Abstract

Objective:

To develop recommendations for the screening, monitoring, and treatment of uveitis in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA).

Methods:

Pediatric rheumatologists, ophthalmologists with expertise in uveitis, patient representatives, and methodologists generated key clinical questions to be addressed by this guideline. This was followed by a systematic literature review and rating of the available evidence according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology. A group consensus process was used to compose the final recommendations and grade their strength as conditional or strong.

Results:

Due to limitations of the literature with very low quality of evidence, recommendations were formulated on the basis of available evidence and a consensus expert opinion. Regular ophthalmology screening of children with JIA is recommended because of the risk of uveitis and frequency of screening should be based on individual risk factors. Regular ophthalmology monitoring of children with uveitis is recommended and intervals should be based on ocular examination findings and treatment regimen. Ophthalmology monitoring recommendations were strong primarily because of concerns of vision-threatening complications of uveitis with infrequent monitoring. Topical glucocorticoids should be used as initial treatment to achieve control of inflammation. Methotrexate and the monoclonal antibody tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, adalimumab and infliximab, are recommended when systemic treatment is needed for the management of uveitis. Timely addition of non-biologic and biologic drugs is recommended to maintain uveitis control in children who are at continued risk of vision loss.

Conclusion:

This guideline provides direction for clinicians and patients/parents making decisions on the screening, monitoring, and management of children with JIA and uveitis using GRADE methodology and informed by a consensus process with input from rheumatology and ophthalmology experts, current literature, and patient/parent preferences and values.

Keywords: Juvenile idiopathic arthritis, uveitis, chronic anterior uveitis, acute anterior uveitis, cataract, glaucoma, elevated intraocular pressure, glucocorticoids, DMARDs, biologics, methotrexate, anti-tumor necrosis factor

INTRODUCTION

Uveitis is the most common extra-articular manifestation of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), and can be a chronic or acute disease. Chronic anterior uveitis (CAU) develops in 10–20% of children with JIA, is usually asymptomatic, and there is rarely external evidence of inflammation (1, 2). Acute anterior uveitis (AAU) is a distinctly different form of uveitis. It is typically associated with HLA-B27, and occurs in children with spondyloarthritis (i.e. those with enthesitis related or psoriatic arthritis). AAU differs from CAU in that AAU is episodic, unilateral, characterized by the sudden onset of erythema, pain, and photophobia, and generally does not require systemic treatment (3).

Uncontrolled CAU can lead to sight-threatening complications such as synechiae, cataracts, and glaucoma in 25–50% and vision loss in 10–20% of children with uveitis (2, 4–6). Early detection through regular ophthalmology screening with timely and appropriate treatment can improve visual outcomes and prevent complications (5, 7).

Because CAU is often asymptomatic until ocular complications arise, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published recommendations in 2006 for routine ophthalmology screening in children with arthritis (8). These recommendations were based upon an older arthritis nomenclature and did not include uveitis screening in all JIA categories such as psoriatic, enthesitis-related and undifferentiated arthritis. To fill this gap, in 2012, Heiligenhaus and colleagues from the German Uveitis in Childhood Study Group (“German Recommendations”) proposed ophthalmology screening schedules based on the International League Against Rheumatism (ILAR) JIA classification scheme (9). These two publications, however, did not address the monitoring of children with an established diagnosis of uveitis or the treatment of uveitis. Thus, recommendations for both monitoring and treatment of uveitis in children with JIA are needed.

Initial treatment of children with JIA-associated uveitis typically includes topical glucocorticoids. In those who are refractory to, or dependent on, topical glucocorticoids, there are no accepted North American guidelines for the use of systemic immunosuppressive therapy. Methotrexate is the usual first-line systemic immunosuppressive agent, followed by tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) biologics, particularly the monoclonal antibodies infliximab and adalimumab (10). Despite the frequency with which these drugs are used for uveitis, there is only one published large randomized controlled trial (RCT) studying children with JIA-associated uveitis (11). Guidance is needed for the acceptable duration and frequency of topical glucocorticoids prior to initiation of non-biological disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and biologic systemic therapy, and for the approach to initiation, escalation, and modification of systemic therapy. Optimization of treatment strategies is crucial to improve visual outcomes.

To address this need, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the Arthritis Foundation (AF) convened expert panels of pediatric rheumatologists and ophthalmologists to develop the first ACR/AF recommendations for the screening, monitoring, and treatment of JIA-associated CAU and AAU. Recognizing the importance of close collaboration and communication between pediatric rheumatologists and ophthalmologists, this guideline was developed in collaboration with experts from both specialties. In addition, clinicians, parents and patients should use a shared decision-making process that considers patients’ preferences and values. Recommendations for the treatment of children with JIA manifesting with non-systemic polyarthritis, sacroiliitis, and enthesitis were developed concomitantly and are presented separately (REF when available).

METHODS

Methodology Overview

This guideline followed the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guideline development process (http://www.rheumatology.org/Practice-Quality/Clinical-Support/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines). This process uses the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology (www.gradeworkinggroup.org) to rate the quality of the available evidence and to develop the recommendations (12–14). ACR policy guided disclosures and the management of potential conflicts of interest (insert link here to full participant disclosure list just before publication). Supplementary Appendix 1 presents the full methods in detail.

Guideline Development Teams

This work involved five groups: 1) a Core Leadership Team, consisting of 4 pediatric rheumatologists, supervised and coordinated the project and drafted the clinical questions and manuscript; 2) a Literature Review Team, led by an experienced literature review consultant, completed the literature search and data abstraction; 3) an Expert Panel, composed of 9 pediatric rheumatologists and one ophthalmologist with expertise in the management of uveitis in children, developed the clinical questions [population/intervention/comparator/outcomes] (PICO) questions and decided on the scope of the guideline project; 4) a Voting Panel, including 15 pediatric rheumatologists, 2 ophthalmologists, both of whom were uveitis specialists, and 2 adult patients with JIA, assisted with developing the scope of the project and refining PICO questions, reviewed the collated evidence and voted on the recommendations; and 5) a Parent and Patient Panel, consisting of 9 adult patients with JIA and 2 parents of children with JIA and uveitis, reviewed the collated evidence and provided input on their values and preferences, within the context of a separate voting meeting. Supplementary Appendix 2 presents rosters of the team and panel members. In accordance with ACR policy, the principal investigator and the leader of the literature review team were free of potential conflicts of interest, and all teams had >50% members free of potential conflicts of interest.

PICO Question Development and Importance of Outcomes

The Core Leadership Team drafted the initial project scope, key principles, and relevant clinical PICO questions. These were then presented to the guideline development groups for their review at a scoping face-to-face meeting where the project plan was defined. GRADE criteria provided the framework for judging the overall quality of evidence (12).

