Abstract

Background:

Trans people face uncertain risk for breast cancer and barriers to accessing breast screening. Our objectives were to identify and synthesize primary research evidence on the effect of cross-sex hormones (CSHs) on breast cancer risk, prognosis and mortality among trans people, the benefits and harms of breast screening in this population, and existing clinical practice recommendations on breast screening for trans people.

Methods:

We conducted 2 systematic reviews of primary research, 1 on the effect of CSHs on breast cancer risk, prognosis and mortality, and the other on the benefits and harms of breast screening, and a third systematic review of guidelines on existing screening recommendations for trans people. We searched PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and grey literature sources for primary research, guidelines and position statements published in English between 1997 and 2017. Citations were screened by 2 independent reviewers. One reviewer extracted data and assessed methodological quality of included articles; a second reviewer verified these in full. The results were synthesized narratively.

Results:

Four observational studies, 6 guidelines and 5 position statements were included. Observational evidence of very low certainty did not show an effect of CSHs on breast cancer risk in trans men or trans women. Among trans women, painfulness of mammography and ultrasonography was low. There was no evidence on the effect of CSHs on breast cancer prognosis and mortality, or on benefits and other harms of screening. Existing clinical practice documents recommended screening for distinct trans subpopulations; however, recommendations varied.

Interpretation:

The limited evidence does not show an effect of CSHs on breast cancer risk. Although there is insufficient evidence to determine the potential benefits and harms of breast screening, existing clinical practice documents generally recommend screening for trans people; further large-scale prospective comparative research is needed.

“Trans” is an umbrella term for people with diverse gender identities and expressions that differ from stereotypical gender norms.1,2 Recent estimates suggest that there were approximately 200 000 trans people in Canada in 2016.3 Many trans people seek gender-affirming medical procedures or cross-sex hormone (CSH) therapy, or both, to align their physical appearance with their sense of self.4 Cross-sex hormone therapy refers to the use of exogenous sex hormones that are opposite to those of a person’s natal sex.5 Breast cancer risk in trans people is hypothesized to be influenced by CSHs.6 However, it is unclear whether the potential alteration in risk for breast cancer by CSH therapy should affect eligibility for breast screening. Trans people are medically underserved and face unique challenges in accessing appropriate care.3,7 With respect to breast health, 25%–30% of trans people in Ontario with a perceived need for mammography were unable to access it.8 In addition, trans people are less likely to pursue breast screening than are cisgender women (i.e., people assigned female sex at birth and who identify as female).9 Although this shows a disparity in the approach to breast cancer detection when compared to the nontrans population, information on the potential benefits and harms of screening in the trans population is limited.10

Organized breast screening programs aim to reduce breast cancer mortality through regular screening. At this time, breast screening programs may not have official screening policies for trans people, which may result in inconsistent inclusion of trans people within organized programs. The development of programmatic evidence-based policies should begin with the systematic identification of evidence and then the use of this information to formulate and implement policy.11 In this article, we present the findings of 3 systematic reviews that can be used by organized breast screening programs to initiate a process of breast screening policy development for the trans population. Our objectives were to identify and synthesize 1) primary research on the effect of CSHs on breast cancer risk, prognosis and mortality among trans people (review 1), 2) primary research on the benefits and harms of breast screening among trans people (review 2) and 3) existing clinical practice recommendations on breast screening for trans people (review 3).

Methods

We developed separate protocols to guide the reviews (Appendix 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/3/E598/suppl/DC1); they were not publicly registered. We consulted the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions12 when developing these reviews and followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guideline13 to report this review. The term “trans men” is used for people who were assigned female sex at birth but whose gender identity is male or on the male spectrum.14 The term “trans women” is used for people who were assigned male sex at birth but whose gender identity is female or on the female spectrum.14 These terms are used for simplicity and are meant to be inclusive of all those on the female-to-male and male-to-female spectra, respectively.

Search strategy

For reviews 1 and 2, we searched PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews for primary research published in English between January 1997 and May 2017. For review 3, we searched PubMed, MEDLINE and guidelines databases for guidelines and positions statements published in English between January 1997 and February 2017. We developed all search strategies in consultation with a medical librarian (Appendix 2, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/3/E598/suppl/DC1). We also conducted grey literature searches and hand searches of on-topic journals. Reference lists of relevant primary studies, systematic reviews, literature reviews and guidelines were reviewed, and citation recommendations from experts were sought (O.M., L.P., M.F-K., M.C.-F.).

Study selection

For all reviews, 2 reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts using predefined selection criteria (review 1: L.P., M.C.-F.; review 2: O.M., M.Y.; review 3: M.F.-K., M.Y.) (Table 1). For assessment of the performance (i.e., sensitivity and specificity) of breast screening technologies, a population, intervention, reference standard and diagnosis (PIRD) framework was applied. Population and intervention components are defined in Table 1. The reference standard for a positive screening result was defined as pathology results available from biopsy, whereas patients with negative screening results must have been followed for at least 1 year. The diagnosis of interest was breast cancer. Any citation marked for inclusion by either reviewer went to full-text screening. Dual independent full-text screening was conducted, with consensus required for inclusion or exclusion of each citation. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Table 1:

Inclusion criteria for the 3 systematic reviews

| Study component | Review 1 | Review 2 | Review 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Populations | Trans men (≥ 18 yr) with:

|

Asymptomatic trans men (≥ 18 yr) with:

|

Trans men (≥ 18 yr) with:

|

| Interventions |

|

Breast screening with:

|

Breast screening with:

|

| Comparators |

|

|

NA |

| Outcomes |

|

|

Breast screening recommendations for trans people with a focus on:

|

| Designs/ document types |

|

|

|

| Other |

|

|

|

Note: CSH = cross-sex hormone, NA = not applicable.

