Abstract

Background:

Despite evidence, frailty is not routinely assessed before cardiac surgery. We compared 5 brief frailty tests for predicting poor outcomes after aortic valve replacement and evaluated a strategy of performing comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) in screen-positive patients.

Design:

Prospective cohort study

Setting:

A single academic center

Participants:

Patients undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) (n=91; mean age, 77.8 years) or transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) (n=137; mean age, 84.5 years) in February 2014-June 2017

Measurements:

Brief frailty tests (Fatigue, Resistance, Ambulation, Illness, and Loss-of-weight scale; Clinical Frailty Scale; grip strength; gait speed; chair rise) and a deficit-accumulation frailty index based on CGA (CGA-FI) were measured at baseline. A composite of death or functional decline and severe symptoms at 6 months was assessed.

Results:

The outcome occurred in 8.8% (n=8) after SAVR and 24.8% (n=34) after TAVR. Chair rise test showed the highest discrimination in SAVR (C-statistic=0.76) and TAVR cohorts (C-statistic=0.63). When chair rise test was chosen as a screening test (≥17 seconds for SAVR and ≥23 seconds for TAVR), the incidence of outcome for screen-negative patients, screen-positive patients with CGA-FI≤0.34, and screen-positive patients with CGA-FI>0.34 were 1.9% (n=1/54), 5.3% (n=1/19), and 33.3% (n=6/18) after SAVR, respectively, and 15.0% (n=9/60), 14.3% (n=3/21), and 38.3% (n=22/56) after TAVR, respectively. Compared with routinely performing CGA, targeting CGA to screen-positive patients would result in 54 fewer CGAs, without compromising sensitivity (routine vs targeted: 0.75 vs 0.75; p=1.00) and specificity (0.84 vs 0.86; p=1.00) in SAVR cohort; and 60 fewer CGAs with lower sensitivity (0.82 vs 0.65; p=0.03) and higher specificity (0.50 vs 0.67; p<0.01) in TAVR cohort.

Conclusions:

Chair rise test with targeted CGA may be a practical strategy to identify older patients at high risk for mortality and poor recovery after SAVR and TAVR in whom individualized care management should be considered.

Keywords: preoperative evaluation, frailty, aortic valve replacement, functional status

INTRODUCTION

Despite numerous studies demonstrating the ability of frailty to predict outcomes of cardiac surgical procedures among older adults,1,2 frailty measures have not yet permeated clinical practice. This may be, in part, because it is unclear how to practically incorporate a frailty assessment in busy clinical practice.3 The “eyeball” test is susceptible to subjective interpretation, low reproducibility, and miscommunication.4 Several frailty assessment tools have been developed to objectively identify older adults at high risk for poor outcomes after cardiac surgical procedures, but the amount of time, resources, and training for assessment varies across these tools.1 A simple frailty test (e.g., gait speed) may be useful,5 but the screening test alone without further evaluation and interventions may have a limited role in improving clinical outcomes. By contrast, a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA), which enables risk assessment and generation of individualized care plan,6,7 remains the gold standard in the evaluation and management of frail older adults.8 However, performing a CGA for every patient is neither feasible nor cost-effective. A more practical strategy is to perform a brief frailty screening test (i.e., a test that requires minimal resources, training, and time) followed by CGA for screen-positive patients.9 Yet there is little empirical evidence on the comparative performance of frailty screening tests. Moreover, it is uncertain whether a targeted CGA strategy can achieve similar sensitivity and specificity to routine strategy.

The objective of this study was twofold: 1) compare the performance of 5 validated frailty screening tests; and 2) compare targeted CGA strategy and routine CGA strategy for predicting death or poor recovery after aortic valve replacement. We hypothesized that a targeted CGA strategy would decrease the number of CGAs without compromising the sensitivity and specificity compared with routine CGA strategy.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

We prospectively enrolled 246 patients who underwent surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) or transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) for severe aortic stenosis at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, and measured functional status for 12 months between February 2014 and June 2017.10 Details of study procedures are described elsewhere.2,10 Briefly, patients were eligible if they were ≥70 years old and underwent SAVR or TAVR for severe aortic stenosis. Excluded were patients who (a) had emergent surgery or surgery involving the aorta or another valve; (b) were clinically unstable to participate in the study assessment; (c) had severe neuropsychiatric impairment (e.g., psychosis or Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] score <15 points); or (d) were unable to communicate with the study team in English. Whether a patient was treated with SAVR or TAVR was determined without randomization by the heart team that were unaware of frailty assessments and CGA collected for this study. Due to lack of randomization, our study should be viewed as 2 independent studies of outcomes after SAVR and TAVR.