During the scoping meeting, the guideline scope, key terms and definitions were discussed and agreed upon (Table 1). The Expert Panel chose the following three areas of focus: 1) ophthalmology screening for uveitis in children with JIA; 2) ophthalmology monitoring of established uveitis in children with JIA; and 3) use of topical and systemic glucocorticoids and systemic immunosuppressant medications to treat uveitis. This guideline pertains to children with JIA and either CAU or AAU. The Expert Panel defined “controlled uveitis” as inactive OR Grade <1+ anterior chamber (AC) cells without new complications due to active inflammation per Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) criteria (15). “Loss of control” of uveitis was defined as an increase of AC cells to Grade 1+ or more or new signs of inflammation/complications of inflammation. A Grade of 1+ AC cells is 6–15 cells per field in a 1 mm by 1 mm slit beam, as seen through a biomicroscope. The term “new uveitis activity” included either new activity in patients with no history of prior uveitis, or recurrent activity in patients with loss of control of previously controlled uveitis. Complications due to active inflammation, additional signs of active inflammation, and complications representing cumulative damage were also defined (Table 1). Loss of control of uveitis, active uveitis, and complications can lead to partial or permanent vision loss.

Table 1.

Terms, Definitions and Medication Interventions

| Terms | Definition |

|---|---|

| Controlled uveitis | Inactive OR Grade <1+ anterior chamber (AC) cell without new complications due to active inflammation per Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) criteria* |

| Complications due to active inflammation† | New development of peripheral anterior synechiae, posterior synechiae, inflammatory membranes, or cystoid macular edema |

| Additional signs of active inflammation | Fresh keratic precipitates (KP), increased flare, and hypopyon |

| Complications representing cumulative damage | Cataract, glaucoma/elevated intraocular pressure, hypotony, sequelae of KP (hyalinized spots or ghost KP)‡ |

| Loss of control† | Increase of AC cells to Grade 1+ or more or new signs of inflammation/complications of inflammation* |

| New uveitis activity | No history of prior uveitis or loss of control of previously controlled uveitis |

| Systemic therapy | Non-biological disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and biologics |

| Medications Included in the Guideline | |

| Medications | Medication Names |

| Glucocorticoids | Topical eye drops Systemic (all oral) |

| Non-biological disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) | Methotrexate Leflunomide Mycophenolate Cyclosporine |

| Biologic DMARDs | Monoclonal TNFi: Adalimumab, Infliximab Etanercept Abatacept Tocilizumab |

Grade 1+ AC cell: 6–15 cells per field in a 1 mm by 1mm slit beam.

Loss of control of uveitis, active uveitis and complications can lead to partial or permanent vision loss.

These are not reversible changes and should not be indications to change treatment in the absence of active inflammation.

Critical and important outcomes varied based on the type of recommendation (Table 2). Critical outcomes related to screening included new diagnosis of uveitis and new diagnosis of uveitis with any ocular complications (Table 2). Critical outcomes related to monitoring included loss of control of uveitis and new complications due to inflammation. Critical outcomes related to medication use included loss of control of uveitis, incidence of loss of control of uveitis (rate or frequency of loss of control of uveitis, i.e. number of episodes over time), control of uveitis at 1 month and 3 months, new ocular glucocorticoid-related complications (cataracts, glaucoma/increased intraocular pressure [IOP], infection), new ocular complications due to inflammation, incident uveitis, and recurrence of uveitis. Other important outcomes for monitoring was severity and level of inflammation for monitoring, and for medication use were side effects of systemic therapy, time to control of uveitis, and time to loss of control of uveitis.

Table 2.

Critical and Important Outcomes*

| Screening |

Critical Outcomes:

|

| Monitoring |

Critical Outcomes:

Important Outcomes:

|

| Treatment |

Critical Outcomes:

Important Outcomes:

|

Vary depending on the recommendation.

Synthesis of the Literature and Grading of the Evidence

Systematic searches of the published English-language literature included OVID Medline, PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library (including Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Health Technology Assessments) from inception through June 12, 2017 (Supplementary Appendix 3); updated searches were conducted on October 13, 2017. DistillerSR software (https://distillercer.com/products/distillersr-systematic-reviewsoftware/) (Supplementary Appendix 4) facilitated duplicate screening of literature search results. Reviewers entered extracted data into RevMan software (http://tech.cochrane.org/revman) and evaluated the risk of bias of primary studies using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (http://handbook.cochrane.org/). RevMan files were exported into GRADEpro software to formulate a GRADE summary of findings table (Supplementary Appendix 5) for each PICO question (16).

When data were available, the evidence summaries included the benefits and harms for outcomes of interest across studies, the relative effect (with effect size and 95% CI), the number of participants, and the absolute effects. We rated the quality of evidence (also called certainty) for each critical and important outcome as high, moderate, low, or very low quality, taking into account, risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and other considerations as per the GRADE recommendations.

Moving from Evidence to Recommendations

GRADE methodology specifies that panels make recommendations based on the balance of benefits and harms, the quality of the evidence (i.e., confidence in effect estimates) and parents/patients’ values and preferences. Deciding on the balance between desirable and undesirable outcomes requires estimating the relative value patients place on those outcomes. When the literature did not provide clear evidence, recommendations were based on the values/preferences input from the members of the Parent and Patient Panel and on the experience of the Voting Panel members (including physicians and the two patients present).

Consensus Building

The Voting Panel voted on the direction and strength of the recommendation related to each PICO question. Recommendations required a 70% level of agreement, if 70% agreement was not achieved during an initial vote, Voting Panel members held additional discussions before re-voting, including rewording of recommendations if needed, until consensus was attained (17). For all conditional recommendations, a written explanation is provided, describing the reasons for this decision, and conditions under which the alternative may be preferable. A second round of voting occurred after the face-to face meeting for recommendations with additional questions. In some instances, the Voting Panel combined PICO questions into one recommendation for clarity. Some PICO questions were dropped during the consensus meeting due to insufficient evidence to make a formal recommendation (Supplementary Appendix 6).

Moving from Recommendations to Practice

These recommendations are designed to help health care providers work with parents/patients in selecting therapies. Health care providers and parents/patients must take into consideration all active disease domains, comorbidities, and the patient’s functional status in choosing the optimal therapy for an individual patient.

RESULTS/RECOMMENDATIONS

The literature searches retrieved 1,704 initial citations, 131 duplications were removed, and 1m537 uveitis unique citations identified. Full-length articles were abstracted and graded for evidence related to the 34 PICO questions. The available evidence was very low quality for all PICO questions, mainly for lack of evidence, and for indirectness of the evidence. Most articles were from observational studies which are considered low quality in the GRADE system.

