Abstract

One constant refrain in evaluations and reviews of decentralization is that the results are mixed. But given that decentralization is a complex intervention or phenomenon, what is more important is to generate evidence to inform implementation strategies. We therefore synthesized evidence from the literature to understand why, how and under what circumstances decentralization influences health system equity, efficiency and resilience. In doing this, we adopted the realist approach to evidence synthesis and included quantitative and qualitative studies in high-, low- and middle-income countries that assessed the the impact of decentralization on health systems. We searched the Medline and Embase databases via Ovid, and the Cochrane library of systematic reviews and included 51 studies with data from 25 countries. We identified three mechanisms through which decentralization impacts on health system equity, efficiency and resilience: ‘Voting with feet’ (reflecting how decentralization either exacerbates or assuages the existing patterns of inequities in the distribution of people, resources and outcomes in a jurisdiction); ‘Close to ground’ (reflecting how bringing governance closer to the people allows for use of local initiative, information, feedback, input and control); and ‘Watching the watchers’ (reflecting mutual accountability and support relations between multiple centres of governance which are multiplied by decentralization, involving governments at different levels and also community health committees and health boards). We also identified institutional, socio-economic and geographic contextual factors that influence each of these mechanisms. By moving beyond findings that the effects of decentralization on health systems and outcomes are mixed, this review presents mechanisms and contextual factors to which policymakers and implementers need to pay attention in their efforts to maximize the positive and minimize the negative impact of decentralized governance.

Keywords: Decentralization, equity, efficiency, resilience, community, realist, health system

Key Messages

To optimize the impact of decentralization, it is important to move beyond the often-repeated finding (of evaluations and systematic reviews) that the impact of decentralized governance on health system performance is mixed; sometime positive, sometime negative. But instead of seeking generalizable and once-and-for-all conclusive evidence, what is important is to explain these mixed results in a way that may inform implementation strategies.

To provide these explanations, we conducted a realist synthesis of the evidence—we sought to identify how contextual factors and mechanisms interact to produce mixed results on three outcome measures (equity, efficiency and resilience) which are increasingly recognized as goals to which health systems must aspire globally, and on which the impact of decentralized governance has repeatedly been or can conceivably be demonstrated to be mixed.

The various ways in which these three mechanisms are influenced by context (institutional, socio-economic and geographic) explain the mixed results: ‘Voting with feet’ (altering the existing patterns of inequities in the distribution of resources); ‘Close to ground’ (allowing for use of local initiative, information, feedback, input and control); and ‘Watching the watchers’ (allowing for mutual accountability and support between multiple centres of governance).

Together with insights from their experience, policymakers and implementers involved in decentralization reforms or working in settings in which governance is decentralized can apply insights from our theorized and identified links between context, mechanisms and outcomes as an analytical tool to interpret, explore and understand the factors at play in their own unique settings, and why they generate outcomes, intended and otherwise.

Introduction

Since the 1980s, decentralization reforms have been adopted in many countries (Manor, 1999), with significant impact on health system governance. But long before and since, most countries have experienced some form of decentralization. While the drivers of decentralization vary from one country to another, in many cases, it is not initiated in the health sector, and rarely takes place in the health sector alone. Decentralization may be implemented to stimulate economic growth, reduce rural poverty, strengthen civil society, deepen democracy or to delegate responsibilities onto lower-level governments (World Bank, 1987; Manor, 1999; Cueto, 2004; Labonté et al., 2007). In addition, decentralization reforms may be informed by ideologies that eschew central planning and prioritize competitive markets and bottom-up decision-making (Hayek, 1945). And in the 1980s, decentralization reforms were also implemented in line with WHO recommendations and health system reforms triggered by the Alma Ata Declaration to address the limitations of centrally governed health systems to reach underserved rural communities in low- and middle-income countries (WHO, 1987; Görgen and Schmidt-Ehry, 2004).

However, decentralization reforms are bound to have varying levels of success in achieving their intended effects on health systems, such as equity in population health outcomes, health system efficiency and health system resilience, including how community engagement influences these effects. But it is also possible that one or more of these measures of impact may improve at the expense of others. Given that decentralization reforms are often implemented independent of considerations for their impact on the health system, in some settings, decentralization reforms may interact with previously centralized health systems, and in other settings they may interact with existing forms of decentralization in the health system. It is therefore important that health sector stakeholders understand and are equipped with strategies to maximize the positive and minimize the negative impacts of decentralization reforms (and of these interactions) on a range of measures in different settings. In this article, we synthesized insight from the literature to understand why, how and under what circumstances decentralization influences equity, efficiency and resilience in the health sector.

These three health system goals (equity, efficiency and resilience) were selected because of their conceptual richness, the extensive (and unresolved) literature on the relationship between them and decentralization, and their emerging currency as major goals to which health systems need to aspire globally (see Sumah et al., 2016; Dwicaksono and Fox, 2018; Aligica and Tarko, 2014). While the literature on the definition of these terms is extensive and often contested (see Braveman and Gruskin, 2003; Cylus et al., 2016; and Barasa et al., 2017), for the purposes of this review, we adopted basic and broad definitions. We defined equity (inter-jurisdictional and intra-jurisdictional) in terms of the absence of unnecessary and avoidable disparities in health outcomes based on social, economic, demographic or geographical differences (Whitehead, 1992). We defined efficiency as the relation between health system resource inputs (i.e. costs) and either outputs (e.g. number of patients treated) or health outcomes (e.g. lives saved) (Palmer and Torgerson, 1999). And we defined resilience as the capacity of a system to experience shock without major consequences, determined by the adaptability and robustness of a system to potential acute shocks or chronic stress (Tarko, 2017; Abimbola and Topp, 2018).

But in our efforts to review the literature, we found it necessary to also clarify the meanings of ‘decentralization’. Notably, the word is used in two ways. First, to describe the process of decentralizing the governance of a jurisdiction or of specific functions; i.e. decentralization as intervention. The word is often used in this sense in the health systems literature—as an arrangement in which the power, resources or responsibilities are transferred from central to peripheral actors (Mills et al., 1990). In this top-down view, different forms of decentralization are defined in reference to whom central actors makes the transfer (Rondinelli et al., 1983, Mills et al., 1990): devolution (to autonomous governments, independent of the central government); de-concentration (to peripheral offices within the administrative structure of the central government); delegation (to entities or organizations outside the central government or its ministries and agencies, but which can be controlled by the central government); and privatization (to private for-profit or non-profit entities using contracts). These definitions presuppose that decentralization is a top-down process deriving from central governments.

The second way in which the word ‘decentralization’ may be used is to describe a phenomenon (UNDP, 1999; Treisman, 2002), rather than an intervention. And implicit in this use of the term is that power, resources or responsibilities are widely distributed in society (albeit often unevenly), such that decentralization describes the default state of affairs in human society, prior to or irrespective of the decision to centralize governance. Hence, centralization may occur in a top-down process in which central governments take over some power, resources or responsibilities away from individuals, communities and sub-national jurisdictions; or in a bottom-up process in which individuals, communities and sub-national jurisdictions, for different purposes, choose to cede some power, resources or responsibilities to a central government. Understood in this bottom-up sense, decentralization becomes a process of redistributing powers, resources or responsibilities away from a central government. The distinction between decentralization as ‘intervention’ and as ‘phenomenon’ highlights—(1) that governance is not necessarily centralized ab initio; and (2) that an understanding of why centralization emerges in the first place, can inform efforts to decentralize hitherto centralized functions.

