Abstract

Background

Polyomaviruses (PyVs) have a wide range of hosts, from humans to fish, and their effects on hosts vary. The differences in the infection characteristics of PyV with respect to the host are assumed to be influenced by the biochemical function of the LT-Ag protein, which is related to the cytopathic effect and tumorigenesis mechanism via interaction with the host protein.

Methods

We carried out a comparative analysis of codon usage patterns of large T-antigens (LT-Ags) of PyVs isolated from various host species and their functional domains and sequence motifs. Parity rule 2 (PR2) and neutrality analysis were applied to evaluate the effects of mutation and selection pressure on codon usage bias. To investigate evolutionary relationships among PyVs, we carried out a phylogenetic analysis, and a correspondence analysis of relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) values was performed.

Results

Nucleotide composition analysis using LT-Ag gene sequences showed that the GC and GC3 values of avian PyVs were higher than those of mammalian PyVs. The effective number of codon (ENC) analysis showed host-specific ENC distribution characteristics in both the LT-Ag gene and the coding sequences of its domain regions. In the avian and fish PyVs, the codon diversity was significant, whereas the mammalian PyVs tended to exhibit conservative and host-specific evolution of codon usage bias. The results of our PR2 and neutrality analysis revealed mutation bias or highly variable GC contents by showing a narrow GC12 distribution and wide GC3 distribution in all sequences. Furthermore, the calculated RSCU values revealed differences in the codon usage preference of the LT-AG gene according to the host group. A similar tendency was observed in the two functional domains used in the analysis.

Conclusions

Our study showed that specific domains or sequence motifs of various PyV LT-Ags have evolved so that each virus protein interacts with host cell targets. They have also adapted to thrive in specific host species and cell types. Functional domains of LT-Ag, which are known to interact with host proteins involved in cell proliferation and gene expression regulation, may provide important information, as they are significantly related to the host specificity of PyVs.

Keywords: Polyomavirus, LT-Ag, Functional domains, Sequence motif, Codon usage pattern, RSCU

Background

Polyomaviruses (PyVs) are non-enveloped double-stranded DNA viruses; a total of 86 PyV species have been classified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. The classified member species belong to four genera, i.e., Alphapolyomavirus (36), Betapolyomavirus (32), Deltapolyomavirus (4), and Gammapolyomavirus (9), within the family Polyomaviridae (unassigned), while a genus of five species has not yet been classified. Their hosts are diverse, including humans, non-human primates (chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, and monkeys), non-primate mammals (bats, mice, racoon, badgers, cows, horses, elephants, alpacas, sea lions, seals, and dolphins), avian species (penguins, geese, and birds), and fish (sharks, perch, and cod) (https://talk.ictvonline.org/ictv-reports/ictv_online_report/dsdna-viruses/w/polyomaviridae).

The first PyV discovered was mouse PyV (MPyV), which was isolated from a murine tumor [1, 2] in the mid-1950s. Since then, simian virus 40 (SV40) was discovered in the renal cells of rhesus monkeys in the 1960s [3]. As mostly animal viruses were studied, the viruses seemed to be irrelevant to human diseases. However, two human PyVs, BKPyV and JCPyV, were found [4, 5], and in 2008, MCPyV was identified in human Merkel cell carcinoma tissue [6]. Thus, the various animal and human PyVs reported so far have drawn renewed attention. Most mammalian PyVs do not directly cause severe acute disease in infected hosts. However, an inconspicuous primary infection can persist for a lifetime, and when the host is in an immunosuppressed or immunocompromised state, such infection can lead to multiple diseases, such as progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and hemorrhagic cystitis, due to virus reactivation [7, 8]. PyV has a strong species-specific tendency, similar to papillomavirus [9, 10], and is thought to have co-evolved with amniotes. Various studies have been carried out to determine the infection characteristics of PyV. Therefore, it is necessary to understand their evolutionary history and their interaction with their hosts, as well as to interpret their genetic information.

Early and late gene RNAs of PyVs encode two and three proteins, respectively. The early gene is translated into 2 T-antigens (large T-antigen (LT-Ag) and small T-antigen), and the late gene is translated into three capsid proteins (VP1, VP2, and VP3) [11]. Among these, LT-Ag is directly related to tumorigenesis. Notably, the LT-Ag protein is known to bind to the p53 and Rb proteins, which are products of two typical tumor suppressor genes [12]. It has also been found to be a major factor determining the biochemical function of SV40 and MCPyV, which cause tumors in rodents and humans [13, 14]. The LT-Ag of PyV has functionally conserved domains, such as the DnaJ domain, LXCXE motif, NLS domain, Helicase domain, and p53 binding domain, that are present in most virus species [13]. Among these, the DnaJ domain, LXCXE motif, and p53 binding domain bind to proteins belonging to the cellular Hsc70 and Rb family and p53 cellular suppressor proteins, respectively, affecting replication and proliferation of the viral genome through DNA binding, ATP-dependent helicase, and ATPase activity. Specifically, when the early gene LT-Ag is continuously expressed, although PyV cannot to replicate its genome in nonpermissive hosts, cell transformation is induced, resulting in tumorigenesis. Each domain is considered to play an important role in this carcinogenesis.

PyVs vary in terms of toxicity to hosts, so their effects on hosts differ (Table 1). Variations in the infection characteristics of these viruses (whether they induce tumors due to binding to host proteins) among various hosts indicate the importance of the biochemical function of the LT-Ag protein in relation to host range and tumorigenesis. Therefore, in this study, we performed codon usage pattern, sequence similarity, and phylogenetic analyses using the genetic information of LT-Ag gene coding sequences (CDS) and major domains, to compare genetic characteristics. Based on the results of these analyses, we investigated the differences in the codon usage patterns depending on the taxon and PyV host and identified the relationships between phylogeny and sequence similarity among viruses. The genetic and evolutionary differences among the viruses identified by the comparative analysis offer a basis for explaining variations in their host range and toxicity. Based on these results, it is possible to infer the causes of the functional differences in LT-Ag among various PyVs.

Table 1.

Proven and possible diseases associated with PyVs

| Host | Virus name | Species | Abbr. | Clinical correlate | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Merkel cell polyomavirus | Human polyomavirus 5 | MCPyV | Merkel cell cancer | [6] |

| Human | Trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus | Human polyomavirus 8 | TSPyV | Trichodysplasia spinulosa | [15] |

| Human | BK polyomavirus | Human polyomavirus 1 | BKPyV |

Polyomavirus-associated nephropathy; haemorrhagic cystitis |

[4] |

| Human | JC polyomavirus | Human polyomavirus 2 | JCPyV | Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) | [5] |

| Human | Human polyomavirus 6 | Human polyomavirus 6 | HPyV6 | HPyV6 associated pruritic and dyskeratotic dermatosis (H6PD) | [16] |

| Human | Human polyomavirus 7 | Human polyomavirus 7 | HPyV7 | HPyV7-related epithelial hyperplasia | [16] |

| Monkey | Simian virus 40 | Macaca mulatta polyomavirus 1 | SV40 | PML-like disease in Immunocompromised animals | [3] |

| Hamster | hamster polyomavirus |

Mesocricetus auratus polyomavirus 1 |

HaPyV | Skin tumors | [17] |

| Mouse | mouse pneumotropic virus | Mus musculus polyomavirus 2 | MPtV | Respiratory disease in suckling mice | [18] |

| Bird | budgerigar fledgling disease virus | Aves polyomavirus 1 | BFDV | Budgerigar fledgling disease; polyomavirus disease | [19–21] |

| Finch | Finch polyomavirus | Pyrrhula pyrrhula polyomavirus 1 | FPyV | Polyomavirus disease | [22] |

| Goose | Goose hemorrhagic polyomavirus | Anser anser polyomavirus 1 | GHPV | Hemorrhagic nephritis and enteritis | [23] |

References are specified for first description

Methods

Data acquisition

The virus name, abbreviation, and classification information of 86 species belonging to the family Polyomaviridae were checked (https://talk.ictvonline.org/ictv-reports/ictv_online_report/dsdna-viruses/w/polyomaviridae), and the reference sequences were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information GenBank® (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) (Table 2). The CDS regions of the LT-Ag genes to be analyzed were extracted and classified into the following five groups, according to the host of each virus species: non-primate mammals (Group M); non-human primates (Group P); humans (Group H); avian (Group A); and fish (Group F). Known ORFs were concatenated for total codon analyses of LT-Ag. Accordingly, we performed the analysis using CDS regions in the form of the complement (join, codon start = 1) of LT-Ag from PyV reference sequences. Accession numbers are given in Table 2. To identify the domain regions contained in each LT-Ag gene CDS and extract the corresponding sequences, the amino acid sequence encoding each gene was scanned through PROSITE (https://prosite.expasy.org/), and the ScanProsite results were obtained in addition to ProRule-based predicted intra-domain features. The sequence information of the corresponding region was extracted and used for analysis. PROSITE provides predicted results and related information regarding protein domains, families, and functional sites through ProRule, a collection of rules based on profiles and patterns. Therefore, in this study, the sequence information of 54 DnaJ domains (PROSITE entry: PS50076) and 86 superfamily 3 helicases of DNA virus domains (PROSITE entry: PS51206), along with 86 complete gene sequences, was used for analysis (Table 3). Java programming was performed for LXCXE motif and sequence extraction and processing.

Table 2.

Description of sequence data used in this study

| No. | ICTV Taxonomy | NCBI Reference Sequence | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus name | Abbr. | Accession No. | Host species | Isolation source | Country | Year | bp | Group (host) |

Ref. | |

| 1 | bat polyomavirus 4a | BatPyV4a | NC_038556.1 | Artibeus planirostris | spleen | French Guiana | 2011 | 5187 | M | [24] |

| 2 | Ateles paniscus polyomavirus 1 | ApanPyV1 | NC_019853.1 | Ateles paniscus | NA | Germany | NA | 5273 | P | [25] |

| 3 | bat polyomavirus 5b1 | BatPyV5b-1 | NC_026767.1 | Pteropus vampyrus | spleen | Indonesia | 2012 | 5047 | M | [26] |

| 4 | bat polyomavirus 5a | BatPyV5a | NC_026768.1 | Dobsonia moluccensis | spleen | Indonesia | 2012 | 5075 | M | [26] |

| 5 | Bornean orang-utan polyomavirus | OraPyV-Bor | NC_013439.1 | Pongo pygmaeus | blood | NA | NA | 5168 | P | [27] |

| 6 | Cardioderma polyomavirus | CardiodermaPyV | NC_020067.1 | Cardioderma cor | rectal swab | Kenya | 2006 | 5372 | M | [28] |

| 7 | bat polyomavirus 4b | BatPyV4b | NC_028120.1 | Carollia perspicillata | spleen | French Guiana | 2011 | 5352 | M | [24] |

| 8 | chimpanzee polyomavirus | ChPyV | NC_014743.1 | Pan troglodytes verus | blood | NA | NA | 5086 | P | [29] |

| 9 | vervet monkey polyomavirus 1 | VmPyV1 | NC_019844.1 | Chlorocebus pygerythrus | spleen | Zambia | 2009 | 5157 | P | [30] |

| 10 | vervet monkey polyomavirus 3 | VmPyV3 | NC_025898.1 | Chlorocebus pygerythrus | spleen | Zambia | 2009 | 5055 | P | [30] |

| 11 | Eidolon polyomavirus 1 | EidolonPyV | NC_020068.1 | Eidolon helvum | rectal swab | Kenya | 2009 | 5294 | M | [28] |

| 12 | Gorilla gorilla gorilla polyomavirus 1 | GgorgPyV1 | NC_025380.1 | Gorilla gorilla gorilla | NA | Congo Republic | 2008 | 5300 | P | [31] |

| 13 | Human polyomavirus 9 | HPyV9 | NC_015150.1 | Homo sapiens | NA | Germany | 2009 | 5026 | H | [32] |

| 14 | Human polyomavirus 12 | HPyV12 | NC_020890.1 | Homo sapiens | NA | Germany | 2007 | 5033 | H | [33] |

| 15 | Macaca fascicularis polyomavirus 1 | MfasPyV1 | NC_019851.1 | Macaca fascicularis | NA | Germany | NA | 5087 | P | [25] |

| 16 | Merkel cell polyomavirus | MCPyV | NC_010277.2 | Homo sapiens | skin | USA | 2009 | 5387 | H | [16] |

| 17 | hamster polyomavirus | HaPyV | NC_001663.2 | Mesocricetus auratus strain Z3 | NA | Germany | 1967 | 5372 | M | [34] |

| 18 | bat polyomavirus 3b | BatPyV3b | NC_028123.1 | Molossus molossus | spleen | French Guiana | 2011 | 4903 | M | [24] |

| 19 | mouse polyomavirus | MPyV | NC_001515.2 | Mus musculus | NA | NA | NA | 5307 | M | NA |

