Abstract

There is interest in metal single atom catalysts due to their remarkable activity and stability. However, the synthesis of metal single atom catalysts remains somewhat ad hoc, with no universal strategy yet reported that allows their generic synthesis. Herein, we report a universal synthetic strategy that allows the synthesis of transition metal single atom catalysts containing Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, Ru, Pt or combinations thereof. Aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy and extended X-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy confirm that the transition metal atoms are uniformly dispersed over a carbon black support. The introduced synthetic method allows the production of carbon-supported metal single atom catalysts in large quantities (>1 kg scale) with high metal loadings. A Ni single atom catalyst exhibits outstanding activity for electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide to carbon monoxide, achieving a 98.9% Faradaic efficiency at −1.2 V.

Subject terms: Materials chemistry, Electrocatalysis, Nanoscale materials

Single-atom catalysts are a promising class of catalytic materials, but general synthetic methods are limited. Here, the authors develop a ligand-mediated strategy that allows the large-scale synthesis of diverse transition metal single atom catalysts supported on carbon.

Introduction

Homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts are widely used across chemical industry1–3. Homogeneous catalysts offer high efficiency and high selectivity due to their easily accessible active sites and maximal active metal utilization but suffer from low stability and poor recyclability. In contrast, heterogeneous catalysts offer excellent stability and good recyclability, but their active metal utilization is typically low (only surface atoms in supported metal nanoparticles actually participate in catalytic reactions)4,5. Single-atom catalysts (SACs) have recently emerged as a promising new class of catalytic materials, capturing the inherent advantages of both homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts. SACs typically comprise individual metal atoms (M) immobilized on a support, with many SACs being stabilized through porphyrin-like MN4 surface coordination geometries6. Accordingly, SACs have the dual advantage of nearly 100% atomic utilization (similar to homogeneous catalysts) as well as high stability and easy separation from reaction media (features of heterogeneous catalysts). Furthermore, when the size of active metal component is reduced from the nanometer lengths (i.e., nanoparticles or clusters) to the atomic level (i.e., SACs), new electronic states of the metal can appear thereby imparting unique performance7.

Following the pioneering discovery of SACs by Zhang et al.8, numerous experimental and theoretical studies have highlighted the outstanding catalytic potential of SACs for hydrogenation reactions9, carbon monoxide (CO) oxidation10, methane conversion11, carbon dioxide (CO2) reduction12–16, hydrogen evolution17, oxygen reduction18, dinitrogen (N2) reduction19, and other chemical transformations1. Various synthetic strategies have been used to access SACs, including physical and chemical methods. Physical methods, such as mass-selected soft landing20 and atomic layer deposition21, are not especially amenable for large-scale production of SACs since they require complex and expensive equipment. Chemical strategies involving the atomic dispersion of metals on a catalyst support, typically through the adsorption of metal precursors followed by reduction and stabilization, are therefore more practical22. Another common chemical approach toward SACs involves the carbonization of zeolitic imidazolate frameworks containing Co (ZIF-67) and Zn (ZIF-8)23,24. Although the feasibility of these two synthetic approaches has been confirmed in a number of studies25, the low yields and low metal loadings (~1 wt.%) of these approaches limit their practical usefulness. For many practical applications, SACs with high metal loadings are demanded. Further, existing chemical strategies are not very versatile and cannot easily be adapted to synthesize SACs containing other transition metals. Some recent studies have attempted to develop more universal synthetic methods toward SACs. Duan et al. used holey graphene as substrate to synthesize Fe, Co, and Ni-SACs26. Qu et al. reported that Cu, Co, or Ni-SACs could be fabricated on a carbon support containing abundant defect sites (derived by pyrolysis of ZIF-8) using a gas-migration method27. However, a single synthetic strategy that allows the large-scale synthesis of SACs containing almost any transition metal with high metal loadings has proven elusive. Such a synthetic strategy would expedite the utilization of SACs across the chemical sector. Recently, Beller and co-workers28 reported a novel protocol for preparing nanoscale cobalt-based catalysts via pyrolysis of organometallic amine complexes on activated carbon. The coordination of the metal cations by ligands during the pyrolysis step was found to reduce Co agglomeration leading to the formation of ultrafine supported Co nanoparticles. However, the high temperature (800 °C) used in that study was an obstacle to obtaining SACs. By lowering the pyrolysis temperature, SACs should be accessible since the kinetics and thermodynamic driving force for metal nanoparticle formation should be greatly reduced, motivating a detailed investigation.

Herein we report the successful synthesis of a library of M-SACs (M = Ni, Mn, Fe, Co, Cr, Cu, Zn, Ru, Pt, and combinations thereof) by complexing metal cations with 1,10-phenanthroline, adsorbing the resulting metal complexes onto commercial carbon black (Ketjenblack EC-300J), followed by pyrolysis of the resulting surface-modified carbons at 600 °C under an argon atmosphere (Fig. 1, see “Methods” section for full details). Aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectroscopy confirm that all M-SACs contain metals atomically dispersed in porphyrin-like MN4 sites over the carbon support (no cluster or nanoparticle formation is observed). X-ray absorption near edge spectroscopy (XANES) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) reveal that all M-SACs contained M2+ ions. Further, compositional analysis by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) establish that the synthesis method could produce M-SACs with high metal loadings (easily up to 1.8 wt.% for all metals, Supplementary Table 1). The performance of the different M-SACs are subsequently evaluated for electrochemical CO2 reduction, with the Ni-SAC containing 2.5 wt.% demonstrating outstanding performance for CO2 reduction to CO (~99% Faradaic efficiency at −1.2 V).

Fig. 1.