Observational studies without comparison groups were included only if they reported on cancer detection rate, interval cancer rate, sensitivity, specificity or any harm outcomes.

Data management

We used DistillerSR15 (Evidence Partners) to manage all phases of reviews 1 and 2. For review 3, we used DistillerSR for screening and data extraction for citations obtained from electronic databases, whereas these tasks were completed in Microsoft Excel for citations from the grey literature search. We developed screening, data extraction and quality-assessment forms a priori and piloted them to ensure validity and interrater reliability.

Data extraction and quality assessment

For all reviews, 1 reviewer extracted data from included citations (review 1: L.P.; review 2: O.M.; review 3: M.F.-K.). A second reviewer verified all extracted data (review 1: M.C.-F.; reviews 2 and 3: M.Y.); disagreements were resolved through discussion. Data extraction items for each review are provided in the respective protocol (Appendix 1). Authors were not contacted for missing data.

For reviews 1 and 2, the quality of cohort studies was assessed with the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale.16 The quality of cross-sectional studies was assessed by considering key methodological components such as the selection of participants, and exposure and outcome assessments. One reviewer conducted the quality assessments (review 1: L.P.; review 2: O.M.). A second reviewer verified all ratings (review 1: M.C.-F.; review 2: M.Y.); disagreements were resolved through discussion.

For review 3, quality assessment of each guideline was conducted independently by 2 reviewers (M.Y., M.F.-K.) using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II instrument.17 The quality of position statements was not assessed.

Synthesis

For reviews 1 and 2, we examined similarities and differences in study characteristics, quality, sample and intervention features across the included studies. Results for outcomes of interest for each objective are presented narratively for trans men and trans women separately. Meta-analysis was not possible in either review owing to a lack of available count data in the comparison groups (review 1) or an insufficient number of included studies (review 2). The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach was used to assess the certainty of the available evidence for each outcome.18,19 One reviewer conducted GRADE assessments (review 1: L.P.; review 2: O.M.), which were verified by a second reviewer (review 1: M.C.-F.; review 2: M.Y.).

For review 3, similarities and differences across breast screening recommendations were examined for trans men and trans women separately.

Ethics approval

Because human subjects were not involved in this study as it was a systematic review, ethics approval was not sought.

Results

Search results

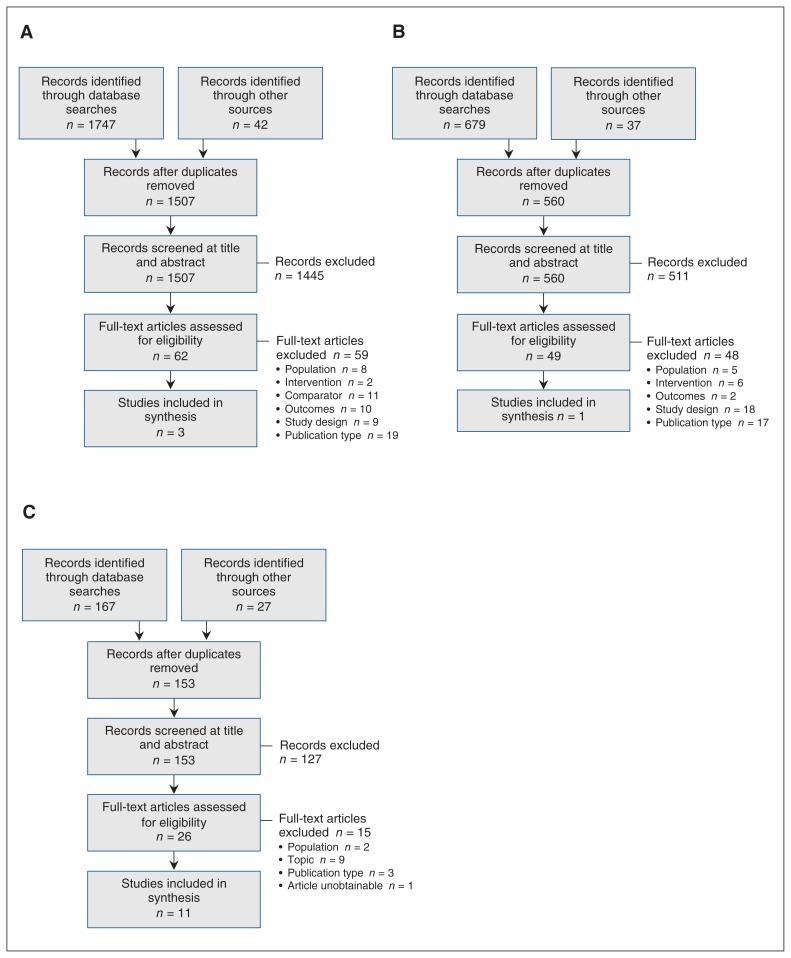

For review 1, 1507 unique citations were identified. After screening, 3 studies met the inclusion criteria20–22 (Figure 1, A). For review 2, 560 unique citations were identified, among which 1 study met the inclusion criteria23 (Figure 1, B). The search for review 3 identified 153 unique citations, and, after screening, 11 documents were included (Figure 1, C).4,5,24–32 Citations excluded at full-text screening are listed in Appendix 3 (available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/3/E598/suppl/DC1).