Of the 246 patients who met the selection criteria, 18 (7.3%) were excluded from this analysis due to missing data on the primary endpoint, as described later (Supplementary Figure S1). All participants provided written informed consent. The Institutional Review Board at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center approved the protocol.

Frailty Screening Tests

At baseline, a trained research nurse or research assistant administered 5 validated brief frailty tests: 1) Fatigue, Resistance, Ambulation, Illness, and Loss of weight (FRAIL) scale (range: 0-5; higher values indicate greater frailty)11: 2) Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) (range: 1-9; higher values indicate greater frailty), which is based on the patient’s disease symptoms, activity level, mobility, and activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) disabilities12; 3) grip strength (kg),13 measured in the dominant hand using a JAMAR hydraulic dynamometer (lower values indicate greater frailty); 4) usual gait speed (meters/second),5 averaged from three 5-meter walk tests (lower values indicate greater frailty); and 5) chair rise (seconds),14,15 measured in time to complete 5 chair rises without use of hands or arms (higher values indicate greater frailty; those unable to complete the task were assigned to 60 seconds).

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment and a Frailty Index Calculation

A trained research nurse or research assistant performed CGA, which included assessments of medical history, polypharmacy, self-reported functional status, cognitive and physical performance, and nutritional status. Its administration took 30-45 minutes. A CGA-based frailty index (CGA-FI) was calculated according to the deficit-accumulation approach (range: 0-1; higher values indicate greater frailty).16 This approach measures the severity of frailty as a proportion of abnormalities present on CGA. An online calculator is available.17 Individuals are classified as non-frail (<0.10), pre-frail (0.10-0.19), mildly frail (0.20-0.29), moderately frail (0.30-0.39), and severely frail (≥0.40).18-20 Because 81% of our study population had a CGA-FI ≥0.20, classifying patients as frail or not is unlikely to be useful for the outcome prediction. Instead, we determined a CGA-FI cut-point of 0.34 that maximized sensitivity and specificity in predicting the primary endpoint (high risk if CGA-FI>0.34). In addition to CGA-FI, we computed the Essential Frailty Toolset (EFT), which predicts the 1-year risk of death and worsening disability based on chair rise test, MMSE score, hemoglobin level, and albumin level.2 Because EFT required laboratory test results and took 10-12 minutes, we did not consider EFT as a brief screening test.

Outcomes

Patients were evaluated via telephone interview or mailed questionnaires at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months postoperatively. A composite functional status score was created to summarize the number of 7 ADLs (feeding, dressing/undressing, grooming, ambulating, getting in and out of bed, toileting, and bathing), 7 IADLs (using telephone, using transportation, shopping, preparing own meals, doing housework, taking own medications, and managing money), and 8 physical tasks (pulling or pushing a large object, stooping/crouching/kneeling, lifting or carrying 4.5 kg, reaching arms above shoulder, writing/handling small objects, walking up and down a flight of stairs, walking half a mile, and doing heavy work around house) that one can perform without another person’s help (range: 0-22; higher values indicate better functional status). The primary endpoint of poor outcome was defined as a composite of 1) death or 2) a decline from baseline in the composite functional status score and New York Heart Association class 3 or 4 at 6 months. As an alternative to the dichotomous primary endpoint, we evaluated the continuous composite functional status score as a secondary endpoint to examine the change in functional status over 12 months.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 14 (StataCorp). A 2-sided p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. We used a multivariable imputation using chained equation21 to impute missing data (gait speed had the largest amount of missing data [n=35]) based on demographic and clinical characteristics, functional status, procedure type, complications, and mortality. The distribution of frailty screening test performance was compared between patients with and without poor outcome using Kruskal-Wallis test.