The universal synthesis procedure. Metal single-atom catalysts (M-SACs) are prepared in two steps

Results

Characterization of M-SACs

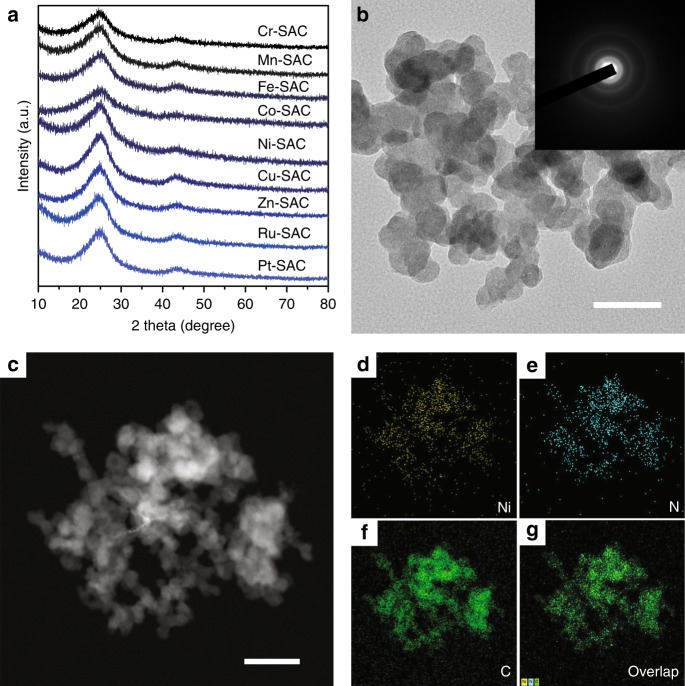

The structure of the M-SACs synthesized using the new “ligand-mediated” method (M = Ni, Mn, Fe, Co, Cr, Cu, Zn, Ru, Pt, and combinations thereof) were first probed by powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The XRD patterns of all M-SACs showed broad peaks centered around 24° and 44° (Fig. 2a), corresponding to the (002) and (100) planes of graphite. No metal-related peaks were observed in the XRD patterns. Conversely, pyrolysis of the Ni-SAC precursor at 800 °C resulted in the formation of some Ni clusters (Supplementary Fig. 1), in agreement with Beller’s results28. It can be concluded that the lower pyrolysis temperature of 600 °C used in the current work prevented metal nanocluster formation. TEM images for the M-SACs confirmed that no metal clusters or nanoparticles were present on the carbon black support (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Figs. 2–9). Energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) element maps (Fig. 2c–g) for Ni-SAC confirmed a very homogeneous dispersion of Ni and N over the carbon support. Selected-area electron diffraction (Fig. 2b, inset) showed that the Ni-SAC possessed low crystallinity and no Ni nanoparticles (evidenced by an absence of any intense rings), consistent with the XRD results. The Raman spectrum for Ni-SAC (Supplementary Fig. 10) contained two peaks at 1359 and 1595 cm−1, which can readily be assigned to disordered sp3 carbon (D band) and graphitic sp2 carbon (G band), respectively. The ID/IG ratio for Ni-SAC (0.87) was lower than that determined for pristine carbon black (1.01), indicating that the graphitic content of the carbon support increased after the pyrolysis step used to synthesize Ni-SAC.

Fig. 2.

Characterization of metal single-atom catalysts. a XRD patterns for different metal single-atom catalysts. b TEM image and SAED pattern (inner) for Ni-SAC-2.5, scale bar 100 nm. c STEM image for Ni-SAC-2.5, scale bar 100 nm. d–g EDX maps for Ni-SAC-2.5

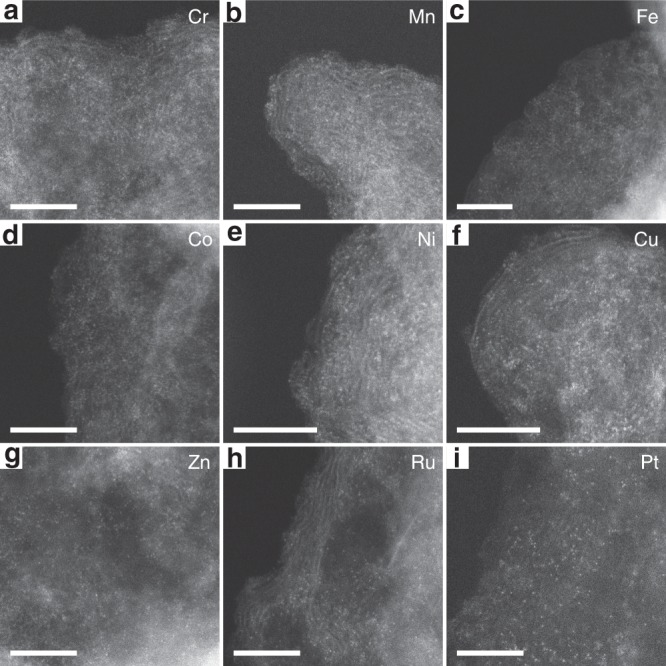

HAADF-STEM was used to definitively confirm the atomic dispersion of metal atoms over the carbon support in the different M-SACs. As shown in the HAADF-STEM images of the SACs (Fig. 3a–g), the first row of transition metals (Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn) appeared as high-density bright dots, indicating that these metals existed in the single-atom form on the carbon substrate. Similar results were found for the SACs containing the second-row (Ru) and third-row (Pt) transition metals (Fig. 3h, i, respectively), where Ru and Pt atoms were found to be homogeneously dispersed as single atoms on the carbon support. A further advantage of the synthetic strategy reported herein is that it allows the synthesis of multicomponent metal SACs, which are very difficult to obtain via conventional pyrolysis methods used to synthesize SACs. For example, bimetallic Fe/Co-SACs could be successfully synthesized. XRD (Supplementary Fig. 11) and HAADF-STEM (Supplementary Fig. 12) confirmed that Fe and Co atoms were atomically dispersed over the carbon support. Ru/Fe-SACs, Ru/Co-SACs, and Ru/Ni-SACs were also synthesized. XRD patterns for these catalysts (Supplementary Fig. 13) contained two broad peaks corresponding to the carbon black support and no other features. These studies highlight the universality of the new synthesis method for the preparation of M-SACs.