Figure 1:

Flow diagrams showing study selection for the systematic review of primary research evidence examining the effect of cross-sex hormones on breast cancer risk, prognosis and mortality in trans people (review 1) (A), the systematic review of primary research evidence examining the benefits and harms of breast cancer screening in trans people (review 2) (B) and the systematic review of guidelines and position statements on existing breast cancer screening recommendations for trans people (review 3) (C).

Characteristics of included studies and documents

For review 1, 3 retrospective cohort studies examining the effect of CSHs on breast cancer risk among trans people were identified20–22 (Table 2). All 3 included trans men, and 2 included trans women.20,21 Across studies, 1069 trans men and 3419 trans women were exposed to CSHs (Table 3, Supplementary Table S1, Appendix 4, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/3/E598/suppl/DC1). The duration of CSH exposure varied within and across studies. In 1 study, the comparison group was 130 trans men who did not receive CSHs,22 and in 2 studies, comparisons were drawn against general population samples.20,21 The length of follow-up ranged from 9 to 38 years. Funding details were reported for 2 studies;20,21 neither received commercial support. Two studies were rated as having fair methodological quality,20,21 and 1 was rated as poor22 (Table 2).

Table 2:

Characteristics of included primary studies (reviews 1 and 2)

| Investigator (review) | Study design | Eligibility criteria | Country | Study period | Total sample size | Source of funding | Study quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown et al., 201520 (review 1) | Retrospective cohort |

|

United States | 17 yr (Oct. 1, 1996, to Sept. 30, 2013) | 5135 | Authors employed by VHA No grant or commercial funding |

Fair* |

| Gooren et al., 201321 (review 1) | Retrospective cohort |

|

The Netherlands | 38 yr (1975 to Dec. 31, 2012) | 3102 | Two authors received noncommercial support | Fair* |

| Weyers et al., 201023 (review 2) | Cross-sectional |

|

Belgium | 4 mo (Mar–June 2007) | 50 | First author received commercial support | Poor† |

| Kuroda et al., 200822 (review 1) | Retrospective cohort |

|

Japan | 9 yr (1998–2006) | 186 | NR | Poor* |

Note: NR = not reported, VHA = Veterans Health Administration.

Assessed with the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale.16,33 Detailed results of the quality assessment are provided in Supplementary Table S2, Appendix 4 (available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/3/E598/suppl/DC1).

No formal critical appraisal tool was used; methodological quality was assessed by considering key methodological components such as the selection of participants, and exposure and outcome assessments.

Detailed results of the quality assessment are provided in Supplementary Table S3, Appendix 4.

Table 3:

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) summary of findings table for the effect of exposure to cross-sex hormones on breast cancer risk, prognosis and mortality in trans people (review 1)

|

Population: trans people aged 16–83 yr Intervention: cross-sex hormone therapy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome; population | Effect | No. of exposed participants (no. of studies) | Certainty of evidence (GRADE) |

| Trans men exposed to testosterone | |||

| Breast cancer risk* | Differences in incidence rate or cumulative incidence between exposed cohorts and nonexposed cohorts or general population samples were not statistically significant or were not reported† | 1069 (3)20–22 | ⊕○○○ Very low‡§ |

| Stage at diagnosis | No primary research evidence identified | ||

| Survival | |||

| Breast cancer mortality | |||

| Trans women exposed to estrogen only, androgen deprivation or antiandrogens only, or estrogen with androgen deprivation or antiandrogens | |||

| Breast cancer risk* | Differences in incidence rate or cumulative incidence between exposed cohorts and general population samples were not statistically significant or were not reported† | 3419 (2)20,21 | ⊕○○○ Very low‡§ |

| Stage at diagnosis | No primary research evidence identified | ||

| Survival | |||

| Breast cancer mortality | |||

Assessed with the use of administrative database or medical records, with follow-up not reported or at a minimum of 6 years after cross-sex hormone therapy started.

We did not calculate a single pooled effect estimate. Additional information and detailed results for each study are provided in

Supplementary Table S4, Appendix 4.

Very low certainty rating = we have very little confidence in the effect estimate, and the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the effect estimate.

The evidence was downgraded owing to the observational nature of the study designs and serious concerns regarding risk of bias, indirectness and imprecision.

Detailed Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation assessments are provided in Supplementary Table S5, Appendix 4.

For review 2, 1 cross-sectional study reporting on 1 screening-related harm was identified23 (Table 2). The sample consisted of 50 trans women, all of whom underwent sex-reassignment surgery (Supplementary Table S1, Appendix 4). Forty-eight participants (96%) received augmentative breast surgery, 47 (94%) were receiving estrogen replacement therapy, and 2 (4%) were receiving an androgen-deprivation agent. All participants received mammography and sonography performed by a single experienced radiologist. There was no comparison group. Funding details were not reported; however, the first author declared commercial supports. This study was considered of poor methodological quality.

For review 3, 11 documents (6 guidelines and 5 position statements), provided recommendations on breast screening for trans people4,5,24–32 (Table 4). Documents were developed by groups in Canada,4,5,24,25,28 the United States26,29,31,32 and the United Kingdom.27,30 The quality of the included guidelines was low. Across guidelines, the highest-scoring Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II domains were scope and purpose, and clarity of presentation. The lowest-scoring domains were applicability and editorial independence.

