Abstract

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome is the most severe phase of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection. Recent studies have seen an effort to isolate phytochemicals from plants to repress HIV, but less studies have focused on the effects of these phytochemicals on the activities of enzymes/transporters involved in the metabolism of these drugs, which is one of the aims of this study and, to examine the antiviral activity of these compounds against HIV-1 protease enzyme using computational tools. Centre of Awareness-Food Supplement (COA®-FS) herbal medicine, has been said to have potential anti-HIV features. SWISSTARGETPREDICTION and SWISSADME servers were used for determination of the enzymes/transporters involved in the metabolism of these protease inhibitor drugs, (PIs) (Atazanavir, Lopinavir, Darunavir, Saquinavir) and the effects of the selected phytochemicals on the enzymes/transporters involved in the metabolism of these PIs. Using Computational tools, potential structural inhibitory activities of these phytochemicals were explored. Two sub-families of Cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP3A4 and CYP2C19) and Permeability glycoprotein (P-gp) were predicted to be involved in metabolism of the PIs. Six phytochemicals (Geranin, Apigenin, Fisetin, Luteolin, Phthalic acid and Gallic acid) were predicted to be inhibitors of CYP3A4 and, may slowdown elimination of PIs thereby maintain optimal PIs concentrations. Free binding energy analysis for antiviral activities identified four phytochemicals with favourable binding landscapes with HIV-1 protease enzyme. Epigallocatechin gallate and Kaempferol-7-glucoside exhibited pronounced structural evidence as potential HIV-1 protease enzyme inhibitors. This study acts as a steppingstone toward the use of natural products against diseases that are plagued with adverse drug-interactions.

Keywords: Pharmaceutical chemistry, Pharmaceutical science, HIV protease, Phytochemical, Enzymes, Transporters, Antiviral activities

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that approximately 72 million people had already been infected with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) worldwide in 2017 (WHO, 2018). Of these records, the sub-Saharan Africa was the most heavily affected region, accounting for over 69% of all infected cases. The Joint United Nations (UNAIDS report) (2018) states that although there is a steady decline in Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) related illnesses over the past decade; however, the global rate of new HIV infections is not falling fast enough to reach the milestones set in place by 2020 (WHO, 2018).

Of the enzymes involved in the replication cycle of HIV in human immune cells, the HIV protease enzyme is one of the most significant enzymes required to produce mature and infectious HIV virions. This has allowed the enzyme to be the utmost protuberant focus for anti-HIV inhibitors (Scholar, 2011). The protease enzyme is a C2-symmetric active homodimer, consisting of a non-covalently connected dimer of 99 amino acid residues each to form an active homodimer. The two monomeric chains assemble to form an enclosed tunnel covered by two flaps that characteristically “open and close” upon substrate binding (Levy and Caflisch, 2003). The effective activity of HIV protease in the viral cycle is crucial for the maturation of infectious HIV virions (Brik and Wong, 2003). Therefore, there is no doubt that inhibition or inactivation of the enzyme will result to the production of less viable and noninfectious virions and will eventually lead to a reduction in the spread of the infection to vulnerable hosts or cells.

Viral replication by HIV is inhibited by protease inhibitor drugs (PIs) by binding to the HIV proteases and subsequently obstructing the proteolytic cleavage of the protein precursors which are important for making of mature HIV virions (Soontornniyomkij et al., 2014). PIs are designed to look like the natural substrates of the viral protease. They prevent the HIV-1 protease from cleaving the precursor proteins by precisely binding the active site of the virus protease, which eventually results in the development of immature non-infectious viral particles (Geretti and Easterbrook, 2001). In South Africa, the current Adult antiretroviral therapy guidelines in use recommend four FDA-approved PIs, atazanavir, darunavir, lopinavir and saquinavir, with ritonavir being used as boosters with the drugs (Carmona and Nash, 2017).

The use of traditional herbal medicine is gaining more popularity in the treatment of diseases such as HIV in many countries, (WHO, 2018) despite the possibility of Herbal-drug interactions and toxicity that could occur as a result of co-administration of Herbs and antiretroviral drugs (ARVs). Nonetheless, there have been significant increases in the usage of herbal medicine not only in developing countries but also in developed countries, which has caused great public health concern among scientists and physicians who are sometimes not sure about the safety of herbal preparations especially when used concurrently with regular orthodox medications such as ARV (WHO, 2018). In South Africa, many patients undergoing antiretroviral therapy also consume traditional herbal medicine (Nlooto and Naidoo, 2014). One of the most consumed herbal medicine by HIV patients in South Africa is COA®-FS (Centre of Awareness) herbal medicine (COA®-FS) (Nlooto and Naidoo, 2014).

COA®-FS herbal medicineis produced by Centre of Awareness (COA), an organization, based in Cape Coast, Ghana. According to the producer, the COA®-FS herbal medicine contains six Africa plants namely; Azadirachta indica, Persea americana, Carica papaya. Spondias mombin, Ocimum viride and Vernonia amygdalina (FDA/DRID/HMD/HMU/16/0981, 2016). HIV patients purchase it as immune boosters against HIV/AIDS and as treatments for other diseases (https://www.coadrugs.org).

Previous studies have showed that HIV positive patients use herbal medicine concurrently with prescribed protease inhibitor drugs. No or few studies on the effect of the chemical constituents of the herbal medicines on the enzymes and transporters involved in the metabolism of drugs such as PI drugs have been done, therefore there is paucity of evidence or information on the effectiveness and the possibility of serious side effects of phytochemical compounds from herbal medicine on prescribed protease inhibitor drugs. This has motivated this study to examine the pharmacokinetic effect of numerous phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicineon the activities of major enzymes and transporters involved in the metabolism of FDA-approved protease inhibitor drugs used in South Africa (Atazanavir, Lopinavir, Darunavir, Saquinavir) commonly use in South Africa and to examine their antiviral activities as potent inhibitors of HIV-1 protease enzyme using in silico pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetic analysis. These phytochemical compounds will then be compared with FDA approved drugs against the HIV-1 protease enzyme to identify the least toxic and most favourable compounds that may act as lead molecules for experimental analysis.

In a previous study in our lab, COA®-FS herbal medicine and its component plants were subjected to Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/biochemistry-genetics-and-molecular-biology/gas-chromatography-mass-spectrometry (GC-MS) to identify the phytochemical compounds present in them (Boadu, 2019; Nwabuife, 2019). A comprehensive literature search on the antiviral activities of phytochemical compounds from COA® and its component plants was as well done. Fifteen of the phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine and its component plants were selected for this study, to examine the transporters and enzymes involved in the metabolisms of the selected phytochemical compounds and metabolism of four FDA-approved PIs (Atazanavir, Lopinavir, Darunavir, Saquinavir), and to evaluate the effects of these phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine and its component plants on the activities of enzymes and transporters involved in drug metabolism of the four PIs. In addition, the antiviral activity of these phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicineand its constituent plants were examined using molecular docking and dynamics simulations.

Table 1 showed the fifteen selected phytochemical compounds present in the COA®-herbal medicineand its components plants. Nine of the selected phytochemical compounds (EGA, EPG, LNT, BIT, GA, IST, STG, PTA and NGN) were present in the COA®-FS herbal medicinebut the remaining 6 compounds were reported in literature to be present in different parts of the six plants.

Table 1.

Selected phytochemicals with antiviral activities present COA®-FS herbal medicineand its component plants.

| Compounds Name | Plant name | Extracts | Plant parts | Literature Reference | COA-FS herbal medicine |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GC-MS | Extracts | Reference | |||||

| EGA | Spondias mombin, Carica papaya | Hydroethanolic, | Leaf | (Shin et al., 2005) Nwabuife, 2019 | + | Ethanolic, Hexane, | Boadu, 2019; Nwabuife, 2019 |

| CHD | Azadirachta indica, Vernonia amygdalina, Carica papaya | Methanolic, hexane, ethanol, ethylacetate, Dichloromethane | Leaf | (Dineshkumar and Rajakumar, 2017) Boadu, 2019; Nwabuife, 2019 | + | Ethanol, hexane | Boadu, 2019; Nwabuife, 2019 |

| LNT | Azadirachta indica, Vernonia amygdalina | Chloroform, Dichloromethane | Leaf | (Siddiqui et al., 2006) Boadu, 2019 | + | Dichloromethane | Boadu, 2019 |

| BIT | Carica papaya | Hydrothanolic | Seed, leaf | (Kermanshai et al., 2001) | + | Ethanolic | Boadu, 2019 |

| GA (methyl salicylate) | Persea Americana | Methanolic | Pulp, Leaf | (Hurtado-Fernández et al., 2014) | + | Standard | Boadu, 2019 |

