Abstract

We have amassed much structural information on ABC transporters, with hundreds of structures including isolated domains and an increasing array of full-length transporters. The structures captured different steps in the transport cycle and helped design and interpret computational simulations and biophysics experiments. These data provide a maturing, although still incomplete, elucidation of the protein dynamics and mechanisms of substrate selection and transit through the transporters. We present an updated view of the classical alternating access mechanism as it applies to eukaryotic ABC transporters, focusing on type I exporters. Our model helps frame the progress and remaining questions about transporter energetics, how substrates are selected, and ATP is consumed to perform work at the molecular scale. Many human ABC transporters are associated with disease; we highlight progress in understanding their pharmacology from the lens of structural biology, and how this knowledge suggests approaches to pharmacologically targeting these transporters.

Introduction

ATP-binding cassette (ABC) proteins, present across the three domains of life, are characterized by a nucleotide binding domain (NBD) with conserved motifs to bind and hydrolyze ATP1. Most ABC proteins are primary transporters that either import substrates for nutrient uptake across biological membranes or export molecules from the cytosol to extracellular or luminal spaces. Prokaryotic ABC proteins include both importers and exporters1–3. The many eukaryotic ABC genes—e.g. 23 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae4, 48 in human5, and >100 in Arabidopsis thaliana6—are mostly transporters and largely functionally homologous to the prokaryotic exporters, with only a few exceptions, e.g. ABCA47.

Eukaryotic ABC transporters are generally (pseudo) two-fold symmetric structures with two intertwined transmembrane domains (TMDs) connected to two NBDs (Fig. 1a). Each TMD contacts both NBDs, and the NBDs dimerize, forming two ATP-binding sites at their interface. Transient TMD cavities along the symmetry axis perpendicular to the membrane plane participate in substrate translocation.

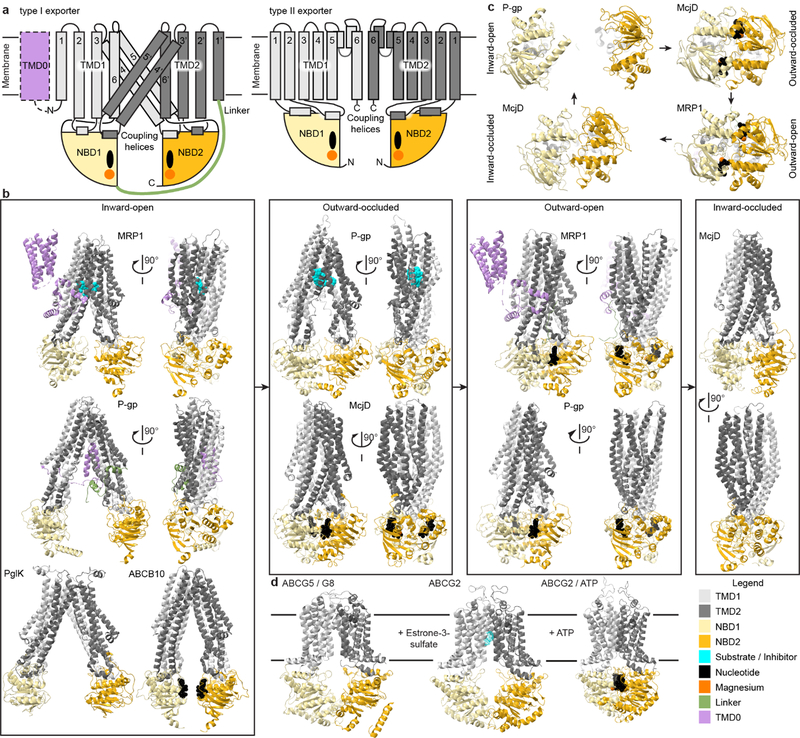

Fig. 1. Structural similarities in ABCB, ABCC and ABCD exporters in contrast to ABCA and ABCG transporters.

(a) Schematic structures of type I (ABCB, ABCC and ABCD; left) and type II (ABCA and ABCG; right) exporters with the core domain consisting of pseudo-symmetric TMDs (dark and light grey) each coupled to an NBD (dark and light yellow) where Mg2+-ATP (orange and black) bind. Some transporters contain an extra TMD0 (lilac) that can modulate the transporter. (b) Representative type I ABC exporter structures loosely binned to represent conformational states in the consensus transport cycle. Inward-open: LTC4-bound bovine MRP1 bound (PDB 5UJA); C. elegans P-gp (PDB 4F4C); C. jejuni PglK (PDB 5C76); AMPPNP-bound human ABCB10 (PDB 4AYX). Outward-occluded: Zosuquidar-bound human-mouse chimeric P-gp (UIC2 Fab not shown) (PDB 6FN1); ATP-bound E. coli McjD (PDB 5OFR). Outward-open: ATP-bound hydrolysis-deficient bovine MRP1 (PDB 6BHU); ATP-bound hydrolysis-deficient human P-gp (PDB 6C0V). Inward-occluded: E. coli McjD (PDB 5OFP). (c) Structures of NBDs during a transport and ATPase cycle viewed from the cytosol looking at the membrane. Clockwise from top left: Separated apo-NBDs in inward-open state (PDB 4F4C); Interacting Mg2+-ATP-bound NBDs in outward-occluded state (PDB 5OFR); ATPase-competent Mg2+-AMPPNP-bound NBD dimer in outward-open state (PDB 2ONJ); Interacting NBDs in inward-occluded state after ADP and phosphate release (PDB 5OFP). (d) Structures of stereotypical type II exporters: nucleotide-free inward-open ABCG5/G8 (left; PDB 5DO7), inward-open ABCG2 with substrate estrone-3-sulfate (middle, PDB 6HCO), and ATP-bound outward-open ABCG2 (right; PDB 6HBU).

Some ABC transporters are encoded in a single polypeptide, others are multi-subunit complexes with single or pairs of domains encoded independently8. Eukaryotic ABC genes form eight subfamilies, ABCA through ABCH, based on sequence homology and domain architecture8,9. ABCE, ABCF and ABCH proteins have no TMDs and participate in processes like DNA repair and translation; we will not discuss them further. The remaining subfamilies form two groups by TMD sequence homology: type I (ABCB, ABCC and ABCD) and type II (ABCA and ABCG)8. This review focuses on type I exporters, for which most progress has been made toward understanding their substrate selection and transport mechanisms. We also highlight recent structures of ABCA and ABCG transporters that provide contrasting or common features between type I and II exporters.

ABC transporters are important drug targets, motivating research on substrate transport mechanics. Since the identification of P-glycoprotein (P-gp; multidrug resistance protein 1 (MDR1); ABCB1) as a multidrug exporter10, several transporters were linked to multidrug resistance in cancers11 and in pathogens12,13. Furthermore, mutations in many human ABC genes cause genetic disorders, e.g. X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (ABCD1), cystic fibrosis (CFTR or ABCC7), Tangier disease (ABCA1), sitosterolemia (ABCG5 and ABCG8)9,14. These disease connections highlight the diverse physiological roles of these proteins5.

Structural characterization of ABC transporters started with crystal structures of isolated NBDs15,16, highlighting similarities across transporters. NBD structures revealed the ATP hydrolysis cycle essential for transport17. Full-length transporter structures, now emerging at an accelerating pace with the methodological advances in electron cryomicroscopy (cryoEM)18,19, deepen our understanding of how the different domains collaborate during substrate transport.

We review the biochemical and structural knowledge of substrate selectivity in type I ABC exporters. This includes their pharmacology and regulation by transport inhibitors and clinically relevant drugs. We propose a consensus model for the conformational changes associated with transport. Incorporating complementary biochemical data, we arrive at a mechanistic model for the thermodynamics of substrate selection and transport, and associated ATP hydrolysis. Finally, we briefly introduce type II transporters to highlight both the common structural features and broad diversity of ABC transporter family.

