Summary

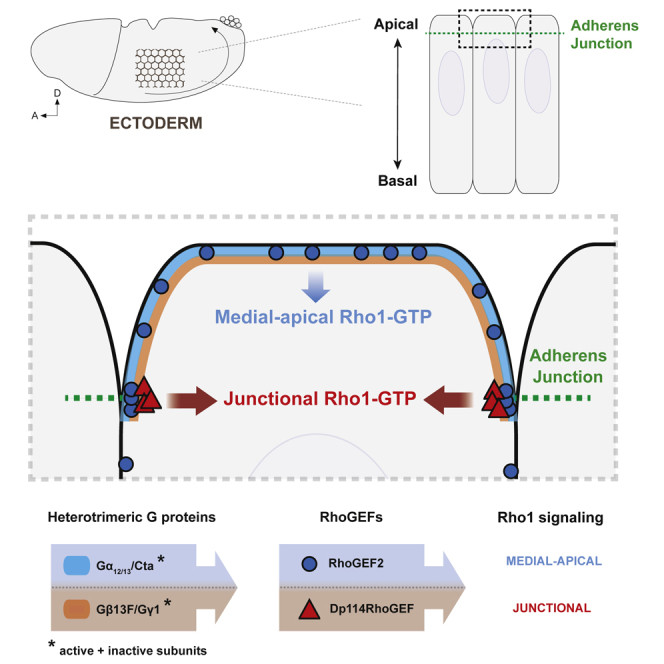

Small RhoGTPases direct cell shape changes and movements during tissue morphogenesis. Their activities are tightly regulated in space and time to specify the desired pattern of actomyosin contractility that supports tissue morphogenesis. This is expected to stem from polarized surface stimuli and from polarized signaling processing inside cells. We examined this general problem in the context of cell intercalation that drives extension of the Drosophila ectoderm. In the ectoderm, G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and their downstream heterotrimeric G proteins (Gα and Gβγ) activate Rho1 both medial-apically, where it exhibits pulsed dynamics, and at junctions, where its activity is planar polarized. However, the mechanisms responsible for polarizing Rho1 activity are unclear. We report that distinct guanine exchange factors (GEFs) activate Rho1 in these two cellular compartments. RhoGEF2 acts uniquely to activate medial-apical Rho1 but is recruited both medial-apically and at junctions by Gα12/13-GTP, also called Concertina (Cta) in Drosophila. On the other hand, Dp114RhoGEF (Dp114), a newly characterized RhoGEF, is required for cell intercalation in the extending ectoderm, where it activates Rho1 specifically at junctions. Its localization is restricted to adherens junctions and is under Gβ13F/Gγ1 control. Furthermore, Gβ13F/Gγ1 activates junctional Rho1 and exerts quantitative control over planar polarization of Rho1. Finally, we found that Dp114RhoGEF is absent in the mesoderm, arguing for a tissue-specific control over junctional Rho1 activity. These results clarify the mechanisms of polarization of Rho1 activity in different cellular compartments and reveal that distinct GEFs are sensitive tuning parameters of cell contractility in remodeling epithelia.

Keywords: morphogenesis, epithelium, RhoGEF, Rho1, polarity, actomyosin, GPCR, G protein, intercalation, Drosophila

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Dp114RhoGEF activates junctional Rho1 and is involved in cell intercalation

-

•

Gα/Cta and Gβγ subunits tune, respectively, RhoGEF2 and Dp114RhoGEF membrane levels

-

•

Gβγ subunits control planar polarity of junctional Rho1 signaling via Dp114RhoGEF

-

•

Tissue-specific RhoGEFs could diversify morphogenesis in different tissues

Garcia De Las Bayonas et al. investigate the spatial control of Rho1 signaling that drives contractility during epithelial morphogenesis. They identify two RhoGEFs, which independently activate Rho1 at the medio-apical and junctional compartments in intercalating cells. This process requires upstream control by distinct heterotrimeric G proteins.

Introduction

Contractile actomyosin networks power cell shape changes during tissue morphogenesis [1, 2, 3]. By pulling on actin filaments anchored to E-cadherin complexes at adherens junctions, non-muscle myosin-II (Myo-II) motors generate tensile forces whose amplitude and orientation determine the nature of cell- and tissue level-deformation [4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. Consequently, specific cortical Myo-II patterns predict specific cell shape changes underlying tissue dynamics [9, 10]. During Drosophila embryogenesis, apical constriction of cells underlies mesoderm invagination [11, 12]. Apical constriction is driven by a strictly medial-apical pool of Myo-II [13]. In contrast, during elongation of the ventro-lateral ectoderm (also called germ-band extension), cells intercalate as a consequence of a polarized shrinkage of dorso-ventral interfaces or “vertical junctions” [14, 15, 16]. This process depends on both a medial-apical pulsatile Myo-II pool and a planar-polarized junctional Myo-II pool to remodel cell interfaces during tissue extension [15, 16, 17].

The small guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) Rho1 is a chief regulator of actomyosin networks in these developmental contexts [18, 19, 20], though Rac1 can also activate actin in epithelial cells [21]. Rho1 cycles between an inactive GDP-bound conformation and an active GTP-bound form. Rho1-GTP binds to and thereby activates the kinase Rok, which in turn phosphorylates non-muscle Myo-II regulatory light chain (MRLC; Sqh in Drosophila). This promotes assembly of Myo-II minifilaments on actin filaments and induces contractility of actomyosin networks. Two families of proteins regulate Rho cycling: Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors (RhoGEFs), which promote the exchange of GDP to active GTP-bound form of Rho1 and Rho GTPase-activating proteins (RhoGAPs) that inactivate Rho1 by promoting GTP hydrolysis to GDP [22]. Recent work has explored the contribution of specific GEFs and GAPs during tissue invagination [23, 24, 25]. In the mesoderm, apically localized RhoGEF2, the Drosophila ortholog of the mammalian RH-RhoGEFs subfamily (p115RhoGEF/PDZ-RhoGEF/LARG) [26, 27, 28], and the RhoGAP Cumberland tune and restrict Rho1 signaling to the apical cell cortex [24]. How Rho1 activity and therefore the Myo-II activity patterns are controlled during cell intercalation where Rho1 is active both medial-apically and at junctions remains unclear.

The Rho1-Rok core pathway activates both medial-apical and junctional Myo-II in the ectoderm [18, 19]. Activation of Rho1 occurs via different molecular mechanisms in these distinct cellular compartments downstream of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and their associated heterotrimeric G proteins [29]. Fog, a GPCR ligand initially reported for its function during apical constriction in the mesoderm [30, 31, 32], is also required for cell intercalation in the ectoderm [29]. It is thus a general regulator of medial-apical Rho1 activation in the embryo, mediated by Gα12/13/Cta and RhoGEF2. In the Drosophila embryo, the Fog-Gα12/13/Cta-RhoGEF2 signaling module specifically controls medial-apical Rho1 activity. The secreted Fog ligand binds to GPCRs Smog and Mist, whose GEF activity catalyzes the dissociation of active Gα12/13/Cta-GTP from Gβγ [29, 33]. Free Gα12/13/Cta-GTP then binds to RhoGEF2 (inferred from RhoGEF2 mammalian orthologs) [28], which in turn activates Rho1, Rok, and Myo-II at the apical membrane. In the mesoderm, apical targeting of RhoGEF2 activity is driven by both active Gα12/13/Cta and enhanced by the mesoderm-specific apical transmembrane protein T48, which binds the PDZ domain of RhoGEF2 [34]. Whether Gα12/13/Cta is sufficient to localize RhoGEF2 activity medial-apically in the ectoderm, where T48 is not expressed, is unknown.

A separate biochemical module was hypothesized to control and polarize junctional Rho1 independently in the ectoderm, but the underlying molecular mechanisms remain unclear. The pair-rule genes even-skipped (eve) and runt were the first upstream regulators of planar polarized junctional Myo-II identified in the ectoderm [14, 35]. The Toll receptors (Toll2/6/8) are transmembrane proteins whose expression in stripes is regulated by Eve and Runt and who are essential for the polarization of Myo-II [36]. However, the molecular mechanisms linking Tolls to Rho1 activation remain uncharacterized. The GPCR Smog and the two heterotrimeric G protein subunits Gβ13F/Gγ1 are involved in the tuning of Rho1 activity at ectodermal junctions [29]. However, in the absence of a direct junctional Rho1 activator, e.g., a specific RhoGEF, it is difficult to understand how these upstream regulators polarize the GTPase activity. In this study, we aim to dissect the spatial and temporal control of both medial-apical and junctional Rho1 activity in the ectoderm.

Results

RhoGEF2 Controls Medial-Apical Rho1 Activity in the Ectoderm

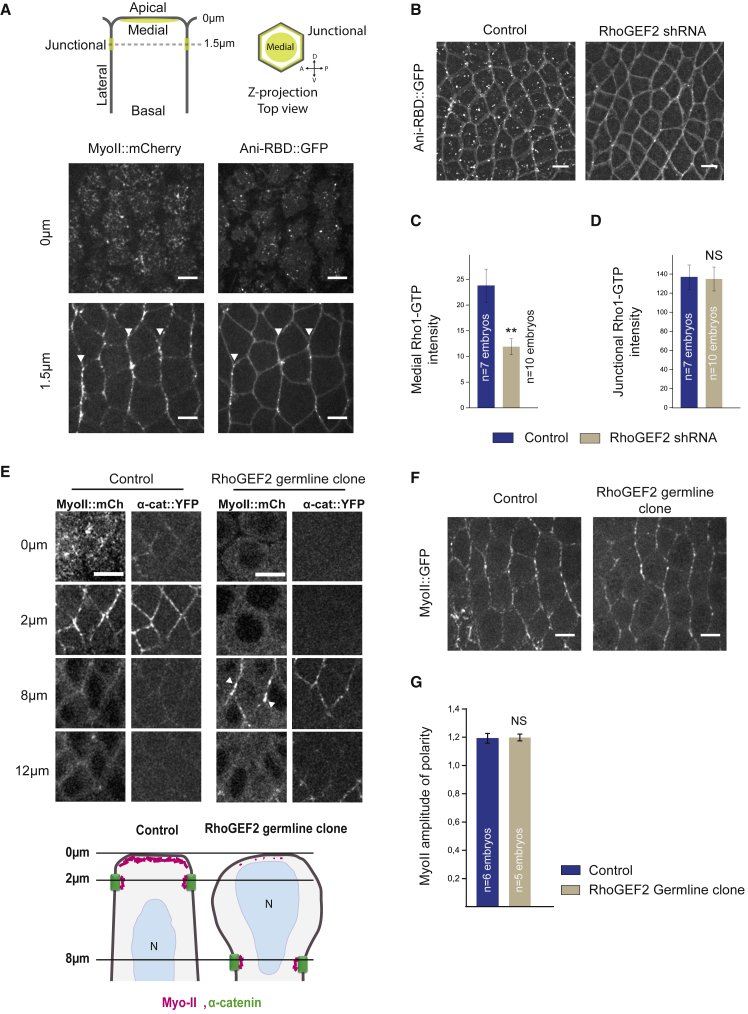

We used a Rho1-GTP biosensor that consists of a fusion protein between mEGFP (A206K monomeric EGFP) and the Rho-binding domain (RBD) of anillin, which binds selectively to active Rho1-GTP (Ani-RBD::GFP) [19] in the ectoderm. Ani-RBD::GFP localization shows that active Rho1 is present both medial-apically (Figure 1A, top panel right) and at adherens junctions (Figure 1A, bottom panel right), where it is planar polarized (white arrowheads) as previously reported [19]. Importantly, the Rho1 activity pattern is not a consequence of a differential subcellular enrichment in Rho1 protein. Indeed, Rho1 is uniformly distributed along cell membrane in contrast to the planar polarized Rho1-GTP biosensor (Figures S1A–S1C). Hence, Rho1 regulators spatially control Rho1 activity in this tissue. RhoGEF2 is a major activator of the medial-apical Myo-II pool, but not the junctional pool in the ectoderm [29]. Therefore, we first asked whether medial-apical Rho1 activity is specifically decreased upon RhoGEF2 knockdown. The Rho1-GTP biosensor was analyzed in embryos expressing short hairpin RNA (shRNA) against RhoGEF2 driven by maternally supplied Gal4 (matα-Gal-VP16). We found that Rho1-GTP was indeed decreased apically but strikingly preserved at junctions (Figures 1B–1D; Video S1), consistent with the specific regulation of medial-apical Myo-II by RhoGEF2 previously described [29].

Figure 1.

