Abstract

New tools for measuring protein expression in individual cells complement single-cell genomics and transcriptomics. To characterize a population of individual mammalian cells, hundreds to thousands of microwells are arrayed on a polyacrylamide-gel-coated glass microscope slide. In this “open” fluidic device format, we explore the feasibility of mitigating diffusional losses during lysis and polyacrylamide-gel electrophoresis (PAGE) through spatial control of the pore-size of the gel layer. To reduce in-plane diffusion-driven dilution of each single-cell lysate during in-microwell chemical lysis, we photo-pattern and characterize microwells with small-pore-size sidewalls ringing the microwell except at the injection region. To reduce out-of-plane-diffusion-driven-dilution-caused signal loss during both lysis and single-cell PAGE, we scrutinize a selectively permeable agarose lid layer. To reduce injection dispersion, we photopattern and study a stacking-gel feature at the head of each <1 mm separation axis. Lastly, we explore a semienclosed device design that reduces the cross-sectional area of the chip, thus reducing Joule-heating-induced dispersion during single-cell PAGE. As a result, we observed a 3-fold increase in separation resolution during a 30 s separation and a >2-fold enhancement of the signal-to-noise ratio. We present well-integrated strategies for enhancing overall single-cell-PAGE performance.

Graphical Abstract

Cell-to-cell variation in genomic and proteomic expression is a hallmark of biological processes.1 Insight into genomic and transcriptomic variation has advanced rapidly as a result of powerful single-cell-analysis tools that benefit from highly specific recognition by complementary nucleic acid binding and versatile signal-amplification methodologies. However, direct measurement of proteins in single cells is more challenging, given the physicochemical complexity, diversity, and dynamics of these biomolecules.2,3 State-of-the-art protein analysis relies heavily on immunoassays. Workhorse formats include immunohistochemistry,4 flow cytometry,5 mass cytometry,6-8 and immunosorbent assays.9-11 While underpinning single-cell protein detection assays, immunoassay performance is inherently dictated by the availability and selectivity of antibody immunoreagents.

To enhance selectivity for a protein target, some approaches implement immunoassays with not one but a pair of epitope-selective antibodies (e.g., proximity-ligation assays12,13 and sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, ELISAs14). This approach is useful when a pair of antibody probes is available. Another approach for conferring selectivity to pooled-cell samples is performing an electrophoretic protein separation and a subsequent immunoassay (i.e., immunoblotting). By separating proteins on the basis of differences in electrophoretic mobility, immunoblotting can readily identify off-target signals, distinguish between protein isoforms, and identify some post-translational modifications (PTMs).15 The two-stage immunoblot relaxes the requirement for a pair of target-selective probes, while providing enhanced selectivity over a simple immunoassay, which is especially relevant for the detection of proteoforms (e.g., isoforms and PTMs)16,17).

When utilized to separate proteins on the basis of differences in molecular mass, the immunoblot is called a Western blot.18-21 Western blots electrophoretically separate denatured proteins by molecular sieving through the pores of a polyacrylamide (PA) gel in the presence of ionic detergents (i.e., sizing). After the sizing step, protein bands are transferred to a polymer membrane for on-membrane immunoprobing. Although effective in enhancing the selectivity of immunoassays, conventional Western blotting requires thousands-to-millions of pooled cells for each measurement. It also relies on labor-intensive interventions and time-consuming steps.22

Recent interest has catalyzed the development of new immunoblotting tools, including microchip capillaries23 and large-format, slab-gel Western-blot form factors.24 Advances in microfluidic design have advanced the selectivity of Western blotting to small sample volumes25,26 and even single-cell resolution.27-29 Polyacrylamide-gel electrophoresis (PAGE) separations in microchannels result in high separation resolution within a short separation time and length. However, when applied to single cells, “open” fluidic devices without enclosed microchannels or capillary features can integrate and expedite cell capture and immunoblots. Although early single-cell electrophoresis did not utilize microwells,30-32 Comet assays have embedded single cells in layers of agarose for isolation, cell lysis, and subsequent DNA agarose electro-phoresis.33,34

Compared with enclosed microchannels, open fluidic devices can expedite single-cell sample preparation with arrays of microwells that concurrently isolate large numbers of individual cells using gravity-based sedimentation as a cell-seating mechanism.1 These open fluidic devices, which are similar to a conventional microscope slide, are rapid to fabricate, straightforward to operate, and compatible with imaging.35-38 For example, our single-cell immunoblotting uses devices consisting of a microscope slide coated with a thin layer (30 μm) of a photoactive PA gel, which is micropatterned with a microwell array.39 Single cells are isolated in each microwell and then chemically lysed. The solubilized, denatured proteins are then electrophoretically injected into the surrounding PA gel for single-cell polyacrylamide-gel electrophoresis (scPAGE). After the protein separation, protein blotting (immobilization) occurs using brief ultraviolet (UV) activation of benzophenone in the PA gel, which covalently immobilizes protein for subsequent in-gel immuno-probing. This open fluidic scPAGE format achieves adequate separation and detection sensitivity.36-39 To improve separation resolution in the open fluidic format, various approaches are scrutinized, such as using gradient gels40 and implementing other electrophoresis modules such as isoelectric focusing.41

Here, we implement and study dispersion-control strategies against a benchmark comparator. That comparator is defined as a scPAGE device comprising a uniform 10% T PA gel with open microwells.17,27,36,39 Against that comparator, we seek to minimize sources of both material loss (signal) and information loss (separation resolution) in single-cell lysis and electrophoresis in open fluidic immunoblotting devices, which arise from advection and diffusion, including that exacerbated by Joule heating. To mitigate dilution and dispersion, we utilize microfluidic-design strategies that limit diffusion and Joule heating. To reduce in-plane dispersion, we adopt grayscale photopatterning40 to create microwells having dense-gel walls except for a defined sample-injector region and stacking gel. The sample injector and stacking gel are located at the head of each of the hundreds of scPAGE-separation axes. To reduce out-of-plane dilution, we minimize diffusion and reduce Joule-heating-induced temperature increases during electrophoresis by encapsulating the device.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

