Abstract

The small hive beetle (SHB) is an opportunistic parasite that feeds on bee larvae, honey, and pollen. While SHBs can also feed on fruit and other plant products, like its plant‐feeding relatives, SHBs prefer to feed on hive resources and only reproduce inside bee colonies. As parasites, SHBs are inevitably exposed to bee‐associated microbes, either directly from the bees or from the hive environment. These microbes have unknown impacts on beetles, nor is it known how extensively beetles transfer microbes among their bee hosts. To identify sets of beetle microbes and the transmission of microbes from bees to beetles, a metagenomic analysis was performed. We identified sets of herbivore‐associated bacteria, as well as typical bee symbiotic bacteria for pollen digestion, in SHB larvae and adults. Deformed wing virus was highly abundant in beetles, which colonize SHBs as suggested by a controlled feeding trial. Our data suggest SHBs are vectors for pathogen transmission among bees and between colonies. The dispersal of host pathogens by social parasites via floral resources and the hive environment increases the threats of these parasites to honey bees.

Keywords: honey bee, metagenome, microbe, small hive beetle, virus

Honey bee‐associated bacteria were identified from the small hive beetles, which may facilitate the beetle thriving in the bee hive. At the mean time, the honey bee virus colonize and replicate in SHBs, dispersion of host virus by social parasites to floral resources and hives, providing additional threats to honey bees and other insects.

1. INTRODUCTION

The small hive beetle (Aethina tumida Murray, 1867, hereafter SHB) is a honey bee nest parasite belonging to the family Nitidulidae (sap beetles; c. 4,500 species), whose members feed mainly on decaying vegetable matter, over‐ripe fruit, or sap (Mckenna et al., 2015). Unlike other plant‐feeding beetles, SHBs can survive on fruit but thrive on resources found in honey bee colonies (Cuthbertson et al., 2013; Neumann & Elzen, 2004). SHB larvae are the most damaging stage for bee hives, by tunneling through combs and causing honey to ferment (Hood, 2004). These infestations can be destructive to wax combs, stored honey, and pollen. So far, the yeast Kodamaea ohmeri is known to be associated with SHBs, causing damage to the colony by fermenting stored nectar and serving as a biomarker to attract other SHBs (Benda, Boucias, Torto, & Teal, 2008). Additional symbiotic microbes associated with SHBs have not yet been described. In contrast, several symbiotic bacteria have been reported from the Asian longhorned beetle, including those that facilitate plant cell wall digestion (Scully et al., 2013), leading to insights into how these microbes impact digestion and beetle health.

Honey bee gut bacteria are dominated by nine species/clusters, some of which are likely to be involved in honey and pollen digestion, along with many low‐frequency opportunistic microbes (Kwong & Moran, 2016; Powell, Martinson, Urban‐Mead, & Moran, 2014; Raymann & Moran, 2018). As SHBs rely on food sources stored by their honey bee hosts, we predicted that SHBs might acquire honey bee‐associated microbes, which could aid in food digestion. In addition, SHBs maintain their own sets of bacteria that could aid in digestion, improving development inside the colony and when they exit as late‐stage larvae to finish development. In this study, we conducted metagenomic sequence de novo assembly to identify microbes found in larval and adult life stages of SHBs. We then confirmed those microbes using a deep RNA‐seq data set. We further conducted controlled feeding trials to determine whether candidate microbes can colonize SHBs. We have identified microbes that might facilitate the defense and development of the SHBs. We also found bee‐associated bacteria and viruses residing in SHBs. These results shed light on beetle microbe communities and help identify risks to both bees and beetles from a communal existence, as well as complex pathogen transmission routes in this ecosystem.

2. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE

2.1. Beetle collection and DNA extraction

SHBs were collected from the states of Louisiana and Maryland, USA. DNA was extracted from three adult beetles for Illumina HiSeq paired‐end sequencing in 2011. Additionally, DNA was extracted from 150 SHB larvae for PacBio sequencing in 2014. These two data sets are not related, and the sequencing was conducted at the University of Maryland. These non‐sterile adult and larval small hive beetles were scrutinized to identify microbes shared with bees, microbes unique to SHB, and microbes picked up from the hive or external (soil) environment. These two sets of DNA sequencing reads were previously used to assemble the SHB genome (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly/GCF_001937115.1/). For detailed DNA extraction and sequencing protocol, see Evans et al. (2018. Due to extremely deep sequence coverage (over 500X SHB genome coverage), we were able to accurately explore the microbial community associated with SHBs. Pooled, equimolar RNA sequencing reads of eggs, larvae, and adult beetles were previously used to construct the SHB transcriptome (over 500x SHB transcriptome coverage, as described in Tarver et al., 2016). This RNA resource was used to assess the transcriptional activity of these microbes in SHB. Both DNA and RNA sequences were previously deposited at NCBI‐Bioproject PRJNA256171.