RhoGEF2 Activates Medial-Apical, but Not Junctional, Rho1 in the Ectoderm

(A) Apical (0 μm) and junctional (1.5 μm) confocal z sections of ventro-lateral ectodermal cells from embryos expressing Myo-II::mCherry and Ani-RBD::GFP, 8 min after the onset of cephalic furrow formation. White arrowheads show planar-polarized Myo-II and Rho1-GTP at vertical junctions.

(B) 7 μm projections of confocal acquisitions in both control and RhoGEF2 shRNA embryos expressing Ani-RBD::GFP.

(C and D) Quantifications of mean medial-apical Rho1-GTP and mean junctional Rho1-GTP intensities in control and RhoGEF2 shRNA embryos. Medial Rho1-GTP is decreased in the RhoGEF2 knockdown condition while junctional Rho1-GTP intensity is unchanged compared to control.

(E) Top panels: apical (0 μm), junctional (2 μm), and lateral (8 and 12 μm) confocal z sections of ectodermal cells in control and RhoGEF2 germline clone embryos expressing Myo-II::mCherry and α-catenin::YFP, a junctional marker. Medial-apical Myo-II is lost in mutant embryos, and Myo-II is still detected at junctions in this condition (white arrowheads). Although half of the RhoGEF2 germline clone embryos express RhoGEF2 zygotically, no rescue has been observed for Myo-II apical levels, suggesting that maternally loaded RhoGEF2 mainly controls the process in a wild-type embryo at this stage. Bottom panel: schematic view of Myo-II and adherens junction distribution in both control and RhoGEF2 mutant ectodermal cells is shown.

(F) Stack-focused image of control embryos (from 2 to 6 μm below apical membrane) and RhoGEF2 germline clone embryos (from 8 to 12 μm below apical membrane) expressing Myo-II::GFP. Note that the planar-polarized Myo-II cables are still detected in RhoGEF2 germline clone.

(G) Myo-II amplitude of polarity at junctions in control and RhoGEF2 germline clone. No difference in junctional Myo-II planar polarity is observed between the two conditions. The weak values of junctional Myo-II polarity measured in this experiment are due to an absence background subtraction during the post-processing of the image.

Scale bars represent 5 μm. Means ± SEM between images are shown. Statistical significance has been calculated using Mann-Whitney U test. Not significant (ns), p > 0.05; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01. All the panels have the same orientation: dorsal at the top and anterior to the left.

See also Figures S1, S4, and S7 and Video S1.

Ani-RBD::GFP; Scale bar = 5μm. Duration: 2min.

These shRNA studies could not rule out a residual RhoGEF2 population signaling at junctions. Therefore, we generated RhoGEF2 maternal and zygotic mutants with germline clones using a null allele for RhoGEF2, DRhoGEF2l(2)04291 [37], and observed a complete loss of medial-apical Myo-II together with an expanded cell surface area (Figure 1E). Interestingly, junctional Myo-II persisted in RhoGEF2 mutant embryos and its planar polarity was not affected (Figures 1F and 1G). Adherens junctions were also found deeper in the tissue relative to wild-type junctions, consistent with a role of apical contractility in the positioning of apical junctions [31, 38]. Thus, loss of RhoGEF2 affects medial-apical, but not junctional, Rho1 signaling. Overall, in the ectoderm, RhoGEF2 is specifically required for Rho1 medial-apical activation, but not for junctional activation and planar polarization.

Regulation of RhoGEF2 Localization and Activity in the Ectoderm

The spatial distribution of Rho1 signaling could stem from specific control over the localization and/or activity of upstream Rho1 regulators [23, 24]. Therefore, we analyzed RhoGEF2 localization in the ectoderm by imaging embryos expressing RhoGEF2::GFP [24], whose expression rescues early embryonic phenotypes in RhoGEF2 mutants, and Myo-II::mCherry. RhoGEF2 was enriched both apically and at cell junctions (Figure 2A), in agreement with previous reports [24, 39]. Additionally, we detected a highly dynamic pool of RhoGEF2 « comets » in the cytoplasm (Figure 2A, middle right panel, yellow arrowheads), consistent with the observation that RhoGEF2 localizes at microtubule growing (plus) ends in S2 culture cells [40]. To test this further in vivo, we analyzed embryos co-expressing RhoGEF2::RFP and GFP-tagged EB1, a microtubule plus end tracking protein, and found that indeed RhoGEF2::RFP co-localizes with EB1::GFP comets (Figure 2B; Video S2). The much broader spatial distribution of RhoGEF2 with respect to where RhoGEF2 is specifically required for Rho1 activation led us to ask whether RhoGEF2 activity is spatially segregated in the ectoderm.

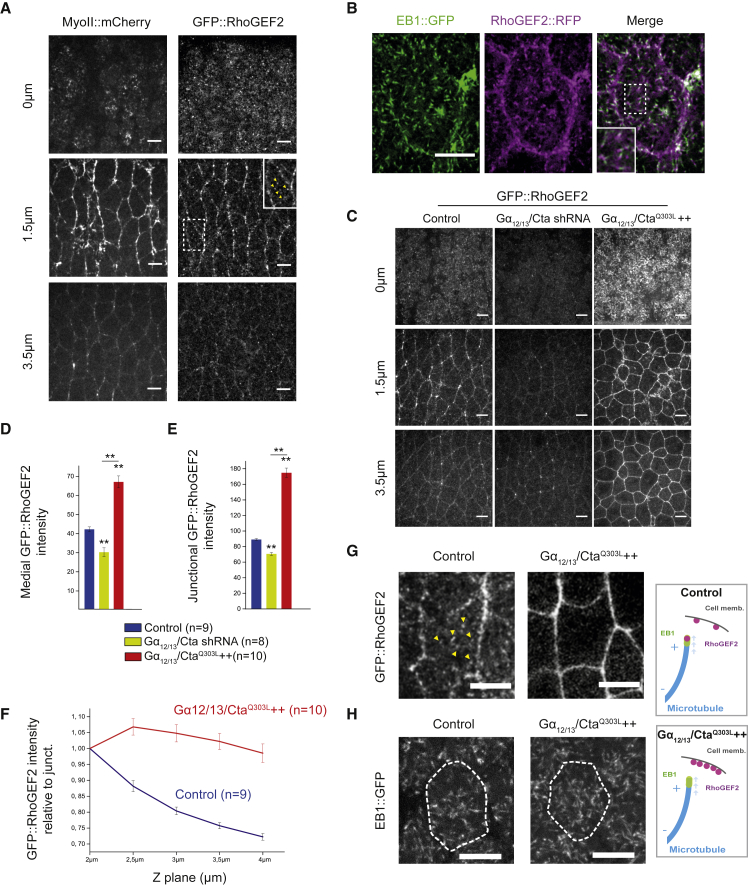

Figure 2.

Gα12/13/Cta-GTP and Microtubules Control RhoGEF2 Enrichment at Cell Membrane in the Ectoderm

(A) Apical (0 μm), junctional (1.5 μm), and lateral (3.5 μm) z sections of ectoderm tissue co-expressing Myo-II::mCherry and GFP::RhoGEF2. Middle right panel, bottom left corner: a close up of a cell showing GFP::RhoGEF2 « comets » is shown (yellow arrowheads)

(B) Confocal z section of an ectodermal cell co-expressing RhoGEF2::RFP and EB1::GFP (1 z plan, 2 μm below the apical membrane). Both EB1 and RhoGEF2 « comets » co-localize; a slight spatial shift is observed between the two signals due to the acquisition condition (sequential acquisition).

(C) Apical (0 μm), junctional (1.5 μm), and lateral (3.5 μm) z sections of ectoderm tissue expressing GFP-RhoGEF2 in control, Gα12/13/Cta shRNA, and Gα12/13/CtaQ303L++ embryos. Note that the brightness of the GFP-RhoGEF2 signal has been artificially decreased in the Gα12/13/CtaQ303L++ panels for better visualization.

(D and E) Quantifications of mean medial-apical and junctional GFP::RhoGEF2 intensities in control, Gα12/13/Cta shRNA, and Gα12/13/Cta Q303L++ embryos. n, number of embryos. Medial and junctional GFP::RhoGEF2 intensities are decreased in Gα12/13/Cta shRNA embryos but are increased in Gα12/13/Cta Q303L++ embryos compared to control.

(F) Total GFP::RhoGEF2 cortical levels normalized to the apical junctional intensities (2 μm below the apical membrane).

(G) Confocal Z section of an ectodermal cell expressing GFP::RhoGEF2 in control and Gα12/13/CtaQ303L++ embryos (2 μm below the apical membrane). GFP::RhoGEF2 « comets » (yellow arrowheads) are absent from Gα12/13/CtaQ303L++ embryos.

(H) Confocal cross-section of an ectodermal cell (1 μm below apical membrane) expressing EB1::GFP in control and Gα12/13/CtaQ303L++ embryos.

Scale bars represent 5 μm. Means ± SEM between images are shown. Statistical significance has been calculated using Mann-Whitney U test. ns, p > 0.05; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01. All the panels have the same orientation: dorsal at the top and anterior to the left.

See also Figures S2 and S7 and Videos S2 and S3.

Scale bar = 5μm. Duration: 4 s.

Gα12/13/Cta and the membrane anchor T48 promote RhoGEF2 activation at the cell membrane in Drosophila upon GPCR activation [34, 40]. Both regulators cooperate to recruit RhoGEF2 to the apical membrane in the mesoderm, where it activates Rho1 signaling. T48 anchors RhoGEF2 via a direct PDZ domain interaction. By analogy to its mammalian homolog p115RhoGEF, RhoGEF2 is thought to bind to active Gα12/13/Cta via its N-terminal RH domain. A conformational change then dislodges the autoinhibitory N-terminal tail of the RhoGEF from its DH-PH domains, making them accessible for binding to Rho1 and membrane lipids [28]. Although this allosteric regulation by active Gα12/13/Cta is sufficient to increase p115RhoGEF binding to the membrane, it is not clear whether a full activation of the RhoGEF requires additional control. T48 is not expressed in the ectoderm [34] and therefore cannot account for RhoGEF2 activity at the apical membrane, though T48 overexpression in the ectoderm can increase apical Myo-II activation (data not shown) similar to RhoGEF2 overexpression [29]. We previously showed that the Gα12/13/Cta-dependent increase of medial-apical Myo-II is abolished upon RhoGEF2 knockdown in the lateral ectoderm, indicating that RhoGEF2 transduces the signal downstream of Gα12/13/Cta [29]. Therefore, Gα12/13/Cta is a strong candidate for controlling RhoGEF2 localization and activity in the ectoderm. We examined RhoGEF2 localization in Gα12/13/Cta-depleted embryos and in embryos expressing constitutively active Gα12/13/Cta, Gα12/13/Cta Q303L (a mutant that mimics the GTP-bound state). Apical and junctional RhoGEF2 levels in Gα12/13/Cta knockdown embryos (Figure 2C) significantly decreased (Figures 2D and 2E). This shows that Gα12/13/Cta contributes to localizing RhoGEF2 in both compartments. Strikingly, in Gα12/13/ Cta Q303L embryos, RhoGEF2 was strongly enriched everywhere at the cell surface, namely the apical membrane, at junctions and along the lateral cell surface (Figures 2C–2E). In contrast, RhoGEF2 « comets » were completely absent from the cytoplasm in this condition (Figure 2G, yellow arrowheads; Video S3) and EB1 comets were still present as in controls (Figure 2H). This suggests that Gα12/13/Cta-GTP promotes RhoGEF2 re-localization from microtubule growing ends to the cell membrane upon GPCR activation, as reported in S2 cells [40]. We further tested whether microtubules sequester RhoGEF2 and thereby limit RhoGEF2 membrane recruitment and signaling. Microtubule depolymerization following injection of colcemid caused germ-band extension defects (Figures S2A and S2B) and a medial-apical increase in Myo-II activation together with a decrease in junctional Myo-II (Figures S2C–S2E). The medial-apical phenotype was similar to RhoGEF2 or Gα12/13/Cta overexpression [29], arguing that microtubules sequester and thereby limit RhoGEF2 signaling medial-apically. Note that, although medial-apical Rho1-GTP levels increased in Gα12/13/CtaQ303L-expressing embryos, they were unchanged at junctions (Figures S2E–S2G), consistent with the previous report showing that only medial-apical Myo-II was affected in such conditions [29]. Thus, although active Gα12/13/Cta shifts RhoGEF2 distribution from microtubule plus ends to both the medial-apical membrane and cell junctions in the wild-type and in overexpression conditions, RhoGEF2 signaling is consistently restricted to the apical membrane.

GFP::RhoGEF2; Scale bar = 5μm. Duration: 14 s.