2,2-Azobis[2-methyl-N-(2-hydroxyethyl) pro-pionamide] (VA-086, 1% (w/v), photoinitiator) was purchased from Waco Chemical (Richmond, VA). Tetramethy-lethylenediamine (TEMED, T9281), ammonium persulfate (APS, A3678), β-mercaptoethanol (M3148), and a polymer precursor solution composed of 30% T and 2.7% C acrylamide/bis-acrylamide (37.5:1, A3699) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Triton X-100 (BP-151) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Premixed 10× Tris/glycine/SDS-PAGE buffer (25 mM Tris, pH 8.3; 192 mM glycine; 0.1% SDS) was purchased from BioRad (Hercules, CA). Deionized water (18.2 MΩ) was obtained using an Ultrapure water system (Millipore, Burlington, MA). The cell lysis and PAGE buffer contained 0.5% SDS, 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, and 0.25% sodium deoxycholate (D6750, Sigma-Aldrich) in 12.5 mM Tris and 96 mM glycine (pH 8.3, 0.5× from a 10× stock; 161-0734, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). FITC (Isomer-I) used for polyacrylamide-gel imaging was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Cell Lines.

Human glioblastoma cell karyotype U25142 was obtained from the UC Berkeley Tissue Culture Facility via the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The U251 cells were stably transduced with Turbo-GFP by lentiviral infection (multiplicity of infection = 10). The cells were maintained in high-glucose DMEM (11965, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 1 mM sodium pyruvate (11360-070, Life Technologies), 1× MEM nonessential amino acids (11140050, Life Technologies), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (15140122, Invitrogen), and 10% calf serum (JR Scientific, Woodland, CA). Cells were maintained in a humidified 37 °C incubator with 5% CO2.

SU8-Wafer and Gel-Slide Fabrication.

For all devices reported here, the microwell-feature heights were 40 μm, and the diameters were 50 μm. The chemically polymerized PA gels employed in control experiments included 0.08% APS and 0.08% TEMED. For photopolymerized gradient gels, the precursor solution contained 1% (w/v) VA-086 photoinitiator and an acrylamide monomer concentration of 20% T (w/v). The precursor was degassed under a house vacuum and sonicated for 3 min just prior to polymerization. The grayscale masks used for photopolymerization were designed in-house using AutoCAD and fabricated on soda-lime glass (Front Range Photomask, LLC, Palmer Lake, CO). Before UV-activated photopolymerization, the glass-SU8 mold and the grayscale chrome mask were aligned using an OAI Hybralign Series 400 (Optical Associates, Inc., San Jose, CA) mask aligner. After alignment, the stack was exposed to UV (19 mW/cm2) for 25 s to polymerize the PA-gel layer. After polymerization, the stack was disassembled, and the polymerized-gel slab was carefully removed from the mold using a razor blade.

Allylamine-Gel-Density Imaging.

To visualize the spatially varying density of the PA gel, allylamine was included in the gel-precursor solution.40 Allylamine was added to the gel-precursor solution at a 1:100 molar ratio with acrylamide.43 The allyl group incorporates directly into the acrylamide fibers during free-radical polymerization. The UV-exposure time was increased by ~33% as the allyl group slows polymerization.44 The resulting allylamine gels were soaked in 0.1 mg/mL FITC in DI water overnight. The primary amine has a positive charge in water and reacts with the negatively charged carboxyl group on the FITC molecule. Excess FITC was removed by soaking the gel in water for a minimum of 2 h. To estimate the gel-pore-size distributions in gels created by grayscale photo-patterning, the allylamine-containing, FITC-decorated gels were imaged by epifluorescence microscopy.

Sample Loading on PA-Gel Slides.

Solutions of know purified proteins were utilized as a molecular-mass ladder to assess scPAGE performance. Alexa Fluor 488 labeled purified bovine serum albumin (BSA*, A13100) and Alexa Fluor 488 labeled purified ovalbumin (OVA*, O34781) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Turbo-GFP (GFP, FP552) was purchased from Evrogen (Moscow, Russia). The purified proteins were diluted to a final concentration of 1 μM in lysis buffer. Gels of various compositions were studied by incubating the purified protein-ladder solution with each gel for 15 min (to allow the ladder solution to preferentially partition into each microwell) and then performing PAGE on the contents of each microwell.

For scPAGE, a suspension of cells was created by trypsin release from the culture chamber, centrifugation of the cell suspension to remove trypsin, and resuspension of the cell pellet in ice-cold PBS resulting in a final concentration of 5.0 × 106 cells/mL. A 200 μL aliquot of each cell suspension was pipetted onto the PA gel and incubated for 5–10 min to allow cells to gravity-settle (sediment) into microwells. The device was then washed 3× with PBS to remove excess cells from the PA-gel surface prior to lysis and scPAGE analysis of the cells seated in the microwells.

scPAGE in an Open Fluidic Format.

The microwell-stippled PA gel slide was seated in a custom PAGE chamber created by 3D printing of acrylonitrile butadiene styrene. The PAGE chamber was 3 × 8 × 3 cm (width × length × height) in size. Platinum wires (0.5 mm in diameter, 267228, Sigma-Aldrich) were placed along the long edge of the chamber and interfaced with alligator clips to a standard PAGE power supply (Model 250/2.5, Bio-Rad). After sample (purified protein or cell) loading, the PA-gel slide was placed on the bottom of the open chamber, and the whole device was mounted on the stage of a fluorescence microscope for real-time imaging. To complete cell lysis, 10 mL of lysis buffer was poured into the chamber and incubated for 35 s. Control studies that utilized the purified-protein-ladder solution (and not cell suspensions) were likewise subjected to a 35 s incubation with lysis buffer. To initiate sample injection and protein PAGE, an electric field of 50 V/cm was applied for both the open chamber and the enclosed device (described below). A 150 V potential was applied to the 3 cm wide open chamber to create a 50 V/cm electric field.

scPAGE with an Agarose Lid to Mitigate Joule Heating.

