Abstract

Background

Cancer incidence rates for American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) populations vary by geographic region in the United States. The purpose of the present study is to examine cancer incidence rates and trends in the AI/AN population compared with the non-Hispanic white population in the United States for the years 2010–2015.

Methods

Cases diagnosed during 2010–2015 were identified from population-based cancer registries and linked with the Indian Health Service (IHS) patient registration databases to describe cancer incidence rates in non-Hispanic AI/AN persons compared to non-Hispanic whites (whites) living in IHS purchased/referred care delivery area counties. Age-adjusted rates were calculated for the 15 most common cancer sites, expressed per 100,000 per year. Incidence rates are presented overall as well as by region. Trends were estimated using joinpoint regression analyses.

Results

Lung and colorectal cancer incidence rates were nearly 20 percent to 2.5 times higher in AI/AN males and nearly 20 percent to nearly 3 times higher in AI/AN females compared to whites in the Northern Plains, Southern Plains, Pacific Coast and Alaska. Cancers of the liver, kidney and stomach were significantly higher in the AI/AN compared to the white population in all regions. We observed more significant decreases in cancer incidence rates in the white population compared to the AI/AN population.

Conclusions

Findings demonstrate the importance of examining cancer disparities between AI/AN and white populations. Disparities have widened for lung, female breast, and liver cancers.

Impact

These findings highlight opportunities for targeted public health interventions to reduce AI/AN cancer incidence.

Keywords: cancer incidence, American Indian, Alaska Native, trends, health disparity

Introduction

The most recent national data suggests that overall cancer incidence rates have decreased for men and remained stable for women in the United States in recent years [1]. These overall rates and trends, however, mask significant disparities in cancer incidence rates by race/ethnicity and by cancer types. For example, previous studies have shown substantially higher cancer incidence rates for the AI/AN population compared to whites that vary by geographic region and cancer type [2, 3]. Nationally aggregated data do not adequately describe important differences in cancer outcomes within the AI/AN population due to the observed regional variation in cancer incidence rates.

The purpose of the present study is to provide a comprehensive update of cancer incidence rates in the non-Hispanic AI/AN population in six geographic regions of the US. We also evaluated long-term trends in cancer incidence from 1999–2015 for the top 15 cancers in the AI/AN population. We utilized data from 2010–2015 from central cancer registries that have been linked with the IHS patient registration database using previously established and validated techniques that have been shown to reduce racial misclassification and provide accurate estimates of cancer incidence in the AI/AN population [4, 5]. By examining geographic variation and disparities in cancer incidence rates and changes in these rates over time, we can more accurately identify priority areas for cancer prevention and control in the AI/AN population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We utilized data from population-based registries, which participate in the National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) [6, 7]. For all cancers contained in this study, tumor histology, tumor behavior, and primary cancer site were classified according to the Third Edition of the International Classification of Disease for Oncology (ICD-O-3).

Incidence rates were presented for the most common cancer sites among the AI/AN populations nationwide. Site categories used were consistent with prevailing reporting standards [3, 6]. Lymphomas (ICD-O-3 histology codes 9590–9729) were presented as 2 separate categories (Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma) and were not included with tumors of specific anatomic sites. Mesothelioma (ICD-O-3 histology codes 9050–9055) and Kaposi sarcoma (ICD-O-3 histology code 9140) were not included with other tumors of specific anatomic sites. In situ and invasive bladder tumors were combined in a single category[8].Except for bladder cancers, analyses were restricted to malignant tumors (ICD-O-3 behavior code 3).

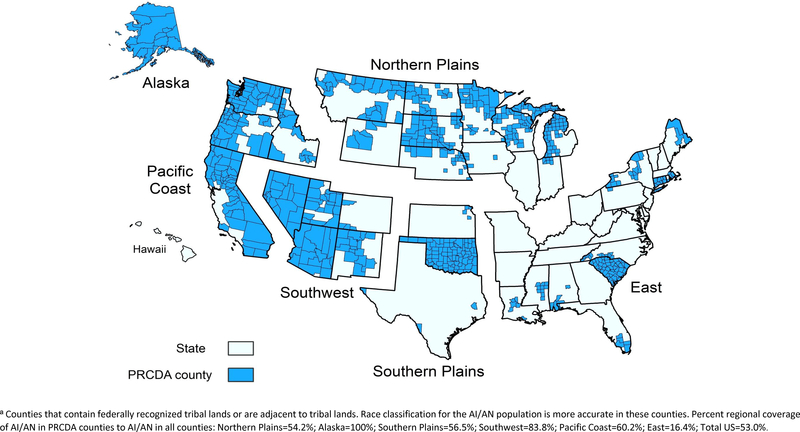

Previous data showed that racial misclassification can result in an underestimation of AI/AN cancer incidence rates [4, 5]. Efforts to reduce racial misclassification, and the process for conducting the IHS linkages, have been described elsewhere [5]. Briefly, all case records from each state were linked with the IHS registration database to identify AI/AN cases misclassified as non-AI/AN. For the purposes of all analyses in the present study, we restricted analyses to purchased/referred care delivery area (PRCDA) counties. These counties, previously called CHSDA (contract health service delivery area counties), contain or are located adjacent to federally recognized tribal lands. PRCDA counties also have higher proportions of AI/AN persons in relation to the total population than non-PRCDA counties. Approximately 53% of the US AI/AN population resides in PRCDA counties (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Geographic Regions and Purchased/Referred Care Delivery Areaa Counties by Region.

contains an image of the 6 geographic regions utilized for this manuscript as well as the counties within those regions that are Purchased/Referred Care Delivery Area (PRCDA) counties.

Linkages in these counties provide more accurate correction for racial misclassification of the AI/AN population, who are more likely to access IHS services in these areas [5].

