Summary

Background

Neuroimaging studies have identified obesity‐related differences in the brain's resting state activity. An imbalance between homeostatic and reward aspects of ingestive behaviour may contribute to obesity and food addiction. The interactions between early life adversity (ELA), the reward network and food addiction were investigated to identify obesity and sex‐related differences, which may drive obesity and food addiction.

Methods

Functional resting state magnetic resonance imaging was acquired in 186 participants (high body mass index [BMI]: ≥25: 53 women and 54 men; normal BMI: 18.50–24.99: 49 women and 30 men). Participants completed questionnaires to assess ELA (Early Traumatic Inventory) and food addiction (Yale Food Addiction Scale). A tripartite network analysis based on graph theory was used to investigate the interaction between ELA, brain connectivity and food addiction. Interactions were determined by computing Spearman rank correlations, thresholded at q < 0.05 corrected for multiple comparisons.

Results

Participants with high BMI demonstrate an association between ELA and food addiction, with reward regions playing a role in this interaction. Among women with high BMI, increased ELA was associated with increased centrality of reward and emotion regulation regions. Men with high BMI showed associations between ELA and food addiction with somatosensory regions playing a role in this interaction.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that ELA may alter brain networks, leading to increased vulnerability for food addiction and obesity later in life. These alterations are sex specific and involve brain regions influenced by dopaminergic or serotonergic signalling.

Keywords: Early life adversity, food addiction, obesity, sex difference

Introduction

Despite countless advances in the field, the pathophysiology of obesity remains complex and poorly understood – with multiple factors, including environmental factors such as a toxic food environment, playing a key role 1, 2. For some individuals, a history of early life adversity (ELA), including physical and emotional abuse, trauma, neglect and family discord, can increase the risk of developing obesity in adulthood through mechanisms associated with stress, inflammation, emotional perturbations, maladaptive coping, metabolic disturbances and food addiction 3, 4. As highlighted by a recent meta‐analysis, a history of childhood abuse (physical, emotional, sexual or general) is significantly associated with greater odds of adulthood obesity, and the odds of obesity increased depending on the severity and number of types of abuse 5. Another study found that severely obese adults undergoing gastric bypass surgery had prevalence rates of childhood abuse as high as 76% even after accounting for factors such as stigma, shame and guilt associated with underreporting 6. An additional study found that all but two of 63 participants who underwent bariatric surgery reported a history of adverse childhood experience 7.

Early life adversity experiences can become biologically embedded and lead to cognitive, emotional, somatic and behavioural problems in adulthood 8. Evidence from neuroimaging studies suggests that a history of ELA can have a sustained impact on the integrity and function of the brain 9, 10, 11, 12, with brain regions associated with emotional regulation, cognitive modulation and feeding behaviours frequently implicated 12, 13, 14, 15, 16. Furthermore, salience and emotion regulation brain networks are especially susceptible to topological restructuring associated with ELAs 11.

Although the relationship between ELA and adult obesity is incompletely understood, some possible explanations for the reported associations have been offered. One main factor has been the link with a compulsive eating behaviour termed food addiction 17, 18. Although not a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) diagnosis, the concept of food addiction is based on the substance dependence criteria found in the DSM‐IV and DSM‐V, describing excessive food intake primarily for pleasure, beyond the homeostatic needs of the organism; this behaviour often involves loss of control over eating, excessive time or focus on food, neglect of other activities and continuation of the behaviour despite known negative consequences 19, 20. A background of ELA may potentiate food addiction behaviours in some individuals, especially within the context of an environment rich in highly processed, calorie dense and extremely palatable food 4, 21, 22.

Food addiction is driven by the interactions of dopaminergic pathways with other central nervous system (CNS) networks, such as those involving the hypothalamus. Overindulgence of foods rich in fat and sugar has been shown to reduce CNS reward thresholds, resulting in a drive for higher intake of such palatable foods to achieve similar levels of satisfaction 22. A history of ELA contributes to an imbalance in these CNS networks 4. One theory posits that adversity during childhood, a key neurodevelopmental period, may disrupt neuronal growth by making stress‐sensitive brain circuits vulnerable to the effects of glucocorticoids, inflammatory cytokines and excitatory microbial metabolites 15, 23. There is also evidence to suggest a role for changes in the brain's serotonergic signalling by ELA and that these alterations may contribute to obesity and food addiction 15. For example, a study of 55 women showed that lowering of CNS serotonin by acute tryptophan depletion resulted in increased sweet calorie intake and a heightened preference for sweet foods in overweight but not normal weight individuals 24. Disruptions to these brain networks may override homeostatic needs and drive the overconsumption of highly palatable foods 25, 26.

The other factors to consider within a systems biological model of obesity are sex differences – an important basic variable that influences the quality and generalizability of biomedical research 27. Although studies in the USA suggest similar rates of obesity in men and women 28, international studies show a greater prevalence in women 29. Furthermore, striking sex differences have been observed in eating behaviours and food cravings, resulting in an increased risk for obesity 30, 31, 32. For example, women with obesity report higher food addiction behaviours, cravings, comorbidity and reward sensitivity than men with obesity 33, 34, 35. Other clear sex differences are reflected in the greater number in women of unsuccessful attempts to maintain weight loss and in the higher progressive weight gain (‘yo‐yo effect’) 29, 32, 36, 37, 38.

Neuroimaging studies have identified some of the brain mechanisms associated with obesity and food addiction 39, 40, demonstrating alterations in the core reward network (e.g. nucleus accumbens) and the extended reward network (i.e. emotion regulation, executive control, salience and somatosensory networks) 41, 42, 43. Beyond identification of anatomical and functional alterations of brain regions, recent neuroimaging studies have shifted their focus on identifying alterations in brain network properties 44. Within the framework of complex network analysis via graph theory, brain regions can be characterized by their ‘centrality’ or contribution to the functional integrity and information flow in the entire brain network 45, 46, 47, 48. Regions with high centrality are considered essential for information flow and integrative processing 46, 49, 50. Previous work has shown that individuals who are overweight demonstrate increased centrality between reward network regions and regions of the executive control, emotional regulation and somatosensory networks 41; sex‐specific brain alterations have also been reported in obesity and ELA studies 11, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57. These findings underscore the importance of studying ELA and sex‐related differences in the alterations of core and extended reward networks in obesity.

Previouse studies have explored the interaction between body mass index (BMI), brain centrality and food addiction 58. This study expands on previous work and investigates commonalities and differences between men and women in the relationship between ELA and alterations in the extended reward network of the brain, within the context of food addiction. Three hypotheses are tested: (1) increased ELA is associated with greater functional measures of centrality between core and extended reward regions in individuals with high BMI compared with individual with normal BMI. (2) The observed ELA–brain associations are greater with food addiction levels in individuals with high BMI compared with invididuals with normal BMI. (3) In women with high BMI, greater ELA is associated with increased centrality of reward and emotion regulation regions but decreased centrality of salience regions. In contrast, in men with high BMI, greater ELA is associated with increased centrality of somatosensory regions.

Materials and methods

Participants

Participants between the ages of 18 and 50 years were recruited through the University of California, Los Angeles, and local community advertisements. A nurse practitioner performed a clinical assessment of all participants, which included a mini‐mental state exam 59, 60. The sample was composed of 186 right‐handed participants (84 men and 102 women), with the absence of significant medical or psychiatric conditions. Participants were excluded for the following: pregnant or lactating, illicit drug use and substance abuse including alcohol abuse as specified by DSM criteria, abdominal surgery, tobacco dependence (half a pack or more daily), extreme strenuous exercise (>8 h of continuous exercise per week), current or past psychiatric illness and major medical or neurological conditions. Participants taking medications that interfere with the CNS or regular use of analgesic drugs were excluded. Because female sex hormones such as oestrogen are known to affect brain structure and function, only women who were in premenopausal with regular menstrual cycles and who were scanned during the follicular phase of their menstrual cycles (i.e. 4–12 d after the first day of the last menstrual period) were included in this study.

Participants with hypertension, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, eating disorders, such as anorexia or bulimia, substance abuse, tobacco dependence and psychiatric illnesses were excluded to minimize confounding effects. Participants were also excluded if they had undergone any bariatric surgery. The BMI cut‐offs are as follows: the normal BMI group consisted of individuals with BMI < 25, and the high BMI group consisted of individual with BMI ≥25 (overweight and obese). Previous work has shown that the overweight and obese brain shows similar alterations in reward networks of the brain 41. No participants exceeded 400 lb because of magnetic resonance imaging scanning weight limits.

All procedures complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Institutional Review Board at UCLA's Office of Protection for Research Participants. All participants provided written informed consent.

Questionnaires

Participants filled out the Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS) questionnaire, a 25‐item scale developed to measure food addiction by assessing signs of substance dependence symptoms in eating behaviour 61. This scale is based upon the substance dependence criteria found in the DSM‐IV 19 (e.g. tolerance [marked increase in amount; marked decrease in effect], withdrawal [agitation, anxiety and physical symptoms] and loss of control [eating to the point of feeling physical ill]) 61. Although food addiction is often measured using the diagnostic criteria with a YFAS cut‐off score of 3 to indicate a dichotomous ‘diagnosis’, we used the symptom count measure for our tripartite analysis (described in the succeeding texts), as this analysis functions best with continuous variables. For our study, higher YFAS symptom scores indicate greater addiction‐like criteria. The YFAS has displayed a good internal reliability α = 0.86 61. The internal reliability for the study sample for YFAS was α = 0.73. Subjective socio‐economic status was measured using the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status, a tool that has been previously used in large epidemiological studies conducted in the USA 62.

