Abstract

Excessive Ca2+ entry during glutamate receptor overactivation (“excitotoxicity”) induces acute or delayed neuronal death. We report here that deficiency in bax exerted broad neuroprotection against excitotoxic injury and oxygen/glucose deprivation in mouse neocortical neuron cultures and reduced infarct size, necrotic injury, and cerebral edema formation after middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice. Neuronal Ca2+ and mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) analysis during excitotoxic injury revealed that bax-deficient neurons showed significantly reduced Ca2+ transients during the NMDA excitation period and did not exhibit the deregulation of Δψm that was observed in their wild-type (WT) counterparts. Reintroduction of bax or a bax mutant incapable of proapoptotic oligomerization equally restored neuronal Ca2+ dynamics during NMDA excitation, suggesting that Bax controlled Ca2+ signaling independently of its role in apoptosis execution. Quantitative confocal imaging of intracellular ATP or mitochondrial Ca2+ levels using FRET-based sensors indicated that the effects of bax deficiency on Ca2+ handling were not due to enhanced cellular bioenergetics or increased Ca2+ uptake into mitochondria. We also observed that mitochondria isolated from WT or bax-deficient cells similarly underwent Ca2+-induced permeability transition. However, when Ca2+ uptake into the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum was blocked with the Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor thapsigargin, bax-deficient neurons showed strongly elevated cytosolic Ca2+ levels during NMDA excitation, suggesting that the ability of Bax to support dynamic ER Ca2+ handling is critical for cell death signaling during periods of neuronal overexcitation.

Keywords: Bcl-2 family protein, cerebral ischemia, endoplasmic reticulum, excitotoxicity, mitochondria, NMDA

Introduction

Overactivation of glutamate receptors (“excitotoxicity') has been implicated in stroke, traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Foyouzi-Youssefi et al., 2000, Mattson, 2007, Hardingham and Bading, 2010). Depending on duration and severity, excitotoxic injury induces necrotic or apoptotic cell death (Ankarcrona et al., 1995, Lankiewicz et al., 2000, Ward et al., 2007, D'Orsi et al., 2012), although other forms of cell death, such as necroptosis and parthanatos, have also been reported (Cregan et al., 2002, Yu et al., 2002, Wang et al., 2004b, Andrabi et al., 2008, Yuan and Kroemer, 2010). In all instances, neuronal Ca2+ overloading through extrasynaptic NMDA or Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors is the initial cell death trigger (Choi, 1987, Hardingham and Bading, 2010).

The proapoptotic bax gene is a key mediator of apoptotic cell death in neurons (Deckwerth et al., 1996, Vekrellis et al., 1997, Cregan et al., 1999, Putcha et al., 1999). Bax is normally localized in the cytosol or loosely attached to the mitochondria. Upon a variety of apoptotic stimuli, Bax undergoes conformational changes, leading to its translocation, oligomerization, and insertion into the outer mitochondrial membrane (Youle and Strasser, 2008). Bax oligomerization initiates outer mitochondrial membrane permeabilization (MOMP) and promotes caspase-dependent or -independent apoptosis (Hsu et al., 1997, Goping et al., 1998, De Giorgi et al., 2002, Youle and Strasser, 2008, Galluzzi et al., 2009). Neurons deficient in bax have been shown to be protected from growth factor withdrawal-, denervation-, proteotoxic-, and oxidative stress-induced neuronal injury (Xiang et al., 1998, Li et al., 2004, Siu and Alway, 2006, Steckley et al., 2007). We and others have shown that deletion of bax is also protective against excitotoxic apoptosis (Chang et al., 2004, Sánchez-Gómez et al., 2011, D'Orsi et al., 2012). Although excitotoxic necrosis leads to an immediate loss of neuronal ion and energy homeostasis, excitotoxic apoptosis is characterized by an initial recovery of both, followed by mitochondrial cell death engagement (Ankarcrona et al., 1995, Bonfoco et al., 1995, Luetjens et al., 2000, Ward et al., 2007, D'Orsi et al., 2012). This mode of cell death is characterized by a release of apoptosis-inducing factor, activation of calpain and Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase, and initiation of predominantly caspase-independent cell death pathways (Lankiewicz et al., 2000, Cao et al., 2007, Norberg et al., 2008).

Interestingly, recent evidence suggests that Bcl-2 family proteins, apart from their role in regulating apoptosis, are vital for the regulation of mitochondrial function, bioenergetics, and Ca2+ handling (Pinton et al., 2000, Scorrano et al., 2003, Chen and Dickman, 2004, Wei et al., 2004, Johnson et al., 2005, Oakes et al., 2005, White et al., 2005, Pinton and Rizzuto, 2006, Sheridan et al., 2008). Indeed, it has been suggested that these activities may represent their “daytime” function (Kilbride and Prehn, 2013). Here, we provide evidence that the proapoptotic Bax protein plays a key role in the regulation of neuronal Ca2+ homeostasis and through this activity controls cell death pathways upstream and in addition to its role in the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Fetal bovine serum, horse serum, minimal essential medium (MEM), B27 supplemented neurobasal medium, tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM), Fluo-4 AM (acetoxymethyl), and Fura-2 AM were from Invitrogen. All other chemicals, including NMDA, MK-801, and thapsigargin, came in analytical grade purity from Sigma-Aldrich.

Gene-targeted mice

The generation and genotyping of bax−/− mice has been described previously (D'Orsi et al., 2012). Several pairs of heterozygous breeder pairs of bax-deficient mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory and maintained in-house. The genotype of bax−/− mice was confirmed by PCR, as described by The Jackson Laboratory. The bax−/− mice were originally generated on a mixed C57BL/6x129SV genetic background using 129SV-derived ES cells, but had been backcrossed for >12 generations onto the C57BL/6 background. As controls, WT mice were used for all experiments. DNA was extracted from tail snips using the High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche). Genotyping was performed using three specific primers: 5′GTTGACCAGAGTGGCGTAGG3′ (common), 5′GAGCTGATCAGAACCATCATG3′ (wild-type [WT] allele specific), and 5′CCGCTTCCATTGCTCAGCGG3′ (mutant allele specific). All animal work was performed with ethics approval and under licenses granted by the Irish Department of Health and Children. Procedures were reviewed and approved by the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland Research Ethics Committee.

Preparation of mouse neocortical neurons

Primary cultures of cortical neurons were prepared from embryonic gestation day 16–18 (E16-E18) (D'Orsi et al., 2012). To isolate the cortical neurons, hysterectomies of pregnant female mice were performed after euthanizing mice by cervical dislocation. The cerebral cortices were isolated from each embryo and pooled in a dissection medium on ice (PBS with 0.25% glucose, 0.3% BSA). The tissue was incubated with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA at 37°C for 15 min. After the incubation, the trypsinization was stopped by the addition of fresh plating medium (MEM) containing 5% fetal bovine serum, 5% horse serum, 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Pen/Strep), 0.5 mm l-glutamine, and 0.6% d-glucose. The neurons were then dissociated by gentle pipetting and, after centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 3 minutes, the medium containing trypsin was aspirated. Neocortical neurons were resuspended in plating medium, plated at 2 × 105 cells per cm2 on poly-d-lysine-coated plates (final concentration of 5 μg/ml), and then incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2. The plating medium was exchanged with 50% feeding medium (NBM-embryonic containing 100 U/ml Pen/Strep, 2% B27, and 0.5 mm l-glutamine), 50% plating medium with additional mitotic inhibitor cytosine arabinofuranoside (600 nm). Two days later, the medium was again exchanged for complete feeding medium. All experiments were performed on days in vitro (DIV) 8–11.

Cell lines

Human prostate cancer DU-145 cells, which lack Bax expression (Xu et al., 2006), and DU-145 Bax cells, which reexpress Bax (von Haefen et al., 2002), were cultured in DMEM (Lonza) with 4.5 g/L glucose, 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin, and 10% fetal bovine serum and incubated at 37°C in humidified atmosphere with 5% of CO2.

Cerebral ischemia–transient middle cerebral artery occlusion

Transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) was performed as described previously (Gröger et al., 2005). Briefly, bax-deficient (body weight = 24.4 ± 0.4 g) and WT (body weight = 26.6 ± 1.3 g) control mice were initially anesthetized with 5% isoflurane, 30% O2, and 65% N2O and maintained with 2% isoflurane, 33% O2, and 65% N2O for the duration of surgery. Body temperature was maintained at 36.8–37.4°C with a feedback-controlled heating pad (Heater Control Module; FHC). A flexible laser-Doppler probe (5001 Master; Perimed) was glued onto the exposed left parietal skull over the territory of the MCA for continuous monitoring of regional cerebral blood flow. Thereafter, the left common and external carotid arteries were exposed and ligated. The common carotid artery was incised and a silicone-coated 8-0 nylon monofilament was inserted into the internal carotid artery and advanced until the laser-Doppler signal indicated occlusion of the MCA using an operative microscope. Laser-Doppler flow during occlusion was 8.55 ± 0.84% and 9.75 ± 0.93% of baseline in WT and bax−/− mice, respectively, indicating ischemic blood flow conditions in this area in both mouse strains. Wounds were sutured and mice were incubated at 34°C and allowed to wake up. Sixty minutes after MCAO, mice were shortly reanesthetized and ischemia was terminated by the removal of the intraluminal silicon-coated suture.

Histological analysis of ischemic neuronal injury

For quantification of neurological deficit score and infarct area/volume, WT (n = 6) and bax−/− mice (n = 8) were killed 24 h after reperfusion. Brain samples were frozen on dry ice and stored in −20°C. Ten-micrometer coronal sections (n = 14) from each brain were cut with a CM1950 Cryostat (Leica Biosystems) and taken at 500 μm intervals. Sections were stained with cresyl violet/Nissl and infarct area was quantified using an image analysis system (Leica Application Suite V3). Lesion volume was calculated as described previously by Gröger et al. (2005). Data are expressed as percentage of contralateral hemisphere to correct for differences in brain size and brain edema. Mice subjected to tMCAO were evaluated for neurologic deficit on a 5-point scale after 24 h of reperfusion (0 = no deficit; 1 = forelimb weakness; 2 = circling to the affected side; 3 = loss of reflex; and 4 = no spontaneous motor activity; Plesnila et al., 2001). To determine the plasticity of the bilateral posterior communicating artery (PcomA) in WT and bax−/− mice, four mice of each genotype were perfused with ice-cold saline followed by cresyl violet solution. Next, the brains were removed with the circle of Willis intact and placed in 4% formalin overnight at 4°C before examination with ImageJ software. Pictures were taken at 40× magnification on a camera connected to a surgical microscope (Leica DFC29). Before analysis, the pictures were additionally 3× magnified and the diameter of the PcomAs was measured as a percentage of the basilar artery (BA) diameter (Kitagawa et al., 1998). Statistical analysis was performed using the Mann–Whitney rank-sum test. For evaluation of early ischemic cell death, additional WT (n = 4) and bax−/− mice (n = 4) as well as sham-operated WT controls that underwent surgery except for the insertion of the silicone-coated 8-0 nylon monofilament into the internal carotid artery (n = 3), were killed 6 h after termination of procedures. Brain samples were removed and 12 μm sections from each sample were collected at the level of dorsal hippocampus (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001). Measurement of cell death was assessed by Fluoro-Jade B (FJB; Millipore) staining as described previously (Engel et al., 2012). FJB is a polyanionic fluorescein derivitave that specifically stains degenerating neurons. Hippocampal FJB-positive neurons were the average of two adjacent sections for CA3 and CA1 for each genotype. Analysis of DNA damage was performed using a fluorescein-based terminal deoxynucleotidyl dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) technique, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega; Murphy et al., 2007).