To identify the best frailty screening test for predicting poor outcome, we examined receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and C-statistics of the 5 brief frailty tests. As reference, we calculated C-statistics of CGA-FI and EFT. We used bootstrap resampling to test the difference in C-statistics among the brief frailty tests (“rocreg” command). Since C-statistics do not provide a clinical interpretation, we compared sensitivity and specificity at specific cut-points under 2 clinical scenarios of frailty screening: 1) identify ≥75% of patients who will have poor outcome (cut-point 1 was set to achieve sensitivity 75%) and 2) ≥75% of patients who will not have poor outcome (cut-point 2 was set to achieve specificity 75%). We calculated the proportion of screen-positive patients and positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) at each cut-point. Bootstrap resampling was used to test differences in the sensitivities and specificities of the frailty screening tests.

Once the best frailty screening test was determined, we compared targeted CGA strategy (to screen-positive patients only) with routine CGA strategy (to all patients). We estimated the number of CGAs to be performed and the number of cases and non-cases misclassified by adopting targeted strategy. The risk of poor outcome was calculated for screen-negative patients, screen-positive patients with CGA-FI≤0.34, and screen-positive patients with CGA-FI>0.34. Using McNemar test, we compared sensitivity and specificity of targeted vs routine strategy.

To evaluate the change in functional status score over 12 months, we used a linear mixed-effects model that estimated the mean composite functional status score for screen-negative patients, screen-positive patients with CGA-FI≤0.34, and screen-positive patients with CGA-FI>0.34 after adjusting for age, sex, and Charlson comorbidity index.22

RESULTS

Patients who underwent SAVR were younger (mean [standard deviation, SD] age, 77.8 [5.3] vs 84.5 [5.8] years) and had a lower proportion of women (40 [44.0%] vs 71 [51.8%]) than TAVR patients (Table 1). Patients with SAVR had lower burden of comorbid conditions and less severe frailty than patients with TAVR, including CGA-FI (0.24 [0.11] vs 0.37 [0.11]). Poor outcome occurred in 8 (8.8%) SAVR patients and 34 (24.8%) TAVR patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Population

| Characteristics | SAVR (N=91) | TAVR (N=137) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 77.8 (5.3) | 84.5 (5.8) |

| Female, n (%) | 40 (44.0) | 71 (51.8) |

| White race, n (%) | 87 (95.6) | 135 (98.5) |

| STS predicted risk of mortality, %, mean (SD) | 2.8 (1.4) | 5.9 (3.0) |

| Charlson comorbidity score, mean (SD) | 2.2 (1.7) | 3.6 (2.3) |

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter, n (%) | 21 (23.1) | 66 (48.2) |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 29 (31.9) | 79 (57.7) |

| Chronic lung disease, n (%) | 22 (24.2) | 47 (34.3) |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 38 (41.8) | 64 (46.7) |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 14 (15.4) | 35 (25.6) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 28.9 (5.0) | 27.0 (6.4) |

| Mini-Mental State Examination, points, mean (SD) | 27.0 (2.5) | 25.0 (3.2) |

| Brief frailty measures | ||

| FRAIL scale, mean (SD) | 1.5 (1.2) | 2.5 (1.2) |

| Clinical Frailty Scale, mean (SD) | 3.7 (1.1) | 4.7 (1.0) |

| Grip strength, kg, mean (SD) | 25.0 (9.7) | 16.8 (7.9) |

| Gait speed, m/sec, mean (SD) | 0.94 (0.35) | 0.57 (0.22) |

| Chair rise, completed, n (%) | 72 (79.1) | 74 (54.0) |

| Chair rise time, sec, mean (SD) | 14.5 (5.9) | 19.0 (8.0) |

| CGA-FI, mean (SD) | 0.24 (0.11) | 0.37 (0.11) |

| Poor outcome at 6 months, n (%) | 8 (8.8) | 34 (24.8) |

| Mortality, n (%) | 3 (3.3) | 19 (13.9) |

| Functional decline with no symptomatic benefit, n (%) | 5 (5.5) | 15 (10.9) |

Abbreviations: CGA-FI, comprehensive geriatric assessment-based frailty index; FRAIL, Fatigue, Resistance, Ambulation, Illness, and Loss of weight; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; SD, standard deviation; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeons; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Comparative Performance of Frailty Screening Tests

