Abstract

Background

The association between serum vitamin D level and vertebral fracture (VFx) remains controversial. The purpose of this study was to determine whether serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25(OH)D) level is associated with osteoporotic thoracolumbar junction VFx in elderly patients.

Material/Methods

From Jan 2013 to Dec 2017, this retrospective case-control study included 534 patients with primary osteoporotic thoracolumbar junction VFx (T10–L2) and 569 elderly orthopedic patients with back pain (without osteoporotic VFx) as controls. Serum 25(OH)D levels were measured and the association with osteoporotic VFx was analyzed. Other clinical data, including BMI, comorbidities, and bone mineral density (BMD), were also collected and compared between these 2 groups.

Results

It was shown that 25(OH)D levels were significantly lower in patients with T10–L2 VFx than in control patients. Among 534 VFx patients, 417 (78.1%) patients showed grade 2–3 fracture. Serum 25(OH)D levels were significantly related to affected vertebral numbers and VFx severities. The VFx risk was 28% lower (OR=0.72, 95% CI 0.62–0.83) per increased SD in serum 25(OH)D. Compared with the 1st quartile (mean 25(OH)D: 29.67±6.18 nmol/L), the VFx risk was significantly lower in the 3rd (mean 25(OH)D: 60.91±5.12nmol/L) and 4th quartiles (mean 25(OH)D: 103.3±44.21nmol/L), but not in the 2nd quartile (mean 25(OH)D: 45.40±3.95 nmol/L). In contrast, the VFx risk was significantly increased in the 1st quartile (OR=1.87, 95% CI 1.42–2.45) compared with the 2nd–4th quartiles.

Conclusions

Vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency was associated with risk of osteoporotic thoracolumbar junction vertebral fractures in elderly patients.

MeSH Keywords: Case-Control Studies, Osteoporosis, Spinal Fractures, Vitamin D Deficiency

Background

Epidemiological studies have shown that vitamin D deficiency is a common nutritional disorder, especially in the elderly population [1]. Vitamin D plays an important role in increasing the intestinal absorption of calcium and phosphorus and thus helps to maintain a healthy musculoskeletal system [2]. Its deficiency can induce secondary hyperparathyroidism, leading to higher bone remodeling, increased osteoclastic activity, and consequently reduced bone strength [1–3].

Vitamin D insufficiency has been proven as a risk factor of hip fractures, while sufficient supplements of vitamin D plus calcium result in a reduction of hip fracture risk [4–7]. However, the association between serum vitamin D level and osteoporotic thoracolumbar vertebral fracture (VFx) remains controversial. Some studies reported there was no significant association between serum vitamin D level and osteoporotic thoracolumbar VFx [8–10]. Recently, 2 systematic reviews and meta-analysis based on randomized control trials also demonstrated that vitamin D supplementation alone or with calcium was not associated with reduced fracture incidence among community-dwelling adults [11,12]. In contrast, Maier et al. [13] reported that vitamin D insufficiency was a risk factor for fragile VFx, which was further supported by Zafeiris et al. [14], who found that hypovitaminosis D was a risk factor for VFx following kyphoplasty.

Osteoporotic thoracolumbar VFx, which frequently occurs at the thoracolumbar junction, are common diseases in elderly patients due to site-specific loading patterns [15]. However, few studies have focused on the relationship between serum vitamin D and osteoporotic VFx at the thoracolumbar junction region. The purpose of this study was to determine whether serum level of 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25(OH)D) is associated with primary osteoporotic thoracolumbar VFx (T10~L2 vertebrae) in elderly patients.

Material and Methods

This was a retrospective, single-center, case-control study. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board and ethics committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, and informed consent were obtained from all included patients.

From Jan 2013 to Dec 2017, a consecutive series of patients admitted with osteoporotic vertebral fractures (VFx) were retrospectively assessed for eligibility. Enrolled VFx patients (≥50 years old) were diagnosed as primary osteoporotic VFx at thoracolumbar junction (T10–L2) confirmed by subsequent X-ray images and BMD examination. Their serum 25(OH)D levels were measured during hospitalization. In general, the mean age at natural menopause is approximately 49 years old for Chinese women [16,17]. Persons ≥50 years old with back pain were usually subjected to spine X-ray, BMD, and serum 25(OH)D test, and these patients without VFx were included as controls in this study.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: Patients with a high-energy traumatic VFx or a VFx beyond T10–L2 vertebrae; Patients with secondary osteoporosis or other diseases which could affect bone metabolism; Patients with a history of malignancy, severe hepatic diseases (serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) >3 times upper limit) or renal diseases (serum creatinine (Cr) >133 mmol/L), gastrectomy or intestinal resection; and Patients who had regularly been receiving vitamin D, calcium, or corticosteroids treatment.

