Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate whether initiating the Family Check-Up (FCU) during early childhood prevented a severe form of psychopathology in adolescence, co-occurring internalizing and externalizing problems, and whether effects operated indirectly through early childhood maternal depression and parents’ positive behavior support.

Method:

Participants were drawn from a randomized controlled trial of the FCU (50.2% FCU, 49.5% girls, 46.6% Caucasian, and 27.6% Black, 13.4% Hispanic/Latino). At ages 2 and 3, mothers self-reported depression and primary caregivers’ (PCs’) positive behavior support was coded by trained observers. PCs, alternate caregivers (ACs) and teachers reported on 14-year-olds problem behaviors. Latent profile analyses (LPAs) identified problem behavior groups for each reporter, which were outcomes in multinomial logistic regressions (PC N = 672; AC N = 652; teacher N = 667).

Results:

LPAs identified a low problem, internalizing ‘only,’ externalizing ‘only,’ and co-occurring problem group for each reporter. For PC- and AC-reported outcomes, the FCU predicted a lower likelihood that adolescents belonged to the co-occurring group relative to the low problems, externalizing ‘only’ (p<0.05) and internalizing ‘only’ groups (p<0.05 for PC, p<0.10 for AC); these effects operated through maternal depression (p<0.05). For teacher-reported outcomes, the FCU predicted a lower likelihood that adolescents belonged to the co-occurring group relative to the low problems, internalizing ‘only’ and externalizing ‘only’ groups (p < 0.05); effects operated through positive behavior support (p<0.05).

Conclusions:

Early delivery of the FCU indirectly prevented adolescents’ co-occurring internalizing/externalizing problems in both home and school contexts by improving the quality of the early home environment.

Keywords: Family Check-Up, Co-occurrence, Adolescence, Maternal Depression, Positive Behavior Support

The co-occurrence of internalizing and externalizing problems is a common clinical phenomenon in adolescence (Angold, Costello, & Erkanli, 1999). This phenomenon, often referred to as heterotypic comorbidity or co-occurrence, has been associated with a host of detrimental outcomes. Adolescents showing heterotypic co-occurrence have been shown to exhibit greater overall impairment, social dysfunction, academic problems, suicide attempts, and sexual promiscuity than those without (Dishion, 2000; Fanti & Henrich, 2010; Lewinsohn, Rohde, & Seeley, 1995). Heterotypic co-occurrence in adolescence also has been associated with maladaptive outcomes in adulthood, including symptoms of anxiety and depression, somatization, aggression, antisociality, and borderline personality disorder (Diamantopoulou, Verhulst, & van der Ende, 2011; Zanarini et al., 1998).

Prevention of Adolescents’ Co-occurring Internalizing and Externalizing Problems

Despite the known severity of future outcomes for adolescents with co-occurring problem behaviors, relatively few studies have examined whether psychosocial intervention reduces or prevents this form of psychopathology. However, the few studies that have focused on this outcome have shown promising results. Using data across six randomized trials of a parent-training intervention for 3-to-8 year olds with early conduct problems, Beauchaine, Webster-Stratton, and Reid (2005) found that youths with co-occurring anxiety and depression showed more rapid improvements in externalizing behaviors than those without. Similarly, Kazdin and Whitley (2006) demonstrated that, among youths with oppositional defiant or conduct disorder, those who had two or more comorbid disorders (including internalizing disorders) showed greater improvements following parent management training than children with one or fewer comorbid disorders. Zhang and Slesnick (2017) also found that 8-to-16 year olds who received ecologically-based family therapy were more likely to transition from the co-occurring internalizing/externalizing group to the internalizing “only” group at an 18 month follow-up.

However, it is less clear whether early prevention can offset co-occurring internalizing/externalizing problems, which is important because this form of co-occurrence may emerge as early as toddlerhood and has been shown to persist into adolescence (Fanti & Henrich, 2010). Initiating prevention as early as toddlerhood may also be important because toddlerhood is a time of marked transition during which families may require more support. New challenges during the toddler stage include increased physical mobility and limited understanding of potential consequences, which places increased demands on parents in terms of child monitoring and setting limits (Gardner, Sonuga-Barke, & Sayal, 1999). Shifts in parenting may be partially responsible for decreasing childrearing pleasure between the first and second years of life (Fagot & Kavanagh, 1993). Because successful adaptation to this transition may shape functioning in subsequent developmental stages (Shaw & Gross, 2008), early prevention for those at risk could be key in changing the course of co-occurring problems in adolescence. In turn, the successful prevention of this severe form of psychopathology in adolescence may place at-risk youth on more positive adjustment trajectories through adolescence and beyond.

Although few studies have tested the effect of early preventive interventions on adolescents’ co-occurring problems, one randomized controlled trial found that at-risk toddlers who participated in a family-based prevention program, the Family Check-Up (FCU), were more likely to transition from the co-occurring group at age 2 to the low problems group by age 4, although analyses were limited to one- and two-year follow-ups of child adjustment (d = 2.82; Connell et al., 2008). Based on promising intervention effects during early childhood, a primary goal of this study was to examine, in the same sample, whether initial intervention effects of the FCU continued to prevent the development of co-occurring problems in adolescence.

The Family Check-Up

The Family Check-Up (FCU) is a brief, family-centered preventive intervention developed by Dishion and Kavanagh (2003) for youth at high-risk for problem behaviors. The FCU is unique from other family-centered interventions because it is principally designed to promote families’ motivation to change through motivational interviewing strategies. As part of the FCU program, families receive a comprehensive assessment of youth and family functioning, as well as feedback to assess discrepancies between current and desired levels of functioning. Based on the discussion, families are presented with a flexible and tailored menu of change strategies to help achieve desired improvements. The brief nature of the FCU promotes a health maintenance model of care, which emphasizes periodic contact for the purpose of maintaining good health, as opposed to treating health at less frequent intervals only as problems arise.

Prior work using the FCU in the current sample has demonstrated intent-to-treat (ITT) effects during early childhood on growth in externalizing (Dishion et al., 2008) and internalizing (Shaw, Connell, Dishion, Wilson, & Gardner, 2009) problems (separately), and as mentioned previously, co-occurring externalizing and internalizing problems (Connell et al., 2008). ITT intervention effects have continued to be found on externalizing problems through middle childhood (Dishion et al., 2014) and adolescence (Shaw et al., 2018).

Parent Factors as Mediating Mechanisms on Later Problem Behaviors

In addition to examining the direct effects of the FCU, prior research has examined mediators underlying the mechanisms of improved child behavior. As an example, the FCU has been shown to reduce growth in internalizing and externalizing problems in early childhood indirectly through decreases in maternal depressive symptoms (Shaw et al., 2009). The FCU has also been shown to reduce growth in externalizing problems through increases in caregivers’ positive behavior support (i.e., parenting that is warm, involved, positively reinforces skill development, and structures situations to promote self-regulation; Dishion et al., 2008). Indirect effects of the FCU on multiple informants’ reports of child depressive symptoms during middle childhood were also found via reductions in maternal depression between child ages 2 and 3 (Reuben, Shaw, Brennan, Dishion, & Wilson, 2015).

