Abstract

S100A9 was originally regarded as a regulator of immune response and a mediator of the inflammatory process. Recent studies have suggested that S100A9 expression plays an important role during tumor development, progression and metastasis in various cancers. The present study aimed to investigate the expression and prognostic role of S100A9 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC).

S100A9 expression was examined by immunohistochemical staining in 152 patients who underwent surgical resection due to ccRCC. The correlation between S100A9 expression and clinicopathological data and its prognostic role were evaluated in patients with ccRCC.

S100A9 revealed high expression in 37 cores (12.6%) of ccRCC. S100A9 expression was significantly associated with T stage (P < .001) and Fuhrman nuclear grade (P < .001), but not with patient age (P = .821) and sex (P = .317). Survival analysis revealed that high S100A9 expression is an independent factor for unfavorable disease-free survival (hazard ratio, 2.423; 95% confidence interval, 1.044–5.621; P = .039) and disease-specific survival (hazard ratio, 2.428; 95% confidence interval, 1.130–5.214; P = .023) in patients with ccRCC.

S100A9 expression can be a useful prognostic factor in patients with ccRCC.

Keywords: carcinoma, clear cell, kidney, prognosis, S100A9

1. Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a major lethal genitourinary malignancy.[1] Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) is the most common histologic type of RCC, and accounts for 70% to 85% of cases of RCC.[2,3] Despite dramatic advancement in treatment over the past decade, many ccRCC patients experience disease progression after surgery and/or combined treatment.[1,3] Therefore, recognition of new factors related to disease progression is essential for improving treatment results and patient survival.[4]

S100A9 is a calcium-binding protein and was originally regarded as a regulator of the immune response and a mediator of the inflammatory process.[5] More recent data have suggested that S100A9 may play an important role during tumor development and that S100A9 is highly expressed and/or plays a prognostic role in various cancers, including lung, gastric, colorectal, pancreatic, breast, prostate, and oropharyngeal cancer.[5–9] Moreover, some researchers have demonstrated that S100A9 is involved in tumor proliferation, invasion, and metastasis, and enhances pre-metastatic niche formation.[10–12] However, to our knowledge, no report has assessed the prognostic significance of S100A9 in ccRCC.

Therefore, in the present study, for the first time, we evaluated the expression and prognostic role of S100A9 in ccRCC, using tissue microarray-based on immunohistochemical staining.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients and clinicopathological data

One hundred fifty-two patients with ccRCC were enrolled in this study. The patients underwent surgical resection for ccRCC at the Gyeongsang National University Hospital (Jinju, Korea) between January 2000 and December 2009, consecutively. Tumors were staged according to the guidelines of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Tumor Node Metastasis Classification of Malignant Tumors, eighth edition. Clinical data were extracted from electronic medical records. Recurrence was diagnosed pathologically via surgical biopsy and/or radiologically via computed tomography or positron emission tomography. Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as the period from the date of surgery to the date of cancer recurrence, while disease-specific survival (DSS) was defined as the period from the date of surgery to the date of death, which was mostly due to ccRCC. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Gyeongsang National University Hospital (2018-07-005) and was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

2.2. Tissue microarray construction and immunohistochemistry

Hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides were examined, and 2 cores of 2 mm were obtained from each case in the representative formalin-fixed, paraffin block. In total, 304 cores were made. Immunohistochemical staining was performed using the automated immunostainer (Benchmark Ultra, Ventana Medical Systems Inc, Tucson, AZ) with monoclonal anti-S100A9 antibody at a 1:250 dilution (EPR3555, Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Lymphoid cells in the tonsil were used as positive control, and the omitted primary antibody was used as negative control.

