Abstract

The formation of distant metastasis resulting from vascular dissemination is one of the leading causes of mortality in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). This metastatic dissemination initiates with the adhesion of circulating cancer cells to the endothelium. The minimal requirement for the binding of leukocytes to endothelial E-selectins and subsequent transmigration is the epitope of the fucosylated glycan, sialyl Lewis x (sLex), attached to specific cell surface glycoproteins. sLex and its isomer sialyl Lewis a (sLea) have been described in NSCLC, but their functional role in cancer cell adhesion to endothelium is still poorly understood. In this study, it was hypothesised that, similarly to leukocytes, sLe glycans play a role in NSCLC cell adhesion to E-selectins. To assess this, paired tumour and normal lung tissue samples from 18 NSCLC patients were analyzed. Immunoblotting and immunohisto-chemistry assays demonstrated that tumour tissues exhibited significantly stronger reactivity with anti-sLex/sLea antibody and E-selectin chimera than normal tissues (2.2- and 1.8-fold higher, respectively), as well as a higher immunoreactive score. High sLex/sLea expression was associated with bone metastasis. The overall α1,3-fucosyltransferase (FUT) activity was increased in tumour tissues, along with the mRNA levels of FUT3, FUT6 and FUT7, whereas FUT4 mRNA expression was decreased. The expression of E-selectin ligands exhibited a weak but significant correlation with the FUT3/FUT4 and FUT7/FUT4 ratios. Additionally, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) was identified in only 8 of the 18 tumour tissues; CEA-positive tissues exhibited significantly increased sLex/sLea expression. Tumour tissue areas expressing CEA also expressed sLex/sLea and showed reactivity to E-selectin. Blot rolling assays further demonstrated that CEA immunoprecipitates exhibited sustained adhesive interactions with E-selectin-expressing cells, suggesting CEA acts as a functional protein scaffold for E-selectin ligands in NSCLC. In conclusion, this work provides the first demonstration that sLex/sLea are increased in primary NSCLC due to increased α1,3-FUT activity. sLex/sLea is carried by CEA and confers the ability for NSCLC cells to bind E-selectins, and is potentially associated with bone metastasis. This study contributes to identifying potential future diagnostic/prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets for lung cancer.

Keywords: NSCLC, CEA, selectin ligands, metastasis

Introduction

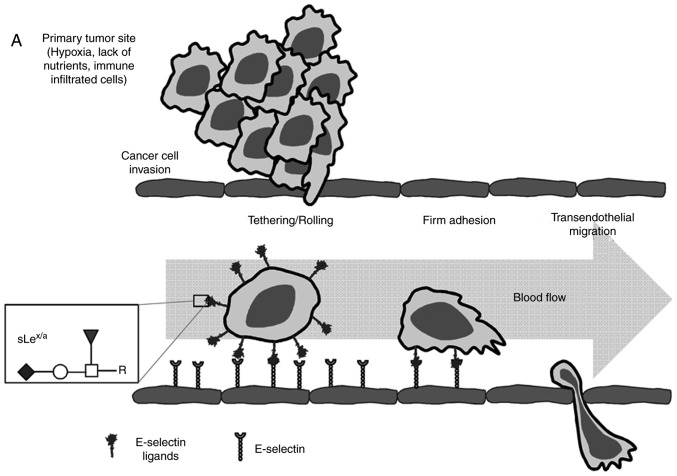

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, with 1.8 million deaths predicted in 2018 (1). Approximately 85% of all lung cancers are non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), with adenocarcinoma (AC) being the major histological subtype (2). In NSCLC, the primary cause of mortality is distant metastasis resulting from hematogenous dissemination of cancer cells (3). Through this route, NSCLC cells spread to the brain, contralateral lung, bones, liver and the suprarenal glands, with consequent impact on patient's survival (3,4). The high mortality of NSCLC means there is an urgent requirement to identify mechanisms associated with NSCLC progression, in order to aid early determination of its metastatic potential and proper staging. Cancer metastasis is a multifaceted process that comprises multiple steps. After invading the stroma, tumour cells require the establishment of new vasculature from the pre-existing vasculature via angiogenesis to provide nutrition and an oxygen supply (5). Fast tumour growth requires that invasive tumour cells adapt to the hostile hypoxic microenvironment and protect from immune cell attack; otherwise, they do not survive (6). These factors lead to dramatic changes in cell signalling and protein expression that enables the cells to surpass the challenges of leaving the primary tumour, migrate to distant sites and establish a metastatic focus (7). One of the most critical steps for metastasis is the ability of circulating cancer cells to adhere the vascular endothelium (Fig. 1A). The initial adhesive interactions are dictated by the calcium-dependent binding of circulating cancer cells to endothelial E-selectins expressed in microvasculature at inflammatory sites (8,9). E-selectin ligands are terminal lactosaminyl tetrasaccharides, prototypically the sialyl Lewis x (sLex) and sialyl Lewis a (sLea) glycan antigens, displayed on cell surface protein or lipid scaffolds (10). In proteins, these structures are found at terminal ends on the β-1,6 branching of N-glycans or O-glycans. Patients with NSCLC are reported to overexpress sLex and sLea antigens on tumour tissues and serum proteins (11,12). The higher expression of sLex and sLea in NSCLC has been associated with enhanced metastatic activity and poor prognosis (13,14); however, the contribution of these antigens to metastasis remains unclear. Additionally, the mechanism driving sLex and sLea overexpression in NSCLC is poorly understood. Nevertheless, in cancer, the expression of the glycosyltransferases involved in sLex and sLea biosynthesis is controlled by elements in the tumour microenvironment, such as hypoxia and oncogene expression (15). This suggests that the hostile microenvironment of a primary tumour triggers sLex and sLea expression, enabling cancer cells to adapt and establish adhesive interactions with endothelium. sLex and sLea are isomers whose structure consists in α2,3-sialylated, and α1,3/4-fucosylated type 2 or type 1 lactosamine chains, respectively (Fig. 1B) (16,17). The α2,3-sialyltransferases (ST3GAL3, ST3GAL4, and ST3GAL6) and the α1,3-fucosyltransferases (FUT3, FUT4, FUT5, FUT6 and FUT7) can respectively catalyse terminal sialylation and fucosylation steps (18). The same enzymes may also be involved in other glycosylation steps that compete with sLex and sLea antigen biosynthesis, as FUT4 efficiently catalyses the synthesis of non-sialylated antigens, such as Lewis x and Lewis y (19,20). The activity of each enzyme is generally tissue-specific and depends mostly on its expression level.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the multistep metastatic process in cancer and main structures involved. (A) Contribution of sLex/sLea antigens in facilitating cell adhesion to E-selectins. There are four main steps in the extravasation process, including tethering and rolling, integrin activation, firm adhesion and transendothelial migration. Metastatic dissemination is facilitated by interactions between tumour cells and endothelium in distant tissues. These interactions are mediated by E-selectins expressed by activated endothelial cells and the corresponding E-selectin ligands expressed on the cell surface of cancer cells. These ligands are prototypically the sLex and sLea antigens, displayed on cell surface proteins or lipid scaffolds. (B) Structure and schematic representation of the biosynthesis of sialyl Lewis antigens. sLea and sLex antigens are sialofucosylated isomer tetrasaccharides, derived from type 1 or type 2 sugar chains, respectively, attached to N- or O-glycan residues. The two types of structures are sialylated by the action of the indicated α2,3-sialyltransferases and successively fucosylated by the action of the FUT3 (in type 1 chains), and FUT3, 4, 5, 6 or 7 (in type 2 chains). FUT, fucosyltransferase; sLea/x, sialyl Lewis a/x.

As aforementioned, in spite of the overexpression of sLex and sLea in NSCLC cells, it is unknown whether they confer adhesive capacity of cancer cells to the endothelium. sLex and sLea functional roles depend on their density and availability at the cell surface, specifically their presentation by specific scaffolds to potentially be recognised by E-selectins expressed on activated endothelial cells. In the present study, it was hypothesised that sLex/sLea glycans serve a role in NSCLC cell adhesion to E-selectins. It was further hypothesised that it is carried by protein scaffolds specific to NSCLC. To address this, in this study, sLex/sLea expression and E-selectin reactivity were compared in patient-derived tumour and matched normal lung tissues. Furthermore, the expression levels of fucosyltransferases and sialyltransferases involved in the biosynthesis of sLex and sLea glycans were analysed. Additionally, the ability of these ligands to adhere to E-selectin was evaluated, and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) was identified as a protein scaffold of E-selectin ligands in NSCLC.

Improved understanding of the glycosidic alterations occurring throughout tumour progression, as well as the pathophysiological role of sLex/sLea glycans-associated protein scaffolds in tumour cell adhesion to E-selectins, will aid the identification of potential therapeutic targets and may enable improved prediction of tumour progression and metastasis formation in NSCLC.

Materials and methods

Patient and tissue specimens

The present study involved 18 consecutive patients with NSCLC who underwent lobectomy due to lung cancer between July 2011 and January 2012 at the Thoracic Surgery Department of Hospital Pulido Valente (Lisbon, Portugal). The inclusion criteria for the patients enrolled in this study were as follows: i) Patients with age ≥18 years; ii) suspected or proven lung cancer with indication for pulmonary resection; and iii) histology of lung adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. The exclusion criteria were: i) Patients with age <18 years; ii) previous chemotherapy or radiotherapy; iii) histology compatible with small cell lung cancer, large cell lung cancer, lung metastases or benign disease; and iv) pregnant women. A total of 14 patients were further diagnosed with AC and four with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). The median age of the patients was 65 years (48-83 years); 13 patients were male. For each patient, fragments of pulmonary tumour tissue and normal lung tissue were collected and immediately stored in liquid nitrogen until further processing. The determination of the histological type was performed by the Pathology Department from the same hospital. Tumour staging was classified according to the TNM classification system based on the International Union Against Cancer 8th edition (21). A 5-year follow-up of the patients after the initial surgical procedure was conducted, and clinical data were collected into a database.