Centralization may occur by fiat, e.g. by the imperial edict of an expansionist monarchy or of a colonial power, or by the decree of a military dictatorship. It may also emerge organically as sub-national entities combine their resources to reap economies of scale or to adjust for externalities (negative and positive) that may arise when each organizes their affairs independently. An example of how adjusting for positive externalities may lead to centralization is when sub-national jurisdictions come together to provide public goods or services because once provided, neighbouring sub-national jurisdictions cannot be excluded from their benefits (i.e. to avoid the free rider effect), e.g. access roads, security, protection from invasion or immunization services. An example of how adjusting for negative externalities may lead to centralization is when sub-national jurisdictions together provide public goods and services because neighbouring sub-national jurisdictions may share in bearing the costs of provision, even though they may not share in the benefits, e.g. sourcing water from a finite pool that is commonly owned or accessible by neighbouring sub-national jurisdictions (see Cremer et al., 1996).

But there are limits to centralization. The costs of time and effort required to achieve and sustain co-operative interactions (i.e. transaction costs); e.g. information, negotiation and enforcement costs may outweigh the potential benefits of centralization. For example, Buchanan and Tullock (1962) argued that due to transaction costs, ‘collective action should be organized in small rather than large political units’ and indeed that ‘large units may be justified only by the overwhelming importance of the externalities that remain after localized and decentralized collectivisation’. In addition, centralization may progressively exclude actors at the periphery from participation in governance. And this may reduce the capacity of central governments to resolve disputes or design policies that require local input. Further, sub-national entities may be ideologically committed to decentralization (e.g. the example of the United States constitution) or have highly developed independent governance structures such as monarchies and parliaments (e.g. European Union and United Arab Emirates) or retain strong ethnic identities (e.g. post-colonial African countries such as Kenya and Nigeria), allegiance to which may override any real or potential benefits of centralization of governance (Ziblatt, 2008).

The theoretical benefits of decentralization (i.e. governance in small units), are often part of the inspiration for decentralization reforms in previously centralized nations. For example, the expectation that the proximity of local officials to people in sub-national jurisdictions will increase the likelihood that policies will be informed by local knowledge and expertise—based on the assumption that local officials will understand local preferences and have the incentive to respond to them (Hayek, 1945; Musgrave, 1959). Or the expectation that proximity will make people more able to discipline local officials, thus ensuring that local public goods and services reflect local preferences—based on the assumption that people will be well informed about the quality of services to expect and which levels of government are designated or required to provide various services (Ostrom et al., 1994). Or that people moving to neighbouring jurisdictions when they are not satisfied with public services in theirs will promote competition—based on the assumption that people are mobile enough to move (Tiebout, 1956; Oates, 1972). Or that having governments at multiple levels will strengthen state capacity—based on the assumption that sharing power will reduce conflicts by dousing ethnic and separatist tensions, increase social learning through local political engagement and increase policy stability because of the greater number of actors involved in decision-making processes (Faguet et al., 2015). But reviews have shown that these assumptions often do not hold true in many countries and settings (Robinson, 2007; Conyers, 2007; Faguet et al., 2015).

Evaluations of health system decentralization have consisted of quantitative analysis of large sub-national, national or cross-country data, have treated decentralization in different settings as the same (rather than the range of possible forms it tends to take depending on context), and have not accommodated the possibility that the various assumptions about the mechanisms through which decentralization generates outcomes hold true to different extent in different settings (Rondinelli et al., 1983; Samoff, 1990; Manor, 1999; Hutchinson and LaFond, 2004; Smoke, 2010). For these reasons, evaluations have yielded mixed and ambiguous results, and the evidence points to the mediating effects of context and capacity on the link between decentralization and health system performance (Atkinson and Haran, 2004; Bossert et al., 2003; Riutort and Cabarcas, 2006; Uchimura and Jutting, 2009); e.g. the disposition of community members, health workers and health managers to the health system, and the wider political culture in which the health system operates (Atkinson and Haran, 2004). Thus, the assumptions framing previous and current decentralization reforms may not be grounded in evidence.

In spite of its complexity, the evidence on decentralization is often reviewed as if it is a simple intervention for which it is possible to arrive at a final, conclusive and generalizable answer, instead of being a complex intervention with multiple interacting components, with outcomes that are path dependent, and are neither straightforward, linear nor predictable, but highly depend on human agency and context (Robalino et al., 2001; McCoy et al., 2012; Rifkin, 2014; Casey, 2018). These sources of complexity are neither sufficiently explored (nor, indeed, explorable) in approaches to systematic review which focus on whether specific desired outcomes are generated or not. Hence, previous systematic reviews sought to identify generalizable and conclusive evidence on whether the impact of decentralization on health systems is positive or negative (Sreeramareddy and Sathyanarayana, 2013; Sumah et al., 2016; Cobos Muñoz et al., 2017; Liwanag and Wyss, 2017; Dwicaksono and Fox, 2018), with the outcomes of interest defined in specific, quantitative terms, thus limiting the range of evidence to review (Sreeramareddy and Sathyanarayana, 2013; Sumah et al., 2016; Dwicaksono and Fox, 2018), with limited potential for transferring insights and lessons from one setting to another.

In this review, we took an alternative approach—i.e. the realist approach; an approach which seeks to explain how context influences the outcomes of interventions (through effects on group or individual behaviour), and by so doing allows lessons and insight to travel. The realist approach to evidence synthesis takes its origin from realism and critical realism within philosophy and the social sciences, and has been applied, first for programme evaluation and subsequently for evidence synthesis on health and other social programmes as a theory-driven logic of inquiry to explain what works, for whom, under what circumstances and in what respects (Pawson and Tilley, 1997; Pawson et al., 2004). The philosophical premise of critical realism emphasizes: (1) that science should go beyond mere observation and measurement; (2) that in their complexity, social phenomena are built on the actions of social agents and how these agents interpret the phenomena; (3) that these social agents are in turn constrained or enabled by social structures; (4) that the interplay between social agents and social structures influences the processes and outcomes of social phenomena and interventions; and (5) that science should seek to understand how agent–structure interactions generate change (Robert et al., 2012; Lodenstein et al., 2013).

In turn, the premise of realist synthesis is that outcomes of social interventions or phenomena are generated through human agency within certain structures. In realist synthesis, theories are either tested or refined by identifying how structures—i.e. contextual factors (C)—influence the production of outcomes (O) by triggering human agency—i.e. mechanisms (M). Note that the word ‘mechanism’ here refers to the reasoning and behaviour of participants and stakeholders in a social process or interventions (Wong et al., 2013). Therefore, decentralized governance influences change through the interactions between structure and agency; between context and mechanism. And the links between context, mechanisms and outcomes are expressed in the form of context-mechanism-outcome (C-M-O) configurations; with patterns that often refine theories (e.g. theories that explain why decentralized governance fails or succeeds) by incorporating specific contextual contingencies (Pawson et al., 2004). What we sought to do in this review was understand how the relationships between context and mechanism influence the effects of decentralization. We sought to answer the question—how and under what circumstances does decentralized governance impact on health system equity, efficiency and resilience?

