Abstract

Background

Depressive symptoms are a pervasive mental health problem in Chinese adolescents. The aim of this article was to systematically assess the trend of depressive symptoms in China among adolescents (1988 to 2018).

Material/Methods

A systematic and comprehensive literature search was conducted in both English and Chinese databases, including PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane CENTRAL, CNKI, and Wan Fang Database, to identify relevant studies published between 1988 and 2018. Batteries of analyses in this meta-analysis were undertaken using Stata version 12.0 statistical software.

Results

Sixty-two related reports involving 232 586 participants finally met our inclusion and exclusion criteria. The results suggest the prevalence of depressive symptoms has generally increased over time. The prevalence estimates before 2000 were 18.4% (95% CI, 14.5–22.3%), and were 26.3% (95% CI, 21.9–30.8%) after 2016. The pooled prevalence of depressive symptoms among children and adolescents was 22.2% (95% CI: 19.9–24.6%, I2=99.6%, p<0.001). More subgroup analyses classified by screening instrument, gender, and region were carried out in this meta-analysis.

Conclusions

Results of our meta-analysis suggest that depressive symptoms have become more prevalent among Chinese adolescents. This trend emphasizes the need for effective prevention strategies and greater availability of screening tools for this vulnerable population.

MeSH Keywords: Adolescent Psychology, China, Depression, Meta-Analysis

Background

Depression, a common and chronic disorder, is characterized by specific symptoms, with an estimated prevalence of around 4–5% in middle to late adolescence [1–3]. According to the World Health Organization, depression is projected to become the leading cause of global disease by 2030 [4,5]. Almost a quarter of all adults will experience depression beginning in adolescence [6]. Depression in adolescents can have devastating outcomes, including poor educational attainment, impaired social relationships, insomnia, smoking, substance misuse, and obesity [7–10]. More than half of suicide victims in adolescents had depressive disorder, making depression the most common cause of suicide [11]. As depression is a national public health problem, it is urgent to prevent its onset and recurrence in this vulnerable population by recognizing and treating this disorder [12,13].

Many studies have associated mental health with region, race, cultural setting, and socioeconomic status [14,15]. Owing to different cultures and beliefs, Canadian teenagers have lower prevalence of depressive symptoms than their counterparts in China [16]. During the past 2 decades, China has had sharp economic growth and entered into a dramatic transition of economy and society. Therefore, Chinese people must accordingly change their lifestyles and accelerate their pace of life to adapt to the transition. As a result, numerous risk factors appeared and increased in daily life, such as enormous emotional pressure and weakening of social support [17,18].

Although many studies have evaluated depressive symptoms among teenagers in China, the results widely varied across studies, ranging from 4.41% [19] to 55.7% [20]. This inconsistency is probably caused by differences in sample sizes and screening tools with diverse cutoffs [21]. For instance, the prevalence of depressive symptoms assessed using CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression) as a screening instrument with different cutoffs varies from 5.6% [22] to 54.4% [23]. In consideration of these inconsistencies and in light of the many negative outcomes of depression, it is imperative to estimate the prevalence of depressive symptoms to design effective preventive strategies aimed at this vulnerable age group.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis summarized the prevalence of depressive symptom in China, but included only middle school students [24]. While some studies reported that the prevalence estimates of depression start to grow in early adolescence, we also included children in this analysis. The association between the reported prevalence of depressive symptoms and the year of study publication was also explored in this meta-analysis, and we also analyzed the trend of depressive symptoms among children and adolescents in China in the last 30 years.

Material and Methods

Our study was conducted following the framework of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [25]. The quality assessment instrument for epidemiological studies was applied when assessing the quality of studies [26–28]. All analyses were based on previously published studies; therefore, ethics approval and patient consent were not required.

Search strategies

We conducted a comprehensive literature search to identify published research on the prevalence of depressive symptom among children and adolescents in China. The 5 major electronic databases – the CNKI database (China National Knowledge Infrastructure), the Wan Fang database, Cochrane CENTRAL, PubMed, and EMBASE – were searched to find all eligible articles. Medical subject headings [MeSH] and keywords combined with Boolean operators were used in the search strategy to look for relevant studies published between 1988 and 2018, and the following MeSH terms were used: “child*”, “teenager*”, “adolescent*”, “student*”, “depressive symptoms*”, “depression*”, “prevalence*”, “rate*”. The bibliographies and citations of relevant articles and review studies were also screened for other potential articles.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All the eligible studies in this meta-analysis were subjected to the following inclusion criteria: (1) cross-sectional study of depressive symptom about child and adolescence aged less than 18 years old; (2) depressive symptom as the major outcome of eligible articles was clearly identified by self-report scales that previous studies have demonstrated with validated psychometric properties; (3) prevalence statistics on depressive symptoms can be calculated in accordance with the relevant article; (4) the full-text article could be retrieved through different computerized databases; and (5) sample size greater than 200 individuals.

