Abstract

Technological advances in inertial sensors allow for monitoring of daily-life gait characteristics as a proxy for fall risk. The quality of daily-life gait could serve as a valuable outcome for intervention trials, but the uptake of these measures relies on their power to detect relevant changes in fall risk. We collected daily-life gait characteristics in 163 older people (aged 77.5 ± 7.5, 107♀) over two measurement weeks that were two weeks apart. We present variance estimates of daily-life gait characteristics that are sensitive to fall risk and estimate the number of participants required to obtain sufficient statistical power for repeated comparisons. The provided data allows for power analyses for studies using daily-life gait quality as outcome. Our results show that the number of participants required (i.e., 8 to 343 depending on the anticipated effect size and between-measurements correlation) is similar to that generally used in fall prevention trials. We propose that the quality of daily-life gait is a promising outcome for intervention studies that focus on improving balance and mobility and reducing falls.

Keywords: intervention studies, accelerometry, activity monitoring, aged, accidental falls

1. Introduction

Effective interventions to prevent falls in older people address balance and mobility problems through exercise interventions, medication reviews, and environmental modifications [1]. Despite a focus on balance and mobility, the default primary outcomes of such intervention trials are the rate of falls or the proportion of fallers. These outcomes require 6 to 12 months of intensive follow-up and are susceptible to definitional issues and recall biases [2,3]. Moreover, the incidence of falls does not directly equate fall risk, since exposure to random environmental events plays an important role [4,5]. Clinical tests of balance and mobility can be assessed relatively quickly and can be used as proxies for fall risk in intervention trials. However, their utility has been hampered by the requirement of in-person assessments under standardized conditions, which may not reflect an individual’s performance in daily life [6,7].

Technological advances in wearable sensors allow for the assessment of the quantity and quality of daily-life activities. Several studies have shown that characteristics of daily-life gait, assessed by a single trunk-worn sensor, are associated with fall risk among older people [8,9,10]. These gait characteristics, such as gait stability and variability, provide complementary information to commonly-used clinical tests in the prediction of falls [11]. Experimental studies further provide evidence that gait characteristics, during standardized assessments, are sensitive to relatively small balance impairments and are affected by disturbances of the sensory systems, medication, muscle fatigue, and training [12,13,14,15,16]. Effect sizes for these manipulations approximate a Cohen’s d of 3.0–5.0 for desensitization of the feet and electrical vestibular stimulation in healthy young [13,14], 0.3 for rivastigmine medication in people with Parkinson’s disease [16], 0.5–0.6 for muscle fatigue in older people [12] and 0.3–0.8 for a dance intervention in older people [15]. The difference in daily-life gait quality between older people who fall, and those who do not fall in the next 6 months, is in the order of a Cohen’s d of 0.3 (range 0.03 to 0.5) [11]. The assessment of daily-life gait characteristics may hence be valuable for intervention trials.

In order to determine whether daily-life gait characteristics are sensitive to change, such as intervention effects, large-scale clinical trials are required. Sample size calculations are essential in the design of such trials. However, the estimation of the variance components that are needed for these calculations, requires large samples of repeated measurements, which are generally not available early in a study. We analyzed trunk accelerometry data collected for [10] to provide this information to support the design of intervention trials. We estimated the variance components and performed a sample size calculation to reveal how many participants would be required in order to detect the statistically significant intervention effects on daily-life gait quality characteristics obtained from inertial sensor data in older people.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This study was part of a larger project investigating fall risk in older people (FARAO [8,10]). The participants were older people, who were recruited from Amsterdam (the Netherlands) and its surroundings via advertisements through general practitioners, hospitals, and residential care facilities. Inclusion criteria were: being between 65 and 99 years of age, having no major cognitive impairments (assessed as a Mini Mental State Examination score exceeding 18 out of 30 points [17]), and being able to walk at least 20 m with, or without, the help of a walking aid. The medical ethics committee of the VU medical centre approved the protocol (ID 2010/290) and all participants signed informed consent.

2.2. Measurements

The data of 163 older people (mean age 77.5, SD 7.5 years; 107♀) were analyzed for the current paper. The participants wore a trunk accelerometer (DynaPort MoveMonitor, McRoberts BV, The Netherlands) for two separate one-week periods, with a median between-assessment interval of 14 days (interquartile range 28 days, maximum 65 days). They were instructed to wear the accelerometer at all times, except during water activities, such as showering or swimming as this would damage the device. No intervention took place during the between-assessment interval. The tri-axial trunk accelerometer was placed on the back of the trunk at the level of L5 using a supplied elastic belt, and registered trunk accelerations in vertical (VT), mediolateral (ML), and anteroposterior (AP) directions with a sample frequency of 100 samples/s and range of +/-6 g.