For bone metastasis analysis, sections of two cases of lung cancer with the corresponding metastasis, from male patients aged 58 and 86 years, were used. Samples were collected, in the first case from the left lung and in the second case from the right lower lobe. Bone metastasis tissues were taken from a lumbar spine injury (L5-S1) and from the right clavicle, respectively.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Norte. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. A summary of the clinical data is available in Table SI.

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation analysis

Whole tissue lysates were obtained by homogenising patient tissues in lysis buffer [150 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 2% Nonidet P-40 and protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics)]. After centrifugation for 2 min at 17,000 × g and 4°C, the quantity of protein within the supernatant was estimated using a Pierce™ Bicinchoninic Acid Protein Assay kit (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and stored for further use. Immunoprecipitated CEA was obtained by pre-clearing tissue lysates with protein G-agarose, followed by incubation for 2 h at 4°C with 1 µg/µl of anti-human CEA (CD66E) monoclonal antibody (mAb; cat. no. 21278661; ImmunoTools GmbH). The immunoprecipitate was collected with protein G-agarose beads, boiled and the released proteins were analysed via western blotting.

After an extensive search in the literature and several attempts with the present cohort, it was concluded that there is no consensus regarding the optimal loading control to use for NSCLC studies, with marked upregulation or downregulation of some of the most used housekeeping genes (β-tubulin, β-actin, GAPDH) in human lung tumour tissues compared with normal lung tissues (22-24). For this reason and due to sample limitation, these loading controls were not used in dot blotting and western blotting experiments. As the best possible alternative, an exact amount of protein was always loaded for all experiments.

For dot blot analysis, 10 µg of tissue lysates were applied to a nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). For western blot analysis, 20 µg of tissue lysates or immuno-precipitates were electrophoresed under reducing conditions on an 8% polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a polyvi-nylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Membranes were incubated in blocking solution [10% non-fat milk diluted in PBS-0.1% Tween 20 for dot blotting, and TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T) for western blotting experiments] overnight at 4°C under agitation. For sLex/sLea and CEA detection, nitrocellulose or PVDF membranes were stained with HECA-452 mAb (1:1,000; cat. no. 321302; BioLegend, Inc.) or anti-human CD66E mAb (1:1,000; cat. no. 21278661; ImmunoTools GmbH), followed by staining with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary mAb [anti-rat IgM-HRP for HECA-452 staining (1:2,500; cat. no. 3080-05; SouthernBiotech); anti-mouse Ig-HRP for CD66E staining (1:2,500; cat. no. 554002; BD Pharmingen; BD Biosciences)]. E-selectin ligand staining was performed using a 3-step protocol, in the presence of 2 mM CaCl2, which included staining with soluble mouse E-selectin-human Fc Ig chimera (E-Ig; 1:500; cat. no. 575-ES-100; R&D Systems, Inc.), followed by the addition of rat anti-mouse E-selectin (CD62E) mAb (1:1,000; cat. no. 550290; BD Pharmingen; BD Biosciences) and then HRP-conjugated anti-rat IgG (1:2,000; cat. no. 3030-05; SouthernBiotech) (32). Membranes were incubated with Lumi-Light Western Blotting Substrate (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's protocols and detected with autoradiography film. All blots were replicated at least twice. Image analysis was performed using ImageJ 1.48v software (National Institutes of Health), and arbitrary units were defined based on the intensity detected by the software.

Gene expression measurements

Tissue samples were homogenised and total RNA was isolated following the instructions of the NZY Total RNA Isolation kit (NZYTech). cDNA synthesis was performed using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-q)PCR was performed using TaqMan probes methodology (6-carboxyfluorescein as a fluorescent dye) and TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's protocols and in triplicates. The thermal cycling conditions used were as follows: 1 cycle of 2 min at 50°C, 1 cycle of 10 min at 95°C, and 50 cycles of 15 sec at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C. For each primer/probe set, the Assay ID (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was the following: FUT3, Hs00356857_m1; FUT4, Hs01106466_s1; FUT5, Hs00704908_s1; FUT6, Hs00173404_m1; FUT7, Hs00237083_m1; ST3GAL3, Hs00196718_m1; ST3GAL4, Hs00272170_m1; and ST3GAL6, Hs00196086_m1. mRNA expression was normalised using the geometric mean of the expression of the endogenous controls, ACTB (Hs99999903_m1) and GAPDH (Hs99999905_m1). The relative mRNA level of expression was computed as a permillage fraction (‰), calculated using the 2−ΔCq ×1,000 formula (25-27), which infers the number of mRNA molecules of the gene of interest, for every 1,000 molecules of endogenous controls. RT-qPCR was performed in a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and the results were analysed using Sequence Detection Software version 1.3 (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

α1,3-FUT activity assay

α1,3-FUT activity was measured in whole tissue lysates. The assay mixture contained 50 mM Na/cacodylate buffer pH 6.5, 15 mM MnCl2, 0.5% Triton X-100, 5 mM ATP, 0.1 mM unlabelled GDP-fucose from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA), 55000 dpm GDP-[14C] fucose (PerkinElmer, Inc.) and 300 µg fetuin (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), theoretically corresponding to 0.8 mM Siaα2,3Galβ1,4GlcNAc-R acceptor sites. The enzyme reaction was performed in triplicate at 37°C for 2 h, and then the products were precipitated, washed and counted by liquid scintillation. Controls without the acceptor (fetuin) were run in parallel, and the incorporation was subtracted. Homogenates of COLO-205 cells (28) (kindly provided by Professor Fabio Dall'Olio, University of Bologna, Italy) were used as positive controls.

Adhesion assays

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells transfected either with cDNA encoding the full length of the human E-selectin (CHO-E) or with a mock empty pMT2 vector (CHO-mock; kindly provided by Professor Robert Sackstein, Brigham And Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School) (29) were grown in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) supplemented with 10% of heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mM of L-glutamine, 100 µg/ml of penicillin/streptomycin, 1 mM of sodium pyruvate and 0.1 mM of MEM non-essential amino acids solution (all from Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Adhesion assays were performed based on the modified Stamper-Woodruff binding assay that mimics blood flow interactions (30,31). Briefly, total tissue lysates or immunoprecipitated proteins were spotted on glass slides, dried and blocked with 1% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 1 h at room temperature (RT). CHO-mock or CHO-E cells, resuspended in Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) containing 2 mM CaCl2 (HBSS-Ca) or 5 mM EDTA (HBSS-EDTA; negative control), were overlaid onto a protein spot on the glass slides. In certain cases, CHO-E cells were previously incubated with 20 µg/ml of function-blocking anti-CD62E (clone 68-5H11; cat. no. 555648; BD Biosciences) or isotype control mAb (clone mopc-21; cat. no. 400102; BioLegend, Inc.). Slides were then incubated with orbital rotation at 80 RPM for 30 min at 4°C, and subsequently placed in HBSS-Ca or HBSS-EDTA to drain non-adherent cells. After fixing the cells with 3% glutaraldehyde for 10 min at 4°C, the adherent cells were examined under a phase contrast microscope (Nikon Digital Eclipse C1 system; magnification, ×100; Nikon Corporation), and representative photomicrographs (3 frames per sample) were acquired for analysis. The number of cells adherent to glass slides and observed in each photomicrograph was counted using ImageJ 1.48v software (32).

Flow cytometry: The cell surface expression of E-selectin was analysed in CHO-E and CHO-mock cells using anti-E-selectin monoclonal antibody (5 µl; clone 68-5H11, cat. no. 555648; BD Biosciences), followed by a anti-mouse Ig-FITC secondary antibody (1 µl; cat. no. f0479; Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Antibody staining was performed for 30 min at 4°C followed by incubation with fluorescent-labelled secondary antibody (1 µl) for 15 min at RT in the dark. Background levels were determined in control assays by incubating cell suspensions with isotype control mAb (5 µl; clone mopc-21; cat. no. 400102; BioLegend, Inc.) and fluorescent-labelled secondary antibody. The experiments were performed in an Attune® Acoustic Focusing Cytometer (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and the results were analysed using the program FlowJo v10.0.7 (FlowJo, LLC).

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue specimens were fixed in 10% formalin for 24 h at 4°C and after embedded in paraffin. Paraffin-embedded sections of tumour tissue (2 µm) were submitted to antigen retrieval by heating at 94°C in Trilogy pre-treatment solution (Cell Marque; Merck KGaA) for 20 min. After incubation with peroxidase block solution (Atom Scientific Ltd.), sections were stained with anti-CD66E mAb (1:100; cat. no. 21278661; ImmunoTools GmbH) or anti-sLex/sLea HECA-452 mAb (1:50; cat. no. 321302; Biolegend, Inc.) for 1 h in Diamond Antibody Reagent (cat. no. 938B-09; Cell Marque) containing 1% BSA. For the washings, TBS-T was used. For E-selectin staining, E-Ig chimera was used (0.5 µg/100 µl; cat. no. 575-ES-100; R&D Systems, Inc.) for 30 min, followed by staining with anti-CD62E mAb (1:50; cat. no. 550290; BD Pharmingen; BD Biosciences) for 30 min, all in Diamond Antibody Reagent containing 1% BSA. In this case, TBS-T containing 2 mM CaCl2 (TBS-T-Ca) was used for the washings (33). All antibodies were incubated at RT. Slides were then stained using HiDef Detection HRP Polymer System (Cell Marque; Merck KGaA) for 10 min at RT and the colour was developed using 3,3'-diaminobenzidine solution (ScyTek Laboratories, Inc.). After nuclear contrast staining with haematoxylin (3 min at RT) and mounting with Quick-D mounting medium, the slides were visualised under a light microscope with coupled camera by two certified independent pathologists. A semi-quantitative approach was established for tissue slide evaluation (34), to calculate the immunoreactive score (IRS). The IRS is calculated by multiplying two scores: The cell proportion score that is 0 if all cells were negative, or 1 if <25%, 2 if 26-50%, 3 if 51-75% and 4 if >75% cells were stained; and the staining intensity score that is 0 when no stain was found, or 1 if weak, 2 if intermediate and 3 if strong staining intensity was observed. All images were acquired with magnification, ×10, and for the semi-quantitative analysis, 4 fields per section were evaluated.