Consensus model for conformation cycling

Sequence homology and structures of type I ABC exporters suggest that all follow the same flavor of alternating access20, with similar conformational changes between an “inward-facing” state—with the substrate-binding site in the TMDs accessible from the cytosol—and an “outward-facing” state leading to substrate release to the outside (Fig. 1).

The core TMDs of type I exporters include two symmetric or pseudosymmetric sets of six long TM helices, 1–6 and 1’−6’, which extend into the cytosol (Fig. 1a). Domain-swapping of two TMs per repeat generates bundles formed of TMs 1, 2, 3, 4’, 5’, 6 and 1’, 2’, 3’, 4, 5, 6’, respectively. Each NBD interacts with two intracellular loops, one from each TMD. The TM2-TM3 and TM4’-TM5’ loops contain coupling helices 1 and 2, respectively, which interact with the first NBD. Corresponding loops in the second TMD bundle interact with the second NBD.

Fig. 1b groups the example structures mainly into inward- and outward-facing conformations, highlighting large TMD movements between these states. The inward-facing structures, dynamics observed by double electron-electron resonance (DEER) spectroscopy and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations suggest that many ABC transporters exhibit significant flexibility arising from flexing at helix-helix contacts and broken TMD helices, which affects the NBD-NBD distances and substrate-binding cavity sizes21–24. As detailed below, this flexibility allows binding of diverse substrates, and TMD cavity changes upon substrate binding propagate to NBDs via the coupling helices25,26.

Opening of the substrate-binding cavity to the outside and ATP-dependent NBD dimerization define the outward-facing state, with two ATPs bound at the NBD interface27–30 (Fig. 1c). Separation of helices at the TMD apex to open the extracellular gate requires the release of contacts stabilizing the inward-facing state31, which, as explained below, is relevant to substrate-stimulated conformational cycling32.

Several structures represent an “occluded-state” conformation, with a closed extracellular gate and dimerized NBDs (Fig. 1b)33,34. For example, the bacterial exporter McjD crystallized in occluded states without or with bound nucleotide analogues (AMP-PNP and ATP-VO4). Crosslinking and DEER confirmed that these occluded states were represented during the transport cycle, but it remained unclear whether occluded states are stable intermediates for other type I exporters. Recently, P-gp structures were trapped in an occluded state, using a conformation-selective inhibitory antibody (Fig. 1b)26,35. The structures show Zosuquidar26,35 or Taxol35 bound in the enclosed TMD cavity, providing further evidence for the on-pathway occluded states in type I exporters.

By combining structural information from multiple transporters, we can describe a general conformational cycle (Fig. 1b–c). Substrate binding to the inward-facing state facilitates TMD cavity contraction near the cytosol, orienting the NBDs in a pre-dimer configuration (observed by crosslinking P-gp in solution36 and comparing apo- and substrate-bound MRP1 structures37). ATP binding stimulates formation of a hydrolysis-competent NBD dimer, while the TMDs reach an outward-open state (observed by preventing ATP hydrolysis using non-hydrolyzable analogs28 or hydrolysis-deficient mutants27,30). The outward-open state is concomitant with substrate release. Finally, ATP hydrolysis destabilizes the NBD dimer, resetting the transporter to the inward-facing state, for another cycle.

The next steps in defining the conformational cycle for type I exporters are to flesh out the collection of conformational states for a given transporter, and to obtain those data for multiple homologous transporters. Developments in cryoEM38–40 and molecular dynamics (MD)41,42 informed by biophysical techniques promise to accelerate the process.

Binding sites mirror substrate diversity

Type I exporters use a similar scaffold to transport molecules with wide-ranging physicochemical properties43,44. Furthermore, many polyspecific transporters transport disparate substrates. Substrates or inhibitors-bound structures, and complementary biochemistry, are revealing how this evolutionary adaptability of type I exporters is encoded.

Substrate diversity is evident in multidrug export by drug-resistant cancers which brought the identification of P-gp10, Multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1; ABCC1)45 and Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (BCRP; ABCG2)46 as polyspecific drug exporters. Their substrate profiles underlie drug resistance in cancers and pathogens47. Crosslinking showed that a large part of the P-gp TMD cavity interacts with substrates using multiple TMs towards the apex of the inward-facing cavity48–51. Structures of mouse P-gp23,35,52,53 and human MRP137 with bound substrate (or inhibitors) reinforce the notion that the interactions in the cavity are variable. Mapping interactions on an inward-facing model illustrates that substrates consistently bind close to the cavity apex with extended contacts to multiple helices (Fig. 2a), suggesting that interactions at the apex are critical for progression through the conformational cycle.

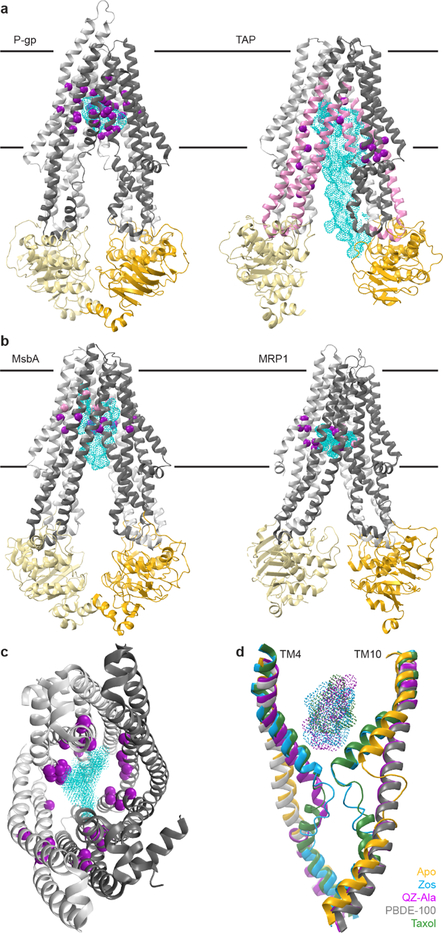

Fig. 2. Experimentally identified substrate-interacting residues suggest binding site diversity among ABC exporters.

(a) Biochemically identified substrate-interacting residues in TAP and P-gp. Left: Zosuquidar-bound P-gp (UIC2 Fab not shown; PDB 6FN1). Purple spheres represent substrate-interacting residues from structure and crosslinking experiments. Right: ICP47-bound TAP (PDB 5U1D). Pink segments crosslinked to substrate peptides. Purple spheres represent crosslinked residues, variants that affect substrate transport and selectivity, and substrate-docking studies. (b) Substrate-bound structures highlight the chemical diversity of interactions distributed across the TMD cavity. Left: LPS-bound E. coli MsbA (PDB 5TV4). Right: LTC4-bound bovine MRP1 (PDB 5UJA). Pink and purple spheres represent substrate-interacting residues forming hydrophobic and polar contacts respectively. (c) TAP and P-gp substrate-interacting residues highlighted in (a) and (b) (purple) mapped onto the TAP TMD cavity viewed from the cytosol (PDB 5U1D). Cyan cloud highlights the combined positions of substrates LTC4 (PDB 5UJA) and Zosuquidar (PDB 6FN1). (d) Substrate-induced changes in TM4 and TM4’/10 with aligned structures of PBDE-100-bound P-gp (gray, PDB 4XWK), apo-P-gp (yellow, PDB 4F4C), Zosuquidar-bound P-gp (blue, PDB 6QEE), Taxol-bound P-gp (green, PDB 6QEX), QZ-Ala-bound P-gp (magenta, PDB 4Q9I), with the corresponding ligands as dotted surfaces. See Supplementary Table 1 for residue lists and references.