In a previous report, the updated bridged intercensal population estimates overestimated AI/AN populations of Hispanic origin [9]. In the present study, we limited all analyses to non-Hispanic AI/AN populations to avoid underestimating rates in the AI/AN population[9]. Non-Hispanic white was chosen as the reference population. For conciseness, the term “non-Hispanic” was omitted when discussing both groups in this study.

Statistical Analysis

All cancer incidence rates are expressed per 100,000 population and were directly age-adjusted using 19 age groups to the 2000 US standard population using SEER*Stat software version 8.3.2 [10]. Using the age-adjusted incidence rates we calculated standardized rate-ratios (RRs) for the years 2010–2015 for the AI/AN population, using the white population as reference. Top 15 cancers were ranked for the AI/AN and white populations according to overall rank in the U.S., and rank by region. Information regarding regions and PRCDA counties are shown in Figure 1.

Long term trends (1999–2015) in age-adjusted cancer incidence rates were estimated by joinpoint regression including annual percent change (APC) and average annual percent change (AAPC) [11]. Total percent change in incidence rates between 1999 and 2015 were also calculated. Trends were estimated using software developed by the NCI (Joinpoint Regression Program version 4.3.10) [10, 12] Two-sided p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Incidence rates for the 15 most common cancers in AI/AN men are shown in Table 1. Prostate, lung, and colorectal cancer (CRC) were the most common cancers for both AI/AN and white men. Nationwide (i.e., all regions, combined) cancer incidence rates were significantly higher in the AI/AN population than in the white population for lung cancer (RR=1.12), CRC (RR=1.36), kidney cancer (RR=1.66), liver cancer (RR=2.30), stomach cancer (RR=1.83) and myeloma (RR=1.20). CRC rates were significantly higher among AI/ANs than whites in four of the six regions (RRs 1.18–2.44), the exceptions being the East (RR=0.90) and the Southwest (RR=1.10). Kidney cancer rates (RRs 1.31–2.14) were significantly higher in the AI/AN population in four of six regions, the exceptions being Alaska (RR=1.28) and the East (RR=0.81). Liver cancer rates (RRs 1.67–3.17) were significantly higher in the AI/AN versus white population across all regions. Rates of stomach cancer in AI/AN exceeded those of whites in all regions, though elevated RRs in the Pacific Coast and East regions did not achieve statistical significance. Nationwide, cancers of the prostate (RR=0.82), bladder (RR=0.53), non-Hodgkin lymphomas (RR=0.80), leukemias (RR=0.78) and melanomas of the skin (RR=0.29) were significantly lower in the overall AI/AN population compared to the white population. The latter patterns were also observed in most regions.

Table 1.

Leading Cancer Sites for American Indians/Alaska Nativesa compared to Non-Hispanic Whites for the United States, Males, All ages, PRCDA Counties, US, 2010–2015

| Overall | Northern Plains | Alaska | Southern Plains | Pacific Coast | East | Southwest | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Site | Rankb AI/AN (W) | AI/AN(W) Ratec | RRd | Rankb AI/AN (W) | AI/AN(W) Ratec | RRd | Rankb,AI/AN (W) | AI/AN(W) Ratec | RRd | Rankb AI/AN (W) | AI/AN(W) Ratec | RRd | Rankb AI/AN (W) | AI/AN(W) Ratec | RRd | Rankb AI/AN (W) | AI/AN(W) Ratec | RRd | Rankb AI/AN (W) | AI/AN (W) Ratec | RRd |

| Prostate | 1(1) | 86.7 (105.4) | 0.82e | 2(1) | 110.7(106.8) | 1.04 | 3(1) | 58.2(90.0) | 0.65e | 1(1) | 116.8 (99.2) | 1.18e | 1(1) | 81.3(105.8) | 0.77e | 1(1) | 71.4 (113.5) | 0.63e | 1(1) | 64.3(89.7) | 0.72e |

| Lung and Bronchus | 2(2) | 76.4 (68.2) | 1.12e | 1(2) | 122.4(68.9) | 1.77e | 1(2) | 118.4(60.1) | 1.97e | 2(2) | 115.9 (83.7) | 1.38e | 2(2) | 72.6(62.0) | 1.17e | 2(2) | 49.8 (76.4) | 0.65e | 4(2) | 24.3(56.9) | 0.43e |

| Colon and Rectum | 3(3) | 57.5(42.3) | 1.36e | 3(3) | 71.7(43.0) | 1.67e | 2(3) | 95.6(39.2) | 2.44e | 3(3) | 71.9(46.3) | 1.56e | 3(3) | 48.5(41.2) | 1.18e | 3(4) | 39.9(44.1) | 0.90 | 2(3) | 42.4(38.7) | 1.10 |

| Kidney and Renal Pelvis | 4(7) | 35.7 (21.5) | 1.66e | 4(7) | 46.4(21.7) | 2.14e | 5(5) | 27.2(21.3) | 1.28 | 4(6) | 43.2(23) | 1.87e | 5(7) | 27.4(20.9) | 1.31e | 5(7) | 18.8(23.1) | 0.81 | 3(7) | 37.2(18.7) | 1.99e |

| Liver and Intrahepatic Bile Duct | 5(11) | 22.9(10.0) | 2.30e | 6(15) | 24.3(7.7) | 3.17e | 9(11) | 17.3(10.4) | 1.67e | 8(11) | 22.0(9.9) | 2.24e | 4(11) | 27.9(11.1) | 2.53e | 4(11) | 18.8(10.8) | 1.74e | 5(11) | 21.3(8.3) | 2.58e |

| Urinary Bladder | 6(4) | 21.3(39.8) | 0.53e | 5(4) | 24.9(38.2) | 0.65e | 7(4) | 25.6(38.3) | 0.67e | 5(4) | 32.7(35.7) | 0.92 | 6(5) | 26.0(39.0) | 0.67e | 7(3) | 15.0(44.1) | 0.34e | 12(4) | 8.2(35.3) | 0.23e |

| Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | 7(6) | 18.7(23.3) | 0.80e | 7(6) | 20.8(24.1) | 0.86 | 8(6) | 20.1(20.6) | 0.98 | 6(7) | 28.0(22.0) | 1.27e | 7(6) | 20.7(23.7) | 0.87 | 10(6) | 9.4(24.6) | 0.38e | 8(6) | 11.7(19.4) | 0.60e |

| Oral Cavity and Pharynx | 8(9) | 17.7(18.4) | 0.96 | 8(9) | 20.0(17.1) | 1.17 | 6(8) | 25.7(15.2) | 1.69e | 7(8) | 23.7(20.4) | 1.16 | 8(8) | 19.5(19.1) | 1.02 | 6(9) | 15.8(19.3) | 0.82 | 11(9) | 9.1(16.0) | 0.57e |

| Leukemia | 9(8) | 14.4(18.5) | 0.78e | 9(8) | 16.8(18.9) | 0.89 | 11(9) | 14.6(14.4) | 1.02 | 10(9) | 18.5(17.3) | 1.07 | 9(9) | 15.1(18.2) | 0.83 | 8(8) | 12.9(20.0) | 0.64e | 9(8) | 9.8(16.1) | 0.61e |

| Pancreas | 10(10) | 14.1(14.1) | 1.00 | 11(10) | 14.1(13.9) | 1.01 | 10(10) | 15.3(13.1) | 1.16 | 11(10) | 16.1(13.0) | 1.24e | 10(10) | 15.0(14.0) | 1.07 | 9(10) | 10.0(15.3) | 0.65e | 7(10) | 12.6(12.9) | 0.98 |

| Stomach | 11(15) | 13.9(7.6) | 1.83e | 10(14) | 15.4 (7.8) | 1.97e | 4(14) | 28.2(7.2) | 3.93e | 12(14) | 11.4(6.9) | 1.64e | 13(14) | 8.5 (7.5) | 1.13 | 11(15) | 9.4(8.6) | 1.10 | 6(16) | 17.0(6.0) | 2.84e |

| Melanoma of the Skin | 12(5) | 10.0(34.1) | 0.29e | 15(5) | 8.7(27.1) | 0.32e | 18(7) | 3.8(18.7) | 0.20e | 9(5) | 19.8(27) | 0.73e | 11(4) | 10.4(39.5) | 0.26e | 12(5) | 6.4(35.1) | 0.18e | 15(5) | 5.3(31.8) | 0.17e |

| Myeloma | 13(16) | 8.6(7.2) | 1.20e | 14(13) | 10.4(7.8) | 1.34 | 17(16) | 6.6(5.6) | 1.18 | 13(15) | 9.9(6.6) | 1.50e | 16(16) | 6.5(7.2) | 0.91 | 15(16) | 4.5(7.8) | 0.57 | 10(17) | 9.8(5.8) | 1.68e |

| Esophagus | 14(13) | 8.1(8.4) | 0.96 | 13(11) | 10.9(8.9) | 1.23 | 12(12) | 12.2(9) | 1.36 | 14(13) | 9.4(7.7) | 1.23 | 14(13) | 7.7 (8.4) | 0.92 | 14(14) | 5.4(8.7) | 0.63 | 14(14) | 5.8(7.9) | 0.73e |

| Testis | 15(17) | 6.9(7.0) | 0.98 | 16(16) | 7.4(7.3) | 1.01 | 13(15) | 8.5(6.8) | 1.25 | 18(18) | 5.8(5.6) | 1.04 | 12(15) | 8.5 (7.4) | 1.15 | 13(17) | 5.6(7.2) | 0.78 | 13(15) | 6.4(6.2) | 1.03 |

Source: Cancer registries in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) and/or the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program (SEER)

PRCDA indicates Purchased/Referred Care Delivery Areas; AI/AN: American Indians/Alaska Natives; W: non-Hispanic white.

AI/AN race is reported by NPCR and SEER registries or through linkage with the IHS patient registration database. Includes only AI/AN of non-Hispanic origin.

Rank based on rates. AI/AN (white)

Rates are per 100,000 persons and are age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population (19 age groups - Census P25–1130).

Rate ratios (RR) are AI/AN versus White and are calculated in SEER*Stat prior to rounding of rates and may not equal RR calculated from rates presented in table.

Indicates RR is statistically significant (p<0.05).

Years of data and registries used: 1999–2015 (48 states): AK*, AL*, AZ*, CA*, CO*, CT*, DE, DC, FL*, GA, HI, IA*, ID*, IL, IN*, KS*, KY, LA*, MA*, MD, ME*, MI*, MN*, MO, MT*, ND* NE*, NH, NJ, NM*, NV*, NY*, NC*, OH, OK*, OR*, PA*, RI*, SC*, TX*, TN, UT*, VT, VA, WA*, WI*, WV, WY*; 2000–2015: AR, SD*; 2003–2015: MS*. *States with at least one county designated as PRCDA.

Percent regional coverage of AI/AN in PRCDA counties to AI/AN in all counties: Northern Plains=54.2%; Alaska=100%; Southern Plains=56.5%; Southwest=83.8%; Pacific Coast=60.2%; East=16.4%; Total US=53.0%.

