Regarding interventions for SGMY, this review identified 9 interventions for mental health, 2 for substance use, and 1 for violence victimization.

Abstract

CONTEXT:

Compared with cisgender (nontransgender), heterosexual youth, sexual and gender minority youth (SGMY) experience great inequities in substance use, mental health problems, and violence victimization, thereby making them a priority population for interventions.

OBJECTIVE:

To systematically review interventions and their effectiveness in preventing or reducing substance use, mental health problems, and violence victimization among SGMY.

DATA SOURCES:

PubMed, PsycINFO, and Education Resources Information Center.

STUDY SELECTION:

Selected studies were published from January 2000 to 2019, included randomized and nonrandomized designs with pretest and posttest data, and assessed substance use, mental health problems, or violence victimization outcomes among SGMY.

DATA EXTRACTION:

Data extracted were intervention descriptions, sample details, measurements, results, and methodologic rigor.

RESULTS:

With this review, we identified 9 interventions for mental health, 2 for substance use, and 1 for violence victimization. One SGMY-inclusive intervention examined coordinated mental health services. Five sexual minority–specific interventions included multiple state-level policy interventions, a therapist-administered family-based intervention, a computer-based intervention, and an online intervention. Three gender minority–specific interventions included transition-related gender-affirming care interventions. All interventions improved mental health outcomes, 2 reduced substance use, and 1 reduced bullying victimization. One study had strong methodologic quality, but the remaining studies’ results must be interpreted cautiously because of suboptimal methodologic quality.

LIMITATIONS:

There exists a small collection of diverse interventions for reducing substance use, mental health problems, and violence victimization among SGMY.

CONCLUSIONS:

The dearth of interventions identified in this review is likely insufficient to mitigate the substantial inequities in substance use, mental health problems, and violence among SGMY.

Sexual and gender minority youth (SGMY) are at significantly higher risk than their cisgender (ie, nontransgender) heterosexual peers for substance use, mental health problems, and violence victimization.1 Meta-analyses reveal that compared with heterosexual youth, sexual minority youth (SMY) (ie, gay or lesbian and bisexual youth and youth with same-gender attractions or sexual behaviors) have 123% to 623% higher odds of lifetime substance use (ie, alcohol, cigarette, marijuana, and other drug use)2; 82% to 317% higher odds of mental health problems (ie, depressive symptoms, suicidality)3; and 20% to 280% higher odds of violence victimization (ie, school victimization, physical abuse, sexual abuse).4 Compared with cisgender youth, gender minority youth (GMY) (ie, youth whose gender identity does not match their assigned sex at birth) have 42% to 80% higher odds of lifetime substance use,5,6 470% to 1130% higher odds of depressive symptoms and suicidality,7,8 and 90% to 350% higher odds of violence victimization.5–7

With >20 years of research documenting these substantial health inequities and their causes,1,9 SGMY are now a priority population for research that is focused on preventing, reducing, and treating substance use, mental health problems, and violence victimization.10,11 Nevertheless, there remains limited knowledge about the efficacy and effectiveness of interventions among SGMY. In 2011, the Institute of Medicine identified few interventions for SGMY and recommended prioritizing the development and evaluation of interventions.1

The purpose of this article is to systematically review the state of the scientific literature on interventions and their effectiveness in preventing, reducing, or treating substance use, mental health problems, and violence victimization among SGMY. Systematically documenting whether universal or targeted interventions are effective for SGMY will provide a rigorous assessment of the current state of the SGMY intervention research, thereby informing future research and practice that are aimed at achieving SGMY health equity.

Methods

PROSPERO approved our protocol before data extraction.12

Criteria for Considering Studies for This Review

Studies

We included randomized controlled trials and nonrandomized study designs; we included the latter because not all SGMY-relevant interventions (eg, federal policies legalizing same-gender marriage) are conducive to randomization. However, nonrandomized studies are more likely to be biased than randomized trials,13 and to limit potential biases, we only included studies with both pre- and postintervention data from participants, as recommended by the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Cochrane Review Group.14 Such designs include nonrandomized longitudinal studies and interrupted time series studies. We excluded cross-sectional studies and case report studies.

