Abstract

Background and aims:

Opioid use disorder (OUD) remains a serious public health issue and treating adults with OUD is a major priority in the US. Little is known about trends in the diagnosis of OUD and in buprenorphine prescribing by physicians in office-based medical practices. We sought to characterize OUD diagnoses and buprenorphine prescribing among adults with OUD in the US between 2006 and 2015.

Design and settings:

We used a repeated cross-sectional design, based on data from the 2006-2015 National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys that surveyed nationally representative samples of office-based outpatient physician visits.

Participants:

Adult patients aged 18 or older with a diagnosis of OUD (n=1,034 unweighted) were included.

Measurements:

Buprenorphine prescribing was defined by whether visits involved buprenorphine or buprenorphine-naloxone, or not. We also examined other covariates (e.g., age, gender, race, and psychiatric co-morbidities).

Findings:

We observed an almost tripling of the diagnosis of OUD from 0.14% in 2006-2010 to 0.38% in 2011-2015 in office-based medical practices (p<0.001). Among adults diagnosed with OUD, buprenorphine prescribing increased from 56.1% in 2006-2010 to 73.6% in 2011-2015 (p=0.126) Adults with OUD were less likely to receive buprenorphine prescriptions if they were Hispanic (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=0.26; 95% confidence intervals [CI]=0.11, 0.60), had Medicaid insurance (AOR=0.27; 95% CI=0.10, 0.74), or were diagnosed with other psychiatric disorders (AOR=0.45; 95% CI=0.25, 0.83) or substance use disorders (AOR=0.19; 95% CI=0.09, 0.41).

Conclusions:

In office-based medical practices in the US, diagnoses for opioid use disorder (OUD) and buprenorphine prescriptions for adults with OUD increased from 0.14% and 56.1%, respectively, in 2006-10 to 0.38% and 73.6% in 2011-15.

Keywords: Buprenorphine, opioid use disorder, outpatient care

INTRODUCTION

The opioid crisis is now the most visible and the most serious public health challenge facing the United States.1,2 In 2016, more than 42,000 deaths were attributable to opioid-related overdose, five times more than in 1999, and over 2 million Americans are believed to suffer from opioid use disorder (OUD).3 The Centers for Disease control and Prevention issued guidelines limit the use of prescription opioids for chronic pain,4 and opioid prescriptions have declined by 29% since 2011.5,6 Despite a recent decrease in use of prescription opioids, the number of individuals suffering from OUD has continued to increase due in part to the widespread use of illicit opioids.7 To improve access to care among individuals with OUD, more direct efforts have been initiated to expand access to opioid agonist therapy (e.g., buprenorphine or methadone), the most effective evidence-based pharmacotherapy for OUD.8

Three medications are approved by the Food and Drug Administration in the US to treat OUD: buprenorphine, naltrexone, and methadone. Randomized controlled trials9–11 have clearly demonstrated the clinical benefits of these drugs, and a systematic review of buprenorphine12 concluded that it is effective in managing opioid withdrawal. Buprenorphine is also known for increased adherence to treatment and decreased illicit drug use when used for long-term maintenance.13 A meta-analysis of 19 “real world” observational studies concluded that buprenorphine leads to substantial reductions in the risk of both all-cause and overdose mortality.14

Of the three medications approved for opioid agonist therapy, buprenorphine offers potential widespread use in treating OUD because it has lower potential for misuse, increasing safety in cases of overdose,15 and unlike methadone, can be dispensed in office-based medical practices in the US.16,17 In 2016, the final rule for medication-assisted treatment under the Controlled Substances Act (section 303(g)(2))18 sought to increase access to opioid agonist therapy with both buprenorphine and the combination of buprenorphine-naloxone (hereinafter referred to as buprenorphine) in office settings in the US.18 While expanding access to buprenorphine is, thus, a major public health goal, no study has yet documented provision of buprenorphine within a nationally representative sample for adults with OUD in office-based medical practice settings. Furthermore, after passage of the Drug Addiction Treatment Act (DATA) of 2000, physicians and other healthcare providers have been able to treat OUD with buprenorphine in their offices instead of exclusively in federally regulated program settings.19,20 Thus, it is timely to evaluate buprenorphine prescribing trends among adults with OUD in office-based outpatient care in the US.

