Abstract

Objectives

Challenges remain in ensuring universal access to affordable essential medicines. We previously estimated the expected generic prices based on cost of production for medicines in solid oral formulations (ie, capsules or tablets) on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (EML). The objectives of this analysis were to estimate cost-based prices for injectable medicines on the EML and to compare these to lowest current prices in England, South Africa, and India.

Design

Data on the cost of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) exported from India were extracted from an online database of customs declarations (www.infodriveindia.com). A formula was designed to use API price data to estimate a cost-based price, by adding the costs of converting API to a finished pharmaceutical product, including the cost of formulation in vials or ampoules, transportation and an average profit margin.

Results

For injectable formulations on the WHO EML, medicines had prices above the estimated cost-based price in 77% of comparisons in England (median ratio 2.54), and 62% in South Africa (median ratio 1.48), while 85% of medicines in India had prices below estimated cost-based price (median ratio 0.30). 19% of injectable medicines in England, 9% in South Africa, and 5% in India had prices more than 10 times the estimated cost-based price. Medicines that appeared in the top 20 by ratio of lowest current price to estimated cost-based price for more than one country included numerous oncology medicines—irinotecan, leuprorelin, ifosfamide, daunorubicin, filgrastim and mesna—as well as valproic acid and ciclosporin.

Conclusions

Estimating manufacturing costs can identify cases in which profit margins for medicines may be set significantly higher than average.

Keywords: essential medicines, generics, cost of production, health economics, health systems

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The cost assumptions used to estimate cost-based prices were conservative.

The key input of active pharmaceutical ingredient price was based on average values of actual, completed sales of active pharmaceutical ingredient.

Apart from the individual active pharmaceutical ingredient price data, the costing formula was adjusted only for formulation as vial or ampoule, but not for other characteristics such as volume.

We did not estimate demand volumes and did not adjust price estimates based on demand volume.

Introduction

There are persistent challenges in ensuring access to affordable essential medicines in low/middle-income countries (LMICs).1 The WHO’s Model List of Essential Medicines (EML) comprises medicines that meet the priority health needs of global populations and should be available at all times, at affordable prices.2 A previous analysis estimated the cost of production for solid oral formulations (SOFs) in the EML, finding sizeable differences between cost of manufacture and current prices in England, South Africa and India.3

A number of differences between SOFs and injectable formulations could be expected to affect manufacturing costs, such as significantly higher requirements for manufacturing sites to maintain product sterility for intravenous and intramuscular formulations. Other factors may influence market dynamics for individual products—for example, the majority of injectable products are likely, in general, to be used in healthcare institutions and for more severe illness than most other formulations.

While many cases of difficulties in accessing treatment are associated with patent-protected medicines, in some cases, generic medicines may also be priced at very high levels such as in the recent cases involving manufacturers Pfizer, Flynn and Aspen in England. In these cases, manufacturers dramatically increased prices of generic medicines, arguably taking advantage of a dominant position they held in the respective markets.4 5

We aimed to develop an algorithm for estimating the cost of manufacture for injectable medicines on the WHO EML, to use this algorithm to estimate prices that would be expected assuming an average profit margin, and to compare these estimated cost-based prices to current prices in England, South Africa and India. Estimation of cost-based generic prices can contribute to procurement, among other things, by informing negotiations, tenders, price control mechanisms and competition policy.

Methods

In our earlier analysis of SOFs, we developed a costing formula that accounted for capital expenses, the cost of excipients and the cost of formulation into tablets.3 We have also previously developed a costing formula for biosimilars of insulin formulated in vials.6

Here, we developed a similar formula for injectable medicines, and submitted data on the cost of active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) to the formula to generate cost-based estimated generic prices. We then compared these estimated prices to current market prices in three countries—England, South Africa and India. We assume manufacturing in India both because of the fact that India is a major manufacturer of generics globally, and due to the greater availability of data on the bulk prices of API (see below) in India compared with other countries.