Early life adversity was measured using the Early Traumatic Inventory – Self Report (ETI‐SR) 63, a 27‐item (total score 0–27) questionnaire. This questionnaire assesses the histories of childhood traumatic and adverse life events that occurred before the age of 18 years old and covers four domains: general trauma (11 items), physical punishment (five items), emotional abuse (five items) and sexual abuse (six items). General traumatic events comprise a range of stressful and traumatic events that can be mostly secondary to chance events. Sample items on this scale include death of a parent, discordant relationships or divorce between parents or death or sickness of a sibling or friend. Physical abuse involves physical contact, constraint or confinement, with intent to hurt or injure. Sample items on the physical abuse subscale include being spanked by hand or being hit by objects. Emotional abuse is verbal communication with the intention of humiliating or degrading the victim. Sample items on the ETI‐SR emotion subscale include the following, ‘Often put down or ridiculed’ or ‘Often told that one is no good’. Sexual abuse is unwanted sexual contact performed solely for the gratification of the perpetrator or for the purposes of dominating or degrading the victim. Sample items on the sexual abuse scale include being forced to pose for suggestive photographs, to perform sexual acts for money or to coercive anal sexual acts against one's will. Each subscale score was calculated based on the number of items receiving a positive response. The ETI‐SR was the instrument chosen because of its psychometric properties, ease of administration, time efficiency and ability to measure ELAs in multiple domains 63. Each ETI‐SR subscale has good reliability (α = 0.70–0.87) and validity (r = 0.32–0.44) 63. The internal reliability for the study sample for the ETI‐SR total scale was α = 0.70.

Magnetic resonance imaging acquisition

Whole brain structural and functional (resting state) data were acquired using a 3.0 T Siemens Prisma MRI scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). Women were scanned during the follicular phase of their menstrual cycle. Detailed information on the standardized acquisition protocols, quality control measures and image preprocessing are provided in previously published studies 11, 41, 56, 57, 64, 65.

Structural magnetic resonance imaging

High‐resolution T1‐weighted images were acquired: echo time/repetition time = 3.26 ms/2,200 ms, field of view = 220 × 220 mm, slice thickness = 1 mm, 176 slices, 256 × 256 voxel matrices and voxel size = 0.86 × 0.86 × 1 mm.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging

Resting‐state scans were acquired with eyes closed and an echo planar sequence with the following parameters: echo time/repetition time = 28 ms/2,000 ms, flip angle = 77°, scan duration = 10m0s–10m6s, field of view = 220 mm, slices = 40 and slice thickness = 4.0 mm, and slices were obtained with whole‐brain coverage.

Preprocessing of images

Preprocessing and quality control was performed using Statistical Parametric Mapping‐8 (SPM8) software and involved bias field correction, coregistration, motion correction, spatial normalization, tissue segmentation and Fourier transformation for frequency distribution. Data were then spatially normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute template using the structural scans; previous studies suggest that this is adequate for reliable functional connectivity estimates 66, 67, 68. The average temporal signal‐to‐noise ratio was 50.4, as assessed by the MRIQC toolbox 69. A temporal signal‐to‐noise ratio of 50.4 is at least comparable with that in many published large‐scale studies 70.

Magnetic resonance imaging processing

Structural image parcellation

T1‐image segmentation and cortical and subcortical regional parcellation were conducted using freesurfer v.5.3.0 71, 72, 73 following the nomenclature described in the Destrieux and Harvard–Oxford subcortical atlas 74, 75. This parcellation results in the labelling of 165 regions, 74 bilateral cortical structures, seven subcortical structures, the midbrain and the cerebellum 76.

Functional brain construction

Functional brain networks were constructed as previously described 11. To summarize, linear measures of region‐to‐region functional connectivity (Pearson's correlations) were computed using the CONN toolbox 77. The resting‐state images were filtered using a bandpass filter (0.008/s < f < 0.08/s) to reduce the low‐frequency and high‐frequency noises. A component‐based noise correction method, aCompCor 77, was applied to remove nuisances for better sensitivity and specificity of the analysis. Six motion realignment parameters and their first‐order temporal derivatives along confounds for white matter and cerebrospinal fluid (based on aCompCor results) were removed using regression. Although the influence of head motion cannot be completely removed, aCompCor has been shown to be particularly effective for dealing with residual motion relative to other methods 78. The connectivity between the 165 brain regions was indexed by a matrix of Fisher z‐transformed correlation coefficients reflecting the association between average temporal BOLD time series signals across all voxels in each brain region. The connectivity matrix was then smoothed with a 4‐mm isotropic Gaussian kernel. Functional connections were retained at z > 0.3, and all other values were set to 0. The magnitude of the z‐score represents the weights in the functional network.

Brain regions of interest

Based on previous research 11, 79, 80, 81, regions of interest were restricted to core regions of the ‘reward network’ (basal ganglia: caudate, pallidum, nucleus accumbens and brainstem, including the substantia nigra [SN] and ventral tegmental area [VTA]) and the extended reward network, which includes the ‘emotional regulation network’ (amygdala, hippocampus, subgenual anterior cingulate cortex and anterior cingulate cortex [ACC]), the ‘salience network’ (anterior insula [aINS] and anterior mid‐cingulate cortex), the ‘executive control network’ (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex [dlPFC], ventrolateral prefrontal cortex [vlPFC], medial prefrontal cortex [mPFC] and orbital frontal gyrus [OFG]) and the ‘somatosensory network’ (putamen and thalamus) (Table 1, which contains a list of the regions and their Atlas labels).

Table 1.

Regions of interest from the Destrieux and Harvard–Oxford atlas

| Region | Full destrieux name | Destrieux abbreviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reward network | |||

| 1 | Basal ganglia | Caudate | CaN |

| Nucleus accumbens | NAcc | ||

| Pallidum | Pal | ||

| Ventral tegmental area/substantia nigra | VTA–SN | ||

| Emotional regulation network | |||

| 1 | Amygdala | Amygdala | Amg |

| 2 | Hippocampus | Hippocampus | Hip |

| 3 | ACC | Anterior part of the cingulate gyrus and sulcus | ACgG_S |

| 4 | sgACC | Subcallosal area and subcallosal gyrus | SbCaG |

| Salience network | |||

| 1 | aINS | Anterior segment of the circular sulcus of the insula | ACirIns |

| Horizontal ramus of the anterior segment of the lateral sulcus (or fissure) | ALSHorp | ||

| Vertical ramus of the anterior segment of the lateral sulcus (or fissure) | ALSVerp | ||

| Short insular gyri | ShoInG | ||

| Superior segment of the circular sulcus of the insula | SupCirInS | ||

| 2 | aMCC | Middle–anterior part of the cingulate gyrus and sulcus | MACgG_S |

| Executive control network | |||

| 1 | OFG | Medial orbital sulcus (olfactory sulcus) | MedOrS |

| Orbital gyri | OrG | ||

| 2 | dlPFC | Middle frontal gyrus (F2) | MFG |

| Inferior frontal sulcus | InfFS | ||

| 3 | vlPFC | Orbital part of the inferior frontal gyrus | InfFGOrp |

| Triangular part of the inferior frontal gyrus | InfFGTrip | ||

| 4 | mPFC | Transverse frontopolar gyri and sulci | TrFPoG_S |

| Straight gyrus and gyrus rectus | RG | ||

| Somatosensory network | |||

| 1 | Basal ganglia | Putamen | Pu |

| 2 | Thalamus | Thalamus | Tha |

Computing network metrics

The Graph Theory GLM toolbox (www.nitrc.org/projects/metalab_gtg) and in‐house matlab scripts were scripts were used to calculate and analyse the brain network properties and organization from the participant‐specific functional brain networks for the brain regions of interest. Regions with high centrality are highly influential, communicate with many other regions, facilitate functional integration and play a key role in network resilience to insult 48. Three indices of centrality were computed: (1) degree strength (DS) reflects the number of other regions a brain region interacts with functionally (local prominence), (2) betweenness centrality (BC) reflects the ability of a region to influence information flow (signalling) between two other regions and (3) eigenvector centrality (EC), where higher values indicate the region is directly connected to other highly connection regions reflective of the global (versus local) prominence of a region.

Statistical analysis

Tripartite network analysis was performed to integrate information from (1) ELA (ETI‐SR questionnaire), (2) food addiction (YFAS questionnaire) and (3) functional network metrics characterizing the centrality regions of interest. Spearman correlations were computed between all data types controlling for age and sex for between disease group comparisons and for age for within sex comparisons in matlab version R2015b. Results were adjusted for multiple testing using a false discovery rate of 5% and thresholded for significance at an adjusted p of q < 0.05. Next, nodes (ELA scores, YFAS scores and brain centrality metrics) and edges (significant z values) were imported into cytoscape v.3.5.1 for visualization. The layout results in nodes that are connected with similar associations grouped together. This technique allows one to see clusters or patterns in the data.

The results are described in terms of direct effects (nodes connected by an edge) or indirect effects (nodes that are connected to other regions via the edges of other nodes but that do not share an edge). The analysis presumes that associations present in one group, which are missing in another, not only differentiate the groups but also indicate potential clues to the functionality of the system; this approach has been used previously 58, 82. Comparisons were made between all the brain networks representing each group in order to identify desease and sex effects: (1) the high BMI group versus the normal BMI group (disease effect) and (2) the women with high BMI group versus the men with high BMI group (sex effect). Each group was examined in how the they differ in the areas of significant associations between ETI‐SR, brain connectivity and food addiction scores (YFAS).

