Abstract

Mutations in α1A, the pore-forming subunit of P/Q-type calcium channels, are linked to several human diseases, including familial hemiplegic migraine (FHM). We introduced the four missense mutations linked to FHM into human α1A-2subunits and investigated their functional consequences after expression in human embryonic kidney 293 cells. By combining single-channel and whole-cell patch-clamp recordings, we show that all four mutations affect both the biophysical properties and the density of functional channels. Mutation R192Q in the S4 segment of domain I increased the density of functional P/Q-type channels and their open probability. Mutation T666M in the pore loop of domain II decreased both the density of functional channels and their unitary conductance (from 20 to 11 pS). Mutations V714A and I1815L in the S6 segments of domains II and IV shifted the voltage range of activation toward more negative voltages, increased both the open probability and the rate of recovery from inactivation, and decreased the density of functional channels. Mutation V714A decreased the single-channel conductance to 16 pS. Strikingly, the reduction in single-channel conductance induced by mutations T666M and V714A was not observed in some patches or periods of activity, suggesting that the abnormal channel may switch on and off, perhaps depending on some unknown factor. Our data show that the FHM mutations can lead to both gain- and loss-of-function of human P/Q-type calcium channels.

Keywords: calcium channel, familial hemiplegic migraine, cerebellar ataxia, α1A subunit, mutation, channelopathy

Voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels control important neuronal functions including neurotransmitter release, neuronal excitability, activity-dependent gene expression, as well as neuronal survival, differentiation, and plasticity. Recently, mutations in the human gene CACNA1A encoding α1A, the pore-forming subunit of a neuronal voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel (Diriong et al., 1995), have been linked to three autosomal dominant human neurological disorders, including familial hemiplegic migraine (FHM), episodic ataxia type-2 (EA-2), and spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 (SCA6) (Ophoff et al., 1996; Zhuchenko et al., 1997). FHM is a rare subtype of migraine with aura also associated with ictal hemiparesis and, in some families, with progressive cerebellar atrophy and ataxia (Terwindt et al., 1998). Four different missense mutations in conserved functional domains of the α1A subunit have been identified in five unrelated FHM families (Ophoff et al., 1996). Some evidence suggests that the CACNA1A gene is also involved in more common forms of migraine (May et al., 1995; Terwindt et al., 1998). Mutations in α1A have been also identified in the tottering (tg) and leaner (tgla) mice, two strains of epileptic mice with seizures remarkably similar to human absence epilepsy (Fletcher et al., 1996; Doyle et al., 1997).

A common phenotype that appears in FHM, EA-2, SCA6, and in the epileptic mice is progressive cerebellar degeneration and ataxia. In both humans and rats, the expression of α1A subunits is particularly high in the cerebellum (Mori et al., 1991; Starr et al., 1991; Volsen et al., 1995; Westenbroek et al., 1995). Most of the Ca2+ current of Purkinje cells and a large fraction of the Ca2+ current of cerebellar granule cells is inhibited by ω-AgaIVA, the spider toxin that specifically inhibits the so-called P/Q-type Ca2+ channels, a heterogeneous class of Ca2+ channels, with differing functional and pharmacological properties (Mintz et al., 1992; Usowicz et al., 1992; Randall and Tsien, 1995; Dupere et al., 1996; Tottene et al., 1996). Recent evidence indicates that α1A is the pore-forming subunit of P/Q-type calcium channels (Gillard et al., 1997; Lorenzon et al., 1998; Piedras-Renteria and Tsien, 1998; Pinto et al., 1998). These channels play a prominent role in controlling neurotransmitter release in many synapses throughout the brain (Dunlap et al., 1995).

The discovery that the gene encoding α1A subunits is linked to several human diseases raises the question of how these mutations affect the biophysical properties of human P/Q-type calcium channels. Kraus et al. (1998) introduced the four FHM mutations in rabbit α1A subunits and expressed the mutant subunits inXenopus oocytes. Their results show that three of the four mutations alter the inactivation properties of rabbit recombinant α1A channels.

Here, we have introduced the four missense mutations linked to FHM in human α1A-2 subunits and investigated the effect of each mutation on the single-channel conductance and gating properties of human recombinant α1A channels after expression in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells. We show that all four mutations affect both the biophysical properties and the density of functional channels. They can lead to both loss- and gain-of-function of human P/Q-type calcium channels. A surprising finding suggests that the effect of the mutations on single-channel conductance may switch on and off and/or may depend on additional factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Molecular biology, cell culture, transient transfections. Because of deletions and insertions in the α1A cDNAs used in this study relative to those published by Ophoff et al. (1996), the I1811L mutation described by that group is referred to here as I1815L. Human α1A-2 mutants V714A, T666M, and I1815L were generated by the overlap extension method of the PCR (Ho et al., 1989). For T666M (TM), anEcoRI–SacI [nucleotides (nt) 1568–2168] fragment containing the C→T mutation at nucleotide 1997 was ligated into the correspondingEcoRI–SacI sites of pcDNA1α1A-2. For V716A (VA), an EcoRI–ApaLI (nt 1568–2809) fragment containing the T→C mutation at nucleotide 2141 was ligated into the corresponding EcoRI–ApaLI sites of pcDNA1α1A-2. For I1815L (IL), aHindIII–SphI (nt 5283–5556) fragment containing the A→C mutation at nucleotide 5443 was ligated into the corresponding HindIII–SphI sites of pcDNA1α1A-2. To generate the R192Q (RQ) mutation, an antisense oligonucleotide spanning the NotI site (nt 602) and containing a G→A mutation at nucleotide 575 was used to amplify a product containing the desired mutation. A BamHI (polylinker)–NotI fragment of the PCR product was ligated into the corresponding BamHI–NotI sites of pcDNA1α1A-2.

Recombinant channel expression was performed in HEK293 cells (CRL-1533; American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD). Cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 6% defined/supplemented bovine calf serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, and 100 U/ml of penicillin. HEK293 cells were cotransfected with pcDNA1α1A-2, pcDNA1α1A-2R192Q, pcDNA1α1A-2T666M, pcDNA1α1A-2V714A, or pcDNA1α1A-2I1815L together with pcDNA1α2bδ and pCMV2(-sd/sa)β2e or pCMV2(-sd/sa)β3a, and pCMVCD4 (Jurman et al., 1994). Transfections were performed using a standard calcium phosphate transfection procedure as described earlier (Brust et al., 1993). The CD4 expression plasmids were included to permit the identification of transfected cells (anti-CD4 Dynabeads; Dynal, Lake Success, NY). If cells transfected with wild-type or mutant subunits were kept for increasing time at 28°C before recording, the whole-cell current density was found to progressively increase with increasing time at 28°C. Cells were routinely kept at 28°C for 48–72 hr before whole-cell recordings and for 12–48 hr before single-channel recordings. In the latter case, the time at 28°C was less to increase the probability of recording from patches containing only one channel.

Patch-clamp recordings and data analysis. Whole-cell and single-channel patch-clamp recordings followed standard techniques (Hamill et al., 1981). All recordings were performed at room temperature (19–24°C). Whole-cell currents were recorded using an Axopatch-200A or an EPC-9 patch-clamp amplifier, low-pass filtered at 1 kHz (−3 dB, 8-pole Bessel filter) and digitized at a rate of 10 kHz. Pipettes had a resistance of 1.1–2.0 MΩ when filled with internal solution. Series resistance was 2–4 MΩ, and 70–90% series resistance compensation was generally used. The pipette solution contained (in mm): 135 CsCl, 10 EGTA, 1 MgCl2, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.3. The external solution contained (in mm): 15 BaCl2, 150 CholineCl, 1 MgCl2, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.3. Single-channel currents were recorded with a DAGAN 3900 patch-clamp amplifier, low-pass filtered at 1 kHz (−3 dB, 8-pole Bessel filter), sampled at 5 kHz, and stored for later analysis on a PDP-11/73 computer. All single-channel recordings were obtained in cell-attached configuration. The pipette solution contained (in mm): 90 BaCl2, 10 TEA-Cl, 15 CsCl, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 with TEA-OH. The bath solution contained (in mm): 140 K-gluconate, 5 EGTA, 35 l-glucose, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 with KOH. The high-potassium bath solution was used to zero the membrane potential outside the patch. All values given as mean ± SEM. The statistical significance of paired values was tested by an ANOVA followed by a post hoc t test.