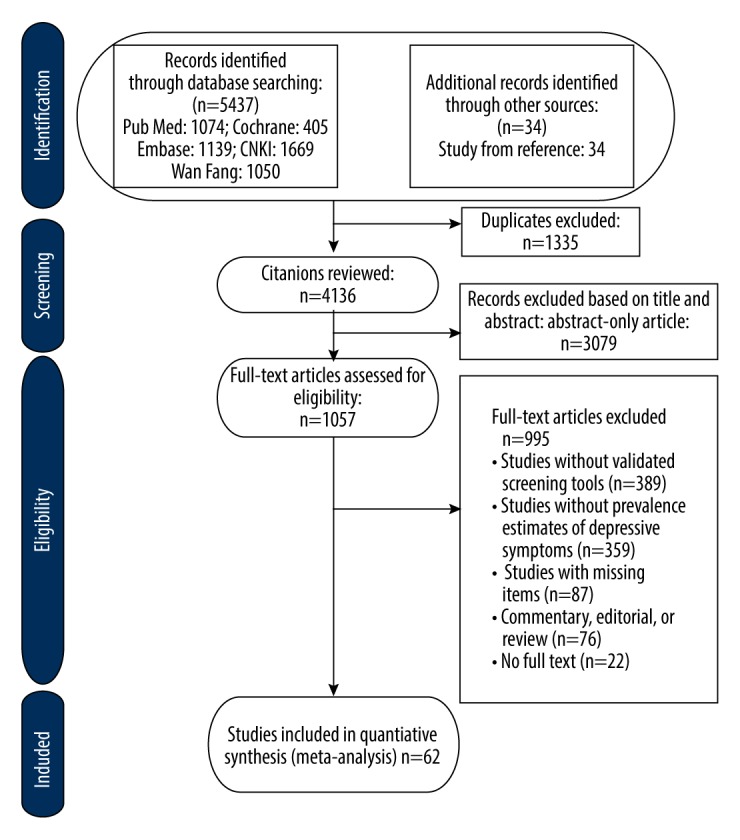

The following publications were excluded from this meta-analysis: (1) published reviews, conference abstracts, and opinion pieces or commentaries only presented with abstract; (2) studies with a sample population including undergraduates, patients, or groups who had a special vocation; (3) if there were multiple results emerging from the same cross-sectional dataset, only data from the paper with the largest sample size and the most stringent screening criteria was included; and (4) depressive symptoms were measured using the self-edited scales with no demonstrated psychometric properties. In the event of ambiguity, any differences at each stage were resolved by consensus and the involvement of another experienced expert (YX). Figure 1 demonstrates the selection process of this meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

Literature review flowchart.

Data extraction

The same group of reviewers independently screened the title and abstracts. According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 2 reviewers assessed all the eligible studies that could be retrieved from the academic database. Data items were extracted by the first author (JYL) from relevant articles using a standardized data collection sheet developed by the previous review, which included the surname of the first author, publication year, demographic characteristic, sample size, the prevalence of depressive symptoms, and the number of cases of depression reported in the primary studies or other subgroup variables (e.g., scales, gender, and grades). Then, the results were double-checked by the second author (JL). To acquire missing information of relevant studies, the corresponding authors were contacted.

Quality assessment

The quality of each study was assessed by the quality assessment instrument for epidemiological studies [26–28]. The instrument was applied to evaluate all included studies with the following 8 items: (1) the target population was clearly defined; (2) the sample was obtained through probability sampling methods; (3) having a representative sample; (4) non-responders were clearly described; (5) the response rate was great than 80% [29]; (6) having standardized data collection methods; (7) having good psychometrics measures to evaluate depressive symptoms; and (8) having confidence intervals for statistical estimates. Consistent with previous studies, articles were summed to give a total score out of 8, with each item assigned a score of 1 (“Yes”) or 0 (“No”). Discrepancies in scores of included studies were resolved through discussion to reach consensus.

Statistical analyses

Stata version 12.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) was used for all statistical analyses. The pooled prevalence of depressive symptoms estimates was based on the random-effects model, which gave an overall estimate across studies weighted by sample size, with the assumption of statistical heterogeneity among studies [30,31]. The magnitude of heterogeneity across studies was estimated using the I2 statistic, which shows the proportion of total variation of all included studies due to heterogeneity rather than change. The interpretation of I2 values shows that 25%, 50%, and 75% indicate low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively [32]. We calculated the pooled effect sizes, along with their respective 95% confidence intervals (CI). Subgroup analysis was conducted to explore potential moderating factors for heterogeneity, stratified by region, gender, grade, year of publication, and scales combined with cutoffs. We performed meta-regressions to identify the association of prevalence of depressive symptom with year of publication. Publication bias was examined by adjusted-comparison funnel plot symmetry, and Egger’s test was used to test the stability of the inverse funnel plot [33,34].

Results

Study characteristics

We initially identified 5437 articles through the search of 5 academic databases, of which 4136 were assessed after duplications were removed. Of these, 1057 remained after screening of titles and abstracts. On review of the full text, 62 papers that met the inclusion criteria were finally included in analysis. Of the 995 excluded articles, 359 did not provide prevalence estimates of depressive symptoms, 389 studies lacked validated screening tools, 87 studies lacked required items, 76 studies were commentary, editorial, or review, 62 studies reported the same population, and 22 articles did not include the full text. Figure 1 shows a flowchart of the selection process. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of all included studies. In these 62 studies, 232 586 children and adolescents were involved and the sample size ranged from 300 to 47 863. The year of publication covered a time span of 27 years, which ranged from 1991 to 2018. Of these 62 included studies, 8 different self-report rating systems were used in our analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 62 studies of depressive symptoms in the meta-analysis.

| Author (s) (year) | Province | Grades | Scale | Cutoffs | ESS | Case | Prevalence (%) | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu et al. (1991) [35] | Shandong | J | SDS | ≥50 | 537 | 135 | 25.14 | 4 |

| lu et al. (1999) [36] | Shandong | J,S | CES-D | ≥20 | 800 | 186 | 23.25 | 5 |

| Zhou et al. (2000) [37] | Jiangsu | J | SCL-90 | ≥2 | 726 | 110 | 15.15 | 5 |

| Yuan et al. (2000) [38] | Anhui | S | CES-D | ≥20 | 3157 | 512 | 22.5 | 4 |

| Mai et al. (2000) [39] | Guangdong | J,S | SCL-90 | ≥3 | 330 | 41 | 12.42 | 5 |

| Zhang et al. (2001) [40] | Anhui | J,S | CES-D | ≥20 | 12430 | 2834 | 22.8 | 5 |

| Zhang et al. (2001) [41] | Multiple Cities | J,S | SCL-90 | ≥2 | 912 | 51 | 5.6 | 5 |

| Cui et al. (2002) [42] | Anhui | J | SDS | ≥41 | 331 | 104 | 31.42 | 4 |

| Su et al. (2002) [43] | Anhui | S | Beck | ≥5 | 1902 | 805 | 45.5 | 4 |

| Tang et al. (2003) [44] | Hunan | P | DSRSC | ≥15 | 565 | 97 | 17.17 | 4 |

| Duan et al. (2004) [45] | Beijing | J,S | PHI | ≥60 | 5910 | 1584 | 26.8 | 5 |

| Sun et al. (2005) [46] | Tianjin | P,J | DSRSC | ≥14 | 516 | 78 | 15.1 | 4 |

| Feng et al. (2005) [47] | Sichuan & Chongqing | J,S | Beck | ≥5 | 2634 | 1115 | 42.3 | 5 |

| Shu et al. (2006) [48] | Guangdong | J | CDI | ≥19 | 300 | 33 | 11 | 3 |

| Xu et al. (2006) [49] | Jiangsu | J,S | CDI | ≥20 | 7161 | 1060 | 14.8 | 5 |

| Gu et al. (2007) [50] | Hebei | P | DSRSC | ≥15 | 522 | 94 | 18.01 | 4 |

| Zhang et al. (2007) [51] | Anhui | J | CES-D | ≥16 | 4524 | 1201 | 26.5 | 5 |

| Xu et al. (2008) [52] | Anhui & Guangdong | P | CDI | ≥19 | 3224 | 341 | 10.6 | 5 |