Oxygen-glucose deprivation in mouse neocortical neurons

Cortical neurons from WT and bax−/− mice, cultured on 24-well plates, were rinsed in a prewarmed glucose-free medium and then transferred to the hypoxic chamber (COY Lab Products Inc.). The hypoxic chamber had an atmosphere comprising 1.5% O2, 5% CO2, and 85% N2, and the temperature was maintained at 35°C. Neurons were then incubated with oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) medium (bubbled with N2 for 1 h before use). The OGD medium consisted of the following (in mm): 2 CaCl2, 125 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 MgSO4, and 10 sucrose, pH 6.8. After 45 min of OGD, the medium was removed and the conditioned medium replaced. Thereafter, cells were placed in normoxic conditions (21% O2 and 5% CO2) and allowed to recover for 24 h. The following day, cortical neurons were stained with 1 μg/ml Hoechst 33258 (Sigma-Aldrich) and 5 μm propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich) and neuronal injury was assessed using an Eclipse TE 300 inverted microscope (Nikon) with 20 × 0.43 numerical aperture (NA) phase contrast objective using the appropriate filter set for Hoechst/propidium iodide (PI) and using a charge-coupled device camera (SPOT RT SE 6; Diagnostic Instruments). Control neurons were treated similarly but were not exposed to OGD. All experiments were performed at least three times with independent cultures and for each time point; images of nuclei were captured in three subfields containing ∼300–400 neurons each and repeated in triplicate. The number of PI-positive cells was expressed as a percentage of total cells in the field. Resultant images were processed using ImageJ.

Plasmids and transfection

Neocortical neurons (DIV 6) were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). For overexpression of Bax, cortical neurons were transfected with a vector expressing WT bax flanked by yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) (Luetjens et al., 2001, Düssmann et al., 2010). The bax-9294A plasmid was a gift from Dr. Xu Luo (Eppley Institute for Cancer Research, Omaha, Nebraska); it expresses a mutant form of bax that is unable to oligomerize and fused to GFP (George et al., 2007). Controls were transfected with a plasmid for enhanced GFP (pEGFP-N1; BD Bioscience Clontech). For mitochondrial and ER calcium experiments, neurons were transfected with a vector expressing the mitochondrial (mtcD2cpv) or the endoplasmic reticulum (ERD1cpv) cameleon FRET probes, respectively (kindly supplied by Roger Tsien and Tullio Pozzan; Palmer et al., 2006). They both consist of the Ca2+-binding protein calmodulin (CaM) fused together with the CaM-binding domain of myosin light chain kinase (M13). The resulting protein construct is flanked at the carboxyl and N termini by mutants of GFP, CFP, and YFP. Upon Ca2+ binding, the CaM wraps around the M13 domain, producing a conformational change of the entire molecule, which positions the two CFP and YFP fluorophores into close spatial proximity, resulting in an increase of FRET efficiency (Miyawaki et al., 1997, Rudolf et al., 2003). Cortical neurons were used for experiments 24 h after transfection. For cytosolic ATP measurements, cortical neurons were transfected with a vector expressing the genetically encoded FRET-based cytosolic ATP indicator (ATeam; AT1.03/pcDNA3.1, kindly supplied by Dr Hiroyuki Noji [Imamura et al., 2009]). The cytosolic ATP-sensitive FRET probe consists of variants of CFP (mseCFP) and YFP (cp173-mVenus) connected by the ε subunit of Bacillus subtilis FoF1-ATP synthase. Upon cytosolic ATP level changes, the ε subunit retracts the two fluorophores close to each other, which increases FRET efficiency (Imamura et al., 2009).

Western blotting and coimmunoprecipitation

Preparation of cell lysates and Western blotting was performed as described previously (Reimertz et al., 2003). The resulting blots were probed with a mouse monoclonal supernatant NR2A glutamate receptor antibody (clone N327/95; NeuroMab) diluted 1:10; a mouse monoclonal supernatant NR2B glutamate receptor antibody (clone N59/20; NeuroMab) diluted 1:10; a purified mouse monoclonal NR1 glutamate receptor antibody (clone N308/48; NeuroMab) diluted 1:10; a mouse monoclonal supernatant GluA2/GluR2 antibody (clone L21/32; NeuroMab) diluted 1:10; and a mouse monoclonal β-actin antibody (clone DM 1A; Sigma-Aldrich) diluted 1:5000. A goat polyclonal anti-IP3RII (C-20, sc-7278; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or a normal goat-IgG (sc-2028; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used for coimmunoprecipitation analyses and captured by Dynabeads Protein G (Novex Life Technologies) following the manufacturer's protocol. After Laemmli-buffer lysis and electrophoreses, a mouse monoclonal Bcl-2 antibody (5K140, sc-70411; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used for immunodetection. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies diluted 1:10,000 (Pierce) were detected using Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore) and imaged using a FujiFilm LAS-3000 imaging system.

Time-lapse live cell imaging

Intracellular calcium measurements with Fluo-4.

Primary neocortical neurons on Willco dishes were coloaded with the calcium dye Fluo-4 AM (3 μm) and TMRM (20 nm) for 30 min at 37°C (in the dark) in experimental buffer containing the following (in mm): 120 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 0.4 KH2PO4, 20 HEPES, 5 NaHCO3, 1.2 Na2SO4, 1.2 CaCl2, and 15 glucose, pH 7.4. The cells were washed and bathed in 2 ml of experimental buffer containing TMRM and a thin layer of mineral oil was added to prevent evaporation. Neurons were placed on the stage of a LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope equipped with a 63 × 1.4 NA oil-immersion objective and a thermostatically regulated chamber (Carl Zeiss). After 30 minutes of equilibration time, neurons were exposed to 100 μm NMDA for 5 min and glycine (10 μm) with MK-801 (5 μm) was added to block NMDA receptor activation as required (D'Orsi et al., 2012). TMRM was excited at 543 nm and the emission collected with a 560 nm long-pass filter; Fluo-4 was excited at 488 nm and the emission was collected through a 505–550 nm barrier filter. Images were captured every 30 s during NMDA excitation and every 5 min during the rest of the experiments.

Intracellular calcium measurements with Fura-2.

Fura-2 is a dual-excitation wavelength Ca2+ indicator that can passively diffuse across cell membranes where endogenous esterases cleave the AM group, trapping the dye inside the cells. Cortical neurons were coloaded with Fura-2 AM (6 μm) and TMRM (20 nm) for 30 min at 37°C (in the dark) in experimental buffer. The cells were rinsed and bathed in 2 ml of experimental buffer containing TMRM and mineral oil was added on top. Neurons were then placed on the stage of an Axiovert 200M motorized microscope equipped with a 40 × 1.3 NA oil-immersion objective and a thermostatically regulated chamber (Carl Zeiss). After a 5 min baseline, cortical neurons were exposed to NMDA-induced excitotoxic injury (100 μm/5 min NMDA). Images were captured every 30 s during baseline and NMDA excitation and every 2 min during the rest of the experiments. Once bound to Ca2+, Fura-2 exhibits an absorption shift that can be observed by alternating the excitation between 340 and 380 nm at a band width of 15 nm while monitoring the emission between 500 and 540 nm (Grynkiewicz et al., 1985). TMRM was excited at 540–585 nm and the emission collected at 602–650 nm, YFP and GFP were excited at 485–514 nm and 455–490 nm, and the emission was recorded at 526–557 nm and 500–540 nm, respectively. The sarcoendoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPases (SERCA) inhibitor thapsigargin (5 μm) was added to the medium 10 min after start of the timelapse recording.

Mitochondrial and ER calcium measurements with mtcD2cpv and ERD1cpv, respectively.

Neurons, transfected with the mtcD2cpv or the ERD1cpv calcium probe and loaded with TMRM (20 nm) in experimental buffer, were placed on the stage of an LSM 7.10 confocal microscope equipped with a 63 × 1.4 NA oil-immersion objective and a thermostatically regulated chamber set at 37°C (Carl Zeiss). After a baseline equilibration time, NMDA (100 μm/5 min) dissolved in experimental buffer was added to the medium. TMRM was excited at 561 nm and the emission was collected by a 575 nm long-pass filter. CFP was excited at 405 nm and emission was collected at 445–505 nm and 505–555 nm for FRET. YFP was excited directly using the 489 nm laser diode and detected with the same band-pass filter used for FRET. Images were captured every 1 min throughout these experiments. Thapsigargin (5 μm) was used and added to the medium on stage 10 min after equilibration time.

Single-cell cytosolic ATP measurements with ATeam.

Neurons, transfected with the FRET-based cytosolic ATP indicator ATeam and loaded with TMRM (20 nm) in experimental buffer, were placed on the stage of an LSM 5Live duoscan confocal microscope equipped with a 40 × 1.3 NA oil-immersion objective and a thermostatically regulated chamber set at 37°C (INDIMO 1080; Carl Zeiss). After a 10 min equilibration time, neurons were exposed to 100 μm NMDA for 5 min. TMRM was excited at 561 nm and the emission was collected by a 575 nm long-pass filter. CFP was excited at 405 nm and emission was collected at 445–505 (CFP) and 505–555 nm (FRET). YFP was excited directly using the 489 nm laser diode and detected with the same band-pass filter used for FRET. Images were captured every 1 min throughout these experiments.

Imaging of mPTP opening.

mPTP opening was examined by calcein release from mitochondria in DU-145 and DU-145 Bax human prostate cancer cells (von Haefen et al., 2002, Xu et al., 2006). Cells plated on small Willco dishes were first loaded with calcein-AM (1 μm) for 30 min in Krebs solution containing the following (in mm): 140 NaCl; 5.9 KCl; 1.2 MgCl2; 15 HEPES; 2.5 CaCl2, and 10 glucose, pH 7.4. After that, CoCl2 (1 mm) was added for 10 min to quench cytosol calcein and cells were then bathed in 150 μl of Krebs solution containing TMRM (20 nm) and covered by a thin layer of mineral oil. The cells were placed on the stage of a LSM 7.10 confocal microscope equipped with a 63 × 1.4 NA oil-immersion objective and thermostatically regulated chamber set at 37°C (Carl Zeiss). Calcein AM and cobalt enter the cell, where the AM groups are cleaved from calcein via nonspecific esterase activity in the cytosol and mitochondria. Cobalt cannot enter healthy mitochondria and quenches the cytosolic calcein signal. Upon opening of the mPTP, cobalt enters through the pore and subsequently quenches the mitochondrial calcein fluorescence. Calcein was excited at 488 nm and emission was collected through a 505–550 nm band-pass filter. TMRM was excited at 561 nm, and the emission was collected by a 575 nm long-pass filter. mPTP opening was indicated by a reduction in mitochondrial calcein signal, measured every minute, and expressed as SD of calcein fluorescence.

Isolation of functional mitochondria and measurement of swelling

Mitochondria were isolated from mouse liver or brain synaptosome following the methods of Frezza et al. (2007). Protein was measured using Bradford reagent (Sigma-Aldrich). Mitochondrial pellets were resuspended in experimental buffer containing 125 mm KCl, 20 mm HEPES, 2 mm KH2PO4, 1 μm EGTA, 4 mm MgCl2, 3 mm ATP, 5 mm malate, and 5 mm glutamate Chinopoulos et al., 2003) at a final concentration of 1 mg/ml and 100 μl was added to a 96-well flat-bottomed transparent plate. Absorbance at 540 nm was detected in each well at 30 s intervals in a BioTek Synergy HT microplate reader and CaCl2 (100 μmol/l) was used. Alamethicin (80 μg/ml) was then added to induce maximal swelling. All experiments were performed on at least three separate preparations to ensure reproducibility of results.

