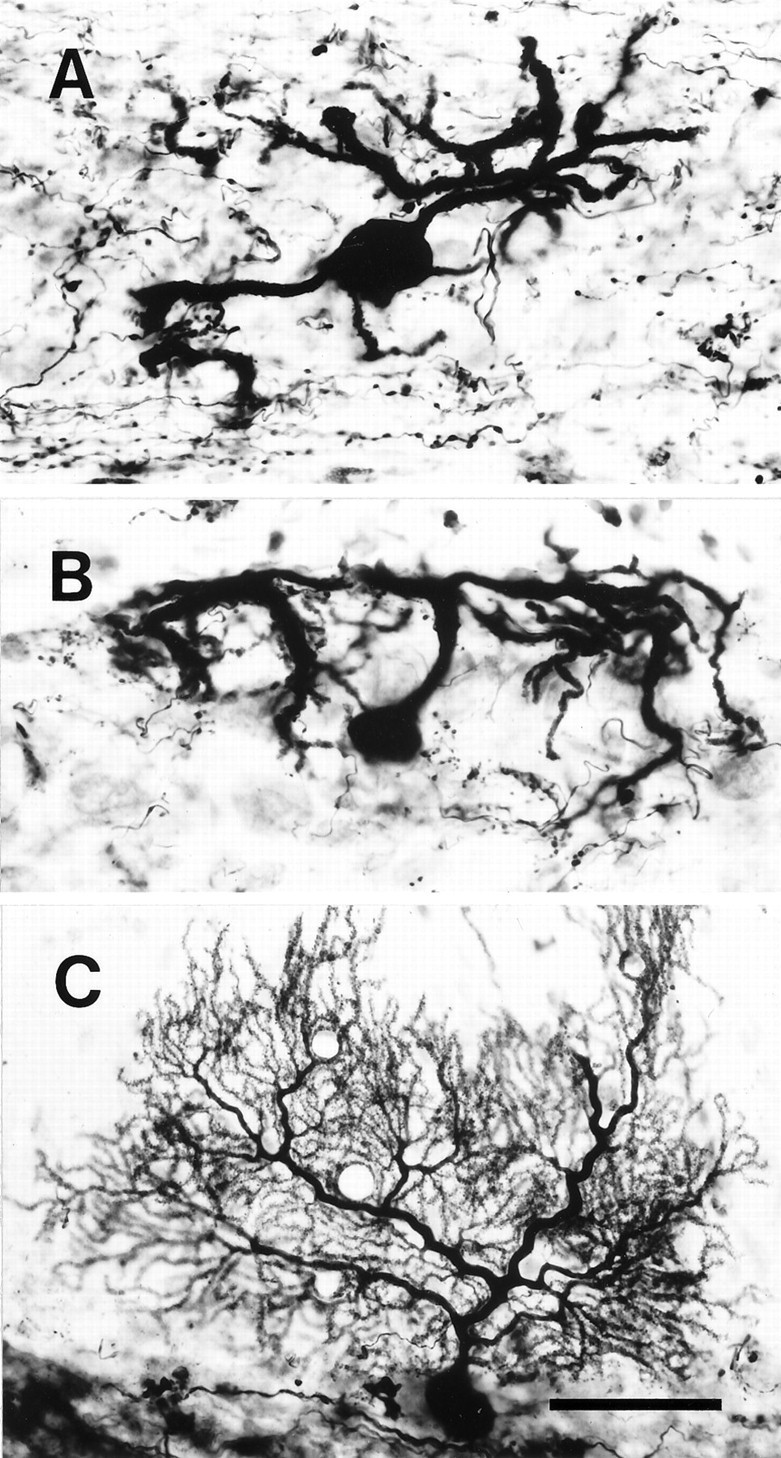

Purkinje cell morphology was examined after retrograde labeling with BDA injected into the cerebellar nuclei (Fig.2). Purkinje cells in irradiated rats had one or a few thick primary dendrites (∼30- to 60-μm-long), which ramified into secondary and tertiary dendrites. The extent of the entire dendritic arbor was ∼150–200 μm. Thin spiny dendrites, which were abundant in Purkinje cells of control rats (Fig.2C), were not present. Instead, spines were seen on some of the tertiary dendrites. The dendrites protruded in all directions (Fig.2A) and were not organized within a longitudinal plane. Some dendrites extended down into the white matter and even up to the cerebellar cortex on the opposite side of the folium (data not shown). Primary dendrites protruding upward usually had secondary dendrites that spread horizontally beneath the cortical surface (Fig.2B). These observations are similar to previous descriptions of the X-irradiated cerebellum (Altman and Anderson, 1972;Crepel et al., 1976b; Matus et al., 1990).

Fig. 2.

Photomicrographs of abnormal Purkinje cells in an irradiated rat labeled by BDA injections into the fastigial and interposed cerebellar nuclei. A, A Purkinje cell located in the middle of the Purkinje cell layer whose dendrites extended into the molecular and granular layers. B, A Purkinje cell located in the superficial Purkinje cell layer. The dendrites of this Purkinje cell spread mainly in the molecular layer. C, A Purkinje cell in a control rat. All panels show sections in vermal lobule VI. The surface of the cerebellar cortex is toward thetop in each panel. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Morphology of the mass olivocerebellar projection in the cerebellar cortex

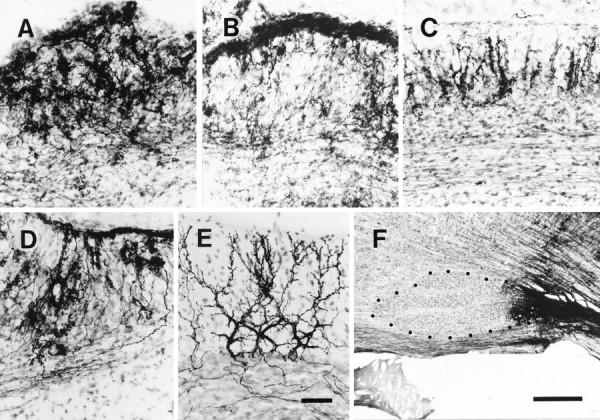

The olivocerebellar axons labeled were not evenly distributed in the cerebellar cortex but displayed a roughly multizonal distribution pattern (see below). The morphology of the mass olivocerebellar projection in irradiated rats was first examined in areas in which a majority of olivocerebellar axons were labeled. The labeled axons were identified as olivocerebellar axons because (1) they were similar to the reconstructed and identified olivocerebellar axons (see below) in all morphological characteristics, (2) the injection was centered in the inferior olive (Fig. 3F), and (3) the bundle of labeled axons originated from the inferior olive and was traced to these areas. We have classified the mass olivocerebellar projections into three morphological types, and the occurrence of these different projection types correlated with the structural abnormality of the cerebellar cortex.

Fig. 3.

Photomicrographs of irregular, superficial, and vertical configurations of the abnormal mass olivocerebellar projection in an irradiated rat. A, Irregular projection in lobule VII. B, Predominantly superficial projection with some irregular projection in lobule V. C, Predominantly vertical projection in lobule IXc. D, Mixed irregular and superficial projections in lobule VII. E, Normal olivocerebellar projection in lobule VII in a control rat.F, BDA injection centered into the caudal inferior olive in an irradiated rat from which sections for A–D were obtained. All sections shown in this figure were counterstained. Each panel (A–E) shows a sagittal section of the cerebellar cortex (the surface is toward the top) in which many olivocerebellar axons were labeled. Dotsin F indicate the contour of the rostral and central inferior olive. Scale bars: E, 50 μm (applies toA–E); F, 500 μm.

The “irregular” projection was the most frequently observed, forming an irregular plexus that was more dense in the molecular and Purkinje cell layers than in the granular layer (Fig. 3A). The plexus consisted of incoming thick axons of ∼1 μm diameter and of many thin fibers with numerous swellings. The distribution of the swellings was uneven, and resembled an irregular mosaic of spots of varying density (Fig. 3A). It was impossible to distinguish the structure of individual axons when many axons were labeled.

The “superficial” projection formed a dense plexus in the superficial molecular layer (Fig. 3B). The thickness of the plexus ranged from 15 to 30 μm. The superficial type plexus consisted of many intermingling thin axons with en passant swellings and of occasional thick axons of ∼1 μm diameter. Most of the individual axons in the plexus ran parallel to the surface of the folium.

In the cerebellar cortex with the most severe histological alterations, either the irregular projection only or a combination of the irregular and superficial projections was observed. In these areas, the molecular layer was thinner than 70 μm, the Purkinje cell layer was thicker than 50 μm, and the granular layer was hardly distinguishable from the white matter because of sparseness of the cells (Fig.3D). The superficial projection tended to occur in the deep portions of the folium. The density of Purkinje cells may also have influenced the occurrence of the two types of the olivocerebellar projections, because Purkinje cell density was moderate (30–60 neurons per 10−3mm3) in areas with irregular projections and high (50–70 neurons per 10−3mm3) in areas with superficial projections. We cannot conclude, however, what determines the extent of the superficial projection.