TAP (transporter associated with antigen processing; heterodimeric ABCB2–ABCB3) provides another useful case of substrate selection and binding. TAP exports antigenic peptides for loading on major histocompatibility (MHC) Class I for adaptive immunity. Evolution selects for a broad peptide sequence selectivity in TAP for an effective immune system. Mapping on the TAP structure54 the biochemical evidence about its substrate-binding site from studies of allelic variants in chicken and rat, and crosslinking55–61, residues all around the inward-facing TMD cavity affect substrate affinity and selectivity (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, NMR experiments identified specific interactions, conformation, and dynamics of a TAP-bound antigenic peptide62. The peptide is extended, its sidechains forming specific interactions along the TMD cavity. Work on TAP and a homologous bacterial peptide transporter, TmrAB, led to the interesting idea that transporters with broad substrate selectivity have TMD-cavity surfaces with heterogeneous physicochemical properties, enabling distinct subsets of interactions for each substrate63. This is also borne out in MsbA64 and MRP137 structures with substrates lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and leukotriene C4 (LTC4) respectively (Fig. 2b). Mapping contacts identified in TAP or the multidrug transporters illustrates that nearly all TMs participate in substrate interactions (Fig. 2c).

Crosslinking and spectroscopy also identified substrate-induced conformational changes in TMs65–67. In P-gp, TM4 and TM10 kinks and flexible non-helical regions correlate with ligand presence (Fig. 2d). These helix breaks pinch the TMD cavity by increasing substrate interactions, close the intracellular gate, and provide allosteric communication with the NBDs through the coupling helices26,35. In P-gp, competitive inhibitor Zosuquidar promotes helix kinks at different positions compared to substrate Taxol, highlighting the importance of this allosteric pathway in substrate recognition35.

A unique example of substrate binding is PglK, the bacterial transporter that flips lipid-linked oligosaccharides serving as donors in N-linked protein glycosylation. Membrane-facing structural elements and polar residues lining the outward-facing TMD cavity were implicated in transport68. The substrate’s hydrophilic headgroup was proposed to slide through the outward-facing TMD cavity while the hydrophobic moieties slide on the membrane-exposed TMD surface, not requiring substrate binding to the inward-facing state68. MsbA flips a similarly large lipid-linked substrate, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), essential for Gram-negative bacterial outer membranes. Unlike the PglK model, an LPS-bound MsbA structure highlights a large inward-facing TMD cavity with pockets of distinct chemical properties forming substrate contacts (Fig. 2b; see also Fig. 4b)64.

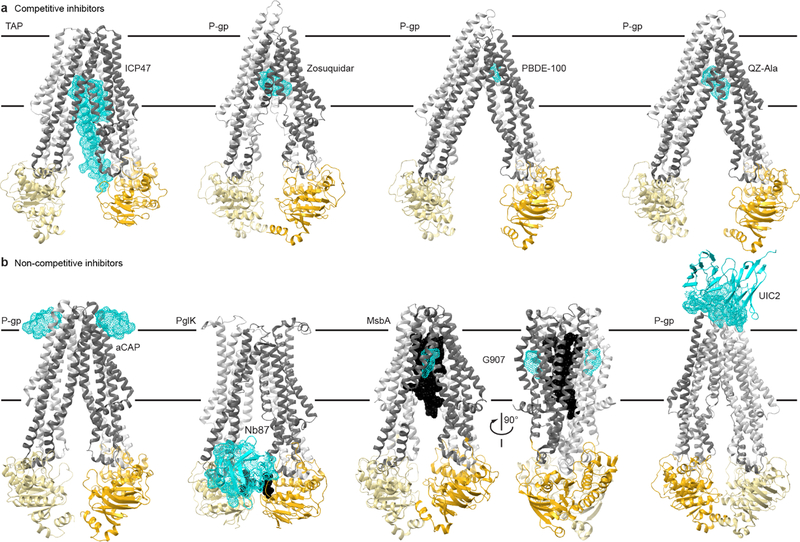

Fig. 4. Structural insights into ABC transporter pharmacology.

(a) Structures of type I exporters bound to competitive inhibitors. From left: the core domains of human TAP bound to ICP47 (PDB 5U1D); chimeric mouse-human P-gp bound to two Zosuquidar molecules, a small-molecule inhibitor (PDB 6QEE); mouse P-gp bound to the marine pollutant PBDE-100 (PDB 4XWK); mouse P-gp bound to two QZ-Ala cyclopeptides (PDB 4Q9I), which may be a competing substrate. (b) Structure of type I exporters bound to non-competitive inhibitors. From left: C. merolae P-gp homodimer bound to two aCAP cyclopeptides (PDB 3WMG); C. jejuni PglK homodimer bound to a single Nb87 nanobody (PDB 5NBD); E. coli MsbA homodimer bound to LPS substrate (black) and two G907 small-molecule inhibitors (PDB 6BPL); chimeric mouse-human P-gp bound to the UIC2 antibody (only the Fv fragment is illustrated and the transporter is rotated ~180° relative to other panels to better view the interface; PDB 6FN4). Color-coding as in Fig. 1, with the inhibitors illustrated as cyan dotted surfaces.

In summary, substrate interactions of type I exporters highlight interfaces dispersed along the TMD cavity, with different substrates likely engaging different residue groups. This large putative substrate-binding surface poses a significant challenge to identify or predict cognate substrates43 and pharmacologically target ABC transporters11,47. These efforts will improve along with our understanding of the substrate interactions and substrate-induced dynamics. Furthermore, the PglK case suggests that substrate-binding sites vary even more than expected and that models of the allosteric ATPase activity stimulation and conformational cycles must account for this. Below we propose a thermodynamic model that helps account for the evolutionary flexibility of substrate-binding site variation.

Transport energetics

A central question is how the ATP binding and hydrolysis cycle by the NBDs15,69 couples to the TMD conformational states. Conserved structural features, and substrate-stimulation of basal ATPase activity across transporters, support a consensus NBD conformational cycle coupled to specific nucleotide states (Fig. 1c). The accumulated data led to several proposed mechanistic models differing in details of how they link ATPase activity to conformational cycling69. We aim to provide a synthesized “consensus” mechanistic model as a general thermodynamic framework to understand the energetic landscape of the transport cycle.

For exporters, because substrate and ATP are in the cytosol, an ensemble of inward-facing state(s)70 must be the resting state where substrate binding is (generally) favored (Fig. 3 step 1). As discussed above and further supported by substrate-docking studies62, substrate binds to the TMD cavity, which raises the question: how does substrate binding affect the transporter’s conformational equilibrium? The TM4 kink induced by ligands that enhance ATPase activity (Fig. 2d)22,67 is intriguing as TM4 connects to the NBD2-interacting coupling helix. P-gp structures with ligands (Taxol35, Zosuquidar26,35 and QZ-Ala67) suggest that this kink enables interactions important for substrate selectivity, and plays an allosteric role in NBD dimerization. Similarly, in an inward-facing C. merolae ABCB1 structure32 this same TM4 region is disordered, and mutations to rigidify it reduced both transport and ATPase activity. Thus, TM4 conformational flexibility is important in gating access to the substrate-binding site and communicating to the NBDs.