Because the FCU operated through maternal depression and positive behavior support earlier in development, these indirect effects could also extend to co-occurring problem behaviors during adolescence. Such effects are important to consider because they may reveal more nuanced effects operating over long spans of time. Moreover, to inform the developmental timing of targets for prevention programs, it is important to understand whether toddlerhood represents a sensitive period during which changing parenting factors could influence outcomes into adolescence. For example, Shaw, Bell, & Gilliom, (2000) showed that maternal depression and other proximal indicators of family stress (e.g., parenting daily hassles, social support) assessed during the toddler period were more predictive of teacher-reported child conduct problems at age 8 than when assessed during the preschool or early school-age periods. The authors interpreted this result from a development context, based on the “terrible twos” perhaps being a more accurate barometer of predicting parental reaction to family stress than later age periods when children are more socialized and undergo more gradual biological and cognitive changes until early adolescence (Shaw & Gross, 2008). Research on the risk factors underlying co-occurring problems are consistent with the possibility that maternal depression and positive behavior support are important mediators. Parents of youth with co-occurring internalizing and externalizing problems have been found to be more depressed and hostile, and less likely to be warm and effective in discipline than parents of youth without co-occurring problems (Basten et al., 2013; Fanti & Henrich, 2010; Wang, Eisenberg, Valiente, & Spinrad, 2015). Thus, we examined whether the FCU indirectly prevented co-occurring problems in adolescence by improving early childhood caregiver adjustment and parenting.

Current Study

We examined whether the FCU, when initiated at age 2, reduced the likelihood that 14-year-olds would exhibit co-occurring internalizing and externalizing problems relative to other problem behavior groups, accounting for children’s initial levels of problem behaviors. We employed latent profile analysis to identify latent groups underlying various forms of internalizing and externalizing problems in adolescence. Based on findings from prior studies (Connell et al., 2008), we expected to find four groups representing: (1) co-occurring problems, (2) externalizing problems “only,” (3) internalizing problems “only,” and (4) low problems. We tested whether indirect effects of the FCU on adolescents’ problem behavior would be evident via improvements in maternal depression or positive behavior support from ages 2–3, based on these parent factors’ established importance (Goodman et al., 2011; Webster-Stratton & Hammond, 1998) and earlier follow-ups of the present cohort (Dishion et al., 2008; Reuben et al., 2015). We hypothesized that those who received the FCU would be more likely to belong to the externalizing “only,” internalizing “only,” and low problem groups than to the co-occurring group, and to the low problem group than the externalizing or internalizing “only” groups. Although we tested for intention-to-treat (ITT) intervention effects, based on finding less consistent ITT effects on depressive symptoms during middle childhood in this cohort, we expected to find indirect rather than direct effects of the FCU on adolescent problem behavior.

Methods

Participants

Participants were drawn from a sample of 731 caregiver-child dyads recruited between 2002 and 2003 from Women, Infants, and Children Nutritional Supplement (WIC) programs in and around Pittsburgh, PA, Eugene, OR, and Charlottesville, VA (Dishion et al., 2008). The WIC Program provides nutritional and health services for income-eligible families who are pregnant and/or have children aged 5 or younger. Families were invited to participate if they had a child between age 2 years 0 months and 2 years 11 months and if they scored at or above one SD in at least two of the following domains: child behavior (conduct problems, high-conflict relationships with adults), family problems (maternal depression, daily parenting challenges, substance-use problems, teen parent status), and sociodemographic risk (low education achievement and low family income). Of the 1,666 families who had children in the appropriate age range and were contacted at WIC sites, 879 were eligible (52% in Pittsburgh, 57% in Eugene, and 49% in Charlottesville) and 731 (83.2%) agreed to participate (88% in Pittsburgh, 84% in Eugene, and 76% in Charlottesville). Institutional Review Boards at all participating universities approved this research and primary caregivers (PCs) provided informed consent.

Of the 731 families (49% female children), 272 (37%) were recruited in Pittsburgh, 271 (37%) in Eugene, and 188 (26%) in Charlottesville. PCs self-identified as belonging to the following ethnic groups: 28% African American, 50% European American, 13% biracial, and 9% other groups (e.g., American Indian, Native Hawaiian). Thirteen percent of the sample reported being Hispanic American. In the initial screening, more than two-thirds of the families had an annual income of less than $20,000, and the average number of family members per household was 4.5 (SD = 1.63). Forty-one percent of PCs had a high school or general education diploma, and an additional 32% had 1–2 years of post-high school training.

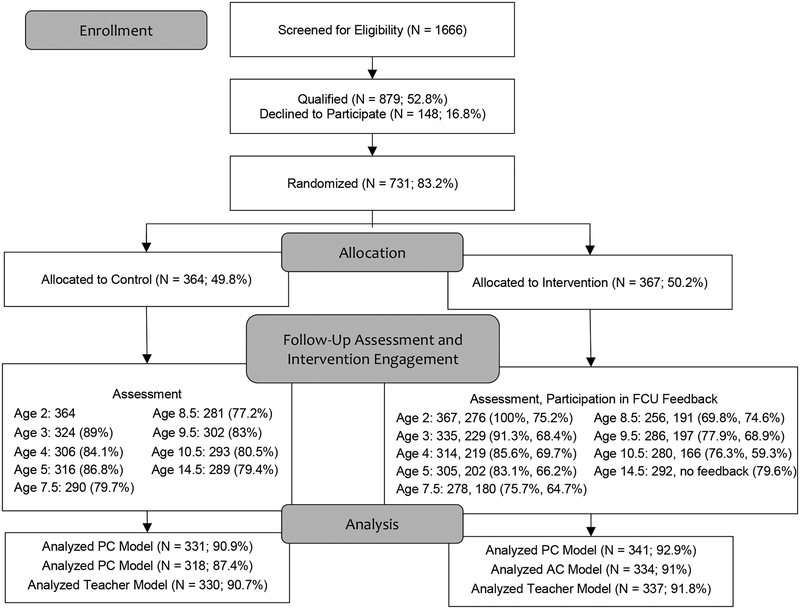

Of the 731 families who initially participated, 659 (90%) participated at the age 3 follow-up and 578 (79.1%) at the age 14 follow-up. See Figure 1 for a flow diagram of progress through trial phases. At ages 3 and 14, selective attrition analyses revealed no significant differences in project site; children’s race, ethnicity, or gender; maternal depression, age 2 externalizing or internalizing behaviors (parent reports), or income. One participant was excluded from analyses because differing caregivers reported on maternal depression at ages 2 and 3. The sample size was 672 for the PC model, 652 for the AC model, and 667 for the teacher model.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of progress through phases of FCU trial. Participation in FCU feedback is participation in the third session. The assessment always occurred before the feedback session. The targeted interval between the assessment and feedback sessions was three weeks.

Intervention

Participants were randomized to the Family Check-Up (FCU) condition (N = 367) or WIC services as usual (i.e., control group, N = 364). See Dishion et al. (2008) for a more detailed description of the FCU. The FCU is a three-session intervention with follow-up services emphasizing specific family management practices (Dishion & Stormshak, 2007). Although in clinical practice, the ordering of the first two sessions is reversed to ensure assessment material is gathered before contact with interventionists for those in the intervention condition, for purposes of the current RCT, the first session involved in-home assessments with an examiner (pre-randomization) that included observations of parent-child interactions, interviews, and questionnaires. In the second session (i.e., get-to-know-you session), the parent consultant conducted an interview to explore caregivers’ concerns and needs. In the third session (i.e., the feedback session), the parent consultant shared assessment findings regarding areas of strengths and challenges, engaged in a motivation-enhancing discussion about promoting positive change, and provided a menu of resources such as mental health, school-based services, and job training. Following the feedback session (the formal end of the FCU), parents had the option to engage in follow-up treatment sessions, which were conducted in-person with individual families typically at their homes, and in which the child was infrequently involved. The Everyday Parenting curriculum was used to guide follow-up sessions, which teaches family management techniques to support children’s positive behaviors, set healthy limits, and build family relationships (Dishion, Stormshak, & Kavanagh, 2011). On average, participants engaged in 1–4 (range = 0–77) follow-up sessions per year and spent an average of 1 hour and 20 minutes (SD = 51) in each session across all ages of FCU implementation (annually from child ages 2–10).

Measures

Maternal depression.

At age 2 and 3 home assessments, mothers reported their past week depressive symptoms on a scale ranging from 0 (less than a day) to 3 (5–7 days) using the Center for Epidemiological Studies on Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), a 20-item self-report measure. Items were summed to create an overall depressive symptoms score, which was standardized to facilitate interpretation. Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.73 at age 2 and 0.77 at age 3.