Fig. 3.

Images for various metal single-atom catalysts. Aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy for a Cr-SAC, b Mn-SAC, c Fe-SAC, d Co-SAC, e Ni-SAC, f Cu-SAC, g Zn-SAC, h Ru-SAC, and i Pt-SAC. Scale bar: 5 nm

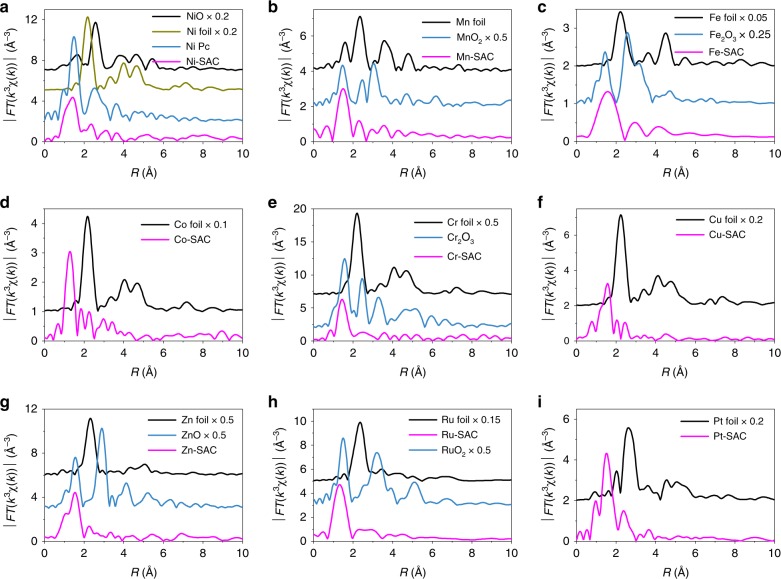

EXAFS spectroscopy is very sensitive to the local environment of metal atoms. Accordingly, EXAFS was applied to confirm the presence of single metal atom sites in the various M-SACs. Figure 4 shows metal K-edge EXAFS data (R space plots) for the SACs along with data for relevant reference samples. For each M-SAC, the R space plots were quite distinct from that of the corresponding metal or metal oxide reference. Ni-SAC showed an intense peak at approximately 1.45 Å, corresponding to the first Ni-N coordination shell, with the oscillation being very similar to that observed for nickel phthalocyanine (Ni Pc), indicating that Ni atoms in the Ni-SAC had a similar local environment with that of Ni atoms in Ni Pc. Fitting result determined that Ni in Ni-SAC was coordinated fourfold by N atoms, as is also found in Ni Pc (Supplementary Fig. 14). The other M-SACs also showed only a single peak in R space (at shorter lengths than the typical M–M distance in the corresponding metal foil), confirming that no metal–metal bonds existed in the M-SACs. These results were in good accord with the findings of the HAADF-STEM analyses. XANES spectra and k3-weighted K-space spectra for the different M-SACs are shown in Supplementary Figs. 15–32. For all nine M-SAC samples, the adsorption edge was higher than that of the corresponding metal foil, indicating that M-SACs contained metal atoms in cationic states (likely the M2+ state)29–31.

Fig. 4.

Metal K-edge extended X-ray absorption fine structure (R space plots). a Ni-SAC, b Mn-SAC, c Fe-SAC, d Co-SAC, e Cr-SAC, f Cu-SAC, g Zn-SAC, h Ru-SAC, and i Pt-SAC. In all the M-SACs, the metal atoms existed as isolated M2+ centers in a MN4 coordination environment

The chemical composition and elemental states of the M-SACs were investigated by XPS. The Ni 2p XPS spectrum for Ni-SAC (Supplementary Fig. 33a) showed a Ni 2p3/2 peak at 855.6 eV, higher than that observed for Ni0 and slightly lower than that for Ni2+ in NiO. The data provide strong evidence for the presence of Ni2+ in the Ni-SACs, with the slightly lower binding energy compared to NiO due to coordination by N rather than O. The C 1s spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 33b) was deconvoluted into two peaks, corresponding to C-C or C=C (neutral carbon and adventitious hydrocarbons) and C-N species. The N 1s spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 33c) for the Ni-SAC could be deconvoluted into three peaks, corresponding to pyridinic-N, pyrrolic-N, and graphitic-N. The presence of N, which originated from the 1,10-phenanthroline ligand, adds further weight to the proposal that the metal atoms in the M-SACs existed in MN4 coordination environments (as established from the EXAFS analyses). XPS data collected for the other M-SACs (Supplementary Figs. 34–41) were similar to that reported for the Ni-SAC, with the metal core-level spectra providing strong evidence for the presence of M2+ single-atom states.