In women, breast, lung, CRC and uterus were the top four cancers for both AI/AN and white populations (Table 2). AI/AN females had significantly higher rates of lung cancer (RR=1.06), CRC (RR=1.37), kidney cancer (RR =1.85), cervical cancer (RR =1.69), liver cancer (RR=3.08) and stomach cancer (RR =2.29). Incidence rates of kidney cancer (RRs 1.51–2.21) were significantly higher in AI/ANs than whites in all regions except the East. Rates of CRC (RR=1.37–2.87) were higher in AI/ANs than whites in all regions except the East and Southwest. Cervical cancer incidence rates were higher in AI/ANs than whites in all regions but only reached statistical significance in the Northern Plains (RR=2.04), Alaska (RR=1.65), Southern Plains (RR=1.65) and Pacific Coast (RR=2.19). Liver cancer incidence rates were significantly higher across all regions for AI/AN females, with rates 2 to 4 times higher than the white population. Breast cancer (RR=0.87), thyroid cancer (RR=0.80) and leukemias (RR=0.91) were significantly lower in AI/ANs than whites nationwide, though these patterns varied by region. Rates for melanomas of the skin were significantly lower in the AI/ANs versus whites nationwide (RR=0.30) and in each of the regions.

Table 2.

Leading Cancer Sites for American Indians/Alaska Nativesa compared to Non-Hispanic Whites for the United States, Females, All ages, PRCDA Counties, US, 2010–2015

| Overall | Northern Plains | Alaska | Southern Plains | Pacific Coast | East | Southwest | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Site | Rankb AI/AN (W) | AI/AN(W) Ratec | RRd | Rankb AI/AN (W) | AI/AN(W) Ratec | RRd | Rankb AI/AN (W) | AI/AN(W) Ratec | RRd | Rankb AI/AN (W) | AI/AN(W) Ratec | RRd | Rankb AI/AN (W) | AI/AN(W) Ratec | RRd | Rankb AI/AN (W) | AI/AN(W) Ratec | RRd | Rankb AI/AN (W) | AI/AN (W) Ratec | RRd |

| Female Breast | 1(1) | 112.5 (129.9) | 0.87e | 1(1) | 128.4 (122.7) | 1.05 | 1(1) | 156.2 (124.1) | 1.26e | 1(1) | 151.1 (116.1) | 1.30e | 1(1) | 124.3 (133.9) | 0.93e | 1(1) | 83.6 (136.4) | 0.61e | 1(1) | 68.3 (120.6) | 0.57e |

| Lung and Bronchus | 2(2) | 58.6(55.4) | 1.06e | 2(2) | 104.0 (53.9) | 1.93e | 3(2) | 73.5(51.8) | 1.42e | 2(2) | 87.3(56.9) | 1.53e | 2(2) | 63.0(52.7) | 1.20e | 2(2) | 42.0(61.5) | 0.68e | 6(2) | 15.9(48.7) | 0.33e |

| Colon and Rectum | 3(3) | 45.4(33.1) | 1.37e | 3(3) | 51.3 (33.9) | 1.51e | 2(3) | 92.8(32.3) | 2.87e | 3(3) | 57.9(34.8) | 1.66e | 3(3) | 44.6(32.5) | 1.37e | 3(3) | 30.2(34) | 0.89 | 2(3) | 28.8(30.6) | 0.94 |

| Corpus and Uterus, NOS | 4(4) | 26.7(25.9) | 1.03 | 4(4) | 25.2 (28.4) | 0.89 | 6(4) | 18.2(26.5) | 0.68e | 4(4) | 29.4(21.5) | 1.37e | 4(5) | 29.3(25.9) | 1.13 | 4(4) | 19.0(27.3) | 0.70e | 3(5) | 27.7(22.1) | 1.25e |

| Kidney and Renal Pelvis | 5(11) | 20.0(10.8) | 1.85e | 5(9) | 23.4(11.1) | 2.11e | 5(10) | 21.6(10.9) | 1.98e | 5(8) | 27.9(12.6) | 2.21e | 7(11) | 15.5(10.3) | 1.51e | 5(12) | 12.6(11.3) | 1.12 | 5(11) | 17.1(9.5) | 1.81e |

| Thyroid | 6(5) | 17.9(22.5) | 0.80e | 7(6) | 16.0(19.3) | 0.83e | 4(6) | 24.6(15.6) | 1.58e | 6(5) | 21.0(18.9) | 1.1 | 5(6) | 18.3(20.1) | 0.91 | 7(5) | 9.2(25.7) | 0.36e | 4(4) | 17.3(25.8) | 0.67e |

| Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | 7(7) | 15.0(15.9) | 0.95 | 6(7) | 16.4(16.6) | 0.99 | 8(7) | 14.5(14.4) | 1.01 | 7(7) | 19.5(14.6) | 1.34e | 6(7) | 17.1(15.7) | 1.09 | 6(7) | 10.2(16.8) | 0.60e | 9(7) | 11.1(13.7) | 0.81e |

| Ovary | 8(8) | 12.6(11.8) | 1.06 | 8(8) | 12.8(11.1) | 1.15 | 12(8) | 8.8(12.6) | 0.7 | 9(9) | 15(11.5) | 1.30e | 10(8) | 10.7(12.2) | 0.88 | 15(8) | 6.3(12.0) | 0.52e | 7(8) | 14.4(11.4) | 1.26e |

| Pancreas | 9(10) | 11.6(10.8) | 1.07 | 10(11) | 12.5(10.6) | 1.18 | 9(9) | 13.8(11.1) | 1.25 | 8(11) | 15.7(10.0) | 1.58e | 13(10) | 10.2(10.7) | 0.95 | 10(10) | 7.2(11.4) | 0.63e | 10(9) | 9.6(9.8) | 0.99 |

| Cervix | 10(14) | 11.2(6.6) | 1.69e | 9(14) | 12.7(6.2) | 2.04e | 11(13) | 10.4(6.3) | 1.65e | 10(12) | 13.9(8.4) | 1.65e | 8(14) | 15.1(6.9) | 2.19e | 9(14) | 7.8(6.4) | 1.21 | 13(13) | 7.2(6.3) | 1.14 |