Positive behavior support.

During age 2 and 3 home assessments, PCs (97.7% mothers) and children participated in a series of recorded interaction tasks from which positive behavior support scores were extracted. As described in Dishion et al. (2008), tapes were coded by undergraduates using the Relationship Process Code (Jabson, Dishion, Gardner, & Burton, 2004). Four scales (described below) were shown to form a single latent factor in prior research (Dishion et al., 2008) and were standardized and summed to form the final positive behavior support variable; this variable was also standardized to facilitate interpretation. (1) Parental involvement was measured using home examiners’ ratings on items from the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment inventory (Bradley, Corwyn, McAdoo, & Garcia Coll, 2001). (2) Positive behavior support was coded as the duration of positive reinforcement, prompts and suggestions of positive activities, and positive structure. (3) Engaged parent-child interaction time was the average length of parent-child sequences involving talking or physical interactions. (4) Proactive parenting was rated by coders using six items that tapped the tendency to anticipate potential problems and to provide prompts or structural changes to prevent children becoming upset and/or involved in problem behavior.

Internalizing and externalizing problems.

PCs reported on children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors at age 2 using the Child Behavior Checklist for ages 1.5–5 (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000). PCs and ACs (i.e., fathers, grandmothers, aunts, and other adults involved in caregiving) reported on these problems at age 14 using the Child Behavior Checklist for ages 6–18 (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) and teachers using the Teacher Report Form (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). Age 14 T-scores of the following subscales were used in reporter-specific latent profile analyses: withdrawn/depressed, anxious/depressed, somatic complaints, rule-breaking, aggression, and attentional problems. PC-reported T-scores of broadband internalizing and externalizing problems at age 2 were baseline control variables. T-scores are age-standardized (M(SD) = 50(10)). Syndrome subscale T-scores ranging from 65-to-70 are in the borderline clinical range and scores above 70 are in the clinical range (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001).

Demographics.

At age 2, PCs reported child sex (0=male, 1=female), child race (Caucasian=1, other race/ethnicity=0), urbanicity (0=rural, 1=suburban, 2=urban) and income.

Data Analytic Plan

Analyses were conducted in Mplus version 7.11 using maximum likelihood with robust standard errors, full information maximum likelihood (FIML), and Montecarlo integration (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2013). FIML produces unbiased parameter estimates and standard errors under missing at random and missing completely at random (MCAR). Data were shown to be MCAR under Little’s MCAR test (χ2(51) = 55.68, p = 0.30). To identify groups with distinct patterns of internalizing and externalizing problems, we used latent profile analysis (LPA) because it has been shown to be superior to traditional cluster analyses in detecting latent taxonomy (McLachlan & Peel, 2000), it accommodates continuous measures, and our interest in using a person-oriented method to best capture co-occurrence of internalizing and externalizing problems. Each LPA was specific to one reporter. Indicators of reporter-specific LPAs were PC, AC, and teacher reports of adolescents’ anxious/depressed, withdrawn/depressed, somatic complaints, rule-breaking, aggression, and attentional problem T-score subscales. We used several criteria to determine the optimal number of groups. We compared one-through five-group models on several indicators of model fit: Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), adjusted BIC, bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT), and log likelihoods (Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthén, 2007). We also considered group proportion sizes (>5%) and the theoretical relevance and utility of identified groups (Muthén & Muthén, 2000).

Note that our choice of modeling reporter-specific LPAs rather than a single LPA combining across reporters was based on several findings from our data. First, PC and AC reports of problem behaviors did not correspond strongly with teacher reports of the same subscales, with correlations ranging from r = 0.15 to 0.26 for internalizing, and r = 0.32 to 0.43 for externalizing. Second, combining reporters may miss important contextually-specific problem behaviors. Third, although the concordance between PC and AC reports of problem behaviors was stronger than between parents and teachers, we did not combine PC and AC because substantially fewer ACs (n = 303) reported on problem behaviors than PCs (n = 552).

An ITT method was used to study the effect of the FCU. To test the effect of the FCU on adolescents’ problem behavior group and mediation by maternal depression and positive behavior support, we considered two approaches: R3Step and saving adolescents’ ‘most likely group membership’ to use as a manifest outcome. Unlike R3Step, saving the ‘most likely group membership’ allows for direct tests of mediation, central to this study’s goals. However, under high classification error, associations between ‘most likely group membership’ and covariates may be downwardly biased (Bolck, Croon, & Hagenaars, 2004). Thus, we evaluated the entropy (measure of classification certainty) of final LPAs to determine whether using the ‘most likely group membership’ as an outcome was appropriate; otherwise, R3Stp was used.

Multinomial logistic regressions tested predictors of group membership. We regressed group membership on predictors (FCU), mediators (age 3 maternal depression, positive behaviors support), baseline controls (PC report of age 2 internalizing and externalizing problems), and demographic covariates (gender, child race/ethnicity, urbanicity, family income). We also regressed maternal depression and positive behavior support on FCU, covariates, and age 2 maternal depression or positive behavior support, respectively. The following planned contrasts were tested: (1) co-occurring problems compared to all other groups and, (2) low problems compared to all other groups. The joint significance test was used to test mediation because it has been shown to provide the best balance of Type I error and statistical power across of range of methods (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002).

Results

Descriptive statistics.

See Table 1 for sample sizes, means, and standard deviations of all study variables. As expected based on eligibility criteria, compared to established norms, participants in this study showed elevated risk on several variables. The average CES-D score on maternal depression was higher than the clinical cutoff (16; Radloff, 1977) at the age 2 assessment and just below the cutoff at age 3. The average T-scores on internalizing and externalizing subscales at ages 2 and 14 ranged from 53.83-to-59.49, which are approximately .4 to 1.0 standard deviations higher than normative scores (50) based on community samples of non-referred children (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000, 2001).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Continuous Variables | N | M(SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Income (age 2) | 729 | 3.86(2.12) |

| Maternal Depression (Age 2) | 715 | 16.66(10.63) |

| Maternal Depression (Age 3) | 641 | 15.55(11.00) |

| Positive Behavior Support (Age 2) | 731 | −0.01(0.74) |

| Positive Behavior Support (Age 3) | 643 | −0.001(0.764) |

| Internalizing Problems (PC Age 2) | 730 | 56.33(8.52) |

| Externalizing Problems (PC Age 2) | 730 | 59.49(8.21) |

| Anxious/Depressed (PC Age 14) | 552 | 56.82(8.62) |

| Withdrawn/Depressed (PC Age 14) | 552 | 58.57(9.15) |

| Somatic Complaints (PC Age 14) | 553 | 56.98(8.20) |

| Rule-breaking (PC Age 14) | 548 | 56.34(6.89) |

| Aggression (PC Age 14) | 552 | 58.14(9.76) |

| Attentional Problems (PC Age 14) | 553 | 59.05(9.40) |

| Anxious/Depressed (AC Age 14) | 303 | 54.95(7.15) |

| Withdrawn/Depressed (AC Age 14) | 306 | 56.87(8.0) |

| Somatic Complaints (AC Age 14) | 303 | 55.59(7.32) |

| Rule-breaking (AC Age 14) | 301 | 55.24(6.39) |

| Aggression (AC Age 14) | 305 | 56.87(8.42) |

| Attentional Problems (AC Age 14) | 304 | 56.86(8.48 |

| Anxious/Depressed (Teacher Age 14) | 490 | 55.17(6.44) |

| Withdrawn/Depressed (Teacher Age 14) | 500 | 57.06(8.21) |

| Somatic Complaints (Teacher Age 14) | 492 | 54.21(6.80) |

| Rule-breaking (Teacher Age 14) | 494 | 56.77(7.65) |

| Aggression (Teacher Age 14) | 499 | 56.83(8.63) |

| Attentional Problems (Teacher Age 14) | 500 | 53.83(4.43) |

| Dichotomous Variables | % | |

| Family Check-Up vs. no intervention | 731 | 50.2% Family Check-Up |

| Gender | 731 | 49.5% Girls |

| 25.7% rural | ||

| Urbanicity | 731 | 37.1% suburban |

| 37.2% urban | ||

| 46.6% Caucasian | ||

| 27.6% Black/African | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | American | |

| 13.4% Hispanic/Latino | ||

| 12.4% Other |

Notes. PC: Primary caregiver. AC: Alternate caregiver.

