Abstract

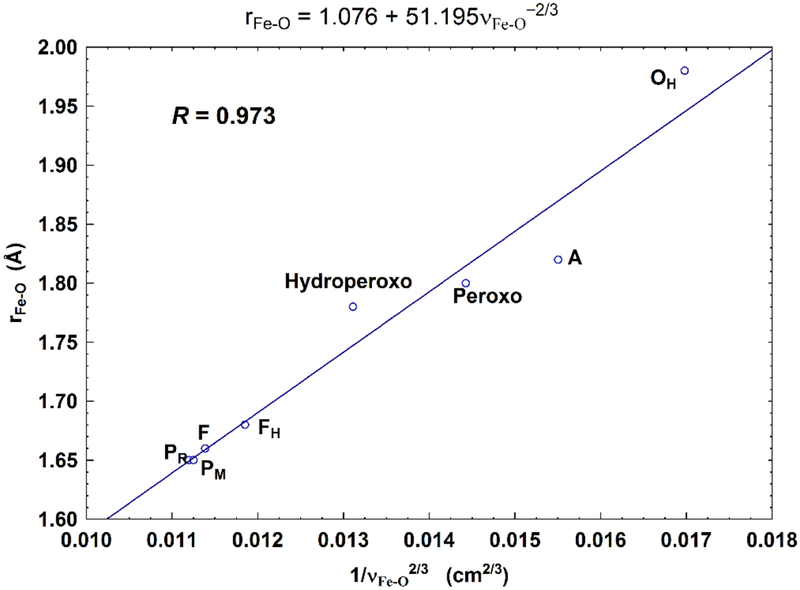

Density functional vibrational frequency calculations have been performed on eight geometry optimized cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) dinuclear center (DNC) reaction cycle intermediates and on the oxymyoglobin (oxyMb) active site. The calculated Fe-O and O-O stretching modes and their frequency shifts along the reaction cycle have been compared with the available resonance Raman (rR) measurements. The calculations support the proposal that in state A[Fea33+-O2−•⋯CuB+] of CcO, O2 binds with Fea32+ in a similar bent end-on geometry to that in oxyMb. The calculations show that the observed 20 cm−1 shift of the Fea3-O stretching mode from state PR to F is caused by the protonation of the OH− ligand on CuB2+ (PR[Fea34+=O2−⋯HO−-CuB2+] → F[Fea34+=O2−⋯H2O-CuB2+]), and that the H2O ligand is still on the CuB2+ site in the rR identified F[Fea34+=O2−⋯H2O-CuB2+] state. Further, the observed rR band at 356 cm−1 between states PR and F is likely an O-Fea3-porphyrin bending mode. The observed 450 cm−1 low Fea3-O frequency mode for the OH active oxidized state has been reproduced by our calculations on a nearly symmetrically bridged Fea33+-OH-CuB2+ structure with a relatively long Fea3-O distance near 2 Å. Based on Badger’s rule, the calculated Fea3-O distances correlate well with the calculated νFe-O−2/3 (νFe-O is the Fea3-O stretching frequency) with correlation coefficient R = 0.973.

1. Introduction

As the terminal oxidase of cell respiration, cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) reduces O2 to H2O and pumps protons across the membrane to create the chemiosmotic proton gradient used by ATP synthase to synthesize ATP.1–4 Because of its important biological function, CcO has been extensively studied, and the overall structure of the molecule and several important intermediate states of the reaction cycle are established.5 X-ray crystallographic studies are critical in locating the redox-active sites and possible transport pathways for protons, molecular oxygen, and electrons in CcO.6–16 The catalytic site of CcO which binds and reduces O2 by 4e−/4H+ transfer contains a heme a3 (Fea3) and a Cu ion (CuB). Fea3 and CuB are close to each other (~5 Å). This Fea3-CuB active site is usually called the dinuclear (or binuclear) center/complex (DNC or BNC). Two other redox centers are also present in CcO. One is a homodinuclear Cu dimer (2CuA) which serves as the initial site of electron entry to CcO,17,18 and the other is also a heme, which is heme A (Fea) in the case of aa3 type of CcO, or heme B (Feb) in ba3 type of CcO. Electrons transfer from cytochrome c to CuA, then on to heme A/B, and from there to the DNC Fea3-CuB.19,20 The DNC structures of aa3 and ba3 oxidases are nearly identical. Because of their considerable structural and functional similarities, these two types of enzymes probably have a common mechanism of O2 reduction.4

Briefly, the iron in the Fea3 site is coordinated to heme and an axial histidine ligand (His384, residue numbers in this paper are by default for ba3 CcO from Thermus thermophilus (Tt)), while the copper in the CuB site is coordinated to three histidine ligands: His233, His282, and His283. His233 covalently links with the Tyr237 side chain. This linkage is common to all CcO’s but otherwise unknown in metalloenzymes. This unique cross-linked tyrosine residue takes an important role in the processes of electron/proton transfer in CcO. The oxidation, spin, and ligation states of the Fea3 and CuB sites change during the catalytic cycle.

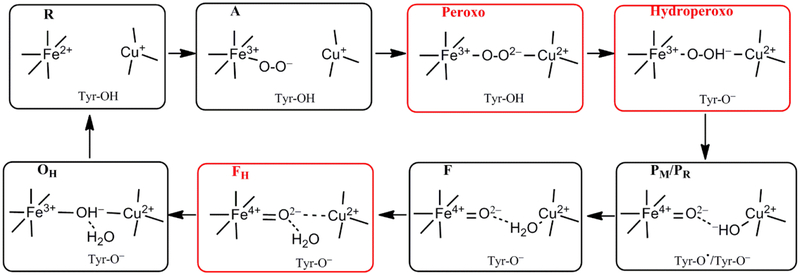

Starting from the binding of O2 with the reduced (R) DNC, several catalytic intermediates have been well characterized by resonance Raman (rR) studies21–25 (see Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Feasible intermediate states of the DNC in the catalytic cycle, in which A, PM/PR, F, and OH were identified by resonance Raman (RR) experiments, and their DNC’s are likely in the forms presented above. Although the Peroxo, Hydroperoxo, and FH states (drawn in red frames) were not observed experimentally, they may exist for a short time and will also be studied in the current paper.

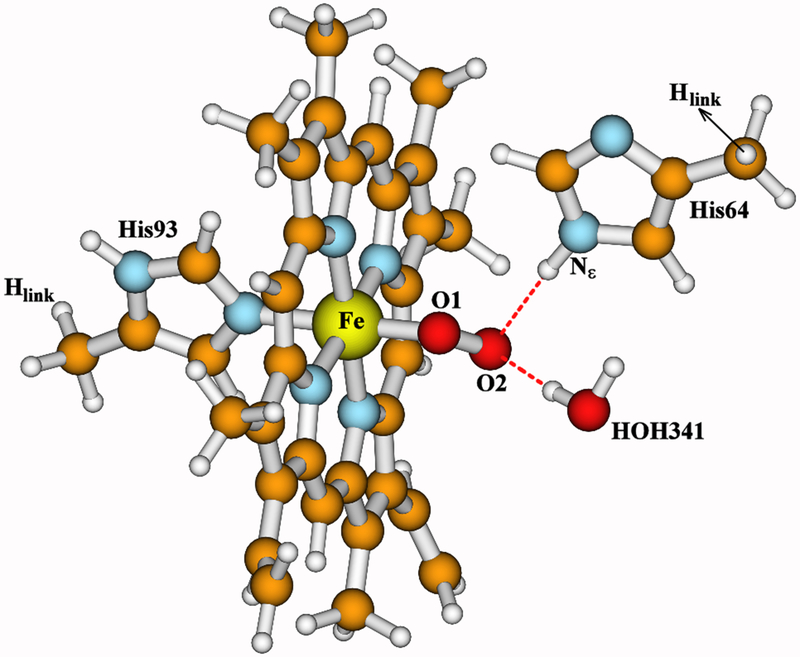

(1) State A. State A is formed when molecular O2 binds with Fea32+, and the DNC is formally in the Fea33+-O2−•⋯CuB+ state.5,22,26 This A-intermediate was identified by an Fea3-O2 stretching mode at ~571 cm−1 in rR measurements.5,21–25,27 Since this band is located at nearly the same wavenumber position of oxymyoglobin (oxyMb) (569-572 cm−1),28–30 and since O2 binds with Fe2+ in a bent end-on position in the X-ray crystal structures of oxyMb (see Figure 2),29,31,32 it has been proposed that O2 also binds with Fea32+ in a similar bent end-on geometry in CcO (see Figure 3 for our DNC model of state A).

Figure 2.

