Significance

Modern large-scale data analysis and machine learning applications rely critically on computationally efficient algorithms. There are 2 main classes of algorithms used in this setting—those based on optimization and those based on Monte Carlo sampling. The folk wisdom is that sampling is necessarily slower than optimization and is only warranted in situations where estimates of uncertainty are needed. We show that this folk wisdom is not correct in general—there is a natural class of nonconvex problems for which the computational complexity of sampling algorithms scales linearly with the model dimension while that of optimization algorithms scales exponentially.

Keywords: Langevin Monte Carlo, nonconvex optimization, computational complexity

Abstract

Optimization algorithms and Monte Carlo sampling algorithms have provided the computational foundations for the rapid growth in applications of statistical machine learning in recent years. There is, however, limited theoretical understanding of the relationships between these 2 kinds of methodology, and limited understanding of relative strengths and weaknesses. Moreover, existing results have been obtained primarily in the setting of convex functions (for optimization) and log-concave functions (for sampling). In this setting, where local properties determine global properties, optimization algorithms are unsurprisingly more efficient computationally than sampling algorithms. We instead examine a class of nonconvex objective functions that arise in mixture modeling and multistable systems. In this nonconvex setting, we find that the computational complexity of sampling algorithms scales linearly with the model dimension while that of optimization algorithms scales exponentially.

Machine learning and data science are fields that blend computer science and statistics so as to solve inferential problems whose scale and complexity require modern computational infrastructure. The algorithmic foundations on which these blends have been based rest on 2 general computational strategies, both which have their roots in mathematics—optimization and Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling. Research on these strategies has mostly proceeded separately, with research on optimization focused on estimation and prediction problems and research on sampling focused on tasks that require uncertainty estimates, such as forming credible intervals and conducting hypothesis tests. There is a trend, however, toward the use of common methodological elements within the 2 strands of research (1–12). In particular, both strands have focused on the use of gradients and stochastic gradients—rather than function values or higher-order derivatives—as providing a useful compromise between the computational complexity of individual algorithmic steps and the overall rate of convergence. Empirically, the effectiveness of this compromise is striking. However, the relative paucity of theoretical research linking optimization and sampling has limited the flow of ideas; in particular, the rapid recent advance of theory for optimization (see, e.g., ref. 13) has not yet translated into a similarly rapid advance of the theory for sampling. Accordingly, machine learning has remained limited in its inferential scope, with little concern for estimates of uncertainty.

Theoretical linkages have begun to appear in recent work (see, e.g., refs. 5–12), where tools from optimization theory have been used to establish rates of convergence—notably including nonasymptotic dimension dependence—for MCMC sampling. The overall message from these results is that sampling is slower than optimization—a message which accords with the folk wisdom that sampling approaches are warranted only if there is need for the stronger inferential outputs that they provide. These results are, however, obtained in the setting of convex functions. For convex functions, global properties can be assessed via local information. Not surprisingly, gradient-based optimization is well suited to such a setting.

Our focus is the nonconvex setting. We consider a broad class of problems that are strongly convex outside of a bounded region but nonconvex inside of it. Such problems arise, for example, in Bayesian mixture model problems (14, 15) and in the noisy multistable models that are common in statistical physics (16, 17). We find that when the nonconvex region has a constant and nonzero radius in , the MCMC methods converge to accuracy in or steps, whereas any optimization approach converges in steps. Note, critically, the dimension dependence in these results. We see that, for this class of problems, sampling is more effective than optimization.

We obtain these polynomial convergence results for the MCMC algorithms in the nonconvex setting by working in continuous time and separating the problem into 2 subproblems: Given the target distribution we first exploit the properties of a weighted Sobolev space endowed with that target distribution to obtain convergence rates for the continuous dynamics, and we then discretize and find the appropriate step size to retain those rates for the discretized algorithm. This general framework allows us to strengthen recent results in the MCMC literature (18–21) and examine a broader class of algorithms including the celebrated Metropolis–Hastings method.