| IST | Vernonia amygdalina | Chloroform, Dichloromethane, ethanol, | Leaf | (Adewole et al., 2018) Boadu, 2019 | + | Dichloromethane | Boadu, 2019 |

| STG | Carica papaya, Persea Americana, Vernonia amygdalina, Azadirachta indica | Petroleum ether, Hydroethanolic, hexane, Dichloromethane, ethylacetate, ethanol | Leaf | (Rashed et al., 2013; Monika and Geetha, 2015; Boadu, 2019; Nwabuife, 2019) | + | Hexane, Dichloromethane, ethylacetate | Boadu, 2019; Nwabuife, 2019 |

| PTA | Carica papaya, Azadirachta indica | Methanolic, Crude oil, hexane, Dichloromethane, ethylacetate, ethanol | Leaf | (Sajin et al., 2015; Boadu, 2019; Babatunde et al., 2019) | + | Hexane, ethylacetate | Boadu, 2019; Nwabuife, 2019 |

| NGN | Persea Americana, Carica papaya | Methanolic, Ethylacetate | Leaf | (Hurtado-Fernández et al., 2014; Nwabuife, 2019 | - | Methanolic, Ethylacetate | |

| K7G | Carica papaya | Ethanolic, aqueous | Fruit/pulp, dry leaf | (Kongkachuichai and Charoensiri, 2010; Lako, 2007) | - | ND | |

| EGCG | Persea Americana | HydroMethanolic | seed | (Calderón-Oliver et al., 2015) | - | ND | |

| LUT | Vernonia amygdalina, Carica papaya | Ethanolic, methanolic | Leaf, Fruit/pulp | (Igile et al., 1995) | - | ND | |

| GER | Spondiasmombin | Hydroalcoholic | Leaf | (Mukhtar et al., 2008) | - | ND | |

| APG | Carica papaya | Ethanolic, aqueous | Fruit/pulp | Franke et al., 2004 | - | ND | |

| FST | Carica papaya | Ethanolic, aqueous | Fruit/pulp | Lako, 2007 | - | ND | |

Key: + means present, - means not present, ND means not detected.

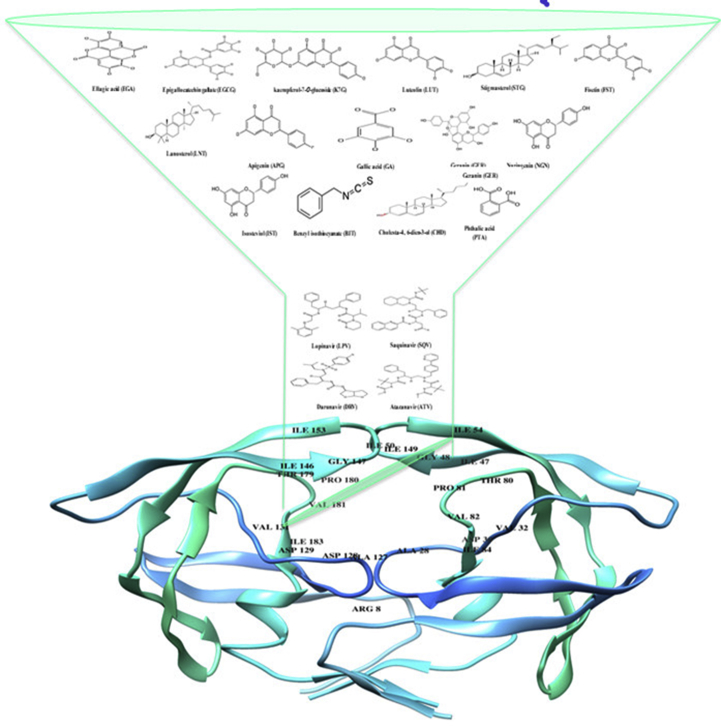

Fig. 1 illustrates the 2-D structures of the selected fifteen phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicineand its constituent plants, 2-D structures of the four FDA-approved protease inhibitor drugs and the crystalline structure of HIV protease enzyme indicating the active site amino acid residues of the enzyme. Three letters code were assigned for the phytochemical compounds and the four FDA-approved drugs.

Fig. 1.

2D Structures of the fifteen selected phytochemical compounds from COA-Fs herbal medicine and its component plants and 2D structures of the Four FDA approved drugs.

2. Methods

2.1. Prediction of enzymes and transporters targets

SWISSTARGETPRIDICTION and SWISSADME servers were used for the prediction of proteins (enzymes and transporters) involved in the metabolism of the Four FDA approved drugs and the selected phytochemical compounds from COA-Fs herbal medicine and its component plants and their pharmacokinetic effects (Gfeller et al., 2014). The server predicts the target of small molecules.

2.2. Measurement of pharmacokinetics properties and drug likeliness of the phytochemical compounds

SWISSADME server was used for the determination of the physicochemical descriptors and define the pharmacokinetic properties and drug-like nature of each phytochemical compound. The “Brain Or Intestinal Estimated permeation, (BOILED-Egg)” method was utilized as it computes the lipophilicity and polarity of small molecules (Daina et al., 2017).

2.3. HIV-1 enzyme and ligand acquisition and preparation

The X-ray crystal structures of the HIV-1 Protease enzyme (PDB codes: 3U71) was obtained from the RSCB Protein Data Bank (Burley et al., 2018). The structures of HIV-1 protease was then prepared on the UCSF Chimera software package (Yang et al., 2012)where the monomeric protein was converted to a dimeric structure. The four FDA-approved drugs Atazanavir, Darunavir, Lopinavir, and Saquinavir, as well as the fifteen phytochemical compounds, were accessed from PubChem (Kim et al., 2016)and the 3-D structures prepared on the Avogadro software package (Hanwell et al., 2012).

2.4. Molecular docking

The Molecular docking software utilized in this study was the Autodock Vina Plugin available on Chimera (Yang et al., 2012), with default docking parameters. Prior to docking, Gasteiger charges were added to the compounds and the non-polar hydrogen atoms were merged to carbon atoms. The phytochemical compounds were then docked into the binding pocket of Protease (by defining the grid box with a spacing of 1 Å and size of 24 × 22 × 22 pointing in x, y and z directions). The four FDA-approved drug systems, as well as the four best-docked phytochemical compounds systems, were then subjected to molecular dynamics simulations.

2.5. Molecular dynamic (MD) simulations

The CPU version of the SANDER engine provided with the AMBER package was used for the MD simulations, and the FF14SB variant of the AMBER force field (Nair and Miners, 2014) was used to describe the protein.

To generate atomic partial charges for the ligand, ANTECHAMBER was used by utilizing the Restrained Electrostatic Potential (RESP) and the General Amber Force Field (GAFF) procedures. The Leap module of AMBER 14 allowed for the addition of hydrogen atoms, as well as Na+ and Cl-counter ions for neutralization all systems. The amino acids were renumbered based on the dimeric form of the enzyme, thus numbering residues 1–198. The 8 systems were then suspended implicitly within an orthorhombic box of TIP3P water molecules such that all atoms were within 8Å of any box edge.

An initial minimization of 2000 steps were carried out with an applied restraint potential of 500 kcal/mol for both solutes, were performed for 1000 steps using the steepest descent method followed by 1000 steps of conjugate gradients. An additional full minimization of 1000 steps were further carried out by conjugate gradient algorithm without restraint.

A gradual heating MD simulation from 0K to 300K was executed for 50ps, such that the systems maintained a fixed number of atoms and fixed volume. The solutes within the systems were imposed with a potential harmonic restraint of 10 kcal/mol and collision frequency of 1.0ps. Following heating, an equilibration estimating 500ps of each system was conducted; the operating temperature was kept constant at 300K. Additional features such as several atoms and pressure were also kept constant mimicking an isobaric-isothermal ensemble (NPT). The system's pressure was maintained at 1 bar using the Berendsen barostat.

The MD simulations was conducted for 100ns. In each simulation, the SHAKE algorithm was employed to constrict the bonds of hydrogen atoms. The step size of each simulation was 2fs and an SPFP precision model was used. The simulations coincided with the isobaric-isothermal ensemble (NPT), with randomized seeding, the constant pressure of 1 bar maintained by the Berendsen barostat, a pressure-coupling constant of 2ps, a temperature of 300K and Langevin thermostat with collision frequency of 1.0ps.

2.6. Post-dynamic analysis

The coordinates of the 8 systems were then saved and the trajectories were analyzed every 1ps using PTRAJ, followed by analysis of RMSD, RMSF and Radius of Gyration using the CPPTRAJ module employed in AMBER 14 suit.