Active site model of oxymyoglobin (oxyMb), built from the X-ray crystal structure 1MBO and geometry optimized using OLYP-D3-BJ functional within COSMO solvation model.31

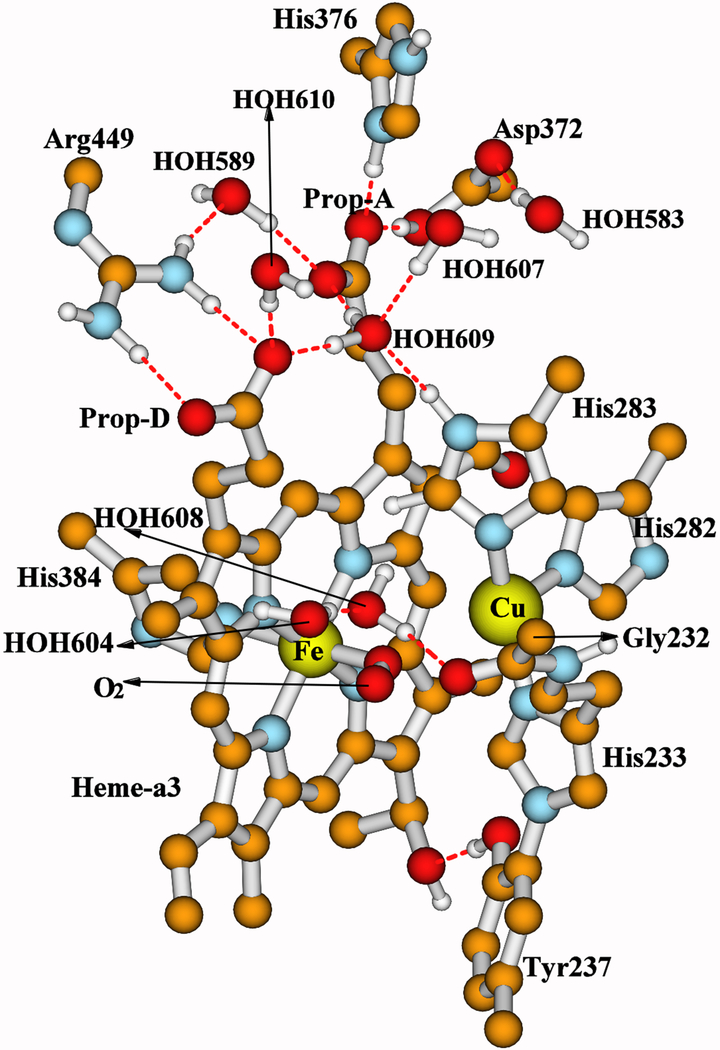

Figure 3.

Our whole quantum cluster model for state A of the DNC, built from the X-ray crystal structure 3S8G of ba3 CcO from Thermus thermophilus (Tt).16 For more visibility, some apolar or link H atoms are not shown on the picture. A full picture (Figure S1) with all the H atoms is given in the Supporting Information. A clearer view for both the central Fea33+−O2−•⋯CuB+ portion and the top cluster of the model are given in Figure 4.

(2) State P. This state is not a peroxide-containing compound (as implied in the notation), but one in which the dioxygen O-O bond has already been cleaved.33–37 Four electrons need to transfer to O2 for the O-O bond cleavage. It is well established that, among the four electrons, two are from the Fea3 site (Fea32+ → Fea34+) and one is from CuB (CuB+ → CuB2+). Experiments starting from the mixed valence state (2CuA1.5+,Fea,b3+,Fea32+,CuB+)38–40 show that the 4th electron originates from the unique cross-linked tyrosine (Tyr-O− → Tyr-O• radical).41,42 The P state obtained this way is called PM, which can be represented as [Fea34+=O2−, OH−-CuB2+, Tyr-O•]. When the O2 binding starts from the fully reduced enzyme (2CuA+,Fea,b2+,Fea32+,CuB+), an electron would be transferred from heme A/B, and the P-intermediate is called PR[Fea34+=O2−⋯HO−-CuB2+, Tyr-O−].40 The Fe4+=O2− stretching mode of the PM intermediate was identified at ~804 cm−1 by rR measurements.5,27,36,43–45 The optical spectrum of PR was found similar or identical to the spectrum of the PM intermediate.40

Although no stable intermediates between A and P are observed, it is generally believed that the bridging ferric-peroxo [Fea33+-O22−-CuB2+, Tyr-OH] and ferric-hydroperoxo [Fea33+-(O2H)−-CuB2+, Tyr-O−] states have to be formed before the O-O bond cleavage, and the proton in the bridging OOH− originates from the unique cross-linked tyrosine.2,46 Our recent broken-symmetry47–49 density functional theory (DFT) calculations have shown that the O-O bond breaking energy barrier in the transition of [Fea33+-(O-OH)−-CuB2+, Tyr-O−] → [Fea34+=O2−⋯HO−-CuB2+, Tyr-O•] is very small (less than 3.0/2.0 kcal mol−1 in PW91-D3/OLYP-D350–53 calculations).54

(3) State F is the next identified intermediate with the Fea34+=O2− stretching mode at ~785 cm−1.5,27,36,44,55–58 F differs from PR by an additional proton.2,40,59,60 The observed EPR spectra for PR and F are very different.40 Hansson et al.38 showed that, the copper hyperfine lines of the unique EPR signal of the PR intermediate were broadened when 17O2 was used as oxidant, and the broadening was consistent with bonding of one of the two oxygen atoms as an OH− ligand of CuB2+. Morgan et al.40 supported this proposal and further suggested that, in F, the copper OH− ligand may have been protonated to water, allowing for strong hydrogen bonding and exchange coupling between the Fea34+ and CuB2+ sites. Therefore, it is usually modeled that the CuB site has an OH− ligand in PM/PR[Fea34+=O2−⋯HO−-CuB2+, Tyr-O•/Tyr-O−], and an H2O ligand in F[Fea34+=O2−⋯H2O-CuB2+, Tyr-O−].27,59

Sharma et al. have proposed that the water ligand in F likely dissociates from the copper (they call the state FH).60 However, the FH state they obtained from their DFT calculations has higher energy than the prior state with the H2O ligand on CuB.60 Very recently, we have also found in our DFT calculations that, the DNC structure of F[Fea34+=O2−⋯H2O-CuB2+, Tyr-O−] (labeled as Fea34+=O2−⋯H2O-CuB2+-Y237−-H376+-M2in Ref. 61) has more CuB+-Tyr-O• character and therefore has a relatively long CuB-O distance (2.26 Å). When purposely moving the H2O ligand away from the CuB site (the H2O still H-bonds with O2−), we have found a lower-energy (by 6 kcal mol−1) structure (Fea34+=O2−⋯CuB2+-Y237−-H376+-M3 in Ref. 61), in which the CuB2+⋯O2− (ferryl-oxygen) distance is only around 2.4 Å. We therefore have also proposed that the H2O ligand has dissociated from CuB in state F.61 However, anticipating later results, in Section 3.2 we will show from our vibrational frequency calculations that the H2O ligand still binds with CuB2+ in the rR identified F state. The H2O-dissociated F structure will also be called “FH” hereafter (see Figure 1).

(4) A rR band at 356 cm−1 was observed and was suggested to be the His-Fea34+=O2− bending mode for a DNC structure between states PR and F.5,62,63

(5) Next, a very important activated oxidized Fea33+⋯CuB2+ state beyond state F, which is called OH, has been identified with a high-spin Fea33+ and with the Fea33+-OH− stretching mode at 450 cm−1.56 Such a stretching frequency is very low with respect to other hydroxide bound heme species.27 Therefore, it has been suggested that there is a strong H-bond to the oxygen atom of the heme-bound hydroxide, thereby weakening the Fea3-O bond and generating a high-spin configuration.27 However, a feasible alternative is that the OH state has a bridging OH− in the Fea33+-OH−-CuB2+ form.60,61,64 And since the O2− ligand already bridges the two metal sites in FH, once the FH state is formed, the OH state with bridging OH− is readily formed upon one electron reduction and proton transfer to FH.

Although the intermediate states A, PM/PR, F, and OH mentioned above were identified well by rR measurements, the detailed DNC structures of these states are still not certain. In the current paper, we apply vibrational frequency calculations on our geometry optimized DNC structures for the intermediate states and compare the calculated Fea3-O2/Fea3-O vibrational frequencies and related frequency shifts with the available observed data from rR experiments.

2. Calculation Methods

The starting geometries of the model clusters for the DNC intermediate states are established based on the ba3 CcO X-ray crystal structure 3S8G.16 The calculation method for geometry optimizations using ADF65–67 is the same (broken-symmetry47–49/OLYP-D3-BJ68/TZP/DZP plus COSMO69–72 solvation model) as in our recent publication,61 and the geometry optimized structures of states PR(Fea34+=O2−⋯HO−-CuB2+, Tyr-O−), F(Fea34+=O2−⋯H2O-CuB2+, Tyr-O−), FH(Fea34+=O2−⋯CuB2+, Tyr-O−), and OH[Fea33+-OH−-CuB2+, Tyr-O−] are directly taken from Ref. 61 for vibrational frequency calculations in the current paper. More details of our geometry optimization and vibrational frequency calculation methods can be found in Supporting Information.