Participants

We included studies in which authors examined participants aged <18 years at baseline. We selected this because using substances, having mental health problems, and being victimized before age 18 are associated with similar outcomes later in life.15–18 Because study authors sometimes enroll populations both younger and older than 18 years of age, we included studies with a minority (<25%) of adult participants (≥18 years old) or studies reporting results separately for youth participants versus adult populations, as has been done in previous Cochrane reviews.19,20

We included studies if the authors assessed sexual or gender minority status.1,21 We defined sexual minority populations as lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, and other sexual minority identities, as well as youth who have same-gender sexual behavior or attractions. We defined gender minority populations as transgender people (eg, those who identify as transgender or whose current gender identity does not match their assigned sex at birth) or people with other gender-nonconforming identities (eg, genderqueer).

Types of Interventions

We included any type of intervention that was a “purposeful action by an agent to create change”22 or a “process of intervening on people groups, entities or objects.”23 Therefore, this review potentially included behavioral, psychological, educational, pharmacologic, medical, and policy interventions. We included universal and SGMY-specific interventions.

Types of Outcomes

We included studies in which authors examined substance use, mental health problems, or violence victimization as outcomes. Substance use included licit and illicit drug use, such as alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, prescription drug misuse, heroin, hallucinogens, methamphetamine, ecstasy, and cocaine. Mental health problems included stress; anxiety; depressive symptoms; suicidality; internalized homo-, bi-, and/or transphobia; and nonsuicidal self-injury. Violence victimization outcomes included experiences or threats of bullying, cyberbullying, aggression, violence with weapons, harassment, discrimination, sexual assault, sexual abuse, physical abuse, and emotional abuse from all types of perpetrators.

