Abstract

Objective

Informal care, the provision of unpaid care to dependent friends or family members, is often associated with physical and mental health effects. As some individuals are more likely to provide caregiving tasks than others, estimating the causal impact of caregiving is difficult. This systematic literature review provides an overview of all studies aimed at estimating the causal effect of informal caregiving on the health of various subgroups of caregivers.

Methodology

A structured literature search, following PRISMA guidelines, was conducted in 4 databases. Three independent researchers assessed studies for eligibility based on predefined criteria. Results from the studies included in the review were summarized in a predefined extraction form and synthesized narratively.

Results

The systematic search yielded a total of 1,331 articles of which 15 are included for synthesis. The studies under review show that there is evidence of a negative impact of caregiving on the mental and physical health of the informal caregiver. The presence and intensity of these health effects strongly differ per subgroup of caregivers. Especially female, and married caregivers, and those providing intensive care appear to incur negative health effects from caregiving.

Conclusion

The findings emphasize the need for targeted interventions aimed at reducing the negative impact of caregiving among different subgroups. As the strength and presence of the caregiving effect differ between subgroups of caregivers, policymakers should specifically target those caregivers that experience the largest health effect of informal caregiving.

Keywords: Long-term care, Informal care, Caregiver burden, Systematic literature review

Many individuals provide care for a spouse, family member, friend, or neighbor who needs help with running the household or personal care. Providing such care can, however, be very demanding, and might lead to physical strain, fatigue, or stress. Several studies have been carried out to assess whether informal care indeed is correlated with the health of the caregiver (e.g., Beach, Schulz, Yee, & Jackson, 2000; Schulz et al., 1997), which is confirmed by prior systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses reviewing these studies (e.g., Pinquart & Sörensen, 2003, 2007; Vitaliano, Zhang, & Scanlan, 2003).

However, these reviews did not distinguish between studies that merely study the correlation between health and caregiving and those that estimate a causal effect. The crucial difference is that the former set of studies conflates differences in health state caused by caregiving tasks with differences caused by other factors. These factors, such as lifestyle and pre-existing health differences are largely unobserved and vary over time, and hence cannot be controlled for in multivariate regressions, even when panel data are available. Hence, these estimates are biased estimates of the true effect that caregiving has on health (Little & Rubin, 2000).

Quasi-experimental methods offer a solution to this problem by carefully modeling the selection into the treatment and control group. Doing so, these methods allow for comparison between caregivers and noncaregivers and hence make sure that the change in caregiver health is caused by the provision of care and by nothing else (Antonakis, Bendahan, Jacquart, & Lalive, 2014). A recent strand of the literature on the relationship between caregiving and health (e.g., Coe & Van Houtven, 2009) makes use of these methods to eliminate bias in the estimates of the caregiving effect caused by unobserved factors and thus allows for causal inference.

To our knowledge, we are the first to review this relatively new strand of literature. To provide an objective, transparent, and replicable overview of the literature, we carry out this review systematically following PRISMA guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009). Next to focusing on the causal impact of informal care, we will add to the literature by paying specific attention to subgroups of caregivers. The health impact of care might namely strongly differ by, for example, gender or the type of care provided (Penning & Wu, 2016). We sought to address the following questions: What causal impact does providing informal care to elderly or older family member have on the health of the caregiver? And how does this caregiving effect differ between subgroups of caregivers?

Method

Eligibility Criteria

We included studies based on the following eligibility criteria:

1. The article focuses on informal caregiving to elderly or older family members.

2. The article estimates the health impact of informal caregiving on the caregiver.

3. The article is aimed at finding a causal relation between informal caregiving and caregiver health using any one of the following methods: propensity score analysis, simultaneous equation models (instrumental variables), regression discontinuity designs, difference-in-difference models or Heckman selection models.

4. The article is written in English.

5. The article is not a conference abstract, letter, note, or editorial.

We defined informal care as providing care to a person in need and limited this definition to care to elderly persons or older family members. This focus excludes looking after (healthy) children or grandchildren, but does not impose any restriction on the age of the caregiver.

To specify our search to studies making causal estimations, we only include articles using quasi-experimental methods that enable causal estimations in nonexperimental settings. We limited our search to five methods for causal inference listed by Antonakis, Bendahan, Jacquart, and Lalive (2010, 2014). Table 1 provides a short explanation of these methods. As especially health of individuals could already differ before starting providing care, we exclude studies making use of a matching design that does not match on health of the caregiver.

Table 1.

Quasi-Experimental Methods for Inferring Causality in Nonexperimental Settings

| Method | Brief description |

|---|---|

| Propensity score analysis | Compare individuals who were selected to treatment to statistically similar controls using a matching algorithm |

| Simultaneous equation models | Using “instruments” (exogenous sources of variable that do not correlate with the error term) to purge the endogenous × variable from the bias |

| Regression discontinuity | Select individuals to treatment using a modeled cutoff |

| Difference-in-differences models | Compare a group who receive an exogenous treatment to a similar control group over time |

| Heckman selection models | Predict selection to treatment (where treatment is endogenous) and then control for unmodeled selection to treatment in predicting y |

Note: Taken from Antonakis and colleagues (2010), for further explanations regarding the summed methods we refer to the original article.

