Abstract

Background:

In primary analyses, DBT was associated with greater reduction in self-harm during treatment than IGST. The objective of this paper is to examine predictors and moderators of treatment outcomes for suicidal adolescents who participated in a randomized controlled trial evaluating Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) and Individual/Group Supportive Therapy (IGST).

Methods:

Adolescents (N=173) were included in the intent-to-treat sample and randomized to receive six-months of DBT or IGST. Potential baseline predictors and moderators were identified within four categories: demographics, severity markers, parental psychopathology, and psychosocial variables. Primary outcomes were suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-injury evaluated at baseline, midtreatment (three months), and end of treatment (six months) via the Suicide and Self-Injury Interview (Linehan et al., 2006). For each moderator or predictor, a generalized linear mixed model was conducted to examine main and interactive effects of treatment and the candidate variable on outcomes.

Results:

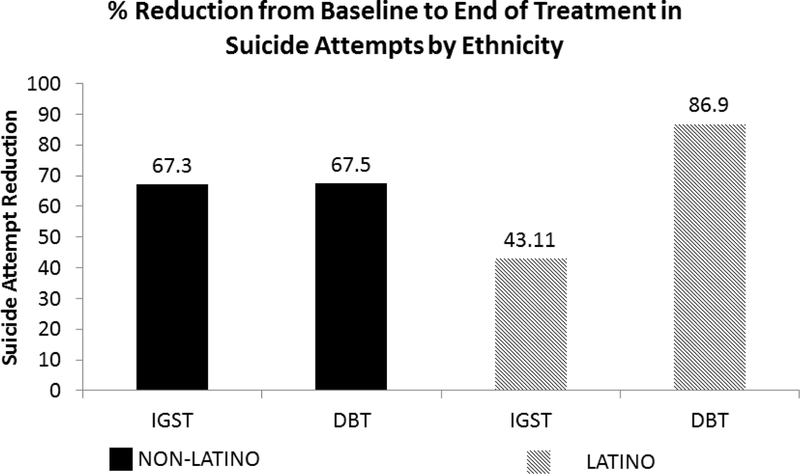

Adolescents with higher family conflict, more extensive self-harm histories, and more externalizing problems produced on-average more reduction on SH frequency from baseline to post-treatment. Adolescents meeting BPD diagnosis were more likely to have high SH frequency at post-treatment. Analyses indicated significant moderation effects for emotion dysregulation on NSSI and SH. DBT was associated with better rates of improvement compared to IGST for adolescents with higher baseline emotion dysregulation and those whose parents reported greater psychopathology and emotion dysregulation. A significant moderation effect for ethnicity on suicide attempts over the treatment period was observed, where DBT produced better rate of improvement compared to IGST for Hispanic/Latino individuals.

Conclusions:

These findings may help to inform salient treatment targets and guide treatment planning. Adolescents that have high levels of family conflict, externalizing problems, and increased level of severity markers demonstrated the most change in self-harm behaviors over the course of treat and benefitted from both treatment interventions. Those with higher levels of emotion dysregulation and parent psychopathology may benefit more from the DBT treatment.

Keywords: moderators, predictors, dialectical behavior therapy, treatment response

Introduction

Suicide is a significant public health problem and a leading cause of death for adolescents in the United States. Both suicide attempts (SA) and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) are risk factors for future SAs. Promising therapeutic interventions to reduce self-harm (SH: SAs and NSSI) are emerging (Glenn, Franklin, & Nock, 2015; Ougrin, Tranah, Stahl, Moran, & Asarnow, 2015); however, the number of treatment studies demonstrating significant decreases in SH is low and our understanding of the optimal intervention strategies for specific subgroups of youth remains underexplored.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) is the only treatment for adolescents that has replicated effects in decreasing self-harm behaviors across two randomized controlled trials (McCauley et al., 2018; Mehlum et al., 2014, 2016). The Collaborative Adolescent Research on Emotions and Suicide (CARES) study was a multisite clinical trial conducted in the United States that compared the short and longer-term efficacy of DBT and Individual and Group Supportive Therapy (IGST)-an active intervention used in prior studies and matched in terms of common factors-in reducing suicide attempts. Two prior publications describe the study aims, rationale and design (Berk et al., 2014) as well as the primary outcomes of the interventions (McCauley et al., 2018). In short, results indicate that DBT was more effective than IGST at decreasing suicidal ideation (SI), NSSI, SAs, and SH at the end of active treatment, but between-group differences were no longer significant by the 12-month follow-up (McCauley et al., 2018). A secondary analysis of clinically significant change, defined as no self-harm at follow-up found that a substantial percentage of youth in each condition continued to have self-harm beyond the active intervention. Specifically, only 51.2% of DBT youth and 32.2% of IGST youth were free from SH one year from their baseline assessment. One participant, in the IGST condition, died by suicide during the study, after active treatment around the 9 month assessment. These outcomes underscore the need for further clarification of predictors and moderators of treatment response in order to identify optimal intervention strategies for suicidal adolescents.

