Abstract

Gastrointestinal (GI) cancers like liver, pancreatic, colorectal, and gastric cancer remain some of the most difficult and aggressive cancers. Nanoparticles like liposomes had been approved in the clinic for cancer therapy dating as far back as 1995. Over the years, liposomal formulations have come a long way, facing several roadblocks and failures, and advancing by optimizing formulations and incorporating novel design approaches to navigate therapeutic delivery challenges. The first liposomal formulation for a GI cancer drug was approved recently in 2015, setting the stage for further clinical developments of liposome-based delivery systems for therapies against GI malignancies. This article reviews the design considerations and strategies that can be used to deliver drugs to GI tumors, the wide range of therapeutic agents that have been explored in preclinical as well as clinical studies, and the current therapies that are being investigated in the clinic against GI malignancies.

Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) cancers are one of the major contributors to cancer-related mortalities worldwide. Colorectal and pancreatic cancers are ranked at third and fourth in the list of top 10 cancers by death rates among both males and females, and cancers of the liver and intrahepatic bile duct rank at fifth and eighth in men and women in the list of estimated deaths, respectively, in the United States (Siegel et al., 2018). Chemotherapy is one of the primary treatment modalities used to treat cancer, along with radiation therapy and surgery. However, drug delivery in diseases localized in the GI tract is challenged by the requirements of low systemic distribution and maximizing therapeutic concentrations along the tract. Further, the GI tract can present an extreme environment for therapeutic delivery with factors like pH, immune response, intestinal permeability, and mucosal barriers posing hurdles (Ensign et al., 2012). Additionally, solid tumors in themselves can impose intricate barriers in the altered tumor microenvironment and aberrant vasculatures (Sriraman et al., 2014). Together, these challenges in drug delivery require therapeutic delivery in high doses, which contributes to systemic toxicity and drug resistance.

Nanoscale platforms like liposomes present significant opportunities in rational and targeted drug deliveries in GI cancers, due to their superior efficiency in encapsulating drugs of variable physicochemical character and excellent biocompatibility, and their capability for surviving in the hostile GI environment after suitable modifications. Further, nanoparticle-encapsulated therapeutic agents have the potential to minimize chemotherapy-mediated toxicity and to improve biodistribution and prevent premature metabolism of the active therapeutic agent (Allen and Cullis, 2013; Min et al., 2015; Sousa et al., 2018).

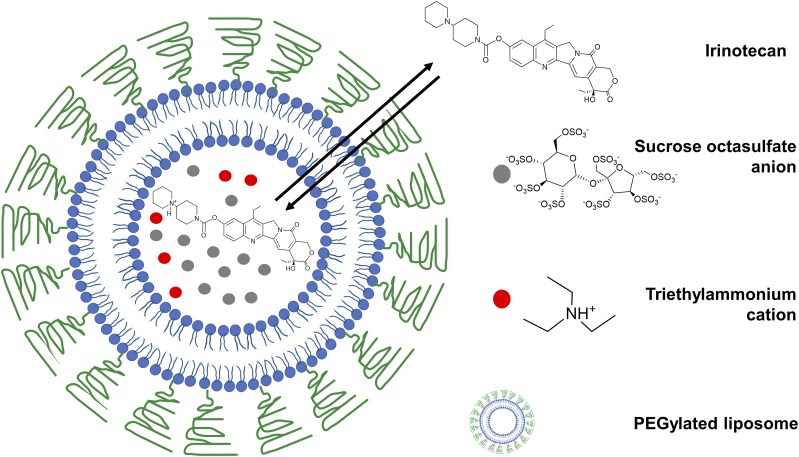

Liposomal structures are spherical vesicles with a lipid layer encapsulating an aqueous core and were described as early as 1965 (Bangham et al., 1965). Since then, liposomes were explored widely as a delivery platform for gene therapies, biologic agents, and chemotherapeutic drugs, leading to the earliest clinical approvals of liposomal drug formulations against cancer with Doxil (1995) and DaunoXome (1996) 3 decades after the discovery of liposomes (Sercombe et al., 2015; Bulbake et al., 2017). Onivyde, a liposomal irinotecan formulation (Fig. 1) was recently approved for use in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer resistant to gemcitabine (Kipps et al., 2017). Currently, liposomal irinotecan is being explored clinically against multiple GI cancer types including colorectal, gastroesophageal, and biliary cancers (Table 1). Herein, we concisely review the liposomal technologies used to deliver therapies against GI cancers and the formulation strategies applied to circumvent the barriers of drug delivery to GI and solid tumors.

Fig. 1.

Onivyde, a clinically approved liposomal formulation in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Multivalent anionic trapping agents are used to retain irinotecan cation inside the liposome.

TABLE 1.

Selected liposomal products in clinical development in GI cancers

| Conditions | Intervention | Phase | Sponsor | Clinical Trials Identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced colorectal cancer | CPX-1 (irinotecan HCl: floxuridine) | II | Jazz Pharmaceuticals (Dublin, Republic of Ireland) | NCT00361842 |

| Gemcitabine-resistant metastatic pancreatic cancer | Liposomal irinotecan (Onivyde) | III (Approved 2015) | Merrimack Pharmaceuticals | NCT01494506 |

| Gastric, gastroesophageal, and esophageal adenocarcinoma | Oxaliplatin in transferrin-conjugated liposome | I/II | Mebiopharm Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan) | NCT00964080 |

| Nonresectable hepatocellular carcinoma | ThermoDox (thermally sensitive liposomal doxorubicin) | III | Celsion (Lawrenceville, NJ) | NCT02112656 |

| Locally advanced/metastatic pancreatic cancer | EndoTAG-1 (paclitaxel in cationic liposomes) | III | SynCore Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Chung Shan Village, Taiwan) | NCT03126435 |

| Pancreatic cancer | (LE-DT) docetaxel | II | INSYS Therapeutics Inc. (Phoenix, AZ) | NCT01186731 |

| Metastatic/unresectable GI cancers | Liposomal irinotecan | I/II | Emory University (Atlanta, GA) | NCT03368963 |

| Liver cancer | Liposomal doxorubicin with TTFields (alternating electric fields) | I | MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX) | NCT03203525 |

| Liver cancer | MTL-CEBPA (CEBPA small activating RNA in liposomes | I | Mina Alpha Ltd. (London, UK) | NCT02716012 |

| Metastatic colorectal cancer | SN-38 liposome | II | Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology (Boston, MA) | NCT00311610 |

| Solid tumors including gastric/gastroesophageal/pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | (MM-310) docetaxel in liposomes targeted with antibodies to EphA2 receptor | I | Merrimack Pharmaceuticals | NCT03076372 |

| Locally advanced/metastatic esophageal carcinoma | PNU-93914 (liposomal paclitaxel) | II | Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (New York, NY) | NCT00016900 |

| Metastatic pancreatic cancer | SGT-53 (human p53 plasmid DNA in cationic liposome) | II | SynerGene Therapeutics, Inc. (Potomac, MD) | NCT02340117 |

| Primary liver cancer | MRX34 (liposomal miRNA-34a mimic) | I | Mirna Therapeutics, Inc. (Austin, TX) | NCT01829971 |

| Metastatic pancreatic cancer | Atu027 (liposomal protein kinase N3 siRNA) | I/II | Silence Therapeutics GmbH (Berlin, Germany) | NCT01808638 |

Design Considerations in Anticancer Therapy

GI cancers offer challenging barriers for drug delivery by combining the hurdles associated with solid tumors, the GI tract physiologic environment, and the tight epithelial tissue barriers if systemic delivery is required (Tscheik et al., 2013). Liposomal compositions need to be tuned to the intended therapeutic challenge and route of administration. However, some general guidelines can be used for designing the nanoplatforms. For in vivo delivery of nanoparticles, several factors must be taken into consideration, like colloidal stability, interaction with proteins in the serum, shelf life, blood circulation time, mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) clearance, tissue extravasation, and cytokine induction (Cheng and Lee, 2016). Advancements in the pharmacokinetic properties of liposomal formulations, and enhancement of cargo encapsulation using active loading principles were two key events in liposomal design that eventually led to the clinical approval of Doxil, PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin, in 1995 (James et al., 1994; Harrison et al., 1995; Northfelt et al., 1997). Steric stabilization of liposomes by incorporation of PEGylated phospholipids significantly increased blood circulation time (Blume and Cevc, 1990; Klibanov et al., 1990), which further enabled passive accumulation in organs with leaky vasculature, by virtue of the “enhanced permeation and retention” (EPR) effect (Matsumura and Maeda, 1986; Torchilin, 2011; Maeda et al., 2016). Further, active loading principles, exploiting the pH gradient between the interior and exterior of the liposome, allowed higher drug encapsulation and minimized nonencapsulated drug loss (Mayer et al., 1986; Bally et al., 1988). Currently, the active loading of liposomes continues to remain a clinically relevant approach for weakly basic drugs and can be exchanged through the liposomal membrane when subjected to a pH gradient. The recently approved Onivyde (2015), a liposomal formulation of irinotecan for patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma who are resistant to gemcitabine, exploits multivalent anionic polymeric/nonpolymeric trapping agents like sucrose octasulfate (Fig. 1) providing an electrochemical gradient to facilitate drug retention in the interior of liposomes (Drummond et al., 2006; Passero et al., 2016; Drummond et al., 2018). In this section, we will review the different strategies that can be exploited to design formulations for drug delivery in GI cancers.