Polynomial Convergence of MCMC Algorithms

The Langevin algorithm is a family of gradient-based MCMC sampling algorithms (22–24). We present pseudocode for 2 variants of the algorithm in Algorithm 1, and, by way of comparison, we provide pseudocode for classical gradient descent (GD) in Algorithm 2. The variant of the Langevin algorithm which does not include the “if” statement is referred to as the ULA; as can be seen, it is essentially the same as GD, differing only in its

Algorithm 1:

The (Metropolis-adjusted) Langevin algorithm is a gradient-based MCMC algorithm. In each step, one simulates and , a uniform random variable between 0 and 1. The conditional distribution is the normal distribution centered at and is the target distribution. Without the Metropolis adjustment step, the algorithm is called the unadjusted Langevin algorithm (ULA). Otherwise, it is called the Metropolis-adjusted Langevin algorithm (MALA)

| MALA |

| Input: , stepsizes |

| for do |

| if then |

| Metropolis Adjustment |

| Return |

incorporation of a random term in the update. The variant that includes the “if” statement is referred to as the MALA; it is the standard Metropolis–Hastings algorithm applied to the Langevin setting. It is worth noting that ULA differs from stochastic optimization algorithms in the scaling of the variance of the random term : In stochastic GD, the variance of scales as squared stepsize, .

We consider sampling from a smooth target distribution that is strongly log-concave outside of a region. That is, for , we assume that is -strongly convex outside of a region of radius and is -Lipschitz smooth.* (See SI Appendix, section A for a formal statement of the assumptions.) Let denote the condition number of ; this is a parameter which measures how much deviates from an isotropic quadratic function outside of the region of radius . We prove convergence of the Langevin sampling algorithms for this target, establishing a convergence rate. Given an error tolerance and an initial distribution , define the -mixing time in total variation distance as

Theorem 1. Consider Algorithm 1 with initialization and error tolerance . Then ULA with step size satisfies

| [1] |

For MALA with step size ,

| [2] |

Comparing Eq. 1 with Eq. 2, we see that the Metropolis adjustment improves the mixing time of ULA to a logarithmic dependence in , while sacrificing a factor of dimension . (Note, however, that these are upper bounds, and they depend on our specific setting and our assumptions. It should not be inferred from our results that ULA is generically faster than MALA in terms of dimension dependence.) Comparing Eqs. 1 and 2 with previous results in the literature that provide upper bounds on the mixing time of ULA and MALA for strongly convex potentials (5–12), we find that the local nonconvexity results in an extra factor of . Thus, when the Lipschitz smoothness and radius of the nonconvex region satisfy is , the computational complexity is polynomial in dimension .

Our proof of Theorem 1 involves a 2-step framework that applies more widely than our specific setting. We first use properties of to establish linear convergence of a continuous stochastic process that underlies Algorithm 1. We then discretize, finding an appropriate step size for the algorithm to converge to the desired accuracy. These 2 parts can be tackled independently. In this section, we provide an overview of the first part of the argument in the case of the MALA algorithm. The details, as well as a presentation of the second part of the argument, are provided in SI Appendix, section B.

Letting , assumed finite, a standard limiting process yields the following stochastic differential equation (SDE) as a continuous-time limit of Algorithm 1: , where is a Brownian motion. To assess the rate of convergence of this SDE, we make use of the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence, which upper bounds the total variation distance and allows us to obtain strong convergence guarantees that include dimension dependence. Denoting the probability distribution of as , we obtain (see the derivation in SI Appendix, section B.2) the following time derivative of the divergence of to the target distribution :

| [3] |

The property of that we require to turn this time derivative into a convergence rate is that it satisfies a log-Sobolev inequality. Considering the Sobolev space defined by the weighted norm, , we say that satisfies a log-Sobolev inequality if there exists a constant such that for any smooth function on , satisfying , we have

The largest for which this inequality holds is said to be the log-Sobolev constant for the objective . We denote it as . Taking , we obtain

| [4] |

Note the resemblance of this bound to the Polyak–Łojasiewicz condition (26) used in optimization theory for studying the

Algorithm 2:

GD is a classical gradient-based optimization algorithm which updates along the negative gradient direction

| GD |

| Input: , stepsizes |

| for do |

| Return |

convergence of smooth and strongly convex objective functions—in both cases the difference from the current iterate to the optimum is upper-bounded by the norm of the gradient squared. Combining Eq. 3 with Eq. 4, we derive the promised linear convergence rate for the continuous process:

In SI Appendix, section B.2 we present similar results for the ULA algorithm, again using the KL divergence.

