Abstract

Background:

Prior research has reported that plate size may influence an individual’s perceptions and recall of food and meal size. Therefore, manipulating plate size could influence projected meal quantities and portion size among community dwelling adults.

Methods:

The present study interviewed 281 adult parents in their own homes in a medium-sized city in the United States. Participants were asked to accurately draw and label the foods they expected to eat for dinner that night, drawing on either a 23 cm or 28 cm paper plate. The respondents were then asked to label each food drawn in order to ensure proper recording of meals.

Results:

Results showed clear differences in drawn food sizes between plate sizes as well as between sexes. Larger plates had about 24% more food drawn on them than small plates. Men drew their meals on 28 cm plates to be 37% larger than men who received 23 cm plates, while women with 28 cm plates drew their meals to be about 17% larger than women given 23 cm plates. Most (60%) of the overall differences in food size between plates came from the biggest food that was drawn. Women and men both drew bigger meat portions on 28 cm plates when compared to the meat portions on 23 cm plates.

Conclusions:

Overall, these findings support the concept that adult participants’ estimates of dinner meal size may be shaped by plate size. The effect of differing plate sizes appears to be more powerful for men than women, and may encourage greater food consumption among men, primarily as meat products.

Keywords: Eating Behavior, Food Choice, Nutrition Surveys, Plate Size Effect, Meal Planning

Introduction

People in Western societies usually consume foods grouped on tableware, often plates. The size of plates may influence how much and which types of food a person serves themselves or is served, which subsequently may have an effect on portion size and food type [1]. This study examined whether community dwelling adults differently portrayed how much and what types of foods they planned to eat on bigger or smaller plates.

Most studies of the effects of tableware on food selection manipulate plate, bowl, or serving utensil size as individuals serve themselves or are served foods [1, 2, 3, 4]. An alternative research technique, labeled “plate-mapping,” [5] has individuals draw a meal on differently-sized plates.

In an initial study using plate mapping [5], researchers asked college students to draw a meal on either a 23 cm or 28 cm diameter paper plate. The findings revealed that students exhibited plate size sensitivity because they drew about 26% more food on the larger plate than students given the smaller plate. The larger plates had about 50% more available space to draw upon, which made the food drawings on the larger plates appear smaller when observed within the context of the plate. The sex of these students moderated the relationship between plate size and meal composition in that initial study as indicated by the size of food types, with women drawing 36% bigger vegetable portions than men on larger plates. This plate mapping measurement method has been subsequently validated through objectively measured behavior in a college student sample [6]. Participants were approached directly before or directly after the consumption of a meal at a college cafeteria and asked to either draw the meal that they were about to consume or draw the meal that they had just consumed. Paper plates 23 cm in diameter that were identical to the size of the plates used in the cafeteria and larger 28 cm plates were randomly distributed to participants to use in drawing their meals. Results from this study showed that these participants were able to draw the sizes of their food items with a high degree of accuracy prior to consuming as well as after consuming a meal on both sizes of plates.

Prior studies of the size of dishware and intake of food had mixed findings and were conducted from samples of college students and patients in medical facilities. Some of these studies observed no difference in energy intake between those using larger and smaller dishware [7, 8] while other studies report an interaction between plate size and portion size [9, 10, 11, 2]. These prior studies of plate size and food intake conducted in college or medical settings, while providing more control over the variables being tested, may not have ecological validity to generalize their findings to households or realistic eating situations of community dwelling adults [12, 13, 14].

The present study used plate mapping to examine plate sensitivity and meal composition in the homes of an adult population whose behaviors may be differently shaped by their experiences, home environments, and family roles than college students. Using a plate mapping protocol in an adult community sample is important for both proof of concept of plate size sensitivity and generalizability of findings into households where the broader population usually eats. This lack of generalizability is due to the college environments being more homogenous than the environments of nonstudent subjects [15] and not necessarily representing domestic practices or behaviors that will be continued past graduation [16]. Adults’ cooking skills, financial resources, time availability, and interactions with other family members are all part of the external environment involved in food selection that may be associated with meal composition and serving portions of each type of food.