Search Methods for Identifying Potential Studies

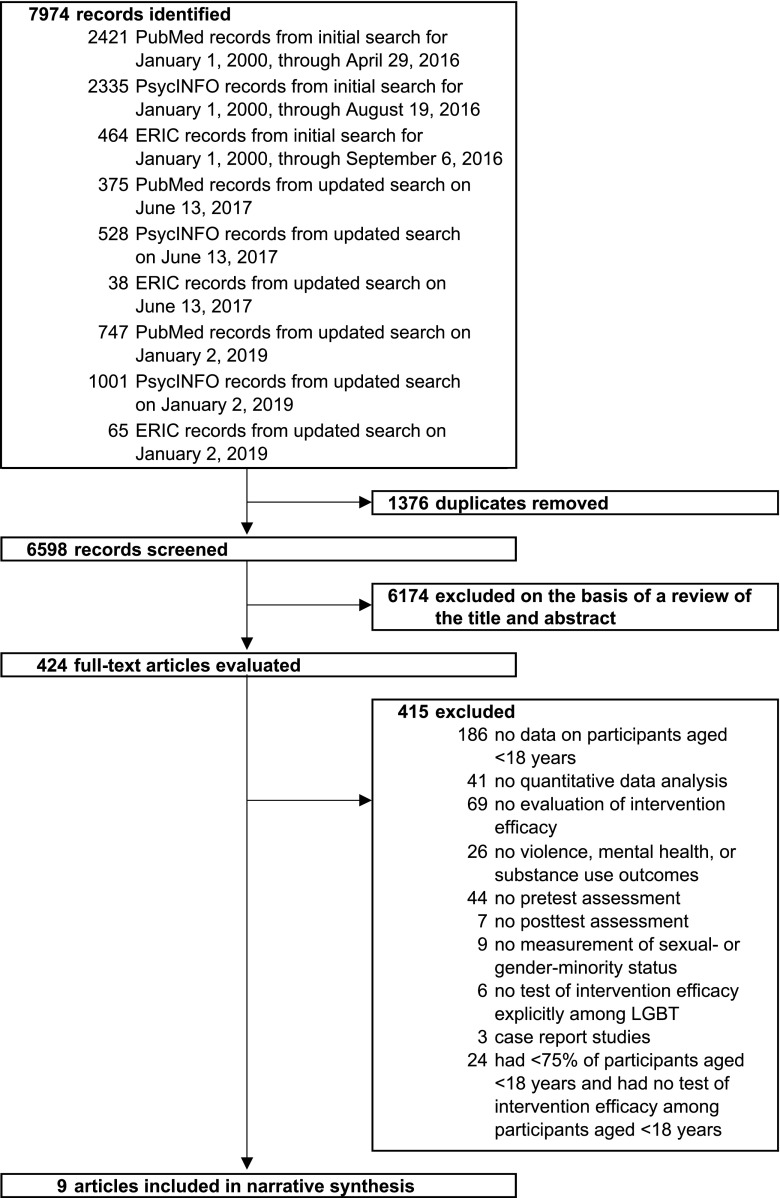

We conducted a search of electronic databases with a research librarian who developed, piloted, and executed the search strategies. We searched PubMed, PsycINFO (via Ovid), and the Education Resources Information Center (via EBSCOhost) for studies published from January 1, 2000, through January 2, 2019 (see Fig 1 for exact dates). The search strategies used a combination of text words and medical subject headings (eg, Medical Subject Headings terms) adapted for each database. The search strategy was developed in PubMed and adapted for PsycINFO and the Education Resources Information Center. The search strategies included the following concepts: sexual or gender minority status24; youth; substance use, mental health problems, or violence; study design and intervention terms; human research; and studies in English. The final PubMed search strategy can be found the Supplemental Information. We excluded animal studies, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, news, editorials, and commentaries. We had no geographical restrictions.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of literature searches and review process results. The specific reasons for exclusion of records at the title and abstract screening level were not recorded. ERIC, Education Resources Information Center; LGBT, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender.

Data Collection and Analysis

Selection of Studies

First, we identified potentially relevant studies by reviewing the titles and abstracts of all retrieved articles. We considered studies with insufficient information in the title or abstract as potentially relevant articles for further assessment. Second, we reviewed the full text of potentially relevant studies for final inclusion or exclusion in our study. Two of 6 investigators independently screened each record and had substantial agreement for title and abstract screening (κ = 0.69) and full-text screening (κ = 0.83).25 The first author resolved any disagreements. We tracked the screening results in DistillerSR (Evidence Partners, Kanata, Ottawa, Canada).

Data Extraction and Management

We conducted a narrative synthesis for each study. Using a standardized form, 2 of 4 investigators independently extracted data from each included study. We extracted data on each study’s intervention, evaluation design, sampling and recruitment procedures, inclusion andexclusion criteria, sample characteristics, outcome measures, and main findings. One investigator placed all extracted data in tabular format, and another investigator reviewed the table for accuracy and completeness. The 2 investigators discussed any discrepancies until they reached a consensus.

Methodologic Quality

We selected the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies checklist to assess methodologic rigor because this tool assesses characteristics of both randomized and nonrandomized studies.26 Two independent raters evaluated each study; raters then discussed any discrepancies until they reached a consensus. Raters assessed 6 characteristics for each study: selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection method, and withdrawals and dropouts. On the basis of the ratings from these 6 characteristics, each study received a global rating. Possible ratings for each study characteristic and global rating included weak, moderate, and strong (ranging from least to most methodologically rigorous).

Results

Searches identified 6598 unique studies, of which 424 studies were potentially relevant for inclusion in this review (Fig 1). After full-text screening, 9 studies met the inclusion criteria.27–35

Intervention Descriptions

Interventions inclusive of all SGMY were evaluated in 1 study,32 interventions tailored specifically to GMY were evaluated in 3 studies,27–29 and interventions specifically tailored to SMY were evaluated in 5 studies (Table 1).30,31,33–35 The program inclusive of all SGMY was the Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children with Serious Emotional Disturbances Program, more commonly known as the Children’s Mental Health Initiative.32 This program provided coordinated networks of community-based services tailored to the local needs of youth.32 The participants served by this program received a wide variety of specific interventions, including individual therapy, medication treatment, case management, group therapy, recreational activities, inpatient hospitalization, vocational training, family support, and residential treatment, which were all tailored to the participants’ local context and individual needs.32

TABLE 1.

