Abstract

Vasopressin controls water balance largely through PKA-dependent effects to regulate the collecting duct water channel aquaporin-2 (AQP2). Although considerable information has accrued regarding the regulation of water and solute transport in collecting duct cells, information is sparse regarding the signaling connections between PKA and transport responses. Here, we exploited recent advancements in protein mass spectrometry to perform a comprehensive, multiple-replicate analysis of changes in the phosphoproteome of native rat inner medullary collecting duct cells in response to the vasopressin V2 receptor-selective agonist 1-desamino-8D-arginine vasopressin. Of the 10,738 phosphopeptides quantified, only 156 phosphopeptides were significantly increased in abundance, and only 63 phosphopeptides were decreased, indicative of a highly selective response to vasopressin. The list of upregulated phosphosites showed several general characteristics: 1) a preponderance of sites with basic (positively charged) amino acids arginine (R) and lysine (K) in position −2 and −3 relative to the phosphorylated amino acid, consistent with phosphorylation by PKA and/or other basophilic kinases; 2) a greater-than-random likelihood of sites previously demonstrated to be phosphorylated by PKA; 3) a preponderance of sites in membrane proteins, consistent with regulation by membrane association; and 4) a greater-than-random likelihood of sites in proteins with class I COOH-terminal PDZ ligand motifs. The list of downregulated phosphosites showed a preponderance of those with proline in position +1 relative to the phosphorylated amino acid, consistent with either downregulation of proline-directed kinases (e.g., MAPKs or cyclin-dependent kinases) or upregulation of one or more protein phosphatases that selectively dephosphorylate such sites (e.g., protein phosphatase 2A). The phosphoproteomic data were used to create a web resource for the investigation of G protein-coupled receptor signaling and regulation of AQP2-mediated water transport.

Keywords: aquaporin-2, protein kinase, protein phosphatase

INTRODUCTION

Water balance in mammals is regulated largely through the effect of the peptide hormone vasopressin to control the rate of water excretion by the kidney. It does this chiefly through actions in the cells of the renal collecting duct. Vasopressin binds to the V2 receptor and increases osmotic water transport through the regulation of the aquaporin-2 water channel (AQP2) (42). V2 receptor occupation by vasopressin triggers heterotrimeric G protein subunit Gαs-mediated activation of adenylyl cyclase 6 to increase intracellular cAMP levels (Fig. 1) (11, 62). The downstream effects are mediated chiefly by cAMP-dependent activation of the basophilic protein kinase PKA (38), whose catalytic subunits can be coded by either of two separate genes, protein kinase cAMP-activated catalytic subunit-α and -β (Prkaca and Prkacb), respectively. PKA exerts its regulatory actions in cells by phosphorylating serines and threonines at characteristic sites, most frequently in the motif (R/K)-(R/K)-X-p(S/T)-X, where (R/K) means either arginine or lysine, (S/T) means either serine or threonine, p indicates the phosphorylation target, and X means any amino acid (22, 48).

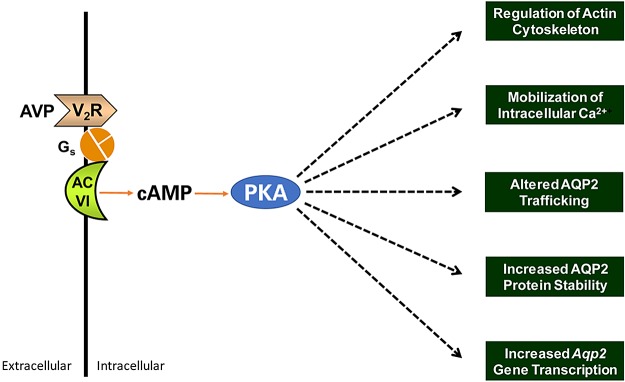

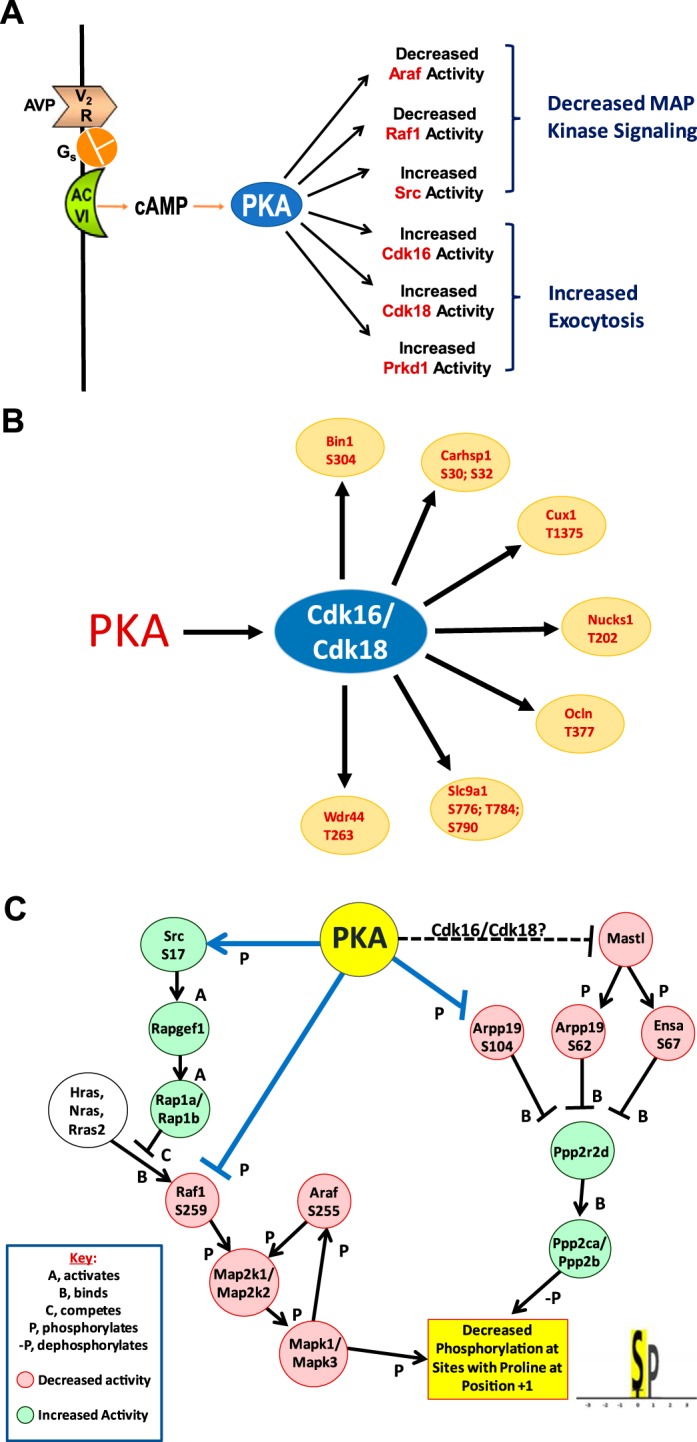

Fig. 1.

Cellular-level physiological responses to vasopressin in aquaporin-2 (AQP2)-expressing cells of the renal collecting duct. See the introduction for literature citations and explanation. AC VI, adenylyl cyclase 6; Gs, G protein subunit Gαs; V2R, vasopressin V2 receptor.

Extensive investigation has shown that vasopressin regulates several cellular processes that have bearing on AQP2-mediated water transport in collecting duct cells (Fig. 1) including membrane trafficking of AQP2 (9, 55, 56, 58), actin cytoskeleton organization (14, 38, 45, 68, 72), transcription of the Aqp2 gene (17, 31, 47, 64, 80), stability of AQP2 protein (54, 65), and phosphorylation of AQP2 protein (18, 25, 34–36, 50). Most of these end effects of vasopressin are presumably consequences of PKA-mediated phosphorylation. However, the signaling steps between PKA and the end effects remain unidentified.

Phosphoproteomic studies done a decade or more ago in native rat inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD) cells (3, 36) and cultured mouse cortical collecting duct (mpkCCD) cells (61) have already revealed a number of vasopressin-regulated phosphorylation events. However, in those previous studies, the overall sensitivity of mass spectrometry severely limited the number of phosphorylation sites that could be reproducibly quantified over multiple replicates. The previous studies provided information mainly about phosphorylation of AQP2 and the vasopressin-regulated urea channel UT-A1 (Slc14a2) and only a limited view of vasopressin signaling. The past few years have seen a remarkable increase in the sensitivity and mass accuracy of the mass spectrometers used for proteomic studies, yielding new opportunities to “dig deeper” into the phosphoproteome, allowing a much more complete picture of vasopressin signaling. Here, we performed deep quantitative phosphoproteomics in native rat IMCDs exposed to the vasopressin V2 receptor-selective agonist 1-desamino-8D-arginine vasopressin (dDAVP) or its vehicle to identify vasopressin-triggered phosphorylation events. The regulated phosphoproteins were mapped to the major cellular processes known to be regulated by vasopressin, which are shown in Fig. 1.

METHODS

IMCD suspensions.

Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 200–250 g were used in accordance with National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Animal Care and Use Committee protocol H-0110R4. To wash out the solutes accumulated in the inner medulla as part of the urinary concentrating mechanism and thus reduce the osmotic shock to the tissue, rats were injected with furosemide (0.5 mg ip) 30 min before euthanasia by decapitation. The inner medullas were dissected out, minced, and digested for 90 min at 37°C in an enzyme solution containing 3 mg/ml collagenase B and 3 mg/ml hyaluronidase dissolved in sucrose buffer (250 mM sucrose and 10 mM triethanolamine, pH 7.6). After digestion, three low-speed spins (70 g, 20 s) were used to pellet IMCD segments. The pellets were rinsed with bicarbonate buffer (118 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 5.5 mM glucose, 5 mM KCl, 4 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM CaCl2, and 1.2 mM MgSO4, pH 7.4 equilibrated with 5% CO2-95% air) and finally resuspended in the same buffer solution. Samples were treated with either the vasopressin V2 receptor-selective agonist dDAVP (1 nM) or vehicle for 30 min at 37°C in a pH- and temperature-controlled chamber. Prior characterization of this protocol showed that by protein amounts, the IMCD fraction consists of 91% IMCD cells and 9% non-IMCD cells (37).

Reduction, alkylation, and in-solution protease digestion.

After dDAVP treatment, IMCDs were harvested by centrifugation (16,000 g, 1 min). The pellets were solubilized in lysis buffer [1% sodium deoxycholate and 50 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB) buffer, pH 7.5] with Halt protease and phosphatase inhibitor mixture (ThermoFisher Scientific) plus protein phosphatase inhibitors NaF (5 mM) and Na vanadate (1 mM). Lysates were sonicated with a 0.5-s pulse/0.5-s rest interval for 1 min followed by centrifugation at 16,000 g for 5 min. The protein concentration in the supernatants was determined using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). One milligram of protein was used for large-scale phosphoproteome profiling. Samples were reduced for 1 h with 10 mM dithiothreitol at 37°C followed by alkylation with 40 mM iodoacetamide for 1 h in the dark at room temperature. Dithiothreitol (40 mM) was added to quench unreacted iodoacetamide. Samples were diluted to a sodium deoxycholate concentration of 0.25% and digested with trypsin/Lys-C (Promega, Madison, WI) overnight at 37°C in 50 mM TEAB.

Desalting and tandem mass tag labeling.

