Abstract

Objective

Inconsistent findings in regard to association between different concentrations of vitamin D, calcium or their combination and the risk of fracture have been reported during the past decade in community-dwelling older people. This study was designed to compare the fracture risk using different concentrations of vitamin D, calcium or their combination.

Design

A systematic review and network meta-analysis.

Data sources

Randomised controlled trials in PubMed, Cochrane library and Embase databases were systematically searched from the inception dates to 31 December 2017.

Outcomes

Total fracture was defined as the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes were hip fracture and vertebral fracture. Due to the consistency of the original studies, a consistency model was adopted.

Results

A total of 25 randomised controlled trials involving 43 510 participants fulfilled the inclusion criteria. There was no evidence that the risk of total fracture was reduced using different concentrations of vitamin D, calcium or their combination compared with placebo or no treatment. No significant associations were found between calcium, vitamin D, or combined calcium and vitamin D supplements and the incidence of hip or vertebral fractures.

Conclusions

The use of supplements that included calcium, vitamin D or both was not found to be better than placebo or no treatment in terms of risk of fractures among community-dwelling older adults. It means the routine use of these supplements in community-dwelling older people should be treated more carefully.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42017079624.

Keywords: calcium, vitamin D, fractures, network meta-analysis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This systematic review and meta-analysis combined the evidence from randomised controlled trials.

Our findings may not support the routine use of these supplements in community-dwelling older people.

This work does not necessarily preclude any benefit of vitamin D and calcium supplementation in older, frail individuals.

Potential missing data and meta-biases, heterogeneity, which may limit the quality of evidence.

Introduction

Clinical fractures of the elderly represent a worldwide public health problem that leads to illness and social burden. The patients with osteoporosis in the European Union were estimated to be 27.5 million in 2010, and 3.5 million new fragility fractures were sustained.1 In Asia, the average cost of osteoporotic fractures accounted for 18.95% of the countries’ 2014 gross domestic product/capita and increased annually.2–4 The overall prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in non-institutional population over the age of 50 years in the USA was estimated at 10.3% and 43.9%, respectively, which means that 10.2 million elderly people had osteoporosis and 43.4 million people had low bone mass in 2010.5 With the demographic trend of ageing and the predicted increase in life expectancy, the cost of fracture treatment is expected to rise.

Dietary allowances for calcium range from 700 to 1200 mg/day and vitamin D of 600–800 IU/day have long been recommended for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures in the elderly.6 7 The supplements of calcium and vitamin D are commonly taken to maintain bone health.

However, the previous randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses concerning vitamin D, calcium or their combination for fractures yielded different efficacy outcomes. For instance, two meta-analyses demonstrated calcium or vitamin D supplementation alone has a small benefit on bone mineral density, but no clinically important to prevent fractures,8 9 while an updated meta-analysis and a pooled analysis found calcium plus vitamin D supplementation can significantly reduce hip fractures by 30% and total fractures by 15%.10 11 Two RCTs reported that low dose of vitamin D supplementation (<800 IU/day) can reduce the incidence of falls12 and may prevent fractures without adverse effects,13 but other RCTs showed no significant reduction in the incidence of hip or other peripheral fractures,14 15 and its possible effects were seen only in patients with initial calcium insufficiency. Based on the evidence from meta-analysis, Bischoff-Ferrari et al 16 illustrated that high-dose vitamin D supplementation (≥800 IU/day) not only reduced the risk of falls and hip fractures but also prevented non-vertebral fractures. In contrast, a study reported annual high-dose oral vitamin D resulted in an increased risk of falls and fractures.17 On the other hand, low-dose calcium supplementation (<800 mg/day) effectively led to a sustained reduction in the rate of bone loss18 and turnover. Although it was also reported that the high dose of calcium (≥800 mg/day) was associated with a lower risk of clinical fractures.19 The high-dose calcium with high-dose vitamin D cannot prevent fractures according to the evidence from reported RCT,20 but a meta-analysis supported their combination can prevent bone loss and significantly reduce the risk of hip fractures and all osteoporotic fractures.21 Thus, it is challenging to conclude a dose-response relation between the intakes of vitamin D, calcium or their combination and the main outcomes in these heterogeneous literature.