Summaries of Studies Included in This Review

| Source | Intervention Description | Intervention Length | Evaluation Design | Sampling and Recruitment | Inclusion Criteria | Sample Characteristics | Outcome Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costa et al27 | Aimed at relieving distress associated with puberty development in adolescents with gender dysphoria, the authors of this study examined the effects of psychological-only and psychological and puberty suppression interventions on the psychosocial functioning of youth. These interventions were delivered following guidelines set by the WPATH Standards of Care. Psychological support was provided to youth and their families (both together and separately) to support them through the early recognition and nonjudgmental acceptance of the gender identities of youth and ameliorate any behavior, emotion, or relationship problems. A variety of psychotherapeutic approaches were used and sometimes included social and educational interventions. Puberty suppression was provided by using GnRH analogs. | Immediately after baseline assessment, all youth received psychological support during the entire duration of the study at least once per mo. Nine mo. (on average) after baseline assessment, puberty suppression was initiated for the psychological and puberty suppression intervention group. | This was a nonrandomized comparison group pretest-posttest design using multiple posttests. Youth were assessed at baseline, 6, 12, and 18 mo (corresponding to time 0–3). At time 0, no intervention had taken place. At time 1, all participants had received psychological support. At times 2 and 3, some participants had received only the psychological intervention (ie, the psychological-only intervention group), and some participants had received psychological and puberty suppression interventions (ie, the psychological and puberty suppression intervention group). Participants were placed in the psychological and puberty suppression intervention group if they had a presence of gender dysphoria from early childhood on, an increase in gender dysphoria after their first puberty changes, an absence of psychiatric comorbidity that interferes with the diagnostic workup or treatment, adequate psychological and social support during treatment, and a demonstration of knowledge and understanding of the effects of puberty suppression, crossgender hormone treatment, surgery, and the social consequences of gender affirmation surgery. Otherwise, participants were placed in the psychological-only intervention group. | Youth were recruited from a population of youth with gender dysphoria who were referred to a gender identity clinic in London, England, from 2010 to 2014. All youth who completed the standard-of-care diagnostic assessments (∼6 mo after entry into the clinic) were invited to take part in the study. | At baseline, all participants were diagnosed with gender identity disorder (per the DSM-IV-TR criteria). Youth and their parents gave informed consent. | The total sample contained 201 youth; 101 youth were in the psychological-only intervention group, and 100 youth were in the psychological and puberty suppression intervention group. The 2 intervention groups did not differ with regard to natal sex, age, living arrangement, and education. Total sample: N = 201; mean age: 15.52 y at baseline (range: 12–17 y); assigned birth sex: 62.2% female and 37.8% male. | Psychosocial Functioning: Children’s Global Assessment Scale | In the total sample, compared to time 0 (57.73), psychosocial functioning significantly improved at time 1 (60.68; P < .001), time 2 (63.31; P < .001), and time 3 (64.93; P < .001). |

| The psychological-only intervention group did not significantly differ from the psychological and puberty suppression intervention group in psychosocial functioning at any time point (P range: .14–.73). | ||||||||

| Among the psychological-only intervention group, compared to time 0 (56.63), psychosocial functioning significantly improved at time 1 (60.29; P = .05), time 2 (62.97; P = .005), and time 3 (62.53; P = .02). However, psychosocial functioning was not significantly different for time 1 vs 2 (P = .22), time 1 vs 3 (P = .37), or time 2 vs 3 (P = .88). | ||||||||

| Among participants of the psychological and puberty suppression intervention group, compared to time 0 (58.72), psychosocial functioning did not significantly differ at time 1 (60.89; P = .19) but was significantly higher at time 2 (64.70; P = .003) and time 3 (67.40; P < .001). Although psychosocial functioning significantly improved from time 1 vs 3 (P = .001), there were no significant differences for time 1 vs 2 (P = .07) and time 2 vs 3 (P = .35). | ||||||||

| de Vries et al28 | Aimed at enabling youth with gender dysphoria to explore their gender identity without the distress of physical puberty development, this intervention used puberty suppression via GnRH analogs. | Puberty suppression was conducted for 1.9 y (on average). | This was a 1-group pretest-posttest design. Youth were assessed at baseline and postintervention, which was 3.0 y on average after baseline (before the start of crossgender hormones). Puberty suppression was initiated 1.1 y, on average, after baseline assessment. | From 2000 to 2008, 140 of 196 referred youth were considered eligible for medical intervention at a gender identity clinic in Amsterdam, Netherlands. Of the 140 youth, 111 youth were given the intervention. Participants of this study were the first 70 children who had subsequently started crossgender hormone treatment. | Adolescents were eligible for puberty suppression when they were diagnosed with gender identity disorder, had shown persistent gender dysphoria since childhood, lived in a supportive environment, and had no serious comorbid psychiatric disorders that may have interfered with the diagnostic assessment. Youth and their parents gave informed consent. | The total sample contained 70 youth participants. Total sample: N = 70; mean age: 13.56 y at baseline (range: 11–17 y); assigned birth sex: 52.9% female and 47.1% male; sexual orientation: 88.6% had same-natal-sex attractions, 8.6% had both-natal-sex attractions, and 2.8% reported something else. | Depressive Symptoms: Beck Depression Inventory-II | Depressive symptoms decreased significantly from baseline to postintervention; 8.31 vs 4.95; F1,39 = 9.28; P = .004. |

