Abstract

A 31-year-old HIV-seropositive woman from Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, presented with a 3-month history of widespread umbilicated and ulcerated skin papules, plaques, and nodules. The skin lesions were biopsied and sent for histology and fungal culture; the cultured isolate was referred for molecular identification. Histology, fungal culture, and molecular testing confirmed that the dimorphic fungal pathogen Emergomyces africanus had caused a disseminated mycosis.

Keywords: Emergomyces africanus, Human immunodeficiency virus, AIDS-related opportunistic infections, Mycoses

Introduction

Systemic fungal infections are common among persons living with advanced HIV disease in South Africa [1]. An underreported and emerging opportunistic infection, which can be fatal in HIV-seropositive patients, is caused by a thermally dimorphic fungal pathogen known as Emergomyces africanus [2]. The detection of Es. africanus is challenging in South Africa due to our limited knowledge of the epidemiology of the disease and the fact that molecular testing is not widely available. Cryptococcosis and histoplasmosis are well-documented systemic fungal infections in HIV-seropositive patients and can masquerade as other infections, including tuberculosis [2]. Es. africanus is recognized as an endemic mycosis in southern Africa and has been reported from six of the nine provinces in South Africa and in Lesotho [2]. Many cases have been misdiagnosed as sporotrichosis or histoplasmosis. We report the first documented case of a patient diagnosed with Es. africanus in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.

Case Report

A 31-year-old woman from an urban area was seen at a dermatology department at a tertiary care hospital in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal. She presented with a 3-month history of umbilicated or ulcerated papules, plaques, and nodules (Fig. 1, 2). The lesions had initially started on her face and then appeared on her trunk. She was HIV seropositive and her CD4+ T-lymphocyte count was 80 cells/µL with an undetectable HIV viral load. The patient had been commenced on antiretroviral therapy (a fixed-dose combination of tenofovir, emtricitabine, and efavirenz) 3 months prior to presentation to the hospital. Her skin lesions were biopsied and sent for histology and fungal culture. The initial clinical diagnoses considered were histoplasmosis and cryptococcosis; hence, the patient was commenced on oral fluconazole at a dose of 400 mg daily. The patient was systemically well, and chest radiography showed no abnormal findings. Blood tests revealed a microcytic normochromic anemia; other blood parameters were within normal ranges.

Fig. 1.

Patient with necrotic crusted skin papules and plaques.

Fig. 2.

Minimal resolution of the lesions 2 months after antifungal therapy.

