Abstract

Angelicin is an active compound isolated from the Chinese herb Angelica archangelica, which has been reported to exert antitumor effects by inhibiting malignant behaviors in several types of tumor, including proliferation, colony formation, migration and invasion. However, the effects of angelicin on human cervical cancer cells is yet to be elucidated. The present study evaluated the antitumor effects of angelicin on cervical cancer cells. The results demonstrated that cervical cancer cells were more sensitive to angelicin than cervical epithelial cells. At its IC30, angelicin inhibited the proliferation of HeLa and SiHa cells by blocking the cell cycle at the G1/G0 phase and inhibiting other malignant behaviors, including colony formation, tumor formation in soft agar, migration and invasion. At the IC50, angelicin induced cell death potentially by promoting apoptosis. By identifying the hallmarks of autophagy, it was observed that angelicin treatment caused the accumulation of microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3-β (LC3B) in the cytoplasm of HeLa and SiHa cells. Western blotting results demonstrated that cleaved LC3B-II and autophagy related proteins (Atg)3, Atg7 and Atg12-5 were upregulated following angelicin treatment. It was also determined that the phosphorylation of mTOR was induced by angelicin treatment. Furthermore, the inhibition of angelicin-induced mTOR phosphorylation did not disrupt its inhibitory effect on autophagy, indicating that angelicin inhibited autophagy in an mTOR-independent manner. Taken together, the present results suggested that angelicin regulated malignant behaviors in cervical cancer cells by inhibiting autophagy in an mTOR-independent manner. Findings suggested that autophagy might be a potential therapeutic target for cervical cancer.

Keywords: angelicin, cervical cancer, mTOR, autophagy, malignant behaviors

Introduction

In less developed countries, cervical cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer, with a high mortality rate (1). Early stage patients [International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stages I–IIA] may experience favourable outcomes by undergoing radical surgery or radiotherapy, as indicated by an overall 5-year survival rate of >65% (2,3). However, patients with later-stage disease, including stage IIB-IV, require more severe therapeutic strategies, including radiotherapy in addition to chemotherapy. The 5-year survival rate for patients with stage IIB-III cancer is 25–30% (2,3). For stage IV cancer, the survival rate is <15% (2,3) due to chemoresistance resulting in local recurrence or distant metastasis. Presently, chemotherapy is clinically employed as one of the most efficient strategies in the systematic treatment of cervical cancer. A combination of cisplatin with other chemotherapeutic drugs has remained the dominant systemic therapeutic modality for locally advanced and metastatic cervical cancer for several decades (4). However, chemoresistance limits the therapeutic effect of these chemoagent and frequently results in poor prognosis. Therefore, there is an urgent need for novel chemotherapeutic agents for use alone or in combination with a primary chemotherapeutic agent.

The natural molecule angelicin, 2-oxo-(2H)-furo(2,3-h)-1-benzopyran, is one of the major active compounds isolated from the traditional Chinese herb Angelica archangelica. For decades, angelicin has been clinically used to exert therapeutic effects on various skin diseases, such as lichen planus, acting as a photosensitizer (5,6). Angelicin exertsgenotoxic effects and thus induces cytotoxicity in several types of tumour and non-tumour cells (7,8). Mira and Shimizu (9) identified that angelicin causes cytotoxicity by inhibiting tubulin polymerization and histone deacetylase 8 activity in several types of tumour cells, including human hepatocellular carcinoma, rhabdomyosarcoma and colorectal carcinoma (9). To investigate the potential mechanism for proliferation inhibition, Wang et al (10) used liver cancer for therapeutic research both in vitro and in vivo. The study determined that the dose- and time-dependent apoptotic effect of angelicin is caused by the regulation of mitochondria, involving the P13K/AKT1 signalling pathway. Accordingly, angelicin affects physiological processes in both tumour and non-tumour cells.

Autophagy is a highly conserved multi-step lysosomal degradation process. Cellular components are sequestered in autophagosomes that subsequently fuse with lysosomes to degrade the contents (11). Accumulating evidence has established a close association between autophagy and tumour progression, with autophagy having different functions during tumour progression, including tumour suppression and enhancement (5,6,12). Tsai et al (5) reported that the natural agent 1-(2-hydroxy-5-methylphenyl)-3-phenyl-1,3-propanedione, exerts growth-inhibiting effects by promoting the autophagy of HeLa cervical cancer cells. Li et al (6) determined that protein kinase C-β inhibited autophagy and consequently sensitized HeLa cells to chemotherapy. The study also reported that an increase in autophagy inhibited cell growth and induced apoptotic cell death (12). The dynamic role of autophagy in tumour progression has been the focus of research for potential therapeutics. However, further studies into strategies for controlling autophagy are required to increase understanding into the association between autophagy and tumour progression.

