Abstract

Objective:

To determine risk factors associated with cesarean delivery among nulliparous women in spontaneous labor with a single, cephalic, term pregnancy (Robson group 1).

Methods:

Data were assessed from the WHO Global Survey of Maternal and Perinatal Health conducted in 2004–2008.

Results:

Among 82 280 women in Robson group 1, 67 698 (82.3%) had vaginal and 14 578 (17.7%) had cesarean delivery. In adjusted analyses, maternal factors associated with cesarean included age older than 18 years, being overweight or obese, being married or cohabitating, attending four prenatal visits or more, and being medically high risk (P<0.001). Women who were obstetrically high risk, referred during labor, or at 39 gestational weeks or more were also more likely to undergo cesarean (all P<0.001). Facility-level factors associated with cesarean were availability of an anesthesia service 24/7, being a teaching facility, requirement of fees for cesarean, availability of electronic fetal monitoring, and having providers skilled in operative vaginal delivery (all P<0.01).

Conclusion:

The analysis highlights the importance of maintaining a healthy pre-pregnancy and pregnancy weight, optimizing management of women with medical problems, and ensuring clear referral mechanisms for women with intrapartum complications. The association between fees and cesarean delivery warrants further exploration.

Keywords: Cesarean delivery, Low- and middle-income countries, Low-risk pregnancy, Mode of delivery, Risk factors, Robson classification, WHOGS

1. INTRODUCTION

The rates of cesarean delivery are increasing globally [1]. The WHO has recommended use of the Robson classification system to better understand these rising rates [2]. This classification system is based on common obstetric variables normally used in the clinical care of laboring women (parity, history of prior cesarean, onset of labor, number of fetuses, gestational age, fetal lie, and presentation), and categorizes women admitted for delivery into 10 mutually exclusive, all-inclusive groups [2].

Classifying women in this way has shown that nulliparous women with single, cephalic, term pregnancies (Robson group 1) tend to be one of the largest contributors to the overall rise in cesarean delivery [3, 4]. As a result, there is a heightened focus on reducing primary cesarean delivery, and on developing interventions to prevent unnecessary primary cesarean, as a strategy to reduce the frequency of this procedure [4].

It is likely that there are additional actionable, modifiable risk factors associated with cesarean delivery in the Robson group 1 population that can be explored [3, 5, 6]. As such, the aim of the present study was to conduct a secondary analysis of the WHO Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health dataset comparing sociodemographic, obstetric, labor, and facility-level factors between women in Robson group 1 who went into labor spontaneously and delivered vaginally and those who went into labor spontaneously but delivered by cesarean [7].

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was a secondary analysis of WHO Global Survey of Maternal and Perinatal Health (WHOGS) data, which was prospectively collected from September 1, 2004 to August 15, 2005 (in eight Latin America and seven African countries) and from October 2007 to May 2008 (in nine Asian countries) [7]. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Specialist Panel on Epidemiological Research and the WHO ethics review committee, as well as relevant ethical clearance bodies in participating countries and facilities. The de-identified data analysis plan was reviewed and approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (no. 18–0875).

The methodology of the WHOGS has been published [7]. In brief, the multi-country, facility-based survey collected data on all women who delivered in randomly selected facilities and countries [8]. Sampling was done by a stratified multistage cluster design: in each country, the capital city and two other regions were randomly selected [8]. Up to seven facilities with more than 1000 deliveries per year and cesarean delivery capability were included [8]. Facilities with more than 6000 annual deliveries collected data for 2 months; those with fewer than 6000 collected data for 3 months [8].

De-identified data, including sociodemographic, obstetric, labor, and delivery characteristics, and a range of maternal and perinatal outcomes, were captured from all women who delivered in the participating institutions during the data collection period [7]. Data extracted from 290 610 deliveries in 373 facilities in 24 countries were included in the final dataset [7]. Data were collected prospectively from the time of maternal presentation at the facility until discharge, death, or day 7 postpartum, whichever occurred first [7]. Data collectors reviewed medical records daily and abstracted de-identified data from these records into an individual data form [7]. In addition, an institutional data form was completed for each participating facility via an interview with the head of the obstetrics and gynecology department [7]. Ethical approval for the original survey was obtained from the WHO, within each country, and also the Ministry of Health [8].