Predictors of adolescent SH have been well studied in clinical and epidemiological samples (Bridge et al., 2007; Bridge, Goldstein, & Brent, 2006; Franklin et al., 2017; Goldsmith, Pellmar, Kleinman, & Bunney, 2002; Gould, Greenberg, Velting, & Shaffer, 2003), however, there have been fewer studies examining predictors of SA and SH as treatment outcomes. Over the past 10 years, there has been a sharp increase in research examining interventions specifically designed for SH in youth, with DBT reaching well-established criteria (Level 1) for treatment efficacy and several other interventions in the probably efficacious category (Level 2; Glenn et al., 2015; Ougrin et al., 2015). Despite the advancement in the literature on therapeutic strategies, very little is known about which adolescents who present with repetitive SH and emotion dysregulation will benefit the most from treatment or how to match treatment decisions to a youth’s unique needs. A few notable exceptions have evaluated predictors and moderators of treatment response. The Youth Nominated Support (YST) intervention is an adjunctive intervention for the high risk transition period as youth move from inpatient to outpatient levels of care, that was tested in two RCTs (King et al., 2009, 2006). Both sex and multiple suicide attempt history emerged as moderators of the YST suggesting that this intervention may be most useful for specific subgroups of adolescents (e.g., females or multiple attempters). However, there was not a main effect of the experimental treatment, and the moderation results did not replicate across the two studies, suggesting future research is needed. The Treatment of Adolescent Suicide Attempters (TASA) also evaluated predictors of suicide events during this open feasibility trial of monotherapy or combined treatment of cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for adolescents who had current depressive diagnoses and history of a suicide attempt (Brent et al., 2009). High levels of baseline suicidal ideation and self-reported (but not interview reported) depression, a history of maltreatment (particularly sexual abuse), history of multiple suicide attempts, lower lethality of suicide attempts, and lower levels of family cohesion were strong clinical predictors of a suicidal event (including self-harm or suicidal ideation requiring emergency evaluation). In addition, adolescents who had a decline in suicidal ideation and improved functional status earlier in treatment were less likely to have a suicidal event compared to those whose recovery in those domains occurred later in treatment. There was no differential effect of treatment type (monotherapy compared to combined therapy). The findings from the TASA study were important in understanding predictors of self-harm outcomes with carefully controlled and documented treatment exposures, however, there were several limitations that motivated the current research questions. Specifically, the non-randomized design allows for limited understanding of moderators, the sampling characteristics included only depressed youth, and the assessment schedule provided limited understanding of emotion regulation strategies.

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of pretreatment variables on treatment response to help understand who benefits from treatment. Because of the limited prior work addressing predictors and moderators of self-harm interventions for youth, this study evaluated variables that were identified based on the literature on SH risk factors, predictors identified from the two treatment studies reviewed above, and factors relevant to the theoretical models guiding the CARES treatment approaches. For DBT, SH is conceptualized based on the biosocial model (Linehan, 1993), with SH seen as a means of reducing pervasive emotion dysregulation occurring as a result of the transaction between emotional vulnerability and environmental invalidation early in life. Treatment focuses on teaching coping skills to manage strong negative emotions instead of engaging in SH, validation and building a life worth living (Linehan, 1993). In IGST, SH is conceptualized as being driven by experiences of social isolation, interpersonal rejection, and thwarted belongingness (Joiner, 2009). Treatment focuses on reducing SH by providing unconditional positive regard activating the individual’s ability to experience social support. Other demographic and psychosocial variables were explored without a priori hypotheses. Putative predictive/moderator variables were categorized into four domains: 1) demographic factors, 2) severity markers, 3) parental psychopathology, and 4) psychosocial variables. Our goal was to evaluate two main processes. First, we evaluated predictors of treatment response generally. Variables were considered predictors if they had a main effect on the four primary indicators of suicide risk (SA, NSSI, SH, and SI) regardless of treatment condition. The evaluation of predictors provides information about who is likely to benefit from treatment in general, determining appropriate expectations for treatment, and significant targets that may need to be addressed for any treatment to work. The second type of process evaluated was moderation, or the factors that differentiate those more likely to benefit from DBT or IGST (Kraemer, Kiernan, Essex, & Kupfer, 2008). Moderation, or an interaction between a variable and a treatment outcome, is important to understand as it can guide differential treatment selection based on an individual’s presenting problems. Exploratory hypotheses were: 1) severity of psychopathology will be a predictor of treatment outcome (e.g., adolescents with less severe psychopathology [self-harm histories, comorbidities] will show greater reductions in self-harm), and 2) emotion regulation will moderate treatment response such that adolescents with more dysregulation will respond better to DBT than IGST.

Methods

Participants

As described in McCauley and colleagues (2018), participants were 173 adolescents, who were at high risk for suicide given self-harm and clinical characteristics, and were recruited at four study sites. All participants had a previous lifetime suicide attempt, repetitive self-harm in the past 12 weeks, borderline personality disorder characteristics, and clinically significant suicidal ideation. Their demographic and clinical characteristics are detailed in a previous publication (McCauley et al., 2018). Participants were randomly assigned to one of two treatment conditions: Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT; N=86) or Individual/Group Supportive Therapy (IGST; N=87). Participants were matched across conditions within sites on age, number of suicide attempts, number of previous self-injuries, and use of psychotropic medications. Randomization status and sequence were concealed from recruitment and assessment staff (i.e., single blind trial). Participants were informed of their treatment assignment at the first therapy session. For more detailed study design information we refer readers to Berk and colleagues (2014), and those interested in primary outcomes are referred to McCauley and colleagues (2018).

The sample had a mean age of 14.89 years (SD=1.47), 95% female participants, and were 56.4% white (Hispanic 27.49% Native American .58%, African American 7.02%, Asian American 5.85%, Other 2.34%). 17.65% of families had an annual income of less than $30,000. Participants met criteria for the following diagnoses: 83.81% depressive disorders, 54.10% anxiety disorder, .68% eating disorders, 53.20% borderline personality disorder.

Procedures

Assessments were conducted at baseline (pre-treatment), 3-months (mid-treatment), 6-months (end of treatment). Assessors were naïve to treatment condition and trained to criteria for administration/scoring for each measure. For interview measures after initial training, assessors were observed and interviews were co-rated by a “gold standard” interviewer until they demonstrated .80 inter-rated reliability, thereafter every 15th interview was co-rated to insure ongoing reliability. Measures were selected because of their established psychometric properties and their use across multiple clinical trials in order to provide the ability to generalize results across studies. All predictors and moderators used in analyses are from the baseline assessment. Information regarding treatment procedures, randomization, and participant flow through the trial are detailed in McCauley and colleagues (2018).

Primary and secondary outcomes

As outlined in McCauley and colleagues (2018), primary outcomes of SAs, NSSI, and SH (including SAs and NSSI, SH without suicidal intent) were measured using the Suicide Attempt and Self Injury Interview (SASII). The SASII is a reliable and valid measurement for the frequency, intent, and medical severity of suicide attempts and NSSI acts (Linehan, Comtois, Brown, Heard, & Wagner, 2006). The Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Junior (SIQ-JR ) assessed suicidal ideation (Reynolds, 1988).

Baseline measures used in analyses

Demographics.