| Liver and Intrahepatic Bile Duct | 11(17) | 10.5(3.4) | 3.08e | 12(18) | 10.5(3.1) | 3.43e | 16(17) | 6.5(3.2) | 2.02e | 12(17) | 9.5(3.5) | 2.71e | 9(17) | 10.8(3.7) | 2.90e | 11(18) | 7.2(3.3) | 2.20e | 8(17) | 12.5(3.4) | 3.71e |

| Leukemias | 12(9) | 10.0(11.0) | 0.91e | 11(10) | 12.2(11.0) | 1.11 | 14(12) | 8.0(10.2) | 0.78 | 11(10) | 13.2(10.8) | 1.23e | 11(9) | 10.5(10.9) | 0.97 | 12(9) | 6.9(11.8) | 0.59e | 12(10) | 7.6(9.8) | 0.77e |

| Stomach | 13(18) | 7.5(3.3) | 2.29e | 15(17) | 6.2(3.1) | 1.98e | 7(18) | 16.3(2.9) | 5.55e | 16(18) | 6.0(2.8) | 2.14e | 17(18) | 4.8(3.1) | 1.56e | 8(17) | 8.1(3.9) | 2.08e | 11(18) | 9.1(2.7) | 3.36e |

| Oral Cavity and Pharynx | 14(13) | 6.9(6.8) | 1.02 | 13(13) | 10.5(6.7) | 1.55e | 10(15) | 13.7(5.5) | 2.49e | 15(14) | 6.3(6.9) | 0.9 | 14(13) | 8.4(7.0) | 1.21 | 14(13) | 6.8(7.2) | 0.93 | 17(15) | 3.4(5.6) | 0.62e |

| Melanomas of the Skin | 15(6) | 6.7(22.4) | 0.30e | 19(5) | 3.8(20.2) | 0.19e | 15(5) | 7.4(16.0) | 0.46e | 13(6) | 9.1(15.4) | 0.59e | 12(4) | 10.3(26.8) | 0.38e | 13(6) | 6.8(22.3) | 0.31e | 16(6) | 4.0(18.8) | 0.21e |

Source: Cancer registries in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) and/or the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program (SEER)

PRCDA indicates Purchased/Referred Care Delivery Areas; AI/AN: American Indians/Alaska Natives; W: non-Hispanic white.

AI/AN race is reported by NPCR and SEER registries or through linkage with the IHS patient registration database. Includes only AI/AN of non-Hispanic origin.

Rank based on rates. AI/AN (white)

Rates are per 100,000 persons and are age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population (19 age groups - Census P25–1130).

Rate ratios (RR) are AI/AN versus White and are calculated in SEER*Stat prior to rounding of rates and may not equal RR calculated from rates presented in table.

Indicates RR is statistically significant (p<0.05).

Years of data and registries used: 1999–2015 (48 states): AK*, AL*, AZ*, CA*, CO*, CT*, DE, DC, FL*, GA, HI, IA*, ID*, IL, IN*, KS*, KY, LA*, MA*, MD, ME*, MI*, MN*, MO, MT*, ND* NE*, NH, NJ, NM*, NV*, NY*, NC*, OH, OK*, OR*, PA*, RI*, SC*, TX*, TN, UT*, VT, VA, WA*, WI*, WV, WY*; 2000–2015: AR, SD*; 2003–2015: MS*. *States with at least one county designated as PRCDA.

Percent regional coverage of AI/AN in PRCDA counties to AI/AN in all counties: Northern Plains=54.2%; Alaska=100%; Southern Plains=56.5%; Southwest=83.8%; Pacific Coast=60.2%; East=16.4%; Total US=53.0%.

Significant decreases in rates for lung, colorectal, prostate and stomach cancers were documented in both AI/AN and white males during the study period, nationwide (Table 3, Supplemental Table 1 and Table 2). The overall decreases in incidence rates were larger for lung and colorectal cancers in the white population compared to the AI/AN population (Figure 2A, Supplemental Table 2). Significant increases for both kidney (AAPC: 2.4) and liver cancers (AAPC :3.3) were also observed for AI/AN, and white males. Liver cancer incidence rates increased by 112% in AI/AN males compared to 73% in white males.

Table 3:

Average Annual Percent Change (AAPCa) for American Indian/Alaska Native Persons Compared With Non-Hispanic White Persons, by Sex: PRCDA Counties, United States, 1999–2015

| Male |

Female |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI/AN AAPC | White AAPC | AI/AN AAPC | White AAPC | |

| Cancer Sites | ||||

| All sites | −0.4 | −1.4* | 0.5 | −0.3 |

| Lung | −0.3 | −2.3* | −0.6* | 0.0 |

| CRC | −1.1* | −3.3* | −0.5 | −2.4* |

| Prostate | −4.0* | −4.0* | NA | NA |

| Breast | NA | NA | 0.9* | −0.6 |

| Kidney | 2.4* | 1.8* | 1.6* | 1.7* |

| Liver | 3.3* | 3.5* | 4.2* | 2.5* |

| Stomach | −1.6* | −1.5* | −1.3 | −1.5 |

| Cervical | NA | NA | 0.0 | −1.2* |

Note: AI/AN= American Indian Alaska Native; AAPC= average annual percent change; PRCDA=Purchased/Referred Care Delivery Areas.

Joinpoint Analyses with up to 3 joinpoints are based on rates per 100,000 persons and were age-adjusted to the 2000

US standard population ( 11 age groups; census P25–1130); Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 4.0.1. January 2013; Statistical Research and Applications Branch, National Cancer Institute

Bethesda, MD. Analyses are limited to persons of non-Hispanic origin. AI/AN race is reported through linkage with the Indian Health Service patient registration database.

APC is based on rates that were age-adjusted to the 2000 US standard population (11 age groups, Census P25–1130).