Patients who experienced poor outcome had more impairment on frailty tests than those who did not (Supplementary Figure S2), with a few exceptions. In SAVR cohort, there were differences in grip strength (median [interquartile range] for patients with poor outcome vs those without, 18 [16-20] vs 26 [18-34] kg, p=0.04) and chair rise test (28 [18-60] vs 14 [11-23] seconds, p=0.01), with similar trends in FRAIL scale (2 [2-3] vs 1 [0-2], p=0.10), gait speed (0.71 [0.59-0.87] vs 0.93 [0.65-1.15] meters/second, p=0.06), and CFS (4 [3-4] vs 4 [4-4], p=0.21). In TAVR cohort, there were differences in CFS (5 [4-6] vs 5 [4-5], p=0.03) and chair rise test (60 [23-60] vs 25 [16-60] seconds, p=0.02), but little difference in FRAIL scale (2 [2-3] vs 2 [1-3], p=0.52), grip strength (16 [11-20] vs 15 [11-21] seconds, p=0.99), and gait speed (0.54 [0.37-0.62] vs 0.55 [0.36-0.77] meters/second, p=0.45).

The overall discrimination of brief frailty tests, measured by C-statistics (Table 2 and ROC curves in Supplementary Figure S3), ranged from 0.63 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.72) for CFS to 0.76 (95% CI, 0.65-0.87) for chair rise test in SAVR cohort and 0.50 (95% CI, 0.39-0.61) from grip strength to 0.63 (95% CI, 0.54-0.72) for chair rise test in TAVR cohort. As comparison, C-statistics for CGA-FI were 0.81 (95% CI, 0.70-0.93) in SAVR cohort and 0.66 (95% CI, 0.56-0.75) in TAVR cohort, and those of EFT were 0.65 (95% CI, 0.53-0.77) in SAVR cohort and 0.68 (95% CI, 0.57-0.79) in TAVR cohort. Although the overall discrimination of brief frailty tests was not statistically significantly different in SAVR cohort (p=0.22) or TAVR cohort (p=0.11), we found differences in test performance at specific cut-points (Table 2). At the cut-point 1 to achieve 75% sensitivity, 5 frailty tests showed similar specificities of 0.60 for CFS to 0.70 for FRAIL scale in SAVR cohort (p=0.78) and 0.28 for grip strength to 0.49 for chair rise test in TAVR cohort (p=0.30). At the cut-point 2 to achieve 75% specificity, there were statistically significant differences in sensitivities of 0.13 for CFS to 0.63 for chair rise test in SAVR cohort (p=0.04) and 0.18 for gait speed to 0.62 for chair rise test in TAVR cohort (p<0.01). Based on these results, we determined chair rise test as the best frailty screening test in our study population.

Table 2.

Brief Frailty Screening Tests and Risk of Death or Poor Recovery in 6 Months After Transcatheter and Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement

| Screening Test | C Statistic (95% CI) | Screening Cut-Point 1a | Screening Cut-Point 2a | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut-Point | % Test (+) | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Cut-Point | % Test (+) | Sensitivity | PPV | NPV | ||

| SAVR Cohort (total n=91, outcome n=8) | |||||||||||

| FRAIL scale | 0.68 (0.56-0.79) | ≥2 | 40.7 | 0.70 | 0.16 | 0.96 | ≥3 | 23.1 | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.91 |

| Clinical Frailty Scale | 0.63 (0.54-0.72) | ≥4 | 61.5 | 0.60 | 0.14 | 1.00 | ≥5 | 22.0 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.90 |

| Grip strength, kg | 0.72 (0.61-0.83) | ≤20 | 38.5 | 0.67 | 0.17 | 0.96 | ≤17 | 23.1 | 0.38 | 0.14 | 0.93 |

| Gait speed, m/s | 0.70 (0.59-0.82) | ≤0.84 | 45.1 | 0.61 | 0.15 | 0.96 | ≤0.64 | 24.2 | 0.50 | 0.14 | 0.93 |

| Chair rise, s | 0.76 (0.65-0.87) | ≥17 | 40.7 | 0.65 | 0.19 | 0.98 | ≥23 | 27.5 | 0.63 | 0.20 | 0.95 |

| Comparison of C statistics: p=0.22 | Comparison of specificity: p=0.78 | Comparison of sensitivity: p=0.04 | |||||||||

