This nonrandomized clinical trial compares self-reported patient outcomes and burden of unwanted care among older adults with multiple chronic conditions who received either patient priorities–based care or usual care at a Connecticut primary care site.

Key Points

Question

Is care for older adults with multiple chronic conditions that is aligned with their health priorities associated with improved patient-reported outcomes and reduced unwanted care?

Findings

This nonrandomized clinical trial of 366 adults 65 years or older with multiple chronic conditions found that, although there was no difference in perception of whether their care was goal-directed or coordinated, participants receiving patient priorities care vs usual care reported a greater reduction in treatment burden, and their health records reflected more medications stopped and fewer self-management tasks and diagnostic tests added.

Meaning

This study’s findings suggest that aligning care with patients’ priorities may improve outcomes for patients with multiple chronic conditions.

Abstract

Importance

Health care may be burdensome and of uncertain benefit for older adults with multiple chronic conditions (MCCs). Aligning health care with an individual’s health priorities may improve outcomes and reduce burden.

Objective

To evaluate whether patient priorities care (PPC) is associated with a perception of more goal-directed and less burdensome care compared with usual care (UC).

Design, Setting, and Participants

Nonrandomized clinical trial with propensity adjustment conducted at 1 PPC and 1 UC site of a Connecticut multisite primary care practice that provides care to almost 15% of the state’s residents. Participants included 163 adults aged 65 years or older who had 3 or more chronic conditions cared for by 10 primary care practitioners (PCPs) trained in PPC and 203 similar patients who received UC from 7 PCPs not trained in PPC. Participant enrollment occurred between February 1, 2017, and March 31, 2018; follow-up extended for up to 9 months (ended September 30, 2018).

Interventions

Patient priorities care, an approach to decision-making that includes patients’ identifying their health priorities (ie, specific health outcome goals and health care preferences) and clinicians aligning their decision-making to achieve these health priorities.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcomes included change in patients’ Older Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (O-PACIC), CollaboRATE, and Treatment Burden Questionnaire (TBQ) scores; electronic health record documentation of decision-making based on patients’ health priorities; medications and self-management tasks added or stopped; and diagnostic tests, referrals, and procedures ordered or avoided.

Results

Of the 366 patients, 235 (64.2%) were female and 350 (95.6%) were white. Compared with the UC group, the PPC group was older (mean [SD] age, 74.7 [6.6] vs 77.6 [7.6] years) and had lower physical and mental health scores. At follow-up, PPC participants reported a 5-point greater decrease in TBQ score than those who received UC (ß [SE], –5.0 [2.04]; P = .01) using a weighted regression model with inverse probability of PCP assignment weights; no differences were seen in O-PACIC or CollaboRATE scores. Health priorities–based decisions were mentioned in clinical visit notes for 108 of 163 (66.3%) PPC vs 0 of 203 (0%) UC participants. Compared with UC patients, PPC patients were more likely to have medications stopped (weighted comparison, 52.0% vs 33.8%; adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 2.05; 95% CI, 1.43-2.95) and less likely to have self-management tasks (57.5% vs 62.1%; AOR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.41-0.84) and diagnostic tests (80.8% vs 86.4%; AOR, 0.22; 95% CI, 0.12-0.40) ordered.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study’s findings suggest that patient priorities care may be associated with reduced treatment burden and unwanted health care. Care aligned with patients’ priorities may be feasible and effective for older adults with MCCs.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03600389

Introduction

Older adults with multiple chronic conditions (MCCs) receive large amounts of health care,1 much of which is of uncertain benefit.2,3 The observed benefits and harms generated in clinical trials involving populations with few health conditions may not apply to persons with MCCs.4,5,6,7 Furthermore, benefits have primarily been defined by disease-specific outcomes or survival, which may not be what matters most for older adults with MCCs.8,9,10 Concomitantly, practitioners and the public are increasingly aware of treatment burden for persons with MCCs.2,11,12,13 These patients and their caregivers spend an average of 2 hours a day on health care–related activities.14 Consequently, appropriate health care for individuals with MCCs is uncertain, as are the outcomes that define its effectiveness.

The National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine) defines patient-centered care as care “respectful of, and responsive to, individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.”15(p 3) In other words, appropriate care is care aligned with the individual’s specific health outcome goals and health care preferences.16 This definition of appropriate care is particularly important for older adults with MCCs for whom evidence of treatment benefit is uncertain and outcome goals vary.2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 Although methods for ascertaining and acting on patients’ goals and preferences exist for persons with advanced illness,17,18,19,20 less is known for the large number of older adults with MCCs.

To fill this gap, we instituted a multistakeholder initiative to define an appropriate approach to health care decision-making for adults aged 65 years or older who had MCCs.21,22,23,24,25 With input from patients, caregivers, clinicians, health system leaders, payers, and health care design experts, we developed patient priorities care (PPC), which involves identifying, communicating, and providing care consistent with patients’ health priorities.21,22 Patients’ health priorities include the health outcome goals they most desire given the health care they are willing and able to receive (ie, health care preferences). Previous studies reported on the development of a values-based approach to helping older adults identify their health priorities23 and on the feasibility of incorporating PPC into clinical practice.24 Challenges faced in aligning decision-making with patients’ health priorities and strategies for addressing these challenges were identified through experience in the pilot PPC practice25 and through action steps developed for the American Geriatrics Society’s Guiding Principles for the Care of Older Adults With Multimorbidity.2,26

The first objective of this study was to evaluate the association between participation in PPC and patients’ perception of whether their care was more focused on their health goals and less burdensome compared with care before PPC and with the perceptions of patients who received usual care (UC). The second objective was to assess changes in ambulatory health care in patients receiving PPC and UC.