The Demographic Data Schedule (Linehan, 1982) was used to collect demographic information. Race (classified as Caucasian, African American, Asian American, or Other), ethnicity (Hispanic/Latino or not), age (in years), and family income (in four categories ranging from <$5000 to > $50,000) was assessed from parent report (Linehan, 1982).

Severity markers

Prior self-harm.

Severity of prior self-harm was calculated as the number of self-harm episodes (SA and NSSI) in year before treatment based on the SASII.

Externalizing problems.

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) was used to assess externalizing problems. The CBCL has 113-items rated on a 3-point scale (0 = not true, 2 = very true) and yields broad-and narrow-band symptomatology categories. For the purposes of this study, the broad-band category of externalizing problems was used.

Comorbid internalizing diagnoses.

Psychiatric diagnoses were made using the mood, anxiety, psychosis and eating disorder modules from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Aged Children (KSADS)(Geller, Zimerman, Williams, & Frazier, 1996) administered to adolescents and their parents. The number of comorbid diagnoses from KSADS ranged from zero to six and included depressive disorders (MDD and dysthymia), anxiety disorders (panic disorder, generalized anxiety), and eating disorders (anorexia and bulimia).

Substance use.

The Drug Use Screening Inventory-Revised (DUSI-R) assessed the severity of problems related to alcohol and drug involvement. The DUSI-R is a multidimensional instrument that quantifies frequency of drugs and alcohol use, and associated consequences of use. The overall problem density score, ranging from 0 to 100, was used as the severity of maladjustment related to substance abuse. Higher scores reflect higher problems related to substances (Tarter & Hegedus, 1991).

Trauma symptoms.

The UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM IV is a self-report questionnaire to screen for exposure to traumatic events and assess PTSD symptoms in youth (Pynoos, Rodriguez, Steinberg, Stuber, & Frederick, 1998). The screen probes lifetime trauma exposures and the reaction index scale assesses the frequency of occurrence of PTSD symptoms during the past month on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = none of the time; 4 = most of the time). The items map directly onto DSM IV intrusion, avoidance, and arousal criteria, while two additional items assess associated features (fear of recurrence and trauma-related guilt). The traumatic experiences and reaction index total scores were used in analyses. All youth completed the trauma history section and if trauma history was positive, completed the symptoms of PTSD.

Borderline Personality Disorder diagnosis.

The Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV, Axis II (SCID-II; First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams, & Benjamin, 1997) was used to evaluate borderline personality disorder diagnosis).

Parental psychopathology

Emotional distress.

The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983) is a screening tool for detecting clinical symptoms as indicators of emotional distress. Parents completed the 53-item BSI as a self-report questionnaire. Parents rated physical and psychological symptoms occurring in the preceding week on a 5-point Likert-type scale (0=not at all; 4=extremely). Items are scored onto a Global Severity Index, a composite score representing general distress.

Psychosocial factors

Emotion dysregulation.

The Difficulties with Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004) is a 36-item multidimensional self-report measure assessing individuals’ characteristic patterns of emotion dysregulation (e.g., “When I’m upset, I lose control over my behaviors.”). Participants rate items on a 5-point Likert scale (1= almost never, 5 = almost always). The total score was utilized and ranged from 36 to 180, with higher scores indicating greater emotion dysregulation. Adolescents and parents self-reported their own emotion regulation difficulties.

Adolescent-parent conflict.

Adolescents and parents both completed the Conflict Behavior Questionnaire-20 (CBQ-20; Prinz, Foster, Kent, & O’Leary, 1979). The score representing the adolescent`s view of the dyad was used as an index of parent and adolescent conflict. The CBQ-20 consists of 20 items assessing conflict and negative communication of family experiences rated as mostly true or mostly false. High scores represent negative perceptions of interactions and higher conflict.

Statistical analyses

As reported in McCauley et al. (2018), to accommodate continuous suicide ideation and ordinal acts (i.e. SA, NSSI, SH), analyses implemented mixed effects repeated measures techniques accommodating nonlinear change over time from baseline to 6-months following treatment (i.e., end of treatment). These analyses included treatment group (DBT, IGST) as the between-subjects factor, time (baseline, 3, 6 months) as the within subjects’ factor, and group-by-time interactions. Pairwise contrasts from the mixed-effects models were used to evaluate between-group differences.(Agresti, 1990; Kenward & Roger, 1997) Outcomes analyses adjusted for site and assessed for differential treatment effects across site by including a site-by-treatment interaction. There was no evidence of an informative attrition mechanism, meaning that the difference in study conditions is not biased by the missing data (Hedecker & Gibbons, 1997; Rubin, 1979).

To preserve power, predictors or moderators of interest were introduced one per equation to our original models. Original models were augmented to include the respective potential predictor or moderator. Predictors were determined by the main effect of the respective term, whereas, moderators were determined by significant interaction with intervention. Continuous predictors/moderators were centered for analysis. When analyses involving a continuous predictor/moderator were significant, we probed these by estimating and contrasting estimates of the impact of a 1 standard deviation (SD) increase in the continuous predictor. Clinical interpretation of the impact of the potential predictors/moderators were based on odds ratios (ORs) for ordinal outcomes and estimated change in suicide ideation outcome. For the predictors, the impact is quantified overall, whereas, for moderators, the impact is quantified within each intervention. Under moderation, significant moderation effects exist when there is significant heterogeneity of the impact of the 1SD increase in the potential moderator between IGST and DBT. For the binary predictors, odds ratios and on-average change estimate are based on derivation of odds ratio change and on-average change in ideation for between levels with one level serving as the reference group. For the binary moderators and ordinal acts, probing the moderation effects replicate the reported findings in McCauley et al. (2018), where we derive the odds ratios for DBT compared to IGST per level of the moderator, where odds ratio above/below 1 indicate the odds of being at a higher ordinal level are more/less for DBT compared to IGST. For the suicide ideation, we derive the estimated change in ideation for DBT compared to IGST per level of the moderator.

All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (2015) with procedures SAS Proc Mixed for continuous ideation and SAS Proc GLIMMIX for ordinal acts. Denominator degrees of freedom for all mixed-effects models were constrained using the between-within technique with the resulting degrees of freedom constrained dependent on the effective sample size (Littell et al., 2006). All tests are two-tailed with robust standard errors.

