Abstract

The sequence–structure–function paradigm of proteins has been revolutionized by the discovery of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) or intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs). In contrast to traditional ordered proteins, IDPs/IDRs are unstructured under physiological conditions. The absence of well‐defined three‐dimensional structures in the free state of IDPs/IDRs is fundamental to their function. Folding upon binding is an important mode of molecular recognition for IDPs/IDRs. While great efforts have been devoted to investigating the complex structures and binding kinetics and affinities, our knowledge on the binding mechanisms of IDPs/IDRs remains very limited. Here, we review recent advances on the binding mechanisms of IDPs/IDRs. The structures and kinetic parameters of IDPs/IDRs can vary greatly, and the binding mechanisms can be highly dependent on the structural properties of IDPs/IDRs. IDPs/IDRs can employ various combinations of conformational selection and induced fit in a binding process, which can be templated by the target and/or encoded by the IDP/IDR. Further studies should provide deeper insights into the molecular recognition of IDPs/IDRs and enable the rational design of IDP/IDR binding mechanisms in the future.

Keywords: binding kinetics, fuzzy interaction, intrinsically disordered proteins, molecular recognition, transition state

Short abstract

Abbreviations

- 3D

three‐dimensional

- AS

alternative splicing

- IDPs

intrinsically disordered proteins

- IDRs

intrinsically disordered regions

- LFER

linear free‐energy relationships

- LLPS

liquid–liquid phase separation

- MoRFs

molecular recognition features

- PTM

posttranslational modification

- SLiMs

short linear motifs

1. INTRODUCTION

Proteins are important biological molecules. The three‐dimensional (3D) structure, which is determined by the primary amino‐acid sequence, is critical for a protein to carry out its functions. Traditionally, proteins are classified as being either ordered (folded) or disordered (unfolded) by analyzing their conformational states. Ordered proteins have well‐defined 3D structures and exhibit small‐scale structural fluctuations under physiological conditions. On the contrary, intrinsically disordered proteins could sample an ensemble of conformations which may be compact (molten globule‐like) or extended (coil‐like or pre‐molten globule‐like).1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Furthermore, proteins can be entirely disordered polypeptides (IDPs) or a combination of disordered regions (IDRs) and ordered domains.6, 7, 8

Based on bioinformatics predictions, IDPs/IDRs are abundant in all species.9, 10, 11 By analyzing the proteomes of 3,484 species and correlating the fraction of disordered residues with proteome size, it is shown that eukaryotes have more disordered residues than prokaryotes.12 A recent comprehensive analysis of over 6 million proteins characterized intrinsic disorder at proteomic and protein levels indicates that IDPs/IDRs are more abundant in eukaryotes and certain functions are exclusively implemented by IDPs/IDRs.13 The correlation between the organism complexity and the amount of intrinsic disorder are consistent with the extensive involvement of IDPs/IDRs in regulatory and signaling functions and the increased disorder content in eukaryotic proteomes might be used by nature to deal with the increased cellular complexity.12, 14, 15

IDPs/IDRs are involved in various biological functions. In a comprehensive bioinformatics study carried out by Xie et al.,16, 17 a positive correlation between the functional annotation of the SwissProt database and the predicted intrinsic disorder has been found. Generally, IDPs/IDRs are enriched in proteins involved in signaling and regulatory functions, including transcription regulation, cell cycle, mRNA processing, scaffolding, and apoptosis.6, 14, 15, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 Consequently, dysregulation of IDPs/IDRs are associated with a variety of human diseases.32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44 Most recently, many IDPs/IDRs are found to be able to undergo liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS), which is related to the assembling of membraneless organelles in vivo.45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53 So far, studies on IDPs/IDRs have greatly extended our understanding on the sequence–structure–function relationship of proteins.29, 54, 55, 56 Recently, the protein structure–function continuum concept was proposed by Uversky to illustrate the numerous biological functions of p53 through multiple proteoforms by various mechanisms and may be extended to many multi‐function IDPs.57

In this review, we will summarize recent advances of our understanding on the molecular recognition of IDPs/IDRs. We will focus on specific interactions between IDPs/IDRs and their targets, which usually result in folding of the IDPs/IDRs upon target binding. We will discuss the mechanistic features of molecular recognition inferred from kinetics, thermodynamics, and structure investigations.

2. MOLECULAR RECOGNITION FEATURES

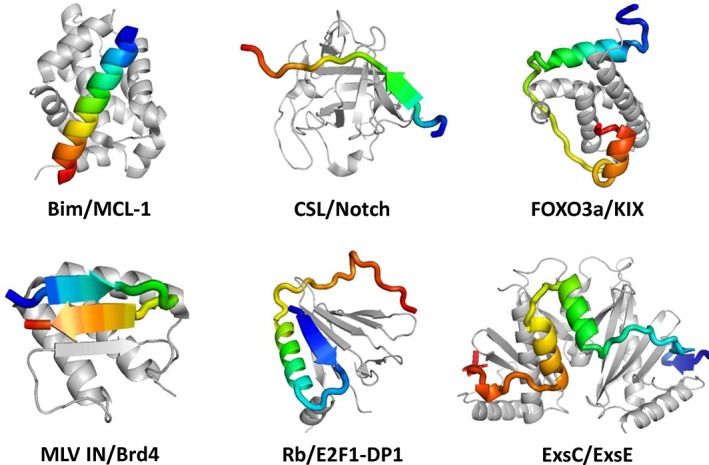

The flexible structures of IDPs/IDRs make them suitable for cellular regulatory and dynamic signaling processes.14 Several functional modes have been summarized for IDPs/IDRs, including entropic chains, effectors, scavengers, assemblers, display sites, and chaperones.7, 30, 58 A common module for molecular recognition within IDPs/IDRs is often known as molecular recognition features (MoRFs) or short linear motifs.59, 60, 61, 62, 63 The sequence features of MoRFs are distinct from the rest portion of IDPs/IDRs, enabling development of predictors to identify MoRFs.64 For example, ANCHOR predicts disordered binding regions based on the pairwise energy estimation from IUPred.65, 66, 67, 68 Usually, upon binding to their partners, MoRFs undergo disorder‐to‐order transitions. This process is termed coupled folding‐binding.69, 70 The structures of MoRFs adopted upon binding can be divided into three types: α‐helix, β‐strand, and irregular secondary structure. IDPs/IDRs can utilize multiple MoRFs simultaneously when interacting with their binding partners (Figure 1).59

Figure 1.

Examples of intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) complex with various combinations of molecular recognition features (MoRFs). IDPs are shown in rainbow color and the targets are shown in gray. PDB IDs are: Bim/MCL‐1 (2NL9), CSL/notch (2FO1), FOXO3a/KIX (2LQI), MLV IN/Brd4 (2N3K), Rb/E2F1‐DP1 (2AZE), and ExsC/ExsE (3KXY)

Studying the recognition mechanisms of IDPs/IDRs with their partners is not a trivial task. In recent years, however, large progress has been made from a close collaboration between experimental and computational studies. A spectrum of techniques have been applied to study IDPs/IDRs, providing valuable information on their structures, dynamic properties and binding mechanisms.2, 3, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75 In parallel, molecular modeling and computer simulations provide atomic pictures of conformation ensembles and binding processes as well as reveal important underlying physical principles.76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82

3. RATE CONSTANTS

Coupled folding with binding has been suggested to enhance the binding rates of IDPs/IDRs.83 Theoretical analysis and computer simulations predicted that the “fly‐casting” effect accelerates the binding rate by twofolds to threefolds.83, 84, 85 Consistent with this prediction, rate constants of IDP/IDR‐protein interactions from the literature show differences from those of ordered proteins in a general trend.85 The binding kinetics of IDPs/IDRs is affected not only by the overall structure flexibility, but also by the local conformation preference of MoRFs. Stabilizing the preformed conformation of MoRFs has been found to accelerate the association rate constants (k on), due to an increase of the probability of converting collision complexes to bound state.86, 87, 88, 89, 90 On the other hand, increasing the degree of disorder has been found to significantly increase the dissociation rate constant (k off), suggesting that the dominant effect of disorder on molecular recognition may be to accelerate dissociation rather than association.87, 91 While computer simulations provide detailed correlation between conformation disorder and binding/unbinding rate constants, it is difficult to test the actual role of disorder in binding kinetics experimentally as it is hard to quantify the extent of disorder and the influence on binding kinetics could be resulted from changes in the interactions between the target and IDP/IDR or changes in the binding mechanism.