Methods

Design

The development, implementation, and feasibility phases of this nonrandomized clinical trial have been described previously.23,24,27,28 Participant enrollment occurred between February 1, 2017, and March 31, 2018. Participant follow-up ended September 30, 2018. The study was approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Board, and the complete trial protocol is available in Supplement 1. Oral informed consent was obtained from study participants.

Setting and Participants

Patient priorities care was implemented in a multisite primary care practice that provides care to almost 15% of Connecticut residents.29 Two comparable sites served as the PPC and UC site. Both sites participate in improvement and research projects, and more than 15% of their patients are Medicare beneficiaries. All clinicians at the sites were invited to participate as were their patients who met eligibility criteria. The selection and recruitment of the practice and participating clinicians have been described previously.24

Patient Priorities Care Clinicians and Patient Participants

The leadership of the practice chose 1 site to implement PPC. All 10 primary care clinicians (2 advanced practice nurses, 1 physician assistant, and 7 physicians) at the PPC site agreed to participate. Because a key PPC principle is alignment between primary and specialty care, the 5-member cardiology practice that provides cardiac care to the greatest number of PPC patients was selected as the specialty practice. All 5 cardiologists agreed to participate. Cardiology was chosen because it is the medical specialty that provides the greatest amount of care to older adults with MCCs. The primary care clinicians and cardiologists received modest stipends for participating in PPC. A clinical “champion” was identified from the primary care practice and the cardiology practice to support their colleagues and serve as a liaison between their practices and the PPC implementation team.

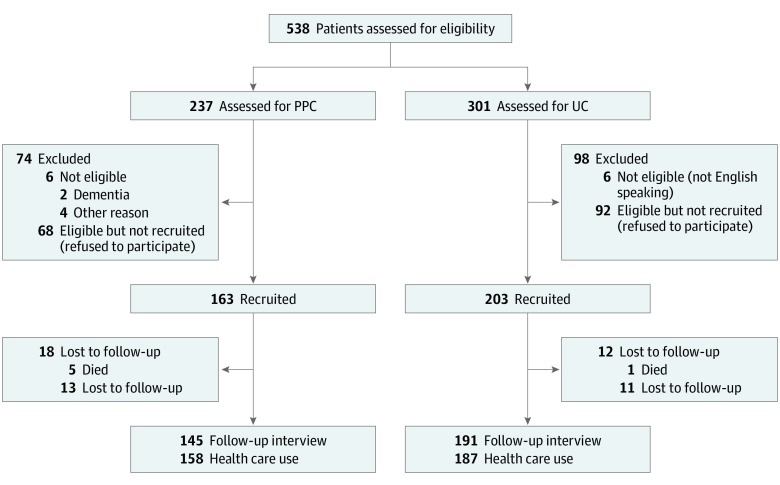

Potentially eligible patients cared for by the PPC site were identified by electronic health record (EHR) data. Criteria included more than 3 chronic conditions and either 10 medications or visits to more than 2 specialists in the past year. Exclusion criteria included hospice eligibility, receiving dialysis, advanced dementia, or nursing home residence. Clinicians reviewed lists of eligible patients the week before scheduled primary care practitioner (PCP) visits; the final decision about inviting patients was left to clinician discretion. The flow diagram of patient participants is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. STROBE Patient Flow Diagram.

Patients from both the patient priorities care (PPC) and usual care (UC) sites were prescreened using administrative data based on the eligibility criteria listed in the Methods section. Primary care clinicians at the PPC site decided which of the prescreened patients they would invite to participate. The UC site did not include the step of recruitment. Therefore, all potentially eligible participants were recruited from the UC site. Usual care clinicians did not review their prescreened patients; thus, all UC patients who met the administrative data screen were assumed to be eligible.

Usual Care Clinicians and Patient Participants

We performed 2 levels of matching to identify the UC practice. We first used commercial market segmentation data to identify census block groups with demographic and socioeconomic characteristics similar to the geographic catchment area of the PPC site.30 Second, among the 8 practice sites located in areas with demographic and socioeconomic characteristics similar to the PPC site, we selected the practice most similar to the PPC site in types of PCPs and percentage of the patient population who were Medicare beneficiaries. The 7 PCPs (2 advanced practice nurses, 2 physician assistants, and 3 physicians) at the UC site all agreed to participate. Their participation entailed sending a prepared letter to their eligible patients stating that they would be contacted about the study. All patients cared for by the UC clinicians who met the same eligibility criteria (without prereview by their clinicians) were invited to participate in the study.

Patient Priorities Care Intervention

The development and feasibility of implementing PPC has been described previously.21,22,24 The training and implementation of PPC was led by a multidisciplinary team of 4 geriatricians, 1 general internist expert in clinician training, 1 expert in behavioral medicine, and 2 project managers. The PPC approach is defined in detail elsewhere and summarized here.23,24

