There is a long-standing belief that interferon (IFN)-inducible human myxovirus resistance protein A (MxA), which displays antiviral activity against several RNA and DNA viruses, associates with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus. We provide data to correct this misinterpretation and further report that MxA forms membraneless metastable (shape-changing) condensates in the cytoplasm consisting of variably sized spherical or irregular bodies, filaments, and even a reticulum. Remarkably, MxA condensates showed the unique property of rapid (within 1 to 3 min) reversible disassembly and reassembly in intact cells exposed sequentially to hypotonic and isotonic conditions. Moreover, GFP-MxA condensates included the VSV nucleocapsid (N) protein, a protein previously shown to form liquid-like condensates. Since intracellular edema and ionic changes are hallmarks of cytopathic effects of a viral infection, the tonicity-driven regulation of MxA condensates may reflect a mechanism for modulation of MxA function during viral infection.

KEYWORDS: interferons, myxovirus resistance protein A (MxA), biomolecular condensates, membraneless cytoplasmic organelles, regulation by tonicity, antiviral granules, hypotonic disassembly, isotonic reassembly, vesicular stomatitis virus

ABSTRACT

Phase-separated biomolecular condensates of proteins and nucleic acids form functional membrane-less organelles (e.g., stress granules and P-bodies) in the mammalian cell cytoplasm and nucleus. In contrast to the long-standing belief that interferon (IFN)-inducible human myxovirus resistance protein A (MxA) associated with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus, we report that MxA formed membraneless metastable (shape-changing) condensates in the cytoplasm. In our studies, we used the same cell lines and methods as those used by previous investigators but concluded that wild-type MxA formed variably sized spherical or irregular bodies, filaments, and even a reticulum distinct from that of ER/Golgi membranes. Moreover, in Huh7 cells, MxA structures associated with a novel cytoplasmic reticular meshwork of intermediate filaments. In live-cell assays, 1,6-hexanediol treatment led to rapid disassembly of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-MxA structures; FRAP revealed a relative stiffness with a mobile fraction of 0.24 ± 0.02 within condensates, consistent with a higher-order MxA network structure. Remarkably, in intact cells, GFP-MxA condensates reversibly disassembled/reassembled within minutes of sequential decrease/increase, respectively, in tonicity of extracellular medium, even in low-salt buffers adjusted only with sucrose. Condensates formed from IFN-α-induced endogenous MxA also displayed tonicity-driven disassembly/reassembly. In vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV)-infected Huh7 cells, the nucleocapsid (N) protein, which participates in forming phase-separated viral structures, associated with spherical GFP-MxA condensates in cells showing an antiviral effect. These observations prompt comparisons with the extensive literature on interactions between viruses and stress granules/P-bodies. Overall, the new data correct a long-standing misinterpretation in the MxA literature and provide evidence for membraneless MxA biomolecular condensates in the uninfected cell cytoplasm.

IMPORTANCE There is a long-standing belief that interferon (IFN)-inducible human myxovirus resistance protein A (MxA), which displays antiviral activity against several RNA and DNA viruses, associates with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus. We provide data to correct this misinterpretation and further report that MxA forms membraneless metastable (shape-changing) condensates in the cytoplasm consisting of variably sized spherical or irregular bodies, filaments, and even a reticulum. Remarkably, MxA condensates showed the unique property of rapid (within 1 to 3 min) reversible disassembly and reassembly in intact cells exposed sequentially to hypotonic and isotonic conditions. Moreover, GFP-MxA condensates included the VSV nucleocapsid (N) protein, a protein previously shown to form liquid-like condensates. Since intracellular edema and ionic changes are hallmarks of cytopathic effects of a viral infection, the tonicity-driven regulation of MxA condensates may reflect a mechanism for modulation of MxA function during viral infection.

INTRODUCTION

There is now a growing realization that, in addition to various membrane-bound subcellular compartments, the eukaryotic cell contains organized membrane-less biomolecular condensates (also called supramolecular assemblies) of proteins and nucleic acids which form functional organelles (1–5). Examples include the nucleolus, nuclear speckles, P bodies, stress granules, and several more recent discoveries, such as condensates of synapsin, of the DNA sensor protein cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) in the cytoplasm and of transcription-associated condensates in the nucleus (1–10). Overall, these condensates have liquid-like internal properties and are metastable, changing to a gel or to filaments commensurate with the cytoplasmic environment (temperature, ionic conditions, physical deformation, or cytoplasmic crowding), and incorporate additional proteins, RNA, or DNA molecules or posttranslational modifications (1–13). Indeed, DNA and RNA molecules specifically participate in the assembly of such cytoplasmic and nuclear condensates and in their function (1–13).

There is also extensive literature on the changes observed in stress granules and P-bodies in diverse virus-infected cells (14–18). In terms of viral replication, stress granules and P-bodies can enhance or inhibit replication of specific viruses depending upon the experimental system (14–18). Indeed, some investigators have used the term “antiviral granule” (16) to emphasize specific protein components in these condensates as antiviral effectors (14–18). In parallel with the above-described insights (14–18), it has been recognized that replication of negative-strand RNA viruses (e.g., vesicular stomatitis [VSV], rabies, Ebola, measles, and influenza A viruses) occurs in cytoplasmic phase-separated condensates typically involving the viral nucleocapsid (N) protein with or without additional viral proteins (19–24). In the present report, we highlight the unexpected discovery that the human interferon (IFN)-inducible myxovirus resistance protein A (MxA), which displays antiviral activity against several RNA and DNA viruses (25–31), exists in the cytoplasm in membrane-less metastable condensates, which prompt comparisons with antiviral granules.

Human MxA is a cytoplasmic 70-kDa dynamin-family large GTPase which is induced in cells exposed to type I and III IFNs (25–31). There is extensive literature on the mechanisms of the broad-spectrum antiviral effects of MxA (25–31). These mechanisms include inhibition of viral transcription and translation and inhibition of the nuclear import of viral nucleic acids (25–31). The antiviral activity of MxA requires the GTPase activity and the ability to form dimers and higher-order oligomers (25–31). MxA has an overall structure consisting of a globular GTPase domain (G domain), a hinge region (BSE region), and a stalk consisting of 4 extended alpha-helices (25–31). Dimerization has been attributed to an interface in the G domain, especially the D250 residue, as well as the stalk region (29, 31). In cell-free studies, recombinant MxA has been observed to dimerize, tetramerize, and self-oligomerize into rods (∼50 nm length) and rings (∼36 nm diameter) based upon temperature, ionic conditions, and GTPase activity (29–34). Additionally, in cell-free studies, it has been shown that MxA can cause membrane tubulation (32, 33), but whether MxA associates with intracellular membranes in the intact cells is not clear.

Previous investigators reported the occurrence of wild-type MxA in the cytoplasm of mammalian cells in puncta and in various irregularly shaped structures (30–38). GTPase-null mutants which lacked antiviral activity also generated such cytoplasmic structures. Mutational studies revealed that the D250N mutant of MxA, a mutation localized to the dimerization interface, remained exclusively dispersed in the cytoplasm and also lacked antiviral activity (31). However, many other mutants, even GTPase null mutants lacking antiviral activity, formed significant cytoplasmic structures (31). A prevalent interpretation of studies over the last 17 years has been to infer that MxA associated with a subcompartment of the smooth endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and the Golgi apparatus (25–38). However, none of the previous studies (32, 37) characterized MxA localization using authentic markers of the ER, such as known structural or luminal ER proteins, or of the Golgi apparatus. We note that in 2002, Kochs et al. (35) stated “The ultrastructural analysis revealed no obvious connection of the MxA/N complexes [N was nucleocapsid protein of La Crosse virus] to other subcellular structures. A possible association with intracellular membranes was excluded by immunofluorescence analysis, using structure-specific markers for the endoplasmic reticulum or the pre-, cis-, and trans-Golgi compartments (data not shown). We conclude that the MxA/N filamentous complexes developed independently from other cellular structures and localized preferentially to the perinuclear area in the cytoplasm.” In this 2002 report, Kochs et al. (35) used thin-section electron microscopy (EM) and immuno-EM methods to observe that these MxA/N protein complexes were membrane-less (see Fig. 2 in reference 35), yet the same research group claimed in 2006 that MxA associated with membranes of the ER and Golgi apparatus (37).

In their studies of MxA in Hep3B and HeLa cells, Accola et al. (32) in 2002 stated “After exploring markers for multiple organelles and cytoskeletal elements, we did not observe a significant colocalization [of MxA] with microtubules, actin, rough ER, endosomes, or mitochondria [these markers were not enumerated]. We did observe, however, that a large portion of MxA colocalized with one organelle marker, the autocrine motility factor receptor” (AMF-R). However, we note that AMF-R is not an accepted marker for the ER (39–42). Moreover, the colocalization data presented in Fig. 4 of reference 32 were unclear. In 2006, Stertz et al., working with Huh7 and Vero cells (37), claimed to have used antibodies to syntaxin-17 and to Hook3 as markers for the ER and Golgi membrane, respectively, and to have colocalized MxA with those markers. Again, these were nonstandard aspecific markers for those organelles (39–42). Nevertheless, today, the Accola et al. (32) and Stertz et al. (37) citations have been used extensively in the MxA field to support the claim that MxA associated with a subcompartment of the smooth ER and with the Golgi membrane (see references 27–31 for examples). The data in the present report indicate that inferences in Accola et al. (32) and Stertz et al. (37) articles were inadequate and that, in contrast, the description of MxA structures from 2002 by Kochs et al. (35) as membraneless structures in the cytoplasm not associated with any organelles or membranes was correct.

The various imaging studies in the literature showed marked diversity of size and shape of cytoplasmic MxA structures (30–37). We were able to replicate this variability of MxA structure in our experiments (43, 44), and in this report we present an unexpected aspect of the cell biology of MxA structures in the cytoplasm. The present data reveal that cytoplasmic MxA structures, even in uninfected cells, comprised membraneless condensates exhibiting marked metastability (shape-changing) and rapid and reversible phase transitions in response to changing tonicity of the culture medium. In green fluorescent protein (GFP)-MxA-expressing VSV-infected cells, the viral nucleocapsid (N) protein associated with GFP-MxA condensates concomitant with development of an antiviral phenotype.

(This article was submitted to an online preprint archive [45].)

RESULTS

Marked variations in shapes and sizes of cytoplasmic MxA structures.

In the present study, we specifically used many of the same cell lines (HEK293T, Cos7, and Huh7) and MxA expression protocols used by previous investigators in the MxA field (25–37). Because the data reported in 2006 by Stertz et al. (37) showed the most persuasive hemagglutinin (HA)-MxA reticulum-like images in Huh7 cells (see Fig. 5D in reference 37), we specifically carried out most of our studies in Huh7 cells using the HA-MxA expression construct obtained from Stertz et al. (37) or following IFN-α treatment of Huh7 cells using the protocol of Stertz et al. (37). The GFP-MxA expression construct used in the present study was developed by Pavlovic and colleagues and has been shown to elicit an antiviral effect (46, 47).