| 20 | New Jersey polyomavirus | NJPyV | NC_024118.1 | Homo sapiens | bicep muscle | USA | 2013 | 5108 | H | [35] |

| 21 | Otomops polyomavirus 2 | OtomopsPyV | NC_020066.1 | Otomops martiensseni | rectal swab | Kenya | 2006 | 4914 | M | [28] |

| 22 | Otomops polyomavirus 1 | OtomopsPyV1 | NC_020071.1 | Otomops martiensseni | rectal swab | Kenya | 2006 | 5176 | M | [28] |

| 23 | Pan troglodytes verus polyomavirus 2a | PtrovPyV2a | NC_025370.1 | Pan troglodytes verus | NA | Cote d’Ivoire | 2010 | 5309 | P | [31] |

| 24 | Pan troglodytes verus polyomavirus 3 | PtrovPyV3 | NC_019855.1 | Pan troglodytes verus | NA | Cote d’Ivoire | NA | 5333 | P | [25] |

| 25 | Pan troglodytes verus polyomavirus 4 | PtrovPyV4 | NC_019856.1 | Pan troglodytes verus | NA | Cote d’Ivoire | NA | 5349 | P | [25] |

| 26 | Pan troglodytes verus polyomavirus 5 | PtrovPyV5 | NC_019857.1 | Pan troglodytes verus | NA | Cote d’Ivoire | NA | 4994 | P | [25] |

| 27 | Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii polyomavirus 2 | PtrosPyV2 | NC_019858.1 | Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii | NA | Uganda | NA | 4970 | P | [25] |

| 28 | Pan troglodytes verus polyomavirus 1a | PtrovPyV1a | NC_025368.1 | Pan troglodytes verus | NA | Cote d’Ivoire | 2009 | 5303 | P | [31] |

| 29 | Piliocolobus badius polyomavirus 2 | PbadPyV2 | NC_039051.1 | Piliocolobus badius | NA | Cote d’Ivoire | 2005 | 5148 | P | [36] |

| 30 | Piliocolobus rufomitratus polyomavirus 1 | PrufPyV1 | NC_019850.1 | Piliocolobus rufomitratus | NA | Cote d’Ivoire | NA | 5140 | P | [25] |

| 31 | raccoon polyomavirus | RacPyV | NC_023845.1 | raccoon | NA | USA | 2011 | 5016 | M | [37] |

| 32 | Rattus norvegicus polyomavirus 1 | RnorPyV1 | NC_027531.1 | Rattus norvegicus | spleen | Germany | 2005 | 5318 | M | [38] |

| 33 | bat polyomavirus 3a-B0454 | BatPyV3a-B0454 | NC_038557.1 | Sturnira lilium | spleen | French Guiana | 2011 | 5058 | M | [24] |

| 34 | Sumatran orang-utan polyomavirus | OraPyV-Sum | NC_028127.1 | Pongo abelii | blood | NA | NA | 5358 | P | [27] |

| 35 | Trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus | TSPyV | NC_014361.1 | Homo sapiens | skin | Netherlands | 2009 | 5232 | H | [15] |

| 36 | yellow baboon polyomavirus 1 | YbPyV1 | NC_025894.1 | Papio cynocephalus | spleen | Zambia | 2009 | 5064 | P | [30] |

| 37 | African elephant polyomavirus 1 | AelPyV1 | NC_022519.1 | Loxodonta africana | protruding ulcerated fibroma | Denmark | 2011 | 5722 | M | [39] |

| 38 | BatPyV4a | BatPyV2c | NC_038558.1 | Artibeus planirostris | spleen | French Guiana | 2011 | 5371 | M | [24] |

| 39 | Myodes glareolus polyomavirus 1 | BVPyV | NC_028117.1 | Myodes glareolus | blood serum and body fluids | Germany | 2013 | 5032 | M | [40] |

| 40 | bat polyomavirus 6a | BatPyV6a | NC_026762.1 | Acerodon celebensis | spleen | Indonesia | 2013 | 5019 | M | [26] |

| 41 | bat polyomavirus 6b | BatPyV6b | NC_026770.1 | Dobsonia moluccensis | spleen | Indonesia | 2012 | 5039 | M | [26] |

| 42 | bat polyomavirus 6c | BatPyV6c | NC_026769.1 | Dobsonia moluccensis | spleen | Indonesia | 2012 | 5046 | M | [26] |

| 43 | California sea lion polyomavirus 1 | SLPyV | NC_013796.1 | Zalophus californianus | tongue | USA | 2006 | 5112 | M | [41] |

| 44 | Cebus albifrons polyomavirus 1 | CalbPyV1 | NC_019854.2 | Cebus albifrons | NA | Germany | NA | 5013 | P | [25] |

| 45 | Cercopithecus erythrotis polyomavirus 1 | CeryPyV1 | NC_025892.1 | Cercopithecus erythrotis | NA | Cameroon | NA | 5189 | P | [25] |

| 46 | vervet monkey polyomavirus 2 | VmPyV2 | NC_025896.1 | Chlorocebus pygerythrus | kidney | Zambia | 2009 | 5167 | P | [30] |

| 47 | Microtus arvalis polyomavirus 1 | CVPyV | NC_028119.1 | Microtus arvalis | blood serum and body fluids | Germany | 2013 | 5024 | M | [40] |

| 48 | bat polyomavirus 2a | BatPyV2a | NC_028122.1 | Desmodus rotundus | spleen | French Guiana | 2011 | 5201 | M | [24] |

| 49 | equine polyomavirus | EPyV | NC_017982.1 | Equus caballus | eye | USA | 2003 | 4987 | M | [42] |

| 50 | BK polyomavirus | BKV; BKPyV | NC_001538.1 | Homo sapiens | NA | NA | NA | 5153 | H | [43] |

| 51 | KI polyomavirus | KIPyV | NC_009238.1 | Homo sapiens | NA | NA | NA | 5040 | H | [44] |

| 52 | JC polyomavirus | JCV; JCPyV | NC_001699.1 | Homo sapiens | NA | NA | NA | 5130 | H | [45] |

| 53 | Weddell seal polyomavirus | WsPyV | NC_032120.1 | Leptonychotes weddellii | kidney | Antarctica | 2014 | 5186 | M | NA |

| 54 | simian virus 40 | SV40 | NC_001669.1 | Macaca mulatta | NA | NA | NA | 5243 | P | [46] |

| 55 | Mastomys polyomavirus | MasPyV | NC_025895.1 | Mastomys natalensis | spleen | Zambia | 2009 | 4899 | M | [47] |

| 56 | Meles meles polyomavirus 1 | MmelPyV1 | NC_026473.1 | Meles meles | salivary gland | France | 2014 | 5187 | M | [48] |

| 57 | Miniopterus polyomavirus | MiniopterusPyV | NC_020069.1 | Miniopterus africanus | rectal swab | Kenya | 2006 | 5213 | M | [28] |

| 58 | mouse pneumotropic virus | MPtV | NC_001505.2 | Mus musculus | NA | NA | NA | 4754 | M | [49] |

| 59 | Myotis polyomavirus | MyPyV | NC_011310.1 | Myotis lucifugus | NA | Canada | 2007 | 5081 | M | [50] |

| 60 | Pan troglodytes verus polyomavirus 8 | PtrovPyV8 | NC_028635.1 | Western chimpanzee | colon | Netherlands | 2014 | 5163 | P | [51] |

| 61 | Pteronotus polyomavirus | PteronotusPyV | NC_020070.1 | Pteronotus davyi | oral swab | Guatemala | 2009 | 5136 | M | [28] |

| 62 | bat polyomavirus 2b | BatPyV2b | NC_028121.1 | Pteronotus parnellii | spleen | French Guiana | 2011 | 5041 | M | [24] |

| 63 | rat polyomavirus 2 | RatPyV2 | NC_032005.1 | Rattus norvegicus | NA | USA | 2016 | 5108 | M | NA |

| 64 | Saimiri sciureus polyomavirus 1 | SsciPyV1 | NC_038559.1 | Saimiri sciureus | NA | Germany | NA | 5067 | P | NA |

| 65 | squirrel monkey polyomavirus | SquiPyV | NC_009951.1 | Saimiri boliviensis | spleen | NA | NA | 5075 | P | [52] |

| 66 | alpaca polyomavirus | AlPyV | NC_034251.1 | Vicugna pacos | NA | USA | 2014 | 5052 | M | [53] |

| 67 | WU polyomavirus | WUPyV | NC_009539.1 | Homo sapiens | NA | Australia | NA | 5229 | H | [54] |

| 68 | yellow baboon polyomavirus 2 | YbPyV2 | AB767295.2 | Papio cynocephalus | spleen and kidney | Zambia | 2009 | 5181 | P | [30] |

| 69 | Human polyomavirus 6 | HPyV6 | NC_014406.1 | Homo sapiens | skin | USA | 2009 | 4926 | H | [16] |

| 70 | Human polyomavirus 7 | HPyV7 | NC_014407.1 | Homo sapiens | skin | USA | 2009 | 4952 | H | [16] |

| 71 | MW polyomavirus | MWPyV | NC_018102.1 | Homo sapiens | stool | Malawi | 2008 | 4927 | H | [55] |

| 72 | STL polyomavirus | STLPyV | NC_020106.1 | Homo sapiens | fecal specimen | Malawi | NA | 4776 | H | [56] |

| 73 | Adélie penguin polyomavirus | ADPyV | NC_026141.2 | Pygoscelis adeliae | fecal material | Antarctica | 2012 | 4988 | A | [57] |

| 74 | budgerigar fledgling disease virus | BFDV | NC_004764.2 | Falconiformes and Psittaciformes (wild birds) | NA | NA | NA | 4981 | A | [58] |

| 75 | butcherbird polyomavirus | Butcherbird PyV | NC_023008.1 | Cracticus torquatus | periocular skin | Australia | 2009 | 5084 | A | [59] |

| 76 | canary polyomavirus | CaPyV | NC_017085.1 | Serinus canaria | liver | Netherlands | 2007 | 5421 | A | [60] |

| 77 | crow polyomavirus | CpyV | NC_007922.1 | Corvus monedula | NA | NA | 2005 | 5079 | A | [22] |

| 78 | Erythrura gouldiae polyomavirus 1 | EgouPyV1 | NC_039052.1 | Erythrura gouldiae | liver | Poland | 2014 | 5172 | A | [61] |

| 79 | finch polyomavirus | FPyV | NC_007923.1 | Pyrrhula pyrrhula griseiventris | NA | NA | 2005 | 5278 | A | [22] |

| 80 | goose hemorrhagic polyomavirus | GHPV | NC_004800.1 | goose | NA | Germany | 2001 | 5256 | A | [62] |

| 81 | Hungarian finch polyomavirus | HunFPyV | NC_039053.1 | Lonchura maja | kidney and liver | Hungary | 2011 | 5284 | A | [63] |

| 82 | black sea bass-associated polyomavirus 1 | BassPyV1 | NC_025790.1 | Centropristis striata | NA | USA | 2014 | 7369 | F | [64] |

| 83 | bovine polyomavirus | BPyV | NC_001442.1 | Bos taurus | kidney | NA | NA | 4697 | M | [65] |

| 84 | dolphin polyomavirus 1 | DPyV | NC_025899.1 | Delphinus delphis | trachea | USA | 2010 | 5159 | M | [66] |

| 85 | giant guitarfish polyomavirus | GfPyV1 | NC_026244.1 | Rhynchobatus djiddensis | skin lesion | USA | 2014 | 3962 | F | [67] |

| 86 | sharp-spined notothenia polyomavirus | SspPyV | NC_026944.1 | Trematomus pennellii | NA | Antarctica | 2013 | 6219 | F | NA |

No. 1~36: Alphapolyomaviruses; No. 37~68: Betaphapolyomaviruses; No. 69~72: Deltapolyomaviruses; No. 73~81: Gammapolyomaviruses; No. 82~86: Unassigned polyomaviruses; NA Not available

All 86 viruses were classified into 5 groups according to their host as follows: non-primate mammals (Group M); non-human primate (Group P); human (Group H); avian (Group A); fish (Group F)

Table 3.