2.3. Data Analysis

The episodes of locomotion were identified using the manufacturers algorithm. This algorithm was validated against video [18] and the detection of locomotion episodes was shown to be reliable over weeks [19]. The raw data of locomotion periods were extracted and realigned with anatomical axes, based on the accelerometer’s orientation with respect to the gravity and optimization of left-right symmetry [8,10]. Subsequently, gait quality was estimated as median values over each week of 40 characteristics, reflecting walking speed, stride frequency, regularity, intensity, symmetry, smoothness, stability, and complexity of gait [8,10]. We report on 18 gait characteristics, that were significantly associated with prospective falls [10] in our tables, and provide data for all gait characteristics in Appendix A. We calculated a single gait quality composite score, based on a weighted sum of autocorrelation at stride frequency, power at step frequency, root mean square of the accelerations and index of harmonicity, which was previously found to be an important predictor for falls [10]. The custom Matlab-code to calculate this gait quality composite score can be found here: github.com/KimvanS/EstimateGaitQualityComposite.

2.4. Statistics

Data was inspected for normality using Q-Q plots and KS tests. Most variables followed a normal distribution, except for the amplitude of the dominant frequency. However, since its difference scores did follow a normal distribution, parametric statistics are reported for all variables. We tested for structural differences between both measurement weeks, using repeated measures ANOVAs, and Pearson correlations. The repeated measures ANOVAs were subsequently used to extract the overall mean and variance components, reflecting between-subjects (i.e., among participants), within-subject (i.e., between measurement weeks), and error variability (i.e., individual differences due to sampling error). Sample size calculations, for repeated measures, were performed to determine the number of participants required to detect changes in these gait quality characteristics over measurements. The number of participants (n) was estimated following [20] as:

| (1) |

where is the total variance, the between-subject variance, r the within-subject correlation, tdf,p the pth-percentile of a t-distribution with df degrees of freedom, 1- β the desired level of statistical power, α the desired level of statistical significance, and Δ the effect size. Statistical power was set to 0.8 and statistical significance was set to 0.05. The numbers of participants required to detect an effect size Δ of Cohen’s d 0.3 (small), 0.5 (medium), and 0.8 (large), were estimated for all gait quality characteristics.

3. Results

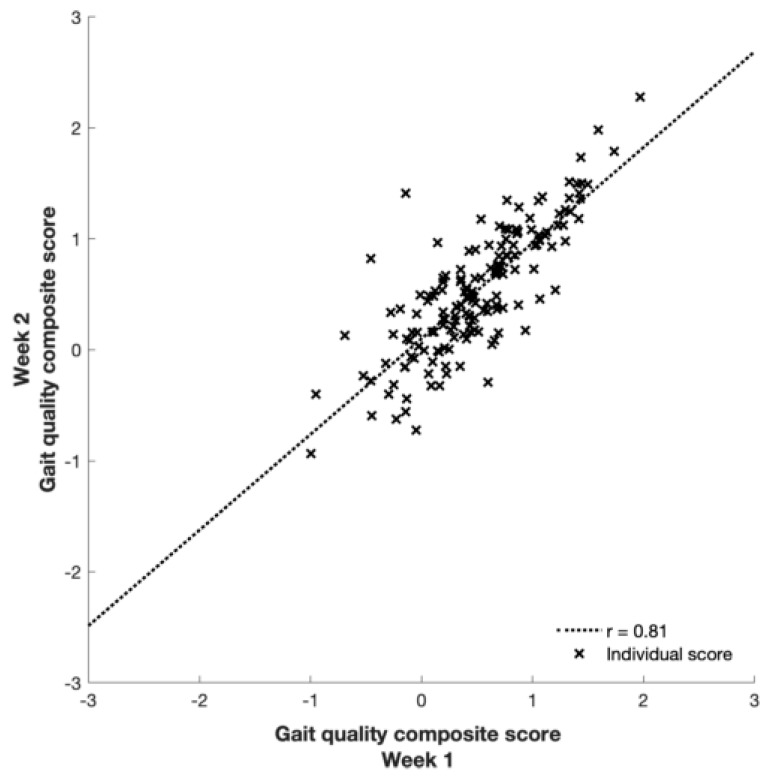

None of the gait quality characteristics differed significantly between the two measurement weeks (all p ≥ 0.11) and all were strongly correlated (r = 0.80 to 0.96; Figure 1 and Table 1). Between-subject variance was the largest variance component for all characteristics, and 3 to 26 times higher than within-subject variance. Moreover, between-subject variance components were highest for characteristics that were orientation invariant (e.g. walking speed, step length, and time), and generally higher for ML compared to AP, with VT in between (Table 1 and Table A1 for all 40 characteristics).