Trifluoroacetic acid (1%) was added to the solution to reach a pH of 2. The solution was vortexed and held for 5 min at room temperature. Samples were centrifuged at 16,000 g for 5 min at 4°C. Peptide samples in the supernatant were desalted using 1-ml hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB) cartridges (Waters, Milford, MA) twice, and peptides were eluted using 70% acetonitrile-0.1% formic acid. Peptide samples were dried and stored at −80°C. The above steps were repeated twice for a total of three experiments. Peptides were subsequently labeled using the TMT10plex Isobaric Label Reagent Set (catalog no. 90110, ThermoFisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. One-hundredth (8 μl) of the sample was saved for total protein analysis, and the sample was used for phosphopeptide analysis. All samples were desalted and dried.

Phosphopeptide enrichment and sample fractionation.

Tandem mass tag (TMT)-labeled peptides were subjected to phosphopeptide enrichment using a ferric nitrilotriacetate (Fe-NTA) kit (A-32992, ThermoFisher Scientific), and the flow through was introduced into a TiO2 kit (A-32993, ThermoFisher Scientific). Eluates from the two enrichments were desalted using a C18 column. Fe-NTA enrichment and TiO2 enrichment fractions were both resuspended in 50 ml of 10 mM TEAB, combined, and subjected to high-pH reversed-phase peptide fractionation.

LC-MS/MS analysis.

Total peptide and phosphopeptide-enriched samples were reconstituted in 0.1% formic acid. LC-MS/MS was performed in an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos mass spectrometer equipped with a Dionex UltiMate 3000 Nano LC system and EASY-Spray ion source. Peptides were applied to a peptide nanotrap at a flow rate of 5 μl/min. The trapped peptides were fractionated with a reversed-phase EASY-Spray PepMap column (C18, 75 μm × 5 cm) using a linear gradient of 4–32% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid. The gradient time was 120 min with a flow rate of 0.3 μl/min. Mass spectrometry spectra were analyzed using Proteome Discoverer 1.4. To obtain comprehensive spectra-peptide matches, we used both SEQUEST and Mascot. The search criteria were set as follows: 1) 10-ppm precursor mass tolerance, 2) 0.02-Da fragment mass tolerance, and 3) two missed cleavages allowed per peptide. Specific amino acid modifications were as follows: 1) the isobaric TMT of lysine (K) or NH2 terminus (+229.163 Da); 2) carbamidomethylation of cysteine (C; +57.021 Da); 3) oxidation of methionine (M; +15.995 Da); 4) deamination on glutamine and asparagine (Q and N, respectively; +0.984 Da); and 5) phosphorylation of serine, threonine, and tyrosine (S, T, and Y, respectively; +79.966 Da). The protein database used was rat Swiss-Prot (July 9, 2017). The false discovery rate was limited to 1% using the target-decoy algorithm. The results from SEQUEST and Mascot searches were integrated in Proteome Discoverer 1.4 with the following filters: false discovery rate < 0.01 and peptide rank = 1. Results are reported as abundance ratios between dDAVP-treated samples and vehicle-treated controls with independent-control observations for each vasopressin-treated sample. Control-to-control ratios were used to characterize the background variability of the method.

Bioinformatics.

Results were analyzed at the level of individual phosphopeptides. Calculations used base-2 log transformation of the abundance ratios. Dual criteria were used to identify phosphopeptides with altered abundance, namely, |log2(dDAVP/vehicle)| > 0.342 and Pjoint < 0.005. A value of 0.342 was assigned to encompass 95% of log2(control/control) values (95% confidence interval for control-to-control comparisons). Pjoint (a measure of false positive probability) for phosphopeptide quantification was calculated as a product of the P value from the t-statistic using all three pairs of dDAVP-vehicle replicates and the area under the Gaussian distribution curve outside the range [−Z, Z], where Z is the value divided by the SD of log2(control/control) values. Although this is a reasonably stringent criterion, it is important to be fairly circumspect in drawing conclusions about specific phosphopeptides since, with multiple testing, some false positives for individual peptides are inevitable. Instead, the general strategy applied here and in another study (42) has been to draw conclusions about groups of proteins that are related by common pathways (e.g., phosphoinositide signaling pathway), common location in the cell (e.g., membrane association), or common protein properties (COOH-terminal PDZ ligand motifs). Such conclusions are robust. That is, they do not depend on the verity of any individual phosphopeptide change in the input data. This principle is widely exploited in systems biology, e.g., in gene set enrichment analysis for transcriptomic data (70).

The consensus motifs for sites that were increased or decreased in abundance were calculated as previously described by Douglass et al. (22) except that the background probabilities used for each amino acid position were assigned in a position-specific manner using frequencies downloaded from PhosphoSitePlus (https://www.phosphosite.org/). PTM Centralizer (https://hpcwebapps.cit.nih.gov/ESBL/PtmCentralizer/) was used to convert monophosphopeptide sequences to centralized 13-amino acid sequences with the phosphorylated amino acid in the middle.

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the Proteomics Identifications (PRIDE) partner repository with the data set identifier PXD011245.

RESULTS

General observations.

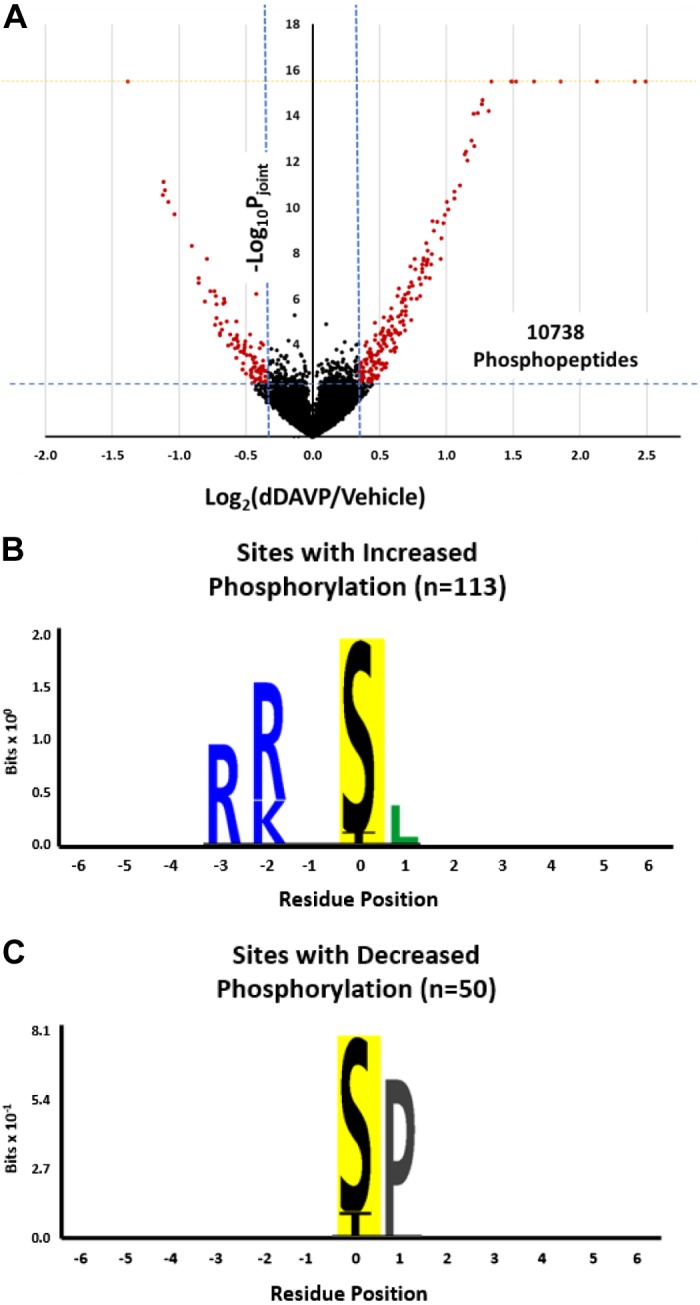

We used TMT labeling to quantify 10,738 distinct phosphopeptides in 2,249 proteins in IMCD suspensions isolated from rat kidneys (Fig. 2A and Supplemental Data Set S1; Supplemental Material for this article is available at https://hpcwebapps.cit.nih.gov/ESBL/Database/IMCDPhos-Supplemental/). Suspensions were exposed to either the V2 receptor-selective vasopressin analog dDAVP (1 nM for 30 min) or its vehicle (30 min). [A prior time-course study showed that the initial increases in phosphorylation occur within 1 min of dDAVP addition but that at least 15 min is required to reach a steady-state response (34).] There were three independent vehicle-treated controls, which were compared to establish the variability of the method independent of the addition of dDAVP. These control-to-control comparisons across all quantified phosphopeptides allowed us to calculate a range of log2(control/control) values that encompass 95% of the control-to-control values (95% confidence interval = ±0.342; see Supplemental Data Set S2). This range was demarcated by the vertical dashed blue lines in Fig. 2A, showing results for all quantified phosphopeptides in all three pairs of dDAVP-vehicle samples. The red points indicate phosphopeptides with log2(dDAVP/vehicle) values outside of this range and with −log10(Pjoint) > 2.30 (horizontal blue dashed line). Of the 10,738 phosphopeptides quantified, 219 phosphopeptides were thus identified as changing in response to dDAVP (red points) including 156 phosphopeptides that were increased and 63 phosphopeptides that were decreased (Supplemental Data Set S3). Full results for all quantified phosphopeptides are available to users at a publicly accessible webpage (https://esbl.nhlbi.nih.gov/IMCD-Phos/). Measurements of total protein abundances showed no effect of vasopressin (Supplemental Data Set S4). Specifically, for the 2,340 proteins quantified, the mean dDAVP-to-vehicle abundance ratio was 1.02 (SD 0.10). Thus, in general, vasopressin-mediated phosphorylation changes reported in this article were due to changes in percent phosphooccupancy rather than changes in total protein abundance.

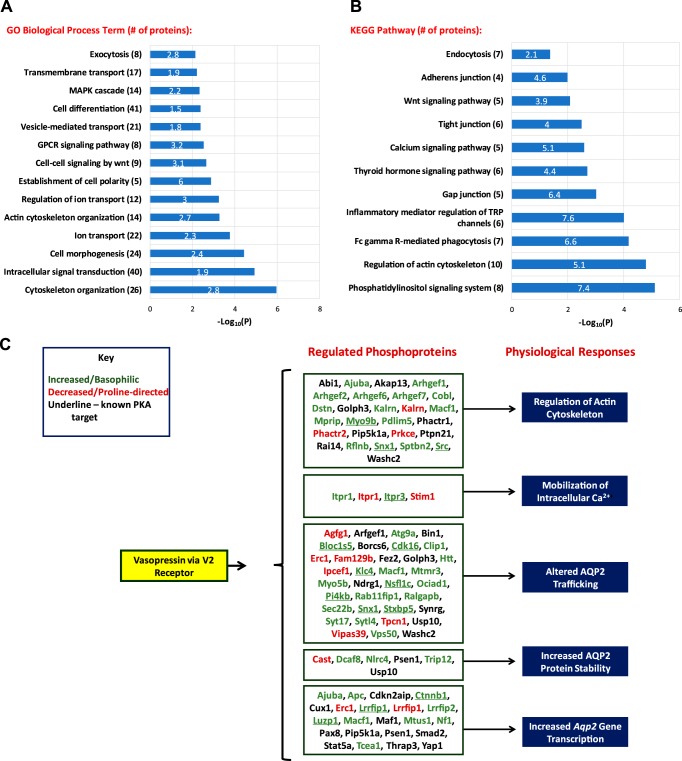

Fig. 2.

