Abstract

Objectives

This study sought to explore patients’ experiences of living with, and adapting to, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in the rural context. Specifically, our research question was ‘What are the barriers and facilitators to living with and adapting to COPD in rural Australia?’

Design

Qualitative, semi-structured interviews. Conversations were recorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed using thematic analysis following the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research guidelines.

Setting

Patients with COPD, admitted to a subregional hospital in Australia were invited to participate in interviews between October and November 2016.

Main outcome measures

Themes were identified that assisted with understanding of the barriers and facilitators to living with, and adapting to, COPD in the rural context.

Results

Four groups of themes emerged: internal facilitators (coping strategies; knowledge of when to seek help) and external facilitators (centrality of a known doctor; health team ‘going above and beyond’ and social supports) and internal/external barriers to COPD self-management (loss of identity, lack of access and clear communication, sociocultural challenges), which were moderated by feelings of inclusion or isolation in the rural community or ‘village’.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that community inclusion enhances patients’ ability to cope and ultimately self-manage COPD. This is facilitated by living in a supportive ‘village’ environment, and included a central, known doctor and a healthcare team willing to go ‘above and beyond’. Understanding, or supplementing, these social networks within the broader social structure may assist people to manage chronic disease, regardless of rural or metropolitan location.

Keywords: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, general practice, rural, self-management, qualitative

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study used qualitative methodology to provide an in-depth exploration of the patient experience.

The design followed the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research guidelines.

Thematic analysis allowed for synthesis focused on a phenomenon of interest and provided a transparent method that actively sought to remain close to the primary data and avoid overanalysis.

Transparency of method, the use of independent investigators and group discussion were used to promote the validity of findings, rigour and trustworthiness of the synthesis process.

This study was undertaken at a single site with a sample of people who had been hospitalised with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in the preceding 12 months. In line with a qualitative approach, this did provide important insight the experiences of this group, but may not reflect the experiences of people with COPD from different contexts.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic condition characterised by non-reversible airways obstruction, cough, phlegm and dyspnoea.1 COPD is the fourth leading cause of death globally.2 3 Social costs include significant disability, poor physical functioning, social isolation and caregiver burden.4 Disease trajectory involves progressive deterioration of lung function, decreasing quality of life and increasing acute exacerbation frequency and hospitalisation.5 6 Management of COPD is complex and patients often live with multiple comorbid conditions and may have poor mental health.7 Optimal care of COPD is founded on seamless, integrated, patient-centred care delivered by a multidisciplinary team with an emphasis on self-management.8 Engagement with self-management is associated with decreased hospital readmission9 and increased quality of life.10 However, research suggests that less than half of patients with COPD will achieve effective self-management, with younger patients and those living with others more able to address the complex disease management requirements.9 Early access to specialist care enhances support for coordination and self-management of COPD in primary care,11 with good relationships with health professionals facilitating navigation through the health system and a positive perception of quality of healthcare.12

In the rural context, workforce constraints restrict access to multidisciplinary, specialist providers, with care more likely to be delivered by smaller, more generalist teams. A qualitative study in New Zealand found that care pathways for COPD care in rural contexts were unclear and poorly coordinated.11 A recent study in the USA found that although access to diagnostic testing and specialists was restricted in rural clinics, quality and patterns of healthcare were similar for COPD between urban and rural clinics.13 In a rural Canadian study, long-term relationships with general practitioners (GPs), community support and personalised care helped to overcome issues of restricted specialist access in COPD care.14 In the Australian context, a study found that self-monitoring of symptoms and support from health professionals assisted patients to manage breathing difficulties and avoid emergency department presentations.15 Social inclusion and a sense of belonging in COPD has been shown to influence a person’s experience of living with COPD.16 17 The idea of a social connectedness through a supportive ‘village’ has been used to describe a diversity of social networks and supports in contexts such as maternal and child health18 and more recently in healthy ageing through the ‘aging-in-place’ movement.19 20 While the ‘village’ concept has not been used to describe supports in COPD, there is a clear recognition of the benefit of a sense of belonging and the importance of social support, from a variety of sources, in this context.16 17 What is not well understood is the experience of living with COPD and social connectedness in the rural context. Literature has pointed to a high degree of social capital within rural communities and inclusion of those who belong within social networks,21 with the converse for those who do not experience this inclusion.22 A review of qualitative research into chronic disease management in rural areas across North America, Europe, Australia and New Zealand found that the rural environment offered several positive aspects, namely personalised care, clinicians being better positioned to provide patient-centred care and increased community belonging which could counteract vulnerability.23

Rural studies focused on the experience of COPD from a patient’s perspective are uncommon. This study has sought to explore patient perspectives of living with and adapting to COPD in the rural Australian context. Understanding patient perspectives on current barriers and facilitators will inform rural workforce and care structure planning.