We propose four hypotheses about plate sizes and plate mapping. 1) The plate sensitivity hypothesis posits that people are flexible with portion sizes [17] and fill plates according to how much food they can hold, drawing bigger overall meal sizes on larger plates than they would on smaller plates. 2) The meal norms hypothesis posits that people draw meals to conform to normative social conceptions about how full a plate should be; filling plates to levels that seem appropriate to the plate size, with the same percentage of area covered by food on larger and smaller plates. 3) The meal composition hypothesis posits that plate size influences serving of different kinds of foods, with the type of food sub-hypothesis proposing that bigger vegetable dishes will be drawn on larger plates than smaller plates, and the food course sub-hypothesis proposing that bigger main courses will be drawn on larger plates than smaller plates. 4) The sex moderation hypothesis posits that differences between sexes in food selection and size [18, 19, 20] occur in plate size effects upon food choice, with men more sensitive to plate size than are women, and men drawing larger main courses on plates than women draw on plates.

Methods

A study was conducted in the homes of adult participants recruited by local Cooperative Extension workers and internet and radio advertisements in one medium sized city in the Northeastern U.S. As part of this larger study, participants were asked to draw what they planned to eat for dinner that night using either a 23 cm or 28 cm paper plate. Interviewers provided the plates and orally administered instructions for this study. The instructions were to “Accurately draw and label the foods that you expect to be eating for dinner tonight. Be as realistic as possible with the sizes of the foods that you are drawing.” Investigators did not provide examples of how to complete this task, nor were any food-related cues provided to assist participants in determining meal or portion size. A prior study asking participants to accurately draw their meal on plates reported that participants were capable of accurately drawing their foods both when the plate was the same size from which they habitually ate from as well as when the plate was larger than from which they usually ate from [6]. A random number generator was used to determine which differently sized but otherwise identical plate, a 23 cm diameter or 28 cm diameter, was provided to each participant. Homes where multiple individuals were participating were randomized at the household level rather than the participant level and provided the same sized plate. This was done to avoid potential plate size recognition bias. Participants were interviewed in separate rooms to avoid discussions between them about the study protocol or dinner plans. Both partners in these couples were included as individual units of analysis in the data based on preliminary analyses showing that stratification, i.e. controlling for household in a hierarchical model, revealed no significant differences between married/cohabiting and unmarried individuals with respect to the major study outcomes. This study procedures were approved by the University Institutional Review Board.

Of the 309 participants recruited, 281 (91%) took part in the plate mapping exercise. A total of 164 were members of cohabitating adult pairs or married couples. Reasons for nonparticipation included participants not completing a usable plate drawing (19), interviewer omission errors (5), or the participants enrolled over the telephone and were not present to draw on plates (4).

Participants self-labelled all of the foods they drew to provide accurate information. Drawn foods were first coded by food type (meat, grain, vegetable, root vegetable or tuber, fruit, legume, dessert, other) and then were organized by size based on their overall drawn area (most to least of the plate area covered with food). Foods were coded by area rather than by course (appetizer, main course, side course/dish, salad, dessert, etc.) for two reasons. First, participants were not instructed to label their foods by course because this could have influenced participants to draw a meal guided by Western cultural ideals about main courses and side courses [21] rather than their actual anticipated meal. Second, investigators did not want to presume which foods constituted main courses or side courses. To limit these potential biases, the horizontal dimension of area was used as an indicator of overall size of each drawn food and these sizes were then coded starting with the biggest food on each plate. For the purposes of this analysis, the food occupying the greatest area was designated the main course and subsequent foods were labeled in order of size. Horizontal measurement of area as an indication of overall food volume was based on mathematical modeling of food sizes [22]. Four original coders performed the initial coding, and then two additional coders verified the initial coding for area, food type, and food size for accuracy.

Descriptive statistics for all variables using percentages and means + standard deviations were first calculated. Next, bivariate comparisons of larger and smaller plates were made using Chi-square and t-tests to examine the plate sensitivity, meal norms, and plate composition hypotheses. Finally, further bivariate comparisons between sex, plate size, and the plate drawing variables were performed to examine the sex moderation hypothesis. Multiple statistical tests were conducted with Bonferroni corrections to acknowledge the risk of Type I error [23]. Based on this correction, we report the p-values in Table 1 as statistically significant if p < .016 and Table 2 as statistically significant if p < .008. Results that fall between these numbers and .05 are also reported so that readers can decide which level of significance they want to use to consider multiple comparisons. The independent variable was plate size. Dependent outcome variables were overall plate coverage (as total area and as percent of plate covered by food), individual food size coverage by area, food item size (largest course to smallest course for the five biggest foods), and food item type. Participant sex was examined as a moderating variable. All data analyses were performed using SPSS (22.0; IBM)

TABLE 1:

DEMOGRAPHICS, PLATE DRAWING COVERAGE, FOOD TYPES, AND FOOD ITEMS BY PLATE SIZE

| Total Sample | n | 28 cm Plates | n | 23 cm Plates | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||

| Male | 31% | 86 | 34% | 47 | 27% | 39 |

| Female | 69% | 195 | 66% | 92 | 73% | 103 |

| Age (years) | 38.6+ 9.6 | 281 | 38.3 | 139 | 39.1 | 142 |

| Drawing Coverage | ||||||

| Total Food Area (cm2) | 87.9 + 34.0 | 281 | 98.8+40.4* | 139 | 78.5 + 23.1* | 142 |

| Plate Coverage | 68% + 25% | 281 | 60% + 25%* | 139 | 76% + 22%* | 142 |

| Drawn Foods Type | ||||||

| Meat (cm2) | 31.8 + 17.8 | 243 | 37.1 + 21.1* | 119 | 26.4 + 11.9* | 124 |

| Grain (cm2) | 30.0 + 18.8 | 192 | 33.3 + 22.1* | 91 | 26.7 + 14.7* | 101 |

| Vegetable (cm2) | 28.4 + 18.0 | 289 | 32.0 + 21.3* | 119 | 25.1 + 13.5* | 147 |

| Drawn Foods Item Size | ||||||

| Biggest (cm2) | 43.2 + 22.1 | 281 | 48.8+ 26.2* | 139 | 36.3 + 15.2* | 142 |

| Second (cm2) | 27.2 + 10.9 | 273 | 29.2+ 12.2* | 134 | 24.1 + 9.4* | 139 |

| Third (cm2) | 19.6 + 9.1 | 254 | 20.8+ 10.9* | 124 | 17.5 + 6.6* | 130 |

Differences between 23 cm and 28 cm plates using chi-square and t-tests

significant at p < .016 after adjusting for multiplicity (cm2) equals centimeters squared

TABLE 2:

PLATE DRAWING COVERAGE, FOOD TYPES, AND FOOD ITEMS BY PLATE SIZE AND GENDER

| 28 cm Males | n | 23 cm Males | mn | 28 cm Females | n | 9 cm Females | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drawing Coverage | ||||||||

| Total Food Area (cm2) | 112.0 + 45.0* | 47 | 81.8 + 21.1* | 39 | 90.4 + 37.8A | 92 | 77.2 + 23.9A | 103 |

| Plate Coverage | 69% + 28% | 47 | 79% + 20% | 39 | 56% + 22%* | 92 | 75% + 23%* | 103 |

| Drawn Foods Type | ||||||||

| Meat (cm2) | 48.5 + 21.3* | 38 | 30.0 + 12.4* | 35 | 32.8 + 19.3* | 83 | 25.7 + 11.4* | 89 |

| Grain (cm2) | 37.6 + 25.9 | 33 | 33.8 + 15.0 | 26 | 33.8 + 20.1A | 58 | 25.4 + 14.5A | 75 |

| Vegetable (cm2) | 37.8 + 23.6* | 47 | 23.4 + 9.4* | 39 | 32.3 + 20.1 | 96 | 28.2 + 14.7 | 108 |

| Drawn Food Item Size | ||||||||

| Biggest (cm2) | 56.6 + 30.5* | 47 | 37.6 + 12.4* | 39 | 44.7 + 22.9A | 92 | 35.8 + 16.3A | 103 |

| Second (cm2) | 32.5 + 13.7A | 46 | 26.2 + 10.4A | 39 | 27.4 + 11.2 | 88 | 23.4 + 8.4 | 100 |

| Third (cm2) | 24.9 + 13.0* | 42 | 18.3 + 5.6* | 35 | 18.8 + 9.1 | 82 | 17.3 + 7.1 | 95 |

Differences between 23 cm and 28 cm plates of the same gender using chi-square and t-tests

significant at p < .008 after adjusting for multiplicity

not significant after adjusting for multiplicity, but p < .05 (cm2) equals centimeters squared

Results

Among the 281 participants, 139 drew on 28 cm plates and 142 on 23 cm plates. Table 1 summarizes all study variables. Most participants were female and middle aged. Men and women comprised about the same percentage of the 28 cm plate group and the 23 cm plate group. Most people (84%) drew three foods as comprising a complete dinner. Several food types and food sizes were infrequently drawn and had little variation in size, including root vegetables (n=84), fruits (n=24), legumes (n=8), desserts (n=3), and other (n=9), as well as the fourth biggest food (n=44) and fifth biggest food (n = 6). These less frequently named categories offered limited statistical power for hypothesis testing and were not analyzed further. Additionally, no participants in this study drew more than five items on their plate or requested a second plate to supplement the drawn size of their dinner.

