Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

The aim of this study was to characterize variation in the gut microbiome of women with locally advanced cervical cancer and compare it to healthy controls.

METHODS:

We characterized the 16S rDNA fecal microbiome in 42 cervical cancer patients and 46 healthy female controls. Shannon diversity index (SDI) was used to evaluate alpha (within sample) diversity. Beta (between sample) diversity was examined using principle coordinate analysis (PCoA) of unweighted Unifrac distances. Relative abundance of microbial taxa was compared between samples using Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size (LEfSe).

RESULTS:

Within cervical cancer patients, bacterial alpha diversity was positively correlated with age (p = 0.22) but exhibited an inverse relationship in control subjects (p < 0.01). Alpha diversity was significantly higher in cervical cancer patients as compared to controls (p < 0.05), though stratification by age suggested this relationship was restricted to older women (>50 years; p < 0.01). Beta diversity (unweighted Unifrac; p < 0.01) also significantly differed between cervical cancer patients and controls. Based on age- and race-adjusted LEfSe analysis, multiple taxa significantly differed between cervical cancer patients and controls. Prevotella, Porphyromonas, and Dialister were significantly enriched in cervical cancer patients, while Bacteroides, Alistipes and members of the Lachnospiracea family were significantly enriched in healthy subjects.

CONCLUSION:

Our study suggests differences in gut microbiota diversity and composition between cervical cancer patients and controls. Associations within the gut microbiome by age may reflect etiologic/clinical differences. These findings provide rationale for further study of the gut microbiome in cervical cancer.

Keywords: Cervical cancer, Gynecologic cancer, Gut microbiota, Microbiome

Introduction

Cervical cancer continues to be the most common gynecologic cancer globally. The American Cancer Society estimates more than 13,100 new cases of invasive cervical cancer will be diagnosed in the United States in 2019, resulting in more than 4,250 deaths.1 A previously published review by Chase et al. highlighted an important gap in studies investigating the association between the gut microbiome and gynecologic cancers.2 The gut microbiome is proposed to alter host immunity by modulating multiple immunologic pathways, thus impacting cancer risk and treatment outcomes in various malignancies;3–5 however, the relationship between the gut microbiome and cervical cancer has not been reported.

Previous studies theorized that host-dependent immunologic status and human papillomavirus (HPV)-induced immune evasion are responsible for persistent HPV infection and the subsequent development of cervical dysplasia.6 Independent of HPV status, the immune system’s capability to recognize tumor antigens and clear an oncogenic HPV infection ultimately determines whether a patient develops cervical cancer.7 The ability of high risk HPV to downregulate interferon signaling favors HPV persistence and the development of cervical cancer and its precursor lesions.7,8 Previous evidence supports that a more diverse, abundant gut microbiota with distinct composition can lead to improved anti-tumoral immune response by priming anti-tumoral T cell activation.9 In melanoma patients treated with anti-programmed cell death 1 protein (PD-1) immunotherapy, Gopalakrishnan et al. demonstrated that patients with a favorable baseline gut microbiome (high diversity and abundance of Ruminococcaceae and Faecalibacterium) exhibit enhanced systemic and antitumor immune responses mediated by increased antigen presentation and improved effector T cell function.10 Noting that gut microbial differences could affect cervical cancer risk and treatment through several pathways, we aimed to characterize variations in the fecal or gut microbiome of women with locally advanced cervical cancer. In doing so, we hope to clarify differences in gut microbial diversity and composition within and between cervical cancer patients as compared to cancer-free controls; laying the groundwork for further research aimed at exploring the role of the gut microbiota in cervical cancer risk and treatment.