Table 4:

Characteristics and quality of included guidelines and position statements (review 3)

| Organization, year | Document type | Country | Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II domain scores, %* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scope and purpose | Stakeholder involvement | Rigor of development | Clarity of presentation | Applicability | Editorial independence | |||

| Canadian Cancer Society, 201724 | Position statement | Canada | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Canadian Cancer Society, 201725 | Position statement | Canada | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Centre of Excellence for Transgender Health, 201626 | Guideline | United States | 81 | 56 | 29 | 81 | 27 | 0 |

| International Planned Parenthood Federation, 201527 | Position statement | United Kingdom | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Sherbourne Health Centre, 201528 | Guideline | Canada | 64 | 44 | 16 | 25 | 6 | 0 |

| Transgender Health Information Program, 20155 | Guideline | Canada | 67 | 67 | 6 | 14 | 13 | 0 |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 201329 | Position statement | United States | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| National Health Service, 201330 | Guideline | United Kingdom | 64 | 25 | 0 | 28 | 17 | 0 |

| American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 201131 | Position statement | United States | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Endocrine Society, 200932 | Guideline | United States | 72 | 33 | 63 | 58 | 8 | 46 |

| Vancouver Coastal Health, Transcend Transgender Support & Education Society and Canadian Rainbow Health Coalition, 20064 | Guideline | Canada | 86 | 61 | 17 | 89 | 0 | 0 |

Note: NA = not assessed.

We did not assess the quality of position statements as they are unlikely to undergo the same development process as guidelines.

Trans men

Effect of cross-sex hormones on breast cancer risk, prognosis and mortality (review 1)

Three studies examined breast cancer risk among trans men exposed to CSHs.20–22 The risk was not statistically different than that for trans men not exposed to CSHs (0.0% v. 0.8%, p < 0.05)22 or the expected risk based on estimates for the general population of women (standardized incidence ratio 0.3, 95% confidence interval 0.0–3.7).20 In the third study,21 the risk (5.9 cases per 100 000 person-years) was lower than that expected for the general population of women (154.7 cases per 100 000 person-years), but the statistical significance of this finding was not reported. This evidence received a very low GRADE rating owing to the observational study designs and serious concerns regarding risk of bias, indirectness and imprecision (Table 3).

Evidence on the effect of CSHs on breast cancer prognosis or mortality among trans men was not identified.

Benefits and harms of breast screening (review 2)

Evidence on the benefits and harms of breast screening among trans men was not identified.

Recommendations on breast screening (review 3)

Seven documents provided breast screening recommendations for trans men4,24,26–28,30,31 (Table 5). Breast screening was recommended for trans men without chest reconstruction.4,24,26,28,31 Screening eligibility in this group also depended on age24,28,31 and eligibility requirements for cisgender women.4,26,28 Two documents recommended mammography every 2 years,24,28 1 recommended mammography without specifying the screening interval,4 1 recommended annual clinical breast examination,28 and 1 recommended annual breast examinations without specifying whether these were clinical examinations or self-examinations.4

Table 5:

Existing breast screening recommendations for trans men (review 3)

| Organization, year; population | Document type | Screening recommendations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additional eligibility criteria | Modality | Interval | Additional recommendations | ||

| Without chest reconstruction* | |||||

| CCS, 201724 | Position statement | 40–49 yr, at average risk | NR | NR | Discuss individual risk of breast cancer and benefits and risks of mammography |

| 50–69 yr, at average risk | Mammography | Every 2 yr | NR | ||

| ≥ 70 yr, at average risk | NR | NR | Discuss whether and how client should be screened according to individual risk factors | ||

| CETH, 201626 | Guideline | NR | NR | NR | Follow guidelines for cisgender women |

| SHC, 201528 | Guideline | NR | Clinical breast examination | Annual | Follow guidelines for cisgender women |

| 50–71 yr | Mammography | Every 2 yr | |||

| ACOG, 201131 | Position statement | NR | NR | NR | Age-appropriate† screening |

| VCH, TTSES & CRHC, 20064 | Guideline | With or without history of CSH use,‡§ with or without oophorectomy | Breast examination¶ | Annual | NR |

| Mammography | NR | Follow guidelines for natal females | |||

| With partial chest reconstruction* | |||||

| CCS, 201724 | Position statement | NR | Ultrasonography or MRI** | NR | Discuss individual risk factors†† for breast cancer |

| CETH, 201626 | Guideline | NR | Ultrasonography or MRI | NR | NR |

| SHC, 201528 | Guideline | NR | Mammography | NR | Not required following chest reconstruction |

| VCH, TTSES & CRHC, 20064 | Guideline | With or without history of CSH use,ठwith or without oophorectomy | Mammography | NR | Not necessary following chest reconstruction, but should be considered if only a reduction is performed |

| Trans men in general (i.e., chest reconstruction status not specified) | |||||

| CCS, 201724 | Position statement | High risk‡‡ | NR | NR | May need to be screened at earlier age or more frequently than trans men at average risk, or both |

| IPPF, 201527 | Position statement | With history of CSH useठ| NR | Periodic | Periodic cancer screening for those who retain their breast tissue |

| SHC, 201528 | Guideline | Strong family history of breast cancer | Mammography | NR | Follow the same guidelines as for cisgender women regarding indications for referral to high-risk screening program/ genetic assessment |

| NHS, 201330 | Guideline | With developed breast tissue | NR | NR | Breast screening |

Note: ACOG = American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, CBE = clinical breast examination, CCS = Canadian Cancer Society, CETH = Center of Excellence for Transgender Health, CRHC = Canadian Rainbow Health Coalition, CSH = cross-sex hormone, IPPF = International Planned Parenthood Federation, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, NHS = National Health Service, NR = not reported, SHC = Sherbourne Health Centre, TTSES = Transcend Transgender Support & Education Society, VCH = Vancouver Coastal Health.

