Abstract

Fetal sheep with placental insufficiency-induced intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) have lower fractional rates of glucose oxidation and greater gluconeogenesis, indicating lactate shuttling between skeletal muscle and liver. Suppression of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) activity was proposed because of greater pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK) 4 and PDK1 mRNA concentrations in IUGR muscle. Although PDK1 and PDK4 inhibit PDH activity to reduce pyruvate metabolism, PDH protein concentrations and activity have not been examined in skeletal muscle from IUGR fetuses. Therefore, we evaluated the protein concentrations and activity of PDH and the kinases and phosphatases that regulate PDH phosphorylation status in the semitendinosus muscle from placenta insufficiency-induced IUGR sheep fetuses and control fetuses. Immunoblots were performed for PDH, phosphorylated PDH (E1α), PDK1, PDK4, and pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase 1 and 2 (PDP1 and PDP2, respectively). Additionally, the PDH, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and citrate synthase (CS) enzymatic activities were measured. Phosphorylated PDH concentrations were 28% lower (P < 0.01) and PDH activity was 67% greater (P < 0.01) in IUGR fetal muscle compared with control. PDK1, PDK4, PDP1, PDP2, and PDH concentrations were not different between groups. CS and LDH activities were also unaffected. Contrary to the previous speculation, PDH activity was greater in skeletal muscle from IUGR fetuses, which parallels lower phosphorylated PDH. Therefore, greater expression of PDK1 and PDK4 mRNA did not translate to greater PDK1 or PDK4 protein concentrations or inhibition of PDH as proposed. Instead, these findings show greater PDH activity in IUGR fetal muscle, which indicates that alternative regulatory mechanisms are responsible for lower pyruvate catabolism.

Keywords: glucose metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation, placental insufficiency

INTRODUCTION

Placental insufficiency-induced intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) causes deficits in oxidative glucose metabolism and a reduction in the lean mass (14, 23). The deterioration of placental function leading to fetal growth restriction is a leading cause of perinatal death, and those surviving the perinatal period are at greater risk of developing metabolic syndromes (2, 14, 33, 47). Our ovine model of hyperthermia-induced placental insufficiency successfully recapitulates several aspects of the human IUGR phenotype (25). The IUGR fetus has reductions in skeletal muscle mass and other peripheral tissues relative to neural tissues as a result of lower plasma glucose and insulin concentrations and lower blood oxygen content (6, 35, 36, 50, 63, 64).

Glucose and lactate are the primary fuels in the fetus, and their oxidation accounts for ~50% of the fetal oxygen consumption in normally grown fetuses (17). Although IUGR fetuses are hypoxemic compared with control fetuses, IUGR fetuses have normal or near-normal rates of weight-specific oxygen consumption (25, 45, 46). Though IUGR fetal oxygen uptake rates are normal or near normal, weight-specific rates of fetal glucose uptake are depressed in IUGR fetuses with placental insufficiency, resulting in measurable rates of endogenous glucose production to maintain normal rates of glucose utilization (27, 48, 55, 56). Upregulation of glucose transporters in the brain and heart indicate mechanisms that are enhanced to improve glucose extraction (3, 4, 27). However, alterations in glucose transporters are not evident in all tissues, which indicates that redistribution of glucose may also depend on changes in glucose metabolism (32, 54, 65). IUGR fetuses oxidize a smaller fraction of glucose and have lower glucose oxidation rates, even though glucose utilization rates are normal compared with control fetuses (7, 27, 60). These findings have led to the hypothesis that IUGR fetuses have a higher expression of enzymes that hinder pyruvate oxidative metabolism in skeletal muscle to promote lactate transfer to the liver to support glucose production (7, 27, 60).

The findings to date indicate a central role for inhibition of pyruvate oxidation after glycolysis in skeletal muscle, which is regulated by the phosphorylation status of the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex. The PDH complex converts pyruvate into acetyl-CoA, which is an obligatory process for pyruvate catabolism in the tricarboxylic acid cycle. PDH complex activity is regulated by phosphorylation, and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinases (PDKs 1–4) and pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatases (PDPs 1 and 2) modulate pyruvate catabolism in response to nutrient and endocrine stimuli (39). Phosphorylation of the PDH complex at any of the three serine residues [Ser293 (site 1), Ser300 (site 2), or Ser232 (site3)]of the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex E1α subunit (PDHE1α) subunit lowers the activity of the PDH complex, and dephosphorylation of these sites by PDP1 or PDP2 rescues function (39). PDKs 1–4 are capable of phosphorylating site 1 (Ser293) of the PDH complex, and this site serves as a primary regulatory site of the PDH complex in skeletal muscle (44, 52, 66).

Because of the importance of PDH complex activity for glucose homeostasis, it is not surprising that previous IUGR studies show greater PDK4 mRNA expression in fetal skeletal muscle as either a metabolic consequence of or fetal adaptation to low glucose and insulin concentrations (7, 60). Although not previously studied in IUGR fetal skeletal muscle, PDK1 may also play a role in pyruvate metabolism. Therefore, our objective was to measure protein and mRNA concentrations of PDH, PDP1, PDP2, PDK1, and PDK4 to determine the regulation of PDH complex activity in skeletal muscle of IUGR fetuses. Based on normal glucose utilization and higher glucose production rates in IUGR fetuses, we hypothesize that IUGR fetal skeletal muscle will have greater PDK1 and PDK4 and lower PDP1 and PDP2 protein and mRNA concentrations to lower PDH complex activity and promote lactate production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fetal sheep model of IUGR.

Studies on pregnant Columbia-Rambouillet ewes were approved by the University of Arizona Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and performed at the Agricultural Research Complex, which is accredited by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. Ewes (n = 16) carrying singleton pregnancies were determined with ultrasonography before randomly assigning pregnant ewes to an experimental group, either control (n = 8) or IUGR (n = 8). IUGR fetuses were created by exposing pregnant ewes to elevated ambient temperatures (40°C for 12 h; 35°C for 12 h; dew point maintained at 22°C) from 40 ± 1 to 91 ± 1 days gestational age as described previously (29). Control fetuses were from ewes maintained at 22 ± 1°C that were fed alfalfa pellets to the average ad libitum feed intake of ewes in the IUGR group. Water and salt were available to ewes ad libitum. After the hyperthermic exposure, all ewes were maintained in a thermoneutral environment alongside ewes in the control group.

Surgical preparation and fetal physiological studies.