Search Strategy and Data Sources

Our search strategy, which is available as Supplementary Material, was set up with the help of an information specialist. For all criteria, we defined keywords as well as Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and Embase Subject Headings (Emtree terms). Databases were searched for combinations of keywords and (if applicable) MeSH or Emtree-terms related to the eligibility criteria: informal caregiving, health impact, and older adults. Additionally, we limited our search to English language studies using one of the quasi-experimental methods to infer causality listed by Antonakis and colleagues (2010, 2014), and excluded abstracts, letters, or editorials.

The following databases covering social sciences as well as bio-medical literature were searched from database inception through April 1, 2018: MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, and Scopus. We did not search the CENTRAL database, which covers studies using RCTs, as our research question cannot be answered by studies using this research design. All search results were stored in RefWorks, our main platform for keeping track of the literature review. We did not register a systematic review protocol.

We furthermore used Google Scholar to identify any additional articles. This search engine could help in retrieving articles that (a) have not been published yet, or (b) missed relevant search terms in their title and abstract. For this manual search, we used a search strategy similar to the search string used for the other databases. We hand-searched the first 150 Google Scholar hits. When articles were deemed eligible for review, they were added to the list of full-text review articles.

Review Procedure

Three reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of all articles based on predefined eligibility criteria. Before commencing the review, the criteria were discussed to guarantee shared understanding. The researchers screened the articles (two researchers per article) based on title and abstract. To avoid bias, authors and journal names were not visible during this screening stage. If the article adhered to all inclusion criteria, it was then selected for full-text review. In this second stage, all included articles were reviewed full-text by two researchers based on the inclusion and exclusion restrictions. For both stages, differences in screening results were discussed and resolved by dialogue, and if needed the third researcher would act as judge.

Data Abstraction

Data were extracted from the articles included in the review using a predefined extraction table. The following items were recorded from each article: the author(s) and year of publication; country/region of interest; care recipient; definition of informal care; sample characteristics of the caregiver; health outcome measure; estimation technique; and main findings of the study. As we do not aim to provide a meta-analysis of the results, the main study findings were recorded qualitatively based on presence and direction, not on effect size. The results were synthesized in a narrative review.

Quality Assessment

To assess the methodological quality of the studies meeting inclusion criteria, methodological information from the articles was extracted using a predefined extraction form designed to fit the methodologies used in the included articles. This form summarized the most important methodological elements of the articles. We did not calculate quality scores for the studies, but instead explained the methodological differences between the studies in narrative terms.

To assess the quality of studies using propensity score analysis, we followed recent progress in the causal inference literature (Lechner 2009) and added a separate check. The quality of matching studies is dependent on the likelihood that the assumptions hold that (a) the propensity score is not affected by whether one is a caregiver (no reverse causality) and (b) there are no relevant remaining unobserved differences after matching (see Rosenbaum and Rubin (1983) for an overview of all assumptions). The matching approach proposed by Lechner (2009) makes it credible that these assumptions hold, as it suggests to match individuals on pretreatment covariates instead of current covariates and to stratify the sample according to care provision in the previous year. The latter suggestion means that individuals who recently started caregiving (and did not do so last year), are only compared with individuals that did not provide care last year either. Doing so, potential influence of the treatment status on the covariates is avoided, and pretreatment differences in health are controlled for. For the studies making use of matching techniques, we evaluated whether this approach is followed.

The quality of the instrumental variables is assessed based on instrument strength. For studies included in this review, it means that the effect of the instrumental variable, for example, a health shock of a parent, has a sufficiently strong effect on informal care provision. This strength of the instrumental variable can be assessed based on the F-statistic of excluded instruments. We follow the most commonly used rule of thumb that the F-statistic showing the strength of the instrument should be greater than 10 (Staiger & Stock, 1997).

Finally, we assess for all studies whether they accounted for the family effect. This effect refers to the impact of caring about an ill family member and is different from the caregiving effect related to the impact of caring for someone (Amirkhanyan & Wolf, 2006; Bobinac, van Exel, Rutten, & Brouwer, 2010). Recent literature highlights the importance of considering this effect, as not accounting for it leads to an overestimation of the caregiving effect (Roth, Fredman, & Haley, 2015).