Clinical characteristics were collected by reviewing the electronic medical records or by telephone follow-up. These characteristics included sex, age, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), hospitalization date, and history of medication and comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, liver disease, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid disease) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the included patients (n=1103).

| Variables | VFx | Control | P-value | P-adjusted* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients n (%) | 534 (48.4) | 569 (51.6) | – | – |

| Female n (%) | 426 (79.8) | 434 (76.3) | 0.168 | – |

| Age (years) | 68.05±9.72 | 66.84±9.99 | 0.120 | – |

| Height (cm) | 155.64±8.29 | 158.10±7.36 | <0.001 | – |

| Weight (kg) | 54.27±10.35 | 57.09±10.38 | <0.001 | – |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.81±3.55 | 22.58±3.66 | <0.001 | – |

| Hypertension n (%) | 230 (43.1) | 198 (34.8) | 0.018 | – |

| Cardiovascular disease n (%) | 75 (14.0) | 74 (13.0) | 0.546 | – |

| Pulmonary disease n (%) | 69 (12.9) | 84 (14.8) | 0.409 | – |

| Hepatic disease n (%) | 53 (10.9) | 106 (18.6) | <0.001 | – |

| Diabetes mellitus n (%) | 92 (17.2) | 94 (16.5) | 0.577 | – |

| Rheumatoid disease n (%) | 65 (12.2) | 260 (18.7) | <0.001 | – |

| 25(OH)D (nmol/L) | 54.53±28.11 | 64.56±40.90 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| Season | ||||

| Summer n (%) | 138 (25.8) | 127 (22.3) | ||

| Winter n (%) | 117 (21.9) | 125 (22.0) | 0.386 | 0.089 |

| Serum calcium (mmol/L) | 2.41±2.71 | 2.30±0.14 | 0.343 | 0.728 |

| Lumbar spine (M±SD) | ||||

| BMD (g/cm2) | 0.65±0.14 | 0.79±0.17 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| T-score | −3.67±1.09 | −2.38±1.48 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Osteoporosis n(%) | 463 (86.7) | 292 (51.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Total hip (M±SD) | ||||

| BMD (g/cm2) | 0.66±0.19 | 0.79±0.15 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| T-score | −2.28±1.12 | −1.35±1.16 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Osteoporosis n (%) | 226 (42.3) | 95 (16.7) | <0.001 | 0.041 |

VFx – vertebral fracture. Season, determined by the date of vitamin D examination: Summer, June–August; winter, December–January.

Adjusted by sex, age and BMI.

The serum 25(OH)D was measured using ELISA method by IDS EIA kit (IDS, Boldon, UK), and serum calcium was examined by HITACHI 7060 Automatic Biochemical Analyzer (Hitachi, Japan). According to clinical guidelines of China [18], the UK [19], and Australia [20], we defined serum vitamin D status as follows: deficiency (<30 nmol/L), insufficiency (30–49.9 nmol/L), and sufficiency (≥50 nmol/l).

BMD was examined at lumbar spine (L1–L4 vertebras) and hip (femoral neck and total hip) using the Hologic Discovery dual energy X-ray absorptiometry system (Hologic, Bedford, MA). According to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification system, we defined osteoporosis as T-score ≤−2.5, osteopenia as −2.5< T-score <−1, and normal as T-score ≥−1.