Figure 1.

Agreement between the gait quality composite scores of the first and second week.

Table 1.

Agreement between weeks and estimated variance components for gait characteristics associated with prospective falls in [10].

| p | r | Mean | s2BS | s2WS | s2E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gait quality composite score | 0.64 | 0.81 | 0.51369 | 0.54700 | 0.08068 | 0.05759 |

| Walking speed | 0.39 | 0.93 | 0.45073 | 0.01030 | 0.00027 | 0.00036 |

| Stride frequency | 0.51 | 0.95 | 0.82482 | 0.01119 | 0.00013 | 0.00030 |

| Standard deviation VT | 0.77 | 0.92 | 1.32658 | 0.17858 | 0.00061 | 0.00733 |

| Standard deviation ML | 0.18 | 0.94 | 1.16407 | 0.09332 | 0.00560 | 0.00305 |

| Range AP | 0.40 | 0.91 | 7.33318 | 7.13497 | 0.23150 | 0.32894 |

| Stride autocorrelation VT | 0.54 | 0.82 | 0.37464 | 0.01051 | 0.00040 | 0.00103 |

| Stride autocorrelation AP | 0.63 | 0.83 | 0.32881 | 0.00945 | 0.00021 | 0.00088 |

| Amplitude of dominant frequency VT | 0.68 | 0.93 | 0.49412 | 0.04264 | 0.00026 | 0.00155 |

| Amplitude of dominant frequency ML | 1.00 | 0.91 | 0.47481 | 0.05827 | 9.26 × 10−9 | 0.00263 |

| Amplitude of dominant frequency AP | 0.11 | 0.85 | 0.51044 | 0.02357 | 0.00501 | 0.00198 |

| Width of dominant frequency AP | 0.14 | 0.80 | 0.75841 | 0.00611 | 0.00167 | 0.00075 |

| Index of harmonicity VT | 0.19 | 0.96 | 0.62043 | 0.04940 | 0.00156 | 0.00092 |

| Index of harmonicity ML | 0.68 | 0.92 | 0.64420 | 0.06977 | 0.00048 | 0.00276 |

| Harmonic ratio VT | 0.47 | 0.90 | 1.53576 | 0.07348 | 0.00211 | 0.00406 |

| Local divergence rate/stride VT | 0.75 | 0.87 | 2.11436 | 0.13693 | 0.00097 | 0.00919 |

| Local divergence rate/stride AP | 0.58 | 0.86 | 2.19507 | 0.09652 | 0.00217 | 0.00707 |

| Sample entropy ML | 0.74 | 0.91 | 0.31207 | 0.00394 | 2.07 × 10−5 | 0.00018 |

Note: We tested for structural differences between both measurement weeks using a repeated measures ANOVA (p-value) and Pearson correlations (r). We subsequently report mean values (mean) and variance components between-subjects (s2BS), within-subjects (s2WS) and due to sampling error (s2E).

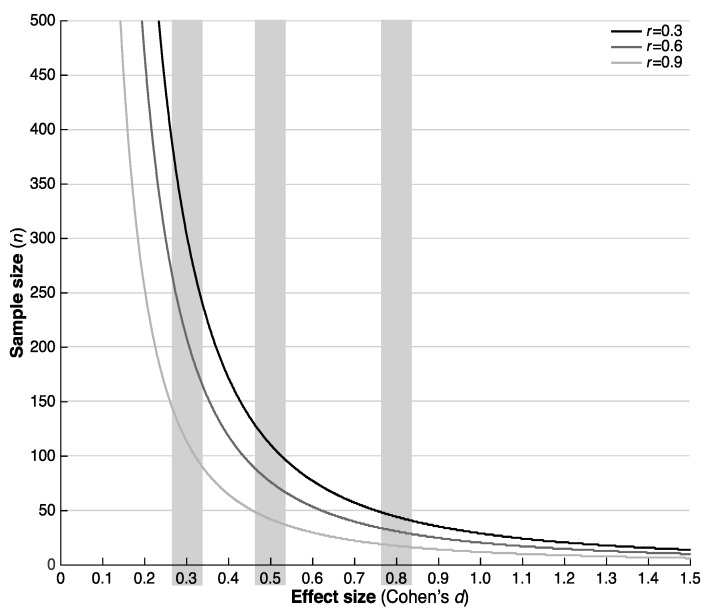

The number of participants required to detect intervention effects with sufficient statistical power ranged from 8 (large effect, r = 0.9) to 343 (small effect, r = 0.3) (Figure 2 and Table 2; see Table A2 for all characteristics).