A third type, the “vertical” projection, was observed in areas in which the molecular layer was thicker than 50 μm, the Purkinje cell layer was thinner than 50 μm, and the granular layer (thicker than 50 μm) had a large enough population of neurons to be clearly distinguished from the white matter (Fig. 3C). Each climbing fiber terminal arborization was formed in the molecular and Purkinje cell layers, roughly vertical to the folial surface, with minimal overlap with adjacent terminal arborizations (Fig. 3C). A weak superficial-like projection in the superficial molecular layer sometimes coexisted with the vertical projection.

Among the three irradiated rats the degree of ataxia was slightly different, and the types of climbing fiber projection correlated with the severity of ataxia. In the rat with most severe ataxia, the vertical projection was seen only in lobule IXc; the second most severely affected rat had the vertical projection in caudal lobule VIII, lobules IXa-b, and IXc; and the least severely ataxic rat had these projections in caudal lobule VII, lobules VIII, IXa-b, IXc, and X. Therefore, the vertical projection was correlated with less severe damage in the cerebellar cortex than were the irregular and superficial projections. Notably, although the vertical projection was significantly different from the normal olivocerebellar projection, it resembled more closely the normal climbing fiber projection than did the irregular or superficial projections.

In control rats, each climbing fiber terminal arborization was formed within a nearly flat plane in the molecular layer, climbing along the thick dendrites of a single target Purkinje cell (Fig. 3E). Adjacent individual climbing fiber terminal arborizations were distinguishable even when many climbing fibers were labeled, because they were arranged on parallel longitudinal planes but separated from each other by a certain distance in the transverse direction. These findings were identical to previous observations on the normal adult climbing fiber projection (Ram-n y Cajal, 1911; Palay and Chan-Palay, 1974; Rossi et al., 1991; Sugihara et al., 1999).

Morphology of reconstructed individual olivocerebellar axons

Three olivocerebellar axons in irradiated rats were reconstructed along their entire extent from the ventral medulla near the BDA injection site to all climbing fiber terminal arborizations originating from these axons. In two cases, some non-climbing fiber thin collaterals (see below) were not completely traced. Eleven other axons were partially reconstructed from more than one climbing fiber terminal arborization to the putative stem olivocerebellar axon in the deep cerebellar white matter or in the medulla. The stem olivocerebellar axons ran within the labeled fiber bundle, which continued from the inferior olive, through the inferior cerebellar peduncle and to the deep cerebellar white matter rostral to the cerebellar nucleus (Fig.4, inset). These axons had a diameter of ∼0.7–1 μm and had no collaterals in the medulla except for one or a few thin collaterals in the inferior cerebellar peduncle near the junction to the cerebellum (Fig. 4, inset). In the deep cerebellar white matter, each axon gave off one or a few thin collaterals that terminated within a small area in the cerebellar nucleus (Fig. 4), and sometimes a few thin collaterals that terminated in the cerebellar white matter. Morphological characteristics of these axonal pathways and terminations of thin collaterals in the inferior cerebellar peduncle, the cerebellar nucleus, and the cerebellar white matter were identical to those in normal adult rats (Sugihara et al., 1996, 1999).

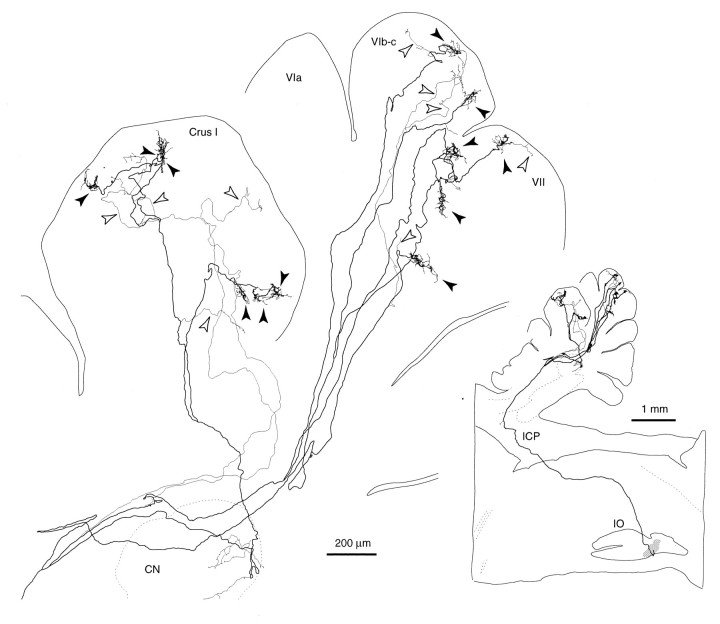

Fig. 4.

Sagittal view of the trajectory of a single olivocerebellar axon innervating vermal lobule VI and VII and hemispheric crus I in an irradiated rat, reconstructed from 72 serial sagittal sections. Inset shows the nearly complete path of this axon from the ventral medulla near the injection site. This axon was labeled presumably by the uptake of BDA at the portion passing through the injection site (the right inferior olive). Because the number of labeled axons was small in the right cerebellar cortex, tracing all thin collaterals was possible. Black arrowheads indicate climbing fiber terminal arborizations, andopen arrowheads indicate non-climbing fiber thin collaterals. Abbreviations in this and subsequent figures:I-X, lobules I-X; a-d, sublobules a-d;C, caudal; CN, cerebellar nucleus;CP, copula pyramidis; Crus I, crus I ansiform lobule; Crus II, crus II ansiform lobule;D, dorsal; DPFL, dorsal paraflocculus;FL, flocculus; GL, granular layer;ICP, inferior cerebellar peduncle; IO, inferior olive; ML, molecular layer;Param, paramedian lobule; PCL, Purkinje cell layer; R, rostral; Sim, simple lobule; V, ventral; VPFL, ventral paraflocculus; WM, white matter.

Each reconstructed axon ramified many times in the deep cerebellar white matter, in the folial white matter, and in the cerebellar cortex. Branches could be classified into two types according to the thickness and morphology of their termination, as in normal adult rats (Sugihara et al., 1999): (1) thick branches terminating as climbing fibers, and (2) non-climbing fiber thin collaterals. Each thick branch (Fig. 4,filled arrowheads) had a diameter of 0.7–1 μm and a terminal arborization with a dense cluster of swellings at its end, equivalent to the climbing fiber terminal arborization in the normal rat. In the present study, the terminal portions of these thick branches were designated “climbing fibers”, as in the normal adult rat. The numbers of climbing fibers per olivocerebellar axon were 11, 12, and 12 in three completely reconstructed axons. These numbers were much larger than the numbers of climbing fibers per olivocerebellar axon in a control Wistar rat in the present experiments (4;n = 1) and in normal adult Long–Evans rats (6.1 ± 3.7; n = 16; Sugihara et al., 1999).

Morphology of single climbing fiber terminal arborizations

In cortical areas in which only a small number of olivocerebellar axons were labeled, many labeled climbing fiber terminal arborizations did not overlap with each other, allowing detailed observation and reconstruction. Individual terminal arborizations of 24 climbing fibers were completely reconstructed from two to four serial sections each, and their morphological details were examined. These were classified as irregular, superficial, or vertical projections, according to their morphology, the thickness of the cortical layers, and the type of the mass olivocerebellar projection in nearby areas. Eleven of these climbing fibers were traced proximally to the olivocerebellar stem axon to identify them as climbing fibers. Climbing fiber terminal arborizations originating from the same axon were sometimes of different types, depending on their termination areas.

Single climbing fiber terminal arborizations in irregular projection areas

Single climbing fiber terminal arborizations in irregular projection areas were located in the molecular (Figs.5A,6D) and Purkinje cell layers (Fig. 6A), and occasionally in the granular layer (Fig. 6F, open arrowheads). Within each terminal arborization, a climbing fiber ramified into a few relatively thick fibers. These gave rise to many thin short fibers (diameter, ∼0.2–0.3 μm) having frequent en passant and terminal swellings (diameter, 0.5–3.5 μm, mostly 1.2–2.0 μm). Because these thick and thin fibers were equivalent to the “stalk” fibers and “tendril” fibers in a normal climbing fiber terminal arborization (Palay and Chan-Palay, 1974; Ito, 1984; Rossi et al., 1991; Sugihara et al., 1999), we use these terms in this paper.

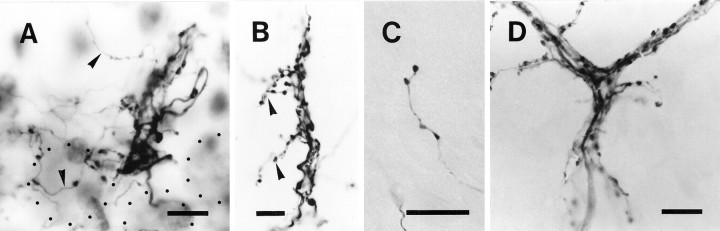

Fig. 5.

Photomicrographs of significantly deformed single climbing fiber terminal arborizations and of a termination of a non-climbing fiber thin collateral in an irradiated rat.A, A terminal arborization in the Purkinje cell layer and molecular layer of an irregular projection area. The section inA only was counterstained in this figure. Some parts of labeled terminal arborizations were not in focus. Dotted lines indicate the contour of the three Purkinje cells closest to this terminal arborization. Arrowheads indicate thin collaterals given off from this terminal arborization.B, A terminal arborization in the molecular layer in a vertical type projection area. Arrowheads indicate horizontal branches in the terminal arborization that were presumably associated with secondary dendrites of the target Purkinje cell.C, En passant and terminal swellings of the non-climbing fiber collateral of an olivocerebellar axon in the molecular layer. D, Proximal portion of a terminal arborization in the control rat. Proximal side of the climbing fiber is to the bottom in each panel. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Fig. 6.