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted a search of Medline and Embase via Ovid, and also of the Cochrane database of systematic reviews (from inception to October 2017) using the following terms: #1[‘Health governance’ OR ‘governance of health’ OR ‘health administration’ OR ‘health care administration’ OR ‘health care governance’ OR ‘health system’ OR ‘health service’] AND #2[Decentralisation OR decentralization OR decentralised OR decentralized OR devolution OR delegation OR de-concentration OR privatization OR ‘power dispersal’ OR ‘less centralised’ OR ‘less centralized’]. The search terms were adapted from a previous systematic review which we (SA and LB) had conducted on how decentralization impacts on equity of health outcomes, in which our search strategy was developed with the guidance of a research Librarian, and preliminary search terms were identified and pre-tested on Google Scholar (Sumah et al., 2016). Hence, we did not conduct a formal initial scoping of the literature. In conducting and reporting this realist synthesis, however, we followed the steps and procedures which were outlined in the RAMESES publication standards for realist synthesis (Wong et al., 2013).

We included quantitative and qualitative studies assessing the effects of decentralized governance (whether as a phenomenon or as an intervention) on health system equity, efficiency and resilience. To be included, studies of the effects of decentralization had to be conducted with data from more than one jurisdiction (national, sub-national or community)—so that within each study there was scope for contextual variation that enabled an exploration of the influence of varying jurisdictional context on outcomes. In addition, included studies must examine the direct consequence of decentralization (not of an intervention implemented alongside)—to help enhance the focus of the review as our specific interest was in studies in which the primary issue under consideration was decentralization. We excluded studies of decentralization of the management of specific diseases or vertical programmes—these studies examined a different intervention/phenomenon (i.e. decentralization of the delivery of specific services) from the one under inquiry (i.e. decentralization at a government or a system-wide level in such a way that it could potentially impact a broader range of unspecified services).

Data extraction and categorization

Application of the search terms during the initial database searches yielded 905 entries from Medline and an additional 2221 entries from Embase and 22 entries from the Cochrane database of systematic reviews, which after selection based on title and abstract, was reduced to 103 in Medline, 157 in Embase and 3 in Cochrane. Selections from the databases were subsequently merged, with the titles and abstracts searched a second time and also duplicates identified, resulting in 84 publications, 6 of which were non-English language papers—5 in Portuguese and 1 in Spanish—were excluded. And after the full text of the remaining 78 papers were read, an additional 27 papers were excluded based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria and based on the judgement of the reviewers (SA in consultation with MB) on their relevance and rigour. The judgement on the appraisal of the contribution of any section of each paper were made based on two criteria—relevance (i.e. whether it can contribute to our understanding of the impact of decentralization on any of the outcome measures of interest); and rigour (i.e. whether the method used to generate each piece of data relevant to the review is credible). Bias was minimized by the multidisciplinary (combining health policy and systems research, global public health, medicine, economics, epidemiology, and social science) nature of the three-person review team.

We adapted the stepwise approach to realist analysis proposed by Danermark et al. (2002)—see Table 1 for the steps. Initially piloted using four randomly selected papers, the data extraction was conducted iteratively (SA in consultation with LB and MB). The data extraction was conducted using an Excel data extraction spreadsheet into which general study information, study question, design and duration, the unit of analysis and how many, and the reported indicator whether measured quantitatively or assessed qualitatively. Into these forms, we subsequently entered which outcome category of interest were measured or assessed in each study, including verbatim extractions of text relevant to understanding the links between these outcomes, context that enabled or constrained them, and the mechanisms that explain the relationship. However, these data and insights were not uniformly reported and were therefore identified variously from the introduction, description of methods, reported results, and in interpretative reflections or discussion section of the different papers. When they were not immediately apparent from the introduction to or findings of a study, we relied on the interpretation and explanation of the authors on the different categories of data that we extracted from each paper.

Table 1.

Steps taken in the realist analysis

| Step 1: Identifying outcomes (description) | This involved reading and re-reading the papers, first to gain familiarity with the studies and then subsequently to identify events (i.e. outcomes) which occur as a result of decentralization, i.e. how decentralized governance changes the actions, decisions and relations of health system actors. The outcomes of interest are changes in equity, efficiency and resilience within health systems—or the actions, decisions and relations of health system actors that may result in such changes. |

| Step 2: Identifying contextual components of outcomes (resolution) | The articles were further reviewed to identify important contextual components (enablers and constraints) of the identified outcomes. These include the formal and informal rules or institutional that govern the actions, decisions and relations of health system actors, the socio-economic circumstances of individuals, groups, communities and of entire jurisdictions, and circumstances related to the physical geography of a community, sub-national or national jurisdiction. In addition, context included peculiar design features and characteristics of decentralization in each setting. |

| Step 3: Theoretical re-description (abduction) | This involved situating identified outcomes and their contextual components within theories to better understand what they represent. Three theories resulted from and informed our analysis:

|

| 3. The transaction costs theory of the firm predicts that economic agents will organize production within firms (i.e. centralize) when the costs of co-ordinating exchange through the market are greater than within a firm (Coase, 1937). However, the distribution of the costs and benefits of centralization (and, by extension, of decentralization) between providers and users vary in different settings. On the provider-side, while larger, centralized, providers incur higher internal transaction costs (thus reducing efficiency), they can also leverage size in external transactions as they reap economies of scale, (but central decision-making may ignore local context). On the user-side, with centralized provision, users may benefit from reduced transaction costs (in the form of search and information costs, and monitoring and enforcement costs) due to recognizable homogeneity in products, prices and quality across operating units, and as they avoid repeated transactions with different providers (Abimbola et al., 2015). But users may also incur costs if centralized firms control a large share of the market (thus charging higher prices), or as they ignore local realities. | |

| Step 4: Identifying mechanisms (retroduction) | This involved examining the identified outcomes and their contextual enablers or constraints with the aim of arriving at the reasoning processes and system capabilities that resulted in the observed patterns across countries. The reasoning processes and system capabilities were identified by moving back and forth between the empirical data the theories applied in this review to develop explanation for the identified pattern of outcomes and their contextual components. |

We searched passages of each paper for events that occurred as a result of decentralization—and these were coded as ‘outcomes’. To identify (in)equity as an outcome, we sought quantitatively measured outcomes, or the actions, decisions and relations of health system actors that result from decentralization. We also identified quantitative measures of efficiency, and the actions, decisions and relations of actors which may prevent or lead to inefficiencies in spending or resources use. And we identified features of decentralized systems and the actions, decisions and relations of actors that may prevent or lead to resilience. Each of these outcomes was accompanied with notes about factors (institutional, socio-economic, and geographic—see Abimbola, 2019) that either enabled or constrained them—and these were labelled as context (of note, given the variability in the range of ways in which decentralized governance is enacted in practice, we treated decentralization as a generic entity, such that the peculiar design features and characteristics in a setting constitutes context). Informed by referring to previous and subsequent passages in each paper, outcome-context matchings were tagged with sets of individual or group behaviour which explain them, and which were gained or exist due to decentralization. These sets of behaviour were then linked to theories which may explain them. The list of potential theories expanded as coding proceeded and were refined and adjusted until there was a coherent scheme of three that broadly account for these effects of decentralization. And disagreements in coding and discrepancies in interpretation were discussed and decided by consensus among the authors.