Open-channel current amplitudes were measured by manually fitting cursors to well resolved channel openings. Values at each voltage are averages of many measurements. Open probability,po, was computed by measuring the average current (I) in a given single-channel current record and dividing it by the unitary single-channel current i. To obtain activation curves, po values were calculated by averaging the open probabilities measured in each sweep at a given voltage only in segments with single-channel activity in patches containing only one channel. A measure of the density of functional calcium channels in the membrane was obtained by counting the number of channels per patch in hundreds of cell-attached patches. The number of channels per patch was obtained by the method of maximum simultaneous openings at +30 or +40 mV, which was highly reliable under our conditions because the large majority of patches contained less than three channels (compare Fig. 3, legend), the open probability was sufficiently high (0.2 < po < 0.5), and null sweeps in single-channel patches were <8% (Horn, 1991). Given the large fraction of patches without channels, to be able to measure channel activity of certain mutants, it was necessary to increase the pipette tip diameter. To account for these changes, the average number of channels per patch was divided by the average membrane area under the pipette. The area of each patch, A (in square micrometers), was calculated from the pipette resistance, R, by using the equation A = 12.6 × (1/R+ 0.018) (Sakmann and Neher, 1983).

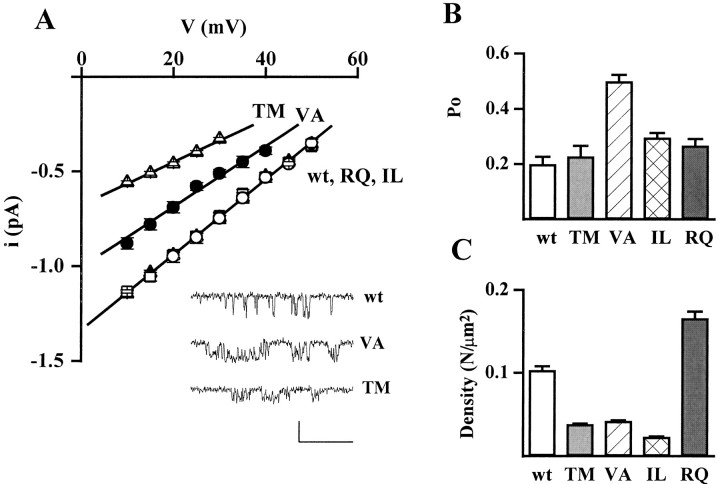

Fig. 3.

Effect of FHM mutations on single-channel current and conductance, open probability, and density of functional channels. Cell-attached patch-clamp recordings as in Figure 2. A, Unitary current–voltage,i–v, relationships of calcium channels containing wt and mutant human α1A-2 subunits. Unitary current values of wt (○), TM (▵), VA (•), IL (■), and RQ (▴) channels are averages from 8, 7, 9, 8, and 14 patches, respectively. For each patch, values of i at a given voltage are averages of many measurements on well resolved openings (compare insetshowing unitary activity at +20 mV on an expanded time scale; calibration: 40 msec, 1 pA). The values of i refer to the prevailing larger current level shown in the inset, which was much more frequently occupied with respect to other short-lived subconductance levels (particularly present in the VA mutant). The slope conductances of the average i–vrelationships are 20 pS for wt, IL, and RQ; 16 pS for VA; and 11 pS for TM. B, Open probability,po, at +30 mV of calcium channels containing wt and mutant human α1A-2 subunits. Averagepo values were obtained from the same patches from which the average i–v relationships were derived (n = 8, 7, 9, 8, and 14 patches for wt, TM, VA, IL, and RQ, respectively). The very similar average values of i for wt, RQ, and IL assure that the relatively small difference between the averagepo values of the three channels are not caused by any artifactual difference of voltage across the patches. All the patches contained only one channel. For each patch,po values were obtained by averaging the open probabilities measured in each sweep in segments with activity (n = 10–180). Statistical significance of differences with respect to wt: p ≪ 0.0001 for VA;p < 0.01 for IL; and p < 0.08 for RQ. C, Density of functional calcium channels containing wt and mutant human α1A-2 subunits. The density of functional channels was calculated from the average number of channel per patch and the average patch area in 144, 299, 192, 73, and 193 cell-attached patches on cells transfected with wt, TM, IL, RQ, and VA subunits, respectively. The average number of channel per patch in cells transfected with wt, TM, IL, RQ, and VA subunits was 0.98, 0.40, 0.30, 1.45, and 0.47, respectively. The corresponding average pipette resistance was 1.59 ± 0.09, 1.35 ± 0.05, 1.04 ± 0.03, 1.68 ± 0.08, and 1.29 ± 0.04 MΩ, respectively.

RESULTS

To investigate the functional consequences of four missense mutations in the human gene CACNA1A linked to FHM, we introduced the corresponding mutations in the human α1A-2Ca2+ channel subunit and coexpressed the wild-type (wt) or the mutant α1A-2 subunits in HEK293 cells together with human α2bδ and either human β3a or β2e subunits. As displayed in Figure1A, three of the four mutations are located in regions that are thought to form part of the pore (Armstrong and Hille, 1998): T666M is located in the P loop between S5 and S6 of domain II, V714A and I1815L are located at the intracellular end of the S6 segment in domains II and IV, respectively. The fourth mutation, R192Q, is located in the S4 segment of domain I, which forms part of the voltage sensor (Armstrong and Hille, 1998).

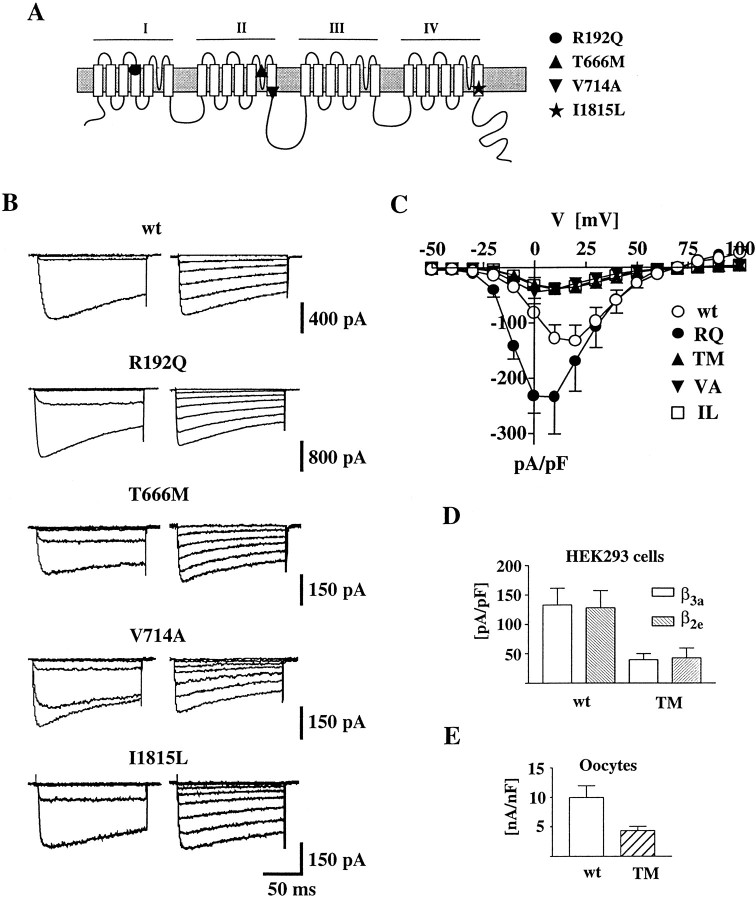

Fig. 1.