Zero-order correlations.

Table 2 shows zero-order correlations among predictors, mediators, and indicators of the LPAs. FCU was marginally significantly correlated with greater positive behavior support at child age 3, but was not significantly related to maternal depression at child age 3 or with any measures of adolescents’ problem behavior. Correlations among maternal depression and age 14 problem behaviors were significant for all PC and the majority of AC reports, but not for the majority of teacher reports. Positive behavior support at age 3 was significantly and negatively correlated with PC- and AC-reported externalizing problems at age 14 and with all teacher-reported problem behaviors at age 14 except somatic complaints.

Table 2.

Zero-order correlations among FCU, mediators, and outcome variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.FCU | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2.Mom Dep | −0.06 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3.PBS | 0.07 | −0.17** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 4.Anx/Dep P | −0.05 | 0.21** | 0.02 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 5.Withdraw P | −0.01 | 0.16** | −0.03 | 0.64** | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 6.Somatic P | 0.01 | 0.14** | 0.03 | 0.58** | 0.45** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 7.Rule Break P | 0.003 | 0.16** | −0.09* | 0.45** | 0.48** | 0.34** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 8.Aggression P | −0.05 | 0.20** | −0.09 | 0.55** | 0.53** | 0.40** | 0.78** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 9.Attention P | −0.03 | 0.16** | −0.10* | 0.53** | 0.53** | 0.35** | 0.60** | 0.67** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 10.Anx/Dep A | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.001 | 0.39** | 0.29** | 0.30** | 0.10 | 0.21** | 0.22** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 11.Withdraw A | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.33** | 0.48** | 0.28** | 0.15** | 0.24** | 0.25** | 0.64** | 1 | |||||||||

| 12. Somatic A | 0.07 | 0.17** | 0.03 | 0.30** | 0.28** | 0.41** | 0.07 | 0.16** | 0.16** | 0.64** | 0.57** | 1 | ||||||||

| 13.Rule Break A | −0.06 | 0.14* | −0.15** | 0.27** | 0.28** | 0.15** | 0.63** | 0.56** | 0.41** | 0.35** | 0.36** | 0.25** | 1 | |||||||

| 14.Aggression A | −0.02 | 0.19** | −0.16** | 0.35** | 0.33** | 0.20** | 0.53** | 0.63** | 0.43** | 0.51** | 0.46** | 0.36** | 0.78** | 1 | ||||||

| 15.Attention A | −0.06 | 0.16** | −0.09 | 0.26** | 0.28** | 0.15* | 0.26** | 0.33** | 0.52** | 0.51** | 0.54** | 0.41** | 0.53** | 0.61** | 1 | |||||

| 16.Anx/Dep T | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.11* | 0.21** | 0.18** | 0.10* | 0.15** | 0.24** | 0.24** | 0.17** | 0.18** | 0.10 | 0.15* | 0.14* | 0.18** | 1 | ||||

| 17.Withdrawn T | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.13** | 0.15** | 0.26** | 0.16** | 0.12* | 0.18** | 0.18** | 0.08 | 0.23** | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.14* | 0.47** | 1 | |||

| 18.Somatic T | 0.09 | 0.05 | −0.09 | 0.17** | 0.16** | 0.23** | 0.22** | 0.26** | 0.25** | 0.16* | 0.19** | 0.15* | 0.15* | 0.21** | 0.22** | 0.39** | 0.38** | 1 | ||

| 19.Rule Break T | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.20** | 0.10* | 0.12** | 0.10* | 0.43** | 0.33** | 0.26** | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.32** | 0.25** | 0.20** | 0.35** | 0.29** | 0.36** | 1 | |

| 20.Aggression T | −0.02 | 0.07 | −0.17** | 0.10* | 0.11* | 0.04 | 0.40** | 0.41** | 0.32** | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.40** | 0.33** | 0.26** | 0.46** | 0.22** | 0.38** | 0.77** | 1 |

| 21.Attention T | 0.01 | 0.10* | −0.16** | 0.14** | 0.17** | 0.13** | 0.23** | 0.24** | 0.32** | 0.14* | 0.19** | 0.08 | 0.25** | 0.21** | 0.32** | 0.40** | 0.43** | 0.40** | 0.54** | 0.52** |

Notes.

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05.

Mom Dep: Maternal Depression at age 3. PBS: Positive Behavior Support at age 3. Problem behavior subscales in the table were all measured at age 14. P: Primary caregiver. A: Alternate caregiver. T: Teacher.

Latent profile analyses.

BICs, adjusted BICs, and log likelihoods continued to improve with increasing groups. BLRT p-values were significant for all models, indicating more groups showed increasingly better fit. However, across reporters, the five group models each had one group containing fewer than 5% of the sample, did not include a group that was substantively different from the four group models, and only showed minimal decreases in BICs and adjusted BICs when compared to four group models. The four-group models were selected for all three reporters (see Supplementary Table 1). Visual inspection of the latent profiles suggested that the four groups represented: (1) low problems, (2) elevated internalizing relative to externalizing problems (hereafter called internalizing “only” to facilitate readability), (3) elevated externalizing relative to internalizing problems (hereafter called externalizing “only”), and (4) co-occurring problems (see Supplementary Figure 1 for visual depiction and Supplementary Table 2 for mean T-scores of each group). Although the mean T-scores of internalizing “only” and externalizing “only” groups never surpassed the clinical cut-off of 70 for their respective syndrome scales across reporters, many (i.e., 27%) were in the borderline clinical range; thus, it would be inaccurate to categorize these adolescents as showing no problem behaviors (i.e., as equivalent to the low problem group). Final LPAs showed high entropy (ranging from 0.90-to-0.93), suggesting high classification certainty and lessening concerns of biased relationships (Clark & Muthén, 2009). The ‘most likely group membership’ variable was saved as a manifest outcome variable for regression analyses.

Final model.

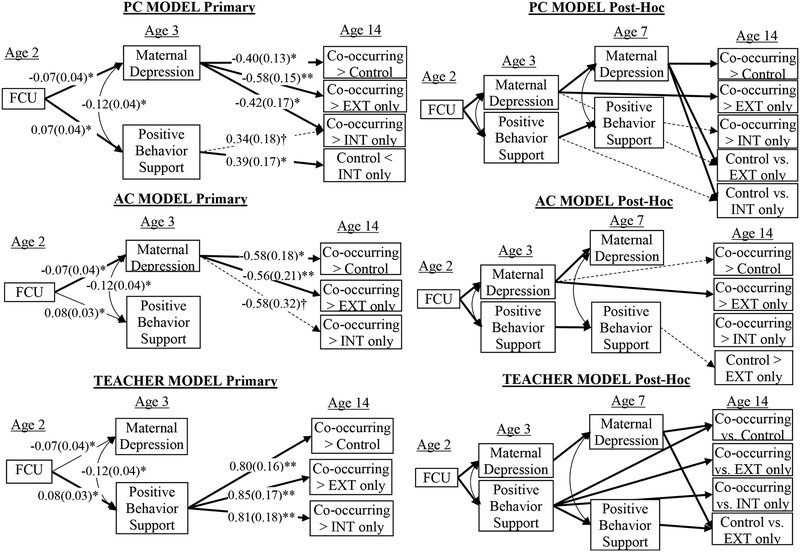

See Figure 2. Standardized coefficients and standard errors are reported in the following text for the prediction of maternal depression and positive behavior support. Because effects differed only slightly across reporter-specific models due to small differences in sample size, statistics are presented as a range or a single number if coefficients were identical.