Results

Search Results

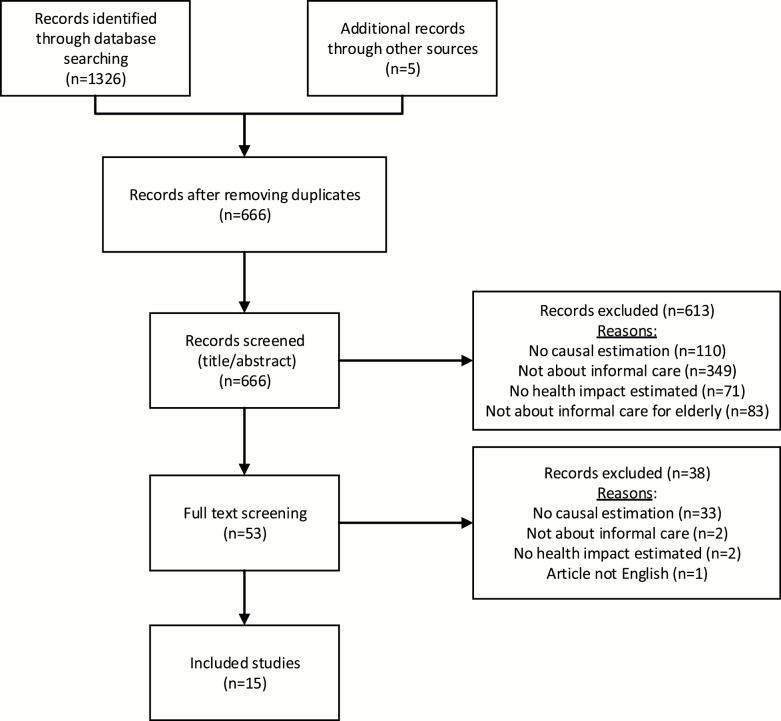

Our searches yielded 1,326 articles in total. After eliminating duplicates, our search findings totaled 661 articles. The hand-search resulted in five additional articles. From these 666 articles, 613 were excluded for a variety of reasons. Often the studies did not focus on informal caregiving but on another type of care. Furthermore, various studies were excluded as they did not estimate the impact of caregiving, but reviewed the efficacy of a specific intervention to improve the health of caregivers. Eventually, 53 articles were selected for full-text review. From these 53 articles, 38 were excluded in the full-text review round. The most prominent reason for exclusion at this stage was that a study did not use any of the defined methods to identify a causal effect. Eventually, 15 articles met all inclusion criteria and were included in this systematic literature review. Figure 1 depicts the flowchart of screening phases.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of screening phases.

All articles were published recently, the oldest dating from 2009 (Coe & Van Houtven, 2009), the most recent one published in 2017 (de Zwart, Bakx, & van Doorslaer, 2017). The articles were published in a variety of journals, mostly relating to gerontology or health economics. The articles cover various countries of interest, using European data (n = 6); Asian data (n = 4); U.S. data (n = 4), or Australian data (n = 1). An extensive overview of all articles is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics and Results of Reviewed Studies

| Authors | Country /region of interest |

Care recipient | Definition of informal care | Sample characteristics of caregivers | Health measure | Methods | Lechner (2009) matching procedure used | Results (if applicable subgroup for which effect is found) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brenna and Di Novi (2016) | Europe | Parent | Providing assistance to a parent, step-parent, or parent-in-law at least on a weekly basis Distinction: Intensive informal care (excludes caregivers helping with domestic chores) |

Women aged 50–75 | Depression (Euro-D) | PSM | Yes | ↑ Euro-D (Southern Europeans) larger effect when providing intensive informal care |

| Coe and Van Houtven (2009) | US | Parent | Spent at least 100 hr since previous wave/in the last 2 years on helping parents/mother/ father with basic personal activities like dressing, eating, and bathing |

Men and women aged 50–64, with only a mother alive | Mental health (CES-D 8); physical health (self-assessed health (SAH), diagnosed heart condition and blood pressure) | Simultaneous equation models (2SLS, Arellano-Bond) | N/A |

Continued caregiving:

↑ CES-D 8 (married males and females) ↑ Heart condition (single males) ↓ SAH (married females) ↑ SAH (married males) Effects after 2 years: ↑ CES-D 8 (married females) ↑ Heart condition (single males) Initial caregiving: ↑ CES-D 8 (married females) |

| Di Novi, Jacobs, and Migheli (2015) | Europe | Parent | Women providing care to elderly parents living in or outside the household in the past 12 months almost weekly or almost daily | Women, aged 50–65 having a parent with bad or very bad health | Self-assessed health; quality of life (CASP-12) | PSM | Yes | ↑ SAH (North and Continental European caregivers) ↓ CASP-12 (Continental European caregivers) ↑ self-realized and pleasure in life (caregivers in Continental and Mediterranean Europe) ↓ able to control life and autonomous (caregivers from Continental Europe) |

| Do, Norton, Stearns, and Van Houtven (2015) | South Korea | Parent (in-law) | Any informal care provided to parents-in-law | Women with living parent (in-law) aged 45+ | Pain affecting daily activities; fair or poor self-rated health; any outpatient care use; OOP spending for outpatient care; any prescription drug use; OOP spending prescription drugs |

Simultaneous equation models (2SLS, IV-probit) |

N/A | ↑ Pain affecting daily activities, health self-rated as poor, OOP outpatient care (daughters and daughters-in-law) ↑ Any outpatient care use, any prescription drug use (daughters) |

| Fukahori, Sakai, and Sato (2015) | Japan | Family member living in the same household | A family member in the same household who is in need of care | Males and their spouses aged 50–64 | Employment rate, working hours, self-reported health, satisfaction with leisure time and life | PSM | No | ↓ Likelihood of participating in work No impact on SAH or life satisfaction (results not presented in article, mentioned in text) |

| Goren, Montgomery, Kahle-Wrobleski, Nakamura, and Ueda (2016) | Japan | Adult relatives with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia | Persons currently caring for an adult relative, with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia | Men and women aged 18+ | Comorbidities; depression (PHQ-9); work productivity (WPAI); SF-36 PCS and MCS; health care resource utilization | PSM | No | ↑ PHQ-9, MDD ↓ SF-36 PCS, MCS and health utilities ↑ Depression, insomnia, anxiety, and pain ↑ Absenteeism, overall work impairment, and activity impairment ↑ Emergency room and traditional provider visits in the past 6 months |

| Heger (2017) | Europe | Parent | Any caregiving activities to parent (help with personal care and practical household help provided outside or inside the household) Distinction: daily, weekly and any frequency of caregiving |