Therefore, this study was designed to compare the fracture risk using different concentrations of vitamin D, calcium or their combination and comprehensively evaluate the optimal concentration to guide clinical practice and public prevention in community-dwelling older people.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

This review and meta-analysis is based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) extension statement for network meta-analysis. Our meta-analysis was registered prospectively in PROSPERO, and the Checklist PRISMA 2009 (online supplementary table 1) will be used to check our final reports.22

bmjopen-2018-024595supp012.pdf (46KB, pdf)

We restricted our meta-analysis to the inclusion criteria should meet following details: (1) RCTs; (2) interventions must be one of the following three: vitamin D only, calcium only, both vitamin D and calcium; (3) complete outcome data of fracture; (4) trials enrolling adults aged older than 50 years and living in their communities and (5) only studies that lasted more than a year. Exclusion criteria were (1) calcium or vitamin D combined with other therapies (eg, hormones and exercise); (2) trials in which vitamin D analogues (eg, calcitriol) or hydroxylated vitamin D were used; (3) trials in which dietary intake of calcium or vitamin D (eg, from milk) was evaluated and (4) patients suffering from illness or long-term use of certain drugs affecting the stability of the calcium metabolism, such as metabolic bone disease, bone tumour, treatment of steroids and so on.

Participants must be randomly assigned to two or more following groups: (1) high calcium (≥800 mg/day) only; (2) low calcium (<800 mg/day) only; (3) high vitamin D (≥800 IU/day) only; (4) low vitamin D (<800 IU/day) only; (5) high calcium (≥800 mg/day)+high vitamin D (≥800 IU/day); (6) high calcium+low vitamin D (<800 IU/day); (7) low calcium (<800 mg/day)+high vitamin D; (8) low calcium+low vitamin D and (9) placebo. The interventions should be compared with placebo.

Two authors (Z-HF and GZ) independently searched the electronic literature database of PubMed, Embase and Cochrane database on 31 December 2017 (detailed search strategies are reported in online supplementary table 2). Related articles and reference lists were searched to avoid original miss. The reference studies of previous systematic reviews, meta-analysis and included studies were manually searched to avoid initial miss. After two authors assessed the potentially eligible studies independently, any disagreement was discussed and resolved with the third independent author (QT).

bmjopen-2018-024595supp013.pdf (17.3KB, pdf)

Data collection and assessment of risk of bias

Two reviewers (Z-HS and XBL) independently extracted data, and the third reviewer (LT) checked the consistency between them. A standard data extracted form was used at this stage, including the authors, publishing date, country and participant characteristics; doses of calcium, vitamin D or their combination; dietary calcium intake; baseline serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration; and trial duration. For continuous outcomes, the mean, SD and participant number will be extracted. For dichotomous outcomes, we extracted the total numbers and the numbers of events of both groups. The data in other forms were recalculated when possible to enable pooled analysis.

We used the Cochrane risk of bias tool to assess risk bias of included studies. The tool has seven domains including random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other bias. The classification of the judgement for each domain was low risk of bias, high risk of bias or unclear risk of bias and two authors (Z-HF and GZ) independently evaluated the risk of studies.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

The data were extracted and input into the STATA software (V. 12.0; StataCorp) for network meta-analysis. And we generated network plots for each outcome to illustrate which interventions had been compared directly in the included studies. Network meta-analysis is an extension of standard meta-analysis to compare multiple treatments based on randomised controlled trial evidence, which forms a connected network of comparisons. Treatment effect estimates from network meta-analysis exploit both the direct comparisons within trials and the indirect comparisons across trials. To choose the random effects or fixed effects model, we either make a judgement about what is most likely to be appropriate based on the assumptions of the different models or conduct both fixed or random effects and compare which seems to fit the data better.23 Relative risk (RR) with 95% CIs was calculated for dichotomous outcomes, while weighted mean difference with 95% CIs for the continuous. Inconsistency refers to differences between direct and various indirect effect estimates for the same comparison. To assess inconsistency, we estimated the inconsistency factors (IFs) in closed loop based on the method described by Chaimani et al.24 The heterogeneity in each closed loop was estimated by using IF. If the 95% CIs of IF values are not truncated at zero, it suggests that the inconsistency among studies has statistical significance. We used the surface under the cumulative ranking probabilities to indicate which treatment was the best one. The funnel plot was used to identify possible publication bias if the number of studies was larger than 10.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, and no patients were involved in developing plans for design or implementation of the study. Furthermore, no patients were asked to advice on interpretation or writing up of results. Since this meta-analysis used aggregated data from previous trials, it is unable to disseminate the results of the research to study participants directly.