For the present analysis, WHOGS data on women in Robson group 1 (nulliparous women at term with a singleton fetus in cephalic presentation who go into labor spontaneously) were analyzed. The primary outcome was mode of delivery. Women who experienced vaginal delivery were compared with those who underwent cesarean delivery to determine risk factors associated with cesarean delivery.

The covariates considered were sociodemographic characteristics (age, education, body mass index [BMI, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters], marital status, and 2008 human development index (HDI) of the country where the woman delivered), prenatal profile (number of visits and medical risk level), and obstetric profile (obstetric complications, referral to a higher level of care during labor, and gestational age) [9]. The facility-level covariates were availability of a partogram, availability of anesthesia 24/7, availability of electronic fetal monitoring, whether the facility was a teaching hospital, whether it levied fees for cesarean delivery, and whether providers in the facility were skilled in operative vaginal delivery.

Women were categorized as “high” maternal medical risk if the survey reported that they had HIV infection, chronic hypertension, cardiac or renal disease, respiratory disease, diabetes, malaria, anemia, urinary tract infection, genital ulcers, condyloma, or thalassemia; this pragmatic definition was devised specifically for the present analysis and has not been defined elsewhere. Obstetric risk was categorized as “high” for women who experienced pregnancy-related hypertension, pre-eclampsia, or eclampsia, or had suspected fetal growth impairment. This definition was also devised specifically for the present analysis.

Stata software version 15.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for data analysis. Covariates were analyzed by mode of delivery in bivariate analyses and multivariable analyses that were adjusted for country and delivery facility. Variables significant in the bivariate analysis at a P value of less than 0.05 were included in the multivariable model. Given the large sample size and multiple comparisons, a P value of less than 0.01 (bivariate logistic regression adjusted for multi-level random effects) was used to determine statistical significance.

3. RESULTS

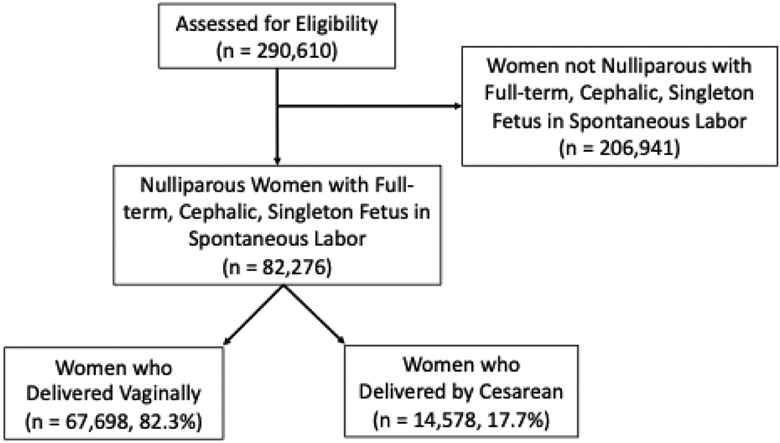

Among data from 286 565 deliveries documented in the WHOGS, 82 280 (28.7%) were from women in Robson group 1 and formed the basis of the present analysis. Of these, 67 698 (82.3%) women delivered vaginally, and 14 578 (17.7%) delivered by primary cesarean (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram showing the study population.

Sociodemographic, maternal, obstetric, and delivery characteristics of the study women, and facility-level factors were compared between the women who delivered vaginally and those who delivered by cesarean (Table 1). All comparisons were adjusted for multi-level random effects accounting for country and facility where the woman delivered.

Table 1.

Maternal characteristics and facility-level factors by mode of delivery among the study populationa.

| Characteristic or factor | Vaginal (n=67 698) | Cesarean (n=14 578) | P value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal | |||

| Age, y | <0.001 | ||

| No. of data | 67 698 | 14 578 | |

| ≤18 | 12 971 (19.2) | 2024 (13.9) | |

| 19–34 | 53 505 (79.0) | 11 956 (82.0) | |

| ≥35 | 1222 (1.8) | 598 (4.1) | |

| Education, y | <0.001 | ||

| No. of data | 67 698 | 14 578 | |

| 0–6 | 14 832 (21.9) | 2657 (18.2) | |

| 7–12 | 39 618 (58.5) | 8340 (57.2) | |

| ≥13 | 13 248 (19.6) | 3581 (24.6) | |

| BMI | <0.001 | ||

| No. of data | 66 721 | 14,336 | |

| <18.5 | 745 (1.1) | 83 (0.6) | |

| 18.5–24.9 | 26 012 (39.0) | 3986 (27.8) | |

| 25.0–29.9 | 22 621 (33.9) | 5968 (41.6) | |

| ≥30.0 | 17 343 (26.0) | 4299 (30.0%) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | ||