Figure 2.

Number of participants required to detect an effect of Cohen’s d on the gait quality composite score.

Table 2.

Number of participants required to detect an effect of Cohen’s d on gait characteristics associated with prospective falls in [10].

| Small Effect | Medium Effect | Large Effect | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohen’s d = 0.3 | Cohen’s d = 0.5 | Cohen’s d = 0.8 | |||||||

| r = 0.3 | r = 0.6 | r = 0.9 | r = 0.3 | r = 0.6 | r = 0.9 | r = 0.3 | r = 0.6 | r = 0.9 | |

| Gait quality composite score | 303 | 208 | 114 | 110 | 76 | 42 | 44 | 31 | 18 |

| Walking speed | 259 | 158 | 56 | 95 | 58 | 22 | 38 | 24 | 10 |

| Stride frequency | 254 | 151 | 49 | 93 | 56 | 19 | 37 | 23 | 9 |

| Stride length | 251 | 148 | 44 | 92 | 54 | 17 | 37 | 22 | 8 |

| Standard deviation VT | 252 | 151 | 51 | 92 | 56 | 19 | 37 | 23 | 9 |

| Standard deviation AP | 266 | 163 | 61 | 97 | 60 | 23 | 39 | 25 | 10 |

| Range AP | 262 | 162 | 62 | 96 | 60 | 23 | 39 | 24 | 10 |

| Stride autocorrelation VT | 268 | 173 | 77 | 98 | 63 | 29 | 39 | 26 | 13 |

| Stride autocorrelation AP | 263 | 167 | 71 | 96 | 61 | 27 | 39 | 25 | 12 |

| Amplitude of dominant frequency VT | 253 | 151 | 50 | 92 | 56 | 19 | 37 | 23 | 9 |

| Amplitude of dominant frequency ML | 251 | 151 | 51 | 92 | 56 | 19 | 37 | 23 | 9 |

| Amplitude of dominant frequency AP | 323 | 227 | 130 | 118 | 83 | 48 | 47 | 34 | 20 |

| Width of dominant frequency AP | 343 | 250 | 156 | 125 | 91 | 57 | 50 | 37 | 24 |

| Index of harmonicity VT | 260 | 157 | 54 | 95 | 58 | 21 | 38 | 24 | 9 |

| Index of harmonicity ML | 253 | 152 | 51 | 92 | 56 | 20 | 37 | 23 | 9 |

| Harmonic ratio VT | 262 | 162 | 63 | 96 | 60 | 24 | 39 | 25 | 11 |

| Local divergence rate/stride VT | 256 | 157 | 59 | 93 | 58 | 23 | 38 | 24 | 10 |

| Local divergence rate/stride AP | 261 | 164 | 66 | 95 | 60 | 25 | 38 | 25 | 11 |

| Sample entropy ML | 253 | 153 | 53 | 92 | 56 | 20 | 37 | 23 | 9 |

4. Discussion

The purpose of this paper was to report the variance components required for sample size calculations in studies focusing on characteristics of daily-life gait quality as outcome measures. This paper also aimed to determine the number of participants required to detect intervention effects in a repeated measure design with sufficient statistical power (here set at 80%). Our sample size calculations indicate that the number of participants required for a test-retest intervention design will range from 8 to 343, depending on the anticipated between-measurement correlation and effect size. These numbers seem reasonable, compared to the 200 to 500 (range 10 to 9940, median 230 [1]) participants that are generally included in fall prevention intervention studies. This approach has the additional advantage that outcomes are available directly after the intervention, and that physical activity or exposure, can be readily assessed using similar methods. Future studies are required to determine whether changes due to interventions focusing on improving balance and mobility, and reducing falls can indeed be detected with daily-life gait quality characteristics.

The high correlation between measurements, combined with the relatively small within-subject variance, suggests that participant’s daily-life gait characteristics are relatively stable, at least over weeks without an intervention. Possible changes in orientation, due to reattaching the sensor after water activities, may have increased within-subject variance, a source of variance that can be remediated by fixing a waterproof sensor directly onto the body. Changes in orientation, over days, may have contributed to the higher number of participants required for orientation-dependent characteristics, when compared to orientation-invariant characteristics. The relatively small within-subject variance is encouraging for clinical use, as it holds promise for evaluation on the individual level.

