Abstract

In recent years, sociological research investigating grandparent effects in three-generation social mobility has proliferated, mostly focusing on the question of whether grandparents have a direct effect on their grandchildren’s social attainment. This study hypothesizes that prior research has overlooked family structure as an important factor that moderates grandparents’ direct effects. Capitalizing on a counterfactual causal framework and multigenerational data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, this study examines the direct effect of grandparents’ years of education on grandchildren’s years of educational attainment and heterogeneity in the effects associated with family structure. The results show that, for both African Americans and whites, grandparent effects are the strongest for grandchildren who grew up in two-parent families, followed by those in single-parent families with divorced parents. The weakest effects were marked in single-parent families with unmarried parents. These findings suggest that the increasing diversity of family forms has led to diverging social mobility trajectories for families across generations.

Keywords: Multigenerational mobility, grandparents, family structure, education

Introduction

In recent years, social scientists in general—and sociologists in particular—have expressed a growing interest in social mobility of families across three or more generations (Mare 2011, 2014; Pfeffer 2014; Sharkey and Elwert 2011; Solon 2014; Wightman and Danziger 2014). An intriguing question that has perplexed multigenerational researchers is whether we underestimate the legacy of family advantages or disadvantages if we focus only on two generations in families. One simple and important way to answer this question is to investigate whether grandparents’ social statuses directly contribute to the social successes of their grandchildren, independently of parents’ influences (Chan and Boliver 2013; Erola and Moisio 2007; Hertel and Groh-Samberg 2014; Jæger 2012; Warren and Hauser 1997; Zeng and Xie 2014). These studies, however, exclusively focus on a comparison of the effects of grandparents to those of parents, rather than variation in the grandparent effects across subgroups in a society. To fill this gap in our knowledge, this study situates the question of multigenerational social mobility in the context of increasing family instability and complexity (McLanahan and Percheski 2008; Tach 2015), which may have led to a diversity of grandparent effects across different types of family structures.

The present study uses educational mobility as an example to examine (1) the direct effect of grandparents’ education on grandchildren’s education and (2) variations in the direct effect associated with childhood family structures experienced by both parent and grandchild generations in the United States. Borrowing terms from causal mediation analysis (Baron and Kenny 1986; Pearl 2014), I distinguish between two effects that explain the role of family structure in three-generation social mobility, mediation and moderation, the latter of which is the focus of the present study. The mediation effect of family structure refers to the way in which family structure serves as a vehicle in transmitting social advantages or disadvantages across generations. Such an effect, also known as the indirect effects of grandparents, has been well documented in the literature (e.g., Amato 2005; Aquilino 1996; Astone and McLanahan 1991; Duncan and Duncan 1969; Furstenberg and Cherlin 1991; Ginther and Pollak 2004; McLanahan and Sandefur 1994; Seltzer 1994). The focus of this study is to investigate the moderation effect of family structure, a largely understudied effect that refers to the role of family structure in modifying the direct influences of grandparents. Specifically, I examine whether the direct effect of grandparents is the same, greater, or smaller in two-parent families than in families that experience single parenthood in prior generations.

Although many definitions of family structures appear in existing studies, I define two-parent families as those in which both parents were married for the entirety of the offspring’s childhood. I consider all other types of family structure to be single-parent families in which one biological parent was often absent from the household and the other was widowed, divorced, separated, remarried, or never married. Evidence has shown that by the early 2000s, nearly one in two children lived in a single-parent household at some point before he or she reached age 18 (Ellwood and Jencks 2004). To address heterogeneity within single-parent families, I further differentiate between two subgroups: single-parent families in which parents were married at the time of the birth of their child and in which children were born outside of marriage. While the first subgroup constitutes the majority of single-parent families, the second subgroup has grown rapidly in recent years as a result of the “deinstitutionalization of marriage” (Cherlin 2004).

Unlike previous studies that focus only on the effect of childhood family structure on one’s educational attainment, I also investigate the effect of parents’ childhood family structures. The rationale is that family history of hardship may include not only family circumstances during the childhood of the present generation but also those of previous generations (Sharkey and Elwert 2011; Wightman and Danziger 2014). If parents who grew up in single-parent households raise their children in ways similar to how they were raised themselves, or if grandparents who were single parents while raising their own children are also involved in raising their grandchildren, family structure may have a lagged effect on the social outcomes of subsequent generations. By simultaneously considering the trajectories of family structures and the trajectories of families’ socioeconomic statuses, this study provides a fuller picture of the relationship between family structure and the reproduction of social statuses across generations.

To address the causal effects of grandparents, the present study builds upon a graphical modeling framework and specifies assumptions to help identify circumstances under which a statistical estimate linking grandparents’ and grandchildren’s education can be interpreted as causal (Morgan and Winship 2014; Pearl 2009). I adapt the hierarchical linear model with inverse probability weights to estimate the direct effects of grandparents in models with time-varying characteristics of family members across generations. Drawing on data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, this study shows substantial heterogeneity in grandparent effects associated with family structure. The formation of single-parent families does not only truncate relations between offspring and their noncustodial parents and grandparents (Cherlin and Furstenberg 1986; Furstenberg 1990), but also reduces similarity in educational status across generations. Specifically, grandparent effects are the strongest in families where grandchildren grew up with two parents, followed by the effects in single-parent families with divorced parents, with the weakest effects occurring in families with unmarried parents. The childhood family structure of parents has no effect on the grandparent effect on grandchildren. A further analysis stratified by race shows that these results hold for both African Americans and whites. Overall, findings from this study suggest that overlooking the growing complexity of family forms would oversimplify our understanding of multigenerational social mobility processes. The growth of single-parent families has not only led to “diverging destinies” of U.S. children as suggested by McLanahan (2004) but also diverging mobility trajectories of U.S. families across multiple generations.

Grandparent Effects and The Markovian Assumption

Sociological studies on intergenerational social mobility predominantly focus on parent-offspring pairs (e.g., Blau and Duncan 1967; Featherman and Hauser 1978; Sewell and Hauser 1975). This two-generation approach suffices to explain mobility in three or more generations if grandparents do not directly transmit socioeconomic status to their grandchildren, bypassing the parent generation (Mare 2011). Rather, the parent generation serves as the intermediary: Grandparents influence their own children, who then guide and rear the grandchildren. Therefore, family influences across three generations amount to the sum of the direct influences over two consecutive generations, without lagged influences from grandparents to grandchildren—a representation of a Markov chain process in social mobility, also known as the Markovian assumption (Bartholomew 1982; Hodge 1966; Mare 2011).

Whether three-generation mobility is Markovian or not has important implications for our understanding of the persistence of social inequality along family lines. If we observe a direct effect of grandparents (i.e., a non-Markovian mobility regime), then families in favorable social positions are likely to pass on their status advantages to their progeny, whereas offspring from historically disadvantaged families face long-term difficulties escaping from their family histories. As success breeds success or poverty breeds poverty, families tend to perpetuate their high or low status across generations. A society with strong non-Markovian grandparent effects thus may offer fewer mobility opportunities for families to rise from rags to riches over generations than a society with a Markovian mobility regime.

In recent years, a growing number of empirical studies have tested the Markovian assumption about the grandparent effect using multigenerational data. Results from prior studies are mixed. Two studies, both using data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Studies, report that grandparents overall do not directly influence their grandchildren’s educational attainment (Warren and Hauser 1997; Jæger 2012). By contrast, several studies drawing on evidence from the United Kingdom (Chan and Boliver 2013), China (Zeng and Xie 2014), and nationally representative data from the United States (Hertel and Groh-Samberg 2014; Wightman and Danziger 2014) present a challenge to the Markovian assumption by showing that grandparents’ socioeconomic status can directly contribute to the socioeconomic success of their grandchildren, independently of the parent generation.

Existing studies, however, focus primarily on the average effect of grandparents in a population, leaving aside the possibility of varying grandparent effects across social and demographic subpopulations. The present study represents an explicit effort in exploring this possibility by examining heterogeneity in grandparent effects associated with family forms. I chose educational attainment as the outcome variable of interest because education is the first source of stratification that one experiences in adulthood, and it has important implications for social circumstances over one’s life course as well as mobility opportunities for one’s offspring and potentially for subsequent generations. A considerable body of scholarship has documented trends in intergenerational associations in education in the United States and variations in the associations across societies (e.g., Fischer and Hout 2006; Hout and DiPrete 2006). These estimates of parent effects can be used as benchmarks for the estimates of grandparent effects in three-generation mobility. While the expansion of higher education has fostered growth in social mobility (Goldin and Katz 2008), inequality in educational mobility persists: the overall correlation in education between parents and offspring has remained stable at about 0.4 since the 1960s (Hout and Janus 2011). Such stability, however, is misleading because it is an average over various subgroups of family forms, each of which may have different correlations. If the trends differ by family forms, the growth of single-parent families has contributed a composition effect to the overall trend in intergenerational inequality by giving more weight to single-parent families in more recent years than in the past (e.g., Bloome 2014; Maralani 2013; Mare 1997; Musick and Mare 2004). In this case, a relatively stable overall correlation over time may have concealed substantial heterogeneity among subgroups with different family structures.