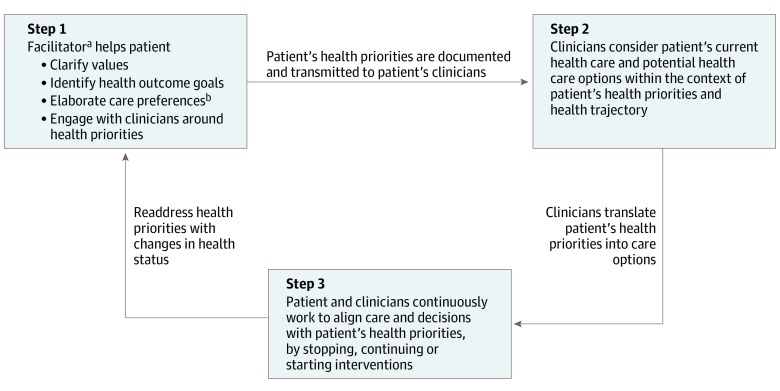

Patients were invited by their PCP to participate in PPC during routine visits. Those who accepted met in person or by telephone with an advanced practice nurse or a care manager employed by the primary care practice who served as facilitator (step 1 in Figure 2). The facilitators followed a clinically feasible process to help patients identify their values-based health priorities and interact with their clinicians concerning their health priorities.23 Facilitators completed 1-page health priorities templates that included brief summaries of function and support, key values, up to 3 health outcome goals, 3 helpful and doable and 3 unhelpful or difficult health care activities (health care preferences), and the one thing (eg, symptom, health condition) or health care activities (eg, medication, self-management task) on which they most wanted to focus to achieve their health outcome goals. Facilitator training included review of training materials, role playing, observation, and feedback.23 The patient priorities conversation guides for the facilitator and patients and a link to online PPC training are available elsewhere.31

Figure 2. Steps in Patient Priorities Care.

aMember of the health care team who helps patients identify their health priorities.

bHealth outcome goals are the health and life outcomes that patients desire from their health care. Health care preferences refers to the health care activities (eg, medications, self-management tasks, health care visits, testing, and procedures) that patients find helpful and doable or bothersome, unhelpful, or unwanted. Health priorities refers to the specific, actionable, and reliable health outcome goals that are consistent with their health care preferences.

Facilitators transmitted patients’ health priorities templates (eAppendix in Supplement 2) to the participating PPC clinicians (via a scanned EHR document to the PPC primary care clinicians and via fax to PPC cardiologists). Patient priorities care clinicians, who were reminded by office staff to review the templates the day of the first visit after patients identified their priorities, used this information in their communication and decision-making with patients and other clinicians (steps 2 and 3, Figure 2). Decisional strategies that support patient priorities–aligned decision-making and care were identified through emergent learning among the PPC implementation team and the participating clinicians.25 The recommended strategies included starting with a single thing that mattered most to the patient (Specific Ask in the Health Priorities template in the eAppendix of Supplement 2); conducting serial trials of starting, stopping, or continuing interventions; focusing on achieving the patient’s desired activities rather than completely eliminating symptoms, which is often not possible in persons with multiple conditions and symptoms; basing communications, decision-making, and measures of success or failure on patients’ priorities, not solely on diseases; and using collaborative negotiations when there are differences in perspectives between patient and clinician or among clinicians to arrive at agreed-upon decisions.25 An example of how these strategies may be used is provided in the eAppendix in Supplement 2. The clinical workflow, preparation of participating clinicians, and practice change framework used to encourage adoption of PPC has been reported.24,25

To estimate the time required to implement PPC, we worked with a process improvement staff member of the participating primary care practice to build workflows for the tasks needed to carry out PPC by staff and clinicians. We calculated the time spent on each task based on interviews with the relevant staff and clinicians. The tasks are included in eTable 1 in Supplement 2.

Primary Outcomes

Patient-Reported Outcomes

Patients’ perceptions as to whether their health care was collaborative and focused on their goals were measured by using the Older Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (O-PACIC) score (11 items; possible range, 1-5; Cronbach α = 0.87; higher score indicates better perceived experience of chronic disease care) and CollaboRATE (3 items; possible range, 0-100; Cronbach α = 0.89; higher score indicates greater perceived shared decision-making and goal ascertainment), and perceptions of burdensomeness were measured by the Treatment Burden Questionnaire (15 items; possible range, 0-150; Cronbach α = 0.90; higher score indicates greater perceived burden of treatment).11,32,33 These patient-reported outcomes were ascertained by telephone at baseline and after approximately 6 months’ follow-up.

Health Care Activities

Primary care clinicians’ notes were reviewed across 9 months of follow-up for documentation of decision-making based on patients’ health goals, health care preferences, or health priorities (disease-specific goals, such as blood pressure target, were not included). Also abstracted from visit notes were the number (percentage) of participants with medications and self-management tasks added or stopped plus diagnostic tests, referrals, or procedures ordered or avoided (defined as mentioned in the EHR that they were decided against because they were not considered by clinicians to be beneficial or they were unwanted by the patient). A data dictionary guided uniform abstraction. Uncertain decisions were adjudicated by the study’s primary investigators (M.E.T. and C.B.); 30% of EHRs were doubly abstracted.

All outcomes were ascertained by assessors blinded to patient group assignment. Outcome assessors were located separately from other members of the research and clinical teams, were unaware of specific aims and intervention details, and entered data on forms that did not include group assignment.

Descriptive and Covariate Data

Age, sex, race/ethnicity, educational level, marital status, and insurance coverage were ascertained during the baseline telephone interview or EHR review. During the baseline interview, physical and mental health were ascertained with PROMIS-10,34 and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment 5-word recall test35 was used to assess memory. Number and types of chronic conditions were determined from the problem list and medications from the medication list of the PCPs’ EHR.