The next step is to bound in terms of the basic smoothness and local nonconvexity assumptions in our problem. We first require an approximation result:

Lemma 1. For -strongly convex outside of a region of radius and -Lipschitz smooth, there exists such that is strongly convex on , and has a Hessian that exists everywhere on . Moreover, we have .

The proof of this lemma is presented in SI Appendix, section B.1. The existence of the smooth approximation established in this lemma can now be used to bound the log-Sobolev constant using standard results.

Proposition 1. For , where is -strongly convex outside of a region of radius and -Lipschitz smooth,

| [5] |

Proof: For -strongly convex whose Hessian exists everywhere on , the distribution satisfies the Bakry–Emery criterion (27) for a strongly log-concave density, which yields

| [6] |

We use the Holley–Stroock theorem (28) to obtain

| [7] |

We see from this proof outline that our approach enables one to adapt existing literature on the convergence of diffusion processes (29–31) to work out suitable log-Sobolev bounds and thereby obtain sharp convergence rates in terms of distance measures such as the KL divergence and total variation. This contributes to the existing literature on convergence of MCMC (32–36) by providing nonasymptotic guarantees on computational complexity. The detailed proof also reveals that the log-Sobolev constant is largely determined by the global qualities of where most of the probability mass is concentrated; local properties of have limited influence on . Since this is a property of the Sobolev space defined by the -weighted norm, the favorable convergence rates of the Langevin algorithms can be expected to generalize to other sampling algorithms (see, e.g., ref. 37).

Exponential Dependence on Dimension for Optimization

It is well known that finding global minima of a general nonconvex optimization problem is NP-hard (38). Here we demonstrate that it is also hard to find an approximation to the optimum of a Lipschitz-smooth, locally nonconvex objective function , for any algorithm in a general class of optimization algorithms.

Specifically, we consider a general iterative algorithm family which, at every step , is allowed to query not only the function value of but also its derivatives up to any fixed order at a chosen point . Thus, the algorithm has access to the vector , for any fixed . Moreover, the algorithm can use the entire query history to determine the next point , and it can do so randomly or deterministically. In the following theorem, we prove that the number of iterations for any algorithm in to approximate the minimum of is necessarily exponential in the dimension .

Theorem 2 (Lower Bound for Optimization). For any , , and , there exists an objective function, , which is -strongly convex outside of a region of radius and -Lipschitz smooth, such that any algorithm in requires at least iterations to guarantee that with constant probability.

We remark that Theorem 2 is an information-theoretic result based on the class of iterative algorithms and the forms of the queries to this class. It is thus an unconditional statement that does not depend on conjectures such as in complexity theory. We also note that if the goal is only to find stationary points instead of the optimum, then the problem becomes easier, requiring only gradient queries to converge (39).