The magnitude of the between-subject variance components for gait stability and variability characteristics in this study, was larger than those reported by Toebes and colleagues for treadmill gait [20]. This could be a result of differences in experimental setup and algorithms [21] to assess these characteristics. However, it is also possible that assessments in daily life result in better differentiation between individuals. A direct comparison of the sensitivity to change of the laboratory-based and daily-life assessment of gait quality characteristics for fall risk seems warranted.

Despite the benefits of using daily-life gait characteristics as outcomes in fall prevention trials, there are barriers to their broad uptake. Although, inertial sensors are relatively cheap compared to other motion registration equipment, they generally cost ~$500–5000. Moreover, these sensors require charging and setting-up, can be logistically inconvenient and need specialist code to extract meaningful outcomes. Finally, non-wearing might render collected data useless. Nevertheless, we feel that the advantages outweigh the disadvantages and hope that this paper provides the tools and data necessary to facilitate their implementation.

This study has some limitations. The locomotion detection algorithm may have introduced some error. However, its validity and reliability are high [18,19]. Moreover, we limited this study to median values of the distribution of the daily-life gait quality characteristics while more extreme percentiles, that better reflect participants’ capacity [6,8], may show different variances. The estimated variance components will also depend on sensor characteristics, the methods of fixation and fixation location, and thus might not generalize to other settings. The strength of the correlation between measurements, used in the sample size calculations, was estimated and actual values may be lower, with longer follow-up times and individuals responding differently to interventions. The time between measurements was relatively short in this study, which warrants the assumption of little changes within individuals over time; longer follow-up periods in trials may therefore present larger within-subject variance.

5. Conclusions

We provided variance estimates to determine the number of participants required for intervention trials using daily-life gait characteristics as outcomes. The subsequent sample size estimations indicate that a substantial number of participants is required to detect the effects of interventions. However, this number is lower than that commonly used in trials with incidence of falls as the outcome. Therefore, characteristics of daily-life gait quality seems to be a promising outcome for intervention studies, focusing on balance, mobility, and falls.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants and research assistants for their help with the study. The authors are very grateful to Alan K. Chiang of Neuroscience Research Australia for reviewing the provided GitHub code.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Agreement between weeks and estimated variance components for all gait characteristics.

| p | r | Mean | s2BS | s2WS | s2E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gait quality composite score | 0.64 | 0.81 | 0.51369 | 0.54700 | 0.08068 | 0.05759 |

| Stride autocorrelation VT | 0.54 | 0.82 | 0.37464 | 0.01051 | 0.00040 | 0.00103 |

| Stride autocorrelation ML | 0.65 | 0.94 | 0.34724 | 0.02069 | 0.00013 | 0.00060 |

| Stride autocorrelation AP | 0.63 | 0.83 | 0.32881 | 0.00945 | 0.00021 | 0.00088 |

| Walking speed | 0.39 | 0.93 | 0.45073 | 0.01030 | 0.00027 | 0.00036 |

| Step length | 0.41 | 0.97 | 0.63683 | 0.02457 | 0.00022 | 0.00032 |

| Stride time variability | 0.74 | 0.85 | 9.36259 | 13.19347 | 0.11324 | 1.05325 |

| Stride speed variability | 0.87 | 0.95 | 0.04695 | 0.00030 | 2.20 × 10−7 | 7.90 × 10−6 |

| Stride length variability | 0.65 | 0.93 | 0.04456 | 0.00029 | 2.07 × 10−6 | 1.01 × 10−5 |

| Standard deviation VT | 0.77 | 0.92 | 1.32658 | 0.17858 | 0.00061 | 0.00733 |

| Standard deviation ML | 0.18 | 0.94 | 1.16407 | 0.09332 | 0.00560 | 0.00305 |

| Standard deviation AP | 0.13 | 0.96 | 1.08260 | 0.09554 | 0.00479 | 0.00203 |

| Stride frequency | 0.51 | 0.95 | 0.82482 | 0.01119 | 0.00013 | 0.00030 |

| Percentage of power <0.7 hz VT | 0.65 | 0.88 | 0.23888 | 0.04349 | 0.00059 | 0.00284 |

| Percentage of power <0.7 hz ML | 0.76 | 0.90 | 11.96214 | 96.31279 | 0.45914 | 4.98382 |

| Percentage of power <0.7 hz AP | 0.85 | 0.77 | 11.29116 | 29.95935 | 0.13423 | 3.85606 |

| Index of harmonicity VT | 0.19 | 0.96 | 0.62043 | 0.04940 | 0.00156 | 0.00092 |

| Index of harmonicity ML | 0.68 | 0.92 | 0.64420 | 0.06977 | 0.00048 | 0.00276 |