Medicines included in the analysis

We analysed medicines listed in the 2015 WHO EML as injectable formulations.7 We use the term ‘item’ to describe an individual medicine-formulation-dosage listing. Besides SOF, we further excluded certain categories of medicines, due both to limitations in reliably identifying API data and/or where we considered that the market would be a special case (eg, blood products). These categories included blood products, diagnostic agents, antivenom, vaccines, simple water-based solutions (eg, 0.9% sodium chloride) and vitamins and minerals, as well as infusion bag formulations and pre-filled syringe formulations. A full list of included and excluded medicines/formulations is available in the online supplementary appendix.

bmjopen-2018-027780supp001.pdf (381KB, pdf)

Cost of active pharmaceutical ingredient

Data on API exported from India were retrieved from an online database of customs declarations (www.infodriveindia.com), a source that we have used in numerous previous analyses of manufacturing costs.3 6 8–12 API shipments in the date range from 1 July 2014 to 1 July 2016 were included, extending the range 2 years into the past if <100 records were returned, and repeating this until at least 100 records were available, or until the timeframe spanned 6 years.

API data were manually cleaned to remove entries that did not represent genuine API (eg, shipments of finished pharmaceutical product; see online supplementary appendix for details), after which a linear regression model, weighted by size in kilograms of individual shipments, was applied to estimate an average API price per kilogram at the data cut-off date (1 July 2016) (see online supplementary appendix for an example).

For some medicines, dosage is expressed as the dose of the active molecule, while the API is sold as a salt form (eg, one vial of ‘80 mg methylprednisolone’ contains 106 mg of methylprednisolone sodium succinate). We adjusted the cost of API needed per unit accordingly.

Statistical analyses of API export data were done in Stata/IC V.14.0 for Mac.

Cost of manufacture of injectables

We have previously estimated cost-based prices that could be achieved in a competitive market for various SOF medicines3 8–12 as well as insulins.6 The cost estimation formula is given in figure 1 and explained further below.

Figure 1.

Formula for estimating cost-based prices for injectable formulations.

The cost of API per dose was calculated as described earlier.

The cost of converting API into a finished pharmaceutical product includes the cost of constructing and operating manufacture sites, raw materials such as glass vials, and process wastage (ie, the proportion of the API that is wasted in the process of formulating it into an finished pharmaceutical product). In general, we aimed to use conservative (high) assumptions in estimating the cost of production. In other words, in designing our costing model, we erred on the side of overestimating the cost of production, in preference to underestimating it. This has the effect of minimising the observed difference in price between current prices and estimated cost-based generic prices, where the former is greater than the latter.

Injectable items in the EML divide broadly into those for which the designated formulation is an ampoule, and those for which the designated formulation is a vial. In some cases, the EML does not indicate whether formulation is as a vial or ampoule—for these items we assumed one or the other based on the more prevalent form found across England, South Africa and India. Such assumptions on whether the medicine is formulated as a vial or ampoule were made for 23% of items. Ampoules are sealed glass containers, while vials generally have a removable cap.

To design conservative assumptions for ampoule/vial formulation costs, we reviewed the lowest-priced products formulated as vials or ampoules in the eMIT database (see next section). These lowest prices are around US$0.20 for ampoules and US$0.50 for vials (online supplementary appendix). We used these values as assumed formulation costs. These are, of course, conservative assumptions, as for those products API costs and operating margins (and transportation costs, taxes, etc.) would have to be zero for the price to represent formulation alone. This is reflected in a recent analysis of the cost of manufacture of vaccines, which estimated the cost of sterile formulation as an ampoule to be around $0.12/unit, and as a vial to be around US$0.35/unit, with these values including raw materials (ie, the vial or ampoule itself), labour, facility and equipment costs, and overheads.13 It is also worth noting that Indian government standards on pharmaceutical manufacturing costs, previously used to inform price ceilings, set allowable costs at a substantially lower level: ampoule costs at $0.03–0.13 and vial costs at $0.05–0.21 (ranges depending on size and type) (online supplementary appendix).

We assumed that 10% more API is needed than the stated dosage, to account for loss of API in the vial/ampoule filling process and vial/ampoule overfill.

We assumed a net profit margin of 10% (the average operating margin in the USA was 12% in 2013).14

Though these cost components are highly variable between countries, an analysis by IMS Health found that costs associated with import (transport, tariffs, other charges) were around 5% in most of the countries surveyed (eg, Brazil, India, Russia).15 Based on this, we added a 10% margin for transportation costs as a conservative assumption.

Prices in England, South Africa and India

Prices were collected in December 2016. Exchange rates used are given in the online supplementary appendix.