Domains and motifs of PyVs used in this study

| No. | Abbr. | Accession no. | DnaJ domain | LXCXE motif | Helicase domain | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | End | nt length | Start | End | a.a. sequence | Start | End | nt length | |||

| 1 | BatPyV4a | NC_038556.1 | 12 | 67 | 168 | 107 | 111 | LRCDE | 405 | 564 | 480 |

| 2 | ApanPyV1 | NC_019853.1 | 12 | 77 | 198 | 122 | 126 | LFCNE | 441 | 601 | 483 |

| 3 | BatPyV5b-1 | NC_026767.1 | 12 | 74 | 189 | – | – | – | 376 | 536 | 483 |

| 4 | BatPyV5a | NC_026768.1 | 12 | 67 | 168 | – | – | – | 382 | 546 | 495 |

| 5 | OraPyV-Bor | NC_013439.1 | 12 | 77 | 198 | 122 | 126 | LFCDE | 422 | 602 | 543 |

| 6 | CardiodermaPyV | NC_020067.1 | 12 | 77 | 198 | 212 | 216 | LYCDE | 556 | 716 | 483 |

| 7 | BatPyV4b | NC_028120.1 | – | – | – | 152 | 156 | LLCEE | 458 | 651 | 582 |

| 8 | ChPyV | NC_014743.1 | 12 | 96 | 255 | – | – | – | 379 | 580 | 606 |

| 9 | VmPyV1 | NC_019844.1 | 12 | 80 | 207 | 107 | 111 | LHCNE | 479 | 640 | 486 |

| 10 | VmPyV3 | NC_025898.1 | 12 | 75 | 192 | 131 | 135 | LFCSE | 462 | 622 | 483 |

| 11 | EidolonPyV | NC_020068.1 | – | – | – | 236 | 240 | LRCDE | 588 | 752 | 495 |

| 12 | GgorgPyV1 | NC_025380.1 | – | – | – | 200 | 204 | LFCDE | 554 | 714 | 483 |

| 13 | HPyV9 | NC_015150.1 | 12 | 86 | 225 | 123 | 127 | LFCSE | 446 | 606 | 483 |

| 14 | HPyV12 | NC_020890.1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 473 | 635 | 489 |

| 15 | MfasPyV1 | NC_019851.1 | 12 | 86 | 225 | 125 | 129 | LFCTE | 465 | 665 | 603 |

| 16 | MCPyV | NC_010277.2 | – | – | – | 212 | 216 | LFCDE | 567 | 727 | 483 |

| 17 | HaPyV | NC_001663.2 | – | – | – | 130 | 134 | LTCQE | 522 | 682 | 483 |

| 18 | BatPyV3b | NC_028123.1 | – | – | – | 107 | 111 | LYCDE | 467 | 630 | 492 |

| 19 | MPyV | NC_001515.2 | – | – | – | 142 | 146 | LFCYE | 549 | 709 | 483 |

| 20 | NJPyV | NC_024118.1 | 12 | 80 | 207 | 107 | 111 | LHCDE | 476 | 636 | 483 |

| 21 | OtomopsPyV | NC_020066.1 | 12 | 92 | 243 | 107 | 111 | LYCDE | 483 | 643 | 483 |

| 22 | OtomopsPyV1 | NC_020071.1 | – | – | – | 185 | 189 | LRCDE | 520 | 680 | 483 |

| 23 | PtrovPyV2a | NC_025370.1 | – | – | – | 200 | 204 | LFCDE | 556 | 716 | 483 |

| 24 | PtrovPyV3 | NC_019855.1 | 12 | 75 | 192 | – | – | – | 486 | 646 | 483 |

| 25 | PtrovPyV4 | NC_019856.1 | 12 | 75 | 192 | – | – | – | 489 | 646 | 474 |

| 26 | PtrovPyV5 | NC_019857.1 | 12 | 86 | 225 | 123 | 127 | LFCSE | 439 | 599 | 483 |

| 27 | PtrosPyV2 | NC_019858.1 | 12 | 85 | 222 | 108 | 112 | LYCSE | 432 | 632 | 603 |

| 28 | PtrovPyV1a | NC_025368.1 | – | – | – | 203 | 207 | LYCDE | 558 | 718 | 483 |

| 29 | PbadPyV2 | NC_039051.1 | 12 | 92 | 243 | 107 | 111 | LHCNE | 476 | 637 | 486 |

| 30 | PrufPyV1 | NC_019850.1 | 12 | 93 | 246 | 107 | 111 | LHCNE | 476 | 637 | 486 |

| 31 | RacPyV | NC_023845.1 | – | – | – | 167 | 171 | LFCEE | 504 | 685 | 546 |

| 32 | RnorPyV1 | NC_027531.1 | – | – | – | 128 | 132 | LYCSE | 535 | 698 | 492 |

| 33 | BatPyV3a-B0454 | NC_038557.1 | – | – | – | 107 | 111 | LHCHE | 477 | 637 | 483 |

| 34 | OraPyV-Sum | NC_028127.1 | 12 | 75 | 192 | – | – | – | 489 | 649 | 483 |

| 35 | TSPyV | NC_014361.1 | 12 | 77 | 198 | 122 | 126 | LFCHE | 445 | 605 | 483 |

| 36 | YbPyV1 | NC_025894.1 | 12 | 75 | 192 | 131 | 135 | LFCSE | 463 | 663 | 603 |

| 37 | AelPyV1 | NC_022519.1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 400 | 564 | 495 |

| 38 | BatPyV2c | NC_038558.1 | – | – | – | 223 | 227 | LLCEE | 559 | 719 | 483 |

| 39 | BVPyV | NC_028117.1 | 12 | 67 | 168 | 146 | 150 | LTCHE | 383 | 574 | 576 |

| 40 | BatPyV6a | NC_026762.1 | – | – | – | 84 | 88 | LFCHE | 395 | 557 | 489 |

| 41 | BatPyV6b | NC_026770.1 | – | – | – | 98 | 102 | LFCHE | 407 | 570 | 492 |

| 42 | BatPyV6c | NC_026769.1 | – | – | – | 100 | 104 | LFCRE | 426 | 587 | 486 |

| 43 | SLPyV | NC_013796.1 | 12 | 77 | 198 | 113 | 117 | LHCHE | 397 | 556 | 480 |

| 44 | CalbPyV1 | NC_019854.2 | – | – | – | 100 | 104 | LFCNE | 410 | 570 | 483 |

| 45 | CeryPyV1 | NC_025892.1 | 12 | 75 | 192 | 105 | 109 | LFCHE | 402 | 562 | 483 |

| 46 | VmPyV2 | NC_025896.1 | 12 | 75 | 192 | 105 | 109 | LFCHE | 402 | 562 | 483 |

| 47 | CVPyV | NC_028119.1 | 12 | 67 | 168 | 145 | 149 | LSCNE | 382 | 573 | 576 |

| 48 | BatPyV2a | NC_028122.1 | 12 | 80 | 207 | – | – | – | 406 | 565 | 480 |

| 49 | EPyV | NC_017982.1 | 12 | 86 | 225 | 105 | 109 | LRCDE | 402 | 562 | 483 |

| 50 | BKPyV | NC_001538.1 | 12 | 75 | 192 | 105 | 109 | LFCHE | 402 | 562 | 483 |

| 51 | KIPyV | NC_009238.1 | – | – | – | 108 | 112 | LRCNE | 410 | 572 | 489 |

| 52 | JCPyV | NC_001699.1 | 12 | 75 | 192 | 105 | 109 | LFCHE | 401 | 561 | 483 |

| 53 | WsPyV | NC_032120.1 | 12 | 77 | 198 | 113 | 117 | LHCNE | 400 | 561 | 486 |

| 54 | SV40 | NC_001669.1 | 12 | 75 | 192 | 103 | 107 | LFCSE | 400 | 560 | 483 |

| 55 | MasPyV | NC_025895.1 | – | – | – | 101 | 105 | LFCNE | 414 | 576 | 489 |

| 56 | MmelPyV1 | NC_026473.1 | 12 | 80 | 207 | 111 | 115 | LRCDE | 365 | 559 | 585 |

| 57 | MiniopterusPyV | NC_020069.1 | 12 | 75 | 192 | 103 | 107 | LHCHE | 369 | 560 | 576 |

| 58 | MPtV | NC_001505.2 | – | – | – | 103 | 107 | LFCNE | 418 | 573 | 468 |

| 59 | MyPyV | NC_011310.1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 441 | 603 | 489 |

| 60 | PtrovPyV8 | NC_028635.1 | 12 | 75 | 192 | 105 | 109 | LFCHE | 402 | 562 | 483 |

| 61 | PteronotusPyV | NC_020070.1 | 12 | 80 | 207 | 108 | 112 | LRCDE | 405 | 564 | 480 |

| 62 | BatPyV2b | NC_028121.1 | 12 | 80 | 207 | 108 | 112 | LRCDE | 406 | 617 | 636 |

| 63 | RatPyV2 | NC_032005.1 | 12 | 79 | 204 | 178 | 182 | LHCDE | 474 | 634 | 483 |

| 64 | SsciPyV1 | NC_038559.1 | – | – | – | 101 | 105 | LFCHE | 410 | 572 | 489 |

| 65 | SquiPyV | NC_009951.1 | – | – | – | 101 | 105 | LFCHE | 411 | 570 | 480 |

| 66 | AlPyV | NC_034251.1 | 12 | 67 | 168 | 107 | 111 | LYCNE | 407 | 567 | 483 |

| 67 | WUPyV | NC_009539.1 | 12 | 89 | 234 | 108 | 112 | LRCNE | 417 | 579 | 489 |

| 68 | YbPyV2 | AB767295.2 | 12 | 75 | 192 | 105 | 109 | LFCHE | 402 | 562 | 483 |

| 69 | HPyV6 | NC_014406.1 | – | – | – | 109 | 113 | LYCDE | 393 | 571 | 537 |

| 70 | HPyV7 | NC_014407.1 | – | – | – | 109 | 113 | LYCTE | 416 | 576 | 483 |

| 71 | MWPyV | NC_018102.1 | – | – | – | 105 | 109 | LSCNE | 421 | 580 | 480 |

| 72 | STLPyV | NC_020106.1 | 12 | 83 | 216 | 105 | 109 | LTCNE | 406 | 566 | 483 |

| 73 | ADPyV | NC_026141.2 | 8 | 61 | 162 | 69 | 73 | LYCEE | 408 | 582 | 525 |

| 74 | BFDV | NC_004764.2 | 6 | 82 | 231 | – | – | – | 372 | 532 | 483 |

| 75 | Butcherbird PyV | NC_023008.1 | 8 | 67 | 180 | 70 | 74 | LFCDE | 410 | 572 | 489 |

| 76 | CaPyV | NC_017085.1 | 8 | 61 | 162 | 67 | 71 | LSCNE | 390 | 550 | 483 |

| 77 | CpyV | NC_007922.1 | 11 | 80 | 210 | 69 | 73 | LQCEE | 405 | 569 | 495 |

| 78 | EgouPyV1 | NC_039052.1 | 8 | 75 | 204 | 70 | 74 | LYCEE | 374 | 572 | 597 |

| 79 | FPyV | NC_007923.1 | 6 | 70 | 195 | 60 | 64 | LFCDE | 382 | 543 | 486 |

| 80 | GHPV | NC_004800.1 | 8 | 81 | 222 | 65 | 69 | LFCDE | 404 | 599 | 588 |

| 81 | HunFPyV | NC_039053.1 | 6 | 77 | 216 | 60 | 64 | LFCDE | 382 | 543 | 486 |

| 82 | BassPyV1 | NC_025790.1 | – | – | – | 105 | 109 | LMCGE | 338 | 495 | 474 |

| 83 | BPyV | NC_001442.1 | 10 | 73 | 192 | 93 | 97 | LHCDE | 391 | 586 | 588 |

| 84 | DPyV | NC_025899.1 | 11 | 77 | 201 | 82 | 86 | LYCDE | 357 | 536 | 540 |

| 85 | GfPyV1 | NC_026244.1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 348 | 517 | 510 |

| 86 | SspPyV | NC_026944.1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 372 | 529 | 474 |

ScanProsite results together with ProRule-based predicted intra-domain features were used for functional domains retained in LT-Ag of PyVs. LXCXE motifs and their encoding sequences were extracted through the JAVA programming

Phylogenetic analysis

Multiple sequence alignments were performed for each sequence using MUSCLE, and the phylogeny was reconstructed using the maximum likelihood (ML) method based on the Tamura-Nei model [68] using MEGA 7.0.26 [69]. Bootstrap analysis [70] was carried out with 1000 replicates of the dataset to determine the robustness of the individual nodes. The reconstructed trees confirmed the phylogenetic relationships for viral sequences of the LT-Ag gene, DnaJ, and helicase from different host species. Based on these results, the 86 viral species were divided into five groups [non-primate mammals (Group M), non-human primates (Group P), humans (Group H), avian (Group A), and fish (Group F)]. For the purpose of this study, virus group information based on the phylogenetic relationships was considered when conducting various analyses and interpreting and discussing the results.

Compositional analysis

The CodonW (https://sourceforge.net/projects/codonw/) and CALcal (http://genomes.urv.es/CAIcal/) programs were used to perform nucleotide composition analysis. Various nucleotide compositional properties were calculated for the sequences corresponding to the CDS of the PyV LT-Ag gene, DnaJ domain, and helicase domain. The frequency of each nucleotide (%A, %C, %T, and %G), GC and AT contents (%GC and %AT), each nucleotide at the third position of synonymous codons (%A3, %C3, %T3, and %G3), G + C (%GC3) and A + T contents (%AT3) at the third codon, and G + C (%GC12) and A + T mean values (%AT12) at the first and second codons were calculated. Genetic variability was analyzed by calculating the nucleotide variability of the LT-Ag genes and two domains in each virus group. The total number of segregating sites, total number of mutations, average number of nucleotide differences between sequences, and nucleotide diversity were estimated using DnaSP v. 5.10.01 [71].

