Abstract

Tyrosyl DNA-phosphodiesterase I (TDP1) repairs type IB topoisomerase (TOP1) cleavage complexes generated by TOP1 inhibitors commonly used as anticancer agents. TDP1 also removes DNA 3′ end blocking lesions generated by chain-terminating nucleosides and alkylating agents, and base oxidation both in the nuclear and mitochondrial genomes. Combination therapy with TDP1 inhibitors is proposed to synergize with topoisomerase targeting drugs to enhance selectivity against cancer cells exhibiting deficiencies in parallel DNA repair pathways. A crystallographic fragment screening campaign against the catalytic domain of TDP1 was conducted to identify new lead compounds. Crystal structures revealed two fragments that bind to the TDP1 active site and exhibit inhibitory activity against TDP1. These fragments occupy a similar position in the TDP1 active site as seen in prior crystal structures of TDP1 with bound vanadate, a transition state mimic. Using structural insights into fragment binding, several fragment derivatives have been prepared and evaluated in biochemical assays. These results demonstrate that fragment-based methods can be a highly feasible approach toward the discovery of small-molecule chemical scaffolds to target TDP1, and for the first time, we provide co-crystal structures of small molecule inhibitors bound to TDP1, which could serve for the rational development of medicinal TDP1 inhibitors.

INTRODUCTION

A member of the phospholipase D superfamily, tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase I (TDP1) (E.C. 3.1.4.1) was discovered as a DNA-repair enzyme that cleaves the phosphodiester bond between a tyrosine residue of type IB topoisomerase (TOP1) and the 3′ phosphate of DNA that occurs in stalled TOP1-DNA cleavage complexes (TOP1cc) (1,2). Human cells encode six DNA topoisomerases that regulate DNA topology by transiently cleaving the DNA backbone to remove DNA supercoiling, unlinking post-replication catenanes and resolving DNA knots (3). The TOP1 active site tyrosine reversibly ‘breaks’ the phosphodiester linkage of one strand of the double-stranded DNA by a nucleophilic attack, resulting in a TOP1-DNA covalent reaction intermediate that links this Tyr to the 3′ end of the broken strand via a phosphodiester moiety. Inhibitors of TOP1 that block the religation of TOP1cc by binding at the enzyme–DNA interface (4) and generate stalled TOP1cc are used as anticancer drugs in the clinic (3,5). TDP1 has been hypothesized to be a pharmacological target for the treatment of cancer (6–10).

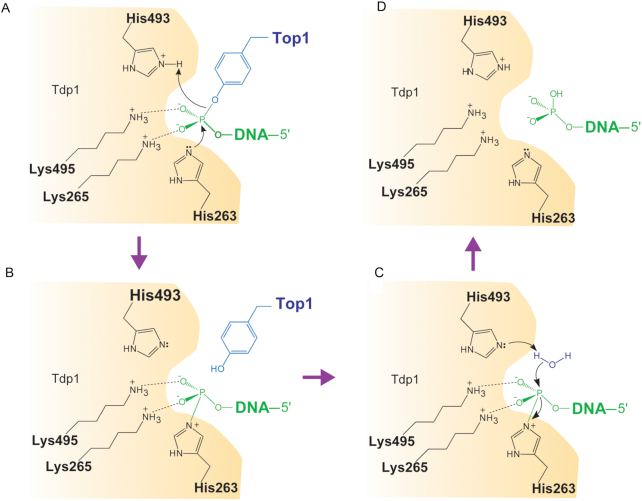

TDP1 repairs DNA lesions that are created by the trapping of TOP1 following treatment by camptothecin and its derivatives such as topotecan and irinotecan as well as those that accumulate under other physiological conditions where TOP1 acts on DNA alterations. (2,11–13). It carries out these functions by hydrolyzing the covalent bond between the TOP1 catalytic tyrosine residue and the 3′ end of the DNA in a two-step reaction (Figure 1) (2,8,13,14). First, it cleaves the 3′ tyrosyl bond by forming a transient covalent intermediate between a conserved histidine (H263 for human TDP1) and the 3′ phosphate end. The covalent TDP1-DNA bond is then released by hydrolysis, which requires a second histidine of TDP1 (H493 for human TDP1) (1,15,16) (Figure 1). Subsequently, polynucleotide kinase phosphatase (PNKP) removes the residual 3′ phosphate and installs a phosphate on the 5′ end at the opposing side of the break. At last, DNA ligase III reseals the DNA (12). The repair function of TDP1 is not just limited to TOP1 cleavage complexes. It also removes 3′ phosphoglycolate caused by oxidative DNA damage and 3′ blocking lesions generated by oxygen radicals and alkylating agents (12,17,18). It can also serve as a backup repair pathway for DNA lesions generated by the trapping of DNA topoisomerase II (TOP2α and TOP2β) on DNA (17,19–21). These observations highlight a potentially broad and important role for TDP1 in the maintenance of genomic stability. TDP1-dependent repair pathways are normally redundant with other DNA damaging response pathways, such as Mre11 and XPF (22,23) that are often compromised in cancer cells.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of TDP1 catalytic mechanism. Residue numbers refer to human TDP1. Curved arrows denote the transfer of electron pairs. (A) The imidazole N2 atom of H263 nucleophilically attacks the phosphate of the phosphotyrosyl group (B) Phosphohistidine covalent intermediate. (C) Hydrolysis of the phosphohistidine intermediate by H493-activated water molecule. (D) Generation of a final 3′ phosphate product and free TDP1.

Checkpoint and repair deficiencies are common in many cancer cells and, in these cases, TDP1 becomes the main mechanism for removal of TOP1-mediated DNA damage (3,24). It has been proposed that combination chemotherapy with TDP1 inhibitors and topoisomerase-targeting drugs should work synergistically to enhance selectivity toward cancer cell lines with pre-existing deficiencies in parallel repair pathways such as XPF-ERCC1, giving rise to synthetic lethality (25,26). Based on the broad spectrum of TDP1 substrates, TDP1 inhibitors should not only synergize with TOP1-targeting agents such as irinotecan, topotecan and other camptothecin derivatives, but also with the indenoisoquinoline derivative non-camptothecin TOP1 inhibitors in clinical development (5) and with gemcitabine, a drug that is used for the treatment of various cancers (27). Despite the potential therapeutic value of TDP1 as an anti-cancer drug target, there are no drugs currently in the clinic that specifically target TDP1 (7,10). Although, there are a limited number of TDP1 inhibitors that have been reported in the literature (7,10,14,28,29) and the first crystal structures of TDP1 were solved nearly 15 years ago (15,16), crystal structures of TDP1 bound to a small molecule inhibitor have yet to be reported. The determination of a crystal structure of TDP1 bound to a small molecule, therefore, could potentially facilitate structure-based drug design efforts focused on the development of novel TDP1 inhibitors.

Within the past decade, fragment-based drug discovery has grown into an effective and viable method for deriving new pharmacophores which have often progressed into lead compounds for a variety of challenging targets (30,31). Fragments found in many commercial screening libraries are typically low molecular weight compounds (<250 Da) that adhere to the Lipinski rule of three and are readily amenable to further chemical modification (32,33). Such fragments provide chemical scaffolds that are smaller and less complex than those typically found in high-throughput screening assays (34). In turn, this often leads to an increased probability that a fragment will bind to a target protein, resulting in higher hit rates and more efficient screening of diverse chemical space. A major advantage of fragment-based drug discovery is that it can identify lead compounds that possess high-ligand efficiency with the opportunity to fine-tune physiochemical properties during elaboration and optimization. Hits identified from fragment screens can also reveal unanticipated binding pockets or hot spots within a target protein (35,36). A wide array of biophysical techniques can be used to rapidly identify weak protein-binding fragments (37,38). X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy were among the first to be utilized in fragment-based drug discovery (38–40). Although still time-consuming and labor intensive, X-ray crystallography is a powerful primary method for screening fragment libraries that has noteworthy advantages over other biophysical screening methods (31,41). Many initial fragments tend to exhibit very weak binding affinities from the high micromolar to low millimolar range. X-ray crystallography provides the sensitivity needed to confirm the binding of such weak compounds and it concurrently reveals the structural information that is needed to immediately advance these fragments from hits to leads using structure-guided drug design (30).

In an attempt to identify novel chemicals that bind to and inhibit TDP1, we carried out a crystallographic fragment screening campaign using a library of ∼640 fragment compounds. Two types of fragments were identified that bind to the active site pocket and members from both series exhibit inhibitory activity against TDP1. Herein, for the first time we provide the high-resolution crystal structures of TDP1 bound to small molecules. These may provide structural insights for structure-guided drug design efforts to identify and optimize inhibitors of TDP1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning and expression

A derivative of the Gateway™ vector pDONR221 containing the open reading frame (ORF) encoding the human TDP1 catalytic domain (residues S148–S608) preceded by a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease recognition site was provided by Dr Tinoush Moulaei, Protein Structure Section, Macromolecular Crystallography Laboratory, National Cancer Institute. The ORF was moved by recombinational cloning into the destination vector pDEST-527 to produce pDN2454. This plasmid directs the expression of human TDP1 (S148–S608) with an N-terminal hexahistidine tag and an intervening TEV protease cleavage/recognition site (ENLYFQ/S148) (42). The fusion protein was expressed in the Escherichia coli strain BL21 Star™ (DE3) (Invitrogen ThermoFisher Scientific). Cells containing pDN2454 were grown to mid-log phase (OD600 ∼ 0.5) at 37°C in Luria Bertani broth (Cellgro) containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 0.2% glucose. Overproduction of fusion protein was induced with isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside at a final concentration of 1 mM for 18–20 h at 18°C. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation and stored at −80°C.