The study was designed to have a sample of 170 which is powered accounting for 20% attrition to detect a small-medium eta-squared of 4% for prediction and sufficiently powered to detect a moderation effect corresponding to a large effect (Cohen’s d>0.9) for one level of the moderator and a negligible difference (Cohen’s d=0.0) for the other level of the moderator. Our study has adequate power only for large moderation effects thus risking Type II error, and to maintain power we will conduct a number of tests without correcting for Type I error.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Baseline sample characteristics and the balance across DBT and IGST condition are presented in Table 1. There is no imbalance on any measures across intervention.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Descriptive Statistics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGST | DBT | t (df) | p | |||||

| Variable | na | M | SD | n | M | SD | ||

| Age | 87 | 15.06 | 1.43 | 86 | 14.76 | 1.50 | 1.35 (171) | 0.18 |

| Prior NSSI | 87 | 27.54 | 51.75 | 86 | 25.09 | 42.35 | 0.34 (171) | 0.73 |

| Prior Self-harm | 87 | 28.89 | 51.95 | 86 | 27.37 | 43.31 | 0.21 (171) | 0.83 |

| Nr of Comorbid Diagnoses | 86 | 3.25 | 1.67 | 86 | 2.86 | 1.57 | 1.60 (170) | 0.11 |

| Substance Use Problem Density | 83 | 20.96 | 26.11 | 83 | 22.73 | 24.77 | −0.45 (164) | 0.66 |

| Externalizing Problems | 79 | 19.86 | 11.67 | 85 | 20.68 | 10.39 | −0.48 (162)b | 0.29 |

| Global Severity Index | 84 | 0.59 | 0.49 | 85 | 0.63 | 0.57 | −0.46 (167) | 0.64 |

| Adolescent Emotion Regulation | 85 | 125.8 | 20.02 | 85 | 125.5 | 21.30 | 0.10 (168) | 0.92 |

| Parent Emotion Regulation | 84 | 71.76 | 19.30 | 84 | 68.44 | 19.10 | 1.12 (166) | 0.26 |

| Family Conflict | 85 | 11.04 | 5.75 | 85 | 10.68 | 6.16 | 0.39 (168) | 0.70 |

| PTSD-Severity Score b | 45 | 40.51 | 14.62 | 45 | 36.11 | 17.13 | 1.31 (88) | 0.19 |

| n | % | n | % | χ2 (1) | p | |||

| % white | 86 | 53 | 86 | 58 | 0.37 | 0.54 | ||

| % Latino/Hispanic | 86 | 28 | 86 | 28 | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||

| % with Income of $50,000 or more | 69 | 59 | 73 | 71 | 2.19 | 0.14 | ||

| % Trauma Exposure | 86 | 59 | 86 | 62 | 0.09 | 0.76 | ||

| % BPD diagnosis | 87 | 56 | 86 | 50 | 0.69 | 0.40 | ||

Number of adolescents with the completed measure

PTSD symptoms are only assessed for adolescents who endorse a trauma history, therefore the PTSD Severity Score is available for a subset of adolescents.

Predictors

Each potential predictor was added to the respective mixed effects model. Results of the significance testing of the potential predictor at post-treatment are illustrated in Table 2. In summary, race was a significant predictor of SI and prior self-harm history was a significant predictor of SA, NSSI and SH, family conflict and externalizing problems were significant predictors of NSSI and SH. These findings are described in detail below.

Table 2:

Results from prediction and moderation analyses

| Baseline Measure | Outcome | Predictor Post Treatment (6 mo) |

Moderator Post Treatment (6 mo) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEMOGRAPHICS | |||

| Age | SUICIDE ATTEMPTS | F(1,165)=0.75, p=0.39 | F(1,163)=0.15, p=0.70 |

| NSSI | F(1,165)=0.16, p=0.69 | F(1,163)=0.05, p-0.78 | |

| SELF-HARM | F(1,165)=0.31, p=0.58 | F(1,163)=0.46, p=0.50 | |

| SUICIDAL IDEATION | F(1,165)=0.25, p=0.62 | F(1,163)=0.37, p=0.55 | |

| Race | SUICIDE ATTEMPTS | F(1,164)=2.61, p=0.11 | F(1,162)=1.07, p=0.30 |

| NSSI | F(1,164)=0.04, p=0.84 | F(1,162)=0.92, p=0.33 | |

| SELF-HARM | F(1,164)=0.09, p=0.77 | F(1,162)=0.22, p=0.64 | |

| SUICIDAL IDEATION | F(1,164)=12.94, p=0.004 | F(1,162)=2.56, p=0.11 | |

| Ethnicity | SUICIDE ATTEMPTS | F(1,164)=0.21, p=0.64 | F(1,162)=5.51, p=0.02 |

| NSSI | F(1,164)=2.58, p=0.11 | F(1,162)=0.56, p=0.46 | |

| SELF-HARM | F(1,164)=2.34, p=0.13 | F(1,162)=1.21, p=0.27 | |

| SUICIDAL IDEATION | F(1,164)=2.60, p=0.11 | F(1,162)=0.42, p=0.52 | |

| Income | SUICIDE ATTEMPTS | F(1,154)=0.17, p=0.68 | F(1,152)=0.08, p=0.78 |

| NSSI | F(1,154)=0.51, p=0.45 | F(1,152)=0.19, p=0.67 | |

| SELF-HARM | F(1,154)=0.11, p=0.74 | F(1,152)=0.64, p=0.43 | |

| SUICIDAL IDEATION | F(1,154)=0.43, p=0.51 | F(1,152)=0.57, p=0.35 | |

| SEVERITY MARKERS | |||

| Prior NSSI | SUICIDE ATTEMPTS | F(1,165)=4.38, p=0.04 | F(1,165)=0.20, p=0.65 |

| NSSI | F(1,165)=11.98, p=0.01 | F(1,163)=0.82, p=0.37 | |

| SELF-HARM | F(1,165)=8.74, p=0.01 | F(1,163)=0.83, p=0.36 | |

| SUICIDAL IDEATION | F(1,165)=2.85, p=0.09 | F(1,163)=3.72, p=0.054 | |

| Prior Self-harm | SUICIDE ATTEMPTS | F(1,165)=6.09, p=0.01 | F(1,163)=0.10, p=0.75 |