Results

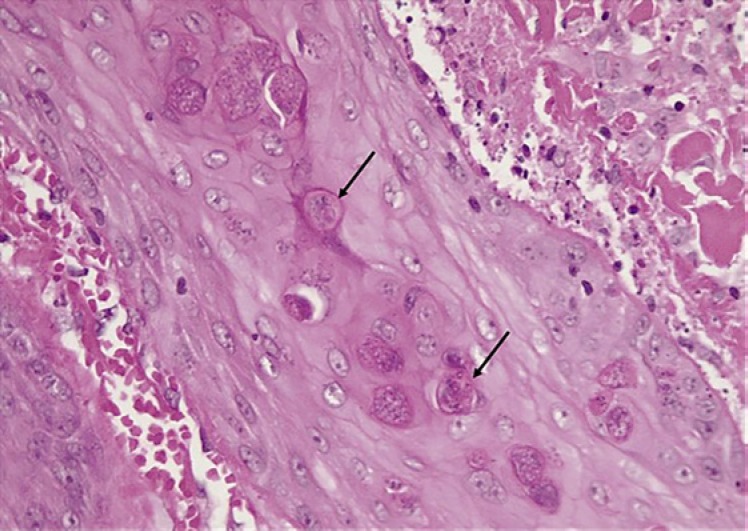

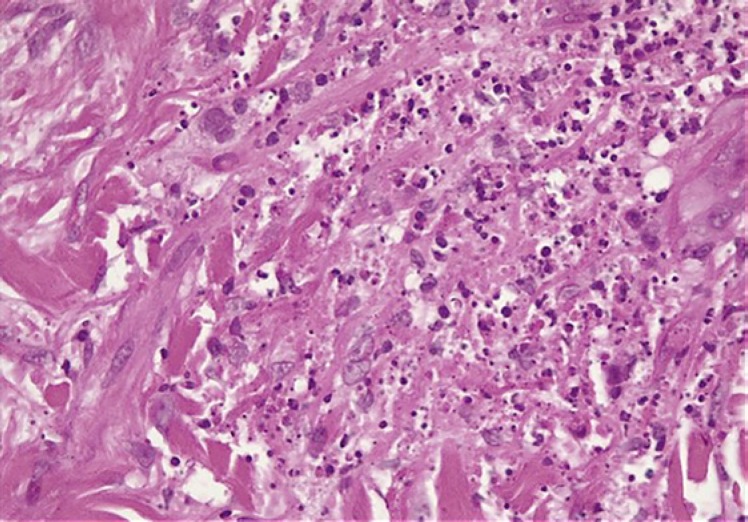

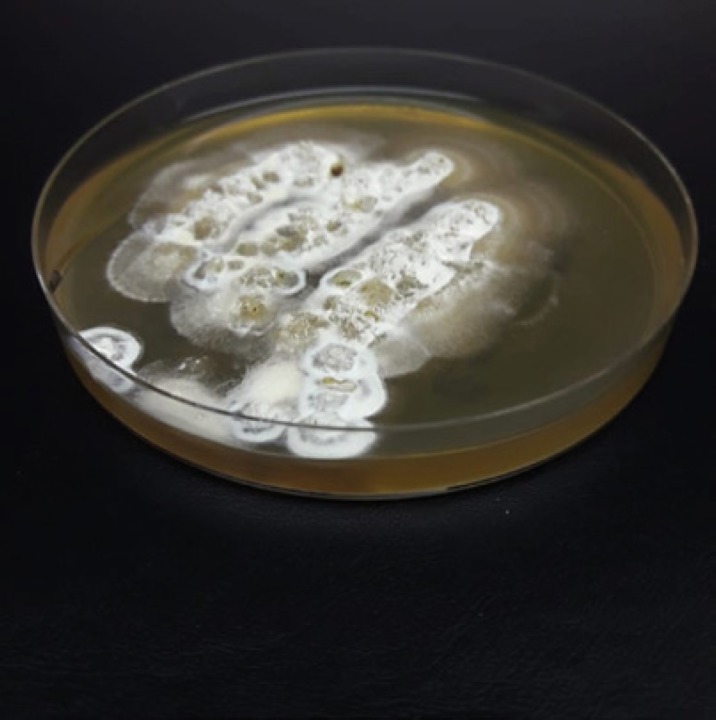

Histology of the skin biopsy specimen (Fig. 4, 5, 6) revealed a histiocytic infiltrate in the dermis containing intracytoplasmic budding yeasts. Nonnecrotizing granulomas, multinucleated giant cells with a lymphocyte-rich background, and plasma cells were observed. Stains for acid-fast bacilli were negative. A periodic acid-Schiff stain demonstrated intracytoplasmic yeasts. Tissue samples were cultured on routine mycology media. After an average of 10–14 days, white colonies appeared, which turned beige and wrinkled over time. Cultures were sent to the National Institute for Communicable Diseases for molecular identification; sequence-based testing confirmed the identification as Es. africanus (Fig. 7, 8). At a 6-month follow-up visit, the patient's skin lesions had completely resolved (Fig. 3) following fluconazole monotherapy.

Fig. 4.

Aggregates of yeast cells undergoing transepidermal elimination.

Fig. 5.

Dermal neutrophilic and histiocytic inflammatory response with abundant karyorrhectic debris.