Theoretical Framework

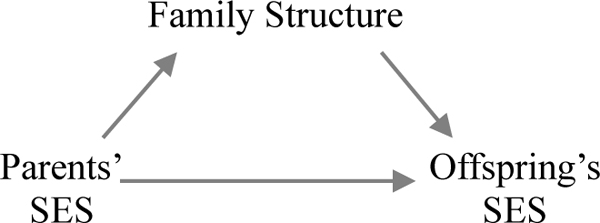

This paper distinguishes between two mechanisms through which family structure shapes the mobility trajectories of families: (1) as a mediator, which intervenes in the transmission of socioeconomic status from grandparents to parents and grandchildren, and (2) as a moderator, which interacts with parents’ and grandparents’ socioeconomic characteristics and modifies the direct effects of grandparents and parents on grandchildren. If we decompose the total effect of grandparents into an indirect and a direct effect, the mediation effect examines the proportion of the total effect of grandparents that is mediated by family structure, namely, the indirect effect of grandparents. By contrast, the moderation effect, the focus of this paper, examines the variation in the direct effect of grandparents across different family forms. In practice, these two effects are sometimes mistakenly used interchangeably, so I summarize their statistical differences in Table 1 and discuss their substantive differences below.

Table 1.

Summary of the Two Mechanisms Through Which Family Structure Shapes the Mobility Trajectories of Families

| The Role of Family Structure |

Conceptual Interpretation a | Graphic Illustrations | Exemplary Work based on Two-Generation Mobility |

Focus of the Present Study? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator | A mediator is a third variable that accounts for the relation between an independent variable and a dependent variable. |  |

e.g., Duncan and Duncan (1969); McLanahan and Sandefur (1994) | No |

| Moderator | A moderator is a third variable that “affects the direction and/or strength of the relation” between an independent variable and a dependent variable. |  |

e.g., Biblarz and Raftery (1993), Martin (2012) | Yes |

Notes:

Definitions provided by Baron and Kenny (1986).

Family Structure: A Mediator in Social Mobility

Family structure mediates the educational resemblance between parents and offspring because the formation of family structure is often a consequence of parents’ educational attainment and a cause of children’s educational outcomes. On the one hand, less-educated individuals are more likely to experience premarital birth, cohabitation, and divorce, and raise their children in a single-parent household (Bumpass and Lu 2000; Raley and Bumpass 2003). On the other hand, children who grew up with a single parent are less likely to graduate from high school, attend college, and complete college compared to their two-parent counterparts (e.g., Amato 2005; Aquilino 1996; Duncan and Duncan 1969; Ginther and Pollak 2004; McLanahan and Sandefur 1994; Sandefur and Wells 1999; Seltzer 1994). To further complicate the matter, the intervening role of family structure may differ according to the timing of family disruption, the number of disruptions and remarriages, and the duration of different types of family forms (Furstenberg, Hoffman, and Shrestha 1995; Krein and Beller 1988; Wojtkiewicz 1993). As a result, family structure mediates the total effect of individuals’ social origins on their social destinations, creating extra barriers to those born into low social status families for achieving upward mobility.

There are several major explanations for the adverse effect of the single-parent family on children’s educational outcomes. First, the economic deprivation explanation states that family disruption depletes economic resources available to children, not only because parents no longer pool resources but also because they often experience a job loss or slow income growth following divorce (Brand and Thomas 2014; Thomson, Hanson, and McLanahan 1994). The second explanation suggests that family disruption often changes intergenerational relationships. Single parents, especially mothers who continue to live with their children after the family disruption, are often exposed to stressful circumstances, thus becoming less effective in terms of parenting styles, which in turn has a negative impact on children’s academic performance (Amato 2005). Instead of focusing on the role of mothers, the third explanation stresses the consequences of the absence of fathers (Seltzer 1991) or “pathology of matriarchy” (Duncan and Duncan 1969). According to this view, the absence of fathers as role models in female-headed families affects the functioning of families, especially in children’s socialization. Lastly, some research has weighed in with arguments about unobserved selection mechanisms—factors that influence both family disruption and children’s educational outcomes, such as parental conflict and antecedent attitudes toward marriage and childrearing—that generate a spurious relationship between single parenthood and children’s wellbeing (Fomby and Cherlin 2007; Sandefur and Wells 1999). These explanations may operate for three-generation mobility as well. Family structure may intervene in the educational transmission from grandparents to parents to grandchildren, leading to cumulative advantages for children whose families have maintained intactness in family structure across two generations. Compared to their two-parent counterparts, parents who grew up with a single parent may be more likely to receive less education, become single parents themselves, and raise their children in ways similar to how they were raised themselves (Seltzer 1994; Thornton 1991; Wolfinger 1999; Wu and Martinson 1993).

Family Structure: A Moderator in Social Mobility

The focus of this study is the mechanism of family structure as a moderator in intergenerational mobility, which is far less studied than the mediation effect of family structure. When serving as a moderator, family structure interacts with the direct effects of grandparents on their children and grandchildren, leading to varying degrees of direct effects across family forms. Compared to a mediator that explains the indirect effect of parents on offspring, a moderator illustrates why parents have a stronger direct effect on offspring under some circumstances than others. Because the moderation effect emphasizes the variation in the direct effect of a cause on an outcome, it is also known as “effect heterogeneity” or “effect modification” (Hong 2015; VanderWeele 2015).

From a two-generation perspective, only a handful of studies have documented the role of family structure as a moderator in the intergenerational mobility of occupational status (Biblarz and Raftery 1993, 1999; Biblarz, Raftery, and Bucur 1997), educational achievement (Martin 2012), and income (Björklund and Chadwick 2003). Conclusions from these studies concur that families with two biological parents facilitate the intergenerational transmission of socioeconomic status, resulting in a stronger parent effect in two-parent families than in alternative family forms. However, whether this conclusion can be extended to the case of three-generation mobility remains an open question. Results from the limited amount of research on this question are mixed. Below, I summarize previous empirical findings into three hypotheses based on their prediction about the relative strength of the grandparent effect in one-parent and two-parent families.

Stronger Grandparent Effects in Single-Parent Families.

Family research characterizes typical grandparents in single-parent families as “rescuers” or “family stabilizers” who raise their grandchildren during episodes of need, in contrast to grandparents in two-parent families who visit their grandchildren regularly but provide limited services (Bengtson 2001; Hogan, Eggebeen, and Clogg 1993; Hunter and Taylor 1998). With respect to educational outcomes, while children exposed to single-parent families fare worse than do their two-parent counterparts (McLanahan and Sandefur 1994), the “latent safety net” provided by grandparents as well as other kin often attenuate the impact of family instability (Bengtson 2001). Many grandparents provide financial, emotional, and practical support to their grandchildren on a regular basis, or even become their custodians (Fuller-Thomson, Minkler, and Driver 1997; King and Elder 1997). Grandchildren may benefit from their grandparents’ involvement, which compensates for diminished parental economic resources and helps them cope with stresses caused by parents’ divorce or separation (Deleire and Kalil 2002; Denham and Smith 1989; Hayslip and Kaminski 2005). As a result, family crises may activate the grandparent effect, generating a greater resemblance in social status between grandparents and grandchildren in single-parent families than in two-parent families.

Stronger Grandparent Effects in Two-Parent Families.

Most studies on grandparents in single-parent families tend to focus on support from maternal grandparents, but fail to emphasize diminished grandparental resources due to attenuated or broken paternal intergenerational ties following parents’ divorce (Silverstein and Bengtson 1997). Because of intact kinship ties, grandchildren in two-parent families potentially get exposure to all four of their grandparents, in effect having access to a greater total amount of support. By contrast, grandchildren in single-parent families may drift apart from two of their grandparents, in some cases losing the support of the most helpful grandparents. Even if the quantity of support provided by grandparents does not vary by family structure, the quality of support often does. Grandparents in two-parent families may invest more time and money in grandchildren’s learning and education-related activities, whereas grandparents in single-parent families are often more involved in practical support such as helping with household chores, chauffeuring, and babysitting (Kaushal, Magnuson, and Waldfogel 2011; Sarkisian and Gerstel 2004). Furthermore, stronger grandparent effects in two-parent families may result from family characteristics that are associated with intact families, such as more traditional cultural values, cohesive kinship relationships, and institutionalized family ties. These family characteristics may reduce the risk of divorce, nonmarital childbearing, or cohabitation, while at the same time facilitating children’s educational performance in two-parent families.