| NSSI | F(1,165)=8.71, p=0.01 | F(1,163)=0.63, p=0.43 | |

| SELF-HARM | F(1,165)=11.98, p=0.01 | F(1,163)=0.82, p=0.37 | |

| SUICIDAL IDEATION | F(1,165)=3.81, p=0.05 | F(1,163)=2.83, p=0.09 | |

| Number of Comorbid Diagnoses | SUICIDE ATTEMPTS | F(1,164)=0.09, p=0.77 | F(1,162)=0.45, p=0.50 |

| NSSI | F(1,164)=1.53, p=0.22 | F(1,162)=1.31, p=0.25 | |

| SELF-HARM | F(1,164)=0.52, p=0.47 | F(1,162)=1.30, p=0.25 | |

| SUICIDAL IDEATION | F(1,164)=0.02, p=0.88 | F(1,162)=2.81, p=0.09 | |

| Substance Use Problem Density | SUICIDE ATTEMPTS | F(1,158)=0.58, p=0.46 | F(1,156)=0.04, p=0.84 |

| NSSI | F(1,158)=0.25, p=0.62 | F(1,156)=0.00, p=0.99 | |

| SELF-HARM | F(1,158)=0.46, p=0.50 | F(1,156)=0.64, p=0.43 | |

| SUICIDAL IDEATION | F(1,158)=0.35, p=0.56 | F(1,156)=0.48, p=0.49 | |

| Externalizing Problems | SUICIDE ATTEMPTS | F(1,156)=0.77, p=0.38 | F(1,154)=2.80, p=0.095 |

| NSSI | F(1,156)=5.66, p=0.02 | F(1,154)=0.09, p=0.76 | |

| SELF-HARM | F(1,156)=7.44, p=0.01 | F(1,154)=0.32, p=0.57 | |

| SUICIDAL IDEATION | F(1,156)=0.27, p=0.60 | F(1,154)=2.20, p=0.14 | |

| Meets BPD | SUICIDE ATTEMPTS | F(1,165)=4.94, p=0.03 | F(1,163)=1.73, p=0.19 |

| NSSI | F(1,165)=0.35, p=0.55 | F(1,163)=1.57, p=0.21 | |

| SELF-HARM | F(1,165)=0.24, p=0.62 | F(1,163)=0.73, p=0.39 | |

| SUICIDAL IDEATION | F(1,165)=0.04, p=0.84 | F(1,163)=1.43, p=0.23 | |

| PARENTAL PSYCHOPATHOLOGY | |||

| Global Severity Index | SUICIDE ATTEMPTS | F(1,161)=0.06, p=0.80 | F(1,159)=0.72, p=0.40 |

| NSSI | F(1,161)=1.81, p=0.18 | F(1,159)=4.19, p=0.04 | |

| SELF-HARM | F(1,161)=1.29, p=0.26 | F(1,159)=4.74, p=0.03 | |

| SUICIDAL IDEATION | F(1,161)=0.87, p=0.35 | F(1,159)=0.40, p=0.53 | |

| PSYCHOSOCIAL FACTORS | |||

| Adolescent Emotion Regulation | SUICIDE ATTEMPTS | F(1,162)=2.86, p=0.09 | F(1,160)=0.18, p=0.67 |

| NSSI | F(1,162)=0.07, p=0.79 | F(1,160)=3.92, p=0.05 | |

| SELF-HARM | F(1,162)=0.04, p=0.84 | F(1,160)=3.87, p=0.05 | |

| SUICIDAL IDEATION | F(1,162)=0.00, p=0.98 | F(1,160)=1.40, p=0.23 | |

| Parent Emotion Regulation | SUICIDE ATTEMPTS | F(1,160)=1.34, p=0.25 | F(1,158)=1.91, p=0.17 |

| NSSI | F(1,160)=1.80, p=0.18 | F(1,158)=4.71, p=0.03 | |

| SELF-HARM | F(1,160)=0.95, p=0.33 | F(1,158)=3.96, p=0.05 | |

| SUICIDAL IDEATION | F(1,160)=0.80, p=0.37 | F(1,158)=0.61, p=0.43 | |

| Family Conflict | SUICIDE ATTEMPTS | F(1,162)=2.68, p=0.10 | F(1,160)=0.00, p=0.99 |

| NSSI | F(1,162)=8.75, p=0.003 | F(1,160)=0.53, p=0.47 | |

| SELF-HARM | F(1,162)=4.24, p=0.04 | F(1,160)=0.10, p=0.76 | |

| SUICIDAL IDEATION | F(1,162)=0.15, p=0.69 | F(1,160)=1.50, p=0.22 | |

| Trauma Exposure | SUICIDE ATTEMPTS | F(1,164)=0.38, p=0.54 | F(1,162)=0.48, p=0.49 |

| NSSI | F(1,164)=2.43, p=0.12 | F(1,162)=1.11, p=0.29 | |

| SELF-HARM | F(1,164)=2.28, p=0.13 | F(1,162)=0.76, p=0.38 | |

| SUICIDAL IDEATION | F(1,164)=1.94, p=0.16 | F(1,162)=2.57, p=0.11 | |

| PTSD Symptom Severity Score | SUICIDE ATTEMPTS | F(1,82)=0.28, p=0.60 | F(1,80)=1.78, p=0.18 |

| NSSI | F(1,82)=0.32, p=0.57 | F(1,80)=0.14, p=0.71 | |

| SELF-HARM | F(1,82)=1.15, p=0.28 | F(1,80)0.01, p=0.93 | |

| SUICIDAL IDEATION | F(1,82)=0.27, p=0.60 | F(1,80)=0.16, p=0.69 | |

Demographic factors.

Non-white adolescents SIQ-JR reduced from 55.73 (SD=15.75) at pre-treatment to 25.53 (SD=20.12) at post-treatment, whereas, white adolescents reduced from 58.08 (SD=16.52) at pre-treatment to 38.97 (SD=23.48). We see white adolescents had less reduction from pre-treatment to post-treatment and were on-average 13.44 (SE=3.95) points higher on the SIQ-Jr compared to non-white adolescents at post-treatment.