Methods

Design

Qualitative study using semi-structured interviews following the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research guidelines.24 Thematic analysis was chosen as it allowed for synthesis focused on a phenomenon of interest25; this being the experience of living with and adapting to COPD in the rural context. Thematic analysis is also a transparent method that actively seeks to remain close to the primary data and avoids overanalysis.26

Sample and setting

A convenience sample of patients admitted to a subregional Australian hospital (Northeast Health Wangaratta) with a primary diagnosis of COPD in the preceding 12 months (n=21 patients) were invited to participate in a health service survey, and indicated at the end of the survey if they were willing to be contacted by the investigators to participate in interviews to explore patient perspectives of living with and adapting to COPD in the rural context. This paper presents the data from those interviews. Data on disease severity was not collected, however all participants had required an acute admission for their COPD in the previous 12 months. In this setting, people with COPD are typically managed by GPs, with or without a generalist physician, and some are supported by community allied health services including physiotherapy, occupational therapy and social work in a pulmonary rehabilitation programme. Northeast Health Wangaratta is an approximately 200-bed public hospital that services a catchment of 90 000 people. Approximately seven general/consultant physicians work in the two larger townships in the catchment (Wangaratta and Benalla) along with 1.2 GPs per 1000 population, which is equivalent to the state average.27 28 It is common in chronic disease that patients work in a dyad with their caregivers, such as their marital partner, in managing their condition.29 In acknowledging this, the investigators allowed caregivers to be present during interviews, if the patient participant desired, and these caregivers were allowed to provide additional comments as explanation of the topics raised and discussed by the patient participant themselves. All caregiver participants were consented prior to discussion.

Data collection

Semi-structured questions were developed in consultation with experts in the field of chronic illness and community healthcare. The questions sought to explore patient experiences of care coordination and living with COPD in the rural context, and are listed as online supplementary appendix 1. Potential participants were sent an invitation letter by the hospital following discharge. Interviews were undertaken at a location chosen by the participant. The female interviewer (KG, PhD) had training in interviewing techniques and experience in chronic disease management and healthcare delivery research. The interviewer had no prior or ongoing relationship with the participants. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Names of people and pets were changed to increase anonymity of participants. No additional data are available.

bmjopen-2019-030953supp001.pdf (48.6KB, pdf)

Data analysis

Thematic synthesis was completed in three stages by two or more authors.26 30 31 All data were entered into NVivo11 QSR, followed by line-by-line free coding of primary data (stage 1) (two researchers). Free codes were then organised into descriptive themes (stage 2), with confirmation of themes through discussion (two researchers).26 30 31 Random selection of data extracts by a third independent researcher ensured trustworthiness of the data coding and themes, with disagreements resolved through discussion.26 30 31 Lastly, central emergent analytical themes were developed through group discussion (stage 3) to provide a broader understanding and meaning to the data within the context of patient’s experiences of care coordination and living with COPD in the rural Australian context (three researchers).26 30 31 Transparency of method, the use of independent investigators and group discussion were used to promote the validity of findings, rigour and trustworthiness of the synthesis process.26 30 31 Reflection was actively sought through discussion to minimise bias and come to agreement as to data saturation.32 All patients who indicated that they were interested in participating were interviewed. By the conclusion of the final interview no new themes had emerged. The final themes, with quotes for illustrative purposes are summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

Example of analysis process and illustrative quotes

| Category | Subcategory | Code | Condensed meaning unit | Meaning unit | |

| Internal facilitators | Coping strategies | Individual approaches to self-management | Matter of fact approach to COPD Acceptance of slowed pace Learning approaches to manage symptoms Working to retain activities of joy |

Making the best of things. There is no problem with her going on the train with the oxygen. It just slows you down. But I can control that… I go back to bed and I am alright the next morning. I could settle my breathing down. |

I didn’t get depressed about it (COPD diagnosis) or anything, no, I thought well you’ve got it, you’ve got to live with it. (P1) It just slows you down. You have to perform at the rate your heart will let you, and you have to perform at the rate your lungs will let you. So you get slower and slower, year-by-year. (P1) There is no problem with her going on the train with the oxygen. So that’s not a problem. It’s just a matter of putting her on the train and the oxygen will last for 8 hours. (P3) Quite often I get attacks—mild attacks—during the night if the temperature drops suddenly and it’s cold, and I haven’t had the heater on or something enough that can set me off. But I can control that quite often—I get up and make a cup of coffee and sit up in the chair and turn the heating on and then I go back to bed and I’m alright the next morning. (P14) …we did a lot of dancing and if I got really hot I’d have to go out of the hall into the fresh air, I felt like I was suffocating in the hall and I’d go out there and I could settle my breathing down by getting the fresh air outside. (P1) So he still goes out and enjoys that, but he doesn’t dance every dance like he used to. (P11) |

| Knowing when to seek help | Knowing when to seek help | Acting on warning signs Recognising changes |

Do not delay if you get unwell. You can feel yourself going down. |

Well self-management from what they’ve told me and what they’ve taught me is to live as comfortably as you can with what you’ve got—with your disease you’ve got and don’t buggerise around if you get crook (delay if you get sick). That’s it. (P15) You’re either on a high or you’re low. You can feel yourself going down and I have a boost of prednisolone. I used to have 25 for 3 days, 12 and a half for 3 days and then five for 7 days. (P1) |

|

| External facilitators | Centrality of a known doctor | Continuity, trust and connection | Central to support and coordination of care Providing access when needed |

Central position of support. Doctor integrated as part of community. You could not get an appointment with her because she was booked out all the time. Converse impact of lack of access. |