Theoretical framing

To identify the underlying mechanisms, we read and discussed the papers using a retroductive analysis; i.e. shuttling between empirical data and theory using both inductive and deductive reasoning to explain the outcomes-context matches (see Step 4 in Table 1). Based on our experience conducting primary and secondary studies of decentralization in the health system, our familiarity with the political economy literature on decentralized governance, and on the insight arising from the outcome-context matches in the papers included in this review, three sets of theories informed our analysis (see Step 3 in Table 1 for further details): First, the multi-level framework which defines governance at three levels such that weaknesses at one level can be assuaged by governance at another level: ‘constitutional’ (governments at functioning at various distances from health service operations on the ground), ‘collective’ (community-based groups such as local health boards and community health committees or close-to-community governments with significant community input) and ‘operational’ (individuals and providers within the local health market) (Abimbola et al., 2014). Second, the exit–voice–loyalty framework such that ‘exit’ occurs across communities or sub-national jurisdictions in response to unfavourable quality of life or services, but when the ‘exit’ option is not available, people are constrained to ‘loyalty’ and thus may use ‘voice’ to demand improvements (Hirschman, 1970). Third, the transaction costs theory which predicts that economic agents will govern production within ‘firms’ (i.e. centralize) when the costs of co-ordinating economic exchange through the market (i.e. decentralizing) are greater than the costs of governing production and exchange within a (centralized) firm (Coase, 1937).

However, these theories were only the starting point in constructing the C-M-O configurations. The theories are, by their nature, broad in their potential application. In their application to the effects of decentralization on health systems, they became the scaffolding that held together the ‘fragments of evidence’ (Pawson, 2006, p. 67) identified from the studies included in the review. In the process of retroductive analysis, each of the theories was transformed into three sets of C-M-O configurations—as the contextual factors on which each is contingent accumulated, and as the mechanisms that link them to each outcome of interest became more apparent, and as they were triangulated among one another and by alternating the starting point of potential explanations of how decentralized governance influences each outcome between contexts and mechanisms. The three theories each transformed into a mechanism: ‘exit–voice–loyalty’ became the ‘Voting with feet’ mechanism (e.g. beginning with the notion that people move in response to variation in quality of life and services, it progressively became clearer the conditions under which this ‘voting with feet’ occurred as we examined the link between such movements and the outcomes of interest); ‘transaction costs’ became the ‘Close to ground’ mechanism (e.g. beginning the notion that there is a size or scale at which a system functions optimally, we homed in on the role of information and proximity among stakeholders as we sought to identify how size or scale affect the outcomes of interest); and ‘multi-level governance’ became the ‘Watching the watchers’ mechanism (e.g. beginning the notion of backup between the multiple levels of governance, we identified the conditions under which mutual accountabilities result in the outcomes of interest).

Findings

From a total of 51 publications, 25 countries were represented in this review (3 of the included papers had 2 countries each) with both high-income countries, and low- and middle-income countries: there were 5 papers featuring each of Brazil and Italy, 4 featuring each of Indonesia and Tanzania, 3 featuring each of China, Nigeria and Spain; 2 featuring each of Chile, Mexico, the Philippines and the USA; and 1 featuring each of Argentina, Canada, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ghana, Guatemala, India, Israel, Lao, Nepal, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Russia and Zambia. We identified three mechanisms triggered or made possible by decentralization as an intervention or phenomenon: ‘Voting with feet’, ‘Close to ground’ and ‘Watching the watchers’. In reporting our findings, we used superscripts to refer to the paper from which each insight was derived, linked to a second list of references with the 51 publications (see Supplementary Appendix I). This is because in many settings, decentralization reforms are in constant flux such that the studies that we reviewed only provided snapshots in time and often do not represent the current reality of the countries or sub-national jurisdictions in which they were conducted. Our analysis was therefore focussed on mechanisms rather than countries. As such, countries were not specifically named in the findings, but we referred to a separate list of references for interested readers to track the source of each finding and insight in Supplementary Appendix I. In addition, please see Supplementary Appendix II for examples of each of the three mechanisms in different countries — ‘Voting with feet’ in Italy, ‘Close to ground’ in Brazil and ‘Watching the watchers’ in Nigeria.

Mechanism I—Voting with feet

The mechanism got its name from Tiebout (1956) who theorized how decentralization generates efficiencies, and argued that people respond to varying levels of public goods (e.g. government services) and the varying prices at which they are offered (e.g. tax rates) in a local jurisdiction by ‘voting with their feet’—i.e. moving from one local jurisdiction to another, seeking to maximize their personal utility. Their choices on where to live, Tiebout argued, leads to the provision of local public goods in line with the tastes of residents, thereby sorting the population into optimum communities. However, while this theory emphasizes efficiency, i.e. sorting into communities based on ability to pay, it ignores equity. This mechanism is therefore primarily triggered by the distribution of wealth between jurisdictions, such that equity is the main outcome linked to it. ‘Voting with feet’ reflects how decentralization as an intervention may either exacerbate or assuage existing inequities in the distribution of people, resources and outcomes within a jurisdiction (due to decentralization as a phenomenon) which may lead to increased movement of resources across local jurisdictions.

Equity

Decentralization allows sub-national units fiscal space to use resources (from taxes or resources) generated in their jurisdiction—wealthier jurisdictions increase their health budget post-decentralization and poorer ones (which may even experience a decline in their health budget) less so.1–5 However, equalization policies before, during or after decentralization (in form of inter-governmental transfers or national spending or insurance programmes to provide health services as a right) may limit the exacerbation of existing inequities in expenditure, usage or outcomes of health services.6–9 But the effectiveness of inter-governmental equalization transfers depends on whether the transfers are based on informal relationships and negotiation between individual sub-national jurisdictions with the national government (in which case wealthier jurisdictions have the upper hand)3,10 or whether they are based on explicit and formal formulaic rules, the effectiveness of which, in turn, depends on the considerations captured in the formula. The impact of equalization transfers is limited when the formula is based only on population and geographical size, but have more impact when it incorporates unmet need, age distribution, rurality, distribution of health outcomes, level of poverty, own-source fiscal contribution, quality-of-life indicators, institutional capacity, and distance to reach communities (given the cost of visits to monitor and enforce rules).6,8,10–12 However, circumstances in which funds transfer is delayed, or insufficient relative to the budget (worse in poorer jurisdictions as they depend more on national government transfers) limit the effectiveness of equalization transfers.4,11–13 Decentralization may remove the equalizing effects of allocating health budgets centrally, which may have allowed wealthier jurisdictions to subsidise poorer ones.4

Inter-governmental transfer of funds may also create or exacerbate inter-jurisdictional inequities. This occurs when the first level of sub-national government is the main recipient of equalization funds, which are further transferred across one or more levels of government in a cascading arrangement in which each sub-national government has discretion in transferring resources to the next, lower-level government. The higher levels of government tend to retain funds, and lower levels of government experience an imbalance between available resources and responsibility for service delivery, with poorer jurisdictions worse off than wealthier ones.13,14 But such effect is avoided, and instead inter-jurisdictional equity is promoted, when the national government makes direct allocation to the lowest level of government to deliver primary health care services.8 However, beyond the attrition of funds that occur in transfers between multiple levels of government, there is also a tendency for sub-national governments to spend their retained funds ‘close to home’; i.e. mainly in the capital of the sub-national jurisdiction (urban area) thus further disadvantaging rural communities.13–16 Sub-national government administrators spend ‘close to home’ because high-ranking administrators tend to limit their field visits to easily accessible locations, and because the more costly higher level health facilities (secondary and tertiary facilities) are located in the capital, consuming public funds for health inequitably as households in rural communities tend to depend, instead, on public sector primary healthcare facilities. One consequence of this pattern of spending is that because of their lower salaries, health workers at the primary health care level seek to work at higher levels of care which are funded by better resourced governments.3,13,14