Effective number of codons (ENC) analysis

Analysis of the effective number of codons (ENC) was used to quantify the absolute codon usage bias in the PyV LT-Ag gene CDS, independent of the gene length. ENC values range from 20 to 61; 20 represents the largest codon usage bias, in which only one of the possible synonymous codons is used for the corresponding amino acid; 61 indicates no bias and means that all possible synonymous codons are used equally for the corresponding amino acid. Generally, genes are considered to have significant codon bias when the ENC value is less than 35 [72, 73].

Parity rule 2 (PR2) analysis

Parity rule 2 (PR2) analysis is commonly used to investigate the effects of mutations and selection pressure on codon usage bias in genes. The PR2 plot positions the AT-bias [A3/(A3 + T3)] and GC-bias [G3/(G3 + C3)] at the third codon of four-codon amino acids [fourfold degenerate codon families: Ala (A), Arg (R), Gly (G), Leu (L), Pro (P), Ser (S), Thr (T), and Val (V)] of the entire genome are shown on the vertical axis (y) and horizontal axis (x), respectively. The location of the plot with both coordinates at 0.5 is A = T, G = C (PR2), indicating no bias between the effects of mutation and natural selection (replacement rate). The distance between the coordinate position (0.5, 0.5) and the plot dot, which is the center of the plot, indicates the degree and direction of the PR2 bias [74, 75].

Neutral evolution analysis

Neutrality plots are used to evaluate the relationship between the third codon positions to reflect the role of directional mutation pressure. Consequently, the gradients of the regression lines in the neutrality plot depict the relationship between GC12s and GC3s, elucidating the evolutionary rates of directional mutation pressure–natural selection equilibrium. When the gradient of the regression line is 0 (all plot dots are located on a line parallel to the abscissa), there are no effects from directional mutation pressure. When the gradient is 1 (all plot dots are located on the diagonal), we have complete neutrality. Therefore, the regression lines of the neutrality plot can be used to determine the main factor controlling evolution by measuring the degree of neutrality [76]. DnaSP v. 5.10.01 [71] was used to calculate Tajima’s D [77], Fu and Li’s D*, and F* [78] as tests of neutrality. Tajima’s D statistic measures the departure from neutrality for all mutations in a genomic region [77] and is based on the differences between the number of segregating sites and the average number of nucleotide differences. Fu and Li’s D* test is based on the differences between the number of singletons (mutations appearing only once in the sequence) and the total number of mutations. Fu and Li’s F* test is based on the differences between the number of singletons and the average number of nucleotide differences between every pair of sequences [78, 79].

Relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) analysis

Relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU), a measure of the preference for the use of a synonymous codon, is defined as the ratio of the observed number of synonymous codons used to the expected value of the codon occurrence frequency [80]. In general, codons with an RSCU value greater than 1.0 are considered to have a higher preference (abundant codons), and those with an RSCU value lower than 1.0 have a lower preference (less-abundant codons). When the RSCU value is equal to 1.0, either the preference for synonymous codons is the same or the codon usage is random [81]. Specifically, a codon with an RSCU value of 1.6 or more is an over-represented codon, and a codon with an RSCU value of 0.6 or less is considered an under-represented codon (≤0.6) [82]. Using the CodonW and CAIcal programs, the RSCU values of the sequences of the 54 DnaJ domains and 86 helicase domains were calculated, along with 86 LT-Ag gene CDS. Comparative analysis and visualization of each group were performed using XLSTAT.

Calculation of the codon adaptation index (CAI)

The codon adaptation index (CAI) is a quantitative measurement ranging from 0 to 1 that predicts gene expression levels based on CDS. The most frequent codons show the highest relative adaptation to the host, and sequences with a higher CAI are preferred over those with a lower CAI [83]. CAI analysis of the LT-Ag gene CDS was carried out using CAIcal [84], and the synonymous codon usage pattern of Homo sapiens, which was downloaded from the Codon Usage Database (CUD) [85], was used as the reference dataset.

Correspondence analysis (COA)

Each group of RSCU values was analyzed using the correspondence analysis (COA) method, and the results were visualized using XLSTAT. Individual data representing the LT-Ag gene coding region were expressed as a vector with 59 dimensions, and we included 59 codons, excluding methionine (ATG) and tryptophan (TGG), without synonymous codons in the analysis.

Selection pressure analysis

The number of non-synonymous substitutions per non-synonymous site (dN), the number of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (dS), and the dN/dS ratios for the nucleotide sequences of the LT-Ag genes and two domains were estimated for all isolates in each virus group using MEGA 7.0.26 [69]. A gene is under positive (or diversifying) selection when the dN/dS ratio is > 1, neutral selection when dN/dS ratio = 1, and negative (or purifying) selection when the dN/dS ratio < 1.

Results

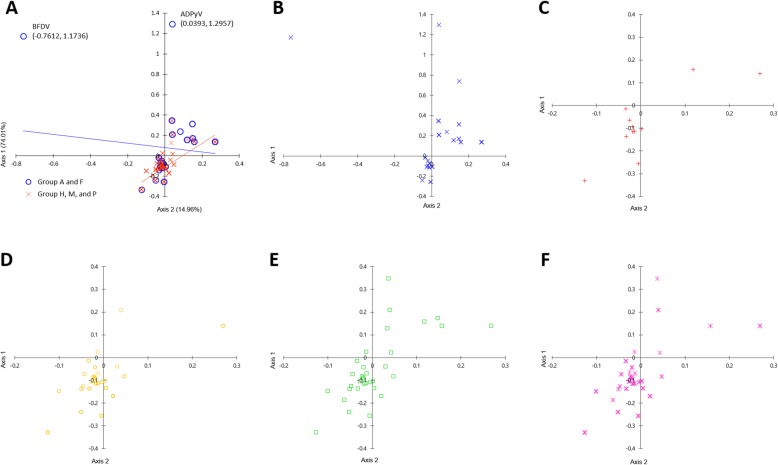

Sequence similarity and evolutionary relationships among PyVs

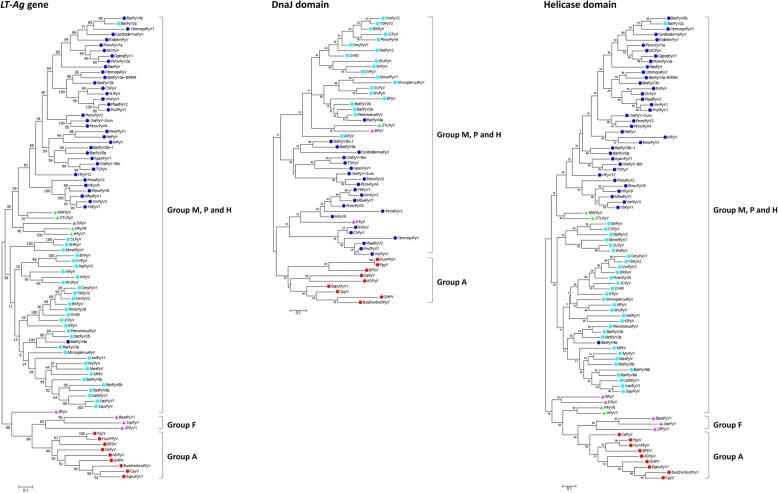

Phylogenetic analyses using the LT-Ag gene, DnaJ domain, and helicase domain revealed that, except for two bat viruses, Alphapolyomavirus and Betapolyomavirus were grouped independently, and Gammapolyomavirus formed a separate cluster. Deltapolyomavirus and the unassigned viruses clustered together or were independent in all of the trees. Thus, except for some exceptional cases [bat PyV 2c (BatPyV2c), bat PyV 4a (BatPyV4a), and DPyV] in the ML-based tree, the viruses were generally grouped by genes. When the clustering pattern per host was examined, Groups M, P, and H formed a large cluster. In other trees, except for the DnaJ domain-based tree for which domain information was lacking (Group F was not included in the analysis), Group A (avian viruses) and Group F (fish viruses) were grouped independently (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic trees of PyV LT-Ag genes. PyVs were classified according to the host species (mammal, avian, and fish) in the ML-based trees constructed using nucleotide sequences of LT-Ag coding genes, DnaJ domains, and helicase domains (Alphapolyomaviruses [ ]; Betaapolyomaviruses [

]; Betaapolyomaviruses [ ]; Deltapolyomaviruses [

]; Deltapolyomaviruses [ ]; Gammapolyomaviruses [

]; Gammapolyomaviruses [ ]; unassigned [

]; unassigned [ ])

])