2-sided P<0.05

Figure 2: Total Percent Change in Cancer Incidence Rates, AI/AN versus White, US PRCDA 1999–2015, by Cancer Site and Sex.

contains an image of graphs representing the total percent change in cancer incidence rates between the years 1999–2015. Figure A shows total percent change for males. Figure B shows total percent change for females.

A modest, but significant, decrease in lung cancer incidence was observed between 1999 and 2015 in AI/AN females (AAPC: −0.6) (Table 3). Significant increases were documented for several cancers in AI/AN women during this time period, including kidney (AAPC: 1.6):, liver (AAPC: 4.2), and female breast (AAPC: 0.9) (Supplemental Table 1 and Table 3). Breast cancer incidence rates increased by 8% for the total time period in AI/AN females, but decreased by 10% in white females (Figure 2B, Supplemental Table 2). Liver cancer incidence rates increased by 107% for AI/AN females and 47% for white females. Trends in cervical cancer incidence rates have remained stagnant for the AI/AN population ( AAPC:0) but decreased significantly for white females (AAPC: −1.2). Trends in colorectal cancer and stomach cancer had similar patterns in AI/AN and white females.

DISCUSSION

The data described here provide updated information regarding cancer disparities between the AI/AN and white populations [3]. Consistent with previous findings, these data indicate substantial regional variation in cancer incidence rates for the AI/AN population [3, 5]. This variation could be due to documented regional differences in important cancer risk factors including tobacco and alcohol use, obesity, diet, physical activity, diabetes, infectious diseases such as viral hepatitis C and B (HCV, HBV) and human papillomavirus (HPV), and other environmental, behavioral or socioeconomic factors that impact cancer risk [3, 13–15].

Breast cancers have the highest incidence rates in both AI/AN and white women. Although overall breast cancer rates were lower in the AI/AN compared to the white population, regional variation in incidence may reflect differences in environmental, behavioral and reproductive breast cancer risk factors and a need to better understand and address the causes of breast cancer among AI/AN women. In AI/AN women, breast cancer incidence rates have increased significantly in the last 15 years. Some of this increase could be related to increasing rates of screening in the population. According to Government Performance Results Act (GPRA) measures, breast cancer screening has increased for AI/AN women between 2008–2016 [16] despite remaining below Healthy People 2020 targets and screening rates for other racial/ethnic subgroups [17].

Despite ongoing public health efforts to reduce smoking behaviors and tobacco use, lung cancer remains the second leading cause of cancer for both the AI/AN and white populations. Overall, AI/AN populations have the highest prevalence of cigarette smoking of any population in the United States [18, 19]. There is an important distinction between habitual commercial tobacco use and ceremonial/traditional tobacco use in the AI/AN population that should be considered when interpreting this data [3, 18]. Previous studies show that the greatest burden of lung cancer is found in regions with the highest prevalence of commercial tobacco use [18]. A new GPRA measure was established in 2006 to track tobacco cessation service delivery among current smokers within the IHS and tribal programs. While this measure has progressively improved each year, from the baseline of 12% in 2006 to over 50% in 2016 [16], expanding tobacco control strategies remains an important aspect of cancer prevention in the AI/AN population.

Colorectal cancer incidence remained significantly higher in the AI/AN compared to white population. This excess risk could be related to a variety of factors such as lack of endoscopic services for screening and follow-up at most IHS and tribal facilities and underfunded referral systems [20]. Fecal occult blood testing is the primary colorectal cancer screening modality within IHS facilities, and unlike endoscopic screening, this modality does not involve removal of precancerous polyps [15, 20]. The data also show regional disparities within the AI/AN population, with a higher burden of colorectal cancer for the AI/AN population in areas such as Alaska and the Northern Plains, where the incidence rates are nearly two times higher than other regions such as the Southwest. Some of this regional variation within the AI/AN population could be due to differences in diet, specifically differences in intake of animal fats and fruits and vegetables [14] and consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages that contribute to obesity. Other risk factors that might explain differences in cancer incidence include alcohol use and tobacco smoking [21]. In addition to these behavioral risk factors diabetes, access to care [15] and even variations in the gut microbiome can potentially impact cancer risk [13]. While we observed a modest decrease in rates of colorectal cancer for AI/AN males, the decrease was much smaller in AI/AN females. Continued efforts to promote CRC screening and reduce known risk factors are critical for improving these trends over time.

Incidence rates of liver, kidney, and stomach cancer were higher in the AI/AN compared to white population across most regions and these increases are consistent with previous findings [2, 22, 23]. Liver cancer incidence rates for the AI/AN population between 1999–2009 were described in a recent publication [22]. The present study confirms increasing liver cancer incidence for AI/ANs as well as whites, with little change observed in disparities between the two populations. Increases in HCV and obesity prevalence may be contributing to the rapid increase in liver cancer incidence rates across the U.S., in particular for the AI/AN population, despite the dramatic decreases observed in childhood liver cancers following the advent of the hepatitis B vaccine [24].

The present study suggests higher incidence rates of kidney cancer for the AI/AN compared to white populations, and confirms the increase in incidence rates through 2009. Our data show a nonsignificant decrease in kidney cancer rates in more recent years. Previous analyses reported that rates of kidney cancer in the AI/AN population had exceeded those in the white population [23, 25]. The present study suggests that while overall rates might be decreasing, the disparities between the AI/AN and white population are growing for this cancer. Only a few personal risk factors for kidney cancer are known, including obesity, smoking, and hypertension [21, 23]. These factors are unlikely to fully explain the observed variation in kidney cancer incidence rates for the AI/AN population. Therefore, increased efforts to understand and mitigate the impact of other risk factors, including occupational exposures, access to care, and socioeconomic status should also be made to reduce disparities in kidney cancer incidence rates in this population.