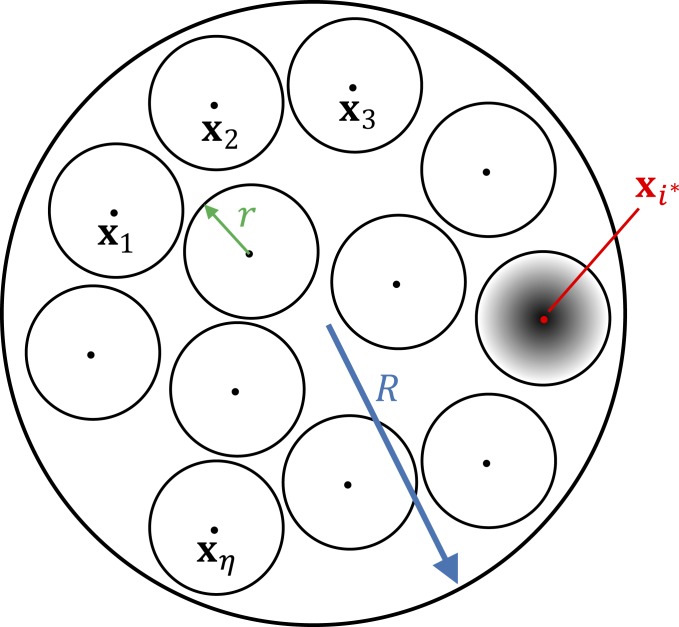

A depiction of an example that achieves this computational lower bound is provided in Fig. 1. The idea is that we can pack exponentially many balls of radius less than inside a region of radius . We can arbitrarily assign the minimum to 1 of the balls, assigning a larger constant value to the other balls. We show that the number of queries needed to find the specific ball containing the minimum is exponential in . Moreover, the difference from to any other point outside of the ball is , which can be significant.

Fig. 1.

Depiction of an instance of , inside the region of radius , that attains the lower bound.

This example suggests that the lower-bound scenario will be realized in cases in which regions of attraction are small around a global minimum and behavior within each region of attraction is relatively autonomous. This phenomenon is not uncommon in multistable physical systems. Indeed, in nonequilibrium statistical physics, there are examples where the global behavior of a system can be treated approximately as a set of local behaviors within stable regimes plus Markov transitions among stable regimes (40). In such cases, when the regions of attraction are small, the computational complexity to find the global minimum can be combinatorial. In section 3, we explicitly demonstrate that this combinatorial complexity holds for a Gaussian mixture model.

Why Can’t One Optimize in Polynomial Time Using the Langevin Algorithm?

Consider the rescaled density function . A line of research beginning with simulated annealing (41) uses a sampling algorithm to sample from , doing so for increasing values of , and uses the resulting samples to approximate . In particular, simply returning 1 of the samples obtained for sufficiently large yields an output that is close to the optimum with high probability. This suggests the following question: Can we use the Langevin algorithm to generate samples from , and thereby obtain an approximation to in a number of steps polynomial in ?

In the following Corollary 1, we demonstrate that this is not possible: We need so that a sample from will satisfy with constant probability. (Here means we have omitted logarithmic factors.) This requires the Lipschitz smoothness of to scale with , which in turn causes the sampling complexity to scale exponentially with , as established in Eqs. 1 and 2.

Corollary 1. There exists an objective function that is -strongly convex outside of a region of radius and -Lipschitz smooth, such that, for , it is necessary that in order to have with constant probability. Moreover, the number of iterations required for the Langevin algorithms to achieve with constant probability is .

It should be noted that this upper bound for the Langevin algorithms agrees with the lower bound for optimization algorithms in Theorem 2 up to a factor of in the exponent. Intuitively this is because in the lower bound for optimization complexity we are considering the most optimistic scenario for optimization algorithms, where a hypothetical algorithm can determine whether one region of radius (as depicted in Fig. 1) contains the global minimum or not with only 1 query (of the function value and -th order derivatives). When using the Langevin algorithms, more steps are required to explore each local region to a constant level of confidence.

Parameter Estimation from Gaussian Mixture Model: Sampling versus Optimization

We have seen that for problems with local nonconvexity the computational complexity for the Langevin algorithm is polynomial in dimension, whereas it is exponential in dimension for optimization algorithms. These are, however, worst-case guarantees. It is important to consider whether they also hold for natural statistical problem classes and for specific optimization algorithms. In this section, we study the Gaussian mixture model, comparing Langevin sampling and the popular expectation-maximization (EM) optimization algorithm.

Consider the problem of inferring the mean parameters of a Gaussian mixture model, , when data points are sampled from that model. Letting denote the data, we have

| [8] |

where are normalization constants and . represents general constraints on the data (e.g., data may be distributed inside a region or may have sub-Gaussian tail behavior). The objective function is given by the log posterior distribution: . Assume data are distributed in a bounded region () and take .