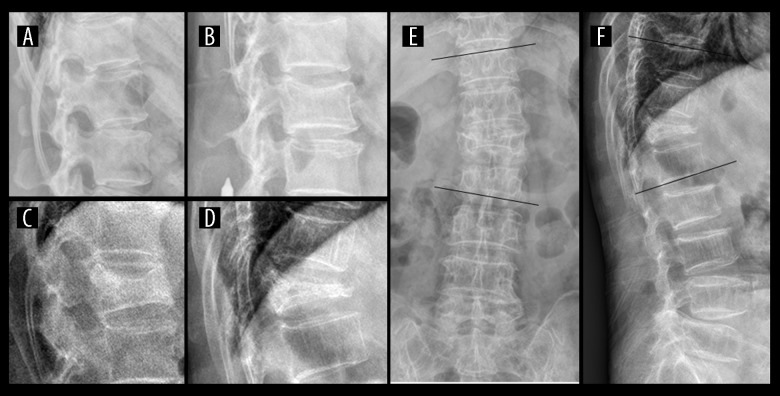

All the thoracolumbar spine X-ray films in posterior-anterior and lateral views were collected. These images were assessed for VFx and related spinal deformities (scoliosis and kyphosis). The severity of VFx was defined using Genant’s semiquantitative method [21] as follows: 1) each image was assessed by 1 experienced spine surgeon (LM Zhang with >10 years of experience) and 1 experienced skeletal radiologist (YQ Zhu with >10 years of experience) to detect VFx in thoracolumbar junction (T10–L2); 2) According to Genant’s scale, VFx severities were graded as following: a) Grade 1 (mild), a reduction in vertebral height of 20–25%; b) Grade 2 (moderate), a reduction of 26–40%; c) Grade 3 (severe), a reduction of over 40% (Figure 1). Thoracolumbar deformities were measured using Cobb method and defined as follows: scoliosiss – Cobb angle measurement greater than 10 degrees on coronal plane [22]; kyphosis – Cobb angle measurement greater than 15 degrees on sagittal plane [23] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diagnosis of osteoporotic vertebral fractures and spinal deformities in thoracolumbar junction region. (A) Grade 0, normal vertebral shape; (B) Grade 1 (mild), a reduction in vertebral height of 20–25%; (C) Grade 2 (moderate), a reduction of 26–40%; (D) Grade 3 (severe), a reduction of over 40%. (E F) Thoracolumbar scoliosis (>10°) and kyphosis (>15°) measured at T10–L2 region on coronal and sagittal plane using the Cobb method.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software package version 19.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL), and the results are presented as mean ±SD (for continuous variables) or frequencies (for categorical variables). The baseline differences between males and females were compared using the χ2 test or t test, and were further adjusted for potential confounding factors using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) or logistic regression analysis method. The association of vitamin D status with thoracolumbar VFx in females and males, fracture numbers, fracture grades, fracture locations, and spinal deformities were analyzed by using logistic regression analysis method, and they were also further adjusted for potential confounding factors. Each vitamin D measure was standardized, and the association of quartiles of serum vitamin D with VFx was analyzed by binary logistic regression analysis in different models. Finally, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was generated and the Youden index (Sensitivity+Specificity−1) was calculated for a range of cut-off scores. The cut-off value that corresponded to the highest Youden index was the optimal cut-off value for serum vitamin D that was related with VFx. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

After assessment of osteoporotic VFx in thoracolumbar junction (T10–L2), 534 consecutive patients with primary osteoporotic VFx (Mean age 68.05±9.72, 79.8% females) and 569 consecutive elderly orthopedic patients with back pain (mean age 66.84±9.99, 76.3% females) were included in this study. The enrolled patients’ demographics are shown in Table 1. The mean serum levels of 25(OH)D were significantly lower in patients with VFx than in control patients, which was 54.53±28.11 and 64.56±40.90 nmol/L, respectively (Table 1).

According to clinical guidelines [18–20], the enrolled patients were stratified into 3 groups: deficiency (<30 nmol/L), insufficiency (30–49.9 nmol/L), and sufficiency (≥50 nmol/l). There was a significant difference in vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency between 2 groups, 278 (52.1%, VFx) vs. 232 (40.8%, Control), respectively. Low vitamin D status was significantly correlated with thoracolumbar junction VFx in both females and males, but it was not significant in male patients after age and BMI adjustment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency in female and male patients.

| Female | Male | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VFx (n, %) | Control (n, %) | P-value | P-adjusted* | VFx (n, %) | Control (n, %) | P-value | P-adjusted* | ||

| 25(OH)D (nmol/L) | <30 | 61 (14.3) | 40 (9.2) | 0.004 | 0.029 | 17 (15.7) | 8 (5.9) | 0.019 | 0.055 |

| 30–49.9 | 162 (38.0) | 142 (32.7) | 38 (35.2) | 42 (31.1) | |||||

| ≥50 | 203 (47.7) | 252 (58.1) | 53 (49.1) | 85 (63.0) | |||||

VFx – vertebral fracture. P-adjusted – adjusted by age and BMI.

Among 534 patients with thoracolumbar junction VFx, most of them (344, 64.4%) only had 1 affected vertebra, but 417 (78.1%) patients showed grade 2–3 fracture (Table 3). These VFx were mostly located at T12 (35.6%) and L1 (33.7%) vertebrae. There was a significant association between serum vitamin D levels and VFx numbers or severities, even after adjustment by sex, age, and BMI (Table 3). However, when the included patients were divided into age groups per decade, the serum vitamin D levels were found to be associated with VFx only in the 60- to 80-year-old age group (Supplementary Table 1). When morphological features were assessed, serum vitamin D level was not related to fracture locations or local spinal deformities, including scoliosis and kyphosis (Table 3). Interestingly, although prevalence of osteoporosis was significantly different in the VFx and control group (Table 1), the serum vitamin D level was not associated with lumbar or total hip BMD in either group (Lumbar: p=0.88 and 0.69; Total hip: p=0.76 and 0.83; VFx and Control group, respectively) by using linear regression analysis adjusted by sex, age, and BMI.

Table 3.