At day 123 ± 1, each fetus underwent a surgical procedure to place indwelling polyvinyl arterial and venous catheters for blood sampling and infusion, as described previously (27). Animals were allowed to recover for at least 5 days before an in vivo physiological experiment to determine rates of fetal glucose, oxygen, and lactate umbilical uptakes. Fetal catheters for blood sampling were placed in the abdominal aorta via hindlimb pedal arteries and the umbilical vein. Infusion catheters were placed in the femoral veins via the saphenous veins. Maternal catheters were placed in the femoral artery and vein for arterial sampling and venous infusions. All catheters were tunneled subcutaneously to the ewe’s flank, exteriorized through a skin incision, and kept in a plastic mesh pouch sutured to the ewe’s skin. Catheters were flushed daily with heparinized saline solution (100 U/mL heparin in 0.9% NaCl solution, Vedco, St. Joseph, MO).

Rates of umbilical uptakes for O2, glucose, and lactate were measured at 130 ± 1 days gestational age. Umbilical blood flows were measured by steady-state tritiated water diffusion methods (New England Nucleotides; PerkinElmer, Boston, MA). After a priming bolus of 50 μCi 3H2O, the intravenous 3H2O infusion (0.83 μCi/min) began 60 min before sampling commenced. Sets of blood samples (n = 6 sets) were collected at 10-min intervals to determine blood flow, blood gases, blood oximetry, plasma metabolites, and hormone concentration. At the start of tracer infusion, an infusion of maternal blood (8–10 mL/h) was given to the fetus to avoid fetal anemia from sampling.

Biochemical analysis.

Arterial blood gases and oximetry were measured with an ABL825 (Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark), and values were temperature corrected to 39.1°C. Plasma glucose and lactate concentrations were measured with the YSI model 2700 SELECT Biochemistry Analyzer (YSI, Yellow Springs, OH). Additionally, plasma concentrations of insulin (ovine insulin ELISA; ALPCO Diagnostics, Salem, NH; intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation <6%; sensitivity 0.14 ng/mL) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline ELISA; Labor Diagnostika Nord, Nordhorn, Germany; intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation < 14%; sensitivity 35 pg/mL) were quantified.

Tissue collection.

At day 134 ± 1, the ewe and the fetus were euthanized with an intravenous administration of pentobarbital sodium (86 mg/kg) and phenytoin sodium (11 mg/kg; Euthasol; Virbac Animal Health). Organs and skeletal muscles (biceps femoris and semitendinosus) from control and IUGR fetuses were dissected and weighed. These tissues were then snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for in vitro experiments.

Quantitative PCR.

PDK1, PDK4, PDH, PDP1, and PDP2 mRNA concentrations were measured with quantitative PCR (qPCR) on IUGR (n = 8) and control (n = 8) fetuses on semitendinosus muscle. Total cellular RNA was extracted from semitendinosus muscle as described previously (21). RNA concentration and purity were determined from absorbance measurements with a NanoDrop 1000 Spectrophotometer (NonoDrop, Wilmington, DE), and RNA quality (RNA integrity number >9.5) was measured with an Experion Automated Electrophoresis Station (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Messenger RNA (1 μg total cellular RNA per reaction) was reverse transcribed in triplicate into cDNA with Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). cDNA was amplified using a QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, the Netherlands) and a CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). Optimal annealing temperatures for primer pairs were determined. Primer specificity was confirmed with nucleotide sequencing of the cloned PCR products (pCR 2.1-TOPO vector; cat. no. K4510oo20; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Primer efficiencies and sensitivities were measured with serial cDNA dilutions. All primers had efficiency ≥85%, and threshold cycles (CTs) were linear over 6 orders of magnitude. After an initial 15-min denaturation incubation at 96°C, all reactions went through 40 cycles at 96°C (30 s), annealing temperature (30 s), and 72°C (10 s) extension and read. Primers synthesized for qPCR are as follows: PDK1 [Forward (F): 5′-TGGAGCATCACGCTGACAAA-3′, Reverse (R): 5′-CTCAGAGGAACACCACCTCC-3′], PDK4 (F: 5′-CCCAGAGGACCAAAAGGCAT-3′, R: 5′-GGGTCAGCTGTACAGGCATC-3′), PDHE1α (F: 5′-GGTGGCATCCCGTCATTTTG-3′, R: 5′-CGAACGGTCTGCATCATCCT-3′), PDP1 (F: 5′-GTTGTGGATGTTGTCGGCTC-3′, R: 5′-TGCAGTGCCATAGATTCTGCT-3′), PDP2 (F: 5′-CTGCTGTTTGGCATCTTCGAC-3′, R: 5′-CTTTCCATGGCCTCCTCCATT-3′), tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein-ζ (YWHAZ) (F: 5′-AGACGGAAGGTGCTGAGAAA-3′, R: 5′-CGTTGGGGATCAAGAACTTT-3′), TATA-binding protein (TBP) (F: 5′-AGAATAAGAGAGCCCCGCAC-3′, R: 5′-TTCACATCACAGCTCCCCAC-3′), ribosomal protein S15 (RPS15) (F: 5′- ATCATTCTGCCCGAGATGGTG-3′, R: 5′-TGCTTTACGGGCTTGTAGGTG-3′), and GAPDH (F: 5′-CTGGCCAAGGTCATCCAT-3′, R: 5′-ACA- GTCTTCTGGGTGGCAGT-3′). Expression values for the genes of interest were normalized to the geometric mean of reference genes: TBP, YWHAZ, RPS15, and GAPDH. Results were normalized to the geometric mean of the reference genes using the comparative change of CT method (CT gene of interest − CT reference gene) (28). The change of CT values was calculated for group comparisons. Gene analysis was performed adhering to Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments guidelines (8).

Western blot analysis.

Protein lysates were prepared from semitendinosus muscle in ice-cold CelLytic MT buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) containing additional protease and phosphatase inhibitors: 0.5 mM phenylmethane sulfonyl fluoride (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 2 µg/mL aprotinin (Sigma-Aldrich), 2.5 µg/mL leupeptin (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 µM dl-dithiothreitol (Sigma-Aldrich), and 5 mM sodium vanadate (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein concentrations were measured with a Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein (50 μg) from each animal was separated on a 10% polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad). The membranes were blocked in a 5% (wt/vol) nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline, 0.1% Tween 20 solution for 30 min at room temperature and then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies in 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline, 0.1% Tween 20. The primary antibodies used are as follows: anti-PDP1 (1:3,000; Abcam, cat. no. ab198261, RRID: AB_2756338), anti-PDP2 (1:3,000; Abcam, cat. no. ab99170, RRID: AB_10670444), anti-PDHE1α (1:3,000; Abcam, cat. no. ab110334, RRID: AB_10866116), anti-phospho-PDHE1α (Ser293, 1:3,000; Abcam, cat. no. ab177461, RRID: AB_2756339), anti-PDK1 (1:3,000; Abcam, cat. no. ab90444, RRID: AB_2161150), and anti-PDK4 (1:3,000; Abcam, cat. no. ab110336, RRID: AB_10863042). Goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:15,000; Bio-Rad RRID: AB_11125142) were detected with SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific) and exposed to Blue Lite Autorad Film (VWR, Radnor, PA). Protein abundances were quantified using photographed images and densitometric analyses (Scion Image software; Scion, Frederick, MD). Protein abundances of PDP1, PDP2, PDHE1α, phospho-PDHE1α, PDK1, and PDK4 were normalized to β-tubulin (1:3,000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. RB-9249-P, RRID: AB_722291). Phosphorylated PDHE1α was normalized to total PDHE1α. All samples were evaluated in triplicate, and data are presented relative to control values.