While the burden of gastric cancer is low in the U.S. overall, the present study highlights a disproportionate burden of gastric cancer in the AI/AN population, particularly in the Southwest and Alaska. The evidence of a causal link between H.pylori infection and gastric cancer has provided an important understanding of variation in gastric cancer incidence rates worldwide [26, 27]. Most data regarding H.pylori prevalence in the AI/AN population focuses on Alaska Natives (AN) where the burden of H.pylori infection is particularly high (prevalence ranging from 64%−81%) [28]. Therefore, further efforts are necessary to understand the factors driving the disproportionate burden of gastric cancer in the American Indian population.

Cancer control programs promote cancer awareness, prevention and surveillance activities in the AI/AN population. At the national level, the IHS continues to provide direct clinical and preventive services through its network of direct services clinics as well as through IHS funded self-governance tribal health facilities. The CDC National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) has provided breast cancer screening for underserved populations since 1991. In 2011–2012, nearly 33% of eligible AI/AN women were screened via NBCCEDP (compared to 8.7–12.2% for other races/ethnicities) [29]. In addition to these efforts, the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion’s “Good Health and Wellness in Indian Country” aims to reduce prevalence of chronic diseases and their risk factors. These risk factors also play an important role in cancer prevention [23].

The CDC’s Division of Cancer Prevention and Control (DCPC) also supported projects in Alaska, Minnesota and Arizona to increase colorectal cancer screening in the AI/AN population. Collaboration between CDC and the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC) has aided in the development and implementation of screening navigator services focused on high risk individuals [30]. The American Indian Cancer Foundation has also collaborated with the CDC/DCPC to determine the CRC screening capacity in health care facilities serving the Northern Plains [31]. In the Southwest, the Albuquerque Area Indian Health Board collaborated with the CDC to develop a Tribal colorectal cancer health program in which Community Health Representatives (CHRs) aided in development of patient education resources to increase awareness regarding CRC screening[32]. All of these efforts have been initiated to address AI/AN populations at high risk for colorectal cancer. The present study shows evidence of decreasing trends in CRC for the AI/AN population overall, more so for males. These data suggest that targeted efforts at screening may be contributing to reduced CRC incidence rates for this population.

Recent efforts have also been initiated to reduce rates of liver cancer in the AI/AN population. The Cherokee Nation Health Services (CNHS) implemented a tribal HCV testing policy in 2012 [33]. As a part of this policy, the CNHS has added a reminder in the electronic health record for clinical decision support for primary care physicians. Between the years 2012 and 2015, there was a nearly 14% increase in the number of eligible individuals receiving HCV screening and 90% of the individuals subsequently treated after HCV diagnosis achieved a cure [33]. Active collaborations between IHS and Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes), established in March of 2013, have improved HCV-related care for the AI/AN population [34]. Project ECHO implements teleconsulting and telementoring partnerships between specialists and providers in rural and underserved communities [35]. The present study indicates an increasing burden of liver cancer for the AI/AN population overall. While the targeted programs described here have made great improvements in access to care and preventive services, specifically in relation to viral hepatitis, this study indicates that broader intervention and prevention strategies are still needed to address disparities in liver cancer incidence and risk factors in the AI/AN population.

The present study has limitations. Efforts to reduce racial misclassification through linkage with the IHS patient registration database only addressed misclassification for those individuals who had accessed services through the Indian Health System. Therefore, racial misclassification for members of non-federally recognized tribes or individuals that have not previously accessed services through IHS remained unchanged. Individuals living in urban, non-PRCDA areas are under-represented in these data and therefore these results may not be generalizable to all AI/AN in the United States or in individual IHS regions. There is also heterogeneity within the AI/AN population that may be masked by analyses conducted on a regional level. However, more granular data is not available for analyses. The restriction of the analyses to non-Hispanic AI/ANs was due to difficulties in obtaining accurate population estimates. While this exclusion reduced the overall AI/AN incidence rates by less than 5%, this exclusion may disproportionally impact rates for some states and regions.

This update on cancer incidence rates and trends broadens existing knowledge regarding cancer burden in the AI/AN population. While many of the findings are consistent with previous reports [3], the present analyses highlight growing disparities and excess burden for certain cancers such as kidney [23, 25] and liver [22] cancer. Regional variation, growing racial disparities, and changes in cancer incidence trends over time, reflect potentially missed opportunities to address environmental and socioeconomic determinants of cancer risk in AI/AN communities.

Persistent disparities in cancer incidence for this population suggest that efforts to develop targeted interventions to reduce the burden of preventable and/or treatable disease need to be continued and expanded. A comprehensive approach would address the many factors that contribute to health disparities, including historical trauma and the social determinants of health. Culturally congruent, community-based interventions are necessary to support healthy behaviors such as reduced consumption of recreational tobacco products, alcohol, and sweetened beverages and increased physical activity. Strategies to decrease exposures to known carcinogens and increase access to preventive health services, healthcare utilization and chronic disease management, and cancer screening can help reduce cancer disparities in the AI/AN population