Result

Data retrieval

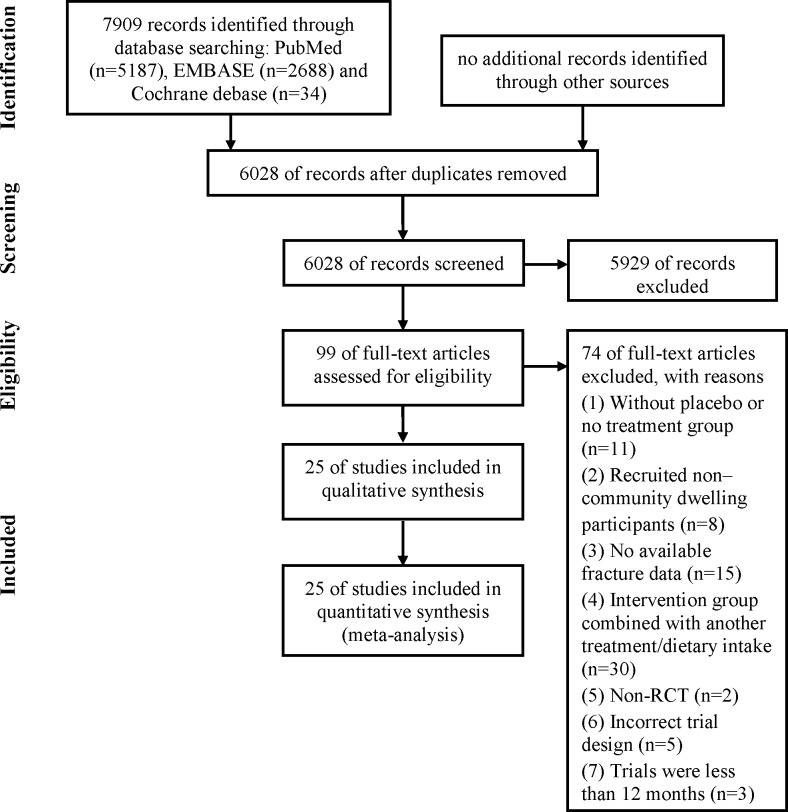

In summary, a total of 7909 potential records were initially identified through PubMed (5187), Embase (2688) and Cochrane (34) databases. Based on our review of the title and abstract, 99 full-text papers were reviewed, and 25 studies13 17 19 20 25–45 met inclusion criteria (figure 1).

Figure 1.

The selection of literature for included studies. RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Study and patient characteristics

The characteristics of all 25 included studies were summarised and shown in online supplementary table 3. And the detailed data of outcomes were collected in online supplementary table 4. The papers had similar distributions of sex, age, country and intervention, and all of them were community-dwelling older people. Hansson and Roos29 did not report the residential status of participants, although a previous meta-analysis classified this status as community. The trial by Hansson and Hansson was included, but a sensitivity analysis was performed that excluded that trial (online supplementary figure 1).

bmjopen-2018-024595supp014.pdf (70KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp015.pdf (34.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp001.pdf (525.6KB, pdf)

Online supplementary figure 2 showed the assessment of the risk of bias. All studies were randomised; 17 were double-blind, placebo-controlled trials; 13 trials described an adequate random sequence generation process; and 11 trials described the methods used for allocation concealment. No obvious publication bias was reported according to the online supplementary figures 3–5.

bmjopen-2018-024595supp002.pdf (202.1KB, pdf)

Inconsistence and heterogeneity check

The statistical inconsistency between direct and indirect comparisons was generally low according to inconsistency test because the CI values included zero (online supplementary figures 6–8). Therefore, we adopted a consistency model in all three groups. Meanwhile, we adopted the fixed effects models, and the heterogeneity parameter I2 values were 8.4%, 0% and 0%, respectively, which indicated no obvious heterogeneity was observed in all these results (online supplementary figures 9–11).

Primary outcome: total fracture

For estimating the vitamin D, calcium or their combination efficacy against total fractures, we looked at data from 24 965 individuals from 18 studies.13 17 19 20 25 26 28 30 31 33–35 37 39 40 43–45 Pooled estimates included 15 studies with one treatment, one study with two treatments, and two studies with three treatments.