Oral Delivery of Formulations.

Oral delivery is usually a preferred route for gastroenterological conditions; however, with metastatic cancers, the systemic delivery of therapeutic agents is ideal to enhance drug distribution. Moreover, oral delivery using platforms like liposomal nanoparticles may suffer from instability and degradation of the carrier in the GI tract, mediated by gastric acids, lipases secreted from the pancreas, bile salts (Hu et al., 2013a; He et al., 2018), and scalability. Higher drug doses are usually required for oral formulations, requiring scaling up of liposomes, leading to interbatch variability (He et al., 2018). If permeation across intestinal epithelia is desired, it can be a further challenge. Constant renewal of the dynamic GI mucus barrier can restrict intestinal absorption of nanoparticle systems like liposomes (Ensign et al., 2012). Mucoadhesive and mucopenetrating polymers can be used to modify liposomes to enhance intestinal delivery of therapeutic agents (Liu et al., 2018). Alteration in the composition of gut microbiome may also affect drug delivery by impacting intestinal and colonic transit time, mucus production, and immune cell infiltration (Mittal et al., 2018). There had been efforts to exploit cells lining the epithelium, like M cells, to facilitate the transport of liposomal nanoparticles (Shukla et al., 2016). For localized cancers, therapeutic release in a site-specific manner is ideal when surgical resection is not an option. For malignancies of the lower GI tract like cancers of the colon and rectum (Gulbake et al., 2016), factors like temporal control, pH, the enzymatic environment, and pressure can be used to actuate drug release in a specific section of the GI tract as the formulation passes through the gut. So far, there has been limited success in enhancing oral formulations targeting diseased versus normal gut tissue (Hua, 2014); however, active targeting principles can be exploited further to improve uptake in cancerous tissues by decorating nanodelivery systems with ligands that can bind to receptors on the cancer cell surface (He et al., 2018).

Enhanced Permeation and Retention Effect.

Nanoparticle-based platforms can accumulate preferentially in tumors taking advantage of the EPR effect (Matsumura and Maeda, 1986). Previous studies demonstrated increased accumulation of nanoparticle systems within the tumor, compared with normal tissues corresponding to the same organ, in several of the GI malignancies like pancreatic adenocarcinoma, colorectal cancer, and stomach cancer (Natfji et al., 2017). Nanoparticles, because of their size, can preferentially accumulate in tumors, liver, and spleen due to leaky endothelial barriers of these tissues (Li and Huang, 2008). Further, it is possible to tune the size of the nanoparticles to enhance blood circulation time (Liu et al., 1992) and to minimize clearance because of internalization by the cells of the MPS. Surface modification of the liposomal carriers with PEG, commonly referred to as PEGylated liposomes, may reduce opsonization after interaction with components in the blood and subsequent uptake by the MPS (Deshpande et al., 2013). Improving blood circulation time and reduction in opsonization can further increase EPR-mediated uptake as it allows the formulation to circulate through the intended site of drug delivery (Torchilin, 2007). Nanoparticle size plays a critical role in guiding uptake in the solid tumor, and the magnitude of the difference in accumulation between smaller and larger liposomes increases with larger tumors as they tend to be more vascularized (Fanciullino et al., 2014). However, it must be noted that, clinically, there is a high degree of interpatient and intrapatient heterogeneity when it comes to EPR effect in human tumors (Maeda, 2015; Clark et al., 2016). Further, in some human malignancies, vascular permeability is not as high as in preclinical models of cancer, and these factors need to be accounted for while selecting patients for treatment using nanomedicine as a drug delivery system (Jain and Stylianopoulos, 2010; Bae and Park, 2011; Lammers et al., 2012). Using labeled PEGylated liposomes to assess the distribution of formulation in the patient’s lesions by noninvasive imaging is an insightful approach to predict the utility of passive drug targeting while recruiting patients for therapy in the clinic (Harrington et al., 2001).

PEGylated Liposomes: Issues with Anti-PEG Immunity.

Although the PEGylation of liposomes is a commonly used stealth strategy, recent reports (Yang and Lai, 2015; Zhang et al., 2016b) demonstrate that the immune system can induce an antibody response against PEG, resulting in accelerated clearance of PEGylated liposomes and other protein therapeutic agents from the blood. Healthy individuals who are never treated with PEGylated therapeutic agents can have a pre-existing titer of anti-PEG antibodies. A recent report (Chen et al., 2016) showed the presence of either anti-PEG IgG and IgM antibodies in about 44% of patients. Further, pre-existing antibodies against PEG can be a barrier to treat patients with PEG-modified therapeutic agents. A recent phase IIb trial investigating a PEGylated aptamer drug was suspended after three patients were observed to develop a severe allergic reaction against the drug (Povsic et al., 2016). When analyzed retrospectively, these three patients were observed to have elevation in the levels of anti-PEG IgG antibodies, suggesting the association of the pre-existing anti-PEG antibody titer with the potential to induce immune-related adverse events. Currently, alternative stealth polymers like poly(2-oxazoline) are being investigated to shield nanocarriers while bypassing PEG-mediated immune reactions (Bludau et al., 2017).

Active Targeting Approaches.

Nanoparticles can be modified with small molecules, peptides, monoclonal antibodies, or antibody fragments to target tumor cells (Fernandes et al., 2015; Jain and Jain, 2018). A wide variety of ligands had been explored in the past to facilitate the tumor-specific uptake of liposomes. Of these surface engineering approaches, some organs are more accessible to target than others. Liposomes and lipid nanoparticles preferentially accumulate in the liver, which can further be tuned with ligand-receptor interactions to shift biodistribution to specific cell populations in the liver like hepatocytes (Longmuir et al., 2009; Goodwin et al., 2016; Huang, 2017). Galactose N-acetylgalactosamine, heparan sulfate, and transferrin are some of the common ligands that have been used in the past to target nanoparticles to the hepatocytes (Li et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2013b). A whole class of functionalized liposomal platforms, the so-called immunoliposomes, have emerged, exploiting antibody or antibody fragments for targeted delivery (Eloy et al., 2017). Monoclonal antibody and antibody fragments targeting CD44 and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 were explored in preclinical models of hepatocellular carcinoma (Roth et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2012). A vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2–targeted PEGylated formulation of liposomal doxorubicin demonstrated superior efficacy over nontargeted liposomal formulations in murine models of colon cancer (Wicki et al., 2012). Transferrin-conjugated PEG had been used for targeting in preclinical models of gastric cancer as well, demonstrating efficacy over nontargeted liposomes (Iinuma et al., 2002). Cationic liposomal platforms targeted with single-chain antibody fragments against the transferrin receptor (Camp et al., 2013) had also been explored in the delivery of wild-type p53, a tumor-suppressor gene, whose mutation can drive oncogenesis in multiple cancers, including cancers of the pancreas (Freed-Pastor and Prives, 2012). Peptides are also exploited to enhance the distribution to tumor cells. Integrin targeting was achieved with tripeptide motifs, enabling specific binding to colon (Schiffelers et al., 2003) and gastric tumors (Akita et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2008), and pentapeptide motifs were used to drive the accumulation of liposomes in angiogenic sites within murine colon tumors (Shimizu et al., 2005). Further, multiple studies exploited immunoliposomes to mitigate the toxicity of chemotherapeutic drugs and improve efficacy in GI malignancies. Antigen-binding sites of antibodies referred to as F(ab′)2 fragments were explored for targeting liposomes encapsulating doxorubicin in patients with metastatic or recurring cancers of the stomach (Hosokawa et al., 2004; Matsumura et al., 2004). Liposomes targeting human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 had also been used recently to treat human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–overexpressing gastric cancers (Espelin et al., 2016). Another ErbB receptor family member, epidermal growth factor receptor–targeted oxaliplatin liposomes were also explored in murine colorectal cancer models (Zalba et al., 2015).

Although ligand-decorated nanoparticles were demonstrated to facilitate internalization in targeted cells in numerous preclinical applications, they do not improve biodistribution to tumor tissues, because nanoparticles are distributed predominantly by EPR-guided passive targeting. Hence, nanoparticles having similar blood circulation were observed to have a similar distribution, regardless of active targeting (Goren et al., 1996; Kirpotin et al., 2006; Riviere et al., 2011; Allen and Cullis, 2013). Therefore, recent studies have been focused on understanding binding site barriers (BSBs) to improve the cellular disposition of nanomedicine inside solid tumors (Miao et al., 2016).