Figure 2.

Structural equation models for primary caregiver (PC), alternate caregiver (AC), and teacher models. **p < 0.001, *p < 0.05, †p < 0.10. Bold lines: significantly mediated paths according to joint significance test. Dashed lines: p < 0.10. Numeric values: standardized regression coefficients (standard errors). Age 2 maternal depression and positive behavior support were controlled in predicting age 3 levels of these variables. Age 2 PC-reported INT and EXT were controlled in predicting age 14 outcomes.

Effects on mediators.

In all models, FCU significantly (p < .05) predicted lower levels of maternal depression (β = −.07, SE =.04; d = .16, 95% CI [0, .31]) and higher levels of positive behavior support at age 3 (β =.07 −.08, SE =.03; d = .14, 95% CI [−0.01, .30]). In terms of covariates, maternal depression at age 3 was significantly (p < .05) predicted by maternal depression at age 2 (β =.44, SE =.04) but not by gender (β = .06, SE = .04), race/ethnicity (β = .04, SE = .04), familial income (β = −.04 to −.05, SE = .04), or urbanicity (β = .004 −.01, SE = .04). Positive behavior support at age 3 was significantly (p <.05) predicted by higher levels of positive behavior support at age 2 (β =.51, SE =.03), lower levels of urbanicity (β = −.13, SE = .03) higher levels of familial income (β = .08 - .09, SE =.04), and Caucasian race/ethnicity (β =.08 −.09, SE = .03), but not by gender (β = −.05, SE = .03).

Intervention and parent-level effects on adolescents’ problem behaviors.

See Table 3 for results. The FCU did not directly predict adolescents’ group membership in any of the models. In both PC and AC models, adolescents with higher levels of maternal depression were significantly less likely to belong to the low problems (PC OR = .54, 95% CI [.38, .77]; AC OR = .60, 95% CI [.35, 1.02]) and externalizing “only” groups (PC OR = .50, 95% CI [.34, .74]; AC OR = .56, 95% CI [.34, .90]) than to the co-occurring group. Significantly in the PC model but marginally significantly in the AC model, adolescents with higher levels of maternal depression were less likely to belong to the internalizing “only” group than to the co-occurring group (PC OR = 0.61, 95% CI [.42, .89]; AC OR = .54, 95% CI [.32, 0.90]). Across all models, a one SD increase in maternal depression corresponded to a 39–50% decrease in the odds of belonging to all other groups when compared to the co-occurring group. In the PC model only, adolescents with higher levels of positive behavior support were more likely to belong to the internalizing “only” group than the low problems group (significant; OR = 1.35, 95% CI [1.4, 1.74]) and the co-occurring group (marginally significant). In the teacher model, adolescents with higher levels of positive behavior support were significantly more likely to belong to the externalizing “only” (OR = 2.07, 95% CI [1.33, 3.24]), internalizing “only” (OR = 2.40, 95% CI [1.44, 3.98]), and low problems (OR = 2.27, 95% CI [1.49, 3.48]) groups than to the co-occurring group. Across the models, a one SD increase in positive behavior support corresponded to a 107–140% increase in the odds of belonging to all other groups when compared to the co-occurring group. Maternal depression did not predict group membership in the teacher model. Note that more data was estimated in the AC model due to higher levels of AC missingness. The AC model that did not estimate missing data produced the same results (results available upon request)

Table 3.

Path coefficients for effects on adolescents’ problem behavior

| Primary Caregiver (n = 672) | Alternate Caregiver (n = 652) | Teacher (n = 667) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO vs. Low | CO vs. INT | CO vs. EXT | CO vs. Low | CO vs. INT | CO vs. EXT | CO vs. Low | CO vs. INT | CO vs. EXT | |

| FCU | 0.11(0.14) | 0.10(0.19) | 0.04(0.19) | 0.20(0.27) | 0.44(0.31) | 0.23(0.27) | −0.02(0.21) | −0.13(0.22) | −0.09(0.27) |

| Mom Dep | −0.40(0.13)* | −0.42(0.17)* | −0.58(0.15)** | −0.56(0.21)* | −0.58(0.32)† | −0.58(0.18)** | −0.03(0.24) | 0.14(0.24) | 0.10(0.28) |

| PBS | 0.06(0.14) | 0.34(0.18)† | 0.03(0.20) | 0.32(0.36) | 0.41(0.45) | 0.11(0.38) | 0.79(0.16)** | 0.81(0.18)** | 0.85(0.17)** |

| Gender | −0.08(0.15) | 0.09(0.20) | −0.19(0.20) | −0.05(0.28) | 0.21(0.35) | −0.07(0.30) | −0.05(0.20) | 0.12(0.22) | 0.09(0.26) |

| Race | −0.19(0.14) | −0.05(0.19) | −0.26(0.19) | −0.48(0.26)† | −0.47(0.34) | −0.61(0.31)* | 0.27(0.21) | 0.32(0.22) | −0.24(0.31) |

| Income | 0.22(0.16) | 0.28(0.21) | 0.09(0.23) | 0.05(0.31) | −0.14(0.43) | −0.17(0.33) | −0.06(0.19) | 0.003(0.22) | −0.17(0.22) |

| Urbanicity | −0.22(0.14)* | −0.32(0.18)† | −0.34(0.18)† | 0.35(0.27) | 0.04(0.33) | 0.14(0.28) | 0.014(0.18) | 0.32(0.20) | 0.27(0.23) |

| PC INT | −0.45(0.17)* | −0.22(0.25) | −0.59(0.21)** | −0.54(0.34) | −0.10(0.55) | −0.31(0.42) | 0.48(0.23)* | 0.35(0.26) | 0.50(0.27)† |

| PC EXT | −0.39(0.14)* | −0.32(0.20) | 0.05(0.20) | 0.16(0.36) | 0.14(0.44) | 0.55(0.30)† | −0.56(0.21)* | −0.42(0.24)† | −0.49(0.30) |

| -- | Low vs. INT | Low vs. EXT | -- | Low vs. INT | Low vs. EXT | Low vs. INT | Low vs. EXT | ||

| FCU | -- | −0.06(0.16) | −0.16(0.18) | -- | 0.25(0.27) | 0.03(0.22) | -- | −0.25(0.30) | 0.16(0.19) |

| Mom Dep | -- | 0.17(0.18) | −0.11(0.20) | -- | 0.11(0.27) | −0.03(0.22) | -- | 0.40(0.28) | 0.19(0.21) |

| PBS | -- | 0.41(0.17)* | −0.10(0.21) | -- | 0.04(0.30) | −0.29(0.20) | -- | 0.13(0.38) | −0.14(0.20) |

| Gender | -- | −0.06(0.16) | −0.16(0.18) | -- | 0.35(0.27) | −0.02(0.22) | -- | 0.39(0.31) | 0.21(0.19) |

| Race | -- | 0.33(0.16)* | −0.03(0.19) | -- | 0.14(0.28) | −0.18(0.21) | -- | 0.16(0.32) | −0.76(0.14)** |

| Income | -- | −0.01(0.16) | −0.30(0.20) | -- | −0.26(0.33) | −0.31(0.22) | -- | 0.14(0.34) | −0.13(0.19) |

| Urbanicity | -- | −0.06(0.17) | −0.10(0.18) | -- | −0.49(0.23)* | −0.29(0.20) | -- | 0.70(0.21)** | 0.35(0.19) |

| PC INT | -- | 0.61(0.17)** | −0.04(0.22) | -- | 0.70(0.27)* | 0.33(0.25) | -- | −0.25(0.40) | −0.11(0.23) |

| PC EXT | -- | 0.31(0.19) | 0.90(0.15)** | -- | −0.08(0.28) | 0.54(0.22)* | -- | 0.26(0.35) | 0.24(0.23) |

Notes.

p < 0.001,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.10.