Severity markers.

Severity on all indicators of prior self-harm predicted a higher level of self-harm at end of treatment. Level of prior self-harm predicted an increase in the odds of being in a higher ordinal level at end of treatment, with odds ratios of 1.04 (CI: 1.01–1.07) on SA; 1.22 (CI: 1.10–1.36) on NSSI; and 1.22 (CI: 1.10–1.35) on SH. Adolescents with more episodes of self-harm at baseline were more likely to have higher ordinal outcomes for each outcome. Externalizing problems also emerged as a predictor of NSSI and SH at end of treatment with odds ratios of 0.65 (CI: 0.44–0.95) and 0.68 (CI: 0.47–0.99), respectively. This indicates that for each standard deviation increase in parent reported externalizing problems, the odds of being in a higher ordinal level of NSSI and SH frequency are less compared to parent reporting a lower level of externalizing problems. That is, youth with high baseline externalizing problems and low SH severity demonstrated a significant decrease in SH frequency by the end of treatment. Additionally, we see a significant effect for whether the adolescent met BPD at pre-treatment in the prediction of suicide attempts, where meeting BPD predicted an increase in the odds of being in a higher ordinal level at end of treatment, with odds ratios of 4.36 (CI: 1.45–13.14) on SA.

Psychosocial variables.

Family conflict predicted NSSI and SH at end of treatment with odds ratios of 0.77 (CI: 0.70–0.86) and 0.76 (CI: 0.65–0.90), which indicated that for each standard deviation increase in conflict the odds of being in a higher ordinal level of NSSI and SH frequency are less compared to those with lower conflict.

Parental psychopathology.

The global severity of parents’ self-reported psychopathology did not predict outcomes.

Moderators

Results of the significance testing of the potential moderators following six months of treatment (treatment end) are illustrated in Table 2. Probing moderation effects is based on the odds ratio per standard deviation change of the continuous moderators within each intervention group for the ordinal measures (SA, NSSI, SH), and estimated change in ideation per standard deviation change of the moderator within each intervention group. For the demographic and binary moderators, we derive the odds for DBT compared to IGST on SA, NSSI, and SH and the on-average difference in ideation between DBT and IGST for each demographic/binary moderator, which allows for direct comparison to the overall intervention effect reported in McCauley et al. (2018). Unlike our assessment of prediction where significance was identified by whether the confidence intervals for the odds ratios contained one, for the moderation effects interpretation of significance is based on observing the difference in the confidence intervals for DBT and IGST, where one or both may contain one, but still yield significant moderation.

At the end of treatment, parental psychopathology, adolescent emotion dysregulation, and parent emotion dysregulation were significant moderators of NSSI and SH. There are no moderation findings for SI. Ethnicity was also a significant moderator of SA.

Demographics.

The odds ratio (OR) of 0.93 (0.23–3.79) for non-Latino adolescents compared to an OR of 0.04 (0.003–0.37) for Latino adolescents indicated a significant moderation effect for ethnicity. The OR is below one for both non-Latino and Latino groups indicating lower odds for DBT being in a higher ordinal level compared to IGST. The moderation effect for ethnicity is being driven by the 95% reduction in the OR between non-Latino and Latino group, indicating an on-average significantly lower likelihood for Latino adolescents in DBT to increase SA compared to their IGST counterparts. To further understand the Latino moderation effect, Figure 1 presents the observed rate of any suicide attempt at pre-treatment and post-treatment by intervention and non-Latino/Latino groupings. Among the non-Latino group IGST rate of any suicide attempt reduces by 67.3% whereas DBT rate reduces by 67.5%. Among the Latino group IGST rate of any suicide attempt reduces by 43.1% whereas DBT rate reduces by 86.9%. We have little difference in rate of reduction between IGST and DBT within the non-Latino group but a more than doubled difference in rate of reduction between IGST and DBT within the Latino group, with the higher reduction observed within DBT.

Figure 1.

Percent reduction from baseline to end of treatment in suicide attempts by ethnicity.

Severity.

No severity markers (self-harm history, comorbid diagnoses, externalizing problems, substance use) moderated treatment effects.

Parental psychopathology.

Severity of parental psychopathology moderated treatment with an OR of 1.39 (CI: 0.85–2.25) for IGST and 0.84 (0.49–1.44) for DBT for NSSI, and an OR of 1.43 (CI: 0.87–2.32) for IGST and 0.77 (0.45–1.33) for DBT for SH. For IGST, an OR larger than one corresponds to an increase in the odds of being in a higher ordinal category for each standard deviation increase in the psychopathology severity. In DBT, an OR less than one corresponds to a decrease in the odds of being in a higher ordinal category for each standard deviation increase in the moderator.

Psychosocial variables.

For adolescent emotion dysregulation, ORs are 1.85 (CI: 1.13–3.03) for IGST and 1.11 (CI: 0.71–1.73) for DBT on NSSIs and 1.64 (CI: 1.02–2.65) for IGST and 1.15 (CI: 0.74–1.77) for DBT on SH. Odds ratios larger than one for each intervention arms indicates increases in adolescent emotion dysregulation scores corresponding to a higher likelihood of more acts. The higher OR indicates a higher likelihood to have more NSSI and SH per standard deviation increase in adolescent emotion dysregulation for IGST compared to DBT. For the parental emotion dysregulation, ORs are 1.22 (CI: 0.77–1.97) for IGST and 0.87 (CI: 0.50–1.53) for DBT on NSSIs and 1.28 (CI: 0.80–2.05) for IGST and 0.88 (CI: 0.51–1.53) for DBT on SH. An OR larger than one within IGST corresponding to higher odds of being in a higher ordinal level per standard deviation increase, while within DBT an OR less than one corresponding to a lower odds of being in a higher ordinal level per standard deviation increase.