Materials and Methods

Participants and clinical data

Gut microbiome samples for cervical cancer patients were collected on an IRB approved prospective protocol (MDACC 2014-0543) for patients with biopsy-proven carcinoma of the cervix treated at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and Harris Health System, Lyndon B. Johnson General Hospital Oncology Clinic between September 22, 2015 and December 21, 2017. Female controls that were comparable to cases in regard to age, race and body mass index (BMI), were derived from the Houston, TX community and medical center catchment area. Control ineligibility criteria included current smoker, antibiotic use within the past month, incident or prevalent cancer other than non-melanoma skin cancer, one or more chronic conditions that restricts dietary intake (e.g., Celiac disease), major intestinal surgery (e.g., gastric bypass), and currently pregnant or lactating women. Medical history and current medication use were assessed via an in-person interview with a clinical provider or trained study staff. All cancer patients had a new diagnosis of locally advanced, non-metastatic carcinoma of the cervix and underwent definitive chemoradiation (CRT) with external beam radiation therapy followed by brachytherapy, but samples used for this study were collected prior to any cancer therapy. Medical records were reviewed to obtain demographic and clinico-pathologic data.

Sample collection and DNA extraction

For the cervical cancer patients undergoing definitive CRT, stool from an in clinic rectal exam performed prior to cancer therapy were collected using a matrix designed quick release Isohelix swab. Isohelix swabs were placed in 20 μL of protease K and 400 μL of lysis buffer (Isohelix) and stored at −80°C within 1 hour of sample collection. Control participants provided stool samples using an in-home collection kit with a sterile swab and tube, a comparable method.11,12 Control participants were provided a kit with detailed instructions to collect a stool sample. Following defecation into a plastic “toilet hat,” a sterile culture swab and tube with no media was used to collect a small portion of the sample. Samples were either Express (overnight or same day) shipped or brought to their next scheduled visit. All fecal samples were received <48 hours from collection, stored at −80°C, and processed within one year of collection.13 Bacterial genomic DNA was extracted using MO BIO PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (MO BIO Laboratories).

16S rRNA gene sequencing and sequence data processing

16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed by the Alkek Center for Metagenomics and Microbiome Research at Baylor College of Medicine. 16S rRNA was sequenced using methods adapted from those used for the Human Microbiome Project.14 The 16S rDNA V4 region was amplified by PCR using primers that contained sequencing adapters and single-end barcodes, allowing pooling and direct sequencing of PCR products. Amplicons were sequenced on the MiSeq platform (Illumina) using the 2x250 bp paired-end protocol, yielding paired-end reads that overlapped almost completely. Sequence reads were demultiplexed, quality filtered, and subsequently merged using USEARCH version 7.0.1090 (4). 16S rRNA gene sequences were clustered into OTUs at a similarity cutoff value of 97% using the UP ARSE algorithm.15 To generate taxonomies, OTUs were mapped to an optimized version of the SILVA rRNA database containing the 16S v4 region. A custom script was used to construct an OTU table from the output files generated as described above for downstream analyses of alpha-diversity, beta-diversity, and phylogenetic trends. PCOa analysis was performed by institution and sample set to ensure no batch effects were present.

Statistical analyses

For microbiome analysis, rarefaction depth was set at 5121 reads. Shannon diversity index was used to evaluate alpha (within sample) diversity. Beta (between sample) diversity was examined using principle coordinate analysis (PCoA) of unweighted Unifrac distances. Relative abundance of microbial taxa and genera was compared between cases and controls; and differentially abundant bacterial genera by case status were determined using Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) Effect Size (LEfSe),16 applying the one-against-all strategy with a threshold of 3 on the logarithmic LDA score for discriminative features and α of 0.05 for factorial Kruskal-Wallis test among classes. LEfSe was restricted to bacteria present in 20% or more of the study population. Due to variations in gut microbiota diversity with age, microbial associations were assessed by age strata the approximate overall mean (<=50 vs. >50 years).