Single climbing fiber terminal arborizations entirely reconstructed in irradiated rats. A, Sagittal view of a terminal arborization mainly in the Purkinje cell layer in an irregular projection area (lobule IXa-b). Reconstructed from four serial sections. B, Frontal view of the same terminal arborization as in A. C, Horizontal view of the same terminal arborization as in A.D, A terminal arborization located mainly in the molecular layer in an area with some superficial mixed with predominantly irregular projections. E, A smallen passant terminal arborization in the middle of a thick branch of an olivocerebellar axon in the granular layer of an irregular projection area. F, A terminal arborization in the granular layer (open arrowheads) and an en passant terminal arborization in the Purkinje cell layer (filled arrowheads) on the same thick branch of an olivocerebellar axon in a presumed superficial plus irregular projection area. Several non-climbing fiber thin collaterals (filled arrows) and an en passantsmall terminal arborization (open arrow) were given off in the superficial molecular layer. G, A terminal arborization in a vertical projection area. Filled circles indicate the proximal side of the axon. See Figure 4, legend, for abbreviations.

In the normal terminal arborization, most tendril fibers closely surrounded Purkinje cell thick dendrites, making an appearance of compact ivy mantle around a cylinder (Fig. 5D). In irradiated rats, especially in irregular projection areas, tendril fibers often spread in any direction, giving an irregular tuft-like appearance to each terminal arborization (Figs. 5A,6A–D,F). Further examination of the trajectory of a single terminal arborization in frontal, horizontal, and sagittal views (Fig. 6A–C) did not disclose any preferred direction in its spatial organization. Accordingly, reconstruction of an entire terminal arborization had to be done from multiple serial sections, and a single photomicrograph could be focused only on a small portion.

A few long thin collaterals were often given off from the terminal arborization as elongations of tendril fibers (Fig. 5A, arrowheads). These thin collaterals were sometimes longer than 100 μm and had similar morphological characteristics to non-climbing fiber thin collaterals (see below).

Some terminal arborizations extended 50–100 μm and had >100 swellings (Fig. 6A–D). Other terminal arborizations extended <40 μm and had <50 swellings (Fig. 6F).En passant climbing fiber terminal arborizations, which were observed in irradiated rats but never seen in control rats, were usually small (Fig. 6F, filled arrowheads). Very small en passant terminal arborizations sprouted occasionally in any layer of the cerebellar cortex (Fig.6E). The number of swellings of a single climbing fiber terminal arborization in an irregular projection area ranged from 30 to 210 (mean ± SD, 115 ± 52, n = 21 climbing fiber terminal arborizations, excluding the very small ones). By comparison, in normal adult animals, each climbing fiber terminal arborization has similar shape and size (Ramón y Cajal, 1911;Palay and Chan-Palay, 1974; Ito, 1984) with relatively constant number of swellings (250–300 in rat) (Rossi et al., 1993; Sugihara et al., 1999). Taken together, these results indicated significant malformation in the local organization of climbing fiber terminal arborizations, including great variability and general reduction in size in the irregular projection area.

Single climbing fiber terminal arborizations in superficial and vertical projection areas

In areas in with predominantly superficial projections, climbing fiber terminal arborizations similar to those in irregular projection areas (Fig. 6D), and small en passantterminal arborizations (Fig. 6F, open arrows) were observed in the shallow molecular layer. Non-climbing fiber thin collaterals (see below) were most abundant in superficial projection areas.

Climbing fiber terminal arborizations in vertical projection areas (Figs. 5B, 6G) were located in the molecular layer and sometimes extended down to the Purkinje cell layer. Most of the stalk and tendril fibers were localized within single cylinder-shaped areas that were approximately perpendicular to the surface of the cerebellar cortex. Some portions of the terminal arborization extended horizontally for a short distance out of the cylinder (Fig. 5B, arrowheads). Morphological characteristics of these terminal arborizations were intermediate between those in irregular projection areas and those in the normal animal. The number of swellings of a single climbing fiber terminal arborization in a vertical projection area was 99–128 (n = 3).

The morphological characteristics of single climbing fiber terminal arborizations in the control Wistar rats in the present study were identical to those in normal adult Long–Evans rats (Sugihara et al., 1999).

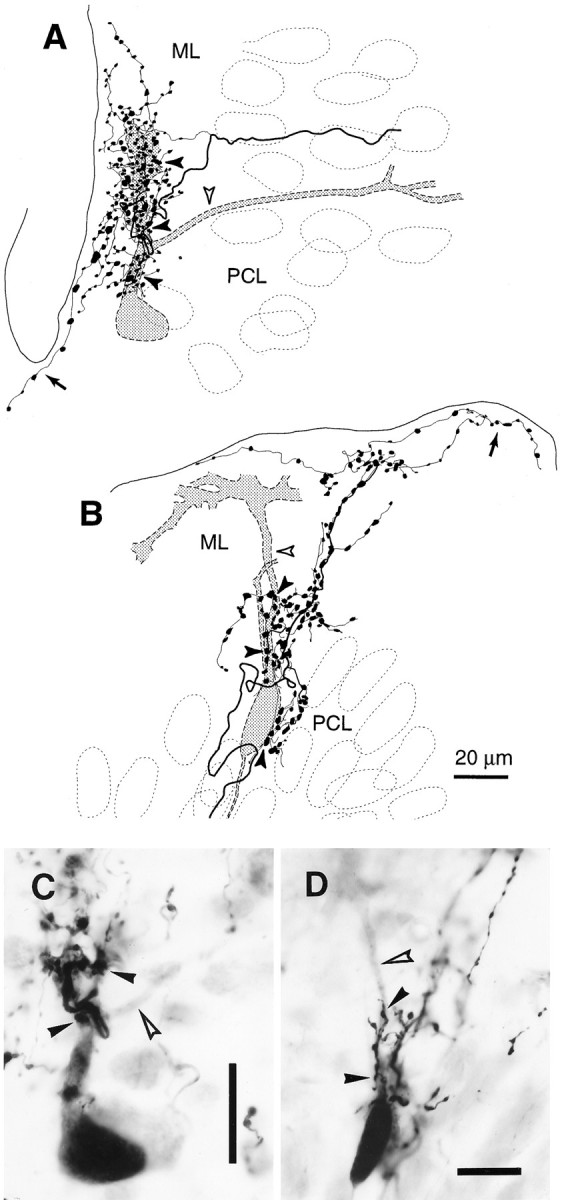

Relationship between a single climbing fiber terminal arborization and its Purkinje cell target

In counterstained irregular projection areas, a climbing fiber terminal arborization seldom made a tight contact with a Purkinje cell soma (Fig. 5A), although small portions of a terminal arborization sometimes touched the somata of one or a few adjacent Purkinje cells. In counterstained vertical projection areas, a climbing fiber terminal arborization appeared to cover the thick vertical portion of dendrites of a single Purkinje cell (Fig. 6G), and the bottom part of the terminal arborization sometimes surrounded a part of the soma of the Purkinje cell (Figs.7B,8A).

Fig. 7.

Climbing fiber terminal arborization covering part of a Purkinje cell dendritic arbor. A, An entire climbing fiber terminal arborization and a Purkinje cell in an irregular projection area (lobule VIb-c) reconstructed from three sections. B, An entire climbing fiber terminal arborization and a Purkinje cell in a vertical projection area (lobule IXc) reconstructed from three sections. C, D, Photomicrographs of the same cases as in panels A andB, respectively. Open arrowheads inA–D indicate the dendrites of the labeled Purkinje cells that were not in contact with the labeled climbing fiber terminal arborizations. Filled arrowheads in A–Dindicate portions of the terminal arborization that were in contact with the thick dendrites and the somata of the Purkinje cells.Arrows in A and B indicate thin collaterals given off from the terminal arborization and running in the superficial molecular layer. Both the Purkinje cells and the climbing fibers in A–D were labeled by BDA injected into the cerebellar nuclei. The sections were counterstained. Scale bars: C, D, 20 μm.