Electrostatic interactions could play important roles in the coupled folding‐binding process of IDPs/IDRs as many MoRFs contain charged residues.92 For many studied IDPs/IDRs, the k on values are reduced for about ten folds when the salt concentration increases from low (~50 mM) to high (~500 mM), that is, ∂log(kon)/∂log(Csalt) ≈ − 1 (Table 1), indicating the presence of favorable electrostatic interactions. Molecular dynamics simulations found that long‐range electrostatic interactions accelerate the binding rate in a range consistent with experimental results.97, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108 More importantly, simulations revealed that electrostatic forces enhance the binding kinetics not only by increasing the encounter rate but also by enhancing the efficiency of IDPs/IDRs evolving to the bound states upon encounter.105, 108 Advances in single molecule techniques allow the detection of transient species during a coupled folding‐binding process. Interestingly, the transition path times of ACTR/NCBD interaction is much longer than the transition path times of protein folding, indicating the presence of stable intermediate state along the binding process.109 Furthermore, the lifetime of transient complexes for ACTR/NCBD is also longer than that for barnase/barstar,110 consistent with previous simulation predictions.85

Table 1.

Effect of salt concentration on the association rate constant of IDPs

| IDP | Number of charges | Target | ∂log(kon)/∂log(Csalt) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p5313‐61 | –11 | +1 | NCBD | −2.10 | 93 |

| HPV E7 | −4 | +0 | Rb | −1.56 | 94 |

| MLL | −6 | +1 | KIX | −1.52 | 95 |

| STAT2 | −10 | +4 | TAZ1 | −1.32 | 96 |

| ACTR | −11 | +4 | NCBD | −1.26 | 93 |

| p27 | −16 | +14 | Cdk2/cyclin A | −1.21 | 97 |

| SRC1 | −11 | +5 | NCBD | −1.15 | 93 |

| E3IDP | −12 | +20 | Im3 | −1.06 | 98 |

| TIF2 | −9 | +2 | NCBD | −0.86 | 93 |

| PUMA | −10 | +6 | MCL‐1 | −0.68 | 99 |

| WASP | −21 | +21 | Cdc42 | −0.62 | 100 |

| p5313‐63 | −12 | +1 | Mdm2 | −0.56 | 101 |

| p7311‐25 | −3 | +0 | Mdm2 | −0.38 | 101 |

| c‐Myb | −5 | +5 | KIX | −0.25 | 102 |

| p5315‐29 | −3 | +1 | Mdm2 | −0.21 | 101 |

| p6352‐65 | −3 | +0 | Mdm2 | 0.13 | 101 |

| eIF4G | −2 | +4 | eIF4E | 0.75 | 103 |

Abbreviation: IDP, intrinsically disordered protein.

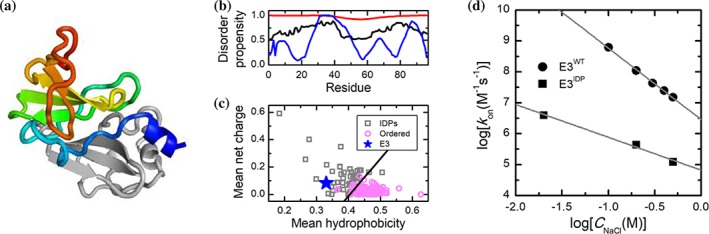

It is noted that as the conformations of IDPs/IDRs are highly dynamic, electrostatic interactions between IDPs/IDRs and their targets during the encounter process may be different from those of the corresponding ordered proteins, which may be reflected from a recent study on the interactions between the colicin E3 rRNase domain (E3) and the immunity protein Im3 (Figure 2a).98 Although E3 is a folded domain, disorder prediction suggests that it contains high disorder propensities (Figure 2b,c). Actually, a single alanine mutation at Tyr507 within the hydrophobic core of E3 causes the protein to become an IDP (E3IDP). Kinetics studies show that k on of E3WT with Im3 is decreased by three orders of magnitude when the salt concentration is increased. However, under the same range of salt concentration, k on of E3IDP with Im3 is only decreased by less than 40 folds (Figure 2d).98 However, as the mechanism of E3IDP binding to Im3 is unclear, it is unknown whether E3IDP folds before binding or folds during binding. In this context, the salt dependence of the association rate constant for E3IDP/Im3 interaction remains elusive.

Figure 2.

Binding of E3 to Im3. (a) Crystal structure of E3/Im3 complex. E3 is shown in rainbow color and Im3 in gray. (b) Disorder propensity prediction of E3 using three different predictors: IUPred2 (black), MFDp2 (red), and PONDR VL‐XT (blue). (c) Location of E3 on the charge‐hydrophobicity plot. The black line indicates the boundary between the intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) region and the ordered proteins. (d) Effect of salt concentration on k on for E3WT and E3IDP 98

4. CONFORMATIONAL SELECTION, INDUCED FIT AND BEYOND

Recently, Dunker and Oldfield111 suggested that the interaction between an IDP/IDR and its partner should not be described as induced fit where the protein is folded but can adjust its structure to fit the substrate. However, since the discovery of IDPs/IDRs, the sequence–structure paradigm has been revolutionized. In this context, it should be reasonable to expand the concepts of induced fit to analyze the binding processes of IDPs/IDRs. Thus, in an induced fit process, unfolded conformations of an IDP/IDR are able to weakly interact with the target to form encounter complexes which induce the unfolded conformations fold into the bound conformations. On the contrary, in a conformational selection process, an IDP/IDR samples unfolded conformation as well as pre‐folded conformations and only the prefolded conformations are binding competent.

Conformational selection and induced fit have been widely applied to explain the coupled folding‐binding process of IDPs/IDRs.75, 112, 113 Which mechanism dominates during the binding process depends on several factors, including the structure preference and conformational dynamics of the IDPs/IDRs, the association rate, and the concentration as well.114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125 It has been established that IDPs/IDRs sample a variety of conformations rapidly.126, 127, 128, 129 At one extreme, if the conformation ensemble of an IDP/IDR in the unbound state is completely different from that in the bound state, it is expected that the binding process proceeds via the induced fit mechanism. Except this extreme condition, (partially) bound‐like conformations could be sampled by the free IDPs/IDRs. It is plausible that these preformed bound‐like conformations can also initiate the binding process. Under such circumstance, the observed binding mechanism is determined by a competition between the flux of conformational selection and that of induced fit.119, 120, 121, 122 The flux from unbound state to bound state is determined by the folding/unfolding rate constants, association/dissociation rate constants as well as protein concentrations.119 The flux description predicts that conformational selection is favored when the folding kinetics of free IDPs/IDRs is fast, affinity for inactive conformations is low, and protein concentration is low.121 In another study, similar conclusions are reached for the effect of protein concentration via molecular dynamics simulations; however, the effect of conformation transition kinetics is opposite.120 Sampling of the bound‐like conformations in the unbound state is necessary but not sufficient for a conformational selection process. As conformational transitions occur in the unbound state as well as in the loosely bound state, increasing conformation transition kinetics will push the mechanism toward induced fit.120, 122

Several experimental strategies have been proposed to distinguish conformational selection from induced fit. Weikl and Deuster114 proposed a framework by perturbing the conformational equilibrium between the inactive conformations and active conformations via introducing mutation far from ligand binding site. In the case of conformational selection, such mutations will mainly change the association rate, whereas in the case of induced fit, the dissociation rate will be mainly affected. In the interactions between the BH3 motif of PUMA and the structured protein MCL‐1, the helical structure of PUMA was modulated by mutating solvent‐exposed residues to proline or glycine.87, 130 The mutations resulted in a modest effect on k on but a significant effect on k off, suggesting that the PUMA/MCL‐1 interaction is an induced fit process. Stabilizing the helical conformation by trifluoroethanol may be applied to perturb the conformational equilibrium as well. Increasing the trifluoroethanol concentration increased the helix content of c‐Myb and decreased the dissociation rate of c‐Myb/KIX complex, suggesting that folding of c‐Myb is induced after KIX binding.131 The ACTR/NCBD interaction was investigated by selectively perturbing the amount of secondary structure in free ACTR via mutation and k on and k off were affected to similar extent,86, 89 suggesting that conformational selection is involved in the ACTR/NCBD binding process. While mutational analysis provides clues to speculate the binding mechanism, a correlation between helix propensity and rate constants is not a proof for conformational selection.116, 132 Other proposed strategies rely on measuring the observed rate constant under various ligand or/and target concentrations and investigating the dependence of observed rate constant on concentration.115, 116, 117, 118 For example, a comparison of the observed rate constant for various ACTR/NCBD concentrations and NTAIL/XD concentrations suggest that their binding processes are induced fit.116, 133, 134