Men and women aged 50–70 | Depression (EURO-D); indicator whether someone suffers from ≥4 depressive symptoms | Simultaneous equation models | N/A | ↑ Euro-D, 4+ depressive symptoms (females) larger effect when more intensive informal care |

| Hernandez and Bigatti (2010) | US | Individual with Alzheimer’s disease or a physical disability | Caring for an individual with Alzheimer’s disease or a physical disability within the past year | Hispanic Americans aged 65+ | Depression (CES-D 20) | Direct matching | No | ↑ CES-D 20 |

| Hong, Han, Reistetter, and Simpson (2016) | South Korea | Spouse with dementia | Persons living with a spouse with dementia | Men and women aged 19+ | Physician-diagnosed stroke | PSM | No | ↑ Odds of stroke |

| Kenny, King, and Hall (2014) | Australia | Spouse, adult relative, elderly parent (in law) | Any time spent caring for a disabled spouse, adult relative or elderly parent/parent-in-law in a typical week Distinction: Care burden: Low (less than 5 hr/w), moderate (5–19 hr/w) and high (20 or more hr/w) |

16+ males and females | SF-36 PCS and MCS | PSM | Yes |

After 2 years:

↑ PCS (high care) Effects for subgroups: ↓ PCS (high caregiving females with a job) ↓ MCS (high caregiving females with a job) ↑ MCS (high caregiving males without job) After 4 years: ↓ PCS (low and moderate care) ↓ MCS (moderate and high care) |

| Rosso and colleagues (2015) | US | Family member or friend | Currently helping ≥1 sick, limited, or frail family member, or friend on a regular basis? Distinction: Low frequency ≤2 times per week; high frequency ≥3 times per week |

Women, 65–80 years old | Walking speed, grip strength, chair stands | PSM | No |

After 6 years:

↑ grip strength (low-frequency caregivers) |

| Schmitz and Westphal (2015) | Germany | Unknown | Providing ≥2 hr per day on care and support for persons in need of care on a typical weekday | Women aged 18+ | SF-12v2 MCS and PCS | PSM | Yes |

Short term:

↓ MCS Longer term: No effects |

| Stroka (2014) | Germany | Anyone in need | Self-reported informal caregiving to sickness fund to receive allowance Distinction: Level of care needed |

Males and females aged 35+ | Drug intake | PSM + D-in-D | Yes | ↑ Intake of antidepressants, tranquilizers, analgesics and gastrointestinal agents Larger effect when more intensive care |

| Trivedi and colleagues (2014) | US | Family member or friend | Any care provision in the past month to a friend or family member who has a health problem, long-term illness, or disability | Noninstitutionalized U.S. civilian population aged ≥18 years | Self-assessed mental health; general health; perceived social and emotional support; sleep hygiene | PSM | No | ↑ Report >15 days of poor mental health and inadequate emotional support; ↓ Report fair or poor health (females) ↑ Report fair or poor health (males) ↓ Receive recommended amount of sleep ↑ Fall asleep unintentionally during the day |

| de Zwart and colleagues (2017) | Europe | Partner | Daily or almost daily caregiving activities (help with personal care) to partner for ≥3 months in the past 12 months | Males and females aged 50+ | Prescription drugs usage; the number of doctor visits in the past 12 months; EURO-D depression scale; self-perceived health | PSM | Yes |

Short term:

↑ Euro-D, ↓ self-reported health; ↑ prescription drug use(females), ↑ doctor visits (females) Longer- term: No effect |

Note: PSM = propensity score matching; 2SLS = two-stage least square; D-in-D = difference-in-difference; IV = instrumental variable; MCS and PCS = Mental Component Scale and Physical Component Scale.

Methodological Quality of Studies Included in the Review

Table 3 presents an extensive overview of the methods per study meeting the inclusion criteria. Three of the 15 studies use simultaneous equation models to estimate the causal impact of providing care. The instrumental variables used in these studies are roughly similar, including indicators of either the health (Do et al., 2015) or the widowhood of the parent (Coe & Van Houtven, 2009; Heger, 2017). The F-statistics show that the instrumental variables applied in the main analyses of these studies all have sufficient strength.

Table 3.

Methodology of Reviewed Studies

| Authors | Data source | Sample representativeness | Data type | Sample size | Study design | Matching or IV strategy | Methodological quality | Family effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brenna and Di Novi (2016) | SHARE, 2004–2007 (2 waves) |

Representative for the noninstitutionalized population aged 50 and older | Longitudinal | Matched treated/ Control 1,138/3,292 |

PSM | Matched on: demographics; family composition; socioeconomic variables; information on parents receiving care; self- reported probability of receiving an inheritance; mental health status and caregiver status at the first wave | Matching quality: matched on caregiver status and mental health in first wave |

Not specifically considered |

| Coe and Van Houtven (2009) | HRS, 1992–2004 (7 waves) |

Nationally representative for community-based population | Longitudinal | Sample continued caregiving = 2,557 Sample initial caregiving = 8,007 |

Simultaneous equation models (2SLS, Arellano-Bond) |

IV continued caregiving: death of mother IV initial caregiving: number of boys/girls in the household |

Strength of instrument: F-statistics: 16–837 (continued caregiving) 6–18 (initial caregiving) |

Not specifically considered |

| Di Novi and colleagues (2015) | SHARE, 2004 and 2006/2007 | Representative for the noninstitutionalized population aged 50 and older | Longitudinal | Matched treatment/ control 535/1,825 |

PSM | Matched on: socioeconomic variables; employment; family composition; occupation and income; previous SAH, CASP and caregiving status | Matching quality: Matched on caregiving status, SAH and CASP in first wave |