The current study seeks to describe, first, trends in the proportion of all visits at which OUD was diagnosed in office-based medical practices from 2006 to 2015, overall and by physician specialty. These years are subdivided into two periods, 2006-2010 and 2011-2015 for comparison purposes, because opioid pain prescriptions, one of the presumed sources of the epidemic, reportedly began to decline after 2011.5,6 Although the rate of prescription opioids has begun to decline slightly over time, it remains unclear whether the diagnosed prevalence of OUD has changed since 2011. Second, we evaluate the proportions of patients with OUD who were prescribed buprenorphine in office-based medical practices over these years. Finally, we seek to identify patient and provider characteristics that are associated with buprenorphine prescribing.

METHODS

Data source and study sample

Data were from the 2006-2015 National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys (NAMCS), administrated by National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.21,22 The NAMCS is an annual, cross-sectional survey of visits to office-based physicians in diverse outpatient care settings, and seeks to represent office-based outpatient medical are in the United States.21 The NAMCS uses a three-stage sampling design,23 which involved selecting primary sampling units (PSUs) based on county- or township-level geographic localities, then physician practices within PSUs, and finally patient visits within physician practices. In each PSU, physicians of all specialties were stratified to nationally represent office-based care provided by physicians, and the survey participation was voluntary. We limited the sample to adults aged 18 or older (n=322,957 unweighted) from the years 2006 to 2015, and then to those who were diagnosed with opioid use disorder (OUD) (n=1,034 unweighted, 0.32%). Using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnostic codes,24 OUD diagnoses included: opioid type dependence (304.00-304.03) and combinations of opioids with any other drug dependence (304.70-304.73). Further details of the survey, including descriptions, questionnaires, sampling methodology and datasets, are publicly available on the NAMCS website.22

Measures

Buprenorphine prescribing.

We examined the first eight medications listed as prescribed in each visit to ensure consistency across years.25–28 Using the generic drug names (i.e., buprenorphine and buprenorphine-naloxone), we created an indicator variable for buprenorphine prescribing.

Demographic covariates.

Patient demographic variables included: age (18-44, 45-64, or 65+), gender, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or other), census region of residence (Northeast, Midwest, South, or West), primary source of health insurance coverage (Private, Medicare, Medicaid, or other), and frequency of visits in the past 12 months (<6 visits or ≥6 visits), which likely indicates an established relationship with the physician for medical treatments.

Clinical covariates.

Clinical factors25–28 included: physician specialty (primary care, psychiatry, or other), provision of psychotherapy (yes or no), benzodiazepine prescription (yes or no), and time spent with a doctor (≤30 minutes or >30 minutes). Using ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes, we constructed an indicator variable for a diagnosis of pain,29,30 which consists of: herpetic pain (053.12 or 729.2), fibromyalgia pain (729.1), musculoskeletal pain (338.XX, 719.4, 780.96), skeletal-spasm pain (728.85, 781.0), pain from diabetes (250.6, 357.2, 337.1), migraine and headache (346.X, 784.0), and other neuropathy-related pain (250.6, 357.2, 337.1, 338.x, 719.4, 780.96, 729.1, 728.85, 781.0, 053.12, 729.2, 352.1, 350.1). Furthermore, we constructed five psychiatric disorder indicator variables and six substance use disorder indicator variables using ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes. For psychiatric disorders,26 we included anxiety (300.00-300.09), depressive disorder (296.20-296.30, 296.90, 296.99, 301-10-301.13, 300.4, 311), bipolar disorder (296.00-296.16, 296.40-296.80, 296.89), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (309.81), and any of the aforementioned psychiatric disorders (yes or no). For substance use disorders,31 we included alcohol use disorder (303.00-303.03, 303.91-303.93, 305.00-305.03), amphetamine use disorder (304.40-304.43, 305.70-305.73), cocaine use disorder (304.20-304.23, 305.60-305.63), cannabis use disorder (304.30-304.33, 305.20-305.23), barbiturate use disorder (304.10-304.13), and any of the aforementioned substance use disorders (yes or no).