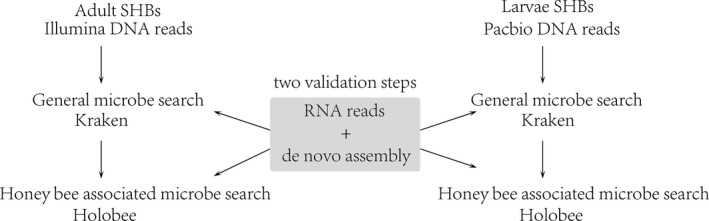

2.2. Metagenomic analysis of beetle‐associated microbes

Ilumina reads were quality checked with Fastqc (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/), and PacBio reads were error corrected with Illumina reads using proovread (Hackl, Hedrich, Schultz, & Forster, 2014). DNA and RNA reads were first aligned to the SHB genome using BWA (version 0.7.13) and Tophat2 (version 2.0.13), respectively (Kim et al., 2013; Li & Durbin, 2009). Reads aligned to the SHB genome were removed. After this filtering, 96 million Illumina DNA reads, 137 million Illumina RNA reads, and 247,186 PacBio reads (~870 million nucleotides) were maintained for microbial identification. Initially, the unmapped reads were used to screen microbial species with fully sequenced genome assemblies using Kraken with standard databases, which is designed to align short sequencing reads to sequenced microbe genomes (Wood & Salzberg, 2014) (Supporting Information S1). Kraken output files were viewed using Krona (Wood & Salzberg, 2014) (Appendix Figure A1, Figure A2 and Figure A3). In order to reduce numerous false‐positive assignments of K‐mers (subset of a read) from Kraken, a de novo metagenomic assembly was produced using unmapped Illumina DNA reads by metaSPAdes assembler (version 3.10.1) with default setting (Nurk, Meleshko, Korobeynikov, & Pevzner, 2017). The assembled contigs and unmapped PacBio long reads were used to query the Embl, Unigene, Est, Gss, Htc, Pat, RefSeq, Htg, and Tst databases using BLASTN. Best hits were tallied for searches with alignment significance of p < 0.001. Only microbes confirmed by both Kraken and the assembled contigs were kept. In order to identify bee‐associated microbes found in SHBs, the unmapped DNA and RNA reads were aligned to the HoloBee database, a curated resource for microbes associated with honey bees (https://data.nal.usda.gov/dataset/holobee-database-v20161), using BWA (version 0.7.13) and Tophat2 (version 2.0.13), respectively. Again, candidate matches were aligned against both assembled contigs and unmapped PacBio reads to reduce false‐positive assignments (Figure 1). HoloBee‐Barcode uses a variety of markers as appropriate for each taxonomic group (Supporting Information S2). Complete 16S ribosomal RNA was used for bacteria. Barcode markers for fungi are less definitive, and ribosomal RNA internal transcribed spacer region (ITS), including ITS‐1, 5.8S, and ITS‐2, was used via Holobee database. The majority of barcodes for metazoan taxa are based on the mitochondrial locus Cytochrome C oxidase subunit I. Read counts were normalized with trimmed means of M‐values (TMM) using edgeR (Robinson, McCarthy, & Smyth, 2010). Over all, there are two steps to reduce false‐positive assignment of the identified microbes. First, the microbes identified from the Kraken database and Holobee database must be supported by both DNA and RNA reads. Second, the identified microbes must show significant hit when blasting the assembled de novo contigs to Embl, Unigene, Est, Gss, Htc, Pat, Refseq, Htg, and Tst databases (p < 0.001; Supporting Information S4).

Figure 1.

Using three independently sequenced SHB samples to identify the associated microbes, adult and larval beetle DNA reads were first aligned to all sequenced microbes genomes using Kraken and validated with RNA sequencing reads. Then, the adult and larvae DNA reads were aligned to HoloBee database and again validated with RNA sequencing reads. The adult DNA reads were de novo assembled, and the contigs were aligned to Embl, Unigene, Est, Gss, Htc, Pat, Refseq, Htg, and Tst databases to further validate the species/gene origin of the contigs

2.3. Verification of the identified microbes with qPCR

To further validate the accurate assignment of microbes from sequencing, a set of microbes (Choristoneura occidentalis granulovirus, Kodamaea ohmeri, Deformed wing virus, Gilliamella apicola, and Snodgrassella alvi) was selected for qPCR validation. To accomplish this, 12 adult beetles were freshly collected from apiaries near Baltimore, Maryland, in June 2018. DNA was extracted from individual beetles, and each of 3 beetles from an apiary was pooled for qPCR analysis. For detailed protocol and results, see Appendix and Supporting Information S4.

2.4. Colonization of honey bee‐associated microbes in SHBs

We further studied whether the selected set of microbes (Choristoneura occidentalis granulovirus, Kodamaea ohmeri, Deformed wing virus, Gilliamella apicola, and Snodgrassella alvi) can colonize small hive beetles. Accordingly, an additional 10 adult beetles were collected from the honey bee hives in Beltsville, Maryland, in September 2018. Those 10 beetles were feed with sugar water for 7 days, without introduction of any bee hive products. We hypothesize that if the microbes remained in place under this controlled diet, they can could truly colonize SHBs, instead of being merely transients collected from bee hive products. After 7 days feeding, each SHB was dissected into head thorax and abdomen sections. Then, the same body sections from five SHBs were pooled for RNA/DNA extraction, to determine specific tissue colonization of microbes. Detailed DNA extraction, RNA extraction, and qPCR protocols, along with the primers and results, are described in Supporting Information S3 and S4.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Identification of microbes from the small hive beetle

In total, 66 and 23 different microbe species were found from SHB larvae (2 archaea, 55 bacteria, and 9 viruses) and adults (22 bacteria and 1 viruses), respectively (Appendix Table A1). Of those, 14 bacteria were shared between SHB larvae and adults, including 9 putatively beneficial bacteria (Table 1). The bacteria Gluconobacter oxydans, Candidatus Pantoea carbekii, secondary endosymbiont of Heteropsylla cubana, and Lactococcus lactis were found in SHB larvae, as well as a toxin‐secreting bacterium “Candidatus Profftella armatura”.

Table 1.