| Hong et al. (2009) [53] | Jiangsu | J | CDI | ≥20 | 2444 | 384 | 15.7 | 5 |

| Li et al. (2009) [54] | Guizhou | S | SDS | ≥50 | 2352 | 336 | 14.3 | 5 |

| Liu et al. (2009) [55] | Guangdong | P | CDI | ≥19 | 667 | 112 | 16.5 | 4 |

| Li et al. (2010) [56] | Henan | P,J | CES-D | ≥16 | 755 | 261 | 34.57 | 4 |

| Cao et al. (2011) [57] | Anhui | J,S | DSRSC | ≥15 | 5003 | 1191 | 23.8 | 5 |

| Liu et al. (2012) [58] | Beijing | J,S | CES-D | ≥16 | 1175 | 354 | 30.1 | 4 |

| Peng et al. (2012) [59] | Sichuan | S1 | CES-D | ≥31 | 5544 | 800 | 14.4 | 5 |

| Jia et al. (2012) [60] | Yunnan | J,S | CES-D | ≥20 | 7979 | 1802 | 22.6 | 5 |

| Zhang et al. (2012) [61] | Shanxi | J,S | DSRSC | ≥15 | 2363 | 545 | 23.1 | 5 |

| Shan et al. (2013) [62] | Shanghai | J,S | CES-D | ≥16 | 2761 | 767 | 27.8 | 5 |

| Chang et al. (2013) [63] | Shanghai | P,J | CES-D | ≥16 | 1250 | 494 | 39.5 | 3 |

| Luo et al. (2013) [64] | Heilongjiang | P,J | DSRSC | ≥15 | 1535 | 223 | 14.5 | 3 |

| Hu et al. (2013) [65] | Gansu | P | CES-D | ≥16 | 623 | 119 | 19.1 | 4 |

| Liang et al. (2013) [66] | Guangdong | J,S | CDI | ≥19 | 1087 | 205 | 18.86 | 4 |

| Zhu et al. (2013) [67] | Hubei | P,J,S | CDI | ≥19 | 1975 | 269 | 13.6 | 4 |

| Chang et al. (2013) [19] | Jiangsu | P | DSRSC | ≥15 | 749 | 33 | 4.41 | 3 |

| Guo et al. (2014) [68] | Henan | J,S | CES-DC | ≥29 | 1774 | 426 | 24 | 4 |

| Zhang et al. (2014) [69] | Zhejiang | J,S | DSRSC | ≥15 | 1939 | 334 | 17.23 | 4 |

| Guo et al. (2014) [70] | Guangdong | J,S | CES-D | ≥28 | 3186 | 205 | 6.4 | 5 |

| Shen et al. (2015) [71] | Hubei | J,S | CDI | ≥20 | 2283 | 281 | 12.6 | 4 |

| Wu et al. (2015) [72] | Beijing | P | CDI | ≥12 | 1472 | 457 | 31.04 | 3 |

| Wu et al. (2015) [73] | Guangdong | J,S | CES-D | ≥28 | 3042 | 307 | 10.1 | 4 |

| Guo et al. (2015) [74] | Shanghai | P,J | CDI | ≥19 | 950 | 135 | 14.21 | 4 |

| Wang et al. (2015) [75] | Guangdong | S | SDS | ≥53 | 1121 | 464 | 41.4 | 4 |

| Wang et al. (2015) [76] | Henan | P,J,S | CDI | ≥19 | 3002 | 430 | 14.3 | 5 |

| Guo et al. (2016) [22] | Multiple Cities | J,S | CES-D | ≥28 | 35893 | 2017 | 5.6 | 5 |

| Tan et al. (2016) [23] | Guangdong | J | CESD-10 | ≥8 | 1661 | 905 | 54.4 | 4 |

| Zhu et al. (2016) [77] | Hainan | P,J | CDI | ≥19 | 4866 | 1573 | 32.3 | 4 |

| Xie et al. (2016) [78] | Hubei | P,J,S | CDI | ≥19 | 2888 | 412 | 14.3 | 4 |

| Liu et al. (2016) [79] | Anhui | S | CES-D | ≥20 | 2768 | 1339 | 48.4 | 4 |

| Ding et al. (2017) [80] | Hubei | P,J,S | CES-D | ≥16 | 6406 | 1041 | 16.3 | 4 |

| Li et al. (2017) [81] | Guangdong | J | CES-D | ≥16 | 1015 | 238 | 23.4 | 3 |

| Jia et al. (2017) [20] | Shanghai | S | Beck | ≥5 | 928 | 517 | 55.7 | 3 |

| Zou et al. (2017) [82] | Shandong | J,S | CES-D | ≥16 | 492 | 200 | 40.7 | 3 |

| Wu et al. (2017) [83] | Zhejiang | J,S | CDI | ≥20 | 2000 | 250 | 12.5 | 4 |

| Zhang et al. (2017) [84] | Henan | J,S | CES-D | ≥20 | 1343 | 269 | 20.03 | 4 |

| Zhang et al. (2018) [85] | Hubei | P,J,S | CES-D | ≥16 | 5793 | 739 | 16.2 | 5 |

| Zhou et al. (2018) [86] | Multiple Cities | P,J | CES-D | ≥17 | 2679 | 544 | 20.3 | 4 |

| Zhang et al. (2018) [87] | Zhejiang | J,S | BDI-II | ≥14 | 3264 | 949 | 29.08 | 4 |

| Liu et al. (2018) [88] | Xinjiang | P,J | CDI | ≥19 | 3610 | 1195 | 33.1 | 4 |

| Peng et al. (2018) [89] | Chongqing | P,J | CDI | ≥19 | 3351 | 841 | 25.1 | 4 |

| Ji et al. (2018) [90] | Multiple Cities | P,J,S | CES-D | ≥28 | 47863 | 5570 | 11.6 | 6 |

| Qu et al. (2018) [91] | Xinjiang | J | SDS | ≥53 | 1335 | 465 | 34.8 | 4 |

| Lin et al. (2018) [92] | Xinjiang | P | CDI | ≥19 | 919 | 103 | 11.2 | 4 |

ESS – effective sample size; P – primary school; J – junior high school; S – senior high school; SDS – Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale; CDI – Children’s Depression Inventory; CES-D – Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression; SCL-90 – The Symptom Checklist subscales for depression; DSRSC – Depression Self-Rating Scale for Children; BDI-II – Beck Depression Inventory-II; Beck – Beck Depression Inventory; PHI – Psychological Health Inventory.