Results

Participant characteristics

Participant characteristics are summarized in Tables 2A and 2B. Participants with high BMI (BMI ≥25 kg/m−2: mean BMI = 30.12, standard deviation [SD] = 4.51, range = 25.00–47.54 kg/m−2) consisted of 54 men (mean = 28.71, SD = 3.19, range = 25.00–37.68 kg/m−2) and 53 women (mean = 31.56, SD = 5.18, range = 25.09–47.54 kg/m−2). Of these participants, 65 were overweight (BMI = 25.00–29.99 kg/m−2; men = 40 and women = 25) and 42 were obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m−2; men = 14 and women = 28). Participants with normal BMI (BMI < 25 kg/m−2: mean BMI = 22.12, SD = 1.70, range = 17.90–24.88 kg/m−2) consisted of 30 men (mean = 22.46, SD = 1.65, range = 17.90–24.80 kg/m−2) and 49 women (mean = 21.91, SD = 1.71, range = 18.80–24.88 kg/m−2).

Table 2.

A.) Study demographics and clinical behavioural measures for individuals in the normal and high BMI groups. B.) Comparisons of study demographics and clinical behavioural measures

| Measurement | Normal BMI (<25) | ||||||||

| Men | Women | Total | |||||||

| N = 30 | N = 49 | N = 79 | |||||||

| Mean or count | SD or % | N | Mean or count | SD or % | N | Mean or count | SD or % | N | |

| Age (years) | 29.70 | 12.13 | 30 | 28.49 | 10.60 | 49 | 28.95 | 11.15 | 79 |

| BMI (kg/m−2) | 22.46 | 1.65 | 30 | 21.91 | 1.71 | 49 | 22.12 | 1.70 | 79 |

| SES | 5.43 | 2.15 | 7 | 5.83 | 1.27 | 12 | 5.68 | 1.60 | 19 |

| ETI | |||||||||

| General score | 1.53 | 1.72 | 30 | 1.31 | 1.26 | 48 | 1.40 | 1.44 | 78 |

| Physical score | 1.67 | 1.73 | 30 | 0.77 | 1.22 | 48 | 1.12 | 1.49 | 78 |

| Emotional score | 0.63 | 1.19 | 30 | 0.52 | 1.32 | 48 | 0.56 | 1.26 | 78 |

| Sexual score | 0.07 | 0.25 | 30 | 0.25 | 0.67 | 48 | 0.18 | 0.55 | 78 |

| Total score | 3.90 | 3.58 | 30 | 2.85 | 2.96 | 48 | 3.26 | 3.23 | 78 |

| YFAS | |||||||||

| YFAS score | 1.70 | 0.95 | 10 | 2.29 | 1.07 | 14 | 2.04 | 1.04 | 24 |

| Measurement | High BMI (>25) | ||||||||

| Men | Women | Total | |||||||

| N = 54 | N = 53 | N = 107 | |||||||

| Mean or Count | SD or % | N | Mean or count | SD or % | N | Mean or count | SD or % | N | |

| Age (years) | 34.33 | 12.59 | 54 | 32.49 | 8.69 | 53 | 33.42 | 10.83 | 107 |

| BMI (kg/m−2) | 28.71 | 3.19 | 54 | 31.55 | 5.18 | 53 | 30.12 | 4.51 | 107 |

| SES | 6.11 | 2.19 | 18 | 5.95 | 1.08 | 42 | 6.00 | 1.48 | 60 |

| ETI | |||||||||

| General score | 1.60 | 1.71 | 53 | 1.85 | 1.85 | 53 | 1.73 | 1.78 | 106 |

| Physical score | 1.54 | 1.70 | 52 | 1.45 | 1.46 | 53 | 1.50 | 1.58 | 105 |

| Emotional score | 0.98 | 1.61 | 52 | 1.21 | 1.74 | 53 | 1.10 | 1.67 | 105 |

| Sexual score | 0.21 | 0.80 | 52 | 0.72 | 1.34 | 53 | 0.47 | 1.13 | 105 |

| Total score | 4.41 | 4.34 | 51 | 5.23 | 4.73 | 53 | 4.83 | 4.54 | 104 |

| YFAS | |||||||||

| YFAS score | 4.00 | 4.70 | 21 | 3.98 | 2.55 | 42 | 3.98 | 3.38 | 63 |

| Measurement | High BMI vs. normal BMI | ||||||||

| t | d.f. | p | |||||||

| Age (years) | 2.66 | 183 | <0.001 | ||||||

| SES | −0.76 | 77 | 0.452 | ||||||

| ETI | |||||||||

| General score | 1.24 | 181 | 0.769 | ||||||

| Physical score | 1.04 | 180 | 0.873 | ||||||

| Emotional score | 2.26 | 180 | 0.179 | ||||||

| Sexual score | 2.24 | 180 | 0.186 | ||||||

| Total score | 2.33 | 179 | 0.153 | ||||||

| YFAS | |||||||||

| YFAS score | 2.59 | 84 | 0.088 | ||||||

| Measurement | Men with high BMI vs. women with high BMI | ||||||||

| t | d.f. | p | |||||||

| Age (years) | 0.89 | 105 | 0.375 | ||||||

| SES | 0.29 | 58 | 0.770 | ||||||

| ETI | |||||||||

| General score | −0.65 | 104 | 0.982 | ||||||

| Physical score | 0.15 | 103 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Emotional score | −0.46 | 103 | 0.996 | ||||||

| Sexual score | −2.45 | 103 | 0.118 | ||||||

| Total score | −0.79 | 102 | 0.956 | ||||||

| YFAS | |||||||||

| YFAS score | −0.02 | 61 | 1.000 | ||||||

BMI, body mass index; ETI, Early Traumatic Inventory; SD, standard deviation; SES, socio‐economic status; YFAS, Yale Food Addiction Survey.

Participants with high BMI reported higher scores on ETI‐SR general (p = 0.02), emotional (p = 0.0006) and total (p = 0.00007). Although there were no significant differences in YFAS scores among the groups, men and women with high BMI, on average, showed higher scores than men and women with normal BMI (4.00 and 3.98 vs. 1.70 and 2.29, respectively). Similarly, all participants with high BMI, regardless of sex, had higher levels of YFAS than participants with normal BMI (3.98 vs. 2.04, respectively). A total of 17.4% of participants with high BMI reported a diagnostic (≥3) YFAS score, compared with 0% of participants with normal BMI (p = 0.032). A total of 8.0% of men with high BMI reported a diagnostic YFAS score, compared with 22.7% of women with high BMI (p = 0.188). There were no significant differences in subjective socio‐economic status among any of the groups.

Comparing the association networks of the high body mass index group with the normal body mass index group

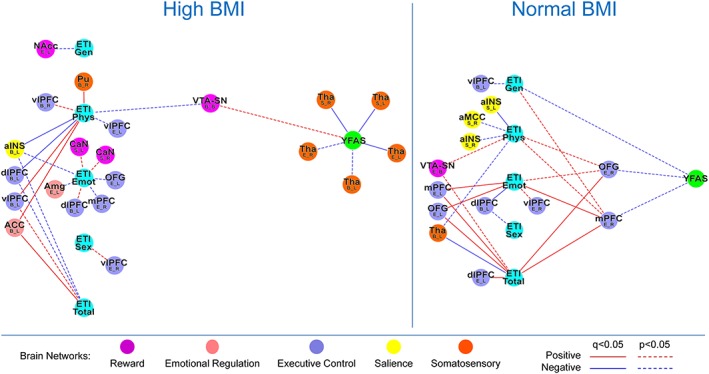

Results are summarized in Tables 3 and 4 and depicted in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Tripartite associations (all significant association for the high BMI, normal BMI, women with high BMI, and men with high BMI groups)

| High BMI | ||||||

| Functional connectivity region | Network | Network metric | r | p | q | d.f. |

| ETI | ||||||

| General (ETI) | ||||||

| Left nucleus accumbens | Reward | Eigenvector centrality | −0.21158 | 0.03108 | 0.12432 | 105 |

| Physical (ETI) | ||||||

| VTA–SN | Reward | Betweenness centrality | −0.22425 | 0.02277 | 0.09109 | 104 |

| Left ACC (ACgG_S) | Emotional regulation | Betweenness centrality | 0.25437 | 0.00952 | 0.03807 | 104 |

| Left aINS (ALSHorp) | Salience | Betweenness centrality | −0.24943 | 0.01106 | 0.04424 | 104 |

| Left dlPFC (InfFS) | Executive control | Betweenness centrality | −0.23944 | 0.01486 | 0.04457 | 104 |

| Left vlPFC (InfFGOrp) | Executive control | Betweenness centrality | 0.25144 | 0.01041 | 0.04457 | 104 |

| Right vlPFC (InfFGOrp) | Executive control | Betweenness centrality | 0.22067 | 0.02510 | 0.15058 | 104 |

| Left vlPFC (InfFGTrip) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | −0.20013 | 0.04268 | 0.25606 | 104 |

| Right putamen | Somatosensory | Betweenness centrality | 0.25644 | 0.00893 | 0.01786 | 104 |

| Emotional (ETI) | ||||||

| Left caudate | Reward | Strength | 0.23053 | 0.01914 | 0.07658 | 104 |

| Right caudate | Reward | Strength | 0.21073 | 0.03263 | 0.09788 | 104 |

| Left amygdala | Emotional regulation | Eigenvector centrality | −0.22497 | 0.02233 | 0.08933 | 104 |