To mitigate Joule-heating-mediated diffusion of the analytes during separation, we fabricated scPAGE devices with an agarose lid to replace the 10 mm thick layer of buffer in the standard scPAGE. Two 250 μm thick plastic shims were attached to opposite sides of the square gel area on the gel slide as spacers for casting agarose on top of the PA gel (Figure S1). After loading single cells into the microwells as in the standard scPAGE assay, 0.5 mL of predissolved 1% agarose precursor solution cooled to 37°C was added on top of the PA gel. The precursor was made with PBS to prevent cell rupture due to osmotic pressure. Immediately following the addition of the agarose, a glass slide was placed on top of the agarose-gel solution and gently pressed down such that it was in contact with the spacers. The agarose gelled rapidly within 5 s and formed a thin layer (100–200 μm) on top of the PA gel, encapsulating the microwells. Following the gelation of the agarose gel, the glass slide was removed by sliding off the gel to reveal the smooth surface of the agarose layer. Afterward, two electrode wicks were placed on opposite sides of the gel and connected to graphite electrodes, which were connected to the standard PAGE power supply. 200 μL of lysis buffer was pipetted on top of the agarose-gel layer to initiate a 45 s cell-lysis period. For purified protein samples, samples were pipetted on top of the PA gel and incubated for 15 min before construction of the agarose-gel layer. Immediately after cell lysis or protein incubation, a 50 V/cm electric field was applied for PAGE.

Fluorescence Imaging.

Cell lysis and PAGE were imaged using a time-lapse acquisition mode (MetaMorph software, Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA) with 200 ms exposure times and 1 s intervals at 1 × 1 pixel binning through a 10× magnification objective (Olympus UPlanFLN, NA 0.45, Tokyo, Japan). The Olympus IX71 inverted fluorescence microscope was equipped with an Andor iXon+ EMCCD camera, an ASI motorized stage, and a shuttered-mercury-lamp light source (X-cite, Lumen Dynamics, Mississauga, Canada). After defining a region of interest (ROI), encompassing a microwell and the abutting separation axis, fluorescence micrographs were collected throughout lysis and PAGE. To measure and then subtract out background signal, an area adjacent to (but outside of) the sample-manipulation ROI was similarly interrogated. All image analysis was performed using ImageJ 1.46r (NIH, Bethesda, MD)17 with quantification of protein-peak widths, heights, and locations extracted using Gaussian-curve fitting in MATLAB (R2013b, Curve Fitting Toolbox; MathWorks, Natick, MA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Design to Enhance scPAGE Performance.

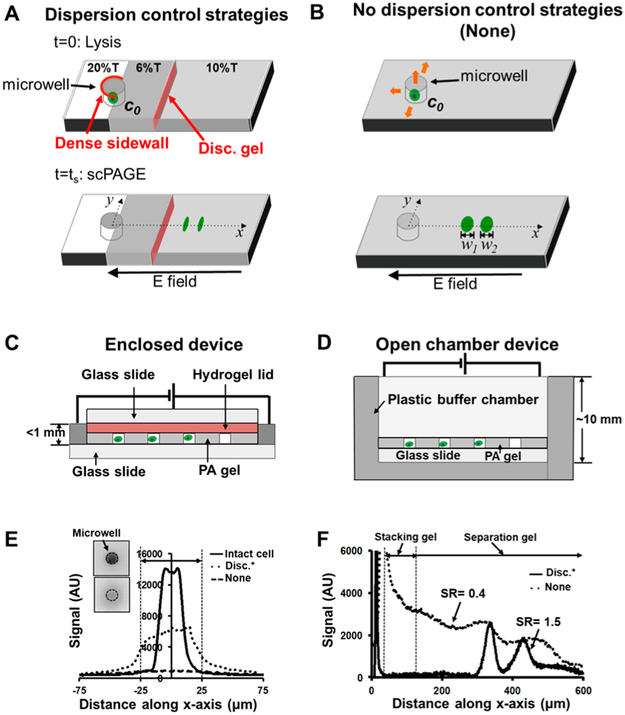

We sought to identify and mitigate sources of scPAGE performance degradation by inspecting each stage of single-cell lysis and scPAGE. To accomplish this goal, we implemented and studied dispersion-control strategies (dispersion-control condition, Disc+; Figure 1A) against a benchmark comparator (Figure 1B), which was our earliest and most widely used device design. That comparator is defined as an scPAGE device comprising a uniform 10% T PA gel with open microwells and is referred to throughout as the “None” condition (Figure 1B), given that no dispersion-control strategies are implemented in the comparator. First, in-plane (x–y) losses arise during lysis from diffusion-driven dilution of single-cell lysates and during scPAGE from both injection dispersion and dispersion generated by Joule heating. Second, out-of-plane (z) losses also arise from Joule-heating-mediated dispersion as well as from any convective flow of buffer solution over the PA-gel slide. We scrutinize and address each in turn. To reduce in-plane diffusion, we designed, fabricated, and assessed scPAGE (Figure 1A) that (i) employed microwells partially ringed by a dense PA-gel sidewall (high-density PA gel), which defined a lower-density sample-injector region, from the microwells into the contiguous PAGE-separation axis and (ii) included a sample-stacking gel created by a discontinuity in pore size along each scPAGE-separation lane. To reduce out-of-plane losses (Figure 1C), we (iii) applied a selectively permeable agarose layer on top of the open fluidic device to reduce convection and diffusion. We also (iv) constructed a semienclosed device that reduced the cross-sectional area of the chip, thus reducing Joule-heating-induced dispersion. The benchmark comparator is set up with an open-chamber device (Figure 1D). Figure 1E,F shows the effect of reducing protein diffusion during cell lysis and the improved separation with the Disc+ condition, which results in a narrower injection width and higher separation resolution.

Figure 1.