Symbiotic bacteria found in SHB larvae and adults and their putative functions

| Microbes | Larvae | Adults | Putative functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methanobrevibacter sp. AbM4 | D | ND | Digestion |

| Candidatus Profftella armatura | D | ND | Defensive toxin |

| Candidatus Pantoea carbekii | D | ND | Mutualists of plant‐feeding insects |

| Gluconobacter oxydans | D | ND | Synthesis of Vitamin C, D‐gluconic acid and ketogluconic acids |

| secondary endosymbiont of Heteropsylla cubana | D | ND | Insect symbiont |

| Lactococcus lactis | D | ND | Lactose digestion |

| Candidatus Portiera aleyrodidarum | D | D | Primary endosymbiont of whiteflies |

| Paenibacillus mucilaginosus | D | ND | Degrading insoluble soil minerals with the release of nutritional ions and nitrogen fixation |

| Pseudomonas putida | D | D | Breaking down aromatic or aliphatic hydrocarbons |

ND indicates the microbe was not found and D indicates the microbe was found.

3.2. Bee‐associated microbes found in the small hive beetle

As the SHB feeds on honey and pollen in honey bee colonies, these beetles are expected to receive microbes (pathogenic and symbiotic) from resident honey bees and hives. We used the Holobee database, a non‐redundant database of taxonomically informative barcoding loci for viruses, bacteria, fungi, protozoans, and metazoans associated with honey bees (https://data.nal.usda.gov/dataset/holobee-database-v20161) as a reference to identify microbial overlap between SHB and their honey bee hosts. Overall, 14 and 13 bee‐associated microbes were found in SHB larvae and adults, respectively (Table 2). Of those, seven bacteria were shared between SHB larvae and adults. We identified two additional honey bee RNA viruses in sequences derived from pooled RNA samples of all life stages.

Table 2.

Honey bee‐associated microbes found in beetle larvae and adults, and their putative functions

| Microbes | Larvae | Adult | Putative function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus licheniformis | D | ND | Environmental opportunist |

| Citrobacter freundii | D | D | Environmental opportunist |

| Enterobacter cloacae | D | D | Pathogenic |

| Enterobacter hormaechei | ND | D | Pathogenic |

| Enterococcus faecalis | D | ND | Pathogenic |

| Escherichia coli | D | D | Environmental opportunist |

| Frischella perrara | D | ND | Stimulating immunity |

| Gilliamella apicola | D | D | Digestion |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | D | D | Pathogenic |

| Kodamaea ohmeri | D | ND | Honey fermentation |

| Lactobacillus johnsonii | D | ND | Digestion |

| Lactobacillus kunkeei | ND | D | Digestion |

| Lactococcus garvieae | ND | D | Pathogenic |

| Lactococcus lactis | ND | D | Environmental opportunist |

| Moraxella osloensis | ND | D | Pathogenic |

| Myroides odoratimimus | ND | D | Pathogenic |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | D | D | Pathogenic |

| Serratia marcescens | D | ND | Pathogenic |

| Snodgrassella alvi | ND | D | Digestion |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | D | D | Pathogenic |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | D | ND | Pathogenic |

| Deformed wing virus | D (RNA) | Pathogenic | |

| Kakugo virus | D (RNA) | Pathogenic | |

ND indicates the microbe was not found and D indicates found.

3.3. Verification of the microbes with qPCR

Out of the five selected microbes, only Choristoneura occidentalis granulovirus was not confirmed, neither from adult nor larval SHBs (Table 3, Appendix Table A2). Kodamaea ohmeri was consistently found in all collected SHBs, as well as a bee‐associated symbiotic bacterium Snodgrassella alvi. A second widespread bee symbiotic bacterium Gilliamella apicola was confirmed in 3 out of 4 DNA pools. The honey bee‐associated Deformed wing virus was confirmed in pooled RNA samples of all life stages.

Table 3.

Verification of the microbes with qPCR. Deformed wing virus (DWV), Snodgrassella alvi (S. alvi), Gilliamella apicola (G. apicola), Kodamaea ohmeri (K. ohmeri), Choristoneura occidentalis granuloviru (ChocGV) were used for the assay

| Collection conditions | Samples | DWV | S. alvi | G. apicola | K. ohmeri | ChocGV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHB adults collected from the bee hives and directly used for DNA extraction (three samples per pool) | Adult pool #1 | NA | D | ND | D | ND |

| Adult pool #2 | NA | D | D | D | ND | |

| Adult pool #3 | NA | D | D | D | ND | |

| Adult pool #4 | NA | D | D | D | ND | |

| SHB adults collected from the bee hives and used for diet control assay and followed by RNA extraction (five samples per pool) | Abdomen pool #1 | D | ND | ND | D | ND |

| Abdomen pool #2 | D | ND | ND | D | ND | |

| Thorax and head pool #1 | D | ND | ND | D | ND | |

| Thorax and head pool #2 | D | ND | ND | D | ND |

ND indicates the microbe was not found; D indicates found and NA represents not applicable.

3.4. Controlled diet analysis of SHB microbes

Deformed wing virus persisted in beetles fed under a controlled diet. Gilliamella apicola and Snodgrassella alvi were found in beetles collected from colonies but were absent after the controlled diet trials. The yeast K. ohmeri was highly abundant and constantly identified both before and after the controlled diet trials. Choristoneura occidentalis granulovirus was not found in beetles either before or after diet trials.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. SHB unique microbes