Prevalence of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents

The prevalence of depressive symptoms of all the included studies were described in Table 1, ranging from 4.41% to 55.7% in individual studies. The overall pooled prevalence of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents was 22.2% (95% CI: 19.9–24.6%, I2=99.6%, p<0.001), showing significant heterogeneity among studies.

Subgroup analyses and meta-regression

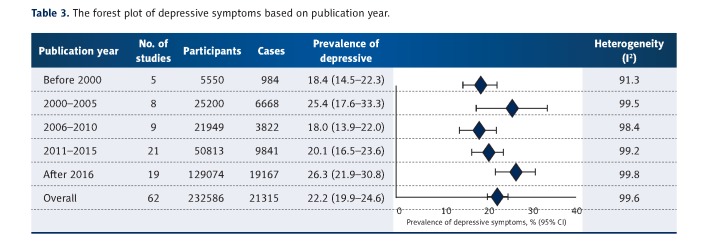

The results of meta-analyses stratified by date of publication and screening tool are summarized in Table 2. There were significant differences in the prevalence of depressive symptom by year of publication. The date of publication was divided into 5 sections. Five studies were published before 2000, the pooled prevalence of which was estimated as 18.4% (95% CI, 14.5–22.3%; I2=91.3%). Eight studies were published between 2001 and 2005, the pooled prevalence of which was estimated as 25.4% (95% CI, 17.6–33.3%; I2=99.5%). Nine studies were published between 2006 and 2010, the pooled prevalence of which was estimated as 18.0% (95% CI, 13.9–22.3%; I2=98.4%). Twenty-one studies were published between 2011 and 2015, the pooled prevalence of which was estimated as 20.1% (95% CI, 16.5–23.6%; I2=99.2%). Nineteen studies were published after 2016, the pooled prevalence of which was estimated as 26.3% (95% CI, 21.9–30.8%; I2=99.8%). Table 3 shows that the prevalence of depressive symptoms generally increased over time, while the meta-regression analysis showed that this trend was not associated with year of publication (I2=99.6%, p=0.30). The pooled prevalence of depressive symptoms was lowest with SCL-90 (cutoff ≥2, 10.3%; p<0.001) and highest with CESD-10 (cutoff ≥8, 54.5%; p<0.001). Participants with a higher grade showed greater risk of depressive symptoms: primary school, 17.5% (95% CI, 14.0–21.1%); junior secondary school, 21.9% (95% CI, 18.7–25.1%); and senior secondary school, 24.2% (95% CI, 19.9–28.6%). Nevertheless, meta-regression analysis revealed that grade was not associated with the prevalence of depressive symptoms (I2=99.1%, p=0.07). Females (22.3%; 95% CI, 19.5–25.0%) had a higher risk of depression than males (21.4%; 95% CI, 18.6–24.1%). Adolescents from rural areas (28.6%; 95% CI, 22.1–35.1%) had an obviously greater prevalence than these from urban areas (22.9%; 95% CI, 17.8–28.1%). Significant heterogeneity (I2 greater than 85%) was observed within these variables.

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses of the prevalence of depressive symptoms.

| Subgroup | Categories | No. of studies | Total No. of participants | Number of cases | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI | I2 (% with P-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scales | Beck | ||||||

| ≥5 | 3 | 5464 | 2437 | 46.7 | 39.4–53.9 | 96.4 (<0.001) | |

| BDI-II | |||||||

| ≥14 | 1 | 3264 | 949 | 29.1 | 27.5–30.6 | ||

| CDI | |||||||

| ≥12 | 1 | 1472 | 457 | 31.0 | 28.7–33.4 | ||

| ≥19 | 7 | 23615 | 5308 | 18.7 | 13.5–23.8 | 99.0 (<0.001) | |

| ≥20 | 5 | 17112 | 2316 | 13.2 | 11.3–15.1 | 92.3 (<0.001) | |

| CES-D | |||||||

| ≥8 | 1 | 1661 | 905 | 54.5 | 52.1–56.9 | ||

| ≥16 | 11 | 27473 | 5958 | 26.3 | 21.5–31.1 | 98.9 (<0.001) | |

| ≥20 | 6 | 28477 | 6942 | 25.5 | 18.7–32.3 | 99.4 (<0.001) | |

| ≥29 | 5 | 91758 | 8525 | 11.4 | 7.7–15.2 | 99.7 (<0.001) | |

| ≥32 | 1 | 5544 | 800 | 14.4 | 13.5–15.4 | ||

| DSRSC | |||||||

| ≥15 | 8 | 13192 | 2595 | 16.7 | 11.3–15.1 | 98.5 (<0.001) | |

| PHI | |||||||

| ≥60 | 1 | 5910 | 1584 | 26.8 | 25.7–27.9 | ||

| SCL-90 | |||||||

| ≥2 | 2 | 1638 | 161 | 10.3 | 0.9–19.7 | 97.4 (<0.001) | |

| ≥3 | 1 | 330 | 41 | 12.4 | 8.9–16.0 | ||

| SDS | |||||||

| ≥41 | 1 | 331 | 104 | 31.4 | 26.4–36.4 | ||

| ≥50 | 2 | 2889 | 471 | 19.6 | 8.9–30.2 | 96.6 (<0.001) | |

| ≥53 | 2 | 2456 | 929 | 38.1 | 31.6–44.5 | 91.0 (<0.001) | |

| Publication year | Before 2000 | 5 | 5550 | 984 | 18.4 | 14.5–22.3 | 91.3 (<0.001) |

| 2001–2005 | 8 | 25200 | 6668 | 25.4 | 17.6–33.3 | 99.5 (<0.001) | |

| 2006–2010 | 9 | 21949 | 3822 | 18.0 | 13.9–22.0 | 98.4 (<0.001) | |

| 2011–2015 | 21 | 50813 | 9841 | 20.1 | 16.5–23.6 | 99.2 (<0.001) | |

| After 2016 | 19 | 129074 | 19167 | 26.3 | 21.9–30.8 | 99.8 (<0.001) | |

| Grades | P | 19 | 41007 | 5753 | 17.5 | 14.0–21.1 | 98.9 (<0.001) |

| J | 31 | 63561 | 12857 | 21.9 | 18.7–25.1 | 99.1 (<0.001) | |

| S | 23 | 45725 | 9682 | 24.2 | 19.9–28.6 | 99.3 (<0.001) | |

| Gender | Male | 46 | 97085 | 16210 | 21.4 | 18.6–24.1 | 99.4 (<0.001) |

| Female | 46 | 97076 | 16021 | 22.3 | 19.5–25.0 | 99.3 (<0.001) | |

| Region | Rural | 13 | 23858 | 6097 | 22.9 | 17.8–28.1 | 98.9 (<0.001) |

| Urban | 13 | 22283 | 5151 | 28.6 | 22.1–35.1 | 99.3 (<0.001) | |

Table 3.