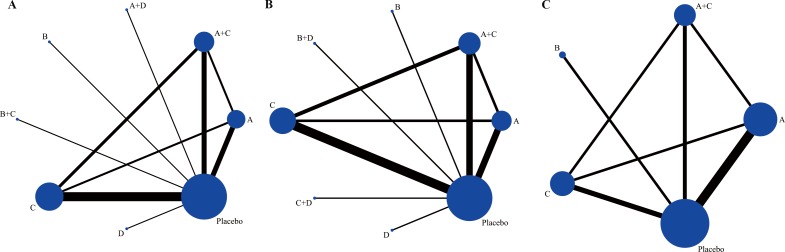

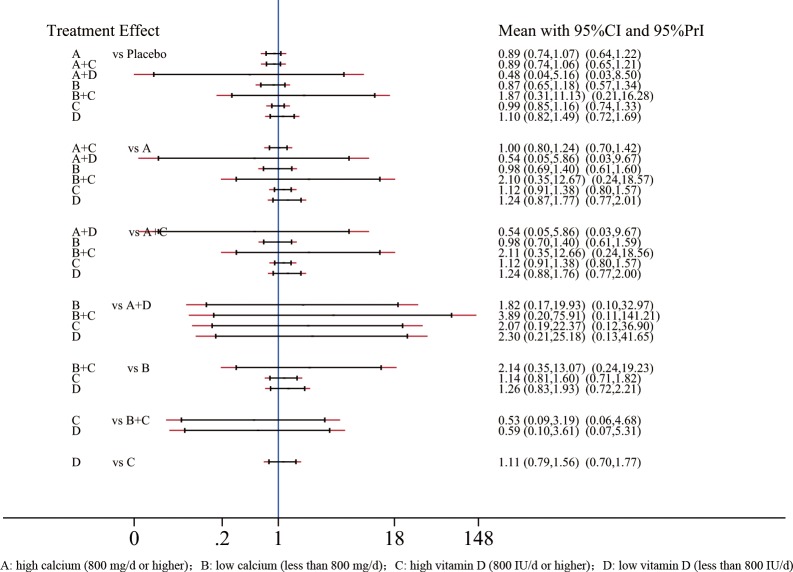

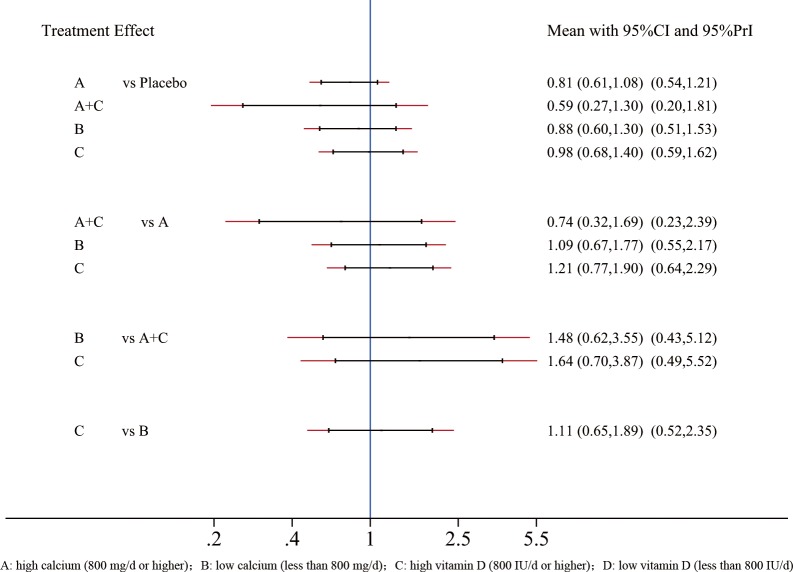

The network plot of comparisons on total fractures was shown in figure 2A. The forest plot for the network meta-analysis was shown in figure 3. The RR values and 95% CIs are summarised in figure 3. The direct and indirect comparisons indicated no differences among the vitamin D, calcium or their combination that remained in the main network. Neither do the statistical differences between interventions and placebo (p<0.05). So we did not continue to make ranking graph of distribution of probabilities on total fractures.

Figure 2.

(A) The network plot of comparisons on total fractures, (B) hip fractures and (C) vertebral fractures. A, high calcium (≥800 mg/day); B, low calcium (<800 mg/day); C, high vitamin D (≥800 IU/day); D, low vitamin D (<800 IU/day).

Figure 3.

The forest plot for the risk of total fractures. A, high calcium (≥800 mg/day); B, low calcium (<800 mg/day); C, high vitamin D (≥800 IU/day); D, low vitamin D (<800 IU/day). CI, confidence interval; PrI, predictive interval.

Secondary outcomes: hip fracture and vertebral fracture

A total of 41 845 individuals were included from 16 studies13 17 19 20 25–28 30 32 33 37 39 40 42 43 to evaluate the drug efficacy against hip fractures. Pooled estimates included 13 studies with one treatment, 1 study with two treatments and 2 studies with three treatments.

