Abstract

Background

Proximal symphalangism is a rare disease with multiple phenotypes including reduced proximal interphalangeal joint space, symphalangism of the 4th and/or 5th finger, as well as hearing loss. At present, at least two types of proximal symphalangism have been identified in the clinic. One is proximal symphalangism-1A (SYM1A), which is caused by genetic variants in Noggin (NOG), another is proximal symphalangism-1B (SYM1B), which is resulted from Growth Differentiation Factor 5 (GDF5) mutations.

Case presentation

Here, we reported a Chinese family with symphalangism of the 4th and/or 5th finger and moderate deafness. The proband was a 13-year-old girl with normal intelligence but symphalangism of the 4th finger in the left hand and moderate deafness. Hearing testing and inner ear CT scan suggested that the proband suffered from structural deafness. Family history investigation found that her father (II-3) and grandmother (I-2) also suffered from hearing loss and symphalangism. Target sequencing identified a novel heterozygous NOG mutation, c.690C > G/p.C230W, which was the genetic lesion of the affected family. Bioinformatics analysis and public databases filtering further confirmed the pathogenicity of the novel mutation. Furthermore, we assisted the family to deliver a baby girl who did not carry the mutation by genetic counseling and prenatal diagnosis using amniotic fluid DNA sequencing.

Conclusion

In this study, we identified a novel NOG mutation (c.690C > G/p.C230W) by target sequencing and helped the family to deliver a baby who did not carry the mutation. Our study expanded the spectrum of NOG mutations and contributed to genetic diagnosis and counseling of families with SYM1A.

Keywords: Proximal symphalangism, Deafness, NOG mutation, Prenatal diagnosis

Background

Proximal symphalangism is a rare genetic disorder of congenital limb malformation, characterized by ankylosis of the proximal interphalangeal joints, carpal and tarsal bone fusion, and, in some cases, conductive deafness and premature ovarian failure [1, 2]. The typical features of proximal symphalangism are reduced proximal interphalangeal joint space, symphalangism of the 4th and/or 5th finger [3, 4]. As early as in 1916, Cushing has described an American family with ankylosis of the proximal interphalangeal joints, and he named this heterozygote autosomal dominant disease as symphalangism [5].

At present, there are two types of diseases in the proximal symphalangism family: (1) Proximal symphalangism-1A (SYM1A, OMIM # 185800), which iss caused by genetic variants in Noggin (NOG) [6, 7]; (2) Proximal symphalangism-1B (SYM1B), which is resulted from Growth Differentiation Factor 5 (GDF5) mutations [8, 9]. In addition, some other diseases may be also related to proximal symphalangism, such as tarsal-carpal coalition syndrome, multiple synostoses syndrome, and brachydactyly, etc. [10, 11].

In this study, we employed target sequencing to explore the genetic lesion of a Chinese family with symphalangism of the 4th and/or 5th finger and moderate deafness. A novel mutation (c.690C > G/p.C230W) of NOG was identified in all affected individuals in this family. Furthermore, after genetic counseling and prenatal diagnosis with us, the mother successfully delivered a baby girl who did not carry the mutation.