The forest plot of depressive symptoms based on publication year.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis, conducted by omitting each study in succession in each group, showed that no individual study significantly influenced the primary results.

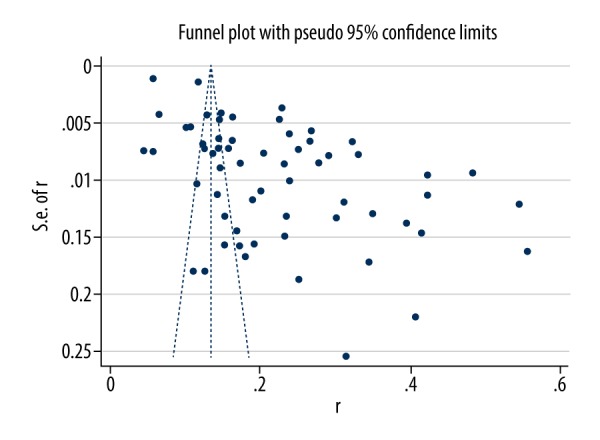

Publication bias

Significant asymmetry was visually observed in the funnel plot (Figure 2). Egger’s test (p<0.05) showed there were substantial publication bias in this analysis.

Figure 2.

Funnel plot of depressive symptoms.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis of 62 original studies involving 232 586 children and adolescents suggest that between 10.3% and 54.5% of adolescents screened positive for depression. The pooled prevalence in depressive symptom among children and adolescents in China was 22.2%, and these findings are reinforced by previous relevant meta-analyses [24].

Some studies have demonstrated that depression in adolescence is associated with higher risk of recurrent depressive episodes in adulthood [93] and increased comorbidity during adult life [94]. Since adolescent suffering from depression may commit suicide, making depression the second-to-third primary cause of death in this population [95], more effective interventions needed to be carried out early to prevent such tragedy. Adolescence is an extremely significant period for the building of personality and development of life skills. Once the process is interfered with depression during this period, a number of negative outcomes, such as dropping out of school, substance abuse, and unemployment, become more likely to occur throughout the lifespan [96,97]. Thus, this analysis highlights an urgent issue for children and adolescents.

In this analysis, the pooled prevalence estimate was higher than in 6 previous studies among teenagers in China [98–103]. When compared with other countries – 16.6% in Australia [104], 4.28% in Greece [105], 10.6% in Italy [106], and 17.3% in Korea [107] – this study also demonstrated a greater estimated prevalence of depressive symptoms. Previous research by Tang et al. [24] reported that the prevalence of depressive symptom was 24.3%, which is higher than the result in our analysis. This difference is likely mainly due to a larger sample size of participants covering a wider age range in the present study, which included primary school students, middle school students, and high school students. With regard to the cause of depression, which is a severe mental problem among youth, substantial research has been conducted to identify risk factors associated with depression, such as genetic risk (e.g., offspring of parents with depression) [108], family factors (e.g., family discord and poverty) [109], and stressful life events (e.g., academic pressure and interpersonal pressure) [110]. Although there are myriad risk factors facing youth, effective interventions aimed at depression, especially the early onset of depressive symptoms, are relatively scarce in China.

When stratified by year of publication and divided into 5 periods, the prevalence estimates of depressive symptoms were highest in the last period. Table 3 shows that the prevalence of depressive symptoms is positively associated with year of publication as a whole, but the difference was not significant in meta-regression analysis. The foremost reason for this association is that the quantity of studies involved in this article varied among different periods; there were fewer studies in the 1990s and more in the 2010s, which to some extent reflects an increased awareness of depression among Chinese researchers. Meanwhile, the rapid development of the society and economy in China likely contributes to mental health problems in children and adolescents. Under these circumstances, some studies reported that depression is becoming the most common concern of Chinese teenagers [111].

The prevalence estimates were closely linked to grade in the present study, which is consistent with a previous review [24]. Some possible explanations for this phenomenon identified by previous studies are tremendous academic pressure of entrance examinations, neurobiological changes, and increased interpersonal problems [112].

In the current study, 8 self-report rating scales with different cutoffs were included. The result revealed that a significant difference in the summary prevalence estimates existed among different screening tools, which was a major source of heterogeneity. Nevertheless, the prevalence estimates of epidemiological studies usually varied with screening instruments, samples, and survey methods [113]. Although this heterogeneity was unavoidable, screening scales with strong psychometric properties and identified cutoffs should be taken into consideration during the initial design, thus making it possible to make direct comparison with other countries.

In terms of gender, there were slight differences in the summary prevalence estimates in this study: 22.3% for females and 21.4% for males. Some researches associated maturation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and endocrine systems with gender differences in depressive symptoms [13,114]. In addition, our results were not in line with previous meta-analyses based on nationally representative samples [115], which reported that the OR (odds ratio) value between prevalence of depression in females and males was 2. It revealed that gender differences in depressive symptoms generally appeared among adolescents at the age of 12 years old and continued during puberty. The wide age range in our study may have narrowed the gender difference.

We found that children from rural areas had a significantly higher prevalence of depressive symptoms that children from urban areas (26.2% versus 27.5%, respectively). This result was consistent with many previous reports [116,117], indicating that relative poverty, lack of social support, and low income status are linked to high prevalence in depressive symptoms among children.

Several strengths of the present meta-analysis should be noted. There were 62 primary studies involving a large pooled sample size in this study, which provided greater statistical power. In addition, we conducted a complete search on both Chinese databases and English databases, generating a comprehensive coverage. However, our findings also have important limitations. Economic and social development is highly uneven among provinces in China, and our study did not cover all the provinces, which to some extent limits generalizability of the results. Secondly, the majority of studies used school-based samples, and thus might be more prone to selection bias, although it is widely accepted that surveys conducted in schools are about as accurate as those conducted in the community setting [118]. Thirdly, although subgroup analyses aimed at publication years combined with other variables were performed to overcome the substantial heterogeneity, the problem remained in this meta-analysis of epidemiological studies [119].