For comparison, both analytical and numerical vibrational frequency calculations are then performed at the optimized geometries. For each DNC intermediate structure, we compute a partial Hessian (~110 atoms) in analytical frequency calculations, in which all the methyl groups and the atoms in the upper cluster (Arg449, His376, Asp372, HOH583, HOH589, HOH607, HOH610, and the shifted waters HOH604 and HOH608 in states F, FH, and OH) are excluded from Hessian calculations. In numerical frequency calculations, we applied the mobile block Hessian (MBH) approach built in ADF,73,74 in which the following groups were treated as individual mobile blocks: each methyl group in the model cluster, each residue side chain of Arg449, His376, and Asp372, and each of the water molecules which are also excluded from analytical Hessian calculations mentioned above. In the MBH method, each mobile block (for example, a methyl group or a water molecule) is treated as a rigid block, which moves as a whole and has only six frequencies related to its rigid motions. We will first apply the analytical full/partial Hessian and numerical full/MB Hessian vibrational frequency calculations at the fully/partially optimized geometries of the oxyMb active site model (Figure 2) to establish the accuracy of these different approaches for the Fe-O/O-O stretching modes.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Calculations on the OxyMb Active Site

Our active site model of oxyMb is taken from the X-ray crystal structure 1MBO (1.6 Å resolution).31 The molecular oxygen (O1-O2) H-bonds with the −NεH group of the distal His64 side chain.32 A water molecule HOH341 found near the O2 atom in 1MBO is also included in our model. Overall, our model includes the heme Fe atom, the molecular oxygen (O1-O2), the porphyrin with truncated propionate groups, the water molecule HOH341, and the side chains of His93 and His64 in which each Cα atom is replaced by an Hlink atom. To compare different geometry optimization and vibrational frequency calculation methods, we have performed the following calculations at the oxyMb model: 1) Similar to the DNC model calculations, the geometry of the oxyMb active site model is partially optimized with the positions of the Hlink atoms on His93 and His64 fixed (Hlink-Fixed). 2) The geometry of this model is fully optimized (Full-Opt) without any constraint. 3) Analytical full-Hessian (Anal. Full-H) vibrational frequency calculations are performed at the two optimized geometries. 4) Analytical partial-Hessian (Anal. Partial-H) vibrational frequency calculations are performed at the two optimized geometries, in which the atoms in all the methyl groups are excluded from the Hessian calculations. 5) Numerical full-Hessian (Num. Full-H) frequency calculations are performed. And 6) numerical MBH calculations are applied at the two optimized geometries, where each methyl group is treated as a rigid mobile block (MB).

The calculated broken-symmetry (BS) state relative energies, the main geometric and Mulliken net spin population properties of the two optimized geometries are given in Table 1. Whether the heme-oxygen complex in oxyMb or oxyhemoglobin is in the Fe2+-O2, or in the Fe3+-O2−• form, or in the mixture of both forms has a long history of discussion and investigation,75–78 and an extended discussion is not within the scope of the current paper. Briefly, the net spin results of our calculations show that the oxyMb complex is better described as in the Fe3+-O2−• state, in which the low-spin (LS) Fe3+ site antiferromagnetically (AF) coupled with the superoxide ion O2−•. The distance between O2 and the oxygen atom of HOH341 is only 1.47 Å in the X-ray crystal structure 1MBO, which is too short for H-bonding interaction. After DFT geometry optimizations, this distance is increased to 2.84-2.85 Å. The Full-geometry optimization yields a little lower energy (by 1.1 kcal mol−1) than the Hlink-Fixed geometry. Yet, the main bond lengths and angles in the Fe-O2 center of the two optimized geometries are nearly the same.

Table 1 .

DFT OLYP-D3-BJ Calculated Geometric and Mulliken Net Spin Properties of the Active Site of OxyMb (Figure 2).a

| Geometry (Å, degree) |

ΔEBS b | Net Spin c |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe-N(H93) | Fe-O1 | O1-O2 | ∠FeO1O2 | O2⋯Nε(H64) | O2⋯O341 | Fe | O1 | O2 | ||

| Hlink-Fixed d | 2.01 | 1.79 | 1.32 | 117.7 | 2.85 | 2.85 | 0.0 | 0.71 | −0.32 | −0.40 |

| Full-Opt. e | 2.02 | 1.80 | 1.32 | 117.3 | 2.87 | 2.84 | −1.1 | 0.73 | −0.33 | −0.41 |

| Exp. | 2.07 | 1.83 | 1.21 | 115.6 | 2.77 | 1.47 | ||||

The initial geometry of the oxymyoglobin (oxyMb) active site model cluster is taken from the X-ray crystal structure 1MBO,31 which is also given here as the experimental (Exp.) data for comparison.

Relative calculated broken-symmetry state energies in kcal mol−1.

The Mulliken net spin populations (number of unpaired electrons) on Fe, O1, and O2.

During geometry optimization, the positions of the Hlink atoms (replacing the Cα atoms) on His93 and His64 side chains are fixed.

The geometry of the model cluster is fully optimized without constraint.

Our calculated and experimentally observed Fe-O and O-O stretching modes are compared in Table 2. Overall, for this small oxyMb active site model, different vibrational frequency calculation methods yield very similar ν(Fe-O) (523 – 533 cm−1) and ν(O-O) (1083 – 1090 cm−1) frequencies. When focusing on the ν(Fe-O) calculated results at the two optimized geometries (Hlink-Fixed vs. Full-Opt), one can see that each calculation method yields almost the same frequencies (529 vs. 528 cm−1, 524 vs. 523 cm−1, 533 vs. 530 cm−1, and 531 vs. 529 cm−1 from the methods Anal. Full-H, Anal. Partial-H, Num. Full-H, and Num. MBH, respectively). Therefore, fixing the two Hlink atom positions during geometry optimization has little effect on the Fe-O bond length and the Fe-O stretching mode. Further, The ν(Fe-O) obtained from Anal. Partial-H calculation is different from the Anal. Full-H calculation by only 5 cm−1 for both geometries. And the Num. MBH calculated ν(Fe-O) (531 cm−1 for Hlink-Fixed geometry and 529 cm−1 for Full-Opt geometry) is almost the same as the corresponding Num. Full-H result (533 cm−1 for Hlink-Fixed geometry and 530 cm−1 for Full-Opt geometry). Therefore, excluding all the methyl groups or treating each methyl group as a mobile block in Hessian calculations in analytical or numerical vibrational frequency calculations also has little effect on the calculated Fe-O stretching mode in our oxyMb model. Similar conclusions can also be made for the O-O stretching mode calculations here.

Table 2.

DFT OLYP-D3-BJ Calculated and Experimentally (Exp.) Observed Fe-O and O-O Vibration Frequencies in the Active Site of OxyMb.a

| ν(Fe-O) (cm−1) d |

ν(O-O) (cm−1) d |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anal. Full-H | Anal. Partial-H | Num. Full-H | Num. MBH | Anal. Full-H | Anal. Partial-H | Num. Full-H | Num. MBH | |

| Hlink-Fixed b | 529 | 524 | 533 | 531 | 1083 | 1084 | 1087 | 1085 |

| Full-Opt. c | 528 | 523 | 530 | 529 | 1090 | 1089 | 1090 | 1088 |

| Exp. | 569,28 570,28 571,29 57230 | 1103 95 | ||||||

See Table 1 for geometrical properties.

During geometry optimization, the positions of the Hlink atoms (replacing the Cα atoms) on His93 and His64 side chains are fixed.

The geometry of the model cluster is fully optimized without constraint.

Frequency calculations are performed with four methods: (1) the exact full Hessian matrix is calculated analytically (Anal. Full-H); (2) the exact full Hessian matrix is calculated numerically (Num. Full-H); (3) a partial Hessian matrix excluding all methyl groups is calculated analytically (Anal. Partial-H); and (4) a Hessian matrix in which each methyl group is treated as a mobile block is calculated numerically (Num. MBH).

Comparing with the experimental data, our calculations underestimate the ν(Fe-O) frequency in average by ~43 cm−1, and underestimate the ν(O-O) mode by only ~17 cm−1. Other DFT functionals like BP86 may increase the calculation accuracy for the ν(Fe-O) mode by ~20 cm−1.79 However, it overestimates the ν(O-O) mode by ~100 cm−1.79 Therefore, when we compare our calculated Fe-O/O-O frequencies with the observed values, we will focus more on the relative calculated frequencies or frequency shifts than on the absolute frequencies. Next, we move on to the CcO DNC model calculations and will first compare if the calculated ν(Fe-O) frequency in state A is similar to the calculated results in oxyMb.

