Abstract

Protein chains contain only l-amino acids, with the exception of the achiral glycine, making the chains homochiral. This homochirality is a prerequisite for proper protein folding and, hence, normal cellular function. The importance of d-amino acids as a component of the bacterial cell wall and their roles in neurotransmission in higher eukaryotes are well-established. However, the wider presence and the corresponding physiological roles of these specific amino acid stereoisomers have been appreciated only recently. Therefore, it is expected that enantiomeric fidelity has to be a key component of all of the steps in translation. Cells employ various molecular mechanisms for keeping d-amino acids away from the synthesis of nascent polypeptide chains. The major factors involved in this exclusion are aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRSs), elongation factor thermo-unstable (EF-Tu), the ribosome, and d-aminoacyl-tRNA deacylase (DTD). aaRS, EF-Tu, and the ribosome act as “chiral checkpoints” by preferentially binding to l-amino acids or l-aminoacyl-tRNAs, thereby excluding d-amino acids. Interestingly, DTD, which is conserved across all life forms, performs “chiral proofreading,” as it removes d-amino acids erroneously added to tRNA. Here, we comprehensively review d-amino acids with respect to their occurrence and physiological roles, implications for chiral checkpoints required for translation fidelity, and potential use in synthetic biology.

Keywords: translation, aminoacyl tRNA synthetase, transfer RNA (tRNA), checkpoint control, ribosome, translation elongation factor, stereoselectivity, chirality, D-amino acids, genetic code, proofreading, proteins, amino acid

Introduction

All biological macromolecules consist of building blocks of a particular “handedness” or chirality. Consequently, every biomacromolecule itself becomes chiral in nature, deriving its chirality from its constituent building blocks. The concept of chirality is more than 150 years old and was put forth by Louis Pasteur in 1848 through his seminal work on tartaric acid that paved the way for the discovery of “molecular chirality” (1, 2). The importance of absolute chiral specificity in biological systems strongly came to the fore after the discovery of tragic adverse effects of the drug thalidomide, which was used to treat morning sickness in pregnant women. Thalidomide exists as an enantiomeric mixture of (R)- and (S)-forms, of which the (R)-enantiomer is a sedative and the (S)-enantiomer is teratogenic. Even though the (R)-form of thalidomide was administered, due to spontaneous racemization, it led to about ∼10,000 cases of children being born with abnormal limbs (3, 4).

Macromolecules such as nucleic acids contain only d-ribose, and proteins are made of only l-amino acids with the exception of achiral glycine. It is well-known that functional proteins cannot be made with a mixture of l- and d-amino acids; indeed, it was substantiated that d-amino acids are detrimental for the secondary structure of proteins mainly consisting of l-amino acids (5). It still remains elusive as to why and how only l-amino acids were selected for peptide/protein synthesis during the prebiotic era. The scientific consensus holds that the selection of l-amino acid is merely a chance event. However, in the past few decades, many interesting hypotheses have been put forward to explain this bias of nature. One such explanation is provided by the parity-violating energy difference model (6, 7). It proposes that there exists a small energy difference between enantiomers, which eventually leads to an excess of one type of enantiomer over the other (8). Certain studies have shown that some of the d-amino acids are adsorbed onto one of the crystal surfaces of materials like calcite, thereby allowing only l-amino acids to be used for peptide synthesis (9). Another interesting proposition is that l-amino acids are more compatible with the pre-existing d-ribose RNA, because RNA displays a preference for l-amino acids in a nonenzymatic aminoacylation reaction (10–13). Further evidence for homochirality preference is present in the form of asymmetric amplification in autocatalysis, wherein the product enhances the usage of only one type of enantiomer, thereby eliminating the other (14). If fortuity had not played a role, an orchestration of several complex factors might have led to the origin of homochirality in the living systems, but to what extent each of the physio-chemical factors has contributed to homochirality still needs to be evaluated.

Despite the multitude of selection bias against using d-amino acids for proteins, they have been retained within the biological systems and have been implicated in important biological processes. This clearly indicates that d-amino acid retention has conferred a selective evolutionary advantage to the biological processes they are involved in. Thus, dynamic balancing mechanisms operate to ensure the retention of d-amino acids, which allows the system to take selective advantage and at the same time ensure homochirality of proteins by keeping them at bay from the translational apparatus.

The focus of this review will be on the occurrence of d-amino acids, their importance in different biological processes, and how various components of the translational machinery, such as aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (aaRS),3 elongation factor thermo-unstable (EF-Tu), ribosome, and d-aminoacyl-tRNA deacylase (DTD), are fine-tuned to ensure that d-amino acids are preferentially excluded from the global translation processes. This review brings together the multiple facets of d-amino acids from their presence in different biological systems to their use in synthetic biology approaches by keeping the central focus on how the protein synthesis machinery avoids them.

d-Amino acids in biological systems

d-Amino acids are an important part of biological systems and are involved in many crucial processes. Studies on bacteria half a century ago established d-amino acids as an integral part of the cell wall and several antibiotics (such as valinomycin, actinomycin, vancomycin, and gramicidin) and very recently in the dispersal of biofilm (15–19). The peptides that cross-link the sugar moieties of the peptidoglycan layer contain d-amino acids, which are added by muramyl ligases; MurD and MurF are specific to d-Glu and d-Ala, respectively (20). The presence of d-amino acids makes the peptidoglycan resistant to enzymatic degradation (21, 22), whereas in case of antibiotics, the amino acids are incorporated by nonribosomal peptide synthetases and polyketide synthases (23). The widespread presence of d-amino acids over and above the bacterial cell wall started becoming apparent in the 1980s with the advancements in analytical techniques. By the late 1990s, the universal presence of d-amino acids across all domains of life had been established, and a few examples are presented in Table 1 (18). The occurrence of d-amino acids in archaea was first reported in 1999 (24). However, the significance of the presence of these d-amino acids in archaea is not yet fully deciphered. Surprisingly, d-amino acid oxidase in mammals was discovered by Hans Krebs as early as 1934, although the occurrence of d-amino acids in mammals was not discovered until more than 50 years later (25, 26). These anecdotal observations are to emphasize the presence and the metabolism of d-amino acids and their by-products, which have largely remained unexplored for decades.

Table 1.

Occurrence of d-amino acids in different organisms and their physiological importance

| Amino acid | Organism | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| d-Ala, d-Ser, d-Asp, d-Asn, d-Glu, d-Gln | Bacteria | Cell wall (component of peptidoglycan) | 129 |

| d-Leu, d-Met, d-Phe, d-Tyr | Bacteria | Regulate the formation of peptidoglycan | 130 |

| d-Leu, d-Val, d-Phe | Bacteria | Part of gramicidin and gramicidin S | 131–134 |

| d-Met, d-Leu | Staphylococcus aureus | Biofilm inhibition | 15 |

| d-His | S. aureus | Staphylopine (metallophore: metal-scavenging peptide) | 135 |

| d-Ala, d-Ser, d-Asp | Archaea | Membrane-bound and free form | 24 |

| d-Ala | Phyllomedusa sauvagei (frog) | Dermorphin (part of heptapeptide that binds to opioid receptors) | 136, 137 |

| d-Met | P. sauvagei (frog) | Deltropin (part of heptapeptide that binds to opioid receptors) | 136, 137 |

| d-Trp | Conus radiatus (fish-hunting snail) | Contryphan (part of octapeptide; one of the constituents of venom) | 138 |

| d-Cys | Photuris lucicrescens (firefly) | Part of d-luciferin (natural substrate of luciferase) | 139, 140 |

| d-2,3-diamino-propionic acid, d-Ser | Bombyx mori (insect) | Involved in metamorphosis | 139 |

| d-Ala | Aquatic crustaceans and bivalve mollusks | Involved in maintaining cellular osmolarity | 141 |

| d-Asp | Mammals (nervous system/endocrine system/reproductive system) | Modulates NMDA receptor, Regulates secretion of hormones like vasopressin, oxytocin, prolactin, and testosterone | 26, 33 |

| d-Ser | Mammals (brain) | Co-agonist of NMDA receptor | 29, 30 |

| d-Ser | Arabidopsis thaliana | Crucial for pollen tube development | 36 |

In eukaryotes, d-amino acids play divergent roles (e.g. as nitrogen sources and neurotransmitters), which are primarily confined to the central nervous system. The conservation of d-amino acid racemases, d-amino acid transaminases, and d-amino acid oxidases in all eukaryotes (from yeast to mammals) is suggestive of the importance of d-amino acids. d-Amino acids have been reported in cellular fluids of shellfish and contribute to more than 1% of the cellular pool (27). The skin of amphibians contains an array of peptides with d-amino acids, which are quite similar to the hormones in the higher eukaryotes. The discovery of enkephalin—a pentapeptide involved in the regulation of nociception by virtue of its binding to opioid receptors—in 1975 set the stage for the identification of many such peptides in other animals (28). These peptides bind to different types of opioid receptors with high affinity and usually have a sequence of Tyr-X-Phe-Asp/Glu-Val-Val-Gly (wherein X corresponds to a d-amino acid). In the case of mammals, d-Ser was first identified in 1992 in the frontal brain area of rats and later in the peripheral tissues (29). d-Ser acts as an important neuro-modulator of the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, which is involved in learning, memory, and synaptic junction. d-Ser acts as a co-agonist for the NMDA receptor, and a decrease in its levels has been implicated in pathological conditions such as schizophrenia (30). However, increased levels of d-Ser and d-Ala have been observed in the case of Alzheimer's disease (26, 31, 32). Similarly, high levels of d-Asp in testis offer reproductive advantages and aid in neuroendocrine functions (33, 34). Surprisingly, d-Asp was also found to be incorporated in proteins but was later established to be produced by spontaneous isomerization of its antipode, which increases with aging. Proteins that contain d-Asp are degraded by d-aspartyl endopeptidase (35).