Conclusions

The trend of prevalence of depressive symptoms among Chinese children and adolescents as a whole has increased in the last 3 decades. Our findings could be useful to policy makers and service commissioners to better understand depressive symptom, a notable problem facing children and adolescents. Given that depressive symptoms can begin at an early age, be recurrent, and are associated with more poor outcomes, we emphasized mental health services and effective interventions for children and adolescents.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely acknowledge help from the following authors: Jia-Yan Qiu and Rong-Kun Wu.

Footnotes

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Pine D, Cohen PD, Brook J, Ma Y. The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(1):56–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costello EJ, Egger H, Angold A. 10-year research update review: The epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: I. Methods and public health burden. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(10):972–86. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000172552.41596.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costello E, Jane, Alaattin E, Adrian A. Is there an epidemic of child or adolescent depression? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;47(12):1263–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, et al. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: Systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006;367(9524):1747–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(1):8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Major depressive disorder in older adolescents: Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clin Psychol Rev. 1998;18(7):765–94. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fletcher JM. Adolescent depression and educational attainment: Results using sibling fixed effects. Health Econ. 2010;19(7):855–71. doi: 10.1002/hec.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keenan-Miller D, Hammen CL, Brennan PA. Health outcomes related to early adolescent depression. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41(3):256–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hasler G, Pine DS, Kleinbaum DG, et al. Depressive symptoms during childhood and adult obesity: The Zurich Cohort Study. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10(9):842–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnett R. Suicide. Lancet. 2016;388(10041):228. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beardslee WR, Brent DA, Weersing VR, et al. Prevention of depression in at-risk adolescents: Longer-term effects. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(11):1161–70. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thapar A, Collishaw S, Pine DS, Thapar AK. Depression in adolescence. Lancet. 2012;379(9820):1056–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60871-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seaton EK, Caldwell CH, Sellers RM, Jackson JS. An intersectional approach for understanding perceived discrimination and psychological well-being among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Dev Psychol. 2010;46(5):1372–79. doi: 10.1037/a0019869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou Q, Fan L, Yin Z. Association between family socioeconomic status and depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents: Evidence from a national household survey. Psychiatry Res. 2018;259:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Auerbach RP, Eberhart NK, Abela JR. Cognitive vulnerability to depression in Canadian and Chinese adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2010;38(1):57–68. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9344-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu J, Li J, Cuijpers P, et al. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms in Chinese older adults: A population-based study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27(3):305–12. doi: 10.1002/gps.2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker G, Gladstone G, Chee KT. Depression in the planet’s largest ethnic group: The Chinese. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(6):857–64. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang XL, Wang HY, Zhang Y. [Investigation and analysis of depression status of pupils in Zhenjiang city]. Chin J Child Heal Care. 2013;21(9):985–87. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jia YJ, Xie HT, Wang Q, et al. Survey of high school freshmen’s depression and its influencing factors. Chin J Child Heal Care. 2017;25(3):278–81. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan A, Franco OH, Wang YF, et al. Prevalence and geographic disparity of depressive symptoms among middle-aged and elderly in China. J Affective Disorders. 2008;105(1–3):167–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo L, Hong L, Gao X, et al. Associations between depression risk, bullying and current smoking among Chinese adolescents: Modulated by gender. Psychiatry Res. 2016;237:282–91. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan Y, Chen Y, Lu Y, Li L. Exploring associations between problematic internet use, depressive symptoms and sleep disturbance among southern Chinese adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(3):313–25. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13030313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang X, Tang S, Ren Z, Wong DFK. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among adolescents in secondary school in mainland China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affective Disorders. 2019;245:498–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boyle MH. Guidelines for evaluating prevalence studies. Evid Based Ment Health. 1998;1(2):37–39. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ibrahim AK, Kelly SJ, Adams CE, Glazebrook C. A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(3):391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loney PL, Chambers LW, Bennett KJ, et al. Critical appraisal of the health research literature: Prevalence or incidence of a health problem. Chronic Dis Can. 1998;19(4):170–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hotopf M, Hardy R, Lewis G. Discontinuation rates of SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants: A meta-analysis and investigation of heterogeneity. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:120–27. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitehead A, Whitehead J. A general parametric approach to the meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Stat Med. 1991;10(11):1665–77. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780101105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 2003;327(7414):557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1997;315(7109):629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sterne JA, Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: Guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(10):1046–55. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu XC, Guo CQ, Wang JY, et al. [Study of depression and related factors among 537 students of secondary schools]. Chinese Mental Health Journal. 1991;5(1):24–26. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu SC, Qu JG. [A study on depressive symptoms and its correlates among middle school students]. Journal of Sichuan Mental Health. 1999;12(3):184. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou DM, Tan HZ, Li SQ. [Research on mental health status of 726 adolescents and its influential factors]. Bulletin of Hunan Medical University. 2000;25(2):144–46. [in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuan CJ, Tao FB. [Behaviors related to intentioned injury and depression among high school students]. China Public Health. 2000;16(12):1148–49. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mai MZ, Guo ZH, Liang YX. [Analysis of SCL-90 in middle school students]. Chinese Journal of School Doctor. 2000;14(3):216–17. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang HB, Tao FB, Zeng GY, et al. [Depression and its correlates among middle school students in Anhui province]. Chinese Journal of School Health. 2001;22(6):497–98. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang M, Wang ZY. [Mental health state of middle or high school students]. Chinese Mental Health Journal. 2001;15(4):226–28. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cui M, Ao X. [A study on anxiety, depression, life events, and coping style of meddile school students]. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;10(2):124–26. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Su H, Wang BJ, Chen HM, et al. [Study on the emotion of depression and anxiety of middle school students and its relative factors]. Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medical Science. 2002;11(2):196–98. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang J, Su LY, Zhu Y, et al. [Depressive problems in Chinese pupils]. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;11(4):264–66. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duan JL, Che HS, Lv RR. [Investigation of mental health status in middle school student]. Chinese Journal of School Doctor. 2004;18(4):302–6. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun L, Zhou TH. [A survey of depressive symptoms in adolescents between the ages of eight and fifteen]. Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medical Science. 2005;14(2):154. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feng ZZ, Zhang DJ. [Differences of middle schools’ depressive symptoms development in gender, age and grade]. Chinese Journal of Clinical Rehabilitation. 2005;9(36):32–34. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shu MY, Wang JT, Liu RG, et al. [Investigation and analysis of influential factors on junior adolescent depression]. Chinese Mental Health Journal. 2006;20(7):451–54. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu F, Wang CY, Li JQ, et al. [Study on the prevalence of depression and its risk factors among high school students in Nanjing]. Chinese Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;27(4):324–27. [in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gu JX, Guo LX, Wang JY. [A survey on depressive symptoms of 522 child between the ages of eight and ten]. Maternal & Child Health Care of China. 2007;21(22):2949–50. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang LH, Ma EJ, Tao FB, et al. [Depression and the influencing factors among students in two junior high schools in Hefei]. Chinese Journal of School Health. 2007;28(6):504–6. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu J, Lin DN, Wang JJ, et al. [Comparison of influential factors for depressive symptoms among primary school students in Hefei and Shenzhen]. Chinese Mental Health Journal. 2008;22(4):246–49. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hong X, Li J, Xu F, et al. Physical activity inversely associated with the presence of depression among urban adolescents in regional China. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:148–57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li YF, Tang YZ, Zhang DR, et al. [A survey of anxiety and depression in 2364 students of senior high school]. Journal of Guiyang Medical College. 2009;34(4):386–88. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu C, Mei J. [Relationship between children’s depression and children’s social desirability]. Chinese Journal of Child Health Care. 2009;17(5):503–5. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li XC, Zhao LN, Yang SB, Han J. [Relationship between depression symptom and family factors in children]. Maternal & Child Health Care of China. 2010;25(12):1665–67. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cao H, Qian Q, Weng T, et al. Screen time, physical activity and mental health among urban adolescents in China. Prev Med. 2011;53(4–5):316–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu PP, Hong W, Niu LH. [A current situation survey and influence factors of adolescent depression in suburban district]. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2012;20(5):668–69. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peng Z, Liao J, Wang Q, et al. [Relationship between smoking, drinking and depression of middle school students in Chengdu]. Journal of Preventive Medicine Intelligence. 2012;28(1):31–33. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jia M, Huang Y, Ping NN, et al. [Character and gender factors in with depressive symptoms middle school students in Yunnan national regions]. Journal of Kunming Medical University. 2012;33(1B):5–7. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang L, Meng RH, Li H, Li FF. [A study on the anxiety and depression emotional disorders for high school students of one city in Shanxi province]. Journal of Changzhi Medical College. 2012;26(5):324–27. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shan Z, Deng G, Li J, et al. Correlational analysis of neck/shoulder pain and low back pain with the use of digital products, physical activity and psychological status among adolescents in Shanghai. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e78109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chang XD, Shi JH, Huang L, et al. [Correlation between suicidal ideation and depression of junior high school students]. Chinese Journal of Health Psychology. 2013;21(2):255–57. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Luo K, He LN, Shang J, et al. [Study on depression symptoms and associated family environment factors in primary and middle school of Daoqing]. Chinese Journal of Child Health. 2013;21(1):85–87. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hu CX, Hu YX. [A study of depressive symptoms among higher elementary school students in Lanzhou]. Gansu Science and Technology. 2013;29(19):86–87. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liang WD, Yang J, Chen KY, et al. [Depressive symptoms and the influencing factors among middle school students]. Medical Journal of Chinese People’s Health. 2013;25(19):19–22. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhu JH, Zhong BL, Xu LJ. [Depressive symptoms among 7–17-year-old students of primary and middle schools in Wuhan area: An epidemiological survey]. Chinse Journal of Brain Diseases and Rehabilitation. 2013;3(1):35–39. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guo H, Yang W, Cao Y, et al. Effort-reward imbalance at school and depressive symptoms in Chinese adolescents: The role of family socioeconomic status. Int J Env Res Pub He. 2014;11(6):6085–98. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110606085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang WW, Zhou DS, Hu ZY. [Depressive symptoms and its related risk factors among middle school students in Ningbo]. Chinese Journal of School Health. 2014;35(10):1503–5. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Guo L, Deng J, He Y, et al. Prevalence and correlates of sleep disturbance and depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents: A cross-sectional survey study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(7):e005517. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shen M, Gao J, Liang Z, et al. Parental migration patterns and risk of depression and anxiety disorder among rural children aged 10–18 years in China: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e007802. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wu LJ, Wei DM, Gao AY, et al. [Association between physical activity, screen-based media use and depressive symptoms among children]. Chinese Journal of School Health. 2015;36(3):326–29. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wu H, He Y, Guo L, et al. [Depression and influencing factors among middle school students, Shanwei]. South China Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2015;41(5):424–29. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guo Q, Zhang XY, Wen XS, et al. [Survey on status and influencing factors of depressive symptoms among students in two middle schools in Minhang district of Shanghai]. Health Education and Health Promotion. 2015;10(6):426–32. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang M, LIu CF, Hou YH, et al. [Status and related factors of anxiety and depression among high school student in Shenzhen special economic zone]. Chinese Journal of Social Medicine. 2015;32(6):460–62. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang HZ, Yang ML, Lou XM, et al. [Depressive symptoms among primary and high school students in Zhengzhou city]. Chinese Journal of Public Health. 2015;31(8):1005–7. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhu HQ, Li Q, Wang L, et al. [Prevalence of depressive symptoms and its influence factors among primary and high school students in Haikou]. Chinese Journal of School Health. 2016;37(9):1345–48. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xie S, Yu XM, Wang YL, et al. [Prevalence and correlation of early life stress and depression among adolescents in Wuhan city]. Chinese Journal of Public Health. 2016;32(12):1680–83. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liu XY, Wang J, Guo Y, et al. [Depressive symptoms and its association with academic achievement and negative attribution style among key senior high school students]. Chinese Journal of School Health. 2016;37(11):1655–57. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ding H, Han J, Zhang M, et al. Moderating and mediating effects of resilience between childhood trauma and depressive symptoms in Chinese children. J Affective Disorders. 2017;211:130–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li JB, Lau JTF, Mo PKH, et al. Insomnia partially mediated the association between problematic Internet use and depression among secondary school students in China. J Behav Addict. 2017;6(4):554–63. doi: 10.1556/2006.6.2017.