The BSB can present itself in many forms. The extracellular matrix and the stromal cells near blood vessels can restrict the diffusion of nanoparticles and further actuate internalization in stromal cells driven by targeting receptor expression. Although these barriers are obstacles to drug delivery, the so-called off-target delivery to fibroblasts can potentially be exploited in anticancer therapy by targeting fibroblasts for therapeutic delivery, inducing the secretion of cytotoxic mediators in the tumor-stroma environment (Miao et al., 2017b). Further, the insights gained from BSB models invite detailed analyses of tumor cell populations to determine receptor expression in distinct cell populations if specific delivery to cancerous cells in the tumor is critical for therapeutic efficacy.

Stimuli-Sensitive Designs.

Physiologic triggers like pH, light, enzymes, and redox can be exploited for stimuli-responsive drug delivery by driving structural changes within the liposomal delivery platform, allowing the release of therapeutic cargo in the intended biologic environment (Heidarli et al., 2017; Lee and Thompson, 2017). pH-responsive polymers had been exploited in the past to design liposomes capable of releasing the encapsulated cargo in mildly acidic conditions, like the environment around cancer cells. Copolymer-modified rapamycin liposomes had been investigated as a pH-sensitive delivery platform for colon cancer cells in vitro (Ghanbarzadeh et al., 2014). Multifunctional nanoparticles targeting tumor cells, and using pH sensitivity to release cargo in cancer cells had been designed as well (Garg and Kokkoli, 2011). Overexpression of matrix metalloprotease-9 in the tumor extracellular matrix had been exploited to release encapsulated cargo in the tumor microenvironment driven by matrix metalloprotease-9–mediated lipopeptide cleavage (Kulkarni et al., 2014). Liposomes can be coloaded with superparamagnetic magnetite and a chemotherapeutic agent, and the drug release can be triggered by hyperthermia induced by electromagnetic field (Clares et al., 2013). Thermosensitive liposomes capable of releasing drug cargo triggered by mild hyperthermia were also explored in pancreatic cancer cell lines (Affram et al., 2015). Some of these stimuli-responsive liposomes had also been tested in the clinic against GI cancers. Recently, the results from a phase III trial investigating radiofrequency ablation (RFA) in combination with heat-sensitive liposomes encapsulating doxorubicin, in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, were reported (Tak et al., 2018). The study by Tak et al. (2018) did not demonstrate a significant difference in progression-free survival between patients treated with RFA or RFA in combination with thermosensitive doxorubicin liposomes. However, a benefit in patients with solitary lesions was observed. Overall, there are many challenges associated with translating complex nanocarriers to the clinic and with concerns about the cost versus the benefit of targeted nanodelivery systems (Cheng et al., 2012), and these factors need to be taken into consideration for successful clinical translation of multifunctional nanoparticle systems like stimuli-responsive liposomes.

Combination Therapy by Liposome-Assisted Codelivery.

Liposomal drug delivery technologies can be exploited to load combination therapeutics in controlled proportions, further tuning the release of drugs from the delivery vehicle, allowing translations of in vitro combination chemotherapeutic synergies to in vivo therapies (Allen and Cullis, 2013; Zununi Vahed et al., 2017). However, coencapsulation of drugs with different physicochemical properties, like solubility and stability, is challenging. Precise control over the loading ratio of drug combinations, which is required for synergistic anticancer therapy, can be difficult to achieve. Nevertheless, distinct classes of drugs like irinotecan with floxuridine, cytarabine with daunorubicin, cisplatin with daunorubicin, and doxorubicin with salinomycin had been coloaded into liposomes and investigated in murine models of pancreatic and colorectal cancers (Mayer et al., 2006; Sriraman et al., 2015; Gong et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016). Liposomes can also be used to combine different types of payloads, beyond chemotherapeutic agents. Recent studies exploited multipronged delivery vehicle design approaches, like pH-sensitive cationic liposomes, to load a tyrosine kinase inhibitor drug with short interfering RNAs (siRNA) (Yao et al., 2015) and galactose-targeted liposomes to encapsulate doxorubicin and siRNAs against murine models of liver cancer (Oh et al., 2016). Other nucleic acid therapeutic agents like microRNA (miRNA) can be similarly coloaded in liposomes with chemotherapeutic agents like doxorubicin (Fan et al., 2017). Further, it is possible to design complex systems of hybrid liposomes, encapsulating a drug conjugated to metal nanoparticles, and free drug, allowing an initial rapid release of cargo, and subsequent maintenance of drug level at the target tissue site for prolonged intervals (Zhang et al., 2016a). Another recent study (Wei et al., 2017) exploits thermosensitive liposomes to encapsulate a drug targeting pancreatic stellate cells and human serum albumin nanoparticles of paclitaxel against in vivo models of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Liposomes are also routinely used in theranostic applications, like coloading gadolinium and kinase inhibitors, for magnetic resonance imaging–guided treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (Xiao et al., 2016). Biologics like monoclonal antibodies can also be coloaded with photosensitizers to enhance tumor killing mediated by photodynamic therapy and had been investigated in pancreatic cancer models (Tangutoori et al., 2016). There is at least one combination chemotherapeutic liposomal formulation that had been tested in the clinic against GI malignancies called CPX-1, an equimolar combination of irinotecan HCl with floxuridine in a phase II trial (NCT00361842) of colorectal cancer. However, the status of the drug combination in clinical development is unknown.

Payloads and Applications in GI Cancer Therapy

As we had discussed in the previous segments, liposomes are suited to encapsulate a wide range of therapeutic agents, varying in their physicochemical characteristics and mechanisms of action. Liposomes had been widely investigated in different GI cancers preclinically (Zhang et al., 2013a) and clinically (Table 1) (Cascinu et al., 2011; Wang-Gillam et al., 2016; Tak et al., 2018). In this section, we briefly highlight the different therapeutic agents that had been encapsulated using liposomal drug delivery systems for GI malignancies.

Small Molecules.

Several liposomal formulations of small molecule–based therapeutic agents had been investigated in GI cancers over the years. Targeted and nontargeted liposomal doxorubicin formulations were explored in numerous studies involving preclinical models of colorectal cancer alone (Chang et al., 2010; Falciani et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2012; Wicki et al., 2012). Other chemotherapeutic agents and small-molecule drugs like antiangiogenic, antifibrotic, and anti-inflammatory agents; photosensitizers; and kinase-targeted therapeutic agents were also routinely investigated (Kan et al., 2011; Mullauer et al., 2011; He et al., 2013; Ranjan et al., 2013; Di Corato et al., 2015; Sriraman et al., 2015). Chemotherapeutic drugs can be modified before encapsulation in liposomal formulations to mitigate cytotoxicity in free tissues and to take advantage of tumor microenvironment–specific factors. PEGylated formulation of a mitomycin C prodrug was explored in multiple GI tumor models including colon, gastric, and colon cancer, exploiting drug release mediated by reductive factors in tumor tissues (Gabizon et al., 2006, 2012). Alternately, active metabolites of drugs were also formulated to overcome drug resistance mediated by mutational changes within the tumor cells. Gemcitabine triphosphate, a pharmacologically active nucleotide analog and a metabolite of gemcitabine (Zhang et al., 2013b), was formulated in lipid calcium phosphate (LCP) nanoparticles, a nanoformulation with an asymmetric lipid bilayer (Li et al., 2012), and was reported to be efficacious in pancreatic cancer. Tumor-specific factors can further be harnessed to tailor the delivery of small molecules using liposomal formulations in the clinic. Merrimack Pharmaceuticals (Cambridge, MA), who developed Onivyde earlier, is currently investigating (NCT03076372) an ephrin receptor A2 (EphA2) antibody-directed liposomal docetaxel in solid tumors, including gastric and pancreatic cancer. The immunohistochemistry of clinical tumor samples was used to develop a framework for screening patients for inclusion in the clinical trial based on EphA2 expression in the patient’s tumor (Kamoun et al., 2016). Overall, these approaches suggest that liposomes have many advantages in mitigating the cytotoxicity of chemotherapeutics and other small molecules, and in augmenting therapeutic benefit by improving drug delivery and release in the tumor. Taking lessons from the early clinical trials, a new generation of liposomal formulations is moving into clinical trials, bringing hope for several GI malignancies with limited therapeutic options.

Gene Delivery.

Exogenous nucleic acids like DNA, mRNA, siRNA, short hairpin RNA, miRNA, antisense oligonucleotides, and aptamers have been widely investigated preclinically and clinically for therapy in cancer and other genetic diseases (Ozpolat et al., 2014; Yin et al., 2014; Ramamoorth and Narvekar, 2015; Xiang et al., 2017). Several oligonucleotide therapeutic agents have received regulatory approval over the years (Stein and Castanotto, 2017), including the recent RNA interference drug patisiran, an siRNA formulated in lipid nanoparticles, after a successful phase III clinical trial in patients suffering from hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (Adams et al., 2018). There are a few studies that have explored liposomes for the delivery of viral vectors in GI cancers (Liu et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011). The primary objective in those studies was to explore whether liposomes can be exploited to protect adenovirus from neutralizing antibodies. There had been, however, extensive efforts investigating liposomes and other lipid-based products for nonviral gene therapy (Guo and Huang, 2012). The reports of early-phase clinical trials for nucleic acids using liposomes in cancer date as far back as 2004. An antisense oligonucleotide complementary to c-raf-1 proto-oncogene was investigated in 22 patients with advanced solid tumors, and colorectal cancer was the most common cancer type in the patients (Rudin et al., 2004). Although hypersensitivity reactions associated with liposomal formulations hindered the therapeutic administration, this paved the way for preclinical optimization of formulations in subsequent years.