From studies on IDP/IDR‐protein interactions, it is likely that the binding processes are induced fit combined with various degree of conformational selection.75, 135 As discussed above, the relative flux through these two pathways is determined by the protein concentrations, association rate and conformation transition kinetics. It is plausible that the partially preformed bound‐like conformations play a role in the initial binding step, forming weak encounter complexes which further evolve into the bound conformation.90 Recently, through NMR investigation, Schneider et al.136 found that the free‐state conformational equilibrium of NTAIL is funneled by interactions with XD, leading to preformed bound‐like conformations in the encounter complex. Thus, the free‐state conformational transition of an IDP/IDR and its interactions with the target are coupled in the “conformational funneling” description of the folding‐binding process.132, 136 Structure information on the encounter complexes, the intermediates, and transition states will be of great value for comprehensive understanding of the entire binding process.

5. THE TRANSITION STATES

It is important to analyze the transition state to understand how a coupled folding‐binding process crosses the free energy barrier. This can be achieved by ϕ‐value analysis and linear free‐energy relationships (LFERs) analysis. In a coupled‐folding binding process, the ϕ‐values are calculated from the free energy change for the transition state (ΔΔG ‡) and at equilibrium (ΔΔG Eq):

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

By comparing the influence of a point mutation on k on and K d, the ϕ‐value of a residue provides information on the proportion of native contacts (either intermolecular or intramolecular) it makes at the transition state. In general, residues with ϕ ≈ 0 and ϕ ≈ 1 indicate their structures in the transition state resemble those in the unbound state and the bound state, respectively.

Although with a lower resolution, the location of transition state can also be inferred from the LFER analysis. Small structure alteration on the unbound molecules will result in changes in the complex stability and association kinetics by:

| (4) |

The parameter α (0 ≤ α ≤ 1) measures the location of the transition state along the binding path. Binding processes with α ≈ 0 and α ≈ 1 mean that the transition state is unbound‐like and bound‐like, respectively. The LFER analysis is helpful to identify the location of transition state when mutations result in small changes in stability, prohibiting reliable calculations of ϕ‐values.

ϕ‐value analysis and LFER analysis have been applied to many IDP/IDR complexes (Table 2). In most studied cases, low fractional values of ϕ and α are commonly observed, indicating that IDPs/IDRs remain largely unstructured in the transition states. This is manifested in the conformation ensemble of transition states obtained via molecular dynamics simulations using ϕ‐values as restraints.138, 147 It is noted that ϕ‐values are not evenly distributed along the sequences. Residues with high ϕ‐value may serve as the anchor sites to stabilize the encounter complexes, allowing the encounter complexes to cross the free energy barrier and evolve to native bound states. This picture resembles the dock‐and‐coalesce mechanism proposed by Zhou et al.150 Furthermore, low values of ϕ and α highlight the importance of non‐specific interactions (including electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions) in the initial stage of binding, probably stabilizing the encounter complexes.

Table 2.

ϕ‐Value analysis of coupled folding‐binding process

| IDP | Target | ϕ‐Value distribution | Reference | IDP | Target | ϕ‐Value distribution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIF‐1α | TAZ1 |

|

137 | c‐Myb | KIX |

|

88, 138, 139 |

| STAT2 | TAZ1 |

|

96 | pKID | KIX |

|

140 |

| PUMA | A1 |

|

141 | MLL | KIX |

|

142 |

| PUMA | MCL‐1 |

|

130, 141 | E6 peptide | PDZ2 |

|

143 |

| BID | A1 |

|

141 | S peptide | S protein |

|

144 |

| BID | MCL‐1 |

|

141 | NTAIL | X domain |

|

145 |

| α‐Spectrin | β‐Spectrin |

|

146 | ACTR | NCBD |

|

86, 147, 148 |

| C‐terminal tail of nNOS PDZ | Syntrophin PDZ |

|

149 |

Note: The IDPs are colored in light green and the targets are colored in gray. Residues with low (ϕ ≤ 0.25), medium (0.25 < ϕ < 0.6), and high (ϕ ≥ 0.6) ϕ‐values are highlighted in blue, magenta, and red, respectively.

6. IDPS/IDRS ENCODED BINDING VERSUS TARGET TEMPLATED FOLDING

Since IDPs/IDRs are mainly unfolded in their unbound states, their folded structures observed in the complex state should be induced or stabilized by the binding partners. It remains unclear how a coupled folding‐binding process is encoded. The sequence–structure relationship of proteins tells that the 3D structure of a protein is primarily encoded by its sequence. Extending this paradigm to the coupled folding‐binding of IDPs/IDRs, it is expected that the folded structure of an IDP/IDR in its bound state and its binding mechanism are determined by its sequence and/or the target's sequence (thus the target's structure).

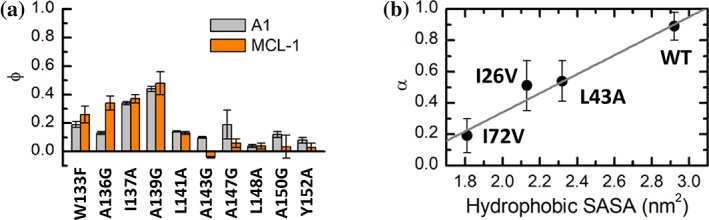

An IDP/IDR binds to diverse targets and folds into similar structures resembling its free conformation ensemble should support that the folded structure of an IDP/IDR is encoded by its sequence. An example is the N‐terminal transactivation domain of p53, which forms similar α‐helical structures upon binding to Mdm2 (PDB 1YCR), MdmX (PDB 2MWY), TAZ1 (PDB 5HOU), TAZ2 (PDB 2MZD), tfb1 PH domain (PDB 2GS0), RPA70 (PDB 2B3G), HMGB1 (PDB 2LY4), and NCBD (PDB 2L14). Besides the folded structure, the binding mechanism can also be encoded by the IDPs/IDRs. Clarke et al141 compared the transition states between the disordered BH3‐only proteins PUMA and BID and the folded BCL‐2–like proteins A1 and MCL‐1 using ϕ‐value analysis. They found that the ϕ‐value profiles for PUMA and BID are conserved when binding to different partners, suggesting that the binding processes of PUMA and BID are encoded by the IDPs/IDRs but not templated by the partners (Figure 3a). Recently, Wu and Zhou altered the binding pathways of WASP with Cdc42, either suppressed the original dominant pathway or promoted a new dominant pathway through manipulating the charged residues on WASP,151 further emphasized the role of IDPs/IDRs in encoding the binding process.

Figure 3.

Illustrations of intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) encoded binding and target templated binding. (a) ϕ‐values for the disordered BH3‐only protein PUMA binding with BCL‐2–like proteins A1 and MCL‐1.141 (b) correlation of α‐value from linear free‐energy relationships (LFER) analysis for c‐Myb with the hydrophobic solvent accessible surface area in the binding site on KIX138

On the other hand, there are also evidences showing that the folding/binding process is templated by the target. Although they bind to the same pocket of S100B, the C‐terminal segment of p53 and TRTK‐12 show low sequence similarity and form different bound conformations. However, computer simulations show strong similarities in the binding intermediate states of the two peptides, suggesting that S100B templates the binding process.152 Toto et al. perturbed the hydrophobic network of KIX using site‐directed mutagenesis and investigated the folding mechanism of c‐Myb with wild‐type and mutated KIX.138 By performing a LFER analysis, they found that the α‐value decreases from 0.89 for wild‐type KIX to around 0.5 for I26V and L43A mutants and to 0.19 for I72V mutant. The decrease in α‐value appears to be correlated to the decrease in the hydrophobic solvent accessible surface area in the binding site on KIX [Figure 3b]. It is surprised to find that the structure of KIX dictates the folding mechanism of c‐Myb as c‐Myb has a strong propensity for α‐helix formation in its N‐terminus and the coupled folding‐binding process of c‐Myb to KIX has been suggested to involve elements of conformational selection.88 The templated folding mechanism has been suggested to enable IDPs/IDRs to be specifically recognized by multiple targets.138 A similar strategy was applied to investigate the interactions between NTAIL and XD and revealed that the binding process of NTAIL is very malleable and is affected by the structure of XD.153 On the contrary, mutagenesis and ϕ‐value analysis revealed that the transition state of ACTR/NCBD complex is highly heterogeneous and is robust with respect to most mutations for ACTR or NCBD.147

As IDPs/IDRs possess various sequence and structure preferences, the above discussions indicate that the coupled folding‐binding process of an IDP/IDR could be templated by the partner as well as encoded by its sequence. Further mechanistic studies are required to reveal the microscopic details on how a target templates or how an IDP/IDR encodes the binding/folding process.