Purification

All procedures were performed at 4–8°C. A total of 20–25 g of E. coli cell paste expressing human TDP1 (S148-S608) with an N-terminal hexahistidine tag were suspended in 250 ml ice-cold buffer A (50 mM Tris–HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 25 mM imidazole, pH 7.5) containing 5 mM benzamidine HCl (Sigma Aldrich Corporation) and Complete™ (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics). The cells were lysed with an APV-1000 homogenizer (Invensys APV Products) at 10 000 psi and centrifuged at 30 000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm polyethersulfone membrane and applied to a HisTrap FF column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) equilibrated in buffer A. The column was washed to baseline with buffer A and eluted with a linear gradient of imidazole to 1 M. Fractions containing the His6-TDP1 fusion protein were pooled, concentrated using an Ultracel® 30 kDa ultrafiltration disc (EMD Millipore Corporation), diluted with 50 mM Tris–HCl, 500 mM NaCl, pH 7.5 buffer to reduce the imidazole concentration to about 25 mM, and digested overnight at 4°C with His7-tagged TEV protease (43). The digest was applied to the HisTrap FF column equilibrated in buffer A and the TDP1 emerged in the column effluent. The effluent was incubated overnight at 4°C with 10 mM dithiothreitol, concentrated using an Ultracel® 10 kDa ultrafiltration disc, and applied to a HiPrep 26/60 Sephacryl S-300 HR column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) equilibrated in 25 mM Tris–HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 2 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine, pH 7.5 buffer. Fractions containing TDP1 (S148-S608) were pooled, concentrated as above, diluted with 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5 buffer to reduce the NaCl concentration to 25 mM and applied to a HiTrap Q HP column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) equilibrated in 50 mM Tris–HCl, 25 mM NaCl, pH 7.5 buffer. Recombinant protein that emerged in the column effluent was pooled and applied to a HiTrap SP HP column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) equilibrated in 50 mM HEPES, 25 mM NaCl, pH 7.2 buffer. The column was washed to baseline with equilibration buffer and eluted with a linear gradient of NaCl to 500 mM. Fractions containing pure TDP1 were pooled, concentrated as above and applied to the HiPrep 26/60 Sephacryl S-300 HR column equilibrated in 25 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine, pH 7.2 buffer. The peak fractions containing recombinant TDP1 (S148–S608) were pooled and concentrated to 30–50 mg/ml (estimated at 280 nm using a molar extinction coefficient of 112 300 M−1 cm−1 (derived using the Expasy ProtPram tool) (44). Aliquots were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. The final product was judged to be >95% pure by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The molecular weight was confirmed by electrospray ionization mass spectroscopy (LC/ESMS).

Crystallization

The catalytic domain of TDP1 (residues S148–S608) was screened for crystallization conditions using several sparse-matrix crystallization screens from Hampton Research, Qiagen, Molecular Dimensions and Anatrace. The most promising conditions were obtained using the Morpheus crystallization screen (45). Crystallization plates were prepared using a Gryphon crystallization robot (Art Robbins Instruments). Diffraction-quality crystals used for crystallographic fragment screening were obtained from drops consisting of 2 μl TDP1 (22 mg/ml) with 2 μl well solution consisting of 0.1 M MOPS/HEPES-Na pH 7.5, 10% (w/v) PEG 8000, 20% (v/v) ethylene glycol, 0.03 M sodium fluoride, 0.03 M sodium bromide, 0.03 M sodium iodide and sealed over 500 μl well solution in a Nextal 15-well crystallization plate (Qiagen). Crystallographic fragment screening was carried out using the Zenobia Fragment Library 1 and Zenobia Fragment Library 2.2 (Zenobia Fragments). In preparation for crystallographic screening, cocktail mixtures were prepared by mixing four fragments together (single fragment stock, 200 mM, final concentration 50 mM) in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). A 4-μl soaking drop was then prepared by adding stock concentration of the cocktail mixture to well solution to achieve a final concentration of 5 mM for each fragment (10% (v/v) DMSO). TDP1 crystals were then transferred to the soaking drop and soaked for a period of 24 h. The crystals were retrieved from the drop using a litholoop (Microlytic) and immediately flash-cooled by plunging into liquid nitrogen without the need of further cryoprotectant. For structural studies of TDP1 in complex with fragment derivatives (Table 1), crystals of TDP1 were transferred to well solution consisting of compound in DMSO (concentration listed in Table 2) and 0.1 M MOPS/HEPES-Na pH 7.5, 10% (w/v) PEG 8000, 20% (v/v) ethylene glycol, 0.03 M sodium fluoride, 0.03 M sodium bromide and 0.03 M sodium iodide. The crystals were soaked for 24 h and retrieved from the drop using a litholoop and immediately flash-cooled by plunging into liquid nitrogen.

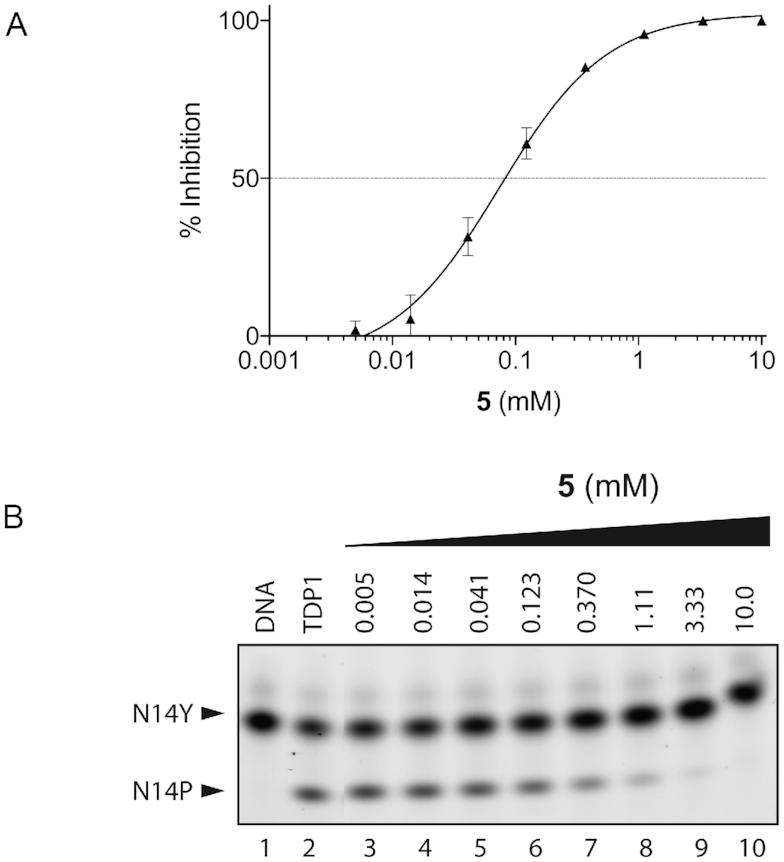

Table 1.

Compounds discussed in the text

|

Table 2.

X-ray diffraction data collection and refinement statistics

| TDP1–Compound 1 (cocktail soak) | TDP1–Compound 1 (single soak) | TDP1–Compound 2 (cocktail soak) | TDP1–Compoiund 2 (single soak) | TDP1–Compound 3 | TDP1–Compound 4 | TDP1–Compound 5 | TDP1–Compound 6 | TDP1–Compound 7 | TDP1–Compound 8 | TDP1–Compound 9 | TDP1–Compound 10 | TDP1–Compound 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fragment concentration (mM) | 5 | 20 | 5 | 20 | 20 | 5.5 | 17 | 20 | 22.5 | 4.5 | 13.6 | 9.9 | 16.4 |

| Diffraction Source | SER-CAT 22-ID | SER-CAT 22-BM | SER-CAT 22-BM | SER-CAT 22-BM | SER-CAT 22-ID | SER-CAT 22-BM | SER-CAT 22-BM | SER-CAT 22-ID | SER-CAT 22-ID | SER-CAT 22-ID | SER-CAT 22-ID | SER-CAT | SER-CAT |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.00000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 |

| a-, b = , c = (Å) | 50.05, 105.26, 193.91 | 50.09, 105.63, 194.03 | 50.11, 105.64, 194.95 | 50.12, 105.41, 194.56 | 49.91, 105.59, 194.19 | 49.77, 104.99, 194.11 | 49.94, 105.14, 193.37 | 50.06, 105.37, 194.58 | 50.16, 105.31, 193.98 | 50.07, 105.14, 194.45 | 50.16, 105.59, 193.98 | 50.05, 105.41, 194.1 | 49.96, 105.06, 193.32 |

| α=,β=,γ= (°) | 90,90,90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90,90,90 | 90,90,90 | 90,90,90 | 90,90,90 | 90,90,90 | 90,90,90 | 90,90,90 | 90,90,90 | 90,90,90 | 90,90,90 |

| Data Collection Statistics | |||||||||||||

| Resolution Range (Å) | 50–1.63 (1.66–1.63)a | 50–1.78 (1.81-1.78) | 50-1.81 (1.84–1.81) | 50–1.78 (1.81–1.78) | 50–1.78 (1.81–1.78) | 50–1.75 (1.78–1.75) | 5–1.74 (1.77–1.74) | 50–1.70 (1.73–1.70) | 50–1.67 (1.70–1.67) | 50–1.91 (1.94–1.91)a | 50–1.85 (1.88–1.85) | 50–1.62 (1.65–1.62) | 50–1.50 (1.53–1.50) |

| Total No. of reflection | 876 873 | 632 682 | 395 972 | 492 373 | 1 443 515 | 630 560 | 536 200 | 781 610 | 841 105 | 531 475 | 544 340 | 908 312 | 1 022 403 |

| Total No. of unique reflections | 128 455 | 99 895 | 93 819 | 98 896 | 100 750 | 105 159 | 105 222 | 112 529 | 120 178 | 78 029 | 83 875 | 131 858 | 157 054 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.6 (98.4) | 100 (100) | 97.8 (98.5) | 98.7 (98.2) | 99.9 (100) | 99.6 (94.3) | 99.9 (97.8) | 99.7 (98.7) | 99.6 (99.3) | 98.3 (96.5) | 95.0 (93.8) | 100 (99.8) | 96.2 (92.9) |

| CC1/2b | 0.754 | 0.769 | 0.622 | 0.733 | 0.891 | 0.925 | 0.956 | 0.790 | 0.870 | 0.754 | 0.817 | 0.760 | 0.802 |

| Multiplicity | 6.8 (6.1) | 6.3 (6.1) | 4.2 (3.8) | 5.0 (4.9) | 14.3 (14.0) | 6.0 (5.1) | 5.1 (4.4) | 6.9 (5.7) | 7.0 (6.5) | 6.8 (6.6) | 6.5 (6.0) | 6.9 (6.1) | 6.5 (5.7) |

| I/(σ) I | 38.2 (2.3) | 32.7 (3.1) | 29.2 (2.3) | 29.3 (2.3) | 48.3 (4.5) | 41.7 (4.9) | 39.8 (6.7) | 35.4 (3.0) | 37.8 (3.5) | 28.4 (2.6) | 25.7 (2.5) | 28.1 (2.2) | 37.2 (2.0) |

| Rsym | 0.062 (0.711) | 0.078 (0.918) | 0.071 (0.882) | 0.071 (0.561) | 0.117 (0.780) | 0.051 (0.327) | 0.050 (0.215) | 0.081 (0.811) | 0.072 (0.771) | 0.088 (0.957) | 0.104 (0.801) | 0.071 (0.046) | 0.046 (0.806) |

| Rpim | 0.025 (0.311) | 0.034 (0.405) | 0.036 (0.501) | 0.035 (0.289) | 0.032 (0.219) | 0.023 (0.157) | 0.024 (0.115) | 0.033 (0.352) | 0.030 (0.316) | 0.036 (0.343) | 0.043 (0.342 | 0.027 (0.349) | 0.023 (0.353) |

| Refinement Statistics | |||||||||||||

| Resolution Range (Å) | 35.66–1.63 | 37.08–1.78 | 40.99–1.81 | 37.12–1.78 | 40.91–1.77 | 36.12–1.75 | 36.96–1.74 | 35.68–1.70 | 35.70–1.67 | 37.08–1.91 | 36.42–1.85 | 35.7–1,62 | 36.3–1.50 |