Results

We characterized the 16S rDNA fecal microbiome in 42 cervical cancer patients. Their clinico-pathologic data are summarized in Table 1. Cervical cancer cases were staged according to the Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) 2014 staging system. Overall, approximately 64% of the patients (27 of 42) had advanced stage disease (stage IIB, or greater) and the majority of patients had squamous cell cancers with moderate or poor differentiation. With respect to HPV status, HPV-16 was the most frequent genotype (47.6%), followed by HPV-18 (23.8%), and other high-risk HPV (7.1%). HPV status was unknown in 21.4% of cancer patients. On pretreatment imaging, the largest tumor dimension and highest node level were identified. Using the short axis diameter, we found that the median cervical tumor size was 5.37 cm (range 1.2-11.5 cm). Thirty patients (71%) were identified as having positive pelvic or para-aortic lymph nodes by positron emission tomography (PET) or computerized tomography (CT) scan.

Table 1.

Clinical-pathological Features of Cervical Cancer Cases

| Cancer stage, % | |

| IA1-IA2 | 2.4 |

| IB1 | 11.9 |

| IB2 | 14.3 |

| IIA | 7.1 |

| IIB | 40.5 |

| IIIA | 0.0 |

| IIIB | 16.7 |

| IVA | 7.1 |

| IVB | 0.0 |

| Histology, % | |

| Squamous Cell | 78.2 |

| Carcinoma | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 18.2 |

| Adenosquamous | 3.6 |

| Carcinoma | |

| Tumor Grade, % | |

| 1 | 5.5 |

| 2 | 36.4 |

| 3 | 45.4 |

| Unknown | 12.7 |

All column values are percentage unless indicated otherwise (n=42)

The 16Sv4 fecal microbiota was first analyzed in cancer cases with respect to age. Bacterial α-diversity as measured by SDI showed a trend to increase with age in women diagnosed with cervical cancer although this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.22) (Figure 1A). Given this trend, to further investigate differences by age, we divided subjects into two age groups (<=50 vs. >50 years). There was no difference in the bacterial community composition (β-diversity) between younger and older women (p = 0.55) (Figure 1B). The top 10 most abundant genera in fecal samples was similar among all cervical cancer patients (Figure 1C), suggesting that bacterial taxa dominance does not vary by age.

Figure 1.

The fecal microbiota of individuals with cervical cancer.

The Shannon diversity index showed a trend to increase with age in cervical cancer subjects but did not reach statistical significance. B) Bacterial community composition does not vary between younger and older individuals with cervical cancer as determined by PCoA of the unweighted UniFrac distance. C) Stacked bar plot of the top 10 most abundant order-level bacteria in cervical cancer patients. Each bar represents a single participant and is labeled with subject age.

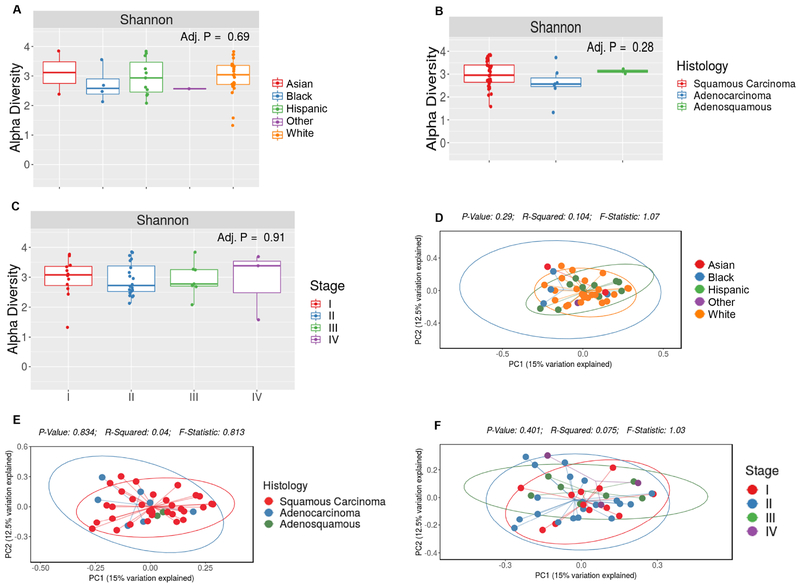

We next compared bacterial diversity and taxa abundance with regards to race/ethnicity, histology and disease stage among cervical cancer patients. Neither α-diversity (p = 0.69) nor beta-diversity (p = 0.64) varied by race in our patient group (Figure 2A, D). We also found no difference in α- or β-diversity according to histology (p = 0.28 for SDI α-diversity and p = 0.83 for unweighted Unifrac β-diversity) (Figure 2B, E). Comparing across cancer stage, we again observed no difference in α-diversity (p = 0.91) (Figure 2D) or β-diversity (unweighted Unifrac; p = 0.40) (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