Chest reconstruction was variably termed as mastectomy, gender-affirming chest surgery or chest surgery.

Age range not specified.

Cross-sex hormone use was variably termed as hormone use or testosterone.

Duration not specified.

Document did not specify whether clinical breast examinations, breast self-examinations or both were recommended.

Specific breast screening recommendations for trans men who have had partial chest reconstruction were not provided. However, it was noted that, in some cases, mammography may not be possible following chest reconstruction surgery, and breast ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging may be a preferable screening method.

Risk factors include the amount of breast tissue removed, personal risk factors and history, whether the client has had oophorectomy, and whether the client is taking testosterone and other hormones.

Defined as a genetic mutation in oneself, or having a parent, sibling or child who has a genetic mutation that puts them at higher risk for breast cancer; a family history that indicates a lifetime risk of breast cancer of 25% or greater, confirmed through genetic assessment; or having received radiation therapy to the chest before 30 years of age as treatment for another cancer or condition.

Screening was also recommended for trans men who have had partial chest reconstruction.4,24,26,28 Recommended modalities varied and included ultrasonography,24,26 magnetic resonance imaging24,26 and mammography.4 One document stated that mammography was not required following chest reconstruction.28 None of the documents provided a specific recommendation on the screening interval.

For trans men in general (i.e., chest reconstruction status not specified), screening recommendations varied.24,27,28,30 Eligibility depended on having a history of male CSH use,27 having developed breast tissue,30 having a family history of breast cancer24,28 and the presence of other risk factors.24 One document recommended that those with a strong family history of breast cancer follow guidelines for cisgender women regarding referral to a high-risk mammography screening program.28 The other 3 documents did not provide specific recommendations on modalities or intervals.24,27,30

Trans women

Effect of cross-sex hormones on breast cancer risk, prognosis and mortality (review 1)

Two studies examined breast cancer risk among trans women exposed to CSHs.20,21 In 1 study, the risk among trans women exposed to CSHs was not statistically different from that expected for the general population of men (standardized incidence ratio 0.0, 95% confidence interval 0.0–3.7).20 In the second study, breast cancer risk among trans women exposed to CSHs was slightly higher (4.1 cases per 100 000 person-years) than estimates for the general population of men (1.2 cases per 100 000 person-years), but the statistical significance of this finding was not reported.21 This body of evidence received a very low GRADE rating owing to the observational study designs and serious concerns regarding risk of bias, indirectness and imprecision (Table 3).

Evidence on the effect of CSHs on breast cancer prognosis or mortality among trans women was not identified.

Benefits and harms of breast screening (review 2)

Evidence on 1 screening-related harm among trans women was identified.23 One cross-sectional study reported on pain experienced by 50 trans women during mammography and ultrasonography.23 The painfulness of both procedures, as assessed with an 11-point visual analogue scale, was rated as low (mean score range for mammography 1.7 [standard deviation 2.1] to 2.0 [standard deviation 2.3], mean score for ultrasonography 0.5 [standard deviation 1.2]) (Table 6). These 2 bodies of evidence received very low GRADE ratings owing to serious concerns regarding the observational study design and risk of bias (Table 6).

Table 6:

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) summary of findings table for benefits and harms of breast screening for trans people (review 2)

|

Population: asymptomatic adult trans people with mean age of 43.1 (SD 10.4) yr Intervention: breast screening with mammography, MRI, ultrasonography, clinical breast examination or breast self-examination | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome; population | Effect | No. of participants (no. of studies) | Certainty of evidence (GRADE) |

| Trans men | |||

| Benefits* | No primary research evidence identified | ||

| Harms† | |||

| Trans women | |||

| Benefits* | No primary research evidence identified | ||

| Overdiagnosis, false-positive screen and patient-reported anxiety | |||

| Painfulness of mammography‡§ | Mean scores ranged from 1.7 (SD 2.1) to 2.0 (SD 2.3)¶ | 50 (1)23 | ⊕○○○ Very low**†† |

| Painfulness of ultrasonography‡§ | Mean score 0.5 (SD 1.2)‡‡ | 50 (1)23 | ⊕○○○ Very low**†† |

Note: MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, SD = standard deviation.

Breast-cancer–specific mortality, all-cause mortality, cancer detection rate, interval cancer rate, sensitivity and specificity.

Overdiagnosis, false-positive screen, patient-reported anxiety and patient-reported pain.

Assessed by participant using a visual analogue scale ranging from 0 to 10.

Performed by a single experienced radiologist.

Two postmammography assessments of participant-experienced pain were conducted, 1 by a radiologist and the other by a study nurse.

The corresponding mean scores were 1.7 and 2.0.

Very low certainty rating = we have very little confidence in the effect estimate, and the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the effect estimate.

The evidence was downgraded owing to serious concerns regarding the observational nature of the study design and risk of bias.

Detailed Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation assessments are provided in Supplementary Table S6, Appendix 4.

The study personnel responsible for administering the assessment of experienced pain were not reported.

Evidence on other screening-related harms, and on the benefits of screening among trans women was not identified.