2.3. S100A9 expression

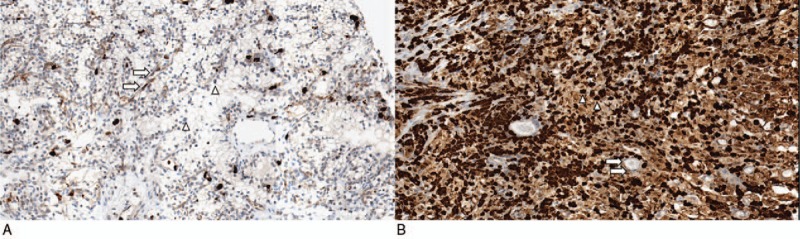

Immunohistochemical staining was evaluated in the nucleus for S100A9 in the tumor cells (Fig. 1A and B). The staining result of the tumor cells was graded as either low expression or high expression. If more than 25% of tumor cells stained stronger than capillary endothelial cells, it was regarded as having a high expression, while others were regarded as having low expression. For tumor cells that showed heterogeneous expression in the same core, the representative value was determined according to the majority of tumor cells. To confirm reproducibility, all samples were individually reviewed by 2 pathologists.

Figure 1.

Examples of immunohistochemical staining of S100A9 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. (A) Low S100A9 expression. Tumor cells show weaker expression compared with capillary endothelial cells (B) High S100A9 expression. Tumor cells reveal stronger expression compared with capillary endothelial cells (arrow, endothelial cells; arrow head, tumor cells; original magnification: 200×).

2.4. Statistical analysis

The correlation between S100A9 expression and clinicopathological data was assessed using the Pearson Chi-square test. DFS and DSS were analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method with the log-rank test. The prognostic significance of clinicopathological data for DFS and DSS was evaluated using the Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. A P-value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. The analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

3. Results

3.1. Clinicopathological data of the patients

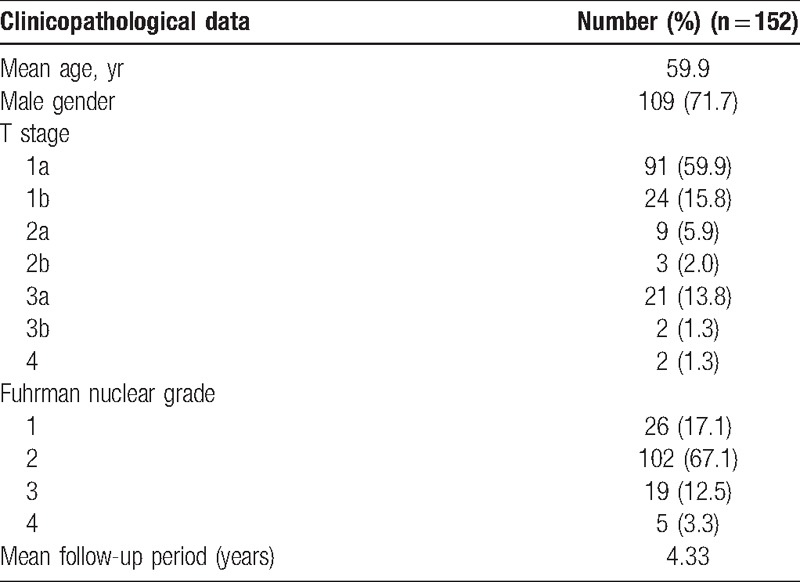

The clinicopathological data of the patients are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 59.9 (range: 32–83) years. The T stages of the tumors of the patients were as follows: 1a in 91 (59.9%), 1b in 24 (15.8%), 2a in 9 (5.9%), 2b in 3 (2.0%), 3a in 21 (13.8%), 3b in 2 (1.3%), and 4 in 2 (1.3%). The Fuhrman nuclear grades were as follows: 26 (17.1%) were grade 1, 102 (67.1%) were grade 2, 19 (12.5%) were grade 3, and 5 (3.3%) were grade 4.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological data of the patients.