Identification of a New RhoGEF Involved in Tissue Extension

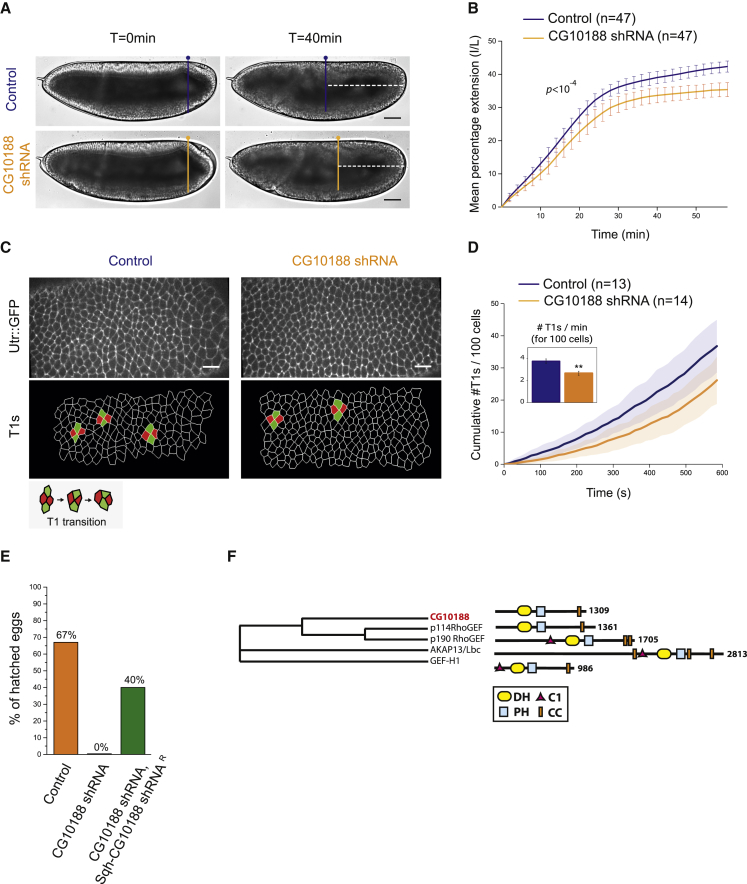

The striking apical specificity of RhoGEF2 indicates that other RhoGEF(s) activate junctional Rho1 in the ectoderm. We screened all 26 predicted Drosophila RhoGEFs for defects in germ-band extension by expressing shRNA maternally and zygotically. Knockdown of the maternal contribution was crucial in such experiments, as a strong maternal mRNA loading is observed for a large number of RhoGEFs in the embryo (modENCODE_mRNA-seq; Flybase) [41]. Knockdown of CG10188 (verified at the mRNA and protein levels; Figures S3A and S3B) slowed germ-band extension (Figures 3A and 3B). Notably, intercalation events (also called T1 events), which underlie tissue extension [15, 42], were significantly decreased in CG10188 shRNA-expressing embryos (Figures 3C and 3D; Video S4). Severe developmental defects were also observed at later stages, such as the absence of germ-band retraction and the occurrence of cell delamination, resulting in a fully penetrant embryonic lethality (data not shown). We designed a transgene that ubiquitously expresses a modified form of the CG10188 mRNA immune to targeting by the shRNA, although with preserved codon usage (SqhPa-CG10188-shRNAR; STAR Methods). This transgene rescued lethality in CG10188 shRNA-expressing embryos and proved the specificity of the knockdown (Figure 3E). Overall, these results demonstrate a requirement for CG10188 during germ-band extension.

Figure 3.

A New RhoGEF Controls Cell Intercalation during Germ-Band Extension

(A) Lateral view of a control and a CG10188 shRNA-expressing embryo at the onset (t = 0 min) of germ-band extension (GBE) and 40 min later. The dotted lines mark the distance between the pole cells and the posterior side of the embryos 40 min after the onset of GBE.

(B) Quantification of the rate of germ-band extension in control and CG10188 shRNA embryos. A significant difference was observed in CG10188 shRNA embryos (Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test). p value for Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test is indicated in the panel. p > 0.01.

(C) Top panels: a representative view of the extending ventro-lateral ectoderm in control and CG10188 shRNA embryos expressing Utr::GFP. Bottom panels: segmented view of the same embryos is shown. T1 transitions are depicted in green and red on the image.

(D) Cumulative sum of T1 transitions measured for control and CG10188 shRNA embryos over a period of 10 min.

(E) Percentage of embryos that hatched in control (n = 238/354 embryos), CG10188 shRNA (n = 0/243 embryos), and CG10188 shRNA, Sqh-cg10188wt shRNA (n = 86/213 embryos) conditions. The egg-hatching percentage was determined as a measurement of embryo viability (STAR Methods). The fully penetrant embryonic lethality observed in CG10188 shRNA embryos is rescued by the expression of the targeted gene refractory to the shRNA (Sqh-CG10188 shRNAR).

(F) Phylogenetic tree inferred from sequence similarity between the Drosophila CG10188 (Flybase: FBgn0032796) and its human orthologs p114RhoGEF (UniProtKB: Q6ZSZ5-4), GEF-H1 (UniProtKB: Q92974-1), p190RhoGEF (UniProtKB: Q8N1W1-1), and AKAP13 (UniProtKB: Q12802-1). Human sequences were collected from UniProt and clustered by multiple sequence alignment using ClustalOmega (nj tree, no distance correction). CG10188 exhibits a DH-PH tandem characteristic of the Dbl-RhoGEFs and a coil-coiled (CC) motif in its C-terminal region, known to be a dimerization domain in its mammalian counterparts.

Scale bars represent 50 μm (A) and 15 μm (C). Error bars, SD for (B) and SEM for (D).

Scale bar = 15μm. Red/Green: T1s. Duration: 10min.

CG10188 has not yet been functionally characterized in Drosophila. From sequence and domain similarity, CG10188 is the ortholog of the mammalian RhoGEF subfamily, including p114RhoGEF, AKAP13, GEF-H1, and p190RhoGEF, who each activate RhoA [43, 44] (Figure 3F). Based on their sequence and function [45] compared with our data hereafter, we conclude that p114RhoGEF is the closest mammalian ortholog of the Drosophila CG10188, and we will now refer to CG10188 as Dp114RhoGEF. Transcriptomic analyses reported a maternal and zygotic expression of Dp114RhoGEF in the embryo, suggesting that the protein could be present and active in the ectoderm [46, 47].

Dp114RhoGEF Activates Rho1 Signaling at Adherens Junctions in the Ectoderm

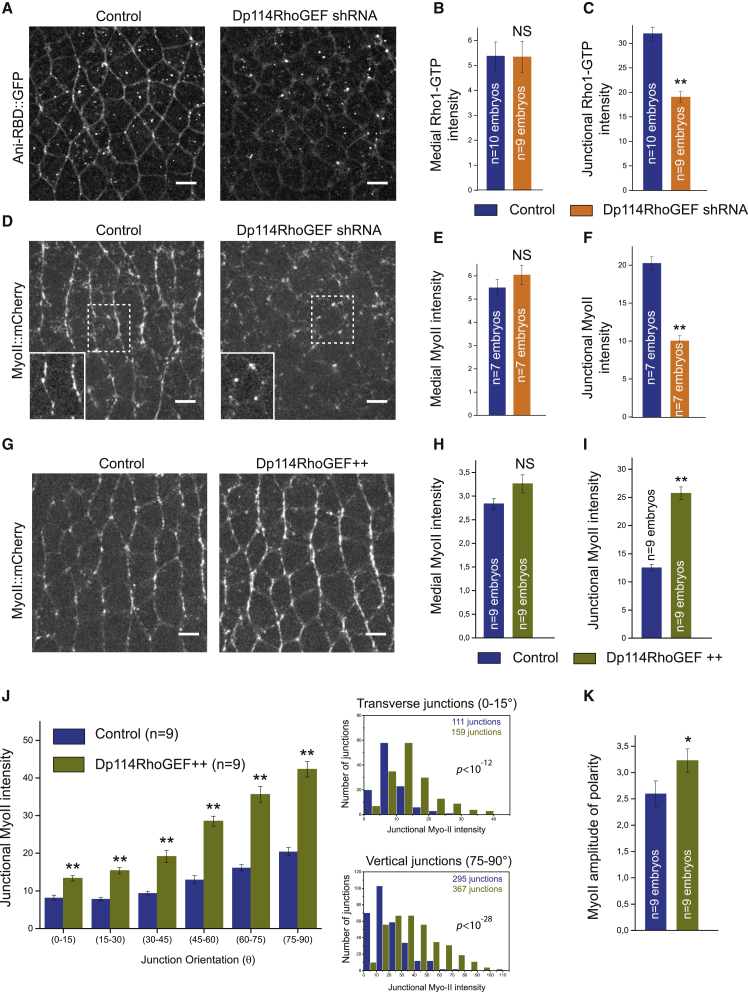

To test whether Dp114RhoGEF controls Rho1 activity in the ectoderm, we investigated the distribution of the Rho-GTP biosensor in Dp114RhoGEF shRNA-expressing embryos. In striking contrast to the RhoGEF2 knockdown, medial-apical Rho1-GTP levels were unaffected, whereas junctional Rho1-GTP was strongly decreased (Figures 4A–4C). The loss of active junctional Rho1 suggested that junctional Myo-II might be affected. Therefore, we analyzed Myo-II::mCherry in control and Dp114RhoGEF shRNA embryos. Similar to Rho1-GTP, junctional Myo-II was strongly reduced and medial-apical Myo-II was preserved (Figures 4D–4F and S3C; Video S5). Importantly, the expression of the Dp114RhoGEF-shRNAR transgene in Dp114RhoGEF shRNA embryos rescued Myo-II junctional levels (Figures S3D and S3E). We noticed that Myo-II persisted at cell vertices in the Dp114RhoGEF knockdown (Figure 4D, bottom right panel). Rho1-GTP is not detected at vertices in this condition (Figure 4A), which suggests either a redistribution of remaining active Myo-II in this condition or that Myo-II could be activated through different mechanisms in this compartment. Last, compared to wild-type, E-cadherin levels were globally reduced in Dp114RhoGEF knockdown embryos with a highly discontinuous E-cadherin distribution at junctions (Figures S3F–S3H). Similar E-cadherin defects have been observed upon dominant-negative Rho1 expression and Rho1 inhibition [18, 48, 49], consistent with the specificity of Dp114RhoGEF for Rho1 signaling.

Figure 4.

Dp114RhoGEF Activates Junctional Rho1 Signaling in the Ectoderm

(A) 4 μm z projection of confocal acquisition of control or Dp114RhoGEF shRNA embryos expressing Ani-RBD::GFP. Active Rho1 is specifically decreased at junctions upon Dp114RhoGEF knockdown.

(B and C) Mean medial-apical and junctional Rho1-GTP intensities in both control and Dp114RhoGEF shRNA embryos. Junctional Rho1-GTP is decreased in the Dp114RhoGEF knock-down condition while medial Rho1-GTP intensity is unchanged compared to control.

(D) Confocal acquisitions of control and Dp114RhoGEF shRNA embryos expressing Myo-II::mCherry. A close up of a representative cell is shown in the bottom part left panel for both conditions (the most apical z planes containing medial-apical Myo-II have been removed for a better visualization of junctional Myo-II::mCherry signal in the close-up views).

(E and F) Quantifications of mean medial-apical and junctional Myo-II intensities in both control and Dp114RhoGEF shRNA embryos. Junctional Myo-II is decreased in Dp114RhoGEF knock-down embryos compared to control while medial Myo-II intensity is unaffected in this condition.

(G) Myo-II::mCherry in control and Sqh-Dp114RhoGEF embryos (Dp114RhoGEF++).

(H and I) Mean medial-apical and junctional Myo-II intensities in control and Dp114RhoGEF++ embryos. Dp114RhoGEF overexpression does not affect medial Myo-II intensity while junctional Myo-II intensity doubled in this condition compared to control.

(J) Left panel: mean junctional intensity of Myo-II according to the angle of the junctions (junction angle; 0°, parallel to the antero-posterior axis; 90°, perpendicular to the antero-posterior axis). Right panels: distributions of junctional Myo-II intensity values at transverse (0°–15°) and vertical junctions (75°–90°) in control and Dp114RhoGEF++ embryos are shown. A significant difference was observed in both angular ranges (Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test). p values for Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test in each comparison are indicated on the plot. ns, not significant, p > 0.05.