He’s (GP) my rock. (P9) Well if (doctor) were to leave and go somewhere else I don’t know what I’d do. (P3). ‘with different things she’d (GP) say ‘I’ll ring (doctor 1) and talk to her about it. So they worked hand in hand’. (P12) He happened to be one of my neighbours. He then asked ‘how is Rufus (my dog) going? How are you going? He even said “what’s your wife doing?” Your clothesline is chock-a-block every day’. Then he started talking, he says ‘What is it?’ I said, ‘look mate, I’m not happy, I want to go home’. (P7) He said to me, if ever I can’t get in, tell them I’ve got to see him, yes. (P9) My GP is really good. I say to her, it’s no good me making an appointment with you—I said this quite a while back—because I talk to the girls at the counter there and I’ve got to book in 3 months ahead. I said I’m not booking into you for 3 months ahead. I said I’ll ring you and let you know when I’m free. When I’m free….She puts me in every time. (P7) They only had the one female doctor—and she’d been there forever apparently, highly regarded. So I got an appointment with her and she did all these tests on me and checked blood tests and everything. Found out that I was okay as such, and—but I could only access her every 6 weeks at the least. You could never get her if you were sick. Just because you were sick you couldn’t get an appointment with her because she was booked out all the time. (P3) |

| Health team going above and beyond | Patients supported with inclusive access | Going the extra mile to accommodate and care for patients | Visiting and providing support. Giving patients their private number. Facilitating access. |

while I was in hospital (doctor 2) came in nearly every day and he didn’t have to (P13) (Doctor) came round to my place and sat down with my medications. She took them up to the chemist herself and got them put into a (Dosette-box). So I go to the chemist, now, and pick them up in a (Dosette Box). (P8) We had to see her (doctor 1) before we went on holiday and she’d give us her mobile number and ‘if anything happens, call me straight away’. (P11) Well (wife) went overseas. (Doctor) said well what are you doing? I decided not to come … I’m going to family. (Doctor) said okay, give the family my number. Here’s some extra medication, and this is the instructions if something happens. (P11) They let us (daughters of patient with COPD) sneak through the door around the other side, which brought us right in. Words cannot explain how great they were. We were so comfortable with all the staff that we could have asked them anything, every button they pressed on a machine, every tube they played with, they explained to us what they were doing. (P9) |

|

| Social support | Community supports assisting with independence Family support Peer support |

Community support independent living and watching over and taking care Family support with day to day and in recognising and managing symptoms Community through pulmonary rehabilitation |

The bus drivers are great, they lift me up because I have got oxygen. He fell over in the garden, one of them lifted him up. Family provide care and support—day to day and in time of need. Family assist with recognition of symptom changes. We look after one another and talk nicely and beautifully. |

When I go up the street on the bus, the bus drivers, they’re great. They will lift me up on the thing, because I’ve got the oxygen, I can lift up and that. At the picture theatre I find, and everywhere I go actually, I find them very good’. (P6) We get along very well with the maintenance fellows. (Patient with COPD) fell over in the garden out the side and one of the maintenance boys came up, lifted him up. (P5) The other night the power went off. So that’s when you really need somebody … you’ve got to go and get an oxygen bottle and set it up to breathe. (P6) Like at one stage what was about 12 of us in there with you (Mum, in Critical Care), (nurses) did not bat an eyelid. They (nurses) could see that the family support was what was keeping her going. (Daughter of P9) (She) helps me put my socks on, tells me to get out of bed. Tells me not to drink too much. General company. It’s really what it is. (She) will pick very quickly if I’m tiring. You never say stop. Just one more thing. I get that a lot. So I’m running on the Plimsoll line all the time. Just one more thing, then we’ll go home. (P11) Pulmonary rehabilitation also created an important community: Oh my goodness, (pulmonary rehabilitation) is amazing. See, number 1, you go there for exercises. Number 2, beautiful to sit there and talk to the next person. They all got similar things. We’re talking about how someone feels shit. Somebody’s better, somebody’s worse. We just listen to one another and then naturally crack up a joke or something which they said laughter is better than medicine. We look after one another and talk nicely and beautiful. (P7) |

|

| Internal barriers | Loss of identity | Impact of restriction on social worth and contribution Impact on mental health |

Loss of social role Mental health distress over unrelenting condition |

Forced by COPD into early retirement/loss of loved work role. Living a life of suffering. |

I was that wrecked (by having to give up work due to COPD). It was unbelievable. I don’t think that anybody would have loved their jobs as much I loved mine’. (P8) I thought, this is not worth it. What’s the use in living when you suffer like this even though my mind is clear and everything?’ (P7) Oh, my—if I could turn the clock back, every person that told me of the person and the people that were suffering from it, I would listen to the first person and shake the shit away, wouldn’t touch it again. (P7) |

| External barriers | Lack of access and clear communication | Lack of access and clear communication | High staff turnover Limited alternatives Lack of communication Having to repeatedly explain |

Do not even get to know the GPs, 18 months and they are gone. I could only access her every 6 weeks/I have clashed, they have rang the ambulance and said go to hospital. Don’t they read the files? The next doctor comes in, you have got to explain it again. |

You don’t even get to know (the GPs), 18 months and they’re gone. (P14) But the new one didn’t like (local town) so they left. He was replaced by an equally good one who didn’t like (local town) and left. (P3) They only had the one female doctor—and she’d been there forever apparently, highly regarded. … but I could only access her every 6 weeks at the least. You could never get her if you were sick. (P3) I’ve gone down to see a doctor, and I’ve clashed, or whatever. So they’ve rang an ambulance and said, go to hospital. (P8) I was in hospital 2 weeks ago and it wasn’t until a week after I got out with my GP that I actually found out what was the matter with me. (P14) There’s been a few times where I’ve gone to emergency. You explain the situation—like, you’re having trouble breathing as it is. They’re trying to say oh, how long have you been like this for? Have (they) got any medical records? You’ll see what’s the matter with me is! Do you know what I mean? … and then the next doctor comes in for the next shift. Then they say oh, what are you here for? Talk to each other instead of having to ask the patients. (P8) Then the next doctor comes in for the next shift. Then they say oh, what are you here for, and you’ve got to explain it. Don’t you read the files? Talk to each other, instead of having to ask the patients. (P8) |

| Sociocultural and economic challenges | Social isolation Financial hardship |

Impact of having newly moved to the region Making choices about costs associated with chronic disease |