3.2. Calculations on the CcO DNC Models

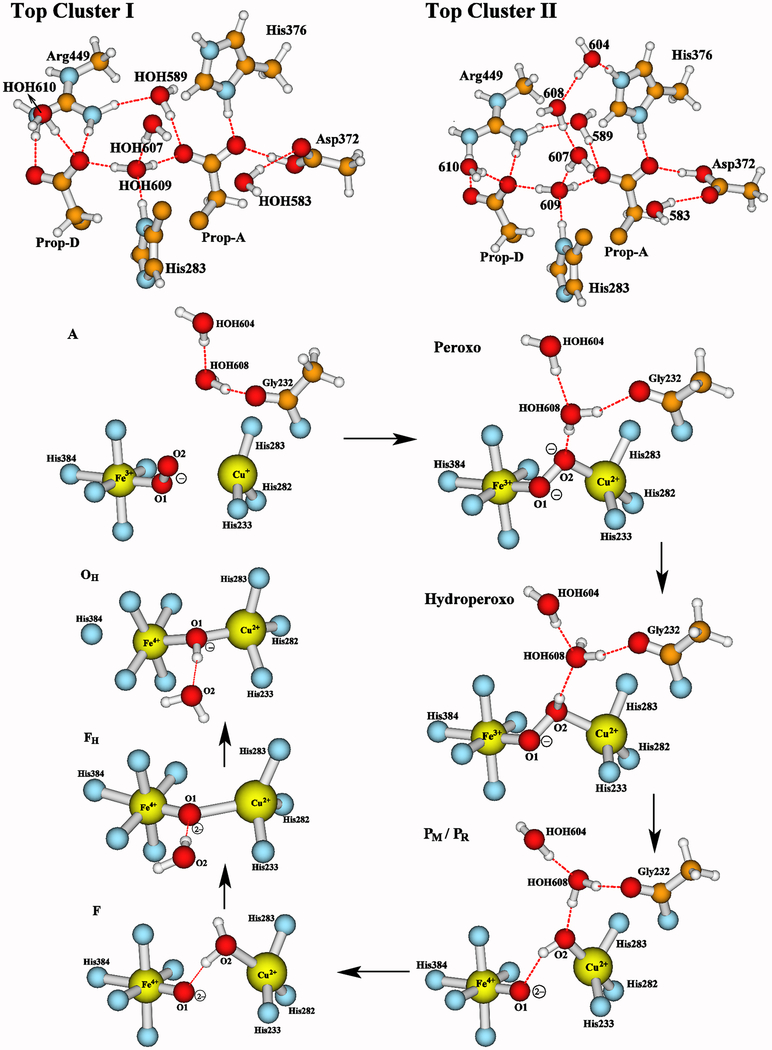

The detailed structures of the Fea3⋯CuB center and the locations of the two water molecules HOH604 and HOH608 (see the caption of Figure 4) change during the reaction cycle. However, the overall structure of each DNC cluster studied here is similar to the whole structure of state A shown in Figure 3. Therefore, for clarity, only the central and the top portions of the DNC cluster for each state are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

A closer look at the central and the top portions of the DNC model clusters studied here. Our recent calculations61 have shown that the two water molecules HOH604 and HOH608 found near the DNC in the X-ray crystal structure 3S8G are likely to shift to the top of the water cluster (see Top Cluster II) during the PR → F transition. Therefore, in A, Peroxo, Hydroperoxo, PM and PR states, these two water molecules are within the DNC and the top portion of each cluster with the H-bonding interactions is shown in “Top Cluster I”. In the following states F, FH, and OH, these two water molecules are shifted to the top of the cluster as shown in “Top Cluster II”. Our previous pKa calculations54,61 have indicated that the His376 side chain is likely in the cationic protonated state in these DNC clusters, and the Tyr237 side chain is in neutral protonated state in A and Peroxo intermediates, and in ionic deprotonated state in Hydroperoxo, PR, F, FH, and OH intermediates (the proton on the heme-a3 farnesyl hydroxyl group is rotated to have H-bonding interaction with the Tyr237− side chain). In PM, the Tyr237 side chain is in the Tyr237-O• radical state. The rest of each model is similar to what was shown in Figure 3.

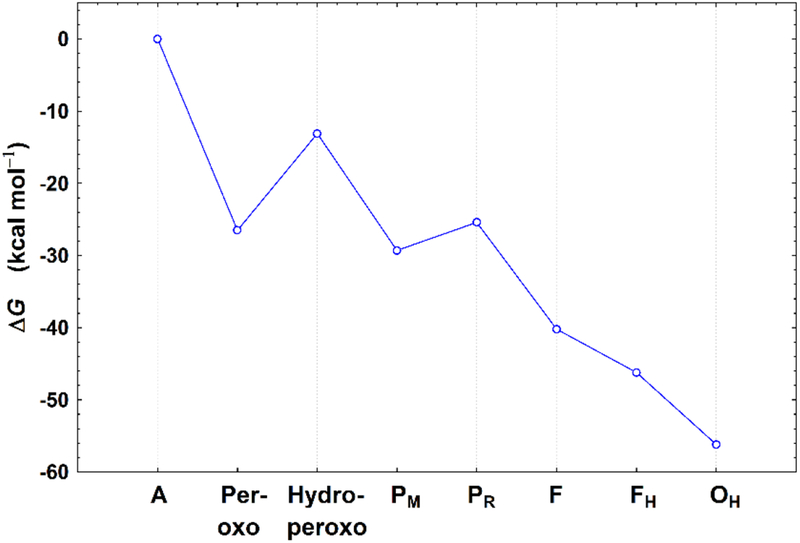

The calculated bond distances, the estimated relative free energies, and Mulliken net spin population properties of the optimized geometries for the A, Peroxo, Hydroperoxo, PM, PR, F, FH, and OH states are given in Table 3. The negative sign of the net spin on CuB indicates the spins of the Fea3 and CuB sites are antiferromagnetically (AF) coupled. Since the broken-symmetry state is a mixture of pure spin states,47–49 we have calculated the spin projection energy corrections80–82 for each state, and have estimated the free energy changes at pH = 7 with the corrections of the zero point energy differences (ΔZPE) and with the reference to a typical cytochrome c redox potential of E0 = +0.22 eV.61 The calculated spin projection corrections (ΔEcorr) range from −2.1 to 0.1 kcal mol−1 for the eight DNC states (see Table S1). The ΔG change from A → OH is shown in Figure 5. A detailed description of the spin-projection correction calculations and the analysis of the ΔG profile are given in the Supporting Information.

Table 3.

OLYP-D3-BJ Calculated Geometrical, Energetic, and net Spin Properties of the Optimized DNC Geometries in the Following Sates: A, Peroxo, Hydroperoxo, PM, PR, F, FH, and OH.

| State | Structure a | Geometry (Å) |

ΔG c | Q d | Net Spin e |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe-N(H384) | Fe-O1 | O1-O2 (O1⋯O2) | Cu-O b | Fe⋯Cu | Fea3 | O1 | O2 | CuB | Y237 | ||||

| A | Fea33+,LS-O2−•⋯-CuB+,Y-OH | 2.15 | 1.82 | 1.30 | 2.95 | 4.55 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.96 | −0.30 | −0.51 | −0.06 | 0.0 |

| Peroxo | Fea33+,LS-O22−-CuB2+,Y-OH | 2.12 | 1.80 | 1.37 | 1.94 | 3.88 | −26.5 | 1 | 0.74 | −0.02 | −0.21 | −0.34 | 0.0 |

| Hydroperoxo | Fea33+,LS-−OOH-CuB2+,Y-O− | 2.07 | 1.78 | 1.50 | 2.11 | 4.31 | −13.1 | 1 | 0.88 | 0.13 | −0.06 | −0.34 | −0.39 |

| PM | Fea34+,IS=O2−⋯HO−-CuB2+,Y-O• | 2.10 | 1.65 | 2.68 | 1.90 | 4.28 | −29.3 | 1 | 1.29 | 0.75 | −0.21 | −0.50 | −0.90 |

| PR | Fea34+,IS=O2−⋯HO−-CuB2+,Y-O− | 2.09 | 1.65 | 2.67 | 1.91 | 4.42 | −25.4 | 0 | 1.28 | 0.77 | −0.21 | −0.50 | 0.0 |

| F | Fea34+,IS=O2−⋯H2O-CuB2+,Y-O− | 2.10 | 1.66 | 2.52 | 2.26 | 4.58 | −40.2 | 1 | 1.37 | 0.69 | −0.01 | −0.36 | −0.41 |

| FH | Fea34+,IS=O2−⋯CuB2+,Y-O− | 2.15 | 1.68 | 2.40 | 3.81 | −46.2 | 1 | 1.37 | 0.67 | −0.22 | −0.59 | ||

| OH | Fea33+,HS-OH−-CuB2+,Y-O− | 2.43 | 1.98 | 1.99 | 3.58 | −56.2 | 1 | 4.02 | 0.13 | −0.37 | −0.25 | ||

LS stands for low-spin, IS is for intermediate-spin, and HS is for high-spin. In state A, the LS Fea33+ site is AF-coupled to the O2−• radical, and in other states given here, the Fea3 site AF-couples to the CuB site.

In states A, FH, and OH, this is the distance between CuB and O1 (see Figure 4). In other states, this is the CuB-O2 distance.

Calculated relative free energies at pH = 7 (kcal mol−1), including the spin-projection corrections to the broken-symmetry state energies, the zero-point energy differences, and with the reference to a typical cytochrome c redox potential of E0 = +0.22 eV (see details in Supporting Information).

The net charge of the model cluster.

The Mulliken net spin populations (number of unpaired electrons) on Fea3, O1, O2, and CuB, and on the heavy atoms of the Tyr237 (Y) side chain (the sum total).

Figure 5.

ΔG change from A → OH (see Supporting Information for detailed analysis).

The calculated vibrational Fea3-O and O-O stretching modes and the O-Fea3-Porphyrin bending modes in both Analytical partial-Hessian (Anal. Partial-H) and numerical mobile block Hessian (Num. MBH) methods are given in Table 4 and are compared with the available experimental data observed from rR frequency measurements.

Table 4.