(K) Quantification of Myo-II amplitude of polarity in control and Dp114RhoGEF++ embryos. Amplitude of polarity is measured as the ratio of mean Myo-II intensity at vertical junctions to mean Myo-II intensity at transverse junctions.

Scale bars represent 5 μm. Means ± SEM are shown. Statistical significance has been calculated using Mann-Whitney U test. ns, p > 0.05; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01.

See also Figures S3, S4, and S7 and Videos S5 and S6.

MyoII::mCherry; Scale bar = 5μm. Duration: 15min.

RhoGEF2 exhibits a dose-dependent effect on medial-apical Rho1 signaling in that overexpression of RhoGEF2 is sufficient to increase medial Rho1-GTPase and Myo-II activation [29, 50]. Therefore, we asked whether increasing Dp114RhoGEF expression levels could, symmetrically, increase Rho1 signaling at junctions. The Dp114RhoGEF levels were increased by driving Dp114RhoGEF wild-type coding sequence under control of the ubiquitous MRLC/Sqh promoter in Myo-II::mCherry embryos. The result was unique and striking: Dp114RhoGEF overexpression led to a global Myo-II junctional increase relative to control with no effect on medial-apical Myo-II (Figures 4G–4I; Video S6). Myo-II was increased both at transverse (0°–15°; 63% increase) and vertical junctions (75°–90°; 200% increase; Figure 4J), with a resulting modest (24%) increase in planar polarity (Figure 4K). Thus, Dp114RhoGEF tunes Rho1 signaling in a dose-dependent manner at junctions.

MyoII::mCherry; Scale bar = 5μm. Duration: 15min.

RhoGEF2 and Dp114RhoGEF show complementary spatial restriction of activity on Rho1 signaling. We thus hypothesized that a double knockdown of both RhoGEFs should abolish total Rho1 activity in the ectoderm. Indeed, Rho1-GTP and Myo-II were decreased both apically and at cell junctions in this context (Figures S4A–S4F). Together, our data demonstrate that Dp114RhoGEF is a key activator of Rho1 signaling at adherens junctions in the ectoderm. Moreover, RhoGEF2 and Dp114RhoGEF have additive and non-redundant functions in the ectoderm.

Dp114RhoGEF Mediates Gβ13F/Gγ1-Dependent Junctional Rho1 Signaling

Given the critical function of Gβ13F/Gγ1 in the regulation of medial-apical and junctional Myo-II pools [29], we examined its link with Dp114RhoGEF at junctions. We first tested whether Rho activity was dependent upon Gβ13F/Gγ1. We analyzed the Rho1-GTP biosensor distribution in both Gβ13F/Gγ1 loss-of-function (Gγ1 germline clone) and gain-of-function (Gβ13F/Gγ1 overexpression) conditions. Loss of Gγ1 resulted in a reduction of both junctional and medial-apical Rho1-GTP, consistent with the overall reduction in Myo-II previously reported [29] (Figures 5A–5C). Note that the medial-apical decrease in Rho1 signaling does not imply direct Gβ13F/Gγ1 activity apically, as this is expected from the known mechanisms controlling heterotrimeric G protein activation. Indeed, the Gβγ subunit dimer is necessary to properly localize Gα at the membrane and thereby to prime Gα to respond to GPCR GEF activity [51, 52, 53]. Thus, Gβ13F/Gγ1 is required for Gα12/13/Cta activation (Gα-GTP) downstream of GPCRs, such that loss of Gβ13F/Gγ1 also causes loss of Gα12/13/Cta activity.

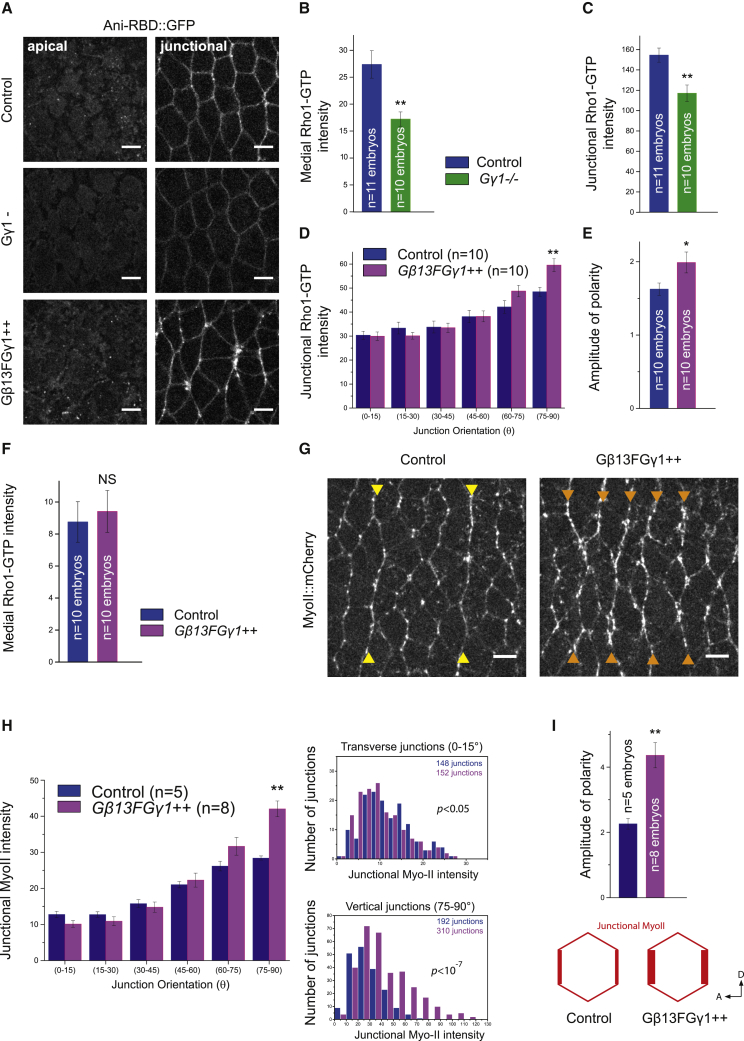

Figure 5.

Gβ13F/Gγ1 Activates and Polarizes Junctional Rho1 Signaling in the Ectoderm

(A) Apical (0 μm) and junctional (1.5 μm) confocal z sections of ventro-lateral ectodermal cells expressing Ani-RBD::GFP in control, Gγ1 germline clone (Gγ1−), and Gβ13F/Gγ1-overexpressing embryos (Gβ13F/Gγ1++).

(B and C) Mean medial-apical and junctional Rho1-GTP intensities in control and Gγ1− embryos. Medial and junctional Rho1-GTP intensities are decreased in Gγ1 mutant compared to control embryos.

(D) Mean junctional intensity of Rho1-GTP according to the angle of the junctions in control and Gβ13F/Gγ1++ embryos.

(E) Rho1-GTP amplitude of polarity.

(F) Medial-apical Rho1-GTP intensities in control and Gβ13F/Gγ1++ embryos.

(G) Confocal acquisitions (4.5 μm projections) showing Myo-II::mCherry in control and Gβ13F/Gγ1++ embryos (yellow arrowheads show two strong compartment boundaries cables of Myo-II in a control embryo; orange arrowheads show the ectopic supracellular cables of Myo-II induced by Gβ13F/Gγ1 overexpression).

(H) Left panel: mean junctional intensity of Myo-II::mCherry according to the angle of the junctions in control and Gβ13F/Gγ1++ embryos. Right panels show the distributions of junctional Myo-II intensity values for transverse (0°–15°) and vertical junctions (75°–90°) in control and Gβ13F/Gγ1++ embryos. We observed a mild statistical difference at the transverse junctions (Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test; p < 0.05). This is explained by an increase in the lower Myo-II intensity values in Gβ13F/Gγ1++ embryos as compared to control. At vertical junctions, a strong statistical difference was observed (p < 10−7) as a consequence of a global increase in Myo-II intensity values in Gβ13F/Gγ1++ embryos compared to control. p values for Kolmogorov-Smirnov test in each comparison are indicated on the plot. ns, not significant, p > 0.05.

(I) Quantification of Myo-II amplitude of polarity in control and Gβ13F/Gγ1++ embryos.

Scale bars represent 5 μm. Means ± SEM are shown. Statistical significance has been calculated using Mann-Whitney U test. ns, p > 0.05; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01.

We then overexpressed both Gβ13F and Gγ1 in embryos to test a dose-dependent effect of these subunits on junctional Rho1 signaling. Overexpression of either Gβ13F or Gγ1 alone did not give any phenotype (data not shown), consistent with studies showing that the individual Gβ and Gγ subunits can neither be transported to the membrane individually nor bind to or signal via their molecular effectors as monomers [54, 55]. In contrast and remarkably, Gβ13F/Gγ1 co-expression resulted in a specific enrichment in Rho1 activity at vertical junctions (23% increase) compared to controls (Figure 5D). Consequently, Rho1-GTP planar polarity was significantly increased (25% increase; Figure 5E). However, medial-apical Rho1 activity was not significantly changed upon Gβ13F/Gγ1 co-expression, indicating a different sensitivity to Gβ13F/Gγ1 levels in the apical compared to the junctional compartments (Figure 5F). Note that Gα12/13/Cta showed the opposite pattern (Figures S2E–S2G). Myo-II::mCherry was next examined in Gβ13F/Gγ1-overexpressing embryos (referred to as Gβ13F/Gγ1++). Consistent with the previous data, we observed a specific increase of Myo-II at vertical junctions (48% increase; Figures 5G and 5H; Video S7), leading to a strong (2-fold) increase in Myo-II planar polarity (Figure 5I). Medial-apical Myo-II levels were unchanged in this condition (data not shown). Because Gβ13F/Gγ1 overexpression hyperpolarized Myo-II in all the ectodermal cells, the strong parasegmental boundaries cables [56] observed in the wild-type (yellow arrowheads in Figure 5G, left panel) were now indistinguishable from the other vertical interfaces (orange arrowheads in Figure 5G, right panel). However, despite a clear effect on junctional Myo-II, the rate of germ-band extension was not affected upon Gβ13F/Gγ1 overexpression (data not shown).

MyoII::mCherry; Scale bar = 5μm. Duration: 17min.

Altogether, we uncovered a new role for Gβ13F/Gγ1 dimer, which is involved quantitatively in the planar polarization of Rho1 signaling at junctions. Therefore, both Gβ13F/Gγ1 and Dp114RhoGEF regulate junctional Myo-II by quantitatively tuning Rho1 activation at junctions.

These results suggested that Dp114RhoGEF might be genetically epistatic to Gβ13F/Gγ1. Thus, we investigated Gβ13F/Gγ1 overexpression in conjunction with Dp114RhoGEF shRNA to explore this relationship. To avoid any differential titration of Gal4 effects, the number of UAS regulatory sequences was equivalent in both the Gβ13F/Gγ1++ and the Gβ13F/Gγ1++, Dp114RhoGEF shRNA embryos (STAR Methods). The polarized increase in Myo-II at vertical junctions in Gβ13F/Gγ1++ embryos was no longer observed in Gβ13F/Gγ1++, Dp114RhoGEF shRNA embryos (Figure 6A), which were indistinguishable from Dp114RhoGEF shRNA embryos alone (Figures 6B and 6C; compare with Figures 4D, S3A, and S3B). Overall, these data show that Dp114RhoGEF is crucial to mediate Gβ13F/Gγ1-dependent Rho1 signaling at junctions.

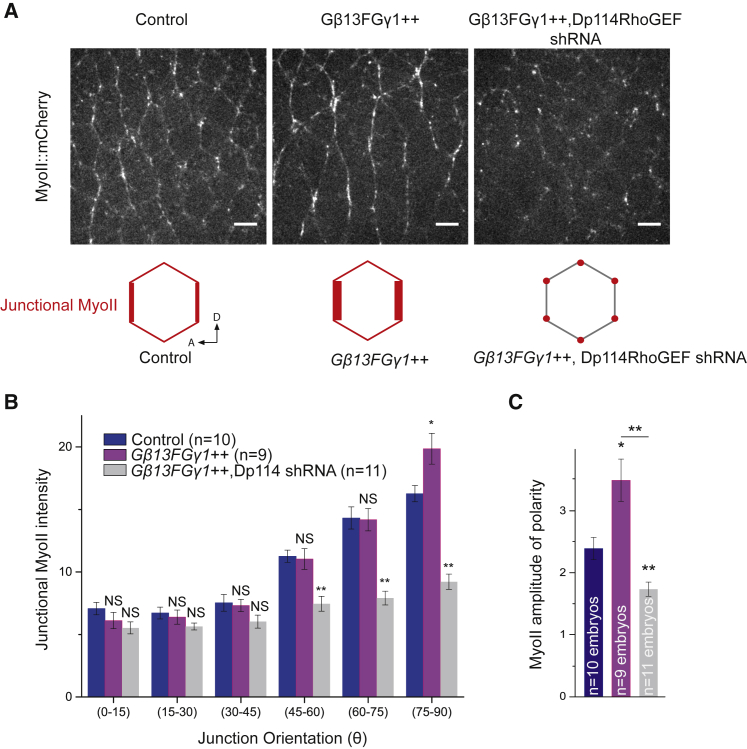

Figure 6.