Nucleic acids, in general, are susceptible to degradation by nucleases. Complexation with cationic/ionizable lipids can prevent the degradation of nucleic acids. Further, nucleic acids are required to be delivered into a specific subcellular compartment to achieve its therapeutic function. Liposomes possess the capability to protect nucleic acids along its physiologic journey and mediate cargo release in a specific compartment inside the cells, facilitating cytosolic trafficking and nuclear transport if required (Guo and Huang, 2011; Hu et al., 2013b; Saffari et al., 2016). To mitigate the toxicity of the cationic liposomes without compromising efficacy, extensive efforts were made to design ionizable lipid-based liposomes. The lipid head groups remain unprotonated during circulation; however, they undergo protonation in the acidic pH of the early or late endosome, facilitating interaction with anionic endosomal membrane lipids and promoting cargo release into the cytosol (Kanasty et al., 2013).

A broad range of nucleic acid cargos had been delivered using liposomal formulations in GI cancers (Ozpolat et al., 2014; Harrison et al., 2018). Liposomal formulations of plasmid DNA had been explored in multiple studies with intraperitoneal colon cancers (Kline et al., 2009; Lan et al., 2010; Aoyama et al., 2017). To further increase the stability of the plasmid cargo and achieve improved control over drug release, several polymers like polyethylenimine, poly-l-lysine, and other cationic polymers and polycations had been used to complex with anionic DNA and encapsulate in liposomal nanoparticles (Goodwin and Huang, 2014). Recently, plasmid DNA–based therapeutic agents were explored for nonviral gene therapy and immunotherapy in several GI malignancies including cancers of the colon, pancreas, and liver (Goodwin et al., 2016; Miao et al., 2017a; Shen et al., 2018; Song et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2018). Plasmid therapy using liposomal formulations had also been explored in patients with advanced solid tumors in a phase I trial, including cancers of the colon and rectum (Senzer et al., 2013). The study demonstrated p53 gene expression in tumors, and the toxicities observed were low grade, leading to a phase II clinical trial in patients with metastatic cancer of the pancreas, which is engaged in ongoing recruiting as of October 2018 (NCT02340117).

Liposomal nanoformulations were also investigated extensively for RNA interference therapies in GI malignancies and other solid tumors (Zhang et al., 2013a; Xin et al., 2017). Atu027, an siRNA against Protein Kinase 3 was encapsulated in liposomes and had been explored in a phase Ib/IIa trial against metastatic pancreatic cancer as a combination therapy with gemcitabine (Aleku et al., 2008; Schultheis et al., 2016). The therapy demonstrated a dose-dependent benefit, and therapy was well tolerated, although grade 3 toxicities were recorded in most patients. Other emerging nucleic acid–based therapeutic agents like miRNA (Shah et al., 2016) had also been explored in the clinic in GI malignan cies like liver cancer using liposomal formulations (NCT01829971). Although the expression of target genes was repressed based on patient tumor analyses, the trial had to be suspended because five patients suffered from immune-related adverse events (Peltier et al., 2016; Beg et al., 2017). It is unclear whether the adverse events were mediated by liposomal formulation, alterations in gene expression driven by the miRNA therapeutic agent, or inflammation actuated by double-stranded RNA (Dempsey and Bowie, 2015). However, future translational efforts of nucleic acid–based therapeutic agents need to consider these factors to warrant strong antitumor activity while mitigating toxicity associated with the therapeutic agent or its carrier.

Harnessing Liposomal Drug Delivery to Treat Liver Metastases.

The liver is a common site of metastasis for a wide variety of primary GI tumors, including colorectal and pancreatic adenocarcinoma (de Ridder et al., 2016). Metastatic dissemination significantly impacts mortality in cancer, accounting for about 90% of cancer-related deaths (Chaffer and Weinberg, 2011). In colorectal cancer patients, 5-year overall survival differs significantly between patients with liver metastases (16.9%) and without liver metastases (70.4%) (Engstrand et al., 2018). Liposomes are well suited for hepatic delivery because of enhanced distribution in the liver, which is further tunable with active targeting. As we discussed previously, several ligands had been used in the past to direct therapeutic agents to hepatocytes.

Recently, LCP nanoparticles with an asymmetric lipid bilayer were shown to be efficacious in delivering plasmids expressing protein traps in murine liver metastasis models of colorectal and breast cancer (Goodwin et al., 2016, 2017). LCP nanoparticles delivering phosphorylated adjuvants and peptides also demonstrated efficacy in arresting colorectal cancer metastasis (Goodwin and Huang, 2017). As discussed earlier, a liposomal formulation of miRNA had also been explored in patients with primary cancers of the liver or liver metastases (Beg et al., 2017). Stimuli triggers were also used preclinically for the treatment of liver metastases. Iron oxide and oxaliplatin were loaded in PEGylated liposomes, and drug release was triggered by an alternating magnetic field (Gogineni et al., 2018). In a recently reported phase III trial (Tak et al., 2018), results from a thermosensitive liposomal doxorubicin in combination with RFA in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma, the treatment of patients with multiple lesions was found to be challenging as repositioning the probe for ablation resulted in the loss of local tissue concentration of doxorubicin. Overall, there remain significant challenges associated with drug delivery targeting metastatic tumor sites like the liver warranting increased attention in clinical drug development targeted to metastases over the primary tumor (Ganapathy et al., 2015).

Liposomal Vaccines.

Liposomes are well suited as vaccine delivery systems in cancer, and beyond. Cationic liposomes and liposomal formulations can augment the immune response to an antigen by stimulation of an innate immune response (Alving et al., 2016). As carrier systems, liposomes can facilitate the antigen uptake, trafficking, processing, and presentation by enhancing lymphatic tissue drainage and tuning the release of antigen and adjuvant cargo from the delivery system (Watson et al., 2012; Schwendener, 2014). Several types of macromolecules like DNA, mRNA, peptides, and proteins as antigens can be loaded in liposomes acting as cancer vaccines (Banchereau and Palucka, 2018). Two distinct classes of antigens can be explored as candidates for cancer vaccines, nonmutated tumor antigens, which are overexpressed in cancer tissues with otherwise restricted expression pattern, and neoantigens, which are created by alterations in DNA resulting in the formation of new protein sequences absent from a normal host genome (Schumacher and Schreiber, 2015). Liposomes allow coencapsulation of different classes of adjuvants with antigens in a cancer vaccine, allowing delivery and therapeutic efficacy in highly aggressive and metastatic GI tumor models (Goodwin and Huang, 2017). In the past, liposomal formulations of adjuvants like monophosphoryl lipid A were encapsulated with protein tumor antigens and the vaccine formulations were explored in human patients with colorectal cancer (Neidhart et al., 2004). Further, active targeting principles have been used to target liposomes to immune cell populations like dendritic cells in vivo (Xu et al., 2014; Goodwin et al., 2017), and to bypass the challenges and hurdles of ex vivo antigen priming using donor dendritic cells (Cintolo et al., 2012). Because personalized cancer vaccines are slowly coming of age with peptides and RNA as antigens (Ott et al., 2017; Sahin et al., 2017), we are optimistic about the prospect of liposomal formulations in the development of cancer vaccines in GI malignancies.

Summary and Perspectives

Liposomes have come a long way from conceptualization to drug carriers in the clinic, as delivery systems in a wide range of marketed pharmaceutical products. The journey was not a smooth ride, and there were a lot of failures and bumps along the clinical development pathway. Lessons from early clinical trials facilitated optimizations of formulations to mitigate toxicities and adverse events. Liposomal formulations are still relevant in cancer drug development, and we witnessed the first clinically approved liposomal drug formulation for a GI malignancy recently in 2015, using a similar remote loading principle that was exploited to develop Doxil about 20 years ago. Liposomes and other lipid-based nanoparticles have also established their positions as carriers for nucleic acids. Because drug delivery to extrahepatic targets is improved, we can hope to see more gene therapy interventions against GI cancers in the clinic. There are a few therapeutic agents with liposomal formulations that have been actively explored against GI malignancies in human patients. One of these studies (Camp et al., 2013; Senzer et al., 2013) is targeted to restore normal p53 tumor repressor gene function, a protein that is mutated in most patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, and is currently being explored in a phase II clinical trial (NCT02340117). Further, nanomedicine drug development is slowly coming of age, as more considerations are applied to recruiting patients. Approaches like analyses of the patient tumor with proportions of cells expressing the protein used for active targeting of liposomes are used to determine whether a specific patient is suitable for treatment with the targeted liposomal drug formulation. This patient selection strategy can also be expanded to take advantage of passive targeting in the right subset of patients. Considering the heterogeneity of EPR, a “one size fits all” approach may not be suitable, and noninvasive imaging should be exploited to determine whether the patient’s tumor is leaky and to be passively targeted by liposomal formulations. In upcoming years, we can expect to see more rationally designed therapeutic agents bypassing the challenges of safety, efficacy, and regulatory hurdles, and making it into the clinic to tackle some of the more challenging GI malignancies, and achieving specific therapeutic objectives.