Candidatus Pantoea carbekii is a known mutualism of plant‐feeding insects, which may facilitate survival and development by providing essential nutrients (Kenyon, Meulia, & Sabree, 2015). In our data, this bacterium was found in larval SHB samples, perhaps supporting the development of SHB by supplying nutrition. Protective bacteria were also found associated with SHBs. Candidatus Profftella armatura secretes polyketide toxins to protect plant‐feeding insect hosts from predators (Nakabachi et al., 2013), and it is conceivable that SHBs benefit from this bacterium when facing predators inside and outside the nest. For the Asian longhorned beetle, ten genera of bacteria were linked with lignocellulose and hemicellulose degradation (Geib, Jimenez‐Gasco, Carlson, Tien, & Hoover, 2009; Geib, Jimenez‐Gasco, Carlson, Tien, Jabbour, et al., 2009; Scully et al., 2013). Specific bacteria from the Asian longhorned beetle linked with plant digestion were not found in SHBs. However, SHBs might acquire additional bacteria from bee hives that play a similar role in plant cell wall digestion. In our data, colonization by the fungus K. ohmeri on SHB adults was verified (Table 3, Supporting Information S3). K. ohmeri causes honey fermentation and resulting volatiles act as a kairomone to mark the colony, attracting additional beetles (Hayes, Rice, Amos, & Leemon, 2015; Torto, Suazo, Alborn, Tumlinson, & Teal, 2005). Based on Kraken analysis, high numbers of Illumina reads were assigned to Choristoneura occidentalis granulovirus. However, this virus has not been found in neither de novo assembled contigs nor diet‐controlled analysis. We conclude that the k‐mer‐based assignment of Illumina reads to Choristoneura occidentalis granulovirus was a false positive caused by a long repetitive sequence in the assembled Choristoneura genome. This result demonstrates the value of following rapid heuristic searches such as Kraken with alternate forms of evidence for de novo metagenomic validation. For SHBs, the exact same microbes are not likely to be found in different life stages. Particularly, larvae must pupate in soil, quite different environmental condition compared to the bee hive. The described microbes were supported by independent data sets, reducing the chance that those microbes are falsely assigned.

4.2. Honey bee‐associated microbes found in SHBs

Out of the nine dominant bacteria species/clusters found in honey bees (Moran, 2015), four were found in SHBs, including three proteobacteria Gilliamella apicola, Frischella perrara, and Snodgrassella alvi, and one Firmicutes bacteria Lactobacillus kunkeei. The bacterium G. apicola facilitates pollen digestion and has a syntrophic effect with S. alvi that is very abundant in our study (Kešnerová et al., 2017). Acquiring this core set of honey bee bacteria arguably could help the beetle degrade pollen cell walls and digest sugars found in stored honey (Kwong & Moran, 2016). SHBs have multiple routes to acquire those bacteria, from feeding on pollen and honey, to exposure to honey bee larvae. Adult beetles also solicit food directly from their bee hosts, in the form of liquid regurgitates. Even though these symbiotic bacteria do not appear to colonize SHBs, we cannot exclude they are actively facilitating pollen and honey digestion in SHBs, as long as the beetles keep parasitizing the bee hive. Along with symbionts, SHBs host Deformed wing virus and Kakugo virus, known pathogens in honey bees. Deformed wing virus has been previously found with SHBs (Eyer, Chen, Schäfer, Pettis, & Neumann, 2009), while the others were novel to the current study. These pathogens are likely acquired orally, or via oral‐fecal transfer, as is the case with bacterial symbionts. The diet‐controlled analysis supports that Deformed wing virus can reproduce in SHBs. Furthermore, by aligning the assembled RNA sequencing contigs to the Deformed wing virus genome, both Plus/Plus and Plus/Minus matches were found. This suggests that Deformed wing virus is replicating and actively infective in SHBs, although this result should be confirmed. For one, it is conceivable that sequenced beetles have consumed honey bee eggs or larvae that themselves were infected. Regardless, SHBs are likely to act as vectors for pathogen transmission among bees and between colonies.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

JDE and QH designed the work, performed metagenomic analysis, and wrote the manuscript. DL performed qPCR validation and analyzed the data.

ETHICS STATEMENT

None required.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank James P. Tauber for providing K. ohmeri primer sequences. J.P.T. recognizes funding from the USDA‐ARS via ORISE (DE‐SC0014664). We appreciate the Competence Centre in Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, SWISS institute of Bioinformatic (Vital‐IT) for bioinformatic support. The project is supported by Ernst Göhner Stiftung, 2018‐0397/3.

APPENDIX 1.

Detailed material and methods

DNA extraction for Illumina Hiseq‐2000 paired‐end sequencing

Genomic DNA was collected from three individual beetles from a laboratory colony at USDA, ARS Honey Bee Breeding, Genetics and Physiology Laboratory, Baton Rouge, LA, USA, at 2011. New beetles from field collections get added into the colony approximately every other month. The beetles were reared in honey combs including honey, pollen, and brood. To collect genomic DNA, the elytra were removed from each of three individual male beetles and genomic DNA was extracted using the Maxwell 16 Tissue DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Madison WI) following the manufacturer protocol and eluted using their elution buffer. Eluted gDNA was then analyzed using a Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington DE). The samples were not sterilized before the extraction, and the libraries were prepared without PCR amplification or polyA purification. In total, 12 libraries were prepared from the same pooled DNA following manufacturer protocol.