Imaging analysis

All microscope settings, including laser intensity and scan time, were kept constant for the whole set of experiments. Control experiments were also performed and showed that photo toxicity had a negligible impact. All images were processed and analyzed using MetaMorph Software version 7.5 (Universal Imaging) and the data were presented normalized to the baseline.

Statistical analysis

Data are given as means ± SEM. For statistical comparison, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test was used. When another statistical test was used, for example, the Mann–Whitney rank-sum test in Figure 1, B, E–G, this is stated in the figure legend. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

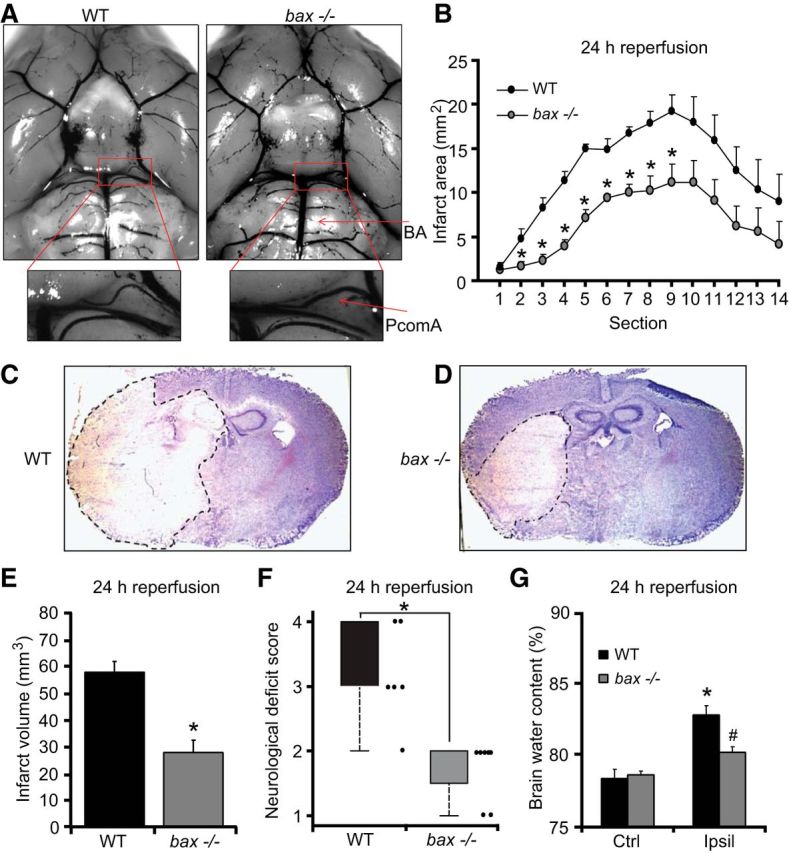

Figure 1.

bax deficiency protects against ischemic injury. A, Representative photomicrographs and magnified images of the circle of Willis showing the major blood vessel in WT and bax−/− mice perfused with ice-cold saline followed by cresyl violet solution (A). Arrows: BA, PcomA. There was no significant difference in the mean values of the PcomAs between genotypes (n = 4). B–G, Transient focal ischemia was induced for 60 min in WT (n = 6) and bax−/− (n = 8) mice by a silicon-coated nylon filament that was introduced into the internal carotid artery to occlude the MCA. Surgery was performed in deep isoflurane/N2O anesthesia with controlled ventilation and ischemia and reperfusion were verified by laser-Doppler flowmetry. Mice were killed 24 h after reperfusion and 10 μm coronal sections from each brain samples were collected and taken at 500 μm intervals. Infarct area (B) and infart volume (E) were calculated, as described previously by Gröger et al. (2005). Means ± SEM are shown. *p ≤ 0.05 compared with ischemia-exposed WT controls (Mann–Whitney rank-sum test). The photomicrographs show representative images of cresyl violet/Nissl-stained brain slices from WT and bax−/− mice 24 h after the onset of ischemia. The infarct area remained unstained and is highlighted by dashed lines (C, D). Neurological deficit score (F) was measured 24 h after tMCAo as described in the Materials and Methods session. *p ≤ 0.05 compared with WT controls (Mann–Whitney rank-sum test). Brain water content (G) was quantified and calculated as percentage of contralateral hemisphere to correct for differences in brain size and brain edema. *p ≤ 0.05 compared with contralateral WT controls; #p ≤ 0.05 compared with ipsilateral WT controls (Mann–Whitney rank-sum test).

Results

bax deficiency protects against neuronal cell death in vitro and in vivo

We recently demonstrated that bax-deficient primary mouse cortical neurons were resistant to neuronal injury induced by transient NMDA receptor overactivation (D'Orsi et al., 2012). Because glutamate toxicity is believed to contribute to ischemic and hypoxic neuronal injury, we were interested in determining whether bax deficiency could also reduce ischemic brain injury in vivo. For this purpose, two groups of mice, WT and bax deficient, were subjected to tMCAo. No significant difference in the plasticity of the PcomA was observed in bax-deficient versus WT control mice (n = 4 per genotype) by Mann–Whitney rank-sum test. The mean scores of PcomAs, measured in each hemisphere and calculated as a percentage of the BA diameter, were 21.64 ± 1.84% for bax-deficient mice and 25.92 ± 0.89% for WT mice (Fig. 1A).

WT and bax-deficient mice were subjected to 60 min of transient focal ischemia and reperfused for 24 h. bax deficiency led to a pronounced reduction in ischemic tissue damage. Protection in bax-deficient mice was observed in the lateral striatum and the adjacent cerebral cortex with a significant difference in the infarct size at various brain section levels (Fig. 1B–D). The edema-corrected infarct volume was reduced from 57 ± 4.9 mm3 in the WT mice to 28.5 ± 5.4 mm3 in the bax-deficient mice (Fig. 1E). bax-deficient mice subjected to tMCAo also had significantly reduced neurological deficit scores compared with their WT counterparts (Fig. 1F). The extent of cerebral edema in the bax-deficient animals was also diminished compared with the WT controls after ischemia/reperfusion injury (Fig. 1G).

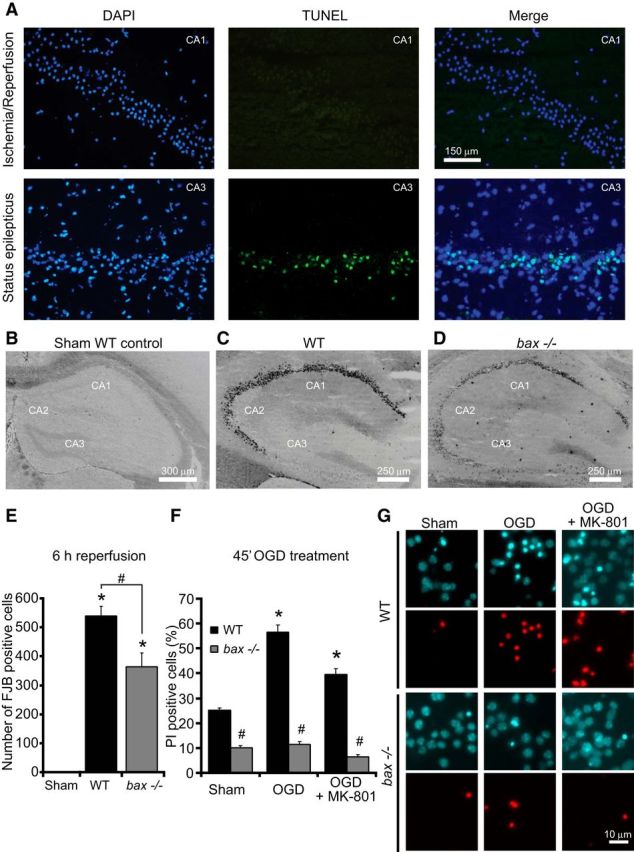

This surprising, pronounced protection against ischemic tissue injury and edema formation suggested that the effects of bax deficiency were not limited to a protection against mitochondrial apoptosis pathways. To address this, we assessed whether bax deficiency also protected against acute neuronal injury in this in vivo model. The hippocampus is a brain structure particularly vulnerable to ischemic injury. We therefore quantified neuronal injury in the CA1, CA2, and CA3 subfields of the hippocampus after 6 h of reperfusion using FJB, a marker of neuronal cell death (Wang et al., 2004c, Zheng et al., 2004). Acute cell death in the CA1 hippocampal subfield occurred in the absence of nuclear shrinkage and was negative for TUNEL staining (Fig. 2A, top). Hippocampal sections from mice subjected to status epilepticus for 24 h (Engel et al., 2010) showed strong TUNEL in the CA3 and served as positive controls (Fig. 2A, bottom). Interestingly, the number of FJB-positive cells was significantly reduced in the hippocampus of bax-deficient mice compared with their WT controls, suggesting that Bax may regulate TUNEL-negative, necrotic neuronal injury in vivo (Fig. 2C–E). FJB-positive cells were not notable in sham-operated control animals (Fig. 2B,E).

Figure 2.

bax deficiency protects against neuronal injury in the hippocampus and against OGD-induced injury in vitro. A, Representative images of sections derived from WT (n = 4) mice stained for TUNEL in the CA1 after ischemia/reperfusion for 6 h (top) and in the CA3 after status epilepticus (bottom). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 150 μm. B–E, WT (n = 4) and bax−/− (n = 4) mice were subjected to tMCAO for 60 min and additional (n = 3) WT mice were sham operated. Mice were killed 6 h after reperfusion and 12 μm sections from each brain samples were collected at the level of dorsal hippocampus. Neurodegeneration was assessed by FJB staining. Representative photomicrographs of sham-operated, negative control (B), WT (C), and bax−/− (D) hippocampal slices stained with FJB showing absence of neuronal injury after sham operation and typical injury after ischemia/reperfusion for 6 h. Scale bar, 250 μm. Hippocampal FJB-positive neurons were the average of two adjacent sections for the CA1, CA2, and CA3 for each genotype (E). Means ± SEM are shown. *p ≤ 0.05 compared with sham-operated negative control; #p ≤ 0.05 compared with ischemia-exposed WT controls (ANOVA, post hoc Tukey). F, G, Cortical neurons from bax−/− mice and WT controls were exposed to OGD for 45 min in the presence or the absence of MK-801 (5 μm) or sham conditions and allowed to recover for 24 h. Cell death was assessed by Hoechst 33258 (1 μg/ml) and PI (5 μm) staining and PI-positive nuclei were scored as dead neurons and expressed as a percentage of the total population (F). Three subfields containing 300–400 neurons each were captured and at least three wells were analyzed per time point. Means ± SEM are shown. *p ≤ 0.05 compared with sham controls; #p ≤ 0.05 compared with OGD-treated WT controls (ANOVA, post hoc Tukey). Representative images of PI- and Hoechst 33258-stained neurons are illustrated (G). Images were taken at 24 h post treatment. Scale bar, 10 μm.

We next turned to a model of OGD-induced neuronal injury in cortical neurons in which the effect of bax deficiency on different modes of cell death could be examined in more detail. Neurons were subjected to OGD for 45 min in the presence or absence of the NMDA receptor antagonist, MK-801, a treatment that “unmasks” neuronal apoptosis (Goldberg and Choi, 1993). Neurons were allowed to recover over a 24 h time period, after which neuronal injury was determined by PI uptake and Hoechst 33258 staining of nuclear chromatin (Fig. 2F,G). Quantification of Hoechst 33258- and PI-positive cells revealed that treatment with MK-801 significantly attenuated OGD-induced neuronal injury in WT neurons, but that the “apoptotic” component of OGD-induced neuronal injury evidenced by nuclear fragmentation and condensation was retained (Fig. 2G). bax deficiency further reduced OGD-induced injury in cultures treated with MK-801. OGD-induced injury in the absence of MK-801 was characterized by PI-positive cell death but occurred largely in the absence of nuclear fragmentation (Fig. 2G). Notably, bax deficiency also protected neurons against OGD-induced injury in the absence of MK-801 (Fig. 2F,G), again suggesting that the protective effects of bax deficiency on neuronal injury were broader than previously assumed.