The growth-inhibiting and apoptosis-promoting effects of angelicin in several types of cancers have been previously reported (13). However, whether cervical cancer is chemosensitive to angelicin has not been demonstrated. Therefore, the present study used the human cervical carcinoma cell line, HeLa and the human cervical squamous cell carcinoma cell line, SiHa as in vitro models to determine the anticancer effects of angelicin. To evaluate its specific activity on cervical cancer cells, the non-tumour cervical epithelial cell line ECT1/E6E7 was also employed. The investigation primarily focused on the regulation of malignant behaviours by inducing or inhibiting autophagy in HeLa and SiHa. In addition, the effects of angelicin on autophagy and the potentially relevant mTOR signalling pathway were explored. The results of the present study may reveal the novel effects of angelicin as a chemotherapeutic strategy in certain types of cervical carcinomas.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

The human cervical carcinoma cell line, HeLa and the cervical squamous cell carcinoma cell line, SiHa was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (accession no. HTB-35). The cervical epithelial cell line, ECT1/E6E7 was purchased from Jennio Biotech Co., Ltd. and used for identifying the difference of chemosensitivity between cancer cell lines and a non-tumor cell line. All cells were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator in DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 100 U/ml penicillin and 10% FBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Cells were passaged every 3 days.

For identifying chemosensitivity, 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 120, 140, 160, 180 or 200 µM angelicin (cat. no. A0956-10MG; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was added to the medium of HeLa or SiHa for 24 h. For 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (Edu) staining, cell cycle distribution, colony formation, tumor formation in soft agar, migration and invasion assays, the IC30 of angelicin (27.8 µM) was employed to evaluate the effects of angelicin on malignant behaviors. For carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)/propidium iodide (PI) or Annexin V FITC/PI double staining, the IC50 of angelicin was employed. For inhibiting the degradation of microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3-β (LC3B)-II, cells were pretreated with 10 µM of chloroquine (cat. no. C6628; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 6 h. For rapamycin (cat. no. V900930; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) pretreatment, cells were pretreated with 1 µM of rapamycin for 6 h. Mock group containing vehicle only was considered as negative control in all the experiments.

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

To determine HeLa or SiHa cell viability, 5×103 cells were plated in 96-well plates. The aforementioned treatment was administered and 10 µl tetrazolium salt WST-8 (KeyGen Biotech. Co. Ltd.) was added to each well for a 4 h incubation at 37°C. Optical density (OD) was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm using a microplate reader (Synergy 2 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader; BioTek Instruments, Inc.).

EdU staining

HeLa or SiHa cells were seeded at a density of 2×105 cells per well in 6-well plates supplemented with DMEM containing 50 µM EdU (RiboBio Co. Ltd.). Following 2 h incubation at room temperature, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. EdU immunostaining was performed with Apollo staining reaction buffer followed by nuclei staining with Hoechst 33342 (cat. no. B2261; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) at final concentration of 10 µg/ml at room temperature for 10 min. Stained cells were imaged under a X71 (U-RFL-T) fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation; magnification, ×40).

PI staining

HeLa or SiHa cells were dissociated using 0.25% trypsin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and three time washed with PBS. Following the last wash, the cell pellet, which was centrifuged at 400 × g for 10 min at room temperature, was suspended and fixed in 70% ice-cold alcohol overnight at 4°C. Cells were then washed in triplicate with ice-cold PBS and suspended in 400 µl PI solution (5 µg/ml) for 30 min in the dark. Apoptotic cells were analyzed via flow cytometry using a 3 laser Navios flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc.) and analyzed using FlowJo software (FlowJo LLC; version 9).

Colony formation

HeLa or SiHa cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1,000 cells/well. Cells were then cultured at 37°C for 10 days until visible colonies appeared. Colonies were stained with 500 µl Giemsa solution (Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd.) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Colonies were then imaged using a X71 (U-RFL-T) fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation; magnification, ×40).

Tumor formation in soft agar

To assess tumor formation in vitro, soft agar clonogenic assays were performed. Each well of a 6-well plate was coated with 2 ml of 0.5% (w/v) low-melting agar (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) in DMEM with 10% FBS. Cells were mixed and 5×103 cells in 2 ml 0.3% low-melting agar with 10% FBS were added above the polymerized base solution. Plates were incubated (37°C; 5% CO2) for 14 days before colony number and diameter were quantified microscopically using a X71 (U-RFL-T) fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation; magnification, ×40).

