Abstract

The main goal of this study was to compare the impact of total body leptin deficiency with neuronal-specific leptin receptor (LR) deletion on metabolic and cardiovascular regulation. Liver fat, diacylglycerol acyltransferase-2 (DGTA2), and CD36 protein content were measured in wild-type (WT), nervous system LR-deficient (LR/Nestin-Cre), and leptin deficient (ob/ob) mice. Blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR) were recorded by telemetry, and motor activity (MA) and oxygen consumption (V̇o2) were monitored at 24 wk of age. Female and male LR/Nestin-Cre and ob/ob mice were heavier than WT mice (62 ± 5 and 61 ± 3 vs. 31 ± 1 g) and hyperphagic (6.2 ± 0.5 and 6.1 ± 0.7 vs. 3.5 ± 1.0 g/day), with reduced V̇o2 (27 ± 1 and 33 ± 1 vs 49 ± 3 ml·kg−1·min−1) and decreased MA (3 ± 1 and 7 ± 2 vs 676 ± 105 cm/h). They were also hyperinsulinemic and hyperglycemic compared with WT mice. LR/Nestin-Cre mice had high levels of plasma leptin, while ob/ob mice had undetectable leptin levels. Despite comparable obesity, LR/Nestin-Cre mice had lower liver fat content, DGTA2, and CD36 protein levels than ob/ob mice. Male WT, LR/Nestin-Cre, and ob/ob mice exhibited similar BP (111 ± 3, 110 ± 1 and 109 ± 2 mmHg). Female LR/Nestin-Cre and ob/ob mice, however, had higher BP than WT females despite similar metabolic phenotypes compared with male LR/Nestin-Cre and ob/ob mice. These results indicate that although nervous system LRs play a crucial role in regulating body weight and glucose homeostasis, peripheral LRs regulate liver fat deposition. In addition, our results suggest potential sex differences in the impact of obesity on BP regulation.

Keywords: appetite, blood pressure, body weight, energy balance, fatty liver, glucose, hypertension

INTRODUCTION

Leptin modulates appetite, energy expenditure, insulin action, and lipid metabolism and is a major regulator of body weight. Leptin deficiency or lack of functional leptin receptors (LR) is associated with severe hyperphagia and reduced energy expenditure (4, 20, 28), whereas overexpression of the leptin gene or leptin infusion reduces food intake and increases energy expenditure due to increased sympathetic nerve system (SNS) activity to thermogenic tissue such as brown adipose tissue (20, 35). The importance of leptin in regulating glucose and fat metabolism is evident by the fact that patients with leptin gene mutations or lipodystrophy who have low circulating leptin levels are severely insulin resistant, and leptin replacement markedly improves insulin sensitivity, restores glycemic control, and reduces triglycerides, cholesterol and liver steatosis (32, 33).

We and others have shown that leptin regulates glucose metabolism by direct actions on the central nervous system (CNS) (12, 19, 22, 23) via activation of proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons and subsequent stimulation of melanocortin 4 receptors (MC4R) (11, 14, 38). Previous studies, however, suggest that the glucose-lowering actions of leptin may be partially mediated by direct leptin signaling in peripheral tissues (4). Bates et al. (2) showed that leptin mimics the effects of insulin on glucose transport and glycogen synthesis by activating phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and insulin substrate (IRS)-2 in skeletal muscle cells in vitro. In addition, increases in muscle glycogen synthesis and glucose uptake were found in isolated rodent soleus muscle treated with leptin alone or in combination with insulin (50). These observations suggest that peripheral effects of leptin also increase insulin sensitivity, glucose uptake and utilization, and glycogen synthesis in skeletal muscle. However, most previous studies showing these peripheral effects of leptin on glucose homeostasis have been acute (2, 50), and the relative importance of peripheral and CNS actions of leptin in long-term regulation of glucose metabolism is still unclear.

Another important role of leptin is to promote lipolysis and limit ectopic lipid storage in nonadipose tissue such as liver. Previous studies showed that leptin prevents hepatic steatosis in animal models of obesity and dyslipidemia by regulating lipid and glucose metabolism (10, 39, 42). Leptin also suppresses hepatic glucose production and hepatic lipogenesis, and chronic leptin infusion reduces hepatic lipogenic gene expression and decreases liver triglyceride content by stimulating sympathetic activity (48, 50a). However, the role of leptin receptor activation in the liver itself versus leptin’s CNS-mediated actions on liver fat deposition is still not well understood.

Leptin has also been suggested to be an important link between obesity and hypertension (26, 27). Previous studies have demonstrated that leptin administration in male animals increases SNS activity (41) and blood pressure (BP) (45) and that the rise in BP can be completely prevented by adrenergic blockade (12). In addition, despite having severe obesity and many characteristics of metabolic syndrome, leptin-deficient mice (ob/ob mice) and humans do not exhibit hypertension (5, 36, 37, 46). These observations suggest that leptin may be critical for obesity to increase SNA activity and BP. Previous studies also indicate that there may be sex differences in the mechanisms by which leptin increases BP. For instance, mineralocorticoid receptor blockade lowered BP in obese hyperleptinemic female but not male mice (30), suggesting that leptin may regulate BP mainly via adrenergic and aldosterone-dependent mechanisms in male and female animals, respectively. However, to our knowledge, the impact of neuronal-specific LR deletion on BP regulation in male and female animals has not been assessed.

Although leptin deficiency is known to be associated with obesity and liver steatosis, there are still conflicting data on central versus peripheral effects of leptin on lipid and glucose metabolism as well as on cardiovascular regulation. To our knowledge, there have been no previous studies that have directly tested potential differences for the neuronal versus peripheral actions of leptin in regulation of body weight, adiposity, glucose levels, fat liver deposition, and BP. Therefore, we examined the impact of neuronal-specific leptin receptor deletion versus leptin deficiency on metabolic and cardiovascular regulation in male and female mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All experimental protocols and procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS. Mice were placed in a 12-h dark (6 PM to 6 AM) and light (6 AM to 6 PM) cycle and given free access to food and water throughout the study.

Animals.

Male and female LR/Nestin-Cre, ob/ob, and wild-type (WT) mice were used in these studies. LR-Nestin-Cre mice were generated by crossing Nestin-Cre mice that express Cre recombinase in neuronal cells [B6.Cg-Tg (Nes-Cre) 1 kln/J; Jackson Laboratories], with LRflox/flox mice on a mixed 129Sv/J x C57BL/6 background (B6.129P2- LRtm1Rck/J; Jackson Laboratories). The LRflox/flox mice have LoxP-flanked neomycin and thymidine kinase selection cassette inserted 3′ to exon 1. Therefore, crossing Nestin-Cre mice with LRflox/flox mice led to the generation of mice with neuronal LR deficiency. Specificity of nervous system Cre expression has been described previously (1, 3). Male and female leptin-deficient ob/ob and WT (C57BL/6J) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories.

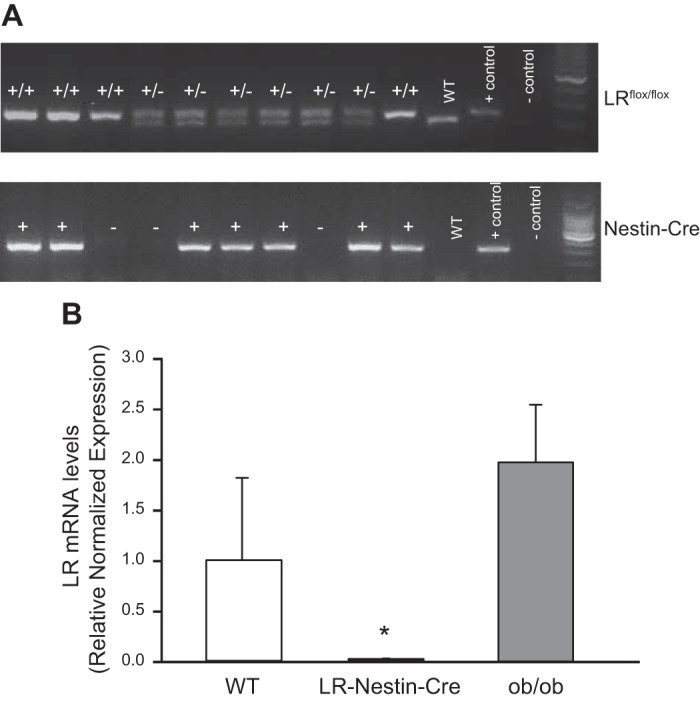

Polymerase chain reaction.