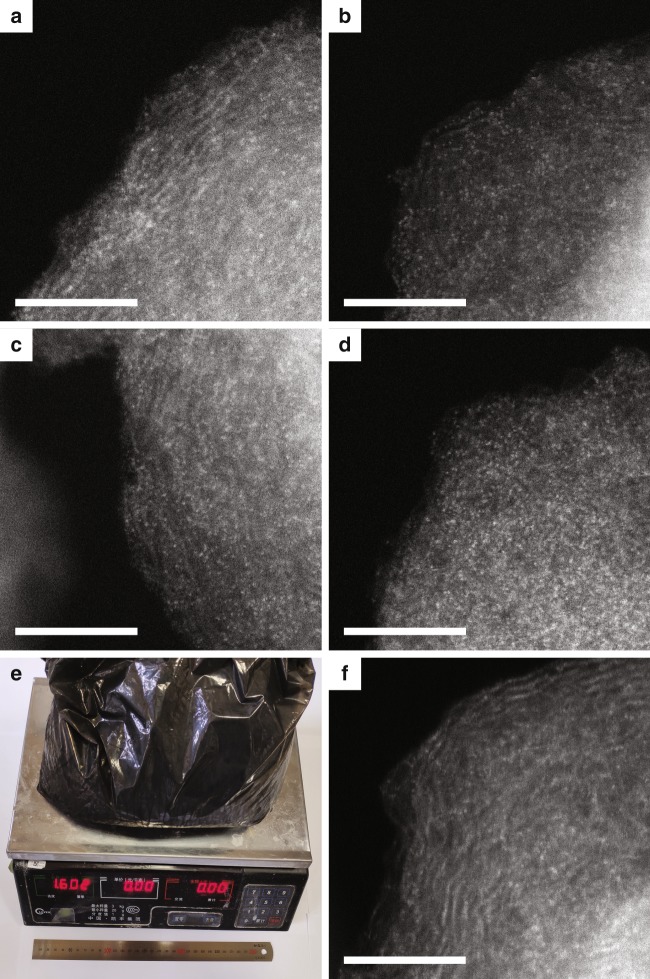

Synthesizing SACs with high metal loadings and in large quantities has traditionally proved technically challenging and remains an obstacle to the widespread utilization of SACs. In traditional synthesis methods, SACs are obtained by high-temperature pyrolysis of metal organic frameworks (MOFs) or metal-impregnated graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4). Such methods produce single-atom sites, though a large fraction of metal atoms in the precursor are typically transformed to metal clusters or nanoparticles. Here a low pyrolysis temperature of only 600 °C was used to synthesize the M-SACs, which was possible since we used a commercial carbon as the support (thus higher temperatures were not needed to obtain a partially graphitic and conductive carbon support as is the case with MOFs or g-C3N4 precursors). Accordingly, the method we developed was expected to be more amenable for the synthesis of M-SACs with high metal loadings. To test this hypothesis, we synthesized a series of Ni-SACs with different Ni loadings (denoted as Ni-SAC-x, where x is the actual Ni loading in wt.%), with the actual Ni loadings determined by ICP-OES. Using our new “ligand-mediated” synthetic strategy, Ni-SACs with Ni loadings of 2.5, 3.4, 4.5, and 5.3 wt.% were obtained, with the high loadings being superior to those of most other Ni-SACs reported to date (Supplementary Table 2). Supplementary Figs. 42–45 show TEM images for the Ni-SACs prepared at the different Ni loadings. For all Ni-SAC-x samples, no metal nanoparticles were observed. The XRD patterns for each sample contained broad peaks at 24° and 44° (Supplementary Fig. 46) corresponding to the (002) and (100) planes of graphite. To confirm that Ni was atomically dispersed at each loading, HAADF-STEM and EXAFS analyses were performed. Figure 5a–d show HAADF-STEM images for the Ni-SAC-x samples. For all samples, the atoms were atomically dispersed, with a few very small Ni clusters seen for the Ni-SAC-5.3 sample. Supplementary Figs. 47–49 show Ni K-edge EXAFS R space plots, Ni K-edge XANES, and Ni K-edge EXAFS K-space plots, respectively, for the Ni-SACs synthesized with different Ni loadings. The XANES data confirmed that all the Ni-SACs contained Ni2+. The R space plots showed a distinct feature at ~1.45 Å, corresponding to Ni-N first coordination shell. Results confirm that all of the Ni-SAC-x samples contained Ni2+ atoms fourfold coordinated by N. In addition, since our method was based on the modification of a commercially available carbon, it is suitable for scaling up. To prove this, we performed some large-scale syntheses, producing up to 1.6 kg of Ni-SAC in a single synthesis (Fig. 5e, with potential for further production scale-up). No metallic nickel peaks were seen in the XRD pattern of the large batch sample (Supplementary Fig. 50) or corresponding HAADF-STEM image (Fig. 5f), indicating that nickel was atomically dispersed over the carbon black.

Fig. 5.

Characterization and large-scale synthesis of Ni catalysts with different loadings. a HAADF-STEM image for Ni-SAC with 2.5 wt.% Ni loading. b HAADF-STEM image for Ni-SAC with 3.4 wt.% Ni loading. c HAADF-STEM image for Ni-SAC with 4.5 wt.% Ni loading. d HAADF-STEM image for Ni-SAC with 5.3 wt.% Ni loading. Scale bar: 5 nm. e Photograph for Ni-SAC-2.5 synthesized in large scale. f HAADF-STEM image for Ni-SAC-2.5 synthesized in large scale. Scale bar: 5 nm