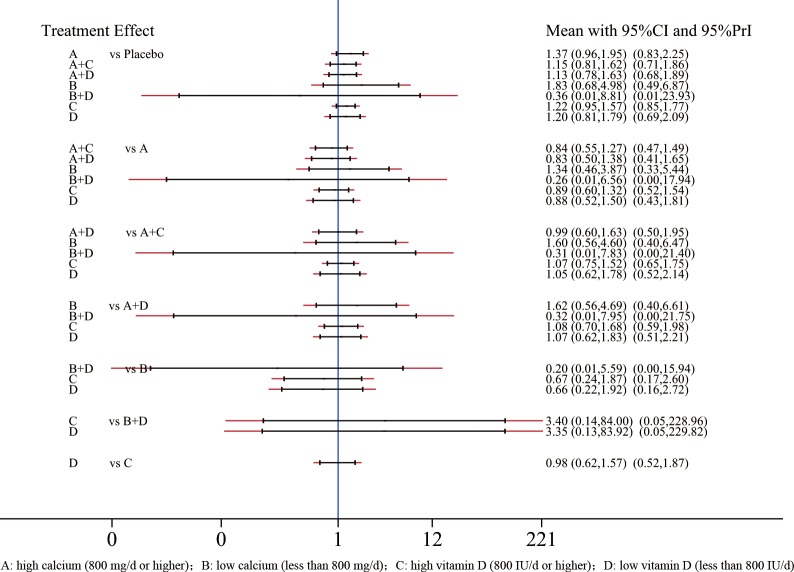

The network plot of comparisons on hip fractures was shown in figure 2B. The forest plot for the network meta-analysis was shown in figure 4. The RR values and 95% CIs are summarised in figure 4. The direct and indirect comparisons indicated no differences among the vitamin D, calcium or their combination that remained in the main network. Neither do the statistical differences between drug experimental groups and placebo (p<0.05). So we did not continue to make ranking graph of distribution of probabilities on total fractures.

Figure 4.

The forest plot for the risk of hip fractures. A, high calcium (≥800 mg/day); B, low calcium (<800 mg/day); C, high vitamin D (≥800 IU/day); D, low vitamin D (<800 IU/day).

A total of 17 612 individuals were collected from 12 studies13 17 19 20 25 28 29 36 38–41 involving vertebral fractures. Pooled estimates included 10 studies with one treatment and 2 studies with three treatments.

The network plot of comparisons on vertebral fractures was shown in figure 2C. The forest plot for the network meta-analysis was shown in figure 5. The RR values and 95% CIs are summarised in figure 5. The direct and indirect comparisons indicated no differences among the vitamin D, calcium or their combination that remained in the main network. Neither do the statistical differences between drug experimental groups and placebo (p<0.05). So we did not continue to make ranking graph of distribution of probabilities on total fractures. In a separate sensitivity analysis, we excluded Hansson and Roos’ study29 (online supplementary figure 1). However, there was still no significant association of vitamin D, calcium or their combination with total fracture.

Figure 5.

The forest plot for the risk of vertebral fractures. A, high calcium (≥800 mg/day); B, low calcium (<800 mg/day); C, high vitamin D (≥800 IU/day); D, low vitamin D (<800 IU/day).

Discussion

Vitamin D supplementation and calcium are suggested as interventions to treat and prevent fracture. We found the previous meta-analyses and RCTs are critically inconsistent in efficacy of different doses of vitamin D with calcium on fractures.

Results of this meta-analysis showed that calcium, calcium plus vitamin D and vitamin D supplementation alone were not significantly associated with a lower incidence of hip, vertebral or total fractures in community-dwelling older adults. Sensitivity analyses that excluded low-quality trials and studies that exclusively enrolled patients with particular medical conditions did not alter these results.

A meta-analysis conducted by Jia-Guo Zhao et al 46 showed that no significant difference was found in the incidence of hip or other fractures, which was similar to our result. However, the object of Zhao’s study was to investigate whether calcium, vitamin D or combined calcium and vitamin D supplement are associated with a lower fracture incidence, while our study was designed to evaluate the optimal concentration of them. Meanwhile, in Zhao’s meta-analysis, the participants of the included study reported by Massart47 were adult maintenance haemodialysis patients, which may result in the imbalance of calcium in the body. Patients on haemodialysis may also be receiving 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, which may affect their response to vitamin D supplementation. So we did not include that trial in our network meta-analysis. What’s more, we didn’t include studies that lasted less than a year because we thought this time frame was too short to see antifracture efficacy. And we suspected that a network meta-analysis might be a more suitable choice concerning all these different interventions mixed.