For England, prices were collected from the British National Formulary (BNF) and the electronic market information tool (eMit). The BNF lists ‘indicative prices’ and is a reference used by clinicians and pharmacists. eMit provides actual government-purchase prices. The lowest price available across the two sources was used. For South Africa, prices were collected from a database of prices in the public healthcare system as well as a database of prices in the private market, both published by the Department of Health. The lowest price available across the two sources was used. For India, prices reported in public tenders of the state of Tamil Nadu were used. Where prices were not available in this source, we used the price reported in an online database of Indian Maximum Retail Prices. Details on price sources are available in the online supplementary appendix. For South Africa and India, the medicine prices in the sources were assumed to include 15% and 5% value-added tax (VAT), respectively, and price data were adjusted accordingly to be net of VAT. For England, the medicine prices in the sources do not include VAT.

For many medicines in the EML, multiple dosages are listed, and may be interchangeable by using a larger number of smaller-dose items in the place of a larger item, or vice versa. Individual countries may procure larger some volumes of one dosage, but not the other, potentially leading to one dosage having a far higher price than would be expected, due to lower demand volume. To avoid misleading findings as a result of this, for each formulation of each medicine, comparisons between countries and between market prices and cost-based price estimates (for injectables) or API cost (for other formulations) were made for the dosage that gave the lowest difference. Within the context of our analysis this is a conservative approach (yielding smaller differences in comparisons).

Patient and public involvement

The conduct of this study did not involve patients or the public. This study is based on exclusively on publicly available export, price and trade data. Ethical board review was therefore not needed.

Results

Of 414 unique medicines (including combinations) on the 2015 EML, 145 fit the inclusion criteria of this analysis. API data were available for 96 of these 145 medicines (66%) (an example of these data for a single medicine is illustrated in online supplementary appendix figure A1).

Estimated cost-based prices

Estimated cost-based prices ranged from $0.24 (salbutamol 50mcg) to $449 (rituximab 500 mg).