I did not know anyone, you do not like to ask unless they offer. Community clinic my only avenue because I did not know what was available. Need somebody who knew me, need care straight away. It is just another cost. If we lived in housing commission you would be subsidised. |

I wasn’t (admitted to hospital), but I felt I should have been, because I wasn’t coping. I wasn’t well enough to do my own food preparation… Because I’m fairly new and I’m not a local, I didn’t know anyone so you don’t like to be asking someone to do those sorts of things (shopping, food preparation) unless they offer. (P14) The community clinic was the one that I accessed because they HAD TO take new patients. I mean they had more than they could cope with I think, but that was my only avenue at the time because I didn’t know what was available… I needed to access somebody who knew me- because asthma doesn’t go by the record sort of thing. You don’t know when—and when you get sick, you’re sick enough to need care straight away. (P14) Financial impact was raised several times, with participants having to balance treatments choices as well as resource choices to stay well: ‘We chose to increase the temperature of the house by a few degrees. It’s just another cost’. (P11) Requirements to replace stoves for oxygen therapy safety was another common added burden, and support for such measures perceived to be influenced by social circumstance: ‘If you were living in Housing Commission you would be subsidised, but because we were (self-funded retirees) … nothing’. (P6) |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GP, general practitioner; P, participant.

Patient and public involvement statement

This research involved patient interviews. Patients were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted to develop patient relevant outcomes or interpret the results. Patients were not invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this document for readability or accuracy. We will disseminate results to study participants.

Transparency declaration

The lead author affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported and that no important aspects of the study have been omitted, and that any discrepancies from the study have been explained.

Results

Fourteen people with COPD indicated that they would be happy to be contacted by study investigators and all consented to participate in the interviews. If the patient participant desired, caregivers (n=4) were present during the interviews and provided explanatory comments as to the topics raised by the patient participants. No participants dropped out of the study. Interviews were undertaken between October and November 2016, with a duration of 19–77 min.

Facilitators and barriers to COPD self-management in the rural context

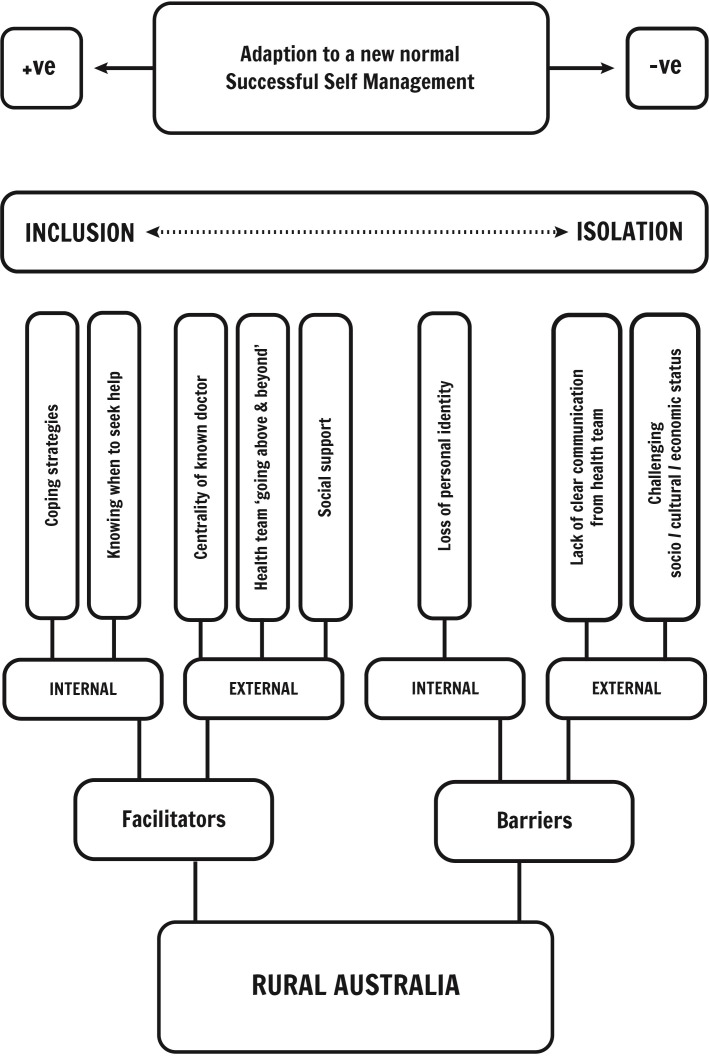

Thematic analysis resulted in four groups of themes that influenced whether a person with COPD was able to adapt to and ultimately self-manage their condition in the rural context, including: internal facilitators (coping strategies; knowledge of when to seek help), external facilitators (centrality of a known doctor; health team ‘going above and beyond’ and social supports), internal barriers (loss of identity) and external barriers (lack of access and clear communication, sociocultural challenges). These themes were furthermore moderated by feelings of ‘inclusion’ (feeling welcomed in the community) or ‘isolation’ (feeling emotionally separate from others in the community) within the rural context. These findings are summarised in figure 1. Ability to adapt to the ‘new normal’ of life with COPD and self-manage COPD could be considered as a spectrum from positive (adaptation to the new normal with effective self-management) to negative (inability to adapt or self-manage).

Figure 1.