Genotyping was performed as previously described (14, 18). Briefly, after being weaned at 4 wk of age, mice were genotyped using tail snips to perform PCR across the LRflox/flox exon 17 and for Cre-recombinase using the following primers: GTC ACC TAG GTT AAT GTA TTC-3 and 5′-TCT AGC CCT CCA GCA CTG GAC-3 and 5′-CTG CCA CGA CCA AGT GAC AGC-3 (for Cre positive) and 5′-CTT CTC TAC ACC TGC GGT GCT-3 (for Cre negative). Only animals that tested positive for the LRflox/flox and Cre (homozygous) were used as LR/Nestin-Cre mice (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

A: polymerase chain reaction of tail snip samples from leptin receptor (LR)flox/flox homozygous (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), and Nestin-Cre-positive (+) and Nestin-Cre-negative (−) mice. Positive (+) and negative (−) DNA samples and wild-type (WT) samples were used as controls. B: quantitative RT-PCR analysis of LR in hypothalamus of male and female ob/ob and LR/Nestin-Cre mice. *P < 0.05 compared with WT and ob/ob mice.

Food intake, body weight, and body composition.

WT (n = 15), ob/ob (n = 10), and LR/Nestin-Cre (n = 12) mice were individually housed and fed a control diet (170955, 4.0 kcal/g, 13% fat; Harlan Teklad/ENVIGO) starting at 6 wk of age and continuing until the experiments were completed at 25 wk of age. Body weight was measured twice per week from 6 to 20 wk of age. Weekly changes in body composition were analyzed using magnetic resonance imaging (4-in-1 EchoMRI-900TM; Echo Medical Systems, Houston, TX). Food intake was measured daily and averaged weekly.

Oxygen consumption and motor activity measurements.

In separate experiments, WT (n = 6), LR/Nestin-Cre (n = 6), and ob/ob (n = 7) mice at 22 wk of age were placed individually in metabolic cages (AccuScan Instruments, Columbus, OH) equipped with oxygen sensors to measure oxygen consumption (V̇o2) and infrared beams to determine motor activity. V̇o2 was measured for 2 min at 10-min intervals continuously 24 h/day using a Zirconia oxygen sensor. Motor activity was measured using infrared light beams mounted in the cages in the x-, y-, and z-axes. After animals were acclimatized to the metabolic cages for 3 days, V̇o2 and motor activity were measured for 3 consecutive days.

Hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp.

To assess insulin action on glucose utilization in mice lacking LR in the nervous system, WT (n = 5) and LR/Nestin-Cre (n = 6) mice were anesthetized (pentobarbital sodium, 50 mg/kg ip) and implanted with venous catheters into the jugular vein after 5–6 h of fasting. The mice received a continuous infusion of insulin (1.8 mU·kg−1·min−1), and a 10% glucose solution was infused at variable rates as required to maintain euglycemia at ∼8 mM/L. Blood glucose was measured at baseline and every 10 min for a total of 120 min.

Liver composition.

Oil Red O staining was performed in frozen liver sections from WT, LR/Nestin-Cre, and ob/ob mice at 22 wk of age to assess liver lipid content. Sections (10 μm thick) were fixed in formalin for 5 min and stained for 10 min with 0.5% Oil Red O in 60% isopropyl alcohol. The slides were washed five times in water and counterstained in Mayer’s hematoxylin for 30 s and mounted in aqueous mounting media.

Liver triglyceride content in LR/Nestin-Cre and ob/ob mice was analyzed using a fluorimetric quantification assay (Abcam Picoprobe ab178780; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 10-mg liver samples were homogenized and centrifuged, and the supernatant was isolated and diluted. Samples were incubated with lipase at 37°C for 20 min to convert triglyceride to glycerol + fatty acids. Reaction mix was added, and the samples were incubated for an additional 30 min at 37°C protected from light. The samples were read at absorbance Ex/Em = 535/587 nm using a microplate reader.

Western blot analysis.

Liver samples from WT, LR/Nestin-Cre, and ob/ob mice were homogenized in lysis buffer (KPO4, pH 7.4), sonicated, and cleaned by centrifugation (3,500 g for 5 min, 4°C). The supernatant protein concentration was determined as previously described (16). Forty micrograms of protein was separated in a 4–15% precast linear gradient polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad). After being transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, blots were rinsed with PBS and blocked in Odyssey blocking buffer (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE) for 1 h at room temperature, and incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti CD-36 (1:1,000, cat. no. 1333625; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) (7) or goat polyclonal anti-diacylglycerol acyltransferase 2 (DGAT2; 1:1,000; cat. no. 59493; Abcam) (53) overnight at 4°C. Total protein was used as loading control. Membranes were incubated with IR700-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit or anti-goat (1:2,000; Rockland Immunochemicals, Limerick, PA). Antibody labeling was visualized using an Odyssey Infrared Scanner (LI-COR) for detection of fluorprobes, and fluorescence intensity analyses were performed using Odyssey software (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE).

Validation of LR deletion in LR/Nestin-Cre mice.

To confirm neuronal deletion of LR, quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed to examine LR mRNA expression levels in the hypothalamus of male and female LR/Nestin-Cre, ob/ob, and WT mice (n = 5–6/group). Mice were euthanized and the brain quickly removed and frozen by immersion in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. The hypothalamus was isolated and total RNA was extracted using a SuperScript VILO cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). qRT-PCR was performed in 1 ng of RNA using a StepOne Plus qRT-PCR system with PowerUP SYBR green master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The primer pairs 5′GCTCTTCTGATGTATTTGGAAATC-3′ (forward) and CTGATATTGAAGCGGAAATGGT-3′ (reverse) were used to amplify mouse LR. Mouse 18S rRNA was used as internal control to normalize expression levels, and the ΔΔCT method was used to calculate the fold changes of LR mRNA in LR/Nestin-Cre and ob/ob compared with WT control mice (Fig. 1B).

Measurement of blood pressure and heart rate.

At 20 wk of age, male and female WT, LR/Nestin-Cre, and ob/ob mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane, and under aseptic conditions a telemetry probe (TA11PA-C10; Data Science) was implanted in the left carotid artery and advanced into the aorta. Seven to 10 days after recovery from surgery, mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) were measured 24 h/day for 4 consecutive days using computerized methods for data collection, as previously described (14, 16). Daily MAP and HR were obtained from the average of 12:12-h light-dark cycles.

Blood samples (500 μl) were collected by cardiac puncture at euthanasia after 6 h of fasting (8 AM to 2 PM) for measurement of blood glucose and plasma leptin, insulin, and aldosterone levels.

Acute air jet stress test.

To determine whether neuronal deletion of LR alters MAP and HR responses to acute stress, male and female WT, LR/Nestin-Cre, and ob/ob mice were placed in special cages used for air-jet stress testing, as previously described (14). Mice were allowed to acclimate to the cages for ≥2 h before stable BP and HR measurements were made for ≥10 min. The air-jet stress was then administered in 5-s pulses every 10 s for 5 min, whereas BP and HR were measured continuously. Changes in BP and HR to this acute stress were quantified by subtracting the average baseline measurement from the average measurement recorded during the acute stress.