Not specifically considered |

| Do and colleagues (2015) | Korean LSA, 2006–2010 (3 waves) |

Nationally representative study of noninstitutionalized adults aged 45 years or older | Longitudinal | n = 2,528 (daughters-in-law) n = 4,108 (daughters) | Simultaneous equation models (2SLS, IV-probit) |

IV: ADL limitations of the mother(-in-law) and of the father(-in-law) | Strength of instrument: F-statistics: 86 (daughter- in-law) and 37 (daughter) | Aim to avoid family effect by focusing on physical health and care for parents-in-law |

| Fukahori and colleagues (2015) | Japanese panel survey on middle-aged persons, 1997–2005 | Randomly selected from the national population | Longitudinal | Matched treated/control 155/155 (males) 188/188 (spouses) |

PSM | Matched on: employment, SAH, retirement, age, education, and wage | Matching quality: Not matched on pretreatment status |

Not specifically considered |

| Goren and colleagues (2016) | Japan National Health and Wellness Surveys 2012–2013 |

Stratified by sex and age to ensure representativeness of adult population | Cross-sectional | Matched treatment/ control 1,297/1,297 |

PSM | Matched on: sex, age, BMI, exercise, alcohol, smoking, marital status, CCI (Charlson comorbidity index), insured status, education, employment, income, and children in household | Matching quality: not matched on pretreatment status |

Not specifically considered |

| Heger (2017) | SHARE, 2004–2013 (4 waves) | Representative for the noninstitutionalized population aged 50 and older | Longitudinal |

n = 3,669 (female) n = 2,752 (male) |

Simultaneous equation models | IV: Indicator of whether one parent is alive | Strength of instrument: F-statistics 18–47 |

Estimate family effect by adding health of parent as variable to model |

| Hernandez and Bigatti (2010) | HEPESE, 2000/2001 | Representativeness not discussed in the article | Longitudinal (one wave used) | Matched treatment/ control 57/57 | Direct matching | Matched on: age, gender, socioeconomic status, self-reported health, and level of acculturation | Matching quality: not matched on pretreatment status |

Not specifically considered |

| Hong and colleagues (2016) | Korea Community Health Survey, 2012–2013 | Representative of the entire community- dwelling adult population in South Korea | Cross-sectional | Matched treatment/ control 3,868/3,868 |

PSM | Matched on: age, sex, education, household income, insurance type, current smoker, current drinker, and stress level | Matching quality: not matched on pretreatment status |

Not specifically considered |

| Kenny and colleagues (2014) | HILDA, 2001–2008 | Representative sample of private Australian households | Longitudinal | Matched treatment/ control 424/424 |

PSM | Matched on: age, sex, marriage/partner, children, work hours, income, education, country of birth, chronic health condition limiting work, partner with a chronic health condition, another household member with a chronic health condition, having at least one living parent and baseline year | Matching quality: matched on baseline characteristics (pretreatment) |

Not specifically considered |

| Rosso and colleagues (2015) | Woman’s Health Initiative Clinical Trial, 1993–1998 |

Representativeness of sample not mentioned. Participants were recruited at clinical centers across the United States from 1993 to 1998 to participate in clinical trials | Longitudinal | Matched treatment/ control 2,138/3,511 |

PSM | Matched on: sociodemographic variables and health (smoking, chronic illnesses, obesity status) | Matching quality: matching on baseline characteristics (not pretreatment) |

Not specifically considered |

| Schmitz and Westphal (2015) | GSOEP, 2002–2010 |

Representative longitudinal survey of households and persons living in Germany | Longitudinal | Matched treatment/ control 1,235/29,942 |

PSM | Matched on: age of mother/father; mother/ father alive; (age) partner; number of sisters; personality traits; socioeconomic variables; health status | Matching quality: Matching on health before treatment Sample stratified by care provision at t = −1 |

Not specifically considered |

| Stroka (2014) | Techniker Krankenkasser, 2007–2009 |

Administrative data from largest statutory sickness fund in Germany | Longitudinal | Matched treatment/ control 5,696/3,125,140 (males) 7,495/2,085,946 (females) |

PSM + D-in-D | Matched on: socioeconomic variables; employment; education; work position; health status | Matching quality: matched pretreatment, at baseline only noncarers |

Not specifically considered |

| Trivedi and colleagues (2014) | BRFSS, 2009/2010 |

Nationally representative survey in the United States | Cross-sectional | Matched treatment/ control 110,514/110,514 |

PSM | Matched on: socioeconomic variables; household situation; employment, income, veteran status, immunizations within the previous year, exercise, tobacco use, self-identified physical disability, obesity status; health care access; and survey characteristics | Matching quality: not matched on pretreatment status |

Not specifically considered |

| de Zwart and colleagues (2017) | SHARE, 2004, 2006, 2010, 2013 |

Representative for the noninstitutionalized population aged 50 and older | Longitudinal | Matched treatment/ control 404/10,293 |

PSM | Matched on: socioeconomic variables; household situation; wealth; health status; health and age of spouse | Matching quality: matched on pretreatment covariates + sample stratified by care provision at t = −1 |

Not specifically considered |

Note: SHARE = Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement Europe; HRS = Health & Retirement Study; HEPESE = Hispanic Established Populations for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly; HILDA = Household, Income & Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey; GSOEP = German Socio-Economic Panel; BRFSS = Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; PSM = propensity score matching; 2SLS = two-stage least square; D-in-D = difference-in-difference; IV = instrumental variable.