Recommendations on breast screening (review 3)

Ten documents provided breast screening recommendations for trans women4,5,25–32 (Table 7). For those with a history of CSH use, screening eligibility depended on the duration of CSH use,25,26,28 age,4,25,26,28 presence of breast implants,25 breast growth,4 orchiectomy status,4 other risk factors4,28 and guidelines for cisgender women.29 Recommended modalities and intervals included mammography every 2 years25,26,28 and mammography without a specified interval.4 One document recommended against periodic breast self-examination and annual clinical breast examination.4 Screening was not recommended for trans women with less than 5 years of CSH use25 and those without a history of CSH use.4

Table 7:

Existing breast screening recommendations for trans women (review 3)

| Organization, year; population | Document type | Screening recommendations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additional eligibility criteria | Modality | Interval | Additional recommendations | ||

| History of CSH use* | |||||

| CCS, 201725 | Position statement | 40–49 yr, at average risk, CSH use > 5 yr | NR | NR | Discuss individual risks of breast cancer and benefits and risks of mammography |

| 50–69 yr, at average risk, CSH use > 5 yr, without breast implants | Mammography† | Every 2 yr | NR | ||

| 50–69 yr, at average risk, CSH use > 5 yr, with breast implants | Diagnostic mammography† | Every 2 yr | NR | ||

| ≥ 70 yr, at average risk, CSH use > 5 yr | NR | NR | Discuss how often client should be screened for breast cancer | ||

| CSH use < 5 yr | NA | NA | Breast screening not recommended | ||

| CETH, 201626 | Guideline | ≥ 50 yr,‡ CSH use 5–10 yr | Mammography | Every 2 yr | Clinicians may choose to reduce age at onset of screening, number of years of female hormone exposure or frequency of screening in clients with significant family risk factors |

| Any age, CSH use > 5 yr | |||||

| IPPF, 201527 | Position statement | Current CSH use§ | NR | Periodic | NR |

| SHC, 201528 | Guideline | 50–71 yr, CSH use > 5 yr | Mammography | Every 2 yr | NR |

| < 50 yr, additional risk factors¶ | Mammography | NR | Owing to lack of consensus on screening for younger trans women, emphasis may be placed on client preference following counselling on risks and benefits of screening | ||

| CDC, 201329 | Position statement | Past or current CSH use,§ meet all NBCCEDP eligibility requirements** | NR | NR | Providers should discuss benefits and harms of screening and individual risk factors to determine whether screening is medically indicated |

| VCH, TTSES, & CRHC, 20064 | Guideline | > 50 yr,‡ additional risk factors,¶ past (but not current) CSH use, breast growth, no orchiectomy | Mammography | NR | NR |

| > 50 yr,‡ additional risk factors,¶ current CSH use,†† no orchiectomy | Mammography | NR | NR | ||

| > 50 yr,‡ additional risk factors,¶ past or current CSH use, postorchiectomy | Mammography | NR | NR | ||

| NR | Clinical breast examination | Annual | Not recommended | ||

| NR | Breast self-examination | Periodic | Not recommended | ||

| No history of CSH use* | |||||

| VCH, TTSES, & CRHC, 20064 | Guideline | No orchiectomy | NA | NA | Routine screening not recommended |

| Trans women in general (i.e., female CSH use not specified) | |||||

| SHC, 201528 | Guideline | 30–69 yr, family history suggestive of hereditary breast cancer | MRI | Annual | Consider obtaining expert opinion regarding need for annual MRI |

| Breast implants | Diagnostic mammography | NR | NR | ||

| THIP, 20155 | Guideline | Developed breast tissue | NR | NR | Screening |

| NHS, 201330 | Guideline | Developed breast tissue | NR | NR | Screening |

| ACOG, 201131 | Position statement | NR | NR | NR | Age-appropriate screening |

| ES, 200932 | Guideline | No known increased risk of breast cancer | NR | NR | Follow screening guidelines for cisgender women |

Note: ACOG = American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, CCS = Canadian Cancer Society, CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CETH = Center of Excellence for Transgender Health, CRHC = Canadian Rainbow Health Coalition, CSH = cross-sex hormone, IPPF = International Planned Parenthood Federation, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, NA = not applicable, NBCCEDP = National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program, NHS = National Health Service, NR = not reported, SHC = Sherbourne Health Centre, ES = Endocrine Society, THIP = Transgender Health Information Program, TTSES = Transcend Transgender Support & Education Society, VCH = Vancouver Coastal Health.

Cross-sex hormone use was variably termed as hormone use, feminizing hormone use, gender-affirming hormone, estrogen or progestin.

Or other screening test (not specified) as appropriate.

Upper age limit not reported.

Duration not reported.

Include estrogen plus progestin use for more than 5 years, family history of breast cancer, body mass index greater than 35.

Specific eligibility requirements not reported.

Cross-sex hormone regimen that includes estrogen.

For trans women in general (i.e., CSH use not specified), recommendations varied.5,28,30–32 One document recommended diagnostic mammography for those with breast implants and consideration of annual magnetic resonance imaging for those 30–69 years of age with a family history suggestive of hereditary breast cancer.28 Two documents recommended screening for those with developed breast tissue,5,30 1 recommended screening as per guidelines for cisgender women,32 and 1 recommended age-appropriate screening.29 None of these documents provided specific information on the modality or interval.

Interpretation

We found limited evidence of very low certainty that did not show an effect of CSHs on breast cancer risk in trans women or trans men. Evidence on the effect of CSHs on breast cancer prognosis and mortality was not identified. There was a lack of evidence on the benefits of breast screening, and very little evidence on harms. Further evidence of very low certainty showed that trans women experienced minimal pain during mammography and ultrasonography. There was minimal agreement on screening recommendations for trans people. The majority of the clinical practice documents identified provided recommendations for distinct subgroups of trans people based on the presence of breast tissue and history of CSH exposure. There was an observed preference for routine screening with mammography for trans men without chest reconstruction. This is not surprising, as trans men without chest reconstruction and without CSH exposure likely have the same risk for breast cancer as most cisgender women.10 There was also agreement that CSH exposure should be considered when determining breast screening eligibility for trans women.