Like all other organisms, the importance of d-amino acids has also been noted in plants. d-Ser plays an important role in the development of the pollen tube in Arabidopsis and tobacco, and d-Ser racemase plays an indispensable role in signal transduction (36). Apart from the d-amino acids synthesized in plants, degradation of the soil bacteria also contributes to the total d-amino acid pools in copious quantities (37, 38). It has also been noted that d-Ala assimilation in wheat plants for use as a nitrogen source was 5-fold higher than that of NO3− (39). Accumulating evidence suggests that some d-amino acids, such as Val, Ile, and Lys, enhance the growth of Arabidopsis (40). From the above accounts, it is clear that irrespective of the life form, all organisms do contain some if not all d-amino acids, which play important physiological roles in their growth and survival. It is therefore important to understand the challenges that d-amino acids pose in maintaining homochirality of the proteome, given their physiological importance, and in a few instances, their concentrations are comparable with that of l-forms (29).

Stereochemistry of amino acids

There are 22 proteinogenic amino acids that are genetically encoded, whereas many other physiologically relevant nonproteinogenic amino acids have been identified in different biological systems. Along with the differences in side chain chemistry, amino acids exist as two stereoisomers (l- and d-), which allows them to perform a multitude of physiological/cellular functions. The stereochemistry of amino acids plays an important role; for instance, d-Ser binds to the NMDA receptor and helps in neurotransmission, whereas l-serine lacks binding to the NMDA receptor (30). Thus, stereochemistry in combination with side chain chemistry plays a critical role in determining the physiological effect and roles of different amino acids.

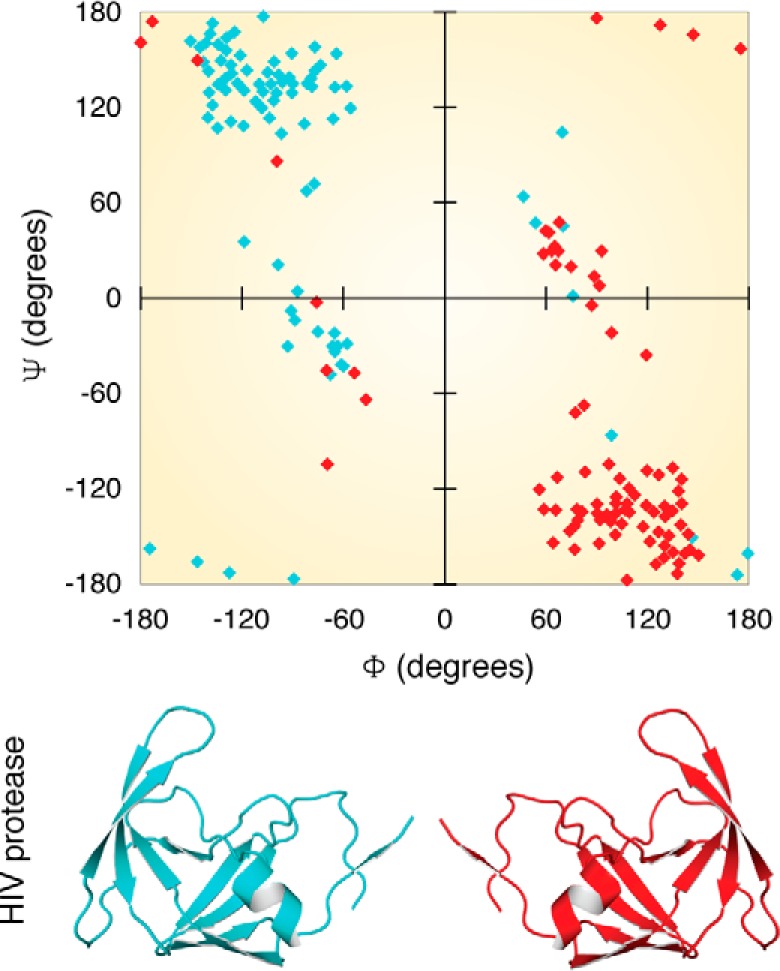

A protein made up of only d-amino acids will be a structural mirror image of its l-amino acid counterpart and will act on substrates with opposite chirality (of the original substrate), as demonstrated using the HIV protease (41). The Ramachandran plot for d-amino acids can be easily generated by simply flipping the sign of ϕ and ψ values (positive values become negative and vice versa). The resultant map will appear inverted at the origin (the first quadrant will flip with the third, and the second quadrant will flip with the fourth) (Fig. 1) (5, 42, 43). d-Amino acids are generally found in small peptides or cyclic peptides. However, a few small peptides such as gramicidin S, which are synthesized using nonribosomal protein synthesis, have a combination of l- and d-amino acids. A peptide that is artificially made of an ld or a dl combination of enantiomers is likely to generate a sharp turn (hairpin or β bend), which in turn contributes to the great compactness of these oligopeptides. The cyclization of these oligopeptides is mainly due to their heterochiral nature (44). Having d-amino acids as a part of oligopeptides renders structural and enzymatic stability, thereby making them indispensable for their respective physiological roles.

Figure 1.

Ramachandran plot for proteins with l- and d-chirality. Shown in blue is the structure of HIV protease (PDB entry 4HVP), and shown in red is the modeled structure of the same protein with inverted chirality. A Ramachandran plot showing the dihedral angles is color-coded according to the cartoon.

The problem of enantiomeric discrimination

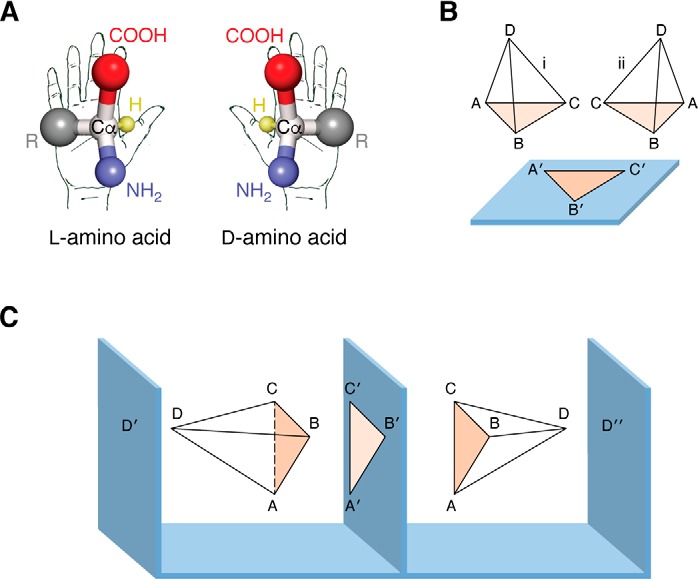

The cellular milieu is a composite mixture of optically active biomolecules, such as amino acids, sugars, and lipids. The molecular basis of many biological processes involves protein-ligand interactions, wherein most proteins are specific to only one stereoisomer of their respective ligand/substrate and inert to its antipode. Very often, both the isomers are present in the system, and proteins encounter the problem of discriminating between these similar yet different molecules. Nevertheless, how proteins achieve such molecular-level chiral discrimination is intriguing. Easson and Stedman (45) and Ogston (46) independently tried to explain the mechanism of this discrimination using the “three-point attachment” (TPA) model. According to the TPA model, proteins recognize the chiral center of the ligand/substrate by specifically attaching/fixing to three distinct atoms/points of the ligand, which would be different for l- and d-isomers (45, 46). This model was validated by pre-existing examples of protein-ligand interactions. Using high-resolution crystal structures of isocitrate dehydrogenase (in complex with l- or d-isocitrate), Mesecar and Koshland (47) highlighted the ambiguity of the TPA model and modified it to a “four-location” model. According to the four-location model, the three complementary sites on the protein that interact with the three sites of the ligand are not sufficient for selection, and rather a fourth constraint in the form of restricted ligand entry or fourth point of contact allows a stricter enantiomer selection (Fig. 2). Thus, the TPA model is a subtype of the four-location model (48). However, it is important to note that these interactions need not be attractive forces only, but can possibly be a combination of both attractive and repulsive forces.

Figure 2.

Models for enantioselectivity of proteins. A, l- and d-stereoisomers of amino acid; Cα represents the chiral center. B, TPA model: A, B, and C are three points on the ligands that interact with A′, B′, and C′ of the protein, and hence only ligand i can bind, and not ii. In this model, the entry/approach of the ligand is assumed to be fixed (i.e. here it is shown from above the binding plane). C, four-location model. As per this model, the fourth site is essential and decides the entry of the ligand. D′ and D″ fix the entry of the ligand. However, D′ and D″ will bind ligands with opposite chirality (adapted from Refs. 46 and 47). This research was originally published in Nature. Ogston, A. G. Interpretation of experiments on metabolic processes, using isotopic tracer elements. Nature. 1948; 162:963. ©Springer Nature; and Nature. Mesecar, A. D., and Koshland, D. E., Jr. A new model for protein stereospecificity. Nature. 2000; 403:614–615. ©Springer Nature.

Maintaining enantiomeric fidelity during translation of the genetic code

The process of information transfer in biological systems is tightly regulated. At the cellular level, replication, transcription, and translation are under strict surveillance to avoid errors. Similarly, the protein synthesis machinery employs checkpoints at every step to avoid infiltration of d-amino acids into the growing polypeptide chain. Transfer of information from the nucleic acid world to the protein world relies on the following molecular factors: aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase, which generates aminoacyl-tRNA (aa-tRNA); EF-Tu, which shuttles the aa-tRNA to the ribosome; the ribosome, which eventually attaches the amino acid to the growing polypeptide chain; and finally DTD, which is involved in decoupling d-amino acid from d-aminoacyl-tRNAs. Each of these factors contributes to the overall enantiomeric fidelity.