Abbreviations

- BSB

binding site barrier

- EphA2

ephrin receptor A2

- EPR

enhanced permeation and retention

- GI

gastrointestinal

- LCP

lipid calcium phosphate

- miRNA

microRNA

- MPS

mononuclear phagocyte system

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- RFA

radiofrequency ablation

- siRNA

short interfering RNA

Authorship Contributions

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Das and Huang.

Footnotes

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grant CA198999]. L.H. is a cofounder of OncoTrap, Inc. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article are reported.

References

- Adams D, Gonzalez-Duarte A, O’Riordan WD, Yang CC, Ueda M, Kristen AV, Tournev I, Schmidt HH, Coelho T, Berk JL, et al. (2018) Patisiran, an RNAi therapeutic, for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. N Engl J Med 379:11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Affram K, Udofot O, Agyare E. (2015) Cytotoxicity of gemcitabine-loaded thermosensitive liposomes in pancreatic cancer cell lines. Integr Cancer Sci Ther 2:133–142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akita N, Maruta F, Seymour LW, Kerr DJ, Parker AL, Asai T, Oku N, Nakayama J, Miyagawa S. (2006) Identification of oligopeptides binding to peritoneal tumors of gastric cancer. Cancer Sci 97:1075–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleku M, Schulz P, Keil O, Santel A, Schaeper U, Dieckhoff B, Janke O, Endruschat J, Durieux B, Röder N, et al. (2008) Atu027, a liposomal small interfering RNA formulation targeting protein kinase N3, inhibits cancer progression. Cancer Res 68:9788–9798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen TM, Cullis PR. (2013) Liposomal drug delivery systems: from concept to clinical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 65:36–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alving CR, Beck Z, Matyas GR, Rao M. (2016) Liposomal adjuvants for human vaccines. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 13:807–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyama K, Kuroda S, Morihiro T, Kanaya N, Kubota T, Kakiuchi Y, Kikuchi S, Nishizaki M, Kagawa S, Tazawa H, et al. (2017) Liposome-encapsulated plasmid DNA of telomerase-specific oncolytic adenovirus with stealth effect on the immune system. Sci Rep 7:14177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae YH, Park K. (2011) Targeted drug delivery to tumors: myths, reality and possibility. J Control Release 153:198–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bally MB, Mayer LD, Loughrey H, Redelmeier T, Madden TD, Wong K, Harrigan PR, Hope MJ, Cullis PR. (1988) Dopamine accumulation in large unilamellar vesicle systems induced by transmembrane ion gradients. Chem Phys Lipids 47:97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banchereau J, Palucka K. (2018) Immunotherapy: cancer vaccines on the move. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 15:9–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangham AD, Standish MM, Watkins JC. (1965) Diffusion of univalent ions across the lamellae of swollen phospholipids. J Mol Biol 13:238–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beg MS, Brenner AJ, Sachdev J, Borad M, Kang YK, Stoudemire J, Smith S, Bader AG, Kim S, Hong DS. (2017) Phase I study of MRX34, a liposomal miR-34a mimic, administered twice weekly in patients with advanced solid tumors. Invest New Drugs 35:180–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bludau H, Czapar AE, Pitek AS, Shukla S, Jordan R, Steinmetz NF. (2017) POxylation as an alternative stealth coating for biomedical applications. Eur Polym J 88:679–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blume G, Cevc G. (1990) Liposomes for the sustained drug release in vivo. Biochim Biophys Acta 1029:91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulbake U, Doppalapudi S, Kommineni N, Khan W. (2017) Liposomal formulations in clinical use: an updated review. Pharmaceutics 9:E12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp ER, Wang C, Little EC, Watson PM, Pirollo KF, Rait A, Cole DJ, Chang EH, Watson DK. (2013) Transferrin receptor targeting nanomedicine delivering wild-type p53 gene sensitizes pancreatic cancer to gemcitabine therapy. Cancer Gene Ther 20:222–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascinu S, Galizia E, Labianca R, Ferraù F, Pucci F, Silva RR, Luppi G, Beretta GD, Berardi R, Scartozzi M. (2011) Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin versus mitomycin-C, 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin for advanced gastric cancer: a randomized phase II trial. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 68:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffer CL, Weinberg RA. (2011) A perspective on cancer cell metastasis. Science 331:1559–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YJ, Chang CH, Yu CY, Chang TJ, Chen LC, Chen MH, Lee TW, Ting G. (2010) Therapeutic efficacy and microSPECT/CT imaging of 188Re-DXR-liposome in a C26 murine colon carcinoma solid tumor model. Nucl Med Biol 37:95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BM, Su YC, Chang CJ, Burnouf PA, Chuang KH, Chen CH, Cheng TL, Chen YT, Wu JY, Roffler SR. (2016) Measurement of pre-existing IgG and IgM antibodies against polyethylene glycol in healthy individuals. Anal Chem 88:10661–10666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Liu DZ, Fang HW, Liang HJ, Yang TS, Lin SY. (2008) Evaluation of multi-target and single-target liposomal drugs for the treatment of gastric cancer. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 72:1586–1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X, Lee RJ. (2016) The role of helper lipids in lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) designed for oligonucleotide delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 99(Pt A):129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z, Al Zaki A, Hui JZ, Muzykantov VR, Tsourkas A. (2012) Multifunctional nanoparticles: cost versus benefit of adding targeting and imaging capabilities. Science 338:903–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cintolo JA, Datta J, Mathew SJ, Czerniecki BJ. (2012) Dendritic cell-based vaccines: barriers and opportunities. Future Oncol 8:1273–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clares B, Biedma-Ortiz RA, Sáez-Fernández E, Prados JC, Melguizo C, Cabeza L, Ortiz R, Arias JL. (2013) Nano-engineering of 5-fluorouracil-loaded magnetoliposomes for combined hyperthermia and chemotherapy against colon cancer. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 85:329–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AJ, Wiley DT, Zuckerman JE, Webster P, Chao J, Lin J, Yen Y, Davis ME. (2016) CRLX101 nanoparticles localize in human tumors and not in adjacent, nonneoplastic tissue after intravenous dosing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113:3850–3854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey A, Bowie AG. (2015) Innate immune recognition of DNA: a recent history. Virology 479–480:146–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ridder J, de Wilt JH, Simmer F, Overbeek L, Lemmens V, Nagtegaal I. (2016) Incidence and origin of histologically confirmed liver metastases: an explorative case-study of 23,154 patients. Oncotarget 7:55368–55376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande PP, Biswas S, Torchilin VP. (2013) Current trends in the use of liposomes for tumor targeting. Nanomedicine (Lond) 8:1509–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Corato R, Béalle G, Kolosnjaj-Tabi J, Espinosa A, Clément O, Silva AK, Ménager C, Wilhelm C. (2015) Combining magnetic hyperthermia and photodynamic therapy for tumor ablation with photoresponsive magnetic liposomes. ACS Nano 9:2904–2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond DC, Kirpotin DB, Hayes ME, Noble C, Kesper K, Awad AM, Moore DJ, and O’brien AJ (2018) inventors, Ipsen Biopharm Ltd, assignee. Liposomal irinotecan preparations. U.S. patent 15,464,922; 2018 July 10. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond DC, Noble CO, Guo Z, Hong K, Park JW, Kirpotin DB. (2006) Development of a highly active nanoliposomal irinotecan using a novel intraliposomal stabilization strategy. Cancer Res 66:3271–3277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eloy JO, Petrilli R, Trevizan LNF, Chorilli M. (2017) Immunoliposomes: a review on functionalization strategies and targets for drug delivery. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 159:454–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engstrand J, Nilsson H, Strömberg C, Jonas E, Freedman J. (2018) Colorectal cancer liver metastases - a population-based study on incidence, management and survival. BMC Cancer 18:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensign LM, Cone R, Hanes J. (2012) Oral drug delivery with polymeric nanoparticles: the gastrointestinal mucus barriers. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 64:557–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espelin CW, Leonard SC, Geretti E, Wickham TJ, Hendriks BS. (2016) Dual HER2 targeting with trastuzumab and liposomal-encapsulated doxorubicin (MM-302) demonstrates synergistic antitumor activity in breast and gastric cancer. Cancer Res 76:1517–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falciani C, Accardo A, Brunetti J, Tesauro D, Lelli B, Pini A, Bracci L, Morelli G. (2011) Target-selective drug delivery through liposomes labeled with oligobranched neurotensin peptides. ChemMedChem 6:678–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan YP, Liao JZ, Lu YQ, Tian DA, Ye F, Zhao PX, Xiang GY, Tang WX, He XX. (2017) MiR-375 and doxorubicin co-delivered by liposomes for combination therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 7:181–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanciullino R, Mollard S, Correard F, Giacometti S, Serdjebi C, Iliadis A, Ciccolini J. (2014) Biodistribution, tumor uptake and efficacy of 5-FU-loaded liposomes: why size matters. Pharm Res 31:2677–2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes E, Ferreira JA, Andreia P, Luis L, Barroso S, Sarmento B, Santos LL. (2015) New trends in guided nanotherapies for digestive cancers: a systematic review. J Control Release 209:288–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freed-Pastor WA, Prives C. (2012) Mutant p53: one name, many proteins. Genes Dev 26:1268–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabizon A, Amitay Y, Tzemach D, Gorin J, Shmeeda H, Zalipsky S. (2012) Therapeutic efficacy of a lipid-based prodrug of mitomycin C in pegylated liposomes: studies with human gastro-entero-pancreatic ectopic tumor models. J Control Release 160:245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabizon AA, Tzemach D, Horowitz AT, Shmeeda H, Yeh J, Zalipsky S. (2006) Reduced toxicity and superior therapeutic activity of a mitomycin C lipid-based prodrug incorporated in pegylated liposomes. Clin Cancer Res 12:1913–1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganapathy V, Moghe PV, Roth CM. (2015) Targeting tumor metastases: drug delivery mechanisms and technologies. J Control Release 219:215–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg A, Kokkoli E. (2011) pH-Sensitive PEGylated liposomes functionalized with a fibronectin-mimetic peptide show enhanced intracellular delivery to colon cancer cell. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 12:1135–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanbarzadeh S, Arami S, Pourmoazzen Z, Khorrami A. (2014) Improvement of the antiproliferative effect of rapamycin on tumor cell lines by poly (monomethylitaconate)-based pH-sensitive, plasma stable liposomes. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 115:323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogineni VR, Park WR, Jagtap J, Parchur A, Sharma G, Joshi A, Kim D-H, Larson AC, White SB. (2018) Abstract 4105: localized and triggered release of oxaliplatin for the treatment of colorectal liver metastasis. Cancer Res 78:4105–4105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Z, Chen D, Xie F, Liu J, Zhang H, Zou H, Yu Y, Chen Y, Sun Z, Wang X, et al. (2016) Codelivery of salinomycin and doxorubicin using nanoliposomes for targeting both liver cancer cells and cancer stem cells. Nanomedicine (Lond) 11:2565–2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin T, Huang L. (2014) Nonviral vectors: we have come a long way. Adv Genet 88:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin TJ, Huang L. (2017) Investigation of phosphorylated adjuvants co-encapsulated with a model cancer peptide antigen for the treatment of colorectal cancer and liver metastasis. Vaccine 35:2550–2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin TJ, Shen L, Hu M, Li J, Feng R, Dorosheva O, Liu R, Huang L. (2017) Liver specific gene immunotherapies resolve immune suppressive ectopic lymphoid structures of liver metastases and prolong survival. Biomaterials 141:260–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin TJ, Zhou Y, Musetti SN, Liu R, Huang L. (2016) Local and transient gene expression primes the liver to resist cancer metastasis. Sci Transl Med 8:364ra153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goren D, Horowitz AT, Zalipsky S, Woodle MC, Yarden Y, Gabizon A. (1996) Targeting of stealth liposomes to erbB-2 (Her/2) receptor: in vitro and in vivo studies. Br J Cancer 74:1749–1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulbake A, Jain A, Jain A, Jain A, Jain SK. (2016) Insight to drug delivery aspects for colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 22:582–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Huang L. (2011) Nanoparticles escaping RES and endosome: challenges for siRNA delivery for cancer therapy. J Nanomater 2011:12. [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Huang L. (2012) Recent advances in nonviral vectors for gene delivery. Acc Chem Res 45:971–979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington KJ, Mohammadtaghi S, Uster PS, Glass D, Peters AM, Vile RG, Stewart JS. (2001) Effective targeting of solid tumors in patients with locally advanced cancers by radiolabeled pegylated liposomes. Clin Cancer Res 7:243–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison EB, Azam SH, Pecot CV. (2018) Targeting accessories to the crime: nanoparticle nucleic acid delivery to the tumor microenvironment. Front Pharmacol 9:307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison M, Tomlinson D, Stewart S. (1995) Liposomal-entrapped doxorubicin: an active agent in AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Clin Oncol 13:914–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He B, Wang X, Shi HS, Xiao WJ, Zhang J, Mu B, Mao YQ, Wang W, Wang YS. (2013) Quercetin liposome sensitizes colon carcinoma to thermotherapy and thermochemotherapy in mice models. Integr Cancer Ther 12:264–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H, Lu Y, Qi J, Zhu Q, Chen Z, Wu W. (2018) Adapting liposomes for oral drug delivery. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidarli E, Dadashzadeh S, Haeri A. (2017) State of the art of stimuli-responsive liposomes for cancer therapy. Iran J Pharm Res 16:1273–1304. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa S, Tagawa T, Niki H, Hirakawa Y, Ito N, Nohga K, Nagaike K. (2004) Establishment and evaluation of cancer-specific human monoclonal antibody GAH for targeting chemotherapy using immunoliposomes. Hybrid Hybridomics 23:109–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Niu M, Hu F, Lu Y, Qi J, Yin Z, Wu W. (2013a) Integrity and stability of oral liposomes containing bile salts studied in simulated and ex vivo gastrointestinal media. Int J Pharm 441:693–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Haynes MT, Wang Y, Liu F, Huang L. (2013b) A highly efficient synthetic vector: nonhydrodynamic delivery of DNA to hepatocyte nuclei in vivo. ACS Nano 7:5376–5384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua S. (2014) Orally administered liposomal formulations for colon targeted drug delivery. Front Pharmacol 5:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. (2017) Preclinical and clinical advances of GalNAc-decorated nucleic acid therapeutics. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 6:116–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iinuma H, Maruyama K, Okinaga K, Sasaki K, Sekine T, Ishida O, Ogiwara N, Johkura K, Yonemura Y. (2002) Intracellular targeting therapy of cisplatin-encapsulated transferrin-polyethylene glycol liposome on peritoneal dissemination of gastric cancer. Int J Cancer 99:130–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A, Jain (2018) Advances in tumor targeted liposomes. Curr Mol Med 18:44–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain RK, Stylianopoulos T. (2010) Delivering nanomedicine to solid tumors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 7:653–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James ND, Coker RJ, Tomlinson D, Harris JR, Gompels M, Pinching AJ, Stewart JS. (1994) Liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil): an effective new treatment for Kaposi’s sarcoma in AIDS. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 6:294–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamoun WS, Oyama S, Kornaga T, Feng T, Luus L, Pham MT, Kirpotin DB, Marks JD, Geddie M, Xu L, et al. (2016) Abstract 750: nanoliposomal targeting of ephrin receptor A2 (EphA2): clinical translation. Cancer Res 76:750. [Google Scholar]