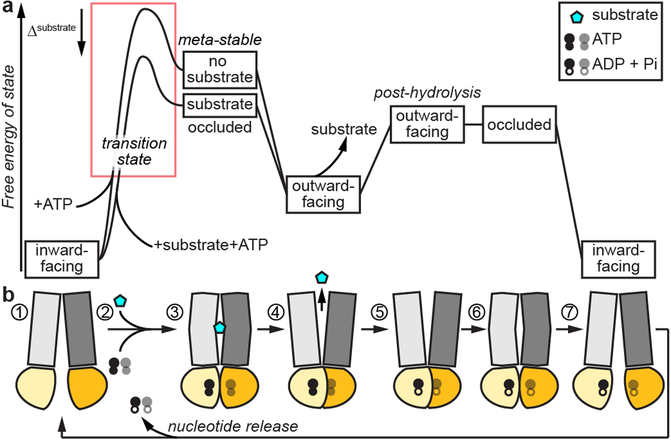

Fig. 3. Consensus thermodynamic model for transport by ABC exporters.

Vertically aligned (a) energy diagram and (b) conformational state schematics for transport cycle of type I ABC exporters. The resting state (1) is inward open. Substrate and ATP binding promotes transition through substrate-bound occluded states (2, 3), to a locally stable outward-open state (4), with an ATP-dependent NBD dimer. Substrate-bound transporters have a lower transition energy (red box), accounting for the observed substrate stimulation. After substrate release (5), ATP hydrolysis destabilizes the NBD dimer and outward-open state, leading the transporter to transition through an occluded state (6) and ending at the inward-open state (7) concomitant with release nucleotide, resetting for another round of transport.

In most if not all type I exporters, ATP binding facilitates NBD dimerization28, which is essential for transport activity. Residues at the TMD apex are important in stabilizing the inward-facing state and can be affected by substrate binding32. Substrate interactions with residues across the TMD cavity stabilize the cytosolic gate constriction. That is, substrate binding reduces the transition energy for ATP-dependent NBD dimerization (Fig. 3 step 2)71.

An alternating access model assumes the existence of occluded states—transitions between the inward- and outward-facing states—in both arms of the transport cycle33,34,72, although these states may be transient. Overall, evidence from most transporters suggest that the outward-facing state is the stable ATP-bound state, placing the occluded state at higher energy (Fig. 3 step 3), with the specific energy differences in a given system producing either a transition state or an intermediate.

NBD dimerization and transition to outward-facing distorts the TMD cavity, repositioning substrate-interacting sidechains, which may decrease affinity of substrate for its binding site. Furthermore, outward opening allows the substrate to equilibrate with the extracellular space. This effectively creates a Brownian ratchet: substrate release allows the TMD to relax to its final outward-open conformation with a distorted substrate-binding site. While substrate release is sometimes referred to as “peristalsis”, a Brownian ratchet-like mechanism does not require a direct force applied to the substrate for its movement across the membrane. Thus, the “power stroke” of substrate transport across membranes is ATP binding and NBD closure (Fig. 3 step 4).

When ATP hydrolysis is inhibited by mutation or vanadate, the outward-facing state is stable, suggesting that ATP hydrolysis is essential to reset to inward-facing. ATP hydrolysis, phosphate and ADP release, or both, lead to NBD dimer destabilization and separation, prompting a reset to inward-facing (Fig. 3 steps 5–7), with the coupling helices coordinating TMD and NBD motions. One exception is caused by mutation to the conserved D-loop aspartate of the TAP1 NBD, which allows transition to inward-facing state without ATP hydrolysis, turning TAP from a one-directional transporter to an exchanger or facilitator73. This exception underscores that ATP hydrolysis ensures unidirectional transport. In addition to the thermodynamic costs, the multi-molecular nature of ATP synthesis (i.e. microscopic reversibility of hydrolysis) and the likely high-energy transition state involving proximal charged inorganic phosphate and ADP provide a kinetic barrier to ATP synthase activity ensuring unidirectional transport by this mechanism.

Combining the above information, we arrive at a consensus cycle (Fig. 3). The transporter rests in an ensemble of low-energy inward-facing state(s). In the basal cycle in the absence of substrate, NBD dimerization has a large activation energy and may represent the rate-limiting step of the conformational cycle74. Substrate binding stimulates change in the TMDs priming NBD dimerization35,37,75. This may be the basis for substrate stimulation of ATP hydrolysis because while the NBD dimer can form in the absence of substrate, substrate binding increases the NBD dimerization rate, therefore ATP hydrolysis. ATP is essential for stable NBD dimerization because the two ATP molecules are central to the interface. Both an ATP-stabilized NBD dimer and substrate bound in the TMD cavity are required to lower the activation energy to transition to outward-facing (or occluded). Substrate is released due to reduced affinity of the TMD cavity for substrate during the transition. ATP hydrolysis then disrupts the NBD dimer, resetting the transporter to initiate the next cycle.

Different transporters vary in details: transition rates correspond to the specific energy of the states, which depends on the protein’s identity and lipid environment33,70. An open question is whether hydrolysis of the two ATPs play independent roles during the conformational cycle. Most studies confirm that a single hydrolysis and phosphate release event destabilizes the NBD dimer, promoting transition to inward-facing. Indeed, in many heterodimeric or pseudosymmetric transporters, the ATPase site asymmetry is genetically encoded, with one site containing consensus ATPase motifs and the other containing degenerate motifs76. While both bind ATP, the degenerate site hydrolyzes less efficiently76. Similarly, the asymmetric BmrCD transporter hydrolyzes one ATP per transport cycle, with the degenerate-site ATP bound through the cycle77,78. In contrast, DEER experiments with P-gp, which has two non-equivalent consensus ATPase sites, suggested that hydrolysis of one ATP couples to the inward-to-occluded transition while the second hydrolysis and phosphate release is essential to reset to the inward-facing state71,79, matching the requirement of our model. The “extra” hydrolysis event, absent in transporters with a single catalytically competent ATPase site, may be coupled to events not described by our consensus model, but one hydrolysis event is always coupled to transporter reset.

Trans-inhibition represents a variation of our model, connecting substrate release and ATP hydrolysis in the outward-facing state, best studied in TAP and its homolog TmrAB29,73. In trans-inhibition, accumulated transported substrate interacts with the TMD’s outward face and inhibits further transporter cycling. This could result from unfavorable substrate release in equilibrium with high concentration of free (transported) substrate, although spectroscopy data indicate that TmrAB accumulates in a substrate-bound occluded state (i.e. Fig. 3 step 3), suggesting allosteric inhibition by accumulated transported substrate29.

Overall, substrate translocation (Fig. 3 steps 1–4) and ATP hydrolysis (Fig. 3 steps 5–7) represent two arms of the conformational cycle. Substrate binding affects the energetics of the system by lowering the activation energy to form the NBD dimer75, which likely represents the rate-limiting step in the absence of substrate. ATP binding is sufficient for substrate translocation, accounting for the “power-stroke” of the transport cycle. However, ATP hydrolysis is essential to reset the system for another round of transport and may be essential to ensure unidirectional transport. This separation may allow for evolutionary divergence of ABC transporters while maintaining standardized ATP hydrolysis sites.

Pharmacology of ABC transporters

The human transporters associated with genetic diseases9,14,80, and drug exporters like P-gp and ABCG2 expressed in drug-resistant cancers11, provide lessons on pharmacologically targeting ABC transporters. Furthermore, TAP is an interesting system with an evolving set of viral inhibitor proteins81,82. We discuss how the structural basis of ABC transporter inhibition by competitive or allosteric inhibitors informs the conformational and thermodynamic descriptions of the transport cycle.

As introduced above, P-gp’s polyspecificity arises from distinct binding modes for different substrates (Fig. 2)48,49. Yet all substrates, by definition, increase the probability of transition to outward-facing leading to transport. Conversely, competitive inhibitors bind without increasing the transition probability, thus inhibiting transport. It is then useful to compare binding sites of substrates and competitive inhibitors, and their respective effects on conformational dynamics. A complication arises in the multidrug resistance field: “inhibitors” are often defined functionally as reducing export of drugs, and some “inhibitors” are actually competing substrates of multidrug exporters83.