Electroreduction of CO2 to CO

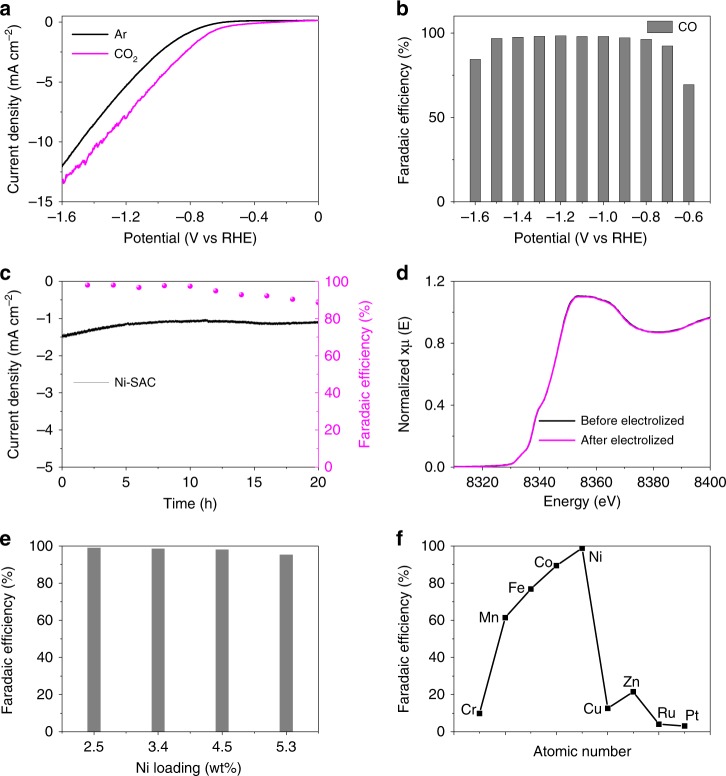

Phthalocyanines and porphyrins, in which metal ions are surrounded fourfold by N, are important families of enzyme-mimicking catalysts. Metal porphyrins linked by organic struts to form covalent organic frameworks are particularly active for the CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR), a key reaction for high-density renewable energy storage and CO2 capture32. Our characterization studies above revealed that the local environment of metal atoms in the M-SACs were very similar to that of the same metals in phthalocyanines and porphyrins. Further, here the SACs were dispersed on a carbon support with good electrical conductivity, which was expected to greatly enhance electrocatalytic performance. This motivated a detailed study of the performance of the various M-SACs synthesized in the current work for electrocatalytic CO2RR. The electrocatalytic CO2RR activities of the different M-SACs were measured in a sealed H-type cell, with gas chromatography used for product detection. Figure 6a shows the linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curves for Ni-SAC in Ar and CO2 saturated electrolytes. The current density was much higher in the CO2-saturated electrolyte, indicating that Ni-SAC was more active for CO2 reduction than hydrogen evolution. Figure 6b shows the Faradaic efficiency to CO (FECO) for Ni-SAC at different potentials. Ni-SAC displayed excellent CO2RR performance, maintaining a high FECO (above 90%) over a wide range of potentials (from −0.7 to −1.5 V vs reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE)) and a low Faradaic efficiency to H2 (Supplementary Fig. 51), with the highest FECO (98.9%) achieved at −1.2 V. No liquid products were detected in the aqueous phase by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 52), confirming a very high selectivity to CO. The FECO was higher than most state-of-the-art catalysts (Supplementary Table 2). We also tested the performance of Ni-SAC for the CO2RR at a fixed potential (−0.8 V vs RHE). As shown in Fig. 6c, only a very slight decrease in the current density occurred over 20 h. Figure 6d shows Ni K-edge XANES spectra for the Ni-SAC before and after CO2RR tests. The before and after spectra were almost identical, confirming that the Ni-SAC was very stable under the conditions of CO2RR.

Fig. 6.

CO2 electrochemical reduction performance of metal single-atom catalysts. a Cathodic LSV scans for Ni-SAC-2.5 in Ar-saturated and CO2-saturated aqueous 0.1 M KHCO3 solutions. b FECO for Ni-SAC-2.5 at different potentials in a CO2-saturated aqueous 0.1 M KHCO3 solution. c Stability test for Ni-SAC-2.5 at −0.8 V vs RHE. d XANES spectra for Ni-SAC-2.5 before and after CO2RR tests. e FECO for Ni-SAC-x at −1.2 V vs RHE. f FECO for M-SACs at −1.2 V vs RHE

The performance of the Ni-SACs with different Ni loadings, Ni-SAC synthesized in large scale (1.6 kg), and M-SACs with different metals were also evaluated for CO2RR. The FECO for the Ni-SACs with Ni loadings of 2.5, 3.4, 4.5, and 5.3 wt.% at −1.2 V were 98.9%, 98.5%, 98.0%, and 95.3%, respectively (Fig. 6e). The FECO of the Ni-SAC-5.3 sample was a bit smaller than values determined for the other samples with lower Ni loadings, which may have been due to the co-existence of Ni-SACs and tiny Ni clusters in this sample. To demonstrate the scalability of the “ligand-mediated” method, we also test the CO2RR performance of the Ni-SAC synthesized in large scale (~1.6 kg). The catalytic properties of the large batch sample were almost identical to those of samples synthesized on a 70-mg scale (Supplementary Fig. 53), confirming the scalability of the new synthetic method. Furthermore, thanks to the universality of the “ligand-mediated” method, it was possible to quantitatively compare the effect of central metal atom in M-SACs on CO2RR performance. The CO2RR performance of the M-SACs, each with similar metal loadings, were tested at −1.2 V vs RHE (Fig. 6f). Interestingly, the FECO of the M-SACs plotted against metal atomic number followed a volcano curve, with the Ni-SAC displaying the highest activity for CO2RR. On transitioning from Cr to Ni, the FECO increased, whereas on going from Ni to Zn the FECO decreased abruptly. The observation of a “volcano curve” likely originates from the d-band center position of each metal in the M-SACs, with the d-band center position of Ni2+ in the Ni-SACs being most ideal for CO2RR33,34.