- Kan P, Tsao CW, Wang AJ, Su WC, Liang HF. (2011) A liposomal formulation able to incorporate a high content of paclitaxel and exert promising anticancer effect. J Drug Deliv 2011:629234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanasty R, Dorkin JR, Vegas A, Anderson D. (2013) Delivery materials for siRNA therapeutics. Nat Mater 12:967–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipps E, Young K, Starling N. (2017) Liposomal irinotecan in gemcitabine-refractory metastatic pancreatic cancer: efficacy, safety and place in therapy. Ther Adv Med Oncol 9:159–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirpotin DB, Drummond DC, Shao Y, Shalaby MR, Hong K, Nielsen UB, Marks JD, Benz CC, Park JW. (2006) Antibody targeting of long-circulating lipidic nanoparticles does not increase tumor localization but does increase internalization in animal models. Cancer Res 66:6732–6740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klibanov AL, Maruyama K, Torchilin VP, Huang L. (1990) Amphipathic polyethyleneglycols effectively prolong the circulation time of liposomes. FEBS Lett 268:235–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline CL, Shanmugavelandy SS, Kester M, Irby RB. (2009) Delivery of PAR-4 plasmid in vivo via nanoliposomes sensitizes colon tumor cells subcutaneously implanted into nude mice to 5-FU. Cancer Biol Ther 8:1831–1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni PS, Haldar MK, Nahire RR, Katti P, Ambre AH, Muhonen WW, Shabb JB, Padi SK, Singh RK, Borowicz PP, et al. (2014) Mmp-9 responsive PEG cleavable nanovesicles for efficient delivery of chemotherapeutics to pancreatic cancer. Mol Pharm 11:2390–2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammers T, Kiessling F, Hennink WE, Storm G. (2012) Drug targeting to tumors: principles, pitfalls and (pre-) clinical progress. J Control Release 161:175–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan KL, Ou-Yang F, Yen SH, Shih HL, Lan KH. (2010) Cationic liposome coupled endostatin gene for treatment of peritoneal colon cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis 27:307–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Thompson DH. (2017) Stimuli-responsive liposomes for drug delivery. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol 9:e1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Guo C, Feng F, Fan A, Dai Y, Li N, Zhao D, Chen X, Lu Y. (2016) Co-delivery of docetaxel and palmitoyl ascorbate by liposome for enhanced synergistic antitumor efficacy. Sci Rep 6:38787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Yang Y, Huang L. (2012) Calcium phosphate nanoparticles with an asymmetric lipid bilayer coating for siRNA delivery to the tumor. J Control Release 158:108–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SD, Huang L. (2008) Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of nanoparticles. Mol Pharm 5:496–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Ding L, Xu Y, Wang Y, Ping Q. (2009) Targeted delivery of doxorubicin using stealth liposomes modified with transferrin. Int J Pharm 373:116–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Yu Y, Shigdar S, Fang DZ, Du JR, Wei MQ, Danks A, Liu K, Duan W. (2012) Enhanced antitumor efficacy and reduced systemic toxicity of sulfatide-containing nanoliposomal doxorubicin in a xenograft model of colorectal cancer. PLoS One 7:e49277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Mori A, Huang L. (1992) Role of liposome size and RES blockade in controlling biodistribution and tumor uptake of GM1-containing liposomes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1104:95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SH, Smyth-Templeton N, Davis AR, Davis EA, Ballian N, Li M, Liu H, Fisher W, Brunicardi FC. (2011) Multiple treatment cycles of liposome-encapsulated adenoviral RIP-TK gene therapy effectively ablate human pancreatic cancer cells in SCID mice. Surgery 149:484–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Yang T, Wei S, Zhou C, Lan Y, Cao A, Yang J, Wang W. (2018) Mucus adhesion- and penetration-enhanced liposomes for paclitaxel oral delivery. Int J Pharm 537:245–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longmuir KJ, Haynes SM, Baratta JL, Kasabwalla N, Robertson RT. (2009) Liposomal delivery of doxorubicin to hepatocytes in vivo by targeting heparan sulfate. Int J Pharm 382:222–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda H. (2015) Toward a full understanding of the EPR effect in primary and metastatic tumors as well as issues related to its heterogeneity. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 91:3–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda H, Tsukigawa K, Fang J. (2016) A retrospective 30 years after discovery of the enhanced permeability and retention effect of solid tumors: next-generation chemotherapeutics and photodynamic therapy--problems, solutions, and prospects. Microcirculation 23:173–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura Y, Gotoh M, Muro K, Yamada Y, Shirao K, Shimada Y, Okuwa M, Matsumoto S, Miyata Y, Ohkura H, et al. (2004) Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of MCC-465, a doxorubicin (DXR) encapsulated in PEG immunoliposome, in patients with metastatic stomach cancer. Ann Oncol 15:517–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura Y, Maeda H. (1986) A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent smancs. Cancer Res 46:6387–6392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer LD, Bally MB, Cullis PR. (1986) Uptake of adriamycin into large unilamellar vesicles in response to a pH gradient. Biochim Biophys Acta 857:123–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer LD, Harasym TO, Tardi PG, Harasym NL, Shew CR, Johnstone SA, Ramsay EC, Bally MB, Janoff AS. (2006) Ratiometric dosing of anticancer drug combinations: controlling drug ratios after systemic administration regulates therapeutic activity in tumor-bearing mice. Mol Cancer Ther 5:1854–1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao L, Li J, Liu Q, Feng R, Das M, Lin CM, Goodwin TJ, Dorosheva O, Liu R, Huang L. (2017a) Transient and local expression of chemokine and immune checkpoint traps to treat pancreatic cancer. ACS Nano 11:8690–8706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao L, Liu Q, Lin CM, Luo C, Wang Y, Liu L, Yin W, Hu S, Kim WY, Huang L. (2017b) Targeting tumor-associated fibroblasts for therapeutic delivery in desmoplastic tumors. Cancer Res 77:719–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao L, Newby JM, Lin CM, Zhang L, Xu F, Kim WY, Forest MG, Lai SK, Milowsky MI, Wobker SE, et al. (2016) The binding site barrier elicited by tumor-associated fibroblasts interferes disposition of nanoparticles in stroma-vessel type tumors. ACS Nano 10:9243–9258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min Y, Caster JM, Eblan MJ, Wang AZ. (2015) Clinical translation of nanomedicine. Chem Rev 115:11147–11190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal R, Patel AP, Jhaveri VM, Kay SS, Debs LH, Parrish JM, Pan DR, Nguyen D, Mittal J, Jayant RD. (2018) Recent advancements in nanoparticle based drug delivery for gastrointestinal disorders. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 15:301–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullauer FB, van Bloois L, Daalhuisen JB, Ten Brink MS, Storm G, Medema JP, Schiffelers RM, Kessler JH. (2011) Betulinic acid delivered in liposomes reduces growth of human lung and colon cancers in mice without causing systemic toxicity. Anticancer Drugs 22:223–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natfji AA, Ravishankar D, Osborn HMI, Greco F. (2017) Parameters affecting the enhanced permeability and retention effect: the need for patient selection. J Pharm Sci 106:3179–3187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidhart J, Allen KO, Barlow DL, Carpenter M, Shaw DR, Triozzi PL, Conry RM. (2004) Immunization of colorectal cancer patients with recombinant baculovirus-derived KSA (Ep-CAM) formulated with monophosphoryl lipid A in liposomal emulsion, with and without granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Vaccine 22:773–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northfelt DW, Dezube BJ, Thommes JA, Levine R, Von Roenn JH, Dosik GM, Rios A, Krown SE, DuMond C, Mamelok RD. (1997) Efficacy of pegylated-liposomal doxorubicin in the treatment of AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma after failure of standard chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 15:653–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh HR, Jo HY, Park JS, Kim DE, Cho JY, Kim PH, Kim KS. (2016) Galactosylated liposomes for targeted co-delivery of doxorubicin/vimentin siRNA to hepatocellular carcinoma. Nanomaterials (Basel) 6:E141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott PA, Hu Z, Keskin DB, Shukla SA, Sun J, Bozym DJ, Zhang W, Luoma A, Giobbie-Hurder A, Peter L, et al. (2017) An immunogenic personal neoantigen vaccine for patients with melanoma. Nature 547:217–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozpolat B, Sood AK, Lopez-Berestein G. (2014) Liposomal siRNA nanocarriers for cancer therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 66:110–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passero FC, Jr., Grapsa D, Syrigos KN, Saif MW. (2016) The safety and efficacy of Onivyde (irinotecan liposome injection) for the treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer following gemcitabine-based therapy. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 16:697–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltier HJ, Kelnar K, Bader AG. (2016) Effects of MRX34, a liposomal miR-34 mimic, on target gene expression in human white blood cells (hWBCs): qRT-PCR results from a first-in-human trial of microRNA cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol 34 (Suppl):e14090. [Google Scholar]