7. EFFECT OF MACROMOLECULAR CROWDING

The intracellular environment is very crowded since up to 40% of the volume of a cell is occupied by biological macromolecules.154 Macromolecular crowding can affect protein–target binding and protein folding.155 In particular, the malleability of IDPs/IDRs makes them susceptible to the influence of macromolecular crowders.156, 157 Conformational compaction of IDPs/IDRs by macromolecular crowders has been observed, where the effect depends not only on the crowder size and concentration, but also on the properties of IDPs/IDRs.158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163 MAP2c, p21Cip1, and FlgM show global compaction and local structuring in crowded conditions.164, 165 The distal helix of calcineurin and transiently helical regions of ACTR are also stabilized when crowded by synthetic polymers.166, 167 However, conformational compaction induced by crowders is not necessary to promote secondary structure formation for IDPs/ IDRs. For example, α‐Casein, the C‐terminal activation domain of c‐Fos, and the kinase‐inhibition domain of p27Kip1 shows little structural changes under crowded conditions.164, 168

Besides modulating the conformational properties of IDPs/IDRs, macromolecular crowding also affects their diffusion properties. In general the translational and rotational diffusions of IDPs/IDRs are reduced.169, 170 Interestingly, the effect of crowding on the diffusion of IDPs/IDRs is less than that on folded proteins.169, 170 Consequently, larger IDPs/IDRs may diffuse faster than smaller folded proteins in cells.169 Recently, study on FlgM under crowded condition reveals the presence of extended conformations which snake through interstitial crevices and bind multiple crowders simultaneously.171 It is probable that such extended conformations may facilitate recognition of IDPs/IDRs under crowded conditions.

It is also important to directly study the effect of macromolecular crowding on the molecular recognition process. Binding of calmodulin with CaMKI peptide was investigated under crowded conditions.172 It was found that the on‐ and off‐rates are reduced by about two folds in a compensatory fashion, thus the binding affinity is almost not changed. The reduction of association rate constant suggests that binding of CaMKI peptide with calmodulin is under diffusion control and crowding slows down the diffusion process.155, 172 For reaction control binding process, it is expected that the association rate constant will be increased.155 In another study, computer simulation on the coupled folding‐binding of pKID with KIX showed that the folding‐binding mechanism observed in bulk solution remains unchanged under highly crowded conditions.173 It seems that molecular crowding has small effect on the binding mechanism of IDPs/IDRs.

8. DYNAMIC CONTACTS AND FUZZY INTERACTIONS

While the main recognition elements are folded upon binding for many IDPs/IDRs, they may still exhibit conformational dynamics in the complex state.174, 175 For example, the TAD of STAT2 only undergoes a partial disorder‐to‐order transition upon binding with TAZ1 and retains subnanosecond motions.176 Conformational dynamics in the bound state enables the IDPs/IDRs to form polymorphic contacts with the partners.177 Such heterogeneity in the bound form is referred to as fuzziness.175, 178 Fuzziness and dynamic binding are universal in the molecular recognition of IDPs/IDRs and are beneficial for their function.8, 174, 179 The presence of fuzzy interacting regions adjacent to the main binding elements can regulate binding affinity, specificity, and selectivity.180, 181, 182, 183 Fuzzy regions also facilitate IDPs/IDRs‐mediated allosteric communication.184 Furthermore, transient binding interactions can promote formation of non‐native interactions stabilizing the encounter complexes, thus enhance the binding kinetics.185 Dynamic interactions can also modulate the folding‐binding mechanism of IDPs/IDRs.186 As discussed above, folding of c‐Myb is templated by KIX, where transient non‐native hydrophobic interactions between c‐Myb and KIX populate when the hydrophobic surface in the binding site of KIX is enlarged.138

Multivalent dynamic interactions are the main driving forces of LLPS.187, 188 Though many IDPs/IDRs involved in LLPS apply multisite electrostatic and aromatic interactions, dynamic coupled folding‐binding interactions mediated by specific recognition elements can also drive LLPS. For example, interactions between SH3 domain and proline‐rich motif are involved in the LLPS of the nephrin–NCK–N‐WASP system and the RIM–RIM‐BP system.189, 190 PDZ domain‐mediated binding is required for phase separation of PSD scaffold proteins.191, 192 Multivalent arginine‐rich linear motifs interact with the NPM1 pentamer, leading to LLPS.193 Within the protein‐rich droplets, non‐native transient interactions are expected to become more populated than in dilute solution. Nevertheless, the specific binding between the recognition motif and the target domain should remain unchanged.

9. POSTTRANSLATIONAL MODIFICATIONS

IDPs/IDRs are enriched in posttranslational modification (PTM) sites, such as phosphorylation, acetylation, and methylation.16, 194, 195 PTMs can regulate molecular recognition of IDPs/IDRs in various ways.18 For example, PTMs can alter the free energy landscapes of IDPs/IDRs, leading to changes in the conformation ensembles. Bah et al. showed that phosphorylation of 4E‐BP2 at T37 and T46 induces folding of 4E‐BP2 into a four β‐strand structure, sequestering the eIF4E‐binding motif and blocking its accessibility to eIF4E.196 However, the structural changes induced by PTMs could also be subtle, as observed in the N‐terminal transactivation domain of p53.197 PTMs located at the binding interface can directly regulate the interactions between IDPs/IDRs and the targets, for example, phosphorylation will introduce electrostatic interactions between the phosphate moiety and the binding partner.198 Interestingly, PTMs alter not only the equilibrium conformation ensemble but also conformational exchange among different conformations.199 Consequently, the binding mechanisms can also be modulated by PTMs.

10. ALTERNATIVE SPLICING

Alternative splicing (AS) generates various protein forms from a single gene. Previous studies have revealed that AS sites are often located within IDRs which are enriched in molecular recognition motifs.200, 201 As molecular recognition processes of IDPs/IDRs are mainly mediated by short recognition elements, removal of recognition elements by AS will eliminate existed molecular interactions or enable new interactions when competitive interactions are removed. Some proteins contain auto‐inhibition segments that mask the binding sites or compete with other molecules for binding.202 Removal of the auto‐inhibition segments by AS will switch the proteins into active states or increase the binding affinities for other molecules. Consequently, removing disordered segments containing different functional or signaling elements allows for rewiring the cellular signaling pathways.19, 26, 203

11. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

IDPs/IDRs are abundant in all species and involved in vital biological processes. Coupled folding upon binding is an important mode of molecular recognition for IDPs/IDRs. IDPs/IDRs can employ various combinations of conformational selection and induced fit mechanisms and the binding process can be templated by the target and encoded by the IDP/IDR as well. The coupled folding‐binding process can also be heterogeneous or fuzzy. While great efforts have been devoted to investigating the complex structures and binding kinetics and affinities, our knowledge on the binding mechanism of IDPs/IDRs remains very limited. Application of advanced kinetic techniques and NMR will provide deeper understanding on the features/mechanisms of molecular recognition of IDPs/IDRs in the future, which may enable rational design of IDP/IDR binding mechanisms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 21603121 to Y.H.), and Hubei University of Technology (M.G., Y.H., and Z.S.).

Yang J, Gao M, Xiong J, Su Z, Huang Y. Features of molecular recognition of intrinsically disordered proteins via coupled folding and binding. Protein Science. 2019;28:1952–1965. 10.1002/pro.3718

Jing Yang and Meng Gao contributed equally to this study.