Bischoff-Ferrari et al 48 reported that high-dose vitamin D supplementation (≥800 IU/day) played an important role in the reduction of the risk of falls and hip fractures as well as prevented non-vertebral fractures in adults aged 65 years or older. However, their findings may have been influenced by the trial of Chapuy et al,49 which only enrolled participants living in an institution. What’s more, differences in conclusions of previous meta-analyses and the current meta-analysis were due to the recently published trials, which reported neutral or harmful associations of vitamin D supplementation and fracture incidence more and more. Study findings here indicated that vitamin D might result in a higher risk for hip fracture, but this conclusion did not reach statistical significance. This finding may be attributable to lack of statistical power in this meta-analysis.

Most recently, there was a meta-analysis published in the Lancet by Bolland et al,50 whose findings suggested that vitamin D supplementation does not prevent fractures or falls or has clinically meaningful effects on bone mineral density. Although it was similar to our study to some extent, they are really different. First, we only included community-dwelling older people. We found that some meta-analyses equated community-dwelling older people with those in nursing institution. The lack of exercise, dietary intake and exposure to sunlight made people in nursing institution turned more susceptible to the use of supplements including vitamin D, calcium or their combination. Although the studies involving participants living in nursing institution were only a small part, but it could change the whole outcomes and produce false-positive results. We found only Avenell’s study paid attention to this question when they conducted a subgroup analysis, but they did not discuss separately. Meanwhile, we only enrolled adults aged older than 50 years and trial duration more than 1 year to reduce the statistical heterogeneity in network meta-analysis. Furthermore, the current analyses included calcium supplementation, where the Bolland’s study focused on vitamin D.

However, possible limitations of this study protocol include potential missing data and meta-biases, heterogeneity, which may limit the quality of evidence. Some RCTs were of poor quality and, for example, used unclear allocation concealment. So we made a sensitivity analysis by excluding low-quality trials. Meanwhile, some study characteristics such as baseline serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations might be to contribute heterogeneity, so future analyses are still needed to explore this potential heterogeneity. What’s more, we combined bolus dosing by injection with oral supplements taken daily/monthly/yearly, which might have different effects on vitamin D status in the body. In addition, the report ignored the effect of treatment with vitamin D on plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and subtypes of fracture, such as pathologic fractures; this work does not necessarily preclude any benefit of vitamin D and calcium supplementation in older, frail individuals.

Conclusions

In this meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials, we found that the use of different concentrations of vitamin D, calcium or their combination in community-dwelling older adults was not associated with a lower risk of fractures. Our findings may not support the routine use of these supplements in community-dwelling older people.

bmjopen-2018-024595supp003.pdf (644.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp004.pdf (622.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp005.pdf (596.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp006.pdf (531.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp007.pdf (510.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp008.pdf (552.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp009.pdf (356.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp010.pdf (379.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp011.pdf (341KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

L-YS, W-FN and A-MW contributed equally.