Enzymatic assays.

PDH activity was measured in biceps femoris and semitendinosus skeletal muscle in triplicate with the PDH Activity Assay Kit (MAK183, Sigma-Aldrich). Skeletal muscle (100 mg) was homogenized in 1 mL of ice-cold PDH assay buffer, and 10 µL of lysate was measured in triplicate reactions. Reactions were carried out at 37°C, and A450 was recorded every 5 min for 30 min. PDH activity rates are reported in nmol·min−1·mL−1, as per assay protocol.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity was measured in biceps femoris and semitendinosus skeletal muscle in triplicate with the LDH Activity Assay Kit (cat. no. ab102526, Abcam). Skeletal muscle (100 mg) was homogenized according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reactions were carried out at 37°C, and A450 was measured every 2 min for 30 min. LDH activity rates are reported in nmol·min−1·mL−1, as per assay protocol.

Citrate synthase (CS) activity was measured in biceps femoris and semitendinosus skeletal muscle in triplicate with the Citrate Synthase Assay Kit (cat. no. CS0720, Sigma-Aldrich), as described previously (10). Rates for CS are reported as nmol·min−1·mg protein−1.

Calculations and statistical analysis.

The rate of umbilical blood flow (f; mL·min−1·kg−1) was calculated using the transplacental steady-state diffusion technique, with tritiated water as the blood flow indicator, and normalized to fetal weight during the study (26). Net umbilical uptake rates (Rf,p; μmol·min−1·kg−1) for oxygen, glucose, and lactate by the fetus from the placenta were calculated as the product of the umbilical blood (or plasma) flow and concentration difference between the umbilical vein (Cv) and umbilical artery (Ca), blood (O2), or plasma (glucose and lactate) concentrations [Rf,p = f(Cv − Ca)] (6, 25).

Significant differences (P < 0.05) between groups (control and IUGR) were determined with a post hoc general linear means ANOVA and post hoc least-significant distance test using general linear means procedures in the JMP software system (version 14.0.0; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Normality and skewness were ensured using a D’Agostino-Pearson normality test. The variance between groups for each condition (e.g., immunoblot and qPCR for each gene/protein) was equal between all groups in all conditions, except for the immunoblot values for PDP1 (Levene’s test), and analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Linear regression analyses for mRNA expression were performed using JMP 14. Data are presented as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Placental insufficiency causes an IUGR phenotype.

In IUGR fetuses, blood oxygen, plasma glucose, plasma norepinephrine, and plasma insulin concentrations were lower than controls, whereas plasma lactate concentrations were not different (Table 1). Umbilical blood flow and rates of net umbilical oxygen uptake were not different between groups (Table 1). Rates of net umbilical glucose and lactate uptakes were significantly lower in IUGR fetuses compared with control fetuses (Table 1).

Table 1.

Fetal metabolic parameters of control and IUGR fetuses

| Measurement | Control (n = 8) | IUGR (n = 8) |

|---|---|---|

| Umbilical blood flow, mL·min−1·kg−1 | 186 ± 23 | 159 ± 9 |

| Arterial blood O2 content, mM | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.1* |

| Umbilical O2 uptake, μmol·min−1·kg−1 | 357 ± 16.7 | 313 ± 22.7 |

| Arterial (glucose), mM | 1.02 ± 0.04 | 0.61 ± 0.06* |

| Umbilical glucose uptake, μmol·min−1·kg−1 | 27.3 ± 2.24 | 22.1 ± 0.97* |

| Arterial (lactate), mM | 2.34 ± 0.66 | 1.75 ± 0.21 |

| Umbilical lactate uptake, μmol·min−1·kg−1 | 16.9 ± 3.23 | 8.35 ± 1.97* |

| Δ maternal-fetal O2 content, mM | 2.32 ± 0.13 | 4.58 ± 0.20* |

| Arterial norepinephrine, pg/mL | 712 ± 183 | 4,310 ± 920* |

| Arterial insulin, ng/mL | 0.36 ± 0.06 | 0.16 ± 0.05* |

Values are expressed as means ± SE. IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction.

P < 0.01.

Fetal and placental mass were lower in IUGR fetuses than control fetuses (Table 2). Semitendinosus muscles weighed 51% less in IUGR fetuses than control fetuses but were similar relative to fetal weight (Table 2). Similarly, although brain weights in IUGR fetuses were 16% lower, brain weight relative to fetal weight was 53% higher in IUGR fetuses compared with controls (Table 2).

Table 2.

Biometric measurements of control and IUGR fetuses

| Measurement | Control (n = 8) | IUGR (n = 8) |

|---|---|---|

| Male fetuses, % | 50 | 37 |

| Age at necropsy, days | 134 ± 1 | 133 ± 1 |

| Fetal weight, kg | 3.37 ± 0.16 | 1.57 ± 0.25* |

| Placental weight, g | 363 ± 35.1 | 117 ± 14.3* |

| Brain weight, g | 48.9 ± 1.24 | 41.4 ± 1.76* |

| Brain weight, g/fetal weight, kg | 15.9 ± 0.86 | 27.5 ± 1.93* |

| Total semitendinosus weight, g | 12.5 ± 1.16 | 6.17 ± 0.69* |

| Semitendinosus weight, g/fetal weight, kg | 4.01 ± 0.20 | 3.71 ± 0.12 |

| Total biceps femoris weight, g | 32.1 ± 1.74 | 16.2 ± 2.28* |

| Biceps femoris weight, g/fetal weight, kg | 9.74 ± 0.54 | 8.93 ± 0.37 |

Values are expressed as means ± SE. IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction.

P < 0.01.