3.2. Relationship between S100A9 expression and clinicopathological data

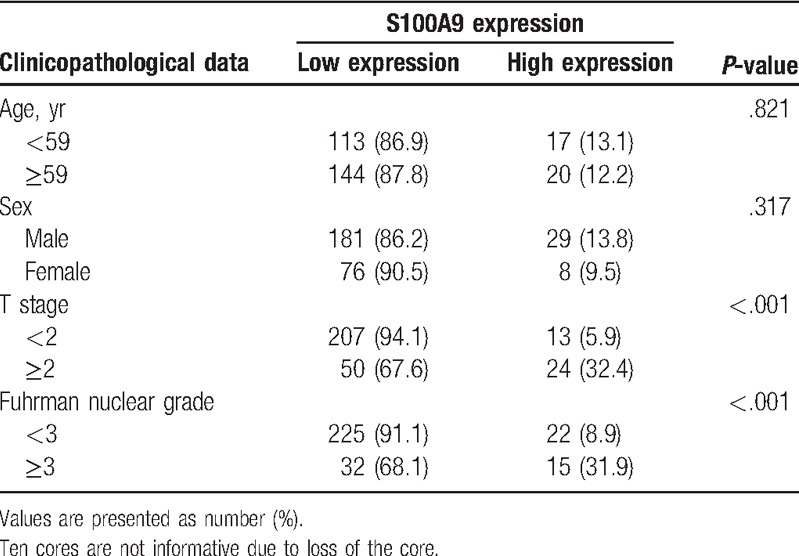

Among the cores, 37 (12.6%) revealed high expression for S100A9 and others revealed low expression. The relationships between S100A9 expression and clinicopathological data are shown in Table 2. S100A9 expression was significantly related with T stage (P < .001) and Fuhrman nuclear grade (P < .001), but not with patient age (P = .821) and sex (P = .317).

Table 2.

Relationship between S100A9 expression and clinicopathological data (n = 294 cores).

3.3. S100A9 expression and survival analysis

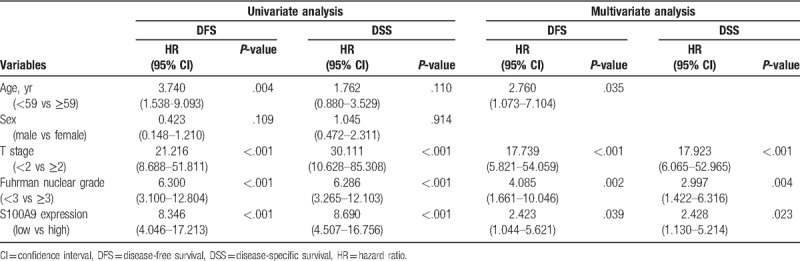

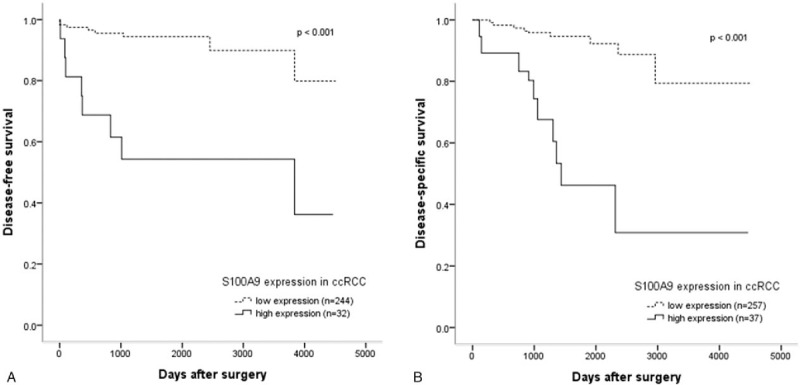

Among all the enrolled patients, the median DSS time was 1466.5 days, and the median DFS time was 1334.0 days. In the univariate analysis, several variables were associated with DFS, including patient age (P = .004), T stage (P < .001), Fuhrman nuclear grade (P < .001) and S100A9 expression (P < .001), with DSS, including T stage (P < .001), Fuhrman nuclear grade (P < .001) and S100A9 expression (P < .001). Moreover, multivariate analysis revealed that high S100A9 expression was an independent factor for unfavorable DFS (hazard ratio, 2.423; 95% confidence interval, 1.044–5.621; P = .039) and DSS (hazard ratio, 2.428; 95% confidence interval, 1.130–5.214; P = .023) in patients with ccRCC (Table 3). Furthermore, in the Kaplan–Meier analysis with the log-rank test, the high S100A9 expression group showed significantly lower survival than the low expression group for DFS (P < .001) and DSS (P < .001) (Fig. 2A and B).