Whole-cell current of human recombinant calcium channels containing wt or mutant α1A subunits. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings with 15 mm Ba2+ as charge carrier from HEK293 cells transiently expressing calcium channels containing the wt human α1A-2 or human α1A-2R192Q, α1A-2T666M, α1A-2V714A, or α1A-2I1815L subunits together with the α2bδ and β3a subunits. Step depolarizations were delivered from a holding potential of −90 mV. The recordings were obtained from cells incubated at 28°C for 48–72 hr. A, Proposed secondary structure of Ca2+ channel α1 subunits with the approximate positions of the four FHM mutations indicated by differentsymbols. B, Representative families of Ba2+ currents elicited by step depolarizations between −50 and 0 mV (left panels) and +10 and +80 mV (right panels) in 10 mV increments. C, Voltage dependence of whole-cell current density for wt and mutant channels. The current density values, obtained by dividing current amplitudes and cell capacitance, are averages from 80, 25, 58, 62, and 55 cells for wt, RQ, TM, VA, and IL, respectively. D, Comparison of the average whole-cell current density at +10 mV measured in HEK293 cells transiently expressing calcium channels containing the wt human α1A-2 or human α1A-2TM subunit with the α2bδ and either the β3a or the β2e subunits. The current density values are averages from 80 and 16 cells expressing wt α1A-2 with β3a and β2e subunits, respectively, and from 58 and 5 cells expressing α1A-2TM with β3a and β2e subunits, respectively. With both β subunits, the difference in current density between wt and TM was statistically significant (p < 0.01).E, Comparison of the average whole-cell current density at +10 mV measured in Xenopus oocytes expressing calcium channels containing the wt α1A-2 or α1A-2TM subunit with the α2bδ and the β3asubunits. The current density values are averages from 10 and 8 oocytes expressing wt α1A-2 and α1A-2TM subunits, respectively. The difference was statistically significant (p < 0.01).

Representative families of Ba2+ currents recorded from HEK293 cells expressing wt or mutant R192Q (RQ), V714A (VA), T666M (TM), and I1815L (IL) channels are shown in Figure1B. The activation kinetics for wt and mutants were similar. At a test potential of +10 mV, the time constant for activation was 1.81 ± 1.3 msec (n = 12) for wt. Similar values were obtained for the four mutations [RQ, 2.00 ± 1.1 msec (n = 11); TM, 1.01 ± 0.36 (n = 10); VA, 1.4 ± 0.9 msec (n = 13); and IL, 1.56 ± 0.94 msec (n = 15)].

The maximal current density measured in cells expressing each of the four mutant channels was significantly different from that in cells expressing wt channels (Fig. 1C). The maximal current density for mutation RQ was larger than that for wt (193%,p < 0.05), whereas for mutations TM, VA, and IL, it was smaller than for wt (21, 25, and 29%, respectively;p < 0.05). Similar differences in maximal current density were found in cells expressing wt or mutant α1A-2TM subunits with either β3a or β2e subunits (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, a reduced current density of TM channels with respect to wt channels was found also when the expression system was changed from HEK293 cells toXenopus oocytes (Fig. 1E). Figure1C shows that the current–voltage relationships of the mutants RQ, VA, and IL were all shifted slightly in the hyperpolarizing direction with respect to wild-type, although each to a different extent.

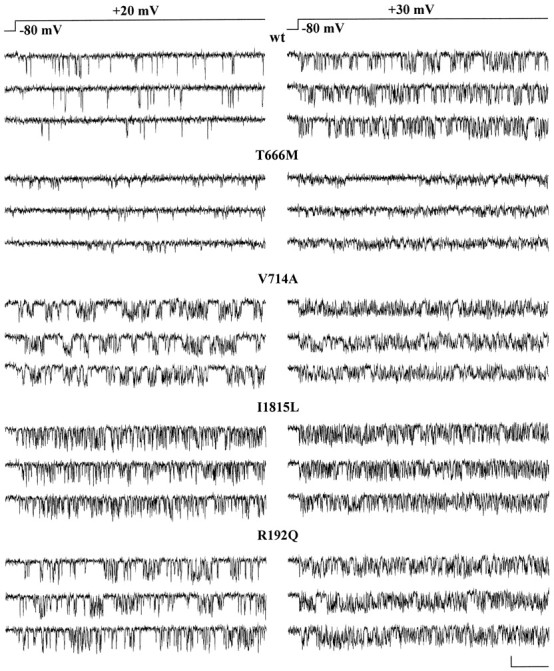

The differences in whole-cell current densities between wt and mutants, and among mutants, may be caused by different levels of expression of functional channels, and/or by different single-channel currents, and/or different single-channel open probabilities. To discriminate between these possibilities, we performed cell-attached single-channel recordings. Representative single-channel recordings from HEK293 cells expressing wt, mutant VA, TM, IL, or RQ channels are displayed in Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Single-channel activity of human recombinant calcium channels containing wt or mutant α1A subunits. Cell-attached patch-clamp recordings, with 90 mm Ba2+ as charge carrier, from HEK293 cells transiently expressing calcium channels containing the wt human α1A-2 or human α1A-2TM, α1A-2VA, α1A-2IL, or α1A-2RQ subunits together with the α2bδ and β2esubunits. Three representative current traces at +20 and +30 mV from single-channel patches on cells expressing calcium channels containing wt human α1A-2 (cell X24A), mutant human α1A-2TM (cell X29D), α1A-2VA (cell X35D), α1A-2IL (cell X51D), or α1A-2RQ subunit (cell X51C) are shown. Calibration: 80 msec, 0.5 pA. Depolarizations were delivered every 4 sec from a holding potential of −80 mV. The recordings were obtained from cells incubated at 28°C for 12–48 hr.

The TM and VA mutations affected the permeation properties of the channel. Both unitary current, i, and conductance, g, of TM and VA mutants were smaller than wt (Figs. 2,3A). The unitary current at +30 mV and the conductance of wt channels were 0.75 ± 0.03 pA and 19.5 ± 0.4 pS (n = 8), respectively, whereas those of the TM and VA channels were 0.33 ± 0.01 pA and 11.3 ± 0.3 pS (n = 7) and 0.51 ± 0.03 pA and 16.2 ± 0.2 pS (n = 9), respectively. The unitary current and conductance of IL and RQ mutants were not significantly different from wt (i = 0.73 ± 0.02 pA and g = 19.6 ± 0.3 pS, n = 8, for IL; i= 0.75 ± 0.01 pA and g = 20.2 ± 0.3 pS,n = 14, for RQ).

The mutation VA affected not only the permeation but also the gating properties of the channel (Figs. 2, 3B). The open probability, po, of the VA mutant was much greater than that of wt (251% at +30 mV). Also the IL and RQ mutants had a greater open probability than wt (149 and 134% at +30 mV), whereas the mutation TM did not significantly affectpo (Fig. 3B). Average open probabilities were obtained from patches containing only one channel. Only a minority (<8%) of sweeps were without activity (nulls), and the fraction of nulls was not significantly different for wt and mutant channels. The average open probability was obtained from traces with activity at +30 mV, without including nulls. The differences betweenpo of wt and mutants in Figure 3Bthen reflect changes in the voltage-dependent equilibrium between short-lived open and closed states in the activation pathway.