Facilitators and barriers to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) self-management in the rural context. Adaptation to the ‘new normal’ of life with COPD and ability to self-manage were influenced by facilitators and barriers, moderated by inclusion.

Internal facilitators to COPD self-management

Internal facilitators that emerged from analysis were the development of coping strategies and learning when to seek help in the context of COPD self-management

Coping strategies

Learning to cope was a key theme with a matter of fact and ‘making the best of things’ approach taken to this new condition: “I didn’t get depressed about (COPD diagnosis) or anything … I thought well you’ve got it, you’ve got to live with it”. (Participant (P)1) Adaptation to a new normal occurred through learning coping strategies and accepting a new pace of life: “You have to perform at the rate your lungs will let you. So you get slower and slower, year-by-year”. (P11) Specific approaches were used to manage symptom fluctuations, with one participant voicing: “Quite often I get attacks… during the night if the temperature drops suddenly… But I can control that quite often—I get up and make a cup of coffee and sit up in the chair … then I go back to bed and I’m alright the next morning” (P14). Others discussed how they learnt how to retain activities that gave them joy: “…we did a lot of dancing and if I got really hot I’d have to go out of the hall into the fresh air … I’d go out there and I could settle my breathing down”. (P1)

Knowing when to seek help

Development of knowledge in how and when to seek help also facilitated adaptation and capacity for self-management. Training in seeking help without delay was voiced as important to avoiding acute deterioration: “Well; self-management, from what they’ve told me and what they’ve taught me, is to live as comfortably as you can with your disease you’ve got and don’t ‘buggerise around if you get crook’ (delay if you get sick)”. (P10) Recognising deterioration was important: “You’re either on a high or you’re on a low. You can feel yourself going down” (P13), as was knowing when to access emergency services: “Well if it gets to the stage where he can’t breathe properly—into the hospital. That’s just what we do”. (Caregiver of P5)

External facilitators to COPD self-management

External facilitators related to the centrality of a known doctor; the health team going ‘above and beyond’ and social support.

Centrality of known doctor

Continuity of care with practitioners led to supportive long-term relationships: “He’s (GP) my rock” (P9) and “if (doctor) were to leave and go somewhere else I don’t know what I’d do”. (P3) Coordination between health members was also raised as important: “with different things she’d (GP) say ‘I’ll ring (the patient’s physician) and talk to her about it. So they worked hand in hand’”. (P12) Integration of health professionals within the community also facilitated trust and confidence for patients to express their needs: “(Doctor) happened to be one of my neighbours…. He asked ‘how is Rufus (my dog)? How are you going?’ He even said ‘what’s your wife doing? Your clothesline is chock-a-block (full) every day’”. Then he started talking, he says ‘What is it?’ I said, “look mate, I’m not happy, I want to go home”. (P7) Rural workforce shortages can inhibit urgent care, however those with established relationships were accorded access: “He said to me, if ever I can’t get in, tell them I’ve got to see him” (P9), similarly another patient voiced: “I talk to the girls at the counter and I’ve got to book in 3 months ahead. I said I’m not booking into you for 3 months ahead—I said I’ll ring you … she puts me in every time”. (P13)

Health team going ‘above and beyond’

Throughout the interviews participants provided examples of when health professionals had gone ‘above and beyond’ to provide support, from simple presence: “while I was in hospital (doctor) came in nearly every day and he didn’t have to” (P13), to assisting with community access: “(Doctor) came ‘round to my place and sat down with my medications. She took them up to the chemist herself and got them put into a Webster pack (Dosette-box)’”. (P8) Several doctors went as far as providing their private contact details: “We had to see (doctor) before we went on holiday and she’d give us her mobile number and ‘if anything happens, call me straight away’”. (P11) Assistance with policy constraints were also noted, these little and kind adjustments were keenly felt by participants: “They let us sneak through the door which brought us right in. Words cannot explain how great they were. We were so comfortable with all the staff that we could have asked them anything”. (P9)

Social support

Community supports created the sense of an ‘inclusive village’, with non-health workers, such as bus drivers, supporting participants to be independent: “They’re great. They lift me up on the thing (disability access ramp) because I’ve got the oxygen”. (P6) Family and caregiver support were also clearly articulated, both in day-to-day care, but also with logistical challenges: “The other night the power went off. So that’s when you really need somebody … you’ve got to go and get an oxygen bottle and set it up to breathe”. (P6) Caregiver support extended to recognition of symptoms and decision-making, as well as recognising when to pace activities: “(She) will pick very quickly if I’m tiring. You never say stop … Just one more thing”. (P11)

Similarly, peer support was also raised in the context of community through pulmonary rehabilitation: “(pulmonary rehabilitation) is amazing. Number 1, you go there for exercises. Number 2, beautiful to sit there and talk to the next person. They all got similar things… We just listen to one another and then naturally crack up a joke or something … We look after one another”. (P7)

Internal barriers to self-management of COPD

Loss of identity, lack of access and clear communication and socioeconomic and cultural challenges were raised as the key barriers to self-management of COPD in the rural context.