No Variations in Grandparent Effects Across Family Structures.

Beyond the aforementioned two hypotheses, it is also possible that the grandparent effect does not interact with family structures, such that the multigenerational persistence of educational status is the same across all family forms. Most studies on grandparenthood have suggested that the relationship between American grandparents and their grandchildren is enormously heterogeneous, ranging from extremely aloof to highly influential (Casper and Bianchi 2001). Cherlin and Furstenberg (1986) characterized five grandparenting styles as detached, passive, supportive, authoritative, and influential, but they found that none of these styles are dominant in the population. It is possible that grandparenting styles are independent of family structure so that single-parent and two-parent families are equally likely to have very influential or unimportant grandparents. Thus, on average, the grandparent effect on grandchildren within each type of family structure is similar.

The Role of Race

The relationship between family structure and the direct effect of grandparents may also be intertwined with race. Previous social mobility studies have well documented that intergenerational inheritance of social status is stronger and more homogeneous for whites than for African Americans (e.g., Blau and Duncan 1967: 207–227; Duncan 1968; Featherman and Hauser 1976; Hout 1984). It is plausible that variations in grandparents’ effects between single-parent and two-parent families are also more striking among African Americans than whites, in part because grandparents’ support is more constrained by needs and resources for African Americans. Most African American grandparents have more grandchildren but fewer financial and human capital resources. Hogan et al. (1993) show that on average, African American parents receive less assistance than whites from grandparents, because of the higher number of siblings who compete for grandparental support. The weaker grandparent effect may also be attributed to the effectiveness of parenting skills among low-income African American families or to race-specific social barriers—such as economic inequality, residential segregation, parental unemployment and incarceration, or even discrimination in the educational system—that hinder African American grandparents from transmitting their educational status to grandchildren. For these reasons, I stratify my analysis by race in assessing the role of family structure that moderates the direct effect of grandparents on grandchildren.

Data and Variables

Data

The analysis draws upon data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID, 1968–2013), an ongoing longitudinal survey of roughly 5,000 American families (PSID Main Interview User Manual 2013). The PSID project started with over 18,000 individuals in 1968 and covered more than 70,000 individuals from 1968 to 2013. The study follows targeted respondents according to a genealogical design. To create a multigenerational sample, I link PSID respondents from non-immigrant families with their parents and grandparents. For most families, only one set of parents and grandparents (either paternal or maternal) are available, because PSID only follows family members of the original sample in 1968 and their progeny, but not spouses who later marry into a PSID household. To obtain more information about the grandparents, I rely on retrospective questions for the household heads and wives about their parents’ educational information. However, if a grandchild was born outside of marriage and his or her parents lived in a PSID household together for less than one year, or if an individual’s parents had a very short marriage, information for one parent, often the father, is likely to be missing. Therefore, the analytical sample includes more individuals with complete information for mothers and maternal grandparents than for fathers and paternal grandparents.

The final analytical sample is restricted to grandchildren who are aged 25 to 65 years old in the most recent wave of the survey in 2013 and with nonmissing data on all education and family structure variables. The sample includes 2,525 African American grandchildren from 586 family lineages and 2,832 white grandchildren from 899 family lineages. Missing data that arise from control variables, such as occupational status, home ownership, and family income in grandparent and parent generations, are replaced based on multiple imputation methods.1

Measures

The observed outcome variable is the education of individual i, a grandchild in generation 3, measured by years of schooling. Let denote the exposure variable, that is, individual ’s family history of education, which is measured by the highest years of schooling among grandparents in generation 1 and the higher years of schooling between parents in generation 2, respectively2. For example, if a family has two grandparents whose information is available, then refers to the education of the grandparent with the higher level of education. If information for some grandparents or parents is missing, the years of schooling are measured among those whose information is available.

The history of childhood family structure is treated as a generation-varying mediator. If parents were married throughout a child’s entire childhood at age 0 to 18, then family structure is coded as a two-parent family; otherwise, it would be a single-parent family. The single-parent family group consists of four subgroups: parents were unmarried throughout a child’s entire childhood, parents were unmarried at birth but were married at a later point and thereafter during a child’s childhood, parents were unmarried at a child’s birth but were married and later divorced or separated, and parents were married at birth but subsequently divorced or separated. The analysis combines the first three subgroups of single-parent families, thus yielding three categories of family structure: one-parent families with unmarried parents, one-parent families with divorced parents, and two-parent intact families. If either the father or the mother were raised in a single-parent household before he or she reached age 18, is treated as a single-parent family in generation 1.

I categorize other covariates into three mutually exclusive groups. First, the baseline or time-invariant covariates V denote covariates that occur before the first exposure or that are transmitted across generations without any mobility, but possibly influence all subsequent exposures, mediators, and covariates. This study treats race as such a family-fixed variable, given the relatively few cases of interracial marriages (64 cases) in the analytical sample. Second, generation-varying covariates L denote variables that are affected by exposures or by both exposures and mediators and, in turn, confound the mediator-outcome or exposure-mediator relationship. Covariates L include grandparents’ and parents’ family income, disability status, home ownership, and occupational status. Family income measures average annual total income from all family members over a child’s ages 0 to 18. All income measures are adjusted to 2013 dollars using the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The dichotomous measure of disability status indicates the presence of physical disability or nervous disorders reported by the household head in the family. Home ownership is also a dichotomous measure indicating whether the family ever owned their home during an individual’s childhood. Occupational status is the average socioeconomic index (SEI) scores of household heads and wives (Frederick 2010). The third category of covariates is covariates C, which only influence the outcome variable Y but do not affect nor are affected by exposures and mediators. These variables include gender, age group in 2013, religion, and current residential region of grandchildren. The inclusion of these variables does not affect the unbiasedness of the grandparent effect but can improve the efficiency of the estimation.

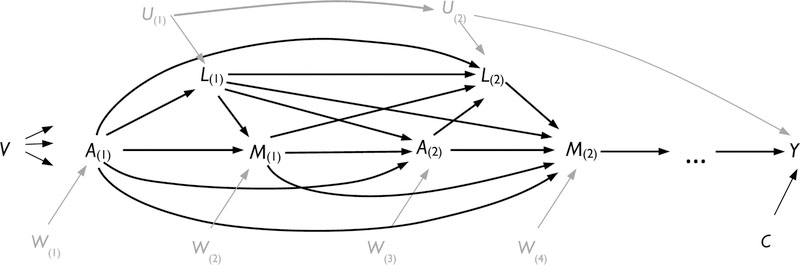

Some other covariates are omitted from the analysis because measures of these variables are not available in the PSID data or are available only for certain waves. These variables may include genetic traits, mental illness, social skills, drinking and drug use behaviors, domestic violence, and incarceration in each generation (Sandefur and Wells 1999). These variables are categorized into unobserved confounders U or W. The relationships among all variables aforementioned are shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

A Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) of Multigenerational Social Mobility

Notes: A(1) = G1’s educational attainment, M(1) = family structure in G1 during G2’ childhood, L(1) = socioeconomic characteristics, such as family income, occupational status, home ownership, and disability status in G1 during G2’ childhood, A(2) = G2’ education, M(2) = family structure in G2 during G3’s childhood, U, W = unmeasured variables, Y = G3’s educational attainment. C = exogenous variables that influence Y, such as gender and age group. V = family invariant variables, such as race. The order of these variable measurements in the timeline indicates the direction of causal effect. For the sake of simplicity, the graph omits all the arrows pointing from A(t), L(t), M(t) to Y. While not explicitly shown in DAGs, the strength of grandparent’s direct effect, i.e., the arrow pointing from A(1) to Y, may vary by the values of M(1) and M(2) according to the research hypothesis of this study.

Methods

Assumptions

The causal direct effect of grandparents is identified under two assumptions (Pearl 2001; VanderWeele 2009). First, all confounders of the association between the exposure and the outcome are included in the model. That is, When this assumption is violated, our estimates of are biased because of potential selection biases caused by unobserved variables that are correlated with both the exposure and the outcome.

Second, all confounders of the association between the mediators and the outcome are included in the model. That is, When this assumption is violated, our estimates are subject to a collider bias because controlling for the mediators would lead to a spurious correlation between the exposure and the outcome due to unobserved variables that are correlated with both the mediator and the outcome (but potentially not with the exposure) (Elwert and Winship 2014).

Models

The analysis relies on the hierachical linear model, also known as mixed effect models with random intercepts (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002), which accounts for the clustering of respondents in generation 3 from the same family lineage. Let be the ith respondent in generation 3 who is from family lineage j. The interactive model can be written as below:

Individual level:

| (1) |

| (2) |

The variable represents a family trajectory of (the same notation rule also applies to and ). Each of the coefficients represents a set of regression coefficients for the corresponding variable. The errors are assumed to be independent and homoscedastic.