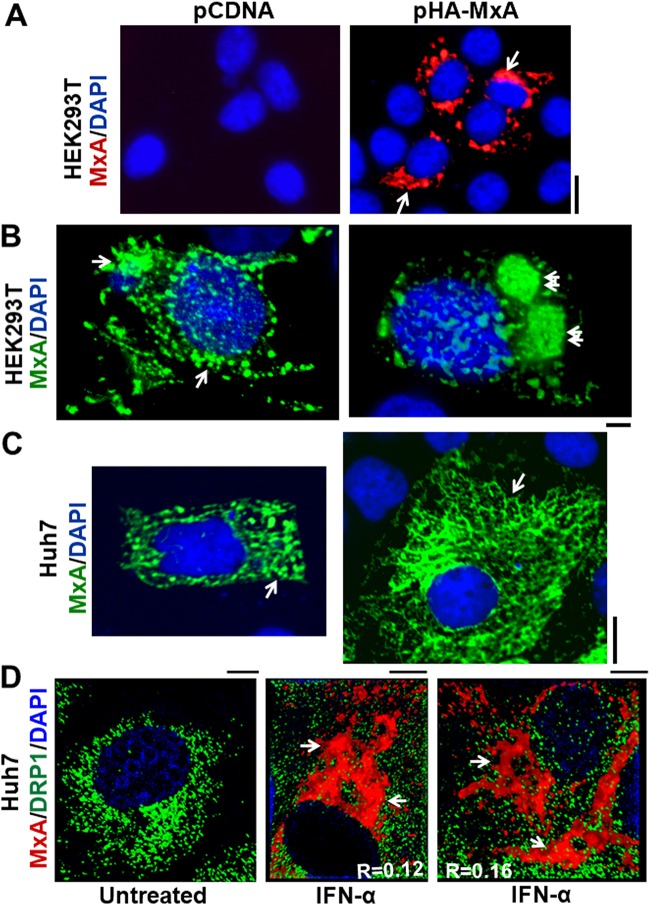

The imaging data summarized in Fig. 1 show that in uninfected HEK293T and Huh7 cells, MxA associated with variably sized spherical and irregularly shaped structures (Fig. 1A to C; size range, 200 to 2,000 nm) and large floret-like structures (arrows in Fig. 1B; size range, 10 to 20 μm) and showed a specific crisscross reticular pattern unique to Huh7 cells (Fig. 1C, right image, arrow). Endogenous MxA induced in Huh7 cells exposed to IFN-α also formed an irregular cytoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 1D). This MxA reticulum was distinct from the punctate distribution of DLP1/DRP1, another large dynamin-family GTPase which associates with mitochondria at fission sites (Fig. 1D) (48).

FIG 1.

Variation in MxA-positive cytoplasmic structures in different cells. Cultures of the indicated cells grown in 35-mm plates or 6-well plates were transiently transfected with pcDNA or the pHA-MxA expression vector (the same as that used by Stertz et al. [37]), fixed 1 day later, and permeabilized using a digitonin-containing buffer, and the distribution of MxA was evaluated using an anti-HA MAb or an anti-MxA rabbit PAb and immunofluorescence methods. (A) MxA structures in HEK 293T cells imaged using a 40× water immersion objective (scale bar, 20 μm). (B) MxA structures in HEK293T cells imaged using a 100× oil immersion objective (scale bar, 10 μm). Arrows point to large compact tubuloreticular MxA-positive structures, as observed in 25 to 35% of transfected cells. (C) MxA structures in Huh7 cells imaged using a 40× water immersion objective (scale bar, 10 μm) showing variably sized bodies (left image) and larger reticular formations in the cytoplasm, as observed in 25 to 35% of transfected cells in the cytoplasm (right image, arrow) (scale bar, 10 μm). (D) Huh7 cells were exposed to IFN-α2a (3,000 IU/ml) for 2 days or left untreated and then fixed and immunostained for endogenous MxA (in red) and endogenous DRP1 (in green) (scale bar, 5 μm).

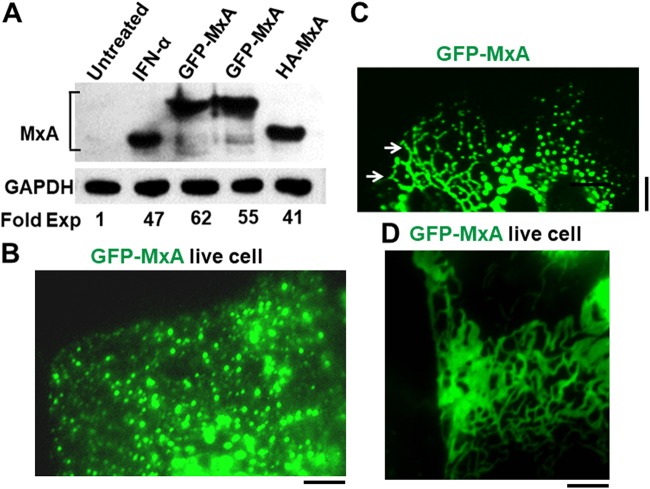

The variation in MxA structures was independent of the protein tag used. Both HA- and GFP-tagged wild-type MxA displayed the same heterogeneous structures with complete colocalization of both tagged MxA species in these structures (Pearson’s R = 0.95; P. B. Sehgal, unpublished data). Critically, the use of GFP-tagged MxA allowed for studies in live cells, including in time-lapse imaging experiments, in correlated fluorescence/light and electron microscopy (CLEM), and in analyses of fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP). The Western blot analyses shown in Fig. 2A confirmed the ∼50-fold stimulation of MxA expression by IFN-α in Huh7 cells. Moreover, there were comparable levels of increased expression of GFP-MxA and HA-MxA in these cells upon transient transfection using the previously developed MxA vectors (37, 46, 47) (Fig. 2A). In Huh7 cells, GFP-MxA formed variably sized spherical structures (Fig. 2B) that showed local movement (also see Fig. 6A and Movie S1 in the supplemental material), alignment of these along a crisscross pattern (Fig. 2C), as well as formation of an intricate filamentous reticular meshwork (Fig. 2D).

FIG 2.

Comparison of IFN-α-induced endogenous MxA expression with that from exogenous vectors and variation in GFP-MxA structures formed in Huh7 cells. (A) Western blot analyses showing comparable levels of MxA expression in Huh7 cells in 35-mm plates exposed to IFN-α (2,000 IU/ml for 2 days) or following transient transfection with 1 μg/plate of the GFP-MxA (in duplicate) and HA-MxA expression vectors. Protein-matched aliquots of whole-cell extracts were Western blotted and probed for MxA using a rabbit PAb or for GAPDH using a rabbit MAb. Fold increase in MxA is expressed in terms of the untreated control. (B to D) Huh7 cells in 35-mm plates were transfected with the pGFP-MxA expression vector and the cells imaged before (B and D) or after (C) fixation. (B) Live-cell wide-field 100× oil imaging of the periphery of one cell with GFP-MxA structures of variable size within the same cell 1 day after transfection; smaller-sized MxA bodies were at the cell periphery with larger structures closer to the cell center. (C) Portions of three adjacent cells 1 day after transfection showing GFP-MxA associated with structures in different configurations, including a reticular pattern of intersecting lines (arrows; left-most cell). Scale bars in panels B and C, 10 μm. (D) Open meshwork GFP-MxA reticulum in live Huh7 cells 2 days after transfection, imaged by placing a coverslip on the cells followed by time-lapse imaging using a 100× oil objective. Scale bar, 5 μm.

FIG 6.

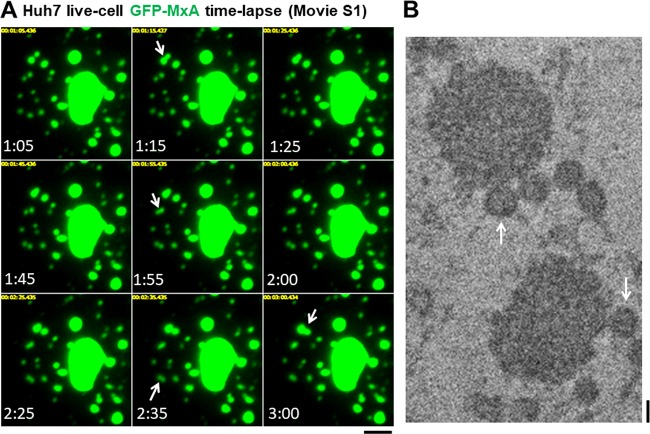

Homotypic association of GFP-MxA bodies to yield larger structures. (A) Huh7 cells in 35-mm plates were transfected with the pGFP-MxA expression vector. Two days later the live cells, under a coverslip with a drop of PBS, were imaged using a 100× oil immersion objective and time-lapse data collection (images were collected from the periphery of different cells at 5-s intervals for 1 to 3 min). Shown are images from one time-lapse sequence lasting approximately 3 min (Movie S1) showing four homotypic association events (arrows). The data also show persistence of the combined structure. Scale bar, 5 μm. (B) Thin-section EM images from the CLEM data, as shown in Fig. 4, which highlight the homotypic fusion event between small GFP-MxA bodies (arrows) with larger MxA structures, all of which lack an external limiting membrane. Scale bar, 200 nm.

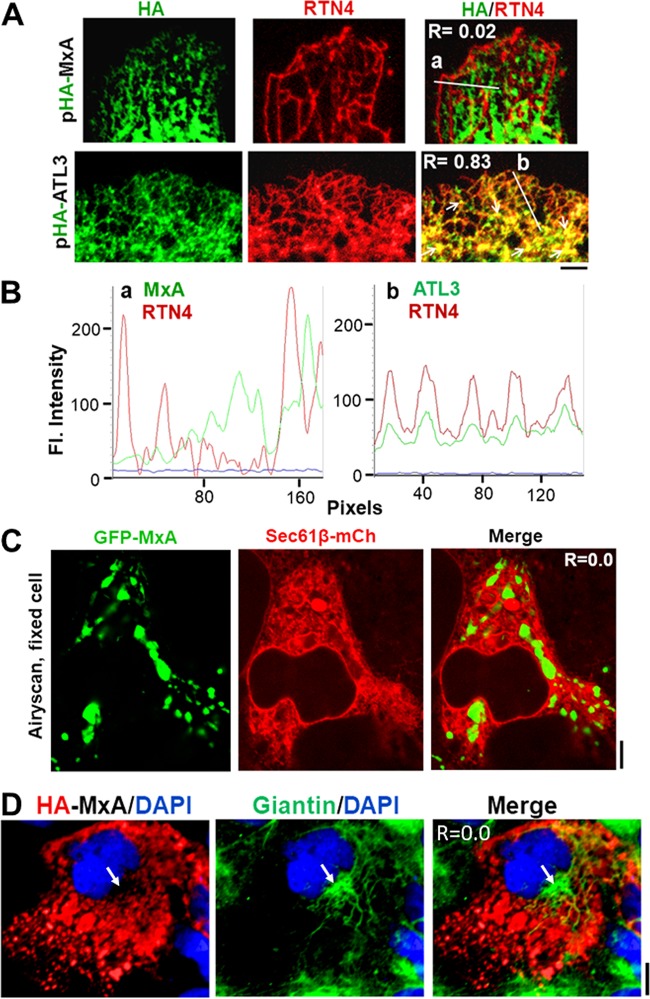

We developed a strategy to investigate the colocalization of HA-MxA with endogenous reticulon-4 (a structural protein residing in ER tubules; i.e., in smooth ER [39–42]) as an ER marker and of HA-atlastin-3 (HA-ATL3; an ER-resident GTPase) as a positive control using the same antibodies for both ATL3 and MxA sides of the analysis. Thus, we transiently transfected the pHA-MxA and pHA-ATL3 expression vectors into Huh7 cells and fixed them 1 day later, using the same primary and secondary antibodies sequentially for the HA-MxA and HA-ATL3 plates. It is clear from the data shown in Fig. 3A, lower row, and the line scan in Fig. 3Bb that there was considerable overlap between RTN4 and HA-ATL3 as a positive control (Pearson’s R = 0.83). In contrast, using the same immunological reagents, Fig. 3A, top row, and line scans in Fig. 3Ba show that MxA structures did not colocalize with the smooth ER tubules (Pearson’s R = 0.02).