Standardized coefficients and standard errors shown. Mom Dep: Maternal depression. PBS: Positive Behavior Support. CO: Co-occurring. INT: Internalizing only. Ext: Externalizing only. Low: Low Problems. PC: Primary Caregiver. FCU (Family Check-Up): 0=Control, 1=Intervention. Gender: 0=male, 1=female. Race: 1=Caucasian, 0=Other. Urbanicity: 1=rural, 2=suburban, 3=urban. Higher scores refer to higher levels of continuous variables.

Mediation.

In PC and AC models, youth who received FCU were significantly more likely to belong to the low problem or externalizing “only” groups than to the co-occurring group; this effect operated indirectly through maternal depression (ages 2 to 3).

In the PC model only, those who received FCU were significantly more likely to belong to the internalizing “only” than to the co-occurring group, and again this effect operated indirectly through improvements in maternal depression. Also for PCs only, FCU predicted greater likelihood of membership in the internalizing “only” relative to the low problems group, and this operated indirectly through enhanced positive behavior support.

In the teacher model, those who received FCU were significantly more likely to belong to the low problems, externalizing “only,” and internalizing “only” groups than to the co-occurring group, and this effect operated through improvements in positive behavior support.

Post-hoc analyses.

Based on promising initial findings that child age 3 parenting factors mediated long-term intervention effects, we conducted post-hoc analyses to understand the unique effects of parent factors in toddlerhood over and above those in middle childhood, another potentially important period because of the transition to formal schooling. We evaluated post-hoc models that included as mediators maternal depression and positive behavior support at both child ages 3 and 7.5. Identical to primary analyses, age 3 maternal depression uniquely mediated the effect of FCU on co-occurring relative to externalizing ‘only’ problems (PC and AC models) and age 3 positive behavior support uniquely mediated the effect of FCU on co-occurring relative to externalizing ‘only,’ internalizing ‘only,’ and low problems (teacher model). We also found that the mediational chain of FCU-to-age 3 maternal depression-to age 7.5 maternal depression predicted both the co-occurring and externalizing ‘only’ groups relative to the low problems group (PC and teacher models). Similarly, the mediational chain from FCU-to-age 3 positive behavior support-to-age 7.5 positive behavior support predicted the low problems group relative to the externalizing ‘only’ group (significantly for teachers and marginally for PC and AC). There was no longer an effect of maternal depression at any age on the co-occurring relative to internalizing ‘only’ groups in PC or AC models. Refer to Figure 2 and Supplementary Tables 3–4 for full results.

To ensure that results were not an artifact of examining youth outcomes only at age 14, we analyzed a four-class LPA of PC-reported problem behavior at age 10 and determined the cases that exhibited stable co-occurring problems at ages 10 and 14 (n = 15). Compared to those who did not exhibit stable co-occurring problems (n = 597), those who did showed higher maternal depression (β = 0.33, p = 0.001) but did not differ on positive behavior support (β = −0.01, ns; note, this pattern is identical to the primary analyses). Results did not appear to be an artifact of using the age 14 assessment. We did not repeat longitudinal analyses using teachers’ or ACs’ reports because these reporters changed across waves, introducing reporter-specific bias.

Discussion

Although the effectiveness of the FCU has been documented for childhood to adulthood outcomes (e.g., Connell et al., 2008; Connell, McKillop, & Dishion, 2016; Dishion et al., 2014, 2008; Shaw et al., 2009, 2018), this was one of the first studies to evaluate whether initiation of the intervention during early childhood decreased risk for co-occurring internalizing and externalizing problems in adolescence. Moreover, this study extended prior work that established maternal depression and positive behavior support as important mediators of FCU on a range of maladaptive (Dishion et al., 2008; Reuben et al., 2015; Shaw et al., 2009) and prosocial (Brennan et al., 2013) behaviors by testing whether modifying the quality of early parent factors resulted in improvements in co-occurring problem behaviors.

Several findings were particularly robust. In both PC and AC models, the FCU predicted improvements in maternal depression from ages 2-to-3 (as previously reported in Shaw et al., 2009), which in turn decreased the likelihood of being in the co-occurring problems group relative to the low problems, externalizing “only,” and internalizing “only” groups (the latter was marginal for AC). In contrast, in the teacher model, the FCU predicted improvements in positive behavior support from ages 2–3 (as previously reported in Dishion et al., 2008), which in turn decreased the likelihood of being in the co-occurring problems group relative to all other groups.

Reporter-Specific Findings May Reflect Context-Specific Effects

The mediating role of maternal depression in the indirect FCU intervention effect should be interpreted in light of its replication across PC and ACs, but not teachers. Although the association between mothers’ depression and their reports of adolescents’ co-occurring problems (i.e., PCs) could partially reflect depressed mothers’ tendencies to over-report children’s problem behaviors (e.g., Fergusson, Lynskey, & Horwood, 1993), our replication of this effect using AC reports of adolescents’ behavior appreciably mitigates concerns of reporter bias. Thus, our results are more aligned with the explanation that adult reporters observe meaningful differences in youths’ behavior that reflect context-specific problems. Maternal depression could represent a marker for continued familial conflict or poor parent-child relationships (see (Cummings, Cheung, Koss, & Davies, 2014 for a review) that elicits adolescents’ co-occurring problems at home but not in the school setting. Alternatively, the association between maternal depression and youth problem behavior could simply reflect direct genetic effects, wherein mothers’ transmission of genetic risk to offspring causes youths’ problem behavior, or could reflect the reverse direction of effect, with earlier offspring behavior causing maternal depression. Although more research is needed to rule out alternative explanations, results suggest that preventing and treating maternal depression could improve adolescents’ adjustment, particularly in interactions with parents or other family members. Findings also highlight the importance of early intervention; indeed, maternal depression at age 3 was either directly, or indirectly through age 7.5 maternal depression, implicated in risk for co-occurring problems relative to externalizing ‘only’ and low problems, as well as for externalizing ‘only’ relative to low problems. Those with co-occurring relative to internalizing ‘only’ problems were differentiated by the stability in maternal depression, as neither age 3 nor 7.5 maternal depression predicted this contrast after including both simultaneously. This result similarly indicates the need for early prevention, as it could disrupt chronicity in maternal depression and thus prevent co-occurring problems.

Likewise, the mediating role of positive behavior support in the relation between the FCU and teacher-reported co-occurring problems is likely not spurious despite a lack of replication using PCs’ and ACs’ reports. Two relatively objective raters with expertise to assess youths relative to same-aged peers reported on positive behavior support (trained observers) and adolescents’ problem behaviors (teachers); as a result, shared reporter or method bias cannot confound this finding. Moreover, prior research demonstrated that teachers’ reports of adolescents’ functioning showed greater predictive validity than parents’ reports (Verhulst, Koot, & Van der Ende, 1994), reinforcing our confidence in the intervention effects and suggesting that they could have strong reproducibility and clinical implications.

Our results suggest that parents’ positive behavior support at age 3 may uniquely contribute to school-specific co-occurring problems, above and beyond parents’ positive behavior support in middle childhood. Prior studies in this sample showed that positive behavior support was a key mediator in the relation between the FCU and indicators of young children’s school readiness and success, such as inhibitory control, language development, and academic achievement scores (Brennan et al., 2013; Lunkenheimer et al., 2008). In the context of these previous findings, it makes sense that positive behavior support would facilitate improved self-regulation skills as manifest by teacher-observed externalizing and internalizing symptoms. Indeed, the school environment requires adolescents to regulate emotions and behaviors amid complex peer dynamics and academic demands, to follow instructions and rules, and to focus attention. The present results reinforce the importance of enhancing parents’ positive behavior support in early childhood for improved socioemotional functioning at school.