Benchmarking to ascertain effectiveness of dispersion-reduction strategies in scPAGE. (A) Schematic of the dispersion-control condition (Disc+), which comprises a uniform PA gel for scPAGE, with two regions of interest: (i) a dense PA-gel sidewall partially ringing each microwell to define an injector region in the PAGE-separation axis and (ii) a stacking gel defined by a step increase in gel density down the separation axis to reduce sample-injection dispersion during scPAGE. The lysis step prior to separation is indicated by t = 0; scPAGE duration is indicated by t = ts. (B) Schematic of the benchmark condition incorporating no dispersion control (None). The benchmark None condition comprises a uniform 10% T PA gel with open microwells. (C) Disc+ system setup: enclosed device that incorporates an agarose-hydrogel lid. This design is reduces protein loss during cell lysis and protein diffusion during separation by mitigating Joule heating. (D) None-system setup: open-chamber device with electrophoresis buffer filled to 10 mm. (E) Reduction of protein diffusion during cell lysis resulting in narrower injection width. Data shows representative tGFP-concentration profiles at the initiation of cell lysis measured at the cross-sections of microwells, each containing a single U251 GFP human glioblastoma cell. (F) Concentration profiles of separated FITC-BSA* and FITC-OVA* during scPAGE, illustrating the impacts of diffusion and Joule-heating mitigation on separation performance. The Disc+ condition is the combination of the patterned PA gel with dense sidewalls, the stacking gel, and the enclosed PAGE device. The open-chamber condition comprises a uniform PA gel in an open-chamber device.

Small Pore-Size Sidewalls Reducing In-Plane (x-y) Lysate Dilution.

In the open-microwell system, cell lysis proceeds after 10 mL of lysis buffer is poured over the PA-gel-slide surface (buffer fluid height ~1.0 cm, Figure 1D). Lysate losses are driven by two mechanisms: (1) in-plane diffusion of proteins from microwells into the surrounding gel layer dilutes lysate concentrations and broadens the injected peaks, and (2) flow of buffer over and into the microwells entrains protein lysate in the flowing buffer and washes lysate out of and away from the microwell. In previous research, our group has observed cell lysis ~10 s after buffer application, and protein losses are estimated at 40.2 ± 3.6% for open-microwell systems.36 Proteins with larger diffusion coefficients are impacted preferentially by the loss mechanism.36

As mentioned, we address in-plane diffusive losses during lysis and injection dispersion by photopatterning small-pore-size microwell walls (i.e., higher-density gel, ~20% T) within an injector region of the large-pore-size PA gel (i.e., lower-density gel, ~6%) at the head of the scPAGE-separation axis (Figure 2A) for protein injection into the abutting PAGE-separation axis. To reduce injection dispersion, we photo-patterned a stacking region (6–10% T) at 150 μm along the scPAGE axis and aligned it with the injection region.

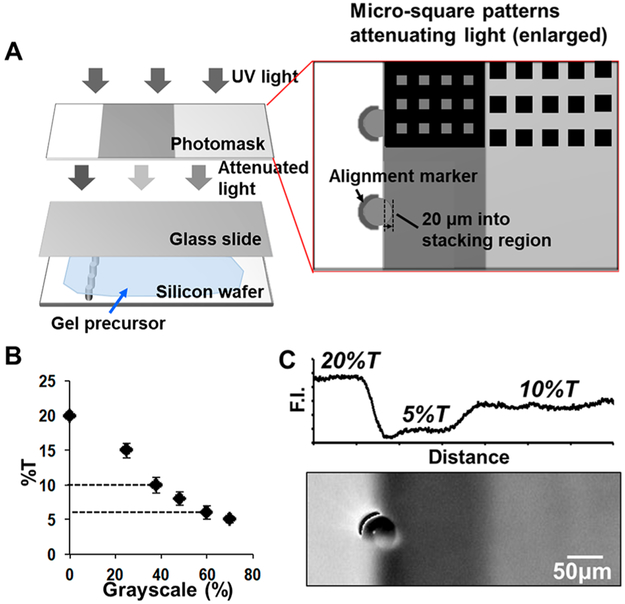

Figure 2.

Grayscale photopatterning creating nonuniform gel density around the microwells, defining an injector region and stacking gel for scPAGE. (A) Schematic of grayscale photopatterning to create nonuniform PA gels aligned to each scPAGE microwell. The grayscale photomask consists of arrays of transparent and opaque squares (5–20 μm in length). Squares are not to scale. (B) Calibration of the relationship between the photomask grayscale values and PA-gel density assessed by electrophoretic mobility. For patterning a 6% T stacking gel and a 10% T separation gel, 60 and 40% grayscale patterns were used, respectively. (C) PA gel density changes along the separation axis at the interface of stacking gel and separation gel (higher signal correlates with higher percent T). Fluorescence micrograph of an FITC-decorated allylamine gel reports nonuniform gel density around the microwell periphery and into the separation axis (right-hand side of the image).

To fabricate nonuniform-pore-size PA gels, we use a chrome grayscale mask to spatially attenuate UV intensity and thus photopattern gel density.40 Attenuation of UV locally alters the rate of free-radical production and thus polymerization. If polymerization is halted prior to completion, the opacity of the grayscale mask determines the effective local PA-gel density (and pore size) in the photopatterned gel. Figure 2A depicts the UV-exposure configuration and a portion of the grayscale-mask design in the stacking-gel and separation-gel regions. The grayscale characteristic is generated using arrays of opaque squares (5–30 μm in size) patterned at different densities.40 The aligned stack consists of a grayscale chrome mask, a methacrylate-functionalized glass slide (functional group facing down), gel-precursor solution, and a glass-SU8 mold. The mask was aligned at a 1 mm focus above the gel. Positioning the grayscale mask above the gel blurs the image of the array of opaque squares on a transparent background into homogeneous, attenuated illumination.40 The grayscale level was calculated as the fractional area covered with opaque squares. For example, a grayscale of 60% means that 60% of the area is opaque and 40% of the area allows UV transmission.

To create the high-PA-density microwell walls, injector regions, and stacking gel aligned to the scPAGE-separation axis, we utilized a series of three grayscale areas on the grayscale mask. A critical step is the alignment of the microwell-sidewall region having 20% T to the 6% T boundary, as this alignment ensures that the 20% T region does not obscure the injector region. Alignment markers (fiducials) ensure that the microwell features on the SU-8 mold sit ~20 μm into the injector region.