2.7. Binding free energy calculations

To estimate and compare the binding affinity of the systems, the free binding energy was calculated using the Molecular Mechanics/GB Surface Area method (MM/GBSA) (Ylilauri and Pentikäinen, 2013). Binding free energy was averaged over 100000 snapshots extracted from the 100ns trajectory. The free binding energy (ΔG) computed by this method for each molecular species (complex, ligand, and receptor) can be represented as (Hayes and Archontis, 2011):

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

The term Egas denotes the gas-phase energy, which consists of the internal energy Eint; Coulomb energy Eele and the van der Waals energies Evdw. The Egas was directly estimated from the FF14SB force field terms. Solvation free energy, Gsol, was estimated from the energy contribution from the polar states, GGB, and non-polar states, G. The non-polar solvation energy, SA. GSA, was determined from the solvent accessible surface area (SASA), using a water probe radius of 1.4 Å, whereas the polar solvation, GGB, contribution was estimated by solving the GB equation. S and T denote the total entropy of the solute and temperature respectively.

2.8. Data analysis

All raw data plots were generated using the Origin data analysis software (Seifert, 2014).

3. Results

3.1. Assessing the predicted targets for the drugs and phytochemicals

Using two different methods, the SWISSPREDICTION and SWISSADME servers the enzymes and transporters involved in the metabolism of the four FDA-approved drugs and the fifteen selected phytochemical compounds were predicted. The SWISSPREDICTION server predicted all possible enzymes and transporters that are likely to be targets of the phytochemical compounds. On the other hand, the SWISSADME predicted the possibility of the phytochemicals compounds having pharmacokinetic effect on some cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP450) such as CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D9, CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 and their possibility to be substrates (inducers) of Permeability glycoprotein (P-gp). Although, the probability of DRV and SQV binding to Renin as a target was predicted to be low, Renin is the only enzyme predicted by the SWISSPREDICTION server to be target for the four conventional drugs. CYP3A4 with higher probability and cathepsin D (lower probability) were predicted to be targets for DRV, ATV and LPV. Apart from CYP3A4 and P-gp, CYP2C19 was predicted only for LPV. For the selected phytochemical compounds, CYP3A4 was predicted to be target for GER, APG, FST, GA, LUT, and NGN. IST and NGN were only predicted substrates of P-gp. CYPY1A2, CYP2D6, CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 are other sub families of cytochrome P450 enzymes predicted by the SWISSADME server to be targets for EGA, LUT, GER, FST, APG, CHD, NGN, STG, and IST. P-gp and CYP3A4 are the common enzyme and transporter predicted for the four drugs and some of the phytochemical compounds (see Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Predicted targets involved in the metabolism of the four FDA-approved PI drugs and selected phytochemical compounds from COA®-Fs herbal medicine.

| Compound Name | SWISSPREDICTION |

SWISSADME |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymes | Transporters | Enzymes | Transporters | |

| ATV | Renin, Cathepsin D, Pepsin A-5, Cathepsin E, Napsin-A, CYP3A4, Gastricsin | NP | CYP3A4 | P-glycoprotein |

| SQV | Thromboxane-A synthase, Renin, CYP3A4 | D (2), D (4) dopamine receptors, Substance-K receptor, Substance-P receptor, Neuromedin-K receptor, Oxytocin receptor, Mu-type opioid receptor | CYP3A4 | P-glycoprotein |

| LPV | Renin, Cathepsin D, Napsin-A, Beta-secretase 1, Beta-secretase 2, Gastricsin | Potassium voltage-gated (ion channel), | CYP3A4, CYP2C19 | P-glycoprotein |

| DRV | CYPP3A4, Thromboxane-A synthase, CYPP3A5, CYP3A7, CYP3A43, Renin, Cathepsin D | C-C chemokine receptor type 1–8, CX3C chemokine receptor 1, | CYP3A4 | P-glycoprotein |

| EGCG | PEX, 67 kDa matrix metalloproteinase-9, 14, 15, Beta-secretase 1, 2, Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1, 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, decarboxylating, Telomerase reverse transcriptase, Dihydrofolate reductase, Dihydrofolate reductase | Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily H member 2 | NP | NP |

| K7G | Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1, Xanthine dehydrogenase/oxidase, Aldehyde oxidase, Aldo-keto reductase family 1, Aldose reductase, Lysine-specific demethylase 4A, Lysine-specific demethylase 4A, 4B, 4C | Adenosine receptor A1, Alpha-2A, 2C, 2B, Muscle blind-like protein 1 | NP | NP |

| EGA | Cytidine deaminase, Thymidine kinase, Adenosine deaminase, Thymidine phosphorylase, Histone deacetylase 1–3, Adenosyl homocysteinase, Putative adenosyl homocysteinase 2, Carbonic anhydrase 1, 2, 3, 12 | NP | CYP1A2 | NP |

| LUT | 22 kDa interstitial collagenase, CYP1A2, PEX, Stromelysin-1, 67 kDa matrix metalloproteinase-9, Aldose reductase | NP | CYP1A2, CYP2D6, CYP3A4 | NP |

| GER | Squalene monooxygenase, Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1, Muscle blind-like protein 1, Muscle blind-like protein 2 and 3, DNA topoisomerase 1, Tyrosine-protein phosphatase non-receptor type 2 | Multidrug resistance protein 1 (P-glycoprotein) | CYP3A4, CYP2C9 | NP |

| CHD | Androgen receptor, CYPP19A1, Estrogen receptor, Estrogen receptor beta, Oxysterols receptor LXR-beta, Oxysterols receptor LXR-alpha, Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1, Tyrosine-protein phosphatase non-receptor type 1 and 2, M-phase inducer phosphatase 1, Lanosterol 14-alpha demethylase, 3-oxo-5-alpha-steroid 4-dehydrogenase 2 | Sodium-dependent noradrenaline transporter | CYP2C9 | NP |

| APG | Aldo-keto reductase family 1, CYP1A2, Cyclin-dependent kinase 1, Microtubule-associated protein tau, CYP19A1, Cyclin-dependent kinase 4, Estradiol 17-beta-dehydrogenase 1, Aldose reductase, Casein kinase II subunit alpha | Estrogen receptor, Adenosine receptor A2a | CYP1A2, CYP2D6, CYP3A4 | NP |

| FST | Cyclin-dependent kinase 1, Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase, Microtubule-associated protein tau, Cyclin-dependent kinase 4, Arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase, Xanthine dehydrogenase/oxidase | NP | CYP1A2, CYP2D6, CYP3A4 | NP |

| NGN | CYPP450 1A2, CYPP450 19A1, Estradiol 17-beta-dehydrogenase 1, Carbonyl reductase [NADPH] 1, Cytochrome P450 1B1, Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1, CYP1A1, Retinol dehydrogenase 8, Carbonyl reductase [NADPH] 3, Adenosine receptor A1 | Multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (P-glycoprotein), Estrogen receptor | CYP1A2 CYP3A4 | P-glycoprotein |

| BIT | Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1, Microtubule-associated protein tau, Carbonic anhydrase 1–9, Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 and 2, Quinone oxidoreductase, Carbonic anhydrase 5B (mitochondrial), Indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase 1 | Transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily A member 1, Sodium-dependent serotonin transporter | NP | NP |

| GA | Carbonic anhydrase 12, Carbonic anhydrase 1–9, Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1, Carbonic anhydrase 5B and 5A, FAD-linked sulfhydryl oxidase ALR | NP | CYP3A4 | NP |

| STG | Androgen receptor, Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1, CYP19A1, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase, Lanosterol 14-alpha demethylase, Oxysterols receptor LXR-beta, Oxysterols receptor LXR-alpha | Low-density lipoprotein receptor, Very low-density lipoprotein receptor, Estrogen receptor, Estrogen receptor beta, Sodium-dependent noradrenaline transporter | CYP2C9 | NP |

| IST | Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member B10, Aldose reductase, Corticosteroid 11-beta-dehydrogenase isozyme 1, Hydroxysteroid 11-beta-dehydrogenase 1-like protein, M-phase inducer phosphatase 1, M-phase inducer phosphatase 2, Alcohol dehydrogenase [NADP (+)], 1,5-anhydro-D-fructose reductase, UDP-glucuronosyltransferase | NP | CYP2C9 | P-glycoprotein |

| LNT | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase, Lanosterol 14-alpha demethylase, Cytochrome P450 19A1, Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1 | Androgen receptor, Oxysterols receptor LXR-beta, Sodium-dependent noradrenaline transporter, Sodium-dependent serotonin transporter, Sodium-dependent dopamine transporter, Estrogen receptor, Sodium- and chloride-dependent neutral and basic amino acid transporter B (0+) | NP | NP |

| PTA | Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1, Dual specificity tyrosine-phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1A, Microtubule-associated protein tau, Carbonic anhydrase 1, 2, 3, 4, 5A, 5B, 6, 7, 9, 13, Carbonic anhydrase 12, | Gamma-secretase C-terminal fragment 59 | NP | NP |

KEY: NP means Non predicted.