Institutional capacity (e.g. for policy guidance and strategic planning) is often unevenly distributed between sub-national jurisdictions, and is therefore another contextual enabler of inter-jurisdiction inequity. Institutional capacity tends to align with the wealth of a jurisdiction, predict health system performance and health outcomes, and improve over time with decentralization, suggesting a learning effect.3,11,17–21 Existing differences in institutional capacity and wealth between regions is accentuated by decentralization in settings where the costs of cross-border movements to access health services are covered by patients’ jurisdiction of residence. Wealthier jurisdictions capitalize on this opportunity to improve their balance of ‘health’ trade with poorer neighbours, by investing in high-quality private providers.22,23 Poorer jurisdictions lose revenue as they transfer funds to their wealthier neighbours to cover the costs of their residents who cross borders to access higher quality specialist services as induced by private providers—with proximity, expenses on travel and accommodation expenses do not constrain movements. To limit inequities arising from cross-border movements, national governments may cap the amount of cross-border payments, thus limiting the financial incentive for private providers to compete for patients, and inducing neighbouring jurisdictions to arrange for selective specialization and pre-budget plans, thus limiting inequities and unforeseen expenses.11,20 Indeed, such cross-border arrangements can limit inter-jurisdiction inequity, as poorer jurisdictions may not be able to provide all required services.11 Even without such arrangements, poorer neighbours of wealthy jurisdictions may deliberately underspend on health as their residents are able to access services nearby. But on the other hand, poorer neighbours may be progressively induced to increase their health spending as they bid for the same goods (especially highly skilled health workers) in the same market as their wealthy neighbours who are able to offer higher prices.9,24,25

Like patients, health workers also vote with their feet; they move from lower to higher resourced jurisdictions. Prior to decentralization reforms, the national (or higher level) government may be able to recruit and deploy health workers to work in lower-level jurisdictions, e.g. districts and townships—although due to pre-existing inequities, high-skilled health workers may not be retained in the rural or remote jurisdictions.5,26–28 But this becomes worse post-decentralization, when the responsibility to recruit health workers is transferred to these lower-level jurisdictions which then essentially have to recruit locally. This improves retention of lower-skilled health workers (as they could be sourced locally)—the lowest cadre of formal health workers are consistently retained in rural communities as they are typically trained to work specifically in primary health care.5,13,26–28 However, decentralization limits the ability of rural or poorer local jurisdictions to recruit higher skilled health workers, loosens the controls on the movement of health workers that higher levels of government could exert under centralized governance or their ability to transfer health workers between health facilities in different local jurisdictions to adjust for any imbalance in the distribution of health workers, to the benefit of rural and remote jurisdictions.27,28 Likewise, decentralization may also exacerbate existing inequities by giving rise to greater competition between jurisdictions for health workers, as wealthier jurisdictions—usually with higher urban population—are able to fund more attractive remuneration packages, leaving poorer jurisdictions worse off.5,24 Further, greater inequity in the distribution of high-skilled health workers may result from institutional arrangements put in place by higher level governments to govern the process through which lower-level governments recruit health workers, by creating costly bureaucratic processes that require lower-level governments to obtain approval and permission at each stage in the process of recruitment.26

Local jurisdiction governments sometimes choose to invest in health services that can generate revenue, due to post-decentralization financial strain on poorer local jurisdictions, thus worsening existing intra-jurisdictional inequities. To generate revenue for the government, they invest in private goods (e.g. medicines and curative services), and reduce spending on public goods with non-excludable benefits (e.g. sanitation, environmental health, monitoring and evaluation, preventive services—including in-service training for health workers to provide preventive services.1,4,5,29 Weak institutional capacity among poorer jurisdictions may also lead to the development of lower-quality prevention projects and low reimbursement of the cost of services to the non-working population, disproportionately affecting low-income individuals and households in a jurisdiction.3,21 The role of the private sector is significantly greater in jurisdictions that exhibit higher inequalities,30 and health facilities in poorer jurisdictions often introduce user fees to make up for reduced funding from higher level governments post-decentralization. This pushes the middle class to ‘exit’ into the formal private sector (which is only slightly more expensive) and health care professionals become entrepreneurial and start their own private practice due to higher demand for such services (the middle class does not use voice—as they are sensitive to higher taxes and so tend to favour privatization). The low-income individuals in such jurisdictions bear the brunt of such inadvertent privatization, as they vote with their feet by using informal or single provider formal private services, or waiting till their illness becomes an emergency.16,27,29,31 Because some jurisdictions have more low-income people than others, intra-jurisdiction inequities may imply or trigger inter-jurisdiction inequity.4

Efficiency

Changes in health system efficiency occur because patients ‘vote with their feet’ to and from a neighbouring jurisdiction, with limited travel and accommodation restrictions. Poorer jurisdictions with wealthier neighbours experience efficiency losses (due to non-occupancy of already budgeted hospital beds as they continue to pay the fixed costs of their hospitals and for the care their residents receive in other jurisdictions), and wealthier jurisdictions experience efficiency gains (as patients coming from other jurisdictions use inputs that otherwise may be underused).22,32 These outcomes occur where universal coverage means that sub-national jurisdictions cover the costs of their residents. Otherwise, neighbours of wealthy jurisdictions can reap efficiency gains by under-investing in health services while maintaining high service coverage as their residents use services across the border.9 But to reap efficiency gains, poorer jurisdictions require the capacity (often lacking) to strategically plan and implement efficiency measures—under-investing in anticipation of cross-border services, or formally outsourcing selected services to neighbouring regions.11,20,23 Wealthier neighbours of poorer jurisdictions can also incur high spending (i.e. lose efficiency) by delivering services to residents of neighbouring jurisdictions. In addition, remotely located jurisdictions incur greater expenditure for similar levels of healthcare coverage as otherwise comparable jurisdictions, due to the greater costs of attracting high-skilled health workers and procurement processes.9 Further, in poorer jurisdictions where decentralization leads to financial strains, privatization of services (by introducing user fees), or decline in quality of services (from the loss of high-skilled health workers), results in reduced number of patient visits per available health worker as patients vote with their feet and demand for public sector health services diminishes.27

Mechanism II—Close to ground

‘Close to ground’ reflects how having governance closer to the people (from the transfer of responsibilities to or the existence of responsibilities at local levels) allows for better use of local initiative, information, feedback, input and control. This mechanism functions not by enabling accountability, but simply by increasing the level of local input and feedback on decision-making. Proximity facilitates information exchange; and being able to make appropriate rules, change them in response to realities on the ground, monitor and enforce rules at lower cost compared with when governing is done at a distance. The ‘close to ground’ mechanism draws the notion of information asymmetry in health care relations (Arrow, 1963). Information asymmetry exists not only in the interactions between patients and providers at the operational level; but also in the interactions between actors at other levels of governance and the operational level. The extent of information symmetry is thus proportional to the distance between constitutional/collective governance actors and the operational level where day-to-day decisions are made in communities and health facilities (Abimbola et al., 2014).