| Index of harmonicity AP | 0.45 | 0.90 | 0.77248 | 0.00890 | 0.00026 | 0.00046 |

| Harmonic ratio VT | 0.47 | 0.90 | 1.53576 | 0.07348 | 0.00211 | 0.00406 |

| Harmonic ratio ML | 0.23 | 0.92 | 1.33320 | 0.02929 | 0.00187 | 0.00129 |

| Harmonic ratio AP | 0.61 | 0.86 | 1.46828 | 0.05386 | 0.00103 | 0.00396 |

| Dominant frequency VT | 0.22 | 0.78 | 1.82738 | 0.16622 | 0.03063 | 0.02044 |

| Dominant frequency ML | 0.22 | 0.84 | 0.85494 | 0.13286 | 0.01897 | 0.01257 |

| Dominant frequency AP | 0.23 | 0.88 | 1.58025 | 0.06492 | 0.00598 | 0.00417 |

| Amplitude of dominant frequency VT | 0.68 | 0.93 | 0.49412 | 0.04264 | 0.00026 | 0.00155 |

| Amplitude of dominant frequency ML | 1.00 | 0.91 | 0.47481 | 0.05827 | 9.2 × 10−9 | 0.00263 |

| Amplitude of dominant frequency AP | 0.11 | 0.85 | 0.51044 | 0.02357 | 0.00501 | 0.00198 |

| Width of dominant frequency VT | 0.14 | 0.80 | 0.76624 | 0.02141 | 0.00572 | 0.00267 |

| Width of dominant frequency ML | 0.39 | 0.90 | 0.79147 | 0.01238 | 0.00049 | 0.00066 |

| Width of dominant frequency AP | 0.14 | 0.80 | 0.75841 | 0.00611 | 0.00167 | 0.00075 |

| Range VT | 0.60 | 0.89 | 9.56290 | 9.84092 | 0.15828 | 0.55808 |

| Range ML | 0.47 | 0.95 | 7.95077 | 10.04315 | 0.13792 | 0.26707 |

| Range AP | 0.40 | 0.91 | 7.33318 | 7.13497 | 0.23150 | 0.32894 |

| Local divergence rate/stride VT | 0.75 | 0.87 | 2.11436 | 0.13693 | 0.00097 | 0.00919 |

| Local divergence rate/stride ML | 0.21 | 0.92 | 2.16970 | 0.15560 | 0.01077 | 0.00689 |

| Local divergence rate/stride AP | 0.58 | 0.86 | 2.19507 | 0.09652 | 0.00217 | 0.00707 |

| Sample entropy VT | 0.80 | 0.91 | 0.24764 | 0.00271 | 8.33 × 10−6 | 0.00013 |

| Sample entropy ML | 0.74 | 0.91 | 0.31207 | 0.00394 | 2.07 × 10−5 | 0.00018 |

| Sample entropy AP | 0.06 | 0.91 | 0.26908 | 0.00359 | 0.00064 | 0.00017 |

Note: We tested for structural differences between both measurement weeks using a repeated measures ANOVA (p-value) and Pearson correlations (r). We subsequently report mean values (mean) and variance components between-subjects (s2BS), within-subjects (s2WS) and due to sampling error (s2E).

Table A2.

Number of participants required for all gait characteristics.

| Small effect | Medium effect | Large effect | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohen’s d = 0.3 | Cohen’s d = 0.5 | Cohen’s d = 0.8 | |||||||

| r = 0.3 | r = 0.6 | r = 0.9 | r = 0.3 | r = 0.6 | r = 0.9 | r = 0.3 | r = 0.6 | r = 0.9 | |