Blockade of adrenergic receptors, mineralocorticoid receptors, and angiotensin II receptor.

To examine the contribution of sympathetic activity to BP regulation in female LR/Nestin-Cre and ob/ob mice, the α1- and β1- and β2-adrenergic receptors were blocked with prazosin and propranolol (7.5 mg/kg each) injected subcutaneously acutely after a 30-min baseline period, and BP and HR measurements were continued for an additional 120 min post-injection. We also investigated the contribution of mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) activation to BP regulation in female LR/Nestin-Cre and ob/ob mice by administering spironolactone for 3 consecutive days (100 mg/kg; drinking ORA-PLUS, Perrigo, MI) after 5 days of baseline measurements. In addition, we investigated the contribution of angiotensin II receptor (AT1) activation to BP regulation in female LR/Nestin-Cre and ob/ob mice by administering losartan for 3 consecutive days (20 mg/kg, drinking water) after 5 days of baseline measurements.

Plasma insulin, leptin, aldosterone, and glucose measurements.

Plasma insulin (cat. no. 90080; Crystal Chem), leptin (cat. no. MBOO; R & D Systems), and aldosterone (cat. no. KGE016; R & D Systems) concentrations were measured with ELISA kits), and blood glucose concentrations were determined using a glucose meter (ReliOn).

Statistical analyses.

Data are expressed as means ± SE. Significant differences between two groups were determined by Student’s t test. Significant differences between two groups over time were determined by two-way ANOVA, whereas single time point differences among three groups were determined by one-way ANOVA, followed by the Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. A P value of <0.05 indicates a significant difference.

RESULTS

Body weight, body composition, plasma hormones, energy expenditure, and motor activity in male WT, LR/Nestin-Cre, and ob/ob mice.

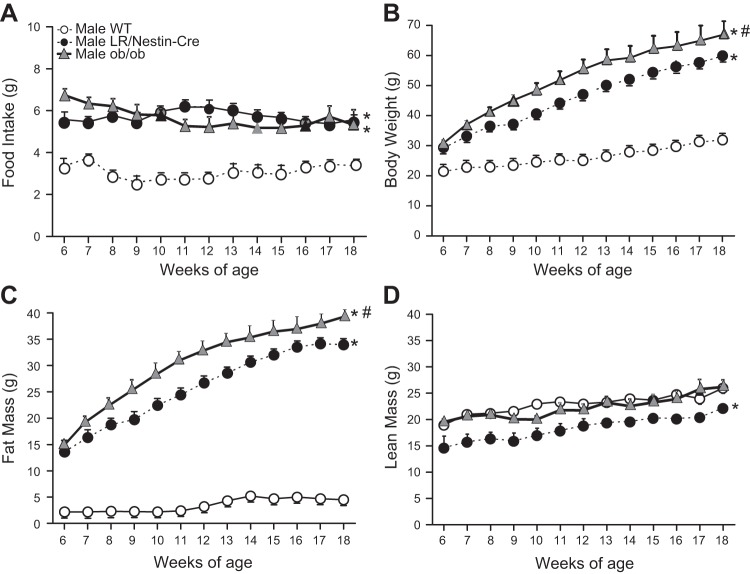

Nervous system deletion of LR was associated with increased food intake and obesity characterized by much higher body fat mass and moderate increases in lean mass compared with control WT mice (Fig. 2, A–D). Food intake and lean mass were similar in LR/Nestin-Cre and ob/ob mice (Fig. 2, A and D); however, body weight and fat mass were slightly but significantly higher in ob/ob mice compared with LR/Nestin-Cre mice (Fig. 2, B and C). These findings suggest that the effects of leptin on food intake and body weight regulation are mediated primarily through leptin’s effect in the CNS.

Fig. 2.

Food intake (A), body weight (B), fat mass (C), and lean mass (D) in male leptin receptor (LR)/Nestin-Cre (n = 5), ob/ob (n = 5), and wild-type (WT; n = 5) mice. *P < 0.05 compared with WT control mice. #P < 0.05, ob/ob compared with LR/Nestin-Cre mice.

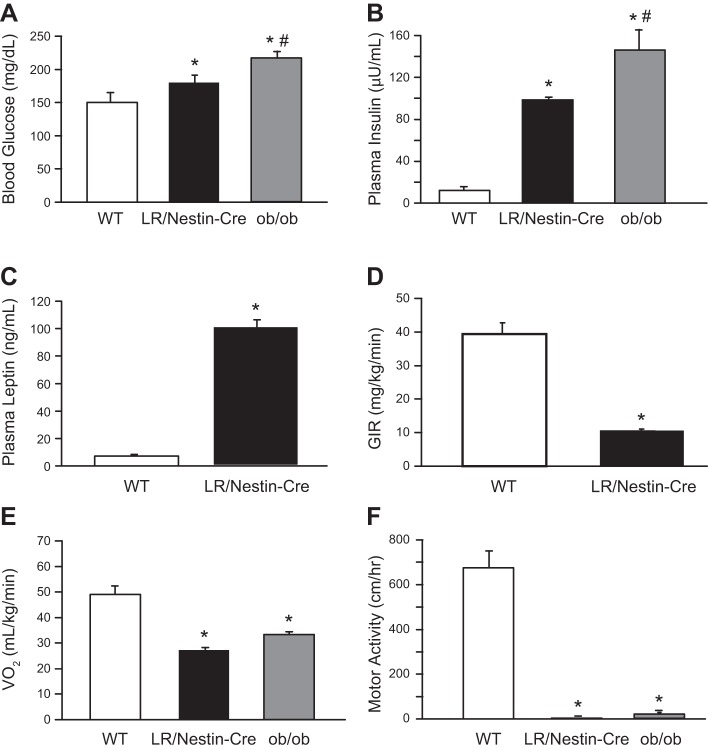

Blood glucose and plasma insulin and leptin concentrations were significantly increased in LR/Nestin-Cre mice compared with controls (Fig. 3, A–C). LR/Nestin-Cre mice also exhibited impaired insulin sensitivity during a euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp compared with WT mice (Fig. 3D). During the hyperinsulinemic clamp, the glucose infusion rate (GIR) needed to maintain euglycemia was significantly lower in LR/Nestin-Cre compared with WT mice, indicating that mice lacking LR in the nervous system but with high levels of circulating leptin are severely insulin resistant. In addition, we found that ob/ob mice had significantly higher plasma glucose and insulin concentrations compared with WT control and LR/Nestin-Cre mice (Fig. 3, A and B).

Fig. 3.

A and B: plasma glucose (A) and insulin concentrations (B) in male leptin receptor (LR)/Nestin-Cre (n = 5), ob/ob (n = 5), and wild-type (WT; n = 5) mice. C and D: plasma leptin concentration (C) and glucose infusion rate (GIR; D) during hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp in male LR/Nestin-Cre and WT mice. E and F: oxygen consumption (V̇o2; E) and motor activity (F) in male LR/Nestin-Cre, ob/ob, and WT mice. *P < 0.05 compared with WT control mice; #P < 0.05 ob/ob compared with LR/Nestin-Cre mice.

LR/Nestin-Cre and ob/ob mice showed similar reductions in V̇o2 and motor activity compared with WT controls (Fig. 3, E and F).