| Left aINS (ALSHorp) | Salience | Betweenness centrality | −0.20663 | 0.03625 | 0.14501 | 104 |

| Left OFG (OrG) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | −0.25464 | 0.00944 | 0.05664 | 104 |

| Right mPFC (TrFPoG_S) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | −0.19674 | 0.04639 | 0.23541 | 104 |

| Left dlPFC (MFG) | Executive control | Betweenness centrality | 0.19392 | 0.04967 | 0.29803 | 104 |

| Sexual (ETI) | ||||||

| Right vlPFC (InfFGTrip) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | 0.19944 | 0.04341 | 0.26047 | 104 |

| Total (ETI) | ||||||

| Left ACC (ACgG_S) | Emotional regulation | Betweenness centrality | 0.25688 | 0.00915 | 0.03661 | 103 |

| Left aINS (ALSHorp) | Salience | Betweenness centrality | −0.21341 | 0.03127 | 0.12506 | 103 |

| Left dlPFC (InfFS) | Executive control | Betweenness centrality | −0.20259 | 0.04114 | 0.12343 | 103 |

| Left vlPFC (InfFGOrp) | Executive control | Betweenness centrality | 0.23843 | 0.01581 | 0.09485 | 103 |

| YFAS | ||||||

| VTA–SN | Reward | Betweenness centrality | 0.28396 | 0.01987 | 0.07950 | 68 |

| Left thalamus | Somatosensory | Betweenness centrality | −0.26677 | 0.02909 | 0.05819 | 68 |

| Left thalamus | Somatosensory | Eigenvector centrality | −0.27464 | 0.02450 | 0.04900 | 68 |

| Right thalamus | Somatosensory | Eigenvector centrality | −0.25214 | 0.03955 | 0.07911 | 68 |

| Left thalamus | Somatosensory | Strength | −0.37559 | 0.00174 | 0.00347 | 68 |

| Right thalamus | Somatosensory | Strength | −0.35845 | 0.00290 | 0.00579 | 68 |

| Normal BMI | ||||||

| Functional connectivity region | Network | Network metric | r | p | q | d.f. |

| ETI | ||||||

| General (ETI) | ||||||

| Left vlPFC (InfFGOrp) | Executive control | Betweenness centrality | −0.25546 | 0.02593 | 0.15558 | 77 |

| Right mPFC (TrFPoG_S) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | 0.28340 | 0.01311 | 0.07867 | 77 |

| YFAS | −0.43797 | 0.03231 | 0.19386 | 25 | ||

| Physical (ETI) | ||||||

| VTA–SN | Reward | Eigenvector centrality | 0.28254 | 0.01340 | 0.05361 | 77 |

| Left aINS (ACirIns) | Salience | Strength | −0.30798 | 0.00680 | 0.02720 | 77 |

| Right aINS (ShoInG) | Salience | Strength | −0.27447 | 0.01642 | 0.06569 | 77 |

| Right MACC (ACgG_S) | Salience | Strength | −0.22919 | 0.04643 | 0.08517 | 77 |

| Right OFG (OrG) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | 0.25668 | 0.02521 | 0.07562 | 77 |

| Right mPFC (TrFPoG_S) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | 0.26485 | 0.02077 | 0.07562 | 77 |

| Left thalamus | Somatosensory | Betweenness centrality | −0.25321 | 0.02732 | 0.05464 | 77 |

| Emotional (ETI) | ||||||

| Left OFG (OrG) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | 0.31112 | 0.00623 | 0.02331 | 77 |

| Right OFG (OrG) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | 0.25295 | 0.02748 | 0.06028 | 77 |

| Left dlPFC (InfFS) | Executive control | Betweenness centrality | −0.31798 | 0.00512 | 0.03074 | 77 |

| Right vlPFC (InfFGTrip) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | 0.24891 | 0.03014 | 0.06028 | 77 |

| Left mPFC (TrFPoG_S) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | 0.30315 | 0.00777 | 0.02331 | 77 |

| Right mPFC (TrFPoG_S) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | 0.32717 | 0.00392 | 0.02350 | 77 |

| Sexual (ETI) | ||||||

| Left dlPFC (InfFS) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | −0.27239 | 0.01729 | 0.10374 | 77 |

| Total (ETI) | ||||||

| VTA–SN | Reward | Eigenvector centrality | 0.23457 | 0.04139 | 0.16556 | 77 |

| Right OFG (OrG) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | 0.37108 | 0.00097 | 0.00290 | 77 |

| Left OFG (OrG) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | 0.34240 | 0.00246 | 0.01479 | 77 |

| Left dlPFC (MFG) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | 0.30315 | 0.00777 | 0.02331 | 77 |

| Left mPFC (TrFPoG_S) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | 0.25798 | 0.02445 | 0.04891 | 77 |

| Right mPFC (TrFPoG_S) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | 0.39134 | 0.00047 | 0.00284 | 77 |

| Left thalamus | Somatosensory | Betweenness centrality | −0.27569 | 0.01593 | 0.03186 | 77 |

| YFAS | ||||||

| Right OFG (OrG) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | −0.43718 | 0.03266 | 0.10019 | 25 |

| Right mPFC (TrFPoG_S) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | −0.42578 | 0.03804 | 0.10019 | 25 |

| Women with High BMI | ||||||

| Functional connectivity region | Network | Network metric | r | p | q | d.f. |

| ETI | ||||||

| General (ETI) | ||||||

| Right caudate | Reward | Eigenvector centrality | 0.27956 | 0.02473 | 0.03710 | 52 |

| Right nucleus accumbens | Reward | Eigenvector centrality | 0.34203 | 0.01307 | 0.03710 | 52 |

| Left aINS (ALSHorp) | Salience | Betweenness centrality | −0.28469 | 0.04080 | 0.16321 | 52 |

| Physical (ETI) | ||||||

| Left aINS (ALSHorp) | Salience | Betweenness centrality | −0.28425 | 0.00112 | 0.00449 | 52 |

| Left putamen | Somatosensory | Strength | 0.35131 | 0.01066 | 0.02131 | 52 |

| Right putamen | Somatosensory | Strength | 0.32796 | 0.01762 | 0.03524 | 52 |

| Emotional (ETI) | ||||||

| Right nucleus accumbens | Reward | Eigenvector centrality | 0.27592 | 0.00771 | 0.02313 | 52 |

| Left ACC (ACgG_S) | Emotional regulation | Eigenvector centrality | 0.28694 | 0.01916 | 0.03833 | 52 |

| Right ACC (ACgG_S) | Emotional regulation | Eigenvector centrality | 0.30690 | 0.00690 | 0.02759 | 52 |

| Left sgACC (SbCaG) | Emotional regulation | Eigenvector centrality | 0.29556 | 0.01340 | 0.03833 | 52 |

| Left aINS (ALSHorp) | Salience | Betweenness centrality | −0.29431 | 0.00419 | 0.01675 | 52 |

| Sexual (ETI) | ||||||

| Right aINS (ALSHorp) | Salience | Betweenness centrality | 0.31814 | 0.02154 | 0.08615 | 52 |

| Total (ETI) | ||||||

| Right nucleus accumbens | Reward | Eigenvector centrality | 0.28201 | 0.02282 | 0.06845 | 52 |

| Left aINS (ALSHorp) | Salience | Betweenness centrality | −0.29581 | 0.03324 | 0.13295 | 52 |

| Left putamen | Somatosensory | Strength | 0.30922 | 0.02571 | 0.05142 | 52 |

| Right putamen | Somatosensory | Strength | 0.29247 | 0.03538 | 0.07075 | 52 |

| YFAS | ||||||

| VTA–SN | Reward | Betweenness centrality | 0.38368 | 0.01109 | 0.04436 | 43 |

| Right dlPFC (InfFS) | Executive control | Betweenness centrality | −0.33333 | 0.00894 | 0.05366 | 43 |

| Left vlPFC (InfFGTrip) | Executive control | Betweenness centrality | −0.31484 | 0.00575 | 0.03449 | 43 |

| Right mPFC (TrFPoG_S) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | 0.36598 | 0.01580 | 0.09478 | 43 |

| Left thalamus | Somatosensory | Betweenness centrality | −0.39129 | 0.00947 | 0.01894 | 43 |

| Men with High BMI | ||||||

| Functional connectivity region | Network | Network metric | r | p | q | d.f. |

| ETI | ||||||

| General (ETI) | ||||||

| Left amygdala | Emotional regulation | Betweenness centrality | 0.34465 | 0.01235 | 0.04939 | 52 |

| Physical (ETI) | ||||||

| Right caudate | Reward | Eigenvector centrality | 0.30781 | 0.02799 | 0.08398 | 51 |

| Left nucleus accumbens | Reward | Betweenness centrality | −0.30109 | 0.03179 | 0.12718 | 51 |

| Left hippocampus | Emotional regulation | Strength | −0.28141 | 0.04545 | 0.18179 | 51 |

| Left dlPFC (InfFS) | Executive control | Betweenness centrality | −0.33094 | 0.01769 | 0.05306 | 51 |

| Left vlPFC (InfFGOrp) | Executive control | Betweenness centrality | 0.34037 | 0.01453 | 0.05306 | 51 |

| Right vlPFC (InfFGOrp) | Executive control | Betweenness centrality | 0.36065 | 0.00933 | 0.05596 | 51 |

| Left vlPFC (InfFGTrip) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | −0.37116 | 0.00733 | 0.04399 | 51 |

| Left vlPFC (InfFGTrip) | Executive control | Strength | −0.30609 | 0.02893 | 0.17356 | 51 |