Loss of identity

Participants expressed a loss of identity and the associated psychological impact, particularly through changed work-life role: “I was forced to retire. I didn’t like the idea of it. I was depressed”. (P7) This was also expressed as loss of something that brought joy: “I was that wrecked (by having to retire). It was unbelievable. I don’t think that anybody would have loved their jobs as much I loved mine”. (P8) Emotional distress was also connected with the unrelenting nature of the condition: “I thought, this is not worth it. What’s the use in living when you suffer like this even though my mind is clear and everything?” (P7) One caregiver also expressed distress at seeing the progressive decline and impact: “He was deteriorating before my eyes. He also suffered depression because of all this pain”. (Caregiver of P13)

External barriers to self-management of COPD

Lack of access and clear communication

Issues of staff retention in the rural workforce raised barriers to continuity of care and effective communication: “You don’t even get to know (the GPs), 18 months and they’re gone”. (P14) Reduced numbers of health professionals also caused delays in access: “I could only access her every 6 weeks at the least. You could never get her if you were sick”. (P3) Similarly, limited alternatives left some participants to rely on emergency services: “I’ve gone down to see a doctor, and I’ve clashed, or whatever. So they’ve rang an ambulance and said, go to hospital”. (P8) Communication with unfamiliar clinicians also at times left some participants feeling in the dark: “I was in hospital 2 weeks ago and it wasn’t until a week after I got out, with my GP, that I actually found out what was the matter with me”. (P4) The need to continually re-tell their story was also a frustration when health professionals appeared to not communicate with one another:

there’s been a few times where I’ve gone to emergency. You explain the situation—like, you’re having trouble breathing as it is. They’re trying to say oh, how long have you been like this for? Have (they) got any medical records? You’ll see what’s the matter with me is! And then the next doctor comes in for the next shift—they say oh, what are you here for? Talk to each other instead of having to ask the patients. (P8)

Sociocultural challenges

In contrast to those who voiced positive social inclusion, others expressed social isolation: “I wasn’t coping. I wasn’t well enough to do my own food preparation … I’m fairly new and I’m not a local—I didn’t know anyone so you don’t like asking someone”. (P14) In contrast to those afforded access through established relationships, participants newly arrived felt disconnected from support:

The community clinic was the one that I accessed because they HAD TO take new patients. That was my only avenue at the time … I needed to access somebody who knew me because (COPD) doesn’t go by the record sort of thing … when you get sick, you’re sick enough to need care straight away. (P14)

Financial impact was raised several times, with participants having to balance treatments choices as well as resource choices to stay well: “We chose to increase the temperature of the house by a few degrees. It’s just another cost”. (P11) The requirement to replace the stove for oxygen therapy safety was an added burden, and support for such measures was perceived to be influenced by social circumstance: “If you were living in Housing Commission you would be subsidised, but because we were (self-funded retirees)… nothing”. (P6)

Discussion

This study explored patient experiences of living with and managing COPD in the rural context. Our results suggested that community inclusion, or inclusion in the ‘village’ context, moderated adaptation to a ‘new normal’ of living with COPD, and enhanced a person’s ability to cope and ultimately self-manage their condition. Community inclusion also influenced whether a person experienced either a net balance of positive facilitators (knowledge of coping strategies and when to seek help, a central, known doctor, a healthcare team ‘going above and beyond’, social supports) or more pronounced balance of net negative barriers (loss of identity, lack of communication between healthcare team, socioeconomic or cultural disadvantage) to living with and managing COPD. The factors experienced by this rural population are highly relevant to people living in a variety of settings, including urban and suburban environments. However, the impact of these factors may be amplified in rural communities where there may be constrained choice and access to community support providers. Supportive social networks and a sense of ‘place’ are linked to decreased COPD readmission and are recognised as being strong and highly valued in rural areas.33

The benefits of social connection, social support, living with a caregiver and peer support through pulmonary rehabilitation are well recognised in COPD and have been reported widely in previous literature16 34 and are evident in the present study. These benefits have been shown to reduce the likelihood of smoking, increase exercise capacity, reduce emergency department visits and enhance coping.35 36 Patients’ perceived control over COPD was found to be associated with fewer exacerbations.37 Conversely, loss of identity,17 poor continuity of care from health professionals, poor communication between members of the healthcare team,38 exclusion from social networks and socioeconomic disadvantage are equally recognised as key barriers.39 These influences are associated with reduced coping ability, decreased help seeking,40 the need to continually repeat medical history and are barriers to develop trusting relationships with health professionals.41 In comparison with other qualitative Australian studies into the patient’s experience of COPD, beneficial impacts were reported when patients felt supported by community members and health professionals,33 42 43 connected to people and nature,42 felt a strong sense of community43 and felt listened to by health professionals.44

The strength of this study is the exploration of a range of medical, emotional and social supports, and the way these impact people living with COPD in the rural context. Our findings suggest that a rural ‘village’ existed for these patients that encompassed supportive health professionals, family, friends and community members, as has been shown in maternal and child health and healthy ageing contexts.18–20 The understandings regarding social connectedness and the benefit of living within a supportive ‘village’ in a rural context are likely highly relevant to other settings, including urban areas, and could be used to model social supports for others living with COPD. In an urban context, a ‘village’ could develop within a suburb, block of flats or retirement housing development or when people have lived in an area for an extended period of time. The extent to which a person living with COPD is included in the ‘village’ is variable and has a marked influence on coping and self-management ability. Inclusion in the ‘village’, where one’s neighbour could also be one’s doctor or where family members were given the GP’s private telephone number, was strongly facilitative. There were many examples provided of close, trusting, long-term relationships with doctors, health professionals ‘going above and beyond’ and social supports that enabled COPD management within the rural context. Similarly, self-management of COPD has been depicted as being built on a pyramid of four categories of people (the patient (at the apex), their partner, their physician and the public’s perception of the disease).45 Perhaps this pyramid also depicts both the source and importance of each category of people to a person living with COPD.