Judging from the frequency of patches without channels, all four FHM mutations appeared to affect the density of functional channels in the plasma membrane. The fraction of patches without activity was higher in cells expressing TM (78% of 299 patches), VA (77% of 193 patches), and IL (84% of 192 patches) mutants than in those expressing wt channels (67% of 144 patches), although pipettes with larger tip diameter were used for the mutants. On the other hand, the fraction of patches without channels was lower in cells expressing the RQ mutant (51% of 73 patches) with respect to those expressing wt, although on average the pipette tip was smaller. A measure of the density of functional channels was obtained by counting the number of channels per patch and dividing the average number of channels per patch by the average patch area, estimated as described in Materials and Methods (Thibault and Landfield, 1996). The number of channels per patch was obtained from the number of simultaneous overlapping openings at +30 or +40 mV. The large majority of patches contained either no channels or only one channel, and only <10% of the patches contained >3 channels in cells transfected with wt, TM, VA, and IL subunits. In cells transfected with RQ subunits, 22% of the patches contained >3 channels. Figure 3C shows that the density of functional RQ channels was higher (161%) than that of wt, whereas the density of functional VA, TM, and IL channels was lower than wt (41, 37, and 22%, respectively).

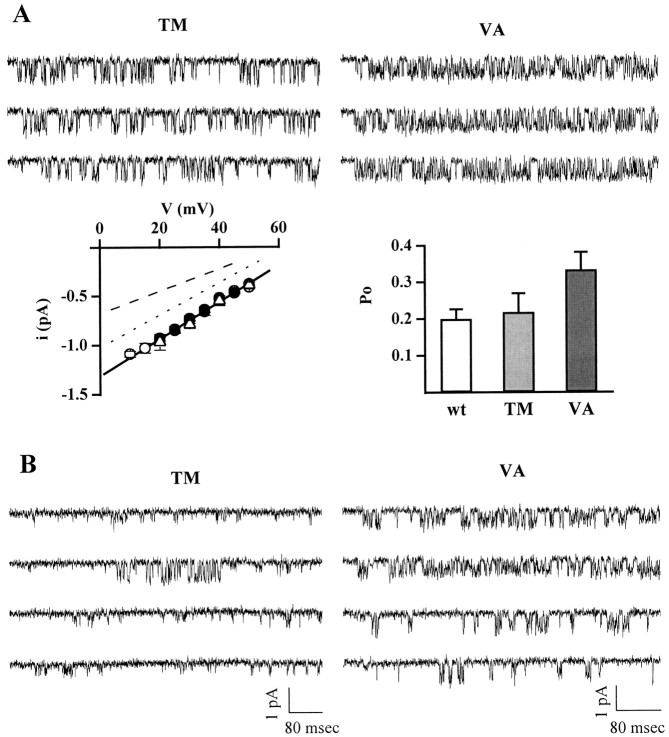

Figure 4A shows a quite surprising and interesting finding. In certain patches, the unitary current and conductance of TM and VA mutants were identical to those of wt channels and not smaller as found in most patches. Considering only patches with at most two or three channels, whose single-channel current and conductance could be accurately measured, 11% of TM channels (9 of 83 channels in 9 of 59 patches) and 33% of VA channels (10 of 30 channels in 10 of 25 patches) had single-channel current and conductance identical to wt for the entire duration of the recording. The open probability of TM channels with a conductance of 20 pS was similar to wt. The po of VA channels with a conductance of 20 pS was larger than that of wt (p < 0.02), but smaller than that of the more prevalent VA channels with conductance of 16 pS (p≪ 0.0001). In single-channel patches containing a TM channel with the prevailing conductance of 11 pS, very rare transitions to the larger conductance state were observed (Fig. 4B,left). The time spent in the larger conductance state was usually brief (<700 msec). In 21 single-channel patches containing a TM channel with conductance of 11 pS, only 8.5 sec of a total of 73 min at the test pulse voltage (0.2% of the time) were spent in the larger conductance state. In a unique single-channel patch, a mutant VA channel with the prevailing conductance of 16 pS shifted to the larger conductance state and remained in this state for 4.9 min (in a recording lasting 16 min) before shifting back to the low conductance state (Fig. 4B, right). Overall, in nine single-channel patches containing a VA channel with a conductance of 16 pS, 3.1% of the total recording time (158 min) was spent in the state with conductance of 20 pS.

Fig. 4.

Calcium channels containing human α1ATM and α1AVA subunits can be in a state with unitary current and conductance identical to wt. Cell-attached patch-clamp recordings from HEK293 cells transiently expressing calcium channels containing the human α1A-2TM or α1A-2VA subunits, together with the α2bδ and β2e subunits. Experimental conditions and protocol as in Figure 2. All recordings are from patches containing only one channel. A, Single-channel current traces at +30 mV of calcium channels containing the human α1A-2TM (cell X19E) and α1A-2VA (cell X44A) subunits, from patches in which the mutants had unitary current and conductance identical to wt, are shown together with their average current–voltage relationships (TM, ▵, n = 3; VA, ○, n = 8) and open probability at +30 mV (TM, n = 5; VA,n = 8). For comparison, the average current–voltage relationships (•, n = 8) and the open probability at +30 mV (n = 8) of wt channels are also shown. The dotted and dashed lines in the left panel are the lines best fitting the i–v relationships of the majority of VA and TM mutants, with conductance of 16 and 11 pS, respectively (compare Fig. 3). Calibration for traces as in B.B, Left, Consecutive single-channel current traces at +20 mV from a patch containing a single TM channel with the prevailing 11 pS conductance, showing a rare example of a transition from the lower conductance to the larger conductance state: cell X19A. Right, Representative current traces at +20 mV from a patch containing a single VA channel with the prevailing 16 pS conductance (top two traces), which shifted to the 20 pS conductance state (bottom two traces) during the recording: cell X37A. The transition from the low conductance to the wt conductance was observed only in one of nine single-channel patches.

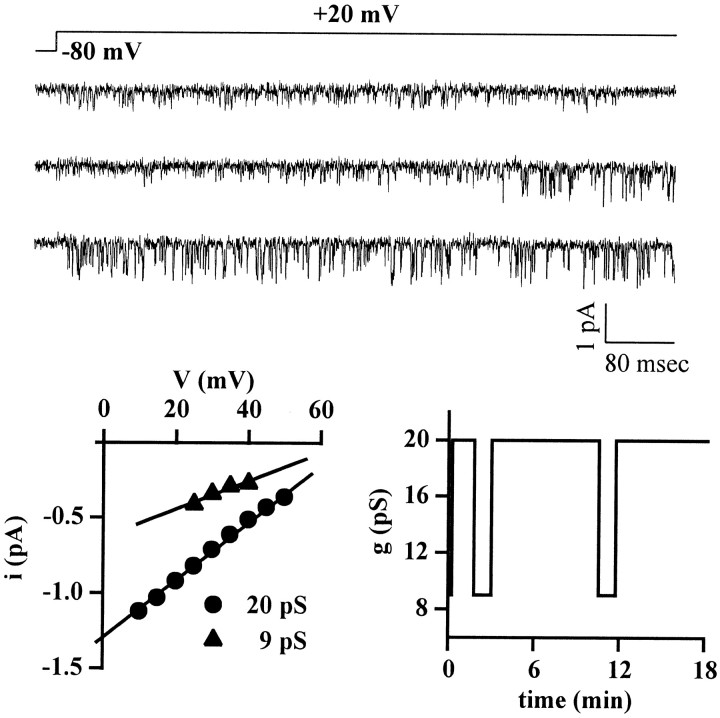

Interestingly, in single-channel patches containing a wt channel, very rare transitions to two different subconductance states with unitary currents similar to those measured for the majority of TM and VA channels were observed. The time spent in these smaller conductance states was usually brief (< 700 msec, but in a few instances could last up to two to four consecutive sweeps). In 16 single-channel patches containing a wt channel, only 10 and 5.9 sec of a total of 76 min at the test pulse voltage (0.2 and 0.1% of the time) were spent in the subconductance states with TM-like and VA-like unitary current, respectively. Transitions of the IL mutant to a long-lasting low conductance state, although rare, were more frequent than those of wt channels, and a single IL channel could spend long periods of time in the low conductance state. In the single-channel patch shown in Figure5, the same IL channel alternated between the prevailing conductance state of 20 pS and a state with lower conductance of 9 pS, as shown in the bottom right panel. In one of 11 single-channel patches, the IL mutant was in the low conductance state for the entire duration of the recording (20 min). In the remaining 10 patches, only 1.7% of the total recording time (158 min) was spent in the low conductance state.