| Emotional (ETI) | ||||||

| Right caudate | Reward | Strength | 0.29087 | 0.03839 | 0.11516 | 51 |

| Left OFG (OrG) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | −0.33562 | 0.01606 | 0.09633 | 51 |

| Sexual (ETI) | ||||||

| Left caudate | Reward | Strength | 0.30712 | 0.02837 | 0.05674 | 51 |

| Right caudate | Reward | Strength | 0.30599 | 0.02898 | 0.08695 | 51 |

| Left pallidum | Reward | Eigenvector centrality | 0.30104 | 0.03182 | 0.12730 | 51 |

| Left pallidum | Reward | Strength | 0.31946 | 0.02231 | 0.05674 | 51 |

| Left aINS (ACirIns) | Salience | Betweenness centrality | −0.29324 | 0.03676 | 0.14706 | 51 |

| Left dlPFC (MFG) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | 0.29915 | 0.03297 | 0.19781 | 51 |

| Left dlPFC (MFG) | Executive control | Strength | 0.28943 | 0.03940 | 0.12281 | 51 |

| Right vlPFC (InfFGTrip) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | 0.33575 | 0.01601 | 0.09607 | 51 |

| Right vlPFC (InfFGTrip) | Executive control | Strength | 0.30069 | 0.03203 | 0.14355 | 51 |

| Left mPFC (TrFPoG_S) | Executive control | Strength | 0.28730 | 0.04094 | 0.12281 | 51 |

| Left thalamus | Somatosensory | Strength | 0.31168 | 0.02599 | 0.05197 | 51 |

| Right thalamus | Somatosensory | Strength | 0.36990 | 0.00755 | 0.01510 | 51 |

| YFAS | −0.49862 | 0.01545 | 0.09267 | 23 | ||

| Total (ETI) | ||||||

| Right caudate | Reward | Eigenvector centrality | 0.36146 | 0.00991 | 0.02972 | 50 |

| Right caudate | Reward | Strength | 0.28914 | 0.04170 | 0.12509 | 50 |

| Left dlPFC (InfFS) | Executive control | Betweenness centrality | −0.28229 | 0.04701 | 0.14103 | 50 |

| Left vlPFC (InfFGOrp) | Executive control | Betweenness centrality | 0.30287 | 0.03252 | 0.14103 | 50 |

| Right vlPFC (InfFGOrp) | EXecutive control | Betweenness centrality | 0.29583 | 0.03699 | 0.22195 | 50 |

| Left vlPFC (InfFGTrip) | Executive control | Eigenvector centrality | −0.30251 | 0.03274 | 0.19642 | 50 |

| YFAS | ||||||

| VTA–SN | Reward | Eigenvector centrality | −0.51955 | 0.00927 | 0.03708 | 24 |

| VTA–SN | Reward | Strength | −0.59150 | 0.00233 | 0.00933 | 24 |

| Left hippocampus | Emotional regulation | Betweenness centrality | 0.68360 | 0.00023 | 0.00092 | 24 |

| Left ACC (ACgG_S) | Emotional regulation | Eigenvector centrality | −0.44378 | 0.02983 | 0.11933 | 24 |

| Right ACC (ACgG_S) | Emotional regulation | Eigenvector centrality | −0.46504 | 0.02203 | 0.08814 | 24 |

| Left ACC (ACgG_S) | Emotional regulation | Strength | −0.46347 | 0.02255 | 0.05417 | 24 |

| Right ACC (ACgG_S) | Emotional regulation | Strength | −0.49237 | 0.01452 | 0.05808 | 24 |

| Left sgACC (SbCaG) | Emotional regulation | Strength | −0.45070 | 0.02709 | 0.05417 | 24 |

| Right aINS (ShoInG) | Salience | Strength | −0.42519 | 0.03834 | 0.07667 | 24 |

| Left MACC (ACgG_S) | Salience | Eigenvector centrality | −0.47111 | 0.02014 | 0.08056 | 24 |

| Left MACC (ACgG_S) | Salience | Strength | −0.52871 | 0.00790 | 0.03161 | 24 |

| Right MACC (ACgG_S) | Salience | Strength | −0.61368 | 0.00143 | 0.00570 | 24 |

| Left OFG (OrG) | Executive control | Betweenness centrality | 0.49154 | 0.01471 | 0.04413 | 24 |

| Right dlPFC (MFG) | Executive control | Strength | −0.52306 | 0.00872 | 0.05234 | 24 |

| Right vlPFC (InfFGOrp) | Executive control | Strength | −0.41754 | 0.04234 | 0.12703 | 24 |

| Left vlPFC (InfFGTrip) | Executive control | Betweenness centrality | 0.50666 | 0.01152 | 0.04413 | 24 |

| Right putamen | Somatosensory | Strength | −0.43769 | 0.03243 | 0.03243 | 24 |

| Right thalamus | Somatosensory | Betweenness centrality | 0.44878 | 0.02783 | 0.05566 | 24 |

| Left thalamus | Somatosensory | Eigenvector centrality | −0.50496 | 0.01185 | 0.02369 | 24 |

| Right thalamus | Somatosensory | Eigenvector centrality | −0.43718 | 0.03266 | 0.06532 | 24 |

| Left thalamus | Somatosensory | Strength | −0.58316 | 0.00278 | 0.00556 | 24 |

| Right thalamus | Somatosensory | Strength | −0.53695 | 0.00682 | 0.01364 | 24 |

This table summarizes the key findings from Table 3, comparing disease effect (high BMI group vs. normal BMI group) and sex effect (women with high BMI group vs. men with high BMI group). Cells highlighted in grey represent that at least one association remained significant following multiple hypothesis correction (q < 0.05).

BMI, body mass index; ETI, Early Traumatic Inventory; YFAS, Yale Food Addiction Survey.

Table 4.

Summary of adverse life event–brain associations

| Functional connectivity region | High BMI vs. normal BMI | Women with high BMI vs. men with high BMI |

|---|---|---|

| Reward network | ||

| General (ETI) | ||

| Left caudate | ||

| Right caudate | Women with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Left nucleus accumbens | High BMI: ↓ | |

| Right nucleus accumbens | Women with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Physical (ETI) | ||

| Right caudate | Men with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Left nucleus accumbens | Men with high BMI: ↓ | |

| VTA–SN |

High BMI: ↓ Normal BMI: ↑ |

|

| Emotional (ETI) | ||

| Left caudate | High BMI: ↑ | |

| Right caudate | High BMI: ↑ | Men with high BMI: ↑ |

| Right nucleus accumbens | Women with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Sexual (ETI) | ||

| Left caudate | Men with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Right caudate | Men with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Left pallidum | Men with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Total (ETI) | ||

| Right caudate | Men with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Right nucleus accumbens | Women with high BMI: ↑ | |

| VTA–SN | Normal BMI: ↑ | |

| YFAS | ||

| Left caudate | ||

| Right nucleus accumbens | ||

| VTA–SN | High BMI: ↑ |

Women with high BMI: ↑ Men with high BMI: ↓ |

| Emotional regulation network | ||

| General (ETI) | ||

| Left amygdala | Men with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Left sgACC | ||

| Physical (ETI) | ||

| Left amygdala | ||

| Right amygdala | ||

| Left hippocampus | Men with high BMI: ↓ | |

| Left ACC | High BMI: ↑ | |

| Left sgACC | ||

| Emotional (ETI) | ||

| Left amygdala | High BMI: ↓ | |

| Right amygdala | ||

| Left ACC | Women with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Right ACC | Women with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Left sgACC | Women with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Sexual (ETI) | ||

| Left sgACC | ||

| Right sgACC | ||

| Total (ETI) | ||

| Left amygdala | ||

| Left ACC | High BMI: ↑ | |

| YFAS | ||

| Left hippocampus | Men with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Right hippocampus | ||

| Left ACC | Men with high BMI: ↓ | |

| Right ACC | Men with high BMI: ↓ | |

| Left sgACC | Men with high BMI: ↓ | |

| Salience network | ||

| General (ETI) | ||

| Left aINS | Women with high BMI: ↓ | |

| Right aINS | ||

| Physical (ETI) | ||

| Left aINS |

High BMI: ↓ Normal BMI: ↓ |

Women with high BMI: ↓ |

| Right aINS | Normal BMI: ↓ | |

| Right aMCC | Normal BMI: ↓ | |

| Emotional (ETI) | ||

| Left aINS | High BMI: ↓ | Women with high BMI: ↓ |

| Sexual (ETI) | ||

| Left aINS | Men with high BMI: ↓ | |

| Right aINS | Women with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Total (ETI) | ||

| Left aINS | High BMI: ↓ | Women with high BMI: ↓ |

| YFAS | ||

| Left aINS | ||

| Right aINS | Men with high BMI: ↓ | |

| Left aMCC | Men with high BMI: ↓ | |

| Right aMCC | Men with high BMI: ↓ | |

| Executive control network | ||

| General (ETI) | ||

| Left vlPFC | Normal BMI: ↓ | |

| Right vlPFC | ||

| Right mPFC | ||

| Physical (ETI) | ||

| Right OFG | Normal BMI: ↑ | |

| Left dlPFC | High BMI: ↓ | Men with high BMI: ↓ |

| Right dlPFC | ||

| Left vlPFC | High BMI: ↑ | Men with high BMI: ↓ |

| Right vlPFC | High BMI: ↑ | Men with high BMI: ↑ |

| Right mPFC | Normal BMI: ↑ | |

| Emotional (ETI) | ||

| Left OFG |

High BMI: ↓ Normal BMI: ↑ |

Men with high BMI: ↓ |

| Right OFG | Normal BMI: ↑ | |

| Left dlPFC |

High BMI: ↑ Normal BMI: ↓ |

|

| Right vlPFC | Normal BMI: ↑ | |

| Left mPFC | Normal BMI: ↑ | |

| Right mPFC |

High BMI: ↓ Normal BMI: ↑ |

|

| Sexual (ETI) | ||

| Left dlPFC | Normal BMI: ↓ | Men with high BMI: ↑ |

| Right vlPFC | High BMI: ↑ | Men with high BMI: ↑ |

| Left mPFC | Men with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Total (ETI) | ||

| Left OFG | Normal BMI: ↑ | |

| Right OFG | Normal BMI: ↑ | |

| Left dlPFC |

High BMI: ↓ Normal BMI: ↑ |

Men with high BMI: ↓ |

| Left vlPFC | High BMI: ↑ | Men with high BMI: ↓ |

| Right vlPFC | Men with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Left mPFC | Normal BMI: ↑ | |

| Right mPFC | Normal BMI: ↑ | |

| YFAS | ||

| Left OFG | Men with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Right dlPFC |