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic effects of phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine on the enzymes and transporter involved in the metabolism of the four FDA-approved PIs.

| Compound Name | Enzymes |

Transporter |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP3A4 Inhibitor | CYP2C19 Inhibitor | P-gp Substrate/inducers | |

| FDA-Approved Drugs | |||

| DRV | Yes | No | Yes |

| LPV | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| ATV | Yes | No | Yes |

| SQV | Yes | No | Yes |

| COA®-FS Phytochemical compounds | |||

| IST | No | No | Yes |

| EGA | No | No | No |

| K7G | No | No | No |

| EGCG | No | No | No |

| NGN | Yes | No | Yes |

| GER | Yes | No | No |

| LNT | No | No | No |

| FST | Yes | No | No |

| LUT | Yes | No | No |

| APG | Yes | No | No |

| PTA | Yes | No | No |

| STG | No | No | No |

| CHD | No | No | No |

| BIT | No | No | No |

| GA | Yes | No | No |

3.2. Pharmacokinetic effects of the phytochemical compounds on the predicted targets involved in the metabolism of the four PI drugs

The SWISSADME server was employed to predict the pharmacokinetic effects of the selected phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine on the Cytochrome P450 enzymes and P-glycoprotein transporter involved in the metabolism of the four FDA-approved drugs. The result revealed that the PI drugs showed inhibitory activities on CYP3A4. LPV was also predicted to inhibit CYP2C19. The four drugs were predicted inducers of P-gp, as only IST and NGN were predicted inducers of P-gp. Seven of the phytochemical compounds were predicted to possess inhibitory activity on CYP3A4 and none of the phytochemical compound was predicted to inhibit CYP2C19. The inhibition of CYP3A4 and P-gp by the phytochemical compound could decrease the elimination and pumping out of the four PI drugs from the systemic circulation and the cells respectively.

3.3. Assessing the drug-likeness of phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine

As shown in Table 4, three of the FDA-approved drugs (ATV, SQV and LPV) with three of the selected phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine (CHD, STG and NGN) are poorly soluble in water. This may lower the bio availabilities of the three PI drugs and the three phytochemical compounds. The result also showed the drug likeness of the four FDA-approved drugs and the fifteen selected phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine, two of the four conventional drugs pass the drug likeness test (DRV and LPV) and Nine of the phytochemical compounds (K7G, EGA, LUT, APG, FST, BIT, GA, IST and NGN) pass the test. These showed that the nine phytochemical compounds have good drug properties as the two conventional drugs.

Table 4.

Predicted ADME parameters, drug-likeness, pharmacokinetic and physicochemical properties of phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine and four FDA-approved drugsusing SWISSADME server.

| Compound Name |

Molecular Formula | Molecular Weight (g/mol) | Lipophilicity (iLOGP) | Water Solubility | GIT Absorption | BBB Permeability | Bioavailability Score |

Synthetic Accessibility | Drug likeness (Lipinski) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATV | C38H52N6O7 | 704.869 | 3.56 | Poor | Low | No | 0.17 | 6.24 | No (2) |

| SQV | C38H50N6O5 | 670.855 | 3.66 | Poor | Low | No | 0.17 | 5.94 | No (2) |

| LPV | C74H96N10O10S2 | 1349.762 | 3.44 | Poor | High | No | 0.55 | 5.67 | Yes |

| DRV | C27H37N3O7S | 547.667 | 3.20 | Moderate | Low | No | 0.55 | 5.67 | Yes |

| EGCG | C22H18O11 | 458.37 | 1.83 | High | Low | No | 0.17 | 4.20 | No (2) |

| K7G | C21H20O11 | 448.38 | 1.55 | High | Low | No | 0.17 | 5.24 | No (2) |

| EGA | C14H6O8 | 302.19 | 0.79 | High | High | No | 0.55 | 3.17 | Yes |

| LUT | C15H10O6 | 286.24 | 1.86 | High | High | No | 0.55 | 3.02 | Yes |

| GER | C30H24O10 | 544.51 | 2.14 | Moderate | Low | No | 0.17 | 5.73 | No (2) |

| CHD | C27H440 | 384.64 | 4.81 | Poor | Low | No | 0.55 | 6.29 | No (3) |

| APG | C15H10O5 | 270.24 | 1.89 | Moderate | High | No | 0.55 | 2.96 | Yes |

| FST | C15H10O6 | 286.24 | 1.50 | High | High | No | 0.55 | 3.16 | Yes |

| LNT | C30H50O | 426.72 | 5.09 | Poor | Low | No | 0.55 | 6.07 | No (3) |

| BIT | C8H7NS | 149.21 | 2.19 | High | High | Yes | 0.55 | 1.59 | Yes |

| GA | C7H6O5 | 170.12 | 0.21 | High | High | No | 0.56 | 1.22 | Yes |

| IST | C20H30O3 | 318.45 | 2.27 | Moderate | High | Yes | 0.56 | 4.83 | Yes |

| STG | C29H480 | 412.69 | 4.96 | Poor | Low | No | 0.55 | 6.21 | No (3) |

| NGN | C15H12O5 | 27.2.25 | 1.75 | Soluble | High | No | 0.55 | 3.01 | Yes |

| PTA | C8H6O4 | 166.13 | 0.60 | Soluble | High | No | 0.56 | 1.00 | No (2) |

3.4. Binding affinity of the phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine to HIVpro

Fifteen phytochemicals from COA®-FS herbal medicine, its component plants and four FDA-approved protease inhibitor drugs (PIs) were docked with HIVpro to estimate the affinity of the drugs to the enzyme in comparison to the four known PIs (Table 5). The docking score showed the fitness of the ligands into the active site pocket of the enzyme and the more negative the value the better the fitness of the ligand. In term of the docking score, all the PIs are better than the phytochemical compounds except EGA and K7G which are better than LPV. The docking scores for the four FDA-approved PIs range from -8.1 to -9.2 kcal/mol, while Ellagic acid and Kaempferol-7-O-glucoside showed the highest docking scores among the fifteen phytochemical compounds and the scores fall within the range of the docking score for the four FDA approved PI drugs. The binding conformation of the fifteen phytochemical compounds (ligands) and the four FDA-approved drugs were taken for further molecular dynamics and binding energy calculations.

Table 5.

Docking scores for the four FDA-approved PI drugs and phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine.

| Compounds Name | Docking score (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| FDA Approved Drugs | |

| SQV | -9.8 |

| DRV | -9.2 |

| ATV | -8.7 |

| LPV | -8.1 |

| COA-FS Phytochemical compounds | |

| EGA | -8.3 |

| K7G | -8.1 |

| EGCG | -7.5 |

| STG | -7.5 |

| GER | -7.5 |

| NGN | -7.5 |

| CHD | -7.4 |

| LNT | -7.4 |

| FST | -7.3 |

| LUT | -7.3 |

| APG | -7.2 |

| IST | -7.1 |

| PTA | -4.8 |

| BIT | -4.6 |

| GA | -4.5 |

3.5. Thermodynamic binding free energy of phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine to HIVpro

As molecular docking only measures the geometric fit of ligands at the active site of a protein, molecular dynamics simulations were run for 100ns to assess the binding free energy of each system. The more negative the values, the better the binding free energy between the enzyme (HIVpro) and the ligands. The binding free energy of the four FDA-approved drugs and the fifteen phytochemical compounds were determined using the MMGBSA method to estimate the interaction strength between the FDA-approved inhibitors in comparison to the COA®-FS herbal medicine phytochemical compounds (Table 6). ATV showed the highest binding energy than the remaining three conventional PIs and the fifteen selected phytochemical compounds. However, EGCG had better energy than three conventional PIs (DRV, LPV and SQV). In addition, K7G is better than LPV and DRV.

Table 6.