To quantify the resultant gel density, we measured the electrophoretic mobility of GFP in gels fabricated with different grayscale-mask opacities and then calibrated the electrophoretic mobility of GFP in chemically polymerized PA gels of uniform pore sizes (Figure 2B). Calibration of electromobility indicated that photomasks with a sequence of grayscale opacities of 0, 40, and 60% yielded PA gels with discontinuous effective gel densities of 20, 10, and 6% T, respectively. Figure 2C shows an FITC visualization of such a PA gel, with fluorescence intensity as a proxy for PA-gel density (pore size). Note the increase in fluorescence intensity at the interface of the 5 and 10% T gel regions, indicating a stacking gel. During the 25 s UV-polymerization step, acrylamide monomers are undergoing diffusion; thus, the interface is a gradient gel density across the 150 μm long stacking region rather than a step change.45

To reduce out-of-plane material loss during the cell-lysis step, we settled cells into microwells and then applied a thin layer of agarose (100–200 μm) and a glass slide “lid” on top of the PA gel. The agarose layer encapsulates cells in each microwell (Figures 1C and S1). We hypothesize that the agarose layer prevents convective dilution of cell contents into the bulk-fluid layer on top of the agarose and confines cell lysate to the microwell while allowing small ions and surfactant micelles to diffuse into the microwell. Estimates of the time required for molecules smaller than proteins (0.5% SDS micelles and small Na+ ions) to diffuse through a 2% agarose layer are reported in Figure 3A. From the literature,, we estimated the diffusion coefficients for SDS micelles (2.7 × 10−5 cm2/s) and small ions (1.6 × 10−5 cm2/s for Na+, 1.0 × 10−5 cm2/s for glycine) in 2% agarose gels.46-50 Lysis buffer diffuses through the agarose layer in <10 s. Additionally, the agarose layer prevents wash out of protein lysate from the microwells. Under bright-field examination and Calcein AM live-cell staining, we observe intact cells after application of the agarose (Figure 3B). After applying 200 μL of lysis buffer on top of the agarose layer, we observe cell-membrane disruption within 20 s (compare with <10 s without the agarose layer) because of the added time of diffusion, as shown in Figure 3A. We observed protein release from the cells as well (tGFP from U251-GFP cells, Figure 3B).

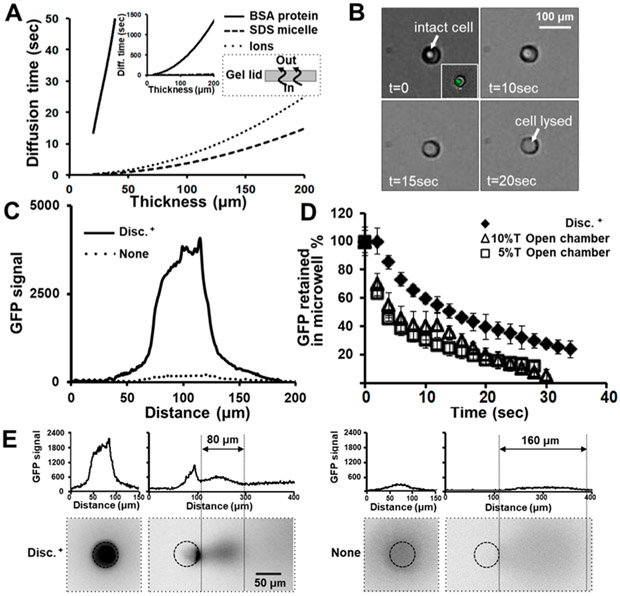

Figure 3.

Nonuniform-pore-size PA gels reducing analyte dispersion during cell lysis and sample injection. (A) Estimated diffusion time for lysis buffer and lysate molecules through various agarose-layer thicknesses. Small lysis-buffer components (ions and micelles) can diffuse through agarose, whereas larger species, including proteins, cannot diffuse as readily. The inset shows a wider y-axis to indicate the BSA*-diffusion time scale. (B) Viable single U251-GFP cells after encapsulation by agarose. (C) Epifluorescence micrographs reporting the GFP distribution at completion of a 30 s cell-lysis period. The patterned PA gel with the agarose lid (Disc+) and the uniform 10% T PA gel with open microwells (None) are shown. (D) Monitoring of fluorescence intensity during lysis of U251-GFP cells in microwells with high-density PA-gel sidewalls and an agarose lid vs in microwells of a uniform gel, open fluidic device. Error bars are standard deviations (n = 3). (E) Representative epifluorescence micrographs and accompanying concentration profiles for in situ single-cell lysis and protein injection in two conditions: the patterned-PA-gel and agarose-lid configuration (Disc+) and the uniform 10% T PA gel and open-microwell configuration (None). The analyte distribution is shown after 30 s of the cell-lysis period and 1 s after injection. Microwell edges are highlighted for clarity.

To assess the impact of our proposed lysate-dilution-mitigation strategies, we settled U251-GFP cells into micro-wells and observed tGFP diffusion during a 30 s lysis period using epifluorescence microscopy (Figure 3C,D). We performed the analysis under the Disc+ condition, which features high-density sidewalls and an agarose encapsulation layer, and compared the results with those from a uniform 10% T PA gel with open microwells, which we called None in Figure 3C. As a baseline, we observed a 90% loss of fluorescence signal from tGFP in the None condition. In contrast, the Disc+ condition retained 5× more protein signal than the None condition.

We observed uniform and isotropic diffusion distribution around the microwells under all conditions. On the basis of our observations, the diffusive broadening in the injection region (the patterned 6% T zone at the injection site of the microwell) does not exceed the diffusive broadening in the high-density regions, which warrants further investigation (Figure 3E). Within the microwells, a nonuniform fluorescence distribution can be observed (Figure 3C,E), which we attribute to nonuniform initial-concentration distributions.

More than 30% of the total tGFP fluorescence was retained in the microwell after 30 s of lysis with the Disc+ condition. In comparison, <10% of the total tGFP fluorescence was retained in the microwell with the uniform-gel and open-chamber format. In the open chamber, we observed a rapid signal decrease during the first 10 s of lysis, which we attribute to advective entrainment and washout during lysis-buffer introduction. Consequently, we conclude that the high-density PA gel (20% T) around the microwells and the agarose encapsulation layer act in concert to limit dilutive losses (Figure 3D).

We further sought to determine the impact of injection dispersion on scPAGE separation resolution (SR). We observe more concentrated protein lysate confined to the microwell in the Disc+ condition that uses the high-density PA-gel sidewalls and an agarose encapsulation layer, as compared with in the None condition (no mitigation, Figure 3E). After electro-phoretic injection, the protein-peak width is 2× narrower (80 vs 160 μm, n = 5) with the Disc+ configuration, as compared with no mitigation.