Association of thoracolumbar junction vertebral fracture (VFx) or spinal deformities with serum vitamin D status.

| Variables | 25(OH)D level (nmol/L) | P-value | P-adjusteda | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 | 30–49.9 | ≥50 | |||

| Grade of VFx (n, %)b | |||||

| Normal | 48 (8.4) | 184 (32.3) | 337 (59.3) | ||

| Grade 1 | 17 (14.5) | 45 (38.5) | 55 (47.0) | ||

| Grade 2 | 23 (15.1) | 67 (44.1) | 62 (40.8) | ||

| Grade 3 | 38 (14.3) | 88 (33.2) | 139 (52.5) | 0.001 | 0.024 |

| Number of VFx (n, %) | |||||

| 0 | 48 (8.4) | 184 (32.3) | 337 (59.2) | ||

| 1 | 52 (15.1) | 133 (38.7) | 159 (46.2) | ||

| ≥2 | 26 (13.7) | 67 (35.3) | 97 (51.1) | 0.001 | 0.038 |

| Location of VFx | |||||

| T10 | 9 | 12 | 19 | ||

| T11 | 4 | 21 | 29 | ||

| T12 | 23 | 71 | 96 | ||

| L1 | 31 | 72 | 77 | ||

| L2 | 11 | 24 | 35 | 0.394 | 0.403 |

| Scoliosis of thoracolumbar spine (n)c | |||||

| − | 108 | 337 | 525 | ||

| + | 18 | 47 | 68 | 0.680 | 0.986 |

| Kyphosis of thoracolumbar spine (n)d | |||||

| − | 75 | 224 | 364 | ||

| + | 51 | 160 | 229 | 0.630 | 0.636 |

Adjusted by sex, age and BMI;

grade of VFs clarified as: Normal, absence of VFs; Grade 1–3, reduction of vertebral height of 25%, 25–40%, over 40%, respectively.

‘−’ – absence of scoliosis; ‘+’ – thoracolumbar cobb angle more than 10 degree in the coronal plane.

‘−’ – absence of kyphosis; ‘+’ – thoracolumbar cobb angle more than 15 degree in the sagittal plane.

The risk of thoracolumbar junction VFx was 28% lower (OR=0.72, 95% CI 0.62–0.83) per increased SD in 25(OH)D in the basic model (Table 4, Model 1). When adjusted by sex, age, BMI, and comorbidities, the magnitude of this protective effect decreased slightly but was still maintained (OR=0.80, 95% CI 0.68–0.93, Table 4, Model 2). To eliminate potential confounding factors, the data were further adjusted by BMD and season, which demonstrated that the protective effect of vitamin D did not decrease (OR=0.79, 95% CI 0.67–0.94, Table 4, Model 3–4), indicating the protective effect of vitamin D was independent of BMD.

Table 4.

Association of thoracolumbar junction vertebral fracture (VFx) with quartiles of serum vitamin D (OR, 95% CI).

| Variables | 25(OH)D (nmol/L) | VFx (n, Q%) | Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | Model 4d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per SD increase in 25(OH)D | 0.72 (0.62–0.83)f | 0.80 (0.68–0.93)e | 0.79 (0.67–0.94)e | 0.79 (0.67–0.94)e | ||

| Q1 | 29.67±6.18 | 168 (31.5%) | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Q2 | 45.40±3.95 | 135 (25.3%) | 0.62 (0.44–0.87)e | 0.66 (0.44–0.98)e | 0.70 (0.46–1.07) | 0.70 (0.46–1.07) |

| Q3 | 60.91±5.12 | 121 (22.7%) | 0.56 (0.40–0.78)f | 0.59 (0.40–0.88)e | 0.58 (0.38–0.89)e | 0.58 (0.38–0.89)e |

| Q4 | 103.3±44.21 | 110 (20.6%) | 0.44 (0.31–0.62)f | 0.56 (0.38–0.83)e | 0.54 (0.36–0.83)e | 0.54 (0.36–0.83)e |

| P for trend | <0.001 | 0.017 | 0.021 | 0.021 | ||

| Q2, Q3, Q4 | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | ||

| Q1 | 1.87 (1.42–2.45)f | 1.66 (1.20–2.30)e | 1.65 (1.17–2.32)e | 1.65 (1.17–2.32)e |

OR – odd ratio. CI – confidence interval. Q – quartile of serum 25(OH)D.

Model 1 basic model without adjustment;

Model 2 adjusted for sex, age, BMI and comorbidities.

Model 3 adjusted for sex, age, BMI, comorbidities and lumbar spine BMD.

Model 4 adjusted for sex, age, BMI, comorbidities, lumbar spine BMD and season.

P<0.01;

P<0.001.