Response to vasopressin: general aspects. A: volcano plot showing the distribution of phosphopeptide abundance changes for all 10,738 quantified peptides. The vertical blue dashed lines show bounds for the 95% confidence interval for control-vs.-control observations. The horizontal blue dashed line demarcates the Pjoint value of 0.005. Pjoint is the joint probability between the P value from a paired t-test and the probability that the absolute value of log2(dDAVP/control) differs from zero by the empirical Bayes method (see methods). The vertical axis is truncated (yellow dashed line), and out-of-range values are shown on the border. See methods for the calculation of Pjoint. B: logo showing position-dependent overrepresented amino acids in upregulated monophosphopeptides. n, no. of monophosphopeptides. C: logo showing position-dependent overrepresented amino acids in downregulated monophosphopeptides. dDAVP, 1-desamino-8D-arginine vasopressin.

Consensus sequence motifs were generated for monophosphorylated peptides that were increased (n = 113; Fig. 2B) and were decreased (n = 50; Fig. 2C). Consistent with prior studies (3, 61), phosphopeptides that were increased in abundance in response to dDAVP were dominated by those with basic (positively charged) amino acids arginine (R) and lysine (K) in position −2 and −3 relative to the phosphorylated amino acid (Fig. 2B). This is not only consistent with activation of PKA but also could involve other basophilic protein kinases such as calmodulin kinase 2δ (Camk2d) (8, 78) and p21 (Cdc42/Rac)-activated kinase 1 (Pak1), which recognize a similar (R/K)-(R/K)-X-p(S/T) motif (48) and are expressed in IMCD cells (44). Also consistent with prior studies (3, 61), phosphopeptides that were decreased in abundance in response to dDAVP were dominated by those with a proline (P) in position +1 relative to the phosphorylated amino acid (Fig. 2C). How phosphorylation decreases at so many sites with this motif is discussed later.

Vasopressin-mediated changes in AQP2 phosphorylation confirm prior studies and validate the present experimental model.

Vasopressin triggers changes in phosphorylation of AQP2 at four sites, causing increases in phosphorylation of Ser256 (18, 36), Ser264 (25, 36), and Ser269 (34, 36, 50) and a decrease in phosphorylation of Ser261 (35, 36). All of these sites were detected, and the changes that were observed are consistent with prior observations (Table 1), thereby confirming that the native IMCD cells in suspension used in this study respond to dDAVP in the typical manner.

Table 1.

Phosphopeptides in the water channel AQP2: response to dDAVP

| Gene Symbol | UniProt No. | Residue(s) | Annotation | Peptide | Log2(dDAVP/Vehicle) | Pjoint |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aqp2 | P34080 | S256; S261; S264; S269 | Aquaporin-2 | RR.RQS*VELHS*PQS*LPRGS*K | 1.66 | <e−8 |

| Aqp2 | P34080 | S256; S264; S269 | Aquaporin-2 | RR.RQS*VELHSPQS*LPRGS*K | 1.10 | <e−8 |

| Aqp2 | P34080 | S256; S261; S264 | Aquaporin-2 | RRR.QS*VELHS*PQS*LPR | 1.06 | <e−8 |

| Aqp2 | P34080 | S256; S264 | Aquaporin-2 | RRR.QS*VELHSPQS*LPR | 0.74 | 1.00e−6 |

| Aqp2 | P34080 | S264; S269 | Aquaporin-2 | RRR.QSVELHSPQS*LPRGS*KA | 0.68 | 1.00e−6 |

| Aqp2 | P34080 | S256 | Aquaporin-2 | RRR.QS*VELHSPQ#SLPR | 0.65 | 3.15e−5 |

| Aqp2 | P34080 | S261; S264; S269 | Aquaporin-2 | RRR.QSVELHS*PQS*LPRGS*KA | 0.62 | 2.40e−5 |

| Aqp2 | P34080 | S256; S261 | Aquaporin-2 | RRR.QS*VELHS*PQSLPR | 0.57 | 2.32e−5 |

| Aqp2 | P34080 | S261; S264 | Aquaporin-2 | RRR.QSVELHS*PQ#S*LPR | −0.39 | 0.002 |

| Aqp2 | P34080 | S261 | Aquaporin-2 | RRR.Q#SVELHS*PQSLPR | −1.08 | <e−8 |

AQP2, aquaporin-2; dDAVP, 1-desamino-8D-arginine vasopressin; UniProt, Universal Protein Resource. The peptides shown satisfied dual criteria: absolute value of log2(dDAVP/control) > 0.342 and Pjoint < 0.005. The value of 0.342 defines the 95% confidence interval for control-to-control comparisons. Peptide symbols: *, phosphorylated amino acid; #, deamidation; dot (.), trypsin cleavage site. Pjoint is the joint probability between the P value from a paired t-test and the probability that the absolute value of log2(dDAVP/control) differs from zero by the empirical Bayes method (see methods).

Vasopressin-regulated phosphorylation events link to known effects of vasopressin on collecting duct cells.

We analyzed the phosphoproteomic data to identify Gene Ontology Biological Process terms (Fig. 3A) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways (Fig. 3B) that map to the list of vasopressin-regulated phosphoproteins more frequently than expected with a random selection of IMCD proteins. (Specific proteins in each of these groups are included in Supplemental Data Set S5.) In general, the analysis identified processes that correspond well with the known physiological effects of vasopressin shown in Fig. 1. We used these results and the annotations found in the “Function” field of Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) records to map regulated phosphoproteins to vasopressin-regulated processes (Fig. 3C). Detailed information about the phosphorylation sites corresponding to the phosphoproteins shown in Fig. 3C is provided in Supplemental Data Set S3 and at https://esbl.nhlbi.nih.gov/AVP-Signaling/.

Fig. 3.

Regulated phosphoproteins map to vasopressin-regulated processes. A: enriched Gene Ontology (GO) biological process terms. Values in parentheses indicate the number of proteins, values inside bars indicate the fold enrichment value, and the P value applies to Fisher’s exact test vs. unregulated phosphoproteins. B: enriched Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways. Values in parentheses indicate the number of proteins, values inside bars indicate the fold enrichment value, and the P value applies to Fisher’s exact test vs. unregulated phosphoproteins. C: regulated phosphoproteins mapped to vasopressin-regulated processes from Fig. 1. Green indicates increased basophilic sites. Known PKA targets (Table 2) are underlined. Red indicates decreased proline-directed sites. AQP2, aquaporin-2; Fc gamma R, Fc γ-receptor; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; TRP, transient receptor potential. Regulated phosphoproteins: Abi1, Abl interactor 1; Agfg1, Arf-GAP domain and FG repeat-containing protein-1; Ajuba, LIM domain-containing protein ajuba; Akap13, A-kinase anchor protein-13; Apc, adenomatous polyposis coli protein; Arfgef1, brefeldin A-inhibited guanine nucleotide-exchange protein-1; Arhgef1, 2, 6, and 7, Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor 1, 2, 6, and 7, respectively; Atg9a, autophagy-related protein-9A; Bin1, Myc box-dependent-interacting protein-1; Bloc1s5, protein muted homolog; Borcs6, BLOC-1-related complex subunit 6; Cast, CAZ-associated structural protein; Cdk16, cyclin-dependent kinase 16; Cdkn2aip, CDKN2A-interacting protein; Clip1, CAP-Gly domain-containing linker protein-1; Cobl, protein cordon-bleu; Ctnnb1, catenin-β1; Cux1, homeobox protein cut-like 1; Dcaf8, DDB1- and CUL4-associated factor 8; Dstn, destrin; Erc1, ELKS/Rab6-interacting/CAST family member 1; Fam129b, niban-like protein-1; Fez2, fasciculation and elongation protein ζ-2; Golph3, Golgi phosphoprotein-3; Htt, Huntingtin; Ipcef1, interactor protein for cytohesin exchange factors 1; Itpr1 and Itpr3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 1 and 3, respectively; Kalrn, kalirin; Klc4, kinesin light chain 4; Lrrfip1 and Lrrfip2, leucine-rich repeat flightless-interacting 1 and 2, respectively; Luzp1, leucine zipper protein-1; Macf1, microtubule-actin cross-linking factor 1; Maf1, transcription factor MafB; Mprip, myosin phosphatase Rho-interacting protein; Mtmr3, myotubularin-related protein-3; Mtus1, microtubule-associated tumor suppressor 1 homolog; Myo5b and Myo9b, unconventional myosin-Vb and -IXb, respectively; Ndrg1, protein NDRG1; Nf1, neurofibromin; Nlrc4, NLR family CARD domain-containing protein-4; Nsfl1c, NSFL1 cofactor p47; Ociad1, OCIA domain-containing protein 1; Pax8, paired-box protein Pax-8; Pdlim5, PDZ and LIM domain protein-5; Phactr1 and Phactr2, phosphatase and actin regulator 1 and 2, respectively; Pi4kb, phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase-β; Pip5k1a, phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase type-1α; Prkce, PKC ε-type; Psen1, presenilin-1; Ptpn21, tyrosine-protein phosphatase nonreceptor type 21; Rab11fip1, Rab11 family-interacting protein-1; Rai14, ankycorbin; Ralgapb, Ral GTPase-activating protein subunit-β; Rflnb, refilin-B; Sec22b, vesicle-trafficking protein SEC22b; Smad2, mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 2; Snx1, sorting nexin-1; Sptbn2, spectrin β-chain, nonerythrocytic 2; Stim1, stromal interaction molecule 1; Stxbp5, tomosyn-1; Synrg, synergin-γ; Syt17, synaptotagmin-17; Sytl4, synaptotagmin-like protein-4; Tcea1, transcription elongation factor A protein-1; Thrap3, thyroid hormone receptor-associated protein-3; Tpcn1, two-pore Ca2+ channel protein-1; Trip12, E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase TRIP12; Usp10, ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 10; Vipas39, spermatogenesis-defective protein 39 homolog; Vps50, syndetin; Washc2, WASH complex subunit 2; Yap1, transcriptional coactivator YAP1.

Many of the phosphorylation sites that were increased in abundance in response to vasopressin have been previously shown to be direct PKA target sites (underlined phosphoproteins in Fig. 3C and full list in Table 2) (38). Nevertheless, many other regulated phosphorylation sites do not appear to be direct PKA targets, suggesting that other protein kinases and phosphatases are important in vasopressin signaling, as discussed below.

Table 2.