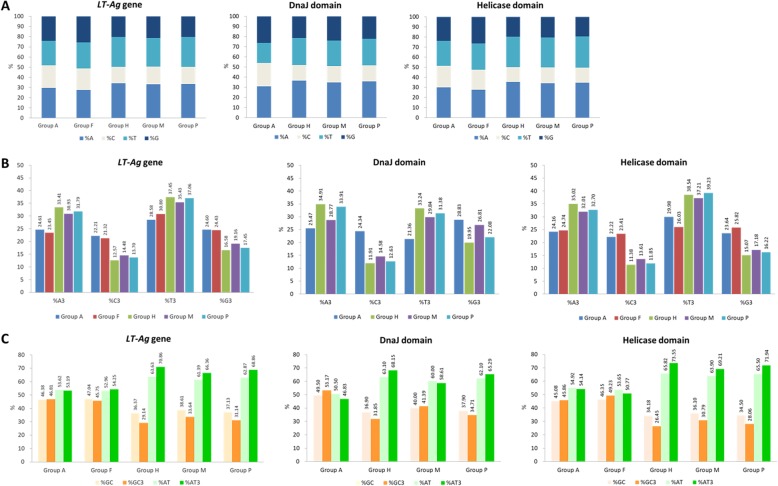

Compositional properties of LT-Ag genes

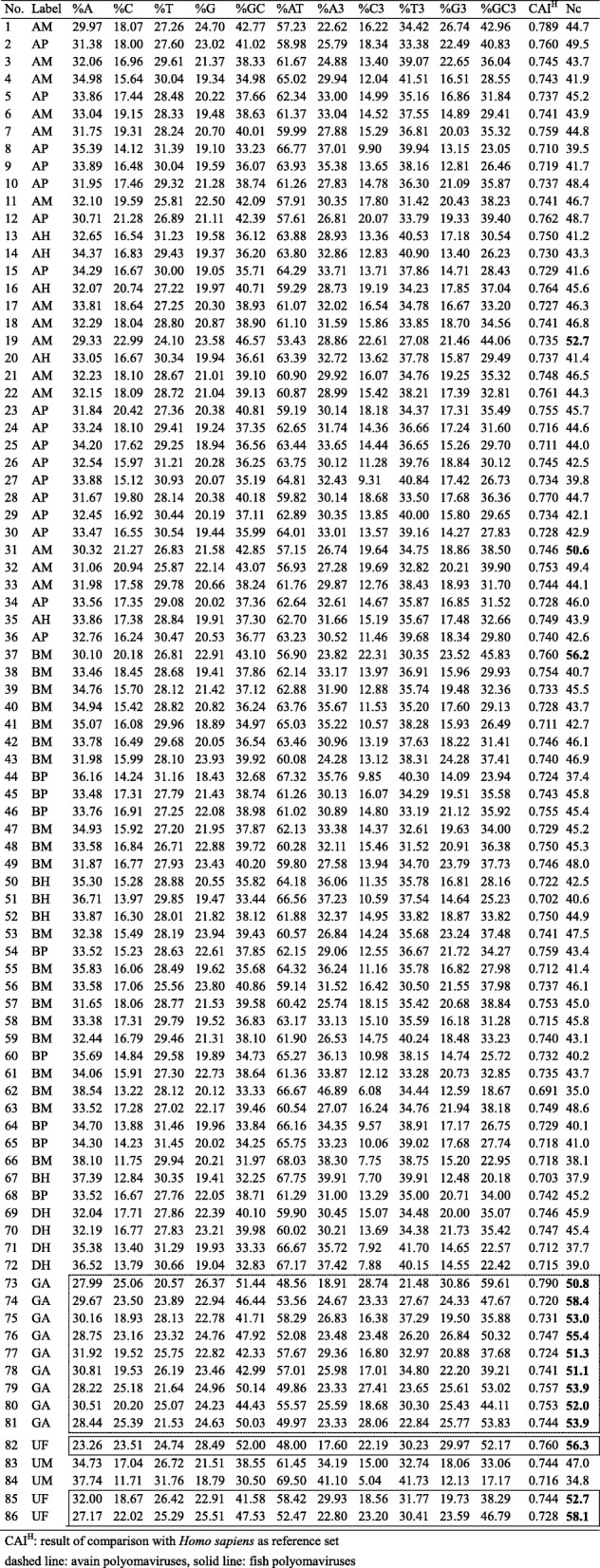

To confirm the effect of differences in composition on the codon usage patterns observed in 86 PyV species isolated from different hosts, we analyzed the nucleotide compositions of the complete sequences of the LT-Ag genes, as well as those of the DnaJ domain and helicase domain regions of the LT-Ag protein, in each virus (Table 4). These domains play particularly important roles in the biochemical function of LT-Ag and are relatively well conserved in various PyV species compared to other domain regions. Thus, it is possible to extract more accurate homologous sequences based on the protein sequence pattern and profile information using these domains. Hence, these became the subjects of this analysis. After analyzing the mean composition of each group (%), nucleotide A was the highest in all groups, and C was lowest in all sequences except for the DnaJ domain CDS of Group A (Fig. 2). In the nucleotides observed at the third position of the synonymous codons (A3, T3, G3, and C3), G3 was higher than C3. T3 was higher than A3 in all groups except Group A, H, and P of the DnaJ domain. In all analyzed sequences, the GC and GC3 values were significantly higher in Groups A and F (> 45), and Groups H, M, and P exhibited high AT and AT3 values (> 60). In particular, group H viruses had significantly higher AT3 values (> 70). According to the nucleotide frequency at the third position of the codon, all sequences except the DnaJ domain CDS of avian PyVs belonging to Group A were AT-rich, but at the individual nucleotide level, G and A were dominant over C and T. In previous studies, the GC values for the entire genomes of JCPyV, BKPyV, SV40, budgerigar fledgling disease virus (BFDV), MPyV, goose hemorrhagic PyV (GHPyV), and bovine PyV (BPyV) were 0.41, 0.41, 0.42, 0.5, 0.48, 0.42, and 0.42, respectively, and the GC3 values were 0.3, 0.28, 0.31, 0.45, 0.42, 0.43, and 0.33, respectively [86]. Based on the LT-Ag CDS results for the above viruses, the %GC values of the corresponding virus were 38.12, 35.82, 37.85, 46.44, 46.57, 44.43, and 38.55, respectively, and the %GC3 values were 33.82, 28.16, 34.27, 47.67, 44.06, 44.11, and 33.06, respectively. As in previous studies using whole genome sequences, the GC and GC3 values of the bird PyV in the LT-Ag gene were higher than those of the mammalian PyV.

Table 4.

Nucleotide compositions of the LT-Ag genes of 86 polyomaviruses

CAIH: result of comparison with Homo sapiens as reference set

dashed line: avain polyomaviruses, solid line: fish polyomaviruses

Fig. 2.

Compositional features of nucleotide sequences of LT-Ag coding genes, DnaJ domains, and helicase domains. a Nucleotide distribution of A, C, U, and G. b Distribution frequency calculated only for the third codon base. c GC and AT content at all codon positions (GC% and AT%) and at the third position (GC3s and AT3s)

Codon usage patterns in the LT-Ag genes from different hosts

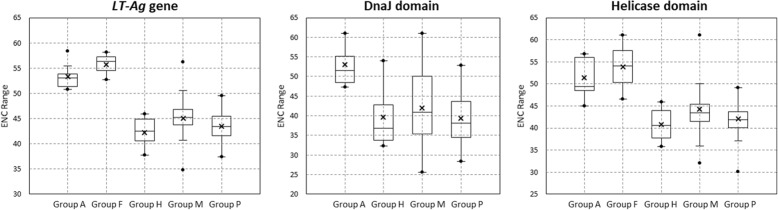

The ENC values were calculated to estimate the magnitude of the codon usage bias in the LT-Ag sequences of the PyVs. A mean value of 45.4 ± 4.9 was confirmed for all LT-Ag gene sequences analyzed. The lowest ENC value was observed in dolphin PyV 1 (DPyV) (34.8), and the highest value was observed in BFDV (58.4). Groups A and F viruses had ENC ranges of 50.8–58.4 and 52.7–58.1, respectively. The mean ENC values of Groups H, M, and P viruses were 42.254, 45.078, and 43.520, respectively, significantly lower than those of Groups A and F (53.311 and 55.700, respectively). Thus, the sequence compositions in the LT-Ag gene according to host species had higher ENC values (> 50) in avian PyV and fish PyV than in mammalian PyV (Groups M, P, and H), implying that the codon diversity was greater in the LT-Ag CDS region of Groups A and F viruses. A similar ENC range pattern was observed in both domains. In the DnaJ domain, Group A viruses had an ENC range of 47.26–61.0. The mean ENC values of Groups H, M, and P viruses were 39.5, 42.0, and 39.3, respectively, significantly lower than the mean ENC value of Group A (53.0). In the helicase domain, Groups A and F viruses had ENC ranges of 44.94–56.81 and 46.53–61.0, respectively. The mean ENC values of Groups H, M, and P viruses were 40.8, 44.3, and 42.0, respectively, which were significantly lower than those of Groups A and F (51.5 and 53.9, respectively). These results indicate that host-specific ENC value distribution characteristics were present in the LT-Ag gene and the CDS of the domain regions contained in the LT-Ag gene. Whereas avian PyV and fish PyV included significant codon diversity, mammalian viruses belonging to Groups M, P, and H exhibited conservative and host-specific evolution of codon usage bias (Table 4, Fig. 3). Genetic variability, which was estimated by measuring the average number of pairwise nucleotide differences (k) and nucleotide diversity (π), was highest for the LT-Ag gene (k = 910.333, π = 0.54939) and helicase domain (k = 210, π = 0.46358) in Group F (Table 5).

Fig. 3.

The range of ENC values of the LT-Ag genes and two functional domains. The cross (×) indicates the mean ENC value, and the dot (•) indicates the minimum/maximum ENC value of the LT-Ag genes and two domains within LT-Ag. Each group, which we classified by host, was composed of 9 (Group A), 3 (Group F), 13 (Group H), 36 (Group M), and 25 (Group P) nucleotide sequence data of LT-Ag genes and helicase domains. DnaJ domains were not identified in 32 protein sequences, including 3 fish PyVs; thus, a total of 54 sequence data were used for the analysis

Table 5.

Nucleotide diversity, selection pressure, and neutrality tests of the LT-Ag genes and two domains of the PyV groups

| Genetic variability | Neutrality tests | Selection pressure | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Group | m | n | S | η | k | π | Tajima’s D | Fu and Li’s D | Fu and Li’s F | dN/dS |

| LT-Ag | All | 86 | 944 | 837 | 2129 | 418.245 | 0.44306 | −0.04390ns | 1.45113ns | 0.96702ns | 2.163 |

| Group A | 9 | 1725 | 1283 | 2383 | 737.889 | 0.42776 | −0.82814ns | 0.0858ns | −0.15345ns | 0.282 | |

| Group F | 3 | 1657 | 1209 | 1522 | 910.333 | 0.54939 | NA | NA | NA | 0.684 | |

| Group H | 13 | 1648 | 1336 | 2725 | 725.192 | 0.44004 | −0.80590ns | 0.16114ns | −0.11521ns | 1.673 | |

| Group M | 36 | 1404 | 1205 | 2813 | 615.989 | 0.43874 | −0.35097ns | 0.89680ns | 0.54139ns | 0.523 | |

| Group P | 25 | 1602 | 1268 | 2653 | 666.147 | 0.41582 | − 0.20916ns | 0.88010ns | 0.62234ns | 0.318 | |

| DnaJ domain | All | 54 | 160 | 144 | 352 | 71.204 | 0.44503 | −0.28170ns | 1.14715ns | 0.71186ns | 0.261 |

| Group A | 9 | 162 | 119 | 214 | 68.083 | 0.42027 | −0.70347ns | 0.14282ns | −0.07065ns | 0.298 | |

| Group H | 7 | 192 | 146 | 237 | 82.143 | 0.42783 | −0.88626ns | −0.18339ns | − 0.37879ns | 0.417 | |

| Group M | 19 | 162 | 136 | 277 | 63.474 | 0.39181 | −0.83778ns | 0.31536ns | −0.03513ns | 0.289 | |

| Group P | 19 | 192 | 153 | 291 | 78.585 | 0.4093 | −0.23632ns | 0.71490ns | 0.50101ns | 0.262 | |

| Helicase domain | All | 86 | 424 | 348 | 827 | 165.867 | 0.3912 | 0.02756ns | 1.22733ns | 0.85387ns | 0.316 |

| Group A | 9 | 471 | 288 | 499 | 159.361 | 0.33835 | −0.68870ns | 0.11803ns | −0.08782ns | 0.150 | |

| Group F | 3 | 453 | 285 | 345 | 210 | 0.46358 | NA | NA | NA | 0.379 | |

| Group H | 13 | 477 | 326 | 632 | 174.667 | 0.36618 | −0.65740ns | 0.21440ns | −0.02451ns | 0.260 | |

| Group M | 36 | 447 | 346 | 738 | 170.876 | 0.38227 | −0.15171ns | 0.86494ns | 0.60171ns | 0.503 | |

| Group P | 25 | 471 | 317 | 619 | 161.56 | 0.34301 | −0.05815ns | 0.97206ns | 0.75361ns | 0.142 | |

m, number of sequences used; n, total number of sites (excluding sites with gaps/missing data); S, number of segregating sites; η, total number of mutations; k, average number of pairwise nucleotide differences; π, nucleotide diversity; dS, average number of synonymous substitutions per site; dN, average number of non-synonymous substitutions per site; NA, not available due to limited sequences for analysis of the gene-specific sequence dataset; ns, not significant

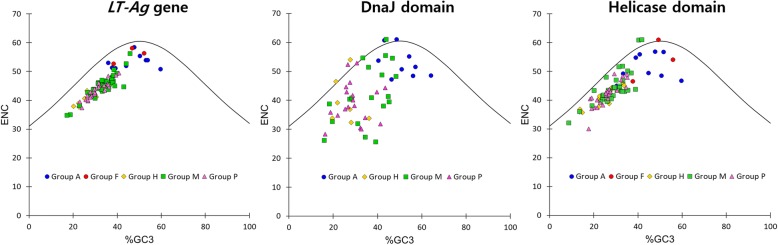

The NC plot showing the relationship between ENC and GC3 revealed that the results from excluding eight DnaJ domains and three helicase domain CDS, while including the entire LT-Ag gene CDS were plotted under the expected ENC curve, suggesting that the codon usage was biased. This pattern was observed overall, regardless of group. However, in the LT-Ag gene sequence analysis, Groups A and F viruses exhibited more diverse codon usage, as they were located closer to the expected ENC curve. However, Groups M, P, and H had relatively more biased codon usage (Fig. 4). This codon usage pattern was consistent with the characteristics of the avian virus, which is known to have a broad host range, as opposed to the mammalian virus, with a narrow host range [7].

Fig. 4.