Scratch wound healing assay

HeLa or SiHa cells were seeded at a density of 1×106 in 6-well plates and allowed to attach for 24 h. When cell confluence reached ~100%, a scratch wound was subsequently introduced by scraping the cell monolayer with a 10 µl sterile micropipette tip. Cells were then washed with PBS to remove unattached cells and incubated at 37°C for 24 h in medium containing 1% FBS. Cells were then imaged at the same site at 0 and 24 h following induction of the scratch using a X71 (U-RFL-T) fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation; magnification, ×40).

Transwell invasion assay

HeLa or SiHa cells were dissociated with 0.25% trypsin and washed three times with ice-cold PBS. In the lower chamber, 500 µl of DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS was added. A total of 200 µl of cells at the concentration of 2×105/ml were seeded into the top chamber of transwell inserts containing 8 µM pore polycarbonate filters (Corning Inc.) that had been precoated with Matrigel for 2 h at room temperature (BD Biosciences). The plate was incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Following 24 h of incubation, the cells on the upper membrane were removed and the invaded cells were stained with 0.25% crystal violet (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) at room temperature for 10 min then counted using a X71 (U-RFL-T) fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation; magnification, ×40).

CFSE/PI double staining

A total of 1×106 HeLa or SiHa cells were seeded in 6-well plates and allowed to attach overnight. Then 100 µl of CFSE fluorescent dye (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was added and incubated at 37°C for 15 min. Supernatant was removed and cells were washed with DMEM without FBS. Following the aforementioned treatments, cells were incubated with PI to a final concentration of 5 µg/ml at room temperature for 10 min. Cells were imaged using a X71 (U-RFL-T) fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation; magnification, ×40).

Annexin V/PI double staining

HeLa or SiHa cells were dissociated using 0.25% Trypsin and washed three times with ice-cold PBS. Following the last wash, cells were suspended in PBS and the cell concentration was adjusted to 1×106 cells/ml. Cells were simultaneously stained with Annexin V-FITC (green fluorescence) and PI (red fluorescence), which allowed for the identification of intact cells (FITC−/PI−), early apoptotic cells (FITC+/PI−) and late apoptotic cells (FITC+/PI+). Samples were analyzed using the FACS LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) with FlowJo software (FlowJo LLC; version 9).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

HeLa or SiHa cells were plated in 6-well plates on coverslips and allowed to attach for 24 h. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 10 min at room temperature. Normal goat serum (5%; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) in PBS was used for unspecific blocking at room temperature for 30 min. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies against LC3B (1:2,000; cat. no. ab48394; Abcam) at room temperature for 2 h. Cells were then rinsed four times with PBS-Tween 20 and incubated with secondary antibodies produced in rabbit (1:500 in 0.5% normal goat serum) conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 for 1 h at room temperature. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) at room temperature for 10 min. Images were captured with a X71 (U-RFL-T) fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation) at a magnification of ×200.

Western blot analysis

Following the aforementioned treatments, HeLa or SiHa cells were lysed in chilled lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM NaF and 10 µM PMSF on ice for 10 min. Supernatants were collected via centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The extracted protein concentration was measured using Bicinochoninic Acid kit (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for Protein Determination according to the manufacturer's protocol. For each sample, 20 µg of total protein was loaded per lane and separated via SDS-PAGE on a 12.5% gel, then transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (EMD Millipore) followed by blocking using 5% BSA (Sigma–Aldrich; Merck KGaA). The membrane was subsequently incubated with the following primary antibodies at a dilution of 1:1,000 overnight at 4°C: Rabbit anti-LC3B (cat. no. ab48394; Abcam), rabbit anti-β-actin (cat. no. ab8227; Abcam), rabbit anti-autophagy related protein (Atg)-3 (cat. no. ab108251; Abcam), rabbit anti-Atg7 (cat. no. ab133528; Abcam), rabbit anti-β-actin (cat. no. ab8227; Abcam), rabbit anti-Atg12-Atg5 (cat. no. orb375397; Biorbyt Ltd.), rabbit anti-mTOR (cat. no. ab2732; Abcam) and rabbit anti-mTOR (phospho S2448, cat. no. ab109268, Abcam). Membranes were subsequently incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L antibody; cat. no. ab7090; 1:5,000; Abcam) for 2 h at room temperature. Enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (cat. no. PRN2232; GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences) were used to visualize protein bands.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS, Inc.). Data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. All experiments were repeated three times, independently. Comparisons between groups were assessed using a Student's t-test for two groups and one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni post hoc analysis for multiple groups. P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