Statistical Analysis

We compared baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for the PPC and UC participants using independent samples t tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. We estimated propensity score models with the PSMATCH procedure in a statistical software package (SAS, version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc) to achieve balance on baseline characteristics between the 2 groups using inverse probability of treatment weights.36,37 Balance was evaluated by comparing the distribution of the covariates using absolute standardized mean differences of 0.25 or less,38 variance ratios between 0.5 and 2.0,39 and side-by-side plots of the distribution of each covariate.37,40 Extreme weights were truncated at the 98th percentile value for 5 PPC and 2 UC participants.37 Missing baseline data were handled by using multiple imputation using the fully conditional specification method (M = 20) implemented by the multiple imputation procedure in SAS statistical software. Rubin formulas were used to combine model estimates into a single set of results using the MIANALYZE procedure in SAS.41

Change in patient-reported outcomes from baseline to follow-up was assessed by means of difference scores (ie, follow-up score minus baseline score) because the distribution of difference scores tends to be closer to normal (suitable for regression analysis) and offers a more intuitive interpretation than transformed variables.42 Health care activities were measured dichotomously. Both the patient-reported outcomes and health care activities models were adjusted for demographic and clinical characteristics in addition to propensity weights.43 The patient-reported outcome models also included length of follow-up. The health care models also included number of clinician visits. All analyses were intention to treat and performed using SAS statistical software; 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the 366 patients, 235 (64.2%) were female, 350 (95.6%) were white, and 7 (1.9%) were Hispanic. Compared with persons in the UC group, persons in the PPC group were older (mean [SD] age, 74.7 [6.6] vs 77.6 [7.6] years) and had lower physical and mental health scores (Table 1). As shown in Figure 1, 163 of 231 (70.6%) eligible patients at the PPC site agreed to participate, as did 203 of 295 (68.8%) at the UC site. Mean (SD) time between baseline interviews and the first PCP visit, which initiated PPC, was 11.2 (0.8) weeks in the PPC group and 7.7 (0.6) in the UC group. Characteristics of the 2 groups were similar after propensity score weighting. Follow-up O-PACIC, CollaboRATE, and Treatment Burden Questionnaire measurements were available for 145 (89.0%) of the PPC group and 191 (94.1%) of the UC group. Health care activities were available for 158 (96.9%) PPC and 187 (92.1%) UC participants (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics of participants who did and did not complete the follow-up are in eTable 2 in Supplement 2.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Participantsa.

| Characteristicb | No. (%) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPC (n = 163) | Usual Care (n = 203) | Unweightedc | Weightedd | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 77.6 (7.6) | 74.7 (6.6) | <.001 | .75 |

| Females | 109 (66.9) | 126 (62.1) | .31 | .99 |

| Race/ethnicitye | ||||

| White | 158 (96.9) | 192 (94.6) | .54 | .83 |

| Hispanic | 2 (1.2) | 5 (2.5) | .02 | .97 |

| Educational level | ||||

| <High school | 16 (9.8) | 11 (5.4) | <.001 | .92 |

| High school | 65 (39.9) | 90 (44.3) | ||

| Some college | 33 (20.3) | 52 (25.6) | ||

| College | 26 (16.0) | 48 (23.7) | ||

| Health insurance | ||||

| Traditional Medicare | 74 (45.4) | 98 (48.3) | .61 | .65 |

| Medicare Advantage | 65 (39.9) | 71 (35.0) | ||

| Medicare-Medicaid | 24 (14.7) | 34 (16.8) | ||

| 5-Word recall score, median (IQR) | 3.0 (2-4) | 3.0 (3-4) | .07 | .84 |

| PROMIS physical health score, median (IQR)f | 13.0 (11-16) | 15.0 (12-17) | <.001 | .83 |

| PROMIS mental health score, median (IQR)f | 13.0 (11-16) | 15.0 (12-18) | <.001 | .91 |

| Chronic conditions | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 4.00 (3-5) | 3.82 (3-5) | .14 | .93 |

| >5 | 37 (22.7) | 33 (16.3) | ||

| Hypertension | 127 (77.9) | 158 (77.8) | .98 | .20 |

| Diabetes | 48 (29.5) | 69 (34.0) | .34 | .91 |

| Heart failure | 12 (7.4) | 9 (4.4) | .23 | .81 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 33 (20.3) | 21 (10.3) | .008 | .85 |

| Arthritis | 77 (47.4) | 82 (40.4) | .19 | .83 |

| Chronic lung disease | 22 (13.5) | 33 (16.3) | .46 | .06 |

| Dementia | 3 (1.8) | 2 (1.0) | .48 | .97 |

| Chronic kidney diseases | 51 (31.3) | 79 (39.0) | .13 | .76 |

| Cancer other than skin | 5 (3.1) | 16 (7.9) | .049 | .81 |

| Depression | 41 (25.2) | 41 (20.2) | .26 | .79 |

| Osteoporosis | 27 (16.6) | 30 (14.8) | .64 | .66 |

| Stroke | 8 (4.9) | 9 (4.4) | .83 | .30 |

| Prescription medicationsg | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 7.0 (5-9) | 7.0 (4-9) | .74 | .40 |

| >10 | 20 (12.3) | 32 (15.8) | ||

| TBQ score | 24.7 (26.4) | 18.0 (21.7) | .01 | .19 |

| O-PACIC score | 2.8 (1.0) | 2.9 (1.0) | .48 | .53 |

| CollaboRATE score | 84.2 (19.3) | 83.5 (23.7) | .77 | .11 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; O-PACIC, Older Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care; PPC, patient priorities care; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; TBQ, Treatment Burden Questionnaire.

No. (%) unless otherwise stated.

Age, sex, health insurance, chronic conditions, and medications were ascertained from the electronic health record; educational level and PROMIS, 5-word recall, TBQ, O-PACIC, and CollaboRATE scores were assessed at the baseline interview. Twenty PPC participants started PPC before a baseline interview could be scheduled; these participants are therefore missing educational level and PROMIS, 5-word recall, TBQ, O-PACIC, and CollaboRATE results. Missing data were handled using the fully conditional specification method.