Data Analysis

First, we estimated prevalence and national trends of OUD diagnosed among US adults in outpatient medical care settings from two different time frames: from 2006 to 2010 and from 2011 to 2015. We further stratified these trends by physician specialty (primary care, psychiatry, or other), and tested a difference by time period. Second, we estimated trends of buprenorphine prescribing for OUD and tested the differences across time periods. We used a bivariate Pearson’s chi-squared statistic to test differences by years (i.e., 2006-2010 versus 2011-2015).

Third, we compared demographic (e.g., age, gender, and ethnicity) and clinical (e.g., physician specialty and multi-morbidities) characteristics (as stated above) of adult patients with OUD by buprenorphine prescription. Finally, we conducted a multivariable logistic regression analysis to identify factors associated with buprenorphine prescribing among adults with OUD, controlling for other covariates. Covariates were selected based on the bivariate differences at the level of p<0.05. We used Stata MP/6-Core 15.132 for all analyses, and we employed the svy commands in Stata to account for the complex survey sampling design of the NAMCS (i.e., unequal probability of selection, clustering and stratification) in order to present nationally representative visits in office-based medical practices in the US.

RESULTS

National trends of diagnosing opioid use disorder and buprenorphine prescribing in office-based medical practices

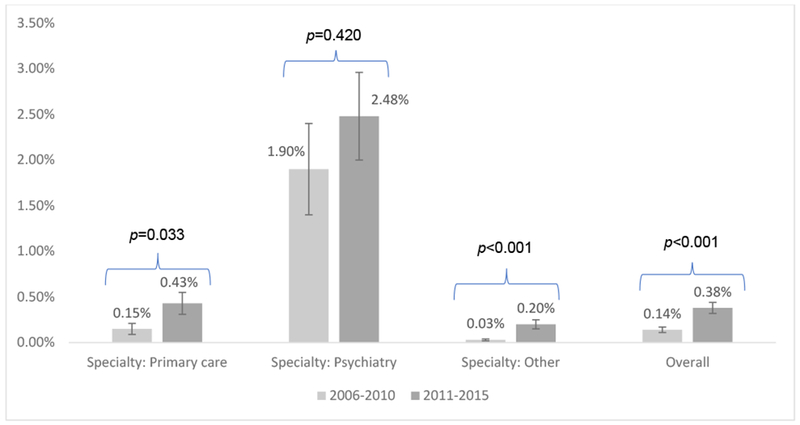

The proportion of medical office visits at which a diagnosis of OUD was made increased almost three-fold from 0.14% of all office visits in 2006-2010 to 0.38% in 2011-2015 (p<0.001) (Figure 1). When stratified by physician specialty, the proportion of visits at which OUD was diagnosed in visits to primary care physicians increased from 0.15% in 2006-2010 to 0.43% in 2011-2015 (p=0.03); among visits to psychiatrists, visits in which OUD was diagnosed increased from 1.90% in 2006-2010 to 2.48% in 2011-2015 (p=0.42); and among visits to all other specialists, visits in which OUD was diagnosed increased from 0.03% in 2006-2010 to 0.20% in 2011-2015 (p<0.001). Furthermore, prescribing of buprenorphine or buprenorphine-naloxone increased from 56.1% of those diagnosed with OUD in 2006-2010 to 73.6% in 2011-2015 (p=0.124).

Figure 1. National trends of opioid use disorder diagnosis among US adults in outpatient care visits by physician specialty, 2006-2015 NAMCS.

Note: Bars represent 95% confidence intervals. P-values are based on the difference of prevalence between 2006-2010 and 2011-2015 using a weight-corrected Pearson’s chi-squared statistic. Other specialties included: general surgery, obstetrics/gynecology, orthopedic surgery, cardiovascular diseases, dermatology, urology, neurology, ophthalmology, otolaryngology, and others.

Selected characteristics of the sample by buprenorphine prescribing

Between 2006 and 2015, a diagnosis of OUD was made at a weighted estimate of more than 2 million physician visits; of these visits, buprenorphine was prescribed at approximately 1.4 million visits. On the other hand, of all visits in which buprenorphine was prescribed, 62.4% had a diagnosis of OUD, and thus, 37.6% did not have a diagnosis of OUD at that visit or had a buprenorphine prescription for other indications, such as severe pain.