Enclosed PAGE Device Reducing Joule-Heating-Induced Diffusion.

scPAGE is performed within a thin PA-gel layer that sees substantial out-of-plane diffusion (and dilution) from each protein peak during the 30 to 40 s of electrophoresis. These two aspects of diffusion are accelerated by Joule-heating-induced temperature increases of ΔT = ~20 °C during PAGE,51-53 which results in ~2× higher diffusivity. As such, we sought to implement modifications to the open fluidic geometry to reduce Joule heating to improve separation performance.54-57

In macroscale PAGE, the composition of the separation buffer has been tuned to reduce the conductivity and thus reduce Joule heating.58-60 However, in scPAGE, the buffer composition is constrained by demands that the reagent complete multiple functionalities: cell lysis, protein denaturation, protein solubilization, and PAGE. The need for ionic components means that a design with low conductivity is not feasible. Design of the materials and geometry of the separation platform can also decrease heating61-64 by enhancing heat dissipation (e.g., increasing or decreasing the thermal mass and increasing the surface-area-to-volume ratios). While trying to maintain an open-fluidic-device framework as much as as possible, we took the following multipronged approach: (1) reducing the device cross-sectional area (i.e., higher electrical resistance) and decreasing the distance between electrodes (i.e., lower voltage applied for the same amount of electric field) to reduce the electrical current and voltage during scPAGE (Figure S2), (2) decreasing device thickness and increasing the surface-area-to-volume ratio to yield ~3× smaller thermal resistance (Supporting Information), and (3) enhancing heat dissipation away from the device by adding a glass lid (compared with poor thermal dissipation from the air–buffer interface used in the open-chamber configuration).

We sought to assess relative temperature changes in each configuration. To estimate temperature in the devices, we positioned an IR sensor above each PAGE chamber (Figure 4A). Over the 35 s of PAGE (E = 50 V/cm), we observed temperature increases of 0.418 ± 0.016 °C/s (n = 3) for the open chamber and 0.01 ± 0.0002 °C/s (n = 3) for the enclosed device. The buffer conductivity is expected to increase as the temperature increases (Δconductivity = 1.9% per degree of increase in the buffer temperature, near room temperature65), which in turn increases electrical current with a constant applied voltage, as was observed with the open-chamber device (Figure 4A).

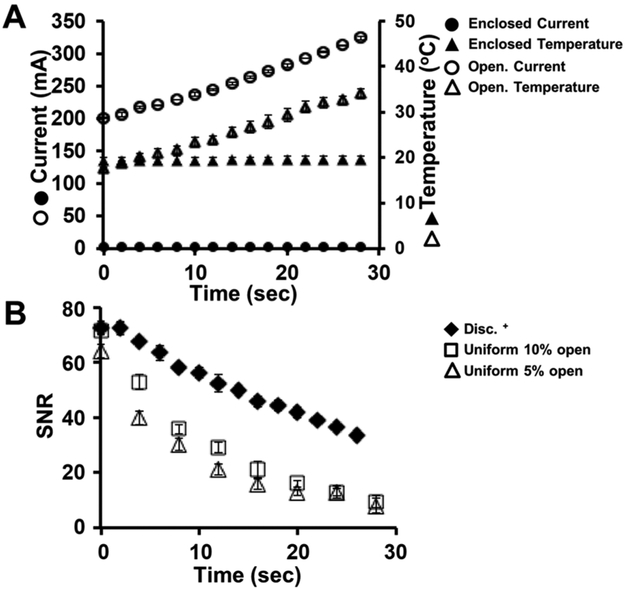

Figure 4.

Reduction of Joule heating during scPAGE in the enclosed device. (A) Local temperature measured by an IR sensor and electrical current during scPAGE in open and enclosed scPAGE devices (tPAGE = 35 s, E = 50 V/cm). (B) Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) measured for PAGE of OVA* in an open chamber and in the Disc+ format (cOVA*=0.5 μM, E = 50 V/cm). Error bars are standard deviations (n = 3).

To corroborate the IR temperature readings, we considered changes in the electrical properties of the electrophoresis buffer. Because the geometry of the electrical conductor (i.e., the buffer) and the applied voltage are constant during electrophoresis, the measured change in current is proportional to the buffer-conductivity changes (Figure 4A). We posit that the change in buffer conductivity is a reasonable proxy for the Joule heating given the linear scaling of conductivity with temperature.66 Given the reduced slope of the current over time, the buffer conductivity was more stable in the enclosed device than in the open device, and thus we inferred that Joule heating was reduced in the enclosed device. To further corroborate our measured temperature rise, our previous studies40 report an increase in electrophoretic mobility during scPAGE in a homogeneous PA gel, likely attributable to Joule-heating-inducted temperature rise.64,67 Here, we also observe similar time-varying electrophoretic mobility in the open-chamber device studied (Figure S3A), whereas a constant electrophoretic mobility is observed in our enclosed device configurations.

Leveraging the reduced conductance in the enclosed device, scPAGE performed in an enclosed configuration can support higher electric-field strengths (i.e., 150 vs 50 V/cm) with negligible temperature increases (Figure S3B). Adopting device and power-supply designs that allow operation at high electric-field strengths can increase the Peclet number, which indicates higher electrophoretic mass transfer compared with diffusive mass transport, resulting in higher scPAGE-separation performance for the same unit of time, as evidenced by both capillary and glass-microchip electrophoresis.

Reducing Joule heating reduces in-plane and out-of-plane diffusion, which enhances local protein concentrations (limit of detection) and reduces peak dispersion. Comparing the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of OVA* in the enclosed- and open-chamber devices (Figure 4B) shows an SNR decrease in all conditions over the PAGE-separation period (30 s). However, the SNR of OVA* in the enclosed device decreases more slowly, thus resulting in a ~3× higher SNR.