The topics of breast screening and the effect of CSHs on breast cancer outcomes among trans people have not been rigorously and thoroughly researched. Previous reviews on similar topics6,10,33–36 have largely summarized published case reports and series on breast cancer in trans people, as well as the studies included in our 2 reviews of primary research.

Strengths and limitations

Key strengths of our systematic reviews include comprehensive search strategies, robust citation-screening processes and the application of reputable tools for analyzing the evidence and assessing its certainty. Key limitations are due to the nature of the available evidence and methodological decisions applied throughout the reviews. Observational designs were used in all 3 studies examining the effect of CSHs on breast cancer risk,20–22 and indirect comparisons were used in 2 studies.20,21 Across these studies, few details were provided regarding the nature of CSH exposure, and the length of follow-up varied and, in many cases, may have been too short to reasonably observe the effect of CSHs on long-term breast cancer risk. Two studies may have also been underpowered.20,22 The study on painfulness of screening is limited by its small sample, insufficient information on validity and reliability of the outcome measure, and generalizability.23 The quality of the guidelines in review 3 was low. Very few documents reported the quality of the evidence on which recommendations were based or the strength of recommendations. In all 3 reviews, we searched only for evidence available in English owing to limited resources to appropriately handle evidence in other languages, which could have resulted in language bias. The search was also limited to evidence published between 1997 and 2017. Although data extraction and quality assessments were verified by a second reviewer, these tasks were not performed independently. Owing to the insufficient quantity of primary research, certain GRADE domains could not be assessed. Although the quality of included guidelines was assessed with the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II instrument, we did not verify or critically appraise the evidence cited to support recommendations.

Conclusion

Conclusions cannot be drawn from the sparse evidence of very low certainty in these 3 reviews. The 2 systematic reviews of primary research showed limited evidence, thus preventing the formation of any definitive conclusions about the impact of breast screening in trans people and the effect of CSHs on breast cancer outcomes. The systematic review of guidelines and position statements showed that breast screening is generally recommended for trans people; however, recommendations varied. In the absence of high-quality scientific evidence, organized screening programs will need to supplement scientific evidence with sources of contextual evidence (e.g., professional expertise and lived experience) when developing screening recommendations and policies for trans people. Furthermore, despite the limited evidence, the argument can be made that screening should be made available to trans people who meet program eligibility requirements in the same way that it is available to cisgender women. Based on our findings, it is clear that large-scale prospective, comparative, trans-specific, quantitative research with a long duration of follow-up is needed to produce reliable estimates of the effects of CSHs on breast cancer outcomes and the potential benefits and harms of screening. Given the large sample required for such studies and the challenges with reaching trans people for research,37 future research may benefit from data linkage and algorithms to improve the identification of trans people in existing population-based health databases. Alternatively, future etiologic research of sufficient sample size may include a multisite cohort study in community clinics serving trans people.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jessie Cunningham for her assistance with developing the search strategies and conducting the literature searches. They also thank Emma Sabo for her assistance with article retrieval. Meghan Walker and Chamila Adhihetty provided valuable feedback on the protocols, and Chamila Adhihetty and Gillian Bromfield provided feedback on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Mufiza Farid-Kapadia is currently employed by Roche but was not at the time these systematic reviews were conducted. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Olivia Meggetto, Leslea Peirson, Mafo Yakubu, Mufiza Farid-Kapadia, Michelle Costa-Fagbemi, Shamara Baidoobonso, Jessica Moffatt, Anna Chiarelli and Derek Muradali were involved in the conception and design of 1 or more of the 3 reviews. Leslea Peirson, Michelle Costa-Fagbemi and Shamara Baidoobonso collected, analyzed and interpreted the data for review 1. Olivia Meggetto, Mafo Yakubu and Shamara Baidoobonso collected, analyzed and interpreted the data for review 2. Mafo Yakubu, Mufiza Farid-Kapadia and Shamara Baidoobonso collected, analyzed and interpreted the data for review 3. Olivia Meggetto, Lauren Chun and Derek Muradali drafted the manuscript. All of the authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: Research reported in this paper was supported exclusively by Cancer Care Ontario.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/3/E598/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.Gender identity and gender expression. Toronto: Ontario Human Rights Commission; [accessed 2017 Oct 27]. Available: www.ohrc.on.ca/en/policy-preventing-discrimination-because-gender-identity-and-gender-expression/3-gender-identity-and-gender-expression. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer GR, Travers R, Scanlon K, et al. High heterogeneity of HIV-related sexual risk among transgender people in Ontario, Canada: a province-wide respondent-driven sampling survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:292. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giblon R, Bauer GR. Health care availability, quality, and unmet need: a comparison of transgender and cisgender residents of Ontario, Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:283. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2226-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feldman JL, Goldberg J. Transgender primary medical care: suggested guidelines for clinicians in British Columbia. Vancouver: Vancouver Coastal Health, Transcend Transgender Support & Education Society, and Canadian Rainbow Health Coalition; 2006. [accessed 2017 Feb 17]. Available: http://lgbtqpn.ca/wp-content/uploads/woocommerce_uploads/2014/08/Guidelines-primarycare.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahl M, Feldman JL, Goldberg J, et al. Endocrine therapy for transgender adults in British Columbia: suggested guidelines. Vancouver: Vancouver Coastal Health; 2015. [accessed 2017 Feb 11]. Available: www.phsa.ca/transcarebc/Documents/HealthProf/BC-Trans-Adult-Endocrine-Guidelines-2015.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mueller A, Gooren L. Hormone-related tumors in transsexuals receiving treatment with cross-sex hormones. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;159:197–202. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute of Medicine Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: building a foundation for better understanding. Washington: National Academies Press; 2011. pp. 61–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheim A, Bauer G. Breast and cervical cancer screening among trans Ontarians: a report prepared for the Screening Saves Lives Program of the Canadian Cancer Society. Ottawa: Trans PULSE Project; 2013. [accessed 2017 Mar 15]. Available: http://transpulseproject.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Trans-PULSE-Cancer-Screening-Report-for-Screening-Saves-Lives-V_Final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bazzi AR, Whorms DS, King DS, et al. Adherence to mammography screening guidelines among transgender persons and sexual minority women. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:2356–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips J, Fein-Zachary VJ, Mehta TS, et al. Breast imaging in the transgender patient. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202:1149–56. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.10810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowen S, Zwi AB. Pathways to “evidence-informed” policy and practice: a framework for action. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The 519’s Glossary of Terms, facilitating shared understandings around equity, diversity, inclusion and awareness. Toronto: The 519; 2018. [accessed 2018 July 30]. Available: www.the519.org/education-training/glossary. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Distiller (Distiller SR systematic review software) Ottawa: Evidence Partners; 2016. [accessed 2017 Nov 3]. Available: https://www.evidencepartners.com/products/distillersr-systematic-review-software/ [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2013. [accessed 2017 Feb 3]. Available: wwwohrica/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182:E839–42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schünemann H, Brozek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Version 3.2. GRADE Working Group; [accessed 2017 Feb 11]. [updated 2013]. Available: http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/app/handbook/handbook.html. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown GR, Jones KT. Incidence of breast cancer in a cohort of 5135 transgender veterans. Breast Can Res Treat. 2015;149:191–8. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gooren LJ, van Trotsenburg MA, Giltay EJ, et al. Breast cancer development in transsexual subjects receiving cross-sex hormone treatment. J Sex Med. 2013;10:3129–34. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuroda H, Ohnisi K, Sakamoto G, et al. Clinicopathological study of breast tissue in female-to-male transsexuals. Surg Today. 2008;38:1067–71. doi: 10.1007/s00595-007-3758-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weyers S, Villeirs G, Vanherreweghe E, et al. Mammography and breast sonography in transsexual women. Eur J Radiol. 2010;74:508–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breast cancer screening information for trans men. Toronto: Canadian Cancer Society; 2017. [accessed 2017 Feb 16]. Available: http://convio.cancer.ca/site/PageServer?pagename=SSL_ON_HCP_HCPTM_Chest#.WKYDBm8rKUk. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breast cancer screening information for trans women. Toronto: Canadian Cancer Society; 2017. [accessed 2017 Feb 16]. Available: http://convio.cancer.ca/site/PageServer?pagename=SSL_ON_HCP_HCPTW_Breast#.WKYCe28rKUk. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deutsch MB, editor. Guidelines for the primary and gender-affirming care of transgender and gender non-binary people. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Center of Excellence for Transgender Health, Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of California, San Francisco; 2016. [accessed 2017 Feb 15]. Available: http://transhealth.ucsf.edu/protocols. [Google Scholar]