Unweighted P values were calculated using independent samples t tests for normally distributed continuous variables, Wilcoxon–Mann-Whitney tests for nonnormal continuous variables, and χ2 tests for categorical variables between groups.

Weighted P values were calculated using weighted generalized linear regression models by group with a normal distribution for continuous variables, a binary distribution for dichotomous variables, and a multinomial distribution for nominal categorical variables.

Race was defined as African American or white, and ethnicity was defined as Hispanic or white.

PROMIS 10 physical health scale (sample range, 1-20) and PROMIS 10 mental health scale (sample range, 4-20); Treatment Burden Questionnaire (score range, 0-150; higher score indicates greater perceived burden of treatment); O-PACIC (score range, 1-5; higher score indicates better perceived experience of chronic disease care); and CollaboRATE (score range, 0-100; higher score indicates greater perceived shared decision-making and goal ascertainment).

Prescription medications for chronic conditions were included.

Perceptions of Patient Goal-Centeredness and Burden of Health Care

Documentation by the PCPs or cardiologists of discussion or decision-making concerning patient’s health priorities were noted in 108 of 163 (66.3%) of the PPC participants vs none of the UC participants. Changes in patients’ perceptions of their care are given in Table 2. Participants in the PPC group reported a 5-point greater decrease in treatment burden score (β [SE], –5.0 [2.04]; P = .01) from baseline to follow-up than UC participants. Changes in O-PACIC and CollaboRATE scores were similar between the 2 groups.

Table 2. Baseline Follow-up Differences in Patient-Reported Outcomes Among Older Adults With MCCs Receiving PPC or UC.

| Patient-Reported Outcome | Least Squares Mean (SE)a | Baseline − Follow-upb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Priorities Care | Usual Care | Difference (SE) | P Value | |

| Treatment Burden Questionnaire | −12.4 (4.0) | −7.4 (4.0) | −5.0 (2.0) | .01 |

| O-PACIC | −0.2 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.2) | −0.06 (0.1) | .60 |

| CollaboRATE | −1.2 (5.3) | 2.9 (5.2) | −4.1 (2.8) | .14 |

Abbreviations: MCCs, multiple chronic conditions; O-PACIC, Older Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care; PPC, patient priorities care; SE, standard error; UC, usual care.

Treatment Burden Questionnaire (score range, 0-150; higher score indicates greater perceived burden of treatment); O-PACIC (score range, 1-5; higher score indicates better perceived experience of chronic disease care); and CollaboRATE (score range, 0-100; higher score indicates greater perceived shared decision-making and goal ascertainment).

Parameter estimates from the propensity score–weighted, doubly robust linear regression analysis for the patient-reported outcome difference scores were adjusted for sex, age, race, educational level, marital status, living situation, insurance type, physical and mental health functioning, cognitive functioning, chronic conditions, number of medications, and duration of follow-up.

Ambulatory Health Care Activities

The number of PCP visits (weighted mean [SE]) was similar across 9 months of follow-up for PPC (4.1 [0.2]) and usual care (3.6 [0.2]) participants. Compared with UC participants, PPC participants were more likely to have any medications stopped (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 2.05; 95% CI, 1.43-2.95), including cardiovascular medications (AOR, 3.43; 95% CI, 2.10-5.60) (Table 3). As noted in Table 3, PPC participants had moderately greater odds of having psychotropic medications both added and stopped; only the former reached statistical significance. Patient priorities care participants had lower odds of having diagnostic tests ordered (AOR, 0.22; 95% CI, 0.12-0.40) and self-management tasks added (AOR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.41-0.84) than UC participants.

Table 3. Changes in Ambulatory Health Care Use in Older Adults With MCCs Receiving PPC or UC.

| Health Care Use Category | Bivariate Analysis | Multivariable Analysis, Odds Ratio (95% CI)c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted %a | Odds Ratio (95% CI)b | |||

| PPC (n = 163) | Usual Care (n = 203) | |||

| Weighted No. | 357 | 362 | ||

| Medications | ||||

| Any medication | ||||

| Added | 65.0 | 58.9 | 1.15 (0.83-1.58) | 0.93 (0.63-1.39) |

| Stopped | 52.0 | 33.8 | 2.00 (1.47-2.72) | 2.05 (1.43-2.95) |

| Cardiovascular medicationd | ||||

| Added | 20.8 | 15.7 | 1.33 (0.90-1.96) | 1.07 (0.69-1.67) |

| Stopped | 25.9 | 8.9 | 3.42 (2.20-5.30) | 3.43 (2.10-5.60) |

| Psychotropic medicatione | ||||

| Added | 18.7 | 11.2 | 1.73 (1.13-2.65) | 1.67 (1.02-2.72) |

| Stopped | 11.0 | 7.0 | 1.57 (0.92-2.65) | 1.66 (0.92-3.01) |

| Diagnostic/laboratory testsf | ||||

| Any ordered | 80.8 | 86.4 | 0.33 (0.20-0.57) | 0.22 (0.12-0.40) |

| Any avoidedg | 5.0 | 3.6 | 1.37 (0.66-2.86) | 1.33 (0.62-2.85) |

| Referrals/consultsh | ||||

| Any ordered | 48.9 | 44.4 | 1.09 (0.81-1.49) | 1.02 (0.72-1.43) |

| Any avoidedg | 5.5 | 2.6 | 2.08 (0.94-4.62) | 1.87 (0.80-4.36) |

| Proceduresi | ||||

| Any scheduled | 29.2 | 21.5 | 1.41 (1.00-2.00) | 1.37 (0.95-1.98) |

| Any avoidedg | 12.3 | 7.1 | 1.75 (1.04-2.93) | 1.49 (0.86-2.57) |

| Self-management tasksj | ||||

| Any added | 57.5 | 62.1 | 0.71 (0.52-0.97) | 0.59 (0.41-0.84) |

| Any stopped | 6.4 | 8.6 | 0.69 (0.39-1.22) | 0.58 (0.31-1.11) |

Abbreviations: MCCs, multiple chronic conditions; PPC, patient priorities care; UC, usual care.