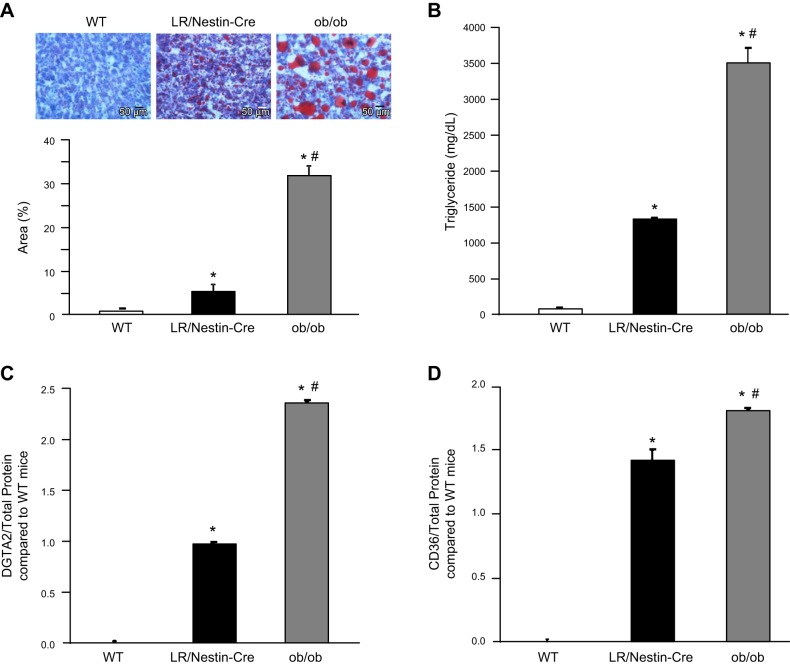

Impact of neuronal-specific LR deficiency on liver lipid accumulation.

Livers from ob/ob mice weighed significantly more than livers from LR/Nestin-Cre and WT mice (4.8 ± 0.4 vs. 3.5 ± 0.2 and 1.5 ± 0.6 g, respectively). When compared with WT mice, LR/Nestin-Cre and ob/ob mice had significantly more liver fat accumulation measured by total area of oil Red O staining (Fig. 4A) as well as by triglyceride assay (Fig. 4B). However, ob/ob mice had 3.5-fold more fat in the liver compared with LR/Nestin-Cre (Fig. 4A). Compared with livers from WT mice, livers from ob/ob and LR/Nestin-Cre mice had higher DGTA2 protein (2.3 ± 0.1- vs. 1.0 ± 0.1-fold, Fig. 4C), which is a key enzyme that catalyzes the final step of triglyceride synthesis (49). However, ob/ob mice had double the DGTA2 protein expression compared with LR/Nestin-Cre (Fig. 4C). In addition, the scavenger receptor CD36 (fatty acid translocase) protein levels were also significantly higher in livers from ob/ob than from LR/Nestin-Cre mice (1.8 ± 0.1- vs. 1.4 ± 0.1-fold; Fig. 4D) compared with livers from WT mice, suggesting that high circulating leptin levels reduced liver fat infiltration and attenuated liver DGTA2 and CD36 protein expression.

Fig. 4.

Oil Red O staining and percent area in liver samples (A), liver triglyceride concentration (B), diacylglycerol acyltransferase-2 (DGTA2) protein levels (C), and CD36 protein levels (D) in wild-type (WT; n = 6), leptin receptor (LR)/Nestin-Cre (n = 7), and ob/ob mice (n = 5). *P < 0.05 compared with WT control mice; #P < 0.05 compared with LR/Nestin-Cre mice.

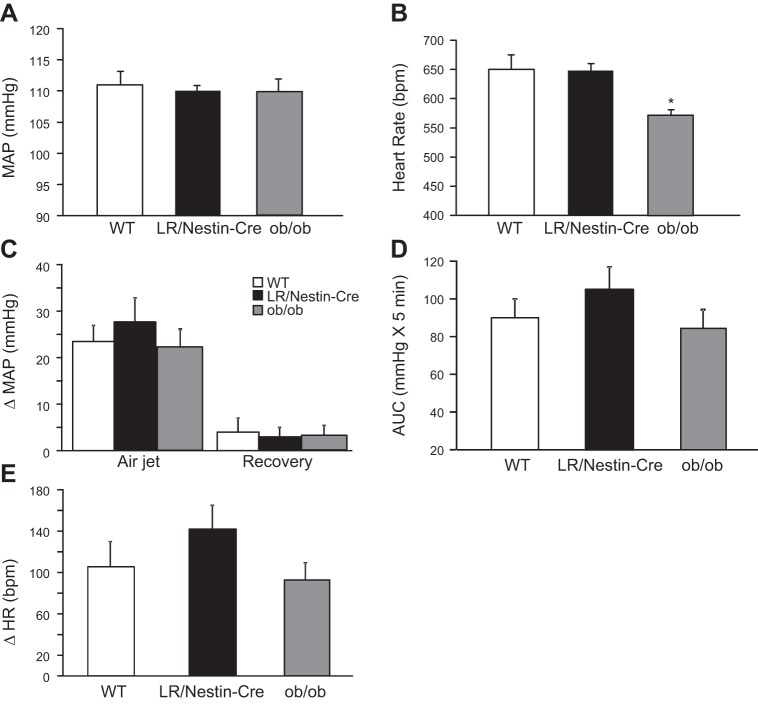

Impact of neuronal-specific LR deficiency on blood pressure and heart rate in male mice.

Compared with control male mice, neuronal-specific LR deficiency in male mice did not significantly alter MAP or HR (Fig. 5, A and B). However, HR was significantly reduced in male ob/ob mice compared with LR/Nestin-Cre and control mice (Figs. 5, A and B).

Fig. 5.

A and B: mean arterial pressure (MAP; A) and heart rate (HR; B) in leptin receptor (LR)/Nestin-Cre (n = 5), ob/ob (n = 5), and wild-type (WT; n = 5) male mice. C–E: changes in MAP (C), area under curve (AUC; D), and HR (E) during acute air jet stress and recovery period in LR/Nestin-Cre, ob/ob, and WT male mice. *P < 0.05 compared with LR/Nestin-Cre and WT control mice.

Impact of neuronal-specific LR deficiency on blood pressure and heart rate responses to acute stress in male mice.

Prestress resting MAP was not different in male LR/Nestin-Cre and ob/ob mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 5A), and the rise in MAP during the acute stress was not statistically different in any of the three groups (28 ± 5, 20 ± 3, and 23 ± 4 mmHg, respectively) (Fig. 5C), as evident when analyzing the area under the curve (AUC) of BP during the stress period (Fig. 5D). Similar findings were observed for HR responses to acute stress (Fig. 5E).

Impact of neuronal-specific LR deficiency on body weight, body composition, plasma hormones, energy expenditure, and motor activity in female mice.