Case presentation

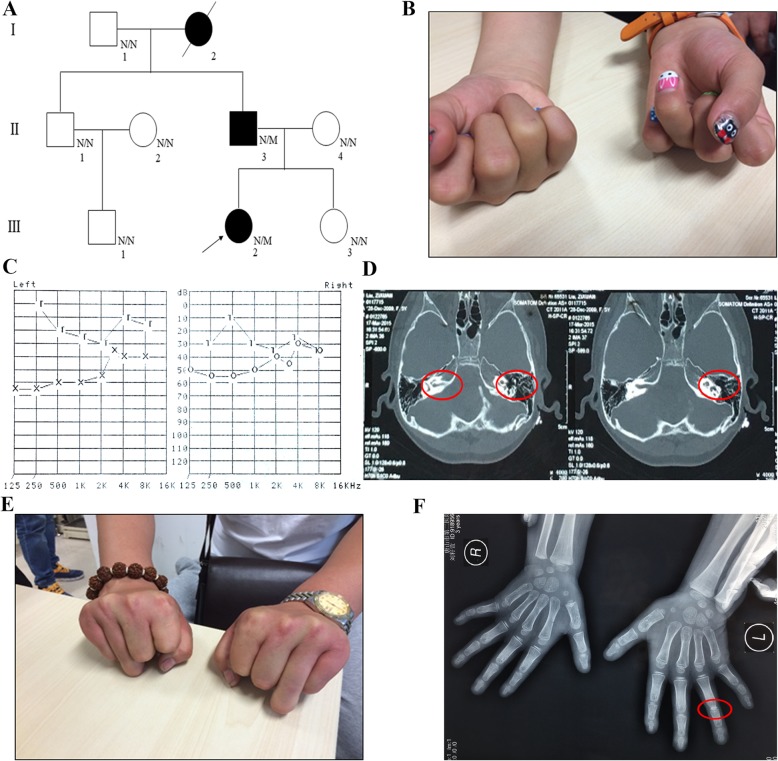

A family from North of China (Hebei Province) with eight members across three generations participated in the study (Fig. 1a). The proband (III-2) was a 13-year-old girl with normal intelligence but symphalangism of the 4th finger in the left hand (Fig. 1b) and moderate deafness (Fig. 1c). Inner ear CT scan found abnormal inner ear structure (cochlear hypoplasia) and abnormal calcification (inner ear bone thickening and increased density) (Fig. 1d). Family history investigation found that her father (II-3) and grandmother (I-2) also suffered from hearing loss and symphalangism (Fig. 1a, e). Her grandmother has died six years ago. Her father showed the symphalangism of the 4th finger in left hand (Fig. 1e, f). He had performed the vestibulotomy and recovered the hearing one year ago. They went to the Department of Reproductive Genetics, HeBei General Hospital because the mother was pregnant with the second baby. They wanted to detect whether the second baby was normal or not.

Fig. 1.

The Clinical data of the family. a The pedigree of this family. Black circles/squares are affected, white circles/squares are unaffected. N means Normal, M indicates Mutation. Arrow indicates the proband. b The proband showed the symphalangism of the 4th finger in the left hand. c Hearing testing suggests the proband suffering from moderate deafness. d Inner ear CT showed abnormal inner ear structure and abnormal calcification. The red circles marked the abnormal regions which indicated cochlear hypoplasia, inner ear bone thickening and increased density. e The symphalangism of the 4th finger in II-3. f Hands X-ray of III-2. The red circles marked the abnormal regions

Genetic analysis

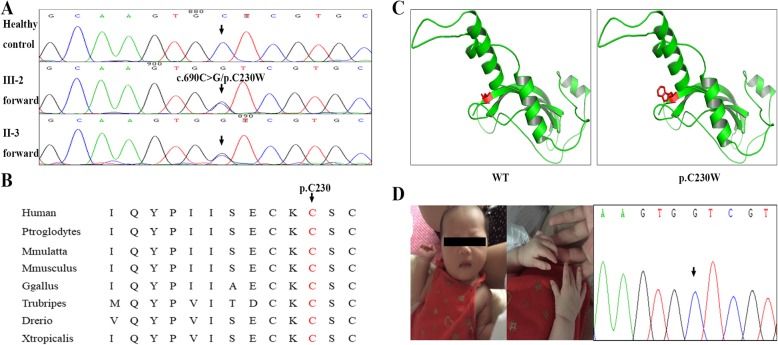

We selected the proband’s genomic DNA to perform the target sequencing to detect the disease-causing mutations by Sinopath Diagnosis Company (Beijing, China). Target sequencing yielded 3.71 Gb of data with 99.088% coverage of the target region and 97.530% of the target covered over 10×. After filtering dbSNP132, 1000G, EXAC, and GenomAD database (MAF < 0.01), only 12 mutation were left. We then conducted the co-segregation analysis by Sanger sequencing and only seven variants were exist in affected individuals and were absent in healthy members (Table 1). We further performed the bioinformatics analysis including MutationTaster, SIFT, Polyphen-2, PANTHER, ToppGene function analysis, OMIM clinical phenotype analysis and ACMG classification (Table 1), we highly suspected the novel mutation (c.690C > G/p.C230W) of NOG, belonging to PM1 and PM2 in ACMG guidelines [12], was responsible for the family with SMY1A. This mutation resulted in a substitution of in polar amino acid cysteine by nonpolar amino acid tryptophan in the codon 230 of exon 1 of NOG gene, and was not presented in our 200 control cohorts. Noggin amino acid sequence alignment analysis suggested that this mutation was located in a highly evolutionarily conserved site (Fig. 2b). In addition, we also constructed a part model of the Noggin protein using SWISS-MODEL (https://swissmodel.expasy.org) (Fig. 2c) and, after applying SDM software (http://marid.bioc.cam.ac.uk/sdm2/prediction) to analyze the structure, it was found that this novel mutation might increase the solvent accessibility (WT:16.9% and Mutant: 39.9%) and reduce the stability of the Noggin protein.