Further observations were made in a preparation in which both climbing fibers and Purkinje cells were labeled by BDA injections into the cerebellar nuclei. We saw 18 cases in which a climbing fiber and an innervated Purkinje cell were both labeled (four cases in vertical projection areas and 14 cases in areas with irregular or with mixed irregular and superficial projections). In a representative case observed in an irregular projection area, a climbing fiber terminal arborization made contact with a Purkinje cell at the primary dendrite and one of the two secondary dendrites (Fig. 7A,C, filled arrowheads) but not at all with the other secondary dendrite (Fig.7A,C, open arrowheads). Close observation revealed that approximately half of the swellings (90 of 202) of this climbing fiber terminal arborization touched the dendrites of this labeled Purkinje cell. The other swellings may touch unlabeled Purkinje cells or other neurons. Thus, unlike normal terminal arborizations, the shape of this terminal arborization did not follow the form of the Purkinje cell dendritic arbor but had a tuft-like appearance. In another case observed in a vertical projection area (Fig. 7B,D), the entire climbing fiber terminal arborization was organized perpendicularly to the cortical layers except for a few long thin collaterals running in the most superficial portion of the molecular layer. Approximately 20 swellings in the proximal portion of this terminal arborization made contact with the labeled Purkinje cell soma and the most proximal portion of main thick dendrites (Fig. 7B,D, filled arrowheads). However, the more distal portions of the dendrites (open arrowheads) were not covered by the labeled climbing fiber terminal arborization. The distal portions of this climbing fiber terminal arborization presumably contact dendrites of another Purkinje cell. Similar findings were seen in the other combinations of labeled climbing fibers and Purkinje cells. These results showed that a climbing fiber terminal arborization covered only a part of the dendritic arbor of a Purkinje cell and that all swellings did not tightly contact the dendritic arbor of a single Purkinje cell. This indicates frequent occurrence of multiple innervation, assuming that all primary and secondary dendrites of a Purkinje cell receive climbing fiber input.

True multiple and pseudomultiple innervation of a Purkinje cell by adjacent climbing fibers

When two adjacent climbing fibers happened to be labeled, fine focusing with the microscope revealed that some of the pairs of terminal arborizations formed by these climbing fibers were tightly combined, and even completely intermingled, as illustrated in a case of a vertical projection area (Fig. 8A,B, arrowheads). The shape of entire combined terminal arborizations indicated that they innervated thick dendrites and the soma of a Purkinje cell (Fig.8A,B). These two climbing fibers were separate as long as they could be traced proximally in the folial white matter (∼600 μm) (Fig. 8C). Although their possible single origin cannot absolutely be ruled out, the two climbing fibers probably stemmed from different olivocerebellar axons, providing putative true multiple innervation to the target Purkinje cell.

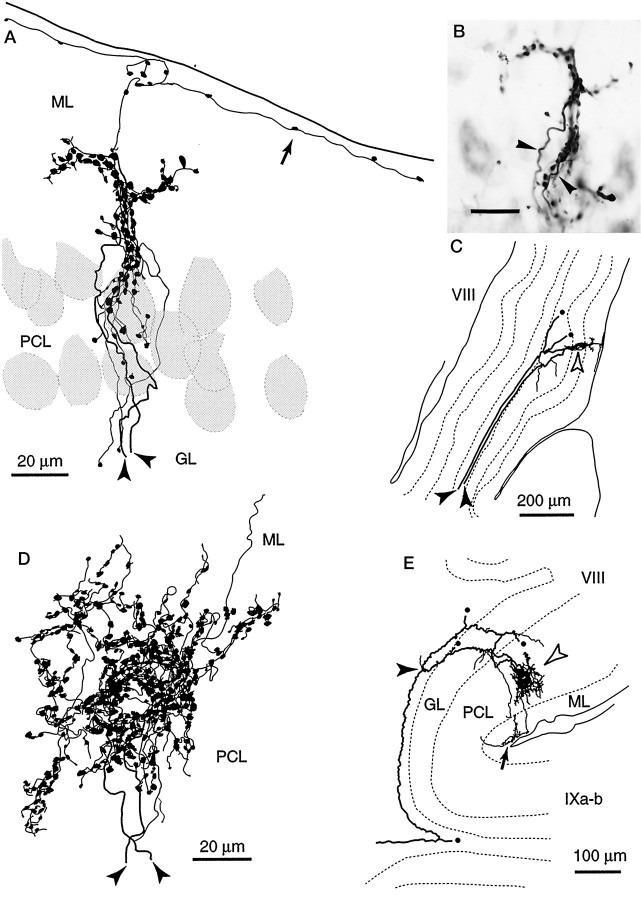

Fig. 8.

Putative true multiple and pseudodouble innervation of a Purkinje cell by two climbing fibers.A, Entire combined climbing fiber terminal arborizations in an irregular projection area reconstructed from two sections.B, Photomicrograph of the same case as inA. Somata of neurons were visualized by counterstaining.Arrowheads in A and Bindicate two climbing fibers forming these terminal arborizations. The continuous arrangement of the combined terminal arborizations indicated that they together innervate a primary dendrite of a single Purkinje cell. C, Two axons (filled arrowheads) forming the combined terminal arborizations shown in A and B (open arrowhead) traced toward the proximal side, reconstructed from six sections. Further tracing was difficult in this case.Circles indicate thick branches given off from one of the axons, which were not reconstructed completely. D, Entire combined terminal arborizations of two climbing fibers (filled arrowheads) in an irregular projection area recon- structed from three sections. They are very closely combined, indicating that they can innervate one or a few Purkinje cells together. E, Trajectory of the climbing fibers inD traced proximally. Reconstructed from 28 sections. Two climbing fibers which form the combined terminal arborizations (open arrowheads) are branches of a single olivocerebellar axon (filled arrowhead). Some thick branches (circles), which ended as climbing fibers, were not drawn completely. The stem axon was traced down to the medulla (data not shown). Arrows inA and E indicate thin collaterals given off from terminal arborizations and running in the superficial molecular layer. Panels A, B, andD were rotated so that the surface of the cerebellum is toward the top. See Figure 4, legend, for abbreviations. Scale bar: B, 20 μm.

Another case of combined terminal arborization occurred in an irregular projection area (Fig. 8D,E). Terminal arborizations of the two climbing fibers merged completely with each other. Although Purkinje cells were not labeled in this preparation, it is very likely that one or more Purkinje cells were innervated by these combined terminal arborizations, i.e., by two climbing fibers. After proximal tracing through serial sections, these two climbing fibers were found to be branches of a single olivocerebellar axon (Fig.8E). Because this type of innervation of a Purkinje cell by multiple climbing fibers originating from single axon should be functionally identical to one-to-one innervation, it is designated as “pseudomultiple” innervation (Sugihara et al., 1999).

Detailed observation of combined terminal arborizations were possible only in areas in which a small number of axons were labeled. In areas in which many axons were labeled, critical observations of individual terminal arborizations were impossible because of the densely labeled plexus, although many cases of true multiple innervation were probably formed there. We observed eleven cases of combined terminal arborizations of two climbing fibers in areas in which small number of climbing fibers were labeled. Four cases were identified as pseudodouble innervation by axonal reconstruction. Ramification sites of climbing fibers forming pseudodouble innervation were in the white matter 200–600 μm away from the terminal arborizations in these cases. One case was identified as true double innervation because only one of the two climbing fibers belonged to a completely reconstructed olivocerebellar axon. Two other cases were identified as putative true double innervation by tracing the axons for >300 μm. The ratio of the number of the pseudodouble innervation versus the number of true double innervation here (1.3) may be an overestimation, because the probability for labeling a true double innervation was low when only a small fraction of olivocerebellar axons were labeled.

Non-climbing fiber thin collaterals of olivocerebellar axons

Reconstructed olivocerebellar axons in normal adult Long–Evans rats gave rise to many non-climbing fiber thin collaterals in the cerebellar white matter and the granular layer, which terminated mainly in the granular layer with sparse en passant and terminal swellings (Sugihara et al., 1999). Reconstructed olivocerebellar axons in the control Wistar rat in the present study also had many thin collaterals of similar characteristics.

Non-climbing fiber thin collaterals in irradiated rats (Figs. 4,open arrowheads, 9,filled arrowheads) seemed similar to the ones in normal rats, but were much more developed. They were given off from the thick branch of olivocerebellar axons in the deep and folial white matter and in the cerebellar cortex before it forms the climbing fiber terminal arborization. The number of the non-climbing fiber thin collaterals given off for three reconstructed olivocerebellar axons was 13, 14, and 19. The non-climbing fiber thin collaterals ramified several times into daughter collaterals in the white matter and in the cerebellar cortex, and usually terminated in the cerebellar cortex near the termination sites of the climbing fibers originating from the same axon (Fig. 4,open arrowheads). Thin collaterals also arose from climbing fiber terminal arborizations (Figs. 7B, 8A,E, arrows), usually terminating within a distance of ∼200 μm after bifurcating several times. The diameters of these thin collaterals were ∼0.2–0.3 μm in distal portions and slightly thicker (0.2–0.7 μm) in proximal portions near the branching site from olivocerebellar stem axons or their thick branches. Thin collaterals terminated in any layer of the cerebellar cortex (Fig.9A). They often terminated in the superficial molecular layer (Figs. 7B, 8A,E, arrows,9A), indicating a significant contribution to the superficial projection (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 9.

Reconstructions of well developed non-climbing fiber thin collaterals of olivocerebellar axons. A, Entire trajectory of two non-climbing fiber collaterals (filled arrowheads), reconstructed from 13 sections. They originated from a thick branch of an olivocerebellar axon that terminated as a climbing fiber (open arrowhead). B, A small en passantterminal arborization formed on a non-climbing fiber thin collateral in the granular layer. The distal side is toward the top. See Figure 4, legend, for abbreviations.