Discussion

As mentioned above, a wide range of M-SACs (M = Ni, Mn, Fe, Co, Cr, Cu, Zn, Ru, Pt, and combinations thereof) were successfully prepared using a single “ligand-mediated” synthetic strategy. In this strategy, metal complexes (i.e., M2+ ions coordinated by 1,10-phenanthroline ligands) facilitate the creation of “porphyrin-like” single metal atom sites on the carbon black surface, thereby tightly binding the metal cations and preventing the aggregation of the metal atoms into clusters or nanoparticles. Further, the direct use of a conductive carbon support circumvents the need to use high pyrolysis temperatures that are obviously detrimental to SACs’ stability (typically temperatures as high as 900 °C are needed to produce carbon materials with good conductivities if derived from ZIF precursors). HAADF-STEM and EXAFS analysis indicated that the metal atoms were atomically dispersed (as M2+) in all the M-SACs. The developed synthetic method thus confers the following advantages over existing methods for SAC fabrication: (1) it is universal and can be applied to synthesize various transition metal SACs and even bimetallic SACs; (2) commercially available, conductive carbons can be used as a support, which is advantageous for electrocatalytic applications; (3) the method allows large-scale SAC production (kilogram scale, with potential for further production scale-up); and (4) the method yields SACs with high metal loadings. Therefore, this work represents a totally new paradigm for the synthesis of SACs.

In summary, we have developed a universal and robust “ligand-mediated” method for the synthesis of M-SACs with high metal contents. The method can be used to synthesize M-SACs containing first-, second- and third-row transition metals on carbon supports. Ni-SACs synthesized by the new method show excellent activity and stability for electrochemical CO2 reduction to CO (FECO of 98.9% at −1.2 V at the optimum Ni loading of 2.5 wt.%). As well as M-SACs containing single metals (Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Cu, Zn, Ru, Pt), the synthetic method could also be used to synthesize bimetallic SACs. Results pave the way for the large-scale fabrication of M-SACs with high metal loadings for CO2 reduction, oxygen reduction or evolution, hydrogen evolution, N2 reduction, and other chemical reactions.

Methods

Chemicals

Nickel (II) acetate tetrahydrate and manganese (II) acetate tetrahydrate were purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Iron (II) acetate was purchased from J&K Scientific., Ltd. Cobalt (II) acetate tetrahydrate was purchased from Guangdong GHTECH Co., Ltd. Chromium (III) nitrate nonahydrate and copper (II) acetate monohydrate were purchased from Xilong Scientific Co., Ltd. Ruthenium (III) chloride was purchased from Innochem Co., Ltd. Platinum (II) chloride was purchased from Acros Organic Co., Ltd. 1,10-Phenanthroline monohydrate was purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Zinc (II) acetate dihydrate, ethanol, and dimethyl sulfoxide were purchased from Beijing Chemical Works. All reagents and solvents were of analytical grade and used as received without additional purification. The CO2 and Ar feed gases were purchased from Beijing SIDADE RM Science and Technology Co., Ltd.

Synthesis of Ni-SAC-x (where x is the wt.% Ni)

For the synthesis of Ni-SAC-2.5% (i.e., a Ni SAC containing 2.5 wt.% Ni), nickel (II) acetate tetrahydrate (12.4 mg) and 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate (29.7 mg) were dissolved in 2 mL of ethanol followed by stirring for approximately 20 min at room temperature. Subsequently, carbon black (69.6 mg) was added into the solution, and the resulting solution was heated in an oil-bath at 60 °C for 4 h under continuous magnetic stirring. The resulting dispersion was then heated at 80 °C in air for 12 h to evaporate the ethanol, yielding a black solid. The black solid obtained was lightly ground with a mortar and pestle, then transferred into a ceramic crucible and placed in a tube furnace. The black solid was then heated to 600 °C at a rate of 10 °C min−1 under an argon atmosphere and then held at 600 °C for 2 h. The product obtained after cooling to room temperature was denoted as Ni-SAC-2.5%. The Ni-SAC-3.4%, Ni-SAC-4.5%, and Ni-SAC-5.3% samples were obtained using a similar procedure, except that the amount of nickel (II) acetate tetrahydrate used was increased to 18.7, 24.9, and 49.7 mg, respectively, and the amount of 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate used was increased proportionally to 44.6, 59.5, and 118.9 mg, respectively, to maintain a 1,10-phenanthroline:Ni molar ratio of 3.

Synthesis of Mn-SAC, Fe-SAC, Co-SAC, and Zn-SAC

The Mn-SAC, Fe-SAC, Co-SAC, and Zn-SAC samples were prepared using a similar procedure to that described above for Ni-SAC-2.5, except that the amount of 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate and metal salt were adjusted as required to achieve a 1,10-phenanthroline:M molar ratio of 3. The amounts of metal salt and 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate used in each synthesis were: manganese (II) acetate tetrahydrate (19.8 mg) and 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate (101.9 mg); iron (II) acetate (13.8 mg) and 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate (100.3 mg); cobalt (II) acetate tetrahydrate (18.8 mg) and 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate (94.99 mg); and zinc (II) acetate dihydrate (14.9 mg) and 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate (85.6 mg).