Fig. 5.

Calcium channels containing the human α1AIL subunit can be in a state with unitary current and conductance smaller than wt. Cell-attached patch-clamp recordings from a HEK293 cell (cell X25A) transiently expressing calcium channels containing the human α1A-2IL subunit together with the α2bδ and β2e subunits. Experimental conditions and protocol as in Figure 2. The patch contained only one channel, which alternated between a prevailing state with unitary current and conductance identical to wt and a state with lower current and conductance. Single-channel current traces, showing a transition from the low conductance state to the state with wt conductance, are displayed together with the current–voltage relationships in the two states (left panel), and the time course with which the channel changed between the two states during the recording (right panel).

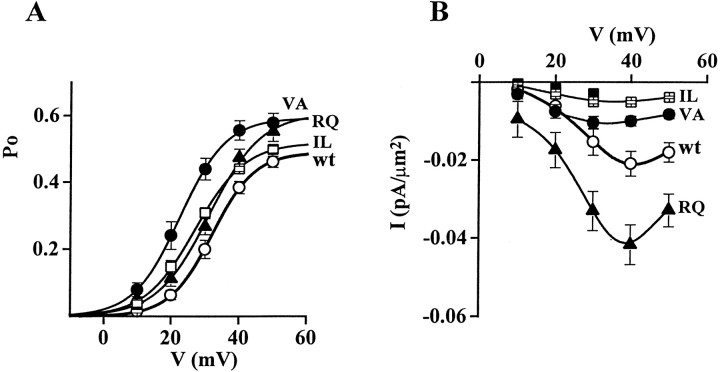

Figure 6A shows the open probability as a function of voltage of calcium channels containing wt or mutant α1A-2 subunits. The activation curve for the VA mutant was obtained by combining the average activation curves of VA mutants with 16 and 20 pS conductance, according to the relative fraction of channels with low and high conductance. This combined activation curve was shifted ∼10 mV in the hyperpolarizing direction with respect to wt. VA mutants in both conductance states had a larger maximum open probability than wt and were activated at more negative voltages than wt, but the activation curve of the mutant with 16 pS conductance was more shifted and had a larger maximum open probability than that of the mutant with 20 pS conductance (Fig. 6, legend). The VA mutation then has a twofold effect: it allows channel activation at more negative voltages and it increases single-channel open probability at all voltages. The IL mutation had similar effects but reduced in extent. The main effect of the RQ mutation was an increase of the open probability at all voltages.

Fig. 6.

Activation curves of human recombinant calcium channels containing wt or mutant α1A subunits. Cell-attached patch-clamp recordings as in Figure 2 from patches containing only one channel. A, Voltage dependence of the open probability, po, of single calcium channels containing wt or mutant α1A-2 subunits. The curves were obtained by averaging at each voltage the values ofpo measured in different single-channel patches: n = 8 for wt (○), n= 16 for VA (•), n = 6 for IL (■), andn = 14 for RQ (▴). The VA curve was obtained by combining the activation curves of mutant channels with 16 pS conductance (n = 8) and 20 pS conductance (n = 8), according to the relative fraction of channels with low (67%) and high (33%) conductance. The data points were fitted by Boltzmann distributions of the formpo = po,max × (1 + exp (− (V −V1/2)/k)) withV1/2 = 32.1 mV, k = 6.2,po,max = 0.489 for wt;V1/2 = 23, k = 6.8,po,max = 0.592 for VA;V1/2 = 27.1, k = 7.3,po,max = 0.518 for IL; andV1/2 = 31.2, k = 7.6,po,max = 0.605 for RQ. The parameters of the Boltzmann distribution functions fitting the average activation curve of VA mutants with 16 and 20 pS conductance wereV1/2 = 20.3 and 28.3 mV,k = 5.8 and 7.6, andpo,max = 0.583 and 0.626, respectively. For the TM mutant, average values of po at +10 mV (0.019 ± 0.005, n = 5), +20 mV (0.089 ± 0.010, n = 5), and +30 mV (0.200 ± 0.014,n = 7) were not significantly different from wt (data not shown). B, Voltage dependence of macroscopic current density obtained from the single-channel data by multiplying the channel density and the unitary current, i, and open probability, po, at each voltage. Symbols: wt (○), VA (•), IL (■), RQ (▴), and TM (▪). The VA and TM data points were obtained by combining the values ofi and po of channels with low and high conductance, according to the relative fractions (11 and 89% for TM, 33 and 67% for VA).

Figure 6B shows the voltage dependence of the macroscopic current density obtained from the single-channel data by multiplying the channel density and the unitary current, i, and open probability, po, at each voltage. Comparison with the analogous plot in Figure 1, obtained from whole-cell recordings, shows a reasonably good agreement, taking into account a shift of ∼30 mV, caused by the different concentration of charge carrier in single-channel and whole-cell recordings (90 vs 15 mm Ba2+). Thus, we can conclude that the increased whole-cell current density observed with the RQ mutant is mainly caused by an increased expression of functional calcium channels and, to a lesser extent, to an increased open probability at each voltage compared with wt. On the other hand, the decreased whole-cell current density in cells transfected with the α1A-2VA and α1A-2IL subunits is mainly caused by a decreased expression of functional calcium channels, and in those transfected with α1A-2TM to both a decreased expression of functional calcium channels and a reduced single-channel current. The decreased single-channel current in the channels containing the α1A-2VA subunit is more than compensated by the increased open probability of these channels.