Known PKA target phosphorylation sites significantly increased in abundance in response to dDAVP in the rat inner medullary collecting duct

| Gene Symbol | UniProt No. | Residue | Annotation | Centralized Sequence | Log2(dDAVP/Control) | Pjoint | Potential Cellular Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mpdz | O55164 | S1065 | Multiple-PDZ domain protein | AMLRRHS*LIGPDI | 0.59 | 2.60e−6 | Maintenance of polarity |

| Myo9b | Q63358 | S1649 | Unconventional myosin-IXb | YTGRRKS*ELGAEP | 0.69 | 7.00e−7 | Regulation of actin cytoskeleton |

| Myo9b | Q63358 | S1327 | Unconventional myosin-IXb | TEERRIS*FSTSDV | 0.54 | 4.67e−5 | Regulation of actin cytoskeleton |

| Arpp19 | Q712U5 | S104 | cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein-19 | LPQRKPS*LVASKL | 0.47 | 1.10e−5 | Regulation of cell proliferation |

| Itpr3 | Q63269 | S934 | Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 3 | VLSRKQS*VFGASS | 1.49 | <e−8 | Regulation of intracellular calcium |

| Itpr3 | Q63269 | S1832 | Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 3 | TKGRVSS*FSMPSS | 0.72 | 5.00e−7 | Regulation of intracellular calcium |

| Bloc1s5 | B2GV52 | S25 | Protein muted homolog | GGKKRDS*LGTAGA | 0.86 | <e−8 | Regulation of membrane trafficking |

| Nsfl1c | O35987 | S176 | NSFL1 cofactor p47 | GERRRHS*GQDVHV | 0.54 | 8.90e−5 | Regulation of membrane trafficking |

| Pi4kb | O08561 | S511 | Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase-β | DIRRRLS*EQLAHT | 0.55 | 4.35e−5 | Regulation of membrane trafficking |

| Snx1 | Q99N27 | S188 | Sorting nexin-1 | AVKRRFS*DFLGLY | 1.02 | <e−8 | Regulation of membrane trafficking |

| Stxbp5 | Q9WU70 | S760 | Tomosyn-1 | KMSRKLS*LPTDLK | 0.85 | <e−8 | Regulation of membrane trafficking |

| Klc3 | Q68G30 | S173 | Kinesin light chain 3 | SPPRRDS*LASLFP | 0.40 | 5.95e−4 | Regulation of microtubule cytoskeleton |

| Klc4 | Q5PQM2 | S566 | Kinesin light chain 4 | DVLRRSS*ELLVRK | 0.58 | 3.96e−5 | Regulation of microtubule cytoskeleton |

| Erbb3 | Q62799 | S980 | Receptor tyrosine kinase erbB-3 | LVIKRAS*GPGTPP | 0.39 | 0.001 | Regulation of protein phosphorylation |

| Mark2 | O08679 | S409 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase MARK2 | PKQRRSS*DQAVPA | 0.33 | 3.44e−4 | Regulation of protein phosphorylation |

| Src | Q9WUD9 | S17 | Tyrosine-protein kinase Src | ASQRRRS*LEPAEN | 0.64 | 8.00e−7 | Regulation of protein phosphorylation |

| Tab2 | Q5U303 | S524 | Transforming growth factor-β-activated MAP3K7-binding protein-2 | SEARKLS*MGSDDA | 0.29 | 0.003 | Regulation of protein phosphorylation |

| Casp6 | O35397 | S62 | Caspase-6 | NPTRRFS*ELGFEV | 0.41 | 7.89e−5 | Regulation of protein stability |

| Optn | Q8R5M4 | S346 | Optineurin | ALERKNS*ATPSEL | 0.41 | 0.004 | Regulation of protein stability |

| Prrc2a | Q6MG48 | S455 | Protein PRRC2A | RQRRKQS*SSEISL | 0.60 | 7.50e−6 | Regulation of RNA processing |

| Ccs | Q9JK72 | S267 | Copper chaperone for SOD | GQGRKDS*AQPPAH | 0.57 | 9.20e−6 | Response to oxidative stress |

| Ctnnb1 | Q9WU82 | S552 | Catenin-β1 | DTQRRTS*MGGTQQ | 0.77 | 1.00e−7 | Transcriptional regulation |

| Lrrfip1 | Q66HF9 | S88 | Leucine-rich repeat flightless-interacting 1 | TSSRRGS*GDTSIS | 0.89 | <e−8 | Transcriptional regulation |

| Luzp1 | Q9ESV1 | S261 | Leucine zipper protein-1 | ESRRKGS*LDYLKQ | 0.91 | <e−8 | Transcriptional regulation |

dDAVP, 1-desamino-8D-arginine vasopressin; UniProt, Universal Protein Resource. PKA target sites were identified by Isobe et al. (38). Centralized sequence symbols: *, phosphorylated amino acid; arginine (R) and lysine (K) moieties in position −2 and −3 relative to the phosphorylated amino acids of the phosphopeptide sequences are underlined. Pjoint is the joint probability between the P value from a paired t-test and the probability that the absolute value of log2(dDAVP/control) differs from zero by the empirical Bayes method (see methods).

Vasopressin alters phosphorylation of several protein kinases.

Many protein kinases are themselves regulated by phosphorylation, forming cascades of kinases that can be activated in series. The protein kinases with phosphorylation sites that underwent changes in phosphooccupancy are shown in Table 3. As indicated in “Net Effect on Activity” in Table 3, 6 of the 23 phosphorylation changes correspond to sites with known consequences on protein kinase activity based on the PhosphoNET database (http://www.phosphonet.ca/). Thus, we can conclude (Fig. 4A) that serine/threonine-protein kinase D1 (Prkd1), cyclin-dependent kinase 16 (Cdk16; also referred to as PCTAIRE kinase 1), cyclin-dependent kinase 18 (Cdk18; also referred to as PCTAIRE kinase 3), and Src likely undergo increases in activity in response to vasopressin and that serine/threonine-protein kinase A-Raf (Araf) and RAF protooncogene serine/threonine-protein kinase (Raf1) likely undergo decreases in activity. Prkd1, Cdk16, and Cdk18 are involved in the regulation of membrane trafficking, whereas Src, Araf, and Raf1 regulate MAPK activities.

Table 3.

Protein kinases with phosphopeptides altered in abundance in response to dDAVP in rat inner medullary collecting duct suspensions

| Gene Symbol | UniProt No. | Residue(s) | Annotation | Peptide | Log2(dDAVP/Control) | Pjoint | Net Effect on Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Araf | P14056 | S255 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase A-Raf | GS*PSPASVSSGR | −0.38 (0.04) | 8.23e−5 | Decrease |

| Cdk16 | Q63686 | S110 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 16 | IS*TEDINK | 1.27 (0.18) | <e−8 | Increase |

| Cdk18 | O35832 | S66 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 18 | FS*MEDLNK | 1.15 (0.19) | <e−8 | Increase |

| Erbb3 | Q62799 | S980 | Receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-3 | RAS*GPGTPPAAEPSVLTTK | 0.39 (0.17) | 1.49e−3 | ? |

| Erbb3 | Q62799 | S980; T984 | Receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-3 | RAS*GPGT*PPAAEPSVLTTK | 0.63 (0.36) | 2.90e−5 | ? |

| Kalrn | P97924 | S1777 | Kalirin | SFDLGS*PKPGDETTPQGDSADEK | −1.10 (0.52) | <e−8 | ? |

| Kalrn | P97924 | S2266 | Kalirin | ISTS*N#GSPGFDYHQPGDK | −0.35 (0.19) | 3.84e−3 | ? |

| Kalrn | P97924 | S375 | Kalirin | QIS*TQLDQ#EWK | 0.43 (0.08) | 1.57e−4 | ? |

| Kalrn | P97924 | S1772 | Kalirin | S*FDLGSPKPGDETTPQGDSADEK | 1.27 (0.19) | <e−8 | ? |

| Map3k7 | P0C8E4 | S439 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 7 | S*IQDLTVTGTEPGQVSSR | 0.38 (0.19) | 2.24e−3 | ? |

| Mark2 | O08679 | T374 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase MARK2 | SSELEGDTIT*LKPRPSADLTNSSAPSPSHK | 0.41 (0.10) | 4.26e−4 | ? |

| Mark2 | O08679 | S380; S390 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase MARK2 | SSELEGDTITLKPRPS*ADLTNSSAPS*PSHK | 0.43 (0.11) | 2.63e−4 | ? |

| Mark2 | O08679 | T374; S390 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase MARK2 | SSELEGDTIT*LKPRPSADLTNSSAPS*PSHK | 0.51 (0.16) | 1.16e−4 | ? |

| Mink1 | F1LP90 | S782 | Misshapen-like kinase 1 | LDSS*PVLSPGNK | −0.65 (0.10) | 1.36e−6 | ? |

| Mink1 | F1LP90 | S782; S786 | Misshapen-like kinase 1 | LDSS*PVLS*PGNK | −0.59 (0.30) | 5.89e−5 | ? |

| Prkce | P09216 | S329 | PKC ε-type | LAAGAES*PQPASGNSPSEDDR | −0.73 (0.19) | 7.43e−7 | ? |

| Prkch | Q64617 | S317 | PKC η-type | TLAGMGLQPGNIS*PTSK | −0.63 (0.95) | 1.11e−4 | ? |

| Prkd1 | Q9WTQ1 | S835 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase D1 | RYS*VDK | 0.37 (0.22) | 3.24e−3 | ? |

| Prkd1 | Q9WTQ1 | S255 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase D1 | SNS*QSYVGRPIQLDK | 0.47 (0.07) | 6.46e−5 | Increase |

| Prpf4b | Q5RKH1 | S62 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase PRP4 homolog | HSS*EEDRDK | 0.47 (0.61) | 2.00e−3 | ? |

| Ptk2 | O35346 | S716 | Focal adhesion kinase 1 | QATVSWDSGGSDEAPPKPS*RPGYPSPR | −1.12 (0.96) | <e−8 | ? |

| Raf1 | P11345 | S259 | RAF protooncogene serine/threonine-protein kinase | STS*TPNVHMVSTTLPVDSR | 0.54 (0.20) | 9.15e−5 | Decrease |

| Src | Q9WUD9 | S17 | Protooncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src | S*LEPAENVHGAGGAFPASQTPSKPASADGHR | 0.64 (0.06) | 7.57e−7 | Increase |

Values are means (SD). dDAVP, 1-desamino-8D-arginine vasopressin; UniProt, Universal Protein Resource. Peptides satisfied dual criteria: absolute value of log2(dDAVP/control) > 0.342 and Pjoint < 0.005. The value of 0.342 defines the 95% confidence interval for control-to-control comparisons. Peptide symbols: *, phosphorylated amino acid; #, deamidated asparagine or glutamine. Pjoint is the joint probability between the P value from a paired t-test and the probability that the absolute value of log2(dDAVP/control) differs from zero by the empirical Bayes method (see methods). Net effect on activity was based on the PhosphoNET database (http://www.phosphonet.ca/).

Fig. 4.

Post-PKA effects of vasopressin on signaling pathways in collecting ducts. A: protein kinases whose phosphorylation changes at sites that alter kinase activity indicated in red. B: proline-directed sites that increase in abundance are putative targets of PKA-regulated cyclin-dependent kinase 16 (Cdk16) and cyclin-dependent kinase 18 (Cdk18). C: PKA-regulated signaling pathways responsible for decreased phosphorylation at sites with proline at position +1. See https://hpcwebapps.cit.nih.gov/ESBL/PKANetwork/MAPK_pathways.html for further information about ERK1 (Mapk3) regulation. Decrease in ERK phosphorylation may be associated with antiproliferative response to vasopressin (see text). AC VI, adenylyl cyclase 6; Gs, G protein subunit Gαs; V2R, vasopressin V2 receptor. Araf, serine/threonine-protein kinase A-Raf; Arpp19, cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein-19; Bin1, Myc box-dependent-interacting protein 1; Carhsp1, Ca2+-regulated heat-stable protein 1; Cux1, homeobox protein cut-like 1; Ensa, α-endosulfine; Hras, GTPase HRas; Mastl, serine/threonine-protein kinase greatwall; Nras, GTPase NRas; Nucks1, nuclear ubiquitous casein and cyclin-dependent kinase substrate 1; Ocln, occludin; Ppp2ca and Ppp2cb, serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2A catalytic subunit α and β, respectively; Ppp2r2d, serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2A 55-kDa regulatory subunit B δ-isoform; Prkd1, serine/threonine-protein kinase D1; Raf1, RAF protooncogene serine/threonine-protein kinase; Rap1a and Rap1b, Ras-related protein Rap-1a and -1b, respectively; Rapgef1, Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor 1; Rras2, Ras-related protein R-Ras2; Slc9a1, Na+/H+ exchanger 1; Wdr44, WD repeat-containing protein-44.