The numbers and percentages are weighted using inverse probability of treatment weights estimated with a propensity score model that included sex, age, race/ethnicity, educational level, marital status, living situation, insurance type, physical and mental health functioning, cognitive functioning, and chronic conditions.

Odds ratios and 95% CIs are from propensity score–weighted bivariate logistic regression analysis.

Adjusted odds ratios and 95% CIs are from propensity score–weighted, doubly robust logistic regression analysis adjusted for sex, age, race/ethnicity, educational level, marital status, living situation, insurance type, physical and mental health functioning, cognitive functioning, chronic conditions, number of medications, and duration of follow-up and are based on review of primary care clinicians’ visit notes and documentation.

Cardiac medications included antiarrhythmics, antihypertensives, diuretics, and statins.

Psychoactive medications included antidepressants, antipsychotics, and sedative-hypnotics.

Any blood tests or noninvasive (eg, electrocardiogram, imaging, or pulmonary function) tests performed in the ambulatory setting for reasons other than therapeutic.

Diagnostic tests, referrals, and procedures were considered to be avoided if there was mention in the electronic health record note that they were considered but decided against because they were not felt by clinicians to be indicated or beneficial or if they were against patient preference (ie, unwanted by the patient).

Referrals or consults involving medical or surgical specialties, rehabilitation (physical, occupational, or speech therapy; pulmonary or cardiac rehabilitation), or counseling.

Procedures included invasive procedures or surgeries performed in the ambulatory setting for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes. Examples included colonoscopies, catheterizations, eye procedures, and outpatient surgeries.

Examples of self-management tasks included restricted diets; checking weight, blood pressure, or glucose level; and exercise regimens.

Time Required for PPC

The time required for training in and implementing PPC, as estimated by the facilitators, is outlined in eTable 1 in Supplement 2. The typical time for the health care team member to identify patients’ priorities was estimated at approximately 20 to 30 minutes; the scheduling, reviewing EHRs, and documenting required an additional 15 to 40 minutes. Time commitment required of health information technology staff (1.0-1.5 days total) and office staff (approximately 10 minutes per patient across the 15 months) was modest.

Clinician training, including initial face-to-face sessions plus twice-monthly, 20-minute case-based discussions, required 8 hours across 15 months. Incorporating PPC into workflow required 30 to 33 minutes for PCPs, distributed across the invitation visit and 2 post–priorities identification visits, after which no additional time was required. Cardiologists required training and implementation time similar to that for the PCPs.

Discussion

Patient priorities care was associated with a much greater frequency of clinicians documenting decisions based on the patient’s health priories, goals, or preferences compared with UC. Electronic health records also showed that more PPC than UC patients had medications and self-management tasks stopped, but fewer PPC patients had diagnostic tests ordered. Patients receiving PPC reported a modestly greater reduction in treatment burden than those receiving UC. The high baseline CollaboRATE and O-PACIC scores, which left little room for improvement, at least partially explain the lack of difference in change in these measures between groups. The latter finding is consistent with reports that older age may be associated with greater patient satisfaction.33,44,45,46 Results of this study suggest that PPC may offer a decisional framework for focusing care on patients’ health goals, lessening their burden of health care, and avoiding potentially unwanted care.

Approaches focused on achieving patients’ goals, preferences, and priorities have been investigated for specific conditions and patients with advanced illness.17,18,19,20,47,48,49,50,51,52,53 Some approaches included facilitators who helped patients identify their preferences and priorities; results have been mixed.17,18,19,20,47,48,49,50,51,52,53 Trials addressing older adults with MCCs have not focused on patients’ health priorities. A systematic review of 18 systems- or patient-based interventions revealed limited effect on patient-reported health outcomes or health care use.54 A recent multidimensional intervention was effective at improving patients’ experience of patient-centered care but not health-related quality of life or treatment burden.55

Staff and clinician time to implement PPC was modest. The time required for priorities identification was lowest if performed immediately after patients were invited by their PCP, likely because it avoided time spent contacting the patient and scheduling a visit. This study’s findings suggest that patient priorities identification could be incorporated into the clinical workflow of team members such as medical assistants, social workers, nurses, case managers, or primary care practitioners. After training, clinicians’ time spent on PPC was minimal, suggesting a change in approach rather than inclusion of additional tasks.

Limitations and Strengths

The study has limitations. First, the sites were not randomized. Although we chose a UC site based on characteristics similar to the PPC site and used propensity adjustment, there may be remaining confounders that could explain outcome differences observed. The greater number of deaths as shown in Figure 1 (5 vs 1) likely reflects the fact that the PPC group was slightly older and sicker than the UC group. This pilot involved a single practice with a relatively homogeneous patient population. We cannot comment on how feasible or effective PPC would be in other settings and with other populations. Our results can only be considered suggestive; results require replication in larger, more diverse populations, preferably in a randomized trial. We could not blind the clinicians to group assignment, although the outcome assessors were blinded. Primary care practitioners and cardiologists were the only clinicians involved. Assuming that the outcomes would have shown greater differences between the patient care groups had all clinicians been prepared and agreed to align their care with patients’ health priorities, our results may underestimate the changes associated with PPC. Although we required EHR documentation that the health care activities stopped or avoided were stopped or avoided based on patient or clinician preference, we cannot be sure that they were all “unwanted,” nor can we be sure that the EHR documentation captured all of the changes in health care activities at the PPC or UC sites.