| No. of data | 67 505 | 14 543 | |

| Singlec | 13 582 (20.1) | 2106 (14.5) | |

| Married, cohabitating | 53 923 (79.9) | 12 437 (85.5) | |

| Prenatal visits | <0.001 | ||

| No. of data | 67 698 | 14 578 | |

| <4 | 18 510 (27.3) | 2708 (18.6) | |

| ≥4 | 49 188 (72.7) | 11 870 (81.4) | |

| Medically high riskd | <0.001 | ||

| No. of data | 67 698 | 14 578 | |

| Yes | 9898 (14.6) | 2834 (19.4) | |

| HDI 2008 | 0.006 | ||

| No. of data | 67 698 | 14 578 | |

| Low | 5877 (8.7) | 533 (3.7) | |

| Medium | 48 236 (71.3) | 10 845 (74.4) | |

| High | 13 585 (20.1) | 3200 (21.9) | |

| Obstetric and labor | |||

| Obstetrically high riske | <0.001 | ||

| Total no. of data | 67 698 | 14 578 | |

| Yes | 2821 (4.2) | 1363 (9.4) | |

| Referred during labor | n = | <0.001 | |

| Total no. of data | 67 689 | 14 575 | |

| Yes | 12 100 (17.9) | 3,617 (24.8) | |

| GA at delivery, wk | <0.001 | ||

| Total no. of data | 67 698 | 14 578 | |

| 37–38+6 | 21 712 (32.1) | 3907 (26.8) | |

| 39–40+6 | 39 879 (58.9) | 8435 (57.9) | |

| ≥41 | 6107 (9.0) | 2236 (15.3) | |

| Facility-level factors | |||

| Electronic fetal monitor available | <0.001 | ||

| Total no. of data | 67 695 | 14 578 | |

| Yes | 45 547 (67.3) | 11 940 (81.9) | |

| Anesthesia 24/7 in facility | <0.001 | ||

| Total no. of data | 67 692 | 14 578 | |

| Yes | 47 962 (70.9) | 12 301 (84.4) | |

| Provider skilled in operative vaginal deliveryf | <0.001 | ||

| Total no. of data | 67 698 | 14 578 | |

| Yes | 59 739 (88.2) | 13 522 (92.8) | |

| Teaching facility | <0.001 | ||

| Total no. of data | 67 348 | 14 577 | |

| Yes | 50 091 (74.4) | 12 053 (82.7) | |

| Fees levied for cesarean | 0.001 | ||

| Total no. of data | 66 568 | 14 489 | |

| Yes | 37 993 (57.1) | 9 193 (63.5) | |

| Partogram available | 0.028 | ||

| Total no. of data | 66 695 | 14 578 | |

| Yes | 60 344 (89.1) | 13 367 (91.7) | |

| Woman to bring/pay for surgical equipment for cesarean | 0.057 | ||

| Total no. of data | 67 695 | 14 578 | |

| Yes | 22 757 (33.6) | 3938 (27.0) | |

| Intrapartum guidelines available | 0.124 | ||

| Total no. of data | 67 555 | 14 571 | |

| Yes | 56 595 (83.8) | 13 062 (89.6) | |

| Fetal scalp pH sampling available | 0.157 | ||

| Total no. of data | 67 521 | 14 571 | |

| Yes | 8255 (12.2) | 3029 (20.8) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters); GA, gestational age; HDI, human development index.

Values are given as absolute number or number (percentage).

Bivariate comparison adjusted for multi-level random effects at country and facility level.

Includes single, separated, divorced, widowed, and other.

Women were considered to be medically high risk if they had chronic hypertension, cardiac or renal disease, pulmonary pathology, diabetes, malaria, sickle cell disease, severe anemia, urinary tract infection, severe condylomatous disease, HIV or a condition associated with HIV infection, or thalassemia.

Women were considered obstetrically high risk if they experienced hypertension in pregnancy, pre-eclampsia, or eclampsia, or had suspected fetal growth impairment.