Synthesis of Cr-SAC, Cu-SAC, Ru-SAC, and Pt-SAC

Cr-SAC, Cu-SAC, Ru-SAC, and Pt-SAC were prepared using a similar procedure to that described for Ni-SAC-2.5, except that dimethyl sulfoxide rather than ethanol was used as the solvent. The amounts of metal salt and 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate used in each synthesis were: chromium (III) nitrate nonahydrate (34.2 mg) and 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate (107.7 mg); copper (II) acetate monohydrate (13.9 mg) and 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate (88.1 mg); ruthenium (III) chloride (9.1 mg) and 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate (55.4 mg); and platinum (II) chloride (6.1 mg) and 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate (28.7 mg). Owing to the higher boiling point of dimethyl sulfoxide, the solvent evaporation step (that preceded sample heating in the tube furnace) was performed at 190 °C instead of 80 °C.

Synthesis of bimetallic SACs

Fe/Co-SAC was prepared using a similar procedure to that described for Ni-SAC-2.5, except that the amount of metal salt was adjusted to iron (II) acetate (13.8 mg) and cobalt (II) acetate tetrahydrate (18.8 mg), and the amount of 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate was adjusted to 195.29 mg. Ru/Fe-SAC, Ru/Co-SAC, and Ru/Ni-SAC were prepared using a similar procedure to that described for Ni-SAC-2.5, except that the dimethyl sulfoxide rather than ethanol was used as the solvent. The amounts of metal salt and 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate used in each synthesis were: ruthenium (III) chloride (9.1 mg), iron (II) acetate (13.8 mg), and 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate (155.7 mg); ruthenium (III) chloride (9.1 mg), cobalt (II) acetate tetrahydrate (18.8 mg), and 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate (150.39 mg); and ruthenium (III) chloride (9.1 mg), nickel (II) acetate tetrahydrate (12.4 mg), and 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate (85.1 mg).

Synthesis of Ni-SAC on a large scale

For the synthesis of Ni-SAC on a large scale, nickel (II) acetate tetrahydrate (165.0 g) and 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate (920.7 g) were dissolved in 2.5 L of ethanol followed by stirring at room temperature. Subsequently, carbon black (924.0 g) was added into the solution, and the resulting solution was then heated at 60 °C for 4 h under continuous stirring. The resulting dispersion was then heated at 80 °C in air for 12 h to evaporate ethanol, yielding a black solid that was ground to a powder. The black powder was then heated to 600 °C at a rate of 10 °C min−1 under an argon atmosphere, and then held at 600 °C for 2 h. The product was obtained after cooling to room temperature.

Catalyst characterization

TEM images were collected on a HITACHI HT-7700 (HITACHI, Japan) microscope operating at an accelerating voltage of 100 kV. HAADF-STEM images and EDX elemental maps were obtained on an ARM-200CF (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) operating at 200 kV and equipped with double spherical aberration correctors. The resolution of the probe defined by the objective pre-field was 78 pm. XRD patterns were obtained on a Bruker D8 Focus X-ray diffractometer equipped with Cu Kα radiation source (λ = 1.5405 Å) operating at 40 kV. XPS data were collected on a VGESCALABMKII X-ray photoelectron spectrometer using a non-monochromatized Al-Kα X-ray source (hν = 1486.6 eV). XAFS data were obtained at the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (1W1B). Raman spectra were collected on a Renishaw inVia-Reflex spectrometer system and excited by a 532-nm laser. The metal loadings in the SACs were measured by ICP-OES (Varian 710).

Electrochemical measurements

A three-electrode sealed H-type cell was used in all electrochemical tests. Catalysts (4 mg) were dispersed in a solution of H2O (0.5 mL), ethanol (0.48 mL), and 5 wt.% Nafion solution (0.02 mL). After sonication for 2 h, a uniform ink-like dispersion was obtained. Next, 2 μL of the dispersion was dropped onto a polished glassy carbon electrode (GCE), and the resulting electrode was allowed to dry in air for several hours. This catalyst/GCE served as the working electrode in subsequent electrochemical tests. An Ag/AgCl electrode and a Pt wire were used as the reference electrode and the counter electrode, respectively. LSV data were collected at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1 in a 0.1 M KHCO3 electrolyte. When testing the Faradaic efficiency, the working electrode was held at a constant potential for 30 min. The gas products evolved were detected by a Shimadzu GC-2014 chromatograph (Shimadzu Co., Japan) equipped with a HP PLOT Al2O3 column and a flame ionization detector.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for financial support from the National Key Projects for Fundamental Research and Development of China (2018YFB1502002, 2017YFA0206904, 2017YFA0206900, 2016YFB0600901), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51825205, 51772305, 51572270, U1662118, 21871279, 21802154), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (2191002, 2182078, 2194089), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB17000000), the Royal Society-Newton Advanced Fellowship (NA170422), the International Partnership Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (GJHZ1819, GJHZ201974), the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Project (Z181100005118007), the K. C. Wong Education Foundation, and the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of the CAS. The XAFS experiments were conducted in 1W1B beamline of Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF). G.I.N.W. acknowledges funding support from Greg and Kathryn Trounson (via a generous philanthropic donation), the Energy Education Trust of New Zealand, and the MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology.

Author contributions

T.Z. and L.S. conceived the idea and designed the experiments. T.Z. supervised the project. H.Y. and L.S. carried out the experiments and characterizations. Q.Z. and L.G. helped to carry out the spherical aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM characterizations. H.Y., L.S., G.I.N.W. and T.Z. wrote the manuscript. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the corresponding author on request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks anonymous reviewers for their contributions to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Hongzhou Yang, Lu Shang.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-12510-0.