How to Interpret the Recommendations

A strong recommendation means that the Voting Panel was confident that the desirable effects of following the recommendation outweigh the undesirable effects (or vice versa), so the course of action would apply to all or almost all patients, and only a small proportion would not want to follow the recommendation. Due to the risk of ocular complication with resultant vision loss with irregular or infrequent monitoring and because ophthalmology exams are low risk, all recommendations on ophthalmology monitoring exams of children with uveitis were strong despite very low quality of evidence. Patients were concerned about the consequences of infrequent monitoring and agreed there was little disadvantage to monitoring including potential cost and inconvenience of frequent visits.

A conditional recommendation means the Voting Panel believed that the desirable effects of following the recommendation probably outweigh the undesirable effects, so the course of action would apply to the majority of the patients, but some may not want to follow the recommendation. Because of patient preference and lack of strong evidence, conditional recommendations are preference-sensitive and always warrant a shared decision-making approach. All the treatment recommendations were conditional, except for one related to tapering topical glucocorticoids (Recommendation 18).

All the recommendations had very low quality of evidence, thus most of the recommendations are conditional.

All the recommendations are meant to apply to children with JIA at risk for and with associated uveitis, regardless of activity of arthritis and other manifestations of JIA.

When deciding on the frequency of ophthalmology monitoring and treatment decisions, close collaboration and communication between rheumatology and ophthalmology subspecialists is crucial. Points to consider include degree of ocular inflammation, presence of complications, use of topical glucocorticoids, and level of intraocular pressure.

Recommendations on topical glucocorticoids pertain to prednisolone acetate 1% or its equivalent dosing with other types of topical glucocorticoids.

Recommendations on systemic therapy pertain to non-biological DMARDs and biologics, and not systemic glucocorticoids.

Recommendations that consider TNFi biologics pertain to etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab only. Monoclonal antibody TNFi refers to adalimumab and infliximab due to lack of data and experience with other agents (golimumab, certolizumab, or biosimilars) for uveitis among pediatric patients. Only adalimumab, infliximab, etanercept, abatacept and tocilizumab were discussed, as data on the use of other biologics for treatment of uveitis are lacking.

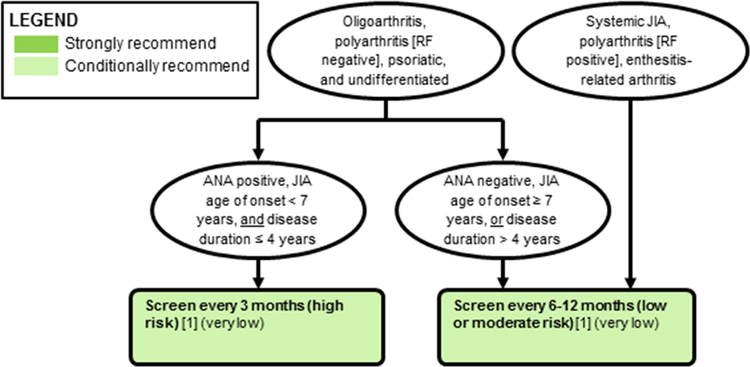

Recommendation for ophthalmology screening of children with JIA (Table 3, Figure 1a)

Table 3.

Recommendations for Ophthalmology Screening, Ophthalmology Monitoring and Treatment of Children with JIA-Associated Uveitis*

| Recommendations for ophthalmology screening |

In children and adolescents with JIA at high risk of developing uveitis:

|

| Recommendations for ophthalmology monitoring |

In children and adolescents with JIA and controlled uveitis who are:

|

| Recommendations for glucocorticoid use |

In children and adolescents with JIA and active CAU:

|

In children and adolescents with JIA and CAU still requiring 1–2 drops/day of prednisolone acetate 1% (or equivalent) for uveitis control:

|

In children and adolescents with JIA who develop new CAU activity‡

despite stable systemic therapy:

|

| Recommendations for DMARDs and biologics |

In children and adolescents with JIA and active CAU who are/have:

|

| Recommendations for education about and treatment of acute anterior uveitis |

In children and adolescents with spondyloarthritis:

|

| Recommendations for tapering therapy for uveitis |

In children and adolescents with JIA and CAU that is controlled on systemic therapy but remain on 1–2 drops/day of prednisolone acetate 1% (or equivalent):

|

In children and adolescents with JIA and uveitis that is well controlled on DMARD and biologic systemic therapy only:

|

Each recommendation had very low quality level of evidence.

High-risk children are those with oligoarthritis, polyarthritis (rheumatoid factor negative), psoriatic arthritis or undifferentiated arthritis who are also ANA positive, younger than 7 years of age at JIA onset and have JIA duration of 4 years or less.

Definition of new CAU activity: No prior uveitis or loss of control of previously controlled uveitis.

Figure 1a: Ophthalmologic screening examinations.

(see also Table 3). PICO questions in brackets, quality of evidence in parentheses. Strength of recommendation indicated by colors (see legend).

Recommendation 1.

In children and adolescents with JIA at high risk of developing uveitis, ophthalmology screening every 3 months is conditionally recommended over screening at a different frequency.

The Voting Panel agreed with combining the screening recommendations of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and American Academy of Ophthalmology, and the German Uveitis in Childhood Study Group (German recommendations) (8, 9). AAP recommendations are based on the older classification scheme “juvenile rheumatoid arthritis” or JRA, which does not include ILAR categories of psoriatic JIA, enthesitis related arthritis, and undifferentiated arthritis. The screening schedule suggested by the German recommendations incorporates these categories and recommends screening high-risk children every 3 months, similar to the AAP recommendations. Combining both AAP and German recommendations, high-risk children are those with oligoarthritis, polyarthritis [rheumatoid factor negative], psoriatic arthritis, or undifferentiated arthritis who are also antinuclear antibody (ANA) positive, younger than 7 years of age at JIA onset, and have JIA duration of 4 years or less. Low or moderate risk children are those with high risk JIA categories but who are ANA negative, 7 years or older at JIA onset, or have JIA duration of more than 4 years, and those with systemic JIA, polyarthritis [rheumatoid factor positive] and enthesitis-related arthritis. Low or moderate risk children should be screened every 6–12 months depending on their combination of risk factors. Since children with enthesitis related arthritis or carrying the HLA-B27 genotype are at risk for both AAU and CAU, they require screening as well. This recommendation was conditional, based on low quality of evidence, although several studies have described factors that increase the risk for developing uveitis (18–23). Some children have significant eye disease at time of screening under the current schedule, but there is lack of data showing that more frequent screening is beneficial. Patients and parents supported the recommended frequency of screening and expressed desire for frequent screening.