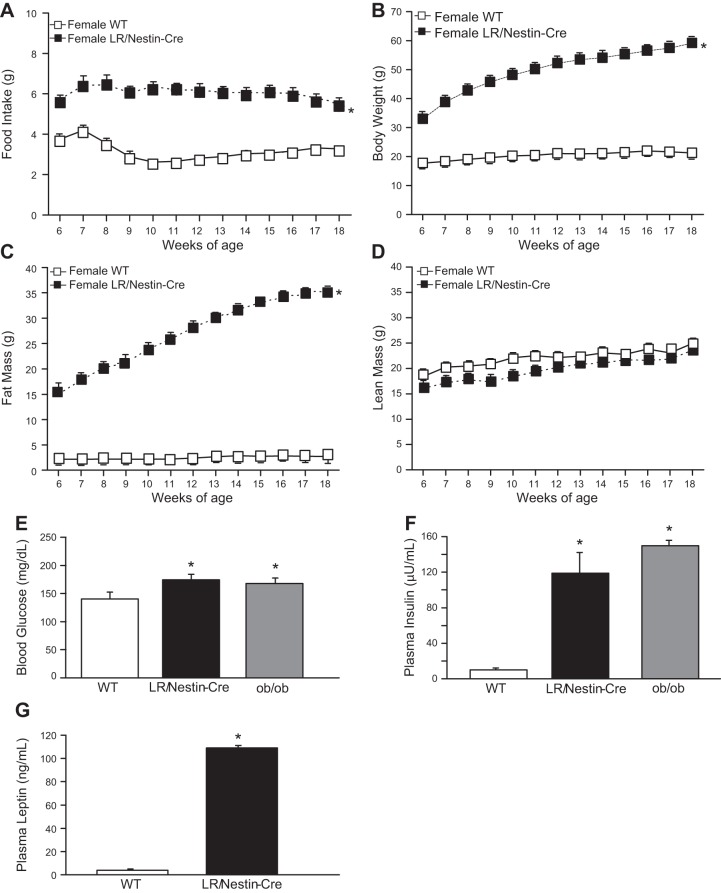

Similar to males, female mice with deletion of LR in the entire nervous system had increased food intake when fed a normal diet from 6 to 18 wk of age as well as higher fat mass and no difference in lean mass compared with WT control mice (Fig. 6, A–D). Blood glucose and plasma insulin and leptin concentrations were significantly increased in female LR/Nestin-Cre mice compared with female WT controls (Figs. 6, E–G).

Fig. 6.

Food intake (A), body weight (B), fat mass (C), lean mass (D), plasma glucose (E), plasma insulin (F), and plasma leptin concentrations (G) in female leptin receptor (LR)/Nestin-Cre (n = 5) and wild-type (WT; n = 6) mice. *P < 0.05 compared with WT control mice.

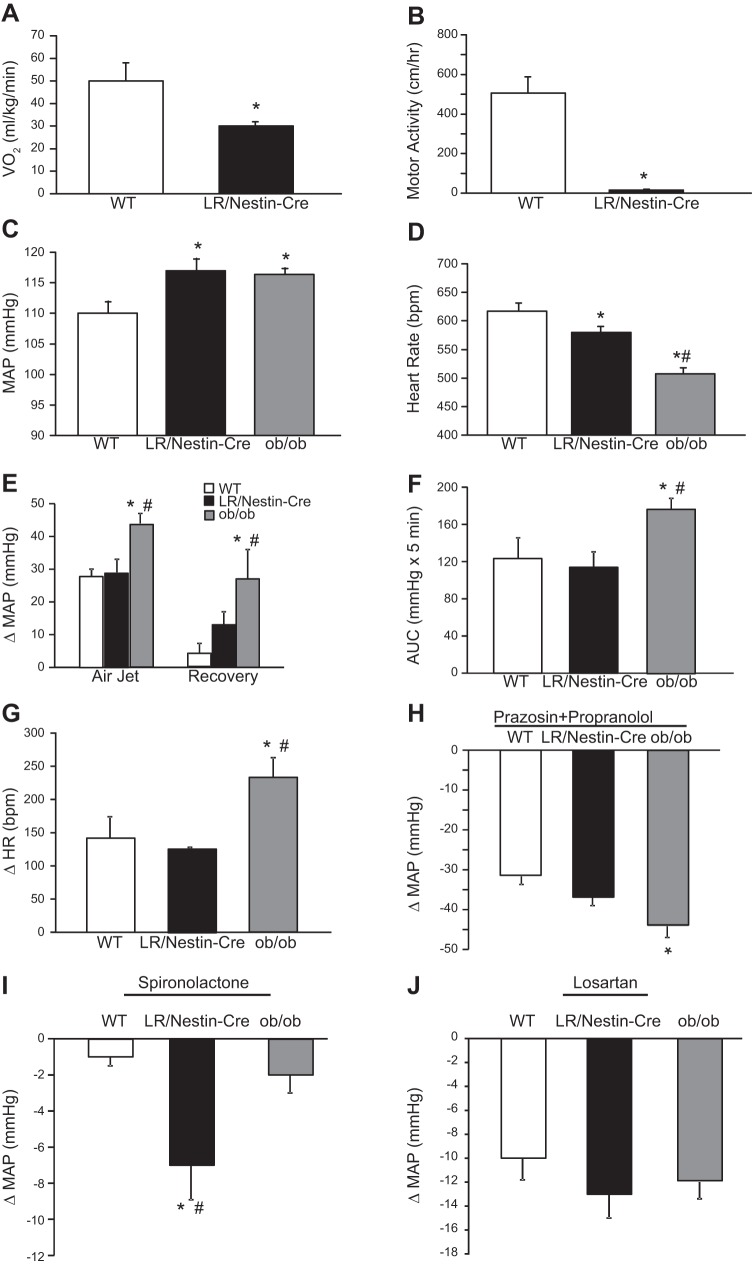

Impact of neuronal-specific LR deficiency on energy expenditure, motor activity, blood pressure, and heart rate in female mice.

Female LR/Nestin-Cre mice showed reduced V̇o2 and motor activity compared with female WT controls (Fig. 7, A and B). Despite similar metabolic profile when compared with male LR/Nestin-Cre mice, MAP was significantly higher and HR significantly lower in female LR/Nestin-Cre mice compared with female controls (Fig. 7, C and D). MAP was also significantly higher and HR significantly lower in female ob/ob mice compared with WT controls (Fig. 7, C and D). This contrasts our observation in male ob/ob and LR/Nestin-Cre mice, which have similar MAP compared with male WT controls. Female ob/ob mice showed augmented BP response to acute air jet stress compared with female WT and LR/Nestin-Cre mice (Fig. 7E), which is also evident when the AUC is analyzed (Fig. 7F). Similar findings were observed for HR responses to acute stress, where female ob/ob mice exhibited greater HR responses compared with female WT and LR/Nestin-Cre mice (Fig. 7H).

Fig. 7.

A and B: oxygen consumption (V̇o2; A) and motor activity (B) in female leptin receptor (LR)/Nestin-Cre (n = 5) and wild-type (WT; n = 6) mice. C–J: mean arterial pressure (MAP; C), heart rate (HR; D), changes in MAP (E), area under the curve (AUC; F), changes in HR during acute air jet stress and recovery period (G), changes in MAP in response to prazosin and propranolol (H), changes in MAP in response to spironolactone (I), and changes in MAP in response to losartan (J) in female ob/ob (n = 5), LR/Nestin-Cre (n = 5), and WT mice (n = 5). *P < 0.05 compared with WT control mice; #P < 0.05, ob/ob compared with LR/Nestin-Cre mice.

To better understand the mechanisms responsible for higher BP observed in female ob/ob and LR/Nestin-Cre mice, we examined their responses to adrenergic receptor, MR, and AT1 receptor blockade. Combined administration of propranolol and prazosin caused greater reduction of BP in female ob/ob mice compared with LR/Nestin-Cre and WT controls (Fig. 7H). In contrast, MR antagonism with spironolactone for 3 days significantly reduced MAP in female LR/Nestin-Cre (118 ± 3 vs. 111 ± 2 mmHg; Fig. 7I) but not in female ob/ob mice or WT mice. AT1 receptor antagonism for 3 consecutive days reduced BP similarly in all 3 groups (Fig. 7J).

Impact of neuronal-specific LR deficiency on plasma aldosterone concentration in female mice.

Because MR antagonism evoked greater BP reduction in female LR/Nestin-Cre mice, we compared baseline aldosterone levels in female mice and found that female LR/Nestin-Cre mice had ∼11-fold higher plasma aldosterone concentration compared with female WT mice (707 ± 97 vs. 69 ± 11 pg/mL), whereas female ob/ob mice showed only modest increased aldosterone levels (165 ± 10 pg/mL).