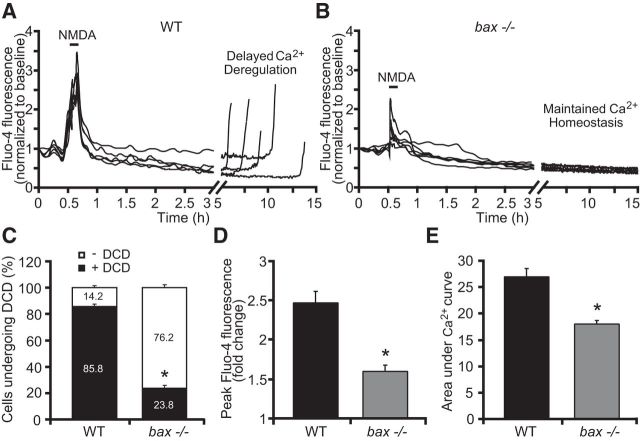

bax regulates intracellular calcium levels

Because Bcl-2 family proteins have previously been suggested to regulate Ca2+ homeostasis in non-neuronal cells (Scorrano et al., 2003, Chen et al., 2004b, Mathai et al., 2005, Oakes et al., 2005, Karch et al., 2013), we hypothesized that bax gene deletion may regulate neuronal Ca2+ dynamics, which could explain the broader cell-death-inhibiting activities observed. To address this complexity in more detail, we returned to the more controlled environment of excitotoxic injury (Ward et al., 2007, D'Orsi et al., 2012). Cortical neurons from WT and bax-deficient mice were exposed to 100 μm NMDA for 5 min, allowed to recover, and monitored over 24 h. Intracellular Ca2+ and mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) responses were recorded simultaneously by confocal imaging using the fluorescent calcium indicator Fluo-4 AM and the membrane-permeant cationic fluorescent probe TMRM. NMDA excitation resulted in an initial increase of intracellular Ca2+ that rapidly returned to baseline levels (Fig. 3A,B). After the insult, neurons derived from WT mice and undergoing excitotoxic apoptosis displayed delayed calcium deregulation (DCD) within 5–15 h of stimulation (Fig. 3A), whereas bax-deficient neurons maintained their Ca2+ homeostasis for longer periods (Fig. 3B) and underwent DCD at a much lower frequency than their WT counterparts (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, analysis of individual Ca2+ responses showed a significant reduction in cytosolic Ca2+ transients during NMDA (100 μm/5 min) exposure in the bax-deficient compared with the WT neurons, as evidenced by decreased extent of peak Ca2+ influx at the point of NMDA stimulation (Fig. 3D) and the smaller area under the Ca2+ curve during excitation (Fig. 3E). Because the Ca2+-indicator Fluo-4 AM is a single wavelength dye (Gee et al., 2000, Sato et al., 2007), we also performed these experiments using the ratiometric probe Fura-2 AM, allowing for quantitative determination of intracellular calcium concentration (Tsien et al., 1985, Barreto-Chang and Dolmetsch, 2009). When WT and bax-deficient cortical neurons were exposed to NMDA (100 μm/5 min), intracellular free calcium levels in absence of bax gene were significantly lower compared with their WT counterparts [peak Fura-2 ratio = 3.77 ± 0.129 and 1.54 ± 0.145; area under Ca2+ curve = 30.94 ± 0.082 and 14.96 ± 1.163 for WT (n = 43) and bax−/− (n = 21) neurons], confirming our previous data using Fluo-4 AM.

Figure 3.

bax deficiency protects against Ca2+ deregulation in response to NMDA. WT and bax−/− cortical neurons cultured separately on Willco dishes were preloaded with TMRM (20 nm) and Fluo-4 AM (3 μm) for 30 min at 37°C before being monitored by a confocal microscope (LSM 710). Neurons were exposed to 100 μm NMDA for 5 minutes, after which alterations in Δψm and intracellular Ca2+ were monitored in single cells over a 24 h period. A, B, Representative traces of NMDA-treated WT and bax−/− cortical neurons depicting the extent of peak Ca2+ influx at point of stimulation (100 μm/5 min NMDA) and DCD (A) or maintained calcium homeostasis hours after the initial excitotoxic stilmulus (B). C–E, Analysis of the frequency of neurons undergoing DCD between the genotypes (C), mean peak initial Fluo-4 AM fluorescence at NMDA exposure point (D), and mean area under Ca2+ curve during NMDA exposure (E) of WT (n = 71) and bax−/− (n = 52) cortical neurons are quantified. Data are means ± SEM from at least three independent experiments for each genotype. *p ≤ 0.05 compared with NMDA-treated WT controls (ANOVA, post hoc Tukey).

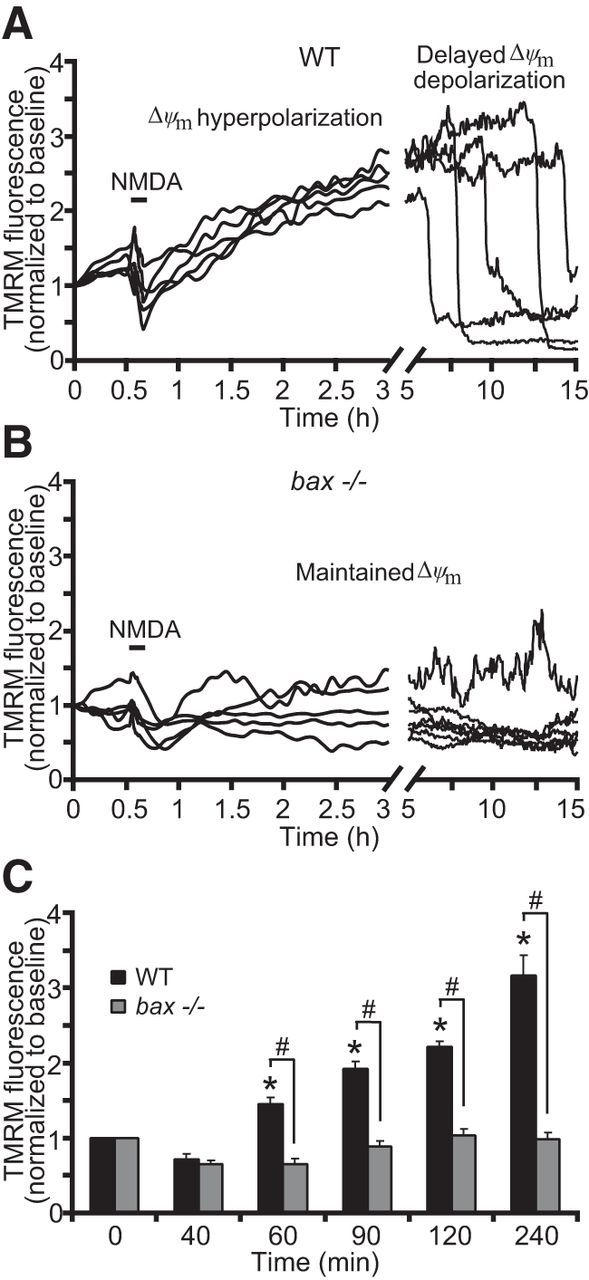

Analysis of Δψm kinetics using TMRM showed a significant increase in the TMRM fluorescence of the WT neurons within a 1–2 h time period after NMDA excitation, evidence of hyperpolarization of the Δψm (Fig. 4A,C), followed by a final depolarization of the Δψm. In contrast, although bax-deficient neurons showed similar initial mitochondrial membrane depolarization (reduction in TMRM fluorescence to 0.71 ± 0.07 and 0.64 ± 0.04 for WT and bax-deficient neurons, respectively), they did not display a considerable Δψm hyperpolarization, as evidenced by the constant basal levels of TMRM fluorescence observed after the initial NMDA exposure (Fig. 4B,C) and showed a significantly reduced incidence of late Δψm depolarization.

Figure 4.

bax deficiency normalizes mitochondrial function in response to NMDA. WT and bax−/− cortical neurons, preloaded with TMRM (20 nm) and Fluo-4AM (3 μm), were exposed to NMDA (100 μm/5 min NMDA) and monitored by a confocal microscope (LSM 710). A, B, Representative TMRM traces measuring alterations in mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) of NMDA-treated WT and bax−/− cortical neurons. WT neurons showed a delayed excitotoxic apoptosis in which neuronal mitochondria transiently recovered their energetics and a late Δψm depolarization occurred hours after the initial NMDA excitation (A). bax−/− neurons showed a complete and persistent recovered Δψm to basal levels even at later times after excitation (B). C, Average of TMRM fluorescence in WT (n = 71) and bax−/− (n = 52) neurons before and after NMDA excitation are represented. A significant increase in the whole-cell TMRM fluorescence of the WT neurons was identified within the 1–2 h period after NMDA excitation. In contrast, bax gene deletion did not produce a considerable hyperpolarization of the Δψm. Means ± SEM are shown from at least three independent experiments for each genotype. *p ≤ 0.05 compared with baseline WT control; #p ≤ 0.05 compared with WT controls (ANOVA, post hoc Tukey).

bax reintroduction recovers NMDA-induced Ca2+ transients

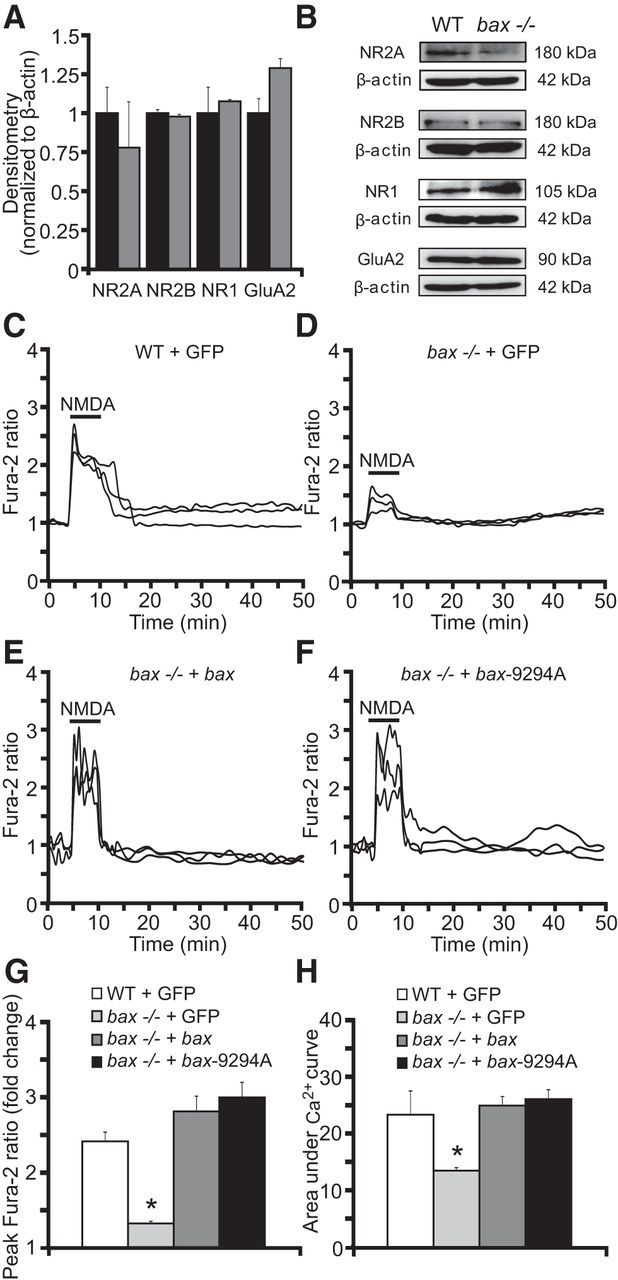

We next explored the possibility that the observed differences in cytosolic, NMDA-induced Ca2+ transients were due to altered glutamate receptor levels in the WT versus bax-deficient neuron cultures as a consequence of different development of cortical neurons before isolation or during cultivation. Using quantitative Western blotting, we noted no significant alteration in the protein levels of the extrasynaptic NMDA receptor NR2B, which largely mediates cytosolic Ca2+ transients and excitotoxic injury (Zhou and Baudry, 2006, Liu et al., 2007, Lau and Tymianski, 2010, Martel et al., 2012). Furthermore, no statistically signficant difference in NR1 and AMPA receptor GluA2 levels were observed between WT and bax-deficient neurons (Fig. 5A,B). We noted a tendency toward reduced levels of the synpatic, “neuroprotective” NMDA receptor subunit NR2A (Liu et al., 2007, Lau and Tymianski, 2010); however, this did not reach the level of statistical significance (Fig. 5A,B).