| Final Rwork | 0.181 | 0.179 | 0.186 | 0.186 | 0.179 | 0.181 | 0.174 | 0.191 | 0.188 | 0.178 | 0.178 | 0.180 | 0.180 |

| Final Rfree | 0.211 | 0.215 | 0.227 | 0.227 | 0.216 | 0.211 | 0.206 | 0.227 | 0.212 | 0.228 | 0.218 | 0.202 | 0.201 |

| No. of non H-atoms/Average B factor (Å2) | |||||||||||||

| Protein chain A | 3640/38.5 | 3599/26.1 | 3605/28.6 | 3612/25.7 | 3627/24.8 | 3633/22.7 | 3625/19.0 | 3609/24.7 | 3616/23.9 | 3616/26.5 | 3626/23.7 | 3623/23.7 | 3654/24.8 |

| Protein chain B | 3619/30.3 | 3601/31.5 | 3610/34.9 | 3582/32.1 | 3596/29.1 | 3619/25.9 | 3621/23.0 | 3587/32.0 | 3616/30.2 | 3601/33.9 | 3591/30.6 | 3618/28.3 | 3606/28.5 |

| Water | 695/38.9 | 676/38.7 | 582/39.5 | 727/38.8 | 711/38.2 | 779/34.7 | 886/33.4 | 648/38.6 | 619/37.6 | 586/38.9 | 580/36.9 | 842/38.9 | 796/40.0 |

| Ligand chain A | 15/37.2 | 15/29.8 | 14/36.3 | 14/32.7 | 13/28.6 | 13/26.5 | 13/20.0 | 17/31.5 | 17/38.2 | 15/37.2 | 17/36.4 | 20/29.7 | 21/33.5 |

| Ligand chain B | 15/39.5 | 15/35.1 | 14/45.3 | 14/44.0 | 13/30.8 | 13/26.4 | 13/21.7 | 17/36.2 | 17/39.1 | 15/37.2 | 17/39.3 | 20/34.5 | 17/31.1 |

| Ethylene glycol | 40/37.9 | 16/31.7 | 24/37.7 | 16/29.5 | 12/26.0 | 24/28.6 | 28/27.6 | 16/30.6 | 16/30.8 | 12/29.9 | 12/32.5 | 20/32.6 | 12/30.4 |

| R.m.s.d from ideal | |||||||||||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.005 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Ramachandran plot | |||||||||||||

| Favored (%) | 98.3 | 98.0 | 97.7 | 97.1 | 98.2 | 97.9 | 97.9 | 97.6 | 97.6 | 97.6 | 97.9 | 97.8 | 98.0 |

| Allowed (%) | 1.6 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| Disallowed (%) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Molprobity score | 1.08 (99th percentile) | 0.98 (100th percentile) | 1.06 (100th percentile) | 1.17 (99th percentile) | 1.05 (100th percentile) | 1.12 (99th perecentile) | 1.06 (100th percentile) | 1.24 (98th percentile) | 1.19 (99th percentile) | 1.23 (99th percentile | 2.09 (100th percentile) | 3.7 (97th percentile) | 2.5 (99th percentile) |

| PDB code: | 6DHU | 6DIE | 6DIM | 6DJD | 6DIH | 6DJI | 6DJJ | 6DJE | 6DJF | 6DJH | 6MJ5 | 6N17 | 6N19 |

aValues in parenthesis are for the highest-resolution shell of data.

bValue is for the highest-resolution shell of data.

X-ray diffraction datasets were collected at beamlines 22-ID and 22-BM of the SER-CAT facility, Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. Diffraction datasets were processed using HKL3000 (46). For structure solution, molecular replacement was performed using the coordinates of a previously solved crystal structure of TDP1 (PDB code: 1JY1) (15) stripped of solvent molecules as a search model and searching for two molecules in the asymmetric unit using the program Phaser in the PHENIX suite (47). The resulting electron density maps were examined for difference electron density features (contoured at 3.0σ level) to identify bound fragments. Fragment coordinates were prepared using the molinspiration server (www.molinspiration.com) and .cif files for the fragment coordinates were prepared using the eLBOW feature in PHENIX (48). Model rebuilding and water picking were carried out in COOT (49,50) and refined with phenix.refine (51). Model quality and validation were analyzed using MolProbity (52) (Table 2).

Recombinant TDP1 assay

A 5′ 32P-labeled single-stranded DNA oligonucleotide containing a 3′ phosphotyrosine (N14Y) (10) was incubated at 1 nM with 10 pM recombinant full-length TDP1 in the absence or presence of inhibitor for 15 min at room temperature in the assay buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 80 mM KCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 40 μg/ml bovine serum albumin and 0.01% Tween-20 (53). Reactions were terminated by the addition of 1 volume of gel loading buffer [99.5% (v/v) formamide, 5 mM EDTA, 0.01% (w/v) xylene cyanol and 0.01% (w/v) bromophenol blue]. Reaction products were separated on a 16% denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Gels were dried and exposed to a PhosphorImager screen (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Gel images were scanned using a Typhoon FLA 9500 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences), and densitometry analyses were performed using the ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

General synthetic procedures

Proton (1H) and carbon (13C) NMR spectra were recorded on a 400 MHz spectrometer (Varian) or 500 MHz spectrometer (Varian) and are reported in ppm referenced to the solvent in which the spectra were collected. Solvent was removed by rotary evaporation under reduced pressure and anhydrous solvents were obtained commercially and used without further drying. Purification by silica gel chromatography was performed using Combiflash units (Teledyne) with EtOAc−hexanes solvent systems. Preparative high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) was conducted using a Waters 2535 Quaternary Gradient Module having a Waters 2998 photodiode array detector (Waters) and a C18 column (Phenomenex, Cat. No. 00G-4436-P0-AX, 250 mm × 21.2 mm 10 μm particle size, 110 Å pore). Binary solvent systems consisting of A = 0.1% aqueous trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and B = 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile were employed with gradients as indicated. Products were obtained as amorphous solids following lyophilization. Electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) was performed with an Agilent LC/MSD system equipped with a multimode ion source (Agilent). The compounds, benzene-1,2,4-tricarboxylic acid (1), 4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylic acid (2), 4-hydroxyphthalic acid (3), 4-aminophthalic acid (5), 8-isopropyl-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylic acid (6), and 4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3,8-dicarboxylic acid (7) were obtained from commercial sources. The compounds, 3-hydroxyphthalic acid (4) (54), 8-bromo-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylic acid (8) (55), and 4-oxo-8-sulfo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylic acid (9) (56), 4-(3-carboxypropanamido)pthalic acid (10) and 4-(4-carboxybutanamido)pthalic acid (11) were prepared according the published procedures with modifications as described below.

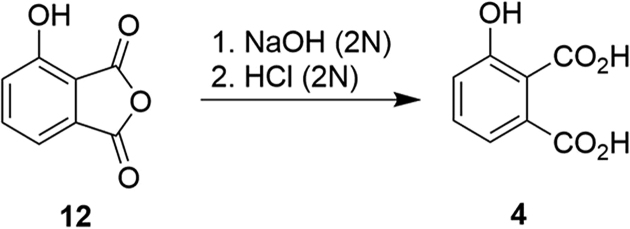

Preparation of 3-hydroxyphthalic acid (4)

In a variation of a previously reported procedure (54), commercially available 4-hydroxyisobenzofuran-1,3-dione (12, 169 mg, 1.0 mmol) was dissolved in aqueous NaOH (2N, 4.0 ml). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature (15 h) and then aqueous HCl (2N) was added to adjust the pH to 2. The resulting solution was purified by preparative HPLC using a linear gradient of 20% B to 50% B over 30 min at a flow rate of 10 ml/min; retention time = 17.4 min. Lyophilization yielded product 4 as a white amorphous solid (80 mg, 43% yield) (Scheme 1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.21 (bs, 1H), 7.33–7.27 (m, 2H), 7.08 (dd, J = 7.4, 1.8 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 168.97, 167.64, 155.12, 130.60, 130.32, 123.67, 120.26, 120.03. ESI-MS m/z: 183.0 (MH+).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 3-hydroxyphthalic acid (4).

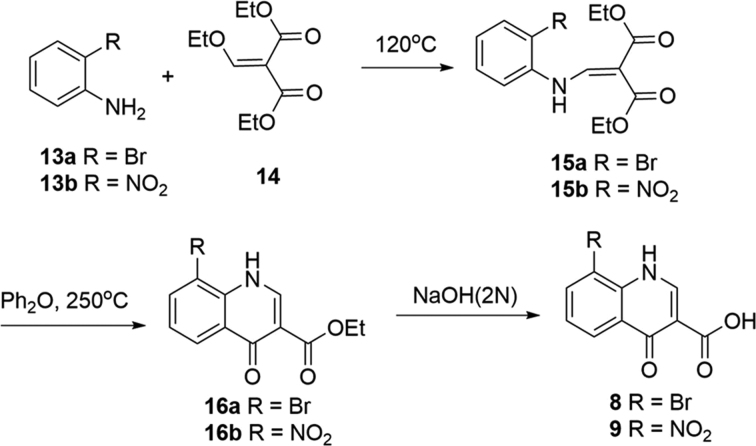

Preparation of 8-bromo-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylic acid (8) and 8-nitro-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylic acid (9).

General procedure A to prepare compounds 15 (a, b)

The mixture of commercially available aniline (13a or 13b, 3.5 mmol) and diethyl 2-(ethoxymethylene)malonate (14, 3.5 mmol) was heated (120°C, 4 h). The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and purified by silica gel column chromatography. Compound diethyl 2-((phenylamino)methylene)malonate (15a or 15b) was afforded (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 8-bromo-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylic acid (8) and 8-nitro-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylic acid (9) (55,59,60).

General procedure B to prepare compounds 14 (a, b)

Diethyl 2-((phenylamino)methylene)malonate (15a or 15b, 0.6 mmol) was suspended in Dowtherm A (0.5 ml) (eutectic mixture of 26.5% diphenyl + 73.5% diphenyl oxide) and the reaction mixture was heated (250°C, 1 h). The resultant mixture was cooled to room temperature and filtered to afford ethyl 4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylate (16a or 16b) (Scheme 2).

General procedure C to prepare compounds 8 and 9

Ethyl 4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylate (16a or 16b, 0.3 mmol) was suspended in sodium hydroxide (2.7 mmol) (1.0 N, 4.0 ml) and EtOH (0.6 ml). The mixture was stirred (70°C, 16 h). The reaction was cooled and acidified by HCl (aq. 2.0 N) and the resulting white solid was filtered and washed with H2O. The solid was further purified by preparative HPLC to afford 4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylic acid (8 or 9) (Scheme 2).