FIG 3.

MxA structures were distinct from smooth endoplasmic reticulum tubules and the Golgi apparatus. (A and B) Huh7 cells were transfected with vectors for HA-tagged MxA or HA-tagged ATL3 as indicated, the cultures (in 35-mm plates) were fixed 1 day later, and the distribution of the HA tag and of RTN4 was sequentially evaluated using the mouse anti-HA MAb and then a goat anti-RTN4 PAb. Images were collected after placing a drop of PBS in each culture, overlaying it with a coverslip, and using a 100× oil immersion objective. In panel A, high-magnification imaging confirmed that HA-MxA did not colocalize with RTN4-positive tubules, while HA-ATL3 was colocalized with the RTN4-positive ER (both ATL3 and RTN4 are known ER-resident proteins, and peripheral ER tubules represent the smooth ER subcompartment [34–37]). Scale bar, 5 μm. Thin arrows point to three-way junctions that were variably positive for ATL3-HA and RTN4. White lines in the respective merged images in panel A show regions depicted in the line scans in panel B (subpanels a and b). (C) Huh7 cells in 35-mm plates were transiently cotransfected with the vectors for GFP-MxA and mCh-Sec61β (a subunit of the ER-resident translocon assembly [39–42]), fixed 2 days later, and evaluated for colocalization of the respective proteins using a high-resolution Zeiss confocal Airyscan microscopy system. Scale bar, 5 μm. (D) Huh7 cells in 35-mm plates were transiently transfected with the vector for HA-MxA, fixed 2 days later, and evaluated for colocalization of HA-MxA structures (probed using anti-HA mouse MAb) with the Golgi tether giantin (probed using anti-giantin rabbit PAb). Scale bar, 10 μm. R values in the respective merged images in panels A, C, and D correspond to Pearson’s correlation coefficient R with Costes’ automatic thresholding.

In the experiment shown in Fig. 3C, we avoided antibody reagents altogether and compared colocalization of GFP-MxA with that of the ER marker Sec61β-mCh (39–42, 49) using high-resolution Airyscan 880 confocal imaging. The data depicted in Fig. 3C show that GFP-MxA structures were separate from Sec61β (Pearson’s R = 0.0). To test whether there might be any overlap between MxA structures and the Golgi apparatus, we investigated the colocalization of transiently expressed HA-MxA (using anti-HA monoclonal antibody [MAb]) with that of the traditional Golgi tether giantin (using an anti-giantin polyclonal antibody [PAb]). The data depicted in Fig. 3D show a clear separation between HA-MxA and giantin in the Golgi region (Pearson’s R = 0.0). Additional comparisons included endogenous CLIMP63 (an ER marker) as well as mCh-CLIMP63 compared with HA-MxA-, GFP-MxA-, and IFN-α-induced endogenous MxA; GFP-MxA and RTN4-mCh (ER structural protein) in live Cos7 and Huh7 cells; GFP-MxA with mCh-KDEL (a marker for ER lumen); and GFP-MxA with Sec61β-mCh in live cells at high resolution (45 and P. B. Sehgal, H. Yuan, and D. Davis, unpublished data). Moreover, in contrast to the observations reported by Stertz et al. (37), we did not observe any colocalization between MxA structures and syntaxin-17 (P. B. Sehgal, unpublished). Taken together, our data do not show significant localization of MxA to any portion of the ER or Golgi apparatus.

Cytoplasmic GFP-MxA structures comprised membraneless condensates even in uninfected cells.

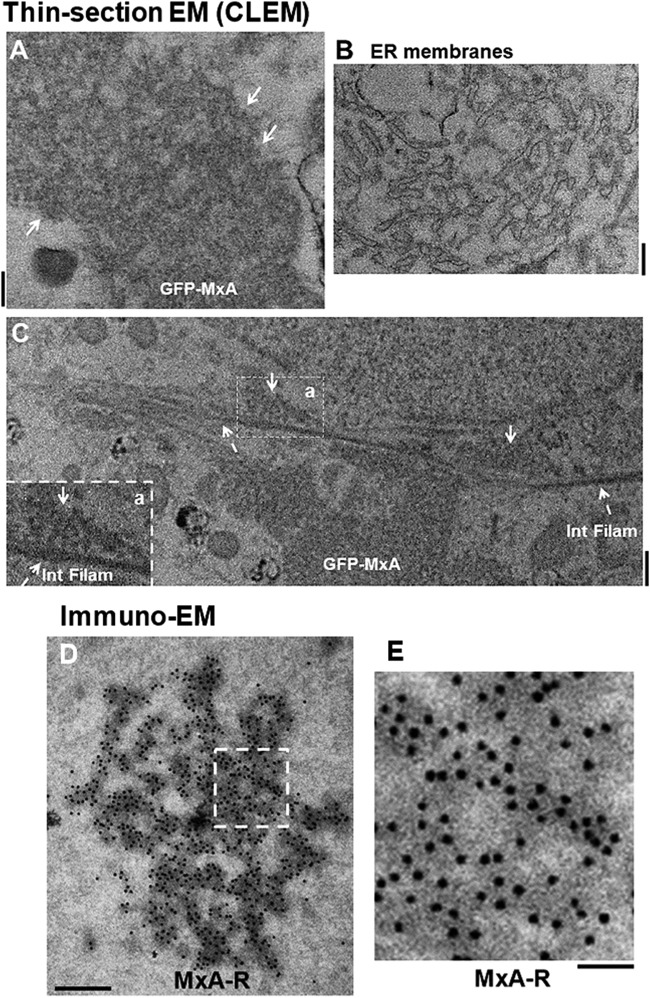

The cytoplasmic GFP-MxA structures were characterized using CLEM (50, 51). Figure 4A shows that the GFP-MxA structure consisted of electron-dense irregular circular and reticular structures without an external limiting membrane. Similarly, Fig. 4C shows multiple membrane-less condensates of GFP-MxA arranged alongside cytoskeletal elements. As a control, Fig. 4B illustrates clear membrane-containing ER in images derived from cells on the same thin section as that shown in Fig. 4A and C. Single-label immuno-EM studies confirmed the association of MxA with variably sized small condensates as well as larger heterogeneous reticular structures (Fig. 4D and E). Moreover, double-label immuno-EM studies confirmed that the variably shaped MxA condensates were devoid of RTN4 (P. B. Sehgal, unpublished). Thus, the data summarized in Fig. 3 and 4 showed that the MxA structures were membraneless and also distinct from the ER and Golgi apparatus.

FIG 4.

Thin-section EM of GFP-MxA structures in Huh7 cells carried out using a CLEM protocol and immuno-EM of MxA reticulum. (A to C) Huh7 cells plated sparsely in 35-mm MatTek gridded coverslip plates were transiently cotransfected with pGFP-MxA. Two days later the cultures were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h at 4°C. Confocal imaging was carried out using a tiling protocol to identify the location of specific cells with GFP-MxA structures on the marked grid. The cultures were then further fixed and embedded, and the previously identified grid locations were used for serial thin-section EM. The tiled light microscopy data were correlated with the tiled EM data to identify the ultrastructure of the GFP-fluorescent structures per the correlated light and electron microscopy (CLEM) procedure. (A) Thin-section EM image of GFP-MxA structures (arrows). (B) Thin-section EM image of a portion of a cell in the same section as that shown in panel A imaged at the same time, verifying the ability to detect ER membranes in this experiment. (C) Thin-section EM showing GFP-MxA structures (arrows) aligned along intermediate filaments (Int Filam; broken arrows). A higher magnification of inset a in panel C is shown in the lower left corner. Scale bars in panels A to C, 200 nm. (D and E) HA-MxA-expressing HEK293T cells (as shown in Fig. 1A) were prepared for immuno-EM analyses of MxA-positive structures using rabbit PAb to MxA and 15-nm protein A-gold particles as the secondary label. Panel D shows an example of MxA-reticulum (MxA-R), while panel E shows the boxed inset in panel D at a higher magnification. Scale bars, 500 nm (D) and 200 nm (E).

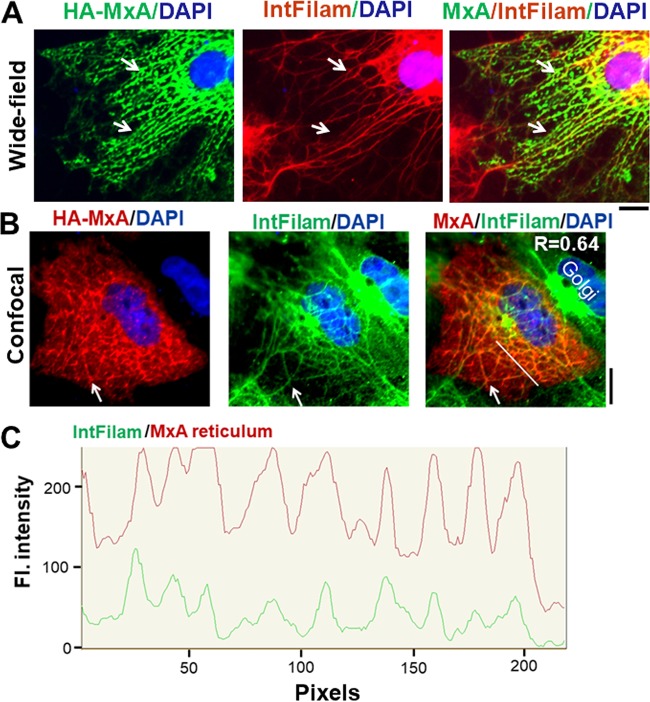

The cytoskeletal elements in Huh7 cells which provided an apparent scaffold for MxA condensates (as illustrated in Fig. 2C and 4C) were identified to be a meshwork of intermediate filaments unique to Huh7 cells. In order to provide a direct comparison with the HA-MxA meshwork imaging data shown in Fig. 5D of Stertz et al. (37), Fig. 5A and B show the cytoplasmic reticulum formed by HA-MxA structures in Huh7 cells. In studies evaluating the possible association of MxA with the Golgi apparatus (as in Fig. 3D), we carried out immunofluorescence studies in Huh7 cells for the Golgi markers GM130 and giantin. As expected, all of the GM130 was observed to be Golgi associated in all cells in the culture, and approximately half the cells in a culture showed the presence of giantin almost exclusively in the Golgi apparatus (as shown in Fig. 3D). However, in an unusual finding, we discovered that the cytoplasm of approximately half the cells in an Huh7 culture contained a unique meshwork of giantin-positive intermediate filaments (Fig. 5A and B, middle); these filaments were confirmed to be vimentin positive (P. B. Sehgal, unpublished). Importantly, the data depicted in Fig. 5A and B show the association of HA-MxA structures with these intermediate filaments. Figure 5C is a scan of the red and green pixels along the white line in the merged image in Fig. 5B and shows the correspondence between HA-MxA structures and intermediate filaments (Pearson’s R = 0.64). However, the data shown in Fig. 3D and Fig. 4C compared with those shown in Fig. 5A and B suggest that association between HA-MxA structures and an intermediate filament meshwork is not obligatory for the formation of cytoplasmic MxA structures.

FIG 5.