We prove in SI Appendix, section D that for a suitable choice of the prior and weights , the objective function is Lipschitz-smooth and strongly convex for . Therefore, taking , the ULA and MALA algorithms converge to accuracy within and steps, respectively.

The EM algorithm updates the value of in 2 steps. In the expectation (E) step a weight is computed for each data point and each mixture component, using the current parameter value . In the maximization (M) step the value of is updated as a weighted sample mean (see SI Appendix, section D.2 for a more detailed description). It is standard to initialize the EM algorithm by randomly selecting data points (sometimes with small perturbations) to form . We demonstrate in SI Appendix, section D.2 that under the condition that there exists a dataset and covariances , such that the EM algorithm requires more than queries to converge if one initializes the algorithm close to the given data points. That is, for large , the computational complexity of the EM algorithm depends on with arbitrarily high order (depending on ); for small , the computational complexity of the EM algorithm scales exponentially with . The latter case corresponds to our lower bound in Theorem 2 when taking the radius of the convex region of to scale with . Therefore, it is significantly harder for the EM algorithm to converge if we initialize the algorithm close to the given data points. This accords with practical implementations of EM algorithms, where heuristic, problem-dependent methods are often employed during initialization with the aim of decreasing the overall computation burden (42).

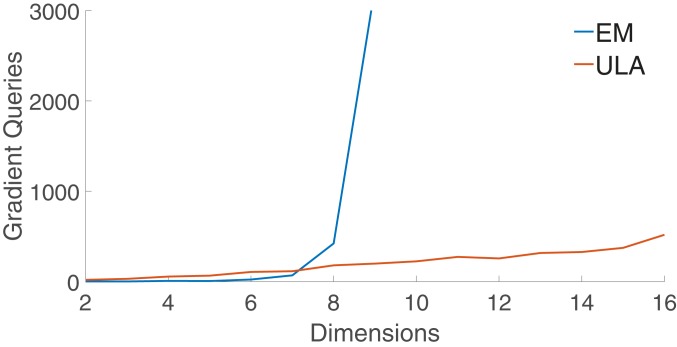

We also investigated this dichotomy experimentally. We generated data with sparse entries, letting the nonzero entries be distributed uniformly on . We inferred the mean parameters with the EM algorithm and ULA algorithm to obtain maximum a posteriori (MAP) and mean estimates, respectively. Accuracy of the MAP estimate was measured in terms of the objective , while that of the mean estimates was measured in terms of both the function value and the expected mean parameters . See SI Appendix, section E for detailed experimental settings. In Fig. 2, we show the scaling of the number of gradient queries required to converge as a function of the dimension . We observe that EM with random initialization from the data requires exponentially many gradient queries to converge, while ULA converges in an approximately linear number of gradient queries, corroborating our theoretical analysis.

Fig. 2.

Experimental results: scaling of number of gradient queries required for EM and ULA algorithms to converge with respect to the dimension . When , too many gradient queries are required for EM to converge, so that an estimate of convergence time is not feasible. When , ULA converges within 1,500 gradient queries (not shown in the figure).

Many mixture models with strongly log-concave priors fall into the assumed class of distributions with local nonconvexity. If data are distributed relatively close to each other, sampling these distributions can often be easier than searching for their global minima. This scenario is also common in the setting of the noisy multistable models arising in statistical physics [e.g., where the negative log likelihood is the potential energy of a classical particle system in an external field (17)] and related fields.

Discussion

We have shown that there is a natural family of nonconvex functions for which sampling algorithms have polynomial complexity in dimension whereas optimization algorithms display exponential complexity. The intuition behind these results is that computational complexity for optimization algorithms depends heavily on the local properties of the objective function . This is consistent with a related phenomenon that has been studied in optimization—local strong convexity near the global optimum can improve the convergence rate of convex optimization (43). On the other hand, sampling complexity depends more heavily on the global properties of . This is also consistent with existing literature; for example, it is known that the dimension dependence of the ULA upper bounds deteriorates when changes from strongly convex to weakly convex. This corresponds to the fact that the sub-Gaussian tails for strongly log-concave distributions are easier to explore than the subexponential tails for log-concave distributions.