The fecal microbiota of individuals with cervical cancer by demographics.

Alpha diversity (within sample diversity) was measured using the Shannon diversity index and Beta diversity (between sample diversity) was determined by unweighted Unifrac. No differences were observed in either metric by race (A,D), histology (B,E) or cancer stage (C,F).

We then sought to extend our analysis to characterize variations in the gut microbiome of women with and without locally advanced cervical cancer. We compared the 16S rDNA fecal microbiome of our 42 cervical cancer patients to 46 healthy cancer-free female controls. Clinical and demographic characteristics are displayed in Table 2. Race/ethnicity, age, and BMI were similar between cervical cancer and control groups with the majority of patients being non-Hispanic white, with a mean age of 48.9 vs. 48.9 years (p > 0.99) and a mean BMI of 29.0 vs. 29.6 kg/m2 (p = 0.71) respectively.

Table 2.

Selected characteristics of cervical cancer cases vs controls.

| Cervical Cancer Status | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Cases (n=42) | Controls (n=46) | P-value* |

| Mean Age (SD)–yr | 48.9 (10.4) | 48.9 (13.7) | >0.99 |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 29.0 (6.6) | 29.6 (8.3) | 0.71 |

| Race, % | |||

| White | 57.1 | 53.2 | 0.72 |

| Black | 9.5 | 25.5 | 0.06 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 26.2 | 13.0 | 0.12 |

| Asian | 4.8 | 2.2 | 0.51 |

| Other | 2.4 | 4.3 | 0.62 |

P values were based on t test (continuous variables) or z-test (proportions). All tests were two-sided.

Comparing cervical cancer patients and controls, we observed statistically significant differences in α-diversity as measured by SDI (p < 0.05) (Figure 3A). Stratification by age revealed differences in α-diversity were limited to women over 50 years (p < 0.01) (Figure 3B); hence, we examined the relationship between α-diversity and age among healthy controls alone. In contrast to cancer patients, SDI was inversely associated with age in control subjects (p < 0.01) (Figure 3C). Given these findings, we further examined community composition in cervical cancer patients and controls. As with α-diversity, overall β-diversity differed significantly by cancer status (unweighted Unifrac; p < 0.01), but this relationship was evident in both younger and older age groups (p < 0.01 for both) (Figure 3D, E).

Figure 3.

The fecal microbiota of individuals with cervical cancer is statistically significantly different from that of healthy individuals.

A) Overall alpha diversity, as assessed by Shannon diversity in cervical cancer patient’s vs. controls. B) Alpha diversity, as assessed by Shannon diversity in cervical cancer patient’s vs. controls stratified by age group. C) Shannon alpha-diversity index decreased with age in control subjects (p < 0.01). D,E) Beta diversity, as assessed by unweighted UniFrac, demonstrates significant compositional differences at the community level in cervical cancer patients vs. controls regardless of age.

In addition to diversity, we used LEfSe analysis to identify bacterial genera that were differentially enriched between cervical cancer cases and control patients (p < 0.05, LDA score > 3) (Figure 4A). LEfSe identified Prevotella, Porphyromonas, and Dialister as significantly enriched in cervical cancer samples. In analyses independently adjusted for age and race, LEfSe continued to identified Prevotella, Porphyromonas, and Dialister as significantly enriched in cervical cancer samples, while Blantia, Alistipes and members of the Lachnospiracea family were preferentially more abundant in controls (p < 0.05, LDA score > 3) (Figure 4C, D).