Statistical analysis

Data from normal tissues were paired with data from matched tumour tissues and statistical differences were analysed using paired t-test (data with a normal distribution) or Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test (data with a non-normal distribution). The correlations between data were analysed using Spearman correlation and categorized as weak (r>0.3), moderate (r>0.5) and strong (r>0.7). To investigate associations between gene mRNA, sLex/sLea and E-selectin ligand expression, and clinical features the Fisher's exact statistical test was used. The multivariate survival model used was the Cox proportional hazards model, performed with R 3.6.0 (‘survival' package; https://github.com/therneau/survival). In case of multiple comparisons, one-way ANOVA tests were performed to test the statistical difference between the groups of the study, with Tukey's multiple comparison post hoc test. Overall survival was defined as the time from diagnosis to the date of death (months). Patients alive at the end of the study or who succumbed to clearly non-cancer-related causes were censored. Tests were considered statistically significant when P<0.05 and marginally significant when 0.05<P<0.1. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Results

E-selectin ligands and sLex/sLea antigens are overexpressed in NSCLC tumour tissues

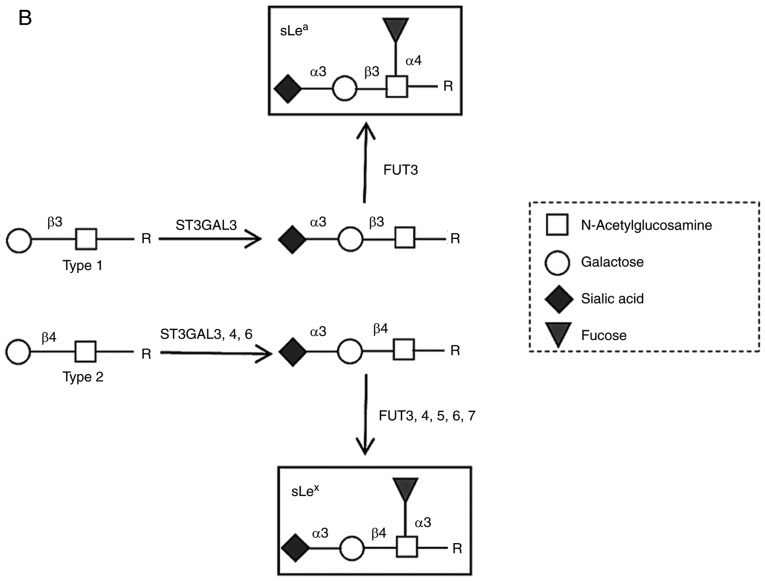

To ascertain the E-selectin ligand expression in NSCLC, 18 normal and matched tumoral lung tissues were compared for reactivity to HECA-452 mAb, an antibody that recognises both sLex and sLea structures, and E-Ig, an E-selectin chimera that recognises E-selectin ligands. Immunoblotting revealed that all tissues showed reactivity with HECA-452 mAb and E-Ig, which was significantly higher (2.2- and 1.8-fold) in tumour samples compared with matched normal samples (Fig. 2A and B). Furthermore, the intensity of the reactivity of both stainings exhibit a strong positive correlation (r=0.748, P<0.001; Fig. 2C). Immunohistochemistry revealed that tumoral tissue also exhibited stronger reactivity to both HECA-452 mAb (IRS, 4-9 vs. 1) and E-Ig (IRS, 6-9 vs. 2) compared with normal tissue (Fig. 2D). These results suggested that sLex/sLea antigens and E-selectin ligands in NSCLC exhibit increased expression in tumour tissues compared with normal tissues.

Figure 2.

NSCLC has increased anti-sLex/sLea mAb and E-selectin reactivity. (A) Dot blot analysis of anti-sLex/sLea mAb reactivity in matched normal and tumour proteins. Total lysates of N or T tissues were spotted on nitrocellulose membrane and stained with HECA-452 mAb. Left panel, representative dot blot analysis of the HECA-452 mAb reactivity. Right, the intensity of each dot blot spot, determined using ImageJ 1.48v software and expressed as arbitrary units. Box-and-whisker plots represent median, and lower and upper quartile values (boxes), ranges and all values for each group (black dots). (B) Dot blot analysis of E-selectin reactivity in matched normal and tumour proteins. Total lysates of N or T tissues were spotted on nitrocellulose membrane and stained with E-Ig. Left, representative dot blot analysis of E-Ig reactivity. Right, the intensity of each dot blot spot expressed as arbitrary units. Box-and-whisker plots represent median values, and lower and upper quartiles (boxes), ranges and all values for each group (black dots). *P<0.05, ***P<0.001. (C) Correlation between anti-sLex/sLea mAb and E-Ig staining intensity in tumour tissue. Correlation was analysed using Spearman's correlation coefficient. NSCLC has increased anti-sLex/sLea mAb and E-selectin reactivity. (D) Anti-sLex/sLea mAb and E-Ig reactivity in paraffin-embedded normal, tumour and metastasis sections. Sequential sections from representative normal, non-small cell lung cancer and bone metastasis tissues were stained with HECA-452 mAb (top) and E-Ig chimera (bottom) via immunohistochemistry. Nuclei stained with haematoxylin. Magnification, ×10. E-Ig, mouse E-selectin-human Fc Ig chimera; mAb, monoclonal antibody; N, normal; sLea/x, sialyl Lewis a/x; T, tumour.

The associations between sLex/sLea and E-selectin ligand expression, and clinical features such as histological type, stage of disease, gender, age, metastatic site and smoking habits were assessed. Considering the expression of sLex/sLea in tumour and normal tissue, it was found that patients who developed bone metastasis had a higher tumour/normal (T/N) ratio compared with patients who developed metastasis in other sites (P<0.05; Table I). Other clinical features showed no statistically significant association with sLex/sLea or E-selectin ligands.

Table I.

Relation between expression of sLex/sLea and E-selectin ligands with patient's clinical features.

| Clinical feature | sLex/a expression (mean T/N ratio ± SEM) | P-value | E-Selectin ligands expression (mean T/N ratio ± SEM) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histological type | 0.577 | >0.999 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma (N=14) | 1.710±0.165 | 1.557±0.185 | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma (N=4) | 1.448±0.220 | 1.633±0.321 | ||

| Stage of disease | 0.335 | <0.999 | ||

| I + II (N=11) | 1.500±0.222 | 1.556±0.189 | ||

| III (N=7) | 1.748±0.176 | 1.585±0.234 | ||

| Gender | >0.999 | <0.999 | ||

| Male (N=13) | 1.670±0.182 | 1.562±0.216 | ||

| Female (N=5) | 1.604±0.171 | 1.604±0.108 | ||

| Metastatic site | 0.033a | 0.500 | ||

| Bones (N=3) | 2.353±0.307 | 1.663±0.156 | ||

| Other sites (N=7) | 1.270±0.162 | 1.173±0.292 | ||

| Age | 0.347 | 0.153 | ||

| <median age (N=9) | 1.483±0.213 | 1.190±0.195 | ||

| ≥median age (N=9) | 1.820±0.166 | 1.958±0.172 | ||

| Smoking habits | <0.999 | <0.999 | ||

| Smoker (N=11) | 1.625±0.186 | 1.715±0.215 | ||

| Non-smoker (N=7) | 1.693±0.214 | 1.351±0.210 |

P<0.05. sLex/a; sialyl Lewis x/a; T/N, tumour/normal tissue.

Considering the correlation between sLex/sLea and E-selectin ligand expression, and the association between sLex/sLea expression and the development of bone metastasis, the expression of sLex/sLea and E-selectin ligands in bone metastasis tissue derived from patients with NSCLC was then assessed. Weak positive reactivity was observed in metastasized cells (IRS, 1-2; Fig. 2D), suggesting an important role for these structures in cancer progression and the promotion of metastasis. When considering the IRS, it is important to note that these samples were from bone metastases, which require a decalcification process for immunohistochemistry purposes. This process may result in a partial loss of antigen, considering the calcium-binding dependence of E-selectin binding (partially recovered by the addition of CaCl2). Furthermore, the primary tissue has a strong expression of E-selectin ligands that potentiates migration and leads to the formation of metastasis in distant sites. After E-selectin binding, cancer cells pass through the endothelium to colonize new sites, forming metastasis. During metastatic establishment in these new sites, the expression of biomarkers that potentiate migration is expected to decrease. Hence, a staining with a lower IRS (or equivalent to the normal section) was expected. Thus, an IRS of 1-2 in these tissues was considered a high score indicative of a role for E-selectin ligands in bone metastasis.