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated that neuronal-specific LR deficiency is associated with severe obesity and many metabolic abnormalities that are, in most cases, similar to those observed in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice. However, despite severe obesity, similar to what is observed in mice with leptin deficiency, mice with neuronal LR deficiency had attenuated liver fat accumulation, as evidenced by reductions in lipid droplets, triglyceride content, and CD36 and DGTA2 protein levels. Mice with neuronal LR deficiency and very high levels of circulating leptin also showed less severe elevations in plasma glucose and insulin concentrations when compared with leptin-deficient ob/ob mice, suggesting that leptin also regulates liver fat accumulation and glucose homeostasis via its actions on peripheral tissues.

Another important finding of our study was that female LR/Nestin-Cre mice had elevated BP and plasma aldosterone concentration compared with lean female WT controls, whereas no differences in BP were observed in male LR/Nestin-Cre mice compared with male controls or male ob/ob mice. We also found elevated BP in female ob/ob mice, which was independent of MR or AT1 receptor activation but mediated at least in part by increased adrenergic activity. These findings indicate important sex differences regarding the impact of neuronal LR deficiency and increases in circulating leptin on BP regulation in obesity.

Leptin deficiency caused slightly greater obesity than did neuronal LR deficiency.

Our results indicate that neuronal LR deficiency significantly increased weight gain in male and female mice, but their obesity was ∼10% less pronounced compared with ob/ob mice. This was due to a smaller increase in fat and lean mass from 6 to 18 wk of age compared with ob/ob mice despite no major differences in oxygen consumption or motor activity measured at 22 wk of age. One possible explanation for these differences is that that LR/Nestin-Cre mice did not have 100% deletion of LR in all neuronal cells. This possibility is difficult to disprove. Alternatively, these observations could suggest that lack of functional LR in the CNS does not recapitulate 100% of the obese phenotype caused by complete leptin deficiency due to peripheral actions of leptin that may influence body weight regulation. The slightly smaller weight gain in LR/Nestin-Cre mice compared with ob/ob mice did not appear to be caused by higher metabolic rate or physical activity, which were similarly lower in both groups compared with WT controls. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that very high levels of leptin in LR/Nestin-Cre mice may have caused subtle increases in metabolic rate, undetectable by our measurements, that contributed to body weight regulation in this group.

Leptin deficiency and neuronal LR deficiency caused similar reductions in motor activity.

Our observation that ob/ob and LR/Nestin-Cre mice have reduced physical activity is in accordance with previous studies showing that leptin has important effects on motor activity. In ob/ob mice, leptin replacement therapy increased locomotor activity before substantial weight loss (9), and unilateral rescue of LR in the arcuate nucleus improved motor activity in LR-null mice (31). In addition, rescuing LR only in proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons in db/db mice normalized locomotor activity, with modest effects on body weight (31), suggesting that leptin’s actions on motor activity may be at least partly independent of weight loss and mediated by activation of LR in the nervous system.

Leptin deficiency and neuronal LR deficiency caused impaired glucose metabolism.

As expected, leptin deficiency and neuronal LR deletion were associated with marked elevations in fasting blood glucose and plasma insulin levels and insulin resistance compared with control mice. LR deletion, however, was also associated with large increases in plasma leptin concentration, and LR/Nestin-Cre mice exhibited significantly attenuated hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia compared with ob/ob mice. In previous studies, we showed that leptin exerts powerful antidiabetic effects via activation of LR in the CNS (12, 19). Our finding in the present study that LR/Nestin-Cre mice exhibited significantly less hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia compared with ob/ob mice suggests that nonneuronal actions of leptin may also contribute to regulation of glucose metabolism. Although it is possible that the small differences in glucose regulation observed in ob/ob and LR/Nestin-Cre mice may be due to slight differences in adiposity, it is clear from these studies that neuronal actions of leptin play a dominant role in glucose regulation.

Leptin deficiency caused greater hepatic steatosis than did neuronal LR deficiency.

One of the most striking differences we observed between LR/Nestin-Cre and ob/ob mice that does not appear to be mediated by the less pronounced obesity of LR/Nestin-cre mice is the degree of hepatic steatosis. Mice with neuron LR deficiency had only approximately one-third the accumulation of lipids in their liver compared with ob/ob mice. In addition, the lipid droplets were much smaller in LR/Nestin-Cre mice, suggesting that high circulating leptin levels conferred substantial protection against fatty liver disease despite lack of LR in the nervous system.

Although the precise mechanisms responsible for this marked reduction in liver fat accumulation in these morbidly obese mice are still unclear, we found reduced DGTA2 and CD36 protein in LR/Nestin-Cre compared with ob/ob mice. These proteins are important regulators of free fatty acid (FFA) uptake and TG incorporation into lipid droplets, and their higher expression in ob/ob mice may contribute to the excess lipid accumulation in these mice. Previous studies have also demonstrated an important CNS-mediated effect of leptin to decrease expression of lipogenic genes and hepatic TG content via activation of hypothalamic LR, leading to stimulation of SNA activity to the liver (50a). For instance, Suzuki et al. (49) showed that intracerebroventricular infusion of leptin reduces DGTA2 expression in white adipose tissue from ob/ob mice, and suppression of DGTA2 function has been demonstrated to reduce diet-induced steatosis and insulin resistance (7). Mice with CD36 deficiency are also resistant to hepatic steatosis (53). Our results suggest that, in addition to its effects on the CNS to regulate liver fat accumulation, leptin may also exert direct effects on the liver to reduce expression of proteins involved in FFA uptake and incorporation into lipid droplets, contributing to less severe steatosis in LR/Nestin-Cre mice.

Sex differences in BP responses to neuronal LR deficiency.

Leptin has also been suggested to be an important link between obesity, increased SNS activity, and hypertension (25, 27). Rahmouni and colleagues (40, 41) showed that diet-induced obesity leads to resistance to the metabolic actions of leptin but that the renal sympathetic responses to leptin administration are preserved, suggesting selective leptin resistance in diet-induced obesity and hypertension. However, the impact of leptin on SNS activity and BP in females is still poorly understood, although recent studies suggest sex differences regarding the mechanisms by which leptin modulates BP (30). In male rodents, leptin increases SNS activity, and BP and the chronic BP effects of leptin can be prevented by adrenergic receptor blockade (6). In the present study, we found that male ob/ob mice have normal BP despite severe obesity and many other metabolic abnormalities that are usually associated with hypertension. We also observed normal BP and similar BP and HR responses to acute stress in male LR/Nestin-Cre mice compared with WT controls, suggesting that functional LRs in the nervous system are required for obesity to be associated with increased in SNA and elevated BP in male mice. On the other hand, female LR/Nestin-Cre and ob/ob mice had higher baseline BP compared with lean WT female controls. These observations strongly support the notion of sex differences in the effect of neuronal LR deficiency and obesity on BP regulation in mice.

One potential explanation for this sex difference is that in males lack of LR in the nervous system markedly attenuates the impact of excess weight gain to increase SNA, a leading factor contributing to hypertension (13, 24), whereas in females the high circulating levels of leptin and activation of LR in non-neuronal tissues may trigger other hypertensive factors such as increased aldosterone secretion (30). In fact, we observed an 11-fold elevation in aldosterone levels in female LR/Nestin-Cre mice compared with controls. Although previous studies showed normal or even lower BP in female ob/ob mice (8, 44), we found higher baseline BP measured by telemetry, which was associated with higher sympathetic tone. These observations suggest that in female mice, obesity-induced hypertension is complex and may involve different mechanisms, including SNS activity and MR activation in a leptin-dependent and -independent manner. For instance, we observed elevated aldosterone levels and augmented BP response to MR blockade in female LR/Nestin-Cre mice compared with female lean controls and ob/ob mice, whereas female ob/ob mice exhibited greater BP reduction during adrenergic receptor blockade compared with the other groups of female mice. The precise mechanisms for increased sympathetic tone in female ob/ob mice and for increased aldosterone levels and BP response to MR blockade in female LR/Nestin-Cre mice are still unclear and require further investigation.