The majority of visits at which OUD was diagnosed involved younger adults aged 18-44 (72.7%) and males (61.7%) (Table 1). Adults with OUD who were prescribed buprenorphine were also more likely to be younger adults (78.0%), in comparison to both those who were not prescribed buprenorphine (60.9%) (p=0.001). The majority of visits were made by non-Hispanic whites (84.0%), and they were more likely to receive buprenorphine than others (p<0.001). When compared to adults with OUD who did not receive a prescription for buprenorphine, adults with OUD who were prescribed buprenorphine were more likely to have private insurance (32.9%) with only 14.8% covered by Medicaid as primary sources of payment (p=0.003).

Table 1.

Selected characteristics (weighted column %) of adults aged 18 or older with opioid use disorder by buprenorphine prescription status in office-based visits, 2006-2015 NAMCS.

| Total | Buprenorphine prescription | No prescription provided | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | ||||

| Unweighted sample | 1,034 | 698 | 336 | |

| Weighted visits | 2,055,381 | 1,415,276 | 640,105 | |

| Age | ||||

| 18-44 | 72.7 | 78.0 | 60.9 | 0.001 |

| 45-64 | 25.8 | 21.1 | 36.1 | |

| 65+ | 1.5 | 0.9 | 3.0 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 38.3 | 36.4 | 42.5 | 0.458 |

| Male | 61.7 | 63.6 | 57.5 | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 84.0 | 88.2 | 74.6 | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 4.8 | 3.2 | 8.3 | |

| Hispanic | 8.9 | 5.6 | 16.4 | |

| Othera) | 2.3 | 3.1 | 0.8 | |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | 33.3 | 29.5 | 41.6 | 0.254 |

| Midwest | 17.4 | 20.4 | 10.7 | |

| South | 25.1 | 23.2 | 29.1 | |

| West | 24.3 | 26.9 | 18.6 | |

| Insurance | ||||

| Private | 31.4 | 32.9 | 28.1 | 0.003 |

| Medicare | 6.8 | 4.9 | 11.1 | |

| Medicaid | 21.2 | 14.8 | 35.4 | |

| Otherb) | 40.6 | 47.4 | 25.4 | |

| Repeat of visits in the past 12 months | ||||

| < 6 visits | 36.3 | 33.8 | 41.8 | 0.165 |

| ≥ 6 visits | 63.7 | 66.3 | 58.2 | |

| Physician specialty | ||||

| Primary care | 45.4 | 49.0 | 37.3 | 0.519 |

| Psychiatry | 30.6 | 29.3 | 33.4 | |

| Otherc) | 24.1 | 21.7 | 29.3 | |

| Psychotherapy provided | ||||

| Yes | 31.8 | 34.6 | 25.4 | 0.262 |

| No | 68.2 | 65.4 | 74.6 | |

| Benzodiazepine prescription (%) | 15.6 | 14.7 | 17.4 | 0.511 |

| Time spent with doctor | ||||

| ≤ 30 min. | 81.9 | 79.9 | 86.4 | 0.116 |

| > 30 min. | 18.1 | 20.1 | 13.6 | |

| Co-diagnosis of pain (%) | 11.9 | 12.4 | 10.8 | 0.826 |

| Co-diagnosed psychiatric disorder | ||||

| Any | 29.0 | 24.1 | 39.8 | 0.013 |

| Anxiety | 11.6 | 9.0 | 17.3 | 0.057 |

| Depression | 11.5 | 11.4 | 11.8 | 0.919 |

| Bipolar disorder | 5.8 | 4.3 | 9.1 | 0.107 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 1.5 | 0.4 | 4.2 | <0.001 |

| Co-diagnosed substance use disorder | ||||

| Any | 10.3 | 5.9 | 20.1 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 2.1 | 1.3 | 3.9 | 0.025 |

| Cocaine use disorder | 6.5 | 3.9 | 12.1 | 0.033 |

| Cannabis use disorder | 1.6 | 0.8 | 3.4 | 0.012 |

| Barbiturate use disorder | 0.6 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 0.002 |

| Amphetamine use disorder | 0.5 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 0.010 |

Note:

includes Asians, American Indian/Alaska Natives (AIANs), Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islanders (NHOPI), or other mixed racial/ethnic groups;

includes worker’s compensation, self-pay, no charge, or other;

includes general surgery, obstetrics/gynecology, orthopedic surgery, cardiovascular diseases, dermatology, urology, neurology, ophthalmology, otolaryngology, or other.