The relationship between ENC and GC3 (NC plot). ENC were plotted against GC content at the third codon position. The expected ENC from GC3 are shown as a solid line

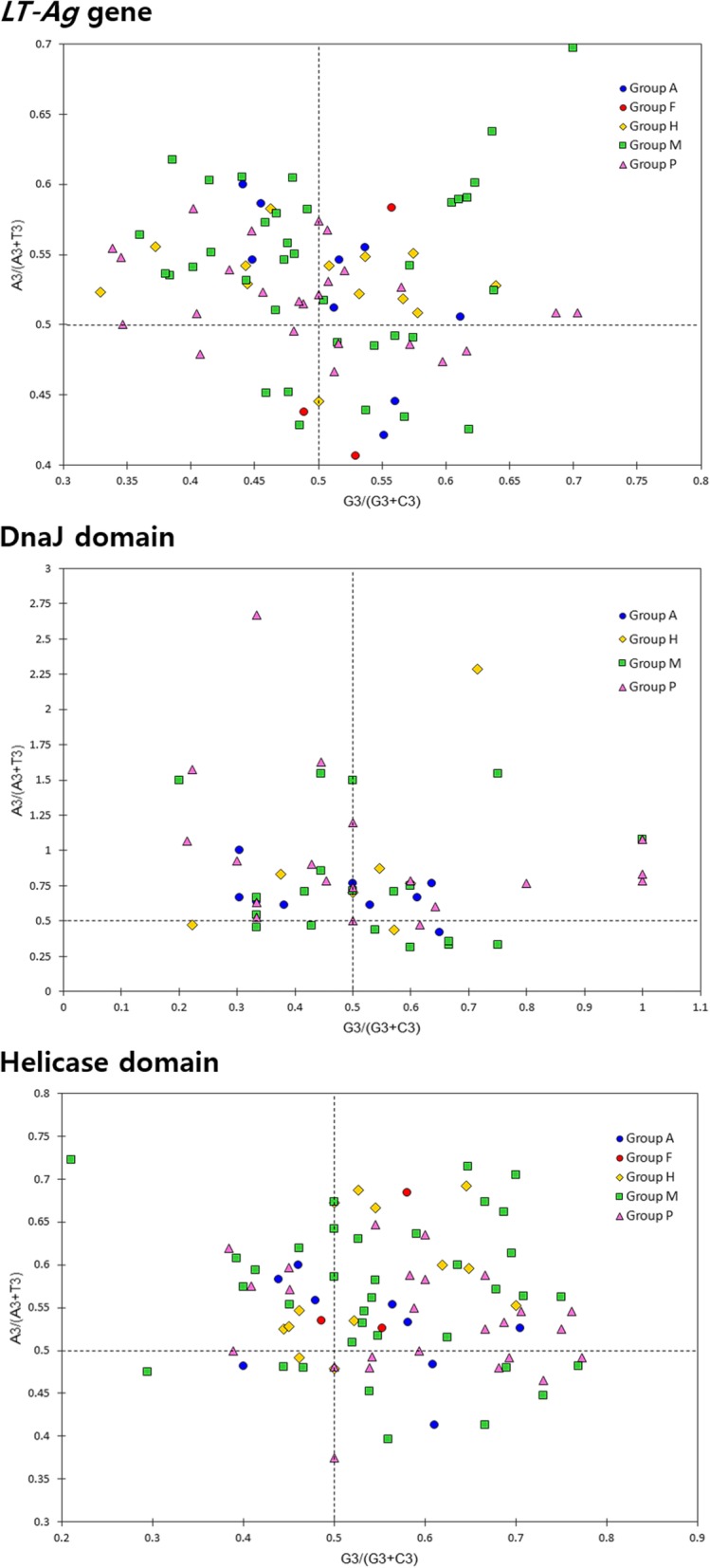

PR2 and neutrality analyses were performed to investigate the effects of mutation pressure and natural selection on codon usage patterns of LT-Ag CDS of PyVs. After analyzing the relationship between AT and GC contents, A was used at the third codon position of 65 fourfold degenerate codon families of 86 gene sequences at a frequency higher than or equal to T; in the fourfold degenerate codon families of 45 gene sequences, G was used at a frequency equal to or greater than C. In the DnaJ domain, A was used at the third codon position of 43 fourfold degenerate codon families of 54 gene sequences at a frequency higher than or equal to T, and in the fourfold degenerate codon families of 31 gene sequences, G was used at a frequency greater than or equal to C. In the helicase domain, A was used at the third codon position of 64 fourfold degenerate codon families of 86 sequences at a frequency higher than or equal to T, and in the fourfold degenerate codon families of 63 gene sequences, G was used at a frequency equal to or greater than C. When the distances and directions of all plot dots from the plot coordinate (0.5, 0.5) were examined, there were no significant differences between groups, and various distance distributions and similar directionality (T → A) were detected. Therefore, the bias shown in the PR2 plot results from the difference in the usage frequencies of T and A, which is generally shown in the fourfold degenerate codon families of the sequences encoding the LT-Ag genes of the PyVs and the domains contained therein, rather than differences between the groups. Unequal use of these nucleotides may imply the overlapping effect of natural selection and mutation pressure on codon selection in the corresponding gene sequences (Fig. 5). Negative values of Tajima’s D, Fu and Li’s D*, and Fu and Li’s F* were obtained for the DnaJ domain in Group H, indicating an excess of low-frequency polymorphisms caused by background selection, genetic hitchhiking, or population expansions [79, 87, 88]. The values of Tajima’s D, Fu and Li’s D*, and Fu and Li’s F* for the helicase domain in the overall population were positive, which arose from an excess of intermediate-frequency alleles and can result from population bottlenecks, structure, or balancing selection [87]. However, the P-values for Tajima’s D, Fu and Li’s D*, and Fu and Li’s F* tests were not significant (P > 0.10) in all cases (Table 5), indicating that the results were less convincing; it is also plausible that purifying selection is acting on each of the viral groups. It was impossible to do these statistical tests for the DnaJ domain in Group F, as the analysis using DnaSP software requires at least four sequences [71].

Fig. 5.

PR2-bias plot analysis. A3/(A3 + T3) were plotted against G3/(G3 + C3). The A3 content is greater than T3, and the G3 content is greater than C3 in CDS of LT-Ag genes, DnaJ domains, and helicase domains from different host species. These LT-Ag genes and their retained domains prefer to use the T-end and G-end codons

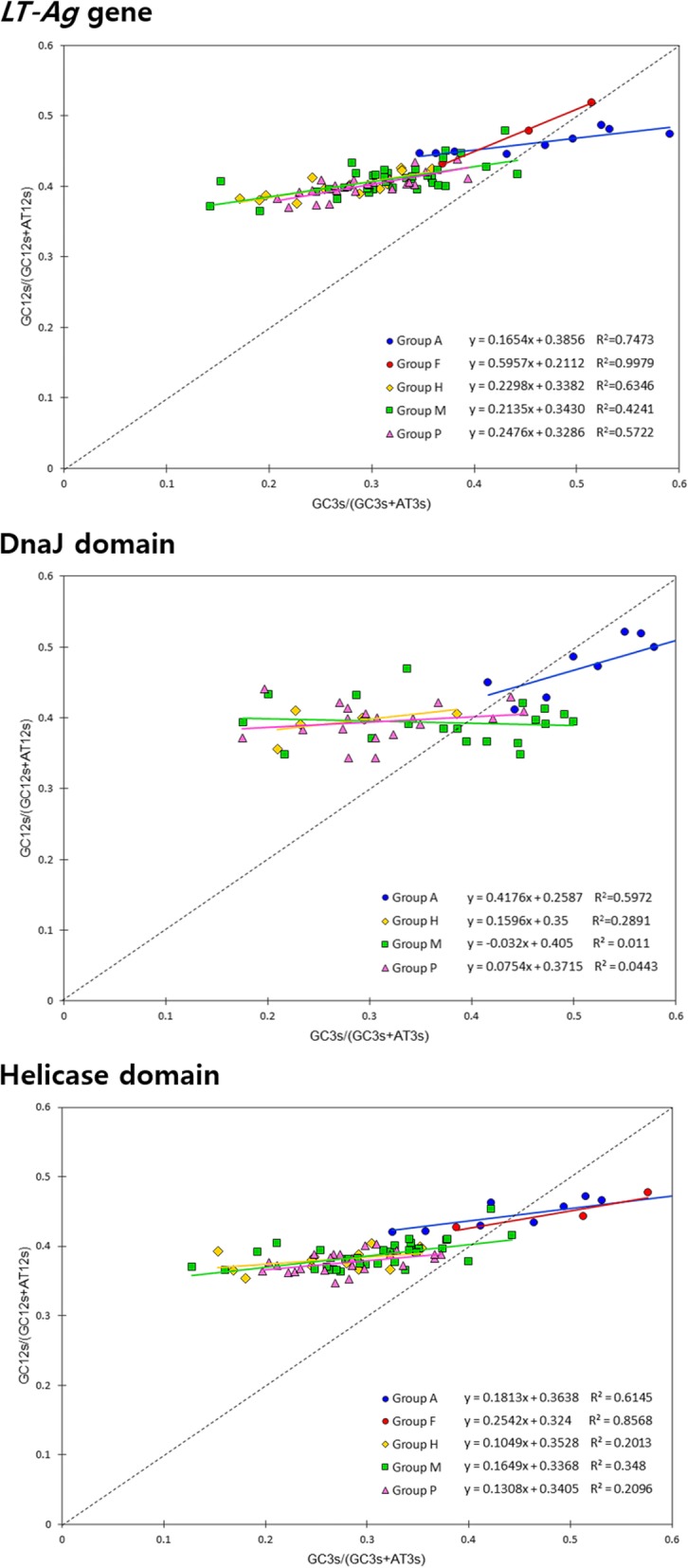

In terms of the evolution of synonymous codon usage, mutation pressure either increases or decreases the GC content, and the GC content (GC3) at the third codon position expresses the most neutral nucleotides that make an important contribution to directional mutation pressure [76]. Thus, the effect of directional mutation and natural selection on the codon usage pattern of the PyV’s LT-Ag gene CDS isolated from different host species and two functional domains contained in the gene was estimated based on the neutrality plot. Neutrality analysis also confirmed that mutation pressure and natural selection both affected the codon usage bias of the LT-Ag gene CDS. The analyzed genes showed a narrow GC12 distribution and a wide GC3 distribution, indicating a significant correlation (r = 0.715, p < 0.0001). This may indicate high mutation bias or highly variable GC contents in the corresponding genes. When comparing the gradients of the regression lines for each group, Group F had the largest regression slope of 0.5957, followed by Groups P (0.2476), H (0.2298), M (0.2135), and A (0.1654). This indicates that the relative neutrality (directional mutation pressure) of the viruses belonging to each group was 59.57, 24.76, 22.98, 21.35, and 16.54%, respectively. Therefore, the contribution of natural selection to the codon usage pattern of each group was higher in the order of Groups A (83.46%), M (78.65%), H (77.02%), and P (75.24%). Group F was less affected by natural selection than the other groups (40.43%). A comparison of the gradients of the regression lines of all groups based on our neutrality analysis of the helicase domain revealed that the contribution of natural selection to the codon usage pattern of each group was, in descending order, Groups H (89.51%), P (86.92%), M (83.51%), and A (81.87%). Group F was less affected by natural selection than the other groups were (74.58%). In the case of the DnaJ domain, natural selection had a relatively low effect on Group A (58.24%), whereas its effect on other groups (Groups H, M, and P) was 80% or higher. Thus, the effect of the relative neutrality (directional mutation pressure) was found to be large (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Neutrality plot of GC12 vs. GC3. GC12 were plotted against GC3. GC12 is the ordinate, and GC3 is the abscissa, so each point in the figure represents one LT-Ag gene from a different host organism. The neutrality plotting results for LT-Ag genes show that the distribution of GC12 is relatively concentrated, GC3 is during 0.171 (Delphinus delphis [short-beaked common dolphin]) to 0.596 (Pygoscelis adeliae [Adélie penguin]). Neutrality plotting results for two functional domains also show that the distribution of GC12 is relatively concentrated, while GC3 is incompactly dispersed in the range of 0.175 (Pongo pygmaeus [Bornean orangutan]) to 0.646 (Pygoscelis adeliae [Adélie penguin]) for DnaJ domains and 0.128 (Delphinus delphis [short-beaked common dolphin]) to 0.606 (Pygoscelis adeliae [Adélie penguin]) for helicase domains