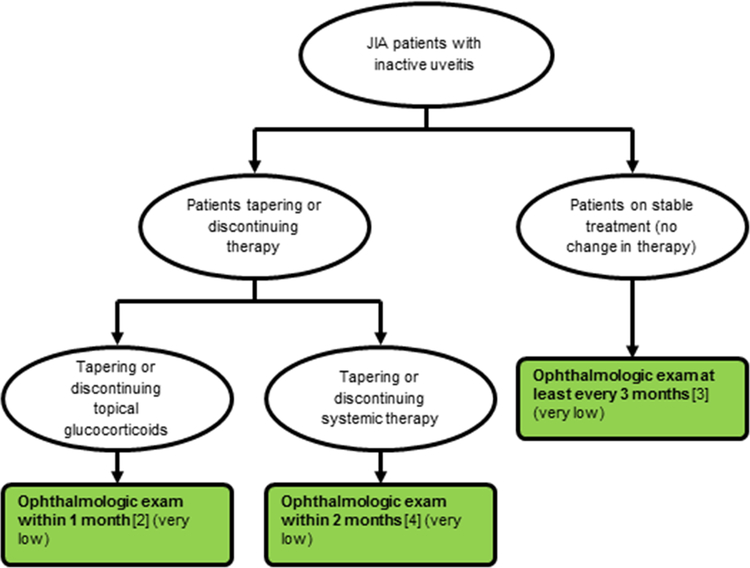

Recommendations for ophthalmology monitoring of children with JIA diagnosed with uveitis (Table 3, Figure 1b)

Figure 1b: Ophthalmologic monitoring examinations.

(see also Table 3). Recommendation number in brackets, quality of evidence in parentheses. Strength of recommendation indicated by colors (see legend). No recommendations made for patients with uncontrolled chronic anterior uveitis.

Recommendation 2.

In children and adolescents with JIA and controlled uveitis who are tapering or discontinuing topical glucocorticoids, ophthalmologic monitoring within one month after each change of topical glucocorticoids is strongly recommended over monitoring less frequently.

Recommendation 3.

In children and adolescents with JIA and controlled uveitis on stable therapy, ophthalmologic monitoring no less frequently than every 3 months is strongly recommended over monitoring less frequently.

Recommendation 4.

In children and adolescents with JIA and controlled uveitis who are tapering or discontinuing systemic therapy, ophthalmologic monitoring within two months of changing systemic therapy is strongly recommended over monitoring less frequently.

The need for regular monitoring of children with established uveitis was emphasized. The Voting Panel recommends that children with controlled CAU on stable medication should be monitored at 3-month intervals, and those tapering or discontinuing therapy should be monitored at intervals shorter than 3 months, either within one month after each change in topical glucocorticoids, and within 2 months of a change in systemic therapy (Figure 1b). Although the quality of evidence was very low, the recommendations for monitoring were strong due to the potential for harmful consequences of irregular or infrequent monitoring of children with CAU, which could lead to substantial loss of vision and ocular complications from undetected exacerbation of inflammation (19, 24). Patients were generally concerned about consequences of infrequent monitoring, and agreed there was little disadvantage to having frequent ophthalmology exams. The Voting Panel agreed that the frequency of monitoring may be influenced by the half-life of the systemic therapy and by the expected time of efficacy of systemic therapy.

The Voting Panel was not able to reach consensus on a standard schedule of ophthalmologic monitoring in children and adolescents with uncontrolled CAU, thus no formal recommendation was made. The Voting Panel agreed, however, that regular monitoring is needed for uncontrolled uveitis, and that in most cases, examinations could occur at 2–6-week intervals tailored to the frequency of topical glucocorticoid administration, intraocular pressure, degree of inflammation, and presence of complications, as agreed upon by the treatment team.

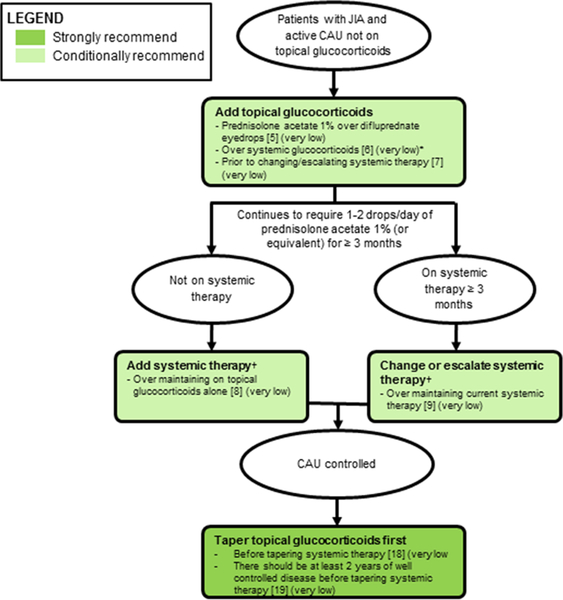

Recommendations for glucocorticoid use (Table 3, Figure 2)

Figure 2: Recommendations for topical glucocorticoids in patients with JIA and chronic anterior uveitis (CAU).

(see also Table 3). Recommendation number in brackets, quality of evidence in parentheses. Strength of recommendation indicated by colors (see legend). systemic therapy defined as D-MARDs and biologies. Topical glucocorticoids refer to prednisolone acetate 1% (or equivalent). Doses of prednisolone acetate 1% greater than 1–2 drops/eye/day may be needed initially, but increase risk for ocular complications. Topical glucocorticoids should be used as short-term therapy ≤3 months. Goal is to discontinue topical glucocorticoids due to risk of glaucoma and cataracts. Periocular and itraocular injection is at the discretion of the treating ophthalmologist.

*In selected complicated patients, systemic glucocorticoids can be used as short-term bridging therapy.

†Can escalate dose or frequency of current therapy; 3 months is the threshold for adding or changing systemic therapy in children who require topical glucocorticoids to maintain uveitis control. Changes in systemic therapy may be warranted earlier, depending upon findings on the ocular examination, the duration of topical and systemic therapy, and presence of existing complications.

JIA = juvenile id idiopathic arthritis; CAU = chronic anterior uveitis.

Recommendation 5.

In children and adolescents with JIA and active CAU, using prednisolone acetate 1% topical drops is conditionally recommended over difluprednate topical drops.

Recommendation 6.

In children and adolescents with JIA and active CAU, adding or increasing topical glucocorticoids for short-term control is conditionally recommended over adding systemic glucocorticoids.