Figure 4.

LEfSe analysis identified the most differentially abundant taxa between cervical cancer and healthy controls.

A,B,C) Histogram of the linear discriminant analysis (LDA) scores unadjusted (A), and adjusted for age (B) and race (C) demonstrates significant compositional differences across a range of taxa in cervical cancer patients (green) vs. controls (red). LEfSe was restricted to p < 0.05 for class and subclass analysis and a minimum LDA score of 3.0.

Discussion:

In this study, we sought to characterize the gut microbiome of women with cervical cancer. We hypothesized that cervical cancer patients would have a microbiome distinct from cancer free controls, which would be more pronounced in higher staged disease. We found that diversity of the fecal microbiome in cervical cancer patients differed between young and older women. We observed significant differences in α and β diversity between cervical cancer patients and controls, suggesting compositional differences in the gut microbiota. Among cases only, overall analysis of α and β diversity did not differ in regards to race, histology or stage.

In a recently published study, Wang et al. compared the gut microbiome between eight cervical cancer patients and five healthy controls.17 The study demonstrated an increasing trend in gut microbiota α-diversity in cervical cancer patients, although statistical significance was not reached. With respect to β-diversity, the authors reported a clear separation between cervical cancer patients and healthy controls. Additionally the study identified several genera that differed significantly between cervical cancer patients and healthy controls, mainly, that members of the phylum Proteobacteria were notably higher in cervical cancer patients.17 Our larger analysis of the gut microbiome in cervical cancer patients vs. normal controls revealed analogous findings. We observed a statistically significant higher α-diversity in cervical cancer patients, particularly in elderly patients, than healthy controls. Furthermore, we report a statistically significant difference in β-diversity between cervical cancer patients and controls, confirming compositional differences in the gut microbiota according to health status. Our US based study investigating differences in the gut microbiome between cervical cancer patients and normal controls revealed dissimilarities in the relative abundance of specific taxa in cervical cancer patients than those found in the smaller study by Wang et al, namely Prevotella, Porphyromonas, and Dialister. These differences all likely due to ethnicity or population-specific variations in gut microbiome composition, as previously reported, and support the need for geographically tailored approaches to microbiome analysis.18

Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota may be implicated in carcinogenesis, therapy-related side effects and treatment outcomes in cervical cancer.2,5 Ahn et al. found an increased presence of Fusobacterium and Porphyromonas in individuals with colorectal cancer compared to normal controls.19 Coker et al. found the genus Dialister to be higher in the gastric mucosa of gastric cancer patients;20 which correlated with disease progression when compared to precancerous subjects. Ritu et al. recently investigated the association between the cervical microbiota and HPV infection status in cytologically normal women using 16S-based sequencing. They found Dialister to be positively associated with a newly acquired HPV infection, HPV persistence, and negatively associated with the clearance of HPV.21 The authors suggest taxa associated with HPV infection status could serve as a biomarker to help forecast the risk of developing a persistent HPV infection. These reports coupled with our findings suggest a plausible role of the genus Dialister in cervical cancer.

Interestingly, studies in humans have linked the relative abundance of Prevotella at mucosal sites to a variety of inflammatory disorders, including bacterial vaginosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and periodontitis.22–24 These diseases are thought to be associated with a Prevotella-mediated inflammatory process facilitated by T helper type 17 (Th17).25 Studies suggest that Prevotella rich environments stimulate dendritic cells (DC) through Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) to release of interleukin-1b (IL-1b), IL-6 and IL-23, which in turn facilitates IL-17 production by T helper 17 (Th17) cells to activate neutrophils.25 The role of this genus in altering host immunity by modulating immunologic pathways may also be linked to cervical cancer risk and treatment outcomes. Studies also indicate that the genus Prevotella is native to many US immigrants. Vangay et al. found that the western-associated genus Bacteroides increasingly displaced the genus Prevotella in US immigrants; and paralled with time spent in the United States.26 Some of the geographical/racial variations in the gut microbiome have been attributed to differences in host genetics and innate/adaptive immunity, but in many other cases, location, culture and behavior may play a significant role.18 This and our findings support recent trends highlighting the racial and regional disparities in cervical cancer incidence and mortality in the United States,27 and emphasize the need for continued research to better characterize its role in minorities who experience high rates of cervical cancer 28