Previous studies have reported that COPD-related symptoms and behaviours, such as coughing in public and wearing an oxygen mask, heighten feelings of self-blame due to historical smoking, and have been linked to feelings of loneliness and embarrassment.16 17 However, self-blame was not a prominent theme in this study, perhaps due to the protective aspects of social ‘inclusion’ within these established rural communities. Similarly, while much of rural health discourse focuses on deficits in care and experience,46 and that respiratory care within the explored region is based on a rural generalist model, participants in this study did not speak of ‘missing out’ on services, information or access to specialists. Sossai et al described several negative factors influencing life with COPD (anxiety, depression, breathing and sleeping difficulties, reduction in daily/social activities and independence), but the impact of the rural context was generally limited to the associated climate.33 Goodridge’s commentary on this paper suggested that rural patients with COPD often experienced difficulty accessing self-management support and education.33 The participants in our study may be unaware of other models of care delivered through metropolitan centres, or may believe they were receiving the care that met their needs, or the desire to receive services locally or from familiar people was more important that accessing a different model of care elsewhere. Further research is required to understand this perspective, given the unequivocal evidence that there is a lack of access to specialist services in this and other rural contexts.

This study was undertaken at a single site with a sample of people who had been hospitalised with COPD in the preceding 12 months. As such, it is likely to reflect only those perspectives of people who have been in recent contact with health services and were willing to undertake an interview. However, the strength of this work is that it provides important insights into rural healthcare experience and inclusively explored medical, social and emotional supports in this context.

The results of this study suggest that adaptation, coping and effective self-management are enhanced via a range of medical, emotional and social supports. There is substantial value of pulmonary rehabilitation as a de facto community and the benefit of a social ‘village’ in supporting people with chronic progressive disease. Health professionals may consider assessing patients for level of social/community inclusion and connecting patients with available services in the community. This may be of particular importance given the relationship seen between social exclusion and suboptimal coping.

Social support is known to positively influence psychological health and self-efficacy of people with COPD, however less is known about the benefits this confers on overall quality of life and physical functioning47 particularly in the rural context.23 The benefit and experience of living in a supportive ‘village’ community could be further explored in the urban context to further understand the complexities of non-medical social and emotional support. Furthermore, the patient perspective of coping strategies and self-management approaches could be used to inform more user-friendly education material to address the recognised poor knowledge and understanding of COPD.48

Conclusion

In this study, the rural context offered an advantage for the people with COPD who experienced inclusion (in the ‘village’), with the centrality of a known doctor and a health professional team willing to go ‘above and beyond’ key to this positive experience. Evidence of the benefit of strong social and family supports were noted, in line with prior studies. Understanding barriers and facilitators to supported COPD self-management will help inform future rural workforce and service development.

Further research is needed to understand how social networks within the broader social structural conditions influence the way in which patients live with and manage their disease, and to compare experiences of COPD in rural and urban contexts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants of this study and staff at the recruiting sites. The authors would like to thank the team involved in the Managing Chronic Disease in Wangaratta and Benalla project, in particular Tessa Archbold, Megan Tharratt, Jan Lang, Tammie Long and David Kidd.

Footnotes

Twitter: @kristenglenist1

Contributors: Conception and design of the study, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data: KG, HH and RD. Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content: KG, HH and RD. Final approval of the version to be submitted: KG, HH and RD.

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. The authors are supported by the Australian Government Department of Health through the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training Programme.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was granted by the Northeast Health Wangaratta Human Research Ethics Committee (project 175, August 2016). Signed, informed consent was obtained from each interviewee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Fromer L. Implementing chronic care for COPD: planned visits, care coordination, and patient empowerment for improved outcomes. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2011;6:605–14. 10.2147/COPD.S24692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adeloye D, Chua S, Lee C, et al. Global and regional estimates of COPD prevalence: systematic review and meta–analysis. J Glob Health 2015;5:020415 10.7189/jogh.05.020415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Murray CJL, Atkinson C, Bhalla K, et al. The state of US health, 1990-2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA 2013;310:591–608. 10.1001/jama.2013.13805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fletcher MJ, Upton J, Taylor-Fishwick J, et al. COPD uncovered: an international survey on the impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] on a working age population. BMC Public Health 2011;11:612 10.1186/1471-2458-11-612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, et al. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ 2005;330:1007–11. 10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:532–55. 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hillas G, Perlikos F, Tsiligianni I, et al. Managing comorbidities in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2015;10:95–109. 10.2147/COPD.S54473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Williams V, Hardinge M, Ryan S, et al. Patients’ experience of identifying and managing exacerbations in COPD: a qualitative study. npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine 2014;24 10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bucknall CE, Miller G, Lloyd SM, et al. Glasgow supported self-management trial (GSuST) for patients with moderate to severe COPD: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2012;344 10.1136/bmj.e1060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Benzo RP, Abascal-Bolado B, Dulohery MM. Self-Management and quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): the mediating effects of positive affect. Patient Educ Couns 2016;99:617–23. 10.1016/j.pec.2015.10.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hopley M, Horsburgh M, Peri K. Barriers to accessing specialist care for older people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in rural New Zealand. J Prim Health Care 2009;1:207–14. 10.1071/HC09207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jackson K, Oelke ND, Besner J, et al. Patient journey: implications for improving and integrating care for older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Can J Aging 2012;31:223–33. 10.1017/S0714980812000086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Swanson EJ, Rice KL, Rector TS, et al. Quality of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-related health care in rural and urban Veterans Affairs clinics. Federal Practitioner 2017:27–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goodridge D, Hutchinson S, Wilson D, et al. Living in a rural area with advanced chronic respiratory illness: a qualitative study. Prim Care Respir J 2011;20:54–8. 10.4104/pcrj.2010.00062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Luckett T, Phillips J, Johnson M, et al. Insights from Australians with respiratory disease living in the community with experience of self-managing through an emergency department ‘near miss’ for breathlessness: a strengths-based qualitative study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017536 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Halding A-G, Wahl A, Heggdal K. 'Belonging'. 'Patients' experiences of social relationships during pulmonary rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil 2010;32:1272–80. 10.3109/09638280903464471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Disler RT, Green A, Luckett T, et al. Experience of advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Metasynthesis of qualitative research. Jnl Pain Sym Mgt 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lush B, Boddy J. Reflections on the value of a supportive ‘village’ culture for parents, carers, and families: Findings from a community survey. Journal of Social Inclusion 2014;5:44–55. 10.36251/josi.75 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Graham C, Scharlach AE, Kurtovich E. Do villages promote aging in place? results of a longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Gerontology 2018;37:310–31. 10.1177/0733464816672046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McDonough KE, Davitt JK. It takes a village: community practice, social work, and aging-in-place. J Gerontol Soc Work 2011;54:528–41. 10.1080/01634372.2011.581744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ziersch AM, Baum F, Darmawan IGN, et al. Social capital and health in rural and urban communities in South Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health 2009;33:7–16. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2009.00332.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Manderson L. Social capital and inclusion: locating wellbeing in community. Aust Cult Hist 2010;28:233–52. 10.1080/07288433.2010.585516 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brundisini F, Giacomini M, DeJean D, et al. Chronic disease patients' experiences with accessing health care in rural and remote areas: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Ontario Health Tech Assess Ser 2013;13:1–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Victorian department of health. Wangaratta 2012.