- Povsic TJ, Lawrence MG, Lincoff AM, Mehran R, Rusconi CP, Zelenkofske SL, Huang Z, Sailstad J, Armstrong PW, Steg PG, et al. REGULATE-PCI Investigators (2016) Pre-existing anti-PEG antibodies are associated with severe immediate allergic reactions to pegnivacogin, a PEGylated aptamer. J Allergy Clin Immunol 138:1712–1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramamoorth M, Narvekar A. (2015) Non viral vectors in gene therapy- an overview. J Clin Diagn Res 9:GE01–GE06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan AP, Mukerjee A, Helson L, Gupta R, Vishwanatha JK. (2013) Efficacy of liposomal curcumin in a human pancreatic tumor xenograft model: inhibition of tumor growth and angiogenesis. Anticancer Res 33:3603–3609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riviere K, Huang Z, Jerger K, Macaraeg N, Szoka FC., Jr. (2011) Antitumor effect of folate-targeted liposomal doxorubicin in KB tumor-bearing mice after intravenous administration. J Drug Target 19:14–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth P, Hammer C, Piguet AC, Ledermann M, Dufour JF, Waelti E. (2007) Effects on hepatocellular carcinoma of doxorubicin-loaded immunoliposomes designed to target the VEGFR-2. J Drug Target 15:623–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudin CM, Marshall JL, Huang CH, Kindler HL, Zhang C, Kumar D, Gokhale PC, Steinberg J, Wanaski S, Kasid UN, et al. (2004) Delivery of a liposomal c-raf-1 antisense oligonucleotide by weekly bolus dosing in patients with advanced solid tumors: a phase I study. Clin Cancer Res 10:7244–7251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffari M, Moghimi HR, Dass CR. (2016) Barriers to liposomal gene delivery: from application site to the target. Iran J Pharm Res 15 (Suppl):3–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin U, Derhovanessian E, Miller M, Kloke BP, Simon P, Löwer M, Bukur V, Tadmor AD, Luxemburger U, Schrörs B, et al. (2017) Personalized RNA mutanome vaccines mobilize poly-specific therapeutic immunity against cancer. Nature 547:222–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffelers RM, Koning GA, ten Hagen TL, Fens MH, Schraa AJ, Janssen AP, Kok RJ, Molema G, Storm G. (2003) Anti-tumor efficacy of tumor vasculature-targeted liposomal doxorubicin. J Control Release 91:115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultheis B, Strumberg D, Kuhlmann J, Wolf M, Link K, Seufferlein T, Kaufmann J, Gebhardt F, Bruyniks N, Pelzer U. (2016) A phase Ib/IIa study of combination therapy with gemcitabine and Atu027 in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol 34(Suppl):385. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher TN, Schreiber RD. (2015) Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science 348:69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwendener RA. (2014) Liposomes as vaccine delivery systems: a review of the recent advances. Ther Adv Vaccines 2:159–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senzer N, Nemunaitis J, Nemunaitis D, Bedell C, Edelman G, Barve M, Nunan R, Pirollo KF, Rait A, Chang EH. (2013) Phase I study of a systemically delivered p53 nanoparticle in advanced solid tumors. Mol Ther 21:1096–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sercombe L, Veerati T, Moheimani F, Wu SY, Sood AK, Hua S. (2015) Advances and challenges of liposome assisted drug delivery. Front Pharmacol 6:286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah MY, Ferrajoli A, Sood AK, Lopez-Berestein G, Calin GA. (2016) microRNA therapeutics in cancer - an emerging concept. EBioMedicine 12:34–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L, Li J, Liu Q, Song W, Zhang X, Tiruthani K, Hu H, Das M, Goodwin TJ, Liu R, et al. (2018) Local blockade of interleukin 10 and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 with nano-delivery promotes antitumor response in murine cancers. ACS Nano 12:9830–9841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu K, Asai T, Fuse C, Sadzuka Y, Sonobe T, Ogino K, Taki T, Tanaka T, Oku N. (2005) Applicability of anti-neovascular therapy to drug-resistant tumor: suppression of drug-resistant P388 tumor growth with neovessel-targeted liposomal adriamycin. Int J Pharm 296:133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla A, Mishra V, Kesharwani P. (2016) Bilosomes in the context of oral immunization: development, challenges and opportunities. Drug Discov Today 21:888–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. (2018) Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 68:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W, Shen L, Wang Y, Liu Q, Goodwin TJ, Li J, Dorosheva O, Liu T, Liu R, Huang L. (2018) Synergistic and low adverse effect cancer immunotherapy by immunogenic chemotherapy and locally expressed PD-L1 trap. Nat Commun 9:2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa I, Rodrigues F, Prazeres H, Lima RT, Soares P. (2018) Liposomal therapies in oncology: does one size fit all? Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 82:741–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriraman SK, Aryasomayajula B, Torchilin VP. (2014) Barriers to drug delivery in solid tumors. Tissue Barriers 2:e29528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriraman SK, Geraldo V, Luther E, Degterev A, Torchilin V. (2015) Cytotoxicity of PEGylated liposomes co-loaded with novel pro-apoptotic drug NCL-240 and the MEK inhibitor cobimetinib against colon carcinoma in vitro. J Control Release 220:160–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein CA, Castanotto D. (2017) FDA-approved oligonucleotide therapies in 2017. Mol Ther 25:1069–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tak WY, Lin SM, Wang Y, Zheng J, Vecchione A, Park SY, Chen MH, Wong S, Xu R, Peng CY, et al. (2018) Phase III HEAT study adding lyso-thermosensitive liposomal doxorubicin to radiofrequency ablation in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma lesions. Clin Cancer Res 24:73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangutoori S, Spring BQ, Mai Z, Palanisami A, Mensah LB, Hasan T. (2016) Simultaneous delivery of cytotoxic and biologic therapeutics using nanophotoactivatable liposomes enhances treatment efficacy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Nanomedicine (Lond) 12:223–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torchilin V. (2011) Tumor delivery of macromolecular drugs based on the EPR effect. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 63:131–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torchilin VP. (2007) Targeted pharmaceutical nanocarriers for cancer therapy and imaging. AAPS J 9:E128–E147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tscheik C, Blasig IE, Winkler L. (2013) Trends in drug delivery through tissue barriers containing tight junctions. Tissue Barriers 1:e24565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Su W, Liu Z, Zhou M, Chen S, Chen Y, Lu D, Liu Y, Fan Y, Zheng Y, et al. (2012) CD44 antibody-targeted liposomal nanoparticles for molecular imaging and therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomaterials 33:5107–5114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Yao B, Li Q, Mei K, Xu JR, Li HX, Wang YS, Wen YJ, Wang XD, Yang HS, et al. (2011) Gene therapy with recombinant adenovirus encoding endostatin encapsulated in cationic liposome in coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor-deficient colon carcinoma murine models. Hum Gene Ther 22:1061–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang-Gillam A, Li CP, Bodoky G, Dean A, Shan YS, Jameson G, Macarulla T, Lee KH, Cunningham D, Blanc JF, et al. NAPOLI-1 Study Group (2016) Nanoliposomal irinotecan with fluorouracil and folinic acid in metastatic pancreatic cancer after previous gemcitabine-based therapy (NAPOLI-1): a global, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial [published correction appears in Lancet (2016) 387:536]. Lancet 387:545–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson DS, Endsley AN, Huang L. (2012) Design considerations for liposomal vaccines: influence of formulation parameters on antibody and cell-mediated immune responses to liposome associated antigens. Vaccine 30:2256–2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Wang Y, Xia D, Guo S, Wang F, Zhang X, Gan Y. (2017) Thermosensitive liposomal codelivery of HSA-paclitaxel and HSA-ellagic acid complexes for enhanced drug perfusion and efficacy against pancreatic cancer. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 9:25138–25151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicki A, Rochlitz C, Orleth A, Ritschard R, Albrecht I, Herrmann R, Christofori G, Mamot C. (2012) Targeting tumor-associated endothelial cells: anti-VEGFR2 immunoliposomes mediate tumor vessel disruption and inhibit tumor growth. Clin Cancer Res 18:454–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y, Oo NNL, Lee JP, Li Z, Loh XJ. (2017) Recent development of synthetic nonviral systems for sustained gene delivery. Drug Discov Today 22:1318–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Liu Y, Yang S, Zhang B, Wang T, Jiang D, Zhang J, Yu D, Zhang N. (2016) Sorafenib and gadolinium co-loaded liposomes for drug delivery and MRI-guided HCC treatment. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 141:83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin Y, Huang M, Guo WW, Huang Q, Zhang LZ, Jiang G. (2017) Nano-based delivery of RNAi in cancer therapy. Mol Cancer 16:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Wang Y, Zhang L, Huang L. (2014) Nanoparticle-delivered transforming growth factor-β siRNA enhances vaccination against advanced melanoma by modifying tumor microenvironment. ACS Nano 8:3636–3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Lai SK. (2015) Anti-PEG immunity: emergence, characteristics, and unaddressed questions. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol 7:655–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Su Z, Liang Y, Zhang N. (2015) pH-Sensitive carboxymethyl chitosan-modified cationic liposomes for sorafenib and siRNA co-delivery. Int J Nanomedicine 10:6185–6197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H, Kanasty RL, Eltoukhy AA, Vegas AJ, Dorkin JR, Anderson DG. (2014) Non-viral vectors for gene-based therapy. Nat Rev Genet 15:541–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalba S, Contreras AM, Haeri A, Ten Hagen TL, Navarro I, Koning G, Garrido MJ. (2015) Cetuximab-oxaliplatin-liposomes for epidermal growth factor receptor targeted chemotherapy of colorectal cancer. J Control Release 210:26–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JX, Wang K, Mao ZF, Fan X, Jiang DL, Chen M, Cui L, Sun K, Dang SC. (2013a) Application of liposomes in drug development--focus on gastroenterological targets. Int J Nanomedicine 8:1325–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Chen H, Liu AY, Shen JJ, Shah V, Zhang C, Hong J, Ding Y. (2016a) Gold conjugate-based liposomes with hybrid cluster bomb structure for liver cancer therapy. Biomaterials 74:280–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Sun F, Liu S, Jiang S. (2016b) Anti-PEG antibodies in the clinic: current issues and beyond PEGylation. J Control Release 244:184–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Kim WY, Huang L. (2013b) Systemic delivery of gemcitabine triphosphate via LCP nanoparticles for NSCLC and pancreatic cancer therapy. Biomaterials 34:3447–3458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Liu M, Sun H, Feng Y, Xu L, Chan AWH, Tong JH, Wong J, Chong CCN, Lai PBS, et al. (2018) Hepatoma-intrinsic CCRK inhibition diminishes myeloid-derived suppressor cell immunosuppression and enhances immune-checkpoint blockade efficacy. Gut 67:931–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zununi Vahed S, Salehi R, Davaran S, Sharifi S. (2017) Liposome-based drug co-delivery systems in cancer cells. Mater Sci Eng C 71:1327–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]