Lineage level:

| (3) |

To account for heterogeneity in educational attainment associated with families, I assume that each family lineage is independently and normally distributed with educational mean and (between-family) variance

Based on the interactive model specification in equation (1) and assumptions discussed in the last section, we define the (conditional) direct effect of grandparents as

If the direct effect of grandparents varies across types of family structure, we would observe significant interactions between grandparent education and family structures, namely To estimate the average direct effect of grandparents, I rely on an additive model without the exposure-mediator interactions between and in the Level 1 equation. For practical reasons, the model omits all interactions between covariates and exposures and between covariates and mediators, because they are insignificant in the model specification test and are not the focus of this study. In particular, a test of interactions between and the covariate age group shows little evidence of variations in multigenerational effects by cohort.

Inverse Probability Treatment Weighting Estimation

The grandparent effect estimated from the aforementioned regression approach, however, does not necessarily provide a causal interpretation. Even if the two assumptions discussed in the prior section are satisfied, standard regression models may not provide unbiased estimates of grandparent effects in a longitudinal setting with complex time-varying confounding. For example, to estimate the effect of A(1) on Y, we have to control for L(1); otherwise, the unobserved variable U(1) would be associated with both M(1) and Y, and assumption (2) is violated. But controlling for L(1) causes another problem: a spurious association between A(1) and U(1) emerges because L(1) is a collider in the paths A(1) L(1) U(1), and therefore assumption (1) is violated due to this “collider-bias” (Elwert and Winship 2014).

A weighting technique provides an alternative approach to estimate controlled direct effects in longitudinal settings (VanderWeele 2015: 153–168). Instead of regression adjustment, time-varying covariates are controlled for by inverse probability treatment weighting in the final regression model. The overall weight for the grandchild i is

where the exposure weight at time t, and the mediator weight at time t, In particular, These probabilities are estimated by multinomial logistic models for the exposures and mediators. This weighting scheme requires that we include the baseline variable V and covariates C of generation 3 (but not the generation-varying covariates ) into the final model as specified in equations (1) to (3). The final model is also known as a marginal structural model (MSM) because after the weighting, conditional distributions of the exposures and mediators no longer depend on the time-varying covariates (Robins and Hernán 2009; VanderWeele 2009, 2015).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 2 provides a detailed description of distributions of family structure in the analytical sample. The descriptive statistics suggest that most African Americans and whites in the parent generation grew up in traditional two-parent families. However, single-parent families, especially those with unmarried parents have become the prevailing family structure in the grandchild generation for African Americans, but not for whites. Table 3 summarizes the full sample characteristics by generation and race for all variables used in the analysis. On average, African American families are disadvantaged in their educational attainments and other socioeconomic indicators compared to those of whites in each generation. While the educational gap between African American and white families from the parent to the grandchild generation indicates a converging trend, their family structures have diverged. The proportion of single-parent families has increased faster for African American families, from around 31 percent of parents growing up in single-parent families to 66 percent in the grandchild generation, compared to an increase from 17 percent to 35 percent for whites.

Table 2.

Definitions of Family Structures by Parents’ Marital Status (Unmarried, Married, Divorced/Separated/Widowed) Throughout Offspring’s Childhood at Ages 0–18

| Types of family structure |

Parents’ marital status when a child is at |

Percent in G2 | Percent in G3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth | Age 1–18 | All | African Americans |

Whites | All | African Americans |

Whites | ||

| (1a) | One-parent, unmarried | Unmarried | Unmarried | 2.7 | 5.4 | 0.4 | 11.7 | 22.9 | 1.7 |

| (1b) | One-parent, unmarried | Unmarried | Married | 1.2 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 5.5 | 8.9 | 2.5 |

| (1c) | One-parent, unmarried | Unmarried | Divorced/separated/widowed/remarried | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 6.8 | 11.4 | 2.7 |

| (2) | One-parent, divorced | Married | Divorced/separated/widowed/remarried | 18.8 | 22.7 | 15.4 | 25.4 | 22.7 | 27.8 |

| (3) | Two-parent, intact | Married | Married | 76.1 | 68.8 | 82.6 | 50.6 | 34.1 | 65.4 |

| Total (Observations) | 100 (5,357) | 100 (2,525) | 100 (2,832) | 100 (5,357) | 100 (2,525) | 100 (2,832) | |||

Data sources: Multigenerational linked data from Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), 1968–2013.

Notes: G2 and G3 refers to parents in generation 2 and grandchildren in generation 3 in the multigenerational sample, respectively. The sample is restricted to grandchildren in G3 who are aged between 25 and 65. As the subsample of other racial and ethnic groups, such as Native Americans and Asians, are underrepresented in the PSID data (< 3 percent), they are combined with whites into a single group.

Table 3.

Sample Characteristics by Generation and Race

| Variables | Mean (S.D) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| All | African Americans |

Whites | |

| Grandparents, generation 1 | |||

| Grandparents’ highest years of schooling | 10.8 (3.3) | 9.7 (3.0) | 11.7 (3.2) |

| Family structure during G2’s childhood | |||

| % One-parent families, unmarried parents | 5.1 | 8.6 | 2.1 |

| % One-parent families, divorced parents | 18.8 | 22.7 | 15.4 |

| % Two-parent families | 76.1 | 68.8 | 82.6 |

| Disability | 31.4 | 39.0 | 24.7 |

| Occupational status (socioeconomic index) | 28.7 (20.6) | 18.4 (11.7) | 37.8 (22.4) |

| Own home | 69.3 | 54.1 | 82.8 |

| Average family income during G2’s childhood | 56,314 (38,983) | 36,780 (20,418) | 73,730 (43,122) |

| Parents, generation 2 | |||

| Parents’ highest years of schooling | 13.2 (2.3) | 12.6 (2.1) | 13.7 (2.3) |

| Family structure during G3’s childhood | |||

| % One-parent families, unmarried parents | 24.0 | 43.2 | 6.8 |

| % One-parent families, divorced parents | 25.4 | 22.7 | 27.8 |

| % Two-parent families | 50.6 | 34.1 | 65.4 |

| Disability | 47.2 | 53.3 | 41.8 |

| Occupational status (socioeconomic index) | 34.7 (19.2) | 27.3 (14.7) | 41.3 (20.3) |

| Own home | 81.8 | 70.6 | 91.8 |

| Average family income during G3’s childhood | 65,002 (144,710) | 41,702 (26,464) | 85,775 (195,137) |

| Grandchild, generation 3 | |||

| Years of schooling | 13.1 (2.2) | 12.6 (2.1) | 13.6 (2.3) |

| % Male | 50.8 | 51.6 | 50.0 |

| Age in 2013 | |||

| % 25–34 | 49.1 | 44.8 | 52.8 |

| % 35–44 | 39.8 | 39.6 | 40.0 |

| % 45–54 | 8.2 | 11.3 | 5.4 |

| % 55–65 | 2.9 | 4.2 | 1.8 |

| Region | |||

| % Northeast | 13.0 | 5.6 | 19.6 |

| % North central | 23.9 | 16.6 | 30.3 |

| % South | 49.9 | 71.4 | 30.8 |

| % West | 13.2 | 6.4 | 19.3 |

| Religion | |||

| % Catholic | 17.6 | 6.2 | 27.9 |

| % Jewish | 1.5 | 0.3 | 2.6 |

| % Protestant | 74.9 | 89.0 | 62.3 |

| % Others | 6.0 | 4.6 | 7.3 |

| Number of family lineages | 1,485 | 586 | 899 |

| Number of observations | 5,357 | 2,525 | 2,832 |

Data sources: Multigenerational linked data from Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), 1968–2013.

Notes: Figures in parentheses are standard deviations for continuous variables.

Table 4 displays the link between grandchildren’s average years of schooling and types of family structure. The results suggest several distinct disparities. First, years of schooling are the highest among grandchildren who are raised in two-parent families, followed by those from divorced families, and the lowest among those from nonmarital birth. Second, family structure cannot explain away all racial disparities in education presented in Table 3, in that the educational advantages of whites still prevail, even within the same type of family structure. Third, intact family structures in two consecutive generations engender cumulative advantages to grandchildren’s educational attainment, as compared to families that maintain only one generation of family intactness. If both grandchildren and their parents grow up in two-parent families, the grandchildren receive, on average, 14.0 years of schooling for whites and 13.2 years for African Americans, the levels of education that are the highest among all types of families.

Table 4.