Table 1.

The mutations list after data filtering and co-segregation analysis

| CHR | POS | RB | AB | Gene | Mutation | SIFT | PolyPhen-2 | MutationTaster | PANTHER | OMIM clinical phenotype | ToppGene function | ACMG classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45,481,060 | C | T | UROD | NM_000374: c.994C > T, p.R332C | 0,D | 0.94,D | 0.99,D | – | AD or AR: Porphyria cutanea tarda | heme biosynthetic process | BP5 |

| 2 | 149,216,410 | G | A | MBD5 | NM_018328: c.83G > A, p.R28H | 0,D | 0.99,D | 0.99,D | P | AD: Mental retardation | response to growth hormone | BP5 |

| 2 | 189,953,479 | G | T | COL5A2 | NM_000393: c.587G > T, p.A196D | 0.29,T | 0.98,D | 0.99,D | – | AD: Ehlers-Danlos syndrome | regulation of endodermal cell differentiation | BP4, BP5 |

| 3 | 38,674,642 | G | A | SCN5A | NM_198056: 157G > A, p.R53W | 0,D | 0.36,B | 0.95,D | P | AD: Atrial fibrillation | voltage-gated sodium channel activity | BP4, BP5 |

| 3 | 184,953,112 | G | A | EHHADH | NM_001966: c.317G > A, p.A106V | 0,D | 0.99,D | 0.99,D | P | AD: Fanconi renotubular syndrome | peroxisomal transport | BP5 |

| 17 | 48,701,856 | G | A | CACNA1G | NM_018896: c.6365G > A, p.R2122H | 0.04,D | 0.01,B | 0.8,D | P | AD: Spinocerebellar ataxia | voltage-gated calcium channel | BP4, BP5 |

| 17 | 54,672,274 | C | G | NOG | NM_005450: c.690C > G, p.C230W | 0,D | 0.99,D | 0.99,D | D | AD: Symphalangism proximal | fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling pathway | PM1, PM2 |

CHR Chromosome, POS position, RB reference sequence base, AB alternative base identified, D damaging, P probably damaging, B Benign, T Tolerated, AR autosomal recessive, AD autosomal dominant, BP Benign Supporting, PM Pathogenicity Moderate

Fig. 2.

Genetic analysis of the family. a Sanger DNA sequencing chromatogram demonstrates the heterozygosity for a NOG mutation (c.690C > G/p.C230W). b Analysis of the mutation and protein domains of Noggin. The C230 affected amino acid locates in the highly conserved amino acid region in different mammals (from Ensembl). The black arrow and red words show the C230 site. c Swiss-model analyzed the Noggin structures of WT and Mutated (p.C230W). d The healthy hands of III-3 and normal sequences of amniotic fluid DNA

Prenatal diagnosis

When the parents came to our hospital, the mother has been pregnant with the second baby for 17 weeks and they wanted to have a healthy baby. According to ACMG classification, the novel mutation (c.690C > G/p.C230W) of NOG belongs to PM1 and PM2. Simultaneously, target sequencing only identified this mutation as a pathogenic variant. So, we highly believed the novel mutation (c.690C > G/p.C230W) of NOG was the genetic lesion of the family with proximal symphalangism and hearing loss. We then performed the Sanger sequencing of amniotic fluid DNA to detect the mutation, fortunately, the results showed a normal allele of the second baby. And 22 weeks later, the mother delivered a 3.4-kg healthy girl (Fig. 2d).