Patients prescribed buprenorphine were also significantly less likely than others to be diagnosed with a co-morbid psychiatric disorder or substance use disorder other than OUD as compared to patients who did not have any buprenorphine prescription (p=0.013 and p<0.001, respectively). For instance, while 24.1% of adults with OUD prescribed buprenorphine had a co-morbid psychiatric disorder, 39.8% of adults with OUD not prescribed buprenorphine had such a disorder. In the case of co-diagnosed substance use disorders, only 5.9% of adults with OUD prescribed buprenorphine had such disorders, significantly fewer than among adults with OUD not prescribed buprenorphine (20.1%).

Factors associated with buprenorphine prescribing

Table 2 presents findings from a multivariable logistic regression analysis, which examined factors associated with buprenorphine prescribing. Among adults with OUD, Hispanics were less likely to receive buprenorphine prescriptions (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=0.26; 95% confidence intervals [CI]=0.11, 0.60), but other racial/ethnic minorities who are neither non-Hispanic black nor Hispanic were more likely to receive buprenorphine prescriptions (AOR=4.17; 95% CI=1.31, 13.31). Among adults with OUD, those with Medicaid coverage (AOR=0.27; 95% CI=0.10, 0.74), any psychiatric disorder (AOR=0.45; 95% CI=0.25, 0.83) or any substance use disorder other than OUD (AOR=0.19; 95% CI=0.09, 0.41) were less likely to have any buprenorphine prescription.

Table 2.

Factors associated with buprenorphine prescribing among adults aged 18 or older with opioid use disorder in office-based visits, 2006-2015 NAMCS.

| AOR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18-44 | 1.00 | Reference |

| 45-64 | 0.40 | 0.24, 0.65 |

| 65+ | 0.16 | 0.02, 1.61 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1.00 | Reference |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.36 | 0.10, 1.26 |

| Hispanic | 0.26 | 0.11, 0.60 |

| Othera) | 4.17 | 1.31, 13.31 |

| Insurance coverage | ||

| Medicare and otherb) | 1.00 | Reference |

| Private | 0.77 | 0.30, 1.98 |

| Medicaid | 0.27 | 0.10, 0.74 |

| Psychiatric disorder | ||

| No | 1.00 | Reference |

| Any | 0.45 | 0.25, 0.83 |

| Non-OUD substance use disorder | ||

| No | 1.00 | Reference |

| Any | 0.19 | 0.09, 0.41 |

| Sample size | ||

| Unweighted sample | 973 | |

| Weighted visits | 1,981,495 | |

| F-statistic | 7.79 (p<0.001) | |

Note:

includes Asians, American Indian/Alaska Natives (AIANs), Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islanders (NHOPI), or other mixed racial/ethnic groups;

includes worker’s compensation, self-pay, no charge, or other.

DISCUSSION

Using a nationally representative sample of office-based physician outpatient visits, this study demonstrated an almost tripling of the diagnosis of OUD in office-based medical practice from 0.14% of visits in 2006-2010 to 0.38% from 2011-2015. This increase may reflect the current opioid epidemic and growing physician awareness in the US.