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zou M, Wang YY, Yin XB. [Analysis on the status and influencing factors for depression during adolescence]. Modern Preventive Medicine. 2017;44(18):3360–63. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wu HN, Shao F, Lin B. [Preventive measures and factors influencing depression level of adolescents]. Modern Practical Medicine. 2017;29(5):670–72. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang XJ, Tian QF, Hu HH, et al. [Depressive symptoms of provincial demonstration middle school students and its relationship with life event in Zhengzhou]. Chinese Journal of Health Psychology. 2017;25(4):491–93. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang M, Han J, Shi J, et al. Personality traits as possible mediators in the relationship between childhood trauma and depressive symptoms in Chinese adolescents. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;103:150–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhou M, Zhang G, Rozelle S, et al. Depressive symptoms of Chinese children: Prevalence and correlated factors among subgroups. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(2):283–93. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15020283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang YY, Jing P, Zhou DS, et al. [Cellphone use and depression in middle school students: A cross-sectional study]. Chinese Journal of Public Health. 2018;34(5):682–86. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liu SR, Miao RQ. [Depression symptoms and influencing factors of primary and middle school students in Shihezi City of Xinjiang]. Occup and Health. 2018;34(9):1258–61. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Peng LL, He F, Yang JW, et al. [Pubertal timing and depressive symptom among primary and junior middle school students in urban Chongqing]. Chinese Journal of School Health. 2018;39(2):215–18. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ji D, Chen H, Chao M, Li XY. [Effect of family atmosphere and parental education level on depression among adolescents]. Chinese Journal of Public Health. 2018;34(1):38–41. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Qu M, Zhang CG. [Study on comorbid anxiety and depression of 1335 junior high school students in Kuitun City of Xinjiang]. Chinese Journal of School Doctor. 2018;32(9):666–69. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lin SL, Wang D, Cheng YJ, et al. [Current status of social anxiety and depression among primary school students in Urumqi, China]. Chinese Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics. 2018;20(8):670–74. doi: 10.7499/j.issn.1008-8830.2018.08.013. [in Chinese] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McCrone P, Knapp M, Fombonne E. The Maudsley long-term follow-up of child and adolescent depression. Predicting costs in adulthood. Eur Child Adoles Psychiatry. 2005;14(7):407–13. doi: 10.1007/s00787-005-0491-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40(1):57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Windfuhr K, While D, Hunt I, et al. Suicide in juveniles and adolescents in the United Kingdom. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(11):1155–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ. Mental health, educational, and social role outcomes of adolescents with depression. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2002;59(3):225–31. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.3.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Naicker K, Galambos NL, Zeng Y, et al. Social, demographic, and health outcomes in the 10 years following adolescent depression. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(5):533–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hong X, Li JQ, Liang YQ, et al. [Investigation on overweight, obesity and depression among middle school students in Nanjing]. Chinese Mental Health Journal. 2008;22(10):744–49. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Li C, Wang H, Cao X, et al. [Depressive symptoms and its related factors among primary and middle school students in an urban-rural-integrated area of Chongqing]. Journal of Hygiene Research. 2013;42(5):783–88. [in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liang WD, Yang J, Chen KY. [Depressive symptoms and the influencing factors among middle school students]. Medical Journal of Chinese Peoples Health. 2013;25(19):19–22. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wang TZ, Chen MC, Sun YH. [Research on children’s depression and the influence of left-behind status in rural area]. Chinese Journal of School Health. 2011;32(12):1445–47. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wang X, Sun Y, An J, et al. [Gender difference on depressive symptoms among Chinese children and adolescents]. Zhonghua Liuxingbingxue Zazhi. 2013;34(9):893–96. [in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Juan XU, Lin DN, Wang JJ. [Comparison of influential factors for depressive symptoms among primary school students in Hefei and Shenzhen]. Chinese Mental Health Journal. 2008;22(4):246–50. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bond L, Toumbourou JW, Thomas L, et al. Individual, family, school, and community risk and protective factors for depressive symptoms in adolescents: A comparison of risk profiles for substance use and depressive symptoms. Prev Sci. 2005;6(2):73–88. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-3407-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Giannakopoulos G, Kazantzi M, Dimitrakaki C, et al. Screening for children’s depression symptoms in Greece: The use of the Children’s Depression Inventory in a nation-wide school-based sample. Eur Child Adoles Psychiatry. 2009;18(8):485–92. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0005-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Frigerio A, Pesenti S, Molteni M, et al. Depressive symptoms as measured by the CDI in a population of northern Italian children. Eur Psychiatry. 2001;16(1):33–37. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(00)00533-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kwak YS, Lee CI, Hong SC, et al. Depressive symptoms in elementary school children in Jeju Island, Korea: Prevalence and correlates. Eur Child Adoles Psychiary. 2008;17(6):343–51. doi: 10.1007/s00787-008-0675-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rice F, Harold G, Thapar A. The genetic aetiology of childhood depression: A review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2002;43(1):65–79. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhong BL, Ding J, Chen HH, et al. Depressive disorders among children in the transforming China: An epidemiological survey of prevalence, correlates, and service use. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30(9):881–92. doi: 10.1002/da.22109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lewinsohn PM, Allen NB, Seeley JR, Gotlib IH. First onset versus recurrence of depression: Differential processes of psychosocial risk. J Abnorm Psychol. 1999;108(3):483–89. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tepper P, Liu X, Guo C, et al. Depressive symptoms in Chinese children and adolescents: Parent, teacher, and self reports. J Affective Disorders. 2008;111(2–3):291–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Liu X, Kurita H, Uchiyama M, et al. Life events, locus of control, and behavioral problems among Chinese adolescents. J Clin Psychol. 2000;56(12):1565–77. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(200012)56:12<1565::AID-7>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Demir T, Karacetin G, Demir DE, Uysal O. Epidemiology of depression in an urban population of Turkish children and adolescents. J Affective Disorders. 2011;134(1–3):168–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Pine DS, Ernst M, Leibenluft E. Imaging-genetics applications in child psychiatry. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 2010;49(8):772–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Salk RH, Hyde JS, Abramson LY. Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: Meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychol Bull. 2017;143(8):783–822. doi: 10.1037/bul0000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lee G, McCreary L, Kim MJ, et al. Depression in low-income elementary school children in South Korea: Gender differences. J Sch Nurs. 2013;29(2):132–41. doi: 10.1177/1059840512452887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wesselhoeft R, Sorensen MJ, Heiervang ER, Bilenberg N. Subthreshold depression in children and adolescents – a systematic review. J Affective Disorders. 2013;151(1):7–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, et al. Annual research review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56(3):345–65. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Winsper C, Ganapathy R, Marwaha S, et al. A systematic review and meta-regression analysis of aggression during the first episode of psychosis. Acta Psychiat Scand. 2014;128(6):413–21. doi: 10.1111/acps.12113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]