Preparation of diethyl 2-(((2-bromophenyl)amino)methylene)malonate (15a)

The title compound was afforded as a white solid in 88% yield from 2-bromoaniline (13a) and diethyl 2-(ethoxymethylene)malonate (14) using General Procedure A. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 11.28 (d, J = 13.3 Hz, 1H), 8.52 (d, J = 13.3 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.40 – 7.35 (m, 1H), 7.31 (dd, J = 8.3, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.05 – 6.99 (m, 1H), 4.37 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 4.28 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 1.41 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.35 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 168.36, 165.65, 150.53, 137.73, 133.47, 128.75, 125.40, 115.96, 113.71, 95.54, 60.62, 60.30, 14.41, 14.35. ESI-MS m/z: 342.0, 344.0 (MH+).

Preparation of diethyl 2-(((2-nitrophenyl)amino)methylene)malonate (15b)

The title compound was afforded as a yellow solid in 81% yield from 2-nitroaniline and diethyl 2-(ethoxymethylene)malonate (14) using General Procedure A. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 12.60 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H), 8.55 (dd, J = 13.0, 0.6 Hz, 1H), 8.28 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.73 – 7.68 (m, 1H), 7.53 – 7.51 (m, 1H), 7.23 (ddd, J = 8.5, 7.2, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 4.42 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 4.30 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 1.41 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.37 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.74, 165.58, 148.28, 137.09, 136.08, 135.85, 126.81, 123.32, 116.73, 99.45, 60.96, 60.72, 14.36, 14.34. ESI-MS m/z: 309.1 (MH+), 639.2 (M2Na+).

Preparation of ethyl 8-bromo-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylate (16a)

The title compound was afforded as a brown solid in 21% yield from diethyl 2-(((2-bromophenyl)amino)methylene)malonate (15a) using General Procedure B. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.63 (s, 1H), 8.45 (s, 1H), 8.17 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 8.04 (dd, J = 7.7, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 4.23 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 1.28 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 173.26, 164.76, 146.05, 137.10, 136.41, 129.29, 126.11, 126.06, 112.24, 110.75, 60.31, 14.74. ESI-MS m/z: 296.0, 298.0 (MH+).

Preparation of ethyl 8-nitro-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylate (16b)

The title compound was afforded as a brown solid in 13% yield from diethyl 2-(((2-nitrophenyl)amino)methylene)malonate (15b) using General Procedure B. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.18 (s, 1H), 8.65 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.59–8.57 (m, 2H), 7.60 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 4.25 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 1.29 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.48, 164.34, 146.68, 137.22, 134.36, 133.59, 130.69, 129.61, 124.19, 111.92, 60.53, 14.71. DUIS-MS m/z: 263.0 (MH+).

Preparation of 8-bromo-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylic acid (8)

The title compound was afforded as a white fluffy solid in 75% yield from ethyl 8-bromo-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylate (16a) using General Procedure C after HPLC purification using linear gradient of 20% B to 90% B over 30 min at a flow rate of 10 ml/min, retention time = 15.8 min. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 14.86 (brs, 1H), 12.61 (s, 1H), 8.66 (s, 1H), 8.31 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 8.24 (dd, J = 7.7, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 178.61, 166.15, 146.36, 137.93, 137.53, 127.46, 126.69, 125.58, 113.16, 108.71. ESI-MS m/z: 268.0, 269.9 (MH+).

Preparation of 8-nitro-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylic acid (9)

The title compound was afforded as a yellow fluffy solid in 45% yield from ethyl 8-nitro-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylate (16b) using General Procedure C after HPLC purification using linear gradient of 20% B to 90% B over 30 min at a flow rate of 10 ml/min, retention time = 15.1 min. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.97 (brs, 1H), 8.83–8.81 (m, 2H), 8.74 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 177.91, 165.68, 147.21, 137.87, 133.71, 133.54, 132.11, 126.99, 125.70, 109.65. ESI-MS m/z: 235.0 (MH+).

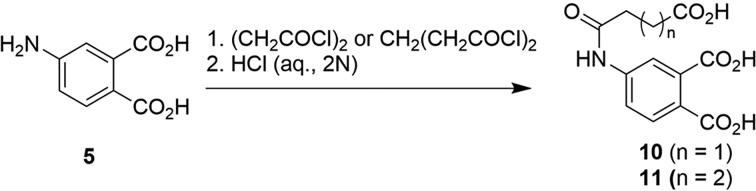

Preparation of 4-(3-carboxypropanamido)phthalic acid (10) and 4-(4-carboxybutanamido)phthalic acid (11)

General Procedure D to prepare compounds 10 and 11

The appropriate carboxyl chlorides (0.67 mmol) were added to the mixture of 4-aminophthalic acid (5, 0.67 mmol) and Na2CO3 (1.68 mmol) in water (3.0 ml). The mixture was stirred (rt, 16 h). The resultant mixture was acidified by HCl (2.0 N) and purified by HPLC to afford 4-amidophthalic acids (7b-e) (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of 4-(3-carboxypropanamido)phthalic acid (10) and 4-(4-carboxybutanamido)phthalic acid (11).

Preparation of 4-(3-carboxypropanamido)phthalic acid (10)

The title compound was afforded as a white solid in 32% yield from 4-aminophthalic acid (5) and succinyl dichloride using general procedure D after HPLC purification using linear gradient of 10% B to 15% B over 20 min at a flow rate of 20 ml/min, retention time = 13.8 min. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.68 (brs, 3H), 10.34 (s, 1H), 7.86 (s, 1H), 7.70 (s, 2H), 2.62 – 2.54 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 174.18, 171.30, 169.59, 168.02, 142.21, 135.87, 130.55, 125.61, 119.87, 118.01, 31.61, 29.07. ESI-MS m/z: 282.1 (MH+), 304.0 (MNa+).

Preparation of 4-(4-carboxybutanamido)phthalic acid (11)

The title compound was afforded as a white solid in 26% yield from 4-aminophthalic acid (5) and glutaroyl dichloride using general procedure D after HPLC purification using linear gradient of 10% B to 40% B over 20 min at a flow rate of 20 ml/min, retention time = 7.6 min. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.59 (brs, 3H), 10.19 (s, 1H), 7.79 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (s, 1H), 2.32 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 2.21 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 1.74 (p, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 174.56, 171.88, 169.58, 168.03, 142.20, 135.84, 130.55, 125.70, 120.00, 118.17, 35.91, 33.36, 20.68. ESI-MS m/z: 296.1 (MH+), 318.1 (MNa+).

RESULTS

Fragment screening

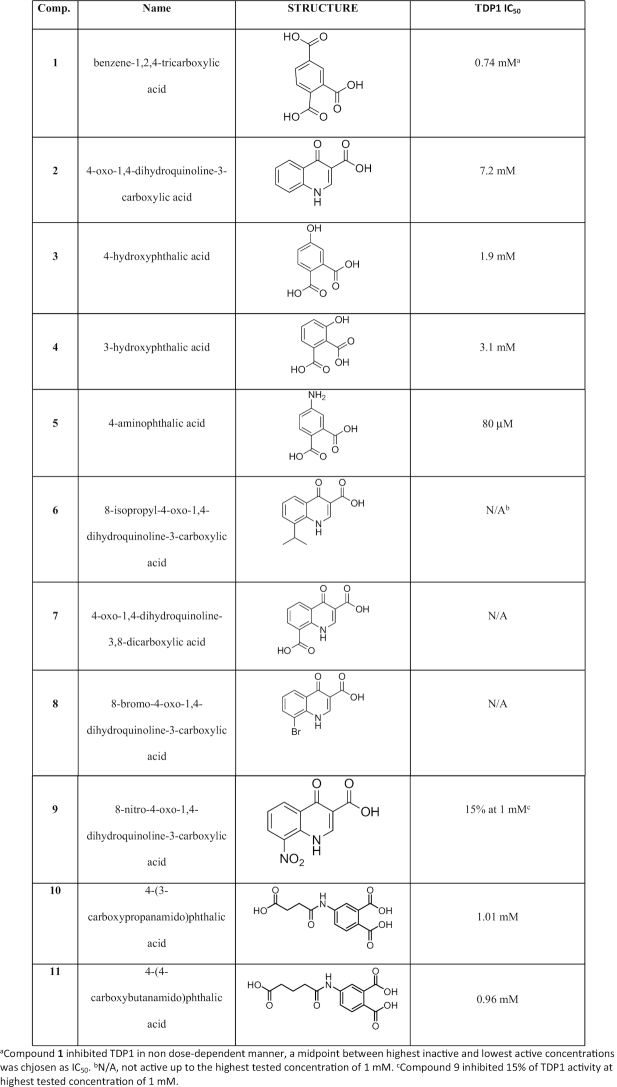

A crystallographic fragment screening campaign targeting TDP1 was conducted using the Zenobia Fragments libraries 1 and 2.2. A total of 640 compounds were divided into cocktails that each contained four fragments. Two fragments, the hydrolysis product of ZT0911, 1,2,4-benzenetricarboxilic acid (1) and fragment ZT1982, 4-hydroxyquinoline-3-carboxylic acid (2), could be unambiguously identified from the Fo-Fc difference electron density maps at 1.63 Å (PDB code: 6DHU) and 1.81 Å resolution (PDB code: 6DIM), respectively (Table 2). To confirm these results, TDP1 crystals were soaked with compounds 1 and 2, individually, and X-ray diffraction datasets were collected at 1.78 Å resolution for both complexes (Figure 2A and B; PDB codes: 6DIE and 6DJD, respectively). In the single component soaks, both fragments bound to several catalytic residues within the active site (57) in the same manner that was observed in the multicomponent soaks. Comparison with previously reported crystal structures of TDP1 reveal no major conformational changes in the protein upon fragment binding.

Figure 2.

(A) Stereoview of the active site of TDP1 from the crystal structure of TDP1 complexed with compound 1 obtained from soaking of TDP1 crystals with ZT0911 alone (single soak, PDB code: 6DIE). TDP1 carbon atoms are colored in gray, nitrogen atoms in blue and oxygen atoms in red. For clarity, some main chain atoms have been removed from selected residues. The carbon atoms of compound 1 are shaded in green. Hydrogen bonds are highlighted as red dashes. The fit of compound 1 and bound waters is shown to the 2Fo-Fc electron density maps (blue) at 1.78 Å resolution and contoured at 1.0σ level. (B) Stereoview of the active site of TDP1–compound 2 complex crystal structure at 1.78 Å obtained after soaking a TDP1 crystal with compound 2 (PDB code: 6DJD, carbon atoms in green). The fit of 2 and bound waters to the 2Fo-Fcmap is shown at 1.0σ level contour. (C) The superimposed coordinates of the active site residues from the crystal structure of the TDP1–compound 1 complex (TDP1 carbon atoms in cyan, fragment carbon atoms in magenta) and TDP1–compound 2 complex (TDP1 carbon atoms in gray, fragment carbon atoms in green) illustrating the unique binding modes of the fragments.