Our first hypothesis (plate sensitivity) was that larger plates would influence participants to draw bigger dinners than the people drawing dinners on smaller plates. This hypothesis was supported, with individuals drawing about 8 cm2 more area of food on 28 cm plates (p < .001) (Table 1). Participants drew their meals to be an average of 25% bigger when provided the larger of the two plates.

Our second hypothesis (meal norms) was that the participants would be influenced by normative conceptions about the percentage of the plate that should be covered by food. This hypothesis was not supported by the data for men and women combined. Overall meal sizes were bigger with larger plates, but percent of plate coverage was statistically different with 23 cm plates appearing on average 76% full and 28 cm plates appearing 61% full (Table 1). While more food was drawn on larger plates, the larger plates did not produce the appearance of a greater or equally sized meal when viewed in the context of how filled the plate was with food.

Our third hypothesis (meal composition) was that meal courses and food types would be differentially influenced by plate size. The hypothesis was supported. Drawings of individual courses covered a larger percentage of space on the 23 cm plates when compared to the 28 cm plates, with the largest food covering 6% more of the smaller plate (p < .001), the second largest food covering 6% more (p = .005), and the third largest food covering about 4% more (p < .001) (Table 1). While the smaller 23 cm plates were drawn to appear more full, the 28 cm plate food drawings were still bigger, with main courses drawn to be on average 12.5 cm2 or 34% bigger, the second course drawn to be 5.1 cm2 or 21% bigger, and third courses drawn to be 3.6 cm2 or 20% bigger. More than half of the overall size differences between plates was due to a greater size of the biggest food. When food types were compared between plate sizes (Table 1), three food types were drawn significantly bigger when given a larger plate: meat courses were 10.7 cm2 bigger (p < .001), grain courses were 6.6 cm2 bigger (p = .006) and vegetable courses were 6.9 cm2 bigger (p < .001).