Association of HA-MxA structures with a cytoplasmic intermediate filament meshwork in Huh7 cells. Cultures of Huh7 cells were transiently transfected with the HA-MxA expression vector, and the localization of HA-MxA structures as well as the giantin-based intermediate filament meshwork unique to Huh7 cells (white arrows) was evaluated 2 days later by immunofluorescence assays. Panels A and B show two independent experiments using different microscopy methods (wide-field or confocal) in which the respective anti-HA MAb (to label HA-MxA) and anti-giantin PAb were displayed using different batches of respective Alexa Fluor-488 (green) or Alexa Fluor-594 (red) secondary antibodies. (C) Line scan in red and green of the white line in the triple merged image in panel B. Scale bars, 10 μm. R value in the merged image in panel B corresponds to Pearson’s correlation coefficient R with Costes’ automatic thresholding.

GFP-MxA condensates were metastable and heterogeneous.

The GFP-MxA structures were dynamic and changed shape. Live-cell time-lapse imaging revealed that GFP-MxA condensates displayed homotypic fusion. Figure 6A and Movie S1 show four fusion events within approximately 2 min in the peripheral cytoplasm of a GFP-MxA-expressing cell. Fig. 6B shows a thin-section EM image of a GFP-MxA-expressing cell (from the CLEM experiment shown in Fig. 4) illustrating small condensates in the vicinity of larger structures, suggestive of an impending fusion event (compare Fig. 6B with A and Movie S1).

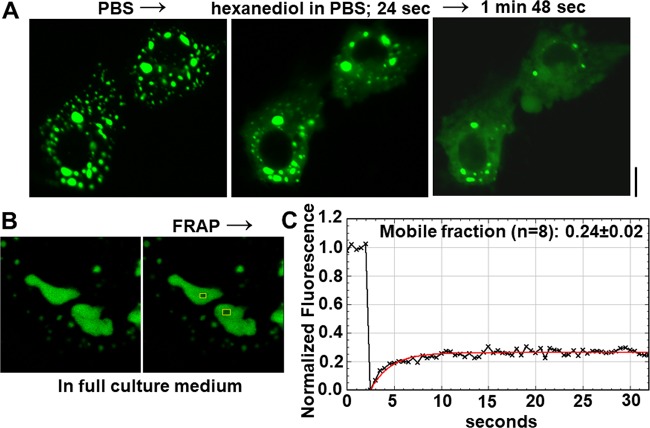

The liquid-like nature of the interior of membraneless condensates is often tested by their rapid disassembly upon exposure of cells to the plasma membrane-permeable reagent 1,6-hexanediol and by FRAP (3, 11, 12). Figure 7A shows data from an experiment in which hexanediol rapidly disassembled GFP-MxA condensates within 1 to 2 min. The FRAP analyses depicted in Fig. 7B and C show that the interior of GFP-MxA condensates comprised a mobile fraction of only 0.24 (compared to ∼0.70 for cytoplasmic GFP-STAT3), indicating significant stiffness in MxA condensate structure. This stiffness is consistent with an understanding of MxA oligomers as higher-order disk-like structures that assemble into networked “machines” with GTP hydrolysis instigating molecular movement (see Fig. 1 in reference 28) (30, 34, 52–54).

FIG 7.

Test of liquid-like properties of GFP-MxA condensates. (A) Hexanediol rapidly disassembled GFP-MxA condensates. Huh7 cells expressing GFP-MxA condensates were first imaged in PBS and then exposed to PBS containing 1,6-hexanediol (5%) and imaged 24 s and 108 s later. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B and C) FRAP analyses of replicate (n =8) internal regions of GFP-MxA condensates as summarized in Materials and Methods. (B) Location of two of the bleached spots evaluated. (C) Normalized bleaching and recovery plot for one of the spots in panel B. Overall (n = 8), the mobile fraction was 0.24 ± 0.02 and t1/2 was 2.37 ± 0.35 s (means ± standard errors [SE]). Controls for normalization included unbleached spots in each image, as well as background recording away from the GFP-MxA condensate. As a positive control for mobility, Huh7 cells expressing GFP-STAT3 in the cytoplasm showed a mobile fraction of 0.70 (12, 70).

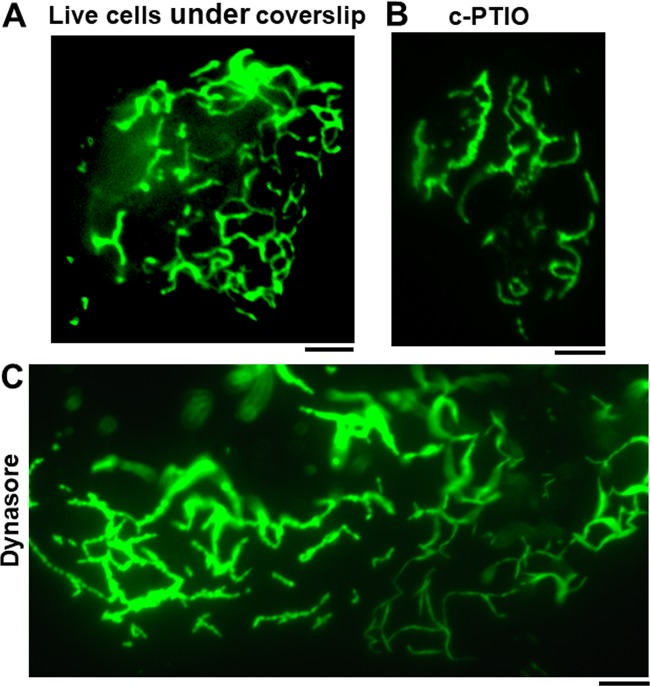

Indeed, shape changing (“metastability”) is a common feature of membraneless condensates in the cytoplasm (1–10). When cells expressing the large GFP-MxA condensates were subjected to mechanical deformation for 30 to 40 min by placing a coverslip on live cells in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by 100× imaging using an oil immersion objective, the GFP-MxA condensate often unraveled into an open filamentous meshwork (Fig. 8A). Because we had previously observed that the nitric oxide scavenger 2-4-carboxyphenyl-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide (c-PTIO) altered the cellular distribution of the ER proteins RTN4 and ATL3 (55), we investigated the effect of c-PTIO on MxA condensate structure (at a time when we still thought of MxA as ER associated). We observed that a GFP-MxA filamentous meshwork was frequently observed in cells in cultures that had been treated with c-PTIO (Fig. 8B). Because GTPase hydrolysis was known to cause movement within MxA oligomer meshworks (28–30, 34), we tested the effect of the dynamin GTPase inhibitor dynasore (56) on MxA condensate structure (even though dynasore customarily is advertised not to have an effect on MxA GTPase [56]). Figure 8C shows the filamentous transition of GFP-MxA structures in dynasore-treated Huh7 cells. Movies S2 and S3 illustrate time-lapse imaging of the GFP-MxA reticulum in cells in experiments shown in Fig. 8B and C. Filaments in these GFP-MxA reticular meshworks exhibited local oscillatory movements (Movies S2 and S3).

FIG 8.

Metastability of GFP-MxA condensates: transition to filamentous reticulum. (A) Huh7 cells in 35-mm plates were transfected with the pGFP-MxA expression vector. Two days later the live cells were placed under a coverslip with a drop of PBS and imaged using a 100× oil immersion objective. By 30 to 40 min into the imaging session, GFP-MxA was observed to be in a fibrillar meshwork in most cells. (B) GFP-MxA-expressing cells were treated with the nitric oxide scavenger c-PTIO (300 μM for 7 h). Fibrillar conversion of GFP-MxA condensates was first observed using a 40× water immersion objective (not shown) and further confirmed by placing a coverslip and 100× oil imaging with time-lapse data collection. Image shown is one illustrative example of a 100× time-lapse experiment. A time-lapse movie of a different cell is shown in Movie S2. (C) GFP-MxA-expressing cells were treated with dynasore (20 nM) for 4 days. Fibrillar conversion of GFP-MxA condensates was first observed using a 40× water immersion objective (not shown) and further confirmed by adding a coverslip and using 100× oil imaging with time-lapse data collection. The image shown is one illustrative example of a 100× time-lapse experiment. A time-lapse movie of a portion of the same cell is shown in Movie S3. All scale bars, 5 μm.

Rapid and reversible tonicity-driven phase transitions of GFP-MxA condensates.

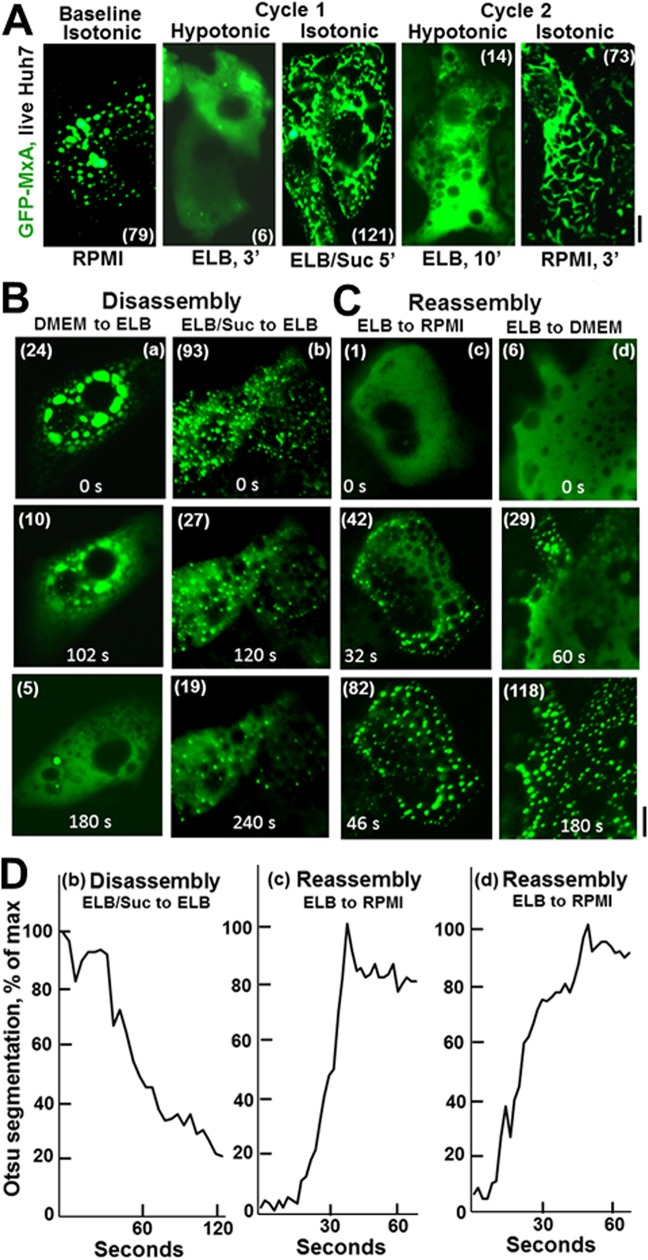

In live-cell studies of GFP-MxA-expressing Huh7 cells, we made the serendipitous discovery that exposing cells to hypotonic buffer typically used for swelling cells at the start of many cell fractionation protocols (e.g., erythrocyte lysis buffer, or ELB) (40 to 50 mosM) (57) led to a rapid transition of GFP-MxA from condensates to a dispersal in the cytosol in 1 to 3 min (Fig. 9A and Movie S4). Remarkably, this dispersed cytosolic GFP-MxA could be reassembled back into condensates (but different from the original ones in the same cell) by exposing cells to buffer made isotonic using sucrose (addition of 0.3 M sucrose to ELB) or regular RPMI 1640 medium (Fig. 9A and Movie S5; in particular, Movie S4 shows the same cell through disassembly and then reassembly of GFP-MxA condensates). GFP-MxA condensates could be repeatedly cycled back and forth through disassembly and reassembly multiple times (Fig. 9A shows 2 cycles). This cycling between disassembly and reassembly was a tonicity-driven event and not a salinity-driven event per se, in that simply leaving out or including 0.3 M sucrose in the low-salt ELB buffer sufficed to disassemble and reassemble GFP-MxA condensates, respectively, through multiple cycles (Fig. 9A, cycle 1, and Fig. 9Bb). Sequential exposure of GFP-MxA-expressing cells to ELB supplemented with different concentrations of sucrose identified the hypotonic range between 80 and 120 mosM for when disassembly became apparent (data not shown). The majority (80 to 90%) of GFP-MxA-expressing cells in a culture showed the phase transitions of disassembly and reassembly irrespective of the level of expression of MxA in individual cells (low, medium, or high levels in small puncta or large condensates). Exposing GFP-MxA-expressing cells to buffers made hypertonic with sucrose (approximately 500 mosM) also resulted in a change of shape from spherical MxA bodies to elongated cigar-shaped structures; this shape change was reversible upon returning the cells to isotonic medium and even disassembly upon shift to hypotonic buffer (ELB).