DNA extraction for Pacbio sequencing and qPCR

SHB larvae were collected from a continuous culture of small hive beetles maintained at the USDA‐ARS Bee Research Laboratory, Beltsville, Maryland, USA, at 2014. The beetles were reared in honey combs, including honey, pollen, and brood. DNA was extracted from a total of 150 s‐instar larvae in 30 groups of five larvae each. Larvae were crushed using a plastic pestle in 1 ml of freshly prepared CTAB buffer consisting of 100 mM Tris‐HCl (ph 8.0), 20 mM EDTA (ph. 8.0), 1.4 M NaCl, 2% CTAB, and 0.2% B‐mercaptoethanol. The suspension was incubated at 65°C for 60 min, with gentle mixing at 0, 20, and 40 min. Samples were centrifuged for 2 min at 14 k rpm (2081 g) in an Eppendorf microcentrifuge tube rotor. 500 μl of the supernatant was moved into a new tube containing using a wide‐bore pipette into a sterile tube containing 500 μl chloroform:isoamylalcohol (24:1). After gentle mixing by hand, tubes were centrifuged at 14 k rpm for 15 min. Approximately 400 μl of the aqueous layer was transferred into new tubes containing 250 μl cold isopropanol, followed by gentle mixing and incubation at 4°C for 30 min. Samples were centrifuged at 14 k rpm for 30 min a 4°C, and then, the supernatant was poured off. Pellets were washed with 1 ml cold 75% EtOH and centrifuged again for 2 min (14 k rpm). After the supernatant was poured off, the resulting pellets were washed in 1 ml cold 100% EtOH, centrifuged for 2 min, after which the EtOH was poured off, the pellets were spun for an additional 30 s, and the last of the wash was removed by pipette. Pellets were air‐dried for 30 min, and the resulting DNA pellet was resuspended in 50 μl ddH20. Samples were incubated for 30 min with 2.5 μl of an RNAse cocktail at 37oC, followed by gentle addition of 5 μl 7 M NaOac and 100 μl EtOH. After 30 min of incubation on wet ice, the DNA samples were spun at 12 k rpm for 30 min, washed once with 7% EtOH, dried and suspended in 20 μl ddH20. Extracts were pooled and assayed by gel electrophoresis to ensure DNA integrity and by Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher, Inc.) for quantification (180 ng/μl in 25 μl, 45 μg total DNA). The samples were not sterilized before the extraction, and the libraries were prepared without PCR amplification or polyA purification. In total, 40 SMRT cells were prepared from the same pooled DNA following manufacturer protocol.

Two‐step quantitative PCR for microbe validation

The below variant of qPCR is for a 96‐well plate format on the CFX96 real‐time system (Bio‐Rad) or related machines and works for both bee transcripts and pathogen targets. The primary difference over the prior protocol is that this one is initiated with cDNA generated in a non‐specific way, rather than from de novo reverse‐transcription for each viral and/or host test and control (as shown in the previous section).

Mix 1× SsoAdvanced™ Universal SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio‐Rad) with 4 mM of each forward and reverse primer for a given target (final volume 20 μl).

Add 1 μl (~8 ng) of cDNA template to specific wells.

-

Use the following cycling conditions:

95°C for 1 min,

-

45 (maximum 50) cycles of:

95°C for 5 s,

60°C for 30 s,

Melt curve from 65–95°C at + 0.5°C/5 s increments.

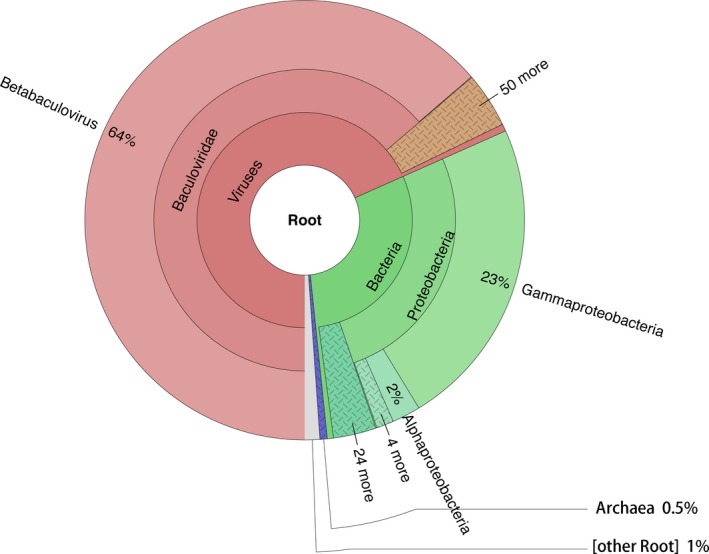

Figure A1.

Taxonomic distributions of classified microbes associated with small hive beetle eggs, larvae, and adults. The total RNA was extracted from eggs, larvae, and adults, respectively, and then pooled for Illumina paired‐end RNA sequencing. Numbers refer to the proportion of classified sequencing reads

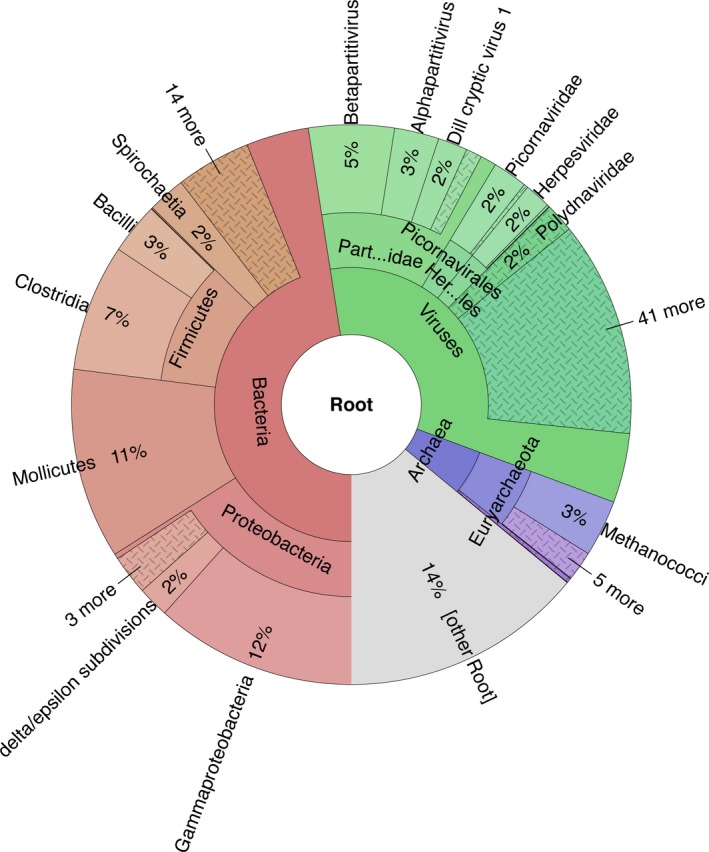

Figure A2.