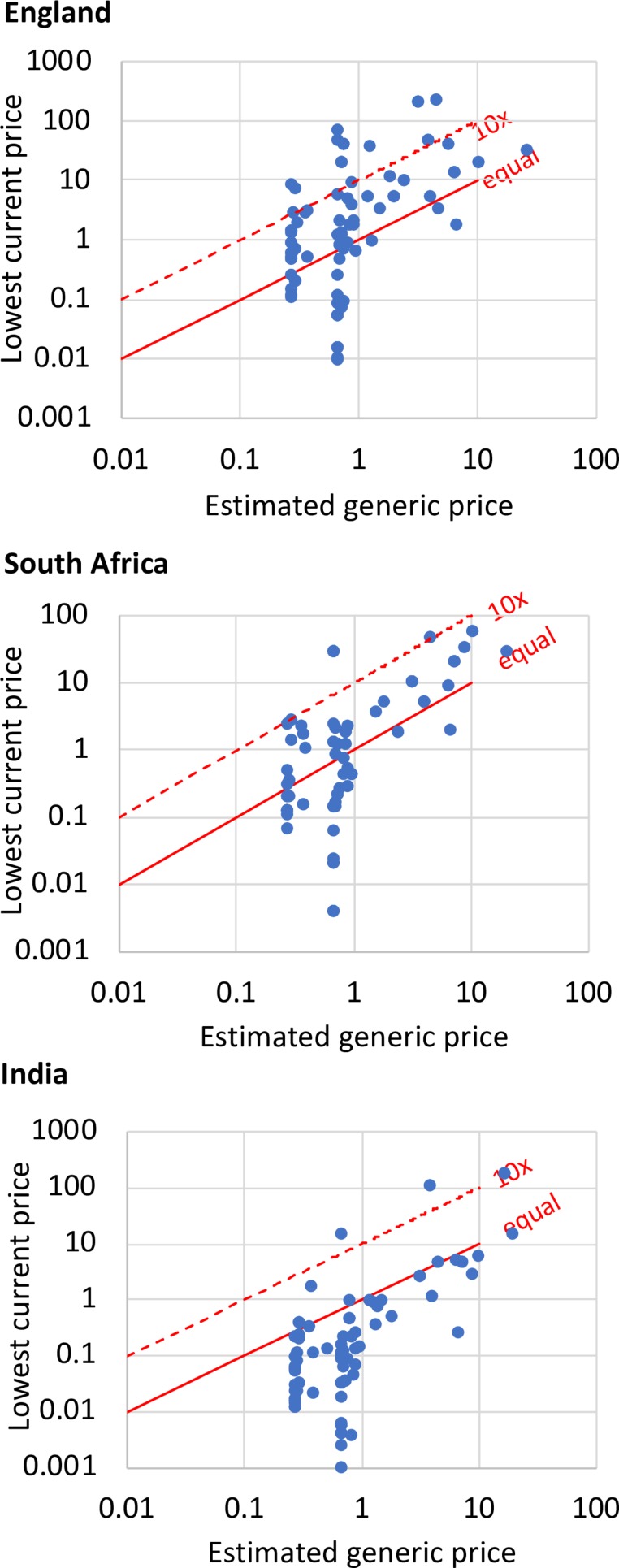

The comparison of lowest current prices in England, South Africa and India to estimated cost-based prices for injectable items is shown in table 1 and figure 2. The majority of injectable items had prices significantly above the estimated cost-based prices in England and South Africa; however, in India, 88% of injectable items had prices below the estimated cost-based price.

Table 1.

Comparison of estimated prices and lowest current prices in England, South Africa and India

| England | South Africa | India | |

| >10 × estimated price | 15 (19%) | 5 (9%) | 4 (5%) |

| 0-10 × estimated price | 47 (58%) | 31 (53%) | 8 (10%) |

| Below estimated price | 19 (23%) | 22 (38%) | 68 (85%) |

| Median ratio of current price to estimated price | 2.54x | 1.48x | 0.30x |

Multiple dosage levels of one formulation of one medicine (eg, ifosfamide powder for injection in 1 g and 2 g forms) are counted as one instance in these overview statistics.

Figure 2.

Estimated generic prices and current prices for injectables in England, South Africa and India.

The items with the highest ratios of lowest current price to estimated cost-based price are shown for England in table 2, for South Africa in table 3 and for India in table 4.

Table 2.

Injectable essential medicines with the highest ratios of lowest current price versus estimated cost-based price, in England

| Medicine | Unit | Lowest current price (US$) | Estimated cost-based price (US$) | Ratio |

| Irinotecan | 5 mL vial (100 mg) | 143.81 | 1.17 | 122.7 |

| Filgrastim | 1 mL vial (300mcg) | 68.52 | 0.61 | 112.6 |

| Ibuprofen | 1 mL injection (5 mg) | 46.80 | 0.61 | 77.3 |

| Daunorubicin | Powder for injection (50 mg) | 211.25 | 2.88 | 73.4 |

| Azathioprine | Powder for injection (100 mg) | 39.99 | 0.66 | 60.5 |

| Ifosfamide | Powder for injection (2 g) | 233.84 | 4.10 | 57.1 |

| Ifosfamide | Powder for injection (1 g) | 118.72 | 2.35 | 50.5 |

| Ifosfamide | Powder for injection (500 mg) | 59.35 | 1.48 | 40.2 |

| Mesna | 10 mL ampoule (1000 mg) | 38.23 | 1.13 | 33.9 |

| Atropine | 1 mL ampoule (1 mg) | 8.25 | 0.24 | 33.7 |

| Ampicillin | powder for injection (1000 mg) | 20.36 | 0.64 | 31.6 |

| Mesna | 4 mL ampoule (400 mg) | 17.43 | 0.60 | 29.2 |

| Phenobarbital | 1 mL injection (200 mg) | 7.32 | 0.26 | 27.7 |

| Epinephrine | 10 mL ampoule (1 mg) | 6.97 | 0.27 | 26.1 |

| Valproic acid | 4 mL ampoule (400 mg) | 5.09 | 0.26 | 19.9 |

| Zidovudine | 20 mL vial (200 mg) | 11.60 | 0.67 | 17.3 |

| Ampicillin | Powder for injection (500 mg) | 10.18 | 0.62 | 16.3 |

| Irinotecan | 25 mL vial (500 mg) | 46.83 | 3.44 | 13.6 |

| Ketamine | 10 mL vial (500 mg) | 9.10 | 0.79 | 11.4 |

| Hydralazine | Powder for injection (20 mg) | 2.88 | 0.25 | 11.4 |

Table 3.