Frequent topical glucocorticoids should be used as initial therapy to control inflammation followed by tapering as soon as the anterior chamber cellular reaction comes under control. The recommendation was conditional based on the very low quality of evidence (25). Prednisolone acetate 1% topical drops are the preferred topical glucocorticoid based on better corneal penetration over other eye drops, and the fact that there is less experience with difluprednate, which has increased risk of corticosteroid-induced intraocular pressure and cataract formation (26, 27). However, because long-term comparison data between both formulations are lacking, this recommendation was conditional. Patient compliance should be taken into consideration as prednisolone acetate 1% requires more frequent administration due to its lower potency than difluprednate. The Voting Panel recognized that in selected complicated patients, systemic glucocorticoids can be used as short-term bridging therapy. The Voting Panel did not seek consensus to make a recommendation on the use of periocular or intraocular glucocorticoids.

Recommendation 7.

In children and adolescents with JIA who develop new CAU activity despite stable systemic therapy, topical glucocorticoids prior to changing/escalating systemic therapy is conditionally recommended over changing/escalating systemic therapy immediately.

Initially, topical glucocorticoids should be given in children with uncontrolled uveitis, whether a new diagnosis or exacerbation of previously controlled uveitis, unless there is a contraindication. Adding, changing, or escalating (increasing the dose or frequency) systemic therapy should be considered in those who continue to require prednisolone acetate 1% 1–2 drops/day (or equivalent) (Recommendations 8 and 9). This recommendation was conditional based on very low quality of data.

Recommendation 8.

In children and adolescents with JIA and CAU still requiring 1–2 drops/day of prednisolone acetate 1% (or equivalent) for uveitis control, and not on systemic therapy, adding systemic therapy in order to taper topical glucocorticoids is conditionally recommended over not adding systemic therapy and maintaining on topical glucocorticoids only.

The risk for elevated IOP and cataracts increases with greater frequency of topical glucocorticoid drops/day and longer duration of therapy. Kothari et al. found that topical glucocorticoid use at ≥2 drops/day was a strong risk factor for IOP elevation, which increased with greater number of drops/day (28). Another retrospective cohort study found that ≤3 drops daily of prednisolone is preferred to ≥4 drops daily to decrease the risk of developing cataracts (29). The Voting Panel recommends adding systemic DMARD therapy in children needing ongoing topical glucocorticoids to control uveitis, with the ultimate goal of discontinuation of topical glucocorticoids. These recommendations were conditional due to very low quality of data and because there may be reasons that a dose of 1–2 drops per day of topical prednisolone is unacceptable, such as presence of complications from use of topical glucocorticoids, contraindications to topical glucocorticoids, and difficulty in compliance with multiple drops per day. Nevertheless, prednisolone 1–2 drops a day may be appropriate as monotherapy if there are no issues with ocular complications such as elevated IOP and cataract, no difficulties with the use of topical glucocorticoids, and there is regular close follow-up with an ophthalmologist.

Recommendation 9.

In children and adolescents with JIA and CAU still requiring 1–2 drops/day of prednisolone acetate 1% (or equivalent) for at least 3 months and on systemic therapy for uveitis control, changing or escalating systemic therapy is conditionally recommended over maintaining current systemic therapy.

The Voting Panel agreed on 3 months as the threshold for adding or changing systemic therapy in children who require topical glucocorticoids to maintain uveitis control. Nevertheless, changes in systemic therapy may be warranted earlier, depending upon findings on the ocular examination, the duration of topical and systemic therapy, and presence of existing complications. The recommendation was conditional because of the very low quality of the evidence, the variation in the severity of a child’s disease presentation, child and family preference for topical medication over systemic therapy, and the specific systemic therapy being considered.

Recommendations for DMARDS and biologics (Table 3)

Recommendation 10.

In children and adolescents with JIA and CAU who are starting systemic treatment for uveitis, using subcutaneous methotrexate is conditionally recommended over oral methotrexate.

Recommendation 11.

In children and adolescents with JIA with severe active CAU and sight threating complications, starting methotrexate and a monoclonal antibody TNFi immediately is conditionally recommended over methotrexate as monotherapy.

Methotrexate and monoclonal antibody TNFi are the mainstays of systemic treatment of uveitis. Subcutaneous methotrexate was considered preferable to oral administration for uveitis, but this recommendation was conditional given the lack of strong data on differential efficacy, and that family preferences as to route of administration may differ. In children with severe active uveitis and sight-threatening complications, combining methotrexate with a monoclonal antibody TNFi at the time of initiation of systemic immunosuppressive treatment was recommended over methotrexate as monotherapy. Severe uveitis could be considered the presence of ocular structural complications due to uveitis, or complications of topical steroid therapy (30). This recommendation was conditional, based upon the lack of direct evidence from studies, risk of permanent vision loss, and anticipated differences in patient values and preferences.

Recommendation 12.

In children and adolescents with JIA and active CAU starting a TNFi, starting a monoclonal antibody TNFi is conditionally recommended over etanercept.

Monoclonal antibody TNFi, specifically adalimumab and infliximab, were conditionally recommended over etanercept for active CAU. Although there is a paucity of direct comparisons, benefit has been shown to using monoclonal antibody TNFi. The Voting Panel was not able to make recommendations on preferred TNFi for children with active JIA to prevent uveitis onset, or for children with known CAU to prevent uveitis flares due to lack of evidence (31–35). The Voting Panel also did not make a recommendation on preference between adalimumab and infliximab for use as initial TNFi.

Recommendation 13.

In children and adolescents with JIA and active CAU who have an inadequate response to one monoclonal antibody TNFi at standard JIA dose, escalating the dose and/or frequency to above-standard is conditionally recommended over switching to another monoclonal antibody TNFi.

Recommendation 14.

In children and adolescents with JIA and active CAU who have failed a first monoclonal antibody TNFi at above-standard dose and/or frequency, changing to another monoclonal antibody TNFi is conditionally recommended over a biologic in another category.

These two recommendations assume that uveitis activity or severity guides therapy in the patient, irrespective of joint disease activity. The Voting Panel did not make a recommendation on preference between adalimumab and infliximab as first-line TNFi, or use of above-standard TNFi dosing at treatment initiation.

For children treated with a monoclonal antibody TNFi at standard JIA dosing who have an inadequate response to therapy, the Voting Panel conditionally recommended escalating the dose and/or frequency to above-standard dosing used for arthritis prior to switching to another monoclonal antibody TNFi. Although consensus was not reached regarding a specific dose or frequency, doses as high as infliximab 20 mg / kg every 2 weeks and adalimumab weekly have been reported in observational studies in children with JIA and uveitis (36–38). If the initial monoclonal antibody TNFi fails at an increased dose/frequency, the recommendation was to change to another monoclonal antibody TNFi prior to changing to a biologic agent in another category. These recommendations were conditional due to very low quality evidence.