Equity

Governing ‘close to ground’ means political leaders and administrators can better use local information and take local realities into account, thereby making decisions that benefit the poor, such as increased coverage of prevention services (leading to reduced use of curative services), overall access to services (preventive and curative), and health promotion initiatives (e.g. sanitation).1,6,8,11,25,30,33–39 This pattern of outcome is limited in jurisdictions that lack (1) ability to generate local revenue and so rely on higher level governments for revenue, which are either earmarked or allocated with conditionalities that limit local initiative and discretion1,5,10–12,27,33,34,40; and (2) political authority or institutional capacity to generate or use resources (e.g. locally mobilized funds) for pro-poor initiatives, such as incentives to attract and retain required health workers.5,26–28 Governing close to the ground, however, facilitates local hiring, leading to improved retention and reduced absenteeism, although this does not apply to high-skilled health workers who are more difficult to recruit locally.26,28,41 The effect of governing close to the ground on reducing inequity is enabled with increasing extent of decentralized decision-making, 6,33,34,36 and the existence of a local boards (or community health committees) with the authority to establish policy priorities (i.e. proximate collective level of governance), as they facilitate resource decisions informed by community needs, community support for health services and securing resources; with members including people with political access, professional credibility or technical expertise and with the support of NGOs and local traditional leaders.11,25,36,39,41–43 But governing close to the ground may also result in low-quality staff for health facilities due to nepotism by local political elite who influence staff employment, transfer, in-service training, and promotion, in contexts of weak accountability between local politicians and the people, and diminished supervision by higher levels of government post-decentralization.5,26–28,41

Efficiency

Effects of governing ‘close to ground’ on equity have consequences for efficiency: (1) investing in preventive services leads to reductions in the use of curative services; (2) flexibility in using resources allow governments of local jurisdictions to use incentives to attract and retain high-skilled health workers; and (3) hiring locally leads to improved retention (thus avoiding the costs of repeated recruitment processes), and reduced absenteeism (thus avoiding the costs of paying absentee staff). Efficiency also results when higher level decision-makers mandate cost-savings with performance agreements. But such measures can negatively impact on quality of services, except when such performance agreements include ensuring quality of services in a context where there is institutional capacity at both central (regulation and information systems) and local (for strategic planning) levels to ensure compliance, with opportunities for cross-learning among decentralized units.19,21,44 And closely linked to how the ‘close to ground’ mechanism functions is the concept of economies of scale—i.e. the closer to the ground, the smaller the scale of operation. And because efficiency tends to improve with higher population within a decentralized jurisdiction, there is a tension between governing close to the ground and efficiency gains from economies of scale.18,24,32,45 Efficiency does not improve by increasing the extent of decentralized decision-making, as this limits the ability of local jurisdictions to benefit from economies of scale and co-ordination of resources across multiple local jurisdictions.28,36,44 Thus, local jurisdictions which are only partly decentralized are more efficient than non-decentralized and fully decentralized jurisdictions.32,34,46

Health systems are most efficient when they combine both centralization and decentralization; centralization of functions that benefit from economies of scale (purchasing and information systems) and decentralization of functions that require close to ground decision-making (service delivery and procurement budgeting).18,32,44,46,47 Combining centralization and decentralization can also ensure a level of uniformity, without which the ‘voting with feet’ mechanism may be triggered. Efficiency requires day-to-day decision-making close to service delivery points, and centralized economies of scale decision-making; e.g. efficiency gains result from decentralizing the purchase of services to local units (which do not provide services but contract them out to autonomous hospitals), because due to proximity, such local units are able to tailor resources to local needs; make appropriate rules for service delivery; change them flexibly in response to local circumstances; and have fewer providers over which they superintend, thus reducing the cost of monitoring and enforcing rules.32 In another example, hospitals that are part of hospitals groups operated by the same parent organization, are more efficient when only some of their activities (e.g. for which there are economies of scale) are centralized while day-to-day operational decisions are decentralized (i.e. left to the discretion of individual hospitals), than when all activities in the group are centralized.46 Similarly, hospitals that voluntarily come together (within loose contractual networks) to transfer some control from individual hospitals to a central body to co-ordinate the activities (e.g. for which there are economies of scale) are more efficient than individual hospitals operating independently.46

Mechanism III—Watching the watchers

‘Watching the watchers’ reflects the mutual accountability relations between levels of governance that are multiplied by decentralization. This mechanism captures how each of the three levels of governances (constitutional, collective and operational) watches and responds to the other two—with a closed loop of mutual watching, ideally leaving no governance actor unwatched. This mechanism takes its name from a Latin phrase by the Roman poet Juvenal—Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?, variously translated as ‘Who will guard the guardians?’ or ‘Who will watch the watchers?’—which has been applied to mean every governance actor must be held accountable (Hurwicz, 2008), by actors within the same level of governance (e.g. between legislatures and executives) or across different levels of governance (e.g. between community groups and governments). Notably, the multiple centres of governance may also function as backup to assuage or compensate for deficiencies due to weaknesses at one or more levels of governance.

Equity

There are equity implications of the ability of different levels of government to hold one another accountable, which may be constrained by constitutional provisions that abolish hierarchical relationship between levels of government (national/central, provincial/state and district/local), such that higher level governments do not have a mandate to audit lower-level governments, and lower-level governments are not obliged to report to higher level governments.4,13,18,25,28,29,48 In such instances, the constitutional expectation is that accountability will function horizontally, through the legislatures at each level of government; an expectation that tends to go unfulfilled as such legislatures may either not exist or may rely on the executive for their understanding of health issues (wealthier jurisdictions are more likely to have better informed legislatures) therefore, supporting policies that will help the executive to generate revenue; e.g. greater spending on curative services instead of preventive services.28,29,41 The constitutional provisions that remove lower-level governments from the ongoing monitoring, support and policy influence of higher level governments leave those jurisdictions (worse when poorer) under the direction of administrators without training or experience, especially when decentralization is implemented within a short time frame due to pressure for quick reforms, instead of a slow and deliberate process that is planned over time.3,4,11,20,28,33,49 Further limiting the capacity of governments are high costs of monitoring in geographically large countries or sub-national jurisdictions.3,14,33

With the lack of constitutional authority to hold lower-level governments to account for equity, tools used by higher level governments to influence lower-level governments include enacting new laws to reinstate such powers, persuasion, earmarked funds and financial incentives in the form of counterpart funds, with uneven, and often limited effectiveness.8,18,49 In addition, strong influence of higher level governments can also limit the responsiveness of lower-level governments to their own local constituents.18 Even then, low-income people often do not have the power to demand accountability, and middle-income people who do, tend to hold lower jurisdiction governments accountable for spending on curative and hospital services, rather than the more pro-equity preventive services.24,29 But in fiscally accountable local jurisdictions (i.e. wealthier jurisdictions which collect their own taxes and so enjoy higher revenue), health care is typically a main priority of constituents, and political agency leads to expansion of health expenditure, implementation of universal primary health care, and lower levels of health inequalities.30,33,45 And in poorer local jurisdictions where revenue depends on allocation from higher level governments, bottom-up accountability is weak, and local elections or constituency feedback do not influence outcomes, such that inequities prevail if lower-level governments are not held accountable by higher level governments.14 In addition, the continued exercise of control on the health expenditure of poorer local jurisdictions by higher level governments, is used as an excuse by lower-level governments to shift blame for poor performance to higher level governments, thus evading accountability to their population.13,20,25,40

However, having local health boards or community health committees facilitates bottom-up accountability to constituents, whether their activities are directed at their local governments or at local service providers. But the boards and committees are limited in this role by: low expectations or lack of information on the minimum standard to expect from service providers or governments; lack of awareness of their roles in decision-making, cultural attitudes that encourage respect for authority; access to alternative source of formal health services nearby; use of individual patron-client relations to resolve immediate health problems which diminishes the necessity to engage in collective pressure to improve local health services; low social capital in form of existing community-based organizations that provide fora for expressing health-related needs; high opportunity cost of attending meetings for board or committee members who have to take time out of income-earning activities; high cost of attending meetings in jurisdictions and communities with large land areas and distant settlements especially among low-income members; high cost of accessing government officials due to long travel distance to reach local government offices; not having responsive governments officials to attend committee or board meetings; lack of support from local NGOs, high-income community members, and individuals with high level of legitimacy such as traditional leaders; lack of autonomy to make their own rules and rules that govern health in their community or jurisdiction; and lack of accountability for finances (raised by their efforts or from NGOs or governments) among themselves and to the community.10,15,16,25,29,33,39,41,43 These contextual constraints are more an issue in the rural/poorer jurisdictions, compared with urban/wealthier jurisdictions.