We found that diversity of the fecal microbiome in cervical cancer patients differed between young and older women. Bacterial α-diversity showed a trend to increase with age in women diagnosed with cervical cancer although this did not reach statistical significance. In contrast to cancer patients, α-diversity was inversely associated with age in control subjects (p < 0.01). Indeed, several studies have reported that older adults demonstrate an altered composition of the gut microbiota. Jeffery et al. found that advanced age is associated with variations in the gut microbiota composition characterized by a loss of diversity of specific taxa.29 Claesson et al. found that individuals over the age of sixty five were more likely to have a relative abundance of the genus Bacteroides and to display a loss of diversity associated taxa, including Prevotella.30 Our finding of an aged dependent decrease in alpha diversity among healthy controls is consistent with these previous results. The inverse relationship seen in our cervical cancer patients may signify a temporal association between chronic activation of the innate and adaptive immune systems and an altered bacterial composition in the gut.31

Gut microbial composition may play a role in cervical tumorigenesis.17 However, if the gut microbiome is protective against cervical tumorigenesis the exact mechanism is unclear. One theory is that the gut microbiome can influence tumorigenesis through an inflammatory response mediated by microorganism-associated molecular patterns and the activation of Toll-like receptors32. This pathway ultimately leads to the activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-17 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) which can stimulate tumorigenesis.32 With respect to different bacterial taxa, further investigation to characterize their role as either a passive bystander or antecedent in carcinogenesis is warranted. If there truly is an association, the direction of causation needs to be considered.

Strengths of this study include careful clinical staging, histopathology, prospective specimen collection prior to treatment among cancer patients, and analysis considering potential confounders, such as race, age and BMI. Additionally, the genus-level gut microbiome of healthy control individuals in our study was similar to those reported in prior studies. The Human Microbiome Project (HMP) Consortium previously reported that stool is dominated by Bacteroides and Alistipes,33 while Segata et al. highlighted the presence of Lachnospiraceae, Veillonellaceae, and Porphyromonadaceae in 10 sites located throughout the digestive tract in 200 healthy individuals.34

Although the present study has yielded intriguing findings, we were limited by the small sample size. Secondly, risk factors, such as persistent positive HPV in controls was not measured, but is likely to be <20%, the estimated prevalence among US women in this age range.35 Our case control design also prevents us from understanding causal associations or mechanisms linking differences in the gut microbiota and cervical cancer which is an area that deserves further study. Differences in diversity and composition may be due in part to different factors affecting the gut microbiome which were not controlled for in this study.36,38 Finally, fecal sample collection methods did vary between healthy controls and cervical cancer patients, but Vogtmann etal. previously investigated the reproducibility of five different fecal sampling techniques for microbiome analysis and concluded all methods were relatively reproducible, stable, and accurate.12 Additionally, although collection methods differed, sequenced data from all samples was processed using the same custom analytic packages and pipelines developed at the Alkek Center for Metagenomics and Microbiome Research at Baylor College of Medicine limiting artifactual variations in sample collection, DNA extraction or sequencing technology. These limitations are unlikely to fully explain the large differences in overall community composition we observed between cervical cancer patients and controls.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates hypothesis-generating age-related differences in fecal microbial profiles among cervical cancer patients as compared to cancer free controls. We identified previously unreported cervical cancer-associated gut bacteria which warrant further investigation. Differential associations within the gut microbiome of older versus younger women may reflect etiologic/clinical differences in these two groups. Additional studies are needed to validate these findings in larger cohorts and to determine the biological significance of these observed differences.