- 27.IMAP statement on hormone therapy for transgender people. London (UK): International Planned Parenthood Federation; 2015. [accessed 2017 Feb 19]. Available: www.ippf.org/sites/default/files/ippf_imap_transgender.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guidelines and protocols for hormone therapy and primary health care for trans clients. Toronto: Rainbow Health Ontario, Sherbourne Health Centre; 2015. [accessed 2017 Feb 16]. Available: http://sherbourne.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Guidelines-and-Protocols-for-Comprehensive-Primary-Care-for-Trans-Clients-2015.pdf/ [Google Scholar]

- 29.Updated National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program guidelines. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. [accessed 2017 Feb 18]. Available: http://hrc-assets.s3-website-us-east-1.amazonaws.com//files/assets/resources/AskDrMiller122013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guidance: NHS population screening: working with minority or hard to reach groups. London (UK): Public Health England; 2013. [accessed 2017 Feb 15]. Available: www.gov.uk/government/publications/nhs-population-screening-equitable-access-tips/nhs-population-screening-working-with-minority-or-hard-to-reach-groups. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Committee of Health Care for Underserved Women. Committee opinion no. 512: health care for transgender individuals. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1454–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823ed1c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis P, Delemarre-van de Waal HA, et al. Endocrine treatment of transsexual persons: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3132–54. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quinn GP, Sanchez JA, Sutton SK, et al. Cancer and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) populations. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:384–400. doi: 10.3322/caac.21288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braun H, Nash R, Tangpricha V, et al. Cancer in transgender people: evidence and methodological considerations. Epidemiol Rev. 2017;39:93–107. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxw003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stone JP, Hartley RL, Temple-Oberle C. Breast cancer in transgender patients: a systematic review. Part 2: female to male. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44:1463–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hartley RL, Stone JP, Temple-Oberle C. Breast cancer in transgender patients: a systematic review. Part 1: male to female. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44:1455–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reisner SL, Deutsch MB, Bhasin S, et al. Advancing methods for US transgender health research. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016;23:198–207. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.