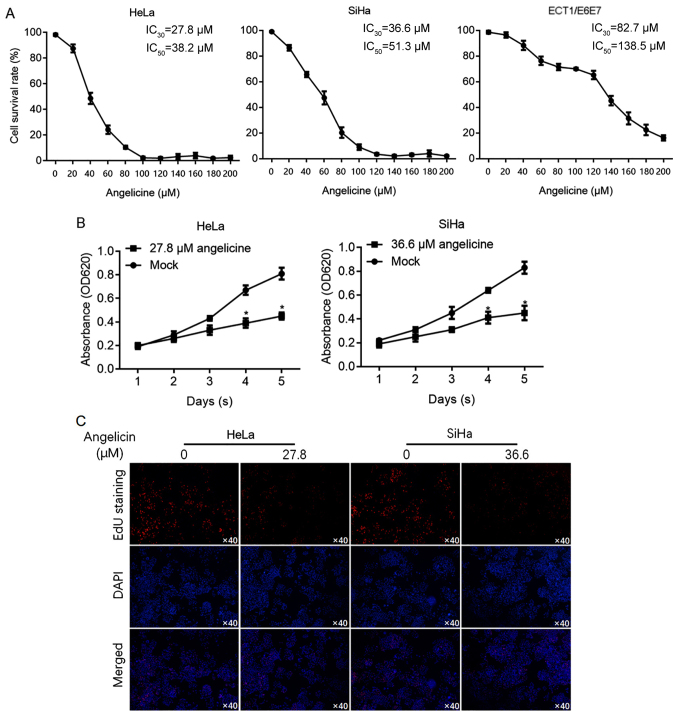

Cervical cancer cells are more sensitive to angelicin than cervical epithelial cells

It has been reported that angelicin is cytotoxic to hepatic cancer cells (10). To investigate the effects of angelicin in cervical cancer cells (HeLa and SiHa), cell viability was determined using CCK-8 assay following exposure to a range of angelicin concentrations for 24 h. For comparison, the sensitivity of cervical epithelial cells (ECT1/E6E7) to angelicin was also measured to evaluate the 30% inhibitory concentration (IC30) and 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50). The results revealed that HeLa (IC30, 27.8 µM; IC50, 38.2 µM) and SiHa (IC30, 36.6 µM; IC50, 51.3 µM) cells were more sensitive to angelicin than ECT1/E6E7 cells (IC30, 82.7 µM; IC50, 138.5 µM; Fig. 1A). Cell viability was assessed on days 1–5 following treatment with angelicin at the IC30. The results revealed that Angelicin treatment significantly inhibited HeLa and SiHa cell proliferation (P<0.05 vs. mock group containing vehicle only; Fig. 1B). To confirm that the decrease in cell viability was due to a change in cell proliferation, EdU labelling of proliferating cells was performed. The results revealed that HeLa and SiHa cell treatment with angelicin at the IC30 substantially decreased the number of proliferating cells compared with the control (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

HeLa and SiHa cervical cancer cells were sensitive to angelicin treatment, whereas ECT1/E6E7 cervical epithelial cells were not. (A) Cell survival rate was measured by performing a cell counting kit-8 assay following angelicin treatment with indicated concentrations for 24 h. The 30% inhibitory concentration (IC30) and 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) were calculated accordingly. (B) Cell viability was measured following angelicin treatment at the IC30 from day 1 to 5. (C) EdU staining was performed to specifically label proliferating cells where blue staining represents cell nuclei and red staining represents proliferating cells. *P<0.05 vs. the mock group. Edu, 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine; OD, optical density.

Angelicin treatment inhibits the migration and invasion of cervical cancer cells

To determine whether angelicin inhibited cell proliferation by regulating cell cycle phase distribution, flow cytometry of PI-stained cells was performed to detect cell cycle entry following angelicin treatment. The ratio of cells in the G1 and G0 phases following angelicin treatment increased significantly compared with the mock group (P<0.05; Fig. 2A), whilst the ratio of cells in the G2/M phases decreased substantially (P<0.05; Fig. 2A). To investigate the effects of angelicin IC30 treatment on HeLa or SiHa cells, colony formation was assessed by seeding cells at low density to obtain single-cell-derived colonies as previously described (14). Mock-treated HeLa and SiHa cells formed single-cell-derived colonies (Fig. 2B). By contrast, angelicin treatment substantially decreased the colony formation ability of both HeLa and SiHa cells (Fig. 2B). The effect of angelicin on tumour formation in soft agar was investigated. Consistent with the effects exerted on colony formation (>50 µM in diameter), angelicin treatment markedly decreased the tumour formation ability of the cells in soft agar compared with the control (Fig. 2C). Angelicin treatment substantially inhibited the migration and invasion of cells compared with mock treated cells (Fig. 2D and E).