Discussion

The human NOG gene encoding Noggin protein is located on chromosome 17q22, and it consists of one exon, spanning approximately 1.9 kilobases (kb) [6]. Noggin protein is involved in the development of many body tissues, including nerve tissue, muscles, and bones and the role of Noggin in bone development makes it significant for proper joint formation [13]. According to previous researches, Noggin protein can interact with bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) and regulate the development of bone and other tissues [14]. In detail, the Noggin protein regulates the activity of BMPs by binding to them and blocking them from attaching to the downstream receptor, which results in a decrease in BMP signaling [15]. In our research, the novel mutation (c.690C > G/p.C230W) of NOG can increase the solvent accessibility and reduce the stability of the Noggin, which may active the BMP signal pathway and lead to bone diseases.

In 1999, five NOG mutations were identified in unrelated families with symphalangism (SYM1A) and a de novo mutation in a patient with unaffected parents [6]. Interestingly, a wide variety of bone development anomalies, including tarsal/carpal coalition syndrome [10], brachydactyly [16], multiple synostoses syndrome [17], Stapes ankylosis with broad thumbs and toes [18], have been reported in patients with NOG mutations. Similar observations were also reported in the families even with the same mutation [16, 19]. Therefore, the pleiotropic types of bone diseases and significant genetic heterogeneity make it difficult to be diagnosed. We summarized the previous reports and found that approximately 57 mutations (60 patients) of NOG have been identified in different types of disorders (Table 2).

Table 2.

The summary of reported mutations of NOG

| No. | Mutation | Phenotypes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | p. Leu20fs | Multiple synostoses syndrome | Takahashi et al. (2001) |

| 2 | p. Pro35Ala | Brachydactyly type B | Lehmann et al. (2007) |

| 3 | p. Pro35Ser | Teunissen-Cremers syndrome | Hirshoren et al. (2008) |

| 4 | p. Pro35Ser | Proximal symphalangism | Mangino et al. (2002) |

| 5 | p. Pro35Ser | Brachydactyly type B | Lehmann et al. (2007) |

| 6 | p. Pro35Arg | Proximal symphalangism | Gong et al. (1999) |

| 7 | p. Pro35Arg | Tarsal–carpal coalition syndrome | Dixon et at. (2001) |

| 8 | p. Ala36Pro | Brachydactyly type B | Lehmann et al. (2007) |

| 9 | p. Pro37Arg | Tarsal–carpal coalition syndrome | Debeer et al. (2004) |

| 10 | p. Pro42Ala | Multiple synostoses syndrome | Debeer et al. (2005) |

| 11 | p. Pro42Ser | Proximal symphalangism | Sha et al. (2019) |

| 12 | p. Pro42Arg | Multiple synostoses syndrome | Oxley et al. (2008) |

| 13 | p. Pro42Thr | Multiple synostoses syndrome | Aydin, H et al. (2013) |

| 14 | p. Val44fs | Teunissen-Cremers syndrome | Weekamp et al. (2005) |

| 15 | p. Glu48Lys | Brachydactyly type B | Lehmann et al. (2007) |

| 16 | p. Glu48Lys | Proximal symphalangism | Kosaki et al. (2004) |

| 17 | p. Pro50Arg | Tarsal–carpal coalition syndrome | Debeer et al. (2005) |

| 18 | p. Asp55Tyr | Proximal symphalangism | Xiong et al. (2019) |

| 19 | p. Glu85fs | Stapes ankylosis with broad thumb and toes | Brown et al. (2002) |

| 20 | p. Arg87fs | Multiple synostoses syndrome | Lee et al. (2014) |

| 21 | p. Gly91Cys | Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva | Kaplan et al. (2008) |

| 22 | p. Gly92Arg | Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva | Kaplan et al. (2008) |

| 23 | p. Gly92Glu | Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva | Kaplan et al. (2008) |

| 24 | p. Ala95Thr | Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva | Kaplan et al. (2008) |

| 25 | p. Ala102fs | Proximal symphalangism | Thomeer et al. (2011) |

| 26 | p. Gln110X | Stapes ankylosis with broad thumb and toes | Brown et al. (2002) |

| 27 | p. Leu129X | Proximal symphalangism | Takahashi et al. (2001) |

| 28 | p.Gln131X | Stapes ankylosis with broad thumbs and toes | Takashi etal. (2014) |

| 29 | p. Lys133X | Stapes ankylosis with broad thumb and toes | Takano et al. (2016) |