Injectable essential medicines with the highest ratios of lowest current price versus estimated cost-based price, in South Africa

| Medicine | Unit | Lowest current price (US$) | Estimated cost-based price (US$) | Ratio |

| Filgrastim | 1 mL vial (300 mcg) | 32.38 | 0.61 | 46.3 |

| Tranexamic acid | 10 mL ampoule (1000 mg) | 8.47 | 0.37 | 23.0 |

| Ifosfamide | Powder for injection (1 g) | 28.71 | 2.35 | 12.2 |

| Ifosfamide | Powder for injection (2 g) | 48.71 | 4.10 | 11.9 |

| Ifosfamide | Powder for injection (500 mg) | 17.22 | 1.48 | 11.7 |

| Streptokinase | Powder for injection (15.6 mg) | 223.93 | 19.60 | 11.4 |

| Amiodarone | Ampoule (150 mg/3 mL) | 2.87 | 0.27 | 10.7 |

| Digoxin | 2 mL ampoule (500mcg) | 2.44 | 0.25 | 9.9 |

| Fluphenazine | 1 mL ampoule (25 mg) | 2.30 | 0.32 | 7.1 |

| Oxaliplatin | Powder for injection (100 mg) | 59.76 | 9.10 | 6.6 |

| Oxaliplatin | Powder for injection (50 mg) | 29.88 | 4.85 | 6.2 |

| Magnesium sulfate | 10 mL ampoule (5 g) | 1.36 | 0.26 | 5.2 |

| Ciclosporin | 1 mL ampoule (50 mg) | 1.72 | 0.33 | 5.2 |

| Docetaxel | Injection (20 mg) | 21.70 | 4.21 | 5.1 |

| Docetaxel | Injection (40 mg) | 34.29 | 7.82 | 4.4 |

| Mesna | 4 mL ampoule (400 mg) | 2.40 | 0.60 | 4.0 |

| Daunorubicin | Powder for injeciton (50 mg) | 10.03 | 2.88 | 3.5 |

| Vincristine | Powder for injection (5 mg) | 13.92 | 4.15 | 3.4 |

| Aciclovir | Powder for injection (250 mg) | 2.10 | 0.63 | 3.3 |

| Quinine | 2 mL ampoule (600 mg) | 1.10 | 0.34 | 3.2 |

Table 4.

Injectable essential medicines with the highest ratios of lowest current price versus estimated cost-based price, in India

| Medicine | Unit | Lowest current price (US$) | Estimated cost-based price (US$) | Ratio |

| Irinotecan | 25 mL vial (500 mg) | 107.14 | 3.44 | 31.1 |

| Filgrastim | 1 mL vial (300mcg) | 15.71 | 0.61 | 25.8 |

| Irinotecan | 5 mL vial (100 mg) | 21.43 | 1.17 | 18.3 |

| Irinotecan | 2 mL vial (40 mg) | 10.71 | 0.83 | 12.9 |

| Bendamustine | 2 mL injection (180 mg) | 185.14 | 15.05 | 12.3 |

| Bendamustine | 0.5 mL injection (45 mg) | 46.29 | 4.22 | 11.0 |

| Valproic acid (sodium valproate) | 10 mL ampoule (1 g) | 2.86 | 0.28 | 10.3 |

| Ciclosporin | 1 mL ampoule (50 mg) | 1.71 | 0.33 | 5.2 |

| Testosterone | 1 mL ampoule (200 mg) | 1.34 | 0.27 | 4.9 |

| Valproic acid (sodium valproate) | 4 mL ampoule (400 mg) | 1.14 | 0.26 | 4.5 |

| Insulin injection (soluble) | 10 mL injection (34.7 mg) | 5.80 | 2.15 | 2.7 |

| Sodium nitroprusside | Powder for injection (50 mg) | 0.64 | 0.25 | 2.5 |

All other items for which ratios could be calculated had ratios below 2.0.

Therapeutic categories with notably higher ratios of lowest current price to estimated cost-based price included cardiovascular medicines, medicines for mental and behavioural disorders, hormones, other endocrine medicines and contraceptives, anticonvulsants/antiepileptics, antineoplastics and immunosuppressives, and oxytocics (online supplementary appendix).

International price comparisons

International comparisons of lowest current prices for injectable essential medicines are shown in figure 3. Prices were higher in England than in South Africa in 60% of comparisons, with a median ratio of 1.44; higher in England than in India in 91% of comparisons, with a median ratio of 7.08; and higher in South Africa than in India in 84% of comparisons, with a median ratio of 3.69 (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of lowest current prices of injectable essential medicines between England, South Africa, and India.

Discussion

For injectable formulations on the WHO EML, 77% of medicines had prices above the estimated cost-based price in England, and 62% had prices above the estimated cost-based price in South Africa, while 85% of medicines in India had prices below estimated cost-based price. 19% of injectable medicines in England, 9% in South Africa and 5% in India had prices more than 10 times the estimated cost-based price (table 1, figure 2).