- 28. Affair B. State government of Victoria department of health. Department of Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vaske I, Thöne MF, Kühl K, et al. For better or for worse: a longitudinal study on dyadic coping and quality of life among couples with a partner suffering from COPD. J Behav Med 2015;38:851–62. 10.1007/s10865-015-9657-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 3rd edn London: Sage, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Davidson PM, Halcomb E, Gholizadeh L. Focus groups in health research and nursing : Liamputtong P, Research methods in health: foundations for evidence-based practice. Australia & New Zealand: Oxford University Press, 2013: p. 54–71. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kerr C, Nixon A, Wild D. Assessing and demonstrating data saturation in qualitative inquiry supporting patient-reported outcomes research. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2010;10:269–81. 10.1586/erp.10.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sossai K, Gray M, Tanner B. Living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: experiences in northern regional Australia. Int J Ther Rehabil 2011;18:631–41. 10.12968/ijtr.2011.18.11.631 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gysels MH, Higginson IJ. Self-Management for breathlessness in COPD: the role of pulmonary rehabilitation. Chron Respir Dis 2009;6:133–40. 10.1177/1479972309102810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Trivedi RB, Bryson CL, Udris E, et al. The influence of informal caregivers on adherence in COPD patients. Ann Behav Med 2012;44:66–72. 10.1007/s12160-012-9355-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wakabayashi R, Motegi T, Yamada K, et al. Presence of in-home caregiver and health outcomes of older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59:44–9. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03222.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Whalley D, Svedsater H, Doward L, et al. Follow-Up interviews from the Salford lung study (COPD) and analyses per treatment and exacerbations. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 2019;29 10.1038/s41533-019-0123-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Disler RT, Gallagher RD, Davidson PM. Factors influencing self-management in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud 2012;49:230–42. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gardener AC, Ewing G, Kuhn I, et al. Support needs of patients with COPD: a systematic literature search and narrative review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2018;13:1021–35. 10.2147/COPD.S155622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shipman C, White S, Gysels M, et al. Access to care in advanced COPD: factors that influence contact with general practice services. Prim Care Respir J 2009;18:273–8. 10.4104/pcrj.2009.00013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Waibel S, Vargas I, Aller M-B, et al. The performance of integrated health care networks in continuity of care: a qualitative multiple case study of COPD patients. Int J Integr Care 2015;15:e029 10.5334/ijic.1527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lahham A, McDonald CF, Mahal A, et al. Home-Based pulmonary rehabilitation for people with COPD: a qualitative study reporting the patient perspective. Chron Respir Dis 2018;15:123–30. 10.1177/1479972317729050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Longman JM, Singer JB, Gao Y, et al. Community based service providers' perspectives on frequent and/or avoidable admission of older people with chronic disease in rural NSW: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:265 10.1186/1472-6963-11-265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Walters JAE, Cameron-Tucker H, Courtney-Pratt H, et al. Supporting health behaviour change in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with telephone health-mentoring: insights from a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 2012;13:55 10.1186/1471-2296-13-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kaptein A, Fischer M, Scharloo M. Self-Management in patients with COPD: theoretical context, content, outcomes, and integration into clinical care. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2014;9:907–17. 10.2147/COPD.S49622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bourke L, Taylor J, Humphreys JS, et al. “Rural health is subjective, everyone sees it differently”: Understandings of rural health among Australian stakeholders. Health Place 2013;24:65–72. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Barton C, Effing TW, Cafarella P. Social support and social networks in COPD: a scoping review. COPD 2015;12:690–702. 10.3109/15412555.2015.1008691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Russell S, Ogunbayo OJ, Newham JJ, et al. Qualitative systematic review of barriers and facilitators to self-management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: views of patients and healthcare professionals. npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine 2018;28 10.1038/s41533-017-0069-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-030953supp001.pdf (48.6KB, pdf)