Figure 5.

bax reintroduction normalizes Ca2+ responses in bax-deficient neurons. A, B, Western blot and densitometric analysis comparing the levels of the NMDA receptors NR2A, NR2B, and NR1 and the AMPA receptor GluA2 in WT and bax−/− neurons. β-actin was used as loading control. Experiments were repeated three times with different preparations with similar results. Densitometric data are normalized to β-actin. Means ± SEM are shown from n = 3 independent experiments (p ≤ 0.05; ANOVA, post hoc Tukey). C–H, WT and bax−/− cortical neurons separately cultured on Willco dishes were transfected with a plasmid overexpressing bax fused to YFP, a plasmid expressing a mutant bax-9294A fused to GFP, which is unable to oligomerize at the MOM, or a plasmid expressing GFP alone as a control. Twenty-four hours after transfection, neurons were preloaded with TMRM (20 nm) and Fura-2 AM (6 μm) for 30 min at 37°C before being monitored with an Axiovert 200M motorized microscope. Neurons were exposed to 100 μm NMDA for 5 minutes, after which alterations in Δψm and intracellular Ca2+ were monitored in single cells over a 24 h period. Representative traces of NMDA-treated WT + GFP (A), bax−/− + GFP (B), bax−/− + bax (C), and bax−/− + bax-9294A (D) neurons depicting the extent of peak Ca2+ influx at the point of stimulation (100 μm/5 min NMDA). Mean peak Ca2+ influx at NMDA exposure time (E) and mean area under Ca2+ curve during NMDA exposure (F) between groups (n = 27 WT + GFP; n = 25 bax−/− + GFP; n = 26 bax−/− + bax; n = 29 bax−/− + bax-9294A) are quantified. Means ± SEM are shown. *p ≤ 0.05 compared with NMDA-treated WT controls (ANOVA, post hoc Tukey).

We next performed bax gene rescue experiments to control for potential differences in NMDA-induced Ca2+ entry. Cortical neurons were transfected with GFP, bax-YFP, or a mutant of bax (bax-9294A-GFP) that is unable to oligomerize at the mitochondrial outer membrane (George et al., 2007) and loaded with Fura-2AM. Again, we noted significantly reduced Ca2+ levels in bax-deficient cortical neurons transfected with GFP compared with their WT counterparts when exposed to NMDA (100 μm/5 min; Fig. 5C,D,G,H). Reintroduction of bax using either WT bax-YFP or the mutant bax-9294A-GFP equally restored neuronal Ca2+ levels to levels observed in WT cortical neurons transfected with GFP (Fig. 5C,E–H).

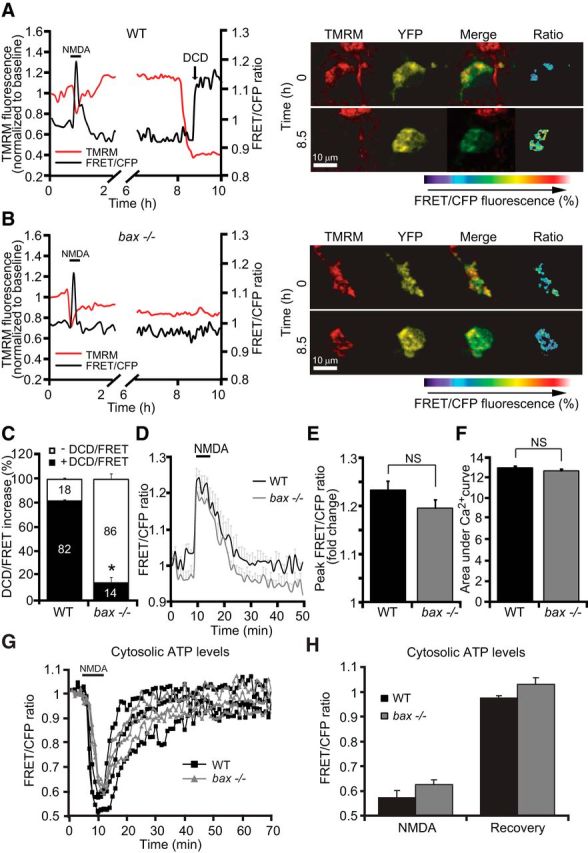

bax deficiency does not alter free mitochondrial matrix Ca2+ and does not increase cytosolic ATP levels

Previous reports have shown that mitochondria are capable of taking up significant amounts of cytosolic Ca2+ during excitotoxic injury (Sobecks et al., 1996, Stout et al., 1998, Yu et al., 2004). We therefore explored whether bax deficiency reduced cytosolic Ca2+ levels by facilitating mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. To determine whether bax-deficient neurons showed a greater mitochondrial free Ca2+ concentration compared with their WT control neurons, we used a mitochondrial Ca2+ sensor (mtcD2cpv) FRET probe (Palmer et al., 2006). As a consequence of Ca2+ binding, the mtcD2cpv FRET probe produces an increase in FRET efficiency, allowing for a detection of free matrix Ca2+. WT and bax-deficient cortical neurons were transfected with the mitochondrial Ca2+ sensor and exposed to 100 μm NMDA for 5 min, after which changes in FRET efficiency and Δψm were detected. During NMDA excitation, WT neurons showed an initial increase in free mitochondrial matrix Ca2+ that was associated with Δψm depolarization; however, this was followed by a rapid recovery to baseline levels after termination of the excitotoxic insult (Fig. 6A). bax-deficient neurons showed a similar, if not reduced increase in free mitochondrial Ca2+ during NMDA excitation (Fig. 6B,D). Analysis of Ca2+ traces of WT and bax-deficient neurons showed no significant difference in peak mitochondrial Ca2+ levels (Fig. 6E) or the area under the mitochondrial Ca2+ curve (Fig. 6F). In WT neurons that underwent delayed excitotoxic apoptosis, we also detected a substantial secondary matrix Ca2+ increase concurring with DCD (Fig. 6A, black arrow, C), whereas bax-deficient neurons showed protection against the secondary increase in free mitochondrial Ca2+ (Fig. 6B,C).

Figure 6.

bax deficiency does not influence free mitochondrial matrix Ca2+ levels and does not prevent ATP depletion during NMDA excitation. Cortical neurons derived from WT and bax−/− mice were transfected with either the mitochondrial Ca2+ sensor FRET probe (mtcD2cpv) and after 24 h mounted on the stage of a LSM 710 microscope or the ATP-sensitive (ATeam) FRET probe and after 24 h mounted on the stage of a LSM 5Live duoscan microscope. Fluorescent measurements were recorded for TMRM, FRET, CFP, and YFP by time-lapse confocal microscope. FRET probe imaging data are expressed as a ratio of FRET/CFP. TMRM was used as a Δψm indicator (nonquenched mode). A, B, WT and bax−/− cortical neurons transfected with the mitochondrial Ca2+ sensor FRET probe were then treated with 100 μm NMDA for 5 min and assayed over 24 h. Representative traces and corresponding images of NMDA-treated neurons depicting the extent of peak mitochondrial Ca2+ influx at point of stimulation (100 μm/5 min NMDA) and at later time points are illustrated. In neurons that showed a delayed excitotoxicity (A), we observed significant mitochondrial calcium accumulation (FRET probe activation) simultaneously with a delayed Δψm depolarization. In contrast, bax−/− neurons (B) that were tolerant to excitotoxic injury did not show a detectable FRET probe activation. C, Quantification of neurons showing DCD/FRET increase in WT (n = 32) and bax−/− (n = 40) neurons is shown. D, Means of three single cells representative traces ± SEM of WT and bax−/− mitochondrial Ca2+ kinetics before, during, and after NMDA excitation (100 μm/5 min NMDA) are shown. E, F, Mean peak FRET/CFP ratio (E) and mean area under mitochondrial Ca2+ curve (F) between the genotypes (n = 47 and 46 neurons for WT and bax−/−, respectively) during NMDA exposure are quantified. Data are means ± SEM from at least n = 3 independent experiments (p ≤ 0.05; ANOVA, post hoc Tukey). G, H, WT and bax−/− cortical neurons were separately transfected with the ATP-sensitive (ATeam) FRET probe, treated with 100 μm NMDA for 5 min, and assayed over 2–3 h. Time-lapse confocal microscopy experiments indicated no difference in cytosolic ATP levels between neurons derived from WT (n = 26) and bax−/− (n = 30) mice during the NMDA exposure and recovery time period (time = 50 min). Means ± SEM are shown from at least n = 3 independent experiments (p ≤ 0.05; ANOVA, post hoc Tukey).

Bax and other Bcl-2 family proteins have also been shown to be important for mitochondrial bioenergetics and quality control (Karbowski et al., 2002, Du et al., 2004, Yang et al., 2004, Karbowski et al., 2006). We next investigated whether bax-deficient neurons showed an enhanced bioenergetic capacity that may allow them to more efficiently extrude cytosolic Ca2+, for example, through plasma membrane Ca2+-dependent ATPases (PMCA), a key enzyme in the control of neuronal Ca2+ levels during excitiotoxic injury (Budd and Nicholls, 1996). To determine cytosolic ATP levels at the single-cell level, we used an ATP-sensitive FRET probe ATeam (Imamura et al., 2009) and monitored Δψm in parallel by time-lapse confocal microscopy in WT and bax-deficient neurons. We detected a rapid, comparable ATP depletion during NMDA stimulation (100 μm/5 min) followed by similarly restored ATP levels in both genotypes (recovery to baseline: FRET/CFP fluorescence to 0.97 ± 0.008 and 1.03 ± 0.022 for WT and bax−/− neurons; Fig. 6G,H), indicating the bax gene deletion did not affect cytosolic ATP dynamics. Interestingly, bax-deficient neurons displayed a significantly lower baseline cytosolic ATP level compared with their WT controls (100 ± 9.43% and 67.19 ± 10.31% for WT and bax−/− neurons, respectively; p ≤ 0.05 compared with NMDA-treated WT controls by ANOVA, post hoc Tukey), suggesting that bax-deficient neurons displayed, if anything, a decreased bioenergetic capacity.