Calculated Fea3-O and O-O Mayer Bond Orders (MBO) and Comparison of the Calculated and Observed (Exp) Vibrational Frequencies (cm−1) of the Fea3-O and O-O Stretching Modes and the O-Fea3-Porphyrin Bending Modes in CcO DNC Sates A, Peroxo, Hydroperoxo, PM, PR, F, FH, and OH.a

| State | Structure | Fe-O MBO | ν(Fe-O) |

O-O MBO | ν(O-O) or ν(O-Fe-Por) c |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anal. Partial-H | Num. MBH | Exp b | Anal. Partial-H | Num. MBH | Exp | ||||

| A | Fea33+,LS-O2−•⋯-CuB+,Y-OH | 0.480 | 518 | 520 | 57121−24 | 1.282 | 1142 | 1145 | 1159,d 1148e |

| Peroxo | Fea33+,LS-O22−-CuB2+,Y-OH | 0.544 | 577 | 584 | 1.063 | 906 | 907 | 870f | |

| Hydroperoxo | Fea33+,LS-−OOH-CuB2+,Y-O− | 0.586 | 666 | 672 | 0.911 | 664 | 673 | ||

| PM | Fea34+,IS=O2−⋯HO−-CuB2+,Y-O• | 1.191 | 838 | 830 | 80443−45 | 357 | 367 | ||

| PR | Fea34+,IS=O2−⋯HO−-CuB2+,Y-O− | 1.196 | 844 | 842 | 80440 | 378 | 372 | 356g | |

| F | Fea34+,IS=O2−⋯H2O-CuB2+,Y-O− | 1.144 | 823 | 822 | 78536,44,55–58 | 374 | 381 | 356g | |

| FH | Fea34+,IS=O2−⋯CuB2+,Y-O− | 1.118 | 775 | 774 | 375 | 396 | |||

| OH | Fea33+,HS-OH−-CuB2+,Y-O− | 0.518 | 452/458 | 471/476 | 45056 | ||||

Other calculated properties of these structures are given in Table 3. The vibrational frequencies were calculated with two methods: analytical frequency calculations with partial Hessian (Anal. Partial-H) and numerical frequency calculations with mobile block Hessian (Num. MBH).

Different groups21–24 reported a little different values of the Fea3-O stretch modes (cm−1) observed from resonance Raman (rR) experiments for a certain state. For simplicity, we only cite the commonly agreed values used in the review article of Ref. 5.

These are the O-O stretch modes for states A, Peroxo, and Hydroperoxo. For other states, these are the O-Fe-Porphyrin bending modes.

O-O stretching mode observed in a picket-fence oxyporphyrin.83

O-O stretching mode observed in a synthetic Fe3+-O22−-Cu2+ complex, which is structurally analogous to the Peroxo state of the DNC.86

For a certain structure, there can be multiple vibrational modes containing Fea3-O displacements. These modes are normally next to each other and are of very similar frequencies. The Fea3-O stretching frequencies reported here are those having the largest Fea3-O stretching displacements. Overall, the two calculation methods predicted similar frequencies for a certain vibrational mode. The largest difference yielded by the two calculation methods is ~20 cm−1 for the O-Fea3-Porphyrin bending mode in FH and the Fea3-O stretching mode in OH. For the rest of the vibrational modes given in Table 4, the differences between the two calculation methods are less than 10 cm−1. We will therefore focus on the data obtained from the Analytical partial-Hessian calculations in the following discussions.

Our calculated A state is best described as Fea33+-O2−•, in which the low-spin Fea33+ site AF-coupled with the superoxide ion O2−•, similar to the oxygen adduct in oxyMb. In state A, the calculated Fe-O distance is by 0.02/0.03 Å longer and the O-O distance is by 0.02 Å shorter than the corresponding calculated distances in oxyMb, likely because there are H-bonding interactions between O2−• and His64/HOH341 in oxyMb. As a result, the calculated ν(Fe-O) stretching mode in A (518 cm−1) is by ~10 cm−1 lower than the average (528 cm−1) of the calculated ν(Fe-O) in oxyMb. However, considering 10 cm−1 is only 2% of 528 cm−1, and different calculation methods on the oxyMb active site can yield up to 10 cm−1 difference for the ν(Fe-O) mode, we conclude that the calculated ν(Fe-O) in state A of CcO and in oxyMb are nearly the same. Further, the calculated ν(Fe-O) mode in the Peroxo state (577 cm−1) is considerably larger (by ~50 cm−1) than the ν(Fe-O) stretch frequency in oxyMb. Therefore, our calculations confirm that the experimentally observed state A of CcO is not in the peroxo state, but has a similar O2 end-on structure as in oxyMb.

There are no experimental data for the O-O stretching modes available for the DNC of CcO. However, our calculated ν(O-O) for the superoxide in state A (1142 cm−1) is very close to the observed O-O stretching mode 1159 cm−1 observed in a picket-fence oxyporphyrin83 and to the 1148 cm−1 observed in a cobalt-superoxide complex CoO2/Cu[NMePr]+.84,85 The O-O stretching mode in a synthetic Fe3+-O22−-Cu2+ complex that is structurally analogous to the Peroxo state of the DNC was reported by Adam et al. at 870 cm−1,86 which is reasonably close to our calculated ν(O-O) (906 cm−1) for the Peroxo state.

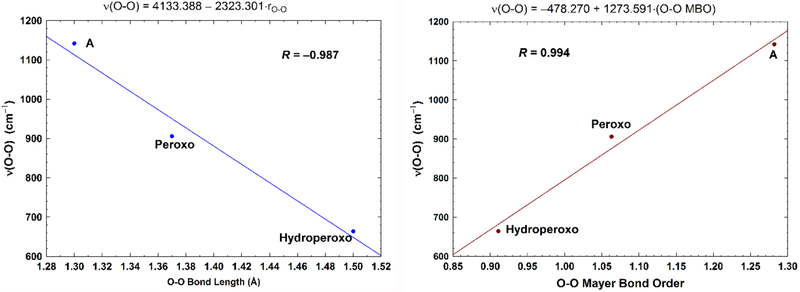

Further, we have calculated the Fea3-O and O-O Mayer bond orders (MBO)87 and have given the results in Table 4. Our calculated Mayer O-O bond orders for the superoxide in state A, the Peroxo state, and the Hydroperoxo state are 1.28, 1.06, and 0.91, respectively, which agree with the calculations by Cramer et al88 (on side-on bound metal-O2 complexes) very well, and are consistent with the increase of the corresponding Fea3-O bond orders (0.48, 0.54, and 0.59, respectively). Strong correlation has been shown between the O-O bond lengths/orders and the O-O stretching frequencies.88 We therefore also performed the linear regression between both the O-O bond length and bond orders vs. the O-O stretching frequencies, although for only three points. The correlation coefficients are near unity (in absolute value) in both fittings with R = −0.987 and R = 0.994, respectively (see Figure 6). Very recently, Dey’s group has also shown the linear correlation between Fe-O and O-O stretching frequencies in different superoxide adducts of porphyrins, heme enzymes, and in several model systems.89

Figure 6.

Left: Correlation between the calculated (using analytical partial-Hessian method) O-O stretching frequencies (ν(O-O), cm−1) and the O-O bond lengths (rO-O, Å). Very similar fitting is obtained with R = −0.985, when using the calculated frequencies obtained from the numerical-MBH method. Right: Correlation between the calculated (using analytical partial-Hessian method) O-O stretching frequencies (cm−1) and the Mayer O-O bond orders (MBO). Very similar fitting is also obtained with R = 0.995, when using the calculated frequencies obtained from the numerical-MBH method.

Experimentally it has been observed that the optical spectrum of PR is similar to or identical to the spectrum of the PM intermediate.40 Our calculations indeed yield very similar Fea3-O stretching frequencies in PR and PM (844 vs. 838 cm−1). From PR to F, rR measurements show that the ν(Fe-O) shifts from 804 cm−1 to 785 cm−1.5,27,36,44,55–58 This ~20 cm−1 shift was suggested being caused by the protonation of the copper OH− ligand in the transition of PR[Fea34+=O2−⋯HO−-CuB2+] → F [Fea34+=O2−⋯H2O-CuB2+].40 Our recent calculations have shown that the DNC of FH (see Figure 4) with the H2O ligand dissociating from the CuB2+ site yields lower-energy (by 6 kcal mol−1) than the F state with H2O ligand on CuB2+.61 Therefore we have proposed that the H2O ligand might have dissociated from CuB in state F.61 However, our current calculated ν(Fe-O) shift from PR (844 cm−1) to FH (775 cm−1) is ~70 cm−1, which is much larger than the observed value of ~20 cm−1. On the other hand, from PR to F (where the H2O ligand is still on CuB2+), our calculations yield 21 cm−1 ν(Fe-O) shift (844 cm−1 → 823 cm−1), which is in excellent agreement with the observed value. Therefore, our current vibrational frequency calculations support that state F is in the [Fea34+=O2−⋯H2O-CuB2+] structure, where the H2O ligand is still on the CuB2+ site. This does not exclude the existence of state FH. FH is possibly the precursor of OH, but with a very short life time. Experimentally, a low Fea3-O stretching frequency of 450 cm−1 was observed for state OH.56 Our calculations on the OH[Fea33+,HS-OH−-CuB2+, Tyr-O−] DNC structure reproduce this ν(Fe-O) frequency (452 cm−1) very well.