Figure 2.

Angelicin inhibits the proliferation, colony formation, migration and invasion of cervical cancer cells. (A) Cell cycle distribution was measured by flow cytometry following propidium iodide staining. (B) Angelicin treatment reduced colony formation (C) tumour formation in soft agar (D), migration and (E) invasion in HeLa and SiHa compared with the mock group. *P<0.05 vs. mock group.

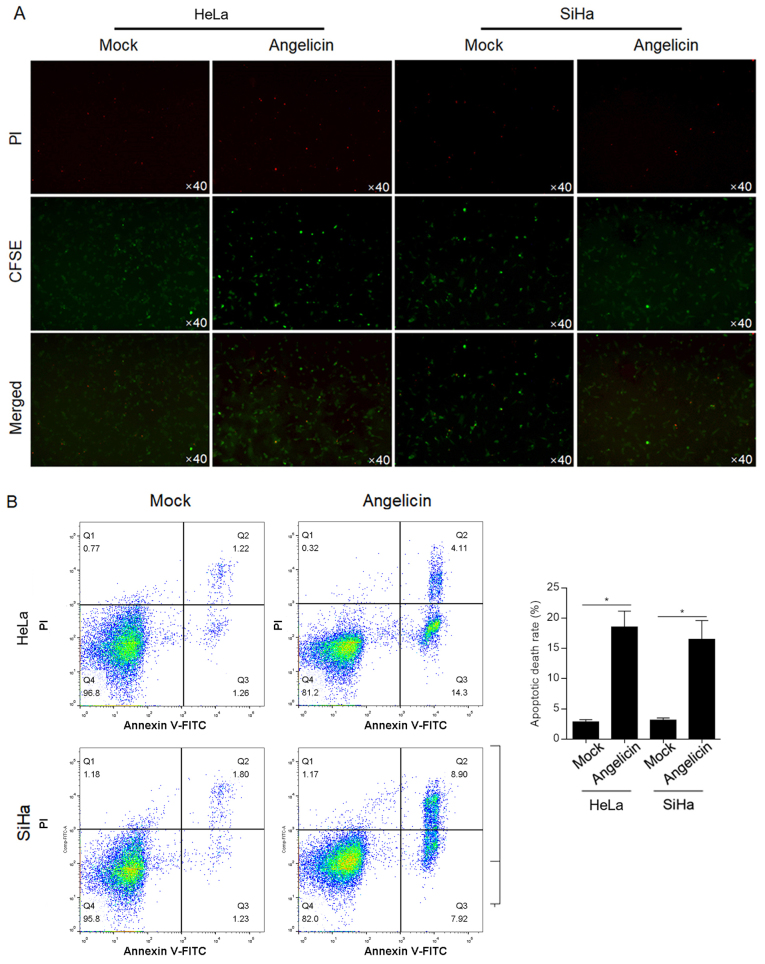

Angelicin induces apoptotic cell death in HeLa and SiHa cells

The cytotoxic effect of angelicin was verified by a cytotoxicity assay with CFSE-labelled HeLa or SiHa cells. CFSE-positive cells demonstrated no significant change following angelicin treatment compared with mock treated cells (Fig. 3A). Following PI staining, it was observed that angelicin treatment markedly increased the number of PI-positive cells compared with mock treated cells, indicating that angelicin treatment increased the cell death rate (Fig. 3A). To further confirm that the increased cell death by angelicin treatment was due to induction of apoptosis, Annexin V/PI double-staining was performed. Angelicin treatment increased the apoptotic cell death rate (Annexin V+/PI− and Annexin V+/PI+) in both HeLa (18.7±2.4%) and SiHa (16.9±3.1%) cells (P<0.05; Fig. 3B). Taken together, the results indicated that angelicin treatment inhibited the malignant behaviours of HeLa and SiHa cervical cancer cells and induced apoptotic cell death.

Figure 3.

Angelicin treatment induced cervical cancer cell death via apoptosis. (A) Following staining with CFSE, HeLa or SiHa cells were treated with angelicin at the IC50 for 24 h, followed by PI staining. The CFSE+/PI+ subpopulation indicated dead cells. (B) Annexin V-FITC and PI double-staining was performed following 24 h treatment with angelicin at the IC50 with Annexin V-FITC+/PI− and Annexin V-FITC+/PI+ cells. Representative histograms and quantification are presented. *P<0.05 vs. mock group. CFSE, carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester; PI, propidium iodide.