The en passant and terminal swellings were not disposed closely on terminal branches of non-climbing fiber thin collaterals (Figs. 5A,C, 9A) except in a few fibers with a dense disposition of up to 20 swellings (Fig. 9B). These non-climbing fiber thin collaterals could thus be clearly distinguished from climbing fibers, which regularly made terminal arborizations with densely packed swellings. Swellings of non-climbing fiber thin collaterals had sizes similar to or slightly smaller than those in climbing fiber terminal arborizations. The number of swellings per non-climbing fiber thin collateral varied widely (2–110), depending on the length and the number of its ramifications. The number of swellings of all non-climbing fiber thin collaterals in the cerebellar cortex was 190 in a completely reconstructed olivocerebellar axon terminating in irregular projection areas. Because this axon had 12 climbing fibers, and the number of swellings in all climbing fiber terminal arborizations could be estimated to be ∼1380, assuming 115 swellings per a terminal arborization (see above), swellings of non-climbing fiber collaterals accounted for as much as 14% of all swellings in the cerebellar cortex. Therefore, thin collaterals contributed rather significantly to the dense plexus in the irregular projection (Fig.3A).

Most swellings of non-climbing fiber thin collaterals appeared to contact dendritic portions of neurons, although some occasionally touched the somata of neurons in the molecular and granular layers and of Purkinje cells in counterstained preparations. Contacts of some swellings of thin collaterals with Purkinje cell dendrites were seen in the superficial molecular layer in preparations of retrograde labeling of Purkinje cells.

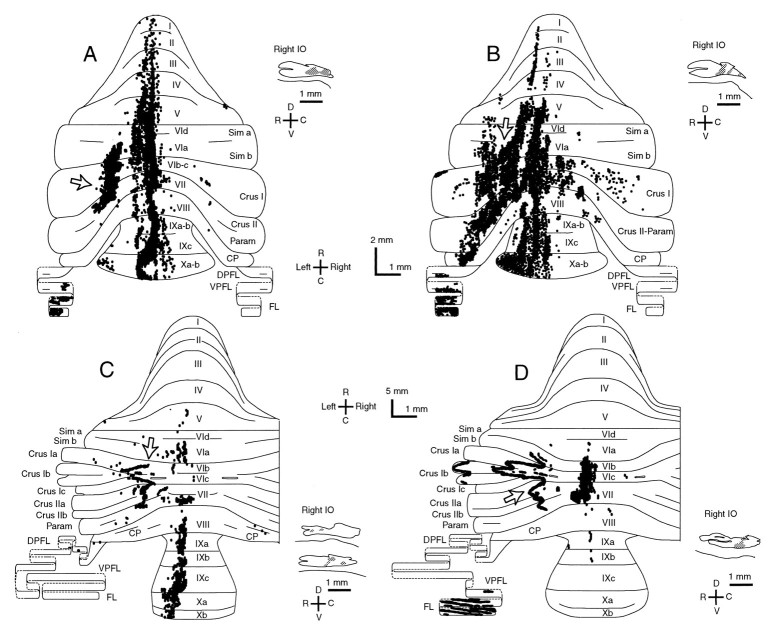

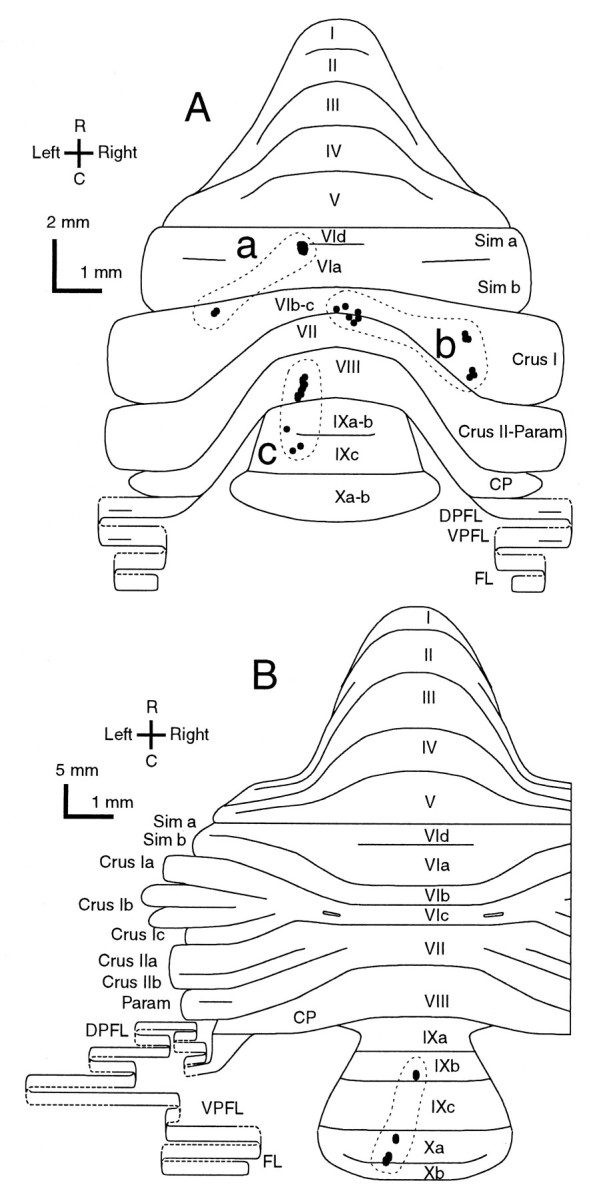

Spatial organization of the projection of olivocerebellar axons

To determine whether the longitudinal zonal pattern of the olivocerebellar projection (Groenewegen and Voogd, 1977;Buisseret-Delmas and Angaut, 1993) was affected, all labeled climbing fiber terminal arborizations were mapped onto the unfolded cerebellar cortex for two irradiated and two control rats (Fig.10). The differences in the distribution of labeled climbing fiber terminal arborizations among these rats could not be compared quantitatively, because the sites and volumes of BDA injections were not identical among animals, but interesting qualitative differences were observed. A tendency for longitudinal zonal distribution was seen in all four rats. In control rats (Fig. 10C,D) clear and narrow longitudinal strips were seen in the hemisphere, intermediate zone, and flocculus, and slightly broader longitudinal zones were seen in the vermis. Note that significant deformation of band-shaped areas in the hemisphere is attributable to the tilt of the longitudinal plane and the foliation of the cerebellar cortex. In irradiated rats (Fig.10A,B), longitudinal zonal distributions were seen in the vermis, intermediate area, and paraflocculus. Distributions of labeled axons in crus I and II (or lobules VIb, VIc, and VII) in the intermediate area were seen in all four cases, presumably originating from the medial accessory olive. These distributions were much wider in irradiated rats (Fig. 10A,B, open arrows) than in controls (Fig. 10C,D, open arrows). Similar differences in the width of distributions occurred in the flocculus (Fig.10B,D).

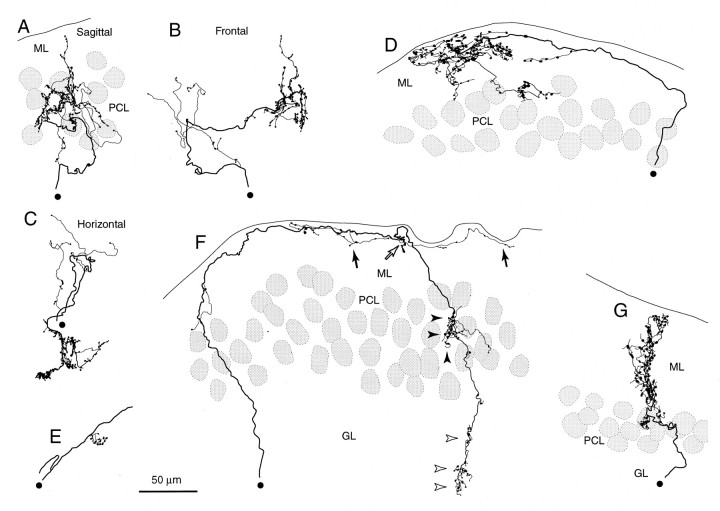

Fig. 10.

Zonal distribution of labeled climbing fiber terminal arborizations in the cerebellar cortex of irradiated and control rats. A, B, Irradiated rats. Two (A) and three (B) injections of BDA were made into the right inferior olive. Eachdot represents a climbing fiber terminal arborization.C, D, Control rats. Insets inA–D, parasagittal sections of the right inferior olive showing BDA injection sites. Distance from the midline for injection sites, 0.25 mm (A), 0.25 mm (B), 0.07 mm (C, top), 0.24 mm (C, bottom), and 0.2 mm (D). Arrows in A–D indicate the distributions of terminal arborizations in the intermediate area of the cerebellum (see Results). In each diagram of the cerebellum, the mediolateral distances for each terminal arborization and the cerebellar outline were to scale (measured by the number of the parasagittal sections). The rostrocaudal dimension of each cerebellar lobule was determined by measuring the length of the Purkinje cell layer in each lobule in parasagittal sections at the midline and at 1.5 and 3 mm lateral to the midline. Therefore, the diagrams represent the entire Purkinje cell layer approximately. The primary fissure was made straight arbitrarily. The rostrocaudal distances in the paraflocculus and flocculus were not to scale (enlarged). Broken outlines in the paraflocculus and flocculus indicate the continuation of the Purkinje cell layer. The position in the rostrocaudal axis for each terminal arborization was determined by measuring its relative distance from the borders of the lobule in parasagittal sections. See Figure 4, legend, for abbreviations.