Dp114RhoGEF Mediates Gβ13F/Gγ1 Signaling at Junctions

(A) Confocal acquisitions of Myo-II::mCherry in the ventro-lateral ectoderm of control, Gβ13F/Gγ1++, and Gβ13F/Gγ1++, Dp114RhoGEF shRNA embryos. The increase of Myo-II at vertical junctions observed in Gβ13F/Gγ1++ embryos is lost when Dp114RhoGEF shRNA is also expressed in the background.

(B) Mean junctional intensity of Myo-II::mCherry according to the angle of the junctions in control, Gβ13F/Gγ1++ embryos, and Gβ13F/Gγ1++, Dp114RhoGEF shRNA embryos.

(C) Amplitude of polarity of junctional Myo-II::mCherry in control, Gβ13F/Gγ1++ embryos, and Gβ13F/Gγ1++, Dp114RhoGEF shRNA embryos. Although Myo-II planar polarity increases upon Gβ13F/Gγ1 overexpression compared to control embryos, co-expression of Gβ13F/Gγ1 together with Dp114RhoGEF shRNA reduces Myo-II planar polarity, similar to Dp114RhoGEF shRNA embryos alone.

Scale bars represent 5 μm. Means ± SEM are shown. Statistical significance has been calculated using Mann-Whitney U test. ns, p > 0.05; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01.

See also Figure S7.

Gβ13F/Gγ1 Regulates Dp114RhoGEF Junctional Enrichment in the Ectoderm

The new genetic interaction between Gβ13F/Gγ1 and Dp114RhoGEF led us to ask whether Gβ13F/Gγ1 subunits could activate and/or localize Dp114RhoGEF at junctions. First, we assessed their respective subcellular distribution in vivo. Transgenic lines that express Dp114RhoGEF tagged with either N-terminal or C-terminal GFP were generated (STAR Methods). Embryos expressing GFP-tagged Dp114RhoGEF and Myo-II::mCherry were imaged. We found that Dp114RhoGEF::GFP localization was restricted to adherens junctions, where it forms puncta in both N- and C-terminal GFP fusions (Figures 7A and S5A). Remarkably, although expressed ubiquitously in the embryo, Dp114RhoGEF::GFP was not detected at junctions in the mesoderm (Figure 7B). It has been reported that Rho1 signaling in mesodermal cells is induced medial-apically and absent from junctions [24]. Therefore, a mesoderm-specific regulation is likely to block junctional Rho1 signaling in this tissue via Dp114RhoGEF mRNA or protein degradation, because we failed to detect any increase in cytoplasmic Dp114RhoGEF::GFP signal in these cells (Figure 7B).

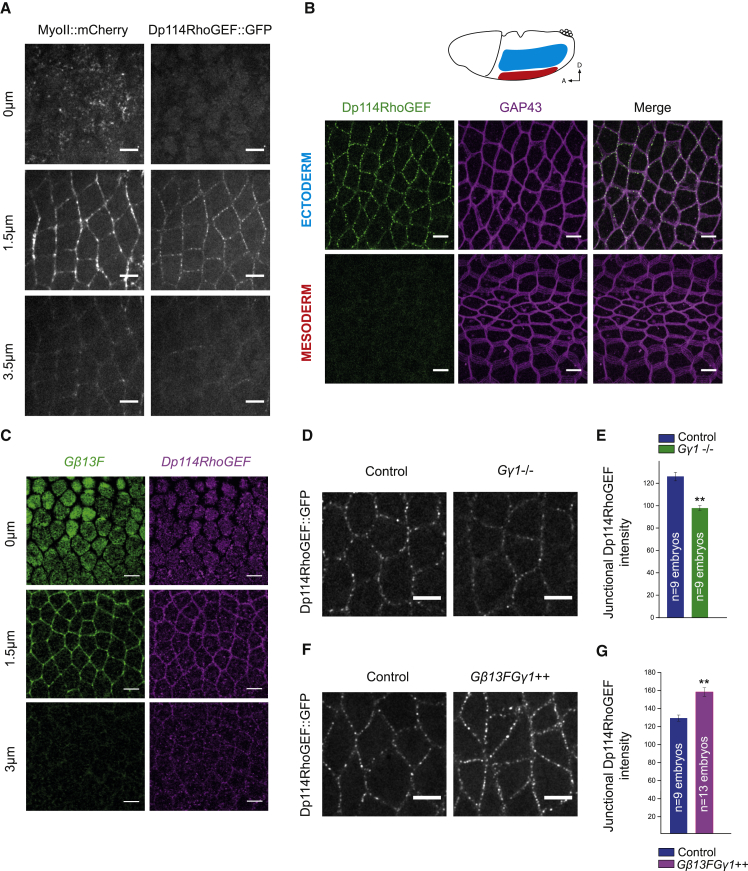

Figure 7.

Dp114RhoGEF Localizes at Adherens Junctions under Control of Gβ13F/Gγ1 in the Ectoderm

(A) Apical (0 μm), junctional (1.5 μm), and lateral (3.5 μm) confocal z sections of ventro-lateral ectodermal cells from embryos co-expressing Myo-II::mCherry and Dp114RhoGEF::GFP. Dp114RhoGEF localizes exclusively at junctions together with junctional Myo-II.

(B) Confocal acquisitions of ectodermal cells (top panels) and mesodermal cells (bottom panels) in embryos expressing Dp114RhoGEF::GFP and GAP43::Cherry. Although Dp114RhoGEF::GFP is detected at junctions in the ectoderm, Dp114RhoGEF::GFP signal is absent from the invaginating mesoderm.

(C) Anti-Dp114RhoGEF::GFP and anti-Gβ13F stainings in ectodermal cells showing the enrichment of both Dp114RhoGEF and Gβ13F at adherens junctions (1.5 μm single plane).

(D and F) Confocal z projections of ectodermal cells expressing Dp114RhoGEF::GFP in control, Gγ1−, and Gβ13F/Gγ1++ embryos. Junctional Dp114RhoGEF is decreased in Gγ1 germline clones and increased upon Gβ13F/Gγ1 overexpression.

(E and G) Quantifications of mean junctional Dp114RhoGEF::GFP intensities in control, Gγ1−, and Gβ13F/Gγ1++ embryos. Junctional Dp114RhoGEF::GFP intensity is decreased in Gγ1− mutant embryos and is increased in Gβ13F/Gγ1++ embryos compared to control.

Scale bars represent 5 μm. Means ± SEM are shown. Statistical significance has been calculated using Mann-Whitney U test. ns, p > 0.05; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01. See also Figures S5–S7.

Planar-polarized Rho1 activity at ectodermal junctions could be explained by a planar-polarized distribution of its direct activator(s) in the ectoderm. To test this hypothesis, we next compared junctional Dp114RhoGEF distribution with the distribution of the non-polarized membrane protein GAP43 in the ectoderm of the same embryos. No difference was observed between Dp114RhoGEF and GAP43 amplitude of polarity (Figures S5B and S5C). Thus, Dp114RhoGEF localization alone cannot account for the polarized Rho signaling at junctions.

Alternatively, Dp114RhoGEF activity could be polarized at junctions. Considering the newly uncovered genetic interaction between Dp114RhoGEF and Gβ13F/Gγ1 in the control of junctional Rho1 signaling, we hypothesized that the heterotrimeric G proteins could be upstream activators of Dp114RhoGEF. Thus, the localization of Gβ13F/Gγ1 could instruct planar polarization of Dp114RhoGEF activity. We generated antibodies against two different peptides of Gβ13F (STAR Methods) and confirmed their specificity by western blot and immunochemistry analyses (Figures S6A–S6C). Both antibodies revealed an apical and junctional enrichment of Gβ13F in the ectoderm (Figure S6C). Furthermore, Gβ13F co-localizes with both Dp114RhoGEF and β-catenin at junctions (Figures 7C and S6D, respectively), where it is not planar polarized (Figure S6E).

Finally, we asked whether Gβ13F/Gγ1 controls Dp114RhoGEF enrichment at junctions. We looked at Dp114RhoGEF::GFP signal in both gain (Gβ13F/Gγ1++) and loss of Gβ13F/Gγ1 (Gβ13F/Gγ1−). Dp114RhoGEF was decreased at junctions upon Gγ1 depletion (Figures 6D and 6E). Conversely, Gβ13F/Gγ1 overexpression led to an increase in Dp114RhoGEF levels at junctions, though strikingly without any gain in planar polarity (Figures 7F, 7G, and S6F), which contrasts with the gain in Rho1-GTP and Myo-II planar polarity in this condition. Taken together, our data show that Gβ13F/Gγ1 subunits are present at adherens junctions, where they increase recruitment of Dp114RhoGEF, allowing Rho1 to signal efficiently in this compartment.

Discussion

Critical aspects of cell mechanics are governed by spatial-temporal control over Rho1 activity during Drosophila embryo morphogenesis. This work sheds new light on the mechanisms underlying polarized Rho1 activation during intercalation in the ectoderm. We found that Rho1 activity is driven by two complementary RhoGEFs under spatial control of distinct heterotrimeric G protein subunits (Figure S7). Notably, we uncovered a regulatory module specific for junctional Rho1 activation.

We identified Dp114RhoGEF as a novel activator of junctional Rho1 in the extending ectoderm. Hence, two RhoGEFs, Dp114RhoGEF and RhoGEF2, coordinate independently the modular Rho signaling during tissue extension of the ectoderm. This has important implications, as it allows us to refine the nature of the interconnection between the two pools of Myo-II in this tissue. We showed previously that medial pulses of Myo-II flow toward and merge with the Myo-II pool at vertical junctions [17]. However, to what extent these “fusion” events contribute to junctional Myo-II was unclear. In the present study, we genetically uncoupled the regulation of both pools of Myo-II and showed that the loss of one pool does not compromise activation of Myo-II in the other. Indeed, junctional Myo-II levels and planar polarity are not affected in RhoGEF2 shRNA embryos or in RhoGEF2 germline clone where medial Myo-II is lost. This rules out the possibility of medial pulses being the main source of junctional Myo-II accumulation. Instead, we conclude that actomyosin flow toward junctions contributes to junction shrinkage because it serves a distinct and direct mechanical function in junction remodeling rather than working by proxy by fueling junctional Myo-II.

The division of labor in the molecular mechanisms of Rho1 activation in distinct cellular compartments lends itself to differential quantitative regulation. The activation kinetics of these different GEFs and nucleotide exchange catalytic efficiencies are likely to differentially impact Rho1 activity and therefore Myo-II activation at the junctional and medial-apical compartments. For example, RhoGEF2 mammalian orthologs, LARG and PDZ-RhoGEF, show a catalytic activity that is two orders of magnitude higher as compared with the Dp114RhoGEF orthologs subfamily [57]. This may help to establish specific contractile regimes of actomyosin in given subcellular compartments. It is therefore important to tightly control RhoGEFs localization and activity to ensure a proper quantitative activation of the downstream GTPase.

RhoGEF2 is a major regulator of medial-apical Rho1 activity during Drosophila gastrulation [34, 37, 58]. Originally characterized in the invaginating mesoderm, we found that RhoGEF2 also activates Rho1 medial-apical activity in the elongating ectoderm. There, RhoGEF2 localizes both medial-apically and at junctions where it is also planar polarized. Although RhoGEF2 and active Rho1 are both planar polarized at junctions, in RhoGEF2 mutants, junctional Rho1-GTP is not affected and ectopic recruitment of RhoGEF2 following expression of Gα12/13Q303L does not cause ectopic junctional Rho1-GTP accumulation. Thus, RhoGEF2 localization at the membrane is not strictly indicative of its activation status. Interestingly, Gα12/13/Cta is necessary for RhoGEF2 to translocate from microtubules plus ends to the plasma membrane where it signals. To date, experimental evidence favor a model whereby the binding of active Gα12/13/Cta to the RhoGEF in the vicinity of the cell membrane triggers its conformational change and stabilizes it in an open conformation able to bind to lipids via its PH domain and signal at the plasma membrane [28]. There is no evidence that Gα12/13/Cta-GTP actively destabilizes RhoGEF2-EB1 interaction, but this is a formal possibility to be tested. Importantly, Gα12/13/Cta alone does not account for the restricted activation of Rho1 medial-apically.