| 30 | p. Arg136Cys | Proximal symphalangism | Masuda et al. (2014) |

| 31 | p. Trp150Cys | Proximal symphalangism | Pan et al. (2015) |

| 32 | p. Cys155Phe | Stapes ankylosis with symphalangism | Usami et al. (2012) |

| 33 | p. Cys155Ser | Proximal symphalangism | Usami et al. (2012) |

| 34 | p. Arg167Gly | Brachydactyly type B | Lehmann et al. (2007) |

| 35 | p. Arg167Cys | Proximal symphalangism | Liu et al. (2015) |

| 36 | p. Cys184Tyr | Proximal symphalangism | Takahashi et al. 2001 |

| 37 | p. Cys184Phe | Proximal symphalangism | Usami et al. 2012 |

| 38 | p. Pro187Ser | Brachydactyly type B | Lehmann et al. (2007) |

| 39 | p. Pro187Ala | Proximal symphalangism | Ganaha et al. (2015) |

| 40 | p. Glu188fs | Teunissen-Cremers syndrome | Weekamp et al. (2005) |

| 41 | p. Gly189Cys | Proximal symphalangism | Gong et al. (1999) |

| 42 | p. Met190Val | Multiple synostoses syndrome | Oxley et al. (2008) |

| 43 | p. Leu203Pro | Teunissen-Cremers syndrome | Weekamp et al. (2005) |

| 44 | p. Arg204Leu | Tarsal/carpal coalition syndrome | Dixon et al. (2001) |

| 45 | p. Arg204Gln | Tarsal-carpal coalition syndrome | Das et al. (2018) |

| 46 | p. Trp205X | Multiple synostoses syndrome | Dawson et al. (2006) |

| 47 | p. Trp205Cys | Facioaudiosymphalangism syndrome | van den Ende et al. (2005) |

| 48 | p. Trp205fs | Stapes ankylosis with broad thumb and toes | Emery et al. (2009) |

| 49 | p. Cys215X | Stapes ankylosis with broad thumb and toes | Usami et al. (2012) |

| 50 | p. Trp217Gly | Multiple synostoses syndrome | Gong et al. (1999) |

| 51 | p. Ile220Asn | Proximal symphalangism | Gong et al. (1999) |

| 52 | p. Ile220fs | Proximal symphalangism | Gong et al. (1999) |

| 53 | p. Tyr222Asp | Proximal symphalangism | Gong et al. (1999) |

| 54 | p. Tyr222Cys | Proximal symphalangism | Gong et al. (1999) |

| 55 | p. Tyr222Cys | Tarsal–carpal coalition syndrome | Dixon et al. (2001) |

| 56 | p. Pro223Leu | Proximal symphalangism | Gong et al. (1999) |

| 57 | p. Cys228Gly | Stapes ankylosis with broad thumb and toes | Ishino et al. (2015) |

| 58 | p. Cys228Ala | Multiple synostoses syndrome | Ganaha et al. (2015) |

| 59 | p. Cys230Tyr | Multiple synostoses syndrome | Bayat et al. (2016) |

| 60 | p. Cys230Trp | Proximal symphalangism | Present study |

| 61 | p. Cys232Trp | Multiple synostoses syndrome | Rudnik-Schöneborn et al. (2010) |

Bold words indicate the patients with deafness

In this study, a family with symphalangism and moderate deafness was investigated by target sequencing. Genetic analysis found a novel mutation (c.690C > G/p.C230W) of NOG in two affected members. Of note, both of two patients with p.C230W in the family were associated with hearing loss. To date, 29 mutations have been reported in symphalangism patients related to deafness (Table 2) [11]. And the mutation p.C230W was the fifth report related to NOG mutation, although some Chinese journals have also published some reported mutations. Meanwhile, this difference also suggested that there were still a lot of novel mutations need to discovery in Chinese population.

The p.C230W mutation disrupts the cysteine knot motif of the C-terminal domain of Noggin (amino acids 155–232), which contains a series of nine cysteine residues and was shown to target the molecule to a specific receptor protein [20, 21]. The similar mutations (p.C228G, p.C228S, p.C230Y and p.C232W) have been identified in patients with symphalangism and hearing loss, which indicated that mutations in cysteine residues may be related to abnormal development of auditory ossicles and hearing loss [19, 22–24].