Variation in RSCU value and codon usage preference

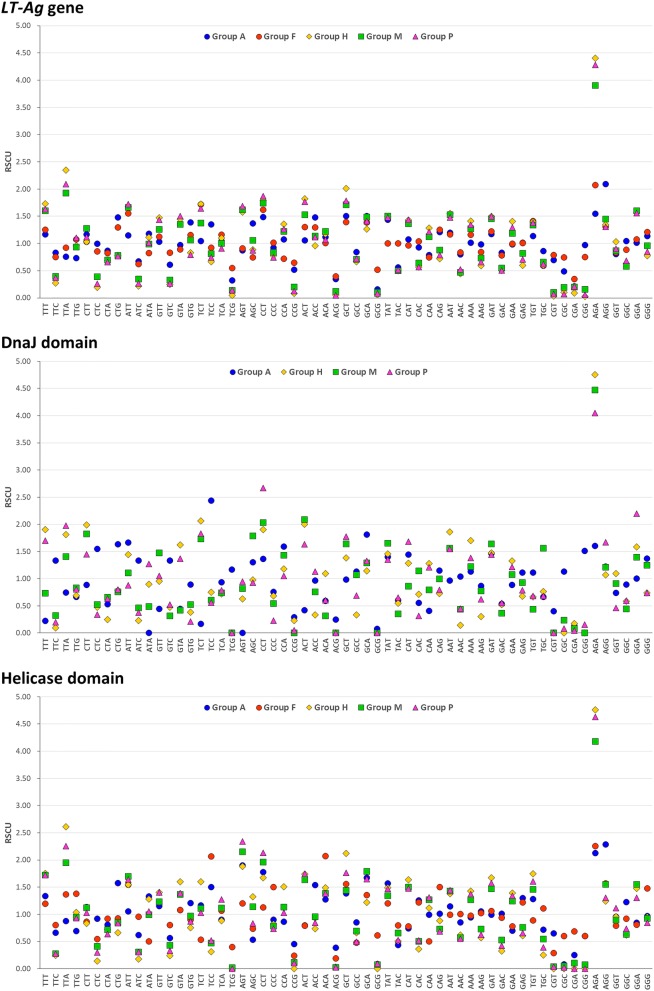

We calculated the RSCU values reflecting the codon preference in the LT-Ag genes of PyVs and analyzed their distribution pattern by group (Fig. 7) to compare them in terms of their host species (Fig. 8). First, the total mean RSCU values of the LT-Ag gene CDS in 86 species were calculated. The mean RSCU values for TTA (leu), ATT (ile), CCT (pro), GCT (ala), and AGA (arg) were 1.88, 1.62, 1.76, 1.74, and 3.78, respectively. Thus, they were over-represented codons. When the distribution pattern for each group was examined, the differences in codon usage preference among the mammalian viruses belonging to Groups H, M, and P were not significant. The difference between Groups A and F and the three groups of avian and fish viruses was relatively large. When the mean RSCU values of each group were compared, Groups H, M, and P had mean RSCU values of 1.6 or higher in codon TTT (phe), TTA (leu), ATT (ile), and GCT (ala), differing from Groups A and F. Codon AGA (arg) exhibited the largest difference in codon usage preference among the groups, and the mean RSCU value for each group was 1.55 (Froup A), 2.07 (F), 4.40 (H), 3.90 (M), and 4.28 (P). The color distribution according to the group or host species in Fig. 8 confirms such differences. Based on the analysis of each domain, the mean RSCU values of CCT (pro), ACT (thr), AGA (arg), and GGA (gly) were 2.13, 1.64, 3.88, and 1.64, respectively, in terms of the 54 DnaJ domain CDS. Thus, they were over-represented codons. When we compared the mean RSCU values of each group, Groups H, M, and P exhibited values of 1.6 or higher in codon TCT (ser), CCT (pro), and ACT (thr), showing differences from Group A. The total mean RSCU values for 86 helicase domain CDS were 1.66, 2.00, 2.09, 1.95, 1.70, and 4.12 for TTT (phe), TTA (leu), AGT (ser), CCT (pro), GCT (ala), and AGA (arg), respectively, indicating over-represented codons. When the mean RSCU values of the groups were compared, Groups H, M, and P had values greater than 1.6 in codon TTT (phe), TTA (leu), and ACT (thr), differing from Groups A and F. The codons AGT (ser) and CCT (pro) had values greater than 1.6 in all groups except Group F. Similar to the LT-Ag gene CDS, the greatest difference in codon usage preference between the groups was detected in the case of codon AGA (arg) in the two functional domains. The mean RSCU values for each group were 1.6 (Group A), 4.76 (H), 4.47 (M), and 4.05 (P) in the DnaJ domain and 2.13 (Group A), 2.26 (F), 4.76 (H), 4.18 (M), and 4.63 (P) in the helicase domain.

Fig. 7.

RSCU analysis of PyVs. There is variation in the differences between the codon preferences of the five groups in terms of the LT-Ag genes. We can see that there are relatively large differences among groups in the RSCU values of specific codons, such as codon AGA(arg) and TTA(leu)

Fig. 8.

Difference in RSCU values of 86 PyVs. Respective RSCU of the 86 LT-Ag coding genes, 54 DnaJ domain coding sequences, and 86 helicase coding sequences. All RSCU values are shown in the chromaticity diagram via chromaticity co-ordinates. The chrominance difference enables visual comparison of large data sets with various host species

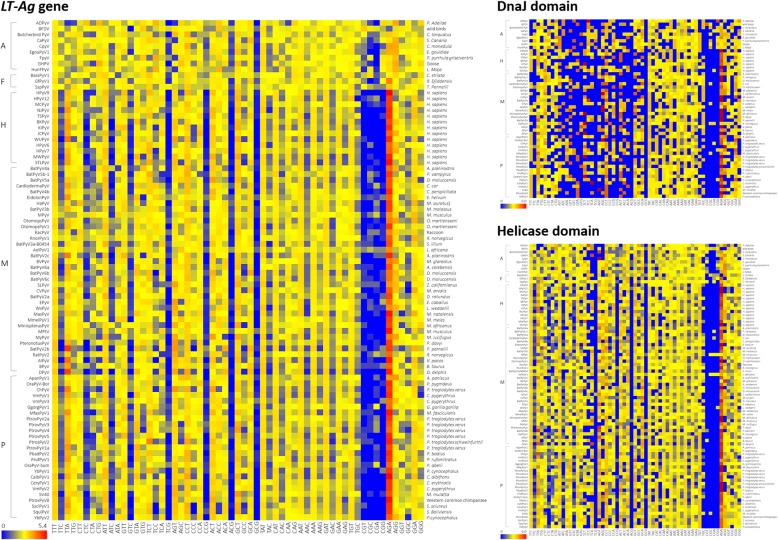

A preference for a particular codon is a common evolutionary phenomenon, reflecting the evolution of the biological group and carrying important meaning as a tool for explaining basic biological phenomena at the molecular level. RSCU analysis is one of the most important methods for analyzing synonymous codons in various organisms, including viruses. As shown in Fig. 7 and Fig. 8, the RSCU values of 86 LT-Ag genes differed by group and host, and there were differences in preference for codon usage. In Table 6 and Fig. 9, the results of comparing the mean RSCU and codon frequencies between different viral groups with their respective host species are seen more clearly. Notably, the greatest difference in codon usage preference between genes and groups was detected in codon AGA (arg) of all datasets. The CAI was calculated to compare the adaptability of synonymous codon usage. In this study, the CAI value of H. sapiens was used as the reference dataset. The range of the total value was 0.690–0.790, and the mean ± standard deviation was 0.74 ± 0.02. The CAI values did not vary significantly between groups, and PyVs derived from various host species generally had high similarity to the reference data in terms of both codon usage pattern and expression level. Thus, regardless of the host species, they showed relatively high adaptability in human hosts.

Table 6.

RSCU distances of the host pairs calculated from the RSCU values for the abundant codons (RSCU ≥1.6) in the LT-Ag genes and two domains of PyVs

| Region | Host pairs | RSCU distances witin host pairs for abundant codons (RSCU≥1.6) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTT | TTA | ATT | TCT | CCT | ACT | GCT | AGA | AGG | Avg. | ||

| LT-Ag | A–F | 0.082 | 0.165b | 0.406 | 0.676 | 0.134 | 0.244 | 0.111 | 0.521 | 0.780 | 0.346 |

| A–H | 0.558a | 1.593a | 0.522 | 0.680a | 0.301 | 0.764a | 0.507 | 2.855a | 0.749 | 0.948 | |

| A–M | 0.435 | 1.169 | 0.512 | 0.334 | 0.257 | 0.471 | 0.204 | 2.355 | 0.645 | 0.709 | |

| A–P | 0.460 | 1.335 | 0.572a | 0.601 | 0.385a | 0.707 | 0.279 | 2.731 | 0.785a | 0.873 | |

| F–H | 0.477 | 1.428 | 0.117 | 0.004b | 0.167 | 0.520 | 0.618a | 2.335 | 0.032 | 0.633 | |

| F–M | 0.353 | 1.004 | 0.107 | 0.342 | 0.123 | 0.227 | 0.315 | 1.834 | 0.135 | 0.493 | |

| F–P | 0.378 | 1.170 | 0.166 | 0.074 | 0.251 | 0.463 | 0.389 | 2.210 | 0.005b | 0.567 | |

| H–M | 0.123 | 0.424 | 0.010b | 0.346 | 0.044b | 0.293 | 0.303 | 0.501 | 0.104 | 0.239 | |

| H–P | 0.098 | 0.259 | 0.050 | 0.079 | 0.083 | 0.057b | 0.228 | 0.125b | 0.036 | 0.113 | |

| M–P | 0.025b | 0.166 | 0.060 | 0.267 | 0.127 | 0.236 | 0.075b | 0.376 | 0.140 | 0.164 | |

| DnaJ | A–H | 1.682a | 1.064 | 0.224b | 1.896a | 0.542 | 1.580 | 0.395 | 3.157a | 0.151 | 1.188 |

| A–M | 0.511 | 0.662 | 0.561 | 1.566 | 0.669 | 1.668a | 0.651 | 2.874 | 0.012b | 1.019 | |

| A–P | 1.476 | 1.230a | 0.788a | 1.664 | 1.304a | 1.212 | 0.786a | 2.447 | 0.449 | 1.262 | |

| H–M | 1.171 | 0.402 | 0.338 | 0.330 | 0.127b | 0.088b | 0.256 | 0.283b | 0.139 | 0.348 | |

| H–P | 0.207b | 0.166b | 0.564 | 0.232 | 0.762 | 0.368 | 0.391 | 0.711 | 0.600a | 0.444 | |

| M–P | 0.965 | 0.568 | 0.226 | 0.098b | 0.635 | 0.456 | 0.135b | 0.427 | 0.461 | 0.441 | |

| Helicase | A–F | 0.142 | 0.494 | 0.489 | 0.633 | 0.653 | 0.003b | 0.168 | 0.128 | 0.716 | 0.381 |

| A–H | 0.416 | 1.739a | 0.492 | 0.435 | 0.106b | 0.946 | 0.735a | 2.628a | 1.044a | 0.949 | |

| A–M | 0.386 | 1.074 | 0.647a | 0.059 | 0.184 | 0.837 | 0.053b | 2.052 | 0.737 | 0.670 | |

| A–P | 0.363 | 1.349 | 0.594 | 0.049 | 0.445 | 1.013 | 0.599 | 2.502 | 0.949 | 0.873 | |

| F–H | 0.558a | 1.245 | 0.002b | 1.069a | 0.546 | 0.949 | 0.568 | 2.500 | 0.328 | 0.863 | |

| F–M | 0.528 | 0.580 | 0.158 | 0.574 | 0.836 | 0.840 | 0.115 | 1.924 | 0.021b | 0.620 | |

| F–P | 0.505 | 0.854 | 0.104 | 0.585 | 1.098a | 1.016a | 0.431 | 2.374 | 0.232 | 0.800 | |

| H–M | 0.029 | 0.665 | 0.155 | 0.495 | 0.290 | 0.110 | 0.682 | 0.576 | 0.307 | 0.368 | |

| H–P | 0.053 | 0.390 | 0.102 | 0.484 | 0.552 | 0.066 | 0.136 | 0.126b | 0.096 | 0.223 | |

| M–P | 0.024b | 0.274b | 0.053 | 0.011b | 0.262 | 0.176 | 0.546 | 0.450 | 0.212 | 0.223 | |

A–F avian–fish, A–H avian–human, A–M avian–non-primate mammals, A–P avian–non-human primate, F–H fish–human, F–M fish–non-primate mammals, F–P fish–non-human primate, H–M human–non-primate mammals, H–P human–non-human primate, M–P non-primate mammals–non-human primate; alargest RSCU distances among the host pairs for the corresponding codon; bsmallest RSCU distances among the host pairs for the corresponding codon

Fig. 9.

Mean RSCU distances of the host pairs calculated from the RSCU values for the abundant codons (RSCU ≥1.6) in the LT-Ag genes and two domains of PyVs

COA results for RSCU values

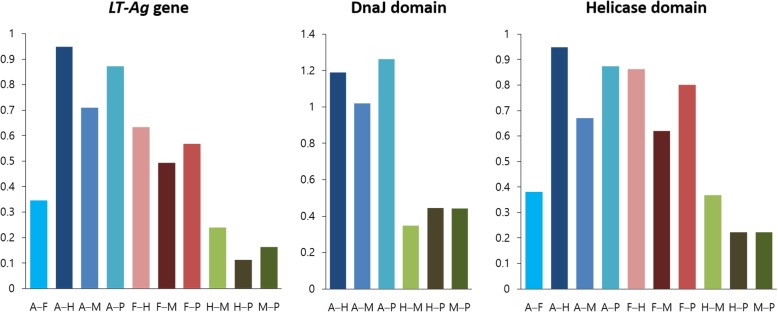

We carried out COA using the RSCU value to identify trends associated with differences in codon preference among the gene sequences used in this study. In the COA-RSCUs generated in this study, axis 1 (y) and axis 2 (x) accounted for 74.01 and 14.96% of the total mutations, respectively. Figure 10 shows the COA results for over-represented codons, with RSCU values greater than or equal to 1.6, calculated from 86 LT-Ag gene CDS. Scatter plots B–F show high similarity in terms of the distribution patterns of the plot dots in the range (− 0.2 to + 0.3, − 0.4 to ~ + 0.4) in all groups. Specifically, two dots plotted outside the corresponding range were identified as LT-Ag genes of BFDV and Adélie penguin PyV (ADPyV). Thus, they were presumed to indicate mutations in codon usage patterns. These are all avian PyVs belonging to Group A, and host species are wild birds and Pygoscelis adeliae (Adélie penguin), respectively (Fig. 10). The distances between the genes in the plots shown in Fig. 10 reflects the dissimilarity in the RSCU with respect to axis 1 and axis 2. These results explain a significant portion (74.01%) of the variation in codon usage in 86 LT-Ag genes, so natural selection may have played a very important role.

Fig. 10.