Cdk16 and Cdk18 are activated when phosphorylated by PKA at Ser110 and Ser66, respectively, and are of interest because they are proline-directed kinases that are increased in activity. Although most of the regulated sites with the X-p(S/T)-P-X motif are decreased (Fig. 2C), activation of Cdk16 and Cdk18 leads to the hypothesis that some X-p(S/T)-P-X motif sites may be increased in abundance if they are targets of these two kinases. Indeed, several such sites were identified in proteins with potential roles in vasopressin-regulated processes (Fig. 4B). Among these, of particular interest is Slc9a1 [Na+/H+ exchanger 1 (NHE1)], a critical protein for the maintenance of pH homeostasis and cell volume regulation in cells (7). In the present study, multiple sites in Slc9a1 with the X-p(S/T)-P motif underwent increases in phosphorylation in a region that corresponds to the so-called “COOH-terminal phosphorylated domain” (amino acids 656–815) (60). Increased phosphorylation of this domain increases the pH set point of Slc9a1, thereby alkalinizing the cells (7). Thus, the findings point to a possible role of vasopressin in the regulation of intracellular pH.

Src regulates ERK1 and ERK2 by activating Ras-related protein Rap1 (Fig. 4C), which interferes with Ras-mediated Raf1 activation (20). Src phosphorylation at Ser17 is thought to be mediated directly by PKA (66). Inhibition of Src has been reported to alter AQP2 trafficking in cultured LLC‐PK1 cells through effects on Ser269 phosphorylation (12). Raf1 and Araf, which are inhibited (Fig. 4C), are upstream from ERK1 and ERK2 (Mapk3 and Mapk1, respectively), providing a potential explanation for the widespread decrease in phosphorylation at X-p(S/T)-P motif sites.

Protein phosphatases are involved in the vasopressin response.

Phosphorylation occupancies of proteins are determined by the balance between protein kinases that phosphorylate them and protein phosphatases that dephosphorylate them. Table 4 shows the protein phosphatases and phosphatase regulators that are altered in phosphorylation in response to vasopressin. Only two protein phosphatase catalytic proteins underwent changes in phosphooccupancy, namely, protein phosphatase 1H (Ppm1h) and tyrosine-protein phosphatase nonreceptor type 21 (Ptpn21), although the effects of these phosphorylation events on their catalytic activities are not known.

Table 4.

Protein phosphatases and phosphatase regulators that undergo changes in phosphorylation in response to dDAVP

| Gene Symbol | UniProt No. | Residue(s) | Annotation | Centralized Sequence | Log2(dDAVP/Control) | Pjoint | Upstream Kinase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arpp19 | Q712U5 | S104 | cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein-19 | DLPQRKPS*LVASKLA | 0.47 | 1.10e−5 | PKA |

| Arpp19 | Q712U5 | S62 | cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein-19 | KGQKYFDS*GDYNMAK | −0.46 | 0.002 | Greatwall (Mastl) |

| Ensa | P60841 | S67 | α-Endosulfine | KGQKYFDS*GDYNMAK | −0.46 | 0.002 | Greatwall (Mastl) |

| Mprip | Q9ERE6 | S306 | Myosin phosphatase Rho-interacting protein | STPHSRRS*QVIEKFE | 0.67 | 3.40e−6 | ? |

| Mtm1 | Q6AXQ4 | S23 | Myotubularin† | RESMRKVS*QDGVRQD | 0.65 | 3.48e−5 | PKA? |

| Mtmr3 | Q5PQT2 | S4 | Myotubularin-related protein-3† | MRHS*LECIQAN | 0.37 | 0.002 | ? |

| Ppm1h | Q5M821 | T223 | Protein phosphatase 1H | GAPGSPST*PPTRFFT | −0.66 | 1.00e−6 | CMGC family |

| Ptpn21 | Q62728 | S670; S675; S676; S679 | Tyrosine-protein phosphatase nonreceptor type 21 | TFS*AGSQS*S*VFS*DKVK | 0.65 | 3.00e−7 | ? |

dDAVP, 1-desamino-8D-arginine vasopressin; UniProt, Universal Protein Resource; CMGC family, kinase family named after its best-known members, namely, cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), MAPKs, GSK3, and CDK-like kinases (CLKs). Peptides satisfied dual criteria: absolute value of log2(dDAVP/control) > 0.342 and Pjoint < 0.005. The value of 0.342 defines the 95% confidence interval for control-to-control comparisons. Centralized sequence symbols: *, phosphorylated amino acid; #, deamidated asparagine or glutamine. Pjoint is the joint probability between the P value from a paired t-test and the probability that the absolute value of log2(dDAVP/control) differs from zero by the empirical Bayes method (see methods).

Also functions as phospholipid phosphatase.

Of greater interest were two paralogous phosphatase regulators that underwent changes in phosphorylation in response to vasopressin, namely, α-endosulfine (Ensa) and cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein-19 (Arpp19; Fig. 4C). These are phosphatase inhibitor proteins that block the activity of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A; gene symbols Ppp2ca and Ppp2cb). In the nucleus, PP2A dephosphorylates Cdk1, and, therefore, Ensa and Arpp19 are critical to cell cycle regulation and cell proliferation (26, 49). Arpp19 underwent an increase in phosphorylation at a known PKA target site (Ser104), which decreases its phosphatase inhibitory activity (23, 24), i.e., increases PP2A activity. Arpp19 and its target, PP2A, are present not only in the nucleus but also in the cytoplasm (78, 79), where Arpp19 can also be phosphorylated by PKA (82). Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino acids in Cell culture (SILAC)-based phosphoproteomic study (4) in yeast has demonstrated that PP2A is highly selective for sites phosphorylated by proline-directed kinases, i.e., those with an X-p(S/T)-P motif. This finding provides an alternative hypothesis for how PKA could selectively decrease phosphorylation at many X-p(S/T)-P sites (including Ser261 of AQP2), namely, by increasing PP2A activity via Arpp19 phosphorylation (Fig. 4C). Cheung et al. (13) have proposed that another phosphatase, namely, PP2C, could also fulfill a related role.

Arpp19 and Ensa also underwent decreases in phosphorylation of sites (Ser62 and Ser67, respectively) uniquely phosphorylated by the basophilic kinase Greatwall (gene symbol Mastl), a key cell cycle regulator (26, 49). This suggests that vasopressin decreases Greatwall activity, although the mechanism is unclear. With decreased phosphorylation by greatwall, Arpp19 and Ensa inhibition of PP2A is reduced, which ultimately decreases cyclin-B1-CDK1 activity. The phosphorylation changes in Arpp19 and Ensa are therefore consistent with the known antiproliferative action of vasopressin seen in the absence of proproliferative polycystin-1 and polycystin-2 mutations (77).

Vasopressin and the phosphoinositide signaling pathway.

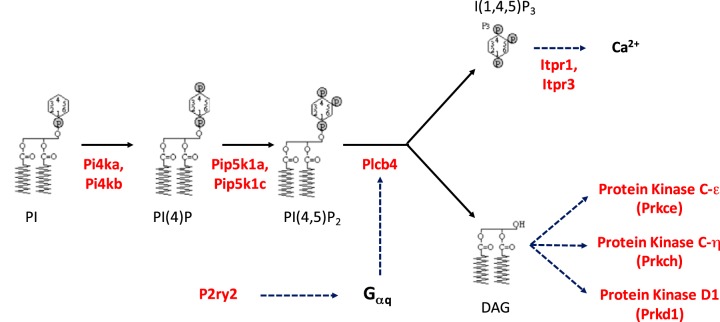

The KEGG pathway analysis described above (Fig. 3B) revealed an unexpected pathway, namely, the “phosphatidylinositol signaling system.” Table 5 shows the phosphorylation changes that map to this pathway. In general, sites that increased in response to dDAVP had basic amino acids in position −3, consistent with phosphorylation by PKA or another basophilic protein kinase. The phosphoproteins with altered phosphorylation encompass the breadth of the phosphatidylinositol signaling pathway (Fig. 5), including the enzymes that perform phosphorylation of inositol positions 4 and 5 in phosphatidylinositol, phospholipase-Cβ (which cleaves phosphatidylinositol 4,5-phosphate to generate inositol trisphosphate and diacylglycerol), the inositol trisphosphate receptors that release Ca2+ from endoplasmic reticulum stores, and three protein kinases that are regulated by diacylglycerol (PKC-ε, PKC-η, and PKD1). In collecting duct cells, the phosphoinositide signaling pathway is normally activated as a result of G protein subunit Gαq-mediated signaling from two receptors, the purinergic P2Y2 receptor (P2ry2) (41) and the PGE2 receptor EP1 (Ptger1) (29). Ligand binding to these two receptors results in decreases in vasopressin-stimulated water permeability (32, 40). Here, the P2Y2 receptor underwent a decrease in phosphorylation at proline-directed sites in the COOH-terminal tail (DAKPATEPT*PS*PQAR) in response to dDAVP. No phosphorylation changes were seen for Ptger1. Diacylglycerol is known to activate PKC-ε and PKC-η, both of which also underwent decreases in phosphorylation at proline-directed sites in response to dDAVP. Diacylglycerol also activates protein kinase D1 (Prkd1), which underwent a significant increase in phosphorylation at a site (Ser255) that is known to increase its enzymatic activity (Table 3). As discussed by Isobe et al. (38), PKA-mediated phosphorylation of the inositol trisphosphate receptors Itpr1 and Itpr3 provides a likely explanation for the fact that V2 receptor occupation evokes Ca2+ mobilization in the collecting duct (69), which occurs in the form of irregular Ca2+ spikes (81). Furthermore, these findings provide a potential explanation for the Ca2+/calmodulin dependence of the water permeability response to vasopressin in the renal collecting duct (14, 16). Overall, these data point to a previously unrecognized interaction between vasopressin/PKA-mediated signaling and phospholipase C-mediated signaling in the renal collecting duct.

Table 5.