Includes forceps and vacuum vaginal delivery.

The rate of cesarean delivery was higher for women older than 18 years (versus ≤18 years), women with 13 years or more of education, women with a BMI of 25.0 or greater, and women who were married or cohabitating (versus single women) (all P<0.001). In addition, women who attended four or more prenatal care visits (versus <4 visits), were medically high risk, were referred during the course of labor to a higher level of care, were obstetrically high risk, or delivered in a medium or high HDI country also had higher rates of cesarean delivery (all P<0.001). Lastly, women with a gestational age of 41 weeks or longer had a higher rate of delivery by cesarean as compared with women who were at term (P<0.001).

Facility-level factors associated with a higher rate of cesarean delivery among Robson group 1 women included availability of electronic fetal monitoring, 24/7 availability of anesthesia, having providers skilled in operative vaginal delivery (forceps or vacuum), being a teaching facility, and requiring women to pay fees for cesarean delivery (all P<0.01).

To identify risk factors associated with cesarean delivery, unadjusted and adjusted multi-level random effects logistic regression analyses adjusted for country and facility of delivery were performed (Table 2). All covariates that were significant in the bivariate comparisons (Table 1) also increased the likelihood of cesarean in the multivariate model, except for educational level and HDI of participating country. Age older than 18 years increased the likelihood of cesarean delivery by at least 30%, overweight or obese BMI by at least 50%, and married or cohabitating status by 10% (all P<0.01). Of note, age older than or equal to 35 years was increased the odds of cesarean 3.4-fold as compared with age 18 years or under (95% confidence interval [CI], 3.0–3.8; P<0.001). Attending more prenatal visits (≥4) and being medically high risk both increased the odds of cesarean by 20% (P<0.001). Lastly, being referred during labor, having an obstetrically high-risk condition, or a gestational age of more than 39 weeks increased the odds of cesarean by 60%, 110%, and at least 10%, respectively (P<0.001).

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of risk factors for cesarean delivery among Robson group 1 women.

| Factor | Adjusted analysis | Unadjusted analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P valuea | |

| Maternal | ||||

| Age, y | ||||

| 18 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| 19–34 | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | <0.001 | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) | <0.001 |

| ≥35 | 3.4 (3.0–3.8) | <0.001 | 3.8 (3.3–4.2) | <0.001 |

| Education, y | ||||

| 0–6 | ||||

| 7–12 | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) | 0.069 | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 0.201 |

| ≥13 | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.036 | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | <0.001 |

| BMI | ||||

| <18.5 | 0.7 (0.5,0.9) | 0.002 | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | 0.002 |

| 18.5–24.9 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| 25.0–29.9 | 1.5 (1.5–1.6) | <0.001 | 1.6 (1.5–1.7) | <0.001 |

| ≥30.0 | 2.2 (2.0–2.4) | <0.001 | 2.4 (2.3–2.6) | <0.001 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Singleb | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) | <0.001 | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) | <0.001 |

| Married/cohabitating | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Prenatal visits ≥4 | 1.2 (1.2–1.3) | <0.001 | 1.3 (1.3–1.4) | <0.001 |

| Medically high riskc | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | <0.001 | 1.4 (1.3–1.4) | <0.001 |

| HDI 2008 | ||||

| Low | 0.7 (0.2–1.8) | 0.431 | 0.2 (0.1–0.5) | 0.001 |

| Medium | 1.4 (0.7–2.8) | 0.384 | 0.9 (0.4–2.0) | 0.770 |

| High | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Obstetric factors | ||||

| Referred during labor | 1.6 (1.5–1.7) | <0.001 | 1.7 (1.6–1.8) | <0.001 |

| Obstetrically high riskd | 2.1 (2.0–2.3) | <0.001 | 2.3 (2.1–2.5) | <0.001 |

| GA at delivery, wk | ||||

| 37–38+6 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 39–40+6 | 1.1 (1.1–1.2) | <0.001 | 1.1 (1.1–1.2) | <0.001 |

| ≥41 | 1.9 (1.8–2.0) | <0.001 | 1.9 (1.8–2.0) | <0.001 |

| Facility-level factors | ||||

| Partogram available | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 0.921 | 1.5 (1.0–2.1) | 0.028 |