| TAVR Cohort (total n=137, outcome n=34) | |||||||||||

| FRAIL scale | 0.54 (0.43-0.64) | ≥3 | 42.3 | 0.42 | 0.26 | 0.76 | ≥4 | 21.9 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.75 |

| Clinical Frailty Scale | 0.62 (0.52-0.72) | ≥5 | 55.5 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.84 | ≥6 | 21.9 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.78 |

| Grip strength, kg | 0.50 (0.39-0.61) | ≤20 | 74.5 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.77 | ≤11 | 24.8 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.77 |

| Gait speed, m/s | 0.54 (0.44-0.64) | ≤0.61 | 66.4 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.80 | ≤0.37 | 25.6 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.74 |

| Chair rise, s | 0.63 (0.54-0.72) | ≥23 | 56.2 | 0.49 | 0.33 | 0.85 | ≥60 | 46.0 | 0.62 | 0.33 | 0.82 |

| Comparison of C statistics: p=0.11 | Comparison of specificity: p=0.30 | Comparison of sensitivity: p<0.01 | |||||||||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FRAIL, Fatigue, Resistance, Ambulation, Illness, and Loss of weight; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Screening cut-point 1 was chosen to achieve 75% sensitivity of predicting death or poor recovery for each test; screening cut-point 2 was chosen to achieve 75% specificity for each test.

Targeted CGA Strategy vs Routine CGA Strategy

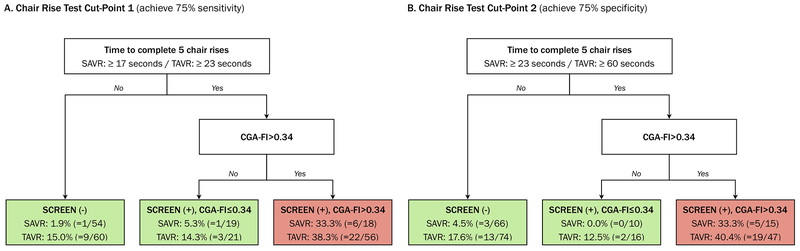

We proposed a practical frailty assessment that consists of chair rise test as a screening test followed by targeted CGA for screen-positive patients (Figure 1). Compared with screen-negative patients, the risk of poor outcome was similar or minimally increased in screen-positive patients with CGA-FI≤0.34 and markedly increased in screen-positive patients with CGA-FI>0.34 in both SAVR and TAVR cohorts. In SAVR cohort, our targeted CGA strategy would reduce the number of CGAs to be performed almost by a third, without compromising the sensitivity and specificity of routine strategy (Table 3). In TAVR cohort, targeted strategy would reduce the number of CGAs to be performed almost by a half, with modest decrease in sensitivity and modest increase in specificity compared with routine strategy. This trade-off in sensitivity and specificity resulted in misclassification of 6-9 patients with poor outcome and correct classification of 18-24 patients without poor outcome in TAVR cohort (Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 1. A Two-Stage Frailty Evaluation and Risk of Death and Poor Recovery at 6 Months After Aortic Valve Replacement.

Abbreviations: CGA, comprehensive geriatric assessment; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Panel A shows a two-stage frailty evaluation using a chair rise test cut-point that achieves 75% sensitivity (≥17 seconds in SAVR cohort and ≥23 seconds in TAVR cohort). CGA is performed in 37 screen-positive patients in SAVR cohort and 77 screen-positive patients in TAVR. Panel B shows a two-stage frailty evaluation using a chair rise test cut-point that achieves 75% specificity (≥23 seconds in SAVR cohort and ≥60 seconds in TAVR cohort). CGA is performed in 25 screen-positive patients in SAVR cohort and 63 screen-positive patients in TAVR cohort.

Table 3.