According to Badger’s rule (an empirical formula),90 the equilibrium internuclear distance r has linear correlation with 1/ν2/3, where ν is the vibrational frequency. To see how well this rule applies to our calculated unscaled Fea3-O bond lengths (rFe-O) and the ν(Fe-O) (or νFe-O) stretch frequencies, we performed linear regression of rFe-O vs. νFe-O−2/3 for the eight DNC models given in Table 3 and 4. The linear fitting is shown in Figure 7 with the correlation coefficient R = 0.973. Although some of the calculated ν(Fe-O) mode frequencies are off from the experimental data (overestimate for state A and underestimate for states PM/PR and F), overall our calculated Fea3-O stretching frequencies are reasonable, and are correlated with the Fea3-O bond length very well based on Badger’s rule.

Figure 7.

Correlation between the calculated Fea3-O bond lengths (rFe-O, Å) and the corresponding Fea3-O stretch frequencies (1/νFe-O2/3, based on Badger’s rule) for the eight DNC state structures studied in the current paper. The Fea3-O stretching frequencies (cm−1) are calculated using the analytical partial-Hessian method. Very similar fitting is obtained with R = 0.963, when using the calculated frequencies obtained from the numerical-MBH method.

Further, a rR band at 356 cm−1 was observed between states PR and F in the reaction between fully reduced CcO and O2.5,62,63 It has been proposed that this band is an His-Fea34+=O2− bending mode, caused by the distortion of the Fea34+=O2− bond from its ordinary upright structure (nearly perpendicular to the mean porphyrin plan).62 Our calculations show very similar vibrational frequencies (378 vs. 374 cm−1) in this region for PR and F, which involve mainly the displacement of O, Fea3, and the N atoms of the porphyrin ring. Therefore, the observed rR band at 356 cm−1 is likely an O-Fea3-porphyrin bending mode.

For iron-porphyrin complexes, several symmetric ligand vibrations have been identified especially in the ν4(~1330–1375 cm−1) and ν2(~1540–1575 cm−1) regions, which are correlated with the Fe oxidation and spin states (see Table 1 of Ref. 91).92–94 In particular, the ν4/ν2 marker bands for the Fe2+-OH2, L-Fe3+-OOH−, L-Fe4+=O2−, and the Fe3+-OH− intermediates produced during the oxygen-reducing process by an iron porphyrin are given as 1350/1540, 1349/1545, 1377/1574, and 1364/1555 cm−1, respectively.91 In our calculations, we found two major symmetric heme-a3 ligand vibrational bands in each of the ν4 and ν2 regions for each of the DNC intermediates. These ν4/ν2 calculated frequencies are A(1358,1381 cm−1)/(1532,1574 cm−1), Peroxo(1361,1380 cm−1)/(1536,1572 cm−1), Hydroperoxo(1368,1380 cm−1)/(1534,1571 cm−1), PM(1365,1385 cm−1)/(1532,1569 cm−1), PR(1367,1384 cm−1)/(1531,1571 cm−1), F(1367,1379 cm−1)/(1533,1570 cm−1), FH(1368,1380 cm−1)/(1536,1575 cm−1), and OH(1361,1376 cm−1)/(1521,1576 cm−1). However, we do not know which combinations of the ν4/ν2 bands can be observed without calculating the rR intensities.

4. Conclusions

Resonance Raman (rR) analyses have been extensively applied to the studies of the reaction between CcO and O2.5 Although the detailed dinuclear center (DNC) intermediate structures during the reaction cycle may not be drawn directly from these experiments, the isotope-sensitive rR bands, especially the Fea3-O stretching bands and their changes obtained during the O2-reduction process have provided very insightful information about the structures and the oxidation states of the DNC of CcO. In the current paper, we have performed vibrational frequency calculations at eight DNC intermediate model clusters, and have compared the calculated Fea3-O and O-O stretching modes and their shifts with the available rR measurements. Similar calculations have also been performed on the active site model of oxymyoglobin (oxyMb), which has been well characterized experimentally, in order to establish the accuracy of the different calculation methods.

The eight DNC states we have studied here are: A[Fea33+-O2−•⋯CuB+, Tyr-OH], Peroxo[Fea33+-O22−-CuB2+, Tyr-OH], Hydroperoxo[Fea33+-(O2H)−-CuB2+, Tyr-O−], PM[Fea34+=O2−⋯OH−-CuB2+, Tyr-O•], PR[Fea34+=O2−⋯OH−-CuB2+, Tyr-O−], F[Fea34+=O2−⋯H2O-CuB2+, Tyr-O−], FH[Fea34+=O2−⋯CuB2+, Tyr-O−], and OH[Fea33+-OH−-CuB2+, Tyr-O−].

The following conclusions have been drawn from our current calculations: 1) Our calculated Fe-O stretching frequencies in state A[Fea33+-O2−•⋯CuB+] (with an end-on O2 binding geometry) of the CcO DNC and in the active site model of oxyMb are very close to each other, which is consistent with what was observed from the rR experiments, and which supports that O2 binds with Fea32+ in CcO in a similar bent end-on geometry as in oxyMb. 2) The calculated O-O bond lengths and bond orders correlate well with the O-O stretching frequencies. 3) Our calculated Fea3-O distances (rFe-O) also correlate very well with νFe-O−2/3 (νFe-O are the calculated Fea3-O stretching frequencies) for the eight intermediate structures studied here. Therefore, Badger’s rule can be applied to the correlation between rFe-O and νFe-O. 4) Our calculations yield ~20 cm−1 shift for the Fea3-O stretching mode from state PR[Fea34+=O2−⋯OH−-CuB2+] to F[Fea34+=O2−⋯H2O-CuB2+]. This predicted frequency shift is in excellent agreement with rR experiment. Therefore, it is highly likely that the H2O ligand is still on the CuB2+ site in state F. The FH state (previously we have proposed it to be the F state),61 where the H2O ligand has dissociated from the CuB2+ site, is likely not the state F identified by rR experiment. However, our calculations do not exclude the existence of the FH state. The FH intermediate is possibly formed before the OH state with a very short lifetime. 5) Our calculations show that the observed rR band at 356 cm−1 between states PR and F is likely an O-Fea3-porphyrin bending mode. And 6) the low Fea3-O frequency near 450 cm−1, both observed by rR and calculated by DFT for state OH (the active oxidized state), is as expected for a nearly symmetrically bridged Fea33+-OH-CuB2+ structure with a relatively long Fea3-O distance near 2 Å. Finally, our calculations can aid future experiments in identifying the intermediate states peroxo, hydroperoxo, and FH.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank NIH for financial support (R01 GM100934) and thank The Scripps Research Institute for computational resources. This work also used the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by National Science Foundation (grant number ACI-1053575, resources at the San Diego Supercomputer Center through award TG-CHE130010 to AWG).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The detailed calculation methods, the full picture of Figure 3, the spin projection calculations for correcting the broken-symmetry state energies, the analysis of the energy profile shown in Figure 5, and the Cartesian coordinates of the eight optimized DNC clusters studied here are given as supporting information.