Thermodynamic binding free energy for Phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicineand FDA-approved drugs to HIVpro.

| Energy Components (kcal/mol) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complex | Δ EvdW | ΔEelec | ΔGgas | ΔGsolv | ΔGbind |

| FDA-Approved Drugs | |||||

| SQV | -59.300 ± 5.140 | 6.139 ± 4.847 | -53.161 ± 19.400 | -0.514 ± 1.35 | -53.979 ± 4.874 |

| DRV | -43.805 ± 6.108 | -25.424 ± 8.120 | -69.223 ± 10.871 | 29.235 ± 4.206 | -35.311 ± 4.943 |

| ATV | -65.905 ± 4.965 | -28.758 ± 5.760 | -94.664 ± 8.314 | 37.824 ± 4.796 | -56.839 ± 5.292 |

| LPV | -51.973 ± 5.433 | -27.534 ± 6.605 | -79.507 ± 7.958 | 38.291 ± 3.540 | -44.571 ± 3.952 |

| COA®-FS herbal medicine Phytochemical compounds | |||||

| EGCG | -36.589 ± 4.054 | -76.679 ± 10.634 | -113.26 ± 10.265 | 61.364 ± 3.586 | -55.954 ± 2.705 |

| K7G | -45.850 ± 4.123 | -44.778 ± 9.576 | -90.628 ± 8.503 | 48.269 ± 5.467 | -45.740 ± 4.288 |

| EGA | -25.883 ± 3.400 | -57.201 ± 6.132 | -83.084 ± 5.446 | 46.585 ± 3.653 | -38.500 ± 2.101 |

| LUT | -26.604 ± 3.702 | -48.553 ± 7.929 | -75.157 ± 6.895 | 41.611 ± 4.879 | -37.487 ± 1.223 |

| GER | -46.385 ± 4.820 | -17.375 ± 5.847 | -63.759 ± 7.842 | 29.458 ± 4.423 | -35.532 ± 2.510 |

| LNT | -34.047 ± 5.941 | -11.624 ± 2.458 | -45.669 ± 6.293 | 18.170 ± 3.523 | -27.486 ± 3.599 |

| APG | -31.671 ± 8.375 | -16.449 ± 2.766 | -48.112 ± 11.223 | 22.104 ± 4.239 | -26.017 ± 2.966 |

| NGN | -21.952 ± 3.673 | -36.188 ± 8.717 | -58.140 ± 9.018 | 35.379 ± 5.518 | -22.761 ± 4.494 |

| STG | -20.604 ± 4.023 | 20.222 ± 4.907 | -0.373 ± 1.485 | -19.216 ± 4.776 | -19.584 ± 5.041 |

| BIT | -18.433 ± 3.600 | -264.05 ± 22.483 | -225.00 ± 14.578 | 206.99 ± 17.374 | -18.014 ± 3.083 |

| GA | -18.545 ± 6.221 | -252.39 ± 13.425 | -213.60 ± 20.032 | 195.98 ± 19.394 | -17.622 ± 2.094 |

| IST | -18.825 ± 3.748 | -254.24 ± 4.827 | -215.62 ± 12.739 | 198.31 ± 9.202 | -17.315 ± 2.650 |

| CHD | -18.52 ± 3.777 | -245.58 ± 10.393 | -206.69 ± 11.342 | 189.51 ± 9.342 | -17.184 ± 2.417 |

| FST | -17.65 ± 4.034 | -254.16 ± 14.288 | -213.67 ± 8.384 | 198.16 ± 7.323 | -15.516 ± 3.993 |

| PTA | -21.145 ± 2.327 | -17.168 ± 3.602 | -38.312 ± 3.942 | 23.679 ± 2.555 | -14.633 ± 2.248 |

3.6. Structural analysis of the most optimal Phytochemical-HIVpro complexes

To further establish the mechanistic inhibitory characteristics of these four selected phytochemical compounds (EGCG, K7G, EGA and LUT) with antiviral activity against HIVpro. Root mean square deviation (RMSD), Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), Radius of gyration (RoG) and ligand interaction plots were assessed.

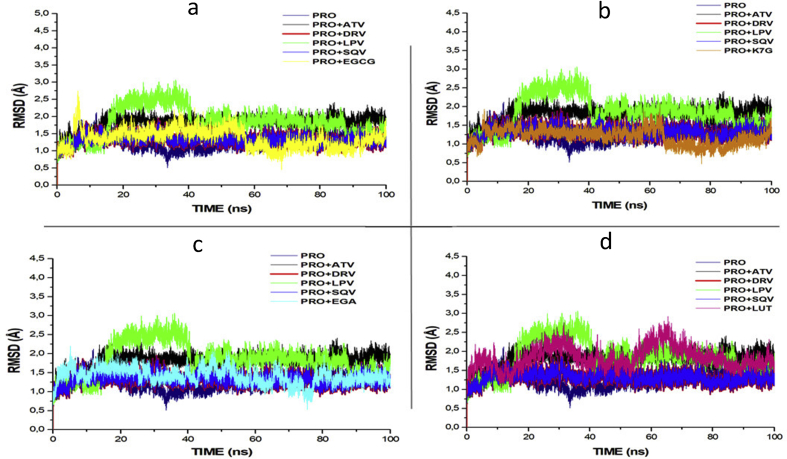

Fig. 2 depicts the RMSD plot for the four phytochemical compounds and the four FDA-approved drugs. RMSD measures protein stability as the simulation progresses. The RMSD plots of K7G,EGA and EGCG with average values of 1.432Å, 1.442Å and 1.465Å respectively are similar to the RMSD of ATV (1.511 Å), DRV (1.451Å), SQV (1.402Å), apo-enzyme, 1.342Å (protease enzyme without ligand). RMSD of EGCG seems to slightly close to the RMSD of LPV (1.9189Å). The RMSD of K7G (1.351Å) showed the same similarity with RMSD of SQV (1.345 Å). The RMSD of the four compounds deviates from the RMSD of LPV with the highest average value of 2.187Å. The first 40ns of simulation of LPV showed the instability of the enzyme, but from 40 to 100ns of simulation the enzyme was stable.

Fig. 2.

RMSD profile of protein backbone atoms of PRO, ATV, DRV and SQV with (a) EGCG (b) K7G (c) EGA and (d) LUT calculated over the course of 100 ns molecular dynamics of HIVpro bound to the four different ligands and FDA-approved PI drugs.

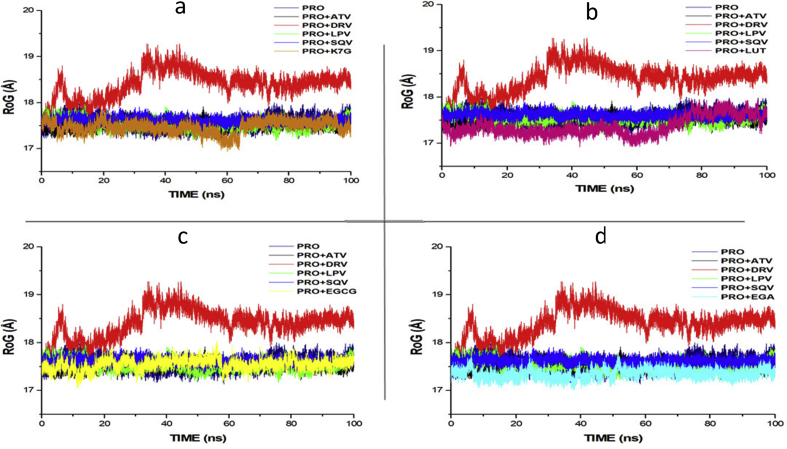

Figs. 3 and 4 showed the Radius of Gyration (RoG) and Root mean square fluctuations values over the course of 100ns of simulations of the HIV-1 protease enzymes bound to different ligands. RoG is a measure of the compactness of the protein structure. The RoG values of each of the compound were compared to the RoG of the four FDA approved drugs (Fig. 3). RoG of EGCG (17.544 Å), LUT (17.431Å), EGA (17.354Å) and K7G (17.455 Å) shows similarity with the RoG of LPV (17.411 Å), ATV (17.327 Å) and SQV (17.423 Å) but deviated from the RoG of DRV (18.345 Å). None of the four compounds showed the same trend and values with RoG of DRV (18.345 Å).

Fig. 3.

RoG profile of protein backbone atoms of PRO, ATV, DRV and SQV with (a) K7G (b) LUT (c) EGCG and (d) EGA calculated over the course of 100 ns molecular dynamics of HIVpro bound to different ligands and drugs.

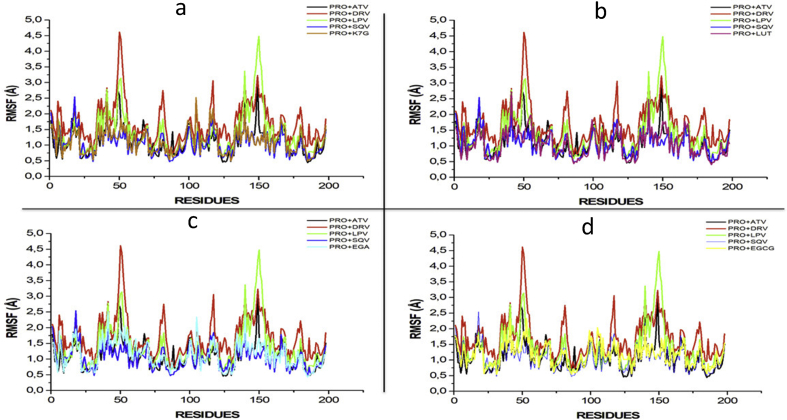

Fig. 4.

RMSF profile of protein backbone atoms of PRO, ATV, DRV and SQV with (a) K7G (b) LUT (c) EGA and (d) EGCG calculated over the course of 100 ns molecular dynamics of HIVpro bound to four different ligands and FDA-approved drugs.