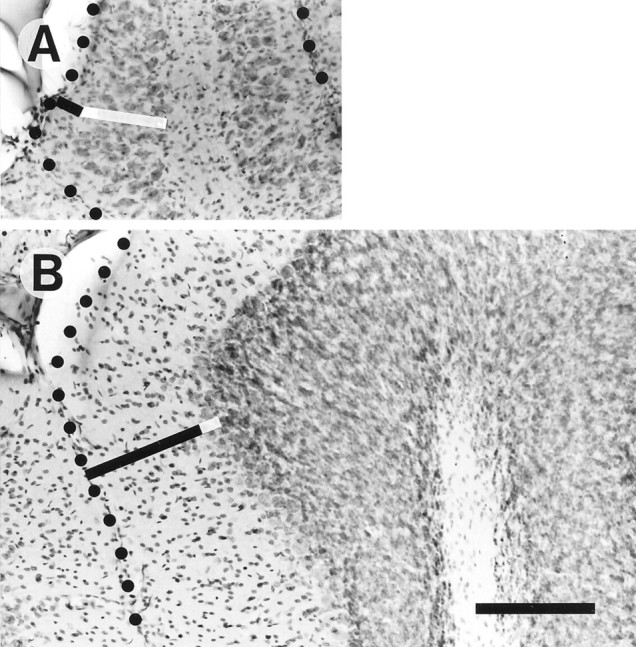

Many more labeled climbing fibers were seen in the side ipsilateral (right) to the injection in irradiated rats than in control rats (Fig.10A–D). Some of them originated from axons coming through the ipsilateral inferior cerebellar peduncle, which were presumably labeled by the uptake of BDA at the axon passing through the injection site. The others originated from thick branches of olivocerebellar axons that crossed the midline in the cerebellum (double crossing). In fact, the numbers of axons crossing the midline in the cerebellum (Fig. 11) was much larger in irradiated rats (n = 75 and 97; in the rats in Fig. 10A,B, respectively) than in control rats (n = 8 and 15; in the rats in Fig. 10C,D, respectively). These numbers did not exactly correspond to the number of labeled climbing fiber terminal arborizations in the ipsilateral side, one reason being that axons were not necessarily well labeled up to the end. In any case, the number of axons crossing the midline within the cerebellum to form the ipsilateral projections, which is very few (<3%) in normal adult rats (Sugihara et al., 1999), was significantly increased in irradiated rats.

Fig. 11.

Increased midline crossing by olivocerebellar axons in the cerebellum. A, Axons in a sagittal section of an irradiated rat (the case in Fig. 10B).B, Axons in a sagittal section of an control rat (the case in Fig. 10D). Only axons running transversely in the white matter in the sagittal section were drawn.

The lobular distributions of climbing fibers originating from three reconstructed olivocerebellar axons were then examined (Fig.12A). In the axon in Figure 12Ac, nine climbing fibers in lobule VIII, one in lobule IXa-b, and two in lobule IXc were located within a single longitudinal strip. In another axon in Figure 12Aa, nine climbing fiber terminal arborizations were located in a small area in lobule VIa in the lateral vermis. Two other climbing fiber terminal arborizations located in crus I were separated from the other climbing fibers by 1.8 mm mediolaterally. In the other axon (Fig.12Ab), six terminal arborizations were located in the lobules VIc and VII in the vermis within a width of 0.5 mm, and six climbing fibers of the same axon in crus I within a width of ∼0.3 mm. The two groups of climbing fibers were separate by ∼2.6 mm mediolaterally. In an axon in a control rat (Fig.12B), four climbing fiber terminal arborizations were located in lobules IXb and Xa, presumably within a narrow longitudinal strip as generally found in normal adult rats (Sugihara et al., 1997,1999).

Fig. 12.

Distribution in the cerebellar cortex of all climbing fiber terminal arborizations originating from single olivocerebellar axons, indicating some lateral branching.A, Three axons terminating in crus I and vermal lobule VIa (a), in vermal lobules VIb-c and VII and in crus I (b), and in vermal lobule VIII and IX (c) in an irradiated rat. Nine climbing fiber terminal arborizations are located within a small area in lobule VIa, some of which made pseudomultiple innervations, in the case ofa. The case in b is the same axon as shown in Figure 4. B, An axon terminating in lobule IXb and X in a control rat. Dots surrounded by each broken contour represent individual climbing fiber terminal arborizations originating from a single axon. Single olivocerebellar axons for each (a–d) were completely reconstructed except for some thin collaterals. The diagrams of the unfolded cerebellar cortex are similar to those in Figure 10. See Figure 4, legend, for abbreviations.

These results indicated that longitudinal zone-shaped organization was generally maintained as a basic rule of the olivocerebellar projection in irradiated rats. However, significant aberrations were present, including presumed mediolateral enlargement or blurred borders of zones, wide mediolateral branching of some olivocerebellar axons into multiple zones, and an increase of double-crossing axons.

DISCUSSION

Detailed data on the fate of olivocerebellar axons in the mutant or the experimental granuloprival cerebella have been largely missing. The present study reveals significant morphological abnormalities of single olivocerebellar axons in the X-irradiated cerebellum, including deformations of climbing fiber terminal arborization, true multiple and pseudomultiple innervations, well developed thin collaterals, and aberrant lateral branches. The results described here provide a useful baseline description of the abnormal anatomy of the olivocerebellar projection induced by early granule cell deficiency and will aid interpretation of the perturbations of cerebellar development in other mutants deficient for critical molecules.

Because the morphology of olivocerebellar axons in X-irradiated rats is nearly normal in the cerebellar white matter, cerebellar nuclei, and medulla, and because climbing fibers originating from the same axon have different types of terminal arborizations depending on projection areas (irregular or vertical), it is clear that their abnormalities are produced by aberrant local interactions in the cerebellar cortex rather than by changes in olivary neurons. Despite abnormal cerebellar development, the Purkinje cell projection to the deep cerebellar nuclei persists in the X-irradiated rat. Thin collaterals of olivocerebellar axons could have abnormal interactions in the cerebellar nuclei, although no obvious abnormalities were seen in the present study. These results support the idea that the regression of Purkinje cell innervation by multiple climbing fibers to innervation by a single climbing fiber is attributable to local interactions in the cerebellar cortex.

Climbing fiber association with Purkinje cells

A climbing fiber forms a dense plexus called a nest (nid) around a Purkinje cell soma in the neonatal period at ∼6–9 d. The plexus moves to the dendrites during the development of the Purkinje cell dendritic arbor (Ramón y Cajal, 1911; O'Leary et al., 1970;Palay and Chan-Palay, 1974; Mason et al., 1990; Chédotal and Sotelo, 1993). Terminal arborizations of climbing fibers make contact mainly with Purkinje cell dendrites in the irradiated adult cerebellum (Figs. 7, 8), as shown by previous electron microscopical studies (Altman and Anderson, 1972; Bailly et al., 1990). In irradiated rats, the climbing fiber terminal arborizations are significantly disorganized in shape and are not tightly associated with the dendritic arbor of a single Purkinje cell (Figs. 5A, 6), especially in the irregular projection area. These observations indicate that preference for Purkinje cells as climbing fibers targets is largely retained in the granuloprival cerebellum, and the shift of the climbing fiber terminal arborization from around the Purkinje cell soma to the Purkinje cell thick dendrites seems independent of the development of granule cell-parallel fiber system, as previously discussed (Mariani, 1983). However, our data indicate that the complete development of normal climbing fiber terminal arborizations with organized tendril fibers and swellings is dependent on the granule cell-parallel fiber system. The selective synaptic relationships between a single, mature climbing fiber terminal arborization and a Purkinje cell by regression of supernumerary climbing fibers would contribute to this development.

Multiple innervation of Purkinje cells by climbing fibers

Electrophysiological studies show a high degree of multiple innervation in X-irradiated rats (Crepel et al., 1976b; Crepel and Delhaye-Bouchaud, 1979; Mariani et al., 1990). Specifically, almost all Purkinje cells retain multiple innervation, with a mean innervation rate of three or four climbing fibers per Purkinje cell, in rats irradiated with the same protocol used here (Fuhrman et al., 1994). Occupation of different domains of the dendritic arbor of a PC (Figs.7, 8A) by different climbing fiber terminal arborizations provides morphological evidence for multiple innervation, although heterologous innervation by mossy fibers and lack of climbing fibers on some dendrites cannot be ruled out. The presence of tightly combined terminal arborizations (Fig. 8) indicates significant overlap of these domains of the Purkinje cell dendritic arbor innervated by different climbing fibers, in contrast to the sharply partitioned dendritic domains described for the multiple innervation in the methylazoxymethanol acetate-treated hypogranular cerebellum (Bravin et al., 1995; Zagrebelsky and Rossi, 1999).