Routine versus Targeted Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment in Predicting Death or Poor Recovery in 6 Months After Transcatheter and Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement

| Strategyb | Chair Rise Test Cut-Point 1a | Chair Rise Test Cut-Point 2a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut-Point | N of CGA Performed | Sensitivity (95% CI) |

Specificity (95% CI) |

Cut-Point | N of CGA Performed | Sensitivity (95% CI) |

Specificity (95% CI) |

|

| SAVR Cohort (total n=91, outcome n=8) | ||||||||

| Routine CGA | NA | 91 | 0.75 (0.35-0.97) | 0.84 (0.75-0.91) | NA | 91 | 0.75 (0.35-0.97) | 0.84 (0.75-0.91) |

| Targeted CGA | ≥17 s | 37 | 0.75 (0.35-0.97) | 0.86 (0.76-0.92) | ≥23 s | 25 | 0.63 (0.25-0.92) | 0.88 (0.79-0.94) |

| p=1.00 | p=1.00 | p=1.00 | p=0.25 | |||||

| TAVR Cohort (total n=137, outcome n=34) | ||||||||

| Routine CGA | NA | 137 | 0.82 (0.66-0.93) | 0.50 (0.40-0.60) | NA | 137 | 0.82 (0.66-0.93) | 0.50 (0.40-0.60) |

| Targeted CGA | ≥23 s | 77 | 0.65 (0.47-0.80) | 0.67 (0.57-0.76) | ≥60 s | 63 | 0.56 (0.38-0.73) | 0.73 (0.63-0.81) |

| p=0.03 | p<0.01 | p<0.01 | p<0.01 | |||||

Abbreviations: CGA, comprehensive geriatric assessment; CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Chair rise test cut-point 1 was chosen to achieve 75% sensitivity of predicting death or poor recovery; chair rise test cut-point 2 was chosen to achieve 75% specificity.

Routine strategy is to administer comprehensive geriatric assessment in all patients, whereas targeted strategy is to administer comprehensive geriatric assessment for patients who are screen-positive on the chair rise test. The cut-point for comprehensive geriatric assessment-based frailty index to estimate the sensitivity and specificity for predicting death or poor recovery was 0.34.

When long-term functional status change was examined, the screen-positive patients with CGA-FI>0.34 had lower baseline functional status and experienced delayed functional recovery in the year after SAVR and persistent functional impairment in the year after TAVR (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A Two-Stage Frailty Evaluation and Functional Status Change Over 12 Months After Aortic Valve Replacement.

Abbreviations: CGA-FI, comprehensive geriatric assessment-based frailty index; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

A composite functional status score indicates the number of 22 daily activities and physical tasks that one can perform without another person’s help (see the list of 22 activities in the text) (higher values indicate better functional status). The means (nodes) and 95% CIs (vertical bars) of composite functional status score were plotted for chair rise screen-negative patients (<17 seconds in SAVR cohort and <23 seconds in TAVR cohort), screen-positive patients with CGA-FI≤0.34, and screen-positive patients with CGA-FI>0.34.

DISCUSSION

In our study, chair rise test, a measure of lower extremity muscle strength, appears to be better than other frailty screening tests in predicting poor recovery or death after SAVR and TAVR. Although C-statistics, a measure of the overall discriminative ability of a diagnostic or screening test evaluated at all possible cut-points, was not statistically significantly different among the 5 frailty screening tests, chair rise test showed the highest sensitivity at a cut-point that might be useful for clinical decision. In addition, chair rise test has practical advantages over other tests for use in clinical practice, because it is an objective measure that does not require an equipment (e.g., dynamometer) or a large space (e.g., 5-meter space). Patients who are unable to stand up from chair can be assigned to a maximum time (in our study, 60 seconds), which avoids missing data. Moreover, our results suggest that, by targeting CGA to chair rise screen-positive patients, the number of CGAs could be reduced approximately by half or more, without a large compromise in sensitivity and specificity of routine strategy. If our data were applied to a typical TAVR hospital (median annual TAVR volume in the United States: 97 procedures),23 a manageable number of patients (roughly 1 patient/week) would be referred to CGA before TAVR.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services currently mandate participation of patients treated with TAVR in the national Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Therapy registry,24 which collects data on usual gait speed. Despite this requirement, gait speed information is collected in less than 60% of patients in routine TAVR practice; common reasons for missing data were “gait speed not performed” (33%) and “unable to walk” (8%).25 Few prior studies of frailty in cardiac surgical procedures considered the amounts of extra time, training, and resources required for assessment.1 Since frailty assessment tools were optimized to maximize the accuracy in risk prediction by statistical criteria with little consideration of feasibility in routine practice, clinical translation of these research findings has been slow. In our study, the EFT, which was developed to predict mortality and worsening disability in patients undergoing SAVR and TAVR,2 showed lower C-statistic than CGA-FI in SAVR cohort (0.81 vs 0.65) and modestly better C-statistic in TAVR cohort (0.68 vs 0.66). Because administration of EFT took approximately 10-12 minutes in our experience (chair rise test plus 8-10 minutes for MMSE, assuming that hemoglobin and albumin levels are available), we did not consider EFT as a brief frailty test. Beside risk prediction, patients who score high in EFT will need a CGA for development of individualized care plan and interventions. In a recent study,10 CGA-FI was shown to predict clinically distinct functional status trajectories in the year after SAVR and TAVR. While this information may be meaningful to many older patients, CGA requires longer time (30-45 minutes) and additional resources.