Phosphopeptides that change in abundance in response to dDAVP and correspond to proteins in KEGG “phosphatidylinositol signaling system”

| Gene Symbol | Site(s) | Annotation | Phosphopeptide | Log2(dDAVP/Vehicle) | Pjoint | Target Motif |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Itpr1 | S1756 | Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 1 | RES*LTSFGN#GPLSPGGPSKPGGGGGGPGSGSTSR | 1.858 (0.038) | 3.16e−16 | Basophilic |

| Itpr3 | S934 | Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 3 | KQS*VFGASSLPTGVGVPEQLDR | 1.489 (0.330) | 3.16e−16 | Basophilic |

| Pi4kb | S511; T517 | Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase-β | RLS*EQLAHT*PTAFK | 0.822 (0.162) | 3.22e−8 | Basophilic |

| Pi4ka | S250; S251 | Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase-α | KTS*S*VSSISQVSPER | 0.764 (0.051) | 1.80e−8 | Basophilic and S/T rich |

| Itpr3 | S1832 | Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 3 | VSS*FSMPSSSR | 0.719 (0.146) | 5.25e−7 | Basophilic |

| Itpr1 | S1756; S1766 | Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 1 | RES*LTSFGN#GPLS*PGGPSKPGGGGGGPGSGSTSR | 0.700 (0.227) | 2.09e−6 | Basophilic and proline directed |

| Pip5k1a | S55 | Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase type-1α | SVDS*SGETTYK | 0.643 (0.177) | 5.77e−6 | S/T rich |

| Pi4ka | S251 | Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase-α | KTSS*VSSISQVSPER | 0.586 (0.088) | 6.05e−6 | Basophilic and S/T rich |

| Itpr1 | S1589 | Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 1 | DS*VLAASR | 0.553 (0.277) | 1.17e−4 | Basophilic |

| Pi4kb | S511 | Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase-β | LS*EQLAHTPTAFK | 0.547 (0.152) | 4.35e−5 | Basophilic |

| Pi4ka | S250; S251; S254 | Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase-α | KTS*S*VSS*ISQVSPER | 0.525 (0.090) | 2.63e−5 | Basophilic and S/T rich |

| Mtmr3 | S4 | Phosphatidylinositol-3,5-bisphosphate 3-phosphatase | HS*LEC^IQANQIFPR | 0.369 (0.151) | 1.80e−3 | Basophilic |

| Pip5k1c | S540 | Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase type-1γ | SPS*DTSEQPR | −0.383 (0.123) | 9.25e−4 | Acidophilic |

| Plcb4 | T886; S891 | 1-Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate phosphodiesterase-β4 | ANVT*PQSSS*ELRPTTTAALGSGQEAK | −0.419 (0.228) | 1.43e−3 | Proline directed and S/T rich |

| Itpr1 | S1766 | Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 1 | ESLTSFGN#GPLS*PGGPSKPGGGGGGPGSGSTSR | −0.428 (0.196) | 8.99e−4 | Proline directed |

| Plcb4 | S891 | 1-Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate phosphodiesterase-β4 | ANVTPQSSS*ELRPTTTAALGSGQEAK | −0.512 (0.211) | 1.79e−4 | S/T rich |

Values are means (SD). dDAVP, 1-desamino-8D-arginine vasopressin; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Peptides satisfied dual criteria: absolute value of log2(dDAVP/control) > 0.342 and Pjoint < 0.005. The value of 0.342 defines the 95% confidence interval for control-to-control comparisons. Phosphopeptide symbols: *, phosphorylated amino acid; #, deamidated asparagine or glutamine; ^, carbamidomethyl. Pjoint is the joint probability between the P value from a paired t-test and the probability that the absolute value of log2(dDAVP/control) differs from zero by the empirical Bayes method (see methods).

Fig. 5.

Phosphoinositide signaling pathway in renal collecting duct cells. Proteins in red undergo changes in phosphorylation in response to dDAVP (see Table 5 for specific regulated phosphopeptides). Phosphatidylinositol (PI) 4-kinase-α and -β (Pi4ka and Pi4kb, respectively), phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate [PI(4)P] 5-kinase type-1α and -1γ (Pip5k1a and Pip5k1c, respectively), and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2] phosphodiesterase-β4 (Plcb4) are shown. Sites in inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate [I(1,4,5)P3] receptor type 1 and 3 (Itpr1 and Itpr3, respectively) likely increase Ca2+ release (38). The upregulated site in serine/threonine-protein kinase D1 (Prkd1) increases its activity. DAG, diacylglycerol; Gαq, G protein subunit Gαq; P2ry2, purinergic P2Y2 receptor; Prkce and Prkch, PKC ε- and C η-type, respectively.

PKA-dependent vasopressin signaling occurs predominantly at membrane surfaces.

All of the elements of the phosphoinositide pathway (Fig. 5) are either integral membrane proteins or peripheral membrane proteins. This observation led to the hypothesis that PKA-dependent vasopressin signaling occurs predominantly at membrane surfaces, similar to PKC (33, 57). To test this, we analyzed the proteins containing phosphorylation sites that increased in occupancy to determine the fraction that are membrane proteins (proteins with Gene Ontology cellular component terms that contain the strings “membrane,” “vesicle,” or “endosome”). Of the 118 proteins with increased phosphorylation, 84 proteins were classified as membrane proteins (71%). This can be compared with a random sampling of 118 proteins without phosphorylation changes yielding 59 membrane proteins (50%, χ2 P = 0.0022; Supplemental Data Set S6). Thus, phosphorylation-dependent vasopressin signaling appears to be selectively targeted to the plasma membrane or intracellular membranes, likely in part due to selective association of PKA with the cytoplasmic surface of membranes.

Membrane association may be attributable in part to scaffold proteins of the A-kinase anchor protein (AKAP) family (5) or to other protein-protein interactions. In the present study, we identified six AKAP proteins in rat IMCD cells, namely, Akap1, Akap2, Akap8, Akap11, Akap12, and Akap13 (Supplemental Data Set S4). Another type of protein interaction occurs between proteins with PDZ domains and COOH-terminal PDZ ligands, which can localize PKA with its substrates (74). Multiple PDZ domain-containing proteins can be identified in the proteome list including several that undergo significant changes in phosphorylation in response to vasopressin [connector enhancer of kinase suppressor of Ras 3 (Cnksr3), PDZ domain-containing protein GIPC1 (Gipc1), multiple-PDZ domain protein (Mpdz), and PDZ and LIM domain protein-5 (Pdlim5; Supplemental Data Set S4)]. Furthermore, PKA catalytic-α (but not -β) contains a class I COOH-terminal PDZ ligand motif [-(S/T)-X-ϕ, where ϕ means any hydrophobic amino acid]. Accordingly, we asked whether proteins with class I COOH-terminal 3-amino acid motifs are more likely to show increases in phosphorylation in response to vasopressin than proteins without the motif. χ2-analysis showed that this was true (χ2 = 5.108, P = 0.023). These vasopressin-regulated proteins are provided in Supplemental Data Set S7. All of the increased phosphorylation sites in monophosphopeptides were basic in character with R or K in position −3 relative to the phosphorylated S/T, consistent with phosphorylation by PKA or other basophilic kinases.

AQP2-interacting proteins show increases in phosphorylation in response to vasopressin.

Proteins that form complexes with AQP2 are likely to be phosphorylated by the same protein kinases as AQP2. Consequently, we asked what proteins identified as AQP2-binding proteins in a previous mass spectrometry-based study (15) have sites that showed increases in phosphorylation. These proteins are shown in Table 6, with the protein kinases that phosphorylate them. Among the AQP2-binding proteins with upregulated phosphorylation sites is leucyl-cystinyl aminopeptidase (Lnpep), a peptidase more commonly known as “vasopressinase” in the clinical water-balance disorder literature. This protein is highly expressed in the placenta and is sporadically associated with gestational diabetes insipidus (43). Like AQP2, vasopressinase has been previously reported to translocate to the cell surface in response to vasopressin in renal epithelial cells (46), although its physiological role in the collecting duct is unknown. In response to vasopressin, it undergoes an increase in phosphorylation at Ser91, a site previously demonstrated to be phosphorylated by PKC-ζ (63), a component of the apical polarity complex in epithelial cells (71). Another AQP2-interacting protein that undergoes an increase in phosphorylation is protein NDRG1 (Ndrg1), which is thought to be involved in endosomal trafficking (39, 59). The phosphorylation sites are found in a decapeptide repeat region in the COOH-terminal portion of the protein and have been attributed to two protein kinases, glycogen synthase kinase-3β (Gsk3b) and serine/threonine protein kinase serum/glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 (Sgk1) (51). The other AQP2-interacting proteins shown in Table 6 demonstrated increases in phosphorylation at sites for which no protein kinase has been identified.

Table 6.

AQP2-binding proteins that contain phosphorylation sites increased in abundance in response to dDAVP

| Gene Symbol | UniProt No. | Residue(s) | Annotation | Centralized Sequence | Log2(dDAVP/Control) | Pjoint | Upstream Kinase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eif3a | Q1JU68 | T574 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit A | AR.RQT*IEER | 0.52 | 2.82e−5 | ? |

| Fam129b | B4F7E8 | S633; S645; S648 | Niban-like protein-1 | QVVSVVQDEES*GLPFEAGSEPPS*PAS*PDNVTELR | 1.32 | <e−8 | ? |

| Isyna1 | Q6AYK3 | S532 | Inositol-3-phosphate synthase 1 | CK.KES*TPATNGC^TGDANGHTQAPTPELSTA | 0.40 | 7.04e−4 | ? |

| Lnpep | P97629 | S91 | Leucyl-cystinyl aminopeptidase (vasopressinase) | GLR.NS*ATGYR | 0.43 | 0.001 | ? |

| Ndrg1 | Q6JE36 | S362; S364 | Protein NDRG1 | EGSR.S*RS*HTSEDAR | 1.19 | <e−8 | Gsk3b |

| Ndrg1 | Q6JE36 | T346; S347 | Protein NDRG1 | RSR.SHT*S*EGPR | 0.49 | 0.002 | Sgk1 |

| Slc14a2 | Q62668 | S84 | Urea transporter 2 | RSKR.RES*ELPRRA | 2.49 | <e−8 | |

| Slc14a2 | Q62668 | S918 | Urea transporter 2 | NR.RAS*MITK | 1.21 | <e−8 | ? |

| Slc14a2 | Q62668 | S486 | Urea transporter 2 | PRRK.S*VFHIEWSSIR | 0.49 | 9.02e−5 | PKA |

| Sptbn2 | Q9QWN8 | S2254 | Spectrin β-chain, nonerythrocytic 2 | LRR.GS*LGFYK | 2.13 | <e−8 | ? |

| Aqp2 | P34080 | S256; S261; S264; S269 | Aquaporin-2 | RR.RQS*VELHS*PQS*LPRGS*K | 1.66 | <e−8 | ? |

| Aqp2 | P34080 | S256; S264; S269 | Aquaporin-2 | RR.RQS*VELHSPQS*LPRGS*K | 1.10 | <e−8 | ? |

| Aqp2 | P34080 | S256; S261; S264 | Aquaporin-2 | RRR.QS*VELHS*PQS*LPR | 1.06 | <e−8 | ? |

| Aqp2 | P34080 | S256; S264 | Aquaporin-2 | RRR.QS*VELHSPQS*LPR | 0.74 | 1.00e−6 | ? |

| Aqp2 | P34080 | S264; S269 | Aquaporin-2 | RRR.QSVELHSPQS*LPRGS*KA | 0.68 | 1.00e−6 | ? |

| Aqp2 | P34080 | S256 | Aquaporin-2 | RRR.QS*VELHSPQ#SLPR | 0.65 | 3.15e−5 | ? |

| Aqp2 | P34080 | S261; S264; S269 | Aquaporin-2 | RRR.QSVELHS*PQS*LPRGS*KA | 0.62 | 2.40e−5 | ? |

| Aqp2 | P34080 | S256; S261 | Aquaporin-2 | RRR.QS*VELHS*PQSLPR | 0.57 | 2.32e−5 | ? |

AQP2, aquaporin-2; dDAVP, 1-desamino-8D-arginine vasopressin; UniProt, Universal Protein Resource. AQP2 peptides are included for comparison. Peptides satisfied dual criteria: absolute value of log2(dDAVP/control) > 0.342 and Pjoint < 0.005. The value of 0.342 defines the 95% confidence interval for control-to-control comparisons. Centralized sequence symbols: *, phosphorylated amino acid; #, deamidation; dot (.), protease cleavage site; ^, carbamidomethyl. Pjoint is the joint probability between the P value from a paired t-test and the probability that the absolute value of log2(dDAVP/control) differs from zero by the empirical Bayes method (see methods).