Women with high BMI: ↓ Men with high BMI: ↓ |

|

| Left vlPFC |

Women with high BMI: ↓ Men with high BMI: ↑ |

|

| Right vlPFC | Men with high BMI: ↓ | |

| Right mPFC | Women with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Somatosensory network | ||

| General (ETI) | ||

| Right putamen | ||

| Physical (ETI) | ||

| Left putamen | Women with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Right putamen | High BMI: ↑ | Women with high BMI: ↑ |

| Left thalamus | Normal BMI: ↓ | |

| Sexual (ETI) | ||

| Right putamen | ||

| Left thalamus | Men with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Right thalamus | Men with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Total (ETI) | ||

| Left putamen | Women with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Right putamen | Women with high BMI: ↑ | |

| Left thalamus | Normal BMI: ↓ | |

| YFAS | ||

| Left putamen | ||

| Right putamen | Men with high BMI: ↓ | |

| Left thalamus | High BMI: ↓ |

Women with high BMI: ↓ Men with high BMI: ↓ |

| Right thalamus | High BMI: ↓ | Men with high BMI: ↓ |

BMI, body mass index; ETI, Early Traumatic Inventory; YFAS, Yale Food Addiction Survey.

Figure 1.

Tripartite association network of the high body mass index (BMI) and normal BMI groups. This figure demonstrates the tripartite association network of the high BMI and normal BMI groups to underscore disease effect. Functional brain connectivity of regions of interest is presented with the region of interested noted in a larger font, with the connectivity measure and lateralization indicated below in the form X_Y, where X indicated a connectivity measure (B, betweenness centrality; E; eigenvector centrality; S, degree strength) and Y indicates lateralization (B, bilateral; L, left; R, right). ACC, anterior cingulate; aINS, anterior insula; Amg, amygdala; CaN, caudate; dlPFC, dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex; ETI Emot, early traumatic inventory subscale emotion score; ETI Gen, early traumatic inventory subscale general scores; ETI Phys, early traumatic inventory subscale physical scores; ETI Sex, early traumatic inventory subscale sex scores; ETI Total, early traumatic inventory subscale total scores; mPFC, medial prefrontal cortex; NAcc, nucleus accumbens; OFG, orbital frontal gyrus; Pu, putamen; Tha, thalamus; vlPFC, ventral lateral prefrontal cortex; VTA–SN, ventral tegmental area/substantia nigra; YFAS, Yale Food Addiction Survey.

Impact of early life adversity

Only the normal BMI group showed numerous positive associations between ETI‐SR total score and centrality of brain regions in the executive control network: left dlPFC (EC: r = 0.30, q = 0.02), bilateral OFG (EC left: r = 0.34, q = 0.02; EC right: r = 0.37, q = 0.003) and bilateral mPFC (EC left: r = 0.26, q = 0.049; EC right: r = 0.39, q = 0.003). No significant associations were found in the high BMI group with centrality of executive control regions.

The normal BMI group also showed a negative association between ETI‐SR total and centrality of a somatosensory region: left thalamus (BC: r = −0.28, q = 0.03). In contrast, the high BMI group showed a positive association between ETI‐SR physical and centrality of a different region of the somatosensory network: right putamen (BC: r = 0.26, q = 0.02). Both groups showed negative associations between ETI‐SR physical and centrality of the left aINS (high BMI BC: r = −0.25, q = 0.04; normal BMI DS: r = −0.31, q = 0.03).

Associations of brain networks with food addiction scores

Compared with the normal BMI group, those with high BMI showed negative associations between YFAS and centrality of bilateral thalamus (DS right: r = −0.36, q = 0.006; DS left: r = −0.38, q = 0.003; and EC left: r = −0.27, q = 0.049).

Association of early life adversity with alterations in the extended reward network and with food addiction

The high BMI group showed an indirect association between ELA and food addiction scores through centrality of VTA–SN (ETI‐SR physical BC VTA–SN: r = −0.22, p = 0.02; BC VTA–SN‐YFAS: r = 0.28, p = 0.02). The normal BMI group showed numerous indirect associations between numerous indices of ELA with food addiction through centrality of right mPFC (ETI‐SR total EC mPFC: r = 0.39, q = 0.003; ETI‐SR emotional EC mPFC: r = 0.33, q = 0.02; ETI‐SR physical EC mPFC: r = 0.26, p = 0.02; ETI‐SR general EC mPFC: r = 0.28, p = 0.01; and EC mPFC‐YFAS: r = −0.43, p = 0.04) and right OFG (ETI‐SR total EC OFG: r = 0.37, q = 0.003; ETI‐SR emotional EC OFG: r = 0.25, p = 0.03; ETI‐SR physical EC OFG: r = 0.26, p = 0.03; and EC OFG‐YFAS: r = −0.44, p = 0.03). This group also showed a direct negative association between ETI‐SR general trauma score and food addiction (r = −0.44, p = 0.03).

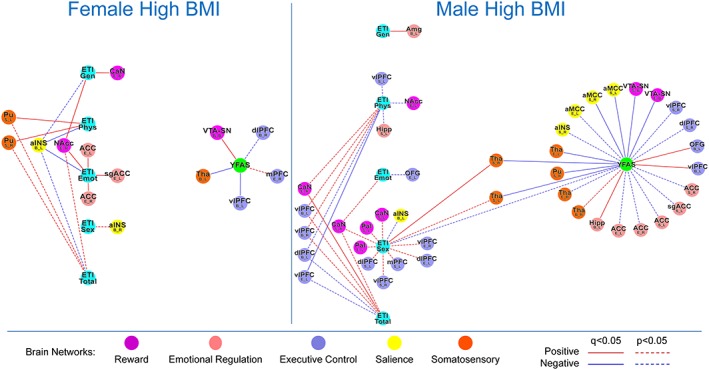

Comparing the association networks of women with high body mass index with men with high body mass index

Results are summarized in Tables 3 and 4 and depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Tripartite association network of the women with high body mass index (BMI) and men with high BMI groups. This figure demonstrates the tripartite association network of the women with high BMI and men with high BMI groups to underscore sex effect. Functional brain connectivity of regions of interest is presented with the region of interested noted in a larger font, with the connectivity measure and lateralization indicated below in the form X_Y, where X indicated a connectivity measure (B, betweenness centrality; E; eigenvector centrality; S, degree strength) and Y indicates lateralization (B, bilateral; L, left; R, right). ACC, anterior cingulate; aINS, anterior insula; aMCC, middle anterior cingulate; Amg, amygdala; CaN, caudate; dlPFC, dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex; ETI Emot, early traumatic inventory subscale emotion score; ETI Gen, early traumatic inventory subscale general scores; ETI Phys, early traumatic inventory subscale physical scores; ETI Sex, early traumatic inventory subscale sex scores; ETI Total, early traumatic inventory subscale total scores; Hipp, hippocampus; mPFC, medial prefrontal cortex; NAcc, nucleus accumbens; OFG, orbital frontal gyrus; Pal, pallidum; Pu, putamen; sgACC, subgenual anterior cingulate; Tha, thalamus; vlPFC, ventral lateral prefrontal cortex; VTA–SN, ventral tegmental area/substantia nigra; YFAS, Yale Food Addiction Survey.

Impact of early life adversity

Both men and women with high BMI showed positive associations between ETI‐SR and centrality of reward regions: right caudate (men | ETI‐SR total: EC r = 0.36, q = 0.03; women | ETI‐SR general: EC: r = 0.28, q = 0.04) and right nucleus accumbens (women | ETI‐SR emotional: EC: r = 0.28, q = 0.02; women| ETI‐SR general: EC: r = 0.34, q = 0.04). Similarly, both groups also showed positive associations between ETI‐SR and centrality of emotion regulation regions: bilateral ACC (women | ETI‐SR emotional: EC left: r = 0.29, q = 0.04; EC right: r = 0.31, q = 0.03), left subgenual ACC (women | ETI‐SR emotional: EC: r = 0.30, q = 0.04) and left amygdala (men | ETI‐SR general: BC: r = 0.34, q = 0.049). Both groups also showed positive associations between ETI‐SR and centrality of somatosensory regions: right thalamus (men|ETI‐SR sexual: DS: r = 0.37, q = 0.02) and bilateral putamen (women| ETI‐SR physical: DS left: r = 0.35, q = 0.02; DS right: r = 0.33, q = 0.04). Only the men with high BMI showed a negative association between ETI‐SR physical and centrality of an executive control region: left vlPFC (EC: r = −0.37, q = 0.04), while no significant associations were found in the women with high BMI with centrality of executive control regions.