Taxonomic distributions of classified microbes associated with small hive beetle adults. Numbers refer to the proportion of classified sequencing reads

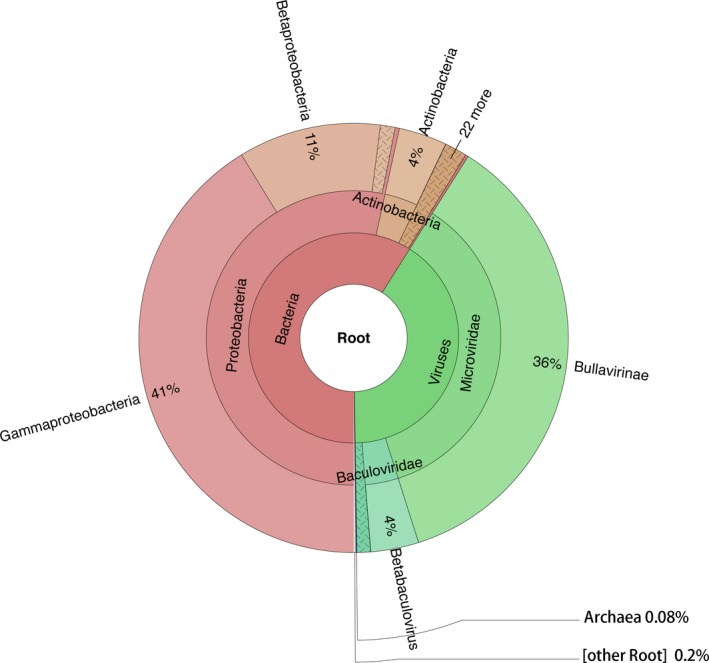

Figure A3.

Taxonomic distributions of classified microbes associated with small hive beetle larvae. Numbers refer to the proportion of classified sequencing reads

Table A1.

Identified microbes from SHB larvae and adults, normalized reads (counts per million reads) and putative function

| Kingdom | Microbes | Larvae | Adults | Putative function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archaea | Methanobacterium lacus | 194 | #N/A | |

| Archaea | Methanobrevibacter sp. AbM4 | 3,101 | #N/A | Digestion |

| Bacteria | Acinetobacter baumannii | 388 | #N/A | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Arcobacter sp. L | 581 | #N/A | |

| Bacteria | Bacillus anthracis | 388 | #N/A | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Bacillus cereus | 2,907 | #N/A | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus | 194 | #N/A | Parasite of other bacteria |

| Bacteria | Blattabacterium sp. (Blaberus giganteus) | 388 | #N/A | |

| Bacteria | Brachyspira pilosicoli | 4,845 | #N/A | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Buchnera aphidicola | 24,806 | #N/A | |

| Bacteria | Burkholderia pseudomallei | #N/A | 9 | |

| Bacteria | Burkholderia sp. RPE64 | 388 | #N/A | |

| Bacteria | Campylobacter fetus | 775 | #N/A | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Candidatus Babela massiliensis | 388 | #N/A | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Candidatus Pantoea carbekii | 775 | #N/A | Mutualists of plant‐feeding insects |

| Bacteria | Candidatus pelagibacter sp. IMCC9063 | 969 | #N/A | |

| Bacteria | Candidatus Phytoplasma mali | 3,295 | #N/A | Pathogen, plant |

| Bacteria | Candidatus Portiera aleyrodidarum | 194 | 9 | Primary endosymbiont of whiteflies |

| Bacteria | Candidatus Profftella armatura | 2,713 | #N/A | Defensive toxin |

| Bacteria | Clostridioides difficile | 581 | #N/A | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Coxiella burnetii | 194 | #N/A | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Cutibacterium acnes | #N/A | 22,901 | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Cyanothece sp. ATCC 51142 | 194 | #N/A | |

| Bacteria | Cyanothece sp. PCC 7822 | 581 | #N/A | |

| Bacteria | Dokdonia sp. 4H‐3‐7‐5 | 194 | #N/A | |

| Bacteria | Enterobacter cloacae | 581 | 14,713 | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Enterococcus faecalis | 1,744 | 3,334 | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Escherichia coli | 15,891 | 4,222 | |

| Bacteria | Flavobacteriaceae bacterium 3519‐10 | #N/A | 84 | Unclear |

| Bacteria | Fusobacterium nucleatum | 1,550 | 210 | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Gluconobacter oxydans | 581 | #N/A | Synthesis of Vitamin C, D‐gluconic acid and ketogluconic acids |

| Bacteria | Haemophilus influenzae | 7,752 | 157 | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Helicobacter pylori | 3,682 | #N/A | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Herminiimonas arsenicoxydans | #N/A | 67 | Neurtal |

| Bacteria | Histophilus somni | 3,101 | 84 | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 1,938 | 1,351 | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Lacinutrix sp. 5H‐3‐7‐4 | 388 | #N/A | |

| Bacteria | Lactococcus lactis | 388 | #N/A | Lactose digestion, hinder pathogenic bacteria |

| Bacteria | Melissococcus plutonius | 194 | #N/A | European foulbrood |

| Bacteria | Methylobacterium sp. 4‐46 | 388 | #N/A | |

| Bacteria | Mycoplasma conjunctivae | 1,550 | #N/A | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae | 101,938 | #N/A | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Mycoplasma hyorhinis | 10,271 | #N/A | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Mycoplasma leachii | 2,713 | #N/A | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Mycoplasma mycoides | 2,132 | #N/A | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Neisseria meningitidis | 969 | #N/A | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Paenibacillus mucilaginosus | 2,132 | #N/A | Degrade insoluble soil minerals with the release of nutritional ions and fix nitrogen |