FIG 9.

Rapid and reversible tonicity-driven disassembly and reassembly of GFP-MxA condensates in the cytoplasm of Huh7 cells. (A) GFP-MxA-expressing cultures 2 days after transfection were sequentially imaged on a warm stage (37°C) using a 40× water immersion objective under isotonic conditions (RPMI 1640 medium), switched to hypotonic medium (erythrocyte lysis buffer [ELB] at approximately 40 mosM), imaged 3 min later and then switched to isotonic buffer (ELB supplemented with 0.3 M sucrose, net of approximately 325 to 350 mosM), and imaged 5 min later (cycle 1), followed by a second cycle of hypotonic and isotonic media as indicated. Scale bar, 10 μm. Numbers in parentheses are the separate objects counted in each using Otsu segmentation (Image J) and automatic investigator-independent thresholding. Scale bar, 10 μm. At the end of this experiment, the cultures were fixed and immunostained for the ER marker RTN4 to confirm that the reassembled GFP-MxA condensates were independent of the ER (data not shown). Movie S4 shows time-lapse images (5 s apart) of the first cycle of disassembly and then reassembly of GFP-MxA condensates in the same cell in a different experiment. Panels B and C show illustrative examples (labeled a, b, c, and d) of disassembly and reassembly of GFP-MxA condensates taken from time-lapse imaging experiments as generated by the medium/buffer changes indicated. Numbers in parentheses are the number of objects counted in each image using the Otsu segmentation protocol. Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) Quantitation of the speed of disassembly and reassembly using Otsu segmentation metrics in time-lapse movies corresponding to examples b, c, and d in panel B. Movie S5 shows the reassembly cell (c) in panels C and D.

Time-lapse imaging of cells subjected to disassembly and reassembly showed these phase transitions to be rapid processes initiated within 30 s and completed by 1 to 3 min (Fig. 8C and 9B and Movies S4 and S5). Disassembly was typically completed by 2 to 3 min and reassembly a bit faster by 1 to 2 min. As a control, cells expressing the N1-GFP tag alone did not show any condensates or any assembly and disassembly phase transitions (P. B. Sehgal, unpublished).

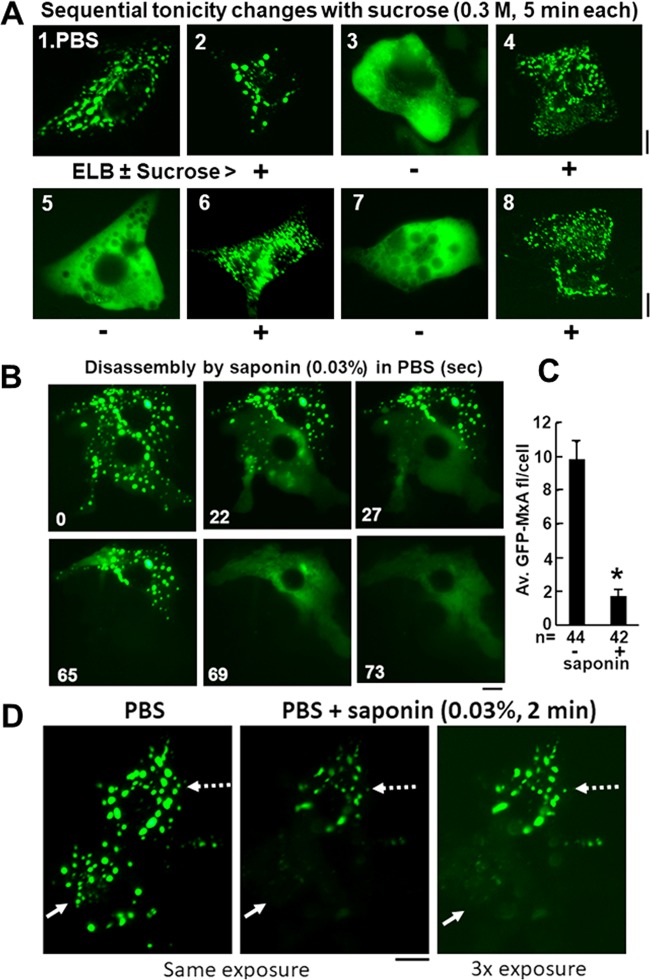

Additional evidence that disassembly and reassembly of GFP-MxA condensates was driven by changes in tonicity of the culture medium (e.g., upon adjustment with sucrose only) and not salinity of the medium per se is shown in Fig. 10A. Cells kept in a low-salt buffer (ELB) supplemented with 0.3 M sucrose to maintain isotonicity showed intact condensates (Fig. 10A, image 2). Subsequent cycling of the same cells through hypotonicity and isotonicity without changing the extracellular low-salt composition caused rapid disassembly and reassembly of GFP-MxA condensates through multiple cycles (3 cycles are shown in Fig. 10A).

FIG 10.

Dissecting the mechanism of disassembly and reassembly of GFP-MxA condensates. (A) A culture of Huh7 cells in a 35-mm plate expressing GFP-MxA kept continuously at 37°C was sequentially imaged in 5-min steps in the indicated media (warm PBS or warm ELB ± 0.3 M sucrose). Images 1 to 8 illustrate representative examples of cells at each stage (out of 10 to 20 images per step). (B) Huh7 cells expressing GFP-MxA condensates kept in PBS were imaged just before and just after exposure to saponin (0.03%)-containing PBS using time-lapse imaging as indicated. (C) Quantitation of the average fluorescence per cell in GFP-MxA-expressing cells without or with treatment of cultures with saponin (0.03%) in PBS for 2 to 5 min, expressed as means ± SE. n, number of cells evaluated; *, P < 0.001. (D) Huh7 cells expressing GFP-MxA condensates first were imaged in PBS (left) and then switched to saponin (0.03%)-supplemented PBS for 2 min with imaging at the same exposure setting (middle). At the conclusion of the experiment (5 min), the same cells were imaged using a 3× exposure setting. Solid white arrow indicates a cell in which saponin solubilized all of the GFP-MxA, while the dotted white arrow indicates a cell with residual saponin-resistant GFP-MxA structures. All scale bars, 10 μm.

Maintaining the integrity of GFP-MxA condensates required an intact plasma membrane. Permeabilization of the plasma membrane by saponin (0.03%) in isotonic salt-based medium (PBS) led to a rapid disassembly of GFP-MxA condensates with a loss of >80% of the GFP-MxA (Fig. 10B and C). Interestingly, in >50% of the cells in the culture, saponin permeabilization in isotonic salt medium left behind detergent-resistant cores (Fig. 10D shows one cell with resistant residual GFP-MxA structures [white broken arrow] and an adjacent cell with almost complete solubilization of GFP-MxA condensates [white solid arrow]). The saponin-resistant structures were no longer affected by further increasing or decreasing tonicity or salinity (data not shown). A composite detergent-responsive architecture is a known feature of other biomolecular condensates (see reference 58 for one recent example).

The earliest change visible microscopically in GFP-MxA-expressing Huh7 cells transitioning from a hypotonic state (and, thus, dispersed GFP-MxA) to an isotonic medium was the appearance within 15 to 20 s of GFP-free dark “droplets” (Fig. 9Cc, 32-s image, and Cd, 0- and 60-s images; also see Movie S5). Subsequently, GFP-MxA condensates formed within the interdroplet zones. Moreover, these dark droplet regions persisted through subsequent cycles of tonicity-driven GFP-MxA condensate disassembly and reassembly (as shown in Fig. 10A). These GFP-free droplets do not represent dilated ER cisternae, mitochondria, or endolysosomal elements, which are known to develop in cells under hypotonic conditions (59), as evaluated by us in live Huh7 cells using the ER luminal marker KDEL-mCh, MitoTracker, or LysoTracker (P. B. Sehgal, unpublished). However, the recent reports of Kosmalska et al. (60) and Holst et al. (61), identifying the rapid (within 1 to 2 min) development of large invaginations and vacuole-like dilations (VLDs) in hypotonically swollen cells shifted to isotonic conditions, provide an indication of the origins of these GFP-free droplets as part of a rapid specialized endocytic process involved in mechanoadaptation by substrate-adherent cells.

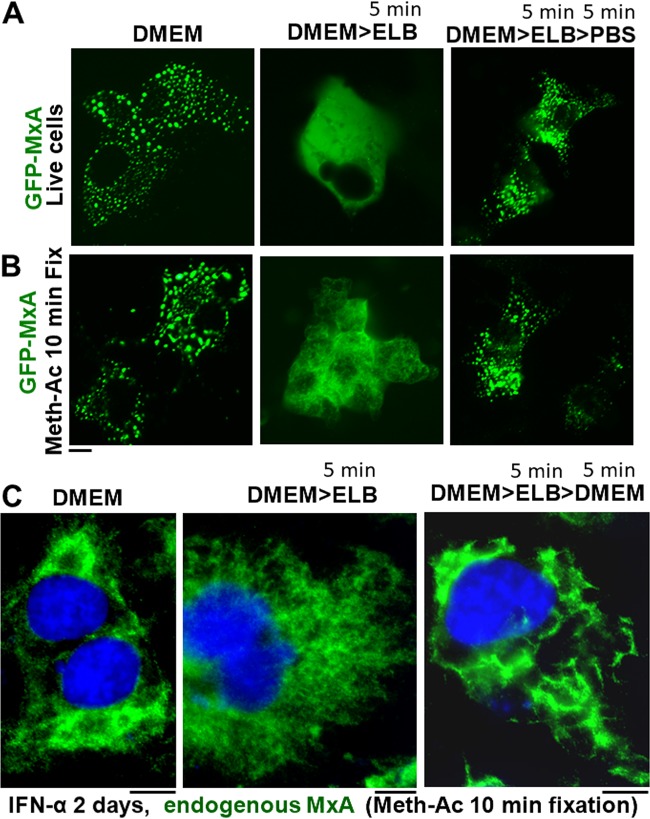

Tonicity-driven phase transitions in IFN-α-induced endogenous MxA reticulum.