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases

aaRSs are one of the ancient housekeeping enzymes that appeared during the early evolution of the translational machinery and act as a bridge between the RNA and protein worlds. aaRSs dictate the genetic code by specifically adding amino acids to the tRNAs (49). In most systems, there are 20 synthetases, which correspond to 20 amino acids (50–52). The accuracy of translation largely depends on the fidelity of these enzymes. Usually, the anticodon-binding domain of an aaRS recognizes the cognate tRNA (using the tRNA anticodon), except for alanyl-tRNA synthetase (AlaRS) and seryl-tRNA synthetase, wherein the acceptor arm G3·U70 and the variable arm are recognized, respectively (53–55). Compared with the amino acid, tRNA is a large molecule and provides a huge area of contact for recognition by the synthetases. Therefore, aaRSs face an enormous challenge of choosing the correct amino acid from a pool of similar-looking amino acids, with differences as small as a methyl group (e.g. Gly and Ala or Ser and Thr), leading to errors. Ten of the 20 synthetases are known to mischarge a wrong (noncognate) amino acid on tRNAs, which can eventually lead to mistranslation, which is abrogated by the editing domains (56–58). These editing domains are either covalently linked to the aminoacylation domain (cis) or exist as an independent module (trans) (59–61). Apart from the generic problem of amino acid mis-selection, there exists the problem of stereochemistry (d- and l- forms) of the amino acids. Because d-amino acids are an inherent part of the cellular milieu across life forms, it becomes imperative for aaRSs to also distinguish the stereochemistry of amino acid.

Amino acid recognition in the active site of the enzyme is achieved by using multiple recognition points. In all of the aaRSs, the amino group is very strongly selected for by means of a conserved polar (Asp/Asn/Glu/Gln) residue. The carbonyl oxygen of the amino acid is fixed in an orientation that is compatible with the activation of the amino acid to form aminoacyl-adenylate, and perhaps this underlying principle is conserved across all synthetases. The specificity factor for the aminoacylation domain is defined by the mode of side-chain picking, which is based on physico-chemical parameters. If the amino group and the carbonyl oxygen are fixed, the orientation of the side chain of a d-amino acid would be opposite to that of an l-amino acid, which forms the basis for steric exclusion by a majority of the synthetases that are meant to activate amino acids with smaller side chains, as indicated by the four-location model. Similarly, if the amino group and the side chain are fixed, then there will be a steric incompatibility of the carboxyl group with the incoming ATP. The third possibility is the fixation of the carboxyl group and the side chain, which makes the amino group incompatible for binding, thereby sterically excluding the d-amino acid. On the contrary, synthetases that activate amino acids with a bigger side chain have relatively large pocket sizes, allowing the accommodation of both l- and d-isomers without a strict steric exclusion (i.e. because of weaker selection/rejection of the fourth position suggested by the four-location model) (Fig. 3). Incidentally, the first synthetase to be identified activating a d-amino acid on a tRNA was tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase (TyrRS) (62, 63). The kinetics of activation and the discrimination capacity of TyrRS put the error rate at 1 in 14 (i.e. 1 of every 14 tRNAs is charged erroneously with d-amino acid). Later studies have shown that TrpRS, PheRS, and AspRS also face the problem of discrimination between l- and d-stereomers (64). These synthetases with weak enantioselectivity can generate d-aa-tRNAs, which can potentially enter the translation machinery, leading to (mis)incorporation of d-amino acids into the growing polypeptide chain, or remain as accumulating dead-end products, depleting the free tRNA pool. Both the misincorporation and depletion scenarios are deleterious to the cell; hence, the cells face the challenge of enantioselectivity, which is taken care of by specific checkpoints downstream of aaRS.

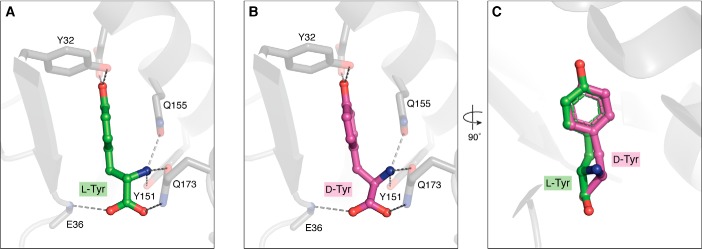

Figure 3.

Amino acid selectivity of tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase. A, l-Tyr captured in the TyrRS amino acid–binding pocket; amino group, carbonyl oxygen, and the side chain hydroxyl groups help in substrate selectivity (PDB entry 1J1U). B, d-Tyr modeled in the TyrRS amino acid–binding pocket. C, overlap of d- and l-Tyr, clearly depicting the mode of amino acid binding and also explaining the weak enantioselectivity of TyrRS.

Elongation factor

Once the tRNAs are aminoacylated by aaRSs, the aa-tRNAs need to be shuttled to the ribosome. The delivery of aa-tRNAs is performed by dedicated proteins, EF-Tu in bacteria and elongation factor-1α (EF-1α) in archaea and eukarya (henceforth, “EF-Tu” will imply and encompass both EF-Tu and EF-1α) (65). This delivery is energy-dependent, wherein the elongation factor is activated by binding to a GTP molecule, which forms a ternary complex with aa-tRNA (EF-Tu·GTP·aa-tRNA); the aa-tRNA release to the ribosome is coupled to the hydrolysis of GTP to GDP (66). The binding of aa-tRNAs to EF-Tu is optimal, such that it is bound neither very strongly nor loosely to avoid problems in the delivery to the ribosome. A stronger binding might hinder effective ribosomal delivery, and if bound loosely, the substrate will dissociate before reaching the target site (i.e. the ribosome). Structural and biochemical studies have shown that EF-Tu binds to the tRNA, whereas the amino acid is accommodated in the amino acid–binding site, which is large enough to accommodate amino acid as big as tryptophan (67). The mechanism by which EF-Tu achieves optimal binding with such a huge variation in amino acid side chains is an interesting puzzle, which was explained using the concept of “thermodynamic compensation” by Uhlenbeck and co-workers (68). They have shown that the binding affinity of the smaller amino acids is weak, which is compensated by a relatively stronger binding to the tRNA, and in the case of larger amino acids, the stronger binding affinity for the side chain is compensated by a relatively weaker affinity for tRNA. The compensation mechanisms ensure that the overall binding affinities of all of the different aa-tRNAs to EF-Tu are similar and fall within a narrow range (0.37–7 nm) of Kd values (69).

It should be clear from the compensation mechanism that the binding of d-amino acids in the amino acid–binding pocket of the EF-Tu will decide its ability to participate in peptide synthesis. The affinity of d-aa-tRNAs to EF-Tu is found to be 25-fold less when compared with its l-aa-tRNAs (70, 71). Remarkably, the 25-fold difference in binding affinity is sufficient to discriminate the stereoisomers, and thus EF-Tu shows a biased preference for the l-amino acids. The difference in affinity for the stereoisomers is likely to arise from the ability of the EF-Tu to strongly select the amino acid by specifically picking up the amino group and the carbonyl oxygen, thereby restricting the orientation of the side chain (Fig. 4). It should also be noted that differences in binding affinities of amino acids and tRNAs aid in resampling of weakly bound mischarged aa-tRNAs, which are eventually corrected by the proofreading domains of aaRSs, thus contributing to the overall fidelity of translation (72).

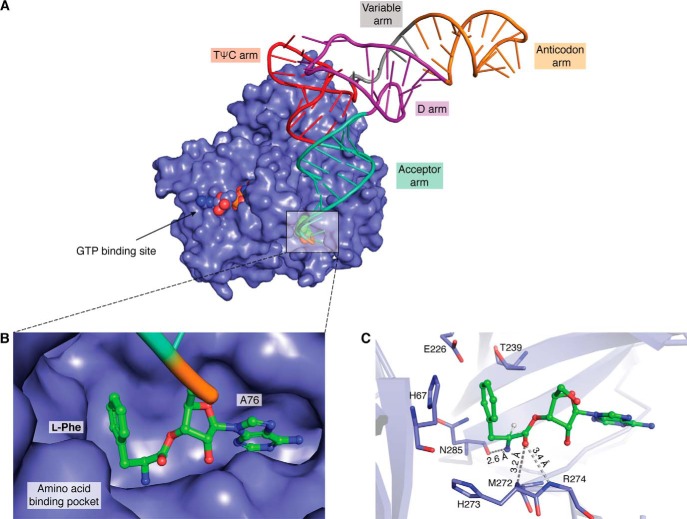

Figure 4.

Elongation factor in complex with l-Phe-tRNAPhe. A, crystal structure of a ternary complex, EF-Tu (surface representation in blue), GTP (shown as spheres in the GTP-binding site), and l-Phe-tRNAPhe (tRNA shown in a wire and stick representation with amino acids as spheres) (PDB entry 1TTT). B, zoomed in view of an amino acid (of l-Phe-tRNAPhe) bound in the amino acid–binding pocket of EF-Tu. C, stick representation of the amino acid–binding pocket showing key interactions with the ligand (l-Phe).