Most articles (n = 12) use a matching design to compare caregivers and noncaregivers. As mentioned in Method section, we only included studies that matched respondents on the health of the caregiver to avoid omitted variable bias. Six (Brenna & Di Novi, 2016; Di Novi et al., 2015; Kenny et al., 2014; Schmitz & Westphal, 2015; Stroka, 2014; de Zwart et al., 2017) of the 12 matching studies follow the approach of Lechner (2009) by matching on precaregiving variables and only comparing caregivers with noncaregivers who both did not provide care last year.

Only two of the studies under review (Do et al., 2015; Heger, 2017) specifically accounted for the family effect. Do and colleagues (2015) argued to avoid picking up the family effect by focusing on (a) physical health effects and (b) females who provide care to their parents-in-law. As the family effect relates to worrying about an ill family member, the authors assumed that these worries do not affect the physical health of the caregiver. They furthermore assumed that this family effect is absent or at least smaller if one’s parent-in-law falls ill rather than one’s own parent. Heger (2017) aimed to disentangle the family effect from the caregiving effect and estimated the family effect by including a variable representing “poor health of a parent” and the caregiving effect by including a variable representing “informal caregiving” in the model. None of the other studies accounted for the family effect, thereby potentially overestimating the effect of caregiving on health.

Comparability of Studies

The studies that we review use different methods, which complicates comparing effect sizes across studies because, even if estimated on the same study sample, the methods would yield estimates of the effect that are valid for other subgroups of the study samples. With a matching design, caregivers are matched to similar individuals who do not provide care. These studies hence estimated the average treatment effect on treated (ATET): the health impact of informal care for the current informal caregivers. When using instrumental variables in simultaneous equation models, the local average treatment effect (LATE) is estimated. This represents the health impact of caregiving for those who started caregiving in response to the instrument, that is, illness or widowhood of a parent.

Hence, there are two potential methodological reasons for any observed differences in effect size between studies included in this review. First, effect sizes could differ as the ATET measures the impact of any form of caregiving while the LATE measures the impact of caregiving in response to severe illness or decease. Second, some studies do not account for the family effect, which leads to different estimates.

The various definitions of informal caregiving and the variety of outcome measures further complicate comparison of the findings of these studies. The definition of informal caregiving differs per study from providing care to a parent (n = 5) or spouse (n = 1), caring for anyone/a family member or friend (n = 5), and informal care for someone with a specific illness (e.g., dementia; n = 2). Lastly, two studies (Fukahori et al., 2015; Hong et al., 2016) proxy for informal caregiving by defining caregivers as persons living together with a family member or spouse in need. Although these studies aimed to estimate the impact of informal care, and as such adhere to the inclusion criteria, these rough measures of informal care might lead to underestimations of the caregiving effect because many noncaregivers may be misclassified as caregivers.

In addition, various health measures were used to estimate the impact on health. Studies focus on the mental health impact (n = 3), the physical health impact (n = 4), or both (n = 8). These health states are measured via either validated health measures, drug prescription data, or information on health care usage. The studies also differ in their specification of caregiving, for example, by restricting the sample to respondents who provide more than 2 hr of informal care per day.

Synthesis of Results

The studies included in the review provide a fairly coherent picture. All studies find a short-term negative effect for certain subgroups of caregivers, except for the study by Fukahori and colleagues (2015). An explanation for this latter finding could be the very rough proxy of informal care used in this study: household members were assumed to provide informal care when someone in the household needs care.

While all but one of the studies found a negative effect on the short term, there are interesting differences in the effect sizes between and within the studies. The studies estimating mental health effects all found that caregiving might result in higher prevalence of depressive feelings and lowered mental health scores. Estimates of the physical health impact of informal care were less stable and differed in sign. Many studies found negative physical health effects of caregiving (Coe & Van Houtven, 2009; Do et al., 2015; Goren et al., 2016; Hong et al., 2016; Stroka, 2014; Trivedi et al., 2014; de Zwart et al., 2017). These effects relate to a wide variety of physical health outcomes such as increased drug intake (Stroka, 2014; de Zwart et al., 2017) and pain affecting daily activities (Do et al., 2015). In contrast to these negative effects, Di Novi and colleagues (2015), Trivedi and colleagues (2014), and Coe and Van Houtven (2009) found positive effects of informal caregiving on physical health for some specific subgroups. How physical health is measured appears to be crucial: when measured by self-assessed health, the short-run impact of caregiving is positive, whereas negative health effects are found when outcomes are measured by intake of drugs and reported pain. Di Novi and colleagues (2015) claimed that the positive impact of informal care on self-assessed health could be the result of a bias related to reference points. They argued that spending time with a person who is in poor health could lead to an increase in self-assessed health because people may take the poor health of the care recipient as a reference point, even though the objective health level of the caregiver could have decreased.

Next to differences with regards to the health outcomes studied, large heterogeneity exists with regard to the subgroup of caregivers for whom the effects are applicable. Many studies only estimated caregiving effects for females as they assumed that mostly women provide or are affected by informal care (Brenna & Di Novi, 2016; Di Novi et al., 2015; Do et al., 2015; Rosso et al., 2015; Schmitz & Westphal, 2015). Studies that did separately estimate health effects for males and females often found that health effects are larger or solely present for females (Heger, 2017; Stroka, 2014; de Zwart et al., 2017). Marital status also seemed to be of effect according to the study of Coe and Van Houtven (2009), which in most cases solely found health effects of informal care for married individuals.