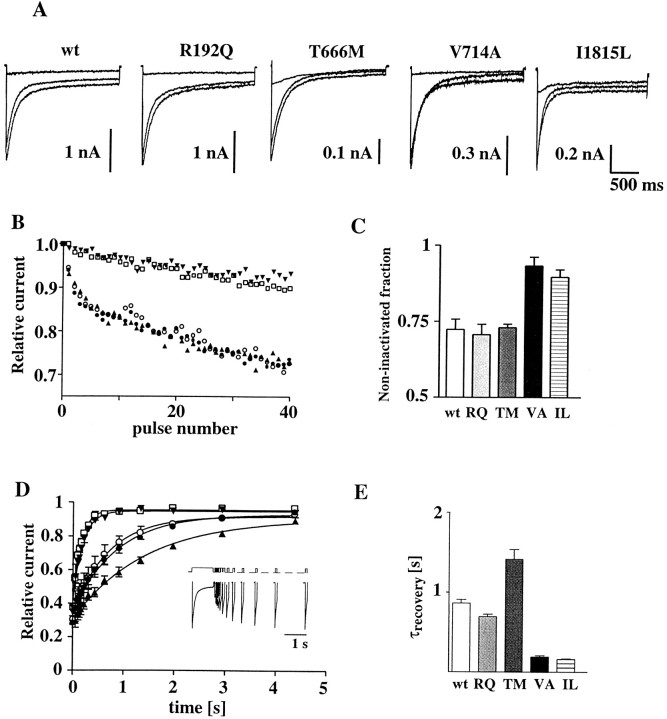

To investigate whether the mutations affect channel inactivation, we determined inactivation kinetics under two conditions. Figure7A illustrates the inactivation kinetics of the wt and the four mutant channels during 2 sec depolarizations. Inactivation kinetics were best fit with the sum of two exponential components. The time constants and relative contributions of the two components were not significantly different among wt, RQ, VA, and TM mutants (Fig. 7, legend). For the IL mutant, both the time constant and the amplitude of the slower component were significantly different from wt (304 ± 55 msec, 34.1 ± 5.3% vs 540 ± 47 msec, and 15.8 ± 3.6% at +10 mV; p < 0.05), but in opposite directions. As a result, the fraction of current remaining at the end of the 2 sec pulse was slightly larger for the IL mutant compared with wt or the other three mutant channels. However, when a series of 40 short step depolarizations were applied at 3 Hz, the fraction of current remaining at the end of the train was considerably larger for both the IL and VA mutants compared with wt (Fig.7B,C). Thus, both the IL and VA mutants inactivated less than wt during the train of short depolarizations. The smaller fractional inactivation of the IL and VA mutants is caused by a faster rate of recovery from inactivation (Fig.7D,E). The time course of recovery from inactivation was measured using a double-pulse protocol, in which a short test depolarization was applied at various times after a conditioning 1 sec long depolarization to +10 mV from a holding potential of −90 mV (Fig. 7D). The data points were fitted with a single exponential function. The time constant of recovery from inactivation was smaller than wt for both IL and VA (18 and 23% of the wt value), whereas it was larger for TM (165%). Similar effects of the FHM mutations on the time course of recovery from inactivation were observed with calcium channels containing rabbit α1Aexpressed in Xenopus oocytes with α2bδ and β1a subunits (Kraus et al., 1998).

Fig. 7.

Inactivation properties of human recombinant calcium channels containing wt or mutant α1Asubunits. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings with 15 mm Ba2+ as charge carrier from HEK293 cells transiently expressing calcium channels containing the wt human α1A-2or human α1A-2RQ, α1A-2TM, α1A-2VA, or α1A-2IL subunits together with the α2bδ and β3a subunits.A, Example Ba2+ current traces elicited by 2 sec step depolarizations to −10, 0, and +10 mV from a holding potential of −90 mV. The average time constants for current inactivation at +10 mV, τ1 and τ2, obtained by fitting the current traces to a biexponential function of the form I = A0 + A1exp(−t/τ1) + A2exp(−t/τ2), were 58.1 ± 16.6 and 540 ± 47 msec for wt (n = 7), 51.0 ± 9.2 and 423 ± 63 msec for RQ (n = 6), 62.6 ± 7.1 and 402 ± 54 msec for TM (n= 6), 43.6 ± 20.0 and 472 ± 84 msec for VA (n = 5), and 65.2 ± 16 and 304 ± 55 msec for IL (n = 7). The average fraction of current associated with the fast component was 76 ± 6, 75 ± 4, 62 ± 3, 76 ± 4, and 46 ± 8% for wt, RQ, TM, VA, and IL, respectively. The average fraction of current remaining at the end of a 2 sec depolarization to +10 mV was 8 ± 3, 7 ± 1, 13 ± 2, 12 ± 2, and 20 ± 5% for wt, RQ, TM, VA, and IL, respectively. B, Representative time course of inactivation of wt and mutant channels during a series of 40-msec-long step depolarizations to +10 mV at 3 Hz. Holding potential was −90 mV. The data points represent peak currents in each consecutive depolarization, expressed asI(n)/I(n = 1). Symbols: wt (○), RQ (•), TM (▴), VA (▾), and IL (■). C, Fraction of noninactivated current at the end of 40 step depolarizations to +10 mV. Mutations VA and IL are significantly different from wt (p < 0.01).D, Time course of recovery from inactivation after a 1 sec step depolarization to +10 mV. Lines through the data points represent single exponential best fits. The average time constants of recovery from inactivation for wt and the mutants are shown in E. Recovery from inactivation was measured using the double-pulse protocol shown in the inset, in which a 50 msec long test depolarization at +10 mV was applied at variable times after the 1 sec depolarization at the same voltage. Representative current traces recorded from wt using this voltage protocol are also shown in the inset. Holding potential was −90 mV. E, Time constant of recovery from inactivation. The time constants for VA, IL, and TM are significantly different from wt (p < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

We have studied the functional consequences of four missense mutations linked to FHM, by combining single-channel and whole-cell recordings on HEK293 cells transiently expressing calcium channels containing wt or mutant human α1A-2 subunits together with α2bδ and either β2e or β3a subunits. We have shown that all four mutations affect both the biophysical properties and the density of functional channels in the membrane.

Mutation TM, located in the pore-lining region, the P loop of domain II, reduced the single-channel current and conductance to approximately half (from 20 to 11 pS), without affecting the single-channel open probability. The effect on channel permeation of mutation TM was not unexpected, given its close proximity to one of the key glutamates that form the high-affinity binding site for divalent ions (Tang et al., 1993a; Yang et al., 1993). However, strikingly, in a minority of single-channel patches, the TM mutant had single-channel current and conductance identical to wt. The single-channel conductance was reduced also by mutation VA, located at the intracellular end of the S6 segment of domain II. This finding supports the idea that the S6 segments in Ca2+ channels contribute to the lining of the part of the pore internal to the selectivity filter (Hockerman et al., 1997). The majority of channels containing the α1A-2VA subunit had single-channel conductance of 16 pS. However, similar to the TM mutation, a certain fraction of VA channels had the same current and conductance as wt. This surprising finding suggests that the TM and VA channels can assume two stable conformations, one with conductance lower than wt and the other with the same conductance as wt. The presence or absence in the patch of an unknown factor interacting with the channel might determine which of the two conformations is taken on. Although mutation IL is located at the intracellular end of the S6 segment of domain IV in a position similar to that of VA, almost all the channels containing the α1A-2IL subunit had single-channel current and conductance identical to that of wt. However, in contrast with wt channels, IL mutants could spend long periods of time in a state with lower conductance.

Both mutations in S6 segments (but VA to a larger extent than IL) shifted the voltage range of channel activation toward more negative voltages and increased the single-channel open probability at all voltages. These findings may be consistent with the idea, put forward for K+ channels (Liu et al., 1997; Armstrong and Hille, 1998), that there is an activation gate on the intracellular end of the pore that regulates communication between the intracellular solution and the pore-lining part of S6. Both mutations also increased the rate of recovery from inactivation, and consequently calcium channels containing the α1A-2VA and α1A-2IL subunits inactivated less than wt during trains of short depolarizations at 3 Hz. This effect of mutations VA and IL is consistent with previous evidence for the involvement of S6 segments in inactivation of Ca2+ channels (Tang et al., 1993b;Zhang et al., 1994; Hering et al., 1996; Kraus et al., 1998). Mutations located in similar position in S6 segments of muscle Na+ channels have been linked to different types of periodic muscle paralysis and have been shown to increase the contribution of a slowly inactivating component of Na+ current and to speed up recovery from inactivation (Cannon, 1996; Hayward et al., 1997). Interestingly, also mutation TM, located close to the selectivity filter, affected the rate of recovery from inactivation, but in the opposite direction than the mutations in S6 segments.

Mutation RQ, located in the voltage sensor S4 segment of domain I, increased the open probability at all voltages without affecting single-channel current and conductance. Although the three mutations in the pore region decreased the density of functional channels in the membrane, mutation RQ had the opposite effect and almost doubled channel density. The effect of the FHM mutations on the density of functional channels in HEK293 cells suggests that the FHM mutations may change the level of expression of P/Q-type calcium channels in neurons.