Ribosome

Ribosomes are the information-decoding centers, wherein amino acids are coupled together by a peptide bond in a specific order depending on the mRNA sequence and aa-tRNAs act as the substrates (66, 73–82). Before the release of aa-tRNA from EF-Tu, the ribosome checks the pairing of codon (in mRNA) and anti-codon (of the tRNA), in the case of a cognate pairing, following which hydrolysis of GTP (EF-Tu–bound) to GDP is induced, thus leading to the release of aa-tRNA in to the A-site (83, 84). Once the aa-tRNA is accommodated in the A-site, the amino group of the amino acid mounts a nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl carbon of the peptidyl-tRNA (pt-tRNA), which is lodged at the P-site. As a result, a peptide bond is formed between the A-site amino acid (of aa-tRNA) and the P-site peptidyl moiety (of the pt-tRNA), with a concomitant deacylation of tRNA and the translocation of the mRNA by a codon, thereby preparing the ribosome for the next round of polypeptide elongation (85, 86). The newly formed peptidyl moiety of pt-tRNA will now have one amino acid more than the earlier pt-tRNA (87, 88). In this plethora of events of peptide synthesis, how d-aa-tRNAs are treated by the ribosome is of specific interest and is essential for tweaking the ribosome for making noncanonical peptides.

Since the past decade, researchers have been trying to exploit the power of the ribosome to create novel polymers and also to understand the mechanistic basis of protein folding using unnatural amino acids. In the process, the use of d-amino acids to generate variations in peptides has led to the understanding of how d-aa-tRNAs are treated by the ribosomal machinery. One of the early studies includes the demonstration that d-amino acids, if charged on initiator tRNA, can efficiently initiate peptide synthesis. All d-amino acids can participate in the translation initiation process but with variable efficiencies, with d-Tyr, d-Phe, and d-Cys being the maximum >25% (89). However, methionyl-tRNA synthetase does not mischarge d-Met; hence, the possibility of a d-amino acid acting as the initiator amino acid is not physiologically relevant but nonetheless opens up new scope for making N-terminal protease-resistant peptides. Apart from initiation, the effect of d-amino acids during elongation has also been well-studied. One of the early studies has shown that d-Tyr-tRNA is a poor substrate for peptide elongation, as the number of GTPs hydrolyzed for the formation of one dipeptide is 1.4 and 4 molecules per l- and d-Tyr-tRNA, respectively. Moreover, the rate of peptide bond formation with d-Tyr-tRNA is ∼30-fold slower when compared with that with l-Tyr-tRNA (71, 90). However, these studies were limited to only d-Tyr, and later on with the advent of flexizyme (a synthetic ribozyme-based aminoacylation system), the effect of all of the 19 d-amino acids on the elongation step was studied (91). Every amino acid varies in its ability to get incorporated into the growing polypeptide chain. Based on this property, amino acids are divided into three groups, Group I (Ala, Ser, Cys, Met, Thr, His, Phe, and Tyr), Group II (Asn, Gln, Val, and Leu), and Group III (Arg, Lys, Asp, Glu, Ile, Trp, and Pro). These three groups have respective elongation efficiencies of >40, 10–40% and no detectable incorporation (91). However, the consecutive addition of d-amino acid (including a few nonproteinogenic amino acids (nPAAs)) by using a natural system is still a challenge and clearly establishes that ribosome acts as a checkpoint for the incorporation of d-amino acids.

The mechanistic basis of why elongation using d-amino acids is very slow and also how the ribosomal machinery prevents the infiltration of d-amino acids was recently addressed through crystal structures of the ribosome in complex with 73ACCA76 (which mimics the 3′ CCA terminal of tRNA) linked to d-Phe with an amide bond and with puromycin linked to 74CC75, an l-aa-tRNA analogue (92). Both of the substrates were captured in the A-site of the ribosome, which mimics the prepeptide bond conformation along with a free initiator tRNA in the P-site (Fig. 5). The tRNA is perfectly oriented in place with the CCA end of tRNA making the canonical interaction with the G2553 nucleotide of the A loop of 23S rRNA, which is essential for proper positioning of the substrate in the A-site cleft (86, 93). The amino acid side chain component is accommodated in the large A-site cleft, which is a highly conserved feature across different ribosomes from different forms of life. However, what is strikingly different is the orientation of the amino group of the d-amino acid compared with that of the l-analogue, which is lodged in the A-site. The amino group of aa-tRNA (accommodated in the A-site) initiates a nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl carbon of the pt-tRNA; prior to this, the amino group makes an interaction with 2′-OH of the A76 nucleotide of pt-tRNA, which is essential for optimal positioning of the substrates for nucleophilic attack on carbonyl carbon (pt-tRNA) and subsequent shuttling of protons (93). In the case of d-amino acid–bound structure, the distance between the amino group and the 2′-OH is greater than 3.5 Å, which is unfavorable for the formation of a peptide bond. These differences in orientation are mainly due to the steric clash of the amino acid with the universally conserved U2506 residue of the peptidyltransferase center (PTC). Thus, U2506 acts as a chiral-discriminating nucleotide by not allowing optimal orientation of even the smallest d-amino acid in the PTC, which is beautifully exemplified in the form of slow peptide bond formation rates. The slow peptide bond formation rates can potentially allow extremely rare incorporation of d-amino acids at random locations; however, further probing is required to understand why the incorporation of consecutive d-amino acids is a challenge.

Figure 5.

Chiral discrimination at the A-site of the ribosome. Shown is the structure of the ribosome showing the A-site in complex with the aa-tRNA analog and the P-site with peptidyl-tRNA (taken from PDB entry 1VY4). The U2506 nucleotide of the 23S rRNA acts as a chiral discriminatory residue by allowing l-aa-tRNA to optimally orient for peptide bond formation but not the d-aa-tRNA. A, complex (PDB entry 6N9E) with l-aa-tRNA analog (CC-puromycin; for the sake of clarity, the hydroxy methyl of methyltyrosine is removed) shown in magenta. B, complex (PDB entry 6N9F) of d-aa-tRNA (ACCA-d-Phe) shown in yellow.

d-Aminoacyl-tRNA deacylase

DTD was the first trans-editing factor to be discovered way back in 1967, when its biochemical activity on d-Tyr-tRNATyr and d-Phe-tRNAPhe was demonstrated using crude extracts of bacteria (94). Later studies have shown that DTD can act on multiple d-aa-tRNAs irrespective of the amino acid side chain (64, 95). Thus, DTD was demonstrated to proofread the erroneously generated d-aa-tRNAs by aaRSs (62–64, 94, 96). In contrast to EF-Tu and the ribosome, which show a preference for l-aa-tRNA binding, DTD specifically binds to d-aa-tRNAs and removes the d-amino acids from the tRNA, thus allowing the tRNAs to recycle back for protein synthesis (70, 71, 97). DTD, therefore, aids in the process of maintaining/enforcing proteome homochirality and thus in proteome homeostasis. The physiological relevance of DTD was demonstrated in Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, wherein DTD knockout strains were found to be sensitive to d-amino acids, and the same was observed in the case of DTD knockdown HeLa cell lines. Interestingly, the expression of DTD in human tissues directly correlates with the levels of d-amino acids present (98).

DTD is conserved across all bacteria and eukaryotes but is absent in archaea. Surprisingly, a DTD-like fold is found as the N-terminal domain (NTD) of the archaeal ThrRS, which proofreads l-Ser mischarged on tRNAThr (99, 100). However, the sequence identity between E. coli DTD and Pyrococcus abyssi NTD is ∼14%. It is quite interesting to note that NTD has no sequence or structural homology with the canonical class II editing domain of bacterial and eukaryotic ThrRS. The structural homology between DTD and NTD has led to a model for the perpetuation of homochirality. During early evolution, a DTD-like d-amino acid–editing module might have been coupled to synthetases (which may have poor chiral discrimination capacity, as explained earlier) either covalently and/or functionally to avoid the infiltration of d-amino acids into proteins. Later on, in bacteria and eukaryotes, this activity was retained in the form of a DTD, whereas in archaea, it remained coupled to ThrRS and fine-tuned to deacylate l-Ser-tRNAThr. Notably, in the case of archaea and cyanobacteria, both of which lack DTD, different d-aa-tRNA–editing modules exist, in the form of DTD2 and DTD3, respectively (101, 102). DTD2 and DTD3 are functional homologs of DTD but share no sequence or structural homology either with DTD or between themselves. It is intriguing to note here that plants have both DTD and DTD2; the physiological relevance of this functional redundancy is yet to be deciphered. The universality of DTD function emphasizes the essentiality of chiral proofreading in all three domains of life.

Biochemical studies have shown that DTD proofreads multiple d-aa-tRNAs but does not act on even the smallest l-amino acid (l-Ala). The structural basis for this absolute configuration specificity was unraveled by solving the co-crystal structure of DTD with a substrate analog, namely d-tyrosyl-3′-aminoadenosine (d-Tyr3AA) (103). The crystal structure revealed no side chain recognition of d-Tyr (d-Tyr3AA) beyond the β-carbon and was observed to be projecting out of the active site, which readily explains why the activity of DTD is side chain-independent (Fig. 6). Further structural analysis led to the identification of an invariant cross-subunit Gly-cisPro motif (GP-motif) that imparted stereospecificity to the enzyme. The cis conformation of the GP-motif orients its carbonyl oxygen atoms parallel and projecting into the active site, which captures the amino and β-carbon of the substrate (d-aa-tRNA) and hence is proposed to be involved in d-chiral selection. An intricate analysis of the DTD active site by systematic modeling of a methyl group, an amino group, and a hydrogen atom attached to the chiral carbon has led to the proposition that DTD is an l-chiral rejection module (104). The GP-motif essentially acts as a “chiral selectivity filter” and does not allow even the smallest l-amino acid to be accommodated in the active site.

Figure 6.

Enantioselectivity mechanism of DTD. A, crystal structure of DTD in complex with d-Tyr3AA (PDB entry 4NBI). The active site is at the dimeric interface (each monomer is colored differently). The ligand is shown in magenta, and the GP-motif is shown in green sticks. B, d-Tyr in the active site; the side chain projects out of the pocket, and the GP-motif forms the base. C, l-Tyr modeled in the active site, clearly showing the side chain clash with the GP-motif.