Contributors: Z-CH and A-MW conceived the study. The search strategy was developed by LT and XL. Z-HF, GZ and QT completed electronic search, select publications and assess their eligibility. Z-HS and XL extracted information of the included studies after screening. J-WX checked the data entry for accuracy and completeness. Z-CH and LT gave advice for data analysis and presentation of study result. L-YS and C-MS contributed to the text revision. W-FN and A-MW supervised the overall conduct of the study. All the authors drafted and critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81501933, 81572214), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LY14H060008), Zhejiang Provincial Medical Technology Foundation of China (2018254309, 2015111494), Wenzhou leading talent innovative project (RX2016004) and Wenzhou Municipal Science and Technology Bureau (Y20170389). The funders had no role in the design, execution or writing of the study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Svedbom A, Hernlund E, Ivergård M, et al. . Osteoporosis in the European Union: a compendium of country-specific reports. Arch Osteoporos 2013;8:137 10.1007/s11657-013-0137-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mohd-Tahir N-A, Li S-C. Economic burden of osteoporosis-related hip fracture in Asia: a systematic review. Osteoporos Int 2017;28:2035–44. 10.1007/s00198-017-3985-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kim J, Lee E, Kim S, et al. . Economic burden of osteoporotic fracture of the elderly in South Korea: a national survey. Value Health Reg Issues 2016;9:36–41. 10.1016/j.vhri.2015.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Qu B, Ma Y, Yan M, et al. . The economic burden of fracture patients with osteoporosis in Western China. Osteoporos Int 2014;25:1853–60. 10.1007/s00198-014-2699-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, et al. . The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res 2014;29:2520–6. 10.1002/jbmr.2269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Consensus conference Osteoporosis. JAMA 1984;252:799–802. 10.1001/jama.1984.03350060043028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ross AC. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Public Health Nutr 2011;14:938–9. 10.1017/S1368980011000565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shea B, Wells G, Cranney A, et al. . Meta-Analyses of therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. VII. meta-analysis of calcium supplementation for the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Endocr Rev 2002;23:552–9. 10.1210/er.2001-7002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reid IR, Bolland MJ, Grey A. Effects of vitamin D supplements on bone mineral density: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2014;383:146–55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61647-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weaver CM, Alexander DD, Boushey CJ, et al. . Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and risk of fractures: an updated meta-analysis from the National osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporos Int 2016;27:367–76. 10.1007/s00198-015-3386-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. DIPART (Vitamin D Individual Patient Analysis of Randomized Trials) Group Patient level pooled analysis of 68 500 patients from seven major vitamin D fracture trials in US and Europe. BMJ 2010;340:b5463 10.1136/bmj.b5463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Flicker L, MacInnis RJ, Stein MS, et al. . Should older people in residential care receive vitamin D to prevent falls? results of a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1881–8. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00468.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Trivedi DP, Doll R, Khaw KT. Effect of four monthly oral vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) supplementation on fractures and mortality in men and women living in the community: randomised double blind controlled trial. BMJ 2003;326:469 10.1136/bmj.326.7387.469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lyons RA, Johansen A, Brophy S, et al. . Preventing fractures among older people living in institutional care: a pragmatic randomised double blind placebo controlled trial of vitamin D supplementation. Osteoporos Int 2007;18:811–8. 10.1007/s00198-006-0309-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Law M, Withers H, Morris J, et al. . Vitamin D supplementation and the prevention of fractures and falls: results of a randomised trial in elderly people in residential accommodation. Age Ageing 2006;35:482–6. 10.1093/ageing/afj080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Willett WC, Wong JB, et al. . Prevention of nonvertebral fractures with oral vitamin D and dose dependency: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:551–61. 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sanders KM, Stuart AL, Williamson EJ, et al. . Annual high-dose oral vitamin D and falls and fractures in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010;303:1815–22. 10.1001/jama.2010.594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nakamura K, Saito T, Kobayashi R, et al. . Effect of low-dose calcium supplements on bone loss in perimenopausal and postmenopausal Asian women: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res 2012;27:2264–70. 10.1002/jbmr.1676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Prince RL, Devine A, Dhaliwal SS, et al. . Effects of calcium supplementation on clinical fracture and bone structure: results of a 5-year, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in elderly women. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:869–75. 10.1001/archinte.166.8.869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Salovaara K, Tuppurainen M, Kärkkäinen M, et al. . Effect of vitamin D(3) and calcium on fracture risk in 65- to 71-year-old women: a population-based 3-year randomized, controlled trial--the OSTPRE-FPS. J Bone Miner Res 2010;25:1487–95. 10.1002/jbmr.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boonen S, Lips P, Bouillon R, et al. . Need for additional calcium to reduce the risk of hip fracture with vitamin D supplementation: evidence from a comparative metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:1415–23. 10.1210/jc.2006-1404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zintzaras E, Ioannidis JPA. Heterogeneity testing in meta-analysis of genome searches. Genet Epidemiol 2005;28:123–37. 10.1002/gepi.20048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chaimani A, Higgins JPT, Mavridis D, et al. . Graphical tools for network meta-analysis in STATA. PLoS One 2013;8:e76654 10.1371/journal.pone.0076654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Avenell A, Grant AM, McGee M, et al. . The effects of an open design on trial participant recruitment, compliance and retention--a randomized controlled trial comparison with a blinded, placebo-controlled design. Clin Trials 2004;1:490–8. 10.1191/1740774504cn053oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Baron JA, Beach M, Mandel JS, et al. . Calcium supplements for the prevention of colorectal adenomas. calcium polyp prevention Study Group. N Engl J Med 1999;340:101–7. 10.1056/NEJM199901143400204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dawson-Hughes B, Harris SS, Krall EA, et al. . Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on bone density in men and women 65 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 1997;337:670–6. 10.1056/NEJM199709043371003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Grant AM, Avenell A, Campbell MK, et al. . Oral vitamin D3 and calcium for secondary prevention of low-trauma fractures in elderly people (randomised evaluation of calcium or vitamin D, record): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2005;365:1621–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)63013-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hansson T, Roos B. The effect of fluoride and calcium on spinal bone mineral content: a controlled, prospective (3 years) study. Calcif Tissue Int 1987;40:315–7. 10.1007/BF02556692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Harwood RH, Sahota O, Gaynor K, et al. . A randomised, controlled comparison of different calcium and vitamin D supplementation regimens in elderly women after hip fracture: the Nottingham neck of femur (NONOF) study. Age Ageing 2004;33:45–51. 10.1093/ageing/afh002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hin H, Tomson J, Newman C, et al. . Optimum dose of vitamin D for disease prevention in older people: BEST-D trial of vitamin D in primary care. Osteoporos Int 2017;28:841–51. 10.1007/s00198-016-3833-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Gass M, et al. . Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of fractures. N Engl J Med 2006;354:669–83. 10.1056/NEJMoa055218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lips P, Graafmans WC, Ooms ME, et al. . Vitamin D supplementation and fracture incidence in elderly persons. A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 1996;124:400–6. 10.7326/0003-4819-124-4-199602150-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu B-X, Chen S-P, Li Y-D, et al. . The effect of the modified eighth section of Eight-Section Brocade on osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Medicine 2015;94:e991 10.1097/MD.0000000000000991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mitri J, Dawson-Hughes B, Hu FB, et al. . Effects of vitamin D and calcium supplementation on pancreatic β cell function, insulin sensitivity, and glycemia in adults at high risk of diabetes: the calcium and vitamin D for diabetes mellitus (CaDDM) randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94:486–94. 10.3945/ajcn.111.011684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Peacock M, Liu G, Carey M, et al. . Effect of calcium or 25OH vitamin D3 dietary supplementation on bone loss at the hip in men and women over the age of 60. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:3011–9. 10.1210/jc.85.9.3011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Porthouse J, Cockayne S, King C, et al. . Randomised controlled trial of calcium and supplementation with cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) for prevention of fractures in primary care. BMJ 2005;330 10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Recker RR, Hinders S, Davies KM, et al. . Correcting calcium nutritional deficiency prevents spine fractures in elderly women. J Bone Miner Res 1996;11:1961–6. 10.1002/jbmr.5650111218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Reid IR, Ames RW, Evans MC, et al. . Effect of calcium supplementation on bone loss in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med 1993;328:460–4. 10.1056/NEJM199302183280702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Reid IR, Mason B, Horne A, et al. . Randomized controlled trial of calcium in healthy older women. Am J Med 2006;119:777–85. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Riggs BL, O'Fallon WM, Muhs J, et al. . Long-Term effects of calcium supplementation on serum parathyroid hormone level, bone turnover, and bone loss in elderly women. J Bone Miner Res 1998;13:168–74. 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.2.168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Smith H, Anderson F, Raphael H, et al. . Effect of annual intramuscular vitamin D on fracture risk in elderly men and women--a population-based, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Rheumatology 2007;46:1852–7. 10.1093/rheumatology/kem240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Uusi-Rasi K, Patil R, Karinkanta S, et al. . Exercise and vitamin D in fall prevention among older women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:703–11. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Witham MD, Price RJG, Struthers AD, et al. . Cholecalciferol treatment to reduce blood pressure in older patients with isolated systolic hypertension: the VitDISH randomized controlled trial. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1672–9. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Xue Y, Hu Y, Wang O, et al. . Effects of enhanced exercise and combined vitamin D and calcium supplementation on muscle strength and fracture risk in postmenopausal Chinese women. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao 2017;39:345–51. 10.3881/j.issn.1000-503X.2017.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhao J-G, Zeng X-T, Wang J, et al. . Association between calcium or vitamin D supplementation and fracture incidence in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2017;318:2466–82. 10.1001/jama.2017.19344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Massart A, Debelle FD, Racapé J, et al. . Biochemical parameters after cholecalciferol repletion in hemodialysis: results from the VitaDial randomized trial. Am J Kidney Dis 2014;64:696–705. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Willett WC, Orav EJ, et al. . A pooled analysis of vitamin D dose requirements for fracture prevention. N Engl J Med 2012;367:40–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa1109617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chapuy MC, Arlot ME, Duboeuf F, et al. . Vitamin D3 and calcium to prevent hip fractures in elderly women. N Engl J Med 1992;327:1637–42. 10.1056/NEJM199212033272305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bolland MJ, Grey A, Avenell A. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on musculoskeletal health: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and trial sequential analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018;6:847–58. 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30265-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-024595supp012.pdf (46KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp013.pdf (17.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp014.pdf (70KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp015.pdf (34.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp001.pdf (525.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp002.pdf (202.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp003.pdf (644.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp004.pdf (622.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp005.pdf (596.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp006.pdf (531.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp007.pdf (510.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp008.pdf (552.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp009.pdf (356.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp010.pdf (379.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024595supp011.pdf (341KB, pdf)