We hypothesize that additional factors must regulate the spatial distribution of RhoGEF2 activity. In principle, RhoGEF2 signaling activity could either be specifically induced medial-apically independent of RhoGEF2 recruitment or RhoGEF2 could be inhibited at junctions and laterally. Sequestration of inactive RhoGEFs at cell junctions has been reported previously in mammalian cell cultures [59, 60], suggesting that such mechanism could be evolutionary conserved. Phosphorylation can control the activity of the RH-RhoGEFs subfamily [61, 62]. Therefore, phosphorylation could promote activation or inhibition of RhoGEF2 activity in specific subcellular compartments in the ectoderm. RhoGEF2 is reported to be phosphorylated in the gastrulating embryo [63].

Complementary to RhoGEF2, Dp114RhoGEF activates junctional Rho1 in the ectoderm. Dp114RhoGEF strictly localizes at junctions (Figure 7A), providing a direct explanation for its junctional-specific effect. We showed that Gβ13F/Gγ1 is also enriched at adherens junctions, where it controls Dp114RhoGEF junctional recruitment together with additional upstream regulators (Figures 7D–7G). Therefore, we suggest that Gβ13F/Gγ1-dependent tuning of junctional Rho1 activation could be achieved through its ability to concentrate the GEF at junctions. Gβ/Gγ-dependent regulation of RhoGEFs has been described in mammals [64, 65]. One study proposes that mammalian p114RhoGEF may bind and be activated by Gβ1/Gγ2 [64]. Interestingly, recent work demonstrates that Gα12 can also recruit p114RhoGEF at cell junctions under mechanical stress in mammalian cell cultures where it promotes RhoA signaling [66]. However, the region of mammalian p114RhoGEF that binds to Gα12 is absent in invertebrate RhoGEFs [67]. How Gβ13F/Gγ1 controls Dp114RhoGEF at junctions in the Drosophila embryo remains an open question. A recent study reports that Dp114RhoGEF localizes at adherens junctions in the Drosophila ectoderm through multiple mechanisms, including interactions with Baz/Par3 and the Crumbs complex [68]. Therefore, investigating a possible connection between Gβ13F/Gγ1 signaling and Baz/Crumbs should help decipher the mechanisms of Dp114RhoGEF localization.

Importantly, neither Gβ13F/Gγ1 nor Dp114RhoGEF are themselves planar polarized at junctions. Hence, their distribution alone cannot explain polarized Rho1 activity at junctions. Strikingly, we found that an increase in Gβ13F/Gγ1 dimers hyperpolarizes Rho1 activity and Myo-II at vertical junctions (Figure 5H). Gβ13F/Gγ1 overexpression also leads to an overall increase in Dp114RhoGEF levels at junctions, although Dp114RhoGEF is not planar polarized in this condition. This indicates that recruitment at the plasma membrane and activation of Dp114RhoGEF are independently regulated, similar to RhoGEF2. In contrast, Dp114RhoGEF overexpression increases Myo-II at both transverse and vertical junctions, although a slightly stronger accumulation is observed at vertical junctions (Figures 4J and 4K). Therefore, although Dp114RhoGEF junctional levels are increased in both experiments, only Gβ13F/Gγ1 overexpression leads to an increased planar polarization of Rho1-GTP and Myo-II at vertical junctions. This points to a key role for Gβ13F/Gγ1 subunits in the planar-polarization process associated with but independent from the sole recruitment of Dp114RhoGEF at junctions. In principle, Gβ13F/Gγ1 could bias junctional Rho1 signaling either by promoting its activation at vertical junctions or by inhibiting it at transverse junctions (e.g., RhoGAP polarized activation). Gβ13F/Gγ1 could also control active Rho1 distribution independent of its activation. For instance, a scaffolding protein binding to Rho1-GTP at junctions could be polarized by Gβ13F/Gγ1 to bias Rho1-GTP distribution downstream of its activation. Anillin, a Rho1-GTP anchor known to stabilize Rho1 signaling at cell junctions [69], is a potential candidate in the ectoderm. Last, Toll receptors control Myo-II planar polarity in the ectoderm [36]. Whether Gβ13F/Gγ1 and Tolls are part of the same signaling pathway is an important point yet to address in the future.

Finally, our study sheds light on new regulatory differences underlying tissue invagination and tissue extension. Here, we found that Dp114RhoGEF localizes at junctions in the ectoderm, where it activates Rho1 and Myo-II. In contrast, maternally and zygotically supplied Dp114RhoGEF::GFP is not detected at junctions in the mesoderm. We see little if any cytoplasmic signal in this condition, suggesting that Dp114RhoGEF::GFP could be degraded in these cells. Thus, repression of Dp114RhoGEF protein in the mesoderm could be an important mechanism for cell apical constriction and proper tissue invagination. Of interest, Rho1 signaling is absent at junctions in the mesoderm [20]. Therefore, it is tempting to suggest that the absence of Dp114RhoGEF at junction in the mesoderm accounts for cells’ inability to activate Rho1 in this compartment. Importantly, the GPCR Smog and Gβ13F/Gγ1 subunits, found to control junctional Rho1 in the ectoderm, are common to both tissues [29]. Dp114RhoGEF differential expression and/or subcellular localization could be a key element to bias signaling toward junctional compartment in the ectoderm.

Cell contractility necessitates activation of the Rho1-Rock-MyoII core pathway. During epithelial morphogenesis, tissue- and cell-specific regulation of Rho1 signaling requires the diversification of Rho1 regulators, in particular RhoGEFs, as shown in this study, and RhoGAPs. Some of them are tissue specific with given subcellular localizations and activation mechanisms. The identification of signaling modules, namely Gα12/13-RhoGEF2 and Gβ13F/Gγ1-Dp114RhoGEF, provides a simple mechanistic framework for explaining how tissue-specific modulators control Rho1 activity in a given subcellular compartment in a given cell type. Therefore, we suggest that the variation of (1) ligands, GPCRs, and associated heterotrimeric G proteins and (2) types of RhoGEFs and RhoGAPs as well as their combination, activation, and localization by respective co-factors underlies the context-specific control of Rho1 signaling during tissue morphogenesis. How developmental patterning signals ultimately control Rho regulators is an exciting area for future investigations.

STAR★Methods

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit Polyclonal anti-Gβ13F (aa 1-15) | This paper | N/A |

| Rabbit Polyclonal anti-Gβ13F (aa 218-233) | This paper | N/A |

| Mouse Monoclonal anti-β catenin | DSHB | RRID: AB_528089 |

| Mouse Monoclonal anti-Neurotactin | DSHB | RRID: AB_528404 |

| Chicken Polyclonal anti-GFP | Aves Labs | GFP-1020; RRID: AB_10000240 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Colcemid-CAS 477-30-5-Calbiochem | Merck | 234109-M |

| Gβ13F peptide (1-15aa): MNELDSLRQEAESLK | Eurogentec, This paper | UniProtKB: P26308 |

| Gβ13F peptide (218-233aa): CKQTFPGHESDINAVT | Eurogentec, This paper | UniProtKB: P26308 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep | Zymo Research | R2050 |

| Superscript IV VILO | Invitrogen | 11766050 |

| TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix | ThermoFisher | 4444557 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| D.melanogaster: y[∗] w[67c23] | Kyoto stock center DGGR | DGRC: 101079 |

| Flybase: FBst0300120 | ||

| D.melanogaster: P{mata4-GAL-VP16}67 | Gift from E. Wieschaus | Flybase: FBti0016178 |

| D.melanogaster: Ubi-GFP::AniRBD | This laboratory | [19] |

| D.melanogaster: RhoGEF2-GFP::RhoGEF2 (vk33) | Gift from Adam Martin | [24] |

| D.melanogaster: Sqh-Sqh::mCh | Gift from Adam Martin (constructs on chromosomes 2 and 3 have been used in all experiments at the exception of Figures 4G–4I); Another construct on chromosome 2 has been generated in this laboratory (only used in Figures 4G–4I) | [70, 71] |

| D.melanogaster: Sqh-eGFP:: Dp114 RhoGEF | This paper | N/A |

| D.melanogaster: Sqh- Dp114 RhoGEF | This paper | N/A |

| D.melanogaster: E-cad::GFP,sqh-Sqh::mCherry | Sqh-mCherry Gift from Adam Martin | Recombinant used in [29] |

| D.melanogaster: y1 sc v1; UAS- Dp114 RhoGEF shRNA | Bloomington Drosophila stock center | BL-41579 |

| D.melanogaster: SqhPa- Dp114 RhoGEF shRNAR | This paper | N/A |

| D.melanogaster: SqhPa-eGFP:: Dp114 RhoGEF shRNAR | This paper | N/A |

| D.melanogaster: w[∗]; P{w[+mC] = mChFP Rho1}21/P{w[+mC] = mChFP-Rho1}21; | Bloomington Drosophila stock center | BL-52281 [72], |

| D.melanogaster: UASt-Gγ1#15 | Gift from Fumio Matsuzaki | [73] |

| D.melanogaster: UASt-Gβ13F#20 | Gift from Fumio Matsuzaki | [73] |

| D.melanogaster: w;FRTG13 Gγ1N159/Cyo, ftz LacZ | Gift from Fumio Matsuzaki | [73, 74] |

| D.melanogaster: P{w[+mW.hs] = FRT(w[hs])}G13 P{w[+mC] = ovoD1-18}2R/Dp(?;2)bw[D], S [1] wg[Sp-1] Ms(2)M [1] bw[D]/CyO | Bloomington Drosophila stock center | BL-2125 |

| D.melanogaster: P{mata4-GAL-VP16}15 | Bloomington Drosophila stock center | FBti0016179 |

| BL-80361 | ||

| D.melanogaster: y1 sc v1;;UAS-RhoGEF2 shRNA | Bloomington Drosophila stock center | BL-34643 |

| D.melanogaster: ;{mata4-GAL-VP16},Sqh-GFP::utABD,Sqh-Sqh::mKate; | This paper | N/A |

| D.melanogaster: UASt-CtaQ303L/TM3 | Gift from Naoyuki Fuse | [73] |

| D.melanogaster: hsflp22; FRTG13 RhoGEF2l(2)04291/Cyo; | Combinant from this laboratory, FRTG13 RhoGEF2l(2)04291 is a Gift from U. Häcker | [37, 39] |

| D.melanogaster: UASp-GAP43::mCherry, nanos-Gal4/TM6Tb | Gift from Manos Mavrakis | N/A |

| D.melanogaster: y1 sc v1; UAS-Yellow shRNA /CyO | Bloomington Drosophila stock center | BL-64527 |

| D.melanogaster: endo-α-Catenin::YFP | Cambridge Protein Trap Insertion line | CPTI-002516 |

| DGRC: 115551 | ||

| D.melanogaster: y1 v1;UAS-Cta shRNA | Bloomington Drosophila stock center | BL-51848 |

| D.melanogaster: w;SP/Cyo;UASp-RFP-RhoGEF2[wt]/TM3, Sb hb-lacZ{ry+} | Gift from Jörg Großhans | [75] |

| D.melanogaster: (y),w; 67-Gal4, UAS-EB1::GFP/CyO, ftz-lacZ | Gift from Damian Brunner | [76] |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Plasmid DNA-Casper SqhPa- Dp114RhoGEF | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid DNA-Casper SqhPa- mEGFP::Dp114RhoGEF | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid DNA-Casper SqhPa- Dp114RhoGEF:: mEGFP | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid DNA-Casper SqhPa- Dp114RhoGEF-shRNAR | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid DNA-Casper SqhPa- mEGFP::Dp114RhoGEF-shRNAR | This paper | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| FlyBase | [42] | https://flybase.org/ |

| ImageJ 1.x | [77] | https://imagej.net/Downloads |

| Fiji | [78] | https://imagej.net/Fiji/Downloads |

| Tissue Analyzer | [79] | https://grr.gred-clermont.fr/labmirouse/software/WebPA/ |

| Stack Focuser | Michael Umorin | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/plugins/stack-focuser.html |

| Axio-Vision software | Zeiss | https://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/int/products/microscope-software/axiovision.html |

| Zen software | Zeiss | https://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/int/products/microscope-software/zen.html |

| MetaMorph microscope automation and Imageanalysis software | Molecular Devices | https://www.moleculardevices.com/products/cellular-imaging-systems/acquisition-and-analysis-software/metamorph-microscopy |

| OriginPro9.0.0 | OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA 01060 USA | https://www.originlab.com/ |

Lead Contact and Materials Availability

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Thomas Lecuit (thomas.lecuit@univ-amu.fr). Plasmids, FASTA sequences and transgenic fly lines generated in this study are all available on request.