The Gly-cisPro motif in the active site of DTD, while ensuring l-amino acid rejection, results in achiral glycine binding. The structure of DTD in complex with the glycyl-3′-aminoadenosine (Gly3AA) in combination with biochemical activity of DTD on Gly-tRNAGly has led to the understanding that binding of glycine is a happenstance. This “misediting paradox” of DTD on Gly-tRNAGly is resolved by EF-Tu in the cellular scenario, which confers protection to the achiral substrate. Nevertheless, this protection is not very strong, and even a ∼4 -fold increase of DTD in in vitro biochemical assays could completely overcome EF-Tu's protection of Gly-tRNAGly. This was substantiated in vivo, wherein in E. coli, overexpression of DTD was shown to cause misediting of Gly-tRNAGly, manifesting itself as cellular toxicity. DTD levels in the cells are kept low, and hence it acts only on d-aa-tRNAs and not on Gly-tRNAGly, as is evident from the expression profile of DTD in various databases (SGD, Flybase, etc.). However, the activity of DTD on Gly has been recently shown to be not a design flaw but instead advantageous, as it can proofread Gly-tRNAAla, a misacylation product of AlaRS. Notably, unlike in the case of cognate Gly-tRNAGly, EF-Tu does not offer any protection to the noncognate Gly-tRNAAla, and the discriminator (N73) base of the tRNA has been shown to play a crucial role in this differential DTD activity (105, 106). Bacterial DTD has robust activity on noncognate Gly-tRNAAla and 1000-fold less on cognate Gly-tRNAGly, of which a 100-fold difference is mainly attributed to the discriminator base (N73) of tRNA. Very recently, a newer variant of DTD has been identified and named Animalia-specific tRNA deacylase (ATD). Interestingly, the GP-motif is in trans conformation, owing to which, ATD can act on tRNAs charged with smaller l-amino acids (e.g. l-Ala), suggesting the critical role of the Gly-cisPro motif of DTD in l-chiral rejection (107).

With respect to catalysis, mutations in the conserved active-site residues of DTD do not affect its deacylation activity. Similar to NTD, the side chains have no role in either substrate specificity or catalysis; instead, the 2′-OH of A76 (of tRNA) was shown to be indispensable for its activity (108, 109). Taking cues from NTD and on the basis of structure, a similar RNA-based substrate-assisted catalysis mechanism was proposed for DTD. The role of 2′-OH (of A76) in catalysis was convincingly shown using modified tRNAs that harbored 2′-deoxy or 2′-deoxyfluoro at the 3′-terminal A76 position; the use of these modified substrates completely abrogates DTD's activity (104, 110). With RNA playing a central role in catalysis as well as in substrate specificity, DTD has been proposed to be of primordial origin and must have played a pivotal role in maintaining “enantiomeric fidelity” starting from the early evolution of translational machinery.

Synthetic biology approach for introducing d-amino acids into polypeptide chains

Incorporation of d-amino acids into the polypeptide chain enhances stability, alters its physicochemical properties, and avoids degradation by proteases, and therefore such polypeptide chain could serve as better antimicrobial peptides. Keeping in view the upcoming challenges posed by multidrug-resistant bacteria, the advent of antimicrobial peptides provides a plethora of polymers with novel characteristics that can be employed against these resistant bacteria. Due to the presence of multiple reactive groups, the chemical synthesis of peptides involves complex protection and deprotection steps, which decrease the overall yield of the product (111). On the other hand, enzymatic synthesis of peptides is specific, involves a lesser number of steps, easy product recovery, and does not involve the use of any toxic compounds or solvents. The challenges in generating these peptides are enormous and include overcoming the l-amino acid bias of the entire translation system, guarded by aaRS, EF-Tu, DTD, and the ribosome.

One of the initial challenges is to generate a system that can allow the addition of any nonproteinogenic amino acid (d-amino acid, N-alkyl-amino acid, β-amino acids, or any variation on the side chain) onto the tRNA. In the context of d-amino acids, only four synthetases (TyrRS, TrpRS, PheRS, and AspRS) have been demonstrated to charge a d-stereoisomer on tRNA. Using RNA-based selection/evolution approaches, a random scaffold of an ∼45-nucleotide flexizyme with the ability to aminoacylate tRNA was first identified and named FX3 (112). Flexizyme is a ribozyme that is versatile/promiscuous in adding any amino acid to any tRNA. The only prerequisite for the flexizyme is that the amino acid should be coupled to a leaving group, such as cyano methyl esters or dinitro benzyl esters or chlorobenzyl thioesters (113). The introduction of flexizyme along with the purified recombinant protein–based translation system has led to a major explosion in trials to incorporate nPAAs (114).

The second major hurdle in incorporating d-amino acids into growing polypeptide chains is the low binding affinities of EF-Tu toward d-aa-tRNAs. The reduced binding is mainly due to the amino acid component, which has poor compatibility with the EF-Tu amino acid–binding site (68, 115). The low binding affinity of tRNA can be overcome by altering the tRNA determinants (TΨC arm), which are responsible for EF-Tu binding, or by the use of a tRNA scaffold (tRNAGly/Gln) that has higher affinity. Both strategies have been employed and shown to enhance the binding of d-aa-tRNA to EF-Tu. A more recent and interesting attempt was made using elongation factor P (EF-P), which enhances the peptide formation between two consecutive proline residues which is otherwise a very slow process (116, 117). EF-P is a specialized elongation factor that binds to the d-arm of tRNAPro and promotes peptide bond formation (118). A chimeric tRNA that has determinants for strong EF-Tu binding in the T-arm (tRNAGlu) and also for EF-P binding in the d-arm (tRNAPro) was loaded with d-amino acids and used for in vitro translation. This led to a ∼5-fold increase in d-amino acid incorporation and could also introduce five consecutive d-amino acids into the nascent peptide (119). Very recently, a macrocyclic peptide made of 10 successive d-amino acids was synthesized using the same system (120).

The ribosome plays a crucial role in a successful generation of peptides using nPAAs. Earlier studies have clearly shown that the peptide bond formation is slow due to the inappropriate positioning of the nucleophile (aa-tRNA) and the electrophile (pt-tRNA), which is lodged at the P-site. To overcome this incompatibility of PTC, mutations in the domain V of the 23S rRNA were introduced using random mutagenesis, and these were examined for their ability to use d-aa-tRNAs for translation. The WT ribosome introduces d-Phe and d-Met into the dihydrofolate reductase protein with an efficiency of 5.2 and 9.6%, respectively, compared with the incorporation of l-Phe and l-Met. One of the mutants of ribosome had higher efficiency of incorporating d-Phe (22%) and d-Met (49%). These mutations include 2447GAUA2450 to 2447UGGC2450, which is close to the PTC, and 2457UGAUAC2462 to 2457GCUGAU2462, which is close to the A-site; however, the mechanistic details are yet to be understood (121, 122). The structure of the ribosome in complex with d-aa-tRNA analog has revealed that an invariant U2506 does not allow optimal binding of the d-amino acid in the A-site and thus acts as an important chiral gating residue (92). Mutating U2506 would be the obvious choice to reduce the chiral specificity of the ribosome, but mutation of this particular residue abolishes the peptide bond formation activity by >5000-fold (87). Currently, the mechanistic understanding of the ribosome PTC with respect to chiral selection is limited and needs further structural and biochemical probing for further engineering.

Overall, the synthetic biology approaches of making an alternative to aaRSs, tweaking the tRNA to improve the binding to EF-Tu, and also introducing mutations in the ribosome (23S rRNA) PTC have improved the efficiency of d-amino acid incorporation. Despite the impressive progress in making noncanonical peptides using the translational machinery, problems such as contamination with l-amino acids and the yield are of concern and are currently being investigated.