Vasopressin-mediated changes in phosphorylation of transporter proteins other than AQP2.

Although the main focus of this article is on the regulation of AQP2, vasopressin may also regulate other transport proteins. Table 7 shows regulated sites in transporter proteins other than AQP2 and Slc14a2. Of particular interest is a double phosphopeptide in epithelial Na+ channel subunit-β (β-ENaC; Ser631 and Ser633) that was markedly decreased in abundance by dDAVP. Ser631 was identified as a target for the acidophilic kinase casein kinase 2 (CK2) by Shi et al. (67) and Bachhuber et al. (2), who showed that phosphorylation at Ser631 is associated with channel activation. Also of interest are vasopressin-upregulated phosphopeptides in two subunits of the volume-regulated anion channel [VRAC (73); Lrrc8a and Lrrc8d]. This channel is responsible for “volume-regulatory decrease,” a response to osmotic cell swelling that restores cell volume by exporting solute (76), a function vital to survival of IMCD cells in vivo. Another novel finding was that three phosphopeptides in the COOH-terminal tail of AQP4 showed significant increases in response to dDAVP. A prior study (10) found PKA-mediated phosphorylation of AQP4 in gastric parietal cells, although the specific phosphorylation site was not identified. Mutations of Ser276, Ser285, or Ser315 to alanine did not affect water channel gating when expressed in Xenopus oocytes (1), although an indirect effect of phosphorylation changes on AQP4-mediated water transport, e.g., via membrane trafficking, cannot be ruled out.

Table 7.

Phosphopeptides in membrane transport proteins aside from Aqp2 that were significantly altered in abundance by dDAVP

| Gene Symbol | UniProt No. | Residue(s) | Annotation | Peptide | Log2(dDAVP/Vehicle) | Pjoint |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aqp4 | P47863 | S285; T289 | Aquaporin-4 | GSYMEVEDNRS*QVET*EDLILKPGVVHVIDIDR | 0.59 | 3.43e−5 |

| Aqp4 | P47863 | S276; T289 | Aquaporin-4 | GS*YMEVEDN#RSQVET*EDLILKPGVVHVIDIDRGDEK | 0.38 | 0.003 |

| Aqp4 | P47863 | S315 | Aquaporin-4 | GKDS*SGEVLSSV | 0.37 | 0.002 |

| Lrrc8a | Q4V8I7 | S199 | Volume-regulated anion channel subunit LRRC8A | KSS*TVSEDVEATVPMLQR | 0.71 | 6.00e−7 |

| Lrrc8d | Q5U308 | S262 | Volume-regulated anion channel subunit LRRC8D | FS*AEKPVIEVPSMTILDK | 0.36 | 6.18e−4 |

| Scnn1b | P37090 | S631; S633 | Amiloride-sensitive sodium channel subunit-β | LQPLDTM@ES*DS*EVEAI | −0.81 | 1.30e−6 |

| Slc12a9 | Q66HR0 | S659 | Solute carrier family 12 member 9 | EGGS*PALSTLFPPPR | −0.51 | 1.36e−4 |

| Slc16a10 | Q91Y77 | S37; S43 | Monocarboxylate transporter 10 | ETNEAQ#PPGPAPSDDAPLPVPGPS*DVSDGS*VEKVEVELTR | 0.38 | 0.002 |

| Slc38a1 | Q9JM15 | S52; S56 | Na+-coupled neutral amino acid transporter 1 | S*LTNS*HLEK | 0.52 | 1.49e−4 |

| Slc44a3 | Q6AY92 | S590 | Choline transporter-like protein-3 | NS*LPNEEGTELRPIVR | 1.14 | <e−8 |

| Slc9a1 | P26431 | S727; S730; S733 | Na+/H+ exchanger 1 | ADLPVITIDPAS*PQS*PES*VDLVNEELK | 0.68 | 1.33e−5 |

| Slc9a1 | P26431 | S776; T784 | Na+/H+ exchanger 1 | SKEPSS*PGTDDVFT*PGPSDSPGSQR | 0.62 | 2.87e−5 |

| Slc9a1 | P26431 | T722; S733 | Na+/H+ exchanger 1 | ADLPVIT*IDPAS?PQSPES*VDLVNEELK | 0.40 | 1.05e−4 |

| Slc9a1 | P26431 | S776; T784; S790 | Na+/H+ exchanger 1 | SKEPSS*PGTDDVFT*PGPSDS*PGSQR | 0.38 | 0.004 |

| Slc9a1 | P26431 | T722 | Na+/H+ exchanger 1 | ADLPVIT*IDPAS?PQS?PESVDLVNEELK | 0.38 | 0.007 |

| Slc9a1 | P26431 | S730; S733 | Na+/H+ exchanger 1 | ADLPVITIDPAS?PQS*PES*VDLVNEELK | 0.36 | 9.56e−4 |

| Slco4a1 | Q99N01 | S67 | Organic anion transporter family member 4A1 | RSS*QAAC^EVQYLSSGPQSTLC^GWQSFTPK | 0.85 | <e−8 |

| Slco4a1 | Q99N01 | S39; S42 | Organic anion transporter family member 4A1 | AS*PAS*LR | −0.59 | 5.74e−5 |

| Tpcn1 | Q9WTN5 | T806 | Two-pore Ca2+ channel protein-1 | GSAPSPAAQQT*PGSR | −0.37 | 8.50e−4 |

| Tpcn1 | Q9WTN5 | S800; T806 | Two-pore Ca2+ channel protein-1 | GSAPS*PAAQQT*PGSR | −0.74 | 5.00e−4 |

| Trpm8 | Q8R455 | T588 | Transient receptor potential cation channel M8 | GC^T*LAALGASK | 0.67 | 1.40e−6 |

AQP, aquaporin; dDAVP, 1-desamino-8D-arginine vasopressin; UniProt, Universal Protein Resource. Peptides satisfied dual criteria: absolute value of log2(dDAVP/control) > 0.342 and Pjoint < 0.005. The value of 0.342 defines the 95% confidence interval for control-to-control comparisons. Peptide symbols: *, phosphorylated amino acid; #, deamidation; ^, carbamidomethyl; ?, phosphorylation site (ambiguous site assignment); @, oxidation. Pjoint is the joint probability between the P value from a paired t-test and the probability that the absolute value of log2(dDAVP/control) differs from zero by the empirical Bayes method (see methods).

DISCUSSION

In this work, we have exploited recent advances in the overall sensitivity and precision of protein mass spectrometry to perform near-comprehensive quantitative phosphoproteomic profiling of the vasopressin response. A strength of this work is that it was done in freshly isolated collecting duct cells obtained from rat renal inner medullas. Thus, the cells are likely to exhibit a high degree of phenotypic fidelity to functioning cells in the kidney. Overall, the present study considerably expands fundamental knowledge about cell signaling responses to vasopressin in the collecting duct and provides a set of online resources for future studies of vasopressin signaling, water balance disorders, and polycystic kidney disease. The associated web resources (https://esbl.nhlbi.nih.gov/IMCD-Phos/ and https://esbl.nhlbi.nih.gov/AVP-Signaling/) are designed to allow facile browsing and/or downloading of the data.

The present study produced a multifold increase in the number of known vasopressin-regulated phosphorylation sites in the renal collecting duct. For example, a phosphoproteomics study of the vasopressin response in the renal IMCD by Bansal et al. (3) found only 29 vasopressin-regulated phosphopeptides among the 530 phosphopeptides quantified, whereas the present study found 219 vasopressin-regulated phosphorylation sites among the 10,738 distinct phosphopeptides quantified. As a consequence, we are now able to identify multiple phosphoproteins that relate directly to the vasopressin-regulated cellular processes known from prior work (Fig. 3C). Thus, we have identified several elements of vasopressin signaling that were heretofore unknown: identification of two cAMP-regulated phosphatase inhibitors (Ensa and Arpp19) that are regulated by vasopressin, identification of six protein kinases (Prkd1, Cdk16, Cdk18, Src, Araf, and Raf1; Table 3) whose activities are regulated by vasopressin, identification of several elements of the phosphoinositide signaling pathway that undergo differential phosphorylation in response to vasopressin, recognition of PDZ interactions as a potential mechanism of kinase targeting to their substrates, recognition of vasopressinase as a vasopressin-regulated protein in the IMCD, and identification of multiple vasopressin-regulated phosphorylation sites in transporter and channel proteins other than AQP2.

Although this work was performed in renal collecting duct cells, the findings may be relevant to other cell types that signal through Gαs-adenylyl cyclase-linked G protein-coupled receptors. Prior reports have provided phosphoproteomic data in Jurkat T cells [PGE2 EP2/EP4 receptor (6, 27)], mouse MA10 Leydig cells [luteinizing hormone receptor (28)], Henle’s loop cells in kidney [vasopressin, glucagon, parathyroid hormone, and calcitonin receptors (30)], renal proximal tubule cells [parathyroid hormone receptor (52)], striatal neurons [dopamine D1 receptor (53)], synovial fibroblasts [PGE2 EP2 receptor (53)], primary cultures of cortical neurons [pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide type 1 receptor (21)], MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast cells [type 1 parathyroid hormone receptor (75)], and mouse cardiac myocytes [β-adrenergic receptor (19)]. In addition to curating knowledge specifically about vasopressin signaling, a future bioinformatics goal is to cocurate regulated phosphorylation sites among these studies of other cell types and other receptors to identify common elements of cAMP-mediated signaling responses.

NOTE ADDED IN PROOF

Supplemental Data for this article is available at https://hpcwebapps.cit.nih.gov/ESBL/Database/IMCDPhos-Supplemental/.

GRANTS

The work was funded by the Division of Intramural Research, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI; Projects ZIA-HL-001285 and ZIA-HL-006129, to M. A. Knepper). V. Deshpande was a member of the Biomedical Engineering Student Internship Program at the National Institutes of Health, summer 2017. Protein mass spectrometry was done in the NHLBI Proteomics Core Facility (Marjan Gucek, Director).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

V.D., C.-L.C., and M.A.K. conceived and designed research; V.D., C.-L.C., and M.A.K. performed experiments; V.D., A.K., V.R., C.-L.C., and M.A.K. analyzed data; V.D., V.R., A.D., C.-L.C., and M.A.K. interpreted results of experiments; V.D., A.K., C.-L.C., and M.A.K. prepared figures; C.-L.C. and M.A.K. drafted manuscript; V.D., A.K., V.R., C.-L.C., and M.A.K. edited and revised manuscript; V.D., A.K., V.R., A.D., C.-L.C., and M.A.K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Guangwei Wang for expert advice concerning mass spectrometry.

Some of the results were presented at the Experimental Biology 2018 Meeting (April 21–25, 2018, San Diego, CA).