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Footnotes

No conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Because the study did not involve human participants, institutional review board approval was not required.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cronin KA, Lake AJ, Scott S, et al. (2018) Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, part I: National cancer statistics. Cancer. 124: 2785–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiggins CL, Espey DK, Wingo PA, et al. (2008) Cancer among American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States, 1999–2004. Cancer. 113: 1142–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White MC, Espey DK, Swan J, Wiggins CL, Eheman C, Kaur JS. (2014) Disparities in cancer mortality and incidence among American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States. Am J Public Health. 104 Suppl 3: S377–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jim MA, Arias E, Seneca DS, et al. (2014) Racial misclassification of American Indians and Alaska Natives by Indian Health Service Contract Health Service Delivery Area. Am J Public Health. 104 Suppl 3: S295–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Espey DK, Wiggins CL, Jim MA, Miller BA, Johnson CJ, Becker TM. (2008) Methods for improving cancer surveillance data in American Indian and Alaska Native populations. Cancer. 113: 1120–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hankey BF, Ries LA, Edwards BK. (1999) The surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program: a national resource. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 8: 1117–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thoburn KK, German RR, Lewis M, Nichols PJ, Ahmed F, Jackson-Thompson J. (2007) Case completeness and data accuracy in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries. Cancer. 109: 1607–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynch CF, Platz CE, Jones MP, Gazzaniga JM. (1991) Cancer registry problems in classifying invasive bladder cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 83: 429–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arias E, Schauman WS, Eschbach K, Sorlie PD, Backlund E. (2008) The validity of race and Hispanic origin reporting on death certificates in the United States. Vital Health Stat 2. 1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henderson JA, Espey DK, Jim MA, German RR, Shaw KM, Hoffman RM. (2008) Prostate cancer incidence among American Indian and Alaska Native men, US, 1999–2004. Cancer. 113: 1203–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tiwari RC, Clegg LX, Zou Z. (2006) Efficient interval estimation for age-adjusted cancer rates. Stat Methods Med Res. 15: 547–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. (2000) Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 19: 335–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahn J, Sinha R, Pei Z, et al. (2013) Human gut microbiome and risk for colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 105: 1907–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson JS, Nobmann ED, Asay E, Lanier AP. (2009) Dietary intake of Alaska Native people in two regions and implications for health: the Alaska Native Dietary and Subsistence Food Assessment Project. Int J Circumpolar Health. 68: 109–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perdue DG, Haverkamp D, Perkins C, Daley CM, Provost E. (2014) Geographic variation in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality, age of onset, and stage at diagnosis among American Indian and Alaska Native people, 1990–2009. Am J Public Health. 104 Suppl 3: S404–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults—United States, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2018;67(2):53–9 [accessed 2018 Oct 30]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White A, Richardson LC, Li C, Ekwueme DU, Kaur JS. (2014) Breast cancer mortality among American Indian and Alaska Native women, 1990–2009. Am J Public Health. 104 Suppl 3: S432–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hankey BF, Feuer EJ, Clegg LX, et al. (1999) Cancer surveillance series: interpreting trends in prostate cancer--part I: Evidence of the effects of screening in recent prostate cancer incidence, mortality, and survival rates. J Natl Cancer Inst. 91: 1017–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Odani S, Armour BS, Graffunder CM, Garrett BE, Agaku IT. (2017) Prevalence and Disparities in Tobacco Product Use Among American Indians/Alaska Natives - United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 66: 1374–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Day LW, Espey DK, Madden E, Segal M, Terdiman JP. (2011) Screening prevalence and incidence of colorectal cancer among American Indian/Alaskan natives in the Indian Health Service. Dig Dis Sci. 56: 2104–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cobb N, Espey D, King J. (2014) Health behaviors and risk factors among American Indians and Alaska Natives, 2000–2010. Am J Public Health. 104 Suppl 3: S481–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melkonian SC, Jim MA, Reilley B, et al. (2018) Incidence of primary liver cancer in American Indians and Alaska Natives, US, 1999–2009. Cancer Causes Control. 29: 833–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Weir HK, Jim MA, King SM, Wilson R, Master VA. (2014) Kidney cancer incidence and mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States, 1990–2009. Am J Public Health. 104 Suppl 3: S396–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McMahon BJ, Bulkow LR, Singleton RJ, et al. (2011) Elimination of hepatocellular carcinoma and acute hepatitis B in children 25 years after a hepatitis B newborn and catch-up immunization program. Hepatology. 54: 801–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson RT, Richardson LC, Kelly JJ, Kaur J, Jim MA, Lanier AP. (2008) Cancers of the urinary tract among American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States, 1999–2004. Cancer. 113: 1213–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stolte M, Meining A. (1998) Helicobacter pylori and Gastric Cancer. Oncologist. 3: 124–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wroblewski LE, Peek RM Jr., Wilson KT. (2010) Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: factors that modulate disease risk. Clin Microbiol Rev. 23: 713–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McMahon BJ, Bruce MG, Koch A, et al. (2016) The diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in Arctic regions with a high prevalence of infection: Expert Commentary. Epidemiol Infect. 144: 225–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howard DH, Tangka FK, Royalty J, et al. (2015) Breast cancer screening of underserved women in the USA: results from the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program, 1998–2012. Cancer Causes Control. 26: 657–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Redwood D, Provost E, Perdue D, Haverkamp D, Espey D. (2012) The last frontier: innovative efforts to reduce colorectal cancer disparities among the remote Alaska Native population. Gastrointest Endosc. 75: 474–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nadeau M, Walaszek A, Perdue DG, Rhodes KL, Haverkamp D, Forster J. (2016) Influences and Practices in Colorectal Cancer Screening Among Health Care Providers Serving Northern Plains American Indians, 2011–2012. Prev Chronic Dis. 13: E167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tribal Colorectal Health Program. Albuquerque Area Southwest Tribal Epidemiology Center. www.aastec.net/services-programs/tchp/.

- 33.Mera J, Vellozzi C, Hariri S, et al. (2016) Identification and Clinical Management of Persons with Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection - Cherokee Nation, 2012–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 65: 461–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pindyck T, Kalishman S, Flatow-Trujillo L, Thornton K. (2015) Treating hepatitis C in American Indians/Alaskan Natives: A survey of Project ECHO((R)) (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) utilization by Indian Health Service providers. SAGE Open Med. 3: 2050312115612805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arora S, Kalishman S, Thornton K, et al. (2016) Project ECHO (Project Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes): A National and Global Model for Continuing Professional Development. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 36 Suppl 1: S48–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.