Conclusions

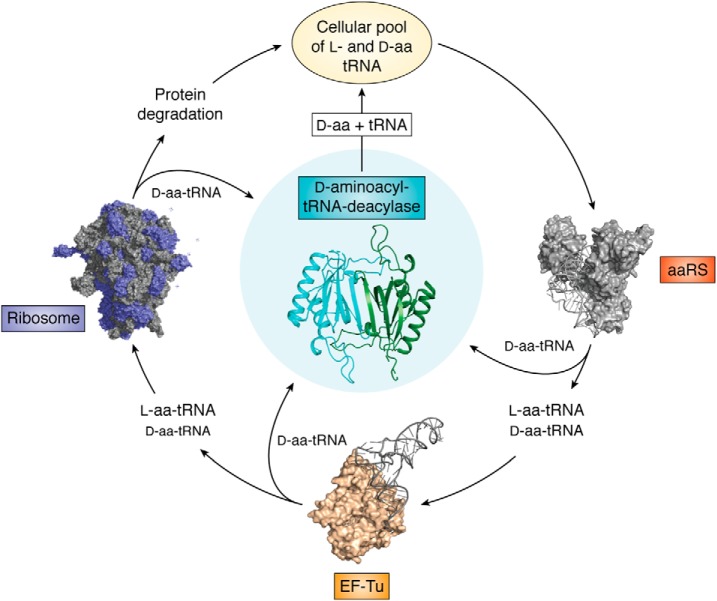

During early evolution, the protein world selected l-chirality. What favored the selection of l-amino acids over d-amino acids and led to biological systems fine-tuning the protein synthesis machinery to use only l-amino acids is still debated. However, it would be wrong to imagine that d-amino acids have been eliminated from the system; instead, d-amino acid pools have been exploited to perform very important physiological roles, such as maintaining cell wall integrity and utilization as a nitrogen source, as neurotransmitters, and as defense molecules. In the wake of the important roles assigned to d-amino acids, their coexistence with l-amino acids becomes inevitable. Thus, translation machinery has employed multiple checkpoints to ensure the homochirality of the proteome. These checkpoints mainly include aaRSs, EF-Tu, ribosome, and DTD, of which the first three have a strong but not exclusive preference for l-amino acid/l-aa-tRNAs and hence preclude d-amino acid entry into the growing polypeptide chain. Unlike other factors that discriminate based on binding affinity, DTD enzymatically clears the d-aa-tRNAs from the cellular pool, thereby continuously guarding the translation machinery against the threat of d-amino acids and also recycling the tRNAs for faithful translation (Fig. 7). The conservation of DTD-like fold and DTD function across domains of life and its primordial mode of RNA-dependent action suggest the importance of chiral proofreading. Recent attempts to make novel peptides containing d-amino acids have led to a major understanding of how tRNA, EF-Tu, and ribosome can be tweaked to improve the in vitro translation of d-amino acids. Accumulating evidence from the past has shown that subtle changes in editing activity lead to pathological conditions such as neurodegeneration, ataxia, and mitochondrial encephalopathies (123, 124). The atomic details of many of the editing processes are still unknown and are essential to understand the physiological impact they create. Very recently, it has been seen that errors during stress conditions are tightly regulated, which in turn provides an advantage to the respective system (125–128). In this context, cellular perturbances in the d-amino acid discrimination potential and their relevance in disease manifestation remain to be explored.

Figure 7.

Chiral checkpoints for maintaining the enantiomeric fidelity of proteome. The translation apparatus, which includes aaRS, EF-Tu, and ribosome, has a preference for l-amino acids/l-aa-tRNAs but is porous to d-amino acids/d-aa-tRNAs as well. DTD specifically decouples d-aa-tRNAs and helps to recycle the tRNAs, and it also aids in maintaining the homochirality of cellular proteome.

Author contributions

S. K. K., S. P. K., and R. S. conceptualization; S. K. K., S. P. K., and R. S. formal analysis; S. K. K., S. P. K., and R. S. investigation; S. K. K., S. P. K., and R. S. methodology; S. K. K. and R. S. writing-original draft; S. K. K., S. P. K., and R. S. writing-review and editing; R. S. resources; R. S. supervision; R. S. funding acquisition; R. S. project administration.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- aaRS

- aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase

- EF-Tu

- elongation factor thermo-unstable

- ATD

- Animalia-specific tRNA deacylase

- DTD

- d-aminoacyl-tRNA deacylase

- NMDA

- N-methyl-d-aspartate

- TPA

- three-point attachment

- aa-tRNA

- aminoacyl-tRNA

- AlaRS

- TyrRS, AspRS, and TrpRS, alanyl-, tyrosyl-, aspartyl-, and tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase, respectively

- EF-1α

- elongation factor-1α

- pt-tRNA

- peptidyl-tRNA

- nPAA

- nonproteinogenic amino acid

- PTC

- peptidyltransferase center

- NTD

- N-terminal domain

- d-Tyr3AA

- d-tyrosyl-3′-aminoadenosine

- GP-motif

- Gly-cisPro motif

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank.

References

- 1. Gal J. (2017) Pasteur and the art of chirality. Nat. Chem. 9, 604–605 10.1038/nchem.2790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pasteur L. (1848) Recherches sur les Relations qui peuvent Exister entre la Forme Cristalline, la Composition Chimique et le Sens de la Polarisation Rotatoire. Annales de Chimie et de Physique 24, 422–459 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kim J. H., and Scialli A. R. (2011) Thalidomide: the tragedy of birth defects and the effective treatment of disease. Toxicol. Sci. 122, 1–6 10.1093/toxsci/kfr088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eriksson T., Björkman S., Roth B., Fyge A., and Höglund P. (1995) Stereospecific determination, chiral inversion in vitro and pharmacokinetics in humans of the enantiomers of thalidomide. Chirality 7, 44–52 10.1002/chir.530070109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mahalakshmi R., and Balaram P. (2007) d-Amino Acids: A New Frontier in Amino Acid and Protein Research, pp. 415–430, Nova Science Publishers, Inc., Hauppauge, NY [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tranter G. E. (1987) Parity violation and the origins of biomolecular handedness. Biosystems 20, 37–48 10.1016/0303-2647(87)90018-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Szabó-Nagy A., and Keszthelyi L. (1999) Demonstration of the parity-violating energy difference between enantiomers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 4252–4255 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Berger R., and Quack M. (2000) Electroweak quantum chemistry of alanine: parity violation in gas and condensed phases. Chemphyschem 1, 57–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cintas P. (2002) Chirality of living systems: a helping hand from crystals and oligopeptides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 41, 1139–1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Martyn Bailey J. (1998) RNA-directed amino acid homochirality. FASEB J. 12, 503–507 10.1096/fasebj.12.6.503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tamura K. (2008) Origin of amino acid homochirality: relationship with the RNA world and origin of tRNA aminoacylation. Biosystems 92, 91–98 10.1016/j.biosystems.2007.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tamura K., and Schimmel P. (2004) Chiral-selective aminoacylation of an RNA minihelix. Science 305, 1253 10.1126/science.1099141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tamura K., and Schimmel P. R. (2006) Chiral-selective aminoacylation of an RNA minihelix: mechanistic features and chiral suppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 13750–13752 10.1073/pnas.0606070103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Blackmond D. G. (2004) Asymmetric autocatalysis and its implications for the origin of homochirality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 5732–5736 10.1073/pnas.0308363101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hochbaum A. I., Kolodkin-Gal I., Foulston L., Kolter R., Aizenberg J., and Losick R. (2011) Inhibitory effects of d-amino acids on Staphylococcus aureus biofilm development. J. Bacteriol. 193, 5616–5622 10.1128/JB.05534-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sanchez Z., Tani A., and Kimbara K. (2013) Extensive reduction of cell viability and enhanced matrix production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 flow biofilms treated with a d-amino acid mixture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 1396–1399 10.1128/AEM.02911-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bodanszky M., and Perlman D. (1969) Peptide antibiotics. Science 163, 352–358 10.1126/science.163.3865.352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fujii N., and Saito T. (2004) Homochirality and life. Chem. Rec. 4, 267–278 10.1002/tcr.20020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Osborn M. J. (1969) Structure and biosynthesis of the bacterial cell wall. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 38, 501–538 10.1146/annurev.bi.38.070169.002441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Šink R., Barreteau H., Patin D., Mengin-Lecreulx D., Gobec S., and Blanot D. (2013) MurD enzymes: some recent developments. Biomol. Concepts 4, 539–556 10.1515/bmc-2013-0024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cava F., Lam H., de Pedro M. A., and Waldor M. K. (2011) Emerging knowledge of regulatory roles of d-amino acids in bacteria. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 68, 817–831 10.1007/s00018-010-0571-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Genchi G. (2017) An overview on d-amino acids. Amino Acids 49, 1521–1533 10.1007/s00726-017-2459-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Walsh C. T., Chen H., Keating T. A., Hubbard B. K., Losey H. C., Luo L., Marshall C. G., Miller D. A., and Patel H. M. (2001) Tailoring enzymes that modify nonribosomal peptides during and after chain elongation on NRPS assembly lines. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 5, 525–534 10.1016/S1367-5931(00)00235-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nagata Y., Tanaka K., Iida T., Kera Y., Yamada R., Nakajima Y., Fujiwara T., Fukumori Y., Yamanaka T., Koga Y., Tsuji S., and Kawaguchi-Nagata K. (1999) Occurrence of d-amino acids in a few archaea and dehydrogenase activities in hyperthermophile Pyrobaculum islandicum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1435, 160–166 10.1016/S0167-4838(99)00208-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Krebs H. A. (1935) Metabolism of amino-acids: deamination of amino-acids. Biochem. J. 29, 1620–1644 10.1042/bj0291620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Roher A. E., Lowenson J. D., Clarke S., Wolkow C., Wang R., Cotter R. J., Reardon I. M., Zürcher-Neely H. A., Heinrikson R. L., and Ball M. J. (1993) Structural alterations in the peptide backbone of β-amyloid core protein may account for its deposition and stability in Alzheimer's disease. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 3072–3083 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Preston R. L. (1987) Occurrence of d-amino acids in higher organisms: a survey of the distribution of d-amino acids in marine invertebrates. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 87, 55–62 10.1016/0305-0491(87)90470-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hughes J., Smith T. W., Kosterlitz H. W., Fothergill L. A., Morgan B. A., and Morris H. R. (1975) Identification of two related pentapeptides from the brain with potent opiate agonist activity. Nature 258, 577–580 10.1038/258577a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hashimoto A., Nishikawa T., Hayashi T., Fujii N., Harada K., Oka T., and Takahashi K. (1992) The presence of free d-serine in rat brain. FEBS Lett. 296, 33–36 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80397-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mothet J. P., Parent A. T., Wolosker H., Brady R. O. Jr., Linden D. J., Ferris C. D., Rogawski M. A., and Snyder S. H. (2000) d-Serine is an endogenous ligand for the glycine site of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 4926–4931 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fujii N., Kaji Y., and Fujii N. (2011) d-Amino acids in aged proteins: analysis and biological relevance. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 879, 3141–3147 10.1016/j.jchromb.2011.05.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Madeira C., Lourenco M. V., Vargas-Lopes C., Suemoto C. K., Brandão C. O., Reis T., Leite R. E., Laks J., Jacob-Filho W., Pasqualucci C. A., Grinberg L. T., Ferreira S. T., and Panizzutti R. (2015) d-Serine levels in Alzheimer's disease: implications for novel biomarker development. Transl. Psychiatry 5, e561 10.1038/tp.2015.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ito T., Hayashida M., Kobayashi S., Muto N., Hayashi A., Yoshimura T., and Mori H. (2016) Serine racemase is involved in d-aspartate biosynthesis. J. Biochem. 160, 345–353 10.1093/jb/mvw043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sakai K., Homma H., Lee J. A., Fukushima T., Santa T., Tashiro K., Iwatsubo T., and Imai K. (1998) Localization of d-aspartic acid in elongate spermatids in rat testis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 351, 96–105 10.1006/abbi.1997.0539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Katane M., and Homma H. (2011) d-Aspartate—an important bioactive substance in mammals: a review from an analytical and biological point of view. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 879, 3108–3121 10.1016/j.jchromb.2011.03.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Michard E., Lima P. T., Borges F., Silva A. C., Portes M. T., Carvalho J. E., Gilliham M., Liu L. H., Obermeyer G., and Feijó J. A. (2011) Glutamate receptor-like genes form Ca2+ channels in pollen tubes and are regulated by pistil d-serine. Science 332, 434–437 10.1126/science.1201101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Aldag R. W., and Young J. L. (1970) d-Amino acids in soils. I. Uptake and metabolism by seedling maize and ryegrass. Agron. J. 62, 184–189 10.2134/agronj1970.00021962006200020002x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vranova V., Zahradnickova H., Janous D., Skene K. R., Matharu A. S., Rejsek K., and Formanek P. (2012) The significance of d-amino acids in soil, fate and utilization by microbes and plants: review and identification of knowledge gap. Plant Soil 354, 21–39 10.1007/s11104-011-1059-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hill P. W., Quilliam R. S., DeLuca T. H., Farrar J., Farrell M., Roberts P., Newsham K. K., Hopkins D. W., Bardgett R. D., and Jones D. L. (2011) Acquisition and assimilation of nitrogen as peptide-bound and d-enantiomers of amino acids by wheat. PLoS One 6, e19220 10.1371/journal.pone.0019220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Forsum O., Svennerstam H., Ganeteg U., and Näsholm T. (2008) Capacities and constraints of amino acid utilization in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 179, 1058–1069 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02546.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Milton R. C., Milton S. C., and Kent S. B. (1992) Total chemical synthesis of a d-enzyme: the enantiomers of HIV-1 protease show reciprocal chiral substrate specificity [corrected]. Science 256, 1445–1448 10.1126/science.1604320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ramakrishnan C. (2001) Ramachandran and his map. Resonance 6, 48–56 10.1007/BF02836967 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ramakrishnan C., and Ramachandran G. N. (1965) Stereochemical criteria for polypeptide and protein chain conformations. II. Allowed conformations for a pair of peptide units. Biophys. J. 5, 909–933 10.1016/S0006-3495(65)86759-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chandrasekaran R., Lakshminarayanan A. V., Pandya U. V., and Ramachandran G. N. (1973) Conformation of the LL and LD hairpin bends with internal hydrogen bonds in proteins and peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 303, 14–27 10.1016/0005-2795(73)90143-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Easson L. H., and Stedman E. (1933) Studies on the relationship between chemical constitution and physiological action: molecular dissymmetry and physiological activity. Biochem. J. 27, 1257–1266 10.1042/bj0271257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ogston A. G. (1948) Interpretation of experiments on metabolic processes, using isotopic tracer elements. Nature 162, 963 10.1038/162963b0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mesecar A. D., and Koshland D. E. Jr. (2000) A new model for protein stereospecificity. Nature 403, 614–615 10.1038/35001144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bentley R. (2003) Diastereoisomerism, contact points, and chiral selectivity: a four-site saga. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 414, 1–12 10.1016/S0003-9861(03)00169-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fry M. (2016) The deciphering of the genetic code. in Landmark Experiments in Molecular Biology, pp. 421–480, Elsevier, Amsterdam [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ibba M., and Soll D. (2000) Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69, 617–650 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Guo M., and Schimmel P. (2012) Structural analyses clarify the complex control of mistranslation by tRNA synthetases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 22, 119–126 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ogle J. M., and Ramakrishnan V. (2005) Structural insights into translational fidelity. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74, 129–177 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.061903.155440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hou Y. M., and Schimmel P. (1988) A simple structural feature is a major determinant of the identity of a transfer RNA. Nature 333, 140–145 10.1038/333140a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Biou V., Yaremchuk A., Tukalo M., and Cusack S. (1994) The 2.9 Å crystal structure of T. thermophilus seryl-tRNA synthetase complexed with tRNA(Ser). Science 263, 1404–1410 10.1126/science.8128220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Giegé R., Sissler M., and Florentz C. (1998) Universal rules and idiosyncratic features in tRNA identity. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 5017–5035 10.1093/nar/26.22.5017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Routh S. B., and Sankaranarayanan R. (2017) Editing and proofreading in translation. in Reference Module in Life Sciences, Elsevier, Amsterdam [Google Scholar]