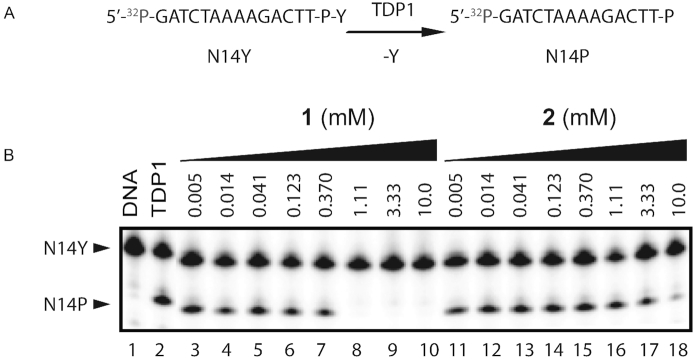

Compound 1 binds to the active site of TDP1 by direct hydrogen bonds involving its carboxylate oxygen atoms with the catalytic residues H263 (3.1 Å hydrogen bond distance), K265 (2.6 Å), N283 (2.8 Å), S399 (2.6 Å), H493 (2.8 Å) and K495 (2.7 Å) (Figure 2A, PDB code: 6DIE). Compound 1 also interacts with the active site via water-mediated bridges between the side chains of S400 and S459 and backbone carbonyl oxygen atoms of P461 and S514. The side chains of Y204 and P461 engage in hydrophobic interactions with compound 1. The observed interactions involve several residues that play important roles in the catalytic activity of TDP1. Specifically, H263 serves as the nucleophile in the first step of the enzymatic reaction, while H493 functions as a general acid-base (see Figure 1). K265, N283 and K495 provide stabilizing interactions for the bound substrate and the transition state species during the reaction, while residues Y204 and S400 have been observed to interact with the DNA portion of the substrate (21,57,58). The fragment was evaluated in a gel-based TDP1 inhibition assay (Figure 3A). For this the 3′ phosphotyrosyl DNA substrate N14Y was incubated with full-length TDP1 in presence of the tested compounds as concentrations up to 10 mM. Formation of the hydrolysis product N14P (Figure 3A) was monitored and analyzed to assess enzyme performance and drug inhibitory potency. Biochemical characterization demonstrates that 1 completely blocks TDP1-catalyzed substrate conversion at concentrations above 1 mM in non-dose-dependent manner (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Inhibition of TDP1 by 1 and 2. (A) Schematic representation 3′ phosphotyrosyl DNA substrate (N14Y) conversion by TDP1 into cleaved products (N14P). (B) Representative gel for inhibition of TDP1-catalized hydrolysis by 1 and 2: lane 1, N14Y only; lane 2, N14Y and TDP1; lanes 3–10 3-fold serial dilution of 1 from 10 mM to 5 μM; lanes 11–18 3-fold serial dilution of 2 from 10 mM to 5 μM.

Compound 2 also binds to the TDP1 active site through several direct hydrogen bonding interactions (Figure 2B, PDB code: 6DJD). The carboxylate oxygen atoms are engaged in hydrogen bonds with the side chains of the catalytic residues K265 (3.0 Å), N283 (2.9 Å) and the hydroxyl group of 2 to H493 (2.6 Å). Three water-mediated bridges between 2 and the active site are also observed: the nitrogen atom of 2 with the side chain of H263 via water 954 (Wa954), the hydroxyl oxygen of 2 with the side chain of S459 via Wa980 and the carboxylate oxygen of 2 with the side chains of K495 and N516 via Wa923. Additionally, the side chains of Y204, P461 and W590 participate in hydrophobic interactions with compound 2. Biochemical measurements indicate that 2 exhibits weak inhibitory activity against TDP1 by nearly completely inhibiting DNA substrate conversion at 10 mM (Figure 3B).

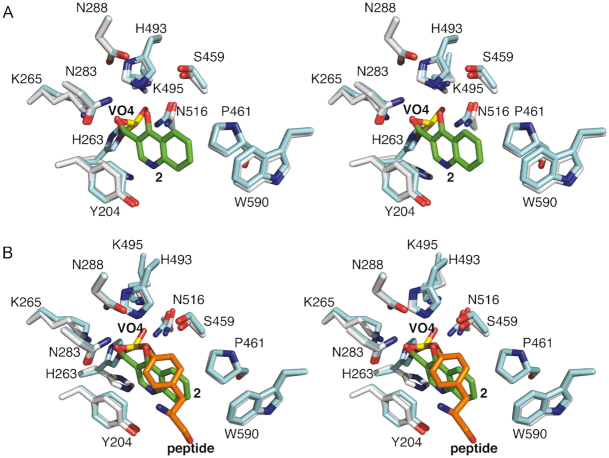

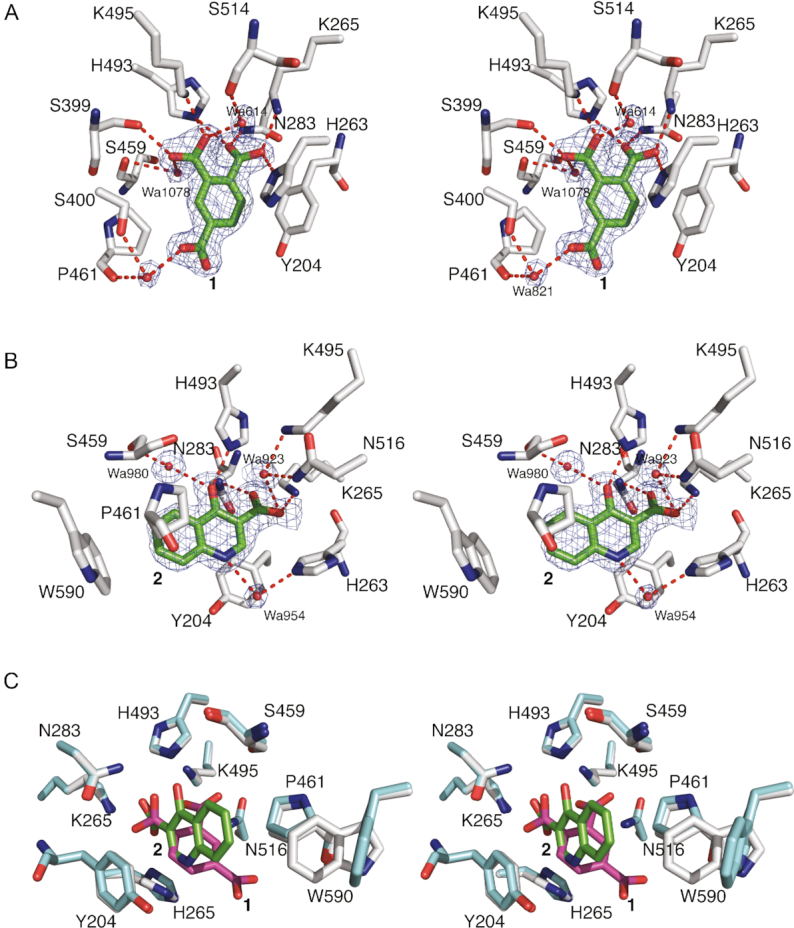

Comparison of binding modes

Compounds 1 and 2 both bind to the active site of TDP1 through several direct hydrogen bonds with some of the key catalytic residues. However, each exhibits a unique binding mode (Figure 2C). A common feature of the two fragments is that the carboxylate moieties occupy the similar position as observed in the crystal structure of TDP1 in complex with vanadate which represents a transition-state mimic (16). In Figure 4A, the coordinates of TDP1 in complex with 1 are superimposed onto the coordinates of the crystal structure of TDP1 complexed with vanadate, DNA substrate and a TOP1 derived peptide (PDB code: 1NOP) (57). Oxygen atoms from both carboxylate moieties of 1 occupy the same space as the oxygen atoms of the vanadate molecule. The vanadate molecule is observed in a trigonal bipyramidal state that mimics the transition state that arises during the SN2 nucleophilic attack on the phosphate atoms in the first step of the enzymatic reaction (57). Compound 1 is observed to interact with the TDP1 K495, N283, H493 and K495 side chains. Similarly, the superimposed coordinates of the TDP1–compound 2 complex with the 1NOP structure reveal one oxygen of the carboxylate moiety of 2 overlaps with the O3 oxygen of the vanadate molecule (Figure 5A). The O3 atom of vanadate makes direct hydrogen bonds with the side chains of N283 and K265, as does the hydroxyl oxygen in 2.

Figure 4.

(A) Superimposed active site residues from the structures of TDP1 complexed with compound 1 (TDP1 carbon atoms in gray, 1 carbon atoms in green, PDB code: 6DIE) and TDP1 with bound vanadate (yellow, PDB code: 1NOP). (B) The same superimposed coordinates now highlighting the position of cytosine 806 from the bound DNA substrate.

Figure 5.

(A) Superimposed active site residues from the structures of TDP1 complexed with compound 2 (TDP1 carbon atoms in gray, 2 carbon atoms in green, PDB code: 6DJD) and TDP1 with bound vanadate (yellow, PDB code: 1NOP). (B) The same superimposed coordinates now highlighting the position of Y723 and L723 from the bound topoisomerase-derived peptide substrate.

While 1 and 2 both bind in the same position as does the vanadate molecule in the 1NOP coordinates, each fragment occupies different spaces with respect to the DNA and topoisomerase-derived peptide components of the substrate. Fragment 1 superimposes with the cytosine 806 base of the DNA substrate (Figure 4B) while fragment 2 overlaps with the Y723 residue of the peptide substrate that is covalently attached to vanadate and mimics the phospho-tyrosine bond (Figure 5B) (57). The two different binding modes of the fragments, combined with the common feature of overlapping with the vanadate binding spot, may present two possible pathways for inhibitor design against TDP1. The carboxylate moieties that interact with the catalytic TDP1 residues can potentially serve as an anchor to the active site while the different binding modes can be taken advantage of in targeting both the DNA and peptide substrate binding sites.

Fragment derivatives

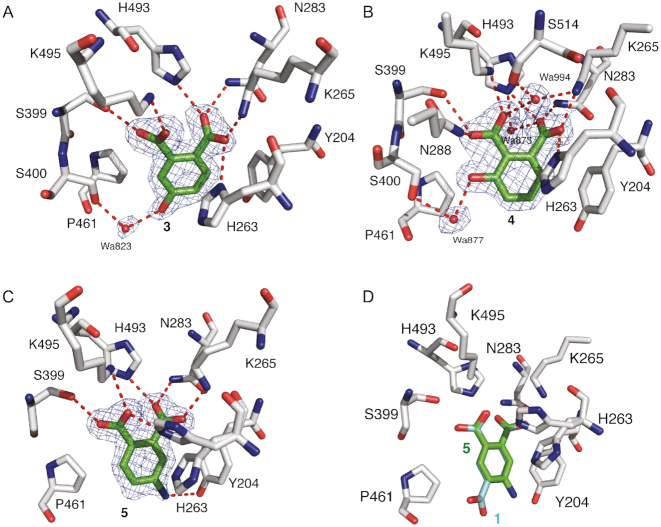

Derivatives of both 1 and 2 were designed to demonstrate the potential for elaboration and optimization of the initial fragment hits. Three derivatives based on the chemical structure of 1 were examined for binding and inhibitory activity against TDP1. Compound 3 (Table 1), which is commercially available from Sigma-Aldrich (PH004941), features a hydroxyl substitution in place of the carboxylate moiety in position 4. The crystal structure of TDP1 complexed to compound 3 (PDB code: 6DIH) at a resolution of 1.78 Å reveals that this derivative retains the direct hydrogen bonding interactions between the carboxylate moieties and the side chains of K495 (2.7 Å), S399 (2.7 Å), H493 (2.7 Å), N283 (2.7 Å) K265 (2.5 Å) and H263 (3.0 Å) (Figure 6A). The hydroxyl at position 4 participates in a water-mediated bridge to the side chain of S400 via Wa823.