P-gp structures with competitive inhibitors reveal interesting inhibitor binding modes (Fig. 4a): (i) P-gp bound to a pollutant, polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDE)–10053; (ii) P-gp bound to various cyclic peptides, some likely substrates, some inhibitors23,67; (iii) P-gp bound to Zosuquidar, a likely competitive inhibitor26,35. PBDE-100 overlaps the substrate-binding site, but interacts deeper in the TMD with aromatic residues implicated in the transition to outward-open32, possibly stabilizing the inward-open state. Structures with cyclic peptides showed two bound molecules, to upper and lower sites—i.e. closer and farther from the extracellular gate—in the TMD cavity (Fig. 4a)67. In contrast, two Zosuquidar molecules are trapped in an occluded cavity, leading to decreased ATPase activity26,35. This stable occluded state is reminiscent of the trans-inhibition mechanism proposed for TmrAB29.

MD simulations showed that binding of a compound in the upper site promoted NBD-dimer closure, whereas lower-site binding did not84. This suggests that substrate interactions within the upper TMD cavity may lower the activation barrier to the outward-facing state with NBD dimerization (Fig. 3 step 2). Similarly in another study, while the NBDs of both apo and substrate-bound P-gp moved toward each other in simulations, only the substrate-bound state NBDs aligned with the closed NBD dimer75. Spectroscopy studies show that transported substrates cause distortions of TM4 or TM4’ to form the NBD dimer66. P-gp structures with some competitive inhibitors show analogous TM4 or TM4’ kinks (Fig. 2d), suggesting these “competitive inhibitors” may be bona-fide substrates. However, spectroscopy experiments show that Zosuquidar inhibits the transition dynamics of inhibitor-bound P-gp, leading to a downstream failure in transport71.

The macrocyclic peptide aCAP, a non-competitive inhibitor, stabilized an inward-facing CmABCB1 structure32 by binding to the TMD exterior near the outer leaflet surface, likely preventing the transition to outward-facing (Fig. 4b). Indeed, biochemical experiments and comparisons with the outward-facing Sav1866 structure85 identified interactions at the TMD apex forming an extracellular gate, which stabilize the inward-facing state and are disrupted when the TMD transitions to outward-facing. aCAP thus allosterically inhibits CmABCB1 by stabilizing the closed extracellular gate, consistent with the idea that substrate binding destabilizes the gate to increase the inward- to outward-facing state switching probability. Furthermore, conformation-specific antibodies or nanobodies act as inhibitors that trap the transporter in specific states and affect the cycle (Fig. 4b)26,86.

MsbA structures with inhibitors G907 or G092 (Fig. 4b)87 reveal a similar allosteric mechanism: G907 binding to TMs 4–6 outside the TMD cavity within the membrane causes TM4 straightening and rigidification, similar to P-gp competitive inhibitor PBDE-100 (Fig. 2d). Furthermore, the NBDs unlatch from the coupling helices, reinforcing the idea that TM4 conformation provides the allosteric pathway between the substrate-binding site and NBD.

Combining the growing repository of structures, MD, and experiments enables drug design in a mechanistic context, to target specific modes-of-action. It will be helpful to classify type I exporter inhibitors based on their mode-of-action like the cystic fibrosis drugs described in Supplementary Note. Viral proteins that evolved to interfere with TAP88 also provide inspiration: TAP structures with bound ICP47 highlight the stabilization of the inward-facing state and occlusion of substrate binding (Fig. 4a)54,89,90. Finally, identifying native substrates of multidrug exporters91 will improve our understanding of these transporters as pharmacological targets.

Type II ABC exporters

Although we focused on type I exporters, we briefly address advances in understanding substrate binding and conformational states for type II exporters. Type I and type II exporters are distinguished by structural differences in the TMDs (Fig. 1a)8. TMs are shorter in type II than in type I exporters, bringing the NBDs closer to the membrane, and an insertion between TM5 and TM6 forms a small extracellular domain92,93. Furthermore, type II TMDs are not intertwined (Fig. 1a): the NBD of each protomer interacts directly with the respective TMD via a membrane-proximal connecting helix preceding TM1 and a coupling helix between TM2 and TM392.

Type II transporters form two subfamilies, ABCA and ABCG. ABCG transporters, homo- or heterodimers with an NBD-TMD topology, transport hydrophobic molecules in different contexts across eukaryotic phyla94,95. ABCG5–ABCG8 and ABCG2 structures highlight the core type II exporter structure in inward- and outward-facing states (Fig. 1d)92,93,96. In inward-facing structures92,93, the TMD flexes proximal to the unliganded NBDs—which stay connected near their C-terminus—to open an inward-facing cavity for substrate binding. Similar to type I, Mg2+-ATP-induced NBD dimerization closes the TMD on the intracellular side96.

ABCG2 structures with estrone-3-sulfate substrate96 or competitive inhibitors MZ29 or MB13697 are inward-facing, similar to the apo structure (Fig. 1d). Analogously to type I exporters, the substrate is tucked high within the inward-facing cavity, whereas the inhibitors extend much lower. In the MZ29 case, two inhibitors are bound; in the case of the larger MB136, a single curved molecule occupies the same space as the two MZ29 molecules. The inhibitors likely act as wedges precluding conformational changes necessary for the transport cycle to proceed, like type I exporter inhibitors ICP47 and glibenclamide (a SUR1 inhibitor; Box 1).

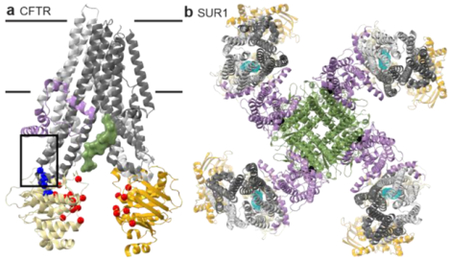

Box 1. “Transporters” that have evolved to perform alternate functions.

CFTR (ABCC7) is an ATP-gated chloride channel in epithelia, mutated in cystic fibrosis (CF)102. SUR1 (ABCC8) and SUR2A/B (ABCC9) are regulatory subunits in the KATP nucleotide-gated potassium channel, a diabetes type 2 drug target103. All three are important pharmacological targets.

CFTR channel opening probability correlates with ATP-dependent NBD dimerization104. Structures in nucleotide-free (closed channel) states resemble classic inward-open structures (figure herein; PDB 5UAK). Rate-limiting NBD dimerization produces a near-classic outward-facing state74,105–108, although the “broken” inner gate forms a pore106,109. ATP hydrolysis destabilizes the NBD dimer, closing the channel. The regulatory or R domain linker between the pseudosymmetric CFTR halves is inhibitory. The unphosphorylated R domain occupies the TMD cavity107, inhibiting NBD closure analogously to ICP47 inhibition of TAP (figure herein, green surface). Phosphorylation releases the R domain, thus relieving CFTR inhibition74,108.

CF mutations decrease CFTR activity and are classified based on molecular phenotype74, with available drugs grouped by mode-of-action. Drug cocktails can therefore match drug mode-of-action to the mutations’ classification110. Mutations form two high-frequency clusters102. The coupling helix-NBD1 interface cluster (figure herein, blue) contains mutations, like ΔF508, that impair folding and are targets of “corrector” drugs that help fold or stabilize CFTR102 (figure herein; corrector binding site boxed). The NBD-NBD interface cluster (figure herein, red) includes mutations, like G551D, that decrease probability of channel opening, and are targets of potentiators like VX-770111,112. Identifying the VX-770 site could provide a strategy for developing ABC transporter activators.