Angelicin inhibits autophagy in cervical cancer cells

The chemotherapy-induced inhibition of cell viability, proliferation or cell death leading to the demise of cancer cells is mediated by autophagic pathways (15,16). Therefore, the effects of angelicin treatment on autophagy were investigated in the present study. The regulatory effects of angelicin on autophagy were assessed by performing LC3B immunostaining. The results revealed that the LC3B-stained signal was greatly decreased following angelicin treatment for 24 h compared with the mock group in HeLa and SiHa cells (Fig. 4A). Chloroquine, a lysosome inhibitor inhibiting the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes and/or the activity of autolysosomes (17) was employed to accumulate LC3B-I and -II. Following the inhibition of LC3B degradation, the results revealed that angelicin treatment decreased the quantity of LC3B and cleaved LC3B-II compared with mock cells (Fig. 4B). The formation of an autophagosome involves the coordinated action of several Atg protein complexes (18–20). Thus, the expression of certain Atg proteins, including Atg3, Atg7 and Atg12-5, was determined via western blot analysis. Consistent with the change in LC3B, Atg3, Atg7 and Atg12-5 protein levels decreased following angelicin treatment compared with mock treatment (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Angelicin promoted autophagy in cervical cancer cells. (A) Immunofluorescence micrographs demonstrating LC3B staining (green) and nucleus staining (blue) following gangelicin treatment (27.8 µM for HeLa, 36.6 µM for SiHa). (B) Western blot analysis detected angelicin-induced LC3B expression in HeLa and SiHa cells. To inhibit the degradation of LC3B-II, cells were pre-treated with 5 µM chloroquine for 6 h. (C) Western blot analysis of Atg3, Atg7 and Atg12-Atg5 protein expression in both HeLa and SiHa cells. LC3B, microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3-β; Atg, autophagy related proteins.

Angelicin activates mTOR phosphorylation and potentially regulates malignant behaviours by modulating autophagy in cervical cancer cells

mTOR is a central regulator of several physiological processes, including autophagy. Therefore, the current study assessed whether angelicin treatment regulated mTOR and thus affected autophagy. The results revealed that Angelicin treatment markedly increased the phosphorylation of mTOR in HeLa and SiHa cells, and decreased LC3B-II when compared with mock treated cells (Fig. 5A). Following the addition of rapamycin, angelicin-induced mTOR phosphorylation was decreased, but the inhibitory effects of angelicin on autophagy were not fully reversed, indicating that mTOR might not be a direct target of angelicin, at least in part. To further confirm these results, cell viability and colony formation were measured following co-incubation with rapamycin and angelicin or rapamycin alone. As presented in Fig. 5B and C, angelicin treatment decreased the malignant behaviors of HeLa and SiHa cells, and indicated that rapamycin may exert its inhibitory effect in an mTOR-independent manner. Taken together, the results indicated that angelicin treatment regulated the phosphorylation of mTOR; however, this was not the main mechanism for affecting autophagy, which remains unknown.

Figure 5.

Angelicin activates mTOR phosphorylation and inhibits autophagy by an mTOR-independent pathway in cervical cancer cells. (A) Western blot analysis was performed following RAPA and angelicin co-treatment to identify whether autophagy stimulation by angelicin was dependent on mTOR phosphorylation. Following rapamycin and angelicin co-treatment, (B) cell viability and (C) colony formation were measured in HeLa and SiHa cells. *P<0.05 vs. mock group. RAPA, rapamycin; p, phosphorylated; LC3B, microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3-β; OD, optical density.

Discussion

Angelicin has been previously reported to possess anticancer properties. In liver cancer, by activating the PI3K/AKT1 signalling pathway, angelicin treatment induced mitochondrial-dependent apoptotic cell death (10). Angelicin transcriptionally regulates members of the Bcl-2 family of proteins that serve key roles in the regulation of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway (21). The Bax/Bcl-2 ratio is therefore altered to cause mitochondrial destabilization, which leads to the release of proapoptotic factors (22). In the non-small cell lung cancer cell line and its sub-line (A549 and A549/D16, respectively) that exhibits multidrug resistance, angelicin treatment promoted chemotherapy-induced apoptotic cell death and sensitized A549/D16 cells to chemotherapy (23). However, the antitumor effects of angelicin in human cervical carcinoma, as well as the mechanisms underlying its actions, are largely unknown. D'Anqiolillo et al (24) reported that angelicin exerts cytotoxic activity on HeLa cells, but did not elucidate the exact mechanism by which this occurs (24). Therefore, the aim of the present study was to assess the effects of angelicin on the human cervical carcinoma cell lines, HeLa and SiHa, and to investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying its action. To determine whether cervical carcinomas were sensitive to angelicin, the non-tumour cervical epithelial cell line ECT1/E6E7 was also analyzed.