Funding information Hubei University of Technology; National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant/Award Number: 21603121

Contributor Information

Zhengding Su, Email: zhengdingsu@hbut.edu.cn.

Yongqi Huang, Email: yqhuang@pku.edu.cn.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bhowmick A, Brookes DH, Yost SR, et al. Finding our way in the dark proteome. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:9730–9742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gibbs EB, Showalter SA. Quantitative biophysical characterization of intrinsically disordered proteins. Biochemistry. 2015;54:1314–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brucale M, Schuler B, Samori B. Single‐molecule studies of intrinsically disordered proteins. Chem Rev. 2014;114:3281–3317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kragelj J, Ozenne V, Blackledge M, Jensen MR. Conformational propensities of intrinsically disordered proteins from NMR chemical shifts. ChemPhysChem. 2013;14:3034–3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Uversky VN. Natively unfolded proteins: A point where biology waits for physics. Protein Sci. 2002;11:739–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Habchi J, Tompa P, Longhi S, Uversky VN. Introducing protein intrinsic disorder. Chem Rev. 2014;114:6561–6588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van der Lee R, Buljan M, Lang B, et al. Classification of intrinsically disordered regions and proteins. Chem Rev. 2014;114:6589–6631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Uversky VN. Functional roles of transiently and intrinsically disordered regions within proteins. FEBS J. 2015;282:1182–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pancsa R, Tompa P. Structural disorder in eukaryotes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dunker AK, Obradovic Z, Romero P, Garner EC, Brown CJ. Intrinsic protein disorder in complete genomes. Genome Inform Ser Workshop Genome Inform. 2000;11:161–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ward JJ, Sodhi JS, McGuffin LJ, Buxton BF, Jones DT. Prediction and functional analysis of native disorder in proteins from the three kingdoms of life. J Mol Biol. 2004;337:635–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xue B, Dunker AK, Uversky VN. Orderly order in protein intrinsic disorder distribution: Disorder in 3500 proteomes from viruses and the three domains of life. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2012;30:137–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Peng Z, Yan J, Fan X, et al. Exceptionally abundant exceptions: Comprehensive characterization of intrinsic disorder in all domains of life. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:137–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Intrinsically disordered proteins in cellular signalling and regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:18–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yruela I, Oldfield CJ, Niklas KJ, Dunker AK. Evidence for a strong correlation between transcription factor protein disorder and organismic complexity. Genome Biol Evol. 2017;9:1248–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xie H, Vucetic S, Iakoucheva LM, et al. Functional anthology of intrinsic disorder. 3. Ligands, post‐translational modifications, and diseases associated with intrinsically disordered proteins. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:1917–1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xie H, Vucetic S, Iakoucheva LM, et al. Functional anthology of intrinsic disorder. 1. Biological processes and functions of proteins with long disordered regions. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:1882–1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bah A, Forman‐Kay JD. Modulation of intrinsically disordered protein function by post‐translational modifications. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:6696–6705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Buljan M, Chalancon G, Dunker AK, et al. Alternative splicing of intrinsically disordered regions and rewiring of protein interactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2013;23:443–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zagrovic B, Bartonek L, Polyansky AA. RNA‐protein interactions in an unstructured context. FEBS Lett. 2018;592:2901–2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Staby L, O'Shea C, Willemoes M, Theisen F, Kragelund BB, Skriver K. Eukaryotic transcription factors: Paradigms of protein intrinsic disorder. Biochem J. 2017;474:2509–2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Role of intrinsic protein disorder in the function and interactions of the transcriptional coactivators CREB‐binding protein (CBP) and p300. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:6714–6722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tantos A, Han KH, Tompa P. Intrinsic disorder in cell signaling and gene transcription. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;348:457–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moldoveanu T, Follis AV, Kriwacki RW, Green DR. Many players in BCL‐2 family affairs. Trends Biochem Sci. 2014;39:101–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang Y, Bugge K, Kragelund BB, Lindorff‐Larsen K. Role of protein dynamics in transmembrane receptor signalling. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2018;48:74–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhou J, Zhao S, Dunker AK. Intrinsically disordered proteins link alternative splicing and post‐translational modifications to complex cell signaling and regulation. J Mol Biol. 2018;430:2342–2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pancsa R, Tompa P. Coding regions of intrinsic disorder accommodate parallel functions. Trends Biochem Sci. 2016;41:898–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Varadi M, Zsolyomi F, Guharoy M, Tompa P. Functional advantages of conserved intrinsic disorder in RNA‐binding proteins. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Berlow RB, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Expanding the paradigm: Intrinsically disordered proteins and allosteric regulation. J Mol Biol. 2018;430:2309–2320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Berlow RB, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Functional advantages of dynamic protein disorder. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:2433–2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jakob U, Kriwacki R, Uversky VN. Conditionally and transiently disordered proteins: Awakening cryptic disorder to regulate protein function. Chem Rev. 2014;114:6779–6805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Midic U, Oldfield CJ, Dunker AK, Obradovic Z, Uversky VN. Protein disorder in the human diseasome: Unfoldomics of human genetic diseases. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vavouri T, Semple JI, Garcia‐Verdugo R, Lehner B. Intrinsic protein disorder and interaction promiscuity are widely associated with dosage sensitivity. Cell. 2009;138:198–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Uyar B, Weatheritt RJ, Dinkel H, Davey NE, Gibson TJ. Proteome‐wide analysis of human disease mutations in short linear motifs: Neglected players in cancer? Mol Biosyst. 2014;10:2626–2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Meyer K, Kirchner M, Uyar B, et al. Mutations in disordered regions can cause disease by creating dileucine motifs. Cell. 2018;175:239–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Babu MM. The contribution of intrinsically disordered regions to protein function, cellular complexity, and human disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 2016;44:1185–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Iakoucheva LM, Brown CJ, Lawson JD, Obradović Z, Dunker AK. Intrinsic disorder in cell‐signaling and cancer‐associated proteins. J Mol Biol. 2002;323:573–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Uversky VN, Oldfield CJ, Dunker AK. Intrinsically disordered proteins in human diseases: Introducing the D2 concept. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:215–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Uversky VN, Dave V, Iakoucheva LM, et al. Pathological unfoldomics of uncontrolled chaos: Intrinsically disordered proteins and human diseases. Chem Rev. 2014;114:6844–6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kulkarni P, Uversky VN. Intrinsically disordered proteins in chronic diseases. Biomolecules. 2019;9:147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Uversky VN. Intrinsic disorder, protein‐protein interactions, and disease. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2018;110:85–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tuu‐Szabo B, Hoffka G, Duro N, Fuxreiter M. Altered dynamics may drift pathological fibrillization in membraneless organelles. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom. 2019;1867:988–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Elbaum‐Garfinkle S. Matter over mind: Liquid phase separation and neurodegeneration. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:7160–7168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Oates ME, Romero P, Ishida T, et al. D2P2: Database of disordered protein predictions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D508–D516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Boeynaems S, Alberti S, Fawzi NL, et al. Protein phase separation: A new phase in cell biology. Trends Cell Biol. 2018;28:420–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Li XH, Chavali PL, Pancsa R, Chavali S, Babu MM. Function and regulation of phase‐separated biological condensates. Biochemistry. 2018;57:2452–2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shin Y, Brangwynne CP. Liquid phase condensation in cell physiology and disease. Science. 2017;357:eaaf4382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Aguzzi A, Altmeyer M. Phase separation: Linking cellular compartmentalization to disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26:547–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Uversky VN, Kuznetsova IM, Turoverov KK, Zaslavsky B. Intrinsically disordered proteins as crucial constituents of cellular aqueous two phase systems and coacervates. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Darling AL, Liu Y, Oldfield CJ, Uversky VN. Intrinsically disordered proteome of human membrane‐less organelles. Proteomics. 2018;18:e1700193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Uversky VN. Intrinsically disordered proteins in overcrowded milieu: Membrane‐less organelles, phase separation, and intrinsic disorder. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2017;44:18–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Uversky VN. Protein intrinsic disorder‐based liquid‐liquid phase transitions in biological systems: Complex coacervates and membrane‐less organelles. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2017;239:97–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Turoverov KK, Kuznetsova IM, Fonin AV, Darling AL, Zaslavsky BY, Uversky VN. Stochasticity of biological soft matter: Emerging concepts in intrinsically disordered proteins and biological phase separation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2019;44:716–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Minde DP, Dunker AK, Lilley KS. Time, space, and disorder in the expanding proteome universe. Proteomics. 2017;17:1600399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Burger VM, Nolasco DO, Stultz CM. Expanding the range of protein function at the far end of the order‐structure continuum. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:6706–6713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tompa P, Schad E, Tantos A, Kalmar L. Intrinsically disordered proteins: Emerging interaction specialists. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2015;35:49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Uversky VN. p53 proteoforms and intrinsic disorder: An illustration of the protein structure‐function continuum concept. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Liu ZR, Huang YQ. Advantages of proteins being disordered. Protein Sci. 2014;23:539–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mohan A, Oldfield CJ, Radivojac P, et al. Analysis of molecular recognition features (MoRFs). J Mol Biol. 2006;362:1043–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Davey NE, Van Roey K, Weatheritt RJ, et al. Attributes of short linear motifs. Mol Biosyst. 2012;8:268–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Seo MH, Kim PM. The present and the future of motif‐mediated protein‐protein interactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2018;50:162–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kim DH, Han KH. Transient secondary structures as general target‐binding motifs in intrinsically disordered proteins. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:3614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Oldfield CJ, Cheng YG, Cortese MS, Romero P, Uversky VN, Dunker AK. Coupled folding and binding with a‐helix‐forming molecular recognition elements. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12454–12470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Meng F, Uversky VN, Kurgan L. Comprehensive review of methods for prediction of intrinsic disorder and its molecular functions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74:3069–3090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Mészáros B, Simon I, Dosztányi Z. Prediction of protein binding regions in disordered proteins. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Dosztanyi Z, Meszaros B, Simon I. ANCHOR: Web server for predicting protein binding regions in disordered proteins. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2745–2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Meszaros B, Dosztanyi Z, Simon I. Disordered binding regions and linear motifs‐‐bridging the gap between two models of molecular recognition. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Meszaros B, Erdos G, Dosztanyi Z. IUPred2A: Context‐dependent prediction of protein disorder as a function of redox state and protein binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W329–W337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Linking folding and binding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:31–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Coupling of folding and binding for unstructured proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12:54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Milles S, Salvi N, Blackledge M, Jensen MR. Characterization of intrinsically disordered proteins and their dynamic complexes: From in vitro to cell‐like environments. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2018;109:79–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. LeBlanc SJ, Kulkarni P, Weninger KR. Single molecule FRET: A powerful tool to study intrinsically disordered proteins. Biomolecules. 2018;8:140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Schneider R, Blackledge M, Jensen MR. Elucidating binding mechanisms and dynamics of intrinsically disordered protein complexes using NMR spectroscopy. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2018;54:10–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Stuchfield D, Barran P. Unique insights to intrinsically disordered proteins provided by ion mobility mass spectrometry. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2018;42:177–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Shammas SL, Crabtree MD, Dahal L, Wicky BI, Clarke J. Insights into coupled folding and binding mechanisms from kinetic studies. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:6689–6695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ciemny MP, Badaczewska‐Dawid AE, Pikuzinska M, Kolinski A, Kmiecik S. Modeling of disordered protein structures using Monte Carlo simulations and knowledge‐based statistical force fields. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Das P, Matysiak S, Mittal J. Looking at the disordered proteins through the computational microscope. ACS Cent Sci. 2018;4:534–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Best RB. Computational and theoretical advances in studies of intrinsically disordered proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2017;42:147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Levine ZA, Shea JE. Simulations of disordered proteins and systems with conformational heterogeneity. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2017;43:95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Chong SH, Chatterjee P, Ham S. Computer simulations of intrinsically disordered proteins. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2017;68:117–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Chen T, Song J, Chan HS. Theoretical perspectives on nonnative interactions and intrinsic disorder in protein folding and binding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2015;30:32–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Baker CM, Best RB. Insights into the binding of intrinsically disordered proteins from molecular dynamics simulation. WIREs Comput Mol Sci. 2014;4:182–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Shoemaker BA, Portman JJ, Wolynes PG. Speeding molecular recognition by using the folding funnel: The fly‐casting mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8868–8873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Trizac E, Levy Y, Wolynes PG. Capillarity theory for the fly‐casting mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:2746–2750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Huang Y, Liu Z. Kinetic advantage of intrinsically disordered proteins in coupled folding‐binding process: A critical assessment of the “fly‐casting” mechanism. J Mol Biol. 2009;393:1143–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Iesmantavicius V, Dogan J, Jemth P, Teilum K, Kjaergaard M. Helical propensity in an intrinsically disordered protein accelerates ligand binding. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53:1548–1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Rogers JM, Wong CT, Clarke J. Coupled folding and binding of the disordered protein PUMA does not require particular residual structure. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:5197–5200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Arai M, Sugase K, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Conformational propensities of intrinsically disordered proteins influence the mechanism of binding and folding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:9614–9619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Schmidtgall B, Chaloin O, Bauer V, Sumyk M, Birck C, Torbeev V. Dissecting mechanism of coupled folding and binding of an intrinsically disordered protein by chemical synthesis of conformationally constrained analogues. Chem Commun. 2017;53:7369–7372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Liu X, Chen J, Chen J. Residual structure accelerates binding of intrinsically disordered ACTR by promoting efficient folding upon encounter. J Mol Biol. 2019;431:422–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Umezawa K, Ohnuki J, Higo J, Takano M. Intrinsic disorder accelerates dissociation rather than association. Proteins. 2016;84:1124–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Narasumani M, Harrison PM. Bioinformatical parsing of folding‐on‐binding proteins reveals their compositional and evolutionary sequence design. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Dogan J, Jonasson J, Andersson E, Jemth P. Binding rate constants reveal distinct features of disordered protein domains. Biochemistry. 2015;54:4741–4750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Chemes LB, Sanchez IE, de Prat‐Gay G. Kinetic recognition of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor by a specific protein target. J Mol Biol. 2011;412:267–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Shammas SL, Travis AJ, Clarke J. Allostery within a transcription coactivator is predominantly mediated through dissociation rate constants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:12055–12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Lindstrom I, Dogan J. Native hydrophobic binding interactions at the transition state for association between the TAZ1 domain of CBP and the disordered TAD‐STAT2 are not a requirement. Biochemistry. 2017;56:4145–4153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Ganguly D, Otieno S, Waddell B, Iconaru L, Kriwacki RW, Chen J. Electrostatically accelerated coupled binding and folding of intrinsically disordered proteins. J Mol Biol. 2012;422:674–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Papadakos G, Sharma A, Lancaster LE, et al. Consequences of inducing intrinsic disorder in a high‐affinity protein‐protein interaction. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:5252–5255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Rogers JM, Steward A, Clarke J. Folding and binding of an intrinsically disordered protein: Fast, but not “diffusion‐limited”. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:1415–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Ou L, Matthews M, Pang X, Zhou HX. The dock‐and‐coalesce mechanism for the association of a WASP disordered region with the Cdc42 GTPase. FEBS J. 2017;284:3381–3391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Aberg E, Karlsson OA, Andersson E, Jemth P. Binding kinetics of the intrinsically disordered p53 family transactivation domains and MDM2. J Phys Chem B. 2018;122:6899–6905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Shammas SL, Travis AJ, Clarke J. Remarkably fast coupled folding and binding of the intrinsically disordered transactivation domain of cMyb to CBP KIX. J Phys Chem B. 2013;117:13346–13356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Gallagher E, Song JM, Menon A, Mishra L, Chmiel AF, Garner AL. Consideration of binding kinetics in the design of stapled peptide mimics of the disordered proteins eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E)‐binding protein 1 (4E‐BP1) and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G (eIF4G). J Med Chem. 2019;62:4967–4978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Chu X, Wang Y, Gan L, et al. Importance of electrostatic interactions in the association of intrinsically disordered histone chaperone Chz1 and histone H2A.Z‐H2B. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8:e1002608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Ganguly D, Zhang W, Chen J. Electrostatically accelerated encounter and folding for facile recognition of intrinsically disordered proteins. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9:e1003363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Pang X, Zhou HX. Mechanism and rate constants of the Cdc42 GTPase binding with intrinsically disordered effectors. Proteins. 2016;84:674–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Tsai MY, Zheng W, Balamurugan D, et al. Electrostatics, structure prediction, and the energy landscapes for protein folding and binding. Protein Sci. 2016;25:255–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Chu WT, Clarke J, Shammas SL, Wang J. Role of non‐native electrostatic interactions in the coupled folding and binding of PUMA with mcl‐1. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13:e1005468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Sturzenegger F, Zosel F, Holmstrom ED, et al. Transition path times of coupled folding and binding reveal the formation of an encounter complex. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Kim JY, Meng F, Yoo J, Chung HS. Diffusion‐limited association of disordered protein by non‐native electrostatic interactions. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Dunker AK, Oldfield CJ. Back to the future: Nuclear magnetic resonance and bioinformatics studies on intrinsically disordered proteins. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;870:1–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Mollica L, Bessa LM, Hanoulle X, Jensen MR, Blackledge M, Schneider R. Binding mechanisms of intrinsically disordered proteins: Theory, simulation, and experiment. Front Mol Biosci. 2016;3:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Dogan J, Gianni S, Jemth P. The binding mechanisms of intrinsically disordered proteins. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2014;16:6323–6331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Weikl TR, von Deuster C. Selected‐fit versus induced‐fit protein binding: Kinetic differences and mutational analysis. Proteins. 2009;75:104–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Vogt AD, Di Cera E. Conformational selection or induced fit? A critical appraisal of the kinetic mechanism. Biochemistry. 2012;51:5894–5902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Gianni S, Dogan J, Jemth P. Distinguishing induced fit from conformational selection. Biophys Chem. 2014;189:33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Paul F, Weikl TR. How to distinguish conformational selection and induced fit based on chemical relaxation rates. PLoS Comput Biol. 2016;12:e1005067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Chakraborty P, Di Cera E. Induced fit is a special case of conformational selection. Biochemistry. 2017;56:2853–2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Hammes GG, Chang YC, Oas TG. Conformational selection or induced fit: A flux description of reaction mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13737–13741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Greives N, Zhou HX. Both protein dynamics and ligand concentration can shift the binding mechanism between conformational selection and induced fit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:10197–10202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Daniels KG, Tonthat NK, McClure DR, et al. Ligand concentration regulates the pathways of coupled protein folding and binding. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:822–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Zhou HX. From induced fit to conformational selection: A continuum of binding mechanism controlled by the timescale of conformational transitions. Biophys J. 2010;98:L15–L17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Liu C, Wang T, Bai Y, Wang J. Electrostatic forces govern the binding mechanism of intrinsically disordered histone chaperones. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0178405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Daniels KG, Suo Y, Oas TG. Conformational kinetics reveals affinities of protein conformational states. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:9352–9357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Weikl TR, Paul F. Conformational selection in protein binding and function. Protein Sci. 2014;23:1508–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Choi UB, Sanabria H, Smirnova T, Bowen ME, Weninger KR. Spontaneous switching among conformational ensembles in intrinsically disordered proteins. Biomolecules. 2019;9:114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Salvi N, Abyzov A, Blackledge M. Multi‐timescale dynamics in intrinsically disordered proteins from NMR relaxation and molecular simulation. J Phys Chem Lett. 2016;7:2483–2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Jain N, Narang D, Bhasne K, et al. Direct observation of the intrinsic backbone torsional mobility of disordered proteins. Biophys J. 2016;111:768–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Soranno A, Longhi R, Bellini T, Buscaglia M. Kinetics of contact formation and end‐to‐end distance distributions of swollen disordered peptides. Biophys J. 2009;96:1515–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Rogers JM, Oleinikovas V, Shammas SL, et al. Interplay between partner and ligand facilitates the folding and binding of an intrinsically disordered protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:15420–15425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Gianni S, Morrone A, Giri R, Brunori M. A folding‐after‐binding mechanism describes the recognition between the transactivation domain of c‐Myb and the KIX domain of the CREB‐binding protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;428:205–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Gianni S, Dogan J, Jemth P. Coupled binding and folding of intrinsically disordered proteins: What can we learn from kinetics? Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2016;36:18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Dogan J, Schmidt T, Mu X, Engstrom A, Jemth P. Fast association and slow transitions in the interaction between two intrinsically disordered protein domains. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:34316–34324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Dosnon M, Bonetti D, Morrone A, et al. Demonstration of a folding after binding mechanism in the recognition between the measles virus NTAIL and X domains. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10:795–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Espinoza‐Fonseca LM. Reconciling binding mechanisms of intrinsically disordered proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;382:479–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Schneider R, Maurin D, Communie G, et al. Visualizing the molecular recognition trajectory of an intrinsically disordered protein using multinuclear relaxation dispersion NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:1220–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Lindstrom I, Andersson E, Dogan J. The transition state structure for binding between TAZ1 of CBP and the disordered Hif‐1a CAD. Sci Rep. 2018;8:7872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Toto A, Camilloni C, Giri R, Brunori M, Vendruscolo M, Gianni S. Molecular recognition by templated folding of an intrinsically disordered protein. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Giri R, Morrone A, Toto A, Brunori M, Gianni S. Structure of the transition state for the binding of c‐Myb and KIX highlights an unexpected order for a disordered system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:14942–14947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Dahal L, Kwan TOC, Shammas SL, Clarke J. pKID binds to KIX via an unstructured transition state with nonnative interactions. Biophys J. 2017;113:2713–2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Crabtree MD, Mendonca C, Bubb QR, Clarke J. Folding and binding pathways of BH3‐only proteins are encoded within their intrinsically disordered sequence, not templated by partner proteins. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:9718–9723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Toto A, Gianni S. Mutational analysis of the binding‐induced folding reaction of the mixed‐lineage leukemia protein to the KIX domain. Biochemistry. 2016;55:3957–3962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Haq SR, Chi CN, Bach A, et al. Side‐chain interactions form late and cooperatively in the binding reaction between disordered peptides and PDZ domains. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Bachmann A, Wildemann D, Praetorius F, Fischer G, Kiefhaber T. Mapping backbone and side‐chain interactions in the transition state of a coupled protein folding and binding reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3952–3957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Bonetti D, Troilo F, Toto A, Brunori M, Longhi S, Gianni S. Analyzing the folding and binding steps of an intrinsically disordered protein by protein engineering. Biochemistry. 2017;56:3780–3786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Hill SA, Kwa LG, Shammas SL, Lee JC, Clarke J. Mechanism of assembly of the non‐covalent spectrin tetramerization domain from intrinsically disordered partners. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:21–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Karlsson E, Andersson E, Dogan J, Gianni S, Jemth P, Camilloni C. A structurally heterogeneous transition state underlies coupled binding and folding of disordered proteins. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:1230–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Dogan J, Mu X, Engstrom A, Jemth P. The transition state structure for coupled binding and folding of disordered protein domains. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Karlsson OA, Chi CN, Engstrom A, Jemth P. The transition state of coupled folding and binding for a flexible beta‐finger. J Mol Biol. 2012;417:253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Zhou HX, Pang X, Lu C. Rate constants and mechanisms of intrinsically disordered proteins binding to structured targets. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2012;14:10466–10476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Wu D, Zhou HX. Designed mutations alter the binding pathways of an intrinsically disordered protein. Sci Rep. 2019;9:6172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Staneva I, Huang Y, Liu Z, Wallin S. Binding of two intrinsically disordered peptides to a multi‐specific protein: A combined Monte Carlo and molecular dynamics study. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8:e1002682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Bonetti D, Troilo F, Brunori M, Longhi S, Gianni S. How robust is the mechanism of folding‐upon‐binding for an intrinsically disordered protein? Biophys J. 2018;114:1889–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Ellis RJ, Minton AP. Cell biology: Join the crowd. Nature. 2003;425:27–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Zhou HX, Rivas G, Minton AP. Macromolecular crowding and confinement: Biochemical, biophysical, and potential physiological consequences. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:375–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Fonin AV, Darling AL, Kuznetsova IM, Turoverov KK, Uversky VN. Intrinsically disordered proteins in crowded milieu: When chaos prevails within the cellular gumbo. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75:3907–3929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Kuznetsova IM, Turoverov KK, Uversky VN. What macromolecular crowding can do to a protein. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:23090–23140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Soranno A, Koenig I, Borgia MB, et al. Single‐molecule spectroscopy reveals polymer effects of disordered proteins in crowded environments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:4874–4879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Kang H, Pincus PA, Hyeon C, Thirumalai D. Effects of macromolecular crowding on the collapse of biopolymers. Phys Rev Lett. 2015;114:068303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. Miller CM, Kim YC, Mittal J. Protein composition determines the effect of crowding on the properties of disordered proteins. Biophys J. 2016;111:28–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161. Bai J, Liu M, Pielak GJ, Li C. Macromolecular and small molecular crowding have similar effects on alpha‐synuclein structure. Chem Phys Chem. 2017;18:55–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162. Balu R, Mata JP, Knott R, et al. Effects of crowding and environment on the evolution of conformational ensembles of the multi‐stimuli‐responsive intrinsically disordered protein, Rec1‐resilin: A small‐angle scattering investigation. J Phys Chem B. 2016;120:6490–6503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163. Goldenberg DP, Argyle B. Minimal effects of macromolecular crowding on an intrinsically disordered protein: A small‐angle neutron scattering study. Biophys J. 2014;106:905–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164. Szasz CS, Alexa A, Toth K, Rakacs M, Langowski J, Tompa P. Protein disorder prevails under crowded conditions. Biochemistry. 2011;50:5834–5844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165. Dedmon MM, Patel CN, Young GB, Pielak GJ. FlgM gains structure in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12681–12684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166. Cook EC, Creamer TP. Calcineurin in a crowded world. Biochemistry. 2016;55:3092–3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167. Rusinga FI, Weis DD. Soft interactions and volume exclusion by polymeric crowders can stabilize or destabilize transient structure in disordered proteins depending on polymer concentration. Proteins. 2017;85:1468–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168. Flaugh SL, Lumb KJ. Effects of macromolecular crowding on the intrinsically disordered proteins c‐Fos and p27Kip1 . Biomacromolecules. 2001;2:538–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169. Wang Y, Benton LA, Singh V, Pielak GJ. Disordered protein diffusion under crowded conditions. J Phys Chem Lett. 2012;3:2703–2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170. Li CG, Charlton LM, Lakkavaram A, et al. Differential dynamical effects of macromolecular crowding on an intrinsically disordered protein and a globular protein: Implications for in‐cell NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6310–6311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171. Banks A, Qin S, Weiss KL, Stanley CB, Zhou HX. Intrinsically disordered protein exhibits both compaction and expansion under macromolecular crowding. Biophys J. 2018;114:1067–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172. Hoffman L, Wang X, Sanabria H, Cheung MS, Putkey JA, Waxham MN. Relative cosolute size influences the kinetics of protein‐protein interactions. Biophys J. 2015;109:510–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173. Kim YC, Bhattacharya A, Mittal J. Macromolecular crowding effects on coupled folding and binding. J Phys Chem B. 2014;118:12621–12629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174. Olsen JG, Teilum K, Kragelund BB. Behaviour of intrinsically disordered proteins in protein‐protein complexes with an emphasis on fuzziness. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74:3175–3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175. Fuxreiter M. Fuzziness in protein interactions‐a historical perspective. J Mol Biol. 2018;430:2278–2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176. Lindstrom I, Dogan J. Dynamics, conformational entropy, and frustration in protein‐protein interactions involving an intrinsically disordered protein domain. ACS Chem Biol. 2018;13:1218–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177. Borgia A, Borgia MB, Bugge K, et al. Extreme disorder in an ultrahigh‐affinity protein complex. Nature. 2018;555:61–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178. Tompa P, Fuxreiter M. Fuzzy complexes: Polymorphism and structural disorder in protein‐protein interactions. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179. Sharma R, Raduly Z, Miskei M, Fuxreiter M. Fuzzy complexes: Specific binding without complete folding. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:2533–2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180. Graham TA, Ferkey DM, Mao F, Kimelman D, Xu W. Tcf4 can specifically recognize beta‐catenin using alternative conformations. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:1048–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181. Smet‐Nocca C, Wieruszeski JM, Chaar V, Leroy A, Benecke A. The thymine‐DNA glycosylase regulatory domain: Residual structure and DNA binding. Biochemistry. 2008;47:6519–6530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182. Liu Y, Matthews KS, Bondos SE. Internal regulatory interactions determine DNA binding specificity by a Hox transcription factor. J Mol Biol. 2009;390:760–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183. Wang Y, Fisher JC, Mathew R, et al. Intrinsic disorder mediates the diverse regulatory functions of the Cdk inhibitor p21. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:214–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184. Miskei M, Gregus A, Sharma R, Duro N, Zsolyomi F, Fuxreiter M. Fuzziness enables context dependence of protein interactions. FEBS Lett. 2017;591:2682–2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185. Toth‐Petroczy A, Simon I, Fuxreiter M, Levy Y. Disordered tails of homeodomains facilitate DNA recognition by providing a trade‐off between folding and specific binding. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:15084–15085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186. Fuxreiter M. Fold or not to fold upon binding ‐ does it really matter? Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2019;54:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187. Banani SF, Lee HO, Hyman AA, Rosen MK. Biomolecular condensates: Organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18:285–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 188. Wu H, Fuxreiter M. The structure and dynamics of higher‐order assemblies: Amyloids, signalosomes, and granules. Cell. 2016;165:1055–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189. Li P, Banjade S, Cheng HC, et al. Phase transitions in the assembly of multivalent signalling proteins. Nature. 2012;483:336–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 190. Wu X, Cai Q, Shen Z, et al. RIM and RIM‐BP form presynaptic active‐zone‐like condensates via phase separation. Mol Cell. 2019;73:971–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 191. Zeng M, Shang Y, Araki Y, Guo T, Huganir RL, Zhang M. Phase transition in postsynaptic densities underlies formation of synaptic complexes and synaptic plasticity. Cell. 2016;166:1163–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 192. Zeng M, Chen X, Guan D, et al. Reconstituted postsynaptic density as a molecular platform for understanding synapse formation and plasticity. Cell. 2018;174:1172–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 193. Mitrea DM, Cika JA, Guy CS, et al. Nucleophosmin integrates within the nucleolus via multi‐modal interactions with proteins displaying R‐rich linear motifs and rRNA. Elife. 2016;5:e13571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 194. Darling AL, Uversky VN. Intrinsic disorder and posttranslational modifications: The darker side of the biological dark matter. Front Genet. 2018;9:158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 195. Pejaver V, Hsu WL, Xin F, Dunker AK, Uversky VN, Radivojac P. The structural and functional signatures of proteins that undergo multiple events of post‐translational modification. Protein Sci. 2014;23:1077–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 196. Bah A, Vernon RM, Siddiqui Z, et al. Folding of an intrinsically disordered protein by phosphorylation as a regulatory switch. Nature. 2015;519:106–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 197. Levy R, Gregory E, Borcherds W, Daughdrill G. p53 phosphomimetics preserve transient secondary structure but reduce binding to Mdm2 and MdmX. Biomolecules. 2019;9:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 198. Joo Y, Schumacher B, Landrieu I, et al. Involvement of 14‐3‐3 in tubulin instability and impaired axon development is mediated by tau. FASEB J. 2015;29:4133–4144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 199. Zhao L, Ouyang Y, Li Q, Zhang Z. Modulation of p53 N‐terminal transactivation domain 2 conformation ensemble and kinetics by phosphorylation. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2019;1–11. 10.1080/07391102.2019.1637784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 200. Romero PR, Zaidi S, Fang YY, et al. Alternative splicing in concert with protein intrinsic disorder enables increased functional diversity in multicellular organisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8390–8395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 201. Weatheritt RJ, Davey NE, Gibson TJ. Linear motifs confer functional diversity onto splice variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:7123–7131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 202. Trudeau T, Nassar R, Cumberworth A, Wong ET, Woollard G, Gsponer J. Structure and intrinsic disorder in protein autoinhibition. Structure. 2013;21:332–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 203. Buljan M, Chalancon G, Eustermann S, et al. Tissue‐specific splicing of disordered segments that embed binding motifs rewires protein interaction networks. Mol Cell. 2012;46:871–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]