The pancreatic KATP channel—a propeller-shaped octameric complex with four SUR1 blades connecting via their TMD0 to a tetrameric Kir6.2 hub forming the pore113–116 (figure herein; PDB 6BAA; lilac TMD0 and Lasso, green Kir6.2)—plays a critical role in insulin release103. The Lasso domain linking TMD0 to TMD1 also contacts Kir6.2. ATP (not chelating Mg2+; figure herein, black) binds an inhibitory site on Kir6.2 near the Lasso, which likely modulates SUR1-Kir6.2 interactions. The TMD0 and Lasso are homologous to that in MRP1 and CFTR (Lasso only)114,115; these domains mediate physical connections and allosteric coupling between ABC proteins and partners.

Mg2+-ATP (or ADP117,118) binding at the SUR1 nucleotide-binding sites causes NBD and TMD closure and a large rotation of the SUR1 core relative to TMD0116 to open the channel113,115. The diabetes drug glibenclamide inhibits KATP; it binds low within the SUR1 inward-facing cavity similar to type I exporter competitive inhibitors (figure herein)114, preventing NBD and TMD closure116.

The only structure of an ABCA exporter is of ABCA198, the lipid and cholesterol exporter involved in HDL production99. The ABCA1 topology is similar to the ABCG structures, with the following distinctions: ABCA transporters are typically single polypeptides with a TMD-NBD-TMD-NBD organization, and their extracellular domain is larger, formed by large insertions between TM1 and TM2 (and TM7 and TM8), additionally to the TM5-TM6 (and TM11-TM12) loop. The large extracellular domain may aid in forming the nascent HDL.

ABCA1 features mostly separate TMD bundles, with only a narrow interface proximal to the cytosol98. The shallow TMD cavity is positively charged, likely primed to bind lipid headgroups, and the large lipid-exposed TMD surfaces may provide lateral access to lipid substrates for floppase activity. This unusual mechanistic hypothesis98 is only compatible with the type II TMD topology, which lacks the helix-swapping of type I exporters.

Although type I and type II transporters have different TMDs, the overall conformational cycles contain comparable conformations enabled by analogous biochemistry of ATP binding and hydrolysis. Therefore, while the details of inhibitor design will necessarily differ, general principles—like creating large physical wedges that compete with substrate—are transferable between the two types of eukaryotic ABC exporters.

Concluding remarks and future directions

We aimed to consolidate the structural insights on eukaryotic ABC exporters from the last decade. Type I exporter structures readily bin into four primary conformations, yielding a proposed consensus model of transport that is a variation of the classical alternating access mechanism. The model relies on the idea that ATP binding powers transport by facilitating the inward- to outward-facing transition, while substrate binding promotes ATP-bound NBD dimerization. This leads to a higher ATPase rate when substrates are transported, i.e. substrate stimulation. Changes in the binding cavity facilitate substrate release, and ATP hydrolysis destabilizes the NBD dimer, resetting to an inward-open state.

We do not know exactly how binding of ATP and substrate to the inward-facing state are coordinated, although it likely happens via the coupling helices connecting the TMDs to the NBDs through conserved tertiary contacts. While work on isolated NBDs indicates they readily bind nucleotides (e.g.15,76,100), it was surprising that full-length structures of multiple type I exporters determined in the inward-facing state showed no bound nucleotide even when ATP was provided. Substrate binding to the TMDs may increase the affinity of NBDs for nucleotides, although direct evidence for this is still lacking101. Other nucleotide-related questions that will benefit from structural insights include: are one or two ATPs hydrolyzed in a typical transport cycle? How does the ATPase site asymmetry affect nucleotide binding and hydrolysis? How is the free energy of ATP hydrolysis incorporated into the uphill transport of substrates? There are likely important variations on the consensus transport cycle, some of which are becoming clearer with work on non-transporter ABC proteins like CFTR and SUR1 (see Box 1).

In addition to spectroscopic and computational methods such as enhanced sampling in MD, advancements in cryoEM including the ability to identify conformational subpopulations38–40 promise to add thermodynamic and mechanistic detail to models for specific transporters by measuring occupancy of states in populations of molecules.

Mechanistic models as presented here (or others made in similar fashion) are useful for drug design and classification by biophysical mode-of-action26,66,87. This refined design strategy can improve success at addressing the pressing needs for inhibitors of multidrug resistance transporters and modulators to mitigate the effects of mutations in ABC transporters linked to genetic diseases.

Finally, the homologous structures and consensus model also highlight the common evolutionary history of this broad family of transporters. Separation of substrate binding from the overall transport cycle (as evidenced by the commonly observed basal ATPase activity) as featured in our consensus model may represent a fruitful evolutionary strategy. This may be why the ABC transporter superfamily has supported wide evolutionary divergence and a broad substrate repertoire while maintaining a strong coupling of the ATP binding and hydrolysis cycle to stereotyped conformational changes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Murray and members of the Gaudet and Murray labs for insightful discussions. This work was funded in part by NIH grant R01GM120996 (to R.G.).