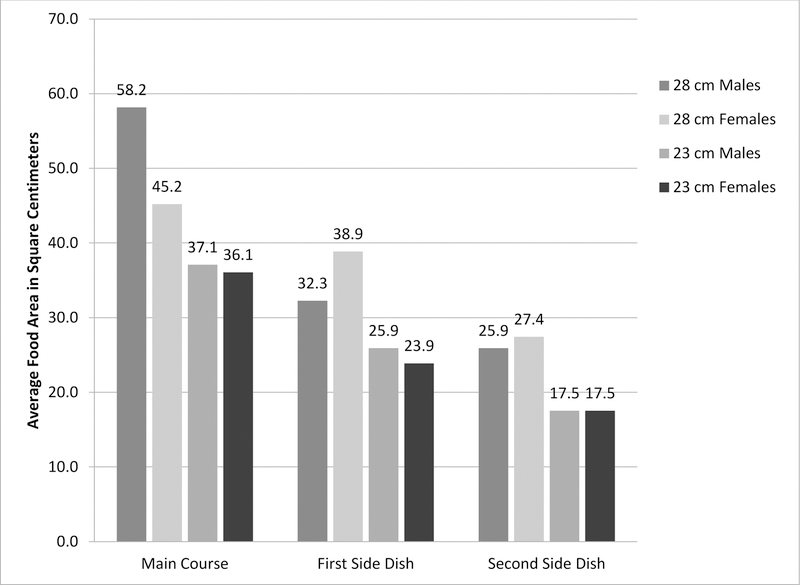

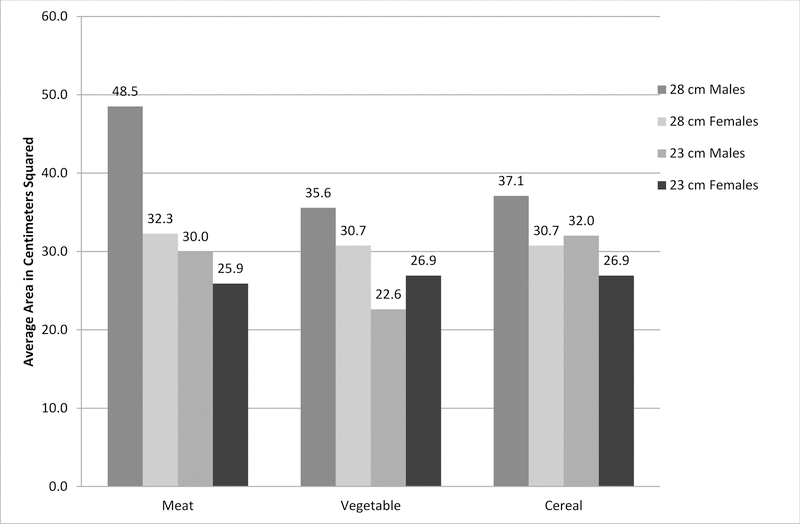

Our fourth hypothesis (sex moderation) was that the sex of the participant would moderate the influences of plate sensitivity and plate composition, with men responding to larger plates by drawing bigger portions than women drew. The hypothesis was partly supported. Men with larger plates drew meals that averaged about 34 cm2 bigger (p < .0001) and while men’s smaller plates were about 8% more full, this was not statistically significant (p = .13). Women with larger plates did not draw bigger overall meals after adjusting for multiple comparisons (p = .012), but the composition of the smaller plates appeared to be 20% more “full” (p < .001) when the women’s drawn meal was examined in the context of the size of the plate (Figure 1). Comparing sexes within the same plate size, men’s drawn dinners were 25.4 cm2 bigger than dinners of women when given a large 28 cm plate (p < .001) but there was no significant difference in size between sexes for a small 23 cm plate (p = .39). For the plate consistency hypothesis, men covered 16% more of their 28 cm plates with food than women did (p <.001), but men did not cover more of the smaller 23 cm plates than women did (p = .34). Analyses of food type by plate size and sex revealed significantly bigger men’s drawings of meat size than women’s drawings with 28 cm plates, but no significant differences between sexes for 23 cm plates (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Food Course Size by Plate Size and Gender.

Mean drawn area of foods, arranged from largest (main course) to smallest food (second side dish) on the plate, which the participants believed that they would be consuming for dinner that night.

Figure 2. Food Group Size by Plate Size and Gender.

Mean drawn area of foods, arranged by food groups (Meat, Vegetable, and Cereal), which the participants believed that they would be consuming for dinner that night.

Discussion

Overall, this study showed that plate size can influence conceptualizations of appropriate meal and portion sizes. Meals, food portions, and food types can be assessed with plate mapping in the absence of normative external cues about foods among adults living in communities. Participants with bigger plates drew meals significantly larger than their small plate counterparts. Sex appeared to play a role in influencing meal size and composition.

Our first hypothesis, that participants would be sensitive to the size of the plate and draw greater amounts of food on larger plates to reflect the available space, was supported by data about the average plate area coverage. We found the difference between larger and smaller plates in overall mean food size to be about 20.3 cm2, or the size of one large chicken egg. Depending on which food type created this difference, this could represent a substantial amount of extra calories if the food is a meat product (up to 300 calories) rather than a vegetable product (about 40 calories). This increase in size also represents a full serving of meat or a half-cup of vegetables with respect to fulfilling the recommendations put forth by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) [24]. This increase or decrease in portion size may have useful applications in clinical settings to encourage patients to consume slightly more or less food at each meal. Similar findings have been reported when observing the effects of portion size. Haynes et al. [17] found that participants provided with a portion size of food that was considered ‘normal’ rather than ‘smaller than normal’ consumed their food without compensating for its size. They also reported that there was a range of food sizes that could be considered ‘normal’ and that participants were much more sensitive to the ‘smaller than normal’ boundary than the ‘larger than normal’ one. Their explanation assists in understanding how larger plate sizes may have influenced participants to increase their food drawings without pushing them outside of their interpretations of normal portion size ranges.

Our second hypothesis, that meal norms would influence participants to represent similar proportions of their plates filled with food was only found to be supported by the data when sex was considered. Men appear to be grounded in the norms that a certain portion of the plate should be covered by food, while women appear to be more cognizant of the area of the food itself than the vessel upon which the food is served [5]. This may be partially explained by the Delboeuf Illusion, where an item surrounded by a larger circle may be perceived as smaller than an equally sized item surrounded by a circle that only barely is large enough to surround the item [25]. The rims of plates may provide a consumer with an inadvertent optical illusion, enticing them to increase portion sizes on large plate in order to compensate for their meal appearing insufficient within its context. This illusion, when paired with Haynes et al.’s [17] finding that portion sizes have ranges of normality rather than fixed sizes, provides a useful theory for how both plate size groups could have responded with such different food and meal sizes while both reporting that their drawings were accurate.