Figure 6.

(A) Structure of TDP1 complexed with compound 3, (TDP1 carbon atoms in gray, fragment carbons in green, oxygen atoms in red and nitrogen atoms in blue, PDB code: 6DIH). Hydrogen bond atoms are shown as red dashes. The fit of 3 to the 2Fo-Fc electron density map (blue, 1.78 resolution, 1.0σ level contour) is shown. (B) Structure of TDP1 bound to compound 4 (PDB code: 6DJI). The fit of 4 to the 2Fo-Fc electron density map (blue, 1.75 Å resolution, 1.0σ level contour) is shown. (C) Structure of TDP1 bound to compound 5 at 1.74 Å (PDB code: 6DJJ). The fit of 5 to the 2Fo-Fc electron density map (blue, 1.0σ level contour) is highlighted. (D) Comparison of the binding modes of compound 1 (carbon atom in cyan) and compound 5 (carbon atoms in green).

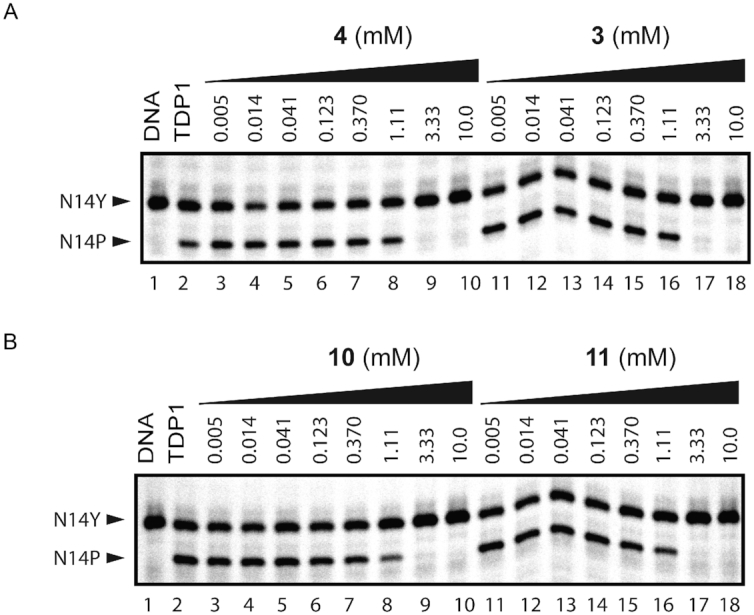

Compound 4 (Table 1) differs from 1 in that the carboxylate moiety at position 4 has been removed and a hydroxyl group has been added at position 3. The 1.75 Å resolution crystal structure of TDP1 bound to 4 (PDB code: 6DJI) revealed that the compound binds to the active site via several direct hydrogen bonds and water-mediated bridges (Figure 6B). The carboxylate at position 1 forms direct hydrogen bonds with the side chains of H493 (2.8 Å) and N283 (2.7 Å), while the carboxylate group at position 2 forms direct hydrogen bonds with the side chain of S399 (3.0 Å), K495 (2.7 Å) and a water-mediated bridge to the backbone carbonyl oxygen of S514 via Wa994. The hydroxyl oxygen at position 3 forms a water-mediated bridge with the side chain hydroxyl of S400 through Wa877. The side chains of Y204 and P461 interact with 4 via hydrophobic interactions. As commonly observed for initial low molecular weight fragments, compounds 3 and 4 exhibited weak potencies with IC50 values of 1.9 and 3.1 mM, respectively (30).

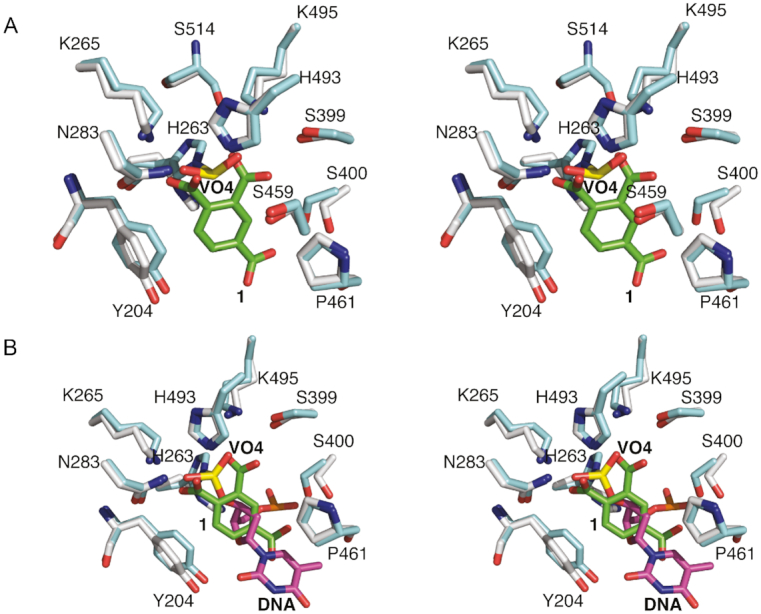

Higher inhibitory activity was observed for compound 5 (Table 1), in which the carboxylate moiety at position 4 in compound 1 was replaced by an amino group. The IC50 in this case was estimated to be ∼80 μM (Figure 7). The 1.74 Å resolution structure of TDP1 complexed to 5 (PDB code: 6DJJ) demonstrates that the amino group substitution enhances the binding such that the amino group is positioned within 3.3 Å of the hydroxyl oxygen of the Y204 side chain residue. In addition, the carboxylate groups at positions 1 and 2 retain direct hydrogen bonding interactions with the side chains of S399 (2.7 Å), K495 (3.0 Å), H263 (2.6 Å), H493 (2.7 Å), N283 (2.7 Å) and K265 (2.6 Å), as in compound 1 (Figure 6C and D). The P461 and Y204 side chains also interact with the aryl portion of 5 via hydrophobic interactions.

Figure 7.

Inhibition of TDP1 by 4-aminonapthoic acid (5). (A) TDP1 inhibition dose response curve (n = 3, error bar not shown for data points where the bar is shorter than the height of the symbol). (B) Representative gel for inhibition of TDP1-catalyzed hydrolysis by 5: lane 1, N14Y only; lane 2, N14Y and TDP1; lanes 3–10 3-fold serial dilution of 5 from 10 mM to 5 μM.

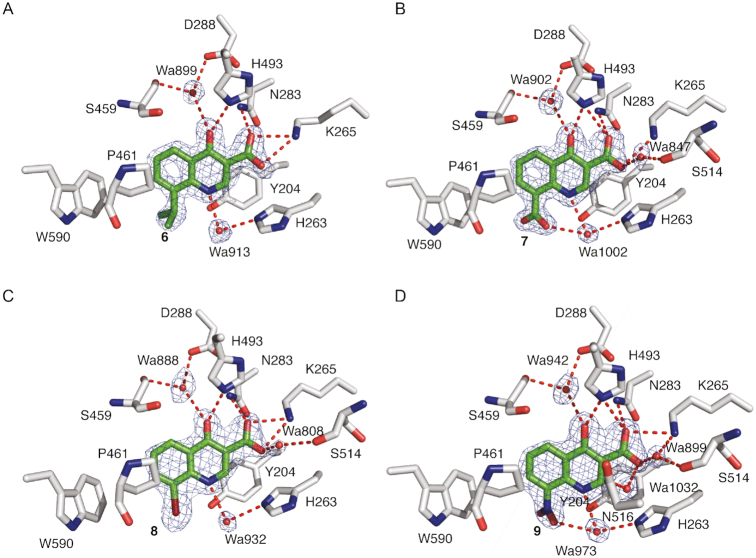

Elaborated fragments based on the chemical scaffold of 2 were also examined. A crystal structure of TDP1 in complex with compound 6 (Sigma-Aldrich compound CDS010292) was solved at 1.70 Å resolution (PDB code: 6DJE). Compound 6 features an isopropyl extension at position 8 (Table 1). The binding mode reveals that the core structure retains the same binding interactions as the parent molecule 2 while the isopropyl substituent extends into the DNA binding region of TDP1 and makes hydrophobic contacts with the side chains of P461 and W590 (Figure 8A). Compound 7 also yielded a high resolution crystal structure (PDB code: 6DJF). It has a carboxylate moiety instead of an isopropyl group at position 8 (Table 1), which also extends into the DNA binding pocket and forms a water-mediated bridge via Wa1002 to the side chain of H263 (Figure 8B). New binding interactions are also observed between the carboxylate oxygen and the backbone carbonyl oxygen of S514 through a water-mediated bridge via Wa847. Compound 8 has a bromine at position 8. A water-mediated bridge via Wa808 between the 8 carboxylate oxygen and the backbone carbonyl oxygen of S514 is observed as well (Figure 8C, PDB code: 6DJH). The structure of TDP1 in complex with compound 9 (PDB code: 6MJ5), a derivative of compound 2 with a nitro group at position 8 (Table 1), reveals that one of the nitro oxygen atoms engages in a water-mediated bridge via Wa973 with the side chain nitrogen of H263. The water-mediated bridge between the carboxylate oxygen and S514 is retained as observed with compounds 7 and 8 (Figure 8D). Therefore, the crystal structures of the fragment 2 derivatives in complex with TDP1 reveal the potential for picking up new interactions with residues in the DNA-binding region via substitutions at position 8 of the parent fragment. However, the derivatives of compound 2 were only weak inhibitors compared to compound 5, a derivative of compound 1. Compounds 6, 7 and 8 did not inhibit TDP1 at 1 mM concentration and incubation of TDP1 with 9 resulted in only 15% TDP1 inhibition at 1 mM.

Figure 8.

(A) Structure of TDP1 complexed with compound 6 (TDP1 carbon atoms in gray, fragment carbons in green, oxygen atoms in red and nitrogen atoms in blue, PDB code: 6DJE). Hydrogen bond atoms are shown as red dashes. The fit of 6 to the 2Fo-Fc electron density map (blue, 1.70 Å resolution, 1.0σ level contour) is shown. (B) Structure of TDP1 bound to compound 7 (PDB code: 6DJF). The fit of 7 to the 2Fo-Fc electron density map (blue, 1.67 Å resolution, 1.0σ level contour) is shown. (C) Structure of TDP1 bound to compound 8 at 1.91 Å (PDB code: 6DJH). The fit of 8 to the 2Fo-Fc electron density map (blue, 1.0σ level contour) is highlighted. (D) Structure of TDP1 bound to compound 9 (PDB code: 6MJ5). The fit of 9 to the 2Fo-Fc electron density map (blue, 1.85 Å resolution, 1.0σ level contour) is shown.