Footnotes

Competing Interests Statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Ford RC & Beis K Learning the ABCs one at a time: structure and mechanism of ABC transporters. Biochem Soc Trans (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cui J & Davidson AL ABC solute importers in bacteria. Essays Biochem 50, 85–99 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson AL, Dassa E, Orelle C & Chen J Structure, function, and evolution of bacterial ATP-binding cassette systems. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 72, 317–64, table of contents (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Decottignies A & Goffeau A Complete inventory of the yeast ABC proteins. Nat Genet 15, 137–45 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasiliou V, Vasiliou K & Nebert DW Human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family. Hum Genomics 3, 281–90 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia O, Bouige P, Forestier C & Dassa E Inventory and comparative analysis of rice and Arabidopsis ATP-binding cassette (ABC) systems. J Mol Biol 343, 249–65 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quazi F, Lenevich S & Molday RS ABCA4 is an N-retinylidene-phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylethanolamine importer. Nat Commun 3, 925 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiong J, Feng J, Yuan D, Zhou J & Miao W Tracing the structural evolution of eukaryotic ATP binding cassette transporter superfamily. Sci Rep 5, 16724 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Theodoulou FL & Kerr ID ABC transporter research: going strong 40 years on. Biochem Soc Trans 43, 1033–40 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riordan JR et al. Amplification of P-glycoprotein genes in multidrug-resistant mammalian cell lines. Nature 316, 817–9 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robey RW et al. Revisiting the role of ABC transporters in multidrug-resistant cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 18, 452–464 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavalheiro M, Pais P, Galocha M & Teixeira MC Host-Pathogen Interactions Mediated by MDR Transporters in Fungi: As Pleiotropic as it Gets! Genes (Basel) 9(2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du D et al. Multidrug efflux pumps: structure, function and regulation. Nat Rev Microbiol 16, 523–539 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moitra K & Dean M Evolution of ABC transporters by gene duplication and their role in human disease. Biol Chem 392, 29–37 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaudet R & Wiley DC Structure of the ABC ATPase domain of human TAP1, the transporter associated with antigen processing. EMBO J 20, 4964–72 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hung LW et al. Crystal structure of the ATP-binding subunit of an ABC transporter. Nature 396, 703–7 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen J, Lu G, Lin J, Davidson AL & Quiocho FA A tweezers-like motion of the ATP-binding cassette dimer in an ABC transport cycle. Mol Cell 12, 651–61 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scapin G, Potter CS & Carragher B Cryo-EM for Small Molecules Discovery, Design, Understanding, and Application. Cell Chem Biol 25, 1318–1325 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frank J Advances in the field of single-particle cryo-electron microscopy over the last decade. Nat Protoc 12, 209–212 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jardetzky O Simple allosteric model for membrane pumps. Nature 211, 969–70 (1966). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wen PC, Verhalen B, Wilkens S, McHaourab HS & Tajkhorshid E On the origin of large flexibility of P-glycoprotein in the inward-facing state. J Biol Chem 288, 19211–20 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin MS, Oldham ML, Zhang Q & Chen J Crystal structure of the multidrug transporter P-glycoprotein from Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 490, 566–9 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Jaimes KF & Aller SG Refined structures of mouse P-glycoprotein. Protein Sci 23, 34–46 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JY, Yang JG, Zhitnitsky D, Lewinson O & Rees DC Structural basis for heavy metal detoxification by an Atm1-type ABC exporter. Science 343, 1133–6 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esser L et al. Structures of the Multidrug Transporter P-glycoprotein Reveal Asymmetric ATP Binding and the Mechanism of Polyspecificity. J Biol Chem 292, 446–461 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alam A et al. Structure of a zosuquidar and UIC2-bound human-mouse chimeric ABCB1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, E1973–E1982 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson ZL & Chen J ATP Binding Enables Substrate Release from Multidrug Resistance Protein 1. Cell 172, 81–89 e10 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dawson RJ & Locher KP Structure of the multidrug ABC transporter Sav1866 from Staphylococcus aureus in complex with AMP-PNP. FEBS Lett 581, 935–8 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barth K et al. Conformational Coupling and trans-Inhibition in the Human Antigen Transporter Ortholog TmrAB Resolved with Dipolar EPR Spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc 140, 4527–4533 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim Y & Chen J Molecular structure of human P-glycoprotein in the ATP-bound, outward-facing conformation. Science 359, 915–919 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hutter CAJ et al. The extracellular gate shapes the energy profile of an ABC exporter. Nat Commun 10, 2260 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kodan A et al. Structural basis for gating mechanisms of a eukaryotic P-glycoprotein homolog. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, 4049–54 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bountra K et al. Structural basis for antibacterial peptide self-immunity by the bacterial ABC transporter McjD. EMBO J 36, 3062–3079 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choudhury HG et al. Structure of an antibacterial peptide ATP-binding cassette transporter in a novel outward occluded state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, 9145–50 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alam A, Kowal J, Broude E, Roninson I & Locher KP Structural insight into substrate and inhibitor discrimination by human P-glycoprotein. Science 363, 753–756 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loo TW, Bartlett MC & Clarke DM Drug binding in human P-glycoprotein causes conformational changes in both nucleotide-binding domains. J Biol Chem 278, 1575–8 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson ZL & Chen J Structural Basis of Substrate Recognition by the Multidrug Resistance Protein MRP1. Cell 168, 1075–1085 e9 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Penczek PA, Kimmel M & Spahn CM Identifying conformational states of macromolecules by eigen-analysis of resampled cryo-EM images. Structure 19, 1582–90 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loveland AB & Korostelev AA Structural dynamics of protein S1 on the 70S ribosome visualized by ensemble cryo-EM. Methods 137, 55–66 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frank GA et al. Cryo-EM Analysis of the Conformational Landscape of Human P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) During its Catalytic Cycle. Mol Pharmacol 90, 35–41 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harpole TJ & Delemotte L Conformational landscapes of membrane proteins delineated by enhanced sampling molecular dynamics simulations. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 1860, 909–926 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marinelli F & Faraldo-Gomez JD Ensemble-Biased Metadynamics: A Molecular Simulation Method to Sample Experimental Distributions. Biophys J 108, 2779–82 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lefevre F & Boutry M Towards Identification of the Substrates of ATP-Binding Cassette Transporters. Plant Physiol 178, 18–39 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dean M, Rzhetsky A & Allikmets R The human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. Genome Res 11, 1156–66 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cole SP Multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP1, ABCC1), a “multitasking” ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter. J Biol Chem 289, 30880–8 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Litman T, Druley TE, Stein WD & Bates SE From MDR to MXR: new understanding of multidrug resistance systems, their properties and clinical significance. Cell Mol Life Sci 58, 931–59 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pedersen JM et al. Substrate and method dependent inhibition of three ABC-transporters (MDR1, BCRP, and MRP2). Eur J Pharm Sci 103, 70–76 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Loo TW, Bartlett MC & Clarke DM Transmembrane segment 7 of human P-glycoprotein forms part of the drug-binding pocket. Biochem J 399, 351–9 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Loo TW, Bartlett MC & Clarke DM Simultaneous binding of two different drugs in the binding pocket of the human multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein. J Biol Chem 278, 39706–10 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loo TW & Clarke DM Identification of residues within the drug-binding domain of the human multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein by cysteine-scanning mutagenesis and reaction with dibromobimane. J Biol Chem 275, 39272–8 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Loo TW & Clarke DM Thiol-reactive drug substrates of human P-glycoprotein label the same sites to activate ATPase activity in membranes or dodecyl maltoside detergent micelles. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 488, 573–577 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aller SG et al. Structure of P-glycoprotein reveals a molecular basis for poly-specific drug binding. Science 323, 1718–22 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nicklisch SC et al. Global marine pollutants inhibit P-glycoprotein: Environmental levels, inhibitory effects, and cocrystal structure. Sci Adv 2, e1600001 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oldham ML, Grigorieff N & Chen J Structure of the transporter associated with antigen processing trapped by herpes simplex virus. Elife 5, e21829 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lehnert E & Tampe R Structure and Dynamics of Antigenic Peptides in Complex with TAP. Front Immunol 8, 10 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koopmann JO, Post M, Neefjes JJ, Hammerling GJ & Momburg F Translocation of long peptides by transporters associated with antigen processing (TAP). Eur J Immunol 26, 1720–8 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ritz U et al. Impaired transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) function attributable to a single amino acid alteration in the peptide TAP subunit TAP1. J Immunol 170, 941–6 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Armandola EA et al. A point mutation in the human transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP2) alters the peptide transport specificity. Eur J Immunol 26, 1748–55 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baldauf C, Schrodt S, Herget M, Koch J & Tampe R Single residue within the antigen translocation complex TAP controls the epitope repertoire by stabilizing a receptive conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 9135–40 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Geng J, Pogozheva ID, Mosberg HI & Raghavan M Use of Functional Polymorphisms To Elucidate the Peptide Binding Site of TAP Complexes. J Immunol 195, 3436–48 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Deverson EV et al. Functional analysis by site-directed mutagenesis of the complex polymorphism in rat transporter associated with antigen processing. J Immunol 160, 2767–79 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lehnert E et al. Antigenic Peptide Recognition on the Human ABC Transporter TAP Resolved by DNP-Enhanced Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc 138, 13967–13974 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Noll A et al. Crystal structure and mechanistic basis of a functional homolog of the antigen transporter TAP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, E438–E447 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mi W et al. Structural basis of MsbA-mediated lipopolysaccharide transport. Nature 549, 233–237 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Loo TW, Bartlett MC & Clarke DM Substrate-induced conformational changes in the transmembrane segments of human P-glycoprotein. Direct evidence for the substrate-induced fit mechanism for drug binding. J Biol Chem 278, 13603–6 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Spadaccini R, Kaur H, Becker-Baldus J & Glaubitz C The effect of drug binding on specific sites in transmembrane helices 4 and 6 of the ABC exporter MsbA studied by DNP-enhanced solid-state NMR. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 1860, 833–840 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Szewczyk P et al. Snapshots of ligand entry, malleable binding and induced helical movement in P-glycoprotein. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 71, 732–41 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Perez C et al. Structure and mechanism of an active lipid-linked oligosaccharide flippase. Nature 524, 433–8 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Szollosi D, Rose-Sperling D, Hellmich UA & Stockner T Comparison of mechanistic transport cycle models of ABC exporters. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 1860, 818–832 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moeller A et al. Distinct conformational spectrum of homologous multidrug ABC transporters. Structure 23, 450–460 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dastvan R, Mishra S, Peskova YB, Nakamoto RK & McHaourab HS Mechanism of allosteric modulation of P-glycoprotein by transport substrates and inhibitors. Science 364, 689–692 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gu RX et al. Conformational Changes of the Antibacterial Peptide ATP Binding Cassette Transporter McjD Revealed by Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Biochemistry 54, 5989–98 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grossmann N et al. Mechanistic determinants of the directionality and energetics of active export by a heterodimeric ABC transporter. Nat Commun 5, 5419 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Csanady L, Vergani P & Gadsby DC Structure, Gating, and Regulation of the Cftr Anion Channel. Physiol Rev 99, 707–738 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pan L & Aller SG Allosteric Role of Substrate Occupancy Toward the Alignment of P-glycoprotein Nucleotide Binding Domains. Sci Rep 8, 14643 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Procko E, Ferrin-O’Connell I, Ng SL & Gaudet R Distinct structural and functional properties of the ATPase sites in an asymmetric ABC transporter. Mol Cell 24, 51–62 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mishra S et al. Conformational dynamics of the nucleotide binding domains and the power stroke of a heterodimeric ABC transporter. Elife 3, e02740 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Collauto A, Mishra S, Litvinov A, McHaourab HS & Goldfarb D Direct Spectroscopic Detection of ATP Turnover Reveals Mechanistic Divergence of ABC Exporters. Structure 25, 1264–1274 e3 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Verhalen B et al. Energy transduction and alternating access of the mammalian ABC transporter P-glycoprotein. Nature 543, 738–741 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Borst P & Elferink RO Mammalian ABC transporters in health and disease. Annu Rev Biochem 71, 537–92 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Procko E & Gaudet R Antigen processing and presentation: TAPping into ABC transporters. Curr Opin Immunol 21, 84–91 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Eggensperger S & Tampe R The transporter associated with antigen processing: a key player in adaptive immunity. Biol Chem 396, 1059–72 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Palmeira A, Sousa E, H Vasconcelos M & M Pinto M Three decades of P-gp inhibitors: skimming through several generations and scaffolds. Current medicinal chemistry 19, 1946–2025 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ma J & Biggin PC Substrate versus inhibitor dynamics of P-glycoprotein. Proteins 81, 1653–68 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dawson RJ & Locher KP Structure of a bacterial multidrug ABC transporter. Nature 443, 180–5 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Perez C et al. Structural basis of inhibition of lipid-linked oligosaccharide flippase PglK by a conformational nanobody. Sci Rep 7, 46641 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ho H et al. Structural basis for dual-mode inhibition of the ABC transporter MsbA. Nature 557, 196–201 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Praest P, Liaci AM, Forster F & Wiertz E New insights into the structure of the MHC class I peptide-loading complex and mechanisms of TAP inhibition by viral immune evasion proteins. Mol Immunol pii, S0161–5890(18)30099–3 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Herbring V, Baucker A, Trowitzsch S & Tampe R A dual inhibition mechanism of herpesviral ICP47 arresting a conformationally thermostable TAP complex. Sci Rep 6, 36907 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Oldham ML et al. A mechanism of viral immune evasion revealed by cryo-EM analysis of the TAP transporter. Nature 529, 537–40 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Parreira B et al. Persistence of the ABCC6 genes and the emergence of the bony skeleton in vertebrates. Sci Rep 8, 6027 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee JY et al. Crystal structure of the human sterol transporter ABCG5/ABCG8. Nature 533, 561–4 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Taylor NMI et al. Structure of the human multidrug transporter ABCG2. Nature 546, 504–509 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Borghi L, Kang J, Ko D, Lee Y & Martinoia E The role of ABCG-type ABC transporters in phytohormone transport. Biochem Soc Trans 43, 924–30 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Luo YL et al. Tissue expression pattern of ABCG transporter indicates functional roles in reproduction of Toxocara canis. Parasitol Res 117, 775–782 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Manolaridis I et al. Cryo-EM structures of a human ABCG2 mutant trapped in ATP-bound and substrate-bound states. Nature 563, 426–430 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jackson SM et al. Structural basis of small-molecule inhibition of human multidrug transporter ABCG2. Nat Struct Mol Biol 25, 333–340 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Qian H et al. Structure of the Human Lipid Exporter ABCA1. Cell 169, 1228–1239 e10 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lee JY & Parks JS ATP-binding cassette transporter AI and its role in HDL formation. Curr Opin Lipidol 16, 19–25 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Smith PC et al. ATP Binding to the Motor Domain from an ABC Transporter Drives Formation of a Nucleotide Sandwich Dimer. Molecular Cell 10, 139–149 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kodan A et al. Inward- and outward-facing X-ray crystal structures of homodimeric P-glycoprotein CmABCB1. Nat Commun 10, 88 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Molinski SV et al. Comprehensive mapping of cystic fibrosis mutations to CFTR protein identifies mutation clusters and molecular docking predicts corrector binding site. Proteins 86, 833–843 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.de Wet H & Proks P Molecular action of sulphonylureas on KATP channels: a real partnership between drugs and nucleotides. Biochem Soc Trans 43, 901–7 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Vergani P, Lockless SW, Nairn AC & Gadsby DC CFTR channel opening by ATP-driven tight dimerization of its nucleotide-binding domains. Nature 433, 876–80 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhang Z & Chen J Atomic Structure of the Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator. Cell 167, 1586–1597 e9 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhang Z, Liu F & Chen J Conformational Changes of CFTR upon Phosphorylation and ATP Binding. Cell 170, 483–491 e8 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Liu F, Zhang Z, Csanady L, Gadsby DC & Chen J Molecular Structure of the Human CFTR Ion Channel. Cell 169, 85–95 e8 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zhang Z, Liu F & Chen J Molecular structure of the ATP-bound, phosphorylated human CFTR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, 12757–12762 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tordai H, Leveles I & Hegedus T Molecular dynamics of the cryo-EM CFTR structure. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 491, 986–993 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Veit G et al. From CFTR biology toward combinatorial pharmacotherapy: expanded classification of cystic fibrosis mutations. Mol Biol Cell 27, 424–33 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jih KY & Hwang TC Vx-770 potentiates CFTR function by promoting decoupling between the gating cycle and ATP hydrolysis cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 4404–9 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yu H et al. Ivacaftor potentiation of multiple CFTR channels with gating mutations. J Cyst Fibros 11, 237–45 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Li N et al. Structure of a Pancreatic ATP-Sensitive Potassium Channel. Cell 168, 101–110 e10 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Martin GM, Kandasamy B, DiMaio F, Yoshioka C & Shyng SL Anti-diabetic drug binding site in a mammalian KATP channel revealed by Cryo-EM. Elife 6, e31054 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Martin GM et al. Cryo-EM structure of the ATP-sensitive potassium channel illuminates mechanisms of assembly and gating. Elife 6, e24149 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lee KPK, Chen J & MacKinnon R Molecular structure of human KATP in complex with ATP and ADP. Elife 6(2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Nichols CG KATP channels as molecular sensors of cellular metabolism. Nature 440, 470–6 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Vedovato N, Ashcroft FM & Puljung MC The Nucleotide-Binding Sites of SUR1: A Mechanistic Model. Biophys J 109, 2452–2460 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.