REFERENCES

- 1.Assentoft M, Larsen BR, Olesen ET, Fenton RA, MacAulay N. AQP4 plasma membrane trafficking or channel gating is not significantly modulated by phosphorylation at COOH-terminal serine residues. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 307: C957–C965, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00182.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachhuber T, Almaça J, Aldehni F, Mehta A, Amaral MD, Schreiber R, Kunzelmann K. Regulation of the epithelial Na+ channel by the protein kinase CK2. J Biol Chem 283: 13225–13232, 2008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704532200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bansal AD, Hoffert JD, Pisitkun T, Hwang S, Chou CL, Boja ES, Wang G, Knepper MA. Phosphoproteomic profiling reveals vasopressin-regulated phosphorylation sites in collecting duct. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 303–315, 2010. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009070728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baro B, Játiva S, Calabria I, Vinaixa J, Bech-Serra JJ, de LaTorre C, Rodrigues J, Hernáez ML, Gil C, Barceló-Batllori S, Larsen MR, Queralt E. SILAC-based phosphoproteomics reveals new PP2A-Cdc55-regulated processes in budding yeast. Gigascience 7: giy047, 2018. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giy047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beene DL, Scott JD. A-kinase anchoring proteins take shape. Curr Opin Cell Biol 19: 192–198, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beltejar MG, Lau HT, Golkowski MG, Ong SE, Beavo JA. Analyses of PDE-regulated phosphoproteomes reveal unique and specific cAMP-signaling modules in T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114: E6240–E6249, 2017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1703939114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bianchini L, Pouysségur J. Regulation of the Na+/H+ exchanger isoform NHE1: role of phosphorylation. Kidney Int 49: 1038–1041, 1996. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradford D, Raghuram V, Wilson JL, Chou CL, Hoffert JD, Knepper MA, Pisitkun T. Use of LC-MS/MS and Bayes’ theorem to identify protein kinases that phosphorylate aquaporin-2 at Ser256. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 307: C123–C139, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00377.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown D. The ins and outs of aquaporin-2 trafficking. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F893–F901, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00387.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carmosino M, Procino G, Tamma G, Mannucci R, Svelto M, Valenti G. Trafficking and phosphorylation dynamics of AQP4 in histamine-treated human gastric cells. Biol Cell 99: 25–36, 2007. doi: 10.1042/BC20060068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chabardès D, Firsov D, Aarab L, Clabecq A, Bellanger AC, Siaume-Perez S, Elalouf JM. Localization of mRNAs encoding Ca2+-inhibitable adenylyl cyclases along the renal tubule. Functional consequences for regulation of the cAMP content. J Biol Chem 271: 19264–19271, 1996. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheung PW, Terlouw A, Janssen SA, Brown D, Bouley R. Inhibition of non-receptor tyrosine kinase Src induces phosphoserine 256-independent aquaporin-2 membrane accumulation. J Physiol 597: 1627–1642, 2019. doi: 10.1113/JP277024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheung PW, Ueberdiek L, Day J, Bouley R, Brown D. Protein phosphatase 2C is responsible for VP-induced dephosphorylation of AQP2 serine 261. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 313: F404–F413, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00004.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chou CL, Christensen BM, Frische S, Vorum H, Desai RA, Hoffert JD, de Lanerolle P, Nielsen S, Knepper MA. Non-muscle myosin II and myosin light chain kinase are downstream targets for vasopressin signaling in the renal collecting duct. J Biol Chem 279: 49026–49035, 2004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408565200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chou CL, Hwang G, Hageman DJ, Han L, Agrawal P, Pisitkun T, Knepper MA. Identification of UT-A1- and AQP2-interacting proteins in rat inner medullary collecting duct. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 314: C99–C117, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00082.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chou CL, Yip KP, Michea L, Kador K, Ferraris JD, Wade JB, Knepper MA. Regulation of aquaporin-2 trafficking by vasopressin in the renal collecting duct. Roles of ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ stores and calmodulin. J Biol Chem 275: 36839–36846, 2000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christensen BM, Marples D, Jensen UB, Frokiaer J, Sheikh-Hamad D, Knepper M, Nielsen S. Acute effects of vasopressin V2-receptor antagonist on kidney AQP2 expression and subcellular distribution. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 275: F285–F297, 1998. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.275.2.F285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christensen BM, Zelenina M, Aperia A, Nielsen S. Localization and regulation of PKA-phosphorylated AQP2 in response to V2-receptor agonist/antagonist treatment. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 278: F29–F42, 2000. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.1.F29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu G, Egnaczyk GF, Zhao W, Jo SH, Fan GC, Maggio JE, Xiao RP, Kranias EG. Phosphoproteome analysis of cardiomyocytes subjected to β-adrenergic stimulation: identification and characterization of a cardiac heat shock protein p20. Circ Res 94: 184–193, 2004. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000107198.90218.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cook SJ, Rubinfeld B, Albert I, McCormick F. RapV12 antagonizes Ras-dependent activation of ERK1 and ERK2 by LPA and EGF in Rat-1 fibroblasts. EMBO J 12: 3475–3485, 1993. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06022.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delcourt N, Thouvenot E, Chanrion B, Galéotti N, Jouin P, Bockaert J, Marin P. PACAP type I receptor transactivation is essential for IGF-1 receptor signalling and antiapoptotic activity in neurons. EMBO J 26: 1542–1551, 2007. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Douglass J, Gunaratne R, Bradford D, Saeed F, Hoffert JD, Steinbach PJ, Knepper MA, Pisitkun T. Identifying protein kinase target preferences using mass spectrometry. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 303: C715–C727, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00166.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dupré A, Daldello EM, Nairn AC, Jessus C, Haccard O. Phosphorylation of ARPP19 by protein kinase A prevents meiosis resumption in Xenopus oocytes. Nat Commun 5: 3318, 2014. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dupré AI, Haccard O, Jessus C. The greatwall kinase is dominant over PKA in controlling the antagonistic function of ARPP19 in Xenopus oocytes. Cell Cycle 16: 1440–1452, 2017. [Erratum in Cell Cycle 17: 264–265, 2018.] doi: 10.1080/15384101.2017.1338985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fenton RA, Moeller HB, Hoffert JD, Yu MJ, Nielsen S, Knepper MA. Acute regulation of aquaporin-2 phosphorylation at Ser-264 by vasopressin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 3134–3139, 2008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712338105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gharbi-Ayachi A, Labbé JC, Burgess A, Vigneron S, Strub JM, Brioudes E, Van-Dorsselaer A, Castro A, Lorca T. The substrate of Greatwall kinase, Arpp19, controls mitosis by inhibiting protein phosphatase 2A. Science 330: 1673–1677, 2010. doi: 10.1126/science.1197048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giansanti P, Stokes MP, Silva JC, Scholten A, Heck AJ. Interrogating cAMP-dependent kinase signaling in Jurkat T cells via a protein kinase A targeted immune-precipitation phosphoproteomics approach. Mol Cell Proteomics 12: 3350–3359, 2013. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O113.028456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Golkowski M, Shimizu-Albergine M, Suh HW, Beavo JA, Ong SE. Studying mechanisms of cAMP and cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase signaling in Leydig cell function with phosphoproteomics. Cell Signal 28: 764–778, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guan Y, Zhang Y, Breyer RM, Fowler B, Davis L, Hébert RL, Breyer MD. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits renal collecting duct Na+ absorption by activating the EP1 receptor. J Clin Invest 102: 194–201, 1998. doi: 10.1172/JCI2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gunaratne R, Braucht DW, Rinschen MM, Chou CL, Hoffert JD, Pisitkun T, Knepper MA. Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis reveals cAMP/vasopressin-dependent signaling pathways in native renal thick ascending limb cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 15653–15658, 2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007424107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hasler U, Vinciguerra M, Vandewalle A, Martin PY, Féraille E. Dual effects of hypertonicity on aquaporin-2 expression in cultured renal collecting duct principal cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 1571–1582, 2005. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004110930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hébert RL, Jacobson HR, Breyer MD. PGE2 inhibits AVP-induced water flow in cortical collecting ducts by protein kinase C activation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 259: F318–F325, 1990. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1990.259.2.F318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirota K, Hirota T, Aguilera G, Catt KJ. Hormone-induced redistribution of calcium-activated phospholipid-dependent protein kinase in pituitary gonadotrophs. J Biol Chem 260: 3243–3246, 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoffert JD, Fenton RA, Moeller HB, Simons B, Tchapyjnikov D, McDill BW, Yu MJ, Pisitkun T, Chen F, Knepper MA. Vasopressin-stimulated increase in phosphorylation at Ser269 potentiates plasma membrane retention of aquaporin-2. J Biol Chem 283: 24617–24627, 2008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803074200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoffert JD, Nielsen J, Yu MJ, Pisitkun T, Schleicher SM, Nielsen S, Knepper MA. Dynamics of aquaporin-2 serine-261 phosphorylation in response to short-term vasopressin treatment in collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F691–F700, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00284.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoffert JD, Pisitkun T, Wang G, Shen RF, Knepper MA. Quantitative phosphoproteomics of vasopressin-sensitive renal cells: regulation of aquaporin-2 phosphorylation at two sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 7159–7164, 2006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600895103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoffert JD, van Balkom BW, Chou CL, Knepper MA. Application of difference gel electrophoresis to the identification of inner medullary collecting duct proteins. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F170–F179, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00223.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Isobe K, Jung HJ, Yang CR, Claxton J, Sandoval P, Burg MB, Raghuram V, Knepper MA. Systems-level identification of PKA-dependent signaling in epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114: E8875–E8884, 2017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1709123114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kachhap SK, Faith D, Qian DZ, Shabbeer S, Galloway NL, Pili R, Denmeade SR, DeMarzo AM, Carducci MA. The N-Myc down regulated gene1 (NDRG1) is a Rab4a effector involved in vesicular recycling of E-cadherin. PLoS One 2: e844, 2007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kishore BK, Chou CL, Knepper MA. Extracellular nucleotide receptor inhibits AVP-stimulated water permeability in inner medullary collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 269: F863–F869, 1995. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1995.269.6.F863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kishore BK, Ginns SM, Krane CM, Nielsen S, Knepper MA. Cellular localization of P2Y2 purinoceptor in rat renal inner medulla and lung. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 278: F43–F51, 2000. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.1.F43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knepper MA, Kwon TH, Nielsen S. Molecular physiology of water balance. N Engl J Med 372: 1349–1358, 2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1404726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kortenoeven ML, Fenton RA. Renal aquaporins and water balance disorders. Biochim Biophys Acta 1840: 1533–1549, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee JW, Chou CL, Knepper MA. Deep sequencing in microdissected renal tubules identifies nephron segment-specific transcriptomes. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 2669–2677, 2015. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014111067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loo CS, Chen CW, Wang PJ, Chen PY, Lin SY, Khoo KH, Fenton RA, Knepper MA, Yu MJ. Quantitative apical membrane proteomics reveals vasopressin-induced actin dynamics in collecting duct cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 17119–17124, 2013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309219110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Masuda S, Hattori A, Matsumoto H, Miyazawa S, Natori Y, Mizutani S, Tsujimoto M. Involvement of the V2 receptor in vasopressin-stimulated translocation of placental leucine aminopeptidase/oxytocinase in renal cells. Eur J Biochem 270: 1988–1994, 2003. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matsumura Y, Uchida S, Rai T, Sasaki S, Marumo F. Transcriptional regulation of aquaporin-2 water channel gene by cAMP. J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 861–867, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]