Recommendation 15.

In children and adolescents with JIA and active CAU who have failed methotrexate and 2 monoclonal antibody TNFi at above-standard dose and/or frequency, conditionally recommend abatacept or tocilizumab as biologic DMARD options, and mycophenolate, leflunomide, or cyclosporine as alternative non-biologic DMARD options.

The quality of evidence for subsequent treatment in children who have failed methotrexate in combination with monoclonal antibody TNFi treatment is very low. Based on current literature, recommended alternative non-biologic options are mycophenolate mofetil (39), leflunomide (40) or cyclosporine (41), and recommended alternative biologic options are abatacept (42–44) or tocilizumab (45, 46); however, evidence supporting preference for a specific non-biologic or biologic DMARD, combination therapies, and timing of initiation beyond methotrexate, adalimumab, and infliximab is currently lacking. Several PICO questions were combined in this recommendation for clarity.

Recommendations for education about and treatment of acute anterior uveitis (Table 3)

Recommendation 16.

In children and adolescents with spondyloarthritis, strongly recommend education regarding the warning signs of AAU for the purpose of decreasing delay in treatment, duration of symptoms, or complications of iritis.

AAU is generally a manifestation of a subset of children who are HLA-B27 positive with enthesitis related arthritis and in some cases of psoriatic arthritis. Although the quality of evidence was very low (there were no studies identified that addressed these topics), the Voting Panel strongly agreed, based on experience, that HLA-B27 positive patients with enthesitis-related arthritis or psoriatic arthritis, and their families should be educated regarding warning signs of AAU for the purpose of decreasing delay in treatment, duration of symptoms, or ocular complications. Signs include eye pain, redness, and photophobia. This recommendation was strong because education about a disease and warning signs is standard of care.

Recommendation 17.

In children and adolescents with spondyloarthritis otherwise well controlled with systemic immunosuppressive therapy (DMARDs, biologics) who develop AAU, conditionally recommend against switching systemic immunosuppressive therapy immediately in favor of treating with topical glucocorticoids first.

Because AAU episodes are typically of short duration and may be easily controlled with topical glucocorticoids, the Voting Panel conditionally recommended continuing the same systemic immunosuppressive therapy, and treating with topical glucocorticoids at initial development of AAU (47). During an isolated short-lived episode of AAU, an immediate escalation or change of underlying systemic therapy may not be necessary without trying a course of topical glucocorticoids first. This recommendation was conditional as there is lack of supporting data. Furthermore, frequent recurrent episodes of AAU may prompt a change from a non-monoclonal antibody TNFi to a monoclonal antibody TNFi, or there may be ocular complications from use of topical glucocorticoids that require prompt adjustment of systemic treatment, to decrease exposure to glucocorticoid therapy.

Recommendations for tapering therapy for uveitis (Table 3)

Recommendation 18.

In children and adolescents with JIA and CAU that is controlled on systemic therapy but remain on 1–2 drops/day of prednisolone acetate 1% (or equivalent), tapering topical glucocorticoids first is strongly recommended over systemic therapy.

There is very low quality of evidence for timing of tapering of topical glucocorticoids and systemic therapy (24, 48, 49). Some ophthalmologists feel that in selected cases, it is not possible to discontinue topical glucocorticoids altogether, despite attempts to do so, and the patients may be continued on 1–2 drops daily for extended periods. Despite the very low quality of evidence, the Voting Panel strongly recommended attempting to taper topical glucocorticoids prior to tapering systemic therapy because of the secondary complications that can occur with prolonged and frequent use of glucocorticoids (28, 29). Tapering of systemic therapy first may lead to the need for increased frequency of topical glucocorticoids for uveitis flares.

Recommendation 19.

In children and adolescents with uveitis that is well controlled on DMARD and biologic systemic therapy only, conditionally recommend that there be at least 2 years of well-controlled disease before tapering therapy.

The Voting Panel conditionally recommends attempted tapering of DMARD and biologic systemic therapy (DMARDs and biologics) only after uveitis has been well controlled for at least 2 years. Relapse-free survival after withdrawal of methotrexate was significantly longer in patients treated with methotrexate for more than 3 years, and who had controlled uveitis greater than 2 years before the withdrawal (49). Duration of systemic therapy may be greater than 2 years since tapering should not begin until at least 2 years of uveitis control. Decisions to taper systemic therapy should also take into consideration other JIA manifestations including arthritis activity.

DISCUSSION

This 2018 ACR guideline provides direction on the screening of children with JIA at risk for CAU, monitoring of children diagnosed with CAU, treatment with glucocorticoids, non-biologic DMARDs, and biologic DMARDs for CAU, and education and treatment of children with or at risk for AAU. Few uveitis practice guidelines have this broad scope (50–53). Although the quality of evidence was very low and most recommendations were therefore conditional, this guideline fills an important clinical gap in the care of children with JIA associated uveitis, and may be updated as better evidence becomes available.

Optimal care of children with uveitis requires careful and close collaboration among subspecialists as, in most cases, ophthalmologists assess uveitis activity and ocular complications and provide topical therapy, and rheumatologists manage systemic treatment. Thus, the Voting Panel consisted of both pediatric rheumatologists and ophthalmologists with expertise in uveitis evaluation and management. We acknowledge that there were more pediatric rheumatologists than ophthalmologists on the Voting Panel. However, both ophthalmologists were active in the voting process and in all discussions that led to the final recommendations.

A major limitation is the lack of good quality of evidence in children with JIA and uveitis. Only one well-conducted RCT on the use of adalimumab and methotrexate in children with JIA-associated uveitis was identified (11). This highlights the necessity of further studies in this population. We limited our recommendations to biologic DMARDs for which there was sufficient observational data and experience. Thus, biologics such as rituximab, golimumab, certolizumab, TNF-inhibitor biosimilars, and non-biologic drug tofacitinib were not considered. These agents may be included in future guidelines. Although we based our recommendations on studies that focused on treatment of uveitis specifically, there is difficulty in separating treatment of arthritis and CAU in studies. Also, cost was not formally taken into consideration in these guidelines. There was heavy reliance on one high quality RCT for these guidelines, and due to the lack of controlled trial data, most recommendations relied on expert opinion (11). There is an urgent need for RCTs in children with JIA-associated uveitis which will better inform treatment decisions in this population. In addition, further investigations are needed on the role of drug antibodies, long-term ophthalmic screening of children with JIA, and drug tapering in children with refractory uveitis. As more evidence becomes available, these can inform future guidelines. In summary, these recommendations provide guidance on the evaluation and management of children at risk for and with JIA-associated uveitis by rheumatology and ophthalmology experts, current literature, and patient and parent preferences and values using state of the art GRADE methodology. Persistent uncontrolled uveitis leads to sight-threatening ocular complications and permanent vision loss. The ultimate goal is to maintain optimal vision and ocular health in children with uveitis by limiting the duration of ocular inflammation, minimizing exposure to long term topical glucocorticoids through the expedited use of systemic medications, and preventing secondary ocular sequelae.