Data were subjected to quartile analysis. As shown in Table 4, the mean serum 25(OH)D level gradually increased from the 1st to 4th quartile: 1st quartile, deficiency; 2nd quartile, insufficiency; 3rd and 4th quartiles, sufficiency. The VFx risk was lower in those patients from the 2nd to 4th quartiles than that from the 1st quartile in both basic and adjusted models; however, it was only significant in the 3rd and 4th quartiles, but not in the 2nd quartile, indicating that serum vitamin D above 50 nmol/L can reduce the risk of VFx in elderly patients. To analyze the VFx risk of 1st quartile, the 2nd–4th quartiles were used as referent, showing the VFx risk increased significantly in the 1st quartile and was maintained in all adjusted models (OR=1.65, Table 4). When the analysis was limited to the 60- to 80-year-old age groups, the VFx risk further increased to more than twice (OR=2.13, Supplementary Table 2).

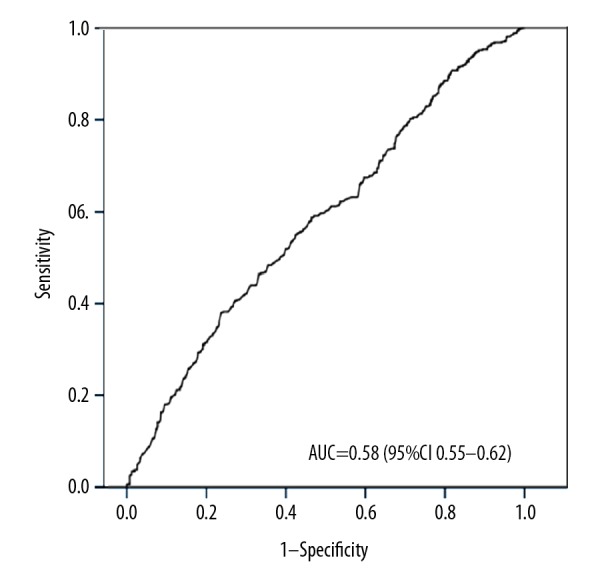

To predict the diagnostic value of vitamin D for vertebral fracture, the serum vitamin D data were subjected to ROC curve analysis. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.583 (95% CI 0.55–0.62) and the cut-off value of vitamin D was 41.15 nmol/L (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves depicting the ability of serum vitamin D to predict osteoporotic vertebral fracture. AUC – the area under ROC curve.

Discussion

We analyzed the association of serum vitamin D level with thoracolumbar junction (T10–L2) VFx in elderly osteoporotic patients. Our data showed that serum 25(OH)D level was significantly associated with thoracolumbar junction VFx, especially in elderly female patients, even after adjustment of lumbar BMD. These data suggest that low vitamin D could be an independent risk factor of thoracolumbar junction VFx.

The vitamin D insufficiency in VFx patients (52.1%, Guangzhou, latitude N 23°) was similar to that of Taiwanese postmenopausal osteoporotic patients [24] (49.5%, Taiwan, latitude N 22~25°) and Japanese postmenopausal women [9] (49.6%, Tokyo, latitude N 36°), but was significantly lower than in other studies from higher-latitude regions, such as in a German study [13] (89%, Mainz, latitude N 50°). Our data showed that vitamin D insufficiency in Control patients was 40.8%, slightly lower than that in other Asia-Pacific cities, such as cities in in Japan 53.6% [25] and in Korea 59.1% [26], but higher than in regions in lower latitudes, such as Vietnam [27]. Therefore, the prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency in this study was similar to that in other elderly populations in the same latitude.

Although low vitamin D levels is considered to be associated with hip or non-vertebral fractures, the relationship between vitamin D insufficiency and vertebral fracture is still controversial [7,11,12]. The present study, for the first time, focused on the thoracolumbar junction area where VFx occur most frequently [15]. Our data demonstrated that vitamin D insufficiency was significantly associated with thoracolumbar junction VFx in both female and male patients, but it was not significant in male patients after adjustment, which might be attributed to the sample size. These results were consistent with that from Maier et al. [13]. More importantly, our data found vitamin D insufficiency was significantly related to VFx numbers and severities, indicating that patients with low vitamin D levels are more likely to suffer more severe fracture or re-fracture, which is supported by Zafeiris et al. [14], who found that hypovitaminosis D was a risk factor of subsequent VFx after kyphoplasty. However, the association of vitamin D with VFx was limited to 60- to 80- year-old patients, and was not found in the younger or older patients in this study. Multiple risk factors are attributed to low-energy vertebral fractures, among which age is one of the most important factors [28]. A prospective study based on postmenopausal southern Chinese women showed that the prevalence of VFx increases remarkably with age (OR=1.60 for every 5-year increase); for example, 19% to 68% between 60 and 70 years to those ≥80 years, respectively [29]. Therefore, the low incidence of VFx in the 50- to 60-year-old age group and the high incidence of VFx in the ≥80-year-old age group might be attributed to the lack of an association between vitamin D and VFx in this study. However, well-control prospective studies are needed to verify our findings.