We lacked the claims data necessary to calculate costs or revenues from increases or decreases in health care activities. We also could not estimate the potential revenue generation through use of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services billing codes, such as advance care planning and care coordination, because these were not used by the practice. The financial effects of changes in utilization because of PPC depends on the payment model of the practice or health system.

Despite these limitations, there are important implications for the care of older adults with MCCs. Patient priorities care proved feasible and acceptable to patients and clinicians. It was incorporated into workflow with modest start-up time. If shown effective in settings with more heterogeneous populations, PPC could inform treatment deintensification or deprescribing by tailoring these decisions to each patient’s health priorities.56 Although helpful in guiding treatments that can be weaned, finding that some health care activities increased in the PPC vs the UC site suggests that patient priorities–aligned decision-making can also identify interventions likely to help patients achieve their outcome goals, offering the potential to address both overuse and underuse.57 Patient priorities care offers a platform for shared decision-making for persons with MCCs for whom disease-by-disease decisions can be cumbersome, conflicting, and potentially harmful. This approach works for patients who prefer either an active or passive role in decision-making.58 Even persons who do not desire active participation in treatment selection may articulate the values and outcomes they prioritize. Adherence may improve when recommendations align with patients’ goals, preferences, and capabilities.59 Finally, normalizing the identification of and alignment of decisions with patients’ health priorities may make decision-making in advanced illness less difficult.

Conclusions

Patient priorities care is expanding, with implementation in additional practices and health systems and with development of tools that facilitate adoption. The goal is to disseminate an approach to decision-making and care that maximizes benefits that matter to individuals with MCCs while minimizing harm and burden. Patient priorities care operationalizes the core patient-centered tenet that care should be driven by patient’s values, goals, and preferences.15 Patient priorities–aligned care may promote true value-based care.60

Trial Protocol

eAppendix. Patient Priorities Care: Health Priorities Template

eTable 1. Tasks and Times Associated With Patient Priorities Care

eTable 2. Baseline Comparisons of Participants who Completed Follow-up Interview and Participants Lost to Follow-up by Group

References

- 1.Chevarley FM. Expenditures by Number of Treated Chronic Conditions, Race/Ethnicity, and Age, 2012. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality; 2015. Statistical Brief No. 485. https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st485/stat485.pdf. Accessed February 21, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity Guiding Principles for the Care of Older Adults With Multimorbidity: an approach for clinicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(10):E1-E25. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04188.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uhlig K, Leff B, Kent D, et al. A framework for crafting clinical practice guidelines that are relevant to the care and management of people with multimorbidity. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(4):670-679. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2659-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zulman DM, Sussman JB, Chen X, Cigolle CT, Blaum CS, Hayward RA. Examining the evidence: a systematic review of the inclusion and analysis of older adults in randomized controlled trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(7):783-790. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1629-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berry SD, Ngo L, Samelson EJ, Kiel DP. Competing risk of death: an important consideration in studies of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):783-787. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02767.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitzgerald SP, Bean NG. An analysis of the interactions between individual comorbidities and their treatments—implications for guidelines and polypharmacy. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2010;11(7):475-484. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Hare AM, Hotchkiss JR, Kurella Tamura M, et al. Interpreting treatment effects from clinical trials in the context of real-world risk information: end-stage renal disease prevention in older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(3):391-397. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fried TR, Tinetti ME, Iannone L, O’Leary JR, Towle V, Van Ness PH. Health outcome prioritization as a tool for decision making among older persons with multiple chronic conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(20):1854-1856. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montori VM, Brito JP, Murad MH. The optimal practice of evidence-based medicine: incorporating patient preferences in practice guidelines. JAMA. 2013;310(23):2503-2504. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bayliss EA, Bonds DE, Boyd CM, et al. Understanding the context of health for persons with multiple chronic conditions: moving from what is the matter to what matters. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(3):260-269. doi: 10.1370/afm.1643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tran VT, Harrington M, Montori VM, Barnes C, Wicks P, Ravaud P. Adaptation and validation of the Treatment Burden Questionnaire (TBQ) in English using an internet platform. BMC Med. 2014;12:109. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyd CM, Wolff JL, Giovannetti E, et al. Healthcare task difficulty among older adults with multimorbidity. Med Care. 2014;52(suppl 3):S118-S125. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a977da [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiss JW, Boyd CM. Managing complexity in older patients with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(4):559-561. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02340317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jowsey T, Yen L, Matthews P. Time spent on health related activities associated with chronic illness: a scoping literature review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1044. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Institute of Medicine (IOM) Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001:3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naik AD. On the road to patient centeredness. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(3):218-219. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Childers JW, Back AL, Tulsky JA, Arnold RM. REMAP: a framework for goals of care conversations. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(10):e844-e850. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.018796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Austin CA, Mohottige D, Sudore RL, Smith AK, Hanson LC. Tools to promote shared decision making in serious Illness: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1213-1221. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sudore RL, Knight SJ, McMahan RD, et al. A novel website to prepare diverse older adults for decision making and advance care planning: a pilot study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(4):674-686. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernacki RE, Block SD; American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force . Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1994-2003. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tinetti ME, Esterson J, Ferris R, Posner P, Blaum CS. Patient priority–directed decision making and care for older adults with multiple chronic conditions. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32(2):261-275. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2016.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferris R, Blaum C, Kiwak E, et al. Perspectives of patients, clinicians, and health system leaders on changes needed to improve the health care and outcomes of older adults with multiple chronic conditions. J Aging Health. 2018;30(5):778-799. doi: 10.1177/0898264317691166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naik AD, Dindo LN, Van Liew JR, et al. Development of a clinically feasible process for identifying individual health priorities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(10):1872-1879. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blaum CS, Rosen J, Naik AD, et al. Feasibility of implementing patient priorities care for older adults with multiple chronic conditions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(10):2009-2016. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tinetti M, Dindo L, Smith CD, et al. Challenges and strategies in patients’ health priorities-aligned decision-making for older adults with multiple chronic conditions. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0218249. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boyd C, Smith CD, Masoudi F, et al. Decision making for older adults with multiple chronic conditions: executive summary of action steps for the AGS Guiding Principles on the Care of Older Adults With Multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):665-673. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012;50(3):217-226. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Handley MA, Lyles CR, McCulloch C, Cattamanchi A. Selecting and improving quasi-experimental designs in effectiveness and implementation research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:5-25. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-014128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casalino LP, Chen MA, Staub CT, et al. Large independent primary care medical groups. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(1):16-25. doi: 10.1370/afm.1890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI) Tapestry segmentation. https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/tapestry-segmentation/overview. Accessed October 8, 2016.