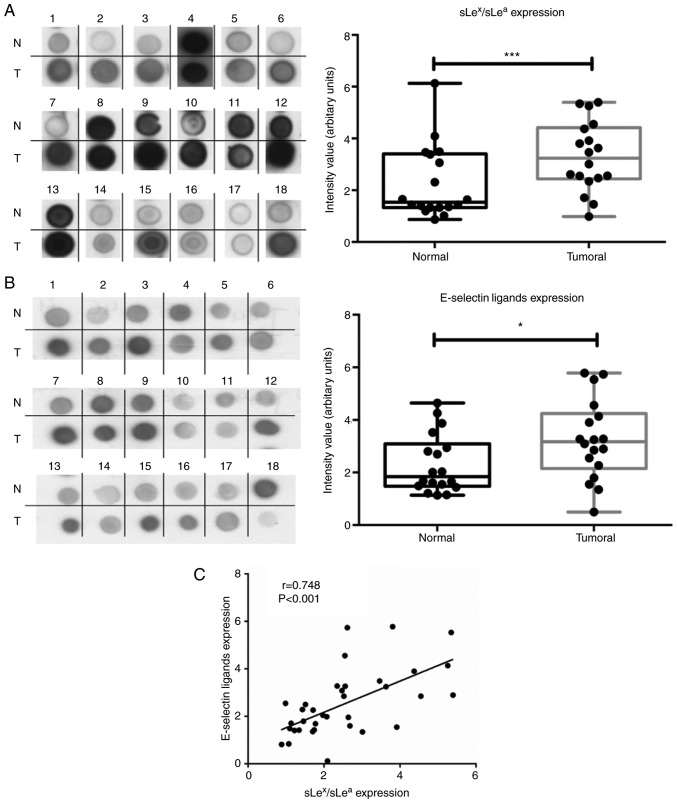

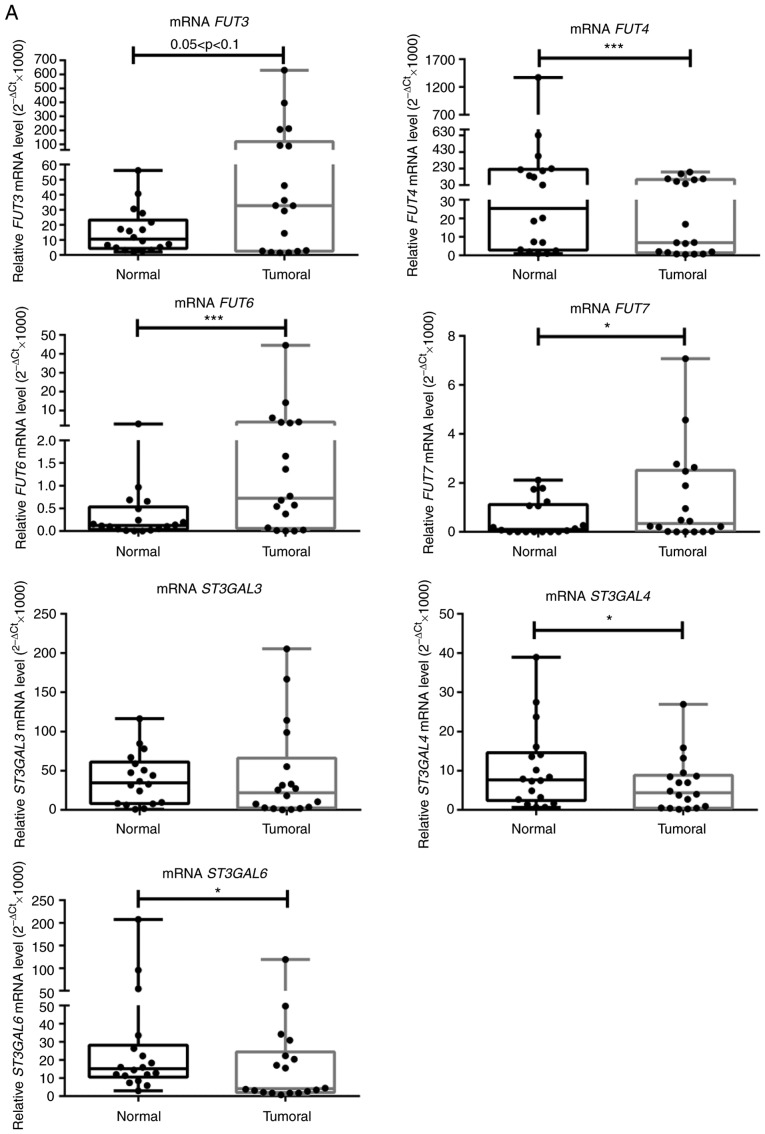

FUT3, FUT6 and FUT7 are upregulated in NSCLC tumour tissues

To gain further insight into the molecular basis of augmented E-selectin ligands in NSCLC, the expression of enzymes critical to the biosynthesis of sLex/sLea were subsequently compared in matched normal and tumour tissues (Fig. 1B). First, the expression of the genes that encode for the α1,3/4-fucosyltransferases (FUT3, FUT4, FUT5, FUT6 and FUT7) and α2,3-sialyltransferases (ST3GAL3, ST3GAL4 and ST3GAL6), which add fucose and sialic acid residues, respectively, to type 1 or type 2 glycan precursors of sLex/sLea, were evaluated via RT-qPCR analysis (Fig. 1B). With few exceptions, all genes were expressed in all samples and presented a broad range of expression levels. It was observed that FUT3 showed a marginally significant 2.3-fold increase in expression in tumour compared to normal tissue (0.05<P<0.1; Fig. 3A). FUT6 and FUT7 expression levels were significantly increased in NSCLC tissues samples compared with matched normal tissues (5.3- and 2-fold, respectively; P<0.001 and P<0.05, respectively; Fig. 3A). These results suggested increased α1,3-FUT activity in tumour tissue. A comparison of the relative levels of expression of α1,3-FUTs revealed that FUT7 is poorly expressed, compared with FUT6, and particularly with FUT3 and FUT4. Conversely, FUT4, ST3GAL4 and ST3GAL6 expression levels were significantly decreased by 3.1, 2 and 2.5 times, respectively, in tumour compared with normal tissues (P<0.001, P<0.05 and P<0.05, respectively). ST3GAL3 expression was not statistically different between normal and tumour tissue (Fig. 3A). FUT5 expression was not detected in the present study.

Figure 3.

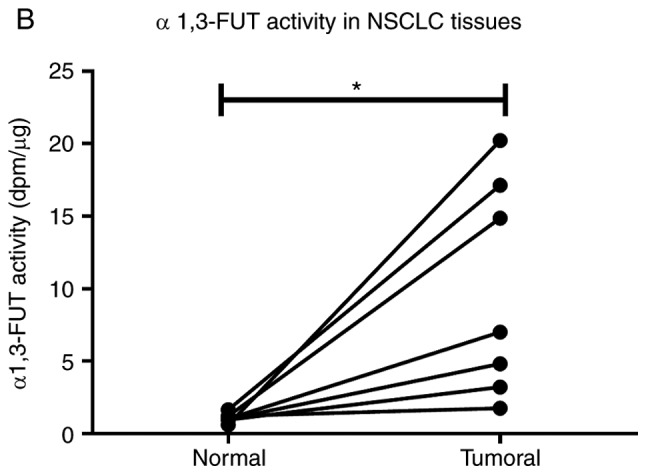

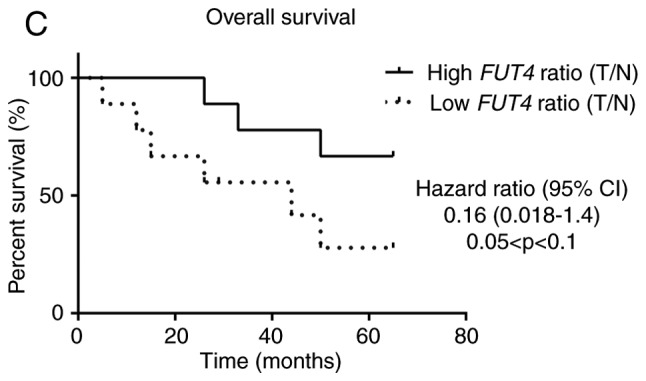

NSCLC tissues show upregulation of FUT3, FUT6 and FUT7 and increased α1,3-FUT activity. (A) Relative mRNA levels of FUT3, FUT4, FUT6, FUT7, ST3GAL3, ST3GAL4 and ST3GAL6 in normal and tumour tissues from patients with NSCLC, as determined via reverse transcription-quantitative PCR analysis. Values indicate the number of mRNA molecules of a certain gene per 1,000 molecules of the average of the endogenous controls (ACTB and GAPDH). Box-and-whisker plots represent median values, and lower and upper quartiles (boxes), ranges and all values for each group (black dots). *P<0.05, ***P<0.001. 0.05<P<0.1, marginally significant. NSCLC tissues show upregulation of FUT3, FUT6 and FUT7 and increased α1,3-FUT activity. (B) Evaluation of α1,3-FUT activity in tissue lysates. α1,3-FUT enzymatic activity was evaluated in lysates obtained from normal and NSCLC tissues derived from 7 patients. Activity was measured using fetuin as an acceptor. 0.05<P<0.1, marginally significant; *P<0.05. (C) Relationship between overall survival and FUT4 expression ratio. Curve plots of overall survival in 18 patients (vertical tick marks indicate censored cases). Patients with high FUT4 T/N ratios (n=9) and patients with low FUT4 T/N ratios (n=9) were separated based on the median value. The multivariate survival model used was the Cox proportional hazards model. 0.05<P<0.1, marginally significant. FUT, fucosyltransferase; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; ST3GAL, α2,3-sialyltransferase; T/N, tumour/normal.

Then, the enzyme activity of total α1,3-FUT was measured in matched samples. Due to sample limitation, only samples from 7 patients (namely patients 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7 and 9) were used. As presented in Fig. 3B, α1,3-FUT activity in tumour tissues was significantly increased compared with in matched normal tissues (P<0.05), confirming the gene expression data.

It was also assessed whether there was any correlation between the analysed genes and E-Ig staining in tumour tissues samples (data not shown). A moderate positive correlation was observed between the expression levels of FUT3 and FUT6 (r=0.517, P<0.05), FUT3 and FUT7 (r=0.624, P<0.01), and FUT6 and FUT7 (r=0.680, P<0.01), suggesting that the expression of these FUTs is regulated similarly (data not shown). Of note, a weak correlation was observed between the expression of E-selectin ligands, and the expression ratios of FUT3/FUT4 (r=0.369, P<0.01) and FUT7/FUT4 (r=0.366, P<0.05; data not shown). These data suggested that overexpression of FUT3 and FUT7 enzymes, and concomitant downregulation of FUT4 enzymes may promote E-selectin ligands expression in NSCLC.

Patients were then categorised in two groups (n=9/group), according to the FUT4 mRNA expression; those with FUT4 mRNA <10 and those ~30 (Fig. 3A). The group with lower FUT4 expression exhibited higher expression levels of E-selectin compared with the group with higher FUT4 expression (3.974±1.102 vs. 2.837±1.135; P<0.05; data not shown). Of note, the former group of patients displayed a lower overall survival (hazard ratio=0.16; 95% CI; 0.018-1.4; 0.05<P<0.1), suggesting that a lower FUT4 T/N expression ratio was a potential biomarker for poor prognosis (Fig. 3C). None of the other variables tested proved to be significant in the multivariate survival model used.