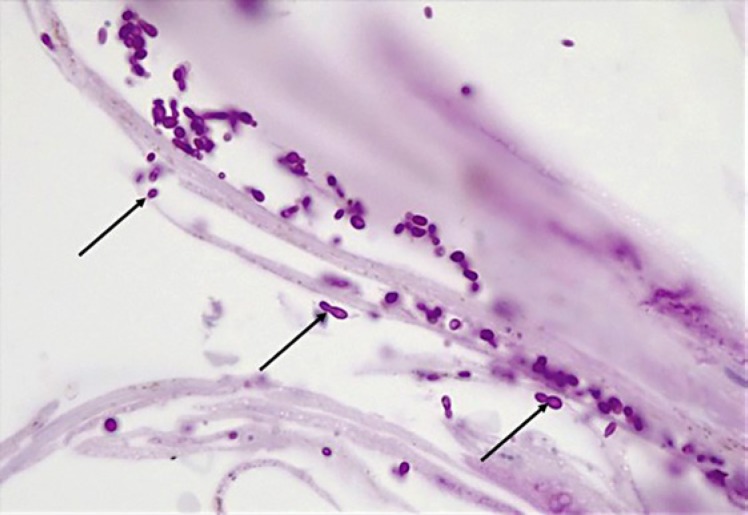

Fig. 6.

Yeast cells undergoing transepidermal elimination. Thin-walled, round-to-ovoid yeast cells measuring 3–6 μm in diameter. Narrow-neck budding was noted.

Fig. 7.

Mycelial-phase culture of Emergomyces africanus on Sabouraud agar.

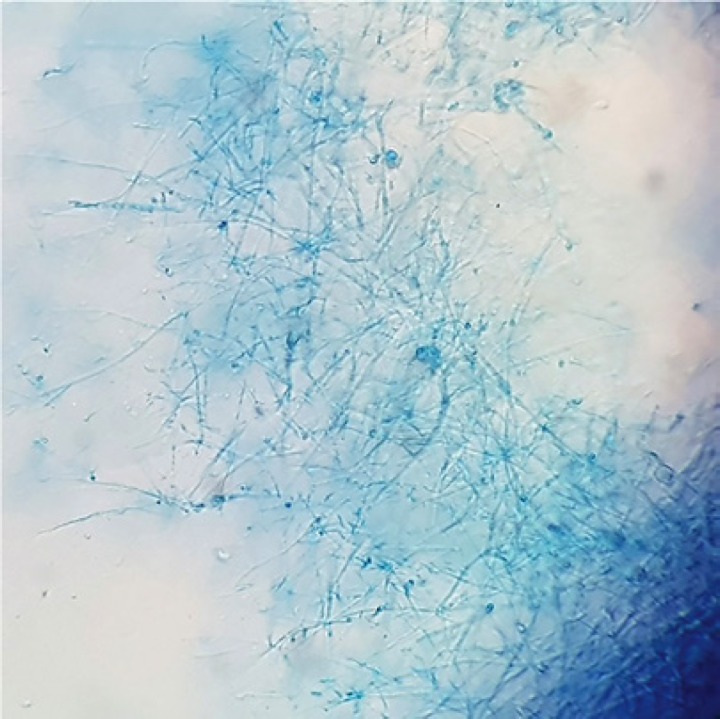

Fig. 8.

Microscopic appearance of Emergomyces africanus.

Fig. 3.

Complete resolution of the skin lesions after 6 months of therapy with fluconazole.

Discussion

Emergomyces spp. (formerly Emmonsia) are opportunistic fungi which cause disease usually among HIV-seropositive patients. Es. africanus has recently been discovered within this genus and has only been reported in southern Africa [2]. Emergomyces belongs to the larger family of thermally dimorphic fungi Ajellomycetaceae (Onygenales) [3]. The genus Emergomyces contains Es. africanus, Es. europaeus, Es. canadensis, and Es. orientalis, as well as the type species Es. pasteurianus [1]. These species differ in yeast size and geographic distribution [3]. Soil is presumed to the reservoir for Es. africanus [4].