RMSF values monitor the fluctuation of each amino residue as they interact with the ligand throughout a trajectory. The RMSF values of each of the four phytochemical compounds were compared to the RMSF of the four FDA-approved drugs (Fig. 4).

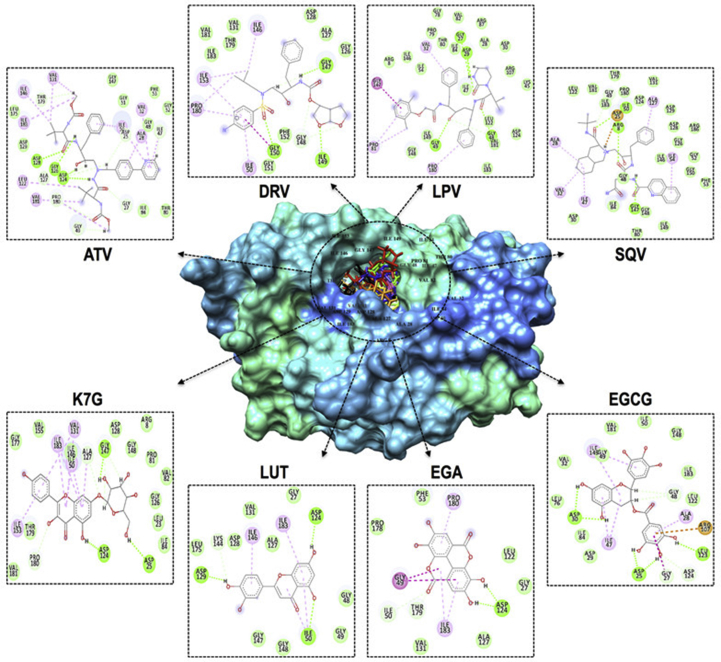

Fig. 5 illustrates the ligand-interaction plots of the above-mentioned systems following the 100 ns trajectory. The type and number of interactions between proteins and ligands are the major determinants of the overall binding free energy.

Fig. 5.

Representation of ligand-HIVpro interactions with different amino acid residues.

4. Discussion

4.1. Assessing the predicted targets for the drugs and phytochemical compounds

The result of this study showed the predicted targets for the four conventional drugs and the phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine. Cytochrome P450 3A4 and CYP2C19, two sub families of cytochrome P450 enzymes were predicted to be involved in the metabolism of the four FDA-approved drugs. CYP3A4 was the predicted common target for the four conventional drugs, but LPV was additionally predicted to be inhibitor of CYP2C19. This prediction is in agreement with the report of Brian et al. and Vaishali et al. that reported CYP3A4 is the major form of cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the metabolism of HIV protease inhibitor drugs (Brian et al., 2011; Vaishali et al., 2007). All the four FDA-approved drugs were as well predicted to be substrates of Permeability glycoprotein (P-gp), this validate the report of Griffin et al. that reported that P-gp was actively involved in the metabolism of PI drugs (Griffin et al., 2011). A different sub type of cytochrome P450 were predicted targets for the phytochemical compounds. Cytochrome P450 1A2 (CYP 450 1A2) was predicted for EGA, FST, NGN, LUT and APG, while CYP 450 2D6 was predicted target for FST, APG and LUT. CYP3A4 and multi-drug resistant protein (P-gp) are the commonly predicted targets for the FDA-approved drug and the phytochemicals.

4.2. Pharmacokinetic effects of the phytochemical compounds on the predicted targets involved in the metabolism of the four PI drugs

The SWISSTARGETPREDICTION and SWISSADME servers predicted many enzymes and transporters as targets for the four drugs based on structures of the drugs and physiological conditions. The SWISSADME server prediction for the four drugs validated studies that reported CYP3A4 and P-gp are the major enzyme and transporter involved in the metabolism of the PI drugs (Huisman et al., 2001; Sanjay et al., 2004, Walubo, 2007). Several studies have also shown that both CYP3A4 and P-gp have a wide and overlapping substrate specificity (Konig et al., 2013, Fromm, 2004), as this explained why the four PI drugs are both inhibitors and inducers of CYP3A4 and P-gp respectively. The pharmacokinetic effect of the phytochemicals on CYP3A and P-gp revealed that NGN, GER, FST, LUT, APG, PTA and GA are inhibitors of CYP 3A4. Inhibition of CYP3A4 has been reported to decrease the rate of elimination of drugs from the systemic circulation thereby increasing bioavailability of drugs (Liyue et al., 2001). The phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine predicted to be inhibitors of CYP3A4, when used concurrently with PI drugs could increase the bioavailability of the four FDA-approved PI drugs and enhance them to maximally exert their pharmacological effects. NGN and IST were predicted inducers of P-gp and could increase the rate of elimination of the four drugs thereby lowering PI drugs bioavailability (Richard et al., 2014). Other phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine were predicted to be non-inducers of P-gp and could inhibit the activity of P-gp to increase PI drugs bioavailability.

The result of this study revealed phytochemical compounds fromCOA®-FS herbal medicine and its constituent plants are predicted inhibitors of CYP3A and P-gp, and they could increase the bioavailability of PI drugs in the plasma drug, resulting to the drug being slowly eliminated from the systemic circulation and exerting their therapeutic antiviral effects.

4.3. Assessing the drug-likeness of phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine

One of the important rules in drug design is Lipinski's rule, it is a set of five rules use to assess the drug-likeness of a compound with pharmacological or biological activities with the aim of examining if it possess both physical and chemical properties to act as an orally active drug in humans (Lipinski, 2004; Lipinski et al., 2012). The rule centred on the number of hydrogen bond donors in the compound (not more than 5), a few hydrogen bond acceptor (not more than 10), molecular mass less than 500 daltons and partition coefficient (logP) not greater than 5. The result showed two of the conventional drugs (LPV and DRV) and eight of the phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine (EGA, LUT, APG, FST, BIT, GA, IST and NGN) were predicted to pass the rules. This indicate that the eight phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine possess the same chemical and physical properties with two of the FDA-approved drugs (LPV and DRV). ATV and DRV, the conventional drugs together with seven of the compounds failed a maximum of three out of the rules.

Gastrointestinal (GIT) absorption is significant for the maintenance of optimal drug levels in the systemic circulation. For drugs or potential compounds to reach their target, they must be absorbed from the GIT and enter the systemic circulation in enough amount or quantities (Kremers, 2002). Highly absorbed drugs from the GIT will easily attain optimal concentration and exert a pharmacological effect at its target site. LPV is the only drug out of the four conventional drugs that has high GIT absorption, while the remaining drugs' absorptions in GIT are low. Nine out of the fifteen phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine were predicted to be highly absorbed from the GIT (EGA, LUT, APG, FST, BIT, GA, IST, NGN, and PTA) and could eventually attain the required concentration needed for therapeutic effects.

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a protection developed by the endothelial cells that line cerebral microvessels (Abbott, 2002; Begley and Brightman, 2011) and drugs or compounds that are not soluble in lipid with molecular weight greater than 400 Dalton cannot go across the BBB but smaller and lipophilic molecules can go across the BBB (Begley and Brightman, 2011). Therefore, BBB permeability parameter is always considered in the development of a drug for neuro-degenerated and related diseases. None of the four FDA-approved conventional drugs was predicted to permeate the BBB and only two of the phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine (BIT and IST) were predicted to go across the BBB.

Drug bioavailability is a measurement of the degree of absorption and fraction of a given amount of unchanged drug that goes to the systemic circulation (Heaney, 2018). Orally and intravenously administered drug have different bioavailability as a result of some factors like first pass-drug metabolism. It is a significant pharmacokinetic property of the drug that must be carefully thought of when calculating drug dosages. Higher bioavailability score is required for a drug to reach a higher and optimal concentration in the systemic circulation and to exert notable pharmacological response. When compared with the four conventional drugs, ATV and SQV have low and the same bioavailability scores of 0.17 with EGCG, GER and K7G. Slightly higher bioavailability scores of 0.55 were predicted for LPV and DRV, and the other phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine.

4.4. Thermodynamic binding free energy of phytochemical compounds to HIVpro

The binding free energy calculated for the four conventional drugs ranges from -35.311 ± 4.943 to -56.056 ± 4.978 kcal/mol, with Atazanavir (ATV) and Darunavir having the highest and the lowest values respectively. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), Kaempferol-7-O-glucoside (K7G), Ellagic acid (EGA) and Luteolin (LUT)indicated the most optimal binding when compared to the FDA approved drugs. It was also interesting to note that although compounds FST, APG and NGN demonstrated relatively high docking scores, binding free energy calculations for these systems indicated dissimilar results. This validates the need for molecular dynamics simulations, which may allow for a compound to become “comfortable” within an enzyme's binding site. To further establish the mechanistic inhibitory characteristics of the best four phytochemical compounds (EGCG, K7G, EGA and LUT) with higher free binding energy, RMSD, RoG, RMSF, and ligand interaction plots were assessed.