When subdividing the patients according to their tumours' histological type, it was possible to observe a marginally significantly higher ratio of FUT3 expression in patients with AC compared with patients with SCC (0.05<P<0.1) and a significantly higher ratio of FUT7 expression in female compared with male patients (P<0.05; Fig. S1). Additionally, a marginally higher T/N ratio of FUT6 was observed in non-smoker patients compared with smoker patients (0.05<P<0.1; Fig. S1).

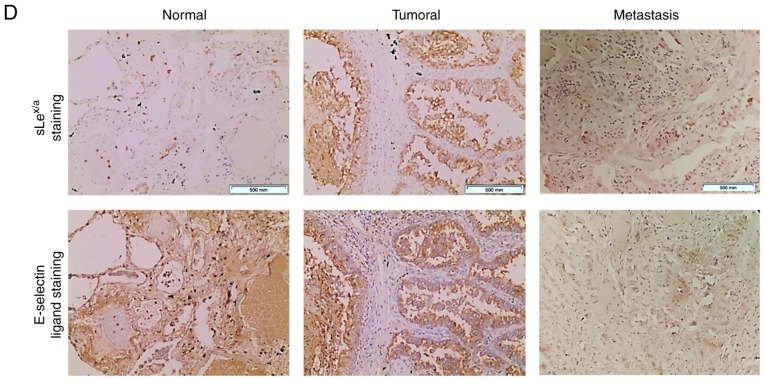

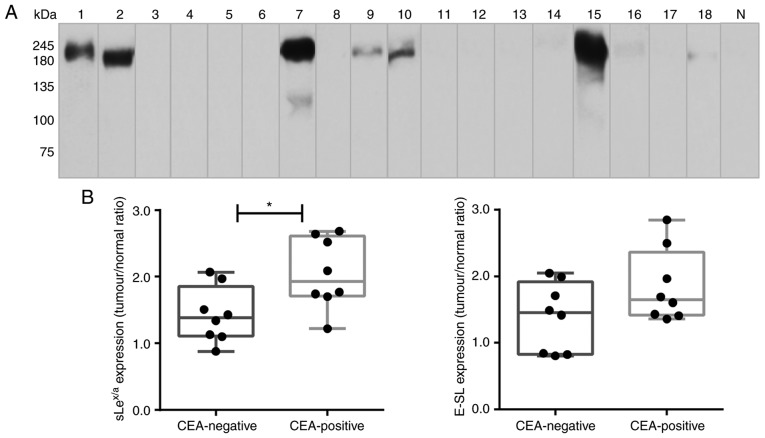

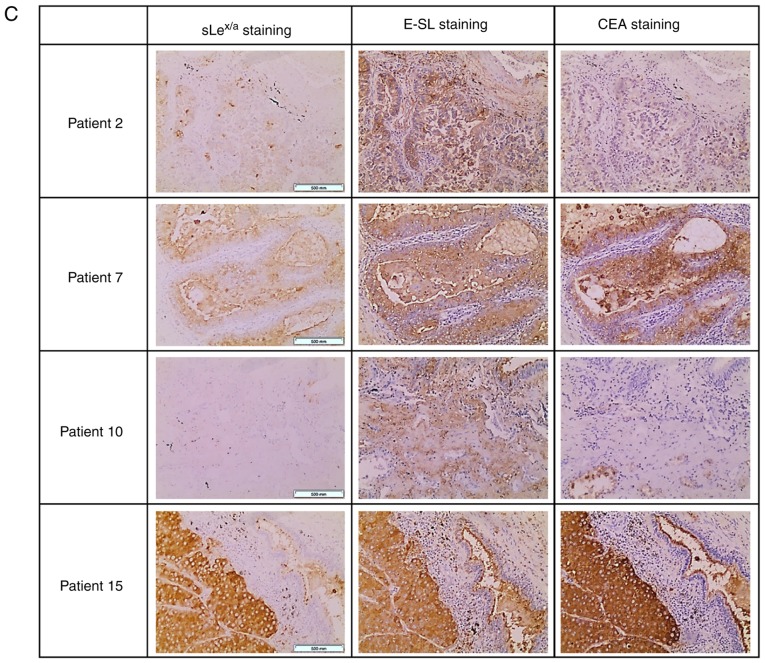

CEA is expressed in NSCLC samples with high expression of sLex/sLea glycans

CEA is a glycoprotein involved in cell adhesion, showing high levels of expression in lung cancer compared with adult normal lung tissues (35). It was hypothesised that CEA was expressed in these samples as a potential scaffold of sLex/sLea in NSCLC. Via western blot analysis, it was observed that CEA was not detectable in normal lung tissue. In contrast, it was verified that 8 out of the 18 NSCLC samples expressed CEA, presenting a characteristic band of ~180 kDa (specifically, samples 1, 2, 7, 9, 10 and 15, with weaker bands also detected in samples 16 and 18; Fig. 4A). Of note, all samples from patients with bone metastasis expressed CEA (Table SI). Comparing the CEA-negative and CEA-positive NSCLC samples, it was observed that CEA-positive samples had a significantly higher expression of sLex/sLea glycans (Fig. 4B). To investigate a potential association between CEA, sLex/sLea and E-selectin ligands, immunohistochemistry analysis was performed using five NSCLC sections from tissues which exhibited higher levels of CEA in western blotting. Paraffin-embedded sections were stained with anti-CEA mAb, anti-sLex/sLea and E-Ig chimera. Normal tissue sections showed no reactivity with anti-CEA, anti-sLex/sLea or E-Ig (IRS, 0), except for inflammatory cells, which stained with E-Ig and anti-sLex/sLea (IRS, 1-2; data not shown). In contrast, tumour sections showed general high staining for sLex/sLea (IRS, 4-9), E-selectin ligands (IRS, 6-9) and CEA (IRS, 4-9), with cytoplasmic and cell membrane localisation (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, areas showing reactivity for CEA also stained with sLex/sLea and E-Ig, suggesting co-localization of CEA and sLex/sLea in these tissues. These results suggested that CEA is a potential protein scaffold for sLex/sLea in NSCLC and has a possible role as an E-selectin ligand.

Figure 4.

CEA is expressed in patients with NSCLC. (A) Western blot analysis of CEA glycoprotein in tumour lysates. Protein (20 µg) obtained from NSCLC patients' tissues were ran in reduced SDS-PAGE gels and blotted with anti-CEA mAb. The numbers above each lane represent the patient number. The lane N corresponds to a representative normal tissue lysate from a patient with NSCLC (patient number 7), showing negative anti-CEA reactivity. This figure shows a blot with tracks from samples analysed separately. (B) sLex/sLea and E-selectin ligands expression in CEA-negative and CEA-positive patients. The tumour/normal ratios of sLex/sLea expression (left) and E-selectin ligands expression (right) were calculated and separated for CEA-negative and CEA-positive patients. Box-and-whisker plots represent median values, and upper and lower quartiles (boxes), ranges and all values for each group (black dots). *P<0.05. (C) sLex/sLea, E-selectin ligands and CEA have overlapping staining profiles in NSCLC tissues. Sequential paraffin-embedded NSCLC tissue sections from patients 2, 7, 10 and 15 were stained with HECA-452 mAb (left), E-Ig chimera (middle), and anti-CEA mAb (right) via immunohistochemistry. Nuclei were stained with haematoxylin. Magnification, ×10. CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; E-Ig, mouse E-selectin-human Fc Ig chimera; E-SL, E-selectin; mAb, monoclonal antibody; N, normal; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; sLea/x, sialyl Lewis a/x.

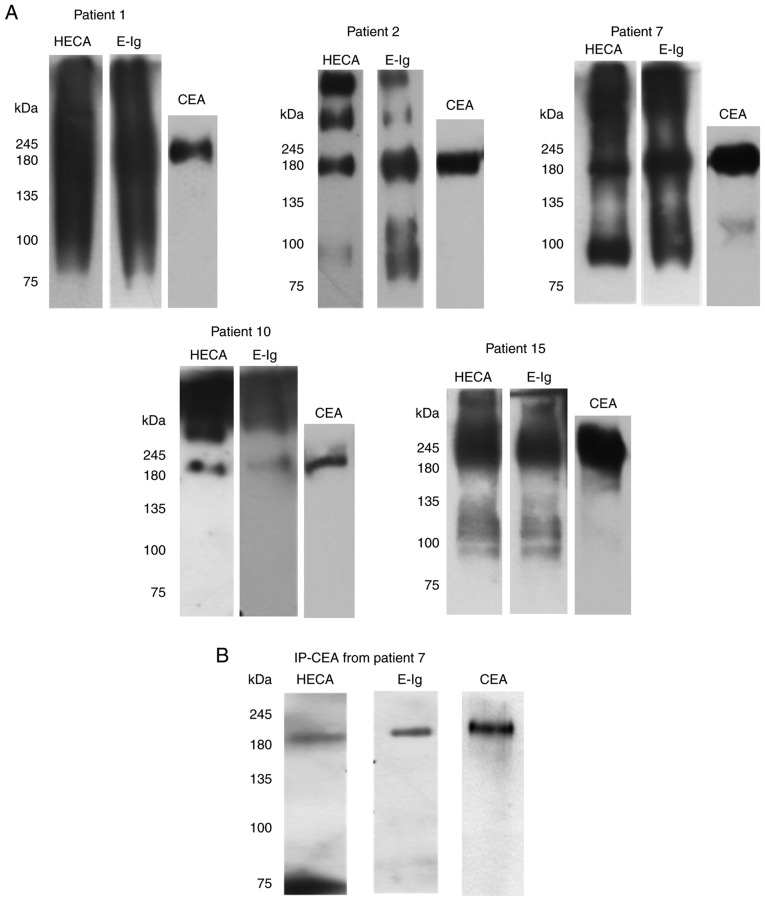

CEA is an E-selectin ligand in NSCLC tissues

To study whether CEA in NSCLC is associated with sLex/sLea and recognized by E-selectin, protein lysates from the five NSCLC tissues were electrophoresed and analysed via western blotting, using E-Ig, and anti-sLex/sLea and anti-CEA mAbs. Among the glycoproteins detected by anti-sLex/sLea mAb and E-Ig chimera, one displaying the same molecular weight as CEA (180 kDa) was present in all five tumour samples examined (Fig. 5A). Other glycoproteins reactive with anti- sLex/sLea mAb and/or E-Ig chimera of higher molecular weight (MW), such as mucins with MW >245 kDa, and lower MW have yet to be identified.