The prescribing rate of buprenorphine for patients with OUD also increased during these time frames, particularly among primary care visits and specialty visits other than visits to psychiatrists. These estimates are of broader relevance than those previously available33–35 because they are based on a nationally representative survey, rather than a sample of individuals covered by employer-based commercial health insurance,33 or more local samples with limited national generalizability.35 A welcome implication of increased utilization of buprenorphine is that office-based physicians appear to be increasingly aware of OUD and responsive to the benefit of buprenorphine use among ambulatory adults over time. In addition, the number of physicians receiving waiver under the DACA of 2000 to prescribe buprenorphine has significantly increased between 2002 and 2011, leading to improving access to care among individuals with OUD.36–38

Second, we found that the proportion of adult patients with OUD receiving buprenorphine increased from 56.1% to 73.6%. Although these changes were not statistically significant in our study (due to limited power), other studies39,40 showed an increase in buprenorphine prescribing in recent years. There are at least two plausible reasons for the recent increase in buprenorphine prescribing. First, both randomized controlled trials and practice guidelines13,41,42 have concluded that buprenorphine should be recognized as an evidence-based first-line pharmacotherapy for OUD and recommended its increased use. Second, both the number of physicians trained in treating OUD and licensed to use buprenorphine (regardless of medical specialty) has increased.37 Although our finding of increased buprenorphine prescribing from 2006-2010 to 2011-2015 was not statistically significant, these developments most likely accounted for the increased use of buprenorphine in adults with OUD in office-based medical care.

On the other hand, our study suggests that adults who received buprenorphine were different from patients with OUD who were not prescribed buprenorphine. They were more likely to be younger adults, non-Hispanic whites or those of multiple racial/ethnic groups, and less likely to have complicating psychiatric or substance use co-morbidities. Thus, while buprenorphine prescribing has increased, it appears to have been preferentially prescribed for relatively younger, healthier individuals. Such findings are consistent with other studies,43–45 which highlighted disparities in access to buprenorphine treatment among adults with opioid dependence. These disparities may be based on individual factors, structural/institutional constraints, or both. For example, individual factors, such as perceptions, cultural beliefs, stigma, and personal vulnerabilities (e.g., disabilities), may inhibit treatment-seeking, leading to disparities in access to care.45 On the other hand, structural or institutional factors, which are rooted in social, political, legal, or service systems, can hinder access to care among individuals of disadvantaged backgrounds.45 For example, in the greater New York City area, buprenorphine and methadone treatments were quite different across neighborhoods.44 Buprenorphine treatment was concentrated in areas with the highest income levels and the highest proportion of non-Hispanic white residents, whereas methadone was most often used by residents in low-income areas.44

Thus, despite the increasing trends favoring buprenorphine prescribing in adults with OUD, its preferential use for younger clients with fewer co-morbidities leaves it uncertain whether this treatment can meet the public health emergency posed by OUD. One recent study46 concluded that the number of buprenorphine-prescribing physicians is too small to address the numbers of patients with OUD needing treatment and, as suggested by our data, those with potentially greater socio-structural and health disadvantages may be under-treated.

Another potential explanation is the proliferation of cash-only buprenorphine treatment clinics across the country.19 One study highlighted a potential concern that many medical offices treating OUD see patients on a cash-only basis and do not accept insurance payments.19 This may have led to disparities in access to care. Thus, specialized programs and financial incentives (e.g., modification of reimbursement policies) may be needed to encourage physicians and other medical professionals to treat all appropriate patients and especially the most vulnerable adults with OUD.

Several limitations of this study require comment. First, clinical and patient information was limited in that we were not able to assess dosing information (e.g., strength, intensity, and duration) of buprenorphine, for example. Future research should investigate if different doses of buprenorphine are associated with differences in quality of care received or clinical outcomes (e.g., relapse rates and adverse effects) among adults with OUD. Second, NAMCS collected patient information in a randomly selected visit, which may not capture diagnoses (e.g., pain and OUD) that may have been made at a different clinic. In such cases, our findings may underestimate some diagnoses. In addition, we relied on the definition of OUD using ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes, and thus the data may have not captured OUD diagnoses that would have been identified by ICD-10 or other criteria. Lastly, while there may be racial/ethnic disparity in access to buprenorphine among adults with OUD, we could not perform sub-group analyses by race/ethnicity due to a small sample size and limited power.

Nevertheless, this study highlights in a nationally representative sample of physician office visits, the increasing trends in both diagnosing OUD and buprenorphine prescribing for adults with OUD in recent years, but also suggests that the most vulnerable patients may not be receiving needed care. Expansion of the workforce prescribing buprenorphine and increasing services targeted at the most vulnerable (e.g., Medicaid beneficiaries and racial/ethnic minorities) are likely to be needed to more fully address this urgent public health crisis.