Efficiency

Inefficiencies may prevail when lower-level government officials are not held accountable for efficiency in local health spending.14,20,21 And such inefficient health spending by sub-national governments (typically of poorer jurisdictions) can be as high as to constitute a burden on the national budget (to which wealthier jurisdictions contribute disproportionately more than poorer jurisdictions). Tensions can arise because poorer jurisdictions incur deficits while wealthier jurisdictions bear the costs, thus threatening the sustainability of comprehensive and universal national health systems financed based on solidarity among sub-national jurisdictions. The national government, may then over time, progressively cease to cover the deficit, imposing a sanction which compels sub-national governments which are unable to contain health expenditure to generate additional resources by increasing local taxes and/or user fees; decisions with political consequences for sub-national governments.20,21 In addition, the existence of a local health board (with community representatives) created after or existing as part of decentralization reforms contributes to reducing corrupt practices (which are more likely to occur in local jurisdictions whose budgets depend on inter-governmental grants and not locally generated revenue) and absenteeism among local health system managers, and to improving the perception of quality and satisfaction among service users—this effect improves with time—the older the health board, the greater the effect.42,48,50 The contextual factors that constrain local health boards or community health committees in ‘watching the watchers’ to influence health system equity also apply to how they influence health system efficiency.

Resilience

The multiple centres of governance in decentralized systems allows for a ‘backup’ or ‘shock-absorber’ effect such that weaknesses of one category of actors, or at one centre of governance may be compensated for by governance by other actors within the same, or at another centre of governance. And this ‘backup’ or ‘shock-absorber’ effect may happen vertically (between levels of government) or horizontally (between neighbouring jurisdictions). For example, the local health boards and community health committees within a jurisdiction or community may confer resilience on health systems as they step in to fill the space left by governments in the provision of public goods—by contributing funds, material and manual labour towards ensuring the supply of health services.13,15,25,51 And the existence of multiple levels of government creates a situation in which health services in a jurisdiction has multiple sources of funding (national/central, provincial/state, district/local and health board/committee) such that if/when one fails, funding resources remain available to ensure continued (even if sub-optimal) service provision.3,13,15,18,25,36,49 In addition, each level of government may provide health services independently of one another within the same local jurisdiction—a sub-national jurisdiction may have national/central government service providers (typically tertiary care), provincial/state government service providers (typically secondary care) and local/district government service providers (typically primary care) such that if/when one level of government fails, the providers financed by other levels of government remain available to ensure continued (even if sub-optimal) service provision—but this tends to favour people in more urban settings where tertiary and secondary healthcare facilities are typically located.3,13,36 Again, the same contextual factors that constrain how local health boards or community health committees, in ‘watching the watchers’, influence health system equity and efficiency, also apply to how they influence resilience.

Discussion

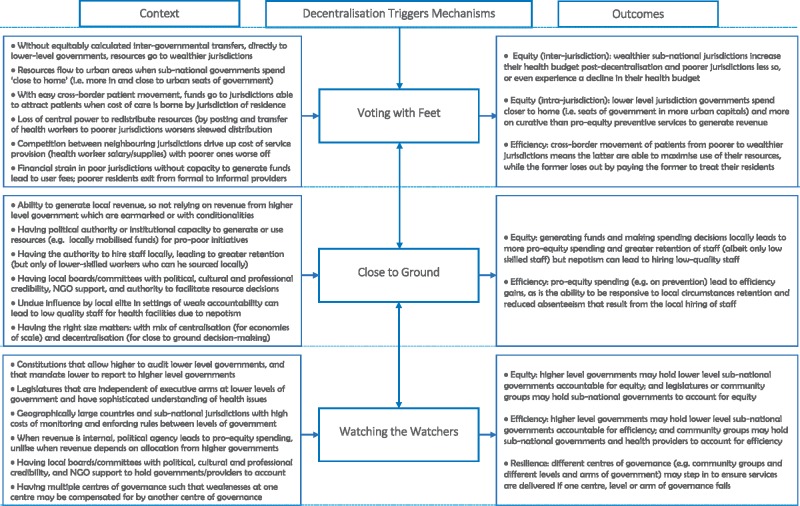

Decentralization influences equity, efficiency and resilience through three mechanisms—‘voting with feet’, ‘close to ground’ and ‘watching the watchers’; each enabled or constrained by a broad range of institutional, socio-economic and geographic context— see Figure 1 for a summary of the C-M-O configurations. At the core of these mechanisms is that decentralization creates multiple centres of governance. First are the multiple (i.e. national/central, state/provincial and district/local) governments—which may relate to one another vertically within a country. Second are the governments of different sub-national jurisdictions within each vertical level of government which may relate to one another horizontally. And third are the close-to-community or community-based collective governance arrangements—e.g. local health boards and community health committees—in each local sub-national jurisdiction which relate with each of the levels of government vertically or with one another horizontally. Notably, ‘voting with feet’ occurs horizontally between jurisdictions, but the extent to which it occurs and alters equity may depend on vertical relations—i.e. existence of equalization transfers, how the funds are allocated, and whether the funds are disbursed directly to target lower-level governments. When the redistributive effect of centralization is removed, health workers may ‘vote with their feet’ to better resourced jurisdictions, and patients may ‘vote with their feet’ to the informal sector or neighbouring jurisdictions, worsening inequity and inefficiencies.

Figure 1.

The context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations explaining how decentralization influences health system equity, efficiency and resilience.

Likewise, the other two mechanisms obtain horizontally and vertically. Governing ‘close to ground’ may alter equity as local level governments make decisions that are more in keeping with local realities, thus favouring pro-equity spending on prevention services; this is facilitated by the involvement of collective level governance actors (e.g. local health boards and community health committees) in decision-making. Governing ‘close to ground’ may also influence efficiency, but with the tension of the lack of economies of scale associated with governing at a small scale (i.e. close to ground). ‘Close to ground’ ensures health workers are employed and retained locally. But without centralized redistribution, poorer and rural jurisdictions are not able to employ and retain high-skilled workers. ‘Watching the watchers’ influence equity when different levels of governance (and actors within each level of governance) have the capacity and are enabled by law to watch and hold one another responsible for equity. ‘Watching the watchers’ influences efficiency when higher level governments holding lower-level governments accountable for efficient spending, including actors at the collective level of governance holding governments accountable for corrupt practices. ‘Watching the watchers’ also influence resilience because the existence of multiple centres of governance creates the robustness and the excess capacity that allow for different levels of governance to step in when one is weak or has failed.