| Bacteria | Pasteurella multocida | 388 | 99 | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Photorhabdus asymbiotica | 33,527 | 20 | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Porphyromonas gingivalis | #N/A | 87 | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Prochlorococcus marinus | 2,132 | #N/A | Oxygen |

| Bacteria | Proteus mirabilis | 388 | #N/A | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7367 | 12,984 | #N/A | |

| Bacteria | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 2,326 | 257,695 | Disease |

| Bacteria | Pseudomonas putida | #N/A | 673 | Breaking down aromatic or aliphatic hydrocarbons |

| Bacteria | Pseudomonas stutzeri | #N/A | 480 | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Riemerella anatipestifer | #N/A | 233 | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Rivularia sp. PCC 7116 | 581 | #N/A | |

| Bacteria | Secondary endosymbiont of Heteropsylla cubana | 388 | #N/A | Insect symbiont |

| Bacteria | Serratia marcescens | 13,953 | 3 | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Shigella flexneri | 2,907 | 594 | |

| Bacteria | Shigella flexneri | 2,907 | 594 | |

| Bacteria | Sorangium cellulosum | 1,163 | #N/A | Soil bacteria |

| Bacteria | Streptococcus agalactiae | 194 | #N/A | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Streptococcus anginosus | 581 | #N/A | Pathogen |

| Bacteria | Streptococcus pneumoniae | 388 | 82 | Pathogen |

| Virus | Anomala cuprea entomopoxvirus | 581 | #N/A | |

| Virus | Apocheima cinerarium nucleopolyhedrovirus | 775 | #N/A | |

| Virus | Gryllus bimaculatus nudivirus | 581 | #N/A | |

| Virus | Human alphaherpesvirus 3 | 194 | #N/A | |

| Virus | Invertebrate iridescent virus 6 | 194 | #N/A | |

| Virus | Lymphocystis disease virus—isolate China | 194 | #N/A | |

| Virus | Megavirus chiliensis | 388 | #N/A | |

| Virus | Orgyia leucostigma NPV | 775 | #N/A | |

| Virus | Suid alphaherpesvirus 1 | 194 | #N/A | |

| Virus | Enterobacteria phage phiX174 sensu lato | #N/A | 555,038 |

Table A2.

qPCR validation results for the microbes. A set of beetle (Choristoneura occidentalis granulovirus and Kodamaea ohmeri) and bee‐associated microbe (Deformed wing virus, Gilliamella apicola, Snodgrassella alvi, and Melissococcus plutonius) were further used for qPCR verification. Generally, the validation is consistent with metagenomic assembly assignment

| Microbes | RNA of all life stages | DNA of larvae | DNA of adult | Primer 1 | Primer 2 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deformed wing virus | Yes | NA | NA | GAGATTGAAGCGCATGAACA | TGAATTCAGTGTCGCCCATA | vanEngelsdorp et al. (2009) |

| Gilliamella apicola | NA | No | Yes | GTATCTAATAGGTGCATCAATT | TCCTCTACAATACTCTAGTT | Schwarz, Moran, and Evans (2016) |

| Snodgrassella alvi | NA | No | Yes | CTTAGAGATAGGAGAGTG | TAATGATGGCAACTAATGACAA | Schwarz et al. (2016) |

| Choristoneura occidentalis granulovirus | NA | No | No | TACATGGTBACNGARGA | AAYTCYTTNCCGCTCCAGTT | Krejmer‐Rabalska, Rabalski, Souza, Moore, and Szewczyk (2018) |

| Kodameae ohmeri | NA | Yes | Yes | GAGTGAAGCGGCAAAAGCTC | AACATAGACACGGTCGCCTC | Designed by J. P. Tauber (unpublished data) |

| Melissococcus plutonius | NA | Yes | No | ACGCCTTAGAGATAAGGTTTC | GCTTAGCCTCGCGGTCTTGCGTC | Evans (2006) |

Yes represents the primers can be amplified. No represents the primers cannot be amplified. NA represents the primers is not conducted for qPCR assay.

Huang Q, Lopez D, Evans JD. Shared and unique microbes between Small hive beetles (Aethina tumida) and their honey bee hosts. MicrobiologyOpen. 2019;8:e899 10.1002/mbo3.899

Contributor Information

Qiang Huang, Email: qiang-huang@live.com.

Jay D. Evans, Email: Jay.Evans@ARS.USDA.GOV.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

DNA and RNA sequencing reads were previously deposited at NCBI‐BioProject PRJNA256171.

REFERENCES

- Benda, N. D. , Boucias, D. , Torto, B. , & Teal, P. (2008). Detection and characterization of Kodamaea ohmeri associated with small hive beetle Aethina tumida infesting honey bee hives. Journal of Apicultural Research, 47, 194–201. [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbertson, A. G. S. , Wakefield, M. E. , Powell, M. E. , Marris, G. , Anderson, H. , Budge, G. E. , … Mike, M. A. (2013). The small hive beetle Aethina tumida: A review of its biology and control measures. Current Zoology, 59, 644–653. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J. D. (2006). Beepath: An ordered quantitative –PCR array for exploring honey bee immunity and disease. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 93, 135–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J. D. , McKenna, D. , Scully, E. , Cook, S. C. , Dainat, B. , Egekwu, N. , … Huang, Q. (2018). Genome of the small hive beetle (Aethina tumida, Coleoptera: Nitidulidae), a worldwide parasite of social bee colonies, provides insights into detoxification and herbivory. Gigascience, 7, giy138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyer, M. , Chen, Y. P. , Schäfer, M. O. , Pettis, J. , & Neumann, P. (2009). Small hive beetle, Aethina tumida, as a potential biological vector of honeybee viruses. Apidologie, 40, 419–428. [Google Scholar]