Potential for fragment elongation

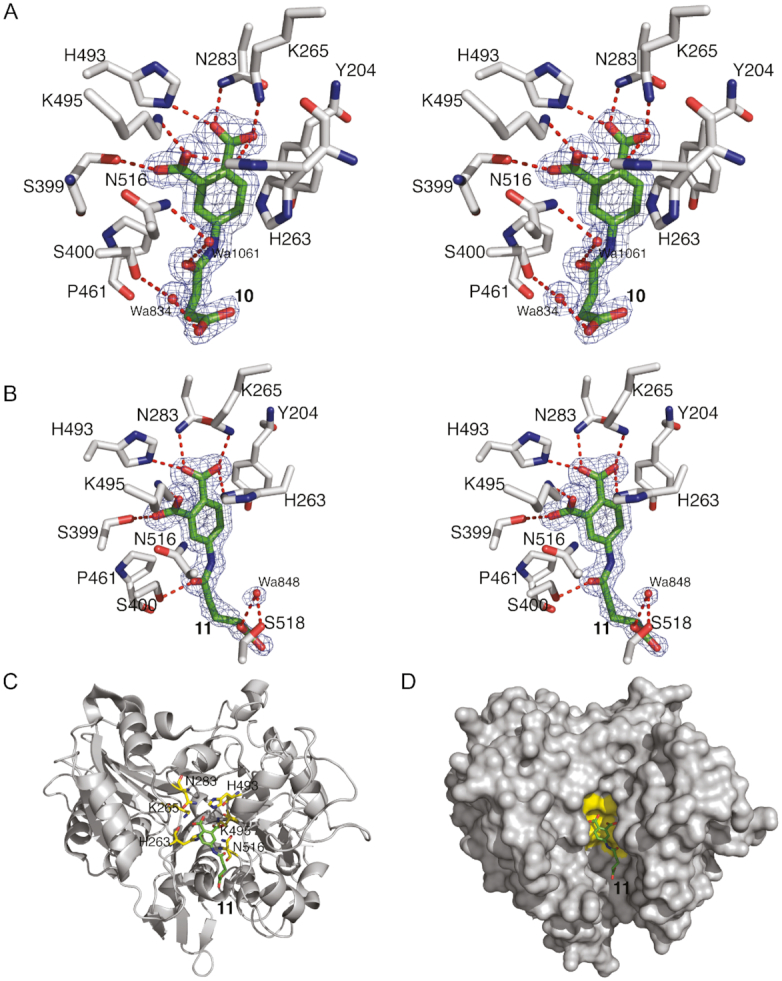

A key step in the fragment approach to drug development is the process of elongating a fragment into a larger compound that can pick up new binding interactions with the target protein. Crystal structures of TDP1 bound to 6, 7, 8 and 9 demonstrate that fragment elongation at the 8-position of the 4-hydroxyquinilone -3-carboxylic acid series can be used to pick up new binding interactions that may enable the fragment to grow into the peptide binding pocket. Additionally, using structure-guided design, we prepared two pthalic acid derivatives, compounds 10 and 11 (Table 1) with linker groups at the fourth position (3-carboxypropanoamido and 4-carboxybutanamido, respectively) that extend into the DNA-binding pocket of TDP1. Compound 10 (Figure 9A, PDB code: 6N17) is anchored in the active site by hydrogen bonds between the 1- and 2- carboxylates to the side chains of H263 (2.6 and 2.8 Å, side-chain existing in two alternate conformations), K265 (2.5 Å), N283 (2.8 Å), S399 (2.7 Å), H493 (2.7 Å) and K495 (2.7 Å). The linker group of 10 picks up two water-mediated hydrogen bond bridges with TDP1. The carbonyl O07 group forms a hydrogen bond to Wa1061 (3.1 Å) which is hydrogen bonded to the ND2 atom of the side chain of N516 (2.9 Å). The O03 atom of 10 is hydrogen bonded to Wa834 (2.6 Å), which forms a water-bridge to the side chain of S400 (3.1 Å). Compound 11 (Figure 9B, PDB code: 6N19) forms hydrogen bonds between the 1- and 2-carboxylates and the side chains of the active site residues H263 (3.0 Å), K265 (2.7 Å), N283 (2.8 Å), S399 (2.8 Å), H493 (2.7 Å) and K495 (2.7 Å). The linker group at the fourth position picks up a direct hydrogen bonding interaction between the carboxylate O08 atom and the side chain of S400 (2.5 Å). Wa848 mediates a water-bridge between the O03 atom (2.6 Å) and the side chain of S518 (2.7Å). These compounds show millimolar inhibition of TDP1 (IC50 values of 1.01 and 0.96 mM, respectively, Figure 10). The addition of a growing linker that picks up new binding interactions demonstrates the potential to use structure-guided design to elongate the fragments into the DNA-binding pocket (Figure 9C and D).

Figure 9.

(A) Stereoview of TDP1 complexed with compound 10 (TDP1 carbon atoms in gray, fragment carbons in green, oxygen atoms in red and nitrogen atoms in blue, PDB code: 6N17). The fit of 10 to the the 2Fo-Fc electron density map (blue, 1.62 Å resolution, 1.0σ level contour) is shown. (B) Stereoview of TDP1 complexed with compound 11 (TDP1 carbon atoms in gray, fragment carbons in green, oxygen atoms in red and nitrogen atoms in blue, PDB code: 6N19). The fit of 11 to the 2Fo-Fc electron density map (blue, 1.50 Å resolution, 1.0 σ level contour) is shown. (C) Ribbon diagram of TDP1 (gray) with the residues of the catalytic HKN motif highlighted in yellow sticks. Compound 11 is shown with carbon atoms in green. (D) Surface representation TDP1 (gray) with the residues of the catalytic HKN motif shaded in yellow. Compound 11 (carbon atoms in green) is shown extending into the TDP1 active site DNA-binding pocket.

Figure 10.

Inhibition of TDP1 by 3, 4, 10 and 11. (A) Representative gel for inhibition of TDP1-catalyzed hydrolysis by 4 and 3: lane 1, N14Y only; lane 2, N14Y and TDP1; lanes 3–10, 3-fold serial dilutions of 4 from 10 mM to 5 μM; lanes 11–18, 3-fold serial dilutions of 3 from 10 mM to 5 μM. (B) Representative gel for inhibition of TDP1-catalyzed hydrolysis by 10 and 11: lane 1, N14Y only; lane 2, N14Y and TDP1; lanes 3–10, 3-fold serial dilutions of 10 from 10 mM to 5 μM; lanes 11–18, 3-fold serial dilution of 11 from 10 mM to 5 μM.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to report crystal structures of organic chemical probes bound to the catalytic site of human TDP1. Two chemically distinct fragments were discovered that bind at the catalytic site as revealed by high resolution crystal structures. Both phthalic acids and quinolone-based fragments engage the catalytic core of TDP1 in a fashion similar to the previously described phosphate mimic vanadate. The difference in the chemical nature of the two fragment classes results in a somewhat different arrangement of their planar aromatic cores and overlapping polar contact networks. This finding points to the fact that polar groups within and in close proximity to the TDP1 catalytic site are capable of forming a broad interaction network with either the substrate or an inhibitor.

Each of the eleven compounds engage one of the two conserved catalytic triad residues of human TDP1 (H263, K265, N283) (Figure 1) (16,58). All phthalic and some 4-hydroxiquinoline-3-carboxylic acid analogues exhibited detectable enzyme inhibition. Their low potency is consistent with the fact that, at this stage, the compounds correspond to low molecular weight fragments (30,39,40). Further improvements in potency, which may be obtained by elaboration of the fragments, will be required before their efficacy can be evaluated in vivo. The greatest inhibitory potency was seen for compound 5, which engages both HKN catalytic triads centered on H263 and H493, respectively (see Figure 1). The higher potency of compound 5 in comparison to other phthalic acid derivatives (compounds 1, 3 and 4) could be attributed to its additional interaction with the edge of the catalytic groove by forming a hydrogen bond with Y204. The crystal structures of TDP1 bound to 10 and 11 also demonstrate that further elaboration of molecules based on the current chemical fragments may lead to larger compounds that pick up additional binding interactions with the TDP1 active site. The crystal structures of TDP1 in complex with the fragments and their derivatives described here finally open the door for structure-based drug design on this important molecular target.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/): 6DHU, 6DIE, 6DIH, 6DIM, 6DJD, 6DJE, 6DJF, 6DJH, 6DJI, 6DJJ, 6MJ5, 6N17, 6N19.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Drs Tinoush Moulaei and Alexander Wlodawer of the Macromolecular Crystallography Laboratory, NCI at Frederick, for providing the TDP1 clone. We thank the Biophysics Resource in the Structural Biophysics Laboratory, NCI at Frederick, for use of the LC/ESMS instrument. X-ray diffraction data were collected at the Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team (SER-CAT) beamlines 22-ID and 22-BM of the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. Supporting institutions may be found at http://www.ser-cat.org/members.html.