The findings of this review are in keeping with the broad literature applying the decision space approach to the analysis of decentralization, (Bossert, 1998) which indicate that ‘wider decision space should be accompanied by adequate organizational capacities and appropriate accountability mechanisms’, and that ‘the role of context on system functionality… involves too many determinants and causal networks to define in any detail’ (Roman et al., 2017). We identified a plethora of institutions and institutional arrangements between and within levels of governance, and how they may impact on decentralization. But beyond the institutional capacity (i.e. capacity to govern) which have been discussed in previous reviews, we also identified how contextual circumstances interact with one another to determine the effects of decentralization reforms. Of note, however, is that the literature reviewed in this article is limited to the effects of decentralization at a governance and systems level, and the findings may not necessarily apply to the decentralization of specific services (e.g. immunization, on which there is an extensive literature) or decentralization of the delivery of specific programmes (e.g. national HIV or tuberculosis programmes). And while the ‘voting with feet’ and ‘watching the watchers’ mechanisms may have limited applicability to the decentralization of specific services, the ‘close to ground’ mechanism may be of value in explaining some of the effects of decentralization on the outcomes of service delivery.

Our findings can guide countries which are newly decentralized or going through decentralization reforms on strategies at both national and sub-national levels to maximize the potential benefit of decentralization. For example, although the collective level of governance does not feature in previous reviews on decentralization, we identified it as a major enabler of the ‘close to ground’ and ‘watching the watchers’ mechanisms. And we also identified a range of contextual factors that may limit this enabler. Our findings can also help minimize the risk that policymakers and programme implementers will overlook the need to ensure that the institutions are in place to ensure successful decentralization reforms, as reforms are often hampered by quick interventions without the slow process necessary to build the capacity of sub-national governments and community groups to generate resources, oversee service delivery, determine optimal size and the right mix of decentralization and centralization, while ensuring that the benefits of governing ‘close to ground’ does not limit the potential for economies of scale. Indeed, ‘for some public goods, the optimal club size is the entire country, for others it is a narrower jurisdiction; a good political structure will be able to integrate the different levels of collective decision-making’ Casella and Frey (1992, p. 643). In addition, sub-national jurisdictions require the capacity to balance quick and unified response to issues against flexibility for local levels to deal with local issues (Bazzoli et al., 2000).

While realist syntheses go beyond conventional systematic reviews by being more flexible in constructing C-M-O configurations, they are by design, not standardizable or reproducible—as they involve the judgement (and, potentially, bias) of individuals involved in the review. A limitation of this review is that, being a recent entrant in the health literature (Abimbola and Topp, 2018), none of the included studies explicitly assessed resilience as an outcome of decentralized governance. Resilience was only implicitly demonstrated in the ‘backup’ effect of the ‘watching the watchers’ mechanism. However, ‘voting with feet’ may, in theory, confer resilience as local jurisdictions compete, such that innovations that confer resilience are more likely to emerge and spread; and governing ‘close to ground’ may, in theory, confer resilience as the impact of shocks or stress are more likely to be contained because governance occur on a small scale. Another potential limitation is that, due to a lack of systematic reporting of context (Hales et al., 2016), we often relied on authors’ perception on what enabled or constrained the outcomes of decentralization, wherever located in an article. Future studies should adopt a systematic approach to reporting context. Further research should explore how to build institutional capacity to facilitate positive effects of decentralization, the links between the contextual factors and the mechanisms identified in this review; and the circumstances in which decentralization may work in different settings.

Conclusion

In summary, we reviewed the literature on health system decentralization and identified three mechanisms by which decentralization may influence equity, efficiency, and resilience from 25 high-, middle- and low-income countries: ‘voting with feet’ (reflecting how decentralization exacerbates or assuages the existing patterns of inequities in the distribution of people, resources and outcomes in a jurisdiction); ‘close to ground’ (reflecting how bringing governance close to the people allows for use of local initiative, information, feedback, input and control); and ‘watching the watchers’(reflecting the many mutual accountability relations between multiple centres of governance within a jurisdiction which are multiplied by decentralization, involving governments at different levels and also community-level entities). And we also identified the contextual factors that influence each of these mechanisms. Notably, by moving beyond the constant refrain that effects of decentralization on pre-determined quantitative outcomes are mixed, this review demonstrates that a comprehensive synthesis that considers mechanisms of change and their contextual determinants is possible. We present an extensive and comprehensive set of contextual factors which may be considered in efforts to maximize the positive effects and minimize any potential negative consequences of decentralization, whether as an intervention or a phenomenon.

Acknowledgements

This review was commissioned by the World Health Organization (WHO). During the completion of this work, Seye Abimbola was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) through an Overseas Early Career Fellowship (APP1139631). No additional external funding was received for this study. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication and do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the World Health Organization.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- Abimbola S. 2019. Beyond positive a priori bias: reframing community engagement in LMICs. Health Promotion International. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daz023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abimbola S, Negin J, Jan S, Martiniuk A.. 2014. Towards people-centred health systems: a multi-level framework for analysing primary health care governance in low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy and Planning 29(Suppl 2): ii29–ii39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abimbola S, Negin J, Martiniuk AL, Jan S.. 2017. Institutional analysis of health system governance. Health Policy and Planning 32: 1337–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abimbola S, Topp SM.. 2018. Adaptation with robustness: the case for clarity on the use of ‘resilience’ in health systems and global health. BMJ Global Health 3: e000758.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abimbola S, Ukwaja KN, Onyedum CC, Negin J, Jan S, Martiniuk AL.. 2015. Transaction costs of access to health care: implications of the care-seeking pathways of tuberculosis patients for health system governance in Nigeria. Global Public Health 10: 1060–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aligica PD, Tarko V.. 2014. Institutional resilience and economic systems: lessons from Elinor Ostrom’s work. Comparative Economic Studies 56: 52–76. [Google Scholar]

- Arrow KJ. 1963. Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical care. The American Economic Review 53: 941–73. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson S, Haran D.. 2004. Back to basics: Does decentralization improve health system performance? Evidence from Cear�n north-east Brazil. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 82: 822–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barasa EW, Cloete K, Gilson L.. 2017. From bouncing back, to nurturing emergence: reframing the concept of resilience in health systems strengthening. Health Policy and Planning 32: iii91–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzoli GJ, Chan B, Shortell SM, Aunno TD.. 2000. The financial performance of hospitals belonging to health networks and systems. Inquiry 252: 234–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossert T. 1998. Analyzing the decentralization of health systems in developing countries: decision space, innovation and performance. Social Science & Medicine 47: 1513–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossert TJ, Larranaga O, Giedion U, Arbelaez JJ, Bowser DM.. 2003. Decentralization and equity of resource allocation: evidence from Colombia and Chile. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 81: 95–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P, Gruskin S.. 2003. Defining equity in health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 57: 254–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkerhoff DW, Bossert TJ.. 2014. Health governance: principal-agent linkages and health system strengthening. Health Policy and Planning 29: 685–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan JM, Tullock G.. 1962. The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Casella A, Frey B.. 1992. Federalism and clubs: towards an economic theory of overlapping political jurisdictions. European Economic Review 36: 639–46. [Google Scholar]

- Casey K. 2018. Radical decentralization: does community-driven development work? Annual Review of Economics 10: 139–63. [Google Scholar]

- Coase RH. 1937. The nature of the firm. Economica 4: 386–405. [Google Scholar]

- Cobos Muñoz D, Merino Amador P, Monzon Llamas L, Martinez Hernandez D, Santos Sancho JM.. 2017. Decentralization of health systems in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. International Journal of Public Health 62: 219–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conyers D. 2007. Decentralisation and service delivery: lessons from Sub-Saharan Africa. IDS Bulletin 38: 18–32. [Google Scholar]

- Cremer J, Estache A, Seabright P.. 1996. Decentralizing public services: what can we learn from the theory of the firm? Revue D’Economie Politique 106: 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cueto M. 2004. The origins of primary health care and selective primary health care. American Journal of Public Health 94: 1864–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]