A scrutiny of the relative scale between radius of the nonconvex region and the dimension is interesting (for constant Lipschitz smoothness ): When , the problem is reduced to the Lipschitz-smooth and strongly convex case, where GD converges in steps (44) and ULA converges in steps; when , sampling is generally easier than optimization; when , the convergence upper bound for sampling is still slightly smaller than the optimization complexity lower bound; when , the comparison is indeterminate; and the converse is true if .

The relatively rapid advance of the theory of gradient-based optimization has been due in part to the development of lower bounds, of the kind exhibited in our Theorem 2, for broad classes of algorithms. It is of interest to develop such lower bounds for MCMC algorithms, particularly bounds that capture dimension dependence. It is also of interest to develop both lower bounds and upper bounds for other forms of nonconvexity. For example, there has been recent work studying strongly dissipative functions (45). Here the worst-case convergence bounds have exponential dependence on the dimension, but has a sub-Gaussian tail; further exploration of this setting may yield milder conditions on that allow MCMC algorithms to have polynomial convergence rates.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*U being -Lipschitz smooth means that is -Lipschitz continuous. Smoothness is crucial for the convergence of gradient-based methods (25).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1820003116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Amit Y., Grenander U., Comparing sweep strategies for stochastic relaxation. J. Multivar. Anal. 37, 197–222 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amit Y., On rates of convergence of stochastic relaxation for Gaussian and non-Gaussian distributions. J. Multivar. Anal. 38, 82–99 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts G. O., Sahu S. K., Updating schemes, correlation structure, blocking and parameterization for the Gibbs sampler. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. B 59, 291–317 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dempster A., Laird X., Rubin D., Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 39, 1–38 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalalyan A. S., Theoretical guarantees for approximate sampling from smooth and log-concave densities. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. B 79, 651–676 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durmus A., Moulines E., Sampling from strongly log-concave distributions with the unadjusted Langevin algorithm. arXiv:1605.01559 (5 May 2016).

- 7.Dalalyan A. S., Karagulyan A. G., User-friendly guarantees for the Langevin Monte Carlo with inaccurate gradient. arXiv:1710.00095 (29 September 2017).

- 8.Cheng X., Chatterji N. S., Bartlett P. L., Jordan M. I., “Underdamped Langevin MCMC: A non-asymptotic analysis” in Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Learning Theory (COLT) (Association for Computational Learning, 2018), pp. 300–323. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng X., Bartlett P. L., “Convergence of Langevin MCMC in KL-divergence” in Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Algorithmic Learning Theory (ALT) (Association for Computing Machinery, 2018), pp. 186–211. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dwivedi R., Chen Y., Wainwright M. J., Yu B., Log-concave sampling: Metropolis-Hastings algorithms are fast! arXiv:1801.02309 (8 January 2018).

- 11.Mangoubi O., Smith A., Rapid mixing of Hamiltonian Monte Carlo on strongly log-concave distributions. arXiv:1708.07114 (23 August 2017).

- 12.Mangoubi O., Vishnoi N. K., Dimensionally tight running time bounds for second-order Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. arXiv:1802.08898 (24 February 2018).

- 13.Nesterov Y., Introductory Lectures on Convex Optimization: A Basic Course (Kluwer, Boston, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLachlan G. J., Peel D., Finite Mixture Models (Wiley, Chichester, UK, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marin J.-M., Mengersen K., Robert C. P., Bayesian Modelling and Inference on Mixtures of Distributions (Springer-Verlag, New York, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kramers H. A., Brownian motion in a field of force and the diffusion model of chemical reactions. Physica 7, 284–304 (1940). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landau L. D., Lifshitz E. M., Statistical Physics (Pergamon, Oxford, ed. 3, 1980). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eberle A., Guillin A., Zimmer R., Couplings and quantitative contraction rates for Langevin dynamics. arXiv:1703.01617 (5 March 2017).