The present study determined that angelicin exerted antitumor effects on HeLa and SiHa cells but demonstrated no detectable cytotoxity to ECT1/E6E7 cells. Treatment of both HeLa and SiHa cells with angelicin at the IC30 suppressed malignant behaviours, including proliferation, colony formation, tumour formation in soft agar, migration and invasion. When evaluating migrating ability, medium containing 1% FBS was used instead of serum-free medium, which may be a limitation to the present study. Treatment with the IC50 of angelicin significantly induced cell death via apoptosis. Flow cytometry was employed to determine angelicin-induced apoptosis, however, a study limitation was that the detection of apoptosis markers, such as caspase-3, was not performed. The present study identified that angelicin treatment greatly inhibited autophagy by measuring hallmarks of autophagy, including LC3BI, LC3BII, Atg3, Atg7 and Atg12-5. Emerging evidence has indicated that interactions between autophagy and apoptosis occur via crucial proteins, including mTOR and Atgs (25). Through these regulatory mediators of crosstalk, cooperation between autophagy and apoptosis has been established. However, the present in vitro study requires in vivo research to further confirm the results gained.

mTOR is a critical regulator of autophagy that integrates nutrient signals and cytokines from different pathways, inhibiting autophagy and promoting cell growth (26). Signal starvation inhibits the phosphorylation of mTOR and initiates autophagy by forming theunc-51-like kinase complex, which comprises Atg13 and a protein tyrosine kinase 2-family interacting protein of 200 kDa (27,28). The present study determined that angelicin treatment induced marked phosphorylation of mTOR without altering the total amount of mTOR. However, mTOR signalling has also been revealed to have no significant role in controlling autophagic flux (29), which may explain why rapamycin treatment failed to inhibit the effects of angelicin on autophagy regulation.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that angelicin treatment significantly inhibited malignant behaviours, including proliferation, colony formation, tumour formation, migration and invasion, in cervical cancer cells, potentially by inhibiting autophagy. Although angelicin treatment induced the phosphorylation of mTOR, its regulatory roles on autophagy and malignant behaviours were identified to be independent of mTOR signalling. Further studies are required to elucidate the exact molecular mechanisms underlying the regulatory role of angelicin on cervical cancer malignant behaviours. The results of the current study indicated that angelicin may have potential as a chemotherapeutic agent against cervical cancer.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Mrs. Yun Bai (Third Military Medical University, Chongqing) for language editing.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