Discussion

Recent reviews highlight that little is known about the presenting factors that affect the efficacy of therapeutic interventions for suicidal adolescents (Glenn et al., 2015; Ougrin et al., 2015). Evaluation of predictors and moderators in clinical trials are an important area of research as the results inform reasonable treatment expectations and contribute to the consideration of differential treatment pathways based on the youth’s initial presentation. This methodologically rigorous RCT with multiple sites, randomization, repeated measurement of outcomes using validated instruments and blind assessors allowed for the exploration of these questions with a group of high risk adolescents selected based on repetitive self-harm, current suicidality, emotion dysregulation, borderline personality traits, and multiple comorbidities. Given the lack of well-established interventions for treatment of suicide and self-harm in adolescents, this research provides a unique contribution to informing treatment prognosis and planning for youth at high risk for suicide.

With regard to predictors of treatment response, adolescents who had more extensive self-harm histories, more externalizing symptoms, non-white racial identity, and higher conflict families at the start of treatment improved more than their counterparts at treatment end. Significant moderators of end of treatment outcome included ethnicity, parental psychopathology, and both adolescent and parent level of emotional regulation. DBT was associated with a better rate of improvement from baseline to post-treatment compared to IGST for adolescents who identified as Latina, had higher baseline emotion dysregulation, and whose parents had higher baseline emotion dysregulation and more severe parental psychopathology. Contrary to our hypotheses, adolescents who presented with more severe self-harm history and comorbidities did not appear to benefit differentially from DBT treatment exposure compared to IGST. Additionally, there was no evidence of support for our hypothesis that social functioning would moderate treatment effects. This could be due to limitations in our measurement or power to detect small effects.

The analyses examined four primary outcomes related to suicide risk, SI, SA, NSSI and SH. However, there was differential moderation depending on the outcome with ethnicity the only moderator of treatment response for suicide attempts, whereas level of emotion dysregulation, and parental psychopathology affected NSSI and total self-harm. Predictors of suicide events identified in prior work include high levels of suicidal ideation, self-reported depression, a history of maltreatment, two or more previous attempts, lower lethality of the index attempt, and lower levels of family cohesion (Brent et al., 2009). This study expands on prior work identifying clinical predictors by evaluating treatment moderation effects. Similar to prior work, self-harm history was an important predictor of treatment response and change in future self-harm. Severity indicators (self-harm history, externalizing problems, BPD diagnosis) were important predictors of future self-harm during treatment, but were not associated with differential treatment response. Aligning with DBT theory of self-harm, youth and parents with higher levels of emotion dysregulation responded better to DBT than IGST suggesting the value of prioritizing DBT treatment for families with high levels of dysregulation to prioritize DBT treatment. The finding that Latina ethnicity was associated with differential response is intriguing and worthy of future exploration. The extant literature suggests an equivalent response between Latina and non-Latina adolescents with respect to clinical response, remission, symptom severity and functioning is observed (e.g., Pina, Silverman, Fuentes, Kurtines & Weems, 2003; Pina, Zerr, Villata, & Gonzales, 2012). Although not evaluated in the context of the trial, we’re curious about the prior treatment experiences given that Latinas are less likely than non-Latina whites to use outpatient mental health services and receive evidence based interventions (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). In addition, further exploration of the influence of cultural values, acculturation, and language of the family may impact the acceptability and impact of the intervention. For example, DBT may have had more impact due to incorporation of family in the skills group which may be in line with cultural values. We hope future research evaluates these hypotheses.

Limitations

The merits of this study must be considered with its limitations in mind. The sample of adolescents included in the study represents those at the highest risk for suicide. There were few adolescents who had mild symptomatology and the intent to treat analyses are limited to the sample of 173 adolescents enrolled in the trial. It is likely that there are other important moderator effects that were not detected due to power. In addition, our candidate moderators were guided by the theoretical orientation of the treatments as well as extant literature, but the variables included are not exhaustive and consideration of other variables is needed in future research. For example, despite aggressive recruitment of males we did not enroll sufficient males in the study to evaluate sex as a demographic variable influencing treatment response. This study is also limited in its measurement of externalizing problems as a questionnaire measure was utilized as opposed to a diagnostic interview in order to minimize participant burden. Analytical limitations consisted of incomplete response in the potential predictors/moderators and no adjustment to the Type I error rate for the multiple tests. Direct comparison of confidence intervals for our moderation effects may overlap, whereas the significance testing is based on difference of the difference attributable to the proposed moderator within each intervention. Missed response on the potential predictors/moderators were minimal and random. Small number of patients/parents did not answer some questions (i.e. family income) or did not complete specific questionnaires (i.e. externalizing problems). With respect to Type I error rate, we point to Rothman (1990) and Althouse (2016) who indicate that unadjusted multiple comparisons are needed for complex phenomenon and additional studies are needed to confirm our results. Finally, although evaluators were blind to treatment assignment, clinicians and families were not and therefore may influence the results.

Conclusions

In summary, we evaluated predictors and moderators for treatment response in the context of a randomized controlled trial of two psychotherapies targeting the reduction of suicide attempts, NSSI, and suicidal ideation. Results reveal that several baseline variables predicted reduction in suicide risk outcomes consistent with past research including prior self-harm, and adolescent-reported family conflict. For youth with comorbid diagnoses and significant self-harm histories, DBT and IGST both lead to improvement. DBT produced a better rate of improvement for adolescents who were Latino/a, had parents who reported psychopathology, and for adolescents and parents with higher levels of emotion dysregulation. Triaging adolescents with these characteristics to DBT programs may maximize positive treatment outcomes.

Key points.

Adolescent prior self-harm, externalizing problems, and reported family conflict were significant predictors of change in self-harm, NSSI, and suicidal ideation, where adolescents with higher family conflict and less severe self-harm history produced on-average more reduction in SH from baseline to post-treatment.

DBT produced better rate of improvement compared to IGST for adolescents who were emotionally dysregulation, and whose parents had higher baseline emotion dysregulation and psychopathology.