Educational Attainment of Grandchildren by Multigenerational Types of Family Structure

| Grandchildren’s Years of Schooling: Mean (S.D) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family structure in G1 |

Family structure in G2 |

Family structure in both G1 and G2 |

|||||||

| Unmarried | Divorced | 2-parent | Unmarried | Divorced | 2-parent | Unmarried | Divorced | 2-parent | |

| Full Sample | 12.7 (2.1) | 12.7 (2.1) | 13.2 (2.3) | 12.2 (2.0) | 12.8 (2.2) | 13.7 (2.2) | 12.6 (1.9) | 12.6 (2.0) | 13.8 (2.2) |

| N | 275 | 1,007 | 4,075 | 1,284 | 1,360 | 2,713 | 140 | 243 | 2,163 |

| Percent, % | 5.1 | 18.8 | 76.1 | 24.0 | 25.4 | 50.6 | 2.6 | 4.5 | 40.4 |

| African Americans | 12.7 (2.1) | 12.5 (2.1) | 12.6 (2.1) | 12.2 (1.9) | 12.4 (2.1) | 13.2 (2.2) | 12.6 (1.9) | 12.3 (1.9) | 13.2 (2.2) |

| N | 217 | 572 | 1,736 | 1,091 | 574 | 860 | 124 | 112 | 600 |

| Percent, % | 8.6 | 22.7 | 68.8 | 43.2 | 22.7 | 34.1 | 4.9 | 4.4 | 23.8 |

| Whites | 13.1 (2.0) | 13.0 (2.2) | 13.7 (2.3) | 12.2 (2.1) | 13.0 (2.2) | 13.9 (2.2) | 12.9 (1.9) | 12.8 (2.1) | 14.0 (2.2) |

| N | 58 | 435 | 2,339 | 193 | 786 | 1,853 | 16 | 131 | 1,563 |

| Percent, % | 2.0 | 15.4 | 82.6 | 6.8 | 27.8 | 65.4 | 0.6 | 4.6 | 55.2 |

Data sources: Multigenerational linked data from Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), 1968–2013.

Notes: For the sake of simplicity, the figures are calculated based on data from the first imputed dataset. The statistics are similar for the other 19 imputed samples. When presenting the joint distribution of family structure in both G1 and G2, the table omits all categories except for those that have the same structure in G1 and G2, namely both unmarried, divorced, and two-parent.

Average Direct Effect of Grandparents

Table 5 presents model estimates for the direct effect of grandparents on grandchildren, based on both conventional hierarchical linear models and marginal structural models using inverse probability treatment weights. The additive models test the Markovian assumption about the grandparent effect, that is, whether grandparents’ education has a direct effect on grandchildren’s education. Overall, the regular and the weighted estimates suggest that both parents and grandparents can transmit appreciable educational advantages to their grandchildren among both African Americans and whites. The average parent effect is significantly greater for white families than for African American families ( = 0.361 versus 0.239). This result aligns with findings from previous studies on racial patterns in two-generation mobility, which suggests that African Americans are less likely to transmit their socioeconomic statuses across generations (Duncan 1968; Featherman and Hauser 1978; Hout 1984; Hauser et al. 2000).

Table 5.

Additive Model Estimates for Direct Effects of Grandparents’ Education on Grandchildren’s Education based on Mixed-Effects Models with Random Intercepts (Regular) and Marginal Structural Models (MSM)

| Full Sample |

African Americans |

Whites |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular | MSM | Regular | MSM | Regular | MSM | |

| Grandparents, generation 1 | ||||||

| Years of schooling | 0.015 (0.013) |

0.056*** (0.012) |

0.020 (0.018) |

0.039* (0.018) |

0.008 (0.019) |

0.055*** (0.017) |

| Family structure (reference: two-parent) | ||||||

| One-parent, divorced | −0.210** (0.081) |

−0.337*** (0.090) |

−0.007 (0.109) |

−0.090 (0.123) |

−0.408** (0.118) |

−0.574*** (0.124) |

| One-parent, unmarried | 0.239† (0.140) |

0.077 (0.154) |

0.291† (0.162) |

0.186 (0.177) |

0.268 (0.276) |

0.022 (0.287) |

| Parents, generation 2 | ||||||

| Years of schooling | 0.256*** (0.017) |

0.304*** (0.018) |

0.198*** (0.025) |

0.239*** (0.027) |

0.296*** (0.024) |

0.361*** (0.024) |

| Family structure (reference: two-parent) | ||||||

| One-parent, divorced | −0.477*** (0.068) |

−0.501*** (0.074) |

−0.517*** (0.114) |

−0.657*** (0.111) |

−0.334*** (0.087) |

−0.344*** (0.100) |

| One-parent, unmarried | −0.498*** (0.079) |

−0.547*** (0.087) |

−0.450*** (0.103) |

−0.614*** (0.105) |

−0.500*** (0.155) |

−0.591*** (0.165) |

| Number of family lineages | 1,485 | 1,485 | 586 | 586 | 899 | 899 |

| Number of observations | 5,357 | 5,357 | 2,525 | 2,525 | 2,832 | 2,832 |

Data sources: Multigenerational linked data from Panel Study of Income Dynamics, 1968–2013.

Notes: Figures in parentheses are robust standard errors from 20 imputed samples.

p < .1,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001 (two-tailed tests).

Coefficients of control variables including grandparents’ and parents’ disability status, occupational status, family income, and homeownership as well as grandchildren’s age groups, sex, region, and religion are not presented in the table. Full model results are presented in the Online Appendix Table A1.

Compared to the effect of parents’ education, the direct effect of grandparents’ education is weaker. The amount of the grandparent effect is only approximately one-sixth that of the parent effect. The estimates reveal that each one-year difference in grandparents’ education translates into only 0.04 year difference in grandchildren’s education for African Americans and 0.06 year difference for whites, everything else being equal. A further test shows that racial differences in grandparent effects are not statistically significant. The results reject a Markovian explanation for the absence of grandparent effects on grandchildren for both races, indicating that the total effect of grandparents are not fully mediated by parents’ education or family structure, though the direct effect of grandparents is very small compared to the direct effect of parents.

The coefficients for childhood family structure experienced by parents and grandchildren ( and ) reflect that family structure may have a bigger impact on white grandchildren than on African American grandchildren. African American grandchildren’s years of education are associated with only their own childhood family structures, but not those of their parents, whereas for whites, family structure experienced by parents during their childhood has a legacy effect on children’s educational attainment. For example, everything else being equal, white grandchildren who themselves and whose parents grew up with divorced parents receive roughly 0.9 (0.574+0.344) years less education than their two-parent counterparts. The same estimate is 0.7 (0.657+0.090) years for African American grandchildren. As discussed earlier, the coefficients of parents’ and grandparents’ education and family structure have causal interpretations only when the model assumptions about the independence of unobserved variables U remain valid.

Moderation Effects of Family Structure on Grandparent Effects

The interactive models in Table 6 show variations in grandparent effects by childhood family structure experienced by grandchildren and their parents, that is, the moderation effect of family structure on the direct effects of grandparents. The results suggest that the seemingly stronger grandparent effects among whites than among African Americans shown in Table 5 have obscured substantial heterogeneity associated with family structure. Specifically, grandparents play a much more influential role in grandchildren’s education in two-parent families than in families with divorced parents, and especially families with unmarried parents, as suggested by the interaction coefficients between grandparents’ education and grandchildren’s family structure. The results hold for both racial groups but are especially striking for African Americans.

Table 6.

Interactive Model Estimates for Direct Effects of Grandparents’ Education on Grandchildren’s Education by Family Structures across Generations based on Mixed-Effects Models with Random Intercepts (Regular) and Marginal Structural Models (MSM)

| Full Sample |

African Americans |

Whites |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular | MSM | Regular | MSM | Regular | MSM | |

| Grandparents, generation 1 | ||||||

| Years of schooling | 0.049** (0.018) |

0.089*** (0.019) |

0.095*** (0.030) |

0.121*** (0.033) |

0.028 (0.024) |

0.075** (0.024) |

| Family structure in G1 (reference: two-parent) | ||||||

| One-parent, divorced |

−0.031 (0.028) |

−0.050† (0.030) |

−0.034 (0.036) |

−0.058 (0.042) |

−0.021 (0.043) |

−0.026 (0.047) |

| One-parent, unmarried |

0.033 (0.042) |

0.021 (0.047) |

0.023 (0.053) |

0.016 (0.061) |

0.020 (0.068) |

0.010 (0.073) |

| Family structure in G2 (reference: two-parent) | ||||||

| One-parent, divorced |

−0.027 (0.022) |

−0.026 (0.024) |

−0.085* (0.036) |

−0.082* (0.042) |

−0.020 (0.029) |

−0.023 (0.035) |

| One-parent, unmarried |

−0.088*** (0.024) |

−0.096*** (0.028) |

−0.109*** (0.033) |

−0.115*** (0.036) |

−0.124** (0.048) |

−0.131* (0.057) |

| Number of family lineages | 1,485 | 1,485 | 586 | 586 | 899 | 899 |

| Number of observations | 5,357 | 5,357 | 2,525 | 2,525 | 2,832 | 2,832 |

Data sources: Multigenerational linked data from Panel Study of Income Dynamics, 1968–2013.