The present study provides empirical evidence on the comparative performance of 5 brief frailty tests that can be completed within 3 minutes, and how a frailty screening test can be used to identify patients who may benefit from CGA. We tried to enhance clinical interpretation of the predictive performance by comparing sensitivities of screening tests at a fixed specificity and specificities at a fixed sensitivity (Table 2). Our data suggest that the predictive ability of a test and the cut-points to achieve a desired sensitivity or specificity differ between the SAVR and TAVR patients. Moreover, although chair rise test showed highest C-statistics in both SAVR (C-statistic=0.76) and TAVR cohorts (C-statistic=0.63), grip strength in SAVR cohort (C-statistic=0.72) and CFS in TAVR cohort (C-statistic=0.62) were predictive of poor outcome as well. Other considerations in choosing a frailty screening test include feasibility of administering the test based on patient factors and available resources. Our data can be useful to providers who may prioritize high sensitivity or high specificity.

Our study has a few limitations. First, lack of randomization precludes use of our data for direct comparison of outcomes or decision-making between SAVR and TAVR. Second, patients who had missing data on functional status (n=18) tended to be less frail than those who had available data (mean CGA-FI, 0.28 vs 0.32). As a result, the risk of poor outcome and functional status scores might have been overestimated. Third, because prevalence of frailty and the risk of poor outcome in patients treated at our center may be different from those in other centers, our results on the test performance at selected cut-points may not be generalizable. Choice of best frailty screening tests and optimal cut-points should take clinical context and patient population into consideration. Moreover, more TAVRs are performed in lower-risk patients (as opposed to high-risk patients during out study period), which will lower PPV and increase NPV of the screening tests. Finally, owing to the modest sample size and low incidence of poor outcome in SAVR patients, our estimates of sensitivity and specificity lacked precision. Given these limitations, our results should be interpreted with caution until further replication in an independent population.

Conclusions

Our study supports the time to complete 5 chair rises as a screening test for frailty that is practical in routine clinical practice. It may be an alternative to gait speed measurement that is currently collected in the national registry. Primary care physicians and cardiologists can perform chair rise test in older adults who are contemplating TAVR. Patients who take a longer time or unable to complete the task should be evaluated by a multi-disciplinary team with expertise in cardiology and geriatrics to review their personal goals and develop a perioperative care plan to maximize functional recovery.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure S1. Selection of Study Population

Supplementary Figure S2. Distribution of Frailty Screening Test Performance by Outcome Status After Surgical and Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement

Supplementary Figure S3. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves of Frailty Screening Tests in Predicting Death or Poor Recovery After Surgical and Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement

Supplementary Table S1. Number of Patients Misclassified by Routine versus Targeted Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment Strategy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was conducted with the support of a KL2/Catalyst Medical Research Investigator Training award and an additional support from Harvard Catalyst/The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award KL2 TR001100-01 and UL1 TR001102) and grants (K08AG051187, P30AG031679, and P30AG048785) from the National Institute on Aging to Dr. Kim. Mr. Hosler and Mr. Maltagliati were supported by the Medical Student Training in Aging Research (MSTAR) program, sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (2T35AG038027-06). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers, or the National Institutes of Health.

Sponsor’s Role: The funding sources had no role in the design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Meeting Presentations: An earlier version of this work was presented as a poster at the 2018 American Geriatrics Society annual meeting in Orlando, Florida, on 5/3/2018-5/5/2018. The results presented in this manuscript will be presented as a poster at the 2019 American College of Cardiology Scientific Session in New Orleans, Louisiana, on 3/16/2019-3/18/2019 as well as in the Plenary Session on May 2, 2019 9:30AM-10:15AM (selected as one of the top 3 abstracts) at the 2019 American Geriatrics Society annual meeting in Portland, Oregon.