- 31.Patient Priorities Care website home page. https://patientprioritiescare.org/. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- 32.Cramm JM, Nieboer AP. Development and validation of the Older Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (O-PACIC) scale after hospitalization. Soc Indic Res. 2014;116(3):959-969. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0314-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forcino RC, Barr PJ, O’Malley AJ, et al. Using CollaboRATE, a brief patient-reported measure of shared decision making: results from three clinical settings in the United States. Health Expect. 2018;21(1):82-89. doi: 10.1111/hex.12588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, Spritzer KL, Cella D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(7):873-880. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70(1):41-55. doi: 10.1093/biomet/70.1.41 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med. 2015;34(28):3661-3679. doi: 10.1002/sim.6607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubin DB. Using propensity scores to help design observational studies: application to the tobacco litigation. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol. 2001;(3-4):169-188. doi: 10.1023/A:1020363010465 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stuart EA. Matching methods for causal inference: a review and a look forward. Stat Sci. 2010;25(1):1-21. doi: 10.1214/09-STS313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399-424. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 1987. doi: 10.1002/9780470316696 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rogosa DR, Brandt D, Zimowski M. A growth curve approach to the measurement of change. Psychol Bull. 1982;92(3):726-748. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.92.3.726 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rubin DB, Thomas N. Combining propensity score matching with additional adjustments for prognostic covariates. J Am Stat Assoc. 2000;95(450):573-585. doi: 10.1080/01621459.2000.10474233 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hartgerink JM, Cramm JM, Bakker TJ, Mackenbach JP, Nieboer AP. The importance of older patients’ experiences with care delivery for their quality of life after hospitalization. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):311. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0982-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deininger KM, Hirsch JD, Graveline A, et al. Relationship between patient-perceived treatment burden and health-related quality of life in heart transplant recipients [abstract]. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018;37(4)(special issue)(suppl):S351. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2018.01.899 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O’Malley AJ, Zaslavsky AM, Elliott MN, Zaborski L, Cleary PD. Case-mix adjustment of the CAHPS Hospital Survey. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6, pt 2):2162-2181. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00470.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Szanton SL, Alfonso YN, Leff B, et al. Medicaid cost savings of a preventive home visit program for disabled older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(3):614-620. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Naik AD, Martin LA, Moye J, Karel MJ. Health values and treatment goals of older, multimorbid adults facing life-threatening illness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(3):625-631. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Naik AD, Palmer N, Petersen NJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness of goal setting in diabetes mellitus group clinics: randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(5):453-459. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coulter A, Entwistle VA, Eccles A, Ryan S, Shepperd S, Perera R. Personalised care planning for adults with chronic or long-term health conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(3):CD010523. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010523.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rockwood K, Stadnyk K, Carver D, et al. A clinimetric evaluation of specialized geriatric care for rural dwelling, frail older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(9):1080-1085. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04783.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Toto PE, Skidmore ER, Terhorst L, Rosen J, Weiner DK. Goal attainment scaling (GAS) in geriatric primary care: a feasibility study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;60(1):16-21. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2014.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.MacKenzie MA, Smith-Howell E, Bomba PA, Meghani SH. Respecting choices and related models of advance care planning: a systematic review of published evidence. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(6):897-907. doi: 10.1177/1049909117745789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith SM, Wallace E, O’Dowd T, Fortin M. Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD006560. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006560.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salisbury C, Man M-S, Bower P, et al. Management of multimorbidity using a patient-centred care model: a pragmatic cluster-randomised trial of the 3D approach. Lancet. 2018;392(10141):41-50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31308-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827-834. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Green AR, Tung M, Segal JB. Older adults’ perceptions of the causes and consequences of healthcare overuse: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(6):892-897. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4264-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chi WC, Wolff J, Greer R, Dy S. Multimorbidity and decision-making preferences among older adults. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(6):546-551. doi: 10.1370/afm.2106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Naik AD, McCullough LB. Health intuitions inform patient-centered care. Am J Bioeth. 2014;14(6):1-3. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2014.915650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tinetti ME, Naik AD, Dodson JA. Moving from disease-centered to patient goals–directed care for patients with multiple chronic conditions: patient value-based care. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(1):9-10. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2015.0248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eAppendix. Patient Priorities Care: Health Priorities Template

eTable 1. Tasks and Times Associated With Patient Priorities Care

eTable 2. Baseline Comparisons of Participants who Completed Follow-up Interview and Participants Lost to Follow-up by Group