As seen in Fig. 1D, we report that endogenous wild-type MxA expressed in IFN-α-induced Huh7 cells formed reticular structures in the cytoplasm. We investigated whether such endogenous MxA structures exhibited tonicity-driven phase transition properties. Since the detection of endogenous MxA structures in the cytoplasm of IFN-treated cells requires fixation and subsequent immunofluorescence staining methods for detection, it was necessary to first validate a method of fixation of cells in culture that would preserve the disassembled state of GFP-MxA condensates observed in live cells under hypotonic conditions. Figure 11A and B shows that the method of fixation of cultures for 10 min using methanol-acetone (1:1, vol/vol) at −20°C allowed for the preservation of the hypotonically disassembled state of GFP-MxA. Thus, in the experiment summarized in Fig. 11C, we used this methanol-acetone fixation technique on replicate IFN-α-treated cultures followed by immunofluorescence for endogenous MxA structures. Representative images from two independent experiments are shown. In Fig. 11C, the left panel shows the endogenous MxA reticulum in IFN-treated cells, the middle panel shows the disassembly of these structures after 5 min in hypotonic buffer, and the right panel shows the reassembly of endogenous MxA condensates upon switching back to isotonic medium for 5 min. Thus, endogenous MxA reticulum showed phase transitions similar to those observed for GFP-MxA.

FIG 11.

Tonicity-driven phase transitions of condensates of IFN-α-induced endogenous MxA in Huh7 cells. (A and B) Huh7 cultures transfected with GFP-MxA were used to test the ability of a 10-min fixation with methanol-acetone (1:1, vol/vol) (Meth-Ac) at −20°C to preserve the disassembled state after exposure of cells to hypotonic buffer (ELB) and the reassembled state after shift to isotonic buffer (PBS). Live and fixed cells were imaged in cultures as indicated. (C) Replicate Huh7 cultures were treated with IFN-α (2,000 IU/ml) for 2 days and then fixed with methanol-acetone for 10 min directly from full medium (DMEM), after 5 min in hypotonic medium (DMEM>ELB), or after reversal back to isotonic medium (DMEM>ELB>DMEM). The fixed cultures then were immunostained for endogenous MxA using an anti-MxA PAb and the fluorescence imaged using a 100× oil objective in z-stack mode. Respective slices were deconvolved and merged for illustration. All scale bars, 10 μm.

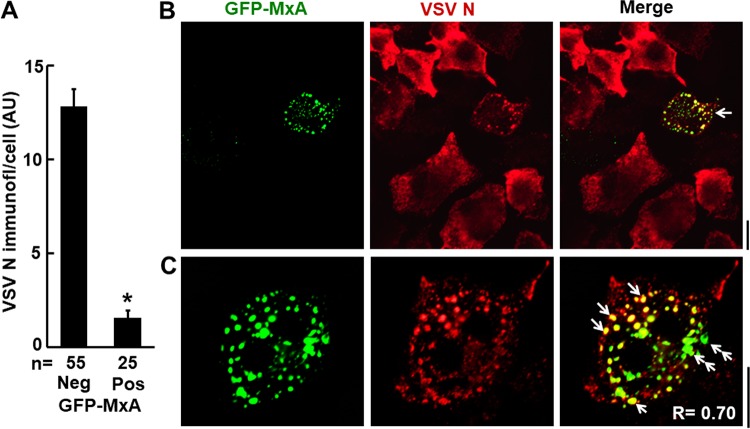

Recruitment of viral proteins by GFP-MxA condensates.

Biomolecular condensates have the property of recruiting other proteins and nucleic acids to affect cellular functions (1–6). Kochs et al. (35) had already reported that MxA associated with the nucleocapsid (N) proteins of La Crosse, Rift Valley, and Bunyamwera viruses and formed membraneless structures comprising MxA and N of La Crosse virus that did not associate with any cytoplasmic organelle or membrane. Inasmuch as Heinrich et al. (19) recently showed that the N protein (together with the P and L proteins) of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) formed cytoplasmic phase-separated liquid-like condensates, we investigated whether the GFP-MxA condensates recruited VSV N protein.

The data shown in Fig. 12A and B confirm the antiviral effect at the single-cell level of the expression of GFP-MxA in Huh7 cells. When assayed 4 h after VSV infection at a high multiplicity of infection (MOI) of >10 PFU/cell (62), GFP-MxA-positive cells showed a marked reduction in expression of the VSV N protein compared to that of GFP-MxA-negative cells in the same culture (Fig. 12A and B). In our experiments, this antiviral effect was observed strictly in cis; only cells expressing GFP-MxA showed reduced N immunostaining. Adjacent cells in the same culture (Fig. 12B), even cells in contact with GFP-MxA-positive cells, showed robust levels of VSV N protein expression. The higher-magnification images shown in Fig. 12C of a virus-infected GFP-MxA-expressing cell (from among 19 coexpresssing cells so imaged in this experiment) revealed the colocalization of VSV N protein with a subset of GFP-MxA condensates (white single arrows in Fig. 12C). It is noteworthy that there was biochemical heterogeneity in the association between N and GFP-MxA. In Fig. 12C, the round dot-like variably sized condensates showed colocalization (white single arrows) but not the larger irregular GFP-MxA condensates (white double arrows). Thus, in the VSV system, MxA condensates recruited the VSV N protein concomitant with the appearance of an antiviral effect.

FIG 12.

Antiviral effect of MxA. VSV nucleocapsid (N) protein associated with GFP-MxA condensates. Huh7 cells (approximately 2 × 105 per 35-mm plate), transfected with the pGFP-MxA expression vector 1 day earlier, were replenished with 0.25 ml serum-free Eagle’s medium, and then 10 μl of a concentrated VSV stock of the wild-type Orsay strain was added (corresponding to an MOI of >10 PFU/cell). The plates were rocked every 15 min for 1 h, followed by addition of 1 ml of full culture medium. The cultures were fixed at 4 h after the start of the VSV infection, and the extent and localization of N protein expression in individual cells was evaluated using immunofluorescence methods (using the mouse anti-N MAb) and Image J for quantitation. (A) N protein expression in GFP-MxA-negative (Neg) and -positive (Pos) cells in the same culture in arbitrary units (AU) per cell; values are means ± SE; *, P < 0.001. (B) Field of GFP-MxA-negative cells expressing high levels of N protein surrounding a GFP-MxA-positive cell with limited N protein expression. (C) Higher-magnification image of a different GFP-MxA-positive cell in the same culture as that shown in panel B expressing some N protein and the colocalization of N with GFP-MxA in spherical condensates (white arrows) as well as lack of colocalization in irregularly shaped GFP-MxA condensates (white double arrows). A total of 19 cells with overlap between GFP-MxA and VSV-N condensates, similar to the cell shown in panel C, were observed in this experiment. As a negative control, uninfected GFP-MxA-expressing Huh7 cells did not immunostain with anti-VSV-N MAb (data not shown). All scale bars, 20 μm.

DISCUSSION

In 2002, Kochs et al. (35) reported that in cells stably expressing MxA and infected with La Crosse virus, MxA formed cytoplasmic membrane-less complexes with the viral N protein (as judged by thin-section EM) which neither associated with any cytoplasmic organelle or membrane nor exhibited any markers for the ER or the Golgi apparatus. In the present study, we resurrect those observations and extend them to show that MxA structures, even in uninfected cells, comprised variably sized and shaped entities in the cytoplasm (spherical, filamentous, and reticular structures) that were membraneless (as judged by correlated light and electron microscopy) and did not display any markers for the ER or the Golgi apparatus. These cytoplasmic MxA structures exhibited properties of metastable (shape-changing) biomolecular condensates. The present study moves the MxA field into the realm of phase-separated biomolecular condensates.

Membraneless organelles (biomolecular condensates) in the cytoplasm and nucleus showing regulated phase transitions are increasingly viewed as critical in diverse cellular functions (1–13). In the present study, we show that exogenously expressed as well as endogenous IFN-α-induced MxA structures in the cytoplasm in uninfected cells displayed properties of membrane-less biomolecular condensates. We report the discovery of a unique phase transition property of cytoplasmic MxA condensates, namely, rapid disassembly and then reassembly when intact cells were cycled through exposure to hypotonic and then isotonic buffers, respectively, with each phase transition largely completed in a matter of less than 1 to 3 min. The controlling extracellular mechanism was tonicity driven and not salinity driven per se, i.e., adding and subtracting isotonic sucrose from a low-salt buffer (ELB) solution bathing the cells produced rapid GFP-MxA condensate assembly and disassembly, respectively. The GFP-MxA condensates comprised both a component (>80% of the GFP-MxA) solubilized by permeabilization of the plasma membrane by saponin (0.03% in isotonic buffer) and a saponin-resistant condensate core. Indeed, multilayered composite condensates with protein components differentially solubilized by detergents are common in condensate biology (54, 58). The GFP-MxA condensates in live cells were metastable and changed shape. We observed homotypic fusion events as well as a change in shape to filamentous meshworks and reticulum upon mechanical deformation, exposure to nitric oxide scavenging for several hours, and even treatment of cells with the dynamin family inhibitor dynasore (for 4 days). In a test of liquid-like internal properties, GFP-MxA condensates were rapidly disassembled by the plasma membrane-permeable aliphatic alcohol hexanediol. FRAP analyses showed only a 24% mobile fraction in the interior of the GFP-MxA condensates. This relative stiffness of GFP-MxA structures was in keeping with the known ability of MxA in cell-free studies in aqueous buffers to assemble into dimers, tetramers, and higher-order oligomers forming rods (∼50-nm length) and rings (∼36-nm diameter) based upon temperature, ionic conditions, and GTPase activity (28–34). We envisage GFP-MxA to form the multivalent scaffold of a network fluid which can then recruit various cellular and viral client proteins affecting their function (52–54, 58).

In intact cells, the integrity of MxA condensates, whether formed by MxA derived from exogenously introduced expression vectors or by endogenous MxA induced by IFN-α, was regulated by tonicity of the extracellular medium. Isotonic medium comprising a low-salt buffer (ELB) supplemented with 0.3 M sucrose maintained the integrity of GFP-MxA condensates. Subsequent tonicity changes generated by subtracting or adding back sucrose to the low-salt buffer sufficed to cause rapid disassembly and then reassembly of GFP-MxA condensates through several cycles. Thus, swelling and reversal of swelling of intact cells caused rapid reversible phase transitions in GFP-MxA condensates. We hypothesize that mechanisms underlying these phase transitions triggered by extracellular sucrose tonicity include changes in volume or “crowding” in the cytogel phase (as envisaged by Delarue et al. [8]). Additional ionic changes in the cytogel resulting from cell swelling and its reversal are also likely to contribute (52–54). Several investigators have reported additional rapid reversible biochemical changes (such as calcium signaling and protein kinase C activation) in cells subjected to an hyposmotic challenge and during recovery from such challenge (reviewed in references 59–61, 63, and 64). Although there are several reports of spontaneous self-oligomerization of recombinant MxA in cell-free assays (28–34), it is not clear whether the assembly of MxA into higher-order structures in the intact cell cytoplasm is a spontaneous self-assembly event per se or is an event that could be catalyzed by other cellular participants. Conversely, the possibility remains that disassembly also involves other cellular participants in the intact cell cytoplasm.