Bone loss and reduced bone strength are major causes of osteoporotic fractures in the elderly [30,31]. Interestingly, our study showed that serum vitamin D level was not related to BMD, and the reason for this phenomenon is still unknown. Vitamin D deficiency has been associated with muscle weakness and increased falling risk in elderly people [32,33], and supplementation of vitamin D reduced this risk and prevented fragile fractures [34,35]. In the present study, low vitamin D level was significantly associated with thoracolumbar VFx, even after adjustment by age, sex, comorbidities, and BMD. Hence, our data demonstrated that low vitamin D level might be an independent risk factor of thoracolumbar VFx.

To date, there is no universally accepted threshold of low serum level of vitamin D. The criteria defined by Holick et al. [1–3] were commonly used to diagnose vitamin D deficiency (<50 nmol/L) or insufficiency (50–75 nmol/L), which was adopted by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists [36], and also by Japan groups [37]. However, a report from the Institute of Medicine showed that 50 nmol/L could be enough to meet the vitamin D demand in almost 97.5% of the population [38]; therefore, a threshold of 75 nmol/L might overestimate vitamin D insufficiency. In this study, we used thresholds of 30 nmol/L for deficiency and 50 nmol/L for insufficiency. When the data were subjected to quartiles analysis, the mean level of serum vitamin D was as follows: 1st quartile, deficiency; 2nd quartile, insufficiency; 3rd and 4th quartiles, sufficiency (Table 4). The VFx risk was lower in the 3rd and 4th quartiles, but not in the 2nd quartile after adjustment. Furthermore, VFx risk increased significantly, to nearly 2-fold, in the 1st quartile comparison with higher quartiles. The ROC curve analysis showed that the cut-off value of vitamin D was 41.15 nmol/L, but the AUC was only 0.58, indicating that a single biomarker of vitamin D deficiency alone was not enough to predict VFx. Therefore, our data suggest that vitamin D deficiency is a risk factor of VFx, and keeping vitamin D at >50 nmol/L might reduce the risk of thoracolumbar junction VFx in elderly patients, but more prospective studies are needed to confirm this.

There were some limitations that should be acknowledged in this study. This was a retrospective case-control study, and enrolled patients were hospital patients rather than a community-based population, so the data might not have reflected the actual status in the general elderly population. Therefore, the present results need to be confirmed by prospective cohort studies with larger sample sizes.

Conclusions

Serum level of vitamin D was significantly lower in primary elderly osteoporotic patients with thoracolumbar junction osteoporotic VFx, and serum vitamin D status was significantly associated with primary osteoporotic VFx, affected numbers of vertebrae, and severities of fracture, especially in female patients. Therefore, vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency was associated with risk of osteoporotic thoracolumbar junction vertebral fractures in elderly patients.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Table 1.

Association of thoracolumbar junction vertebral fracture (VFx) with serum vitamin D status (patients aged 60–80 y).

| Variables | 25(OH)D level(nmol/L) | P-value | P-adjusteda | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 | 30–49.9 | ≥50 | |||

| Grade of VFx (n, %)b | |||||

| Normal | 22 | 82 | 161 | ||

| Grade 1 | 8 | 31 | 38 | ||

| Grade 2 | 16 | 52 | 35 | ||

| Grade 3 | 28 | 56 | 98 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Number of VFx (n, %) | |||||

| 0 | 22 | 82 | 161 | ||

| 1 | 34 | 94 | 105 | ||

| ≥2 | 18 | 45 | 66 | 0.008 | 0.014 |

Adjusted by sex, age and BMI;

Grade of VFs clarified as: Normal, absence of VFs; Grade 1–3, redution of vertebral height of 25%, 25–40%, over 40%, respectively.

Supplementary Table 2.

Association of thoracolumbar junction vertebral fracture (VFx) with quartiles of serum vitamin D (OR, 95% CI) (patients aged 60–80 y).

| Variables | Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | Model 4d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per SD increase in 25(OH)D | 0.65f (0.52–0.80) | 0.67f (0.53–0.85) | 0.64f (0.50–0.82) | 0.64f (0.50–0.82) |

| Q1 | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Q2 | 0.57e (0.36–0.90) | 0.59 (0.35–1.00) | 0.6f (0.35–1.04) | 0.61 (0.35–1.05) |

| Q3 | 0.47f (0.30–0.75) | 0.47f (0.28–0.79) | 0.48f (0.28–0.82) | 0.49f (0.29–0.84) |

| Q4 | 0.35f (0.22–0.56) | 0.37f (0.22–0.63) | 0.33f (0.19–0.58) | 0.33f (0.19–0.58) |

| Q2, Q3, Q4 | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Q1 | 2.19f (1.49–3.20) | 2.12f (1.38–3.25) | 2.15f (1.38–3.35) | 2.13f (1.36–3.32) |

OR – odds ratio; CI – confidence interval; Q – quartile of serum 25(OH)D.

Model 1 basic model without adjustment;

Model 2 adjusted for sex, age, BMI and comorbidities.