It is less clear why positive behavior support was not a reliable predictor of caregiver-reported problem behaviors. Although we found that positive behavior support was higher in the PC-reported internalizing “only” group relative to the low problem group, this effect may be spurious because it did not replicate with other reporters (i.e., marginal statistical significance, same directionality). Perhaps other parent factors are simply more influential over adolescents’ co-occurring problem behaviors as observed in the home, such as maternal depression, parent-child relationships, and adolescent autonomy support (Kobak, Abbott, Zisk, & Bounoua, 2017).

Effectiveness of the Family Check-Up

Of central importance, our findings suggest that delivering the FCU beginning as early as the “terrible twos” can exert an indirect impact over a serious and debilitating outcome in adolescence—co-occurring internalizing and externalizing problems—by improving one or both critical features of children’s home environments: maternal depression and caregiving quality.

The FCU exerted a modest effect on maternal depression (Cohen’s d = 0.12) and positive behavior support (Cohen’s d = 0.14), consistent with the theoretical premise underlying the FCU that motivational enhancement for improving family functioning will elicit progress in these domains. Intervention effects could also be attributable to the FCU providing support for parents, parent management strategies, and someone in the community parents could count on (i.e., parent consultant). By improving caregiving skills, such as positive behavior support, the FCU may have also led to more pleasurable experiences with the child, thus reducing symptoms of maternal depression. Based on relatively modest effect sizes, although consistent with a prevention sample (i.e., those not actively seeking help), perhaps future iterations of the FCU could be strengthened by more carefully tailoring the intervention to different family constellations and culture-specific subgroups, such as sexual, gender, and ethnic minorities.

Notably, the FCU showed no direct effects on adolescents’ problem behavior. This was also true of post-hoc tests of the effect of the FCU over time (ages 3–10); we found no direct associations between the number of FCU feedback sessions from ages 3–10 and adolescents’ co-occurring problems that replicated across reporters. Thus, only by including parent-level mediators were ITT intervention effects observed for adolescent outcomes. Results underscore the importance of testing mediators of intervention effects because they may uncover more realistic and nuanced effects operating across longer periods of time.

FCU intervention effects are especially important in light of the clinically significant levels of pathology exhibited by youths in the co-occurring internalizing and externalizing group (see Supplementary Figure 1). On average, this group scored above the clinical cutoff of 70 on the majority of the subscales, whereas the average scores for those in the internalizing or externalizing “only” groups never surpassed this threshold, consistent with prior research showing a more clinically-severe co-occurring group (Fanti & Heinrich, 2010). Our findings thus highlight the utility of a family-centered preventive intervention model for families at high-risk.

Unexpected Findings and Discrepancies with Prior Research

In contrast to initial hypotheses and previous studies (e.g., Basten et al., 2013; Fanti & Henrich, 2010), maternal depression and positive behavior support did not differentiate those with low problem behaviors from those with internalizing or externalizing problems “only.” Perhaps the lack of differences owes to the fact that internalizing “only” and externalizing “only” groups showed non- or borderline-clinical levels of pathology on most problem behavior subscales. Our high-risk sample may also have less variability in parenting factors than community-based samples, which could have suppressed differences among these groups.

It is also noteworthy that prior studies investigating the effect of maternal depression and positive behavior support on internalizing and externalizing problems separately did not find similar reporter-specific effects (e.g., Dishion et al., 2008; Lyons-Ruth, Easterbrooks, & Cibelli, 1997). Differences could be because of our focus on co-occurring problems, which have potential to be more discrepant across settings than internalizing or externalizing problems alone (i.e., it is statistically more likely that parents and teachers agree on one problem than on two).

Strengths and limitations

Although the study has several methodological strengths (e.g., experimental, prospective design of a large, at-risk cohort varied in level of urbanicity), a few limitations need to be acknowledged. As depressed mothers can influence perceptions of ACs, maternal depression may have only predicted AC-reported problems because of maternal depression-related reporter bias. We did not obtain ACs’ perceptions of maternal depression, which could have clarified this potential confound. Most of the PCs in this study were mothers (i.e., 97.7%), so this study cannot speak to the influence of fathers’ positive behavior support or depression. We also did not assess associations with adolescent-reported LPAs because models with more than two groups always included at least one very small group that was unsuitable for statistical analysis (i.e., <5% of sample). As power to detect the true number of groups increases with more indicators (Tein, Coxe, & Cham, 2013), this result is likely because of the small number of indicators for adolescent-reported problems (only three). A core component of the FCU was to increase parents’ motivation to change, which could have increased service engagement motivation. However, this issue makes it difficult to disentangle the effects of the FCU versus post-FCU services, especially as no data were collected on the extent to which caregivers perceived their service utilization to be influenced by FCU. Finally, it is not clear that results would generalize to children living in lower-risk, middle-class communities, with better community resources in child care and neighborhood and school quality. These resources may buffer adverse effects of suboptimal home environments on later co-occurring problems, and/or intervention effects of the FCU may be less evident (i.e., more challenging to improve less severe problems).

This study also had significant strengths that increased confidence in the credibility of our findings. We rigorously tested our hypotheses by using three reporters of adolescents’ problem behaviors, which extends prior studies that only examined mothers’ reports of children’s co-occurring psychopathology (Basten et al., 2013; Fanti & Henrich, 2010). We also accounted for baseline levels of all dependent variables so that analyses were prospective. Finally, we derived adolescent problem behavior groups using a data-driven and empirical approach that enabled tests of antecedents to co-occurring problem behaviors.

Future directions

Results highlight several important areas warranting further research. Research is needed to explicitly test our hypotheses about why co-occurring problems observed in different contexts were influenced by unique aspects of the home environment. Testing moderators (i.e., child sex, genetic risk) would also enhance our understanding of for whom the FCU may alleviate co-occurring problems. Finally, evaluating the presence of a stable co-occurring group from childhood to adolescence, and the effect of the FCU and early parent factors on this group, would provide even more robust evidence about the utility of the intervention.

Conclusions

The strong pattern of findings from the current study suggest that a family-based preventive intervention initiated in early childhood indirectly prevents adolescents’ co-occurring internalizing and externalizing problems in both home and school contexts by improving the quality of the early home environment. However, results showed that these effects were attributable to different mechanisms of action, with maternal depression being key for improved functioning at home and parenting more salient for improved functioning at school. As adolescents with co-occurring problem behaviors have been shown to possess particularly high risk for psychopathology and impairment in adulthood, our results also suggest that delivering the FCU to those in need holds promise to reduce the overall burden of mental illness.

Supplementary Material

Public Health Statement:

At-risk youths who received a family-centered prevention starting in toddlerhood were less likely to experience more than one type of mental health problem as adolescents. The reason the prevention helped was because it improved parents’ functioning.

Acknowledgements:

This research was principally supported by grants 023245 and 2003723 from NIDA (Shaw, Dishion, Wilson). Additional support was provided by 007453 from NIAAA (Wang).