Our third hypothesis considered course size and food type size differences across plates. We found that the first three food courses were bigger in size on larger plates, with much of the difference in meal size coming from the biggest food on the plate increasing in size rather than the smaller sized foods becoming more equivalent to the larger item. This kept the drawn meal looking appropriate for what would be considered the western cultural ideals of a main and two side dishes [21] rather than drawing a meal that appears to be three main courses.

Our fourth hypothesis tested sex moderation and revealed that while both men and women drew bigger meals on larger plates, there were significant differences in the overall size, food type, and food course drawings between men and women. We found the difference between larger and small plates for overall size of food drawn by men to be more than twice as large as the difference found for women and often focused on different food groups. Men tended to draw far bigger meat portions than grain or vegetable portions when given a bigger plate, while women were more balanced across food types on different sized plates. Since about 60% of the plate size difference occurred for both sexes in what was already the biggest food, the caloric difference between average drawings could be as low as about 40 calories (female drawing more vegetables) and as high as about 400 calories (male drawing a larger steak). These findings suggest an asymmetrical sex response to plates as environmental influences, with men being more sensitive to plate size in their plate composition than were women.

There has been longstanding concern about the over-reliance of psychological research on samples of college students which may produce different findings than studies of adults in communities [26]. These findings about plate mapping in in this sample of community dwelling adults were similar to those found in college students [5]. Both studies found similar patterns in food coverage percentage, overall meal size, and individual food size when comparing the smaller plates and the larger plates, and plate coverage. These two studies also support the hypothesis that a majority of the difference in meal size between plates would be found in the biggest food. The present study examined plate drawing among adults, which were comparable with earlier studies of plate drawing among college students, supporting the external validity of plate mapping.

Implications and Applications

Plate mapping is an inexpensive and rapid method for collecting data about meals, portions, and foods, and can be used in conjunction with other types of food intake assessment. As individuals have been shown to be able to draw their real foods with a high degree of accuracy [6], plate mapping may also be useful for screening and prioritizing meal preference and food type importance at an individual level by offering insights about a person’s conceptions of meal size, food preferences, or food aversions. Recent studies estimating the caloric accuracy of two-dimensional plate drawings [27] and food photography [28, 29] show promise as both methods provide reasonable approximations of actual intake. Asking a participant to draw what they plan to eat or would like to eat for dinner, rather than offering them pre-created food item pictures or drawings, may also enhance the connection between dietary theory and practice for participants by offering them a personalized visual representation of their meal preferences and routines [30]. Plate mapping thus offers an additional and complementary method for assessing eating preferences to provide information about meal-related characteristics and how portion sizes can be influenced.

When nutrition researchers consider which processes may increase or decrease caloric intake, understanding meal composition is important for deciding if a protocol like changing plate size would be effective for everyone to the same degree. If changing plate size can influence portion servings [31], then knowing beforehand if a participant prefers higher calorie grains and meats or lower calorie vegetables and fruits as well as their interpretations of an appropriate meal size can help identify which nutrition interventions may provide the best results.

There are several limitations in this study. The volunteer sample included relatively few male participants, which limits generalizability to men and statistical power for analyzing differences between sexes. Additionally, the quasi-experimental research design involved only between-person comparisons, and should be replicated using stronger experimental designs. While preliminary analyses showing that stratification, i.e. controlling for household in a hierarchical model, revealed no significant differences between married/cohabiting and unmarried individuals with respect to the major study outcomes, similar meal planning behaviors might be expected and may have confounded the results [32]. We also only included in our study plates that were of a normal size that should have been familiar to sizes of plates that participants would have eaten on at home or in restaurants. Future research should include plates that are too large or too small for reasonable dinner expectations to examine how participants attempt to draw their meal estimates when the plate that does not fit within a normal range [17]. We also did not measure participants’ perceived differences in plate coverage, so further research should be done to determine if participants believe that the ‘fullness’ of the plate was an important factor in how much food they elected to draw upon their plates.

Conclusion

We observed that plate size was associated with the amount and proportions of food that participants portrayed they would be eating for dinner that night. Some environmental modifications require little additional effort from participants and can have an impact on dietary behaviors [33, 34, 35], and changing plate size may help change food intake. Easily integrated environmental changes such as plate size modification could be a useful method for modifying meal preferences and encouraging more appropriate eating behaviors in the home environment [30].