Experimental Model and Subject Details

The experiments were performed on Drosophila melanogaster embryos at the early stages of gastrulation (2h30 to 3h after egg laying). We collected embryos from adult flies maintained under the standard lab conditions in plastic vials at 18°C or 25°C with yeast food. Embryo collection was done in cages with agar plate made with apple juice, supplemented with yeast paste. Flies lay eggs on these plates and embryos are filtered from the yeast paste by distilled water. Embryos are then treated with commercial bleach for 45 s and washed abundantly with distilled water. Embryos were staged under the binoculars and stuck on the coverslips. We used Halocarbon oil 200 to cover embryos before live imaging. The embryos were prepared as described in [46]. Please refer to the Key Resources Table for the details of the fly lines being used.

Method Details

Transgenic lines

All fly constructs are listed in the Key Resources Table. 67-Gal4 (mat-4-GAL-VP16), nos-Gal4 and 15-Gal4 are ubiquitous, maternally supplied, Gal4 drivers. Germline clones for Gγ1N159 and RhoGEF2l(2)04291 were made using the FLP-DFS system [80].

SqhPa- Dp114RhoGEF expression vectors were generated using a SqhPa-sqh::mCherry modified vector (kind gift from A. Martin), a pCasper vector containing a sqh (MyoII RLC, CG3595) minimal promoter. A PhiC31 attB sequence was inserted downstream of the white gene of the SqhP vector into AfeI restriction site to perform PhiC31 site specific transgenesis. To build SqhPa- Dp114RhoGEF plasmids, ORF of sqh::mCherry was replaced by the one of Dp114RhoGEF (CG10188) using 2 ESTs as matrices (RE42026 and RE33026) to build a WT sequence (Genebank: NP_609977). Dp114RhoGEF was then tagged either N- or C-terminally by mEGFP with a SGGGGS flexible aa linker in between. SqhPa- Dp114RhoGEF (CG10188) -shRNAR Resistant and SqhPa- eGFP:: Dp114RhoGEF (CG10188) -shRNAR Resistant were built by introducing silent point mutations to the codons of the 21bp targeted by the shRNA TRIP 41579 (CACGAGACAGACAATGGATTA to CAtGAaACtGAtAAcGGtTTA). All recombinant expression vectors were verified by sequence (Genewiz) and were sent to BestGene Incorporate for PhiC31 site specific mediated insertion into attP2 (3L, 68A4). FASTA sequences of these vectors are available on request.

Fly genetics

F1 progeny (embryos) were analyzed for following crosses:

Figure 1A

; Ubi-GFP::AniRBD/Cyo ; Sqh-Sqh::mCh/ Sqh-Sqh::mCh (Females) X ; Ubi-GFP::AniRBD/Cyo; Sqh-Sqh::mCh/ Sqh-Sqh::mCh (Males)

Figures 1B–1D

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}/+;Ubi-GFP::AniRBD/+ (Females) X y[∗] w[67c23] (Males)

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}/+;Ubi-GFP::AniRBD/UAS-RhoGEF2 shRNA (Females) X y1 sc v1;;UAS-RhoGEF2 shRNA (Males)

Figure 1E

; endo-α-Catenin::YFP, Sqh-sqh::mCherry/+ (Females) X y[∗] w[67c23] (Males)

y w hsflp / +;FRTG13 ovoD/ FRTG13 RhoGEF2l(2)04291; endo-α-Catenin::YFP, Sqh-sqh::mCherry/+ (Females) X y w hsflp / FRTG13 RhoGEF2l(2)04291/Cyo,Twist-Gal4,UAS-GFP;+/+ (Males)

Figure 1F

;; Sqh-sqh::GFP/+ (Females) X y[∗] w[67c23] (Males)

y w hsflp / +;FRTG13 ovoD/ FRTG13 RhoGEF2l(2)04291; Sqh-sqh::GFP/+ (Females) X y w hsflp / FRTG13 RhoGEF2l(2)04291/Cyo;+/+ (Males)

Figure 2A

;Sqh-Sqh::mCh/ Sqh-Sqh::mCh;RhoGEF2-GFP::RhoGEF2/ RhoGEF2-GFP::RhoGEF2 (Females) X

;Sqh-Sqh::mCh/ Sqh-Sqh::mCh;RhoGEF2-GFP::RhoGEF2/ RhoGEF2-GFP::RhoGEF2 (Males)

Figure 2B

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}, UAS-EB1::GFP/Cyo; UASp-RhoGEF2::RFP/+ (Females) X ;Sp/Cyo; UASp-RhoGEF2::RFP/ UASp-RhoGEF2::RFP (Males)

Figures 2C–2G

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}/{mata4-GAL-VP16};RhoGEF2-GFP::RhoGEF2/RhoGEF2-GFP::RhoGEF2 (Females) X y[∗] w[67c23] (Males)

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}/{mata4-GAL-VP16};RhoGEF2-GFP::RhoGEF2/RhoGEF2-GFP::RhoGEF2 (Females) X ;;UASt-CtaQ303L/TM3 (Males)

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}/UAS-Cta shRNA ;RhoGEF2-GFP::RhoGEF2/RhoGEF2-GFP::RhoGEF2 (Females) X ;UAS-Cta shRNA/ UAS-Cta shRNA;RhoGEF2-GFP::RhoGEF2/ RhoGEF2-GFP::RhoGEF2 (Males)

Figure 2H

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}, UAS-EB1::GFP/Cyo (Females) X y[∗] w[67c23 (Males)

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}, UAS-EB1::GFP/Cyo (Females) X ;;UAS- CtaQ303L/Tm3 (Males)

Figures 3A and 3B

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}/+; (Females) X y[∗] w[67c23] (Males)

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}/UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA; (Females) X y1 sc v1; UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA; (Males)

Figures 3C and 3D

;{mata4-GAL-VP16},Sqh-GFP::utABD,Sqh-Sqh::mKate/+; (Females) X y[∗] w[67c23] (Males)

;{mata4-GAL-VP16},Sqh-GFP::utABD,Sqh-Sqh::mKate/ UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA; (Females) X y1 sc v1; UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA; (Males)

Figure 3F

w;{mata4-GAL-VP16}/+; (Females) X y[∗] w[67c23] (Males)

w;{mata4-GAL-VP16}/ UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA; (Females) X y1 sc v1; UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA/UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA; (Males)

w; ;{mata4-GAL-VP16}/ UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA; Sqh- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA R/+ (Females) X y1 sc v1; UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA/UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA; (Males)

Figures 4A–4C

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}/+;Ubi-GFP::AniRBD/+ (Females) X y[∗] w[67c23] (Males)

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}/ UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA;Ubi-GFP::AniRBD/+ (Females) X y1 sc v1; UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA/ UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA; (Males)

Figures 4D–4F, S3C, and S3F–S3H

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}, Sqh-Sqh::mCh,Ecad::GFP/+ (Females) X y[∗] w[67c23] (Males)

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}, Sqh-Sqh::mCh,Ecad::GFP/UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA (Females) X y1 sc v1; UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA/UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA; (Males)

Figures 4G–4K

;Ecad::GFP, Sqh-Sqh::mCh/ Ecad::GFP, Sqh-Sqh::mCh; (Females) X ;Ecad::GFP, Sqh-Sqh::mCh/ Ecad::GFP, Sqh-Sqh::mCh; (Males)

;Ecad::GFP, Sqh-Sqh::mCh/ Ecad::GFP, Sqh-Sqh::mCh; Sqh- Dp114RhoGEF / Sqh- Dp114RhoGEF (Females) X ;Ecad::GFP, Sqh-Sqh::mCh/ Ecad::GFP, Sqh-Sqh::mCh; Sqh- Dp114RhoGEF / Sqh- Dp114RhoGEF (Males)

Figures 5A–5F

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}/+; Ubi-GFP::AniRBD/+ (Females) X y[∗] w[67c23] (Males)

y w hsflp / +;FRTG13 ovoD/ FRTG13 Gγ1N159;Ubi-GFP::AniRBD/+ (Females) X w;FRTG13 Gγ1N159/Cyo, ftz LacZ (Males)

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}/UASt-Gβ13F#20; Ubi-GFP::AniRBD/UASt-Gγ1#15 (Females) X ;UASt-Gβ13F#20/ UASt-Gβ13F#20;UASt-Gγ1#15/ UASt-Gγ1#15 (Males)

Figures 5G–5I

w;{mata4-GAL-VP16},Sqh-Sqh::mCh,Ecad::GFP/+; (Females) X y[∗] w[67c23] (Males)

w;{mata4-GAL-VP16},Sqh-Sqh::mCh,Ecad::GFP/ UASt-Gβ13F#20;+/ UASt-Gγ1#15 (Females) X ;UASt-Gβ13F#20/ UASt-Gβ13F#20;UASt-Gγ1#15/ UASt-Gγ1#15 (Males)

Figures 6A–6C

w;{mata4-GAL-VP16},Sqh-Sqh::mCh,Ecad::GFP/+;15-Gal4/+ (Females) X y[∗] w[67c23] (Males)

w;{mata4-GAL-VP16},Sqh-Sqh::mCh,Ecad::GFP/ UASt-Gβ13F#20, UAS-Yellow shRNA;15-Gal4/ UASt-Gγ1#15 (Females) X ;UASt-Gβ13F#20, UAS-Yellow shRNA /UASt-Gβ13F#20, UAS-Yellow shRNA; UASt-Gγ1#15/UASt-Gγ1#15 (Males)

w;{mata4-GAL-VP16},Sqh-Sqh::mCh,Ecad::GFP/ UASt-Gβ13F#20, UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA;15-Gal4/ UASt-Gγ1#15 (Females) X ;UASt-Gβ13F#20, UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA /UASt-Gβ13F#20, UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA; UASt-Gγ1#15/UASt-Gγ1#15 (Males)

Figure 7A

w; Sqh-Sqh::mCh/Sqh-Sqh::mCh; Sqh-eGFP:: Dp114RhoGEF (Nter)/ Sqh-eGFP:: Dp114RhoGEF (Nter) (Females) X w; Sqh-Sqh::mCh/Sqh-Sqh::mCh; Sqh-eGFP:: Dp114RhoGEF (Nter)/ Sqh-eGFP:: Dp114RhoGEF (Nter) (Males)

Figures 7B, S5B, and S5C

;; UASp-GAP43::mCherry, nanos-Gal4/Sqh-eGFP:: Dp114RhoGEF (Nter) (Females) X ;;Sqh-eGFP:: Dp114RhoGEF (Nter)/Sqh-eGFP:: Dp114RhoGEF (Nter) (Males)

Figures 7D–7G and S6F

;;Sqh-eGFP:: Dp114RhoGEF (Nter)/+ (Females) X ;;Sqh-eGFP:: Dp114RhoGEF (Nter)/ Sqh-eGFP:: Dp114RhoGEF (Nter) (Males)

y w hsflp / +;FRTG13 ovoD/ FRTG13 Gγ1N159;Sqh-eGFP:: Dp114RhoGEF (Nter) /+ (Females) X ;FRTG13 Gγ1N159 /Cyo; Sqh-eGFP:: Dp114RhoGEF (Nter)/ Sqh-eGFP:: Dp114RhoGEF (Nter) (Males)

w ;UASt-Gβ13F#20/+; UASt-Gγ1#15/Sqh-eGFP:: Dp114RhoGEF (Females) X ;UASt-Gβ13F#20/ UASt-Gβ13F#20;UASt-Gγ1#15/ UASt-Gγ1#15 (Males)

Figures S1A–S1C

w[∗]; P{w[+mC] = mChFP-Rho1}21/+; Ubi-GFP::AniRBD/+ (Females) X y[∗] w[67c23] (Males)

Figures S2A and S2B

y[∗] w[67c23] (Females) X y[∗] w[67c23] (Males)

Figures S2C and S2D

;Ecad::GFP, Sqh-Sqh::mCh/Ecad::GFP, Sqh-Sqh::mCh; (Females) X ;Ecad::GFP, Sqh-Sqh::mCh/Ecad::GFP, Sqh-Sqh::mCh; (Males)

Figures S2E–S2G

;{mata4-GAL-VP16};Ubi-GFP::AniRBD/TM6 (Females) X y[∗] w[67c23] (Males)

Figure S3B

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}/+; Sqh-eGFP:: Dp114RhoGEF R (Nter)/+ (Females) X y[∗] w[67c23] (Males)