Supplementary Material

SIGNIFICANCE & INNOVATION.

Children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) are at increased risk for developing uveitis and sight-threatening complications.

Regular ophthalmology screening in children with JIA is important for early uveitis detection, and timely and appropriate treatment.

Regular ophthalmology monitoring of children with an established diagnosis of uveitis is needed.

Appropriate use of topical glucocorticoids, non-biological disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, and biologic systemic therapy can improve vision outcomes.

Guidelines and recommendations developed and/or endorsed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) are intended to provide guidance for particular patterns of practice and not to dictate the care of a particular patient. The ACR considers adherence to the recommendations within this guideline to be voluntary, with the ultimate determination regarding their application to be made by the physician in light of each patient’s individual circumstances. Guidelines and recommendations are intended to promote beneficial or desirable outcomes but cannot guarantee any specific outcome. Guidelines and recommendations developed and endorsed by the ACR are subject to periodic revision as warranted by the evolution of medical knowledge, technology, and practice. ACR recommendations are not intended to dictate payment or insurance decisions. These recommendations cannot adequately convey all uncertainties and nuances of patient care.

The American College of Rheumatology is an independent, professional, medical and scientific society that does not guarantee, warrant, or endorse any commercial product or service.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Alexei Grom, MD, Ron Laxer, MD, FRCP, Mindy Lo, MD, PhD, Sampath Prahalad, MD, MSc, Meredith Riebschleger, MD, Angela Byun Robinson, MD, Grant Schulert, MD, PhD, Heather Tory, MD, and Richard Vehe, MD, for serving on the Expert Panel. We thank Ms. Suzanne Schrandt with the AF for her involvement throughout the guideline development process. We thank our patient representative for adding valuable perspectives. We thank Dr. Liana Frankel for leading the Patient Panel meeting, as well the patients and parents who participated in this guideline project – Linda Aguiar, Jake Anderson, Samantha Bell, Julianne Capron, Stephanie Dodunski, Holly Dwyer, Stephanie Kweicein, Carolina Mejia Pena, and Nikki Reitz, LCSW. We thank the ACR staff, including Ms. Regina Parker for assistance in organizing the face-to-face meeting and coordinating the administrative aspects of the project, and Ms. Robin Lane for assistance in manuscript preparation. We thank Ms. Janet Waters for help in developing the literature search strategy and performing the literature search and updates, and Ms. Janet Joyce for peer-reviewing the literature search strategy.

Grant support: This material is the result of a project supported by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the Arthritis Foundation (AF). Dr. Angeles-Han was supported by Award Number K23EY021760 from the National Eye Institute, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, and the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center Research Innovation and Pilot fund. Drs. Colbert (AR041184) and Ombrello (AR041198) were supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Nigrovic was supported by the Fundación Bechara. Dr. Sen’s was supported by the Intramural Research Program of National Eye Institute (EY000356–16).

Footnotes

Financial Conflict: Forms submitted as required.