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Obtained funding: Rhee received funding support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (#T32AG019134).

Role of the funder/sponsor: The funding agency, NIH, had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Data access and responsibility: Rhee had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimers: Publicly available data were obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/index.htm). Analyses, interpretations, and conclusions are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Division of Health Interview Statistics or NCHS of the CDC.

Conflicts of interest: Each author reported no financial or other relationship relevant to this article.

Compliance with ethical standards: This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the authors. All research procedures performed in this study are in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board at Yale University School of Medicine (#2000021850).

REFERENCES

- 1.Quinnones S Dreamland: The true tale of America’s opiate epidemic. Bloomsbury Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65(5051):1445–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Drug Overdose Death Data. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html. Published 2018. Accessed May 17, 2019.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html. Published 2017. Accessed July 3, 2018.

- 5.IQVIA. Medicine use and spending in the U.S.: A review of 2017 and outlook to 2022. https://www.iqvia.com/institute/reports/medicine-use-and-spending-in-the-us-review-of-2017-outlook-to-2022. Published 2018. Accessed July 3, 2018.

- 6.Goodnough A As opioid prescriptions fall, prescriptions for drugs to treat addiction rise. The New York Times; https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/19/health/opioid-prescriptions-addiction.html. Published 2018. Accessed July 3, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saha TD, Kerridge BT, Goldstein RB, et al. Nonmedical Prescription Opioid Use and DSM-5 Nonmedical Prescription Opioid Use Disorder in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(6):772–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies--tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med 2014;370(22):2063–2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014(2):CD002207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krupitsky E, Nunes EV, Ling W, Illeperuma A, Gastfriend DR, Silverman BL. Injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9776):1506–1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009(3):CD002209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gowing L, Ali R, White JM, Mbewe D. Buprenorphine for managing opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;2:CD002025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schuckit MA. Treatment of Opioid-Use Disorders. N Engl J Med 2016;375(4):357–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017;357:j1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Buprenorphine. https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/treatment/buprenorphine. Published 2016. Accessed February 19, 2019.

- 16.Samet JH, Botticelli M, Bharel M. Methadone in Primary Care - One Small Step for Congress, One Giant Leap for Addiction Treatment. N Engl J Med 2018;379(1):7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saloner B, Stoller KB, Alexander GC. Moving Addiction Care to the Mainstream - Improving the Quality of Buprenorphine Treatment. N Engl J Med 2018;379(1):4–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration. Medication Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorders. Final rule. Fed Regist 2016;81(131):44711–44739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Zee A, Fiellin DA. Proliferation of Cash-Only Buprenorphine Treatment Clinics: A Threat to the Nation’s Response to the Opioid Crisis. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(3):393–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wen H, Borders TF, Cummings JR. Trends In Buprenorphine Prescribing By Physician Specialty. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(1):24–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Center for Health Statistics. Ambulatory Health Care Data. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/index.htm Published 2017. Updated 2017 Accessed June 27, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Center for Health Statistics. Ambulatory Health Care Data: Questionnaires, Datasets, and Related Documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/ahcd_questionnaires.htm Published 2017. Updated 2017 Accessed June 28, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Center for Health Statistics. NAMCS Scope and Sample Design. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/ahcd_scope.htm. Published 2015. Accessed June 1, 2019.