A few medicines were notable for appearing in the top-20 lists by ratio of current price to estimated cost-based price in more than one country (tables 2–4): numerous oncology medicines—irinotecan, ifosfamide, daunorubicin, filgrastim, and mesna—as well as the certain antimicrobials (ampicillin, acyclovir, quinine), valproic acid (an anti-epileptic) and ciclosporin (an immunosuppressant).

A wide range of market factors may contribute to their greater than average difference in manufacture costs and price (price-to-cost ratio). The ‘top 20’ injectable medicines are all mostly used in the in-patient hospital setting, are used in specialist treatments, are second/third-line treatments and/or are used for short durations. These characteristics would all tend to reduce demand volumes, reduce economies of scale (both in manufacture and distribution) and reduce the buyer’s negotiating power, and may thus explain the high prices relative to manufacture costs.

Differences between countries in the ratios of lowest current price to estimated cost-based generic price, similarly, may be explained by a wide range of factors. A detailed comparison of pharmaceutical market characteristics of the three countries is beyond the scope of this study. India is a substantially larger market than England and South Africa, and this difference in volume of demand may play a role. Differences in regulatory requirements are also likely to play a significant role. India has a large local generic manufacturing sector, far larger than in the other two countries. There may be a comparatively greater emphasis on these ‘essential’ products in South Africa and India, compared with England, as there is in general a lesser range of products available for use, for most patients, in these countries. Finally, some of the higher-cost drugs for which prices were identified for England were not found in the Indian databases, which leads to a degree of ‘selection bias’, wherein for the India comparison, a higher proportion of available datapoints are for lower-cost drugs than for the UK.

Most of the medicines compared in this analysis are no longer under patent protection in England, South Africa or India.16 Varying levels of competition across products and countries may also influence prices. This analysis does not account for differing volumes related to market size and related efficiencies. However, in some cases, high prices for generic medicines may be explained by anticompetitive practices, or price hikes where a single supplier controls the market. This analysis is unable to detect the presence of anticompetitive strategies which may raise prices such as price fixing or upstream consolidation or collusion. The extent of these practices is unknown, but, as this year’s lawsuit brought by 44 state Attorney Generals in the USA against 20 generics manufacturers demonstrates, anticompetitive practices may be prevalent in certain pharmaceutical markets.17

Given the range of medicines included, it is difficult to make generalised comments. If cost of manufacture analysis were employed by governments to evaluate prices, large differences between current prices and estimated cost-based prices could trigger closer examination on a case-by-case basis. Some EML medicines, such as filgrastim, which appears in the ‘top 20’ in all three countries, are biologics, meaning different regulations and higher regulatory expenses may apply. In such cases, large profit margins may be more acceptable. In other cases, ibuprofen (5 mg in 1 mL injection) and ampicillin (1000 mg powder for injection) in England may reflect insufficient competition, inefficient procurement or a less commonly used dosage form (table 2). Some of these ‘top 20’ medicines may represent a substantial burden on healthcare expenditures—for example, irinotecan represented expenditures of £22 million (about US$29 million) by the public healthcare system in England in 2016/2017.18

Current lowest prices in India were on average lower than our estimated cost-based prices (lowest current prices in India were median 27% of the estimated cost-based price; table 1 and figure 2). This may reflect conservative assumptions made for the cost of ampoules and vials; a substantial number of items cost less than our assumed raw material cost for the ampoule/vial (primary packaging) alone, which we based on prices in high-income countries (see Figure A2 in the online supplementary appendix). It may also reflect the general conservative (overestimating) effect of using data on exported API; API that is manufactured in-house or procured domestically may have lower prices. The use of an average API price (rather than, for example, lowest observed or first-quartile) means, in most cases, that a number of API sales occurred at lower price points. Finally, Indian prices were collected from two databases—one representing the private market and one representing Tamil Nadu state tenders (the lower price of the two was recorded). State tender prices are likely lower than private market prices, but the majority of health expenditures in India are out-of-pocket, and of these the majority are on medicines.19 In addition, there are wide variations in wealth and access to health insurance between Indian states. The methodological approach of seeking the lowest available price in each country means that the price faced by patients when paying out-of-pocket in the private market may be considerably higher.

In our earlier analysis of SOF medicines in the EML, we found that 77% comparable prices in England, 67% comparable prices in South Africa and 40% comparable prices in India were above the estimated cost-based price. Median ratios for lowest current price to estimated cost-based price were 2.7x in England, 1.4x in South Africa and 0.6x in India.3 These ratios are notably similar to the comparisons in this analysis between lowest current prices and estimated cost-based prices for injectables (2.5x in England, 1.5x in South Africa and 0.3x in India; table 1).