Individuals’ food consumption amounts, composition, and patterns can be influenced by many internal and external factors [36]. This study suggests that that while people can portray their dinner size and composition as a two dimensional drawing, these representations of meal size can be influenced by the size of the plate and are moderated by sex. Meal drawings on larger plates appeared emptier in the context of the plate, and different sized actual plates may influence participants to serve themselves more food or go back for second helpings of food. Our results suggest participants’ estimates of dinner size may be influenced by plate size. This plate size effect appears to be more powerful for males than females and may encourage an asymmetrical difference in men’s and women’s consumption from larger plates.

Highlights.

Bullet 1: This study uses a protocol called plate mapping, where people draw a meal on a plate

Bullet 2: Plate mapping examines how participants conceptualize meal and portion size

Bullet 3: Meal size sensitivity occurred as participants drew bigger meal areas on larger plates

Bullet 4: Meal composition sensitivity occurred as participants drew bigger portions on larger plates

Bullet 5: This study reports findings in a community setting that are similar to studies done in college populations

Acknowledgements:

We thank Bari Giller, Esther Kim, Eliza Lewine, Michelle Markovich, Jennifer St. Peter, and Marion Smith for assistance in data collection and coding, and Anthony Shreffler for statistical consultation and analysis.

Financial Support/Funding: Data collection for this project was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant 1RC1HD063370-01, and data analysis was supported by National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) grant T32DK007158.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations

Ethical Standards Disclosure: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Cornell University Institutional Review Board for Human Participants. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for Publication: There are no details, images, or videos relating to individual participants within this manuscript.

Availability of Data and material: We are willing to make this data available.

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests: None

References

- [1].Hollands GJ, Shemilt I, Marteau TM, Jebb SA, Lewis HB, Wei Y, Higgins J and Ogilvie D, “Portion, package, or tableware size for changing selection and consumption of food, alcohol and tobacco.,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [2].Fisher JO, Birch LL, Zhang J and Grusak MA, “External influences on children’s self-served portions at meals.,” International Journal of Obesity, vol. 37, pp. 954–960, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Peng M, Adam S, Hautus MJ, Shin M, Duizer L and Yan H, “Cultural differences in estimating fullness and intake as a function of plate size,” Appetite, vol. 117, pp. 197–202, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Raynor HA and Wing RR, “Package unit size and amount of food: do both influence intake?,” Obesity, vol. 15, no. 9, pp. 2311–2319, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sharp D and Sobal J, “Using plate mapping to examine sensitivity to plate size in food portions and meal composition among college students,” Appetite, vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 197–202, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sharp D, “Validating the plate mapping method: Comparing drawn foods and actual foods of university students in a cafeteria.,” Appetite, vol. 100, pp. 197–202, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Halverson KH and Meengs JS, “Using a smaller plate did not reduce energy intake at meals.,” Appetite, vol. 49, no. 3, pp. 652–660, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Shah M, Schroeder R, Winn W and Adams-Huet B, “A pilot study to investigate the effect of plate size on meal energy intake in normal weight and overweight/obese women.,” Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 612–615, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Koh J and Pliner P, “The effects of degree of acquaintance, plate size, and sharing on food intake.,” Appetite, vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 595–602, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ahn H, Han K, Kwon H and Min K, “The small rice bowl-based meal plan was effective at reducting dietary energy intake, body weight, and blood glucose levels in korean women with type 2 diebetes mellitus.,” Korean Diabetes Journal, vol. 34, no. 6, pp. 340–349, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].DiSantis K, Birch L, Davey A, Serrano E, Zhang J, Bruton Y and Fisher J, “Plate size and children’s appetite: Effects of larger dishware on self-served portions and intake,” Pediatrics, vol. 131, no. 5, pp. e1451–e1458, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Henreich J, Heine SJ and Norenzayan A, “The weirdest people in the world?,” Behavioral and Brain Sciences, vol. 33, pp. 61–135, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Werthmann J, Jamsen A and Roefs A, “Worry or craving? A selective review of evidence for food-related attention biases in obese individuals, eating-disorder patients, restrained eaters and healthy samples,” Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, vol. 74, no. 2, pp. 99–114, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wang E, Cakmak YO and Peng M, “Eating with eyes - Comparing eye movements and food choices between overweight and lean individuals in a real-life buffet setting,” Appetite, vol. 125, pp. 152–159, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Peterson R, “On the use of college students in social science research: insights from a second-order meta-analysis,” Journal of Consumer Research, vol. 28, pp. 450–461, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Cooper CA, McCord DM and Socha A, “Evaluating the college sophomore problem: the case of personality and politics,” Journal of Psychology, vol. 145, no. 1, pp. 23–37, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Haynes A, Hardman CA, Makin ADJ, Halford JC, Jebb SA and Robinson E, “Visual perceptions of portion size normality and intended food consumption: A norm range model,” Food Quality and Preference, vol. 72, pp. 77–85, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Emanuel AS, McCully SN, Gallagher KM and Udegraff JA, “Theory of Planned Behavior explains gender difference in fruit and vegetable consumption,” Appetite, vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 693–697, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rolls BJ, Federoff IC and Guthrie JF, “Gender differences in eating behavior and body weight regulation.,” Health Psychology, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 133–142, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wardle J, Haase AM, Steptoe A, Nillapun M, Jonwutiwes K and Bellisle F, “Gender differences in food choice: the contribution of health beliefs and dieting.,” Annals of Behavioral Medicine, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 107–116, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Douglas M, “Deciphering a meal.,” Daedalus, vol. 101, no. 1, pp. 61–81, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Pratt IS, Croager EJ and Rosenberg M, “The mathematical relationship between dishware size and portion size,” Appetite, vol. 58, no. 1, pp. 299–302, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Keselman HJ, Algina J, Kowalchuk RK and Wolfinger RD, “A comparison of recent approaches to the analysis of repeated measurements.,” British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 63–78, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [24].USDA, “Choose MyPlate.gov,” 11 September 2011. [Online]. Available: http://choosemyplate.gov.