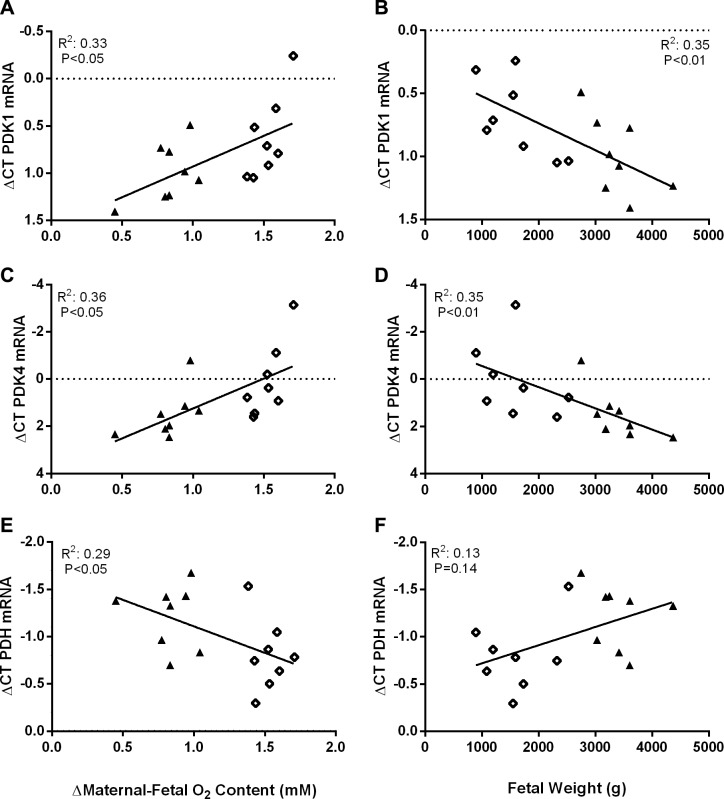

Greater PDK1 and PDK4 mRNA expression in IUGR skeletal muscle.

PDK1 and PDK4 mRNA concentrations were 1.3- and 2.8-fold greater, respectively, in IUGR semitendinosus muscle compared with control muscle (Fig. 1). PDH, PDP1, and PDP2 mRNA concentrations were not different between groups (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fold change for mRNA expression relative to control fetuses. Fold changes relative to control mRNA concentrations are presented for PDK1, PDK4, PDH, PDP1, and PDP2. Values are expressed as means ± SE. *Differences (P < 0.05) between groups. IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase; PDK, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase; PDP, pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase.

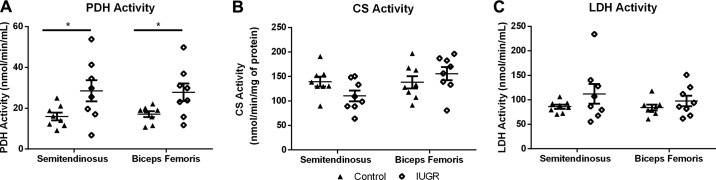

PDK1 and PDK4 mRNA concentrations were positively associated with the transplacental (maternal-fetal) arterial oxygen concentration difference and negatively associated with fetal mass (Fig. 2, A–D). PDH mRNA concentrations were negatively associated with the transplacental arterial oxygen concentration difference and positively associated with fetal mass (Fig. 2, E and F). PDK1 mRNA concentrations were negatively associated with fetal oxygen content (R2 = 0.3010, P < 0.05). PDK4 mRNA was also negatively associated with fetal oxygen content (R2 = 0.3788, P < 0.05). PDH mRNA concentrations were positively associated with fetal oxygen content (R2 = 0.4180, P < 0.05) and fetal glucose concentrations (R2 = 0.2884, P < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Gene expression correlates with parameters of placental insufficiency and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). Correlations are presented for pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK)1, PDK4, and pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) with the maternal-fetal arterial O2 content difference (millimolars; A–C) and with fetal weight (grams; D–F). The maternal-fetal O2 content gradient was used as a marker of placental insufficiency and fetal weight was used as a measure of IUGR for mRNA correlations. mRNA data (y-axis) are presented as the comparative change of threshold cycles (ΔCT) values of the gene of interest relative to the geometric mean of the reference genes for control (closed triangles, n = 8) and IUGR (open diamonds, n = 8). Linear regression was performed with JMP 14 and R2, and P values are indicated.

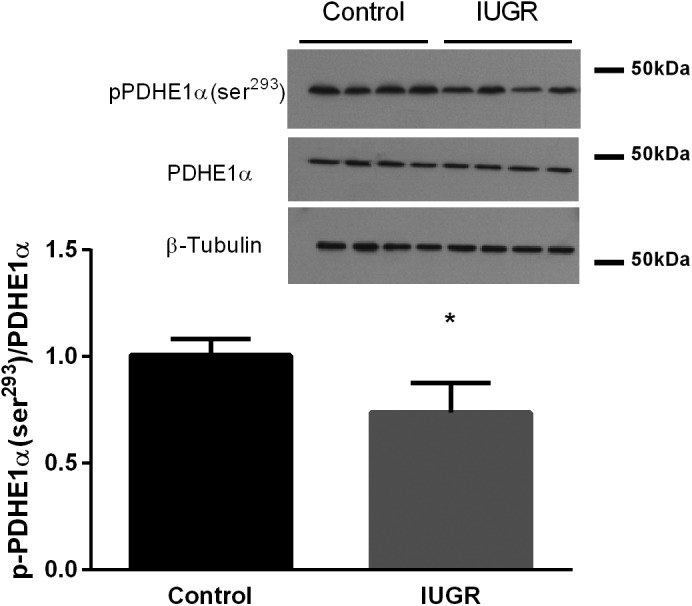

Lower phosphorylation status leads to greater PDH activity in IUGR muscle.

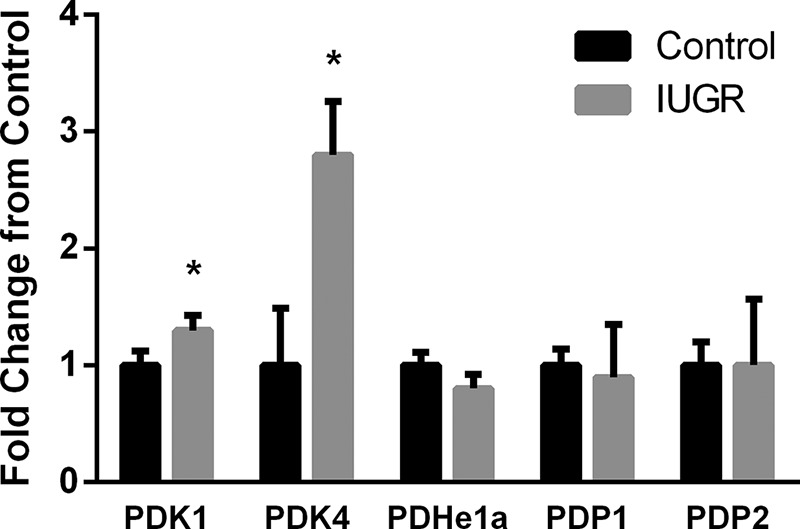

No difference in PDK1, PDK4, PDP1, PDP2, or PDH protein concentrations were detected between groups (Table 3). Phosphorylated PDH (Ser293) concentrations were 28% lower in IUGR semitendinosus muscle compared with control muscle (Fig. 3). PDH complex activity was 67% greater in IUGR muscle compared with control muscle (Fig. 4A). CS and LDH activities were not different between groups (Fig. 3, B and C).