- Geib, S. M. , Jimenez‐Gasco, M. D. M. , Carlson, J. E. , Tien, M. , & Hoover, K. (2009). Effect of host tree species on cellulase activity and bacterial community composition in the gut of larval Asian longhorned beetle. Environmental Entomology, 38, 686–699. 10.1603/022.038.0320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geib, S. M. , Jimenez‐Gasco, M. D. M. , Carlson, J. E. , Tien, M. , Jabbour, R. , & Hoover, K. (2009). Microbial community profiling to investigate transmission of bacteria between life stages of the wood‐boring beetle, Anoplophora glabripennis . Microbial Ecology, 58, 199–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackl, T. , Hedrich, R. , Schultz, J. , & Forster, F. (2014). proovread: Large‐scale high‐accuracy PacBio correction through iterative short read consensus. Bioinformatics, 30, 3004–3011. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, R. A. , Rice, S. J. , Amos, B. A. , & Leemon, D. M. (2015). Increased attractiveness of honeybee hive product volatiles to adult small hive beetle, Aethina tumida, resulting from small hive beetle larval infestation. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 155, 240–248. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, W. M. (2004). The small hive beetle, Aethina tumida: A review. Bee World, 85, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon, L. J. , Meulia, T. , & Sabree, Z. L. (2015). Habitat visualization and genomic analysis of “Candidatus Pantoea carbekii”, the primary symbiont of the brown marmorated stink bug. Genome Biology and Evolution, 7, 620–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kešnerová, L. , Mars, R. A. T. , Ellegaard, K. M. , Troilo, M. , Sauer, U. , & Engel, P. (2017). Disentangling metabolic functions of bacteria in the honey bee gut. PLoS Biology, 15, e2003467 10.1371/journal.pbio.2003467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D. , Pertea, G. , Trapnell, C. , Pimentel, H. , Kelley, R. , & Salzberg, S. L. (2013). TopHat2: Accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biology, 14, R36 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krejmer‐Rabalska, M. , Rabalski, L. , de Souza, M. L. , Moore, S. D. , & Szewczyk, B. (2018). New Method for differentiation of Granuloviruses (Betabaculoviruses) based on multitemperature single stranded conformational polymorphism. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 19, 83 10.3390/ijms19010083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong, W. K. , & Moran, N. A. (2016). Gut microbial communities of social bees. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 14, 374–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. , & Durbin, R. (2009). Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows‐Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics, 25, 1754–1760. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mckenna, D. D. , Wild, A. L. , Kanda, K. , Bellamy, C. L. , Beutel, R. G. , Caterino, M. S. , … Farrell, B. D. (2015). The beetle tree of life reveals that Coleoptera survived end‐Permian mass extinction to diversify during the Cretaceous terrestrial revolution. Systematic Entomology, 40, 835–880. 10.1111/syen.12132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moran, N. A. (2015). Genomics of the honey bee microbiome. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 10, 22–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakabachi, A. , Ueoka, R. , Oshima, K. , Teta, R. , Mangoni, A. , Gurgui, M. , … Fukatsu, T. (2013). Defensive bacteriome symbiont with a drastically reduced genome. Current Biology, 23, 1478–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, P. , & Elzen, P. J. (2004). The biology of the small hive beetle (Aethina tumida, Coleoptera: Nitidulidae): Gaps in our knowledge of an invasive species. Apidologie, 35, 229–247. [Google Scholar]

- Nurk, S. , Meleshko, D. , Korobeynikov, A. , & Pevzner, P. A. (2017). metaSPAdes: A new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Research, 27, 824–834. 10.1101/gr.213959.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell, J. E. , Martinson, V. G. , Urban‐Mead, K. , & Moran, N. A. (2014). Routes of acquisition of the gut microbiota of the honey bee Apis mellifera . Applied and Environment Microbiology, 80, 7378–7387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymann, K. , & Moran, N. A. (2018). The role of the gut microbiome in health and disease of adult honey bee workers. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 26, 97–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, M. D. , McCarthy, D. J. , & Smyth, G. K. (2010). edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics, 26, 139–140. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, R. S. , Moran, N. A. , & Evans, J. D. (2016). Early gut colonizers shape parasite susceptibility and microbiota composition in honey bee workers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(33), 9345–9350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scully, E. D. , Geib, S. M. , Hoover, K. , Tien, M. , Tringe, S. G. , Barry, K. W. , … Carlson, J. E. (2013). Metagenomic profiling reveals lignocellulose degrading system in a microbial community associated with a wood‐feeding beetle. PLoS ONE, 8, e73827 10.1371/journal.pone.0073827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarver, M. R. , Huang, Q. , de Guzman, L. , Rinderer, T. , Holloway, B. , Reese, J. , … Evans, J. D. (2016). Transcriptomic and functional resources for the small hive beetle Aethina tumida, a worldwide parasite of honey bees. Genomics Data, 9, 97–99. 10.1016/j.gdata.2016.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torto, B. , Suazo, A. , Alborn, H. , Tumlinson, J. H. , & Teal, P. E. A. (2005). Response of the small hive beetle (Aethina tumida) to a blend of chemicals identified from honeybee (Apis mellifera) volatiles. Apidologie, 36, 523–532. [Google Scholar]

- vanEngelsdorp, D. , Evans, J. , Saegeman, C. , Haubruge, E. , Nguyen, B. K. , Frazier, M. , … Pettis, J. S. (2009). Colony collapse disorder: A descriptive study. PLoS ONE, 4(8), e6481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood, D. E. , & Salzberg, S. L. (2014). Kraken: Ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biology, 15, R46 10.1186/gb-2014-15-3-r46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

DNA and RNA sequencing reads were previously deposited at NCBI‐BioProject PRJNA256171.