| Gait quality composite | 303 | 208 | 114 | 110 | 76 | 42 | 44 | 31 | 18 |

| Walking speed | 259 | 158 | 56 | 95 | 58 | 22 | 38 | 24 | 10 |

| Stride frequency | 254 | 151 | 49 | 93 | 56 | 19 | 37 | 23 | 9 |

| Stride length | 251 | 148 | 44 | 92 | 54 | 17 | 37 | 22 | 8 |

| Standard deviation VT | 252 | 151 | 51 | 92 | 56 | 19 | 37 | 23 | 9 |

| Standard deviation ML | 270 | 169 | 67 | 99 | 62 | 25 | 40 | 25 | 11 |

| Standard deviation AP | 266 | 163 | 61 | 97 | 60 | 23 | 39 | 25 | 10 |

| Range VT | 258 | 158 | 59 | 94 | 58 | 23 | 38 | 24 | 10 |

| Range ML | 254 | 152 | 50 | 93 | 56 | 19 | 37 | 23 | 9 |

| Range AP | 262 | 162 | 62 | 96 | 60 | 23 | 39 | 24 | 10 |

| Walking speed variability | 250 | 148 | 45 | 91 | 54 | 18 | 37 | 22 | 8 |

| Stride time variability | 257 | 160 | 63 | 94 | 59 | 24 | 38 | 24 | 11 |

| Stride length variability | 253 | 152 | 50 | 92 | 56 | 19 | 37 | 23 | 9 |

| Stride autocorrelation VT | 268 | 173 | 77 | 98 | 63 | 29 | 39 | 26 | 13 |

| Stride autocorrelation ML | 252 | 150 | 48 | 92 | 55 | 18 | 37 | 23 | 8 |

| Stride autocorrelation AP | 263 | 167 | 71 | 96 | 61 | 27 | 39 | 25 | 12 |

| Amplitude of dominant frequency VT | 253 | 151 | 50 | 92 | 56 | 19 | 37 | 23 | 9 |

| Amplitude of dominant frequency ML | 251 | 151 | 51 | 92 | 56 | 19 | 37 | 23 | 9 |

| Amplitude of dominant frequency AP | 323 | 227 | 130 | 118 | 83 | 48 | 47 | 34 | 20 |

| Width of dominant frequency VT | 341 | 248 | 155 | 124 | 91 | 57 | 50 | 37 | 23 |

| Width of dominant frequency ML | 265 | 166 | 66 | 97 | 61 | 25 | 39 | 25 | 11 |

| Width of dominant frequency AP | 343 | 250 | 156 | 125 | 91 | 57 | 50 | 37 | 24 |

| Percentage of power <0.7 hz VT | 258 | 159 | 61 | 94 | 59 | 23 | 38 | 24 | 10 |

| Percentage of power <0.7 hz ML | 254 | 154 | 54 | 93 | 57 | 21 | 37 | 23 | 9 |

| Percentage of power <0.7 hz AP | 260 | 167 | 74 | 95 | 61 | 28 | 38 | 25 | 12 |

| Index of harmonicity VT | 260 | 157 | 54 | 95 | 58 | 21 | 38 | 24 | 9 |

| Index of harmonicity ML | 253 | 152 | 51 | 92 | 56 | 20 | 37 | 23 | 9 |

| Index of harmonicity AP | 262 | 162 | 62 | 95 | 59 | 24 | 38 | 24 | 10 |

| Harmonic ratio VT | 262 | 162 | 63 | 96 | 60 | 24 | 39 | 25 | 11 |

| Harmonic ratio ML | 273 | 172 | 72 | 99 | 63 | 27 | 40 | 26 | 12 |

| Harmonic ratio AP | 260 | 163 | 65 | 95 | 60 | 25 | 38 | 25 | 11 |

| Local divergence rate/stride VT | 256 | 157 | 59 | 93 | 58 | 23 | 38 | 24 | 10 |

| Local divergence rate/stride ML | 274 | 174 | 73 | 100 | 64 | 28 | 40 | 26 | 12 |

| Local divergence rate/stride AP | 261 | 164 | 66 | 95 | 60 | 25 | 38 | 25 | 11 |

| Sample entropy VT | 253 | 152 | 52 | 92 | 56 | 20 | 37 | 23 | 9 |

| Sample entropy ML | 253 | 153 | 53 | 92 | 56 | 20 | 37 | 23 | 9 |

| Sample entropy AP | 310 | 210 | 110 | 113 | 77 | 41 | 45 | 31 | 17 |

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S.v.S., M.P., S.R.L., J.H.v.D.; data collection, K.S.v.S., M.P., J.H.v.D.; data analysis, K.S.v.S.; data interpretation, K.S.v.S., M.P., S.R.L., J.H.v.D.; writing—original draft preparation, K.S.v.S.; writing—review and editing, M.P., S.R.L., J.H.v.D.; final approval, K.S.v.S., M.P., S.R.L., J.H.v.D.

Funding

This work was supported by the Dutch Organization for Scientific Research [NWO TOP NIG grant 91209021] and the Human Frontier Science program [HFSP long-term fellowship number LT001080/2017].