In clinical genetics, the aim of mutation detection is to make contributions to genetic diagnosis and counseling. In this study, we identified the genetic lesion of the family by target sequencing. All the filtered data were shown in Table 1. We not only performed the informatics analysis of the novel mutation by multi-different algorithm based bioinformatics programs, but also followed the ACMG guidelines to estimate the pathogenicity of the novel mutation strictly (PM1 and PM2). Finally, we highly believed that the novel mutation (p.C230W) of NOG may be the genetic lesion of the family. We then assisted the family to get a healthy baby by amniotic fluid DNA sequencing referring to other people’s research [25]. Prenatal diagnosis not only helped the patient to delivery healthy baby and improved the population quality but also relieved psychological and financial stress [26]. Our study provided a successful example for genetic counseling and prenatal diagnosis of patients with SYM1A.

Conclusions

We reported a novel NOG mutation (c.690C > G/p.C230W) in a three-generation family with SYM1A. And we helped them delivery a girl baby who did not carry the mutation by genetic counseling and prenatal diagnosis. Our study not only presented the important role of NOG in proximal symphalangism and deafness but also expanded the spectrum of NOG mutations and contributed to genetic diagnosis and counseling of families with SYM1A.

Acknowledgements

We thank all subjects for participating in this study.

Abbreviations

- BMPs

Bone morphogenetic proteins

- GDF5

Growth Differentiation Factor 5

- kb

Kilobases

- NOG

Noggin

- SYM1A

proximal symphalangism-1A

- SYM1B

proximal symphalangism-1B

Authors’ contributions

C M and L L carried out the sample collecting and genetic testing, F-N W, H-S T and Y L collected the clinical data, R Y performed the bioinformatics analysis, Y-L L and L-L F designed the project and wrote the manuscript, and L-L F revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

During the whole course of this study, the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation and manuscript preparation were mainly supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81800220) and Hunan province Natural Science Foundation (2019JJ50890). Part of the data analysis, which is the prenatal diagnosis was supported by Hebei Science and Technology Plan Project (17277728D).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from each individual and the investigation was approved by the Institutional Review Board of HeBei General Hospital.

Consent for publication

Written consent was obtained from all the participants or their guardians for the publication of this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Cong Ma and Lv Liu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Liang-Liang Fan, Email: swfanliangliang@csu.edu.cn.

Ya-Li Li, Email: lyl8703@sina.com.