4.5. Structural analysis of the most optimal phytochemical compound-HIVpro complexes

The structural stability of a protein complex was measured following experimental simulation of the phytochemical compounds together with the protein. Root mean square deviation (RMSD) and root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) were studied in several molecular dynamics studies to study conformational stability of ligands and proteins (Agoni et al., 2018; Mcgillewie and Soliman, 2015; Munsamy et al., 2018; Ramharack et al., 2017). The deviation produced by a protein during stimulation is a factor determining its stability, and the lower the deviation produced the more stable the protein. Therefore, RMSD, which measures protein stability as the simulation progresses, can be used to determine protein stability. In this study, RMSD values for the C-alpha atoms of the structures were determined. The RMSD values of the HIVpro-ligands (four FDA approved drugs and four compounds with highest binding energies) complexes are shown in Fig. 2.

The RMSD of each phytochemical compound was compared to the RMSD values of the four FDA approved drugs. The RMSD plots of three phytochemical compounds (EGCG, EGA and K7G) are like the RMSD values of the of the FDA-approved drugs (ATV, SQV and DRV) and apo-enzyme. This indicates the same enzyme stability was seen between the three phytochemical compounds and three of the FDA-approved drugs and the apo-enzyme (positive control). The RMSD value of the LUT (1.843Å) is slightly similar to that of LPV (2.187).

The values of the radius of gyration (RoG) were also plotted for each system. RoG is a measure of the compactness of the protein structure. The RoG values of each of the phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine were compared to the RoG of the four FDA approved drugs and the apo-enzyme (Fig. 3). The four phytochemical compounds shows similarity with the RoG of three of the FDA-approved protease inhibitor drugs (LPV, SQV and ATV) and the apo-enzyme but deviated from the RoG of value of DRV (18.345 Å). Like the RMSD values, none of the four phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine showed the same trend and values with RoG of DRV (18.345 Å).

The RMSF values monitor the fluctuation of each amino residue as they interact with the ligand throughout the trajectory. The RMSF values of each of the compound were compared to the RMSF of the four FDA approved drugs (Fig. 4). Based on the RMSF results, it was evident that the DRV (1.694) and LPV (1.380)systems demonstrated highest fluctuations, particularly at residues 50, 80, 115–120 and 130–155. The K7G (1.130) system showed the greatest similarity to the four FDA-approved drugs, with fluctuations occurring with similar residues. With this being said, fluctuations at 45–55 and 145–155 are mirror residues in dimeric form. This substantiates the necessity of the dimeric activity of the HIV-protease (Hayashi et al., 2014).

4.6. Ligand-HIVpro interactions with different amino acid residues

As mentioned above, ATV at the HIVpro binding led to the highest free binding energy of the 19 systems. These results may be attributed to the greater number of hydrogen bond interactions produced between the drug and HIVpro amino acid residues (ASP128, GLY126, ASP124, THR179, ALA127, PRO180, GLY49, GLY27, ASP25, and ILE47). The hydrogen bond interactions for SQV, LPV, and DRV are 4, 5 and 4 respectively. A Salt-bridge interaction at amino residue ASP25, together with numerous van der Waals, alkyl, and Pi-alkyl interactions contributed to the SQV-system gaining second highest binding energy. With 20 van der Waals interactions and 5 hydrogen bond interactions, LPV showed higher binding energy than DRV. Of the phytochemical compounds, EGCG demonstrated the highest binding energy. This may have been the result of salt-bridge interaction at ARG107, 6 hydrogen bond interactions, 13 van der Waals and 3 Pi-alkyl interactions. It was interesting to note that the “two-component” salt-bridges, made up of a hydrogen bond and electrostatic interaction, were only recorded within the EGCG and SQV systems. This could have led to the overall binding energy of EGCG higher than K7G, despite K7G having a higher overall number of interactions. EGA and LUT possess 3 and 4 hydrogen bond, 6 and 8 van der Waals, and 2 each of Pi-alkyl interactions respectively.

5. Conclusion

The predictive analysis predicted several enzymes and transporters as targets for the four FDA-approved drugs and the phytochemical compounds but CYP3A4 enzyme and P-gp transporters are majorly involved in the metabolism of PI drugs. The analysis also predicted both inhibitors and inducers of CYP3A4 and P-gp among the phytochemical compounds from COA®-FS herbal medicine and its component plants. The phytochemical compounds predicted to be inhibitors of CYP3A4 and P-gp could increase the bioavailability of the four FDA-approved drugs in the systemic circulation thereby enhancing the four drugs to exert maximum pharmacological effects. The Fifteen selected phytochemical compounds from COA-FS herbal medicine and its component plants were subjected to docking studies with HIVpro to recognize the best natural potential inhibitors as compared to the four FDA-approved HIVpro inhibitor drugs in term of binding free energy/affinity. Of all the docked selected phytochemical compounds, EGCG, K7G, EGA, NGN, STG, GER, and LUT gave the best binding score when compared to the four conventional drugs. Molecular dynamics and MMGBSA analysis were done on all the fifteen compounds and the drugs. The results of the MD simulations and MMGBSA showed that only EGCG, K7G, EGA and LUT fit well into the HIVpro active site pocket with better binding free energy. The study implied that the ligands interacted hydrophobically with the active amino residues. This study also identified some of the key residues that are helpful in dual inhibitor design. The EGCG and k7G compounds proved to be more potent inhibitors of HIVpro. Therefore, this study showed that some of the phytochemical compounds could be utilised to enhance therapeutic effect of the four FDA-approved drugs and, could as well serve as natural inhibitors of HIVpro and be used as important standard in developing novel drugs to inhibit the activity of HIVpro.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Idowu Kehinde, Pritika Ramharack: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Manimbulu Nlooto, Michelle Gordon: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal Scholarship.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Contributor Information

Idowu Kehinde, Email: 218068180@stu.ukzn.ac.za.

Manimbulu Nlooto, Email: 218068180@stu.ukzn.ac.za.

References

- Abbott N.J. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions and blood-brain barrier permeability. J. Anat. 2002;200(6):629–638. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00064.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adewole E., Ojo A., Ogunmodede O.T., Adewumi D.F., Omoaghe A.O., Jamshed I. 2018. Characterization and Evaluation of Vernonia Amygdalina Extracts for its Antidiabetic Potentials. [Google Scholar]

- Agoni C., Ramharack P., Soliman M.E.S. Co-inhibition as a strategic therapeutic approach to overcome rifampin resistance in tuberculosis therapy: atomistic insights. Future Med. Chem. 2018;10(14):1665–1675. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2017-0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babatunde D.E., Otusemade G.O., Efeovbokhan V.E., Ojewumi M.E., Bolade O.P., Owoeye T.F. 2019. PT. Chemical Data Collections. 100208. [Google Scholar]