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazards regression test of disease-free and disease-specific survival for patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis based on S100A9 expression in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. High S100A9 expression group shows significantly lower disease-free survival (A) and disease-specific survival (B) than the low expression group.

4. Discussion

There is increasing evidence that cancer metastasis is preceded by the formation of a supportive microenvironment in the target organ, termed the pre-metastatic niche, which indicates molecular and cellular changes that make the metastatic site suitable for tumor metastasis.[6,13–15] Many molecular and cellular elements have been found to be involved in pre-metastatic niche formation, secreted by tumor cells and/or myeloid cells and stromal cells.[15]

S100A9 is a tumor- and stromal cell-derived niche-promoting-molecule demonstrated in lung carcinoma and melanoma.[15–18] Recent studies have shown that high S100A9 expression in tumor cells was associated with tumor progression and poor prognosis.[7,14] Arai et al[7] reported that S100A9 overexpression was related to poor parameters including poor tumor differentiation, vascular invasion, node metastasis, and poor pathologic stage in breast ductal carcinoma. Huang et al[19] advocated that positive S100A9 expression might be a potential marker for poor prognosis because its expression rate in poorly differentiated tumor was higher than that in moderately and well-differentiated tumor in non-small cell lung cancer.

In the present study, we showed that high S100A9 expression significantly correlated with T stage and Fuhrman nuclear grade in ccRCC. Moreover, we demonstrated that high S100A9 expression is related to unfavorable DFS and DSS in patients with ccRCC. To our knowledge, these findings are the first to reveal an association between high S100A9 expression and prognosis in patients with ccRCC.[20]

Based on our results, we may assume that S100A9 promotes tumor cell proliferation and progression through the activation of various molecular pathways in ccRCC. However, the present study did not include a functional test of S100A9 at the genetic and cellular level of ccRCC, and we recommend that future studies should explore the exact mechanism underlying the role of S100A9 in ccRCC.[19]

Our study has some limitations. It might have been subject to sampling bias due to its retrospective nature and could induce a lack of representativeness due to the small number of tissue microarray cores per case. Therefore, larger prospective studies are needed, with the inclusion of sufficient tumor tissues.

In summary, S100A9 was highly expressed in 37 cores (12.6%) of ccRCC, which was related with higher T stage (≥2) and Fuhrman nuclear grade (≥3). High S100A9 expression was also associated with unfavorable DFS and DSS in patients with ccRCC. Consequently, S100A9 expression could be considered as a significant prognostic marker in patients with ccRCC.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Hyun Min Koh, Dae Hyun Song.

Data curation: Hyun Min Koh, Hyo Jung An.

Formal analysis: Hyun Min Koh.

Investigation: Hyun Min Koh, Hyo Jung An, Dae Hyun Song.

Resources: Hyun Min Koh, Hyo Jung An, Gyung Hyuck Ko, Jeong Hee Lee, Jong Sil Lee, Dong Chul Kim, Dae Hyun Song.

Supervision: Gyung Hyuck Ko, Jeong Hee Lee, Jong Sil Lee, Dong Chul Kim, Dae Hyun Song.

Validation: Hyo Jung An, Gyung Hyuck Ko, Jeong Hee Lee, Jong Sil Lee, Dong Chul Kim, Dae Hyun Song.

Writing – original draft: Hyun Min Koh.