Associations of brain networks with food addiction scores

Women showed a positive association between YFAS and centrality of VTA–SN (BC: r = 0.38, q = 0.04), while men showed negative associations between YFAS and centrality of the same reward region (DS: r = −0.59, q = 0.009; EC: r = −0.52, q = 0.04). Women showed a negative association between YFAS and centrality of left vlPFC (BC: r = −0.31, q = 0.03). In contrast, men group showed positive associations between YFAS and centrality of the same executive control region (BC: r = 0.51, q = 0.04) and left OFG (BC: r = 0.49, q = 0.04).

Only male participants showed a positive association between YFAS and centrality of emotional regulation and salience regions: left hippocampus (BC: r = 0.68, q = 0.0009) and bilateral anterior mid‐cingulate cortex (left DS: r = −0.53, q = 0.03; right DS: r = −0.61, q = 0.006). Both men and women showed negative association between YFAS and centrality of somatosensory regions: left thalamus (women BC: r = −0.39, q = 0.02; men EC: r = −0.50, q = 0.02; and men left DS: r = −0.58, q = 0.006), right thalamus (men DS: r = −0.54, q = 0.01) and right putamen (men DS: r = −0.44, q = 0.03).

Early life adversity is associated with alterations in the extended reward network and with food addiction

Men showed an indirect association between ELA and food addiction through centrality of right thalamus (ETI‐SR sexual DS right thalamus: r = 0.37, q = 0.02; DS right thalamus YFAS: r = −0.54, q = 0.01) and left thalamus (ETI‐SR sexual DS left thalamus: r = 0.31, p = 0.03; DS left thalamus YFAS: r = −0.58, q = 0.006).

Discussion

The goal of the current study was to investigate the association of ELA with measures of connectivity in the core and extended reward network of the brain and with a measure of food addiction. In addition, this study aimed to determine if these associations differ according to sex. Individuals with high BMI had positive associations of ELA with centrality of emotion regulation regions; these associations were accompanied by increased food addiction scores. Participants with normal BMI showed positive associations between ELA and centrality of executive control regions. BMI‐related differences are influenced by sex; women with high BMI showed positive associations between ELA and centrality of reward regions, emotion regulation regions and food addiction scores. Men with high BMI showed associations of ELA with food addiction through centrality of somatosensory regions. These results support the hypothesis that ELA events during childhood may alter connectivity of brain regions in the extended reward network, perhaps contributing to increased vulnerability for food addiction and obesity in adulthood, with these vulnerabilities differing by sex. This is the first study to investigate the role of ELA on brain networks, obesity and food addiction within the context of a comprehensive, systems biology based model that integrates sex differences.

Higher levels of ELA (physical and total) were positively associated with both emotion regulation (amygdala and ACC) and somatosensory (putamen) regions. In contrast, negative associations were observed with salience (aINS) and executive control (dlPFC) regions. In comparison, individuals with normal BMI had positive associations between ELA (emotional and total) and executive control regions (mPFC) and negative associations with ELA (physical and total) and salience (aINS) and somatosensory (thalamus) regions. The study hypotheses, though, were only partially supported as the positive association between ELA and centrality in reward regions in participants with high BMI did not survive correction for multiple comparisons.

Alterations in reward and emotion regulation regions have been previously demonstrated in individuals with obesity 41, 56, 57. The basal ganglia and the related corticostriatal pathways, in particular, play a crucial role. The nucleus accumbens is a central part of the dopamine system, regulating reward sensitivity and controlling processes underlying food intake and food addiction 39. The reward deficiency model suggests that in obesity, the presence of decreased dopamine signalling in the striatum reinforces the rewarding properties of food and disrupts corticostriatal communication between the basal ganglia (core reward) and the extended reward system 83, 84. Similar to other addictive disorders in which perturbations in brain regions within the core and extended reward networks have been reported, a less responsive dopamine system leads to a greater propensity towards obesity 40, 85, 86, 87, 88. The extended reward system involves regions associated with salience and cortical inhibition (prefrontal control) networks 39, 89, 90, 91. In obesity, the salience network integrates salient information to make decisions regarding food intake 92, 93, 94, 95 and, together with the executive control network, inhibits reward impulses 96, 97. When viewed together with these reports, the study results suggest that in individuals with high BMI, ELAs may further increase the engagement of emotion regulation and reward regions, perhaps contributing to increased food seeking behaviours, as measured by YFAS.

In participants with high BMI, levels of food addiction were negatively associated with centrality of the thalamus (somatosensory network). These study results are consistent with previous studies, which have demonstrated decreased functional activation and anatomical connectivity of somatosensory regions in obesity 40, 41, 53, 56, 57, 98, 99. Food addiction has been implicated in obesity as a result of alterations in the extended reward network 39, 40, 94; the somatosensory network represents an important component of the extended reward network, playing a key role in interoceptive and sensory awareness and generating appropriate motor responses 41, 100, 101. These findings may reflect reduced dopamine signalling in the thalamus and perhaps the striatum as a whole, which has been associated with reinforcing the rewarding properties of food and, in individuals with high BMI but not normal BMI, with increased metabolism in somatosensory cortical regions 83.

In participants with high BMI, ELA (physical) scores showed increased associations with food addiction through increased centrality of reward regions (VTA–SN, an important hub of dopaminergic signalling 102). These associations were not seen with other ELA subscores. In individuals with normal BMI, higher levels of all ELA subscores were associated with lower food addiction through increased centrality of the executive control regions (OFG and mPFC).

The relationships between different types of ELA and alterations in functional and anatomical brain connectivity measures has been explored previously 11. ELA (general) may not be as severe or personal in nature as other ELAs and may actually serve as a source of increased resilience 11. Participants with normal BMI showed associations between food addiction and ELA (general), reflecting associations that may be protective. Participants with high BMI (high BMI group and men with high BMI) showed associations between food addiction and other, non‐general ELAs (physical and sexual), perhaps reflecting the more deleterious nature of these ELAs. Individuals with a history of general ELA (as opposed to physical or sexual) may be more likely to translate these experiences into adulthood resiliency, which may explain the potentially protective nature of these experiences 103. These findings provide a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between ELA and food addiction.

The basal ganglia (regions within the reward network) receive input from several cortical (including sensory, motor and executive control), limbic, salience and midbrain regions. The basal ganglia are involved in a range of learning behaviours related to the anticipation and motivation associated with ingestive behaviours 39, 104, 105. The study results demonstrate evidence that ELA may increase food addiction through increased centrality of core reward regions. Although causality remains to be determined, these findings suggest that in addition to obesity, ELA plays a role in alterations in the extended reward regions, which are associated with food addiction. ELA may contribute to disruptions in the topology of these brain regions and increase vulnerability to develop food addiction, relative to changes seen in obesity alone. Longitudinal studies will need to determine if obesity and its associated metabolic changes cause rewiring in brain architecture or if genetic factors and ELA are the primary drivers in shaping brain networks and predisposing an individual to develop maladaptive eating behaviours.

In women with high BMI, higher food addiction scores were associated with greater centrality in the core reward regions; however, in men with high BMI, higher food addiction scores were associated with decreased centrality of core reward and salience regions. Additionally, the network of women with high BMI revealed a negative association between food addiction and centrality of the executive control network (vlPFC), whereas in the network of men with high BMI, this association was positive (OFG and vlPFC). These differences are consistent with previous work describing increased post‐prandial activations in reward regions in women and somatosensory regions in men 53, 56, 57, 98, 106, 107, 108, 109. In women with high BMI, greater engagement of reward regulation networks, combined with reduced engagement of executive control regions, may increase susceptibility to cravings for certain foods, especially sugar 53, 108, 109, 110. Furtheremore, disruptions to these regions in women have been shown to result in hyperphagia 53, 107, 108.

These findings at the brain level are consistent with epidemiological studies that show sex‐related differences in food addiction related to the types of foods craved and the intensity and frequency of the cravings 31, 32. For example, women crave sweets such as chocolates, while men crave savoury foods. Additionally, women report more trait‐related and state‐related cravings, finding it more difficult to cognitively regulate or restrain food cravings 31, 32. On the other hand, men consume larger bite sizes and chew faster and more forcefully compared with women 32. This is consistent with the study results, which show an association between ELA (sex) and food addiction through centrality in somatosensory (thalamus) regions only in men with high BMI. These ingestive patterns could translate to women eating more often and men consuming larger meals in response to ELA.

Compared with men with high BMI, women with high BMI report higher food addiction behaviours, cravings, comorbidity, reward sensitivity and repeated unsuccessful attempts to maintain weight loss 33, 34, 35. The findings reported here, which suggest that men with high BMI differ from their female counterparts in the processing and modulation of rewarding food stimuli, may be attributed to the ability of oestrogen to modulate dopaminergic and serotonergic signalling 40, 111. 17‐Beta‐estradiol has been shown to directly potentiate dopamine release in the rat nucleus accumbens 112. It is also important to note that serotonergic neurons in the midbrain differentiate early during CNS development, with sex differences in the serotonergic system of the rat brain established as early as the second postnatal week, likely mediated by intracellular oestrogen receptors 113, 114. These developmental sex differences may set the stage for enhanced corticolimbic responsiveness to emotional stimuli in women 115. Alternatively, the sex‐specific interactions between ELA, brain connectivity and food addiction behaviours may be a result of differential activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis. Although at times conflicting, data from numerous studies have demonstrated notable sex differences with respect to stress‐induced cortisol levels 116, 117, 118. It is important to note, though, that sex differences may not represent exclusively fundamental biological differences, as hedonic food intake may also be influenced by cultural differences in societal expectations from men and women 119, 120.