IRB approval: This study did not involve human subjects and, therefore, approval from Human Studies Committees was not required.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ravelli A, Martini A. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet. 2007;369(9563):767–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holland GN, Denove CS, Yu F. Chronic anterior uveitis in children: clinical characteristics and complications. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147(4):667–78 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tay-Kearney ML, Schwam BL, Lowder C, Dunn JP, Meisler DM, Vitale S, et al. Clinical features and associated systemic diseases of HLA-B27 uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121(1):47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenberg KD, Feuer WJ, Davis JL. Ocular complications of pediatric uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(12):2299–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thorne JE, Woreta F, Kedhar SR, Dunn JP, Jabs DA. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis: incidence of ocular complications and visual acuity loss. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(5):840–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith JA, Mackensen F, Sen HN, Leigh JF, Watkins AS, Pyatetsky D, et al. Epidemiology and course of disease in childhood uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(8):1544–51, 51 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregory AC 2nd, Kempen JH, Daniel E, Kacmaz RO, Foster CS, Jabs DA, et al. Risk factors for loss of visual acuity among patients with uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: the Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapy for Eye Diseases Study. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(1):186–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cassidy J, Kivlin J, Lindsley C, Nocton J, Section on R, Section on O. Ophthalmologic examinations in children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):1843–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heiligenhaus A, Niewerth M, Ganser G, Heinz C, Minden K, German Uveitis in Childhood Study G. Prevalence and complications of uveitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a population-based nation-wide study in Germany: suggested modification of the current screening guidelines. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46(6):1015–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henderson LA, Zurakowski D, Angeles-Han ST, Lasky A, Rabinovich CE, Lo MS, et al. Medication use in juvenile uveitis patients enrolled in the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance Registry. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2016;14(1):9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramanan AV, Dick AD, Jones AP, McKay A, Williamson PR, Compeyrot-Lacassagne S, et al. Adalimumab plus Methotrexate for Uveitis in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(17):1637–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrews J, Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Alderson P, Dahm P, Falck-Ytter Y, et al. GRADE guidelines: 14. Going from evidence to recommendations: the significance and presentation of recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(7):719–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrews JC, Schunemann HJ, Oxman AD, Pottie K, Meerpohl JJ, Coello PA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 15. Going from evidence to recommendation-determinants of a recommendation’s direction and strength. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(7):726–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT, Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature Working G. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(3):509–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Atkins D, Brozek J, Vist G, et al. GRADE guidelines: 2. Framing the question and deciding on important outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH, Dellinger P, Schunemann H, Levy MM, Kunz R, et al. Use of GRADE grid to reach decisions on clinical practice guidelines when consensus is elusive. BMJ. 2008;337:a744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kodsi SR, Rubin SE, Milojevic D, Ilowite N, Gottlieb B. Time of onset of uveitis in children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J AAPOS. 2002;6(6):373–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grassi A, Corona F, Casellato A, Carnelli V, Bardare M. Prevalence and outcome of juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis and relation to articular disease. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(5):1139–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reininga JK, Los LI, Wulffraat NM, Armbrust W. The evaluation of uveitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) patients: are current ophthalmologic screening guidelines adequate? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26(2):367–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zannin ME, Buscain I, Vittadello F, Martini G, Alessio M, Orsoni JG, et al. Timing of uveitis onset in oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the main predictor of severe course uveitis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90(1):91–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papadopoulou M, Zetterberg M, Oskarsdottir S, Andersson Gronlund M. Assessment of the outcome of ophthalmological screening for uveitis in a cohort of Swedish children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chia A, Lee V, Graham EM, Edelsten C. Factors related to severe uveitis at diagnosis in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a screening program. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135(6):757–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lerman MA, Lewen MD, Kempen JH, Mills MD. Uveitis Reactivation in Children Treated With Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha Inhibitors. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160(1):193–200 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolf MD, Lichter PR, Ragsdale CG. Prognostic factors in the uveitis of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Ophthalmology. 1987;94(10):1242–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Musson DG, Bidgood AM, Olejnik O. An in vitro comparison of the permeability of prednisolone, prednisolone sodium phosphate, and prednisolone acetate across the NZW rabbit cornea. J Ocul Pharmacol. 1992;8(2):139–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slabaugh MA, Herlihy E, Ongchin S, van Gelder RN. Efficacy and potential complications of difluprednate use for pediatric uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153(5):932–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kothari S, Foster CS, Pistilli M, Liesegang TL, Daniel E, Sen HN, et al. The Risk of Intraocular Pressure Elevation in Pediatric Noninfectious Uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(10):1987–2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thorne JE, Woreta FA, Dunn JP, Jabs DA. Risk of cataract development among children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis-related uveitis treated with topical corticosteroids. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(7):1436–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Angeles-Han ST, Lo MS, Henderson LA, Lerman MA, Abramson L, Cooper AM, et al. Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance consensus treatment plans for juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated and idiopathic chronic anterior uveitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tynjala P, Lindahl P, Honkanen V, Lahdenne P, Kotaniemi K. Infliximab and etanercept in the treatment of chronic uveitis associated with refractory juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(4):548–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foeldvari I, Becker I, Horneff G. Uveitis Events During Adalimumab, Etanercept, and Methotrexate Therapy in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: Data From the Biologics in Pediatric Rheumatology Registry. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015;67(11):1529–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saurenmann RK, Levin AV, Feldman BM, Laxer RM, Schneider R, Silverman ED. Risk of new-onset uveitis in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis treated with anti-TNFalpha agents. J Pediatr. 2006;149(6):833–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tappeiner C, Schenck S, Niewerth M, Heiligenhaus A, Minden K, Klotsche J. Impact of Antiinflammatory Treatment on the Onset of Uveitis in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: Longitudinal Analysis From a Nationwide Pediatric Rheumatology Database. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(1):46–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klotsche J, Niewerth M, Haas JP, Huppertz HI, Zink A, Horneff G, et al. Long-term safety of etanercept and adalimumab compared to methotrexate in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(5):855–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kahn P, Weiss M, Imundo LF, Levy DM. Favorable response to high-dose infliximab for refractory childhood uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(5):860–4 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tambralli A, Beukelman T, Weiser P, Atkinson TP, Cron RQ, Stoll ML. High doses of infliximab in the management of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2013;40(10):1749–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Correll CK, Bullock DR, Cafferty RM, Vehe RK. Safety of weekly adalimumab in the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis and pediatric chronic uveitis. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37(2):549–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sobrin L, Christen W, Foster CS. Mycophenolate mofetil after methotrexate failure or intolerance in the treatment of scleritis and uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(8):1416–21, 21 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bichler J, Benseler SM, Krumrey-Langkammerer M, Haas JP, Hugle B. Leflunomide is associated with a higher flare rate compared to methotrexate in the treatment of chronic uveitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2015;44(4):280–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kolomeyer AM, Tu Y, Miserocchi E, Ranjan M, Davidow A, Chu DS. Chronic Non-infectious Uveitis in Patients with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2016;24(4):377–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tappeiner C, Miserocchi E, Bodaghi B, Kotaniemi K, Mackensen F, Gerloni V, et al. Abatacept in the treatment of severe, longstanding, and refractory uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(4):706–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Birolo C, Zannin ME, Arsenyeva S, Cimaz R, Miserocchi E, Dubko M, et al. Comparable Efficacy of Abatacept Used as First-line or Second-line Biological Agent for Severe Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis-related Uveitis. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(11):2068–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zulian F, Balzarin M, Falcini F, Martini G, Alessio M, Cimaz R, et al. Abatacept for severe anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha refractory juvenile idiopathic arthritis-related uveitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62(6):821–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Calvo-Rio V, Santos-Gomez M, Calvo I, Gonzalez-Fernandez MI, Lopez-Montesinos B, Mesquida M, et al. Anti-Interleukin-6 Receptor Tocilizumab for Severe Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis-Associated Uveitis Refractory to Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Therapy: A Multicenter Study of Twenty-Five Patients. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(3):668–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tappeiner C, Mesquida M, Adan A, Anton J, Ramanan AV, Carreno E, et al. Evidence for Tocilizumab as a Treatment Option in Refractory Uveitis Associated with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(12):2183–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chang JH, McCluskey PJ, Wakefield D. Acute anterior uveitis and HLA-B27. Surv Ophthalmol. 2005;50(4):364–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Breitbach M, Tappeiner C, Bohm MR, Zurek-Imhoff B, Heinz C, Thanos S, et al. Discontinuation of long-term adalimumab treatment in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2017;255(1):171–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kalinina Ayuso V, van de Winkel EL, Rothova A, de Boer JH. Relapse rate of uveitis post-methotrexate treatment in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151(2):217–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bou R, Adan A, Borras F, Bravo B, Calvo I, De Inocencio J, et al. Clinical management algorithm of uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: interdisciplinary panel consensus. Rheumatology international. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levy-Clarke G, Jabs DA, Read RW, Rosenbaum JT, Vitale A, Van Gelder RN. Expert panel recommendations for the use of anti-tumor necrosis factor biologic agents in patients with ocular inflammatory disorders. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(3):785–96 e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heiligenhaus A, Michels H, Schumacher C, Kopp I, Neudorf U, Niehues T, et al. Evidence-based, interdisciplinary guidelines for anti-inflammatory treatment of uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32(5):1121–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Constantin T, Foeldvari I, Anton J, de Boer J, Czitrom-Guillaume S, Edelsten C, et al. Consensus-based recommendations for the management of uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: the SHARE initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(8):1107–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.