Figure 5.

CEA from NSCLC associates with sLex/sLea and has reactivity with E-selectin. (A) Western blot analysis of tumour lysates from CEA-positive NSCLC tissues. CEA-positive NSCLC tissues were resolved via SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with HECA-452 mAb, E-Ig and anti-CEA mAb. (B) Western blot analysis of immunoprecipitated CEA. CEA was immunoprecipitated from the tumour lysate of patient 7, and then resolved via SDS-PAGE and blotted. Left, HECA-452 staining; middle, E-Ig staining; right, anti-CEA mAb staining. CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; E-Ig, mouse E-selectin-human Fc Ig chimera; HECA, HECA-452; IP, immunoprecipitation; mAb, monoclonal antibody; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; sLea/x, sialyl Lewis a/x.

To further confirm that CEA reacted with E-selectin, CEA was immunoprecipitated from the protein lysates of patient 7, one of the patients with the highest CEA expression as determined by western blotting (Fig. 4A). Immunoprecipitated CEA was analysed via western blotting to verify whether this protein was stained with anti-sLex/sLea mAb and/or E-Ig chimera. As shown in Fig. 5B, immunoprecipitated CEA was recognised by both, confirming that CEA is a sLex/sLea antigens carrier and an E-selectin ligand in NSCLC.

CEA is a functional E-selectin ligand in flow conditions

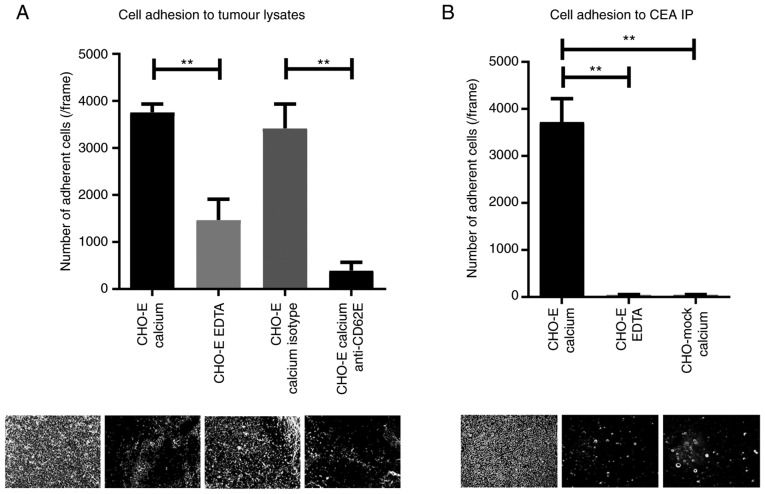

The primary role of E-selectin engagement during transendothe-lial migration is to slow down the leukocytes circulating in the bloodstream, in order to promote their adhesion to the endothelium (36). To infer the ability of NSCLC cells to bind to E-selectin in flow conditions, whether the proteins isolated from NSCLC tissue were able to support rolling interactions with cells expressing E-selectin on their surface (CHO-E cells; Fig. S2) was assessed. By using an alternative Stamper-Woodruff assay to mimic blood flow conditions (37), it was observed that the tumour proteins were able to specifically bind CHO-E cells in the presence of calcium-containing buffer (Fig. 6A). Conversely, in the presence of EDTA-containing buffer or function-blocking mAbs against E-selectin, binding to CHO-E cells was significantly reduced (Fig. 6A), indicating that this cell adhesion was mediated specifically by E-selectin interactions. E-selectin is a calcium-binding-dependent lectin, thus the requirement to use calcium-containing buffer for this assay (9). To further demonstrate that CEA protein scaffold is one of the functional E-selectin ligands in NSCLC, the ability of CEA immunoprecipitated from tumour proteins to bind to CHO-E and CHO-mock cells under flow conditions was assessed. As shown in Fig. 6B, immunoprecipitated CEA was able to bind to CHO-E cells, but not CHO-mock, and the interaction was abrogated by EDTA-containing buffer. Collectively, these data indicated that CEA expressed by NSCLC is a functional E-selectin ligand.

Figure 6.

CEA glycoprotein is a functional E-selectin ligand in NSCLC. (A) Adhesion of E-selectin-expressing cells to NSCLC lysates. Lysates of NSCLC tissue, derived from patient 7, were spotted on glass slides, and the adhesion of CHO-E cells was tested using a modified Stamper-Woodruff binding assay test. As E-selectin interactions are calcium-dependent, CHO-E cells were resuspended in calcium buffer. EDTA buffer was used as a control. Cells were pre-incubated with 20 µg/ml of specific mAbs prior to the adhesion experiment; isotype control or function-blocking anti-E-selectin mAb. (B) Adhesion of E-selectin-expressing cells to CEA immunoprecipitate. CEA was immunoprecipitated from NSCLC tissue derived from patient 7 and spotted on glass slides. Adhesion of CHO-E or CHO-mock cells to CEA IP was tested using a modified Stamper-Woodruff binding assay. CHO-E and CHO-mock cells were resus-pended in calcium buffer, and CHO-E cells resuspended in EDTA buffer were used as a negative control. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test was used for analysis. **P<0.01. Representative pictures captured for each condition (magnification, ×100) are represented below the respective graphs. CD62E, E-selectin; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CHO, Chinese hamster ovary cells; CHO-E, E-selectin-expressing CHO; CHO-mock, empty vector-transfected CHO; isotype, isotype control Ab; mAb, monoclonal antibody.

Discussion

Several studies have reported the expression of sLex/sLea glycans in NSCLC tissues and cell lines (35,38,39). The discovery of these glycans in the serum of patients soon motivated the quest to validate these as prognostic biomarkers (40). Elevated levels of sLex/sLea glycans have been associated with metastasis by several studies (39,41,42). In cell lines, their contributions to the adhesion of cancer cells to selectins expressed by vascular endothelium (43), including brain endothelium (44), have been shown. These findings highlight the potential role of sLex/sLea as E-selectin ligands contributing to the adhesion of cancer cells to endothelium and subsequent metastasis (45,46). However, little is known regarding the molecular basis of sLex/sLea expressed by the primary tissue, particularly its protein scaffold and whether they also enable the cells to establish adhesive interactions with endothelium selectins.

The present study showed that sLex/sLea glycans are significantly overexpressed in NSCLC tissues in comparison with matched normal lung tissues. These results are in agreement with previous studies showing increased expression of sLex/sLea glycans in both serum and biopsies from patients with NSCLC (14,42,47). The data also showed that NSCLC has high reactivity with E-selectin compared with normal tissue, whose intensity is correlated with anti-sLex/sLea mAb reactivity. Although sLex/sLea glycans are known as the prototypical ligands of E-selectin, their functional binding also depends on accessibility at the cell surface (48). In fact, the mere expression of the glycan ligands does not imply E-selectin binding. Therefore, this study provides the first evidence, to our knowledge, that NSCLC tissue has E-selectin reactivity.

The present study showed that increased sLex/sLea expression in NSCLC tissue was observed in patients who later developed bone metastasis. Furthermore, it was found that metastatic tissue derived from NSCLC primary tissues also expressed sLex/sLea and E-selectin ligands, which were expressed in metastasized cancer cells. In humans, bone marrow microvasculature constitutively expresses E-selectin, as well as all vascular endothelium following stimulation with inflammatory cytokines (49,50). Therefore, this observation suggested that sLex/sLea overexpression in NSCLC cells is an adaptation to enable cells to adhere to vascular E-selectins and metastasise to other locations, such as the bone. In addition to E-selectin engagement, sLex/sLea can also alter the immune homeostasis of the mucous membrane by impairing tumour cell recognition by the immune system and favouring cancer progression (51-53).

The present data also showed that the median values of FUT3, FUT6 and FUT7 mRNA expression, and the overall mean α1,3-FUT activity were higher in NSCLC tumour tissues, whereas that of FUT4 was lower and that of FUT5 was not detected. The observed FUT3, FUT6 and FUT7 gene expression profiles are consistent with previous reports showing that FUT3 is abundantly and markedly expressed in lung cancer tissues, whereas FUT6 and FUT7 are detected at lower levels but also upregulated compared with normal tissues (16,54,55). These significant alterations in the expression of FUT genes may be the underlying cause of the observed overexpression of sLex/sLea; however, to prove that altered FUT gene expression is causative of altered sLex/sLea expression, other studies will have to be performed.

sLex/sLea biosynthesis is a highly convoluted process with several glycosyltransferases involved (56). For example, sLex antigens biosynthesis is a very complex process, of which the addition of fucose is the last step. Fucosyltransferases compete with each other for similar substrates. Consistent with previous reports (54), in this study the expression of FUT4, an enzyme involved in non-sialylated Lewis biosynthesis, was found to be lower in tumour tissue. Notably, the ratios of FUT3/FUT4 and FUT7/FUT4 expression correlated with E-selectin ligand expression, highlighting the concomitant and competitive role of these enzymes in E-selectin ligand biosynthesis. Furthermore, the FUT4 T/N expression ratio enabled marginally significant evaluation of the overall survival of patients; thus, it is proposed that the relative level of FUT4 serves as a protective factor and is therefore a clinically relevant prognostic biomarker.

sLex/sLea was also identified in normal cells, but at significantly reduced levels. Nonetheless, changes in the expression of these glycans due to malignant transformation may depend not only on the expression of fucosyl- and sialyltransferases, but also on the activity of other enzymes that can lead to more complex or alternative structures (57,58). Further studies are required to fully understand the alterations of glycan biosynthesis occurring in NSCLC.