The question of whether the four FHM mutations lead to gain- or loss-of-function in terms of Ca2+ influx does not have a simple and univocal answer, as shown in Table1. Mutation TM leads to a reduction of Ca2+ influx (loss-of-function) and mutation RQ to an increase of Ca2+ influx (gain-of-function), whether the function of the single calcium channel or the density of functional channels are considered. On the other hand, mutations VA and IL lead to an overall gain-of-function at the single-channel level, given the higher open probability and the faster rate of recovery from inactivation, whereas they may lead to an overall loss-of-function at the level of the whole-cell calcium current, given the decreased density of functional channels. Considering the possibility that these FHM mutations may differentially affect the expression of P/Q-type calcium channels in different neurons, then a possible implication of our finding is that the VA and IL mutations may lead to either an increased or a decreased Ca2+ influx, depending on the type of neuron. In this context, it is interesting to note that mutation TM affected the density of functional channels much more when the mutant channels were expressed in HEK293 cells than in oocytes. In fact, the decrease in current density observed in oocytes can be almost completely accounted for by the decrease in single-channel current produced by the mutation (assuming that the fraction of mutant channels with conductance similar to wt is not altered when expressed inXenopus oocytes).

Table 1.

Effect of FHM mutations on Ca2+ influx

| Channel density | Single channel current | Open probability | Inactivation during train of pulses | Recovery from inactivation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TM | ↓↓ | ↓↓(-) | – | – | ↓ |

| VA | ↓↓ | ↓(-) | ↑↑ | ↑↑ | ↑↑ |

| IL | ↓↓↓ | –(↓) | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↑↑ |

| RQ | ↑↑ | – | ↑ | – | – |

The table shows how the changes in functional properties of human recombinant Ca2+ channels produced by FHM mutations are predicted to affect Ca2+ influx into neurons. An increased, a decreased, or an unchanged Ca2+ influx with respect to wild type is indicated with ↑, ↓, and –, respectively. The smaller symbols in parentheses refer to the function of a minority of mutants.

Calcium channels containing the α1A subunit have been shown to be expressed throughout the human and rat brain with a high concentration in the cerebellum and to be localized in most presynaptic terminals and also in the cell body and dendrites of many neurons (Volsen et al., 1995; Westenbroek et al., 1995). P/Q type calcium channels have been shown to play a prominent role in controlling neurotransmitter release in many synapses (Dunlap et al., 1995). Their localization also in dendrites and cell bodies suggests additional postsynaptic roles (Llinas et al., 1992).

Although an established model that explains migraine attacks is still lacking, a favored hypothesis considers a persistent state of hyperexcitability of neurons in the cerebral cortex as the basis for susceptibility to migraine (Flippen and Welch, 1997; Welch, 1998). This state would favor the onset of cortical spreading depression, which is believed to initiate the attacks of migraine with aura (Lauritzen, 1996; Welch, 1998). Given the involvement of calcium channels containing the α1A subunit in a multiplicity of Ca2+-dependent functions and their wide distribution throughout the brain, it is difficult to predict the effect of the mutations on overall neuronal excitability. An increased postsynaptic neuronal excitability may result from both loss- or gain-of-function variants of presynaptic P/Q-type channels controlling release of inhibitory or excitatory neurotransmitters, respectively. Moreover, one can envision different mechanisms with which neuronal excitability can be increased and/or the development of cortical spreading depression can be facilitated by either loss- or gain-of-function variants of postsynaptic P/Q-type channels. It has been suggested that serotonin [5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)] plays a central role in the pathophysiology of migraine (Ferrari and Saxena, 1993). A defective release of serotonin, which has a predominant inhibitory postsynaptic action in the brain (Jacobs and Azmitia, 1992), would possibly predispose patients to migraine attacks and to development of headache after an attack. Although the mechanism of pain generation in migraine is still unclear, effective specific acute anti-migraine drugs all share the ability to stimulate 5-HT1 receptors of the trigeminovascular system (Moskowitz, 1992; Schoenen, 1997).

The episodic nature of the disease might be explained purely by the mutant channels providing a continuous background of neuronal instability. However, our finding that the functional effect of the mutations on single channels was not present in some patches or periods of activity, suggests the interesting possibility that some unknown factor can precipitate an attack by directly switching the abnormal channel on or off.

Progressive cerebellar ataxia has been reported in three of eight of the FHM families linked to mutations in the gene encoding the α1A subunit (Ophoff et al., 1996; Terwindt et al., 1998). Interestingly, the FHM families with cerebellar ataxia had either the TM or the IL mutation, the two mutations that, on the basis of our data, are predicted to result in a decreased Ca2+influx into cerebellar neurons at all voltages. Thus, our data suggest a link between the ataxia phenotype and loss-of-function of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels, caused by either a decreased density of functional channels (IL) or both a decreased density and decreased single-channel conductance (TM). The conclusion that mutations in P/Q-type channels cause the ataxia phenotype through a loss-of-function mechanism (haploinsufficiency) is supported by the severe ataxic phenotype of leaner mutant mice. In these mice, a missense mutation in a splice donor consensus sequence of the gene encoding the α1A subunit gives rise to aberrant transcripts (Fletcher et al., 1996; Doyle et al., 1997) and to a reduced P-type current in Purkinje cells (Dove et al., 1998; Lorenzon et al., 1998).

Footnotes

This work was supported by Telethon-Italy Grant 720 to D.P. and a grant from the Regione del Veneto (Giunta Regionale Ricerca Sanitaria Finalizzata-Venezia-Italia). We thank C. C. Lu and S. Morales for preparation of α1A mutant constructs and A. Nesterova for excellent technical assistance.

Drs. Hans and Luvisetto contributed equally to this work.