Table 3.

Protein concentrations relative to control fetuses

| Protein | Control (n = 8) | IUGR (n = 8) |

|---|---|---|

| PDK1 | 1.0 ± 0.06 | 0.97 ± 0.04 |

| PDK4 | 1.0 ± 0.09 | 0.85 ± 0.08 |

| PDH | 1.0 ± 0.06 | 0.94 ± 0.03 |

| p-PDHE1α (Ser293):PDH ratio | 1.0 ± 0.08 | 0.74 ± 0.04* |

| PDP1 | 1.0 ± 0.06 | 0.96 ± 0.03 |

| PDP2 | 1.0 ± 0.04 | 1.1 ± 0.05 |

Values are relative to control and expressed as means ± SE. IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase; p-PDHE1α, phospho-PDH complex E1α subunit; PDK, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase; PDP, pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase.

P < 0.05.

Fig. 3.

Lower phosphorylated pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) E1α (p-PDHE1α) (Ser293) concentrations in intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) semitendinosus muscle. p-PDH (Ser293) concentrations are presented relative to total PDH for the semitendinosus muscle from control and IUGR fetuses (n = 8/group). Representative immunoblots are shown for p-PDH (Ser293) and β-tubulin in four control and four IUGR fetal muscle samples. Values are expressed as means ± SE. *Differences (P < 0.05) between groups.

Fig. 4.

Pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and citrate synthase (CS) activity in control and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) skeletal muscles. PDH activity (A), CS activity (B), and LDH activity (C) were measured in semitendinosus and biceps femoris muscles from control and IUGR fetuses (n = 8/group). Individual fetal muscle activities are presented with the means ± SE for the groups. The asterisks and bar indicate differences between groups within muscles (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Although our data are consistent with previous reports showing greater PDK4 mRNA expression in IUGR skeletal muscle, protein concentrations of PDK4 did not parallel mRNA expression (7, 60). Instead, we demonstrate that the PDH complex has a reduced phosphorylation status and greater enzymatic activity in skeletal muscle from IUGR fetuses. Furthermore, PDK1 mRNA concentrations were elevated in IUGR skeletal muscle, but the increase in PDK1 mRNA is also incongruent with PDK1 protein concentrations. We also show that the depressed phosphorylation status of PDH (E1α Ser293) was not explained by increases in mRNA and protein concentrations of PDH, PDP1, and PDP2 in muscle from IUGR fetuses. These findings indicate that skeletal muscle pyruvate metabolism may be higher because of increased PDH complex activity, a response that likely normalizes metabolism in the hypoglycemic IUGR fetus (48).

Transcription of both PDK1 and PDK4 are regulated, in part, by hypoxia, which explains the higher mRNA expression in IUGR fetuses (9, 12, 13, 24, 49). Under acute hypoxic conditions, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α increases the expression of these kinases, which serves to maintain ATP production under low oxygen tension by promoting gene expression for anaerobic metabolism and reducing mitochondrial oxygen consumption (1, 9, 12, 22, 24, 37, 62). Interestingly, although there is evidence of increased prolyl hydroxylase domain expression in IUGR fetuses, hypoxia-inducible factor-1/2α activity is increased in IUGR fetuses compared with control fetuses (30, 31, 34). This most likely represents a new hypoxic set point in response to chronic hypoxemia in IUGR tissues; consequently, the expression of genes regulated by hypoxia-response element, such as PDK1, is increased in IUGR fetuses (5, 16, 30, 31, 34). PDK1, through altered hypoxemic signaling, may contribute to the reprogramming of glucose metabolism in skeletal muscle from oxidative phosphorylation to anaerobic glycolysis by increasing the activities of hexokinase and phosphofructose kinase 1; the latter is known to be expressed at greater concentrations in muscle from IUGR fetuses (7, 20, 34, 60). In contrast to PDK1, PDK4 transcription is also regulated by insulin (18, 19). High insulin concentrations decreased PDK4 mRNA expression in skeletal muscle and increased glucose catabolism in accordance with availability (12, 20, 24, 41–43, 53, 61). Considering that the IUGR fetus is hypoglycemic, hypoxemic, and hypoinsulinemic, the upregulation of both PDK1 and PDK4 mRNA are plausible metabolic adaptations to a challenging in utero environment.

Greater PDK1 and PDK4 mRNA expression in the semitendinosus muscle of IUGR fetuses did not translate into increased protein concentrations or activities. Interestingly, greater PDH complex activity in IUGR muscle may explain in vivo observations that show the lactate + glucose-oxygen quotient is maintained across the hindlimb of the IUGR fetus, even though the individual quotients indicate higher rates of glucose uptake and lactate output per mole of oxygen consumed by the IUGR hindlimb (48). Reduced phosphorylation of PDH is explained by decreased PDK activity or increased PDP activity in IUGR skeletal muscle rather than their actual protein concentrations. Short-term, transient PDK activity is regulated by allosteric effectors such as high acetyl-CoA-to-CoA and NADH-to-NAD+ concentration ratios and is suppressed by high pyruvate or lactate concentrations generated by glycolysis (38). Furthermore, PDP1/2 is transiently activated by insulin-dependent phosphorylation by protein kinase C, and this is thought to be the major mechanism of activation for these phosphatases in both the liver and skeletal muscle (11). Since we do not observe a difference in protein concentration for PDKs or PDPs between groups, we hypothesize that the activities of these kinases would be decreased in IUGR skeletal muscle.

PDH activity is higher in IUGR skeletal muscle but may not correct the defect in whole body fractional glucose oxidation (7, 27). Although the IUGR fetuses are hypoinsulinemic, they have been shown to have greater insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle (27, 36, 56). Greater insulin sensitivity might explain the disconnection between fractional glucose oxidation rates and PDH complex activity, as insulin would activate PDP1 and PDP2 and inactivate PDK4 (11). Also, since this demonstrates a mechanism by which the IUGR fetus adapts to sustained hypoglycemia, it might also adapt to chronic hypoxemia. Likewise, changes in pyruvate carboxylase (PC) regulation would affect the glucose oxidation fraction. Decreased PC expression or activity, although having normal PDH expression and activity, would cause shunting of pyruvate-to-lactate production. The shunting of pyruvate to lactate would provide a sufficient glycolytic-derived carbon source to maintain plasma glucose concentration via the Cori cycle; however, we found no differences in LDH activity between groups in both semitendinosus and biceps femoris skeletal muscle (15, 59). Although there are no differences in plasma lactate concentrations or LDH activity between groups, this might be representative of a new metabolic set point between skeletal muscle lactate production and hepatic gluconeogenesis in the IUGR fetus (27).