As the functional binding of sLex/sLea antigens with E-selectins is crucially dependent on their presentation by scaffold proteins (59-61), their mere detection has limited prognostic value in different cancers (62-64). Thus, the identification of sLex/sLea -decorated protein scaffolds is expected to provide more specific and reliable clinical biomarkers. While carriers of E-selectin ligands have been identified in several types of cancer, including the CD44 glycoform known as hematopoietic cell E-/L-selectin ligand in colon cancer, and CEA in colon and prostate cancer (65,66), no functionally defined E-selectin ligands were identified in NSCLC to date. Here, the data indicated that CEA decorated by sLex/sLea acts as a functionally relevant E-selectin ligand. Thus, CEA interactions with endothelial selectins may the mediate tethering, rolling and adhesion of tumour cells to the endothelium, consequently promoting cancer metastasis. CEA is a glycoprotein with low and limited expression in normal tissues, but is detected at high levels in tumours with epithelial origin, including NSCLC, gastric carcinoma and colorectal cancer, for which it is used as a tumour biomarker (67). Serum CEA in patients with NSCLC correlates with advanced stage of the disease, poor therapeutic response, early relapse and shorter survival (35,68). Notably, besides cell adhesion, CEA also serves key functions in intracellular and intercellular signalling involved in cancer progression, inflammation, angiogenesis and metastasis (69). Thus, CEA-E-selectin interactions may also contribute to these malignant features. Although CEA and sLex/sLea have been extensively suggested as clinical biomarkers in NSCLC (12,70,71), to our knowledge, this is the first study addressing the functional relevance of sLex/sLea-associated CEA as an E-selectin ligand in primary NSCLC tissue.

Unlike other reports that used cell lines, the present findings were obtained in primary NSCLC and paired non-tumour pulmonary tissues. The use of primary tissue offers undeniably greater relevance to the findings, as it reflects the in vivo NSCLC microenvironment. Yet, the use of primary tissue posed limitations on sample quantity and sample size that affected reproducibility, and requires validation in larger cohorts. The expression of E-selectin ligands in lung tissue derived from healthy subjects also remains to be established. A further limitation of the present study was the use of normal pulmonary tissues derived from patients with NSCLC. Non-cancerous tissues surrounding the tumour is a common control for these types of studies; however, it can be affected by the presence of infiltrating cancer cells or the so-called ‘field effect' of tumour growth (72,73).

Overall, the present findings indicated that sLex/sLea and E-selectin ligands are overexpressed in NSCLC tissue compared with adjacent control tissue, alongside increased a1,3-FUT activity and fucosyltransferase transcript expression. The highest sLex/sLea levels were detected in the primary tissues of patients with bone metastasis, hinting that these antigens may promote metastasis to this site. Furthermore, the presence of sLex/sLea and E-selectin ligands on CEA suggests that mechanistically, CEA may facilitate adhesion to endothelium selectins and consequently promote cancer metastasis. This study also pinpoints the usefulness of sLex/sLea-modified CEA as a potential therapeutic target and diagnostic biomarker in NSCLC, a finding that requires validation in future studies.

Supplementary Data

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge both Dr Analisa Ribeiro and Dr Madalena Ramos (Pathology service, Hospital Pulido Valente) for their assessment of immunohistochemistry samples, and Dr Francisco Félix, Dr Paulo Calvinho, Dr Cristina Rodrigues and nurses (Thoracic service, Hospital Pulido Valente) for their involvement in the collection of lung tissue samples. We also thank Ms Ana Raquel Henriques (technician from the Pathology service, Faculty of Medicine, University of Lisbon) for providing paraffin-embedded sections of lung tissues samples.

Abbreviations

- AC

adenocarcinoma

- CEA

carcinoembryonic antigen

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- SCC

squamous cell carcinoma

- sLex

sialyl Lewis x

- sLea

sialyl Lewis a

Funding

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the LPCC/Pfizer 2011, and Tagus TANK award 2018 (grant no. 1/2018) from Universidade Nova de Lisboa and José de Mello Saúde. Additionally, scholarship funding was provided by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) [grant nos. SFRH/BD/100970/2014 and SFRH/BPD/108686/2015].