References

- (1).Wikström M Active Site Intermediates in the Reduction of O2 by Cytochrome Oxidase, and Their Derivatives. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1817, 468–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Kaila VRI; Verkhovsky MI; Wikström M Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer in Cytochrome Oxidase. Chem. Rev 2010, 110, 7062–7081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Konstantinov AA Cytochrome c Oxidase: Intermediates of the Catalytic Cycle and Their Energy-Coupled Interconversion. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 630–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).von Ballmoos C; Adelroth P; Gennis RB; Brzezinski P Proton Transfer in ba3 Cytochrome c Oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg 2012, 1817, 650–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Yoshikawa S; Shimada A Reaction Mechanism of Cytochrome c Oxidase. Chem. Rev 2015, 115, 1936–1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Iwata S; Ostermeier C; Ludwig B; Michel H Structure at 2.8 Å Resolution of Cytochrome c Oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans. Nature 1995, 376, 660–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Qin L; Hiser C; Mulichak A; Garavito RM; Ferguson-Miller S Identification of Conserved Lipid/Detergent-Binding Sites in A High-Resolution Structure of the Membrane Protein Cytochrome c Oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2006, 103, 16117–16122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Ostermeier C; Harrenga A; Ermler U; Michel H Structure at 2.7 Å Resolution of the Paracoccus denitrificans Two-Subunit Cytochrome c Oxidase Complexed with an Antibody FV Fragment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1997, 94, 10547–10553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Tsukihara T; Aoyama H; Yamashita E; Tomizaki T; Yamaguchi H; Shinzawa-Itoh K; Nakashima R; Yaono R; Yoshikawa S The Whole Structure of the 13-Subunit Oxidized Cytochrome c Oxidase at 2.8 Å. Science 1996, 272, 1136–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Svensson-Ek M; Abramson J; Larsson G; Tornroth S; Brzezinski P; Iwata S The X-Ray Crystal Structures of Wild-Type and EQ(I-286) Mutant Cytochrome c Oxidases from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Mol. Biol 2002, 321, 329–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Soulimane T; Buse G; Bourenkov GP; Bartunik HD; Huber R; Than ME Structure and Mechanism of the Aberrant ba3 Cytochrome c Oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 1766–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Hunsicker-Wang LM; Pacoma RL; Chen Y; Fee JA; Stout CD A Novel Cryoprotection Scheme for Enhancing the Diffraction of Crystals of Recombinant Cytochrome ba3 Oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D. Biol. Crystallogr 2005, 61, 340–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Koepke J; Olkhova E; Angerer H; Muller H; Peng GH; Michel H High Resolution Crystal Structure of Paracoccus denitrificans Cytochrome c Oxidase: New Insights into the Active Site and the Proton Transfer Pathways. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1787, 635–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Aoyama H; Muramoto K; Shinzawa-Itoh K; Hirata K; Yamashita E; Tsukihara T; Ogura T; Yoshikawa S A Peroxide Bridge between Fe and Cu Ions in the O2 Reduction Site of Fully Oxidized Cytochrome c Oxidase Could Suppress the Proton Pump. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2009, 106, 2165–2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Liu B; Chen Y; Doukov T; Soltis SM; Stout CD; Fee JA Combined Microspectrophotometric and Crystallographic Examination of Chemically Reduced and X-Ray Radiation-Reduced forms of Cytochrome ba3 Oxidase from Thermus thermophilus: Structure of the Reduced form of the Enzymes. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 820–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Tiefenbrunn T; Liu W; Chen Y; Katritch V; Stout CD; Fee JA; Cherezov V High Resolution Structure of the ba3 Cytochrome c Oxidase from Thermus thermophilus in a Lipidic Environment. Plos One 2011, 6, e22348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Farver O; Chen Y; Fee JA; Pecht I Electron Transfer among the CuA, Heme-b and a3 Centers of Thermus thermophilus Cytochrome ba3. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 3417–3421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Fee JA; Case DA; Noodleman L Toward a Chemical Mechanism of Proton Pumping by the B-Type Cytochrome c Oxidases: Application of Density Functional Theory to Cytochrome ba3 of Thermus thermophilus. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 15002–15021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Siletsky SA; Belevich I; Jasaitis A; Konstantinov AA; Wikström M; Soulimane T; Verkhovsky MI Time-resolved single-turnover of ba3 oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1767, 1383–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Verkhovsky MI; Jasaitis A; Verkhovskaya ML; Morgan JE; Wikstrom M Proton translocation by cytochrome c oxidase. Nature 1999, 400, 480–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Han S; Ching YC; Rousseau DL Primary Intermediate in the Reaction of Oxygen with Fully Reduced Cytochrome c Oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1990, 87, 2491–2495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Han SH; Ching YC; Rousseau DL Primary Intermediate in the Reaction of Mixed-Valence Cytochrome c Oxidase with Oxygen. Biochemistry 1990, 29, 1380–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Ogura T; Takahashi S; Shinzawa-Itoh K; Yoshikawa S; Kitagawa T Observation of the FeII-O2 Stretching Raman Band for Cytochrome Oxidase Compound A at Ambient Temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1990, 112, 5630–5631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Ogura T; Takahashi S; Hirota S; Shinzawa-Itoh K; Yoshikawa S; Appelman EH; Kitagawa T Time-Resolved Resonance Raman Elucidation of the Pathway for Dioxygen Reduction by Cytochrome c Oxidase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1993, 115, 8527–8536. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Varotsis C; Woodruff WH; Babcock GT Time-Resolved Raman Detection of ν(Fe-O) in an Early Intermediate in the Reduction of O2 by Cytochrome-Oxidase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1989, 111, 6439–6440. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Varotsis C; Woodruff WH; Babcock GT Direct Detection of A Dioxygen Adduct of Cytochrome a3 in the Mixed-Valence Cytochrome-Oxidase Dioxygen Reaction. J. Biol. Chem 1990, 265, 11131–11136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Ishigami I; Hikita M; Egawa T; Yeh SR; Rousseau DL Proton Translocation in Cytochrome c Oxidase: Insights from Proton Exchange Kinetics and Vibrational Spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg 2015, 1847, 98–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Van Wart HE; Zimmer J Resonance Raman Evidence for the Activation of Dioxygen in Horseradish Oxyperoxidase. J. Biol. Chem 1985, 260, 8372–8377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Hirota S; Li TS; Phillips GN; Olson JS; Mukai M; Kitagawa T Perturbation of the Fe-O2 Bond by Nearby Residues in Heme Pocket: Observation of νFe-O2 Raman Bands for Oxymyoglobin Mutants. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118, 7845–7846. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Tsubaki M; Nagai K; Kitagawa T Resonance Raman Spectra of Myoglobins Reconstituted with Spirographis and Isospirographis Hemes and Iron 2,4-Diformylprotoporphyrin IX. Effect of Formyl Substitution at the Heme Periphery. Biochemistry 1980, 19, 379–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Phillips SEV Structure and Refinement of Oxymyoglobin at 1.6 Å Resolution. J. Mol. Biol 1980, 142, 531–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Phillips SEV; Schoenborn BP Neutron-Diffraction Reveals Oxygen-Histidine Hydrogen-Bond in Oxymyoglobin. Nature 1981, 292, 81–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Wikström M Energy-Dependent Reversal of the Cytochrome-Oxidase Reaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1981, 78, 4051–4054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Weng LC; Baker GM Reaction of Hydrogen-Peroxide with the Rapid Form of Resting Cytochrome-Oxidase. Biochemistry 1991, 30, 5727–5733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Morgan JE; Verkhovsky MI; Wikstrom M Observation and Assignment of Peroxy and Ferryl Intermediates in the Reduction of Dioxygen to Water by Cytochrome c Oxidase. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 12235–12240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Proshlyakov DA; Pressler MA; Babcock GT Dioxygen Activation and Bond Cleavage by Mixed-Valence Cytochrome c Oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1998, 95, 8020–8025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Fabian M; Wong WW; Gennis RB; Palmer G Mass Spectrometric Determination of Dioxygen Bond Splitting in the “Peroxy” Intermediate of Cytochrome c Oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1999, 96, 13114–13117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Hansson Ӧ; Karlsson B; Aasa R; Vanngard T; Malmström BG The Structure of the Paramagnetic Oxygen Intermediate in the Cytochrome c Oxidase Reaction. EMBO J. 1982, 1, 1295–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Blair DF; Witt SN; Chan SI Mechanism of Cytochrome c Oxidase Catalyzed Dioxygen Reduction at Low-Temperatures - Evidence for 2 Intermediates at the 3-Electron Level and Entropic Promotion of the Bond-Breaking Step. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1985, 107, 7389–7399. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Morgan JE; Verkhovsky MI; Palmer G; Wikstrom M Role of the PR Intermediate in the Reaction of Cytochrome c Oxidase with O2. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 6882–6892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Babcock GT How Oxygen is Activated and Reduced in Respiration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1999, 96, 12971–12973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Proshlyakov DA; Pressler MA; DeMaso C; Leykam JF; DeWitt DL; Babcock GT Oxygen Activation and Reduction in Respiration: Involvement of Redox-Active Tyrosine 244. Science 2000, 290, 1588–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Proshlyakov DA; Ogura T; Shinzawa-Itoh K; Yoshikawa S; Appelman EH; Kitagawa T Selective Resonance Raman Observation of the 607 nm form Generated in the Reaction of Oxidized Cytochrome c Oxidase with Hydrogen-Peroxide. J. Biol. Chem 1994, 269, 29385–29388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Ogura T; Kitagawa T Resonance Raman Characterization of the P Intermediate in the Reaction of Bovine Cytochrome c Oxidase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2004, 1655, 290–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Pinakoulaki E; Daskalakis V; Ohta T; Richter OMH; Budiman K; Kitagawa T; Ludwig B; Varotsis C The Protein Effect in the Structure of Two Ferryl-Oxo Intermediates at the Same Oxidation Level in the Heme Copper Binuclear Center of Cytochrome c Oxidase. J. Biol. Chem 2013, 288, 20261–20266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Gorbikova EA; Belevich I; Wikstrom M; Verkhovsky MI The Proton Donor for O-O Bond Scission by Cytochrome c Oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2008, 105, 10733–10737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Noodleman L Valence Bond Description of Anti-Ferromagnetic Coupling in Transition-Metal Dimers. J. Chem. Phys 1981, 74, 5737–5743. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Noodleman L; Case DA Density-Functional Theory of Spin Polarization and Spin Coupling in Iron-Sulfur Clusters. Adv. Inorg. Chem 1992, 38, 423–470. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Noodleman L; Lovell T; Han W-G; Liu T; Torres RA; Himo F, Density Functional Theory In Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry II, From Biology to Nanotechnology, Lever ABEd. Elsevier Ltd: 2003; Vol. 2, pp 491–510. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Perdew JP; Chevary JA; Vosko SH; Jackson KA; Pederson MR; Singh DJ; Fiolhais C Atoms, Molecules, Solids, and Surfaces - Applications of the Generalized Gradient Approximation for Exchange and Correlation. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 46, 6671–6687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Handy NC; Cohen AJ Left-Right Correlation Energy. Mol. Phys 2001, 99, 403–412. [Google Scholar]