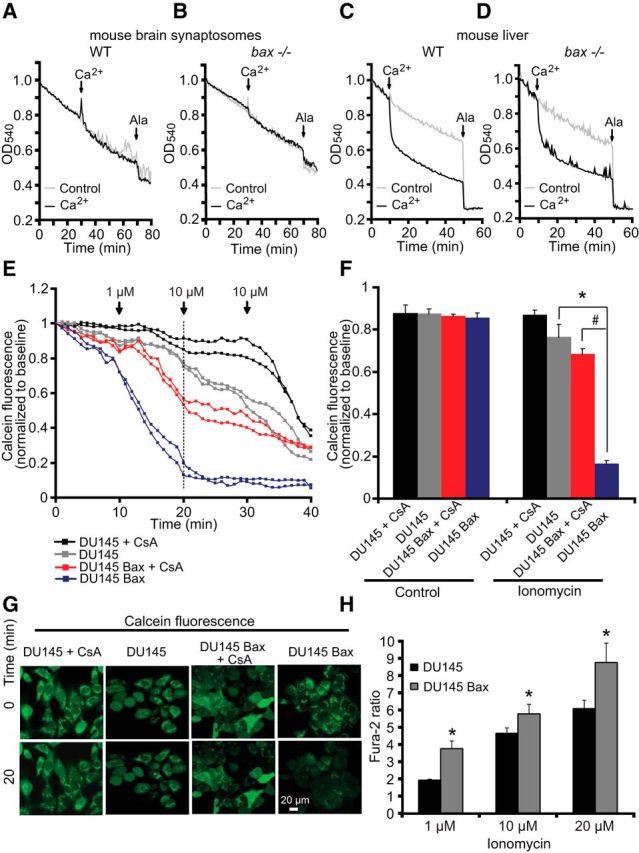

bax deficiency does not modulate Ca2+-induced permeability transition

We next tested the hypothesis that bax deficiency may prevent the formation of a Ca2+-induced mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) (Narita et al., 1998); that is, that Bax may be a physiologic activator of this pore (Antonsson et al., 1997, Vyssokikh et al., 2002). We examined a putative requirement for Bax in mPTP opening using isolated mitochondria from mouse brain synaptosomes and mouse liver. The effect of exposure of bax-proficient and bax-deficient mitochondria on Ca2+-induced mitochondrial swelling were detected by a rapid loss of absorbance at 540 nm. Alamethicin, a membrane-channel-forming peptide that induces mitochondrial swelling similar to mPTP (Andreyev et al., 1998, Andreyev and Fiskum, 1999), was used as a positive control to produce maximal swelling of mitochondria. As reported previously (An et al., 2004), Ca2+ addition to isolated mitochondria from WT (and bax-deficient) mouse brain synaptosomal preparations failed to induce significant mitochondrial swelling, with no differences detected between the two genotypes (Fig. 7A,B). In contrast, mitochondrial swelling in response to Ca2+ was more pronounced in mitochondria isolated from mouse liver, however, this was not modulated by bax deficiency (Fig. 7C,D). We also failed to detect a significant difference in mitochondrial swelling between WT and bax/bak double-deficient mitochondria isolated from human HCT 116 colon cancer cells (data not shown).

Figure 7.

bax deficiency does not modulate mPTP. A–D, Mitochondria (250 μg/ml) isolated from mouse brain synaptosomes (A, B) and liver (C, D) of WT or bax−/− mice, as described in the Materials and Methods, were preincubated at 30°C in experimental buffer in a 96-well plate at a final volume of 100 μl per well. Absorbance at 540 nm was detected at 30 s intervals and CaCl2 (100 μmol/l) was added where shown. Alamethicin (80 μg/ml) was added to induce maximal swelling. Results represent average traces from n = 3 experiments. E–G, Cobalt-quenching assay was performed in bax-deficient DU-145 and bax-reexpressing DU-145 Bax human prostate carcinoma cells. Mitochondrial calcein leakage was analyzed after sequential addition of ionomycin (1 and 10 μm) in the presence and absence of the mPTP inhibitor cyclosporine A (CsA; 10 μm) and representative traces are shown (E). Quantification of calcein fluorescence (SD in average pixel intensity) at the 20 min time point is illustrated (F). Representative images of calcein-CoCl2 staining of bax-deficient DU-145 and bax-reexpressing DU-145 Bax cells in the presence and the absence of ionomycin (t = 20 min) are shown (G). Scale bar, 20 μm. In the presence of ionomycin, bax-deficient DU-145 cells (gray) retained calcein fluorescent signals within the mitochondria, whereas significant calcein leakage was observed from the mitochondria of bax-reexpressing DU-145 cells (blue), suggesting that bax was required for mPTP. Ionomycin-induced calcein leakage was abolished in bax-deficient DU-145 cells (black) by CsA exposure and partially in bax-reexpressing DU-145 cells (red). A minimum of 30 cells from at least n = 3 independent experiments were analyzed per cell type/condition. *p < 0.05 compared with DU-145 cells; #p ≤ 0.05 compared with CsA-treated DU-145 Bax cells (ANOVA, post hoc Tukey). H, bax-deficient DU-145 (n = 70) and bax-reexpressing DU-145 (n = 111) prostate cancer cells were exposed to sequential addition of ionomycin (1, 10, and 20 μm) and Ca2+ responses using Fura-2 were recorded and quantified. Cytosolic Ca2+ overloading in response to ionomycin was significantly diminished in the bax-deficient DU-145 compared with bax-reexpressing DU-145 cells. *p < 0.05 compared with DU-145 cells (ANOVA, post hoc Tukey).

To analyze mPTP in intact cells, we also performed a calcein/Co2+-quenching assay (Su et al., 2004) in bax-deficient and bax-reexpressing DU-145 cells. The prostate carcinoma cell line DU-145 carries a frameshift mutation in the bax gene and thus does not express Bax (Xu et al., 2006). The calcein/Co2+ assay is based on the concept that mitochondrial calcein fluorescence is quenched by Co2+ after the irreversible opening of the mPTP. Cells were exposed to sequential addition of the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin (1 and 10 μm) both in the presence and absence of the mPTP inhibitor cyclosporine A (CsA; 10 μm; Fig. 7E–G). When 1 or 10 μm ionomycin was added to bax-deficient DU-145 cells, calcein fluorescent signals remained within mitochondria (Fig. 7E–G, gray), whereas significant calcein leakages from mitochondria was seen in bax-reexpressing DU-145 cells (Fig. 7E–G, blue). The mPTP inhibitor CsA abolished the ionomycin-induced calcein leakage in bax-deficient DU-145 cells (Fig. 7E–G, black), as well as bax-reexpressing DU-145 cells (Fig. 7E–G, red). Next, intracellular Ca2+ levels were determined in bax-deficient DU-145 and bax-reexpressing DU-145 cells using Fura-2 AM. bax deficiency also reduced ionomycin-induced Ca2+ transients compared with DU-145 cells in which bax was reintroduced (Fig. 7H). These data suggested that Bax modulates Ca2+ transients intracellularly (Fig. 5), but also demonstrated that effects of Bax on Ca2+-induced mPTP in intact cells are downstream of its effects on cytosolic Ca2+ levels.

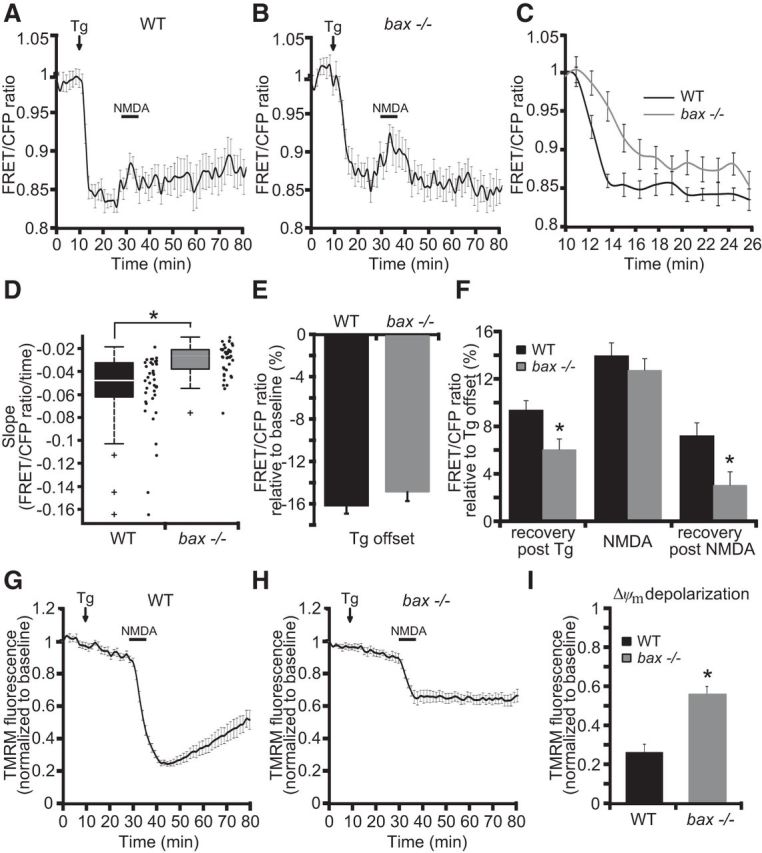

bax deficiency regulates ER Ca2+ handling

Previous reports, although partially contradictory, have suggested that Bcl-2 family proteins may be involved in regulating cell death by influencing ER calcium stores and signaling (Scorrano et al., 2003, Oakes et al., 2005, Rong et al., 2009, Chipuk et al., 2010). We next tested the hypothesis that bax-deficient neurons showed elevated ER Ca2+ levels in response to NMDA excitation or showed altered ER Ca2+ fluxes. To monitor free ER calcium in our single-cell system, we used the ER Ca2+ sensor (ERD1cpv) FRET probe (Palmer et al., 2006). Transfection of WT and bax-deficient cortical neurons with the FRET probe revealed that ER Ca2+ levels were not significantly altered during the NMDA exposure [mean peak FRET/CFP fluorescence 1.039 ± 0.008 and 1.051 ± 0.008 for WT (n = 22) and bax−/− (n = 33) neurons, respectively] or at baseline conditions [mean FRET/CFP fluorescence 1.04 AU ± 0.03 and 1.02 AU ± 0.01 for WT (n = 39) and bax−/− (n = 40) neurons, respectively].

The concentration of Ca2+ within the ER is suggested to highly exceed the concentration of Ca2+ within the cytosol ([Ca2+]ER ∼100–500 μm, [Ca2+]cyt ∼100 nm; Liu et al., 2004, Peirce and Chen, 2004). The possibility therefore remained that, in bax-deficient neurons, cytosolic Ca2+ levels were simply mobilized quicker into the ER than in WT neurons. To test this hypothesis, we inhibited ER Ca2+ uptake with the SERCA inhibitor thapsigargin. Thapsigargin (5 μm) was added to the medium of WT and bax-deficient cortical neurons prior (20 min) to NMDA stimulation and ER or cytosolic Ca2+ levels and Δψm using TMRM were monitored. SERCA inhibition produced a prompt decrease in ER Ca2+ in both genotypes followed by similar Ca2+ increases before, during, and after NMDA excitation (Fig. 8A,B,F). Detailed analysis of individual ER Ca2+ traces showed a significant reduction in the slope of the ER Ca2+ flux after thapsigargin treatment in the bax-deficient compared with the WT neurons (Δt = Tg offset time − Tg onset time: 3.78 min ± 0.29 in WT vs 7.36 min ± 0.38 in bax−/−; Fig. 8C,D). However, no significant difference was observed in ER Ca2+ levels at thapsigargin offset (Fig. 8E). Moreover, quantification of the individual Δψm responses showed that the combined presence of the SERCA inhibitor and bax gene deletion prevented a complete NMDA-induced depolarization of the Δψm (Fig. 8G–I).