Conflicts of Interest

Between 06/2014 and 09/2015, K.v.S. was partially supported by a commercial grant of McRoberts BV (the Hague, the Netherlands). McRoberts B.V. had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Gillespie L.D., Robertson M.C., Gillespie W.J., Sherrington C., Gates S., Clemson L.M., Lamb S.E. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012;9:CD007146. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cummings S.R., Nevitt M.C., Kidd S. Forgetting falls: The limited accuracy of recall of falls in the elderly. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1988;36:613–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb06155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamb S.E., Jorstad-Stein E.C., Hauer K., Becker C. Development of a common outcome data set for fall injury prevention trials: The Prevention of Falls Network Europe consensus. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005;53:1618–1622. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gregg E.W., Pereira M.A., Caspersen C.J. Physical activity, falls, and fractures among older adults: A review of the epidemiologic evidence. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2000;48:883–893. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb06884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connell B.R., Wolf S.L. Environmental and behavioral circumstances associated with falls at home among healthy elderly individuals. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1997;78:179–186. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9993(97)90261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Ancum J.M., van Schooten K.S., Jonkman N.H., Huijben B., van Lummel R.C., Meskers C.G., Maier A.B., Pijnappels M. Gait speed assessed by a 4-m walk test is not representative of daily-life gait speed in community-dwelling adults. Maturitas. 2019;121:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rispens S.M., Van Dieën J.H., Van Schooten K.S., Lizama L.E.C., Daffertshofer A., Beek P.J., Pijnappels M. Fall-related gait characteristics on the treadmill and in daily life. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2016;13:12. doi: 10.1186/s12984-016-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rispens S.M., van Schooten K.S., Pijnappels M., Daffertshofer A., Beek P.J., van Dieen J.H. Do extreme values of daily-life gait characteristics provide more information about fall risk than median values? JMIR Res. Protoc. 2015;4:e4. doi: 10.2196/resprot.3931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiss A., Brozgol M., Dorfman M., Herman T., Shema S., Giladi N., Hausdorff J.M. Does the evaluation of gait quality during daily life provide insight into fall risk? A novel approach using 3-day accelerometer recordings. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair. 2013;27:742–752. doi: 10.1177/1545968313491004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Schooten K.S., Pijnappels M., Rispens S.M., Elders P.J., Lips P., Daffertshofer A., Beek P.J., van Dieen J.H. Daily-life gait quality as predictor of falls in older people: A 1-year prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0158623. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Schooten K.S., Pijnappels M., Rispens S.M., Elders P.J., Lips P., van Dieen J.H. Ambulatory fall-risk assessment: Amount and quality of daily-life gait predict falls in older adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2015;70:608–615. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helbostad J.L., Leirfall S., Moe-Nilssen R., Sletvold O. Physical fatigue affects gait characteristics in older persons. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2007;62:1010–1015. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.9.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manor B., Wolenski P., Guevaro A., Li L. Differential effects of plantar desensitization on locomotion dynamics. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2009;19:e320–e328. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Schooten K.S., Sloot L.H., Bruijn S.M., Kingma H., Meijer O.G., Pijnappels M., van Dieen J.H. Sensitivity of trunk variability and stability measures to balance impairments induced by galvanic vestibular stimulation during gait. Gait Posture. 2011;33:656–660. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamacher D., Hamacher D., Rehfeld K., Schega L.J.C.B. Motor-cognitive dual-task training improves local dynamic stability of normal walking in older individuals. Clin. Biomech. 2016;32:138–141. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2015.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henderson E.J., Lord S.R., Brodie M.A., Gaunt D.M., Lawrence A.D., Close J.C., Whone A.L., Ben-Shlomo Y. Rivastigmine for gait stability in patients with Parkinson’s disease (ReSPonD): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:249–258. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00389-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Folstein M.F., Folstein S.E., McHugh P.R. Mini-mental state. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dijkstra B., Kamsma Y., Zijlstra W. Detection of gait and postures using a miniaturised triaxial accelerometer-based system: Accuracy in community-dwelling older adults. Age Ageing. 2010;39:259–262. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Schooten K.S., Rispens S.M., Elders P.J., Lips P., van Dieen J.H., Pijnappels M. Assessing Physical Activity in Older Adults: Required Days of Trunk Accelerometer Measurements for Reliable Estimation. JAPA. 2015;23:9–17. doi: 10.1123/JAPA.2013-0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toebes M.J., Hoozemans M.J., Mathiassen S.E., Dekker J., van Dieen J.H. Measurement strategy and statistical power in studies assessing gait stability and variability in older adults. Ageing Clin. Exp. Res. 2016;28:257–265. doi: 10.1007/s40520-015-0390-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Schooten K.S., Rispens S.M., Pijnappels M., Daffertshofer A., van Dieen J.H. Assessing gait stability: The influence of state space reconstruction on inter- and intra-day reliability of local dynamic stability during over-ground walking. J. Biomech. 2013;46:137–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]