- 24.Kelly MM, Reilly E, Quinones T, Desai N, Rosenheck R. Long-acting intramuscular naltrexone for opioid use disorder: Utilization and association with multi-morbidity nationally in the Veterans Health Administration. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;183:111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhee TG, Choi YC, Ouellet GM, Ross JS. National Prescribing Trends for High-Risk Anticholinergic Medications in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rhee TG, Mohamed S, Rosenheck RA. Antipsychotic Prescriptions Among Adults With Major Depressive Disorder in Office-Based Outpatient Settings: National Trends From 2006 to 2015. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rhee TG, Schommer JC, Capistrant BD, Hadsall RL, Uden DL. Potentially Inappropriate Antidepressant Prescriptions Among Older Adults in Office-Based Outpatient Settings: National Trends from 2002 to 2012. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2018;45(2):224–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rhee TG, Capistrant BD, Schommer JC, Hadsall RS, Uden DL. Effects of depression screening on diagnosing and treating mood disorders among older adults in office-based primary care outpatient settings: An instrumental variable analysis. Prev Med 2017;100:101–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barry DT, Sofuoglu M, Kerns RD, Wiechers IR, Rosenheck RA. Prevalence and correlates of co-prescribing psychotropic medications with long-term opioid use nationally in the Veterans Health Administration. Psychiatry Res 2015;227(2-3):324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vijay A, Rhee TG, Ross JS. U.S. prescribing trends of fentanyl, opioids, and other pain medications in outpatient and emergency department visits from 2006 to 2015. Prev Med 2019;123:123–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhalla IP, Stefanovics EA, Rosenheck RA. Clinical Epidemiology of Single Versus Multiple Substance Use Disorders: Polysubstance Use Disorder. Med Care. 2017;55 Suppl 9 Suppl 2:S24–S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stata Statistical Software: Release 15 [computer program]. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberts AW, Saloner B, Dusetzina SB. Buprenorphine Use and Spending for Opioid Use Disorder Treatment: Trends From 2003 to 2015. Psychiatr Serv 2018;69(7):832–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaiser Family Foundations. Medicaid’s role in addressing the opioid epidemic. https://www.kff.org/infographic/medicaids-role-in-addressing-opioid-epidemic/. Published 2018. Accessed July 3, 2018.

- 35.Larochelle MR, Bernson D, Land T, et al. Medication for Opioid Use Disorder After Nonfatal Opioid Overdose and Association With Mortality: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dick AW, Pacula RL, Gordon AJ, et al. Growth In Buprenorphine Waivers For Physicians Increased Potential Access To Opioid Agonist Treatment, 2002-11. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(6):1028–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenblatt RA, Andrilla CH, Catlin M, Larson EH. Geographic and specialty distribution of US physicians trained to treat opioid use disorder. Ann Fam Med 2015;13(1):23–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arfken CL, Johanson CE, di Menza S, Schuster CR. Expanding treatment capacity for opioid dependence with office-based treatment with buprenorphine: National surveys of physicians. J Subst Abuse Treat 2010;39(2):96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stein BD, Gordon AJ, Sorbero M, Dick AW, Schuster J, Farmer C. The impact of buprenorphine on treatment of opioid dependence in a Medicaid population: recent service utilization trends in the use of buprenorphine and methadone. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123(1-3):72–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hadland SE, Wharam JF, Schuster MA, Zhang F, Samet JH, Larochelle MR. Trends in Receipt of Buprenorphine and Naltrexone for Opioid Use Disorder Among Adolescents and Young Adults, 2001-2014. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171(8):747–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alderks CE. Trends in the Use of Methadone, Buprenorphine, and Extended-Release Naltrexone at Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities: 2003-2015 (Update) In: The CBHSQ Report. Rockville (MD)2017:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Connery HS. Medication-assisted treatment of opioid use disorder: review of the evidence and future directions. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015;23(2):63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duncan LG, Mendoza S, Hansen H. Buprenorphine Maintenance for Opioid Dependence in Public Sector Healthcare: Benefits and Barriers. J Addict Med Ther Sci 2015;1(2):31–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hansen HB, Siegel CE, Case BG, Bertollo DN, DiRocco D, Galanter M. Variation in use of buprenorphine and methadone treatment by racial, ethnic, and income characteristics of residential social areas in New York City. J Behav Health Serv Res 2013;40(3):367–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Priester MA, Browne T, Iachini A, Clone S, DeHart D, Seay KD. Treatment Access Barriers and Disparities Among Individuals with Co-Occurring Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders: An Integrative Literature Review. J Subst Abuse Treat 2016;61:47–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stein BD, Sorbero M, Dick AW, Pacula RL, Burns RM, Gordon AJ. Physician Capacity to Treat Opioid Use Disorder With Buprenorphine-Assisted Treatment. JAMA. 2016;316(11):1211–1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]