The intensity of provided care appears to be another source of heterogeneity in the health effects of caregiving. Various studies compared average or moderate caregivers with intensive caregivers based on the hours of care provision. These studies (Brenna & Di Novi, 2016; Heger, 2017; Stroka, 2014) found larger health effects when more intensive care is provided.

A clear conclusion regarding the longer-term effects of informal caregiving cannot yet be drawn. As all studies used survey data, many were unable to estimate longer-term caregiving effects. Only five studies estimated effects over a longer period (Coe & Van Houtven, 2009; Kenny et al., 2014; Rosso et al., 2015; Schmitz & Westphal 2015; de Zwart et al., 2017). Both Schmitz and Westphal (2015) and de Zwart and colleagues (2017) did not find any longer-term effects of informal caregiving on health. Schmitz and Westphal concluded that there might not be large scarring effects of care provision; de Zwart and colleagues mentioned that selective attrition may have biased their results. The other three studies estimating longer-term effects found mixed results, showing both positive and negative effects of informal care. Kenny and colleagues (2014) found negative health effects 2 years after the start of caregiving for working female caregivers and positive effects for nonworking caregiving males. Rosso and colleagues (2015) grouped all persons who provide informal care at baseline and found that after 6 years low-frequency caregivers have greater grip strength (representing physical health) than noncaregivers. The authors, however, control for various health measures but not for baseline grip-strength and mention that the effect might be explained by existing precaregiving differences. The study by Coe and Van Houtven (2009) is the only one that compared persons who stopped providing care to persons who continued caregiving for two more years. They found negative mental health effects for females and negative physical health effects for males who continue caregiving.

Discussion

The aim of this systematic literature review was to understand the causal impact of providing informal care to an elderly person or older family members on the health of the caregiver. Prior reviews concluded that there is a correlation between informal caregiving and health (e.g., Pinquart & Sörensen, 2003, 2007; Vitaliano et al., 2003); the studies included in this review indicate that there is a causal negative effect of caregiving on health. This caregiving effect can manifest itself both in mental and physical health effects. Interestingly, the presence and intensity of these health effects differ strongly per subgroup of caregivers. Especially female, and married caregivers, and those providing intensive care appear to experience negative health effects of caregiving. These groups might have several other responsibilities on top of caregiving duties, thereby being more strongly affected by the caregiving tasks.

Our findings highlight the need for caregiving interventions and stress the importance of differentiating interventions by a subgroup of caregivers. There are mainly two kinds of potential strategies: (a) improving the coping skills of the caregiver or (b) reducing the amount of care to be provided by informal caregivers (Sörensen, Pinquart, & Duberstein, 2002). Examples of (a) include support groups that might help caregivers who experience stress and insecurity (Sörensen et al., 2002). Examples of (b) include interventions like subsidized professional home care and assistive technology that could relieve caregivers from some of their tasks (e.g., Marasinghe, 2015; Mortenson et al., 2012).

Although our study provides interesting insights into the differential impact of informal care on various subgroups of caregivers, additional research regarding this topic is needed. Understanding why some groups are more affected by informal caregiving than others may help policymakers in facilitating the best support for informal caregivers. Furthermore, given that most empirical studies solely estimated short-term effects, research is needed about the long-term effects of providing informal care to determine whether caregiving has scarring effects.

Facing a broad research question, we aimed to establish a proper balance between precision and sensitivity of our search strategy. To do so, we included the care recipient and the used research design as elements into our search strategy. As a result, we face the risk of excluding studies that did not specifically report the recipients of informal care or the used study design. Furthermore, it is important to note that by focusing on informal care to elderly or older family members, we excluded for example studies looking at provision of care for disabled children. As caregiving stress might differ for such subgroups of caregiving, we cannot generalize our results to the entire population of caregivers.

Our review highlights the importance of accounting for the family effect, that is, the impact of being worried about someone irrespective of providing care, when estimating the caregiving effect on the health of the caregiver. Only two of the studies under review accounted for this effect. Since the family effect might bias the estimates of the caregiving effect on health, disentangling both effects seems an important focus-point for future research.

For now, we conclude that there is evidence of negative health effects of informal caregiving for subgroups of caregivers, which stresses the need for targeted interventions aimed at reducing this negative impact. Investing in support for informal caregivers by offering relieve from caregiving tasks or by organizing support groups might reduce the negative consequences of informal caregiving. As the strength and presence of the caregiving effect strongly differ between subgroups of caregivers, policymakers should aim to target subgroups of caregivers that experience the largest impact of informal caregiving.

Funding

This study has been carried out with financial support from the Network for Studies on Pensions, Aging and Retirement. Grant name: Optimal saving and insurance for old age: The role of public-long term care insurance.

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sara Rellstab for her contributions to the review process and Wichor Bramer for his help with drafting the search query.