Notes: Figures in parentheses are robust standard errors.

p < .1,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001 (two-tailed tests).

Coefficients of main effects of parents’ family structure and education as well as interactions between parents’ education and family structure in G1 and G2 are omitted from the table. Coefficients of control variables including grandparents’ and parents’ disability status, occupational status, family income, and homeownership as well as grandchildren’s age groups, sex, region, and religion are not presented in the table. Full model results are presented in the Online Appendix Table A2.

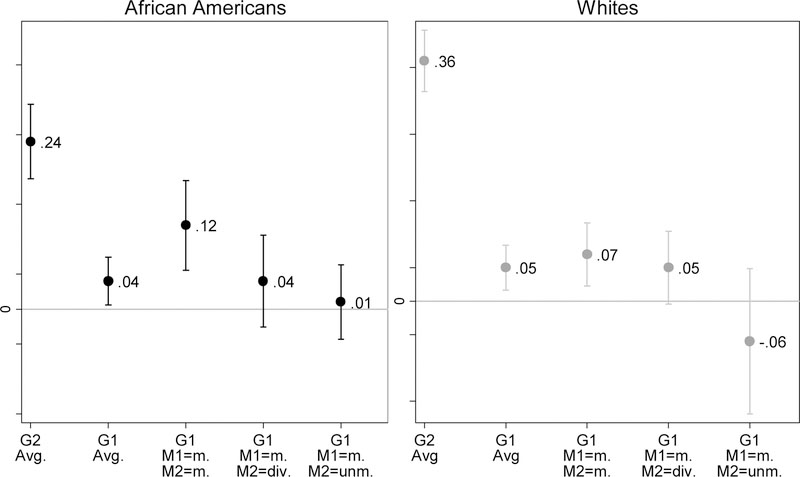

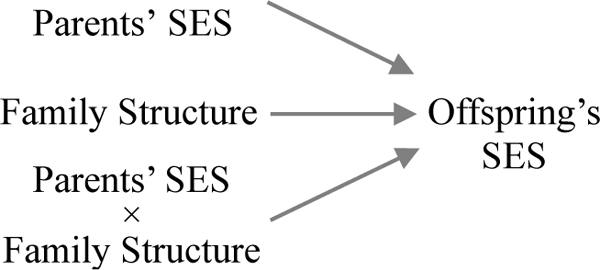

Figure 2 shows a diversity of grandparent effects by the types of family structure and racial group, based on estimates from Table 6. Given the small number of single-parent families in the grandparent generation and the insignificant effect of interactions between grandparents’ family structure and education, the figure presents grandparent effects by varying only parents’ family structure. The graph reveals several sets of findings that are not evident from coefficients in Table 6. First, three-generation mobility is non-Markovian among two-parent families but Markovian among families with children born to unmarried parents for both racial groups. The estimated grandparent effect in families with divorced parents is close to that of families with unmarried parents for African Americans, but close to that of two-parent families for whites.

Fig. 2.

Heterogeneous Direct Effects of Grandparents’ Education on Grandchildren’s Education by Family Structure and Race

Data sources: Panel Study of Income Dynamics, 1968–2013.

Notes: The first two points in each subgraph refer to estimates of average parent and grandparent effects from the additive models in Table 5. The other points refer to estimates of grandparent effects in each family form from the interactive models in Table 6. Capped spikes refer to 95 percent confidence intervals of the estimates. Variables M1 and M2 refer to family structure in the grandparent generation and parent generation respectively. All the other variables are fixed at their means. Abbreviations refer to married parents (m.), divorced parents (div.), and unmarried parents (unm.).

Second, while the average parent and grandparent effects are both weaker among African Americans than among whites, the grandparent effect is particularly strong among African American families that have preserved intactness for two generations: The coefficient of the effect, 0.12, is half as large as the parent effect, 0.24. Yet such intact families constitute only 23.8 percent of African American families (see Table 4). For the majority, namely families that experienced divorce or nonmarital birth in the grandchild generation but were intact in the parent generation, the grandparent effect is negligible. Grandparent effects across the types of family structure exhibit a similar, though less pronounced, trend for whites if we only focus on the point estimates. A further statistical test, however, suggests no significant variations by race.

Third, we observe more variation in grandparent effects by family structure among African Americans than among whites. One possible explanation is that two-parent families are a more selective group among African Americans, resulting in a bigger contrast between two-parent and single-parent families among African Americans than whites. However, a further test suggests that differences among these effects by race are statistically insignificant. In the online appendix, I supplement the results with a sensitivity analysis that shows the extent to which the causal argument is still valid when some assumptions are violated. Overall, the sensitivity analysis indicates that the magnitude of the intergenerational transmission of the unobserved variables (i.e., W(t) in Figure 1), if there is any, would have to be very large to alter our inferences about the causal effect of grandparents’ education on grandchildren’s education.

Discussion

Using multigenerational data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, this study tests whether the direct effect of grandparents’ education on grandchildren’s education varies across types of family structures. The findings reveal substantial heterogeneity in the grandparent effect. Specifically, families that have maintained intactness in family structure also maintain a high degree of similarity in education across generations. The disparities of grandparent effects across family forms are especially evident for African Americans. The stronger grandparent effect in two-parent families may be attributed to explanations such as grandparents setting up trust funds for grandchildren’s education (Aldous 1995), providing practical or monetary support that fosters a better learning environment, offering advice and discussing grandchildren’s academic problems (Cherlin and Furstenberg 1986), serving as role models, monitoring grandchildren’s school progress (DeLeire and Kalil 2002), and improving grandchildren’s educational prospects through the college admission legacy system (Karabel 2005). Additionally, grandparents’ roles can be simply symbolic—the importance of grandparents may not lie in their actions but in “their presence and what they mean for a family” (Bengtson 1985). Some of these mechanisms involve intergenerational contact, interactions, and coresidence and thus are contingent on the survival of grandparents; others may operate through social institutions and thus transcend individual lives. However, the focus of this paper is not to delineate and evaluate these mechanisms but to quantify the grandparent effect; therefore, I consider the aforementioned explanations for my results as merely speculative.

The weaker grandparent effects in single-parent families than in two-parent families also suggest that these grandchildren are more likely to achieve an educational level different from that of their parents and grandparents. However, it is unclear this greater educational mobility in single-parent families results from upward or downward mobility. Implications of these two kinds of mobility for social inequality among families are distinct. If weaker grandparent effects indicate more upward mobility, grandchildren in single-parent families indeed benefit from being loosely tied to their disadvantaged family origins. In contrast, if weaker grandparent effects indicate more downward mobility, these grandchildren are further handicapped in their educational attainment processes because their families are less capable of maintaining their multigenerational advantages and of gaining opportunities for achieving higher education. An auxiliary analysis not presented here shows a higher percentage of upward mobility among two-parent households than unmarried and divorced households, especially for African Americans. These results substantiate the second explanation that a weaker grandparent effect in single-parent families means that these families are less likely to preserve their family privilege rather than more likely to escape from their family histories of hardship.

Several limitations of the present study are worth noting. First, the definition of grandparent effects does not take into account many other potential confounding factors, such as grandparents’ ages (Silverstein and Marenco 2001), number of living grandparents, family tradition of grandparent-grandchild relationships (King and Elder 1997), living arrangements (Dunifon and Kowaleski-Jones 2007), rural residence (King and Elder 1995), and geographic proximity of grandparents and grandchildren (Cherlin and Furstenberg 1986), as well as the ages of grandchildren when their parents separated or divorced. Likewise, the estimates of grandparent effects may further depend on our definition of families’ social advantages. For example, the strength and patterns of grandparent effects may vary by dimensions of social status, ranging from “stocks” of social advantages such as businesses, lands, or estates, to “flows” of advantages such as income, education and occupational position (Mare 2011; Pfeffer 2014). Grandparent effects may vary within families as well, in that the cultural norms of family division of labor by gender and the gender-specific mobility opportunities in a society may be conducive to stronger effects of some grandparents relative to others and unequal mobility outcomes for grandsons and granddaughters (Coall and Hertwig 2010; Uhlenberg and Hammill 1998).

Given the relatively small sample size and its related statistical power, this paper cannot investigate temporal trends in grandparent effects. The analysis only provides a snapshot of grandparent effects by pooling all respondents and their parents and grandparents in the PSID. Therefore, strictly speaking, we cannot establish a causal relationship between demographic changes in declining mortality and growing family complexity and the increasing importance of grandparents over time. The substantial heterogeneity in grandparent effects associated with family structure may result from increasing grandparent effects in two-parent families, or from a composition change. Several studies have illustrated the latter point: As the number of single-parent families grows in a population (Bloome 2014; Musick and Mare 2004), the association between grandparent effects and family structure eventually becomes detectable. Future multigenerational data that permit an analysis of the temporal trend in grandparent effects will help adjudicate between these two possible explanations.