Inasmuch as intracellular edema and ionic changes are hallmarks of cytopathic viral infections (59, 65–69), the rapid hypotonicity-driven disassembly of MxA condensates may function to modulate the antiviral activity of MxA. Montasir et al., in their studies of vaccinia pneumonia in 1966, commented that “the most prominent early cytopathic change was intracellular edema evidenced by low electron density to the background cytoplasmic material and dilatation of endoplasmic reticulum” (69). Reduced cytoplasmic crowding or ionic changes in swollen cells exposed to hypotonic buffers would mimic the intracellular edema in virus-infected cells reported by Montasir et al. (69), triggering a phase transition (disassembly) of MxA condensates and resulting in a reduction in MxA antiviral activity. Experimentally, whether edema-like hypotonic disassembly of MxA condensates affects its antiviral activity remains unclear.

As for how MxA condensates contribute to an antiviral mechanism, data from several previous studies have emphasized the sequestration of viral nucleocapsid proteins critical to viral replication in cytoplasmic MxA structures (25–30, 35, 36). We confirmed the association of VSV N protein with the spherical but not irregularly shaped GFP-MxA condensates in cells showing an antiviral state (Fig. 12) suggestive of heterogeneity in condensate biochemistry. Whether GFP-condensate disassembly triggered by hypotonicity (causing swollen cells with intracellular edema) affects this antiviral state, and whether its reassembly enhances it, is a question that remains under investigation.

Tonicity-driven phase transitions in Huh7 cells have now been observed by us in another experimental context (12). We recently realized that the previously reported (70, 71) interleukin-6 (IL-6)-induced GFP-STAT3/PY-STAT3 cytoplasmic and nuclear bodies represented phase-separated biomolecular condensates which appeared in cells within 10 to 15 min of exposure to the cytokine in a Tyr phosphorylation-dependent manner (12). 1,6-Hexanediol caused disassembly of IL-6-induced cytoplasmic and nuclear STAT3 bodies within 30 to 60 s. Moreover, these STAT3 cytoplasmic and nuclear bodies showed rapid disassembly under hypotonic conditions and reassembly when cells were returned to isotonic medium (12). Hypotonicity-driven disassembly within 1 to 2 min has been reported recently for influenza A virus cytoplasmic membraneless condensates in A549 cells (24).

To summarize, the present studies shed light on a new aspect of the cell biology of MxA in the cytoplasm: the formation of metastable membrane-less condensates which can undergo rapid and reversible tonicity-driven phase transitions. MxA condensates likely comprise a multivalent network fluid as a scaffold which could recruit various viral and cellular client proteins. The recognition of MxA structures as phase-separated condensates places MxA research within the context of the extensive literature on virus interactions with other well-known biomolecular condensates, the stress granules and P bodies, many of which elicit an antiviral effect.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and cell culture.

Human kidney cancer cell line HEK293T was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Human hepatoma cell line Huh7 and its derivative, Huh7.5 (72), were gifts from Charles M. Rice, The Rockefeller University. Cos7 cells were a gift from Koko Murakami, New York Medical College. The respective cell lines were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS) in 90-mm plates. For experiments, Huh7 and Huh7.5 cells were grown in regular 6-well plates or 35-mm dishes, while HEK293T cells were grown in similar plates coated with fibronectin, collagen, and bovine serum albumin (1 μg/ml, 30 μg/ml, and 10 μg/ml in coating medium, respectively) (73). For CLEM, Huh7 cells were grown sparsely in 35-mm gridded 1.5-mm coverslip plates (no. P35G-1.5-14-C-GRID; MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA). Recombinant human IFN-α2a was purchased from BioVision (Milpitas, CA). In the present experiments, Huh7 cultures were exposed for 2 days to IFN-α at a concentration of 2,000 to 3,000 IU/ml in DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS prior to fixation and immunofluorescence analyses (43, 44). Whole-cell extract and Western blot analyses for MxA were carried out as previously reported (43, 44).

Plasmids and transient transfection.

The HA-tagged human MxA expression vector (cloned into a pcDNA3 vector) was a gift from Otto Haller (University of Freiburg, Germany) (25, 57) and was the same MxA expression construct as that used by Stertz et al. (37), with the HA tag located on the N-terminal side of the MxA coding sequence. The GFP(1-248)-tagged human MxA expression vector was a gift of Jovan Pavlovic (University of Zurich, Switzerland) (46, 47); the GFP tag was located on the N-terminal side of the MxA coding sequence. HA-tagged ATL3 vector was a gift from Craig Blackstone (National Institutes of Health) (73, 74), and the mCherry-tagged CLIMP63, RTN4, Sec61β, and KDEL expression vectors were gifts from Jason E. Lee and Gia Voeltz (University of Colorado at Boulder) (40). Transient transfections were carried out using barely subconfluent cultures in 35-mm plates or in wells of a 6-well plate using DNA in the range of 0.3 to 2 μg/culture and the PolyFect reagent (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) per the manufacturer’s protocol.

VSV stock and virus infection.

A stock of the wild-type Orsay strain of VSV (titer of 9 × 108 PFU/ml) was a gift of Douglas S. Lyles (Department of Biochemistry, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC). Virus infection was carried out essentially as described by Carey et al. (62). Briefly, Huh7 cells (approximately 2 × 105 per 35-mm plate), previously transfected with the pGFP-MxA expression vector (1 to 2 days earlier), were replenished with 0.25 ml serum-free Eagle’s medium, and 10 μl of the concentrated VSV stock was added (corresponding to an MOI of >10 PFU/cell). The plates were rocked every 15 min for 1 h, followed by addition of 1 ml of full culture medium. For the experiment shown in Fig. 12, the cultures were fixed at 4 h after the start of the VSV infection.

Immunofluorescence imaging.

Typically, 1 to 2 days after transient transfection of the respective vectors, the cultures were fixed using cold paraformaldehyde (4%) for 1 h and then permeabilized using a buffer containing digitonin (50 μg/ml)–sucrose (0.3 M) (43, 44, 55, 75, 76). Single-label and double-label immunofluorescence assays were carried out using antibodies as indicated below, with the double-label assays performed sequentially. Fluorescence was imaged as previously reported (43, 44, 55, 75, 76) using an erect Zeiss AxioImager M2 motorized microscopy system with a Zeiss W N-Achroplan 40×, 0.75-numeric-aperture (NA) water immersion objective or Zeiss EC Plan-Neofluor 100×, 1.3-NA oil objective equipped with a high-resolution RGB HRc AxioCam camera and AxioVision 4.8.1 software in a 1,388- by 1,040-pixel high-speed color capture mode. Images in z-stacks were captured using Zeiss AxioImager software; these stacks were then deconvolved and rendered in three dimensions (3D) using the 64-bit version of the Zeiss AxioVision software. Deconvolution filtering of 2D images was carried out using Image J (Fiji) software. Colocalization analyses were carried out using Image J software (Fiji) and deriving the Pearson’s colocalization coefficient R with Costes’ automatic thresholding (77). Line scans were carried out using AxioVision 4.8.1 software.

High-resolution immunofluorescence/fluorescence imaging of selected cultures was carried out using a Leica SP5 II confocal microscopy system with a Leica HCX APO L 40×, 0.8-NA water immersion objective or a Zeiss Confocal 880 Airyscan system (100× oil, 1.46-NA objective).

Live-cell imaging of GFP-MxA and mCherry-tagged ER markers was carried out in cells grown in 35-mm plates using the upright Zeiss AxioImager 2 equipped with a warm (37°C) stage and a 40× water immersion objective and also by placing a coverslip on the sheet of live cells and imaging using the 100× oil objective (as describe above) with data capture in a time-lapse or z-stack mode (using AxioVision 4.8.1 software).

FRAP experiments were performed on a Zeiss LSM880 confocal microscope with a Zeiss Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.4 NA oil objective on 9 randomly picked cells. Five prebleach images were acquired before 25 cycles of bleaching with full power of an argon 488-nm laser on a small area (∼3 μm2), which reduces intensity to ∼50%. Fluorescence recovery was monitored continuously for 30 s at 2 frames/s. All image series were aligned and registered with Fiji ImageJ’s SIFT plugin, and FRAP analyses of mobile fraction and half-life (t1/2) were performed afterwards with a Jython script (https://imagej.net/Analyze_FRAP_movies_with_a_Jython_script) incorporated into Image J (Fiji).

Phase transition experiments.

Live GFP-MxA-expressing Huh7 hepatoma cells in 35-mm plates were imaged using a 40× water immersion objective 2 to 5 days after transient transfection in growth medium, serum-free RPMI 1640 medium, or PBS. After collecting baseline images of MxA condensates (including time-lapse sequences), the isotonic buffers were removed using a Pasteur pipette and replaced with hypotonic ELB (10 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 3 mM MgCl2) supplemented with 0.3 M sucrose or left unsupplemented, followed by time-lapse imaging at 2- to 5-s intervals. After 5 to 10 min (by which time >85% of cells showed complete disassembly of the GFP-MxA condensates in hypotonic buffer), the cultures were subsequently sequentially exposed to additional various isotonic and hypotonic buffers, as enumerated in the respective figure legends. Alpini et al. (78) have shown that the hepatocyte plasma membrane is not permeable to sucrose.

Electron microscopy.

For immuno-EM, the cultures were fixed with paraformaldehyde (4%) for 20 min at 37°C and then for another 40 min at room temperature (73). After fixation, the cells were washed with ice-cold PBS, scraped into an Eppendorf tube, and pelleted by centrifugation for 15 s. The cell pellets were fixed in freshly made 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS containing 0.2% glutaraldehyde, pH 7.2 to 7.4, for 4 h at 4°C. After washing with PBS, the cells were embedded with 10% gelatin, infused with sucrose, and cryosectioned at 80-nm thickness onto 200-mesh carbon-Formvar-coated copper grids. For single MxA labeling, the grids were blocked with 1% coldwater fish skin gelatin (Sigma) for 5 min and incubated with MxA antibody (rabbit PAb) in blocking solution for 2 h at room temperature. Following washing with PBS, gold-conjugated secondary antibodies (15-nm protein A-gold [Cell Microscopy Center, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands] or 18-nm colloidal gold-AffiniPure goat anti-rabbit IgG [Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA]) were applied for 1 h. The grids were fixed in 1% glutaraldehyde for 5 min, washed with distilled water, contrasted, and embedded in a mixture of 3% uranyl acetate and 2% methylcellulose at a ratio of 1 to 9. For double immunolabeling, goat anti-RTN4 antibody was applied first, and the 6-nm colloidal gold-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA) was the secondary antibody. After fixing with 1% glutaraldehyde for 10 min, rabbit anti-MxA antibody was applied, and 15-nm protein A-gold was used as the secondary antibody. Electron microscopy was carried out using a Philips CM-12 electron microscope (FEI, Eindhoven, The Netherlands), and images were photographed with using a Gatan (4k × 2.7k) digital camera (Gatan, Inc., Pleasanton, CA).

For CLEM (50, 51), Huh7 cells plated sparsely in 35-mm gridded coverslip plates were transiently transfected with the pGFP-MxA vector. Two days later the cultures were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h at 4°C. Confocal imaging was carried out using a tiling protocol to identify the location of specific cells with GFP-MxA structures on the marked grid. The cultures were then further fixed (2.5% glutaraldehyde for 2 h at 4°C, postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide for 1.5 h at room temperature) and embedded (in EMbed 812; Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). The previously identified grid locations were used for serial thin sectioning (60 nm), mounted on 200-mesh thin-bar copper grids, and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate using standard methods. The tiled light microscopy data were correlated with the tiled EM thin-section data to identify the ultrastructure of the GFP-fluorescent structures.

Antibody reagents.