Clinically, patients present with polymorphic skin lesions such as umbilicated papules, nodules, ulcers, verrucous lesions, crusting, and erythema. Systemic features include pulmonary, liver, and splenic involvement. In South Africa, most of these cases have been misdiagnosed as histoplasmosis or sporotrichosis. Es. africanus has been found in soil, and it is presumed that disease follows inhalation of airborne propagules. Histology is the fastest way to diagnose systemic fungal infections, but this can be difficult as Es. africanus closely resembles Histoplasma capsulatum, with small (2- to 5-µm) intracellular and extracellular oval-to-round budding yeasts [2]. Histology can detect yeasts, but one cannot differentiate between the different genera. Thus, if specimens are not submitted for mycological culture, it is not possible to differentiate between the two mycoses. Culture to isolate Es. africanus is performed using Sabouraud agar, and growth is seen within 7–30 days at an incubation temperature of 25–30°C. Morphologically, mold-phase colonies appear beige and are slow growing at room temperature. The conidiophores are short and unbranched, arising at right angles from thin-walled hyaline hyphae, slightly swollen at the top, sometimes with short secondary conidiophores bearing “florets” of conidia [2]. Molecular identification of cultured isolates has been the gold standard test for Es. africanus detection, but it is not readily available in KwaZulu-Natal.

The treatment of choice for emergomycosis is amphotericin B intravenously at 0.7–1 mg/kg daily for 14 days, followed by itraconazole for at least 12 months [5]. Our patient was treated with fluconazole 400 mg daily, surprisingly with complete resolution of the skin lesions (Fig. 3). Fluconazole has fewer drug-drug interactions with antiretroviral therapy and is cheaper and more readily available in South Africa; however, this agent has a less potent in vitro activity [2].

We reported the case of a systemic fungal infection caused by Es. africanus which was misdiagnosed as histoplasmosis clinically and on histopathology in an HIV-seropositive patient who responded to antifungal therapy with fluconazole. Emergomycosis needs to be considered among patients who present with cutaneous lesions similar to those with histoplasmosis. Pathologists should be alerted when skin biopsies are sent for evaluation, and blood and skin samples should be sent for mycological culture. Our patient responded to fluconazole despite this agent's limited activity in vitro.

Statement of Ethics

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for use of the clinical images.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author Contributions

A. Moodley: draft of a first version of the manuscript; A.V. Chateau, A. Mosam, Y. Mahabeer, and N.P. Govender: critical review of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Julian Deonarian from Lancet Laboratories for the histopathology images, as well as N.P. Govender and Mrs. Diane Naidu for the culture images.

References

- 1.Dukik K, Al-Hatmi AM, Curfs-Breuker I, Faro D, de Hoog S, Meis JF. Antifungal Susceptibility of Emerging Dimorphic Pathogens in the Family Ajellomycetaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 Dec;62((1)):e01886–e01917. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01886-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz IS, McLoud JD, Berman D, Botha A, Lerm B, Colebunders R, et al. Molecular detection of airborne Emergomyces africanus, a thermally dimorphic fungal pathogen, in Cape Town, South Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018 Jan;12((1)):e0006174. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang Y, Dukik K, Muñoz JF, Sigler L, Schwartz IS, Govender NP, et al. Phylogeny, ecology and taxonomy of systemic pathogens and their relatives in Ajellomycetaceae (Onygenales): Blastomyces, Emergomyces, Emmonsia, Emmonsiellopsis. Fungal Divers. 2018;90((1)):245–91. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz IS, Lerm B, Hoving JC, Kenyon C, Horsnell WG, Basson WJ, et al. Emergomyces africanus in Soil, South Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018 Feb;24((2)):377–80. doi: 10.3201/eid2402.171351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz IS, Maphanga TG, Govender NP. Emergomyces: a New Genus of Dimorphic Fungal Pathogens Causing Disseminated Disease among Immunocompromised Persons Globally. Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2018;12((1)):44–50. [Google Scholar]