| Anesthesia 24/7 in facility | 1.5 (1.1–1.9) | 0.009 | 2.3 (1.7–3.0) | <0.001 |

| Teaching facility | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) | 0.002 | 2.2 (1.7–2.9) | <0.001 |

| Fees levied for cesarean | 1.5 (1.1–1.9) | 0.009 | 1.8 (1.3–2.4) | 0.001 |

| Electronic fetal monitor available | 1.6 (1.2–2.2) | 0.003 | 2.7 (2.0–3.6) | <0.001 |

| Provider skilled in operative vaginal deliverye | 2.1 (1.5–3.0) | <0.001 | 3.5 (2.4–5.1) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted OR; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters); CI, confidence interval; GA, gestational age; HDI, human development index; OR, odds ratio.

Multivariable model adjusted for multi-level random effects at country and facility level.

Includes single, separated, divorced, widowed, and other.

Includes chronic hypertension, cardiac or renal disease, pulmonary pathology, diabetes, malaria, sickle cell disease, severe anemia, urinary tract infection, severe condylomatous disease, HIV or a condition associated with HIV infection, and thalassemia.

Includes hypertension in pregnancy, pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, and suspected fetal growth impairment.

Includes forceps and vacuum vaginal delivery.

The facility-level variables associated with increased likelihood of cesarean included 24/7 availability of anesthesia (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1–1.9), being a teaching facility (aOR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.2–1.9), levying fees for cesarean delivery (aOR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1–1.9), and having electronic fetal monitoring capability (aOR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.2–2.2) (all P<0.01). The factor most strongly associated with increased odds of cesarean delivery was the availability of providers who were skilled in operative vaginal delivery (aOR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.5–3.0; P<0.001).

4. DISCUSSION

The present analysis of more than 80 000 nulliparous women in spontaneous labor with a single, cephalic term pregnancy (Robson group 1) delivering in healthcare facilities in 24 countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America identified several factors independently associated with cesarean delivery. Of these, the factors that are potentially actionable and modifiable include BMI, management of medical complications, timing of referral in labor, gestational age at delivery, and levying fees for cesarean delivery.

Obese women are more likely to undergo cesarean delivery [10–11]. In the present cohort, the odds of intrapartum cesarean were increased for overweight and obese women, and reduced for underweight women, as compared with normal weight women. The prevalence of obesity among pregnant women is increasing globally, even in low- and middle-income countries [12]. Strategies to reduce obesity among women intending to become pregnant, and interventions to maintain an appropriate gestational weight gain during pregnancy are likely to reduce the use of cesarean, and should be essential components of the research agenda worldwide [13].

Unsurprisingly, women with medical problems were found to have a higher risk of cesarean delivery in the present study. Optimizing management or preventing these medical issues may allow some women to benefit from achieving a vaginal delivery. Disorders such as chronic hypertension or severe anemia, which may have implications for fetal growth and subsequent resilience in labor (that otherwise might lead to cesarean birth for fetal or maternal indications), can be properly managed with medical treatments such as anti-hypertensive drugs and iron supplementation, or prevented altogether with proper screening and intervention [14–15].

The analysis found no association between availability of a partogram at the facility and cesarean, but did show that women who were referred during the course of labor had a higher odds of cesarean delivery. Use of the partogram has shown mixed effects in its ability to impact mode of delivery, suggesting that it may not be the ideal intervention to try and reduce cesarean delivery among women in Robson group 1 who are referred during labor [16]. The WHO has asserted that assessment of cervical dilation over time is a poor predictor of severe adverse delivery outcomes, and that the validity of the alert line in the partogram, which is based on the “one-centimeter-per-hour” rule, should be evaluated [17]. Provided that maternal and fetal conditions are reassuring, medical interventions to accelerate labor and delivery (augmentation or cesarean) before 5 cm are not recommended [18]. A study in rural India found that the medical conditions associated with referral during labor and delivery were often known before the onset of labor [19]. Although the study was not specifically looking at delivery mode, it concluded that to improve pregnancy outcomes women with conditions that put them at high risk for referral should deliver at higher level facilities, while women with complications in labor and delivery need prompt detection and transfer [19]. This suggests that, to reduce the rate of cesarean among low-risk women, earlier or improved adherence to referral guidelines might be useful.