Clinicians could consider either IGST or DBT for adolescents with self-harm histories whose parents are well regulated and do not have impairing psychopathology. Adolescents with emotional dysregulation and parents with psychopathology and emotion dysregulation may benefit more from DBT than IGST.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health grants 5R01MH090159 (Drs. Linehan and McCauley, PIs at University of Washington/Seattle Children’s), R01MH93898 (Drs. Berk and Asarnow, PIs at Los Angeles sites), and K12HS022982 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Adrian). The trial was prospectively registered on the U.S. National Institutes of Health clinicaltrials.gov registry -CT01528020.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2001). ASEBA School-age Forms & Profiles: An Integrated System of Multi-informant Assessment. ASEBA. [Google Scholar]

- Agresti A (1990). Categorical data analysis. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Althouse AD (2016). Adjust for multiple testing?: It is not that simple. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 101, 1644–1645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk M, Adrian M, McCauley E, Asarnow J, Avina C, & Linehan M (2014). Conducting research on adolescent suicide attempters: Dilemmas and decisions. The Behavior Therapist / AABT, 37(3), 65–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent D, Greenhill L, Compton S, Emslie G, Wells K, Walkup J, … Turner JB (2009). The Treatment of Adolescent Suicide Attempters (TASA) Study: Predictors of Suicidal Events in an Open Treatment Trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(10), 987–996. 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b5dbe4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge JA, Iyengar S, Salary CB, Barbe RP, Birmaher B, Pincus HA, … Brent DA (2007). Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA, 297(15), 1683–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge Jeffrey A., Goldstein TR, & Brent DA (2006). Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(3–4), 372–394. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01615.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry J, Rohde P, Simons A, Silva S, Vitiello B, Kratochvil C, … TADS Team. (2006). Predictors and moderators of acute outcome in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(12), 1427–1439. 10.1097/01.chi.0000240838.78984.e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Huang X, … Nock MK (2017). Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 143(2), 187–232. 10.1037/bul0000084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, & Frazier J (1996). WASH-U-KSADS (Washington University at St.Louis Kiddie and Young Adult Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia -Lifetime and Present Episode Version for DSM-IV). St Louis, MO. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn CR, Franklin JC, & Nock MK (2015). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44(1), 1–29. 10.1080/15374416.2014.945211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith SK, Pellmar TC, Kleinman AM, & Bunney WE (Eds.). (2002). Reducing suicide: A national imperative. National Academies Press; Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=9xGdAgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT17&dq=Reducing+Suicide:+A+National+Imperative.&ots=mRHF6lpIjD&sig=gBYeJMJxXA7YVmWtsM_pr5HauI4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould MS, Greenberg T, Velting DM, & Shaffer D (2003). Youth suicide risk and preventive interventions: A review of the past 10 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(4), 386–405. 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046821.95464.CF [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, & Roemer L (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE Jr, Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Rudd MD. The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide: Guidance for Working with Suicidal Clients. American Psychological Association.; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenward MG, & Roger JH (1997). Small sample inference for fixed effects from restricted maximum likelihood. Biometrics, 53(3), 983–997. 10.2307/2533558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CA, Klaus N, Kramer A, Venkataraman S, Quinlan P, & Gillespie B (2009). The Youth-Nominated Support Team for Suicidal Adolescents – Version II: A Randomized Controlled Intervention Trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(5), 880–893. 10.1037/a0016552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CA, Kramer A, Preuss L, Kerr DCR, Weisse L, & Venkataraman S (2006). Youth-Nominated Support Team for Suicidal Adolescents (Version 1): a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(1), 199–206. 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Kiernan M, Essex M, & Kupfer DJ (2008). How and Why Criteria Defining Moderators and Mediators Differ Between the Baron & Kenny and MacArthur Approaches. Health Psychology, 27(2 Suppl), S101–S108. 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM (1982). Demographic Data Schedule (DDS). University of Washington, Seattle, WA: Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan Marsha M., Comtois KA, Brown MZ, Heard HL, & Wagner A (2006). Suicide attempt self-injury interview (SASII): Development, reliability, and validity of a scale to assess suicide attempts and intentional self-injury. Psychological Assessment, 18(3), 303–312. 10.1037/1040-3590.18.3.303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD, Schabenberger O, (2006). SAS System for Mixed Models,2nd ed, Cary NC: SAS Institute Inc [Google Scholar]

- McCauley E, Berk MS, Asarnow JR, Adrian M, Cohen J, Korslund K, … Linehan MM (2018). Efficacy of Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Adolescents at High Risk for Suicide: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(8), 777–785. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlum L, Tørmoen AJ, Ramberg M, Haga E, Diep LM, Laberg S, … Grøholt B (2014). Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with repeated suicidal and self-harming behavior: A randomized trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 53(10), 1082–1091. 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlum L, Ramberg M, Tørmoen AJ, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy compared with enhanced usual care for adolescents with repeated suicidal and self-harming behavior: Outcomes over a one-year follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(4):295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Bernal G, Lau A, Kohn L, Hwang W, LaFromboise T. (2005). State Of The Science On Psychosocial Interventions For Ethnic Minorities. Annual Review of ClinicalPsychology, , 113–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ougrin D, Tranah T, Stahl D, Moran P, & Asarnow JR (2015). Therapeutic interventions for suicide attempts and self-harm in adolescents: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(2), 97–107.e2. 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piña AA, Silverman WK, Fuentes RM, Kurtines WM, Weems CF (2003). Exposure-Based Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment for Phobic and Anxiety Disorders: Treatment Effects and Maintenance for Hispanic/Latino Relative to European-American Youths. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 1179–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piña AA, Zerr AA, Villalta IK, & Gonzales NA (2012). Indicated prevention and early intervention for childhood anxiety: a randomized trial with Caucasian and Hispanic/Latino youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 80, 940–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz RJ, Foster S, Kent RN, & O’Leary KD (1979). Multivariate assessment of conflict in distressed and nondistressed mother-adolescent dyads. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 12(4), 691–700. 10.1901/jaba.1979.12-691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pynoos RS, Rodriguez N, Steinberg A, Stuber M, & Frederick C (1998). UCLA PTSD Index Trauma Screen for DSM IV. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM (1988). Suicidal ideation questionnaire: Professional Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman KJ (1990). No Adjustments are Needed for Multiple Comparisons. Epidemiology 1, 43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. (2015). SAS® 9.4 Language Reference: Concepts, 5th Edition, . Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE & Hegedus AM. (1991) The drug use screening inventory: Its applications in the evaluation and treatment of alcohol and other drug abuse. Alcohol Research and Health, 15, 65–75. [Google Scholar]