Figure 8.

bax deficiency delays ER Ca2+ fluxes. A–I, Cortical neurons derived from WT and bax−/− mice were transfected with the ER Ca2+ sensor (ERD1cpv) FRET probe and after 24 h mounted on the stage of a LSM 710. Fluorescent measurements were recorded for TMRM, FRET, CFP, and YFP by time-lapse confocal microscope. FRET probe-imaging data are expressed as a ratio of FRET/CFP. TMRM (20 nm) was used as a Δψm indicator (nonquenched mode). Means of three single cells that are representative traces (±SEM) of WT and bax−/− depicting ER Ca2+ kinetics (A–C) and Δψm changes (G, H) after exposure to the SERCA inhibitor thapsigargin (Tg; 5 μm) and excitotoxic stimulus (100 μm/5 min NMDA) are shown. Quantification of slope (the change in FRET/CFP ratio over time in minutes; D), the extent of decrease in ER Ca2+ at point of Tg offset compared with basal levels (E), at times prior (recovery post-Tg), during (NMDA), and after (recovery post-NMDA) NMDA excitation compared with Tg offset levels in WT (n = 39) and bax−/− (n = 40) neurons are shown (F). Average of TMRM fluorescence in WT (n = 39) and bax−/− (n = 40) neurons after NMDA excitation are represented (I). In the presence of Tg, the Δψm depolarization point of the WT neurons resulted significantly reduced compared with bax−/− neurons. Means ± SEM are shown from at least three independent experiments for each genotype. *p ≤ 0.05 compared with WT control (ANOVA, post hoc Tukey).

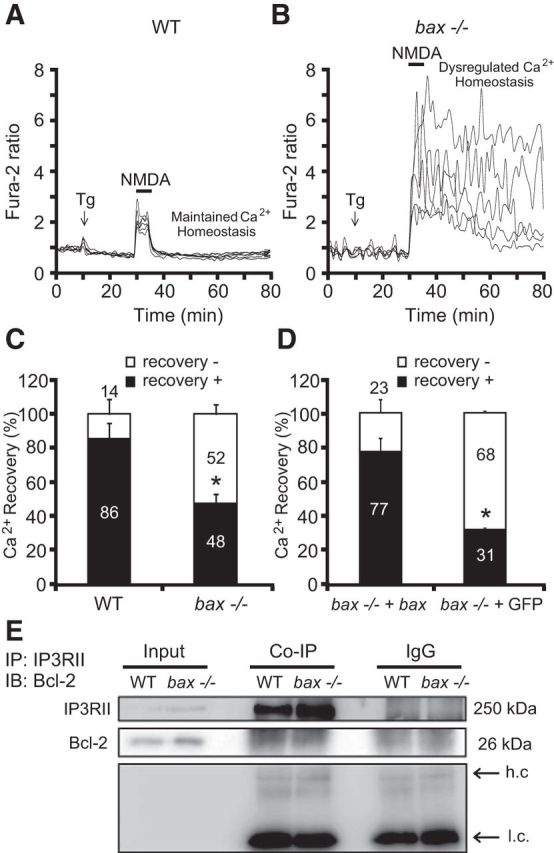

Inhibition of the SERCA also greatly increased intracellular Ca2+ levels in response to NMDA in bax-deficient cortical neurons, but not so in WT neurons (Fig. 9A,B). In response to the treatments, 14% of WT neurons did not display Ca2+ recovery to basal levels 30 min after NMDA excitation compared with 52% of bax-deficient neurons (Fig. 9C). Reintroduction of bax in bax-deficient cortical neurons using a mammalian expression vector for bax-YFP again normalized neuronal Ca2+ levels compared with bax-deficient neurons transfected with a plasmid expressing GFP alone (Fig. 9C,D).

Figure 9.

bax deficiency impairs ER Ca2+ handling during NMDA excitation. Cortical neurons derived from nontransfected WT or bax−/−, bax−/− either transfected with a plasmid overexpressing bax fused to YFP, or with a vector expressing GFP alone were separately cultured on Willco dishes. Twenty-four hours after transfection, neurons were preloaded with TMRM (20 nm) and Fura-2 AM (6 μm). Neurons were exposed to thapsigargin (Tg; 5 μm) before NMDA stimulation (100 μm/5 min), after which alterations in Δψm and intracellular Ca2+ were assayed in single cells over a 3 h period. A, B, Representative Ca2+ traces of Tg-NMDA-treated WT (A) and bax−/− (B) cortical neurons at points of Tg addition and NMDA excitation (100 μm/5 min NMDA). C, D, Ca2+ recovery to baseline levels after NMDA excitation (t = 60 min) was separately quantified in WT (n = 138) and bax−/− (n = 158) neurons (C) and bax−/− + bax (n = 42) and bax−/− + GFP (n = 35) neurons (D). Means ± SEM are shown. *p ≤ 0.05 compared with WT controls in C or compared with bax−/− + bax in D (ANOVA, post hoc Tukey). E, WT and bax−/− cortical neurons were lysed and immunoprecipitated using a goat polyclonal anti-IP3RII or a normal goat-IgG as an internal control and immunodetected using a mouse monoclonal anti-Bcl-2 and anti-IP3RII antibodies (h.c., heavy-chain; l.c., light chain). β-actin was used as loading control. Then, 200 μg of lysate were used for coimmunoprecipation and 20 μg of lysate were loaded in the gel as Input. Experiments were performed twice with different preparations and similar results.

Finally, we assessed whether bax deficiency modulated the interaction of Bcl-2 and IP3RII in cortical neurons as deficiency in bax may increase the ability of Bcl-2 to interact with IP3R. This interaction has been reported previously in B-cell lymphoma and in WEHI7.2 mouse lymphoid cells (Rong et al., 2009, Akl et al., 2013). A coimmunoprecipation assay of Bcl-2 and IP3RII in WT and bax-deficient neurons revealed no difference in Bcl-2/IP3RII interaction between the two genotypes (Fig. 9E). Comparable results were also obtained performing the reverse coimmunoprecipation (data not shown).

Together, these data suggested that Bax participates in the efficient flux of Ca2+ between cytosol and the ER and that inhibition of this activity may be associated with neuroprotection and reduced cytosolic Ca2+ overloading during excitotoxic injury.

Discussion

In the present study, we set out to explore the role of bax in the setting of Ca2+-induced neuronal cell death. Using models of ischemic and excitotoxic injury, we demonstrated that bax gene deletion provided broad neuroprotection against excitotoxic neuronal injury and OGD-mediated injury in mouse neocortical neurons in vitro and in cerebral ischemic injury in vivo. Our data suggest that this broad protection may be the result of Bax regulating Ca2+ homeostasis independently from its classical function in the apoptotic cell death machinery or a proposed involvement in mitochondrial PTP opening.

bax deletion is sufficient to confer protection against numerous apoptotic stimuli in cultured neurons in vitro, including neurotrophic factor deprivation and excitotoxic and DNA damage-induced neuronal apoptosis (Deckwerth et al., 1996, Miller et al., 1997, Deshmukh and Johnson, 1998, Xiang et al., 1998, Wang et al., 2004a), because Bak has been reported to be nonfunctional in mature neurons (Sun et al., 2001, Uo et al., 2005). Neuroprotective effects of bax deficiency have also been reported in cerebellar and cortical neurons in glutamate-induced excitotoxicity in vitro (Xiang et al., 1998), in a model of excitotoxic cell death of striatal neurons in vivo (Pérez-Navarro et al., 2005), and in models of hypoxic/ischemic neonatal injury in the hippocampus (Gibson et al., 2001), which involve predominantly apoptotic, caspase-mediated cell death pathways (Hu et al., 2000, Zhu et al., 2005, Han et al., 2014). Our study supports these previously reported protective activities, but also demonstrates that bax deficiency provides neuroprotection against TUNEL-negative, necrotic injury during ischemic stroke (Figs. 1, 2). Previous reports have also suggested a role of Bax in the regulation and formation of the mPTP (Kennedy et al., 1997, Narita et al., 1998). mPTP opening is generally associated with necrosis rather than apoptosis (Mao et al., 2001, Nakagawa et al., 2005) and has been shown to be involved in excitotoxicity (Li et al., 2009). In contrast to apoptotic MOMP, the mPTP is a channel of the inner mitochondrial membrane and leads to Δψm dissipation, cessation of oxidative phosphorylation and ATP synthesis, ROS production, mitochondrial swelling, and matrix Ca2+ release (Marshansky et al., 2001, Wen et al., 2001). We did not detect a significant role of Bax in regulating Ca2+-induced mPTP in isolated mitochondria from mouse liver and, in agreement with earlier studies (An et al., 2004), we failed to easily trigger Ca2+ induced mPTP in mitochondria isolated from neurons (Fig. 7). Rather, our data generated in DU-145 cells (that readily underwent Ca2+-induced mPTP) suggested that any effects of Bax on mPTP activation in intact cells may be secondary to the effects of Bax on cytosolic Ca2+ handling (Fig. 7).

Indeed, one of the key findings of our study was that Bax regulated neuronal Ca2+ homeostasis. bax-deficient neurons showed reduced Ca2+ transients during the period of NMDA excitation compared with WT neurons. Control experiments in WT neurons using a Smac-YFP fusion protein showed that MOM permeabilization did not occur during NMDA excitation (data not shown). Furthermore, reintroduction of bax using plasmids expressing either bax or a mutant form of bax that is unable to oligomerize at the MOM, both restored neuronal Ca2+ levels in bax-deficient neurons during NMDA excitation (Fig. 5). Collectively, these data indicated that the effect of Bax on neuronal Ca2+ homeostasis was independent of its role in promoting mitochondrial, Bcl-2-dependent apoptosis. It has also been demonstrated recently that the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-xL regulates mitochondrial bioenergetics, normalizing Δψm and subsequently increasing ATP production by decreasing ion leak through the F1F0 ATP synthase (Alavian et al., 2011, Chen et al., 2011). We therefore also tested the hypothesis that Bax may directly or indirectly control mitochondrial energetics. However, bax deficiency did not improve neuronal bioenergetics (Fig. 6). bax deletion slightly reduced basal cytosolic ATP levels. Given that Bax also regulates mitochondrial fission, it is possible that this is an indirect consequence of reduced mitochondrial quality control (Sheridan et al., 2008). Mitochondria have also been suggested to limit excitotoxic cell death by facilitating mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, a process that removes cytosolic Ca2+ and activates mitochondrial metabolism through stimulation of matrix Ca2+-dependent dehydrogenases, leading to increased ATP production required for the restoration of neuronal ion homeostasis (Rizzuto et al., 2012). Mitochondria also tightly control the position and propagation of cytosolic Ca2+ fluxes and its recycling toward the ER (Hajnóczky et al., 1999). Our investigation on free mitochondrial matrix and ER Ca2+ levels during NMDA excitation showed that bax deficiency did not affect overall free Ca2+ levels in either organelle (Figs. 6, 8). We detected, however, a significant increase in free mitochondrial matrix Ca2+ levels during the period of DCD, highlighting the engagement of mitochondria in late cell death signaling, as well as the ability to detect alterations in free mitochondrial matrix Ca2+ using the mtcD2cpv FRET probe (Fig. 6).