Conflict of interest:

- Dr. Popma reports grants to his institution from Medtronic and Boston Scientific, consultant fees from Direct Flow, and fees for serving on a medical advisory board from Boston Scientific.

- Ms. Guibone reports consultant fees from Medtronic.

- Other authors declare no disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kim DH, Kim CA, Placide S, Lipsitz LA, Marcantonio ER. Preoperative Frailty Assessment and Outcomes at 6 Months or Later in Older Adults Undergoing Cardiac Surgical Procedures: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(9):650–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afilalo J, Lauck S, Kim DH, et al. Frailty in Older Adults Undergoing Aortic Valve Replacement: The FRAILTY-AVR Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(6):689–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Mieghem NM, Dumonteil N, Chieffo A, et al. Current decision making and short-term outcome in patients with degenerative aortic stenosis: the Pooled-RotterdAm-Milano-Toulouse In Collaboration Aortic Stenosis survey. EuroIntervention. 2016;11(11):e1305–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodés-Cabau J, Mok M. Working Toward a Frailty Index in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2012;5(9):982–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clegg A, Rogers L, Young J. Diagnostic test accuracy of simple instruments for identifying frailty in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2015;44(1):148–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Partridge JS, Harari D, Martin FC, Dhesi JK. The impact of pre-operative comprehensive geriatric assessment on postoperative outcomes in older patients undergoing scheduled surgery: a systematic review. Anaesthesia. 2014;69 Suppl 1:8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beswick AD, Rees K, Dieppe P, et al. Complex interventions to improve physical function and maintain independent living in elderly people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2008;371(9614):725–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellis G, Gardner M, Tsiachristas A, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9:CD006211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lilamand M, Dumonteil N, Nourhashemi F, et al. Gait speed and comprehensive geriatric assessment: two keys to improve the management of older persons with aortic stenosis. Int J Cardiol. 2014;173(3):580–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim DH, Afilalo J, Shi SM, et al. Evaluation of Changes in Functional Status in the Year After Aortic Valve Replacement. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morley JE, Malmstrom TK, Miller DK. A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16(7):601–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173(5):489–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dudzinska-Griszek J, Szuster K, Szewieczek J. Grip strength as a frailty diagnostic component in geriatric inpatients. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:1151–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ensrud KE, Ewing SK, Taylor BC, et al. Comparison of 2 frailty indexes for prediction of falls, disability, fractures, and death in older women. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(4):382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49(2):M85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(7):722–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Senior Health Calculator: For Providers: Online Tool to Calculate Frailty Index (FI). Accessed December 23, 2018 https://www.bidmc.org/research/research-by-department/medicine/gerontology/calculator.

- 18.Clegg A, Bates C, Young J, et al. Development and validation of an electronic frailty index using routine primary care electronic health record data. Age Ageing. 2016;45(3):353–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim DH, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, et al. Validation of a Claims-Based Frailty Index Against Physical Performance and Adverse Health Outcomes in the Health and Retirement Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orkaby AR, Nussbaum L, Ho YL, et al. The Burden of Frailty Among U.S. Veterans and Its Association With Mortality, 2002–2012. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Royston P, White IR. Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE): Implementation in Stata. J Stat Softw. 2011;45(4):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. JChronicDis. 1987;40(5):373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khera S, Kolte D, Gupta T, et al. Association Between Hospital Volume and 30-Day Readmissions Following Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(7):732–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Decision Memo for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR) (CAG-00430N). https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=257. Accessed January 27, 2019.

- 25.Alfredsson J, Stebbins A, Brennan JM, et al. Gait Speed Predicts 30-Day Mortality After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: Results From the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Therapy Registry. Circulation. 2016;133(14):1351–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1. Selection of Study Population

Supplementary Figure S2. Distribution of Frailty Screening Test Performance by Outcome Status After Surgical and Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement

Supplementary Figure S3. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves of Frailty Screening Tests in Predicting Death or Poor Recovery After Surgical and Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement

Supplementary Table S1. Number of Patients Misclassified by Routine versus Targeted Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment Strategy.