Analysis of the cost of production of medicines can be used in government price negotiations, price control mechanisms or in competition law contexts. In India, until 2013, a formula based on the cost of manufacture was used to set ceiling prices on key medicines.20 21 A similar approach has been used in Bangladesh, Pakistan and China.21 In South African tenders, manufacturers are required to submit breakdowns of their price by various cost components including API cost and profit margin.22 The WHO Guideline on Pharmaceutical Pricing Policies notes that the use of cost-plus formulae may be challenging to implement due to challenges on obtaining accurate data on material prices on manufacturing costs, and due to the potential for manipulation of data by manufacturers to exaggerate costs and justify higher prices.21 Indeed, in this analysis, the Indian government requirement for the publication of customs data on the value of exported API has been revoked since we collected data, meaning that at present the authors are not aware of an alternative, affordable source of data for API costs.23 Nevertheless, cost of manufacture analysis should be explored further as a component of pricing policies.

Pricing policies linked to manufacturer costs would also need to be used alongside policies to prevent shortages and stock-outs.24 Indeed, some of the therapeutic groups identified in this analysis as having in many cases high differences between market prices and estimated cost-based prices, such as chemotherapy medicines and antibiotics, may also be groups that are vulnerable to shortages.25 26

This study, which used broad and conservative assumptions, can be seen as an initial exploration of the feasibility of estimating cost-based generic prices for injectables. As there is considerable variation among items listed in the EML, a tailored approach could be used to improve the precision and confidence of the estimate for specific products, for example, those identified here as having high price-to-cost ratios.

Limitations

The main limitation of our analysis is that our estimates do not account for differences of costs across individual manufacturing plants due to heterogeneity in, for example, location, machinery used, and capacity, as well as different distribution costs (including tariffs) depending on the country of manufacture and the importing country, and changes in conversion cost depending on the volume of the unit. As argued earlier, this limitation would not preclude the use of a methodology such as this one to identify medicines that may have high profit margins, for closer ad hoc analysis.

Although prices in India were adjusted to be net of VAT, other state-level taxes may apply and these were not adjusted for.

In the previous analysis concerning SOFs on the WHO EML, in which many elements of the methodology were identical (eg, cost analysis for API, tax and profit assumptions), the estimated cost-based generic prices were compared with the lowest available prices for key HIV, tuberculosis (TB) and malaria treatments (prices in these disease areas were used, as there are well-developed international procurement mechanisms for quality-assured generic products, and procurement prices are transparently reported). In this validation exercise, predictive accuracy between estimated cost-based generic price and actual global market prices was high.27 However, medicines for HIV, TB and malaria are predominantly SOFs. We have thus not attempted to conduct a similar validation exercise for the estimated cost-based prices presented in this study, for lack of a data set to be used for comparison. As noted, however, we consider the individual assumptions made for cost components to be conservative (high).

Data collection for this analysis finished shortly before the publication in April 2017 of the 2017 EML. The EML is published biennially; we used the most recent iteration at the time of data analysis, the 2015 EML.

Conclusion

Most injectable medicines on the EML can be manufactured at very low cost. In England, about one in five injectable essential medicines was priced at more than 10 times the estimated cost-based price. In South Africa, this proportion was about one in ten, and in India, about one in twenty. Estimation of the cost of manufacture could be used in government pharmaceutical pricing mechanisms, for example, by identifying products for which profit margins may be significantly above average.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: DG, MJB, and AMH designed the study, interpreted the data and critically reviewed the manuscript. MJB and DG collected and analysed the data.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: DG reports personal fees for unrelated work from the Medicines Patent Pool, the Wellcome Trust, Treatment Action Group and the World Health Organization. MJB and AMH report no conflicts of interest.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Wirtz VJ, Hogerzeil HV, Gray AL, et al. Essential medicines for universal health coverage. The Lancet 2017;389:403–76. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31599-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization Revised procedure for updating WHO’s Model List of Essential Drugs, 2001. Available: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s22165en/s22165en.pdf [Accessed 8 Mar 2018].