Rabbit PAb to human MxA (also referred to as human Mx1) (H-285) (sc-50509), goat PAb to RTN4/NogoB (N18) (sc-11027), and mouse MAbs to cGAS (D-9) (sc-515777), β-tubulin (2-28-33) (sc-23949), and vimentin (V9) (sc-6260) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Rabbit PAbs to atlastin 3 (ATL3) (ab104262) and to giantin (1-469 fragment) (ab24586) were purchased from Abcam, Inc. (Cambridge, MA). Mouse MAb to the HA tag (262K; number 2362) and rabbit MAb to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 14C10; number 2118) were obtained from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA), while mouse MAb to the VSV nucleocapsid (N), designated 10G4, was a gift from Douglas S. Lyles (Wake Forest School of Medicine, NC). Respective Alexa Fluor 488- and Alexa Fluor 594-tagged secondary donkey antibodies to rabbit (A-11008 and A-11012), mouse (A-21202 and A-21203), or goat (A-11055 and A-11058) IgG were from Invitrogen Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by funding from the New York Medical College and personal funding from P.B.S. We thank Joseph D. Etlinger and Kenneth Lerea for insightful discussions.

D.D., P.B.S., H.Y., and F.L. designed the studies. D.D., H.Y., J.W., Y.M.Y., and P.B.S. carried out the cell culture experiments, collected all the wide-field microscopy data, including live-cell imaging, and also analyzed all the data (wide-field, confocal, and electron microscopy). Y.D. carried out all the high-resolution confocal imaging and FRAP. F.L., C.P., K.D.-M., and J.S. carried out all of the electron microscopy, including CLEM, and collected the EM data. P.B.S. and D.D. compiled the data figures, and P.B.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01014-19.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mitrea DM, Kriwacki RW. 2016. Phase separation in biology; functional organization of a higher order. Cell Commun Signal 14:1. doi: 10.1186/s12964-015-0125-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banani SF, Lee HO, Hyman AA, Rosen MK. 2017. Biomolecular condensates: organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 18:285–298. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shin Y, Brangwynne CP. 2017. Liquid phase condensation in cell physiology and disease. Science 357:eaaf4382. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alberti S. 2017. The wisdom of crowds: regulating cell function through condensed states of living matter. J Cell Sci 130:2789–2796. doi: 10.1242/jcs.200295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomes E, Shorter J. 2018. The molecular language of membraneless organelles. J Biol Chem 294:7115–7127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.TM118.001192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du M, Chen ZJ. 2018. DNA-induced liquid phase condensation of cGAS activates innate immune signaling. Science 361:704–709. doi: 10.1126/science.aat1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milovanovic D, Wu Y, Bian X, De Camilli P. 2018. A liquid phase of synapsin and lipid vesicles. Science 361:604–607. doi: 10.1126/science.aat5671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delarue M, Brittingham GP, Pfeffer S, Surovtsev IV, Pinglay S, Kennedy KJ, Schaffer M, Gutierrez JI, Sang D, Poterewicz G, Chung JK, Plitzko JM, Groves JT, Jacobs-Wagner C, Engel BD, Holt LJ. 2018. mTORC1 controls phase separation and the biophysical properties of the cytoplasm by tuning crowding. Cell 174:338–349. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plys AJ, Kingston RE. 2018. Dynamic condensates activate transcription. Science 361:329–330. doi: 10.1126/science.aau4795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langdon EM, Qiu Y, Ghanbari Niaki A, McLaughlin GA, Weidmann CA, Gerbich TM, Smith JA, Crutchley JM, Termini CM, Weeks KM, Myong S, Gladfelter AS. 2018. mRNA structure determines specificity of a polyQ-driven phase separation. Science 360:922–927. doi: 10.1126/science.aar7432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sabari BR, Dall’Agnese A, Boija A, Klein IA, Coffey EL, Shrinivas K, Abraham BJ, Hannett NM, Zamudio AV, Manteiga JC, Li CH, Guo YE, Day DS, Schuijers J, Vasile E, Malik S, Hnisz D, Lee TI, Cisse II, Roeder RG, Sharp PA, Chakraborty AK, Young RA. 2018. Coactivator condensation at super-enhancers links phase separation and gene control. Science 361:eaar3958. doi: 10.1126/science.aar3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sehgal PB. 2019. Biomolecular condensates in cancer cell biology: interleukin-6-induced cytoplasmic and nuclear STAT3/PY-STAT3 condensates in hepatoma cells. Contemp Oncol 23:16–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Itakura AK, Futia RA, Jarosz DF. 2018. It pays to be in phase. Biochemistry 57:2520–2529. doi: 10.5114/wo.2019.83018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reineke LC, Lloyd RE. 2013. Diversion of stress granules and P-bodies during viral infection. Virology 436:255–267. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Onomoto K, Yoneyama M, Fung G, Kato H, Fujita T. 2014. Antiviral innate immunity and stress granule responses. Trends Immunol 35:420–428. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rozelle DK, Filone CM, Kedersha N, Connor JH. 2014. Activation of stress response pathways promotes formation of antiviral granules and restricts virus replication. Mol Cell Biol 34:2003–2016. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01630-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malinowska M, Niedzwiedzka-Rystwej P, Tokarz-Deptula B, Deptula M. 2016. Stress granules (SG) and processing bodies (PB) in viral infections. Acta Biochim Pol 63:183–188. doi: 10.18388/abp.2015_1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCormick C, Khapersky DA. 2017. Translation inhibition and stress granules in the antiviral immune response. Nat Rev Immunol 17:647–660. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinrich BS, Maliga Z, Stein DA, Hyman AA, Whelan S. 2018. Phase transitions drive the formation of vesicular stomatitis virus replication compartments. mBio 9:e02290-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02290-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dinh PX, Beura LK, Das PB, Panda D, Das A, Pattnaik AK. 2013. Induction of stress granule-like structures in vesicular stomatitis virus-infected cells. J Virol 87:372–383. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02305-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikolic J, Le Bars R, Lama Z, Scrima N, Lagaudrière-Gesbert C, Gaudin Y, Blondel D. 2017. Negri bodies are viral factories with properties of liquid organelles. Nat Commun 8:58. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00102-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoenen T, Shabman RS, Groseth A, Herwig A, Weber M, Schudt G, Dolnik O, Basler CF, Becker S, Feldmann H. 2012. Inclusion bodies are a site of ebolavirus replication. J Virol 86:11779–11788. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01525-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tawara JT, Goodman JR, Imagawa DT, Adams JM. 1961. Fine structure of cellular inclusions in experimental measles. Virology 14:410–416. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(61)90332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alenquer M, Vale-Costa S, Sousa AL, Etibor TA, Ferreira F, Amorim MJ. 2019. Influenza A virus ribonucleoproteins form liquid organelles at endoplasmic reticulum exit sites. Nat Commun 10:1629. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09549-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haller O, Kochs G. 2002. Interferon-induced mx proteins: dynamin-like GTPases with antiviral activity. Traffic 3:710–717. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.31003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haller O, Staeheli P, Kochs G. 2007. Interferon-induced Mx proteins in antiviral host defense. Biochimie 89:812–818. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haller O, Staeheli P, Schwemmle M, Kochs G. 2015. Mx GTPases: dynamin-like antiviral machines of innate immunity. Trends Microbiol 23:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sadler AJ, Williams B. 2011. Dynamiting viruses with MxA. Immunity 35:491–493. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao S, von der Malsburg A, Paeschke S, Behlke J, Haller O, Kochs G, Daumke O. 2010. Structural basis of oligomerization in the stalk region of dynamin-like MxA. Nature 465:502–506. doi: 10.1038/nature08972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao S, von der Malsburg A, Dick A, Faelber K, Schroder GF, Haller O, Kochs G, Daumke O. 2011. Structure of myxovirus resistance protein a reveals intra- and intermolecular domain interactions required for the antiviral function. Immunity 35:514–525. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dick A, Graf L, Olal D, von der Malsburg A, Gao S, Kochs G, Daumke O. 2015. Role of nucleotide binding and GTPase domain dimerization in dynamin-like myxovirus resistance protein A for GTPase activation and antiviral activity. J Biol Chem 290:12779–12792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.650325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Accola MA, Huang B, Al Masri A, McNiven MA. 2002. The antiviral dynamin family member, MxA, tubulates lipids and localizes to the smooth endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 277:21829–21835. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201641200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.von der Malsburg A, Abutbul-Ionita I, Haller O, Kochs G, Danino D. 2011. Stalk domain of the dynamin-like MxA GTPase protein mediates membrane binding and liposome tubulation via the unstructured L4 loop. J Biol Chem 286:37858–37865. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.249037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rennie ML, McKelvie SA, Bulloch EM, Kingston RL. 2014. Transient dimerization of human MxA promotes GTP hydrolysis, resulting in a mechanical power stroke. Structure 22:1433–1445. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kochs G, Janzen C, Hohenberg H, Haller O. 2002. Antivirally active MxA protein sequesters La Crosse virus nucleocapsid protein into perinuclear complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:3153–3158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052430399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reichelt M, Stertz S, Krijnse-Locker J, Haller O, Kochs G. 2004. Missorting of LaCrosse virus nucleocapsid protein by the interferon-induced MxA GTPase involves smooth ER membranes. Traffic 5:772–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stertz S, Reichelt M, Krijnse-Locker J, Mackenzie J, Simpson JC, Haller O, Kochs G. 2006. Interferon-induced, antiviral human MxA protein localizes to a distinct subcompartment of the smooth endoplasmic reticulum. J Interferon Cytokine Res 26:650–660. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.26.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Numajiri Haruki A, Naito T, Nishie T, Saito S, Nagata K. 2011. Interferon-inducible antiviral protein MxA enhances cell death triggered by endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Interferon Cytokine Res 31:847–856. doi: 10.1089/jir.2010.0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu J, Rapoport TA. 2016. Fusion of the endoplasmic reticulum by membrane-bound GTPases. Semin Cell Dev Biol 60:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Westrate LM, Lee JE, Prinz WA, Voeltz GK. 2015. Form follows function: the importance of endoplasmic reticulum shape. Annu Rev Biochem 84:791–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-072711-163501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu TY, Bian X, Romano FB, Shemesh T, Rapoport TA, Hu J. 2015. Cis and trans interactions between atlastin molecules during membrane fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:E1851–E1860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504368112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shemesh T, Klemm RW, Romano FB, Wang S, Vaughan J, Zhuang X, Tukachinsky H, Kozlov MM, Rapoport TA. 2014. A model for the generation and interconversion of ER morphologies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:E5243–E5251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419997111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yuan H, Sehgal PB. 2016. MxA is a novel regulator of endosome-associated transcriptional signaling by bone morphogenetic proteins 4 and 9 (BMP4 and BMP9). PLoS One 11:e0166382. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davis D, Yuan H, Yang YM, Liang FX, Sehgal PB. 2018. Interferon-alpha-induced cytoplasmic MxA structures in hepatoma Huh7 and primary endothelial cells. Contemp Oncol 22:86–94. doi: 10.5114/wo.2018.76149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davis D, Yuan H, Liang F-X, Yang Y-M, Westley J, Petzold C, Dancel-Manning K, Deng Y, Sall J, Sehgal PB. 2019. Human antiviral protein MxA forms novel metastable membrane-less cytoplasmic condensates exhibiting rapid reversible “crowding”-driven phase transitions. bioRxiv 10.1101/568006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Wisskirchen C, Ludersdorfer TH, Muller DA, Moritz E, Pavlovic J. 2011. Interferon-induced antiviral protein MxA interacts with the cellular RNA helicases UAP56 and URH49. J Biol Chem 286:34743–34751. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.251843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]