Correspondence analysis results for the RSCU values of strongly preferred codons in 86 PyVs (COA-RSCU). The COA results for over-represented codons (RSCU > 1.6) for five groups are shown in scatter plots b-f for groups A, F, H, M, and P, respectively. The plot dot distribution patterns of groups A and F vs. groups H, M, and P were compared (a). Overall, the plotted dots show high similarity in terms of distribution patterns in all groups, with a scattered range (− 0.2 to + 0.3, − 0.4 to + 0.4). Specifically, two dots plotted over the range were identified as LT-Ag genes for BFDV and ADPyV, and thus they can be seen to vary in terms of codon usage patterns. They are all avian polyomaviruses belonging to group A, and host organisms are wild birds and Pygoscelis adeliae (Adélie penguin) (a)

Selection pressure

The dN/dS ratio was used to estimate the natural selection pressure acting on the LT-Ag gene. The average dN/dS values for the DnaJ and helicase domains in the overall population and in each Group (Groups A, H, M, and P for DnaJ; Groups A, F, H, M, and P for helicase) were less than 1, showing that these two functional regions experience negative selection pressure (Table 5). Similarly, negative selection pressure was estimated for LT-Ag sequence pairs within Groups A, F, M, and P, ranging from 0.282 to 0.684, while the values within the overall population and Group H exceeded 1, which suggests that human PyVs have evolved by positive selection.

Discussion

In this study, we compared the nucleotide sequences encoding all PyV-encoded LT-Ag that have been classified so far and their major domains. Of the various virus species used for analysis, avian PyVs differed significantly from mammalian PyVs in terms of nucleotide composition, ENC value, and codon usage patterns. Avian PyVs are known to cause acute and chronic diseases in various bird species (Table 3). In particular, PyV disease [19–22], which is caused by BFDV and FPyV (finch PyV) infection, and hemorrhagic nephritis and enteritis [23], which is caused by GHPV infection, are inflammatory diseases that cause high mortality in young avians. The high virulence of these avian PyVs contrasts with mammalian PyVs, which generally cause harmless, persistent infection in natural hosts with healthy immune systems. Mammalian PyVs, such as SV40, are known to induce tumors in nonpermissive host rodents after inoculation [89], which is rarely seen in avian PyV-infected birds. In general, the avian PyV’s infectious nature, destroying numerous cells in the infected organism, is considered to cause serious diseases. The cause of significant cell damage by these viruses has not yet been elucidated. However, while avian PyV infection in chicken embryonic fibroblasts causes remarkable cell damage by induction of apoptosis, SV40 infection of Vero cells mainly causes necrosis. Thus, the induction of necrosis by avian PyVs is thought to contribute to virulence through the efficient release of virus progeny and spread across the entire organism [58]. The differences in the virulences of viruses may reflect differences in the biochemical functions of LT-Ag, which were also confirmed by the genetic and evolutionary differences observed in the LT-Ag gene and domains of PyVs isolated from various hosts, based on the sequence analysis performed in this study.

Conclusions

One possible explanation for the presence or absence of specific domains or sequence motifs in the LT-Ag of various PyV species, and thus the mutations and evolutionary differences observed in these functional and structural regions, is that PyVs have evolved so that each viral protein interacts with host cell targets, and they have adapted to thrive in particular host species and cell types. They are known to interact specifically with host proteins involved in cell proliferation and gene expression regulation, have a significant association with the functional domains of LT-Ag, and vary with respect to size and composition in various virus species. Thus, even though various PyV species adopt a common survival strategy, some viral LT-Ags can target new host systems or cell types. Furthermore, the domains of LT-Ag may appear to be widely conserved, but, as indicated by the genetic and evolutionary differences observed in this study, the host function regulation mechanism of LT-Ag varies with the host species. These differences can be used to study virus–host interactions, cellular pathways, mechanisms of tumorigenesis by viral infection, and treatments for new infectious diseases. As new PyVs continue to be found in various organisms, it is necessary to conduct further studies on the mechanisms involved in host-specific toxic manifestations of PyVs, host system regulation, and cell transformation.

Acknowledgements

We’d like to thank those who made their invaluable data publicly available.

Abbreviations

- ADPyV

Adélie penguin polyomavirus

- BatPyV2c

Bat polyomavirus 2c

- BatPyV4a

Bat polyomavirus 4a

- BFDV

Budgerigar fledgling disease virus

- BKPyV

BK polyomavirus

- BPyV

Bovine polyomavirus

- CAI

Codon adaptation index

- CDS

Coding sequence

- COA

Correspondence analysis

- DPyV

Dolphin polyomavirus 1

- ENC

Effective number of codons

- FPyV

Finch polyomavirus

- GHPV

Goose hemorrhagic polyomavirus

- JCPyV

JC polyomavirus

- KIPyV

KI polyomavirus

- LT-Ag

Large tumor antigen

- MCPyV

Merkel cell polyomavirus

- ML

Maximum likelihood

- MPyV

Mouse polyomavirus

- PR2

Parity rule 2

- PyV

Polyomavirus

- RSCU

Relative synonymous codon usage

- SV40

Simian virus 40

- WUPyV

WU polyomavirus

Authors’ contributions

HS designed the study; MC collected and analyzed the data; MC and HK interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (No. 2016R1C1B2015511) and the Ministry of Education (No. 2017R1D1A1B03033413).

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials described in the manuscript are available.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Myeongji Cho and Hayeon Kim contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Myeongji Cho, Email: yummy0112@snu.ac.kr.

Hayeon Kim, Email: hykim1984@kduniv.ac.kr.

Hyeon S. Son, Phone: +82-2-880-2746, Email: hss2003@snu.ac.kr

References

- 1.Gross L. A filterable agent, recovered from Ak leukemic extracts, causing salivary gland carcinomas in C3H mice. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1953;83:414–421. doi: 10.3181/00379727-83-20376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart SE. Anatomical Record. New York: Wiley; 1953. Leukemia in mice produced by a filterable agent present in AKR leukemic tissues with notes on a sarcoma produced by the same agent; p. 532. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sweet BH, Hilleman MR. The vacuolating virus, SV 40. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1960;105:420–427. doi: 10.3181/00379727-105-26128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gardner S, Field A, Coleman D, Hulme B. New human papovavirus (BK) isolated from urine after renal transplantation. Lancet. 1971;297:1253–1257. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(71)91776-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Padgett B, Zurhein G, Walker D, Eckroade R, Dessel B. Cultivation of papova-like virus from human brain with progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy. Lancet. 1971;297:1257–1260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(71)91777-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, Moore PS. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1152586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krumbholz A, Bininda-Emonds OR, Wutzler P, Zell R. Phylogenetics, evolution, and medical importance of polyomaviruses. Infect Genet Evol. 2009;9:784–799. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moens U, Krumbholz A, Ehlers B, Zell R, Johne R, Calvignac-Spencer S, Lauber C. Biology, evolution, and medical importance of polyomaviruses: an update. Infect Genet Evol. 2017;54:18–38. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Doorslaer K. Evolution of the Papillomaviridae. Virology. 2013;445:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buck CB, Van Doorslaer K, Peretti A, Geoghegan EM, Tisza MJ, An P, Katz JP, Pipas JM, McBride AA, Camus AC, McDermott AJ, Dill JA, Delwart E, Ng TFF, Farkas K, Austin C, Kraberger S, Davison W, Pastrana DV, Varsani A. The ancient evolutionary history of polyomaviruses. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005574. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeCaprio JA, Garcea RL. A cornucopia of human polyomaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:264. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borchert S, Czech-Sioli M, Neumann F, Schmidt C, Wimmer P, Dobner T, Grundhoff A, Fischer N. High-affinity Rb binding, p53 inhibition, subcellular localization, and transformation by wild-type or tumor-derived shortened Merkel cell polyomavirus large T antigens. J Virol. 2014;88:3144–3160. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02916-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahuja D, Sáenz-Robles MT, Pipas JM. SV40 large T antigen targets multiple cellular pathways to elicit cellular transformation. Oncogene. 2005;24:7729. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shuda M, Feng H, Kwun HJ, Rosen ST, Gjoerup O, Moore PS, Chang Y. T antigen mutations are a human tumor-specific signature for Merkel cell polyomavirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105:16272–16277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806526105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Der Meijden E, Janssens RW, Lauber C, Bavinck JNB, Gorbalenya AE, Feltkamp MC. Discovery of a new human polyomavirus associated with trichodysplasia spinulosa in an immunocompromized patient. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001024. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schowalter RM, Pastrana DV, Pumphrey KA, Moyer AL, Buck CB. Merkel cell polyomavirus and two previously unknown polyomaviruses are chronically shed from human skin. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:509–515. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graffi A, Schramm T, Graffi I, Bierwolf D, Bender E. Virus-associated skin tumors of the Syrian hamster: preliminary note. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1968;40:867–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kilham L, Murphy HW. A pneumotropic virus isolated from C3H mice carrying the Bittner milk agent. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1953;82:133–137. doi: 10.3181/00379727-82-20044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernier G, Morin M, Marsolais G. A generalized inclusion body disease in the budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus) caused by a papovavirus-like agent. Avian Dis. 1981;25:1083–1092. doi: 10.2307/1590087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bozeman LH, Davis RB, Gaudry D, Lukert PD, Fletcher OJ, Dykstra MJ. Characterization of a papovavirus isolated from fledgling budgerigars. Avian Dis. 1981;25:972–980. doi: 10.2307/1590072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johne R, Müller H. Avian polyomavirus in wild birds: genome analysis of isolates from Falconiformes and Psittaciformes. Arch Virol. 1998;143:1501–1512. doi: 10.1007/s007050050393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johne R, Wittig W, Fernández-de-Luco D, Höfle U, Müller H. Characterization of two novel polyomaviruses of birds by using multiply primed rolling-circle amplification of their genomes. J Virol. 2006;80:3523–3531. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.7.3523-3531.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guerin JL, Gelfi J, Dubois L, Vuillaume A, Boucraut-Baralon C, Pingret JL. A novel polyomavirus (goose hemorrhagic polyomavirus) is the agent of hemorrhagic nephritis enteritis of geese. J Virol. 2000;74:4523–4529. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.10.4523-4529.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fagrouch Z, Sarwari R, Lavergne A, Delaval M, De Thoisy B, Lacoste V, Verschoor EJ. Novel polyomaviruses in south American bats and their relationship to other members of the family Polyomaviridae. J Gen Virol. 2012;93:2652–2657. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.044149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scuda N, Madinda NF, Akoua-Koffi C, Adjogoua EV, Wevers D, Hofmann J, Cameron KN, Leendertz SAJ, Couacy-Hymann E, Robbins M, Boesch C, Jarvis MA, Moens U, Mugisha L, Calvignac-Spencer S, Leendertz FH, Ehlers B. Novel polyomaviruses of nonhuman primates: genetic and serological predictors for the existence of multiple unknown polyomaviruses within the human population. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003429. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi S, Sasaki M, Nakao R, Setiyono A, Handharyani E, Orba Y, Rahmadani I, Taha S, Adiani S, Subangkit M, Nakamura I, Kimura T, Sawa H. Detection of novel polyomaviruses in fruit bats in Indonesia. Arch Virol. 2015;160:1075–1082. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2349-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Groenewoud MJ, Fagrouch Z, van Gessel S, Niphuis H, Bulavaite A, Warren KS, Heeney JL, Verschoor EJ. Characterization of novel polyomaviruses from Bornean and Sumatran orang-utans. J Gen Virol. 2010;91:653–658. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.017673-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tao Y, Shi M, Conrardy C, Kuzmin IV, Recuenco S, Agwanda B, Alvarez DA, Ellison JA, Gilbert AT, Moran D, Niezgoda M, Lindblade KA, Holmes EC, Breiman RF, Rupprecht CE, Tong S. Discovery of diverse polyomaviruses in bats and the evolutionary history of the Polyomaviridae. J Gen Virol. 2013;94:738–748. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.047928-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deuzing I, Fagrouch Z, Groenewoud MJ, Niphuis H, Kondova I, Bogers W, Verschoor EJ. Detection and characterization of two chimpanzee polyomavirus genotypes from different subspecies. Virol J. 2010;7:347. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamaguchi H, Kobayashi S, Ishii A, Ogawa H, Nakamura I, Moonga L, Hang’ombe BM, Mweene AS, Thomas Y, Kimura T, Sawa H, Orba Y. Identification of a novel polyomavirus from vervet monkeys in Zambia. J Gen Virol. 2013;94:1357–1364. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.050740-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leendertz FH, Scuda N, Cameron KN, Kidega T, Zuberbühler K, Leendertz SAJ, Couacy-Hymann E, Boesch C, Calvignac S, Ehlers B. African great apes are naturally infected with polyomaviruses closely related to Merkel cell polyomavirus. J Virol. 2011;85:916–924. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01585-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]