Previous studies in males indicate that the chronic effects of leptin on sympathetic activity, BP, insulin, and glucose regulation are mediated at least in part by activation of LR in POMC neurons located in the forebrain and hindbrain (14), whereas leptin’s effects on appetite, energy expenditure, and body weight regulation are mediated mainly by activation of LR in other neuronal populations (21, 47, 51). In addition, deletion of LR in astrocytes leads to remodeling of hypothalamic circuitry and reduces the anorexic effect of leptin (29, 34, 43), suggesting that interactions between glial and neuronal cells are involved in the control of energy balance by leptin. Whether the potential sex differences observed in the present study are mediated via activation of LR in different neuronal populations or to stimulation of peripheral LR remains unclear and will require further investigation.

Perspectives and Significance

Our results indicate that neuronal LR deletion causes marked obesity and impaired glucose homeostasis without significantly altering BP or HR in male mice. However, obesity induced by neuronal LR deletion in female mice was associated with increased plasma aldosterone and BP compared with WT controls, whereas male mice with LR deletion had no significant increase in BP despite severe obesity and associated metabolic abnormalities. Female ob/ob mice also exhibited higher BP compared with lean WT female controls, whereas previous studies have shown that male ob/ob mice have normal or reduced BP compared with WT lean controls. These observations indicate important sex differences in the effect of obesity on BP regulation. Our results also suggest that neuronal LR contributes to the regulation of liver fat deposition, albeit to a lesser degree than peripheral LR activation. Future studies are needed to assess the mechanisms responsible for increased sympathetic nervous system activity in obese females as well as the factors that regulate aldosterone and MR activation via leptin-dependent and leptin-independent mechanisms in obesity.