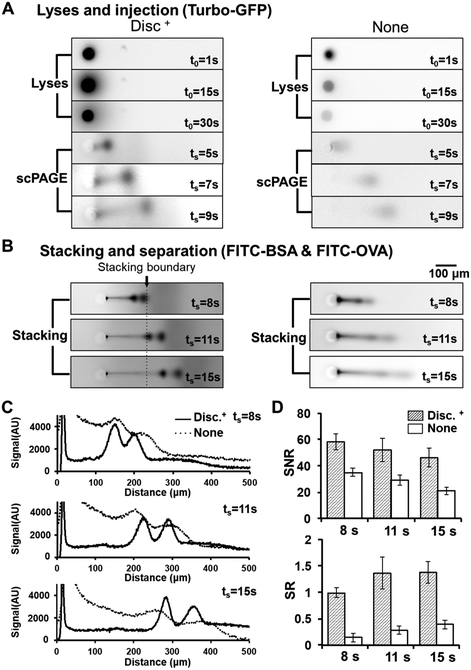

Disc+-PAGE Device Enhancing Separation Performance.

We next characterized scPAGE-separation performance in the device configurations under study (Figure 5A). To visualize and assess the separation process, including any stacking phenomenon at the stacking-gel interface, we used two fluorescently tagged proteins (BSA* and OVA*, Figure 5B) for PAGE separation. In the open-chamber device, with no control of Joule heating or injection dispersion, we observed peak widths of 78.6 ± 7.2 μm for BSA* and 79.8 ± 6.4 μm for OVA* at 20 s of elapsed separation time, which are 170 and 130% larger than the respective peak widths in the diffusion-mitigating design (Disc+, n = 5). We observe that the Disc+ device achieves baseline SR of the two ladder species in 14 s at a 380 μm separation distance (Figure 5C), whereas the open-chamber device with the uniform PA gel does not resolve the species.

Figure 5.

Injection dispersion impacts scPAGE SR and detection sensitivity. (A) Inverted grayscale epifluorescence micrographs of in situ U251-GFP cell lysis and subsequent PAGE of GFP in a dispersion-control device and in an open fluidic device. (B) Inverted grayscale epifluorescence micrographs of stacking of BSA* and OVA* in the Disc+ device, compared with those of a uniform 10% T gel in an open-chamber configuration (E = 50 V/cm). (C) Fluorescence intensity along the separation path in (B). (D) SNR of OVA* and SR of scPAGE in (B). Error bars are 1 standard deviation (n = 3).

We examined the impact of the stacking gel on protein-peak behavior, comparing the Disc+ and None configurations. We observed a protein-peak width that is nearly identical at t = 0s (Figure S4B). The peak width then decreases during the first ~10s of scPAGE in the Disc+ configuration (Figure S4B). On the basis of the micrographs (Figure 5B) and the area-under-the-curve (AUC) data (Figure S4C), we estimate that the OVA* band crosses the stacking interface at t = ~10 s of elapsed separation time. The observation is consistent with our expectation that a pore-size gradient exists and not a sharp step function.

We sought to further scrutinize the effect of the Disc+ conditions on diffusion and dispersion, so we opted to measure the apparent diffusion coefficient (Di′) of OVA*. First, we observed invariant diffusivity as OVA* electrophoresed along the scPAGE-separation axis in the enclosed device. We attribute the behavior to a constant and uniform local temperature. In the open-device configuration, however, we observed increased diffusion, arising due to Joule heating. Second, the initial decrease and the negative (aphysical) value of Di′ in the gel suggests the location and impact of the stacking-gel boundary at that position along the scPAGE-separation axis (Figure S4A). The stacking gel yielded a protein-peak width that was narrower than the initial injection-peak width (Figure S4B), which undergirds enhanced scPAGE-separation performance. The SR was improved from SR = 0.5 to SR = 1.5 for the BSA* (65 kDa) and OVA* (45 kDa) pair, yielding 2–3× improvement in SR with the Disc+ device configuration as compared with that of the open-chamber configuration (Figure 5D).

CONCLUSIONS

Open fluidic microdevices possess numerous advantages over devices with enclosed microchannel networks, such as ease of operation, potential for scale-up, and sample accessibility. Although open fluidic devices have proven useful for completing hundreds to thousands of concurrent single-cell PAGE separations, the open borders surrounding each separation lane provide numerous routes for diffusive protein loss from each single-cell lysate. In previous studies we had considered dispersion-control strategies, such as pore-gradient molecular-sieving gels,40 application of hydrogel lids for near-quiescent reagent transfer,29,41 and cell encapsulation,68 but we have not performed thorough methodical, quantitative performance comparisons. In this study, we maintained key characteristics of the open-fluidic-design principles, while introducing spatial control of analyte diffusion and dispersion. First, we considered in-microwell chemical lysis of a single cell. In this instance, we explored methods for fabricating a microwell ringed with high-gel-density sidewalls and a low-gel-density sample-injector region at the head of the scPAGE-separation lane. We also patterned a stacking gel in the separation axis to reduce injection dispersion and increase the resolving power of each 1 mm long separation lane. To reduce out-of-plane convection and diffusion, we encapsulated single-cells in microwells with selectively permeable molten agarose. Upon gelation, this agarose layer permitted reagent diffusion into the microwells for lysis, while limiting protein diffusion out of the microwell. Lastly, we reduced the cross-sectional area of the open system to reduce Joule-heating-induced sample dispersion and sample dilution. With these design modifications, we have improved separation resolution >3 times and SNR >2 times. This implies that we can extended the applicability of scPAGE to a wider range of the mammalian proteome that has lower expression levels or with closer molecular weights.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01CA203018, R21CA183679, and R33CA225296 (to A.E.H.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b03233.

Configuration of enclosed scPAGE device, enclosed-device-design principles to reduce Joule heating, and additional characterization of separation performance (PDF)

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Co-authors are co-inventors on University of California intellectual property that, upon licensing, may generate financial benefit for the co-inventors.