Notes

Disclaimer: The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does the mention of trade names, commercial products or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

FUNDING

Federal funds from the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, National Institutes of Health [HHSN261200800001E]; Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research; U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences [W-31-109-Eng-38]. Funding for open access charge: Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Interthal H., Pouliot J.J., Champoux J.J.. The tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase Tdp1 is a member of the phospholipase D superfamily. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001; 98:12009–12014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yang S.W., Burgin A.B. Jr, Huizenga B.N., Robertson C.A., Yao K.C., Nash H.A.. A eukaryotic enzyme that can disjoin dead-end covalent complexes between DNA and type I topoisomerases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996; 93:11534–11539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pommier Y., Sun Y., Huang S.N., Nitiss J.L.. Roles of eukaryotic topoisomerases in transcription, replication and genomic stability. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016; 17:703–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stewart L., Redinbo M.R., Qiu X., Hol W.G., Champoux J.J.. A model for the mechanism of human topoisomerase I. Science. 1998; 279:1534–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pommier Y. Topoisomerase I inhibitors: camptothecins and beyond. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006; 6:789–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Comeaux E.Q., van Waardenburg R.C.. Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase I resolves both naturally and chemically induced DNA adducts and its potential as a therapeutic target. Drug Metab. Rev. 2014; 46:494–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Laev S.S., Salakhutdinov N.F., Lavrik O.I.. Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase inhibitors: progress and potential. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2016; 24:5017–5027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dexheimer T.S., Stephen A.G., Fivash M.J., Fisher R.J., Pommier Y.. The DNA binding and 3′-end preferential activity of human tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010; 38:2444–2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dexheimer T.S., Antony S., Marchand C., Pommier Y.. Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase as a target for anticancer therapy. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2008; 8:381–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marchand C., Huang S.Y., Dexheimer T.S., Lea W.A., Mott B.T., Chergui A., Naumova A., Stephen A.G., Rosenthal A.S., Rai G. et al.. Biochemical assays for the discovery of TDP1 inhibitors. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014; 13:2116–2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beretta G.L., Cossa G., Gatti L., Zunino F., Perego P.. Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1 targeting for modulation of camptothecin-based treatment. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010; 17:1500–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pommier Y., Huang S.Y., Gao R., Das B.B., Murai J., Marchand C.. Tyrosyl-DNA-phosphodiesterases (TDP1 and TDP2). DNA Repair (Amst.). 2014; 19:114–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Interthal H., Chen H.J., Champoux J.J.. Human Tdp1 cleaves a broad spectrum of substrates including phosphoamide linkages. J. Biol. Chem. 2005; 280:36518–36528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kawale A.S., Povirk L.F.. Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterases: rescuing the genome from the risks of relaxation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018; 46:520–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Davies D.R., Interthal H., Champoux J.J., Hol W.G.. The crystal structure of human tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase, Tdp1. Structure. 2002; 10:237–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davies D.R., Interthal H., Champoux J.J., Hol W.G.. Insights into substrate binding and catalytic mechanism of human tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase (Tdp1) from vanadate and tungstate-inhibited structures. J. Mol. Biol. 2002; 324:917–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Murai J., Huang S.Y., Das B.B., Dexheimer T.S., Takeda S., Pommier Y.. Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1 (TDP1) repairs DNA damage induced by topoisomerases I and II and base alkylation in vertebrate cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2012; 287:12848–12857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhou T., Akopiants K., Mohapatra S., Lin P.S., Valerie K., Ramsden D.A., Lees-Miller S.P., Povirk L.F.. Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase and the repair of 3′-phosphoglycolate-terminated DNA double-strand breaks. DNA Repair (Amst.). 2009; 8:901–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Borda M.A., Palmitelli M., Veron G., Gonzalez-Cid M., de Campos Nebel M.. Tyrosyl-DNA-phosphodiesterase I (TDP1) participates in the removal and repair of stabilized-Top2alpha cleavage complexes in human cells. Mutat. Res. 2015; 781:37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nitiss K.C., Malik M., He X., White S.W., Nitiss J.L.. Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase (Tdp1) participates in the repair of Top2-mediated DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006; 103:8953–8958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kiselev E., Dexheimer T.S., Marchand C., Huang S.N., Pommier Y.. Probing the evolutionary conserved residues Y204, F259, S400 and W590 that shape the catalytic groove of human TDP1 for 3′- and 5′-phosphodiester-DNA bond cleavage. DNA Repair (Amst.). 2018; 66–67:64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sacho E.J., Maizels N.. DNA repair factor MRE11/RAD50 cleaves 3′-phosphotyrosyl bonds and resects DNA to repair damage caused by topoisomerase 1 poisons. J. Biol. Chem. 2011; 286:44945–44951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang Y.W., Regairaz M., Seiler J.A., Agama K.K., Doroshow J.H., Pommier Y.. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and XPF-ERCC1 participate in distinct pathways for the repair of topoisomerase I-induced DNA damage in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 39:3607–3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Visconti R., Della Monica R., Grieco D.. Cell cycle checkpoint in cancer: a therapeutically targetable double-edged sword. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016; 35:153–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Day D., Siu L.L.. Approaches to modernize the combination drug development paradigm. Genome Med. 2016; 8:115–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stover E.H., Konstantinopoulos P.A., Matulonis U.A., Swisher E.M.. Biomarkers of response and resistance to DNA repair targeted therapies. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016; 22:5651–5660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dubey R.D., Saneja A., Gupta P.K., Gupta P.N.. Recent advances in drug delivery strategies for improved therapeutic efficacy of gemcitabine. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016; 93:147–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huang S.N., Pommier Y., Marchand C.. Tyrosyl-DNA Phosphodiesterase 1 (Tdp1) inhibitors. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2011; 21:1285–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li-Zhulanov N.S., Zakharenko A.L., Chepanova A.A., Patel J., Zafar A., Volcho K.P., Salakhutdinov N.F., Reynisson J., Leung I.K.H., Lavrik O.I.. A novel class of tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1 inhibitors that contains the octahydro-2H-chromen-4-ol scaffold. Molecules. 2018; 23:2468–2481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Badger J. Crystallographic fragment screening. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012; 841:161–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Patel D., Bauman J.D., Arnold E.. Advantages of crystallographic fragment screening: functional and mechanistic insights from a powerful platform for efficient drug discovery. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2014; 116:92–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Congreve M., Carr R., Murray C., Jhoti H.. A ‘rule of three’ for fragment-based lead discovery?. Drug Discov. Today. 2003; 8:876–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jhoti H., Williams G., Rees D.C., Murray C.W.. The ‘rule of three’ for fragment-based drug discovery: where are we now?. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013; 12:644–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Leach A.R., Hann M.M.. Molecular complexity and fragment-based drug discovery: ten years on. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2011; 15:489–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ludlow R.F., Verdonk M.L., Saini H.K., Tickle I.J., Jhoti H.. Detection of secondary binding sites in proteins using fragment screening. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015; 112:15910–15915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Koh C.Y., Siddaramaiah L.K., Ranade R.M., Nguyen J., Jian T., Zhang Z., Gillespie J.R., Buckner F.S., Verlinde C.L., Fan E. et al.. A binding hotspot in Trypanosoma cruzi histidyl-tRNA synthetase revealed by fragment-based crystallographic cocktail screens. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2015; 71:1684–1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pfaff S.J., Chimenti M.S., Kelly M.J., Arkin M.R.. Biophysical methods for identifying fragment-based inhibitors of protein-protein interactions. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015; 1278:587–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shuker S.B., Hajduk P.J., Meadows R.P., Fesik S.W.. Discovering high-affinity ligands for proteins: SAR by NMR. Science. 1996; 274:1531–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nienaber V.L., Richardson P.L., Klighofer V., Bouska J.J., Giranda V.L., Greer J.. Discovering novel ligands for macromolecules using X-ray crystallographic screening. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000; 18:1105–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Verlinde C.L., Fan E., Shibata S., Zhang Z., Sun Z., Deng W., Ross J., Kim J., Xiao L., Arakaki T.L. et al.. Fragment-based cocktail crystallography by the medical structural genomics of pathogenic protozoa consortium. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2009; 9:1678–1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schiebel J., Krimmer S.G., Rower K., Knorlein A., Wang X., Park A.Y., Stieler M., Ehrmann F.R., Fu K., Radeva N. et al.. High-throughput crystallography: reliable and efficient identification of fragment hits. Structure. 2016; 24:1398–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Raran-Kurussi S., Cherry S., Zhang D., Waugh D.S.. Removal of affinity tags with TEV protease. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017; 1586:221–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kapust R.B., Tozser J., Fox J.D., Anderson D.E., Cherry S., Copeland T.D., Waugh D.S.. Tobacco etch virus protease: mechanism of autolysis and rational design of stable mutants with wild-type catalytic proficiency. Protein Eng. 2001; 14:993–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gasteiger E., Gattiker A., Hoogland C., Ivanyi I., Appel R.D., Bairoch A.. ExPASy: The proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003; 31:3784–3788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gorrec F. The MORPHEUS protein crystallization screen. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009; 42:1035–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Minor W., Cymborowski M., Otwinowski Z., Chruszcz M.. HKL-3000: the integration of data reduction and structure solution–from diffraction images to an initial model in minutes. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2006; 62:859–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zwart P.H., Afonine P.V., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Hung L.W., Ioerger T.R., McCoy A.J., McKee E., Moriarty N.W., Read R.J., Sacchettini J.C et al.. Automated structure solution with the PHENIX suite. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008; 426:419–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Moriarty N.W., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Adams P.D.. electronic Ligand Builder and Optimization Workbench (eLBOW): a tool for ligand coordinate and restraint generation. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2009; 65:1074–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W.G., Cowtan K.. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2010; 66:486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Debreczeni J.E., Emsley P.. Handling ligands with Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2012; 68:425–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Afonine P.V., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Echols N., Headd J.J., Moriarty N.W., Mustyakimov M., Terwilliger T.C., Urzhumtsev A., Zwart P.H., Adams P.D.. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2012; 68:352–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Williams C.J., Headd J.J., Moriarty N.W., Prisant M.G., Videau L.L., Deis L.N., Verma V., Keedy D.A., Hintze B.J., Chen V.B. et al.. MolProbity: more and better reference data for improved all-atom structure validation. Protein Sci. 2018; 27:293–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nguyen T.X., Morrell A., Conda-Sheridan M., Marchand C., Agama K., Bermingham A., Stephen A.G., Chergui A., Naumova A., Fisher R. et al.. Synthesis and biological evaluation of the first dual tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase I (Tdp1)-topoisomerase I (Top1) inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2012; 55:4457–4478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hiraiwa Y., Morinaka A., Fukushima T., Kudo T.. Metallo-beta-lactamase inhibitory activity of 3-alkyloxy and 3-amino phthalic acid derivatives and their combination effect with carbapenem. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013; 21:5841–5850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pasquini S., De Rosa M., Pedani V., Mugnaini C., Guida F., Luongo L., De Chiaro M., Maione S., Dragoni S., Frosini M. et al.. Investigations on the 4-quinolone-3-carboxylic acid motif. 4. Identification of new potent and selective ligands for the cannabinoid type 2 receptor with diverse substitution patterns and antihyperalgesic effects in mice. J. Med. Chem. 2011; 54:5444–5453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Suen Y.F., Robins L., Yang B., Verkman A.S., Nantz M.H., Kurth M.J.. Sulfamoyl-4-oxoquinoline-3-carboxamides: novel potentiators of defective DeltaF508-cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel gating. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006; 16:537–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Davies D.R., Interthal H., Champoux J.J., Hol W.G.. Crystal structure of a transition state mimic for Tdp1 assembled from vanadate, DNA, and a topoisomerase I-derived peptide. Chem. Biol. 2003; 10:139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Raymond A.C., Rideout M.C., Staker B., Hjerrild K., Burgin A.B. Jr. Analysis of human tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase I catalytic residues. J. Mol. Biol. 2004; 338:895–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gould R.G., Jacobs W.A.. The Synthesis of Certain Substituted Quinolines and 5,6-Benzoquinolines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1939; 61:2890–2895. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Peet N.P., Baugh L.E., Sunder S., Lewis J.E.. Synthesis and antiallergic activity of some quinolinones and imidazoquinolinones. J. Med. Chem. 1985; 28:298–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/): 6DHU, 6DIE, 6DIH, 6DIM, 6DJD, 6DJE, 6DJF, 6DJH, 6DJI, 6DJJ, 6MJ5, 6N17, 6N19.