- [25].Jaeger T and Lorden R, “Delboeuf Illusions: contour or size detector interactions?,” Perceptual and Motor Skills, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 376–378, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Sears DO, “College sophomores in the laboratory: influences of a narrow data base on social psychology’s view of human nature,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 51, no. 3, pp. 515–530, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Steyn N, Senekal M, Norris S, Whati L, Mackeown J and Nel J, “How well do adolescents determine portion sizes of foods and beverages,” Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 15, pp. 35–42, 2006. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Harris-Fry H, Paudel P, Karn M, Mishra N, Thakur J, Paudel V, Harrisson T, Shrestha B, Manandhar DS, Costello A, Cortina-Borja M and Saville N, “Development and validation of a photographic food atlas for portion size assessment in the southern plains of Nepal,” Public Health Nutrition, vol. 19, no. 14, pp. 2495–2507, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Martin C, Correa J, Han H, Allen HR, Rood JC, Champagne CM, Gunturk BK and Bray GA, “Validity of the Remote Food Photography Method (RFPM) for estimating energy and nutrient intake in near real-time,” Obesity, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 891–899, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Camelon KM, Hadell K, Jamsen PT, Ketonen KJ, Kohtamaki HM, Makimatilla S, Tormala ML and Valve RH, “The Plate Model: a visual method of teaching meal planning. DAIS Project Group. Diabetes Atherosclerosis Intervention Study,” Journal American Dietary Association, vol. 98, no. 10, pp. 1155–1158, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Peng M, “How does plate size affect estimated satiation and intake for individuals in normal-weight and overweight groups?,” Obesity Science & Practice, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 282–288, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bove C, Sobal J and Rauschenbach B, “Food choices among newly married couples: Convergence, conflict, individualism, and projects.,” Appetite, vol. 40, pp. 25–41, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cowan JA and Devine CM, “Diet and body composition outcomes of an environmental and educational intervention among men in treatment for substance addiction,” Journal of Nutritional Education and Behavior, vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 154–158, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Korne D. F. d., Malhotra R, Lim WY, Ong C, Sharma A, Tan TK, Tan TC, Ng KC and Ostbye T, “Effects of a portion design plate on food group guideline adherence among hospital staff.,” Journal of Nutritional Science, vol. e, no. 60, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Engbers LH, Poppel M. N. v., Chin A and Mechelen W. v., “Worksite health promotion programs with environmental changes: a systematic review,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 61–70, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wadhera D and Capaldi-Phillips ED, “A review of visual cues associated with food on food acceptance and consumption.,” Eating Behaviors, vol. 15, pp. 132–143, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Robinson E, Nolan S, Tubur-Smith C, Boyland EJ, Harrold JA, Hardman CA and Halford JC, “Will smaller plates lead to smaller waists? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect that experimental manipulation of dishware has on energy consumption.,” Obesity Review, vol. 15, no. 10, pp. 812–821, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]