- 19.Bou-Rabee N., Eberle A., Zimmer R., Coupling and convergence for Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. arXiv:1805.00452 (1 May 2018).

- 20.Cheng X., Chatterji N. S., Abbasi-Yadkori Y., Bartlett P. L., Jordan M. I., Sharp convergence rates for Langevin dynamics in the nonconvex setting. arXiv:1805.01648 (4 May 2018).

- 21.Majka M. B., Mijatović A., Szpruch L., Non-asymptotic bounds for sampling algorithms without log-concavity. arXiv:1808.07105 (21 August 2018).

- 22.Rossky P. J., Doll J. D., Friedman H. L., Brownian dynamics as smart Monte Carlo simulation. J. Chem. Phys. 69, 4628–4633 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberts G. O., Stramer O., Langevin diffusions and Metropolis-Hastings algorithms. Methodol. Comput. Appl. Probab. 4, 337–357 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Durmus A., Moulines E., Nonasymptotic convergence analysis for the unadjusted Langevin algorithm. Ann. Appl. Probab. 27, 1551–1587 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts G. O., Tweedie R. L., Geometric convergence and central limit theorems for multidimensional Hastings and Metropolis algorithms. Biometrika 83, 95–110 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Polyak B. T., Gradient methods for minimizing functionals. Zh Vychisl Mat Mat Fiz 3, 643–653 (1963). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bakry D., Emery M., “Diffusions hypercontractives” in Séminaire de Probabilités XIX 1983/84, J. Azema, M. Yor, Eds. (Springer, 1985), pp. 177–206.

- 28.Holley R., Stroock D., Logarithmic Sobolev inequalities and stochastic ising models. J. Stat. Phys. 46, 1159–1194 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ledoux M., The geometry of Markov diffusion generators. Ann. Fac. Sci. Toulouse Math. 9, 305–366 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Villani C., Optimal Transport: Old and New (Springer, Berlin, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wibisono A., Sampling as optimization in the space of measures: The Langevin dynamics as a composite optimization problem. arXiv:1802.08089 (22 February 2018).

- 32.Frieze A., Kannan R., Polson N., Sampling from log-concave distributions. Ann. Appl. Probab. 4, 812–837 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenthal J. S., Minorization conditions and convergence rates for Markov chain Monte Carlo. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 90, 558–566 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenthal J., Quantitative convergence rates of Markov chains: A simple account. Electron. Commun. Probab. 7, 123–128 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts G. O., Rosenthal J. S., Optimal scaling for various Metropolis-Hastings algorithms. Statist. Sci. 16, 351–367 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts G. O., Rosenthal J. S., Complexity bounds for Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithms via diffusion limits. J. Appl. Probab. 53, 410–420 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma Y.-A., et al. , Is there an analog of Nesterov acceleration for MCMC? arXiv:1902.00996 (4 February 2019).

- 38.Jain P., Kar P., Non-convex optimization for machine learning. Found. Trends Mach. Learn. 10, 142–336 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carmon Y., Duchi J. C., Hinder O., Sidford A., Lower bounds for finding stationary points I. arXiv:1710.11606 (31 October 2017).

- 40.Ge H., Qian H., Landscapes of non-gradient dynamics without detailed balance: Stable limit cycles and multiple attractors. Chaos 22, 023140 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kirkpatrick S., Gelatt C. D., Vecchi M. P., Optimization by simulated annealing. Science 220, 671–680 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vempala S., Wang G., A spectral algorithm for learning mixture models. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 68, 841–860 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bach F., Adaptivity of averaged stochastic gradient descent to local strong convexity for logistic regression. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 15, 595–627 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bubeck S., Convex optimization: Algorithms and complexity. Found. Trends Mach. Learn. 8, 231–357 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raginsky M., Rakhlin A., Telgarsky M., “Non-convex learning via stochastic gradient Langevin dynamics: A nonasymptotic analysis” in Proceedings of the 30th Conference on Learning Theory (COLT) (Association for Computational Learning, 2017), pp. 1674–1703.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.