YW, ZL and YC designed the experiments. XC, YL and DY performed cell culture and data analysis. YW wrote the manuscript. JD collected data and performed statistical analysis. NY is responsible for data collection. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burger H, Loos WJ, Eechoute K, Verweij J, Mathijssen RH, Wiemer EA. Drug transporters of platinum-based anticancer agents and their clinical significance. Drug Resist Updat. 2011;14:22–34. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lilic V, Lilic G, Filipovic S, Milosevic J, Tasic M, Stojiljkovic M. Modern treatment of invasive carcinoma of the uterine cervix. J BUON. 2009;14:587–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodríguez Villalba S, Díaz-CanejaPlanell C, Cervera Grau JM. Current opinion in cervix carcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2011;13:378–384. doi: 10.1007/s12094-011-0671-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai JH, Hsu LS, Huang HC, Lin CL, Pan MH, Hong HM, Chen WJ. 1-(2-Hydroxy-5-methylphenyl)-3-phenyl-1,3-propanedione induces g1 cell cycle arrest and autophagy in HeLa cervical cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:E1274. doi: 10.3390/ijms17081274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li N, Zhang W. Protein kinase C β inhibits autophagy and sensitizes cervical cancer HeLa cells to cisplatin. Biosci Rep. 2017;37:BSR20160445. doi: 10.1042/BSR20160445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kavli G, Midelfart K, Raa J, Volden G. Phototoxicity from furocoumarins (psoralens) of Heracleum laciniatum in a patient with vitiligo. Action spectrum studies on bergapten, pimpinellin, angelicin and sphondin. Contact Dermatitis. 1983;9:364–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1983.tb04386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lampronti I, Bianchi N, Borgatti M, Fibach E, Prus E, Gambari R. Accumulation of gamma-globin mRNA in human erythroid cells treated with angelicin. Eur J Haematol. 2003;71:189–195. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2003.00113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mira A, Shimizu K. In vitro cytotoxic activities and molecular mechanisms of angelica shikokiana extract and its isolated compounds. Pharmacogn Mag. 2015;11(Suppl 4):S564–S569. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.172962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang F, Li J, Li R, Pan G, Bai M, Huang Q. Angelicin inhibits liver cancer growth in vitro and in vivo. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:5441–5449. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.7219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fang W, Shu S, Yongmei L, Endong Z, Lirong Y, Bei S. miR-224-3p inhibits autophagy in cervical cancer cells by targeting FIP200. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33229. doi: 10.1038/srep33229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spanò V, Parrino B, Carbone A, Montalbano A, Salvador A, Brun P, Vedaldi D, Diana P, Cirrincione G, Barraja P. Pyrazolo[3,4-h]quinolines promising photosensitizing agents in the treatment of cancer. Eur J Med Chem. 2015;102:334–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruni R, Barreca D, Protti M, Brighenti V, Righetti L, Anceschi L, Mercolini L, Benvenuti S, Gattuso G, Pellati F. Botanical sources, chemistry, analysis, and biological activity of furanocoumarins of pharmaceutical interest. Molecules. 2019;24:E2163. doi: 10.3390/molecules24112163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colter DC, Class R, DiGirolamo CM, Prockop DJ. Rapid expansion of recycling stem cells in cultures of plastic-adherent cells from human bone marrow. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3213–3218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu L, Sun S, Wang T, Li Y, Jiang K, Lin G, Ma Y, Barr MP, Song F, Zhang G, Meng S. Oncolytic newcastle disease virus triggers cell death of lung cancer spheroids and is enhanced by pharmacological inhibition of autophagy. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5:3612–3623. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trout JJ, Stauber WT, Schottelius BA. Increased autophagy in chloroquine-treated tonic and phasic muscles: An alternative view. Tissue Cell. 1981;13:393–401. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(81)90013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Mammalian autophagy: Core molecular machinery and signaling regulation. CurrOpin Cell Biol. 2010;22:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng Y, He D, Yao Z, Klionsky DJ. The machinery of macroautophagy. Cell Res. 2014;24:24–41. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tooze SA, Yoshimori T. The origin of the autophagosomal membrane. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:831–835. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adem J, Ropponen A, Eeva J, Eray M, Nuutinen U, Pelkonen J. Differential expression of Bcl-2 family proteins determines the sensitivity of human follicular lymphoma cells to dexamethasone-mediated and anti-BCR-mediated apoptosis. J Immunother. 2016;39:8–14. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen TC, Yu MC, Chien CC, Wu MS, Lee YC, Chen YC. Nilotinib reduced the viability of human ovarian cancer cells via mitochondria-dependent apoptosis, independent of JNK activation. Toxicol In Vitro. 2016;31:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsieh MJ, Chen MK, Yu YY, Sheu GT, Chiou HL. Psoralen reverses docetaxel-induced multidrug resistance in A549/D16 human lung cancer cells lines. Phytomedicine. 2014;21:970–977. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D'Anqiolillo F, Pistellia L, Noccioli C, Ruffoni B, Piaqqi S, Scarpato R, Pistelli L. In vitro cultures of Bituminariabituminosa: Pterocarpan, furanocoumarin and isoflavone production and cytotoxic activity evaluation. Nat Prod Commun. 2014;9:477–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li M, Gao P, Zhang J. Crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis: Potential and emerging therapeutic targets for cardiac diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:332. doi: 10.3390/ijms17030332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamada Y, Yoshino K, Kondo C, Kawamata T, Oshiro N, Yonezawa K, Ohsumi Y. Tor directly controls the Atg1 kinase complex to regulate autophagy. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:1049–1058. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01344-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hara T, Mizushima N. Role of ULK-FIP200 complex in mammalian autophagy: FIP200, a counterpart of yeast Atg17? Autophagy. 2009;5:85–87. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.1.7180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mizushima N. The role of the Atg1/ULK1 complex in autophagy regulation. CurrOpin Cell Biol. 2010;22:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi H, Merceron C, Mangiavini L, Seifert EL, Schipani E, Shapiro IM, Risbud MV. Hypoxia promotes noncanonical autophagy in nucleus pulposus cells independent of MTOR and HIF1A signaling. Autophagy. 2016;12:1631–1646. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1192753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.