- 57. Beuning P. J., and Musier-Forsyth K. (2000) Hydrolytic editing by a class II aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 8916–8920 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bacher J. M., de Crécy-Lagard V., and Schimmel P. R. (2005) Inhibited cell growth and protein functional changes from an editing-defective tRNA synthetase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 1697–1701 10.1073/pnas.0409064102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Karkhanis V. A., Mascarenhas A. P., and Martinis S. A. (2007) Amino acid toxicities of Escherichia coli that are prevented by leucyl-tRNA synthetase amino acid editing. J. Bacteriol. 189, 8765–8768 10.1128/JB.01215-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Korencic D., Ahel I., Schelert J., Sacher M., Ruan B., Stathopoulos C., Blum P., Ibba M., and Söll D. (2004) A freestanding proofreading domain is required for protein synthesis quality control in Archaea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 10260–10265 10.1073/pnas.0403926101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Vargas-Rodriguez O., and Musier-Forsyth K. (2013) Exclusive use of trans-editing domains prevents proline mistranslation. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 14391–14399 10.1074/jbc.M113.467795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Calendar R., and Berg P. (1966) Purification and physical characterization of tyrosyl ribonucleic acid synthetases from Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. Biochemistry 5, 1681–1690 10.1021/bi00869a033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Calendar R., and Berg P. (1966) The catalytic properties of tyrosyl ribonucleic acid synthetases from Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. Biochemistry 5, 1690–1695 10.1021/bi00869a034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Soutourina J., Plateau P., and Blanquet S. (2000) Metabolism of d-aminoacyl-tRNAs in Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 32535–32542 10.1074/jbc.M005166200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Parker J. (2001) Elongation factors; translation. in Encyclopedia of Genetics, pp. 610–611, Elsevier, Amsterdam [Google Scholar]