References

- 1.Wang A, Li J, Zhang T. Heterogeneous single-atom catalysis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2018;2:65–81. doi: 10.1038/s41570-018-0010-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu C, Fu S, Shi Q, Du D, Lin Y. Single-atom electrocatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:13944–13960. doi: 10.1002/anie.201703864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Y, et al. Single-atom catalysts: synthetic strategies and electrochemical applications. Joule. 2018;2:1242–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.joule.2018.06.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao D, et al. Size-dependent electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 over Pd nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:4288–4291. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang X, et al. Freestanding palladium nanosheets with plasmonic and catalytic properties. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011;6:28–32. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen F, Jiang X, Zhang L, Lang R, Qiao B. Single-atom catalysis: bridging the homo- and heterogeneous catalysis. Chin. J. Catal. 2018;39:893–898. doi: 10.1016/S1872-2067(18)63047-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu L, Corma A. Metal catalysts for heterogeneous catalysis: from single atoms to nanoclusters and nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:4981–5079. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qiao B, et al. Single-atom catalysis of CO oxidation using Pt1/FeOx. Nat. Chem. 2011;3:634–641. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei S, et al. Direct observation of noble metal nanoparticles transforming to thermally stable single atoms. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018;13:856–861. doi: 10.1038/s41565-018-0197-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wan J, et al. Defect effects on TiO2 nanosheets: stabilizing single atomic site Au and promoting catalytic properties. Adv. Mater. 2018;30:1705369. doi: 10.1002/adma.201705369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie P., et al. Nanoceria-supported single-atom platinum catalysts for direct methane conversion. ACS Catal. 2018;8:4044–4048. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b00004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao C, et al. Ionic exchange of metal-organic frameworks to access single nickel sites for efficient electroreduction of CO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:8078–8081. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b02736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X, et al. Exclusive Ni-N4 sites realize near-unity CO selectivity for electrochemical CO2 reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:14889–14892. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b09074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang HB, et al. Atomically dispersed Ni(i) as the active site for electrochemical CO2 reduction. Nat. Energy. 2018;3:140–147. doi: 10.1038/s41560-017-0078-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang K, et al. Isolated Ni single atoms in graphene nanosheets for high-performance CO2 reduction. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018;11:893–903. doi: 10.1039/C7EE03245E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao G, Jiao Y, Waclawik ER, Du A. Single atom (Pd/Pt) supported on graphitic carbon nitride as an efficient photocatalyst for visible-light reduction of carbon dioxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:6292–6297. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b02692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen W, et al. Rational design of single molybdenum atoms anchored on N-doped carbon for effective hydrogen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:16086–16090. doi: 10.1002/anie.201710599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yin P, et al. Single cobalt atoms with precise N-coordination as superior oxygen reduction reaction catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:10800–10805. doi: 10.1002/anie.201604802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geng Z, et al. Achieving a record-high yield rate of 120.9 ug NH3 mgcat.-1 h-1 for N2 electrochemical reduction over Ru single-atom catalysts. Adv. Mater. 2018;30:1803498. doi: 10.1002/adma.201803498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stefan V, White MG. Catalysis applications of size-selected cluster deposition. ACS Catal. 2015;5:7152–7176. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.5b01816. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun SH, et al. Single-atom catalysis using Pt/graphene achieved through atomic layer deposition. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1775. doi: 10.1038/srep01775. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu Y, et al. A cocoon silk chemistry strategy to ultrathin N-doped carbon nanosheet with metal single-site catalysts. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3861. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06296-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shang L, et al. Well-dispersed ZIF-derived Co,N-Co-doped carbon nanoframes through mesoporous-silica-protected calcination as efficient oxygen reduction electrocatalysts. Adv. Mater. 2016;28:1668–1674. doi: 10.1002/adma.201505045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Y, et al. Isolated single iron atoms anchored on N-doped porous carbon as an efficient electrocatalyst for the oxygen reduction reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:6937–6941. doi: 10.1002/anie.201702473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu W, et al. Single-atom dispersed Co-N-C catalyst: structure identification and performance for hydrogenative coupling of nitroarenes. Chem. Sci. 2016;7:5758–5764. doi: 10.1039/C6SC02105K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fei H, et al. General synthesis and definitive structural identification of MN4C4 single-atom catalysts with tunable electrocatalytic activities. Nat. Catal. 2018;1:63–72. doi: 10.1038/s41929-017-0008-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qu Y, et al. Direct transformation of bulk copper into copper single sites via emitting and trapping of atoms. Nat. Catal. 2018;1:781–786. doi: 10.1038/s41929-018-0146-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conghui T, et al. A stable nanocobalt catalyst with highly dispersed CoNx active sites for the selective dehydrogenation of formic acid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:16616–16620. doi: 10.1002/anie.201710766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Z, et al. Co-based catalysts derived from layered-double-hydroxide nanosheets for the photothermal production of light olefins. Adv. Mater. 2018;30:e1800527. doi: 10.1002/adma.201800527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deng Y, Handoko AD, Du Y, Xi S, Yeo BS. In situ raman spectroscopy of copper and copper oxide surfaces during electrochemical oxygen evolution reaction: identification of CuIII oxides as catalytically active species. ACS Catal. 2016;6:2473–2481. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.6b00205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sasaki K, Marinkovic N, Isaacs HS, Adzic RR. Synchrotron-based in situ characterization of carbon-supported platinum and platinum monolayer electrocatalysts. ACS Catal. 2015;6:69–76. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.5b01862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin S, et al. Covalent organic frameworks comprising cobalt porphyrins for catalytic CO2 reduction in water. Science. 2015;349:1208–1213. doi: 10.1126/science.aac8343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng Y, et al. Molecule-level g-C3N4 coordinated transition metals as a new class of electrocatalysts for oxygen electrode reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:3336–3339. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b13100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hammer B, Norskov JK. Theoretical surface science and catalysis-calculations and concepts. Adv. Catal. 2000;45:71–129. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are available from the corresponding author on request.