Finally, the results may suffer from bias caused by missing data and measurement errors in the independent variables. If all grandparents’ information is missing, it is likely that grandparents were not part of the PSID sample. If some grandparents’ information is missing, under most circumstances we only have information about either their paternal or their maternal grandparents because of the genealogical sampling design of the PSID. In addition, the sample includes fewer available grandparent observations in single-parent than in two-parent families, indicating that the measure of the highest years of schooling among all grandparents may be less accurate for single-parent families. If we rely on the assumption that observations of grandfathers and grandmothers, as well as paternal and maternal grandparents, are completely missing at random, results presented in the appendix Tables A3 and A4 parcel out influences of different sets of grandparents. Overall, we observe some (but not statistically significant) difference between the average effects of paternal and maternal grandparents or between grandfathers and grandmothers. However, variations in the effects across family structures are mostly associated with maternal grandparents and grandmothers, especially among African Americans. This finding indicates that some sets of grandparents may behave differently in one- and two-parent families. In the presence of measurement errors caused by missing data, the estimates may suffer from the so-called attenuation bias, leading the estimates biased toward zero for both single-parent and two-parent groups. Given that we have more complete grandparent information for the two-parent families, the bias may be larger for single-parent than two-parent families. To test the robustness of the results, I control for the number of available grandparents to see if this variable attenuates the moderation effect of family structure on grandparent effects. The results in Table A5 show little difference from those presented in Table 6.

American families are in transition, as are grandparents’ roles in grandchildren’s lives. Results from this study suggest that the formation of single-parent families due to recent trends in divorce, remarriage, and premarital and multipartner fertility has altered socioeconomic similarities between biological grandparents and grandchildren. Yet another parallel trend is the growth in the percentage of grandparents who are step-grandparents (Yahirun and Seltzer 2014). So far, we know little about the roles of step-grandparents—whether they supplement or replace the roles of biological kindred. The collective role of kin networks, rather than parents and grandparents alone, may contribute to persistent inequalities among families across generations.

Conclusion

In a population, major changes in family organization may beget changes in social stratification (Bengtson 2001). For example, changes in the increasing life expectancy of grandparents and the declining prevalence of two-parent families may have far-reaching consequences for how families create, reproduce, and potentially change their social standing over generations. Along with several recent studies (e.g., Chan and Boliver 2013; Hertel and Groh-Samberg 2014; Zeng and Xie 2014), this study shows the importance of grandparents’ roles in grandchildren’s social attainment—an opposing view to the Markovian assumption in social mobility. Nonetheless, this study further points out that the decline in two-parent families also has generated more American children who now live in families where the grandparent effect in the transmission of social status is weak. In short, these two competing demographic forces jointly drive the evolution of multigenerational social mobility patterns.

Within families, generations are connected not only by social status but also by demographic behaviors (Lam 1986; Maralani 2013; Mare 1997; Mare and Maralani 2006; Matras 1961, 1967; Preston 1974; Preston and Campbell 1993). As illustrated in this paper, the formation of family structures mediates the association between the socioeconomic statuses of parents and offspring, serving as a mechanism to reproduce class disparities. But more importantly, family disruption and reconstitution also modify status connections across generations, placing children born into different types of family structures on different mobility trajectories. Clearly, the family structures investigated in the present study represent only one form of parents’ and grandparents’ demographic behaviors; other factors such as living arrangements, assortative mating, family size, longevity, adoption, migration, and the timing of these events may all influence the strength of intergenerational resemblance in social status across multiple generations. Additionally, socioeconomic standing and demographic behaviors of individuals within the same nuclear family as well as within a wider network of kin may be intertwined (Mare 2015), leading to a spillover effect or a social contagion phenomenon that is often treated as a nuisance in traditional studies of social mobility but may pose a threat to our mobility estimates when a causal interpretation is desired (Hong 2015; Manski 2013). All these demographic complications bear implications for the ramification of social mobility trajectories of families and present challenges for future research.

At the individual level, sociologists have long been intrigued by the question of who gets ahead in social mobility (Jencks et al. 1979). As Hout (2015) points out, however, what we should really be concerned about is “how the conditions and circumstances of early life constrain adult success” rather than “who is moving up.” In the face of demographic changes, this appeal requires us to expand the set of factors by which traditional social mobility studies define individuals’ social origins. Family structure and grandparents’ socioeconomic characteristics are two of these factors that have not been included in most social mobility studies because of their marginal significance in the stratification process until recently. Building on these prior studies, this paper takes a further step in showing that the interaction of these two factors also matters. Still, many other factors that were once considered to be making limited or redundant contributions to individuals’ social origins may now independently or interactively determine individuals’ social destinations. Investigating such factors as the roles of nonresident parents, stepparents and grandparents, other biological or nonbiological kin, great-grandparents and beyond, will further reveal how demography restructures social mobility processes.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Cameron Campbell, Dwight Davis, Hao Dong, Benjamin Jarvis, Rahim Kurwa, James Lee, Robert Mare, Arah Onyebuchi, Sung Park, Judea Pearl, Judith Seltzer, John Sullivan, Donald Treiman, Amber Villalobos, Aolin Wang, Yu Xie, and Xiaolu Zang for their valuable suggestions. Any remaining errors are the sole responsibility of the author. This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (SES-1260456). The author also benefited from facilities and resources provided by the California Center for Population Research at UCLA (CCPR), which receives core support (R24-HD041022) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

Appendices

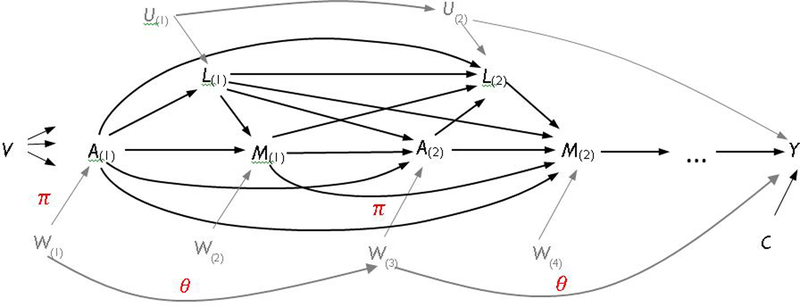

Fig. A1.

A Hypothetical Causal Framework of Multigenerational Social Mobility with Unmeasured Time-Varying Variables

Notes: A(1) = G1’s educational attainment, M(1) = family structure in G1 during G2’ childhood, L(1) = socioeconomic characteristics, such as family income, occupational status, home ownership, and disability status in G1 during G2’ childhood, A(2) = G2’ education, M(2) = family structure in G2 during G3’s childhood, U, W = unmeasured variables, Y = G3’s educational attainment. C = exogenous variables that influence Y, such as gender and age group. V = family invariant variables, such as race. Relationships among variables are encoded in the directed acyclic graph (DAG) above. For the sake of simplicity, the graph omits all the arrows pointing from A(t), L(t), M(t), and W(t) to Y. While not explicitly shown in the graph, the strength of grandparent’s direct effect, i.e., the arrow pointing from A(1) to Y, may vary by the values of M(1) and M(2) according to the research hypothesis of this study. Unlike Figure 1, this graph assumes that the errors of W(t) are correlated with each other as well as with Y. The correlations of these standarized variables are represented by and .

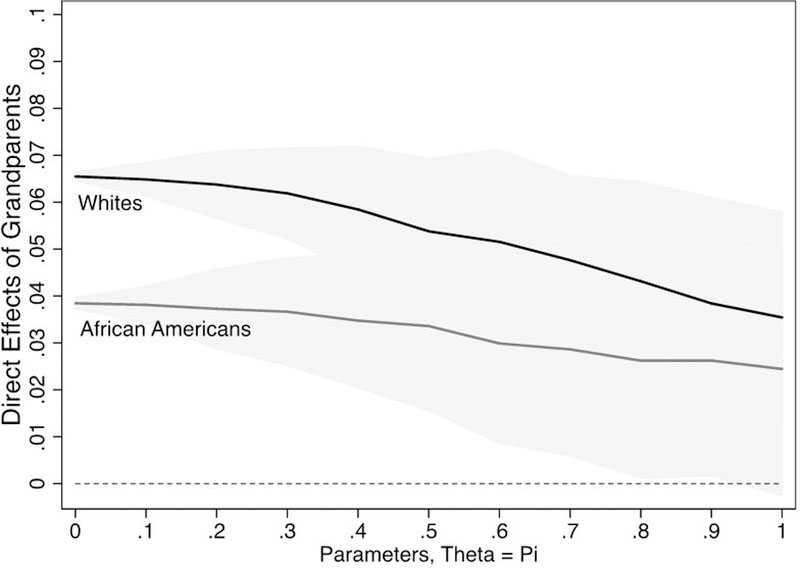

Fig. A2.