Because a single olivocerebellar axon gives rise to several climbing fibers, it is reasonable to assume that pairs of climbing fibers originating from the same or from different olivocerebellar axons can multiply innervate a Purkinje cell (true multiple and pseudomultiple innervation) in the irradiated rat. On the other hand, virtually no true multiple and very rare pseudomultiple innervations are seen in the normal adult rat, and, in these few cases, climbing fibers bifurcate at a site very close to the terminal arborization from a common stem axon (Sugihara et al., 1999). These results indicate that the normal elimination of supernumerary climbing fibers concerns not only true multiple but also pseudomultiple innervation, unless the bifurcation is very close to the terminal arborization. One possible mechanism for elimination of both pseudo- and true multiple innervation may be a specific signal that identifies each climbing fiber terminal arborization, but not the whole olivocerebellar axon. This signal might affect the molecular cascades involving critical subtypes of glutamate receptors (Rabacchi et al., 1992) and transporters (Watase et al., 1998) and cytoplasmic second messengers in the Purkinje cells (Kashiwabuchi et al., 1995; Kano et al., 1995, 1997, 1998; Offermanns et al., 1997), which are presumed to contribute to the climbing fiber synapse elimination process but remain largely unknown. Neither coincidence of electrical activities nor a specific substance expressed in each olivocerebellar axon can be the principal cue to select a single climbing fiber, because otherwise the loss of most of pseudomultiple innervation in normal rats could not be explained.

Non-climbing fiber thin collaterals

In normal rats, thin collaterals of olivocerebellar axons have a small number of swellings, and terminate mainly in the granular layer and occasionally in the Purkinje cell layer but never in the molecular layer (Sugihara et al., 1999). By comparison, thin collaterals in irradiated rats innervate all layers of the cerebellar cortex, especially the superficial molecular layer, with abundant swellings (Fig. 9A) that contact Purkinje cells and other neurons. Thin collaterals occasionally even have small terminal arborization-like clusters of swellings (Fig. 9B). The thin collaterals arising from a climbing fiber terminal arborization are very short in normal rats (retrograde collaterals and transverse branchlets; Scheibel and Scheibel, 1954; Sugihara et al., 1999), but they are relatively long and have many swellings in irradiated rats. These data strongly suggest that the normal granule cell-parallel fiber system induces atrophy of non-climbing fiber thin collaterals and their retraction from the molecular layer, contributing to the distinction between climbing fibers and non-climbing fiber thin collaterals.

The zonal projection pattern of olivocerebellar axons

The olivocerebellar projection pattern in longitudinal zones appears to be retained in the irradiated rat (Fig. 10). This pattern is thought to be established in the newborn rat (Sotelo et al., 1984;Wassef et al., 1992a,b), the hypogranular rat (Zagrebelsky and Rossi, 1999), mutant mice (Blatt and Eisenman, 1993), and the chicken embryo (Chédotal et al., 1996). With anterograde tracers such as3H-leucine (Sotelo et al., 1984; Blatt and Eisenman, 1993) and BDA (Zagrebelsky and Rossi, 1999), or molecular markers for olivocerebellar axons such as parvalbumin (Wassef et al., 1992b), calbindin (Wassef et al., 1992a), calcitonin gene-related peptide (Wassef et al., 1992a; Zagrebelsky and Rossi, 1999), and the cell adhesion molecule BEN (Chédotal et al., 1996), studies have demonstrated the segregation of labeled olivocerebellar axons in longitudinal stripes in the cerebellar cortex. In contrast, climbing fiber terminal arborizations originating from a single olivocerebellar axon distribute generally within a single thin longitudinal strip in normal adult rats (Sugihara et al., 1997, 1999). Wide transverse distributions have not been detected so far except for a few cases of bilateral but nearly symmetrical projections (Sugihara et al., 1999). Some mediolateral branching is known to occur in the intermediate area of the anterior lobe in the cat (Ekerot and Larson, 1982), but such wide mediolateral branching extending from the vermis to the hemisphere, as in the irradiated rat (Fig. 12Aa,b), is not known in any species. Blurring of the zonal pattern and an increase in the bilateral projection (Figs. 10, 11) are consistent with electrophysiological data that detected disorganization in the receptive field representation (Fuhrman et al., 1994) and ipsilateral climbing fiber responses to vibrissal stimulation (Fuhrman et al., 1995) in the vermis of the irradiated rat. The approximately doubled number (∼12) of climbing fibers given off per single olivocerebellar axon, compared to the normal adult rat (6.1; Sugihara et al., 1999) supports the maintenance of these aberrant olivocerebellar projections. These aberrations indicate that the zonal projection pattern of olivocerebellar axons is less refined in irradiated rats than in normal rats.