The analysis also suggested that pregnant women at a gestational age of 39 weeks or more are more likely to deliver by cesarean, with the odds increasing by almost a factor of 2 for women at 41 weeks or later. This is a common finding and was recently tested in a prospective, randomized controlled trial of nulliparous women with a term, cephalic, singleton fetus [20]. Women in the trial were randomized to induction versus expectant management, which differs from the present population who went into labor spontaneously; nevertheless, the trial showed a significant reduction in the frequency of cesarean delivery in the induction group as compared with the expectant management group [20]. Not all healthcare settings may be able to handle the volume of systematic induction of labor of nulliparous women at 41 weeks, induction of labor may result in other complications such as increased use of instrumental delivery, and we are not recommending systematic induction for women at 41 weeks; nevertheless, studies suggest that gestational age may be a modifiable risk factor for use of cesarean delivery among some women [21].

In settings where maternity care is not provided free of charge, economic incentives for performing cesarean, as opposed to vaginal delivery, may be associated with the decision for mode of delivery [22]. A study of over four million women found that those who delivered at private hospitals had a 1.4 higher adjusted odds of delivery by cesarean, regardless of individual risk and contextual factors such as country, year, or study design [22]. The present study found that women had an increased risk of cesarean delivery in facilities where fees are required for the procedure. Economic incentives have been identified as factors driving up the cesarean rate, but remain controversial in terms of their effectiveness and potential interactions with other factors [23]. The WHO guideline on non-clinical interventions to reduce unnecessary cesarean notes that “financial strategies (i.e., insurance reforms equalizing physician fees for vaginal births and caesarean sections) for healthcare professionals or healthcare organizations are recommended only in the context of rigorous research” [24].

Lastly, the availability of electronic fetal monitoring (actual use for each woman was not recorded in the dataset) in facilities was found to be associated with an increased likelihood of cesarean among women in Robson group 1. Increased use of this technology has been previously associated with increased rates of cesarean delivery [25]. As an alternative, WHO has recommended that intermittent auscultation of the fetal heart rate with either a Doppler ultrasound device or a Pinard fetal stethoscope should be used to monitor healthy pregnant women in labor [24].

The study has some limitations. The data were collected 10 years ago, multiple comparisons were performed with the data, and unmeasured facility, sociodemographic, and obstetric variables may have confounded the results. In terms of the BMI data, it was not always clear at what stage in the pregnancy the weight measurement was made, representing a significant limitation of that variable that should be taken into consideration. Other potentially important variables (e.g., weight gain during pregnancy, length of labor, and use of fetal monitoring for each woman) were not available in the database and could not be included in the adjusted analyses. The large sample size, the availability of multiple covariates, the specific study design to assess delivery mode, and the fact that data from several countries were collected by a standard approach and measurement tool are strengths of the analysis.

Robson group 1 women have been identified as an important population for studying how vaginal delivery can be increased and cesarean delivery reduced. On the basis of the present analysis, we suggest an increased focus on maintaining a healthy pre-pregnancy and pregnancy weight, tighter management of women with medical problems, and more specific referral standards that transfer at-risk women earlier in the course of labor, if appropriate. Interventions or policies that remove financial incentives to perform a cesarean procedure might possibly reduce this practice, although more research is needed for validation.

Synopsis:

Certain risk factors are associated with cesarean delivery among low-risk women. Modifiable factors might be targeted to reduce unnecessary cesarean in this population.

Acknowledgments

The WHOGS was financially supported by the UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction; the WHO; the Governments of China, India, and Japan; and the United States Agency for International Development. The manuscript represents the views of the named authors only, and does not represent the views of the WHO. The present secondary analysis of the survey data was supported by the National Institutes of Health through the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development Women’s Reproductive Health Research K12 award (5K12HD001271–18) and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation.