- 66. Jekowsky E., Schimmel P. R., and Miller D. L. (1977) Isolation, characterization and structural implications of a nuclease-digested complex of aminoacyl transfer RNA and Escherichia coli elongation factor Tu. J. Mol. Biol. 114, 451–458 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90262-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Nissen P., Kjeldgaard M., Thirup S., Polekhina G., Reshetnikova L., Clark B. F., and Nyborg J. (1995) Crystal structure of the ternary complex of Phe-tRNAPhe, EF-Tu, and a GTP analog. Science 270, 1464–1472 10.1126/science.270.5241.1464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. LaRiviere F. J., Wolfson A. D., and Uhlenbeck O. C. (2001) Uniform binding of aminoacyl-tRNAs to elongation factor Tu by thermodynamic compensation. Science 294, 165–168 10.1126/science.1064242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Asahara H., and Uhlenbeck O. C. (2005) Predicting the binding affinities of misacylated tRNAs for Thermus thermophilus EF-Tu.GTP. Biochemistry 44, 11254–11261 10.1021/bi050204y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Pingoud A., and Urbanke C. (1980) Aminoacyl transfer ribonucleic acid binding site of the bacterial elongation factor Tu. Biochemistry 19, 2108–2112 10.1021/bi00551a017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yamane T., Miller D. L., and Hopfield J. J. (1981) Discrimination between d- and l-tyrosyl transfer ribonucleic acids in peptide chain elongation. Biochemistry 20, 7059–7064 10.1021/bi00528a001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ling J., So B. R., Yadavalli S. S., Roy H., Shoji S., Fredrick K., Musier-Forsyth K., and Ibba M. (2009) Resampling and editing of mischarged tRNA prior to translation elongation. Mol. Cell 33, 654–660 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Nomura M., Tissières A., and Lengyel P. (1974) Ribosomes (Cold Spring Harbor Monograph Series), Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 74. Steitz J. A. (1969) Polypeptide chain initiation: nucleotide sequences of the three ribosomal binding sites in bacteriophage R17 RNA. Nature 224, 957–964 10.1038/224957a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Shine J., and Dalgarno L. (1974) The 3′-terminal sequence of Escherichia coli 16S ribosomal RNA: complementarity to nonsense triplets and ribosome binding sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 71, 1342–1346 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ramakrishnan V. (2014) The ribosome emerges from a black box. Cell 159, 979–984 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wettstein F. O., and Noll H. (1965) Binding of transfer ribonucleic acid to ribosomes engaged in protein synthesis: number and properties of ribosomal binding sites. J. Mol. Biol. 11, 35–53 10.1016/S0022-2836(65)80169-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Rheinberger H. J., Sternbach H., and Nierhaus K. H. (1981) Three tRNA binding sites on Escherichia coli ribosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 78, 5310–5314 10.1073/pnas.78.9.5310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Agrawal R. K., Penczek P., Grassucci R. A., Li Y., Leith A., Nierhaus K. H., and Frank J. (1996) Direct visualization of A-, P-, and E-site transfer RNAs in the Escherichia coli ribosome. Science 271, 1000–1002 10.1126/science.271.5251.1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Steitz T. A. (2008) A structural understanding of the dynamic ribosome machine. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 242–253 10.1038/nrm2352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ramakrishnan V. (2002) Ribosome structure and the mechanism of translation. Cell 108, 557–572 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00619-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Puglisi J. D. (2009) Resolving the elegant architecture of the ribosome. Mol. Cell 36, 720–723 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Gromadski K. B., and Rodnina M. V. (2004) Streptomycin interferes with conformational coupling between codon recognition and GTPase activation on the ribosome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 316–322 10.1038/nsmb742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Schmeing T. M., Voorhees R. M., Kelley A. C., Gao Y. G., Murphy F. V. 4th, Weir J. R., and Ramakrishnan V. (2009) The crystal structure of the ribosome bound to EF-Tu and aminoacyl-tRNA. Science 326, 688–694 10.1126/science.1179700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Rodnina M. V., Beringer M., and Wintermeyer W. (2007) How ribosomes make peptide bonds. Trends Biochem. Sci. 32, 20–26 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Voorhees R. M., and Ramakrishnan V. (2013) Structural basis of the translational elongation cycle. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 82, 203–236 10.1146/annurev-biochem-113009-092313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Youngman E. M., Brunelle J. L., Kochaniak A. B., and Green R. (2004) The active site of the ribosome is composed of two layers of conserved nucleotides with distinct roles in peptide bond formation and peptide release. Cell 117, 589–599 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00411-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Routh S. B., and Sankaranarayanan R. (2017) Mechanistic insights into catalytic RNA-protein complexes involved in translation of the genetic code. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 109, 305–353 10.1016/bs.apcsb.2017.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Goto Y., Murakami H., and Suga H. (2008) Initiating translation with d-amino acids. RNA 14, 1390–1398 10.1261/rna.1020708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Ellman J. A., Mendel D., and Schultz P. G. (1992) Site-specific incorporation of novel backbone structures into proteins. Science 255, 197–200 10.1126/science.1553546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Fujino T., Goto Y., Suga H., and Murakami H. (2013) Reevaluation of the d-amino acid compatibility with the elongation event in translation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 1830–1837 10.1021/ja309570x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Melnikov S. V., Khabibullina N. F., Mairhofer E., Vargas-Rodriguez O., Reynolds N. M., Micura R., Söll D., and Polikanov Y. S. (2019) Mechanistic insights into the slow peptide bond formation with d-amino acids in the ribosomal active site. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 2089–2100 10.1093/nar/gky1211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Polikanov Y. S., Steitz T. A., and Innis C. A. (2014) A proton wire to couple aminoacyl-tRNA accommodation and peptide-bond formation on the ribosome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 787–793 10.1038/nsmb.2871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Calendar R., and Berg P. (1967) D-Tyrosyl RNA: formation, hydrolysis and utilization for protein synthesis. J. Mol. Biol. 26, 39–54 10.1016/0022-2836(67)90259-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Soutourina J., Plateau P., Delort F., Peirotes A., and Blanquet S. (1999) Functional characterization of the d-Tyr-tRNATyr deacylase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 19109–19114 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Takayama T., Ogawa T., Hidaka M., Shimizu Y., Ueda T., and Masaki H. (2005) Esterification of Escherichia coli tRNAs with d-histidine and d-lysine by aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 69, 1040–1041 10.1271/bbb.69.1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Englander M. T., Avins J. L., Fleisher R. C., Liu B., Effraim P. R., Wang J., Schulten K., Leyh T. S., Gonzalez R. L. Jr., and Cornish V. W. (2015) The ribosome can discriminate the chirality of amino acids within its peptidyl-transferase center. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 6038–6043 10.1073/pnas.1424712112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Zheng G., Liu W., Gong Y., Yang H., Yin B., Zhu J., Xie Y., Peng X., Qiang B., and Yuan J. (2009) Human d-Tyr-tRNA(Tyr) deacylase contributes to the resistance of the cell to d-amino acids. Biochem. J. 417, 85–94 10.1042/BJ20080617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Dwivedi S., Kruparani S. P., and Sankaranarayanan R. (2005) A d-amino acid editing module coupled to the translational apparatus in archaea. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 556–557 10.1038/nsmb943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Hussain T., Kruparani S. P., Pal B., Dock-Bregeon A. C., Dwivedi S., Shekar M. R., Sureshbabu K., and Sankaranarayanan R. (2006) Post-transfer editing mechanism of a d-aminoacyl-tRNA deacylase-like domain in threonyl-tRNA synthetase from archaea. EMBO J. 25, 4152–4162 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Ferri-Fioni M. L., Fromant M., Bouin A. P., Aubard C., Lazennec C., Plateau P., and Blanquet S. (2006) Identification in archaea of a novel d-Tyr-tRNATyr deacylase. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 27575–27585 10.1074/jbc.M605860200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Wydau S., van der Rest G., Aubard C., Plateau P., and Blanquet S. (2009) Widespread distribution of cell defense against d-aminoacyl-tRNAs. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 14096–14104 10.1074/jbc.M808173200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Ahmad S., Routh S. B., Kamarthapu V., Chalissery J., Muthukumar S., Hussain T., Kruparani S. P., Deshmukh M. V., and Sankaranarayanan R. (2013) Mechanism of chiral proofreading during translation of the genetic code. Elife 2, e01519 10.7554/eLife.01519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Routh S. B., Pawar K. I., Ahmad S., Singh S., Suma K., Kumar M., Kuncha S. K., Yadav K., Kruparani S. P., and Sankaranarayanan R. (2016) Elongation factor Tu prevents misediting of Gly-tRNA(Gly) caused by the design behind the chiral proofreading site of d-aminoacyl-tRNA deacylase. PLoS Biol. 14, e1002465 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Pawar K. I., Suma K., Seenivasan A., Kuncha S. K., Routh S. B., Kruparani S. P., and Sankaranarayanan R. (2017) Role of d-aminoacyl-tRNA deacylase beyond chiral proofreading as a cellular defense against glycine mischarging by AlaRS. Elife 6, e24001 10.7554/eLife.24001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Kuncha S. K., Suma K., Pawar K. I., Gogoi J., Routh S. B., Pottabathini S., Kruparani S. P., and Sankaranarayanan R. (2018) A discriminator code-based DTD surveillance ensures faithful glycine delivery for protein biosynthesis in bacteria. Elife 7, e38232 10.7554/eLife.38232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Kuncha S. K., Mazeed M., Singh R., Kattula B., Routh S. B., and Sankaranarayanan R. (2018) A chiral selectivity relaxed paralog of DTD for proofreading tRNA mischarging in Animalia. Nat. Commun. 9, 511 10.1038/s41467-017-02204-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Ahmad S., Muthukumar S., Kuncha S. K., Routh S. B., Yerabham A. S., Hussain T., Kamarthapu V., Kruparani S. P., and Sankaranarayanan R. (2015) Specificity and catalysis hardwired at the RNA-protein interface in a translational proofreading enzyme. Nat. Commun. 6, 7552 10.1038/ncomms8552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Hussain T., Kamarthapu V., Kruparani S. P., Deshmukh M. V., and Sankaranarayanan R. (2010) Mechanistic insights into cognate substrate discrimination during proofreading in translation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 22117–22121 10.1073/pnas.1014299107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Routh S. B., and Sankaranarayanan R. (2018) Enzyme action at RNA-protein interface in DTD-like fold. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 53, 107–114 10.1016/j.sbi.2018.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Guzmán F., Barberis S., and Illanes A. (2007) Peptide synthesis: chemical or enzymatic. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 10.2225/vol10-issue2-fulltext-13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Goto Y., Katoh T., and Suga H. (2011) Flexizymes for genetic code reprogramming. Nat. Protoc. 6, 779–790 10.1038/nprot.2011.331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Murakami H., Ohta A., Ashigai H., and Suga H. (2006) A highly flexible tRNA acylation method for non-natural polypeptide synthesis. Nat. Methods 3, 357–359 10.1038/nmeth877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Forster A. C., Tan Z., Nalam M. N., Lin H., Qu H., Cornish V. W., and Blacklow S. C. (2003) Programming peptidomimetic syntheses by translating genetic codes designed de novo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 6353–6357 10.1073/pnas.1132122100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Achenbach J., Jahnz M., Bethge L., Paal K., Jung M., Schuster M., Albrecht R., Jarosch F., Nierhaus K. H., and Klussmann S. (2015) Outwitting EF-Tu and the ribosome: translation with d-amino acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 5687–5698 10.1093/nar/gkv566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Ude S., Lassak J., Starosta A. L., Kraxenberger T., Wilson D. N., and Jung K. (2013) Translation elongation factor EF-P alleviates ribosome stalling at polyproline stretches. Science 339, 82–85 10.1126/science.1228985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Doerfel L. K., Wohlgemuth I., Kothe C., Peske F., Urlaub H., and Rodnina M. V. (2013) EF-P is essential for rapid synthesis of proteins containing consecutive proline residues. Science 339, 85–88 10.1126/science.1229017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Huter P., Arenz S., Bock L. V., Graf M., Frister J. O., Heuer A., Peil L., Starosta A. L., Wohlgemuth I., Peske F., Nováček J., Berninghausen O., Grübmuller H., Tenson T., Beckmann R., et al. (2017) Structural basis for polyproline-mediated ribosome stalling and rescue by the translation elongation factor EF-P. Mol. Cell 68, 515–527 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Katoh T., Iwane Y., and Suga H. (2017) Logical engineering of D-arm and T-stem of tRNA that enhances d-amino acid incorporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 12601–12610 10.1093/nar/gkx1129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]