References

- Amirkhanyan A. A., & Wolf D. A (2006). Parent care and the stress process: Findings from panel data. Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61, S248–S255. doi:10.1093/geronb/61.5.s248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonakis J., Bendahan S., Jacquart P., & Lalive R (2010). On making causal claims: A review and recommendations. The Leadership Quarterly, 21, 1086–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.10.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antonakis J., Bendahan S., Jacquart P., & Lalive R (2014). Causality and endogeneity: Problems and solutions. In D.V. Day (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Leadership and Organizations (pp. 93–117). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beach S. R., Schulz R., Yee J. L., & Jackson S (2000). Negative and positive health effects of caring for a disabled spouse: Longitudinal findings from the caregiver health effects study. Psychology and Aging, 15, 259–271. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.15.2.259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobinac A., van Exel N. J., Rutten F. F., & Brouwer W. B (2010). Caring for and caring about: Disentangling the caregiver effect and the family effect. Journal of Health Economics, 29, 549–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenna E., & Di Novi C (2016). Is caring for older parents detrimental to women’s mental health? The role of the European North-South gradient. Review of Economics of the Household, 14, 745–778. doi: 10.1007/s11150-015-9296-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coe N. B., & Van Houtven C. H (2009). Caring for mom and neglecting yourself? The health effects of caring for an elderly parent. Health Economics, 18, 991–1010. doi: 10.1002/hec.1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Novi C., Jacobs R., & Migheli M (2015). The quality of life of female informal caregivers: From Scandinavia to the Mediterranean Sea. European Journal of Population, 31, 309–333. doi: 10.1007/s10680-014-9336-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Do Y. K., Norton E. C., Stearns S. C., & Van Houtven C. H (2015). Informal care and caregiver’s health. Health Economics, 24, 224–237. doi: 10.1002/hec.3012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukahori R., Sakai T., & Sato K (2015). The effects of incidence of care needs in households on employment, subjective health, and life satisfaction among middle-aged family members. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 62, 518–545. doi: 10.1111/sjpe.12085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goren A., Montgomery W., Kahle-Wrobleski K., Nakamura T., & Ueda K (2016). Impact of caring for persons with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia on caregivers’ health outcomes: Findings from a community based survey in Japan. BMC Geriatrics, 16, 122. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0298-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heger D. (2017). The mental health of children providing care to their elderly parent. Health Economics, 26, 1617–1629. doi: 10.1002/hec.3457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez A. M., & Bigatti S. M (2010). Depression among older Mexican American caregivers. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 50–58. doi: 10.1037/a0015867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong I., Han A., Reistetter T. A., & Simpson A. N (2016). The risk of stroke in spouses of people living with dementia in Korea. International Journal of Stroke, 12, 851–857. doi: 10.1177/1747493016677987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny P., King M. T., & Hall J (2014). The physical functioning and mental health of informal carers: Evidence of care-giving impacts from an Australian population-based cohort. Health & Social Care in the Community, 22, 646–659. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner M. (2009). Long-run labour market and health effects of individual sports activities. Journal of Health Economics, 28, 839–854. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2009.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little R. J., & Rubin D. B (2000). Causal effects in clinical and epidemiological studies via potential outcomes: Concepts and analytical approaches. Annual Review of Public Health, 21, 121–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marasinghe K. M. (2015). Assistive technologies in reducing caregiver burden among informal caregivers of older adults: A systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 11, 353–360. doi: 10.3109/17483107.2015.1087061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., & Altman D. G; PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6, e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortenson W. B., Demers L., Fuhrer M. J., Jutai J. W., Lenker J., & DeRuyter F (2012). How assistive technology use by individuals with disabilities impacts their caregivers: A systematic review of the research evidence. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 91, 984–998. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318269eceb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penning M. J., & Wu Z (2016). Caregiver stress and mental health: Impact of caregiving relationship and gender. The Gerontologist, 56, 1102–1113. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M., & Sörensen S (2003). Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 18, 250–267. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M., & Sörensen S (2007). Correlates of physical health of informal caregivers: A meta-analysis. Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62, P126–P137. doi:10.1093/geronb/62.2.p126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, P., & Rubin, D. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70, 41–55. doi:10.2307/2335942 [Google Scholar]

- Rosso A. L., Lee B. K., Stefanick M. L., Kroenke C. H., Coker L. H., Woods N. F., & Michael Y. L (2015). Caregiving frequency and physical function: The Women’s Health Initiative. Journal of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 70, 210–215. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth D. L., Fredman L., & Haley W. E (2015). Informal caregiving and its impact on health: A reappraisal from population-based studies. The Gerontologist, 55, 309–319. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz H., & Westphal M (2015). Short- and medium-term effects of informal care provision on female caregivers’ health. Journal of Health Economics, 42, 174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R., Newsom J., Mittelmark M., Burton L., Hirsch C., & Jackson S (1997). Health effects of caregiving: The caregiver health effects study: An ancillary study of the Cardiovascular Health Study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 19, 110–116. doi: 10.1007/BF02883327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sörensen S., Pinquart M., & Duberstein P (2002). How effective are interventions with caregivers? An updated meta-analysis. The Gerontologist, 42, 356–372. doi.org/10.1093/geront/42.3.356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staiger D., & Stock J. H (1997). Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Econometrica, 65, 557–586. doi: 10.2307/2171753 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stroka M. A. (2014). The mental and physical burden of caregiving evidence from administrative data. Ruhr Economic Papers, 474, 1–27. Retrieved from https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/93178/1/780314565.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi R., Beaver K., Bouldin E. D., Eugenio E., Zeliadt S. B., Nelson K., … Piette J. D (2014). Characteristics and well-being of informal caregivers: Results from a nationally-representative US survey. Chronic Illness, 10, 167–179. doi: 10.1177/1742395313506947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaliano P. P., Zhang J., & Scanlan J. M (2003). Is caregiving hazardous to one’s physical health? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 946–972. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Zwart P. L., Bakx P., & van Doorslaer E. K. A (2017). Will you still need me, will you still feed me when I’m 64? The health impact of caregiving to one’s spouse. Health Economics, 26(Suppl. 2), 127–138. doi: 10.1002/hec.3542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.