GRANTS

The authors were supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (P01-HL-51971) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P20-GM-104357 and U54-GM-115428).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.M.d.C. and J.E.H. conceived and designed research; J.M.d.C., F.N.G., S.P.M., and X.D. performed experiments; J.M.d.C. and A.A.d.S. analyzed data; J.M.d.C., A.A.d.S., and J.E.H. interpreted results of experiments; J.M.d.C. prepared figures; J.M.d.C., A.A.d.S., F.N.G., S.P.M., and J.E.H. edited and revised manuscript; J.M.d.C., A.A.d.S., F.N.G., S.P.M., X.D., and J.E.H. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balthasar N, Coppari R, McMinn J, Liu SM, Lee CE, Tang V, Kenny CD, McGovern RA, Chua SC Jr, Elmquist JK, Lowell BB. Leptin receptor signaling in POMC neurons is required for normal body weight homeostasis. Neuron 42: 983–991, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bates SH, Gardiner JV, Jones RB, Bloom SR, Bailey CJ. Acute stimulation of glucose uptake by leptin in l6 muscle cells. Horm Metab Res 34: 111–115, 2002. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-23192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bence KK, Delibegovic M, Xue B, Gorgun CZ, Hotamisligil GS, Neel BG, Kahn BB. Neuronal PTP1B regulates body weight, adiposity and leptin action. Nat Med 12: 917–924, 2006. [Erratum in: Nat Med 16: 237, 2010.]. doi: 10.1038/nm1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bjørbaek C, Kahn BB. Leptin signaling in the central nervous system and the periphery. Recent Prog Horm Res 59: 305–331, 2004. doi: 10.1210/rp.59.1.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown RJ, Meehan CA, Gorden P. Leptin does not mediate hypertension associated with human obesity. Cell 162: 465–466, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlyle M, Jones OB, Kuo JJ, Hall JE. Chronic cardiovascular and renal actions of leptin: role of adrenergic activity. Hypertension 39: 496–501, 2002. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.104398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi CS, Savage DB, Kulkarni A, Yu XX, Liu ZX, Morino K, Kim S, Distefano A, Samuel VT, Neschen S, Zhang D, Wang A, Zhang XM, Kahn M, Cline GW, Pandey SK, Geisler JG, Bhanot S, Monia BP, Shulman GI. Suppression of diacylglycerol acyltransferase-2 (DGAT2), but not DGAT1, with antisense oligonucleotides reverses diet-induced hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. J Biol Chem 282: 22678–22688, 2007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704213200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christoffersen C, Bollano E, Lindegaard ML, Bartels ED, Goetze JP, Andersen CB, Nielsen LB. Cardiac lipid accumulation associated with diastolic dysfunction in obese mice. Endocrinology 144: 3483–3490, 2003. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coppari R, Ichinose M, Lee CE, Pullen AE, Kenny CD, McGovern RA, Tang V, Liu SM, Ludwig T, Chua SC Jr, Lowell BB, Elmquist JK. The hypothalamic arcuate nucleus: a key site for mediating leptin’s effects on glucose homeostasis and locomotor activity. Cell Metab 1: 63–72, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cortés VA, Cautivo KM, Rong S, Garg A, Horton JD, Agarwal AK. Leptin ameliorates insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in Agpat2-/- lipodystrophic mice independent of hepatocyte leptin receptors. J Lipid Res 55: 276–288, 2014. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M045799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.da Silva AA, do Carmo JM, Freeman JN, Tallam LS, Hall JE. A functional melanocortin system may be required for chronic CNS-mediated antidiabetic and cardiovascular actions of leptin. Diabetes 58: 1749–1756, 2009. doi: 10.2337/db08-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.da Silva AA, Tallam LS, Liu J, Hall JE. Chronic antidiabetic and cardiovascular actions of leptin: role of CNS and increased adrenergic activity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291: R1275–R1282, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00187.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davy KP, Orr JS. Sympathetic nervous system behavior in human obesity. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 33: 116–124, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.do Carmo JM, da Silva AA, Cai Z, Lin S, Dubinion JH, Hall JE. Control of blood pressure, appetite, and glucose by leptin in mice lacking leptin receptors in proopiomelanocortin neurons. Hypertension 57: 918–926, 2011. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.161349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.do Carmo JM, da Silva AA, Sessums PO, Ebaady SH, Pace BR, Rushing JS, Davis MT, Hall JE. Role of Shp2 in forebrain neurons in regulating metabolic and cardiovascular functions and responses to leptin. Int J Obes 38: 775–783, 2014. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.do Carmo JM, da Silva AA, Wang Z, Freeman NJ, Alsheik AJ, Adi A, Hall JE. Regulation of blood pressure, appetite, and glucose by leptin after inactivation of insulin receptor substrate 2 signaling in the entire brain or in proopiomelanocortin neurons. Hypertension 67: 378–386, 2016. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.do Carmo JM, Hall JE, da Silva AA. Chronic central leptin infusion restores cardiac sympathetic-vagal balance and baroreflex sensitivity in diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H1974–H1981, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00265.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enriori PJ, Sinnayah P, Simonds SE, Garcia Rudaz C, Cowley MA. Leptin action in the dorsomedial hypothalamus increases sympathetic tone to brown adipose tissue in spite of systemic leptin resistance. J Neurosci 31: 12189–12197, 2011. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2336-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans MC, Anderson GM. Dopamine neuron-restricted leptin receptor signaling reduces some aspects of food reward but exacerbates the obesity of leptin receptor-deficient male mice. Endocrinology 158: 4246–4256, 2017. doi: 10.1210/en.2017-00513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujikawa T, Chuang JC, Sakata I, Ramadori G, Coppari R. Leptin therapy improves insulin-deficient type 1 diabetes by CNS-dependent mechanisms in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 17391–17396, 2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008025107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.German JP, Thaler JP, Wisse BE, Oh-I S, Sarruf DA, Matsen ME, Fischer JD, Taborsky GJ Jr, Schwartz MW, Morton GJ. Leptin activates a novel CNS mechanism for insulin-independent normalization of severe diabetic hyperglycemia. Endocrinology 152: 394–404, 2011. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hall JE. The kidney, hypertension, and obesity. Hypertension 41: 625–633, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000052314.95497.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall JE, da Silva AA, do Carmo JM, Dubinion J, Hamza S, Munusamy S, Smith G, Stec DE. Obesity-induced hypertension: role of sympathetic nervous system, leptin, and melanocortins. J Biol Chem 285: 17271–17276, 2010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.113175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall JE, do Carmo JM, da Silva AA, Wang Z, Hall ME. Obesity-induced hypertension: interaction of neurohumoral and renal mechanisms. Circ Res 116: 991–1006, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall JE, do Carmo JM, da Silva AA, Wang Z, Hall ME. Obesity, kidney dysfunction and hypertension: mechanistic links. Nat Rev Nephrol 15: 367–385, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41581-019-0145-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris RB. Leptin—much more than a satiety signal. Annu Rev Nutr 20: 45–75, 2000. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.20.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsuchou H, He Y, Kastin AJ, Tu H, Markadakis EN, Rogers RC, Fossier PB, Pan W. Obesity induces functional astrocytic leptin receptors in hypothalamus. Brain 132: 889–902, 2009. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huby AC, Otvos L Jr, Belin de Chantemèle EJ. Leptin induces hypertension and endothelial dysfunction via aldosterone-dependent mechanisms in obese female mice. Hypertension 67: 1020–1028, 2016. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huo L, Gamber K, Greeley S, Silva J, Huntoon N, Leng XH, Bjørbaek C. Leptin-dependent control of glucose balance and locomotor activity by POMC neurons. Cell Metab 9: 537–547, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Javor ED, Cochran EK, Musso C, Young JR, Depaoli AM, Gorden P. Long-term efficacy of leptin replacement in patients with generalized lipodystrophy. Diabetes 54: 1994–2002, 2005. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Javor ED, Ghany MG, Cochran EK, Oral EA, DePaoli AM, Premkumar A, Kleiner DE, Gorden P. Leptin reverses nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in patients with severe lipodystrophy. Hepatology 41: 753–760, 2005. doi: 10.1002/hep.20672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim JG, Suyama S, Koch M, Jin S, Argente-Arizon P, Argente J, Liu ZW, Zimmer MR, Jeong JK, Szigeti-Buck K, Gao Y, Garcia-Caceres C, Yi CX, Salmaso N, Vaccarino FM, Chowen J, Diano S, Dietrich MO, Tschöp MH, Horvath TL. Leptin signaling in astrocytes regulates hypothalamic neuronal circuits and feeding. Nat Neurosci 17: 908–910, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nn.3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Labbé SM, Caron A, Lanfray D, Monge-Rofarello B, Bartness TJ, Richard D. Hypothalamic control of brown adipose tissue thermogenesis. Front Syst Neurosci 9: 150, 2015. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2015.00150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mark AL, Shaffer RA, Correia ML, Morgan DA, Sigmund CD, Haynes WG. Contrasting blood pressure effects of obesity in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice and agouti yellow obese mice. J Hypertens 17, Suppl: 1949–1953, 1999. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917121-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Munusamy S, do Carmo JM, Hosler JP, Hall JE. Obesity-induced changes in kidney mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum in the presence or absence of leptin. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 309: F731–F743, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00188.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parton LE, Ye CP, Coppari R, Enriori PJ, Choi B, Zhang CY, Xu C, Vianna CR, Balthasar N, Lee CE, Elmquist JK, Cowley MA, Lowell BB. Glucose sensing by POMC neurons regulates glucose homeostasis and is impaired in obesity. Nature 449: 228–232, 2007. doi: 10.1038/nature06098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petersen KF, Oral EA, Dufour S, Befroy D, Ariyan C, Yu C, Cline GW, DePaoli AM, Taylor SI, Gorden P, Shulman GI. Leptin reverses insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in patients with severe lipodystrophy. J Clin Invest 109: 1345–1350, 2002. doi: 10.1172/JCI0215001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rahmouni K, Haynes WG, Mark AL. Cardiovascular and sympathetic effects of leptin. Curr Hypertens Rep 4: 119–125, 2002. doi: 10.1007/s11906-002-0036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rahmouni K, Haynes WG, Morgan DA, Mark AL. Intracellular mechanisms involved in leptin regulation of sympathetic outflow. Hypertension 41: 763–767, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000048342.54392.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodríguez A, Moreno NR, Balaguer I, Méndez-Giménez L, Becerril S, Catalán V, Gómez-Ambrosi J, Portincasa P, Calamita G, Soveral G, Malagón MM, Frühbeck G. Leptin administration restores the altered adipose and hepatic expression of aquaglyceroporins improving the non-alcoholic fatty liver of ob/ob mice. Sci Rep 5: 12067, 2015. doi: 10.1038/srep12067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rottkamp DM, Rudenko IA, Maier MT, Roshanbin S, Yulyaningsih E, Perez L, Valdearcos M, Chua S, Koliwad SK, Xu AW. Leptin potentiates astrogenesis in the developing hypothalamus. Mol Metab 4: 881–889, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sartori M, Conti FF, Dias DDS, Dos Santos F, Machi JF, Palomino Z, Casarini DE, Rodrigues B, De Angelis K, Irigoyen MC. Association between diastolic dysfunction with inflammation and oxidative stress in females ob/ob mice. Front Physiol 8: 572, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shek EW, Brands MW, Hall JE. Chronic leptin infusion increases arterial pressure. Hypertension 31: 409–414, 1998. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.31.1.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simonds SE, Pryor JT, Cowley MA. Does leptin cause an increase in blood pressure in animals and humans? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 26: 20–25, 2017. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stanley BG. GABA: a cotransmitter linking leptin to obesity prevention. Endocrinology 153: 2057–2058, 2012. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stern JH, Rutkowski JM, Scherer PE. Adiponectin, leptin, and fatty acids in the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis through adipose tissue crosstalk. Cell Metab 23: 770–784, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suzuki R, Tobe K, Aoyama M, Sakamoto K, Ohsugi M, Kamei N, Nemoto S, Inoue A, Ito Y, Uchida S, Hara K, Yamauchi T, Kubota N, Terauchi Y, Kadowaki T. Expression of DGAT2 in white adipose tissue is regulated by central leptin action. J Biol Chem 280: 3331–3337, 2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410955200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sweeney G, Keen J, Somwar R, Konrad D, Garg R, Klip A. High leptin levels acutely inhibit insulin-stimulated glucose uptake without affecting glucose transporter 4 translocation in l6 rat skeletal muscle cells. Endocrinology 142: 4806–4812, 2001. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.11.8496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50a.Tanida M, Yamamoto N, Morgan DA, Kurata Y, Shibamoto T, Rahmouni K. Leptin receptor signaling in the hypothalamus regulates hepatic autonomic nerve activity via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and AMP-activated protein kinase. J Neurosci 35: 474–484, 2015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1828-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vong L, Ye C, Yang Z, Choi B, Chua S Jr, Lowell BB. Leptin action on GABAergic neurons prevents obesity and reduces inhibitory tone to POMC neurons. Neuron 71: 142–154, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilson CG, Tran JL, Erion DM, Vera NB, Febbraio M, Weiss EJ. Hepatocyte-specific disruption of CD36 attenuates fatty liver and improves insulin sensitivity in HFD-fed mice. Endocrinology 157: 570–585, 2016. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]