Highlights:

Among cervical cancer patients, bacterial diversity was higher in older women as compared to younger women.

Compared to controls, women with cervical cancer have distinct differences in their gut microbiota diversity.

Compared to controls, women with cervical cancer have distinct differences in their gut microbiota composition

Currently there is an important gap in studies investigating the gut microbiome and gynecologic cancers.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Duncan Family Institute for Cancer Prevention and Risk Assessment (CRD), the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA016672 and the National Institutes of Health T32 grant #5T32 CA101642-13 (TTS). This study was partially funded by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center HPV-related Cancers Moonshot (AK). The human subjects who participated in this study are gratefully acknowledged.

Research support: This research was supported in part by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Duncan Family Institute for Cancer Prevention and Risk Assessment (CRD), the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA016672 and the National Institutes of Health T32 grant #5T32 CA101642-13 (TTS). This study was partially funded by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center HPV-related Cancers Moonshot (AK).

Role of Funding Sources:

The funding sources were not involved in the development of the research hypothesis, study design, data analysis, or manuscript writing. Data access was limited to the authors of this manuscript.

The investigation described in this manuscript was presented in-part by Dr. Travis T. Sims during the 50th SGO Annual Meeting in Honolulu, Hawaii [March 16-19, 2019].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors report no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, related to the subject matter of the article submitted.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chase D, Goulder A, Zenhausern F, Monk B, Herbst-Kralovetz M. The vaginal and gastrointestinal microbiomes in gynecologic cancers: A review of applications in etiology, symptoms and treatment. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;138(1):190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.04.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gopalakrishnan V, Helmink BA, Spencer CN, Reuben A, Wargo JA. The Influence of the Gut Microbiome on Cancer, Immunity, and Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2018;33(4):570–580. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brestoff JR, Artis D. Commensal bacteria at the interface of host metabolism and the immune system. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(7):676–684. doi: 10.1038/ni.2640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McQuade JL, Daniel CR, Helmink BA, Wargo JA. Modulating the microbiome to improve therapeutic response in cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(2):e77–e91. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30952-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conesa-Zamora P Immune responses against virus and tumor in cervical carcinogenesis: Treatment strategies for avoiding the HPV-induced immune escape. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;131(2):480–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nees M, Geoghegan JM, Hyman T, Frank S, Miller L, Woodworth CD. Papillomavirus Type 16 Oncogenes Downregulate Expression of Interferon-Responsive Genes and Upregulate Proliferation-Associated and NF- B-Responsive Genes in Cervical Keratinocytes. J Virol. 2001;75(9):4283–4296. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.9.4283-4296.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heller C, Weisser T, Mueller-Schickert A, et al. Identification of Key Amino Acid Residues That Determine the Ability of High Risk HPV16-E7 to Dysregulate Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I Expression. J Biol Chem. 2011. ;286(13): 10983–10997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.199190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sivan A, Corrales L, Hubert N, et al. Commensal <em>Bifidobacterium</em> promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti–PD-L1 efficacy. Science (80-). 2015;350(6264): 1084 LP–1089. http://science.sciencemag.org/content/350/6264/1084.abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gopalakrishnan V, Spencer CN, Nezi L, et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science (80-). 2018;359(6371):97 LP–103. http://science.sciencemag.org/content/359/6371/97.abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flores R, Shi J, Yu G, et al. Collection media and delayed freezing effects on microbial composition of human stool. Microbiome. 2015:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s40168-015-0092-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogtmann E, Chen J, Amir A, et al. Comparison of Collection Methods for Fecal Samples in Microbiome Studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2017; 185(2): 115–123. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sinha R, Chen J, Amir A, et al. Collecting Fecal Samples for Microbiome Analyses in Epidemiology Studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(2):407–416. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bombardelli C, Ayuso JH, Pelayo RG. A framework for human microbiome research. Nature. 