REFERENCES

- (1).Hanahan D; Weinberg RA Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Wei W; Shin YS; Ma C; Wang J; Elitas M; Fan R; Heath JR Genome Med. 2013, 5, 75–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Schulz KR; Danna EA; Krutzik PO; Nolan GP Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2012, 96, 8.17.1–8.17.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Stack EC; Wang C; Roman KA; Hoyt CC Methods 2014, 70, 46–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Perfetto SP; Chattopadhyay PK; Roederer M Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 4, 648–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Bandura DR; Baranov VI; Ornatsky OI; Antonov A; Kinach R; Lou X; Pavlov S; Vorobiev S; Dick JE; Tanner SD Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 6813–6822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Spitzer MH; Nolan GP Cell 2016, 165, 780–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Di Palma S; Bodenmiller B Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2015, 31, 122–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Yu ZTF; Guan H; Cheung MK; McHugh WM; Cornell TT; Shanley TP; Kurabayashi K; Fu J Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11339–11350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Mok J; Mindrinos MN; Davis RW; Javanmard M Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111, 2110–2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Thaitrong N; Charlermroj R; Himananto O; Seepiban C; Karoonuthaisiri N PLoS One 2013, 8, e83231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Fredriksson S; Gullberg M; Jarvius J; Olsson C; Pietras K; Gústafsdóttir SM; Ostman A; Landegren U Nat. Biotechnol. 2002, 20, 473–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Gullberg M; Gustafsdottir SM; Schallmeiner E; Jarvius J; Bjarnegard M; Betsholtz C; Landegren U; Fredriksson S Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004, 101, 8420–8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Lequin RM Clin. Chem. 2005, 51, 2415–2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Smith LM; Kelleher NL Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 186–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Zhao Y; Jensen ON Proteomics 2009, 9, 4632–4641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Kang CC; Yamauchi KA; Vlassakis J; Sinkala E; Duncombe TA; Herr AE Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 1508–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Laemmli UK Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Towbin H; Staehelin T; Gordon J Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1979, 76, 4350–4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Kurien BT; Scofield RH Protein Blotting and Detection: Methods and Protocols; Springer: New York, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Burnette S Anal. Biochem. 1981, 112, 195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).He M; Herr AE Nat. Protoc. 2010, 5, 1844–1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Jin S; Furtaw MD; Chen H; Lamb DT; Ferguson SA; Arvin NE; Dawod M; Kennedy RT Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 6703–6710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Ciaccio MF; Wagner JP; Chuu CP; Lauffenburger DA; Jones RB Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 148–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Gerver RE; Herr AE Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 10625–10632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Hughes AJ; Herr AE Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109, 21450–21455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Sinkala E; Sollier-Christen E; Renier C; Rosàs-Canyelles E; Che J; Heirich K; Duncombe TA; Vlassakis J; Yamauchi KA; Huang H; et al. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14622–14633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kim JJ; Sinkala E; Herr AE Lab Chip 2017, 17, 855–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Yamauchi KA; Herr AE Microsystems Nanoeng. 2017, 3, 16079–16087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Kennedy RT; Oates MD; Cooper BR; Nickerson B; Jorgenson JW Science 1989, 246, 57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Hu S; Zhang L; Cook LM; Dovichi NJ Electrophoresis 2001, 22, 3677–3682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Huang B; Wu H; Bhaya D; Grossman A; Granier S; Kobilka BK; Zare RN Science (Washington, DC, U. S.) 2007, 315, 81–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Collins a R. Mol. Biotechnol. 2004, 26, 249–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Olive PL; Banáth JP Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Wood DK; Weingeist DM; Bhatia SN; Engelward BP Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 10008–10013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Kang CC; Lin JMG; Xu Z; Kumar S; Herr AE Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 10429–10436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Chen Q; Wu J; Zhang Y; Lin Z; Lin JM Lab Chip 2012, 12, 5180–5185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Torres AJ; Contento RL; Gordo S; Wucherpfennig KW; Love JC Lab Chip 2013, 13, 90–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Hughes AJ; Spelke DP; Xu Z; Kang CC; Schaffer DV; Herr AE Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 749–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Duncombe TA; Kang CC; Maity S; Ward TM; Pegram MD; Murthy N; Herr AE Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 327–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Tentori AM; Yamauchi KA; Herr AE Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 12431–12435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Stepanenko AA; Kavsan VM Gene 2014, 540, 263–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Buxboim A; Rajagopal K; Brown AEX; Discher DEJ Phys.: Condens. Matter 2010, 22, 194116–194125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Gelfi C; Alloni A; de Besi P; Righetti PG J. Chromatogr. A 1992, 608, 343–348. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Hou C; Herr AE Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 3343–3351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Serwer P. Electrophoresis 1983, 4, 375–382. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Gu WY; Yao H; Vega AL; Flagler D Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2004, 32, 1710–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Johnson EM; Berk DA; Jain RK; Deen WM Biophys. J. 1995, 68, 1561–1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Lundberg P; Kuchel PW Magn. Reson. Med. 1997, 37, 44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Kwak S; Lafleur M Macromolecules 2003, 36, 3189–3195. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Stellwagen NC Electrophoresis 2009, 30, S188–S195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Clifton MJ Electrophoresis 1993, 14, 1284–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Vlassakis J; Herr AE Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 12787–12796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Ermakov SV; Jacobson SC; Ramsey JM Anal. Chem. 1998, 70, 4494–4504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Swinney K; Bornhop DJ Electrophoresis 2002, 23, 613–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Erickson D; Sinton D; Li D Lab Chip 2003, 3, 141–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Knox JH; McCormack KA Chromatographia 1994, 38, 207–214. [Google Scholar]

- (58).Dobry R; Finn RK Science 1958, 127, 697–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Probstein R Physicochemical Hydrodynamics: An Introduction; Wiley: New York, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- (60).Zarei M; Goharshadi EK; Ahmadzadeh H; Samiee S RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 88655–88665. [Google Scholar]

- (61).Rosenfeld T; Bercovici M Lab Chip 2014, 14, 4465–4474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Petersen NJ; Nikolajsen RPH; Mogensen KB; Kutter JP Electrophoresis 2004, 25, 253–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Nelson RJ; Paulus A; Cohen AS; Guttman A; Karger BL J. Chromatogr. A 1989, 480, 111–127. [Google Scholar]

- (64).Weast R CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, Student Edition; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- (65).Rogacs A; Santiago JG Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 5103–5113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Sorensen JA; Glass GE Anal. Chem. 1987, 59, 1594–1597. [Google Scholar]

- (67).Knox JH; Grant IH Chromatographia 1987, 24, 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- (68).Lin JMG; Kang CC; Zhou Y; Huang H; Herr AE; Kumar S Lab Chip 2018, 18, 371–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.