Sensitivity Analyses for Effects of Grandparents’ Education on Grandchildren’s Education under Various Assumptions about Strengths of Unobserved Variables W

Notes: The parameter π can be roughly interpreted as the selection bias, or the correlation between W and A. The parameter θ refers to the intergenerational correlation between W(t) and W(t+1). Specifically, I assume that the unobserved variable and , where , and are standardized variables of W, A, and Y. The values of . For the sake of simplicity, this figure shows only results from the sensitivity analysis when θ=π. The bias-corrected estimates for each value of the parameters are based on point estimates from 200 simulated samples. The horizontal line refers to the scenario under which the average grandparent effect is zero. The shaded areas refer to 95% confidence intervals. To speed up the computation, the sensitivity results are based on data with complete cases rather than data with missing-data imputation.

Table A1.

Additive Model Estimates for Direct Effects of Grandparents’ Education on Grandchildren’s Education based on Mixed-Effects Models with Random Intercepts (Regular) and Marginal Structural Models (MSM)

| Full Sample |

African Americans |

Whites |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular | MSM | Regular | MSM | Regular | MSM | |

| Grandparents, generation 1 | ||||||

| Years of schooling | 0.015 (0.013) |

0.056*** (0.012) |

0.020 (0.018) |

0.039* (0.018) |

0.008 (0.019) |

0.055*** (0.017) |

| Family structure (ref: two-parent) |

||||||

| One-parent, divorced | −0.210** (0.081) |

−0.337*** (0.090) |

−0.007 (0.109) |

−0.090 (0.123) |

−0.408** (0.118) |

−0.574*** (0.124) |

| One-parent, unmarried | 0.239† (0.140) |

0.077 (0.154) |

0.291† (0.162) |

0.186 (0.177) |

0.268 (0.276) |

0.022 (0.287) |

| Disability | −0.223** (0.075) |

- | −0.067 (0.099) |

- | −0.347*** (0.107) |

- |

| Occupational status (socioeconomic index) | 0.003 (0.002) |

- | 0.001 (0.005) |

- | 0.002 (0.003) |

- |

| Own home | 0.067 (0.084) |

- | 0.106 (0.106) |

- | 0.039 (0.133) |

- |

| Average family income during G2’s childhood | 4.57*10−6*** (1.27*10−6) |

- | 3.45*10−6 (2.98*10−6) |

- | 3.66*10−6** (1.40*10−6) |

- |

| Parents, generation 2 | ||||||

| Years of schooling | 0.256*** (0.017) |

0.304*** (0.018) |

0.198*** (0.025) |

0.239*** (0.027) |

0.296*** (0.024) |

0.361*** (0.024) |

| Family structure (ref: two-parent) |

||||||

| One-parent, divorced | −0.477*** (0.068) |

−0.501*** (0.074) |

−0.517*** (0.114) |

−0.657*** (0.111) |

−0.334*** (0.087) |

−0.344*** (0.100) |

| One-parent, unmarried | −0.498*** (0.079) |

−0.547*** (0.087) |

−0.450*** (0.103) |

−0.614*** (0.105) |

−0.500*** (0.155) |

−0.591*** (0.165) |

| Disability | −0.171** (0.057) |

- | −0.107 (0.083) |

- | −0.188* (0.080) |

- |

| Occupational status (socioeconomic index) | 0.009*** (0.002) |

- | 0.004 (0.004) |

- | 0.010*** (0.003) |

- |

| Own home | 0.288*** (0.079) |

- | 0.197 (0.100) |

- | 0.282* (0.143) |

- |

| Average family income during G2’s childhood | −3.46*10−7† (1.94*10−7) |

- | 7.05*10−6** (2.11*10−6) |

- | −4.06*10−7* (1.96*10−7) |

- |

| Grandchildren, generation 3 | ||||||

| African Americans | 0.019 (0.086) |

−0.222** (0.084) |

- | - | - | - |

| Female | 0.670*** (0.051) |

0.675*** (0.053) |

0.871*** (0.075) |

0.876*** (0.078) |

0.497*** (0.069) |

0.507*** (0.073) |

| Age group (ref: 25–34) | ||||||

| 35–44 | −0.088* (0.059) |

−0.089 (0.067) |

−0.045 (0.087) |

−0.056 (0.096) |

−0.115 (0.080) |

−0.117 (0.093) |

| 45–54 | 0.002 (0.111) |

0.018 (0.119) |

0.028 (0.143) |

0.004 (0.149) |

−0.051 (0.179) |

0.035* (0.186) |

| 55–65 | 0.442* (0.177) |

0.531** (0.191) |

0.459* (0.222) |

0.497* (0.238) |

0.387 (0.298) |

0.496* (0.248) |

| Religion (ref: Catholic) | ||||||

| Jewish | 0.255 (0.276) |

0.620* (0.291) |

−0.100 (0.848) |

0.136 (0.453) |

0.259 (0.295) |

0.545† (0.311) |

| Protestant | 0.010 (0.095) |

−0.068 (0.100) |

0.251 (0.199) |

0.144 (0.216) |

−0.030 (0.110) |

−0.110 (0.111) |

| Others | −0.116 (0.154) |

−0.228 (0.172) |

0.335 (0.288) |

0.217 (0.311) |

−0.190 (0.183) |

−0.306 (0.199) |

| Region (ref: Northeast) | ||||||

| North central | 0.124 (0.113) |

0.117 (0.125) |

−0.110 (0.221) |

−0.159 (0.254) |

0.228† (0.133) |

0.219 (0.136) |

| South | −0.086 (0.108) |

−0.104 (0.119) |

0.018 (0.200) |

−0.066 (0.225) |

−0.176 (0.131) |

−0.171 (0.140) |

| West | −0.135 (0.126) |

−0.140 (0.135) |

−0.112 (0.260) |

−0.219 (0.270) |

−0.151 (0.144) |

−0.124 (0.151) |

| Intercept | 8.726*** (0.274) |

8.645*** (0.300) |

8.845*** (0.455) |

9.118*** (0.531) |

8.519*** (0.372) |

8.005*** (0.363) |

| Number of family lineages | 1,485 | 1,485 | 586 | 586 | 899 | 899 |

| Number of observations | 5,357 | 5,357 | 2,525 | 2,525 | 2,832 | 2,832 |

Data sources: Multigenerational linked data from Panel Study of Income Dynamics, 1968–2013.

Notes: Figures in parentheses are robust standard errors from 20 imputed samples.

p < .1,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001 (two-tailed tests).

The final marginal structural models do not include the covariates, including grandparents’ and parents’ disability status, occupational status, family income, and homeownership, because they are used to construct the inverse probability weights and do not bias our estimates of exposure variables, namely grandparents’ education, after the weighting.

Table A2.

Interactive Model Estimates for Direct Effects of Grandparents’ Education on Grandchildren’s Education by Family Structures across Generations based on Mixed-Effects Models with Random Intercepts (Regular) and Marginal Structural Models (MSM)

| Full Sample |

African Americans |

Whites |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular | MSM | Regular | MSM | Regular | MSM | |

| Grandparents, generation 1 | ||||||

| Years of schooling | 0.049** (0.018) |

0.089*** (0.019) |

0.095*** (0.030) |

0.121*** (0.033) |

0.028 (0.024) |

0.075** (0.024) |

| Family structure in G1

(ref: two-parent) |

||||||

| One-parent, divorced | 1.190** (0.453) |

1.608** (0.521) |

0.496 (0.637) |

1.161 (0.789) |

1.224† (0.714) |

1.318† (0.770) |

| One-parent, unmarried | 0.205 (0.817) |

0.758 (0.942) |

−0.524 (0.993) |

0.194 (1.178) |

0.520 (1.482) |

0.467 (1.246) |

| Family structure in G1 (ref: two-parent) | ||||||

| One-parent, divorced | −0.031 (0.028) |

−0.050† (0.030) |

−0.034 (0.036) |

−0.058 (0.042) |

−0.021 (0.043) |

−0.026 (0.047) |

| One-parent, unmarried | 0.033 (0.042) |

0.021 (0.047) |

0.023 (0.053) |

0.016 (0.061) |

0.020 (0.068) |

0.010 (0.073) |

| Family structure in G2 (ref: two-parent) | ||||||

| One-parent, divorced | −0.027 (0.022) |

−0.026 (0.024) |

−0.085* (0.036) |

−0.082* (0.042) |

−0.020 (0.029) |

−0.023 (0.035) |

| One-parent, unmarried | −0.088*** (0.024) |

−0.096*** (0.028) |

−0.109*** (0.033) |

−0.115*** (0.036) |