We have previously shown fewer type I oxidative muscle fibers but no differences in type II muscle fibers in semitendinosus and biceps femoris muscle in IUGR fetuses compared with controls (63). Skeletal muscles can undergo fiber-type switching in response to mitochondrial dysfunction, namely type I to type II; this is an effective adaptation in IUGR fetuses, as type II muscle fibers have lower mitochondrial contents compared with type I fibers (57, 58). Therefore, it is expected that skeletal muscles that have fewer type I fibers will have reduced glucose metabolism and decreased PDH expression and/or activity. However, using CS activity measurements as a proxy for mitochondrial number, our findings do not support dramatic changes in mitochondrial content of these representative mixed-fiber-type muscles similar to previous observations (32). Therefore, we propose that the change in PDH activity and phosphorylation status outweigh the potential fiber-type switching in the skeletal muscles of IUGR fetuses, and this may be a direct result of decreased PDK activity rather than expression (40, 51).

The findings in this study demonstrate that IUGR fetal sheep have higher PDH complex activity. Despite greater PDK1 and PDK4 mRNA concentrations in IUGR skeletal muscle, there were no differences in protein concentrations of the kinases and phosphatases that regulate the PDH complex. In fact, phosphorylation of PDH Eα1 was lower and enzymatic activity higher in skeletal muscle from IUGR fetuses. These data indicate that the PDH complex is upregulated to normalize pyruvate metabolism in IUGR fetuses with hypoglycemia.

Perspectives and Significance

The present study confirms upregulated PDK mRNA concentrations in IUGR skeletal muscle, corresponding with findings from previous studies. However, inhibition of PDH activity is unexpected because protein concentrations for these kinases were unaffected. Despite higher in vitro rates of PDH activity in IUGR skeletal muscle observed in our study, previous in vivo studies have shown lower weight-specific glucose oxidation rates in IUGR fetuses. The results of previous studies and our present work are not necessarily incongruous, as the defect in metabolism may be due to incomplete glucose catabolism by PC, defects in oxidative phosphorylation, or decreased mitochondrial function. Defects in or posttranslation modifications of enzymes involved in the metabolic processes within mitochondria can lead to mitochondrial fuel inflexibility, which can manifest into metabolic syndromes that are associated with developmental programming.