- Begley D.J., Brightman M.W. Structural and functional aspects of the blood-brain barrier. Pept. Transp. Deliv. Cent. Nerv. Syst. 2011;61(5):39–78. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-8049-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boadu A. University of KwaZulu-Natal; Durban, South Africa: 2019. A Comparative Chemistry of COA Herbal Medicine and Herbal Extracts of Veronia mygdalina (Bitter Leaf) and Persea americana (Avocado) unpublished thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Brian J., Kirby A.C., Collier E.D., Kharasch V., Dixit P.D., Whittington K.T., Jashvant D.U. Complex drug interactions of HIV Protease inhibitors 2: in vivo induction and in vitro to in vivo correlation of induction of cytochrome P450 1A2, 2B6, and 2C9 by ritonavir or nelfinavir. Drug. Metab. Dispos. 2011;39(12):2329–2337. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.038646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brik A., Wong C.H. HIV-1 protease: mechanism and drug discovery. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2003;1(1):5–14. doi: 10.1039/b208248a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burley S.K., Berman H.M., Christie C., Duarte J.M., Feng Z., Westbrook J. RCSB Protein Data Bank: sustaining a living digital data resource that enables breakthroughs in scientific research and biomedical education. Protein Sci. 2018;27(1):316–330. doi: 10.1002/pro.3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Oliver M., Medina-Campos O.N., Ponce-Alquicira E., Pedroza-Islas R., Pedraza-Chaverri J., Escalona-Buendía H.B. Optimization of the antioxidant and antimicrobial response of the combined effect of nisin and avocado byproducts. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2015;65:46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona S., Nash J. Adult antiretroviral therapy guidelines 2017 as per HIV Medicine. SAJ. 2017;18(1):1–24. doi: 10.4102/sajhivmed.v18i1.776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daina A., Michielin O., Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dineshkumar I.A.G., Rajakumar R. GC-MS Evaluation of bioactive molecules from the methanolic leaf extract of Azadirachta indica (A. JUSS) Asian J. Pharmaceut. Sci. Technol. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Fromm M.F. Importance of P-glycoprotein at blood-tissue barriers. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2004;2004(25):424–429. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geretti A.M., Easterbrook P. Antiretroviral resistance in clinical practice. Int. J. STD AIDS. 2001;12(3):15–153. doi: 10.1258/0956462011916938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gfeller D. Swiss target prediction: a web server for target prediction of bioactive small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:W32–W38. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanwell M.D., Curtis D.E., Lonie D.C., Vandermeerschd T., Zurek E., Hutchison G.R. Avogadro: an advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J. Cheminf. 2012;4(8):1–17. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi H., Takamune N., Nirasawa T., Aoki M., Morishita Y., Das D. Dimerization of HIV-1 protease occurs through two steps relating to the mechanism of protease dimerization inhibition by darunavir. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014;111(33):12234–12239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400027111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes J.M., Archontis G. 2011. Molecular Dynamic-Studies of Synthetic and Biological Molecules; p. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Heaney R.P. Factors influencing the measurement of bioavailability, taking calcium as a model. J. Nutr. 2018;131(4):1344S–1348S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.4.1344S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huisman M.T., Smit H.R., Wiltshire R.M., Hoetelmans J.H., Beijnen, Schinkel A.H. P-glycoprotein limits oral availability, brain, and fetal penetration of saquinavir even with high doses of ritonavir. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001;59:806–813. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.4.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado-Fernández E., Pacchiarotta T., Mayboroda O.A., Fernández-Gutiérrez A., Carrasco-Pancorbo A. Quantitative characterization of important metabolites of avocado fruit by gas chromatography coupled to different detectors (APCI-TOF MS and FID) Food Res. Int. 2014;62:801–811. [Google Scholar]

- Igile G.O., Oleszek W., Burda S., Jurzysta M. Nutritional assessment of Vernonia amygdalina leaves in growing mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1995;43(8):2162–2166. [Google Scholar]

- Kermanshai R., McCarry B.E., Rosenfeld J., Summers P.S., Weretilnyk E.A., Sorger G.J. Benzyl isothiocyanate is the chief or sole anthelmintic in papaya seed extracts. Phytochemistry. 2001;57(3):427–435. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(01)00077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Thiessen P.A., Bolton E.E., Chen J., Fu G., Gindulyte A. PubChem substance and compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(1):1202–1213. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kongkachuichai R., Charoensiri R.I.N. Carotenoid , flavonoid pro fi les and dietary fi ber contents of fruits commonly consumed in Thailand. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010;61(August):536–548. doi: 10.3109/09637481003677308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konig J., Muller F., Fromm M.F. Transporters and drug-drug interactions: Important determinants of drug disposition and effects. Pharmacol Rev. 2013;65:944–966. doi: 10.1124/pr.113.007518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremers P. In vitro tests for predicting drug-drug interactions: the need for validated procedures. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2002;91(5):209–217. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2002.910501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lako J. Phytochemical flavonols , carotenoids and the antioxidant properties of a wide selection of Fijian fruit, vegetables and other readily available foods. Food Chem. 2007;101:1727–1741. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin LaToya, Annaert Pieter, Brouwer Kim. Influence of drug transport proteins on pharmacokinetics and drug interactions of HIV protease inhibitors. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011;100(9):3636–3654. doi: 10.1002/jps.22655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy Y., Caflisch A. Flexibility of monomeric and dimeric HIV-1 protease. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2003;107(13):3068–3079. [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski C.A. Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2004;1(4):337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski C.A., Lombardo F., Dominy B.W., Feeney P.J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012;64 doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liyue H., Stephen A., Wring J.L., Woolley K.R., Brouwer C., Serabjit-Singh, Joseph W.P. Induction of p-glycoprotein and cytochrome p450 3a by hiv protease inhibitors. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2001;29(5):755–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcgillewie L., Soliman M.E. Flap flexibility amongst I, II, III, IV, and V: sequence, structural, and molecular dynamic analyses. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 2015;83(9):1693–1705. doi: 10.1002/prot.24855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monika P., Geetha A. 2015. PT US CR. Phytomedicine. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhtar M., Arshad M., Ahmad M., Pomerantz R.J., Wigdahl B., Parveen Z. Antiviral potentials of medicinal plants. Virus Res. 2008;131:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munsamy G., Ramharack P., Soliman M.E.S. Egress and invasion machinary of malaria: an in depth look into the structural and functional features of the flap dynamics of plasmepsin IX and X. RSC Adv. 2018;8:21829–21840. doi: 10.1039/c8ra04360d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair P.C., Miners J.O. Molecular dynamics simulations: from structure function relationships to drug discovery. Silico Pharmacol. 2014;2(4):1–4. doi: 10.1186/s40203-014-0004-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nlooto M., Naidoo P. Clinical relevance and use of traditional , complementary and alternative medicines for the management of HIV infection in local African communities , 1989 - 2014 : a review of selected literature. Pula: Botsw. J. Afr. Stud. 2014;28(1):105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Nwabuife J.C. University of KwaZulu-Natal; Durban, South Africa: 2019. A Comparative Chemistry of COA Herbal Medicine and Herbal Extracts of Azadirachta indica and Carica papaya. unpublished thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Ramharack P., Oguntade S., Soliman M.E.S. Delving into Zika virus structural dynamics – a closer look at NS3 helicase loop flexibility and its role in drug discovery. RSC Adv. 2017;7(36):22133–22144. [Google Scholar]

- Rashed K., Luo M.-T., Zhang L.-T., Zheng Y.-T. Phytochemical screening of the polar extracts of Carica papaya Linn . and the evaluation of their anti-Hiv-1 activity. J. Appl. Ind. Sci. 2013;1(3):49–53. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Phytochemical-Screening-of-the-Polar-Extracts-of-.-Rashed-Luo/445b4726079362a4960c3cecdec7aeee5904f7bc Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Richard C., Frederick L., Mary B. Inhibition of the multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein: Time for a change of strategy. Drug. Metab. Dispos. 2014;42:623–631. doi: 10.1124/dmd.113.056176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajin A.K., Rathnan R.K., Mechoor A. Molecular docking studies on phytocompounds from the methanol leaf extract of Carica papaya against Envelope protein of dengue virus ( type-2 ) J. Comput. Methods Mol. Des. 2015;5(2):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Sanjay U.C., Sankatsing J.H., Beijnen A.H., Schinkel Joep M.A.L., Jan M.P. P Glycoprotein in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection and therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48(4):1073–1081. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.4.1073-1081.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholar E. 2011. HIV Protease inhibitors. XPharm: the Comprehensive Pharmacology Reference; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Seifert E. OriginPro 9.1: scientific data analysis and graphing software-software review. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014;54(5) doi: 10.1021/ci500161d. 1552–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin M.S., Kang E.H., Lee Y.I. A flavonoid from medicinal plants blocks hepatitis B virus-e antigen secretion in HBV-infected hepatocytes. Antivir. Res. 2005;67(3):163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui B.S., Afshan F., Arfeen S.S., Gulzar T. A new tetracyclic triterpenoid from the leaves of Azadirachta indica. Nat. Prod. Res. 2006;20(12):1036–1040. doi: 10.1080/14786410500183985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soontornniyomkij V., Umlauf A., Chung S.A., Cochran M.L., Soontornniyomkij B., Gouaux B. HIV protease inhibitor exposure predicts cerebral small vessel disease. AIDS. 2014;28(9):1297–1306. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaishali D., Niresh H., Fang L.I.P., Desai K., Thummel E., Jashvant D.U. Cytochrome P450 Enzymes and transporters induced by anti-human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors in human hepatocytes: Implications for predicting clinical drug interactions. Drug. Metab. Dispos. 2007;35(10):1473–1477. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.016089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walubo A. The role of cytochrome p450 in antiretroviral drug interactions. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2007;3:583–598. doi: 10.1517/17425225.3.4.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, UNAIDS, UNFPA, UNICEF, UNWomen, & The World Bank Group . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2018. Survive, Thrive, Transform. Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health: 2018 Report on Progress towards 2030 Targets. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Lasker K., Schneidman-Duhovny D., Webb B., Huang C.C., Pettersen E.F. UCSF Chimera, MODELLER, and IMP: an integrated modeling system. J. Struct. Biol. 2012;179(3):269–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ylilauri M., Pentikäinen O.T. MMGBSA as a tool to understand the binding affinities of filamin-peptide interactions. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2013;53(10):2626–2633. doi: 10.1021/ci4002475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]