Model 3 adjusted for sex, age, BMI, comorbidities and lumbar spine BMD.

Model 4 adjusted for sex, age, BMI, comorbidities, lumbar spine BMD and season.

P<0.05;

P<0.01.

Acknowledgements

We were grateful for Junjian He and Zhirong Deng (Zhongshan School of Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University) for their help for collection of X-ray images.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

Source of support: This study was supported by the Sun Yat-sen University Clinical Research 5010 Program (Grant number 2013006), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81301524), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 15ykpy23)

References

- 1.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(3):266–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(7):1911–30. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holick MF. The vitamin D deficiency pandemic: Approaches for diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2017;18(2):153–65. doi: 10.1007/s11154-017-9424-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swanson CM, Srikanth P, Lee CG, et al. Osteoporotic Fractures in Men MrOS Study Research Group. Associations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D with bone mineral density, bone mineral density change, and incident nonvertebral fracture. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30(8):1403–13. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nuti R, Martini G, Valenti R, et al. Vitamin D status and bone turnover in women with acute hip fracture. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(422):208–13. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000129163.97988.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LeBoff MS, Kohlmeier L, Hurwitz S, et al. Occult vitamin D deficiency in postmenopausal US women with acute hip fracture. JAMA. 1999;281(16):1505–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.16.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avenell A, Mak JC, O’Connell D. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures in post-menopausal women and older men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(4):CD000227. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000227.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El Maataoui A, El Maghraoui A, Biaz A, et al. Relationships between vertebral fractures, sex hormones and vitamin D in Moroccan postmenopausal women: A cross sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s12905-015-0199-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka S, Kuroda T, Yamazaki Y, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D below 25 ng/mL is a risk factor for long bone fracture comparable to bone mineral density in Japanese postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Metab. 2014;32(5):514–23. doi: 10.1007/s00774-013-0520-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim YJ, Park SO, Kim TH, et al. The association of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and vertebral fractures in patients with type 2 diabetes. Endocr J. 2013;60(2):179–84. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.ej12-0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao JG, Zeng XT, Wang J, Liu L. Association between calcium or vitamin D supplementation and fracture incidence in community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2017;318(24):2466–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahwati LC, Weber RP, Pan H, et al. Vitamin D, calcium, or combined supplementation for the primary prevention of fractures in community-dwelling adults: Evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1600–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.21640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maier GS, Seeger JB, Horas K, et al. The prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in patients with vertebral fragility fractures. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(1):89–93. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.97B1.34558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zafeiris CP, Lyritis GP, Papaioannou NA, et al. Hypovitaminosis D as a risk factor of subsequent vertebral fractures after kyphoplasty. Spine J. 2012;12(4):304–12. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruno AG, Burkhart K, Allaire B, et al. Spinal loading patterns from biomechanical modeling explain the high incidence of vertebral fractures in the thoracolumbar region. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32(6):1282–90. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song L, Shen L, Li H, et al. Age at natural menopause and hypertension among middle-aged and older Chinese women. J Hypertens. 2018;36(3):594–600. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang M, Hu RY, Wang H, et al. Age at natural menopause and risk of diabetes in adult women: Findings from the China Kadoorie Biobank study in the Zhejiang area. J Diabetes Investig. 2018;9(4):762–68. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liao X, Zhang Z, Zhang H, et al. [Application guideline for vitamin D and bone health in adult Chinese (2014 Standard Edition) Vitamin D Working Group of Osteoporosis Committee of China Gerontological Society]. Chinese Journal of Osteoporosis. 2014;20(09):1011–30. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aspray TJ, Bowring C, Fraser W, et al. National Osteoporosis Society. National Osteoporosis Society vitamin D guideline summary. Age Ageing. 2014;43(5):592–95. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nowson CA, McGrath JJ, Ebeling PR, et al. Working Group of Australian and New Zealand Bone and Mineral Society, Endocrine Society of Australia and Osteoporosis Australia. Vitamin D and health in adults in Australia and New Zealand: A position statement. Med J Aust. 2012;196(11):686–87. doi: 10.5694/mja11.10301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Genant HK, Wu CY, van Kuijk C, Nevitt MC. Vertebral fracture assessment using a semiquantitative technique. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8(9):1137–48. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bess S, Protopsaltis TS, Lafage V, et al. International Spine Study Group. Clinical and radiographic evaluation of adult spinal deformity. Clin Spine Surg. 2016;29(1):6–16. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei Y, Tian W, Zhang GL, et al. Thoracolumbar kyphosis is associated with compressive vertebral fracture in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(6):1925–29. doi: 10.1007/s00198-017-3971-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hwang JS, Tsai KS, Cheng YM, et al. Vitamin D status in non-supplemented postmenopausal Taiwanese women with osteoporosis and fragility fracture. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:257. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura K, Kitamura K, Takachi R, et al. Impact of demographic, environmental, and lifestyle factors on vitamin D sufficiency in 9084 Japanese adults. Bone. 2015;74:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hwang S, Choi HS, Kim KM, et al. Associations between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and bone mineral density and proximal femur geometry in Koreans: The Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) 2008–2009. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(1):163–71. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2877-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen HT, von Schoultz B, Nguyen TV, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in northern Vietnam: Prevalence, risk factors and associations with bone mineral density. Bone. 2012;51(6):1029–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fisher A, Fisher L, Srikusalanukul W, Smith PN. Usefulness of simple biomarkers at admission as independent indicators and predictors of in-hospital mortality in older hip fracture patients. Injury. 2018;49(4):829–40. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li S, Ou Y, Zhang H, et al. Vitamin D status and its relationship with body composition, bone mineral density and fracture risk in urban central south Chinese postmenopausal women. Ann Nutr Metab. 2014;64(1):13–19. doi: 10.1159/000358340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang YS, Hao DJ, Feng H, et al. Comparison of percutaneous kyphoplasty and bone cement-augmented short-segment pedicle screw fixation for management of Kummell disease. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:1072–79. doi: 10.12659/MSM.905875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang XJ, Sang HX, Bai B, et al. Ex vivo evaluation of hip fracture risk by proximal femur geometry and bone mineral density in elderly Chinese women. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:7438–43. doi: 10.12659/MSM.910876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mosekilde L. Vitamin D and the elderly. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2005;62(3):265–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dawson-Hughes B. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and functional outcomes in the elderly. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(2):537S–40S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.2.537S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cangussu LM, Nahas-Neto J, Orsatti CL, et al. Effect of isolated vitamin D supplementation on the rate of falls and postural balance in postmenopausal women fallers: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Menopause. 2016;23(3):267–74. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(9):CD007146. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Postmenopausal Osteoporosis – 2016. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(Suppl 4):1–42. doi: 10.4158/EP161435.GL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okazaki R, Ozono K, Fukumoto S, et al. Assessment criteria for vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency in Japan: Proposal by an expert panel supported by the Research Program of Intractable Diseases, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan, the Japanese Society for Bone and Mineral Research and the Japan Endocrine Society [Opinion] J Bone Miner Metab. 2017;35(1):1–5. doi: 10.1007/s00774-016-0805-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: What clinicians need to know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(1):53–58. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1.