- 3. Hill AM, Barber MJ, Gotham D. Estimated costs of production and potential prices for the who essential medicines list. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000571 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kenber B. Drug firm is facing fine of £220m for hiking prices In: The Times, 2017. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/drug-firm-faces-fine-of-220m-for-hiking-prices-gf0ssclqk [Google Scholar]

- 5. Competition and Markets Authority CMA fines pfizer and Flynn £90 million for drug price hike to NHS. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/cma-fines-pfizer-and-flynn-90-million-for-drug-price-hike-to-nhs [Accessed 28 Oct 2018].

- 6. Gotham D, Barber MJ, Hill A. Production costs and potential prices for biosimilars of human insulin and insulin analogues. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000850 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization 19Th who model list of essential medicines, 2015. Available: http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/EML2015_8-May-15.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed 28 Jan 2016].

- 8. Hill A, Gotham D, Cooke G, et al. Analysis of minimum target prices for production of entecavir to treat hepatitis B in high- and low-income countries. J Virus Erad 2015;1:103–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hill A, Gotham D, Fortunak J, et al. Target prices for mass production of tyrosine kinase inhibitors for global cancer treatment. BMJ Open 2016;6:e009586 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hill A, Simmons B, Gotham D, et al. Rapid reductions in prices for generic sofosbuvir and daclatasvir to treat hepatitis C. J Virus Erad 2016;2:28–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hill A, Redd C, Gotham D, et al. Estimated generic prices of cancer medicines deemed cost-ineffective in England: a cost estimation analysis. BMJ Open 2017;7:e011965 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gotham D, Fortunak J, Pozniak A, et al. Estimated generic prices for novel treatments for drug-resistant tuberculosis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017;72 dkw522 10.1093/jac/dkw522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sedita J, Perrella S, Morio M, et al. Cost of goods sold and total cost of delivery for oral and parenteral vaccine packaging formats. Vaccine 2018;36:1700–9. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Karamehic J, Ridic O, Ridic G, et al. Financial aspects and the future of the pharmaceutical industry in the United States of America. Mater Sociomed 2013;25:286–90. 10.5455/msm.2013.25.286-290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics Understanding the pharmaceutical value chain, 2014. Available: https://www.ifpma.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/IIHI_Report_Pharma_Value.pdf

- 16. Medicines Patent Pool MedsPaL. Available: http://www.medspal.org/ [Accessed 28 Feb 2018].

- 17. Murphy H. "Teva and other generic drugmakers inflated prices up to 1000%, State Prosecutors say" In: The New York Times, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/11/health/teva-price-fixing-lawsuit.html (11 May 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 18. Digital NHS. Prescribing costs in hospitals and the community, England 2016/17: NICE data. Available: https://files.digital.nhs.uk/publication/n/0/hosp-pres-eng-201617-nicedata.csv [Accessed 28 Oct 2018].

- 19. Garg CC, Karan AK. Reducing out-of-pocket expenditures to reduce poverty: a disaggregated analysis at rural-urban and state level in India. Health Policy Plan 2009;24:116–28. 10.1093/heapol/czn046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kotwani A, Levison L. Price components and access to medicines in Delhi, India, 2007. Available: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s19208en/s19208en.pdf

- 21. World Health Organization WHO guidelines on country pharmaceutical pricing policies, 2015. Available: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s21016en/s21016en.pdf

- 22. Republic of South Africa National Department of Health Special Requirements and Conditions of Contract. HP09–2016SD/01 In: The supply and delivery of solid dosage forms to the Department of health for the period up to 31 July 2018, 2017. http://www.health.gov.za/tender/docs/contructs/HP092016SD01ContractCircular.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 23. Central Board of Excise and Customs Notification No. 140/2016. Available: https://www.seair.co.in/custom-notifications/notifications-issued-in-the-year-2016-notification-no-1402016-dated-25th-nov-2016-268128.aspx [Accessed 4 Apr 2017].

- 24. World Health Organization Medicines shortages: global approaches to addressing shortages of essential medicines in health systems. WHO Drug Inf 2016;30. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gray A, Manasse HR. Shortages of medicines: a complex global challenge. Bull World Health Organ 2012;90:158 10.2471/BLT.11.101303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Iyengar S, Hedman L, Forte G, et al. Medicine shortages: a commentary on causes and mitigation strategies. BMC Med 2016;14:124 10.1186/s12916-016-0674-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hill A, Barber M, Gotham D, et al. Generic treatments for HIV, HBV, HCV, TB could be mass produced for <$90 per patient : 9Th IAS conference on HIV science. Paris, 2017. http://programme.ias2017.org/Abstract/Abstract/1978 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-027780supp001.pdf (381KB, pdf)