Organelle-targeted Ca2+ sensors exhibit a signficantly lower affinity to Ca2+ than the cytosolic Ca2+ indicators used in this study, so the use of cytosolic dyes may be a more sensitive approach to detect alterations in Ca2+ fluxes into and out of these organelles. Remarkably, by inhibiting Ca2+ uptake into the ER using the SERCA inhibitor thapsigargin, we demonstrated that Bax facilitated the dynamics of Ca2+ fluxes between cytosol and ER during NMDA excitation (Figs. 8, 9). The Bcl-2 family has been previously implicated in the regulation of the interaction between mitochondria and ER by influencing ER Ca2+ stores and signaling in non-neuronal cells (Chipuk et al., 2010). Using organelle-targeted aequorin probes or ER-targeted Ca2+ sensors, overexpression of Bcl-2 reduced the loading of intracellular Ca2+ stores, such as the ER and the Golgi apparatus, by increasing Ca2+ leakage in HEK-293 and HeLa cells (Foyouzi-Youssefi et al., 2000, Pinton et al., 2000). It was also suggested that the direct interaction between the BH4 domain of Bcl-2 and the IP3R is responsible for the inhibition of the IP3R activity and apoptosis, reducing resting ER Ca2+ levels and cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations in HeLa and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (Pinton et al., 2000, Rong et al., 2009). Moreover, Bax and Bak were suggested to regulate ER Ca2+ stores, possibly by inactivating the inhibitory functions of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL on the IP3R. Bcl-2 silencing or SERCA overexpression restored both ER Ca2+ and sensitivity of mouse embryonic fibroblasts to apoptotic challenge (Scorrano et al., 2003, Oakes et al., 2005). These findings are partially contradictory with other studies in which Bcl-2 did not show any effect on ER Ca2+ store, although an inhibition of ER Ca2+ release dynamics was proposed (Lam et al., 1994, Distelhorst et al., 1996, He et al., 1997, Wang et al., 2001, Chen et al., 2004a). Our data are consistent with the concept that Bcl-2 family proteins and, in particular, Bax may be involved in controlling ER Ca2+ stores by normalizing the proficient Ca2+ exchange between cytoplasm and ER. Alterations in Ca2+ fluxes between organelles and the cytosol may also be associated with a reduction in Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from the ER. Our study indicated that neurons lacking bax did not display a substantial Δψm hyperpolarization compared with their WT controls after NMDA excitation (Figs. 4, 8). It is possible that this is a conseqeuence of reduced Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from the ER, resulting in a decreased stimulation of the Krebs cycle.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that Bax regulates dynamic Ca2+ signaling between ER and cytosol in neurons and this role is independent of its classical role in the apoptotic cell death machinery. Our data also suggest that targeting Bax may exert broad protective effects against excitotoxic and ischemic neuronal injury and that inhibition of Bax function should be reconsidered as a therapeutic approach for the treatment of neuronal injury.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Science Foundation Ireland (Grants 13/IA/B1881, 08/IN.1/B1949, and 07/SK/B1243b to J.H.M.P. and Grant 08/IN.1/B2036 to N.P.); the National Biophotonics and Imaging Platform Ireland, funded by the Irish Government's Programme for Research in Third Level Institutions, Cycle 4 and Ireland's EU Structural Funds Programmes 2007–2013; and the Health Research Board (Grant HRA_POR/2011/41 to T.E. and D.C.H.). We thank Roger Y. Tsien (Department of Pharmacology, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California) and Tullio Pozzan (Institute of Neuroscience, Italian National Research Council, Padova, Italy) for providing the organelle-targeted FRET-based fluorescent calcium indicators (cameleons); Xu Luo (Eppley Institute for Cancer Research, Omaha, Nebraska) for the bax plasmids; Hiroyuki Noji (Institute of Scientific and Industrial Research, Osaka University, Japan) for the cytosolic ATP indicator (ATeam); and Ina Woods for technical support.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Akl H, Monaco G, La Rovere R, Welkenhuyzen K, Kiviluoto S, Vervliet T, Molgó J, Distelhorst CW, Missiaen L, Mikoshiba K, Parys JB, De Smedt H, Bultynck G. IP3R2 levels dictate the apoptotic sensitivity of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells to an IP3R-derived peptide targeting the BH4 domain of Bcl-2. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e632. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alavian KN, Li H, Collis L, Bonanni L, Zeng L, Sacchetti S, Lazrove E, Nabili P, Flaherty B, Graham M, Chen Y, Messerli SM, Mariggio MA, Rahner C, McNay E, Shore GC, Smith PJ, Hardwick JM, Jonas EA. Bcl-xL regulates metabolic efficiency of neurons through interaction with the mitochondrial F1FO ATP synthase. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1224–1233. doi: 10.1038/ncb2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An J, Chen Y, Huang Z. Critical upstream signals of cytochrome C release induced by a novel Bcl-2 inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19133–19140. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400295200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrabi SA, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Mitochondrial and nuclear cross talk in cell death: parthanatos. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1147:233–241. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreyev A, Fiskum G. Calcium induced release of mitochondrial cytochrome c by different mechanisms selective for brain versus liver. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:825–832. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreyev AY, Fahy B, Fiskum G. Cytochrome c release from brain mitochondria is independent of the mitochondrial permeability transition. FEBS Lett. 1998;439:373–376. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)01394-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankarcrona M, Dypbukt JM, Bonfoco E, Zhivotovsky B, Orrenius S, Lipton SA, Nicotera P. Glutamate-induced neuronal death: a succession of necrosis or apoptosis depending on mitochondrial function. Neuron. 1995;15:961–973. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90186-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonsson B, Conti F, Ciavatta A, Montessuit S, Lewis S, Martinou I, Bernasconi L, Bernard A, Mermod JJ, Mazzei G, Maundrell K, Gambale F, Sadoul R, Martinou JC. Inhibition of Bax channel-forming activity by Bcl-2. Science. 1997;277:370–372. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5324.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreto-Chang OL, Dolmetsch RE. Calcium imaging of cortical neurons using Fura-2 AM. J Vis Exp. 2009;23:1067. doi: 10.3791/1067. pii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfoco E, Krainc D, Ankarcrona M, Nicotera P, Lipton SA. Apoptosis and necrosis: two distinct events induced, respectively, by mild and intense insults with N-methyl-D-aspartate or nitric oxide/superoxide in cortical cell cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7162–7166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd SL, Nicholls DG. Mitochondria, calcium regulation, and acute glutamate excitotoxicity in cultured cerebellar granule cells. J Neurochem. 1996;67:2282–2291. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67062282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao G, Xing J, Xiao X, Liou AK, Gao Y, Yin XM, Clark RS, Graham SH, Chen J. Critical role of calpain I in mitochondrial release of apoptosis-inducing factor in ischemic neuronal injury. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9278–9293. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2826-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang GC, Hsu SL, Tsai JR, Wu WJ, Chen CY, Sheu GT. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation and Bcl-2 downregulation mediate apoptosis after gemcitabine treatment partly via a p53-independent pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;502:169–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Valencia I, Zhong F, McColl KS, Roderick HL, Bootman MD, Berridge MJ, Conway SJ, Holmes AB, Mignery GA, Velez P, Distelhorst CW. Bcl-2 functionally interacts with inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors to regulate calcium release from the ER in response to inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate. J Cell Biol. 2004a;166:193–203. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Dickman MB. Bcl-2 family members localize to tobacco chloroplasts and inhibit programmed cell death induced by chloroplast-targeted herbicides. J Exp Bot. 2004;55:2617–2623. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WL, Guo XF, Quan CS, Luan XY. [The expression and significance of bcl-2 and bax in each phase of the cell cycle in laryngeal carcinoma] Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Ke Za Zhi. 2004b;39:157–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YB, Aon MA, Hsu YT, Soane L, Teng X, McCaffery JM, Cheng WC, Qi B, Li H, Alavian KN, Dayhoff-Brannigan M, Zou S, Pineda FJ, O'Rourke B, Ko YH, Pedersen PL, Kaczmarek LK, Jonas EA, Hardwick JM. Bcl-xL regulates mitochondrial energetics by stabilizing the inner membrane potential. J Cell Biol. 2011;195:263–276. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinopoulos C, Starkov AA, Fiskum G. Cyclosporin A-insensitive permeability transition in brain mitochondria: inhibition by 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27382–27389. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303808200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipuk JE, Moldoveanu T, Llambi F, Parsons MJ, Green DR. The BCL-2 family reunion. Mol Cell. 2010;37:299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DW. Ionic dependence of glutamate neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 1987;7:369–379. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-02-00369.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cregan SP, MacLaurin JG, Craig CG, Robertson GS, Nicholson DW, Park DS, Slack RS. Bax-dependent caspase-3 activation is a key determinant in p53-induced apoptosis in neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7860–7869. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-18-07860.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cregan SP, Fortin A, MacLaurin JG, Callaghan SM, Cecconi F, Yu SW, Dawson TM, Dawson VL, Park DS, Kroemer G, Slack RS. Apoptosis-inducing factor is involved in the regulation of caspase-independent neuronal cell death. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:507–517. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deckwerth TL, Elliott JL, Knudson CM, Johnson EM, Jr, Snider WD, Korsmeyer SJ. BAX is required for neuronal death after trophic factor deprivation and during development. Neuron. 1996;17:401–411. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Giorgi F, Lartigue L, Bauer MK, Schubert A, Grimm S, Hanson GT, Remington SJ, Youle RJ, Ichas F. The permeability transition pore signals apoptosis by directing Bax translocation and multimerization. FASEB J. 2002;16:607–609. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0269fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshmukh M, Johnson EM., Jr Evidence of a novel event during neuronal death: development of competence-to-die in response to cytoplasmic cytochrome c. Neuron. 1998;21:695–705. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80587-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distelhorst CW, Lam M, McCormick TS. Bcl-2 inhibits hydrogen peroxide-induced ER Ca2+ pool depletion. Oncogene. 1996;12:2051–2055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Orsi B, Bonner H, Tuffy LP, Düssmann H, Woods I, Courtney MJ, Ward MW, Prehn JH. Calpains are downstream effectors of bax-dependent excitotoxic apoptosis. J Neurosci. 2012;32:1847–1858. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2345-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, Chen GG, Vlantis AC, Chan PK, Tsang RK, van Hasselt CA. Resistance to apoptosis of HPV 16-infected laryngeal cancer cells is associated with decreased Bak and increased Bcl-2 expression. Cancer Lett. 2004;205:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Düssmann H, Rehm M, Concannon CG, Anguissola S, Wurstle M, Kacmar S, Völler P, Huber HJ, Prehn JH. Single-cell quantification of Bax activation and mathematical modelling suggest pore formation on minimal mitochondrial Bax accumulation. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:278–290. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel T, Hatazaki S, Tanaka K, Prehn JH, Henshall DC. Deletion of Puma protects hippocampal neurons in a model of severe status epilepticus. Neuroscience. 2010;168:443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel T, Gomez-Villafuertes R, Tanaka K, Mesuret G, Sanz-Rodriguez A, Garcia-Huerta P, Miras-Portugal MT, Henshall DC, Diaz-Hernandez M. Seizure suppression and neuroprotection by targeting the purinergic P2X7 receptor during status epilepticus in mice. FASEB J. 2012;26:1616–1628. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-196089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foyouzi-Youssefi R, Arnaudeau S, Borner C, Kelley WL, Tschopp J, Lew DP, Demaurex N, Krause KH. Bcl-2 decreases the free Ca2+ concentration within the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5723–5728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.5723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frezza C, Cipolat S, Scorrano L. Organelle isolation: functional mitochondria from mouse liver, muscle and cultured fibroblasts. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:287–295. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi L, Blomgren K, Kroemer G. Mitochondrial membrane permeabilization in neuronal injury. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:481–494. doi: 10.1038/nrn2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee KR, Archer EA, Lapham LA, Leonard ME, Zhou ZL, Bingham J, Diwu Z. New ratiometric fluorescent calcium indicators with moderately attenuated binding affinities. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2000;10:1515–1518. doi: 10.1016/S0960-894X(00)00280-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]