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

The study was conceived by PV, who designed and supervised all research and drafted the manuscript. IGF and MC contributed equally to the work in designing and performing the experiments, collecting and analysing data, and drafting the manuscript. AGM performed experiments, prepared results and drafted the manuscript. AB collected patient samples and conceived experiments. PB designed and interpreted immunohistochemistry data. ZS performed experiments and drafted the manuscript, and FDO analysed data and drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Norte. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Youlden DR, Cramb SM, Baade PD. The international epidemiology of lung cancer: Geographical distribution and secular trends. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:819–831. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31818020eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riihimäki M, Hemminki A, Fallah M, Thomsen H, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Hemminki K. Metastatic sites and survival in lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2014;86:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamura T, Kurishima K, Nakazawa K, Kagohashi K, Ishikawa H, Satoh H, Hizawa N. Specific organ metastases and survival in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Mol Clin Oncol. 2015;3:217–221. doi: 10.3892/mco.2014.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishida N, Yano H, Nishida T, Kamura T, Kojiro M. Angiogenesis in cancer. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2006;2:213–219. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.2006.2.3.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noman MZ, Messai Y, Muret J, Hasmim M, Chouaib S. Crosstalk between CTC, immune system and hypoxic tumor microenvironment. Cancer Microenviron. 2014;7:153–160. doi: 10.1007/s12307-014-0157-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Popper HH. Progression and metastasis of lung cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016;35:75–91. doi: 10.1007/s10555-016-9618-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gout S, Tremblay PL, Huot J. Selectins and selectin ligands in extravasation of cancer cells and organ selectivity of metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2008;25:335–344. doi: 10.1007/s10585-007-9096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding D, Yao Y, Zhang S, Su C, Zhang Y. C-type lectins facilitate tumor metastasis. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:13–21. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.5431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barthel SR, Gavino JD, Descheny L, Dimitroff CJ. Targeting selectins and selectin ligands in inflammation and cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2007;11:1473–1491. doi: 10.1517/14728222.11.11.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogawa J, Sano A, Inoue H, Koide S. Expression of Lewis-related antigen and prognosis in stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;59:412–415. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)00866-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mizuguchi S, Nishiyama N, Iwata T, Nishida T, Izumi N, Tsukioka T, Inoue K, Kameyama M, Suehiro S. Clinical value of serum cytokeratin 19 fragment and sialyl-Lewis X in non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Komatsu H, Mizuguchi S, Izumi N, Chung K, Hanada S, Inoue H, Suehiro S, Nishiyama N. Sialyl Lewis X as a predictor of skip N2 metastasis in clinical stage IA non-small cell lung cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:309. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-11-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Satoh H, Ishikawa H, Kamma H, Yamashita YT, Takahashi H, Ohtsuka M, Hasegawa S. Elevated serum sialyl Lewis X-i antigen levels in non-small cell lung cancer with lung metastasis. Respiration. 1998;65:295–298. doi: 10.1159/000029279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomes C, Osório H, Pinto MT, Campos D, Oliveira MJ, Reis CA. Expression of ST3GAL4 leads to SLe(x) expression and induces c-Met activation and an invasive phenotype in gastric carcinoma cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66737. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dall'Olio F, Malagolini N, Trinchera M, Chiricolo M. Sialosignaling: Sialyltransferases as engines of self-fueling loops in cancer progression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1840:2752–2764. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dall'Olio F, Malagolini N, Trinchera M, Chiricolo M. Mechanisms of cancer-associated glycosylation changes. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2012;17:670–699. doi: 10.2741/3951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sperandio M. Selectins and glycosyltransferases in leukocyte rolling in vivo. FEBS J. 2006;273:4377–4389. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakayama F, Nishihara S, Iwasaki H, Kudo T, Okubo R, Kaneko M, Nakamura M, Karube M, Sasaki K, Narimatsu H. CD15 expression in mature granulocytes is determined by α1,3-fucosyltransferase IX, but in promyelocytes and monocytes by α1,3-fucosyltransferase IV. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16100–16106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007272200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian L, Shen D, Li X, Shan X, Wang X, Yan Q, Liu J. Ginsenoside Rg3 inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and invasion of lung cancer by down-regulating FUT4. Oncotarget. 2016;7:1619–1632. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brierley JD, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C, editors. TNM classification of malignant tumours. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo C, Liu S, Sun MZ. Novel insight into the role of GAPDH playing in tumor. Clin Transl Oncol. 2013;15:167–172. doi: 10.1007/s12094-012-0924-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo C, Liu S, Wang J, Sun MZ, Greenaway FT. ACTB in cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;417:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cucchiarelli V, Hiser L, Smith H, Frankfurter A, Spano A, Correia JJ, Lobert S. β-tubulin isotype classes II and V expression patterns in nonsmall cell lung carcinomas. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2008;65:675–685. doi: 10.1002/cm.20297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Videira PA, Correia M, Malagolini N, Crespo HJ, Ligeiro D, Calais FM, Trindade H, Dall'Olio F. ST3Gal.I sialyltransferase relevance in bladder cancer tissues and cell lines. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:357. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carrascal MA, Severino PF, Guadalupe Cabral M, Silva M, Ferreira JA, Calais F, Quinto H, Pen C, Ligeiro D, Santos LL, et al. Sialyl Tn-expressing bladder cancer cells induce a tolerogenic phenotype in innate and adaptive immune cells. Mol Oncol. 2014;8:753–765. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, et al. The MIQE Guidelines: Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments. Clin Chem. 2009;55:611–622. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trinchera M, Zulueta A, Caretti A, Dall'Olio F. Control of glycosylation-related genes by DNA methylation: The intriguing case of the B3GALT5 gene and its distinct promoters. Biology (Basel) 2014;3:484–497. doi: 10.3390/biology3030484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dimitroff CJ, Lee JY, Rafii S, Fuhlbrigge RC, Sackstein R. CD44 is a major E-selectin ligand on human hematopoietic progenitor cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:1277–1286. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.6.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oxley SM, Sackstein R. Detection of an L-selectin ligand on a hematopoietic progenitor cell line. Blood. 1994;84:3299–3306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dimitroff CJ, Lee JY, Schor KS, Sandmaier BM, Sackstein R. Differential L-selectin binding activities of human hematopoietic cell L-selectin ligands, HCELL and PSGL-1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47623–47631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105997200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carrascal MA, Talina C, Borralho P, Gonçalo Mineiro A, Henriques AR, Pen C, Martins M, Braga S, Sackstein R, Videira PA. Staining of E-selectin ligands on paraffin-embedded sections of tumor tissue. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:495. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4410-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin F, Prichard J. In: Handbook of Practical Immunohistochemistry. 2nd edition. Lin F, Prichard J, editors. Springer; New York, NY: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grunnet M, Sorensen JB. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) as tumor marker in lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2011;76:138–143. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McEver RP. Selectins: Initiators of leucocyte adhesion and signalling at the vascular wall. Cardiovasc Res. 2015;107:331–339. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dimitroff CJ, Kupper TS, Sackstein R. Prevention of leukocyte migration to inflamed skin with a novel fluorosugar modifier of cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1008–1018. doi: 10.1172/JCI19220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holmes EH, Ostrander GK, Hakomori S. Biosynthesis of the sialyl-Lex determinant carried by type 2 chain glycosphin-golipids (IV3NeuAcIII3FucnLc4, VI3NeuAcV3FucnLc6, and VI3NeuAcIII3V3Fuc2nLc6) in human lung carcinoma PC9 cells. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:3737–3743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shimizu T, Yonezawa S, Tanaka S, Sato E. Expression of Lewis X-related antigens in adenocarcinomas of lung. Histopathology. 1993;22:549–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1993.tb00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shimizu S, Suzuki H, Noguchi E. Sialyl Lewis X-i (SLX) in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with lung cancer. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;30:815–820. In Japanese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mizuguchi S, Inoue K, Iwata T, Nishida T, Izumi N, Tsukioka T, Nishiyama N, Uenishi T, Suehiro S. High serum concentrations of sialyl lewisx predict multilevel N2 disease in non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:1010–1018. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fukuoka K, Narita N, Saijo N. Increased expression of sialyl Lewis (x) antigen is associated with distant metastasis in lung cancer patients: Immunohistochemical study on bronchofiber-scopic biopsy specimens. Lung Cancer. 1998;20:109–116. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5002(98)00016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takada A, Ohmori K, Yoneda T, Tsuyuoka K, Hasegawa A, Kiso M, Kannagi R. Contribution of carbohydrate antigens sialyl Lewis A and sialyl Lewis X to adhesion of human cancer cells to vascular endothelium. Cancer Res. 1993;53:354–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jassam SA, Maherally Z, Smith JR, Ashkan K, Roncaroli F, Fillmore H, Pilkington GJ. CD15s/CD62E interaction mediates the adhesion of non-small cell lung cancer cells on brain endothelial cells: Implications for cerebral metastasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:E1474. doi: 10.3390/ijms18071474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bendas G, Borsig L. Cancer cell adhesion and metastasis: Selectins, integrins, and the inhibitory potential of heparins. Int J Cell Biol. 2012;2012:676731. doi: 10.1155/2012/676731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Witz IP. The selectin-selectin ligand axis in tumor progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27:19–30. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9101-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Satoh H, Ishikawa H, Yamashita YT, Ohtsuka M, Sekizawa K. Serum sialyl Lewis X-i antigen in lung adenocarcinoma and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax. 2002;57:263–266. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.3.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trinchera M, Aronica A, Dall'Olio F. Selectin ligands sialyllewis a and sialyl-Lewis X in gastrointestinal cancers. Biology (Basel) 2017;6:E16. doi: 10.3390/biology6010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schweitzer KM, Dräger AM, van der Valk P, Thijsen SF, Zevenbergen A, Theijsmeijer AP, van der Schoot CE, Langenhuijsen MM. Constitutive expression of E-selectin and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 on endothelial cells of hematopoietic tissues. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:165–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weninger W, Ulfman LH, Cheng G, Souchkova N, Quackenbush EJ, Lowe JB, von Andrian UH. Specialized contributions by alpha(1,3)-fucosyltransferase-IV and FucT-VII during leukocyte rolling in dermal microvessels. Immunity. 2000;12:665–676. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kannagi R, Sakuma K, Miyazaki K, Lim KT, Yusa A, Yin J, Izawa M. Altered expression of glycan genes in cancers induced by epigenetic silencing and tumor hypoxia: Clues in the ongoing search for new tumor markers. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:586–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chachadi VB, Bhat G, Cheng PW. Glycosyltransferases involved in the synthesis of MUC-associated metastasis-promoting selectin ligands. Glycobiology. 2015;25:963–975. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwv030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshihama N, Yamaguchi K, Chigita S, Mine M, Abe M, Ishii K, Kobayashi Y, Akimoto N, Mori Y, Sugiura T. A novel function of CD82/KAI1 in sialyl Lewis antigen-mediated adhesion of cancer cells: Evidence for an anti-metastasis effect by down-regulation of sialyl Lewis antigens. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124743. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Togayachi A, Kudo T, Ikehara Y, Iwasaki H, Nishihara S, Andoh T, Higashiyama M, Kodama K, Nakamori S, Narimatsu H. Up-regulation of Lewis enzyme (Fuc-TIII) and plasma-type alpha1,3fucosyltransferase (Fuc-TVI) expression determines the augmented expression of sialyl Lewis x antigen in non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 1999;83:70–79. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990924)83:1<70::AID-IJC14>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barthel SR, Wiese GK, Cho J, Opperman MJ, Hays DL, Siddiqui J, Pienta KJ, Furie B, Dimitroff CJ. Alpha 1,3 fucosyltransferases are master regulators of prostate cancer cell trafficking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:19491–19496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906074106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kannagi R, Yin J, Miyazaki K, Izawa M. Current relevance of incomplete synthesis and neo-synthesis for cancer-associated alteration of carbohydrate determinants-Hakomori's concepts revisited. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1780:525–531. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Malagolini N, Santini D, Chiricolo M, Dall'Olio F. Biosynthesis and expression of the Sda and sialyl Lewis x antigens in normal and cancer colon. Glycobiology. 2007;17:688–697. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwm040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Groux-Degroote S, Wavelet C, Krzewinski-Recchi MA, Portier L, Mortuaire M, Mihalache A, Trinchera M, Delannoy P, Malagolini N, Chiricolo M, et al. B4GALNT2 gene expression controls the biosynthesis of Sda and sialyl Lewis X antigens in healthy and cancer human gastrointestinal tract. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;53:442–449. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shinagawa T, Hoshino H, Taga M, Sakai Y, Imamura Y, Yokoyama O, Kobayashi M. Clinicopathological implications to micropapillary bladder urothelial carcinoma of the presence of sialyl Lewis X-decorated mucin 1 in stromafacing membranes. Urol Oncol. 2017;35:606.e17–606.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Burdick MM, Chu JT, Godar S, Sackstein R. HCELL is the major E- and L-selectin ligand expressed on LS174T colon carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13899–13905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513617200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Woodman N, Pinder SE, Tajadura V, Le Bourhis X, Gillett C, Delannoy P, Burchell JM, Julien S. Two E-selectin ligands, BST-2 and LGALS3BP, predict metastasis and poor survival of ER-negative breast cancer. Int J Oncol. 2016;49:265–275. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2016.3521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sackstein R. The lymphocyte homing receptors: Gatekeepers of the multistep paradigm. Curr Opin Hematol. 2005;12:444–450. doi: 10.1097/01.moh.0000177827.78280.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hidalgo A, Peired AJ, Wild M, Vestweber D, Frenette PS. Complete identification of E-selectin ligands on neutrophils reveals distinct functions of PSGL-1, ESL-1, and CD44. Immunity. 2007;26:477–489. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mitoma J, Miyazaki T, Sutton-Smith M, Suzuki M, Saito H, Yeh JC, Kawano T, Hindsgaul O, Seeberger PH, Panico M, et al. The N-glycolyl form of mouse sialyl Lewis X is recognized by selectins but not by HECA-452 and FH6 antibodies that were raised against human cells. Glycoconj J. 2009;26:511–523. doi: 10.1007/s10719-008-9207-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thomas SN, Zhu F, Schnaar RL, Alves CS, Konstantopoulos K. Carcinoembryonic antigen and CD44 variant isoforms cooperate to mediate colon carcinoma cell adhesion to E- and L-selectin in shear flow. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15647–15655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800543200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burdick MM, Henson KA, Delgadillo LF, Choi YE, Goetz DJ, Tees DF, Benencia F. Expression of E-selectin ligands on circulating tumor cells: Cross-regulation with cancer stem cell regulatory pathways? Front Oncol. 2012;2:103. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Duffy MJ. Carcinoembryonic antigen as a marker for colorectal cancer: Is it clinically useful? Clin Chem. 2001;47:624–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang J, Ma Y, Zhu ZH, Situ DR, Hu Y, Rong TH. Expression and prognostic relevance of tumor carcinoembryonic antigen in stage IB non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2012;4:490–496. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2012.09.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Beauchemin N, Arabzadeh A. Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecules (CEACAMs) in cancer progression and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2013;32:643–671. doi: 10.1007/s10555-013-9444-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Holdenrieder S, Wehnl B, Hettwer K, Simon K, Uhlig S, Dayyani F. Carcinoembryonic antigen and cytokeratin-19 fragments for assessment of therapy response in non-small cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2017;116:1037–1045. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li X, Asmitananda T, Gao L, Gai D, Song Z, Zhang Y, Ren H, Yang T, Chen T, Chen M. Biomarkers in the lung cancer diagnosis: A clinical perspective. Neoplasma. 2012;59:500–507. doi: 10.4149/neo_2012_064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kadara H, Wistuba II. Field cancerization in non-small cell lung cancer: Implications in disease pathogenesis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2012;9:38–42. doi: 10.1513/pats.201201-004MS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lochhead P, Chan AT, Nishihara R, Fuchs CS, Beck AH, Giovannucci E, Ogino S. Etiologic field effect: Reappraisal of the field effect concept in cancer predisposition and progression. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:14–29. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.