Correspondence should be addressed to Daniela Pietrobon, Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Padova, Viale Colombo 3, 35121 Padova, Italy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong CM, Hille B. Voltage-gated ion channels and electrical excitability. Neuron. 1998;20:371–380. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80981-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brust PF, Simerson S, McCue AF, Deal CR, Schoonmaker S, Williams ME, Velicelebi G, Johnson EC, Harpold MM, Ellis SB. Human neuronal voltage-dependent calcium channels: studies on subunit structure and role in channel assembly. Neuropharmacology. 1993;32:1089–102. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90004-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cannon SC. Sodium channel defects in myotonia and periodic paralysis. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1996;19:141–164. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diriong S, Lory P, Williams ME, Ellis SB, Harpold MM, Taviaux S. Chromosomal localization of the human genes for α1A, α1B, and α1E voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel subunits. Genomics. 1995;30:605–609. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dove LS, Abbott LC, Griffith WH. Whole-cell and single-channel analysis of P-type calcium current in cerebellar Purkinje cells of leaner mutant mice. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7687–7699. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-19-07687.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doyle J, Ren X, Lennon G, Stubbs L. Mutations in the CACNL1A4 calcium channel gene are associated with seizures, cerebellar degeneration, and ataxia in tottering and leaner mutant mice. Mamm Genome. 1997;8:113–120. doi: 10.1007/s003359900369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunlap K, Luebke JI, Turner TJ. Exocytotic Ca2+ channels in mammalian central neurons. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:89–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dupere JRB, Moya E, Blagbrough IS, Usowicz MM. Differential inhibition of Ca2+ channels in mature rat cerebellar Purkinje cells by sFTX-3.3 and FTX-3.3. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00156-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrari MD, Saxena PR. On serotonin and migraine: a clinical and pharmacological review. Cephalalgia. 1993;13:151–165. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1993.1303151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fletcher CF, Lutz CM, O’Sullivan TN, Shaughnessy JDJ, Hawkes RH, Frankel WN, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA. Absence epilepsy in Tottering mutant mice is associated with calcium channel defects. Cell. 1996;87:607–617. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flippen C, Welch KMA. Imaging the brain of migraine sufferers. Curr Opin Neurol. 1997;10:226–230. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199706000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gillard SE, Volsen SG, Smith W, Beattie RE, Bleakman D, Lodge D. Identification of pore-forming subunit of P-type calcium channels: an antisense study on rat cerebellar Purkinje cells in culture. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:405–409. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamill O, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth F. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayward LJ, Brown RH, Cannon SC. Slow inactivation differs among mutant Na channels associated with myotonia and periodic paralysis. Biophys J. 1997;72:1204–1219. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78768-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hering S, Aczel S, Grabner M, Doring F, Berjukow S, Mitterdorfer J, Sinneger MJ, Striessnig J, Degtiar VE, Wang Z, Glossman H. Transfer of high sensitivity for benzothiazepines from L-type to class A (BI) calcium channels. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24471–24475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho SN, Hunt HD, Horton RM, Pullen JK, Pease LR. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hockerman GH, Johnson BD, Abbott MR, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular determinants of high affinity phenylalkylamine block of L-type calcium channels in transmembrane segment IIIS6 and the pore region of the α1 subunit. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18759–18765. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horn R. Estimating the number of channels in patch recordings. Biophys J. 1991;60:433–439. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82069-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobs BL, Azmitia EC. Structure and function of the brain serotonin system. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:165–216. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jurman ME, Boland LM, Liu Y, Yellen G. Visual identification of individual transfected cells for electrophysiology using antibody-coated beads. Biotechniques. 1994;17:876–881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kraus RL, Sinnegger MJ, Glossmann H, Hering S, Striessnig J. Familial hemiplegic migraine mutations change α1A Ca2+ channel kinetics. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5586–5590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lauritzen M. Pathophysiology of the migraine aura. Sci Med. 1996;3:32–41. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y, Holmgren M, Jurman ME, Yellen G. Gated access to the pore of a voltage-dependent K+ channel. Neuron. 1997;19:175–184. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Llinas R, Sugimori M, Hillman DE, Cherksey B. Distribution and functional significance of the P-type, voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in the mammalian central nervous system [Review]. Trends Neurosci. 1992;15:351–355. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90053-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorenzon NM, Lutz CM, Frankel WN, Beam KG. Altered calcium channel currents in Purkinje cells of the neurological mutant mouse leaner. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4482–4489. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04482.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.May A, Ophoff RA, Terwindt GM, Urban C, Van Eijk R, Haan J, Diener HC, Lindhout D, Frants RR, Sandkuijl LA, Ferrari MD. Familial hemiplegic migraine locus on 19p13 is involved in the common forms of migraine with and without aura. Hum Genet. 1995;96:604–608. doi: 10.1007/BF00197420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mintz IM, Venema VJ, Swiderek KM, Lee TD, Bean BP, Adams ME. P-type calcium channels blocked by the spider toxin ω-Aga-IVA. Nature. 1992;355:827–829. doi: 10.1038/355827a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mori Y, Friedrich T, Kim MS, Mikami A, Nakai J, Ruth P, Bosse E, Hofmann F, Flockerzi V, Furuichi T, Mikoshiba K, Imoto K, Tanabe T, Numa S. Primary structure and functional expression from complementary DNA of a brain calcium channel. Nature. 1991;350:398–402. doi: 10.1038/350398a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moskowitz MA. Neurogenic versus vascular mechanisms of sumatriptan and ergot alkaloids in migraine. Trends Pharmacol. 1992;13:307–311. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90097-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ophoff RA, Terwindt GM, Vergouwe MN, van Eijk R, Oefner PJ, Hoffman SMG, Lamerdin JE, Mohrenweiser HW, Bulman DE, Ferrari M, Haan J, Lindhout D, van Hommen G-JB, Hofker MH, Ferrari MD, Frants RR. Familial hemiplegic migraine and episodic ataxia type-2 are caused by mutations in the Ca2+ channel gene CACNL1A4. Cell. 1996;87:543–552. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81373-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piedras-Renteria ES, Tsien RW. Antisense oligonucleotide against α1E reduce R-type calcium currents in cerebellar granule cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7760–7765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinto A, Gillard S, Moss F, Whyte K, Brust P, Williams M, Stauderman K, Harpold M, Lang B, Newsom-Davis J, Bleakman D, Lodge D, Boot J. Human autoantibodies specific for the α1A calcium channel subunit reduce both P-type and Q-type calcium currents in cerebellar neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8328–8333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Randall A, Tsien RW. Pharmacological dissection of multiple types of Ca2+ channel currents in rat cerebellar granule neurons. J Neurosci. 1995;15:2995–3012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-02995.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakmann B, Neher E. Geometric parameters of pipettes and membrane patches. In Single-channel recording (Sakmann B, Neher E, eds), pp 37–51. Plenum; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schoenen J. Acute migraine therapy: the newer drugs. Curr Opin Neurol. 1997;10:237–243. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199706000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Starr TV, Prystay W, Snutch TP. Primary structure of a calcium channel that is highly expressed in the rat cerebellum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5621–5625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang S, Mikala G, Bahinski A, Yatani A, Varadi G, Schwartz A. Molecular localization of ion selectivity sites within the pore of a human L-type cardiac calcium channel. J Biol Chem. 1993a;268:13026–13029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang S, Yatani A, Bahinski A, Yasuo M, Schwartz A. Molecular localization of regions in the L-type calcium channel critical for dihydropyridine action. Neuron. 1993b;11:1013–1021. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90215-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terwindt GM, Ophoff RA, Haan J, Vergouwe MN, van EijK R, Frants RR, Ferrari MD. Variable clinical expression of mutations in the P/Q-type calcium channel gene in familial hemiplegic migraine. Neurology. 1998;50:1105–1110. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.4.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thibault O, Landfield PW. Increase in single L-type calcium channels in hippocampal neurons during aging. Science. 1996;272:1017–1020. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5264.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tottene A, Moretti A, Pietrobon D. Functional diversity of P-type and R-type calcium channels in rat cerebellar neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6353–6363. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06353.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Usowicz MM, Sugimori M, Cherskey B, Llinas R. P-type calcium channels in the somata and dendrites of adult cerebellar Purkinje cells. Neuron. 1992;9:1185–1199. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90076-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Volsen SG, Day NC, McCormack AL, Smith W, Craig PJ, Beattie R, Ince PG, Shaw PJ, Ellis SB, Gillespie A, Harpold MM, Lodge D. The expression of neuronal voltage-dependent calcium channels in human cerebellum. Mol Brain Res. 1995;34:271–282. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00234-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Welch KMA. Current opinions in headache pathogenesis: introduction and synthesis. Curr Opin Neurol. 1998;11:193–197. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199806000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Westenbroek RE, Sakurai T, Elliott EM, Hell JW, Starr TVB, Snutch TP, Catterall WA. Immunochemical identification and subcellular distribution of the α1A subunits of brain calcium channels. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6403–6418. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06403.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang J, Ellinor PT, Sather WA, Zhang J-F, Tsien RW. Molecular determinants of Ca2+ selectivity and ion permeation in L-type Ca2+ channels. Nature. 1993;366:158–161. doi: 10.1038/366158a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang J-F, Ellinor PT, Aldrich RW, Tsien RW. Molecular determinants of voltage-dependent inactivation in calcium channels. Nature. 1994;372:97–100. doi: 10.1038/372097a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhuchenko O, Bailey J, Bonnen P, Ashizawa T, Stockton DW, Amos C, Dobyns WB, Subramony SH, Zoghbi HY, Lee C. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia (SCA6) associated with small polyglutamine expansions in the α1A-voltage-dependent calcium channel. Nat Genet. 1997;15:62–69. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]