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}/ UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA; Sqh-eGFP:: Dp114RhoGEF shRNA R (Nter)/+ (Females) X y1 sc v1; UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA/UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA; (Males)

Figure S3D

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}, Sqh-Sqh::mCh,Ecad::GFP/+ (Females) X y[∗] w[67c23] (Males)

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}, Sqh-Sqh::mCh,Ecad::GFP/UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA (Females) X y1 sc v1; UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA/UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA; (Males)

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}, Sqh-Sqh::mCh,Ecad::GFP/UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA; Sqh- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA R/+ (Females) X y1 sc v1; UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA/UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA; (Males)

Figures S4A–S4C

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}/+;Ubi-GFP::AniRBD/+ (Females) X y[∗] w[67c23] (Males)

;{mata4-GAL-VP16}/ UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA ; Ubi-GFP::AniRBD/UAS-RhoGEF2 shRNA (Females) X ;UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA/ UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA;UAS-RhoGEF2 shRNA/ UAS-RhoGEF2 shRNA (Males)

Figures S4D–S4F

w;{mata4-GAL-VP16},Sqh-Sqh::mCh,Ecad::GFP/+; (Females) X y[∗] w[67c23] (Males)

w;{mata4-GAL-VP16},Sqh-Sqh::mCh,Ecad::GFP/ UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA; UAS-RhoGEF2 shRNA/+ (Females) X ;UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA/ UAS- Dp114RhoGEF shRNA;UAS-RhoGEF2 shRNA/ UAS-RhoGEF2 shRNA (Males)

Figure S5A

w;; Sqh-eGFP:: Dp114RhoGEF (Nter)/ Sqh-eGFP:: Dp114RhoGEF (Nter) (Females) X w;; Sqh-eGFP:: Dp114RhoGEF (Nter)/ Sqh-eGFP:: Dp114RhoGEF (Nter) (Males)

w;; Sqh- Dp114RhoGEF::GFP (Cter)/ Sqh- Dp114RhoGEF::GFP (Cter) (Females) X w;; Sqh- Dp114RhoGEF::GFP (Cter Sqh- Dp114RhoGEF::GFP (Cter) (Males)

RT-qPCR experiment

CG10188 shRNA (BL41579) knock-down efficiency was estimated by measuring endogenous mRNA level using RT-qPCR. Total RNA extraction from ∼100 gastrulating embryos from maternal knockdown of CG10188 compared to {mata4-GAL-VP16} embryos was performed using the Direct-zol RNA miniprep kit (Zymo Research, R2050). Retro-transcription was performed with the Superscript IV VILO (Invitrogen, 11766050) according to the manufacturer’s protocol including a DNase I treatment to remove genomic DNA contamination. Real-time PCR was performed on a CFX96 QPCR detection system (Bio-RAD) using TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (Life technologies) with the following TaqMan probes, following classical TaqMan protocol:

-

•

CG10188: Dm01811075_m1 = probe located in E2 (exon 2-3 boundary, 1210 / GenBank NM_001273659, amplicon = 57bp).

-

•

RPl32: House-keeping gene reference: Dm02151827_g1: (exon 2-3 boundary, 377 / GenBank NM_001144655, amplicon = 72bp)

-

•

RPII140: House-keeping gene: Dm02134593_g1 (exon 2-3 boundary, 2347 / GenBank NM_001300394, amplicon = 78bp)

-

•

Act42A: House-keeping gene: Dm02362162_g1 (one exon, 1439 / GenBank NM_078901, amplicon = 108bp)

RT-qPCR conditions were as follows: 50° for 2min; 95° for 10min; 40 cycles [95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1min]. Analyses were performed in duplicate from three independent RNA preparations. Beforehand, the three house keeping genes (Rpl32, RPlII40 and Act42A) were compared to verify absence of any variation between samples (not shown). Transcript levels were first normalized to the house keeping gene RPI32; and then to the control group. ΔΔCq method was used to estimate relative amounts using the Bio-RAD CFX Maestro software.

Antibody generation

To generate specific antibodies for Gβ13F, peptides corresponding to the amino-terminal region and internal region of the Gβ13F protein were commercially synthesized and used to immunize rabbits (Eurogentec). The peptide sequences employed were as follows: MNELDSLRQEAESLK (aa 1-15) and CKQTFPGHESDINAVT (aa 218-233). Polyclonal anti-Gβ13F antibodies affinity purified against the immunizing peptide were then tested for specificity in western blots and immunostainings. Lysates from dechorionated embryos were prepared in 10 mM Tris/Cl pH 7.5; 150 mM NaCl; 0.5 mM EDTA; 0.5% NP-40 supplemented with HALT Protease/Phosphatase Inhibitor Mix (Life Technologies) and 0.2M PMSF (Sigma). Samples were denatured, reduced, separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. After blocking, blots were incubated with polyclonal antibody (2μg/mL) with or without preincubation of antibody with 200 μg/ml of immunizing/affinity purified peptide. A band of the expected molecular weight (43 kD) was present in the western blot and was abolished when the antibody was preincubated with the immunizing peptide. Similarly, the signal observed in subsequent immunofluorescence labelings was abolished when the antibody was preincubated with the immunizing peptide.

Immunofluorescence

Methanol-heat fixation [81] was used for embryos labeled with rabbit anti-Gβ13F (1:20, as described above), mouse anti-β catenin (1:100, DSHB), mouse anti-Neurotactin (1:50, DSHB). A chicken anti-GFP antibody (1:1000, Aves Labs) was used in embryos expressing GFP:: Dp114RhoGEF to amplify the signal in fixed embryos. Secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) were used at 1:500. Fixed samples (using Aqua-Poly mount, Polysciences) were imaged under a confocal microscope (LSM 780, Carl Zeiss) using a Plan Apochromat 40x/1.4 NA oil immersion objective.

Bright field imaging

Standard techniques were used to immobilize embryos for imaging. Bright-field time-lapse images were collected on an inverted microscope (Zeiss) and a programmable motorized stage to record different positions over time (Mark&Find module from Zeiss). The system was run with AxioVision software (Zeiss) and allowed the acquisition of time-lapse datasets in wild-type or mutant embryos. Images were acquired every 2 min for 40 min post dorsal movement of the posterior pole cells. The extent of elongation was measured by tracking the distance between the pole cells and the posterior pole at each time point and normalized to the total length of the embryo.

Embryo viability test

40 freshly hatched females and males were incubated at 25°C for 4 days in each experimental conditions (Control, Dp114RhoGEF shRNA and Dp114RhoGEF shRNA, Sqh-Dp114RhoGEF shRNAR). For egg collection, flies were given a fresh apple juice agar plate to lay eggs for 4 hours. Eggs were then counted and incubated at 25°C for 2 days. The total number of emerging larva was counted and plotted in percentage as a function of viability.

Embryo injection

Microtubule depolymerization was carried out by injecting Colcemid (500μg/ml in water, 234109-M, Merck) in y[∗] w[67c23] or EndoCad::GFP, Sqh::mCh embryos during the fast phase of cellularization. Subsequently, embryos were filmed at the onset of germ-band extension on a Nikon Roper spinning disc Eclipse Ti inverted microscope using a 100X_1.4 N.A. oil-immersion objective or on a Zeiss inverted bright field microscope.

Image acquisition

Embryos were prepared as described before [46]. Timelapse imaging was done from stage 6 during 15 to 30 min depending on the experiment, on a Nikon Roper spinning disc Eclipse Ti inverted microscope using a 100X_1.4 N.A. oil-immersion objective or a 40X _1.25 N.A. water-immersion (for cell-intercalation measurement) at 22°C. The system acquires images using the Meta-Morph software. For medial and junctional intensity measurements, 10 to 18 Z sections (depending on the experimental conditions), 0.5μm each, were acquired every 15 s. Laser power was measured and kept constant across all experiments.

Image analysis

All image processing was done in imageJ/Fiji free software. For all quantifications for medial and junctional Rho1-GTP and Myo-II, maximum-intensity z-projection of slices was used, followed by a first background subtraction using the rolling ball tool (radius 50 pixels∼4μm) and a second subtraction where mean cytoplasmic intensity value measured on the projected stack was subtracted to the same image. Cell outlines were extracted from spinning disk confocal images of Ecad::GFP or Rho1-GTP using the Tissue Analyzer software [79] from B.Aigouy (IBDM, France). The Ecad-GFP resulting outlines were then dilated by 2 pixels on either side of the junction (5-pixel-wide lines) and used as a junctional mask on the MyoII::mCherry channel. Medial-apical area was obtained by shrinking individual cell mask by 4 pixels to exclude any contribution of junctional signal (ImageJ/Fiji macro from G. Kale [8], COS Heidelberg). Medial and junctional Myo-II and Rho1-GTP values were mean intensities calculated in these two non-overlapping cell areas.

For planar polarity analysis, junctional masks described previously were used to extract for each junction the mean pixel intensity and orientation. Intensities were averaged for all junctions in each angular range. Amplitude of polarity was then calculated as a ratio between signal intensity measured at vertical junctions (75-90° angular range) over intensity measured at transverse junctions (0-15° angular range).

To measure the number of T1 transitions, Tissue Analyzer software. Segmentation was automatically performed on Utr::GFP channel by the plugin and corrected by the experimenter. Tracked cells present in the field of view during a period of 10min were then analyzed for T1 events. T1 events were automatically detected by the plugin and checked manually to prevent false detections.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Statistics

Errors bars are SEM unless otherwise indicated. Statistical significance was determined and P values calculated with a non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test or a Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test in OriginPro9. The experiments were not randomized, and the investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Data and Code Availability

This study did not generate new datasets and code.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to N. Fuse (Kyoto, Japan), F. Matsuzaki (RIKEN, Japan), A. Martin (MIT, USA), J. Großhans (Institut of Developmental Biochemistry Göttingen, Germany), S. Kerridge (IBDM, France), the Drosophila Genetic Resource Center, and the Bloomington Stock Center for the gift of flies. We thank the TRiP at Harvard Medical School (NIH/NIGMS R01-GM084947) for providing transgenic RNAi fly stocks used in this study. We thank members of the Lecuit group and C.P. Toret (IBDM, France) for stimulating discussions and comments during the course of this project and writing of this manuscript. We thank B. Dehapiot (IBDM, France), G. Kale (COS, Heidelberg), and C. Collinet (IBDM, France) for help with cell segmentation and/or tracking and image processing. This work was supported by a grant from the ERC (Biomecamorph no. 323027) and the Ligue Natiuonale Contre le Cancer (Equipe Labellisée 2018). A.G.D.L.B. was supported by the Ministère de l’Enseignement supérieur, de la Recherche et de l’Innovation and the Fondation Bettencourt Schueller. We also acknowledge the France-BioImaging infrastructure supported by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-10-INSB-04-01; call “Investissements d’Avenir”).

Author Contributions

A.G.D.L.B. and T.L. conceived the project and analyzed the data. A.G.D.L.B. performed all the experiments and data analysis except for Figure S6A, which was performed by A.C.L. J.-M.P. made all the constructs and performed all cloning and molecular characterization. A.G.D.L.B. and T.L. wrote the paper. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: September 12, 2019

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.08.017.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Martin A.C., Goldstein B. Apical constriction: themes and variations on a cellular mechanism driving morphogenesis. Development. 2014;141:1987–1998. doi: 10.1242/dev.102228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorfinkiel N., Blanchard G.B. Dynamics of actomyosin contractile activity during epithelial morphogenesis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2011;23:531–539. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munjal A., Lecuit T. Actomyosin networks and tissue morphogenesis. Development. 2014;141:1789–1793. doi: 10.1242/dev.091645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lecuit T., Lenne P.F. Cell surface mechanics and the control of cell shape, tissue patterns and morphogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:633–644. doi: 10.1038/nrm2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collinet C., Lecuit T. Stability and dynamics of cell-cell junctions. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2013;116:25–47. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394311-8.00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heisenberg C.P., Bellaïche Y. Forces in tissue morphogenesis and patterning. Cell. 2013;153:948–962. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Priya R., Yap A.S. Active tension: the role of cadherin adhesion and signaling in generating junctional contractility. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2015;112:65–102. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2014.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kale G.R., Yang X., Philippe J.M., Mani M., Lenne P.F., Lecuit T. Distinct contributions of tensile and shear stress on E-cadherin levels during morphogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:5021. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07448-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Streichan S.J., Lefebvre M.F., Noll N., Wieschaus E.F., Shraiman B.I. Global morphogenetic flow is accurately predicted by the spatial distribution of myosin motors. eLife. 2018;7 doi: 10.7554/eLife.27454. e27454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]