GRANTS

This work was supported by NIH Grant R01-DK-084842 (Principal Investigator, S. W. Limesand). A. Pendleton was supported by Grant T32-HL-007249 (Principal Investigator, C. C. Gregorio). L. E. Camacho was supported by National Institute of Food and Agriculture Postdoctoral Fellowship Award no. 2015-03545 and Grant T32-HL-007249 (Principal Investigator, C. C. Gregorio).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.L.P. and S.W.L. conceived and designed research; A.L.P., L.R.H., M.A.D., L.E.C., M.J.A., and S.W.L. performed experiments; A.L.P., L.R.H., M.J.A., and S.W.L. analyzed the data; A.L.P., L.R.H., M.A.D., L.E.C., M.J.A., and S.W.L. interpreted results of experiments; A.L.P. and S.W.L. prepared figures; A.L.P. and S.W.L. drafted the manuscript; A.L.P., L.R.H., M.A.D., L.E.C., M.J.A., and S.W.L. edited and revised manuscript; A.L.P., L.R.H., M.A.D., L.E.C., M.J.A., and S.W.L. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nathan R. Steffens, David Taska, and Mandie M. Dunham for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balaban RS, Nemoto S, Finkel T. Mitochondria, oxidants, and aging. Cell 120: 483–495, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker DJ. In utero programming of chronic disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 95: 115–128, 1998. doi: 10.1042/cs0950115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barry JS, Davidsen ML, Limesand SW, Galan HL, Friedman JE, Regnault TR, Hay WW Jr. Developmental changes in ovine myocardial glucose transporters and insulin signaling following hyperthermia-induced intrauterine fetal growth restriction. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 231: 566–575, 2006. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barry JS, Rozance PJ, Brown LD, Anthony RV, Thornburg KL, Hay WW Jr. Increased fetal myocardial sensitivity to insulin-stimulated glucose metabolism during ovine fetal growth restriction. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 241: 839–847, 2016. doi: 10.1177/1535370216632621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Botting KJ, McMillen IC, Forbes H, Nyengaard JR, Morrison JL. Chronic hypoxemia in late gestation decreases cardiomyocyte number but does not change expression of hypoxia-responsive genes. J Am Heart Assoc 3: e000531, 2014. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown LD. Endocrine regulation of fetal skeletal muscle growth: impact on future metabolic health. J Endocrinol 221: R13–R29, 2014. doi: 10.1530/JOE-13-0567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown LD, Rozance PJ, Bruce JL, Friedman JE, Hay WW Jr, Wesolowski SR. Limited capacity for glucose oxidation in fetal sheep with intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 309: R920–R928, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00197.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, Vandesompele J, Wittwer CT. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem 55: 611–622, 2009. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cairns RA, Papandreou I, Sutphin PD, Denko NC. Metabolic targeting of hypoxia and HIF1 in solid tumors can enhance cytotoxic chemotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 9445–9450, 2007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611662104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camacho LE, Chen X, Hay WW Jr, Limesand SW. Enhanced insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity in young lambs with placental insufficiency-induced intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 313: R101–R109, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00068.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caruso M, Maitan MA, Bifulco G, Miele C, Vigliotta G, Oriente F, Formisano P, Beguinot F. Activation and mitochondrial translocation of protein kinase Cdelta are necessary for insulin stimulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity in muscle and liver cells. J Biol Chem 276: 45088–45097, 2001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105451200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connaughton S, Chowdhury F, Attia RR, Song S, Zhang Y, Elam MB, Cook GA, Park EA. Regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isoform 4 (PDK4) gene expression by glucocorticoids and insulin. Mol Cell Endocrinol 315: 159–167, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dupuy F, Tabariès S, Andrzejewski S, Dong Z, Blagih J, Annis MG, Omeroglu A, Gao D, Leung S, Amir E, Clemons M, Aguilar-Mahecha A, Basik M, Vincent EE, St-Pierre J, Jones RG, Siegel PM. PDK1-dependent metabolic reprogramming dictates metastatic potential in breast cancer. Cell Metab 22: 577–589, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gagnon R. Placental insufficiency and its consequences. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 110, Suppl 1: S99–S107, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0301-2115(03)00179-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.García-Cazorla A, Rabier D, Touati G, Chadefaux-Vekemans B, Marsac C, de Lonlay P, Saudubray JM. Pyruvate carboxylase deficiency: metabolic characteristics and new neurological aspects. Ann Neurol 59: 121–127, 2006. doi: 10.1002/ana.20709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ginouvès A, Ilc K, Macías N, Pouysségur J, Berra E. PHDs overactivation during chronic hypoxia “desensitizes” HIFα and protects cells from necrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 4745–4750, 2008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705680105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hay WW Jr, Myers SA, Sparks JW, Wilkening RB, Meschia G, Battaglia FC. Glucose and lactate oxidation rates in the fetal lamb. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 173: 553–563, 1983. doi: 10.3181/00379727-173-41686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang B, Wu P, Bowker-Kinley MM, Harris RA. Regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase expression by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α ligands, glucocorticoids, and insulin. Diabetes 51: 276–283, 2002. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeong JY, Jeoung NH, Park KG, Lee IK. Transcriptional regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase. Diabetes Metab J 36: 328–335, 2012. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2012.36.5.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeoung NH. Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinases: therapeutic targets for diabetes and cancers. Diabetes Metab J 39: 188–197, 2015. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2015.39.3.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly AC, Bidwell CA, Chen X, Macko AR, Anderson MJ, Limesand SW. Chronic adrenergic signaling causes abnormal RNA expression of proliferative genes in fetal sheep islets. Endocrinology 159: 3565–3578, 2018. doi: 10.1210/en.2018-00540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim JW, Tchernyshyov I, Semenza GL, Dang CV. HIF-1-mediated expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase: a metabolic switch required for cellular adaptation to hypoxia. Cell Metab 3: 177–185, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krishna U, Bhalerao S. Placental insufficiency and fetal growth restriction. J Obstet Gynaecol India 61: 505–511, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s13224-011-0092-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JH, Kim EJ, Kim DK, Lee JM, Park SB, Lee IK, Harris RA, Lee MO, Choi HS. Hypoxia induces PDK4 gene expression through induction of the orphan nuclear receptor ERRγ. PLoS One 7: e46324, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Limesand SW, Camacho LE, Kelly AC, Antolic AT. Impact of thermal stress on placental function and fetal physiology. Anim Reprod 15, Suppl 1: 886–898, 2018. doi: 10.21451/1984-3143-AR2018-0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Limesand SW, Rozance PJ, Brown LD, Hay WW Jr. Effects of chronic hypoglycemia and euglycemic correction on lysine metabolism in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 296: E879–E887, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90832.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Limesand SW, Rozance PJ, Smith D, Hay WW Jr. Increased insulin sensitivity and maintenance of glucose utilization rates in fetal sheep with placental insufficiency and intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E1716–E1725, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00459.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Δ Δ C(T)) Method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macko AR, Yates DT, Chen X, Shelton LA, Kelly AC, Davis MA, Camacho LE, Anderson MJ, Limesand SW. Adrenal demedullation and oxygen supplementation independently increase glucose-stimulated insulin concentrations in fetal sheep with intrauterine growth restriction. Endocrinology 157: 2104–2115, 2016. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGillick EV, Orgeig S, Morrison JL. Structural and molecular regulation of lung maturation by intratracheal vascular endothelial growth factor administration in the normally grown and placentally restricted fetus. J Physiol 594: 1399–1420, 2016. doi: 10.1113/JP271113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGillick EV, Orgeig S, Morrison JL. Regulation of lung maturation by prolyl hydroxylase domain inhibition in the lung of the normally grown and placentally restricted fetus in late gestation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 310: R1226–R1243, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00469.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muhlhausler BS, Duffield JA, Ozanne SE, Pilgrim C, Turner N, Morrison JL, McMillen IC. The transition from fetal growth restriction to accelerated postnatal growth: a potential role for insulin signalling in skeletal muscle. J Physiol 587: 4199–4211, 2009. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.173161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicholas LM, Rattanatray L, MacLaughlin SM, Ozanne SE, Kleemann DO, Walker SK, Morrison JL, Zhang S, Muhlhäusler BS, Martin-Gronert MS, McMillen IC. Differential effects of maternal obesity and weight loss in the periconceptional period on the epigenetic regulation of hepatic insulin-signaling pathways in the offspring. FASEB J 27: 3786–3796, 2013. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-227918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orgeig S, McGillick EV, Botting KJ, Zhang S, McMillen IC, Morrison JL. Increased lung prolyl hydroxylase and decreased glucocorticoid receptor are related to decreased surfactant protein in the growth-restricted sheep fetus. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 309: L84–L97, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00275.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Owens JA, Falconer J, Robinson JS. Glucose metabolism in pregnant sheep when placental growth is restricted. Am J Physiol 257: R350–R357, 1989. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.257.2.R350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Owens JA, Gatford KL, De Blasio MJ, Edwards LJ, McMillen IC, Fowden AL. Restriction of placental growth in sheep impairs insulin secretion but not sensitivity before birth. J Physiol 584: 935–949, 2007. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Papandreou I, Cairns RA, Fontana L, Lim AL, Denko NC. HIF-1 mediates adaptation to hypoxia by actively downregulating mitochondrial oxygen consumption. Cell Metab 3: 187–197, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park S, Jeon JH, Min BK, Ha CM, Thoudam T, Park BY, Lee IK. Role of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex in metabolic remodeling: differential pyruvate dehydrogenase complex functions in metabolism. Diabetes Metab J 42: 270–281, 2018. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2018.0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel MS, Korotchkina LG. Regulation of mammalian pyruvate dehydrogenase complex by phosphorylation: complexity of multiple phosphorylation sites and kinases. Exp Mol Med 33: 191–197, 2001. doi: 10.1038/emm.2001.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peters SJ, Harris RA, Heigenhauser GJ, Spriet LL. Muscle fiber type comparison of PDH kinase activity and isoform expression in fed and fasted rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 280: R661–R668, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.3.R661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pilegaard H, Birk JB, Sacchetti M, Mourtzakis M, Hardie DG, Stewart G, Neufer PD, Saltin B, van Hall G, Wojtaszewski JF. PDH-E1α dephosphorylation and activation in human skeletal muscle during exercise: effect of intralipid infusion. Diabetes 55: 3020–3027, 2006. doi: 10.2337/db06-0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pilegaard H, Neufer PD. Transcriptional regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 in skeletal muscle during and after exercise. Proc Nutr Soc 63: 221–226, 2004. doi: 10.1079/PNS2004345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pilegaard H, Saltin B, Neufer PD. Effect of short-term fasting and refeeding on transcriptional regulation of metabolic genes in human skeletal muscle. Diabetes 52: 657–662, 2003. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.3.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rardin MJ, Wiley SE, Naviaux RK, Murphy AN, Dixon JE. Monitoring phosphorylation of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. Anal Biochem 389: 157–164, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Regnault TR, de Vrijer B, Galan HL, Davidsen ML, Trembler KA, Battaglia FC, Wilkening RB, Anthony RV. The relationship between transplacental O2 diffusion and placental expression of PlGF, VEGF and their receptors in a placental insufficiency model of fetal growth restriction. J Physiol 550: 641–656, 2003. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.039511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Regnault TR, de Vrijer B, Galan HL, Wilkening RB, Battaglia FC, Meschia G. Development and mechanisms of fetal hypoxia in severe fetal growth restriction. Placenta 28: 714–723, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roseboom TJ, van der Meulen JH, Osmond C, Barker DJ, Ravelli AC, Schroeder-Tanka JM, van Montfrans GA, Michels RP, Bleker OP. Coronary heart disease after prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine, 1944-45. Heart 84: 595–598, 2000. doi: 10.1136/heart.84.6.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rozance PJ, Zastoupil L, Wesolowski SR, Goldstrohm DA, Strahan B, Cree-Green M, Sheffield-Moore M, Meschia G, Hay WW Jr, Wilkening RB, Brown LD. Skeletal muscle protein accretion rates and hindlimb growth are reduced in late gestation intrauterine growth-restricted fetal sheep. J Physiol 596: 67–82, 2018. doi: 10.1113/JP275230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Semenza GL. Oxygen-dependent regulation of mitochondrial respiration by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Biochem J 405: 1–9, 2007. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soto SM, Blake AC, Wesolowski SR, Rozance PJ, Barthel KB, Gao B, Hetrick B, McCurdy CE, Garza NG, Hay WW Jr, Leinwand LA, Friedman JE, Brown LD. Myoblast replication is reduced in the IUGR fetus despite maintained proliferative capacity in vitro. J Endocrinol 232: 475–491, 2017. doi: 10.1530/JOE-16-0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sugden MC, Kraus A, Harris RA, Holness MJ. Fibre-type specific modification of the activity and regulation of skeletal muscle pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK) by prolonged starvation and refeeding is associated with targeted regulation of PDK isoenzyme 4 expression. Biochem J 346: 651–657, 2015. doi: 10.1042/bj3460651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun W, Xie Z, Liu Y, Zhao D, Wu Z, Zhang D, Lv H, Tang S, Jin N, Jiang H, Tan M, Ding J, Luo C, Li J, Huang M, Geng M. JX06 selectively inhibits pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase PDK1 by a covalent cysteine modification. Cancer Res 75: 4923–4936, 2015. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tao R, Xiong X, Harris RA, White MF, Dong XC. Genetic inactivation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinases improves hepatic insulin resistance induced diabetes. PLoS One 8: e71997, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thorn S, Rozance PJ, Friedman JE, Hay WW, Brown LD. Evidence for increased Cori cycle activity in IUGR fetus (Abstract). Pediatr Res 74: 481, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thorn SR, Brown LD, Rozance PJ, Hay WW Jr, Friedman JE. Increased hepatic glucose production in fetal sheep with intrauterine growth restriction is not suppressed by insulin. Diabetes 62: 65–73, 2013. doi: 10.2337/db11-1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thorn SR, Regnault TR, Brown LD, Rozance PJ, Keng J, Roper M, Wilkening RB, Hay WW Jr, Friedman JE. Intrauterine growth restriction increases fetal hepatic gluconeogenic capacity and reduces messenger ribonucleic acid translation initiation and nutrient sensing in fetal liver and skeletal muscle. Endocrinology 150: 3021–3030, 2009. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Venhoff N, Lebrecht D, Pfeifer D, Venhoff AC, Bissé E, Kirschner J, Walker UA. Muscle-fiber transdifferentiation in an experimental model of respiratory chain myopathy. Arthritis Res Ther 14: R233, 2012. doi: 10.1186/ar4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang YX, Zhang CL, Yu RT, Cho HK, Nelson MC, Bayuga-Ocampo CR, Ham J, Kang H, Evans RM. Regulation of muscle fiber type and running endurance by PPARδ. PLoS Biol 2: e294, 2004. [Erratum in PLoS Biol 3: e61, 2005]. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Waterhouse C, Keilson J. Cori cycle activity in man. J Clin Invest 48: 2359–2366, 1969. doi: 10.1172/JCI106202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wesolowski SR, Hay WW Jr. Role of placental insufficiency and intrauterine growth restriction on the activation of fetal hepatic glucose production. Mol Cell Endocrinol 435: 61–68, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu P, Inskeep K, Bowker-Kinley MM, Popov KM, Harris RA. Mechanism responsible for inactivation of skeletal muscle pyruvate dehydrogenase complex in starvation and diabetes. Diabetes 48: 1593–1599, 1999. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.8.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yankovskaya V, Horsefield R, Törnroth S, Luna-Chavez C, Miyoshi H, Léger C, Byrne B, Cecchini G, Iwata S. Architecture of succinate dehydrogenase and reactive oxygen species generation. Science 299: 700–704, 2003. doi: 10.1126/science.1079605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yates DT, Cadaret CN, Beede KA, Riley HE, Macko AR, Anderson MJ, Camacho LE, Limesand SW. Intrauterine growth-restricted sheep fetuses exhibit smaller hindlimb muscle fibers and lower proportions of insulin-sensitive Type I fibers near term. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 310: R1020–R1029, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00528.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yates DT, Clarke DS, Macko AR, Anderson MJ, Shelton LA, Nearing M, Allen RE, Rhoads RP, Limesand SW. Myoblasts from intrauterine growth-restricted sheep fetuses exhibit intrinsic deficiencies in proliferation that contribute to smaller semitendinosus myofibres. J Physiol 592: 3113–3125, 2014. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.272591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yates DT, Macko AR, Nearing M, Chen X, Rhoads RP, Limesand SW. Developmental programming in response to intrauterine growth restriction impairs myoblast function and skeletal muscle metabolism. J Pregnancy 2012: 631038, 2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/631038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yeaman SJ, Hutcheson ET, Roche TE, Pettit FH, Brown JR, Reed LJ, Watson DC, Dixon GH. Sites of phosphorylation on pyruvate dehydrogenase from bovine kidney and heart. Biochemistry 17: 2364–2370, 1978. doi: 10.1021/bi00605a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]