References

- 1.Plett SK, Berdon WE, Cowles RA, Oklu R, Campbell JB. Cushing proximal symphalangism and the NOG and GDF5 genes. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38(2):209–215. doi: 10.1007/s00247-007-0675-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kadi N, Tahiri L, Maziane M, Mernissi FZ, Harzy T. Proximal symphalangism and premature ovarian failure. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79(1):83–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2011.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pasha AS, Weimer M. Symphalangism. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(9):2327. doi: 10.1002/art.39752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cushing H. Hereditary anchylosis of the proximal phalangeal joints (symphalangism) Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1915;2002(401):4–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cushing H. Hereditary Anchylosis of the proximal Phalan-Geal joints (Symphalangism) Genetics. 1916;1(1):90–106. doi: 10.1093/genetics/1.1.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gong Y, Krakow D, Marcelino J, Wilkin D, Chitayat D, Babul-Hirji R, Hudgins L, Cremers CW, Cremers FP, Brunner HG, et al. Heterozygous mutations in the gene encoding noggin affect human joint morphogenesis. Nat Genet. 1999;21(3):302–304. doi: 10.1038/6821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sha Y, Ma D, Zhang N, Wei X, Liu W, Wang X. Novel NOG (p.P42S) mutation causes proximal symphalangism in a four-generation Chinese family. BMC Med Genet. 2019;20(1):133. doi: 10.1186/s12881-019-0864-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leonidou A, Irving M, Holden S, Katchburian M. Recurrent missense mutation of GDF5 (p.R438L) causes proximal symphalangism in a British family. World J Orthop. 2016;7(12):839–842. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v7.i12.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seemann P, Schwappacher R, Kjaer KW, Krakow D, Lehmann K, Dawson K, Stricker S, Pohl J, Ploger F, Staub E, et al. Activating and deactivating mutations in the receptor interaction site of GDF5 cause symphalangism or brachydactyly type A2. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(9):2373–2381. doi: 10.1172/JCI25118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das Bhowmik A, Salem Ramakumaran V, Dalal A. Tarsal-carpal coalition syndrome: report of a novel missense mutation in NOG gene and phenotypic delineation. Am J Med Genet A. 2018;176(1):219–224. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takano K, Ogasawara N, Matsunaga T, Mutai H, Sakurai A, Ishikawa A, Himi T. A novel nonsense mutation in the NOG gene causes familial NOG-related symphalangism spectrum disorder. Hum Genome Var. 2016;3:16023. doi: 10.1038/hgv.2016.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marcelino J, Sciortino CM, Romero MF, Ulatowski LM, Ballock RT, Economides AN, Eimon PM, Harland RM, Warman ML. Human disease-causing NOG missense mutations: effects on noggin secretion, dimer formation, and bone morphogenetic protein binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(20):11353–11358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201367598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt-Bleek K, Willie BM, Schwabe P, Seemann P, Duda GN. BMPs in bone regeneration: less is more effective, a paradigm-shift. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2016;27:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wan DC, Pomerantz JH, Brunet LJ, Kim JB, Chou YF, Wu BM, Harland R, Blau HM, Longaker MT. Noggin suppression enhances in vitro osteogenesis and accelerates in vivo bone formation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(36):26450–26459. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703282200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehmann K, Seemann P, Silan F, Goecke TO. Irgang S, Kjaer KW, Kjaergaard S, Mahoney MJ, Morlot S, Reissner C, et al. A new subtype of brachydactyly type B caused by point mutations in the bone morphogenetic protein antagonist NOGGIN. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(2):388–396. doi: 10.1086/519697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee BH, Kim OH, Yoon HK, Kim JM, Park K, Yoo HW. Variable phenotypes of multiple synostosis syndrome in patients with novel NOG mutations. Joint Bone Spine. 2014;81(6):533–536. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomeer HG, Admiraal RJ, Hoefsloot L, Kunst HP, Cremers CW. Proximal symphalangism, hyperopia, conductive hearing impairment, and the NOG gene: 2 new mutations. Otology Neurotol. 2011;32(4):632–638. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318211fada. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ganaha A, Kaname T, Akazawa Y, Higa T, Shinjou A, Naritomi K, Suzuki M. Identification of two novel mutations in the NOG gene associated with congenital stapes ankylosis and symphalangism. J Hum Genet. 2015;60(1):27–34. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2014.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groppe J, Greenwald J, Wiater E, Rodriguez-Leon J, Economides AN, Kwiatkowski W, Affolter M, Vale WW, Izpisua Belmonte JC, Choe S. Structural basis of BMP signalling inhibition by the cystine knot protein noggin. Nature. 2002;420(6916):636–642. doi: 10.1038/nature01245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown DJ, Kim TB, Petty EM, Downs CA, Martin DM, Strouse PJ, Moroi SE, Milunsky JM, Lesperance MM. Autosomal dominant stapes ankylosis with broad thumbs and toes, hyperopia, and skeletal anomalies is caused by heterozygous nonsense and frameshift mutations in NOG, the gene encoding noggin. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71(3):618–624. doi: 10.1086/342067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rudnik-Schoneborn S, Takahashi T, Busse S, Schmidt T, Senderek J, Eggermann T, Zerres K. Facioaudiosymphalangism syndrome and growth acceleration associated with a heterozygous NOG mutation. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A(6):1540–1544. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishino T, Takeno S, Hirakawa K. Novel NOG mutation in Japanese patients with stapes ankylosis with broad thumbs and toes. Eur J Med Genet. 2015;58(9):427–432. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bayat A, Fijalkowski I, Andersen T, Abdulmunem SA, van den Ende J, Van Hul W. Further delineation of facioaudiosymphalangism syndrome: description of a family with a novel NOG mutation and without hearing loss. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170(6):1479–1484. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abou Tayoun AN, Spinner NB, Rehm HL, Green RC, Bianchi DW. Prenatal DNA sequencing: clinical, counseling, and diagnostic laboratory considerations. Prenat Diagn. 2018;38(1):26–32. doi: 10.1002/pd.5038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vermeesch JR, Voet T, Devriendt K. Prenatal and pre-implantation genetic diagnosis. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17(10):643–656. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.