The topographical olivocerebellar projection in the newborn, which may be dependent on specific afferent-target matching via molecules such as BEN (Chédotal et al., 1996), might be relatively crude and subjected to further refinement during normal development. It can be postulated that this refinement is impaired by irradiation and that the immature olivocerebellar projection pattern persists abnormally during adulthood in the irradiated cerebellum. Our study suggests that granule cells play a critical role in refining the spatial pattern of the olivocerebellar projection by synapse elimination and subsequent deletion of aberrant mediolateral axonal branches.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry for Education, Science, and Culture of Japan (I.S.) and grants from Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique to J. M. and Y. B. We thank Dr. Ann Lohof for reading this manuscript.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Izumi Sugihara, Department of Physiology, Tokyo Medical and Dental University School of Medicine, 1-5-45 Yushima, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113–8519, Japan. E-mail:isugihara.phy1@med.tmd.ac.jp.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altman J, Anderson WJ. Experimental reorganization of the cerebellar cortex. I. Morphological effects of elimination of all microneurons with prolonged X-irradiation started at birth. J Comp Neurol. 1972;146:355–406. doi: 10.1002/cne.901460305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altman J, Bayer SA. Development of the cerebellar system in relation to its evolution, structure, and functions. CRC; Boca Raton, FL: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailly Y, Schoen SW, Delhaye-Bouchaud N, Kreutzberg GW, Mariani J. Synaptic localization of 5′-nucleotidase activity in the cerebellar cortex of the adult rat after postnatal X-irradiation. C R Acad Sci III. 1990;311:487–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailly Y, Schoen SW, Delhaye-Bouchaud N, Kreutzberg GW, Mariani J. 5′-nucleotidase activity as a synaptic marker of parasagittal compartmentation in the mouse cerebellum. J Neurocytol. 1995;24:879–890. doi: 10.1007/BF01179986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailly Y, Kyriakopoulou K, Delhaye-Bouchaud N, Mariani J, Karagogeos D. Cerebellar granule cell differentiation in mutant and X-irradiated rodents revealed by the neural adhesion molecule TAG-1. J Comp Neurol. 1996;369:150–161. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960520)369:1<150::AID-CNE11>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailly Y, Schoen SW, Mariani J, Kreutzberg GW, Delhaye-Bouchaud N. Immature chemodifferentiation of Purkinje cell synapses revealed by 5′-nucleotidase ecto-enzyme activity in the cerebellum of the reeler mouse. Synapse. 1998;29:279–292. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199807)29:3<279::AID-SYN11>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benoit P, Delhaye-Bouchaud N, Changeux J-P, Mariani J. Stability of multiple innervation of Purkinje cells by climbing fibers in the agranular cerebellum of old rats X-irradiated at birth. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1984;14:310–313. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(84)90320-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benoit P, Mariani J, Delhaye-Bouchaud N, Chappuis G. Evidence for a multiple innervation of cerebellar Purkinje cells by climbing fibers in adult ferrets infected at birth by a mink enteritis virus. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1987;34:51–57. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(87)90194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blatt GJ, Eisenman LM. The olivocerebellar projection in normal (+/+), heterozygous weaver (wv/+), and homozygous weaver (wv/wv) mutant mice: comparison of terminal pattern and topographic organization. Exp Brain Res. 1993;95:187–201. doi: 10.1007/BF00229778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bravin M, Rossi F, Strata P. Different climbing fibres innervate separate dendritic regions of the same Purkinje cell in hypogranular cerebellum. J Comp Neurol. 1995;357:395–407. doi: 10.1002/cne.903570306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buisseret-Delmas C, Angaut P. The cerebellar olivo-corticonuclear connections in the rat. Prog Neurobiol. 1993;40:63–87. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(93)90048-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chédotal A, Sotelo C. The “creeper stage” in cerebellar climbing fiber synaptogenesis precedes the “pericellular nest”—ultrastructural evidence with parvalbumin immunocytochemistry. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1993;76:207–220. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(93)90209-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chédotal A, Pourquié O, Ezan F, Clemente HS, Sotelo C. BEN as a presumptive target recognition molecule during the development of the olivocerebellar system. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3296–3310. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-10-03296.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crepel F, Delhaye-Bouchaud N. Distribution of climbing fibres on cerebellar Purkinje cells in X-irradiated rats. An electrophysiological study. J Physiol (Lond) 1979;290:97–112. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crepel F, Mariani J. Multiple innervation of Purkinje cells by climbing fibers in the cerebellum of the Weaver mutant mouse. J Neurobiol. 1976;7:579–582. doi: 10.1002/neu.480070610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crepel F, Mariani J, Delhaye-Bouchaud N. Evidence for a multiple innervation of Purkinje cells by climbing fibers in the immature rat cerebellum. J Neurobiol. 1976a;7:567–578. doi: 10.1002/neu.480070609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crepel F, Delhaye-Bouchaud N, Legrand J. Electrophysiological analysis of the circuitry and of the corticonuclear relationships in the agranular cerebellum of irradiated rats. Arch Ital Biol. 1976b;114:49–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crepel F, Delhaye-Bouchaud N, Dupont JL. Fate of the multiple innervation of cerebellar Purkinje cells by climbing fibers in immature control, X-irradiated and hypothyroid rats. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1981;1:59–71. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(81)90094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eccles JC, Llinás R, Sasaki K. The excitatory synaptic action of climbing fibres on the Purkinje cells of the cerebellum. J Physiol (Lond) 1966;182:268–296. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp007824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisenman LM, Hawkes R. Antigenic compartmentation in the mouse cerebellar cortex: zebrin and HNK-1 reveal a complex, overlapping molecular topography. J Comp Neurol. 1993;335:586–605. doi: 10.1002/cne.903350410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ekerot C-F, Larson B. Branching of olivary axons to innervate pairs of sagittal zones in the cerebellar anterior lobe of the cat. Exp Brain Res. 1982;48:185–198. doi: 10.1007/BF00237214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuhrman Y, Thomson MA, Piat G, Mariani J, Delhaye-Bouchaud N. Enlargement of olivo-cerebellar microzones in the agranular cerebellum of adult rats. Brain Res. 1994;638:277–284. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90660-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fuhrman Y, Piat G, Thomson MA, Mariani J, Delhaye-Bouchaud N. Abnormal ipsilateral functional vibrissae projection onto Purkinje cells multiply innervated by climbing fibers in the rat. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1995;87:172–178. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(95)00072-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Groenewegen HJ, Voogd J. The parasagittal zonation within the olivocerebellar projection. I. Climbing fiber distribution in the vermis of cat cerebellum. J Comp Neurol. 1977;174:417–488. doi: 10.1002/cne.901740304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herrup K, Kuemerle B. The compartmentalization of the cerebellum. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1997;20:61–90. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito M. The cerebellum and neural control. Raven; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kano M, Hashimoto K, Chen C, Abeliovich A, Aiba A, Kurihara H, Watanabe M, Inoue Y, Tonegawa S. Impaired synapse elimination during cerebellar development in PKCγ mutant mice. Cell. 1995;83:1223–1231. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kano M, Hashimoto K, Kurihara H, Watanabe M, Inoue Y, Aiba A, Tonegawa S. Persistent multiple climbing fiber innervation of cerebellar Purkinje cells in mice lacking mGluR1. Neuron. 1997;18:71–79. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kano M, Hashimoto K, Watanabe M, Kurihara H, Offermanns S, Jiang H, Wu Y, Jun K, Shin H-S, Inoue Y, Simon MI, Wu D. Phospholipase Cβ4 is specifically involved in climbing fiber synapse elimination in the developing cerebellum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15724–15729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kashiwabuchi N, Ikeda K, Araki K, Hirano T, Shibuki K, Takayama C, Inoue Y, Kutsuwada T, Yagi T, Kang Y, Aizawa S, Mishina M. Impairment of motor coordination, Purkinje cell synapse formation, and cerebellar long-term depression in GluRδ2 mutant mice. Cell. 1995;81:245–252. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90334-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larsell O. The morphogenesis and adult pattern of the lobules and fissures of the cerebellum of the white rat. J Comp Neurol. 1952;97:281–356. doi: 10.1002/cne.900970204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Latham A, Paul DH, Smart JL, Stephens DN. Comparison of cerebellar Purkinje cell simple spike discharges in adult rats after undernutrition during the suckling period and nutritionally normal rats. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1982;4:223–227. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(82)90044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Llinás R, Hillman DE, Precht W. Neuronal circuit reorganization in mammalian agranular cerebellar cortex. J Neurobiol. 1973;4:69–94. doi: 10.1002/neu.480040106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mariani J. Extent of multiple innervation of Purkinje cells by climbing fibers in the olivocerebellar system of weaver, reeler and staggerer mutant mice. J Neurobiol. 1982;13:119–126. doi: 10.1002/neu.480130204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mariani J. Elimination of synapses during the development of the central nervous system. In: Changeux J-P, Glowinski J, Imbert M, Bloom FE, editors. Molecular and cellular interactions underlying higher brain functions. Progress in brain research, Vol 58. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1983. pp. 383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mariani J, Changeux J-P. Ontogenesis of olivocerebellar relationships. I. Studies by intracellular recordings of the multiple innervation of Purkinje cells by climbing fibers in the developing rat cerebellum. J Neurosci. 1981a;1:696–702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-07-00696.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mariani J, Changeux J-P. Ontogenesis of olivocerebellar relationships. II. Spontaneous activity of inferior olivary neurons and climbing fiber-mediated activity of cerebellar Purkinje cells in developing rats. J Neurosci. 1981b;1:703–709. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-07-00703.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mariani J, Mulle C, Geoffroy B, Delhaye-Bouchaud N. Peripheral maps and synapse elimination in the cerebellum of the rat. II. Representation of peripheral inputs through the climbing fiber pathway in the posterior vermis of X-irradiated adult rats. Brain Res. 1987;421:211–225. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mariani J, Benoit P, Hoang MD, Thomson M-A, Delhaye-Bouchaud N. Extent of multiple innervation of cerebellar Purkinje cells by climbing fibers in adult X-irradiated rats. Comparison of different schedules of irradiation during the first postnatal week. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1990;57:63–70. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(90)90185-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mason CA, Christakos S, Catalano SM. Early climbing fiber interactions with Purkinje cells in the postnatal mouse cerebellum. J Comp Neurol. 1990;297:77–90. doi: 10.1002/cne.902970106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matus A, Delhaye-Bouchaud N, Mariani J. Microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) in Purkinje cell dendrites: evidence that factors other than binding to microtubules are involved in determining its cytoplasmic distribution. J Comp Neurol. 1990;297:435–440. doi: 10.1002/cne.902970308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Offermanns S, Hashimoto K, Watanabe M, Sun W, Kurihara H, Thompson RF, Inoue Y, Kano M, Simon MI. Impaired motor coordination and persistent multiple climbing fiber innervation of cerebellar Purkinje cells in mice lacking Galphaq. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14089–14094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.14089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'Leary JL, Inukai J, Smith JM. Histogenesis of the cerebellar climbing fiber in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1970;142:377–392. doi: 10.1002/cne.901420307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palay SL, Chan-Palay V. Cerebellar cortex. Cytology and organization. Springer; New York: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Puro DG, Woodward DJ. Maturation of evoked climbing fiber input to rat cerebellar Purkinje cells (I.). Exp Brain Res. 1977a;28:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00237088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Puro DG, Woodward DJ. The climbing fiber system in the Weaver mutant. Brain Res. 1977b;129:141–146. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90976-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Puro DG, Woodward DJ. Physiological properties of afferents and synaptic reorganization in the rat cerebellum degranulated by postnatal X-irradiation. J Neurobiol. 1977c;9:195–215. doi: 10.1002/neu.480090303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rabacchi S, Bailly Y, Delhaye-Bouchaud N, Mariani J. Involvement of the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor in synapse elimination during cerebellar development. Science. 1992;256:1823–1825. doi: 10.1126/science.1352066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramón y Cajal S. Histologie du système nerveux de l'homme et des vertébrés, Vol. Maloine; II. Paris: 1911. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rossi F, Wiklund L, Van der Want JJL, Strata P. Reinnervation of cerebellar Purkinje cells by climbing fibers surviving a subtotal lesion of the inferior olive in the adult rat. I. Development of new collateral branches and terminal plexuses. J Comp Neurol. 1991;308:513–535. doi: 10.1002/cne.903080403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rossi F, Borsello T, Vaudano E, Strata P. Regressive modifications of climbing fibres following Purkinje cell degeneration in the cerebellar cortex of the adult rat. Neuroscience. 1993;53:759–778. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90622-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scheibel ME, Scheibel AB. Observations on the intracortical relations of the climbing fibers of the cerebellum. A Golgi study. J Comp Neurol. 1954;101:733–763. doi: 10.1002/cne.901010305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shinoda Y, Yokota J, Futami T. Divergent projection of individual corticospinal axons to motoneurons of multiple muscles in the monkey. Neurosci Lett. 1981;23:7–12. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(81)90182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sotelo C. Formation of presynaptic dendrites in the rat cerebellum following neonatal X-irradiation. Neuroscience. 1977;2:275–283. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(77)90094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sotelo C, Bourrat F, Triller A. Postnatal development of the inferior olivary complex in the rat. II. Topographic organization of the immature olivocerebellar projection. J Comp Neurol. 1984;222:177–199. doi: 10.1002/cne.902220204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sugihara I, Lang EJ, Llinás R. Serotonin modulation of inferior olivary oscillations and synchronicity: a multiple-electrode study in the rat cerebellum. Eur J Neurosci. 1995;7:521–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sugihara I, Wu H, Shinoda Y. Morphology of axon collaterals of single climbing fibers in the deep cerebellar nuclei of the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1996;217:33–36. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)13063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sugihara I, Wu H, Shinoda Y. Projection of climbing fibers originating from single olivocerebellar neurons in the rat cerebellar cortex. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1997;23:1830. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sugihara I, Wu H-S, Shinoda Y. Morphology of single olivocerebellar axons labeled with biotinylated dextran amine in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1999;414:131–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Voogd J. Cerebellum. In: Paxinos G, editor. The rat nervous system, Ed 2. Academic; San Diego: 1995. pp. 309–350. [Google Scholar]