Association of thoracolumbar junction vertebral fracture (VFx) with serum vitamin D status (patients aged 60–80 y).

| Variables | 25(OH)D level(nmol/L) | P-value | P-adjusteda | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 | 30–49.9 | ≥50 | |||

| Grade of VFx (n, %)b | |||||

| Normal | 22 | 82 | 161 | ||

| Grade 1 | 8 | 31 | 38 | ||

| Grade 2 | 16 | 52 | 35 | ||

| Grade 3 | 28 | 56 | 98 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Number of VFx (n, %) | |||||

| 0 | 22 | 82 | 161 | ||

| 1 | 34 | 94 | 105 | ||

| ≥2 | 18 | 45 | 66 | 0.008 | 0.014 |

Adjusted by sex, age and BMI;

Grade of VFs clarified as: Normal, absence of VFs; Grade 1–3, redution of vertebral height of 25%, 25–40%, over 40%, respectively.

Supplementary Table 2.

Association of thoracolumbar junction vertebral fracture (VFx) with quartiles of serum vitamin D (OR, 95% CI) (patients aged 60–80 y).

| Variables | Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | Model 4d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per SD increase in 25(OH)D | 0.65f (0.52–0.80) | 0.67f (0.53–0.85) | 0.64f (0.50–0.82) | 0.64f (0.50–0.82) |

| Q1 | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Q2 | 0.57e (0.36–0.90) | 0.59 (0.35–1.00) | 0.6f (0.35–1.04) | 0.61 (0.35–1.05) |

| Q3 | 0.47f (0.30–0.75) | 0.47f (0.28–0.79) | 0.48f (0.28–0.82) | 0.49f (0.29–0.84) |

| Q4 | 0.35f (0.22–0.56) | 0.37f (0.22–0.63) | 0.33f (0.19–0.58) | 0.33f (0.19–0.58) |

| Q2, Q3, Q4 | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Q1 | 2.19f (1.49–3.20) | 2.12f (1.38–3.25) | 2.15f (1.38–3.35) | 2.13f (1.36–3.32) |

OR – odds ratio; CI – confidence interval; Q – quartile of serum 25(OH)D.

Model 1 basic model without adjustment;

Model 2 adjusted for sex, age, BMI and comorbidities.

Model 3 adjusted for sex, age, BMI, comorbidities and lumbar spine BMD.

Model 4 adjusted for sex, age, BMI, comorbidities, lumbar spine BMD and season.

P<0.05;

P<0.01.