2012;486(7402):215–221. doi: 10.1038/nature11209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edgar RC. UPARSE: Highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods. 2013;10(10):996–998. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011;12(6). doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Z, Wang Q, Zhao J, et al. Altered diversity and composition of the gut microbiome in patients with cervical cancer. AMB Express. 2019;9(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s13568-019-0763-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta VK, Paul S, Dutta C. Geography, Ethnicity or Subsistence-Specific Variations in Human Microbiome Composition and Diversity. Front Microbiol. 2017;8. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahn J, Sinha R, Pei Z, et al. Human Gut Microbiome and Risk for Colorectal Cancer. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(24):1907–1911. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coker OO, Dai Z, Nie Y, et al. Mucosal microbiome dysbiosis in gastric carcinogenesis. Gut. 2018;67(6):1024–1032. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ritu W, enqi W, Zheng S, Wang J, Ling Y, Wang Y. Evaluation of the associations between cervical microbiota and HPV infection, clearance, and persistence in cytologically normal women. Cancer Prev Res. 2018:canprevres.0233.2018. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-18-0233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anahtar MN, Byrne EH, Doherty KE, et al. Cervicovaginal Bacteria Are a Major Modulator of Host Inflammatory Responses in the Female Genital Tract. Immunity. 2015;42(5):965–976. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scher JU, Sczesnak A, Longman RS, et al. Expansion of intestinal Prevotella copri correlates with enhanced susceptibility to arthritis. Elife. 2013;2. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berezow AB, Darveau RP. Microbial shift and periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2011;55(1):36–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2010.00350.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larsen JM. The immune response to Prevotella bacteria in chronic inflammatory disease. Immunology. 2017;151(4):363–374. doi: 10.1111/imm.12760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vangay P, Johnson AJ, Ward TL, et al. US Immigration Westernizes the Human Gut Microbiome. Cell. 2018;175(4):962–972. e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoo W, Kim S, Huh WK, et al. Recent trends in racial and regional disparities in cervical cancer incidence and mortality in United States. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson B, Carosso EA, Jhingan E, et al. Results of a randomized controlled trial to increase cervical cancer screening among rural Latinas. Cancer. 2017;123(4):666–674. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeffery IB, Lynch DB, O’Toole PW. Composition and temporal stability of the gut microbiota in older persons. ISME J. 2016;10(1):170–182. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Claesson MJ, Cusack S, O’Sullivan O, et al. Composition, variability, and temporal stability of the intestinal microbiota of the elderly. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108(Supplement_1):4586–4591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000097107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buford TW. (Dis)Trust your gut: the gut microbiome in age-related inflammation, health, and disease. Microbiome. 2017;5(1):80. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0296-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cerf-Bensussan N, Gaboriau-Routhiau V. The immune system and the gut microbiota: friends or foes? Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(10):735–744. doi: 10.1038/nri2850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huttenhower C, Gevers D, Knight R, et al. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012;486(7402):207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature11234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Segata N, Haake S, Mannon P, et al. Composition of the adult digestive tract bacterial microbiome based on seven mouth surfaces, tonsils, throat and stool samples. Genome Biol. 2012;13(6):R42. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dickson EL, Vogel RI, Luo X, Downs LS. Recent trends in type-specific HPV infection rates in the United States. Epidemiol Infect. 2015; 143(5): 1042–1047. doi: 10.1017/S0950268814001538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haro C, Rangel-Zúñiga OA, Alcalá-Díaz JF, et al. Intestinal Microbiota Is Influenced by Gender and Body Mass Index. Sanz Y, ed. PLoS One. 2016; 11(5):e0154090. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qin Y, Roberts JD, Grimm SA, et al. An obesity-associated gut microbiome reprograms the intestinal epigenome and leads to altered colonic gene expression. Genome Biol. 2018;19(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1389-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bouter KE, van Raalte DH, Groen AK, Nieuwdorp M. Role of the Gut Microbiome in the Pathogenesis of Obesity and Obesity-Related Metabolic Dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 2017; 152(7): 1671–1678. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.12.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]