Hyun Min Koh orcid: 0000-0002-7457-7174.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ccRCC = clear cell renal cell carcinoma, DFS = disease-free survival, DSS = disease-specific survival, RCC = renal cell carcinoma.

How to cite this article: Koh HM, An HJ, Ko GH, Lee JH, Lee JS, Kim DC, Song DH. Prognostic role of S100A9 expression in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Medicine. 2019;98:40(e17188).

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Rasti A, Mehrazma M, Madjd Z, et al. Co-expression of cancer stem cell markers OCT4 and NANOG predicts poor prognosis in renal cell carcinomas. Sci Rep 2018;8:11739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kumar A, Kumari N, Gupta V, et al. Renal cell carcinoma: molecular aspects. Indian J Clin Biochem 2018;33:246–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Goebell PJ, Staehler M, Müller L, et al. Changes in treatment reality and survival of patients with advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma – analyses from the german clinical RCC-registry. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2018;16:e1101–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zhou L, Pan X, Li Z, et al. Oncogenic miR-663a is associated with cellular function and poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma. Biomed Pharmacother 2018;105:1155–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gebhardt C, Németh J, Angel P, et al. S100A8 and S100A9 in inflammation and cancer. Biochem Pharmacol 2006;72:1622–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Salama I, Malone PS, Mihaimeed F, et al. A review of the S100 proteins in cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2008;34:357–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Arai K, Takano S, Teratani T, et al. S100A8 and S100A9 overexpression is associated with poor pathological parameters in invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2008;8:243–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Arai K, Teratani T, Nozawa R, et al. Immunohistochemical investigation of S100A9 expression in pulmonary adenocarcinoma: S100A9 expression is associated with tumor differentiation. Oncol Rep 2001;8:591–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Su YJ, Xu F, Yu JP, et al. Up-regulation of the expression of S100A8 and S100A9 in lung adenocarcinoma and its correlation with inflammation and other clinical features. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123:2215–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Srikrishna G. S100A8 and S100A9: new insights into their roles in malignancy. J Innate Immun 2012;4:31–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hiratsuka S, Watanabe A, Aburatani H, et al. Tumour-mediated upregulation of chemoattractants and recruitment of myeloid cells predetermines lung metastasis. Nat Cell Biol 2006;8:1369–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lim SY, Yuzhalin AE, Gordon-Weeks AN, et al. Tumor-infiltrating monocytes/macrophages promote tumor invasion and migration by upregulating S100A8 and S100A9 expression in cancer cells. Oncogene 2016;35:5735–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Weidle UH, Birzele F, Kollmorgen G, et al. The multiple roles of exosomes in metastasis. Cancer Genomics Proteomics 2017;14:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Eisenblaetter M, Flores-Borja F, Lee JJ, et al. Visualization of tumor-immune interaction-target-specific imaging of S100A8/A9 reveals pre-metastatic niche establishment. Theranostics 2017;7:2392–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Liu Y, Cao X. Characteristics and significance of the pre-metastatic niche. Cancer Cell 2016;30:668–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hiratsuka S, Watanabe A, Sakurai Y, et al. The S100A8–serum amyloid A3–TLR4 paracrine cascade establishes a pre-metastatic phase. Nat Cell Biol 2008;10:1349–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tomita T, Sakurai Y, Ishibashi S, et al. Imbalance of clara cell-mediated homeostatic inflammation is involved in lung metastasis. Oncogene 2011;30:3429–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Peinado H, Alečković M, Lavotshkin S, et al. Melanoma exosomes educate bone marrow progenitor cells toward a pro-metastatic phenotype through MET. Nat Med 2012;18:883–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Huang H, Huang Q, Tang T, et al. Clinical significance of calcium-binding protein S100A8 and S100A9 expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac Cancer 2018;9:800–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Song DH, Ko GH, Lee JH, et al. Prognostic role of myoferlin expression in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 2017;8:89033–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]