The authors thank all of the women and men involved in collecting the data and all of the women who participated in the study—their health, wellbeing, and successful pregnancy outcomes are the motivation for the research.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Betran AP, Ye J, Moller AB, Zhang J, Gulmezoglu AM, Torloni MR. The increasing trend in cesarean section rates: global, regional and national estimates: 1990 – 2014. PlosOne 2016. http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0148343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Betran AP, Torloni MR, Zhang JJ, Gülmezoglu AM. WHO Working Group on Caesarean Section. WHO Statement on Caesarean Section Rates: a commentary. BJOG. 2016;123(5):667–70.WHO Robson classification implementation manual. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogel JP, Betran AP, Vindevoghel N, Souza JP, Torloni MR, Zhang J et al. Use of the Robson classification to assess cesarean section trends in 21 countries: a secondary analysis of two WHO multicountry surveys. Lancet Glob Health 2015, 3:e260–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ACOG SMFM Safe Prevention of Primary Cesarean Delivery. Obsetric care consensus No. 1, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Boatin AA, Cullinane F, Torloni MR, Betran AP. Audit and feedback using the Robson classification to reduce cesarean section rates: a systematic review. BJOG 2018, 125 (1): 36–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Betran AP, Vindevoghel, Souza JP, Torloni MR A systematic review of the Robson classification for cesarean section: what works, doesn’t work and how to improve it. PLoS One 2014, 9(6): e97769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah A, Faundes A, Machoki M, Bataglia V, Amokrane F, Donner A et al. Methodological considerations in implementing the WHO global survey for monitoring maternal and perinatal health. Bulletin of the WHO 2008, 86: 126–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Souza J, Gülmezoglu A, Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M, Carroli G, Fawole B et al. Caesarean section without medical indications is associated with an increased risk of adverse short-term maternal outcomes: the 2004–2008 WHO Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health. BMC Medicine. 2010;8(1):71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.United Nations Human Development Index, 2008. Accessed 11.15.18 (http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/reports/268/hdr_20072008_en_complete.pdf)

- 10.Weiss JL, Malone FD, Emig D, et al. Obesity, obstetric complications and cesarean delivery rate— a population-based screening study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004; 190(4):1091–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dietz P, Callaghan W, Morrow B, Cogswell M. Population-based assessment of the risk of primary cesarean delivery due to excess prepregnancy weight among nulliparous women delivering term infants. Matern Child Health J. 2005; 9(3):237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.International Weight Management in Pregnancy (i-WIP) Collaborative Group. Effect of diet and physical activity based interventions in pregnancy on gestational weight gain and pregnancy outcomes: meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. BMJ. 2017 Jul 19;358:j3119. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3119. Review. Erratum in: BMJ. 2017 Aug 23;358:j3991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ACOG Practice Bulletin. Hypertension in Pregnancy. ACOG 2013.

- 15.ACOG Practice Bulletin. Anemia in Pregnancy. ACOG 2008.

- 16.Lavender T, Cuthbert A, Smyth RMD. Effect of partograph use on outcomes for women in spontaneous labour at term and their babies.Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018, Issue 8 Art. No.: CD005461. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005461.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Souza JP, Oladapo OT, Fawole B, Mugerwa K, Reis R, Barbosa-Junior F et al. Cervical dilatation over time is a poor predictor of severe adverse birth outcomes: a diagnostic accuracy study. BJOG. 2018 Jul;125(8):991–1000. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15205. Epub 2018 Apr 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oladapo OT, Diaz V, Bonet M, Abalos E, Thwin SS, Souza H et al. Cervical dilatation patterns of ‘low-risk’ women with spontaneous labour and normal perinatal outcomes: a systematic review. BJOG. 2018 Jul;125(8):944–954. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14930. Epub 2017 Nov 3. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel AB, Prakash AA, Raynes-Greenow C, Pusdekar YV, Hibberd PL. Description of inter-institutional referrals after admission for labor and delivery: a prospective population based cohort study in rural Maharashtra, India. BMC Health Services Research (2017) 17:360 DOI 10.1186/s12913-017-2302-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, Tita ATN, Silver RM, Mallett G et al. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. NEJM 2018, 379: 513–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Middleton P, Shepherd E, Crowther CA. Induction of labour for improving birth outcomes for women at or beyond term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 5: CD004945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoxha I, Syrogiannouli L, Luta X, Tal K, Goodman DC, da Costa BR, Jüni P. Caesarean sections and for-profit status of hospitals: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013670. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Betrán AP, Temmerman M, Kingdon C, Mohiddin A, Opiyo N, Torloni MR et al. Interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections in healthy women and babies. Lancet. 2018. October 13;392(10155):1358–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO Recommendations: Non-Clinical Interventions to Reduce Unnecessary Cesarean Sections. Accessed 11.30.18 (http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/275377/9789241550338-eng.pdf?ua=1)

- 25.Grimes DA, Peipert JF. Electronic fetal monitoring as a public health screening program: the arithmetic of failure. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:1397–1400) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]