The cross‐sectional nature of the study did not enable us to address questions of causality between the observed brain changes, clinical/behavioural outcomes, self‐reported ELA and obesity. Future studies will need to determine if the observed alterations in the brain's extended reward network in obesity represent a pre‐obesity state, increasing the risk of developing maladaptive eating patterns during stress. Alternatively, they may be a consequence of remodelling of the brain as a consequence to ELA or obesity. Another limitation of the cross‐sectional nature of this study is that it is not possible to discern whether the differences in brain circuitry, which are influenced by ELA, contribute to food addiction or if the food addiction behaviours themselves contribute to the observed differences in the brain. Although BMI, which expresses the relationship between height and weight and is the most widely used measure of obesity, is not ideal as it does not translate to the presence of disease. Therefore, future studies may consider other measures of obesity such as waist–hip ratio or visceral adiposity in order to validate the current BMI studies. Future studies, which are appropriately powered, may benefit from three group subanalysis, further dividing the high BMI group into ‘overweight’ and ‘obese’ categories.

To measure ELA, ETI‐SR was used, which does not capture the age at which the ELA occurs. Future studies may benefit from incorporating other measures of ELA that capture this information or include it into the weight of the ELA score or that quantify severity such as the Adverse Childhood Experiences questionaire 121. ETI‐SR may also be limited by recall accuracy; future, long‐term longitudinal studies would likely more accurately reflect ELA that may be missed with self‐report questionnaires. Additionally, future studies may benefit from less stringent exclusion criteria, including individuals who have experienced ELAs but are less healthy and suffer from other forms of addictive disorders. To assess for food addiction, we used the original YFAS 19, which is based on the DSM‐IV. Future studies may benefit from using the YFAS 2.0, which is based on the DSM‐5 criteria 122. Larger samples are needed with a wider range of clinical and behavioural symptoms in order to assess subgroup differences (e.g. obese versus overweight versus normal weight or high food addiction versus low food addiction; different ethnicities). Future studies with larger sample sizes will also allow for mediation and moderation analyses to be conducted. Although various trends in the data were observed, some of these trends may be due to a limited sample size, especially with respect to subgroup differences. Assessments for depression and anxiety, which are often comorbid conditions in obesity, will help to characterize obesity states. When treating YFAS as a dichotomous variable (using the accepted threshold of ≥3), YFAS was associated with having a higher BMI, although no statistically significant differences in YFAS scores by BMI status emerged when treating YFAS as a continuous variable; our results should be interpreted within this context. In addition, multimodal imaging will provide a better understanding of these findings. As systemic inflammatory markers 123 and metabolites such as those derived from the gut microbiota have been associated with obesity and food addiction, future mechanistic studies that integrate these mediators are also of value.

This study builds on previous work exploring the relationship between ELA, obesity and food addiction. Participants with high BMI showed higher positive associations between ELA and centrality of emotional regulation regions and food addiction scores. In contrast, participants with normal BMI showed higher positive associations between ELA and centrality of executive control regions. These ELA–brain interactions differed substantially by sex, contributing to a more nuanced understanding of the forces driving the pathophysiology of obesity and food addiction. Women with high BMI showed positive associations with ELA and centrality of reward and emotional regulation regions and with food addiction. In contrast, men with high BMI showed associations with ELA and centrality of somatosensory regions and food addiction. These findings may have implications for more effective, sex‐specific and behavioural treatments for obesity, especially for individuals whose obesity may be driven primarily by food addiction. For clinicians treating patients with obesity and food addiction, a more personalized treatment plan, incorporating patient sex and history of ELA, may be of value especially when treatment includes brain‐directed therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy.

Conflict of Interest Statement

No conflicts of interest exist.

Research involving human participants and informed consent

All procedures complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Institutional Review Board at UCLA's Office of Protection for Research Participants. All participants provided written informed consent.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases including K23 DK106528 (A. G.), R01 DK048351 (E. A. M.), P50 DK064539 (E. A. M.) and P30 DK041301, and pilot funds were provided for brain scanning by the Ahmanson‐Lovelace Brain Mapping Center. Preliminary data were reported in an abstract presented as a poster at Digestive Diseases Week (DDW), Washington DC, 2018.

Osadchiy V., Mayer E. A., Bhatt R., Labus J. S., Gao L., Kilpatrick L. A., Liu C., Tillisch K., Naliboff B., Chang L., and Gupta A. (2019) History of early life adversity is associated with increased food addiction and sex‐specific alterations in reward network connectivity in obesity, Obesity Science & Practice. 5:416–436. 10.1002/osp4.362.

References

- 1. Williamson DF, Thompson TJ, Anda RF, Dietz WH, Felitti V. Body weight and obesity in adults and self‐reported abuse in childhood. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2002. Aug; 26: 1075–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Felitti VJ, Jakstis K, Pepper V, Ray A. Obesity: problem, solution, or both? Perm J 2010. Spring; 14: 24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Farr OM, Ko BJ, Joung KE, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder, alone or additively with early life adversity, is associated with obesity and cardiometabolic risk. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2015. May; 25: 479–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hemmingsson E. Early childhood obesity risk factors: socioeconomic adversity, family dysfunction, offspring distress, and junk food self‐medication. Curr Obes Rep 2018. Jun; 7: 204–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hemmingsson E, Johansson K, Reynisdottir S. Effects of childhood abuse on adult obesity: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obes Rev 2014. Nov; 15: 882–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Brody M, Toth C, Burke‐Martindale CH, Rothschild BS. Childhood maltreatment in extremely obese male and female bariatric surgery candidates. Obes Res 2005. Jan; 13: 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fink K, Ross CA. Adverse childhood experiences in a post‐bariatric surgery psychiatric inpatient sample. Obes Surg 2017. Dec; 27: 3253–3257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thomason ME, Marusak HA. Toward understanding the impact of trauma on the early developing human brain. Neuroscience 2017. Feb 7; 342: 55–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saleh A, Potter GG, McQuoid DR, et al. Effects of early life stress on depression, cognitive performance and brain morphology. Psychol Med 2017. Jan; 47: 171–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cohen RA, Grieve S, Hoth KF, et al. Early life stress and morphometry of the adult anterior cingulate cortex and caudate nuclei. Biol Psychiatry 2006. May 15; 59: 975–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gupta A, Mayer EA, Acosta JR, et al. Early adverse life events are associated with altered brain network architecture in a sex‐dependent manner. Neurobiol Stress 2017. Dec; 7: 16–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Heany SJ, Groenewold NA, Uhlmann A, Dalvie S, Stein DJ, Brooks SJ. The neural correlates of Childhood Trauma Questionnaire scores in adults: a meta‐analysis and review of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Dev Psychopathol 2017. Dec; 11: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marusak HA, Thomason ME, Peters C, Zundel C, Elrahal F, Rabinak CA. You say ‘prefrontal cortex’ and I say ‘anterior cingulate’: meta‐analysis of spatial overlap in amygdala‐to‐prefrontal connectivity and internalizing symptomology. Transl Psychiatry 2016. Nov 8; 6: e944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Calem M, Bromis K, McGuire P, Morgan C, Kempton MJ. Meta‐analysis of associations between childhood adversity and hippocampus and amygdala volume in non‐clinical and general population samples. Neuroimage Clin 2017; 14: 471–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Berens AE, Jensen SKG, Nelson CA 3rd. Biological embedding of childhood adversity: from physiological mechanisms to clinical implications. BMC Med 2017. Jul 20; 15: 135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Teicher MH, Anderson CM, Ohashi K, Polcari A. Childhood maltreatment: altered network centrality of cingulate, precuneus, temporal pole and insula. Biol Psychiatry 2014. Aug 15; 76: 297–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR, Brownell KD. Food addiction: an examination of the diagnostic criteria for dependence. J Addict Med 2009. Mar; 3: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gearhardt AN, Grilo CM, DiLeone RJ, Brownell KD, Potenza MN. Can food be addictive? Public health and policy implications. Addiction 2011. Jul; 106: 1208–1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn: Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Carter A, Hendrikse J, Lee N, et al. The neurobiology of “food addiction” and its implications for obesity treatment and policy. Annu Rev Nutr 2016. Jul 17; 36: 105–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leigh SJ, Lee F, Morris MJ. Hyperpalatability and the generation of obesity: roles of environment, stress exposure and individual difference. Curr Obes Rep 2018. Mar; 7: 6–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cottone P, Sabino V, Roberto M, et al. CRF system recruitment mediates dark side of compulsive eating. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009. Nov 24; 106: 20016–20020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Raymond C, Marin MF, Majeur D, Lupien S. Early child adversity and psychopathology in adulthood: HPA axis and cognitive dysregulations as potential mechanisms. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2018. Jul 13; 85: 152–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pagoto SL, Spring B, McChargue D, et al. Acute tryptophan depletion and sweet food consumption by overweight adults. Eat Behav 2009. Jan; 10: 36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sato W, Sawada R, Kubota Y, Toichi M, Fushiki T. Homeostatic modulation on unconscious hedonic responses to food. BMC Res Notes 2017. Oct 26; 10: 511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Blundell JE, Finlayson G. Is susceptibility to weight gain characterized by homeostatic or hedonic risk factors for overconsumption? Physiol Behav 2004. Aug; 82: 21–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]