References

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2000). Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/1½−5 and 2000 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2001). Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, & Erkanli A (1999). Comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 40(1), 57–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basten MMGJ, Althoff RR, Tiemeier H, Jaddoe VWV, Hofman A, Hudziak JJ, … van der Ende J (2013). The Dysregulation Profile in Young Children: Empirically Defined Classes in the Generation R Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(8), 841–850.e2. 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP, Webster-Stratton C, & Reid MJ (2005). Mediators, Moderators, and Predictors of 1-Year Outcomes Among Children Treated for Early-Onset Conduct Problems: A Latent Growth Curve Analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 371–388. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolck A, Croon M, & Hagenaars J (2004). Estimating Latent Structure Models with Categorical Variables: One-Step Versus Three-Step Estimators. Political Analysis, 12(1), 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF, McAdoo HP, & Garcia Coll C (2001). The Home Environments of Children in the United States Part I: Variations by Age, Ethnicity, and Poverty Status. Child Development, 72(6), 1844–1867. 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan LM, Shelleby EC, Shaw DS, Gardner F, Dishion TJ, & Wilson M (2013). Indirect effects of the family check-up on school-age academic achievement through improvements in parenting in early childhood. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 762–773. 10.1037/a0032096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S, & Muthén BO (2009). Relating latent class analysis results to variables not included in the analysis. Retrieved from https://www.statmodel.com/download/relatinglca.pdf

- Connell A, Bullock BM, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Wilson M, & Gardner F (2008). Family Intervention Effects on Co-occurring Early Childhood Behavioral and Emotional Problems: A Latent Transition Analysis Approach. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(8), 1211–1225. 10.1007/s10802-008-9244-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell AM, McKillop HN, & Dishion TJ (2016). Long-term effects of the Family Check-Up in Early Adolescence on Risk of Suicide in Early Adulthood. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 46(Suppl 1), S15–S22. 10.1111/sltb.12254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Cheung RYM, Koss K, & Davies PT (2014). Parental Depressive Symptoms and Adolescent Adjustment: A Prospective Test of an Explanatory Model for the Role of Marital Conflict. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(7), 1153–1166. 10.1007/s10802-014-9860-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulou S, Verhulst FC, & van der Ende J (2011). The parallel development of ODD and CD symptoms from early childhood to adolescence. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 20(6), 301–309. 10.1007/s00787-011-0175-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ (2000). Cross-setting consistency in early adolescent psychopathology: Deviant friendships and problem behavior sequelae. Journal of Personality, 68(6), 1109–1126. 10.1111/1467-6494.00128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Brennan LM, Shaw DS, McEachern AD, Wilson MN, & Jo B (2014). Prevention of Problem Behavior Through Annual Family Check-Ups in Early Childhood: Intervention Effects From Home to Early Elementary School. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(3), 343–354. 10.1007/s10802-013-9768-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, & Kavanagh K (2003). Intervening in adolescent problem behavior: A family-centered approach. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Connell A, Gardner F, Weaver C, & Wilson M (2008). The Family Check-Up With High-Risk Indigent Families: Preventing Problem Behavior by Increasing Parents’ Positive Behavior Support in Early Childhood. Child Development, 79(5), 1395–1414. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, & Stormshak EA (2007). Intervening in children’s lives: An ecological, family-centered approach to mental health care. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Fagot BI, & Kavanagh K (1993). Parenting during the Second Year: Effects of Children’s Age, Sex, and Attachment Classification. Child Development, 64(1), 258–271. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02908.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanti KA, & Henrich CC (2010). Trajectories of pure and co-occurring internalizing and externalizing problems from age 2 to age 12: Findings from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care. Developmental Psychology, 46(5), 1159–1175. 10.1037/a0020659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, & Horwood LJ (1993). The effect of maternal depression on maternal ratings of child behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 21(3), 245–269. 10.1007/BF00917534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner FEM, Sonuga-Barke EJS, & Sayal K (1999). Parents Anticipating Misbehaviour: An Observational Study of Strategies Parents Use to Prevent Conflict with Behaviour Problem Children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40(8), 1185–1196. 10.1111/1469-7610.00535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, & Heyward D (2011). Maternal Depression and Child Psychopathology: A Meta-Analytic Review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14(1), 1–27. 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabson JM, Dishion TJ, Gardner F, & Burton J (2004). Relationship Process Code v-2.0. training manual: A system for coding relationship interactions. Unpublished coding manual, Child and Family Center, Eugene, OR. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, & Whitley MK (2006). Comorbidity, case complexity, and effects of evidence-based treatment for children referred for disruptive behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(3), 455–467. 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Cohen J, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Pawlby SJ, & Caspi A. (2005). Maternal depression and children’s antisocial behavior: Nature and nurture effects. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(2), 173–181. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak R, Abbott C, Zisk A, & Bounoua N (2017). Adapting to the Changing Needs of Adolescents: Parenting Practices and Challenges to Sensitive Attunement. Current Opinion in Psychology, 15, 137–142. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, & Seeley JR (1995). Adolescent Psychopathology: III. The Clinical Consequences of Comorbidity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 34(4), 510–519. 10.1097/00004583-199504000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunkenheimer ES, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Connell AM, Gardner F, Wilson MN, & Skuban EM (2008). Collateral benefits of the family check-up on early childhood school readiness: Indirect effects of parents’ positive behavior support. Developmental Psychology, 44(6), 1737–1752. 10.1037/a0013858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons-Ruth K, Easterbrooks MA, & Cibelli CD (1997). Infant attachment strategies, infant mental lag, and maternal depressive symptoms: Predictors of internalizing and externalizing problems at age 7. Developmental Psychology, 33(4), 681–692. 10.1037/0012-1649.33.4.681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, & Sheets V (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 83–104. 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, & Muthén LK (2000). Integrating Person-Centered and Variable-Centered Analyses: Growth Mixture Modeling With Latent Trajectory Classes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 24(6), 882–891. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb02070.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998). Mplus User’s Guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, & Muthén BO (2007). Deciding on the Number of Classes in Latent Class Analysis and Growth Mixture Modeling: A Monte Carlo Simulation Study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(4), 535–569. 10.1080/10705510701575396 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reuben JD, Shaw DS, Brennan LM, Dishion TJ, & Wilson MN (2015). A family-based intervention for improving children’s emotional problems through effects on maternal depressive symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(6), 1142–1148. 10.1037/ccp0000049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Bell RQ, & Gilliom M (2000). A truly early starter model of antisocial behavior revisited. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 3(3), 155–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Connell A, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN, & Gardner F (2009). Improvements in maternal depression as a mediator of intervention effects on early childhood problem behavior. Development and Psychopathology, 21(2), 417–439. 10.1017/S0954579409000236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Galán C, Lemery-Chalfant K, Dishion TJ, Gardner FE, & Wilson MN (2018). Early predictors of children’s early-starting conduct problems: Child, family, genetic, and intervention effects. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Shaw DS, & Gross HE (2008). What we have Learned about Early Childhood and the Development of Delinquency In Liberman AM (Ed.), The Long View of Crime: A Synthesis of Longitudinal Research (pp. 79–127). 10.1007/978-0-387-71165-2_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, & Wilson MN (2013). Indirect effects of fidelity to the family check-up on changes in parenting and early childhood problem behaviors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(6), 962–974. 10.1037/a0033950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst FC, Koot HM, & Van der Ende J (1994). Differential predictive value of parents’ and teachers’ reports of children’s problem behaviors: A longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 22(5), 531–546. 10.1007/BF02168936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang FL, Eisenberg N, Valiente C, & Spinrad TL (2015). Role of temperament in early adolescent pure and co-occurring internalizing and externalizing problems using a bifactor model. Development and Psychopathology, 1–18. 10.1017/S0954579415001224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, & Hammond M (1998). Conduct Problems and Level of Social Competence in Head Start Children: Prevalence, Pervasiveness, and Associated Risk Factors. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 1(2), 101–124. 10.1023/A:1021835728803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Dubo ED, Sickel AE, Trikha A, Levin A, & Reynolds V (1998). Axis I Comorbidity of Borderline Personality Disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155(12), 1733–1739. 10.1176/ajp.155.12.1733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, & Slesnick N (2017). The Effects of a Family Systems Intervention on Co-Occurring Internalizing and Externalizing Behaviors of Children with Substance ABUsing Mothers: A Latent Transition Analysis. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 0(0). 10.1111/jmft.12277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.