- (52).Lee CT; Yang WT; Parr RG Development of the Colle-Salvetti Correlation-Energy Formula into a Functional of the Electron-Density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Grimme S; Antony J; Ehrlich S; Krieg H A Consistent and Accurate Ab initio Parametrization of Density Functional Dispersion Correction (DFT-D) for the 94 Elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys 2010, 132, 154104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Han Du W-G; Götz AW; Yang LH; Walker RC; Noodleman L A Broken-Symmetry Density Functional Study of Structures, Energies, and Protonation States Along the Catalytic O-O Bond Cleavage Pathway in ba3 Cytochrome c Oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2016, 18, 21162–21171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Han SW; Ching YC; Rousseau DL Ferryl and Hydroxy Intermediates in the Reaction of Oxygen with Reduced Cytochrome c Oxidase. Nature 1990, 348, 89–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Han S; Takahashi S; Rousseau DL Time Dependence of the Catalytic Intermediates in Cytochrome c Oxidase. J. Biol. Chem 2000, 275, 1910–1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Kitagawa T Structures of Reaction Intermediates of Bovine Cytochrome c Oxidase Probed by Time-Resolved Vibrational Spectroscopy. J. Inorg. Biochem 2000, 82, 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Varotsis C; Babcock GT Appearance of the υ(FeIV=O) Vibration from A Ferryl-Oxo Intermediate in the Cytochrome-Oxidase Dioxygen Reaction. Biochemistry 1990, 29, 7357–7362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Belevich I; Verkhovsky MI Molecular Mechanism of Proton Translocation by Cytochrome c Oxidase. Antioxid Redox Sign 2008, 10, 1–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Sharma V; Karlin KD; Wikstrom M Computational Study of the Activated OH State in the Catalytic Mechanism of Cytochrome c Oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2013, 110, 16844–16849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Han Du W-G; Götz AW; Noodleman L A Water Dimer Shift Activates a Proton Pumping Pathway in the PR → F Transition of ba3 Cytochrome c Oxidase. Inorg. Chem 2018, 57, 1048–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Ogura T; Hirota S; Proshlyakov DA; ShinzawaItoh K; Yoshikawa S; Kitagawa T Time-Resolved Resonance Raman Evidence for Tight Coupling between Electron Transfer and Proton Pumping of Cytochrome c Oxidase Upon the Change from the FeV Oxidation Level to the FeIV Oxidation Level. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118, 5443–5449. [Google Scholar]

- (63).Proshlyakov DA; Ogura T; ShinzawaItoh K; Yoshikawa S; Kitagawa T Microcirculating System for Simultaneous Determination of Raman and Absorption Spectra of Enzymatic Reaction Intermediates and Its Application to the Reaction of Cytochrome c Oxidase with Hydrogen Peroxide. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Han Du W-G; Noodleman L Broken Symmetry DFT Calculations/Analysis for Oxidized and Reduced Dinuclear Center in Cytochrome c Oxidase: Relating Structures, Protonation States, Energies, and Mössbauer Properties in ba3 Thermus thermophilus. Inorg. Chem 2015, 54, 7272–7290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).ADF Amsterdam Density Functional Software, SCM, Theoretical Chemistry, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands: http://www.scm.com. [Google Scholar]

- (66).te Velde G; Bickelhaupt FM; Baerends EJ; Guerra CF; Van Gisbergen SJA; Snijders JG; Ziegler T Chemistry with ADF. J. Comput. Chem 2001, 22, 931–967. [Google Scholar]

- (67).Guerra CF; Visser O; Snijders JG; te Velde G; Baerends EJ, Parallelisation of the Amsterdam Density Functional Program In Methods and techniques for computational chemistry, Clementi E; Corongiu C, Eds. STEF: Cagliari, 1995; pp 303–395. [Google Scholar]

- (68).Grimme S; Ehrlich S; Goerigk L Effect of the Damping Function in Dispersion Corrected Density Functional Theory. J. Comput. Chem 2011, 32, 1456–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Klamt A; Schüürmann G COSMO - A New Approach to Dielectric Screening in Solvents with Explicit Expressions for the Screening Energy and Its Gradient. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2 1993, 799–805. [Google Scholar]

- (70).Klamt A Conductor-Like Screening Model for Real Solvents - A New Approach to the Quantitative Calculation of Solvation Phenomena. J. Phys. Chem 1995, 99, 2224–2235. [Google Scholar]

- (71).Klamt A; Jonas V Treatment of the Outlying Charge in Continuum Solvation Models. J. Chem. Phys 1996, 105, 9972–9981. [Google Scholar]

- (72).Pye CC; Ziegler T An Implementation of the Conductor-Like Screening Model of Solvation within the Amsterdam Density Functional Package. Theor. Chem. Acc 1999, 101, 396–408. [Google Scholar]

- (73).Ghysels A; Van Neck D; Van Speybroeck V; Verstraelen T; Waroquier M Vibrational Modes in Partially Optimized Molecular Systems. J. Chem. Phys 2007, 126, 224102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Ghysels A; Van Neck D; Waroquier M Cartesian Formulation of the Mobile Block Hessian Approach to Vibrational Analysis in Partially Optimized Systems. J. Chem. Phys 2007, 127, 164108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Shikama K Nature of the FeO2 Bonding in Myoglobin - An Overview from Physical to Clinical Biochemistry. Experientia 1985, 41, 701–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Chen H; Ikeda-Saito M; Shaik S Nature of the Fe-O2 Bonding in Oxy-Myoglobin: Effect of the Protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 14778–14790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Jensen KP; Ryde U How O2 Binds to Heme - Reasons for Rapid Binding and Spin Inversion. J. Biol. Chem 2004, 279, 14561–14569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Bren KL; Eisenberg R; Gray HB Discovery of the Magnetic Behavior of Hemoglobin: A Beginning of Bioinorganic Chemistry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2015, 112, 13123–13127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Kepp KP; Dasmeh P Effect of Distal Interactions on O2 Binding to Heme. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 3755–3770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Hopmann KH; Noodleman L; Ghosh A Spin Coupling in Roussin’s Red and Black Salts. Chem. Eur. J 2010, 16, 10397–10408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Radoń M; Pierloot K Binding of CO, NO, and O2 to Heme by Density Functional and Multireference Ab initio Calculations. J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112, 11824–11832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Soda T; Kitagawa Y; Onishi T; Takano Y; Shigeta Y; Nagao H; Yoshioka Y; Yamaguchi K Ab initio Computations of Effective Exchange Integrals for H-H, H-He-H and Mn2O2 Complex: Comparison of Broken-Symmetry Approaches. Chem. Phys. Lett 2000, 319, 223–230. [Google Scholar]

- (83).Collman JP; Brauman JI; Halbert TR; Suslick KS Nature of O2 and CO Binding to Metalloporphyrins and Heme Proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1976, 73, 3333–3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Collman JP; Berg KE; Sunderland CJ; Aukauloo A; Vance MA; Solomon EI Distal Metal Effects in Cobalt Porphyrins Related to CcO. Inorg. Chem 2002, 41, 6583–6596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).Collman JP; Sunderland CJ; Berg KE; Vance MA; Solomon EI Spectroscopic Evidence for a Heme-Superoxide/Cu(I) Intermediate in a Functional Model of Cytochrome c Oxidase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 6648–6649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Adam SM; Garcia-Bosch I; Schaefer AW; Sharma SK; Siegler MA; Solomon EI; Karlin KD Critical Aspects of Heme-Peroxo-Cu Complex Structure and Nature of Proton Source Dictate Metal-Operoxo Breakage versus Reductive O-O Cleavage Chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 472–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (87).Mayer I Charge, Bond Order and Valence in the Ab initio SCF Theory. Chem. Phys. Lett 1983, 97, 270–274. [Google Scholar]

- (88).Cramer CJ; Tolman WB; Theopold KH; Rheingold AL Variable Character of O-O and M-O Bonding in Side-On (η2) 1 : 1 Metal Complexes of O2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2003, 100, 3635–3640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (89).Singha A; Das PK; Dey A Resonance Raman Spectroscopy and Density Functional Theory Calculations on Ferrous Porphyrin Dioxygen Adducts with Different Axial Ligands: Correlation of Ground State Wave Function and Geometric Parameters with Experimental Vibrational Frequencies. Inorg. Chem 2019, 58, 10704–10715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (90).Badger RM The Relation between the Internuclear Distances and Force Constants of Molecules and Its Application to Polyatomic Molecules. J. Chem. Phys 1935, 3, 710–714. [Google Scholar]

- (91).Sengupta K; Chatterjee S; Samanta S; Dey A Direct Observation of Intermediates Formed during Steady-State Electrocatalytic O2 Reduction by Iron Porphyrins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2013, 110, 8431–8436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (92).Hashimoto S; Mizutani Y; Tatsuno Y; Kitagawa T Resonance Raman Characterization of Ferric and Ferryl Porphyrin π-Cation Radicals and the FeIV=O Stretching Frequency. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1991, 113, 6542–6549. [Google Scholar]

- (93).Burke JM; Kincaid JR; Peters S; Gagne RR; Collman JP; Spiro TG Structure-Sensitive Resonance Raman Bands of Tetraphenyl and Picket Fence Porphyrin-Iron Complexes, Including an Oxyhemoglobin Analog. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1978, 100, 6083–6088. [Google Scholar]

- (94).Abe M; Kitagawa T; Kyogoku Y Vibrational Assignments of Resonance Raman Lines of Ni(Octaethylporpphyrin) on Basis of a Normal Coordinate Treatment. Chem. Lett 1976, 249–252. [Google Scholar]

- (95).Maxwell JC; Volpe JA; Barlow CH; Caughey WS Infrared Evidence for Mode of Binding of Oxygen to Iron of Myoglobin from Heart Muscle. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 1974, 58, 166–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.