| Anxiety symptoms: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory | Anxiety symptoms did not significantly decrease from baseline to postintervention; 39.43 vs 37.95; F1,39 = 1.21; P = .276. | |||||||

| Internalizing symptoms: Youth Self-Report | Internalizing symptoms decreased significantly from baseline to postintervention; 56.04 vs 49.78; F1,52 = 15.05; P < .001. The percentage of youth participants scoring in the clinical range for internalizing symptoms significantly decreased from baseline to postintervention; 29.6% vs 11.1%; χ21 = 5.71; P = .017. | |||||||

| Internalizing symptoms: Child Behavior Checklist | Internalizing symptoms decreased significantly from baseline to postintervention; 61.00 vs 54.46; F1,52 = 22.93; P < .001. | |||||||

| Externalizing symptoms: Youth Self-Report | Externalizing symptoms decreased significantly from baseline to postintervention; 53.30 vs 49.98; F1,52 = 7.26; P = .009. | |||||||

| Externalizing symptoms: Child Behavior Checklist | Externalizing symptoms decreased significantly from baseline to postintervention; 58.04 vs 53.81; F1,52 = 12.04; P = .001. | |||||||

| de Vries et al29 | Aimed at providing high-quality clinical care to youth with gender dysphoria, this intervention included puberty suppression, crossgender hormones, and gender affirmation surgery. Puberty suppression was provided by using GnRH analogs. Crossgender hormones were provided. Gender affirmation surgery included vaginoplasty for transwomen and mastectomy and hysterectomy with ovariectomy for transmen. | Participants started puberty suppression at a mean age of 14.8 y (range: 11.5–18.5 y), crossgender hormones at a mean age of 16.7 y (range: 13.9–19.0 y), and gender affirmation surgery at a mean age of 19.2 y (range: 18.0–21.3 y). | This was a 1-group pretest-midtest-posttest design. Youth were assessed at baseline (time 0), during intervention (time 1; ∼3.1 y after baseline; after initiation of puberty suppression and before initiation of crossgender hormones), and at postintervention (time 2; ∼7.1 y after baseline; and 1 y after gender affirmation surgery). | Participants were recruited from the first cohort of 70 children who had gender dysphoria, who were prescribed puberty suppression in Amsterdam, Netherlands, and who continued with gender affirmation surgery between 2004 and 2011. | Youth were eligible for puberty suppression, crossgender hormones, and gender affirmation surgery at the respective ages of 12, 16, and 18 y if they had a history of gender dysphoria, no psychosocial problems, adequate family or other support, and a good comprehension of the impact of medical interventions. At postintervention, from 2008 to 2012, young adults were eligible if they were ≥1 y past their gender affirmation surgery. Puberty suppression started after youth entered the first stages of puberty (Tanner stages 2–3). At baseline and time 1, youth and their parents provided consent. At time 3, only participants provided consent. | The total sample contained 55 participants. Total sample: N = 55; mean age: 13.6 y at baseline (range: 11.1–17.0 y); gender: 40.0% transwomen and 60.0% transmen. | Depressive symptoms: Beck Depression Inventory | Depressive symptoms had significant quadratic trends over time (P = .04), decreasing from baseline (7.89) to time 1 (4.10), and increasing at time 2 (5.44). Trends were similar by gender. |

| Anxiety symptoms: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory | Anxiety symptoms did not have linear (P = .42) or quadratic (P = .47) trends over time. However, the linear trends were different by gender (P = .05): for transmen, symptoms decreased over time (44.41 at baseline; 41.59 at time 1; and 39.20 at time 2); for transwomen, average symptoms were lower at baseline and time 1 (31.87 and 31.71) than at time 2 (35.83). | |||||||

| Psychosocial functioning: Children’s Global Assessment Scale | Psychosocial functioning increased linearly over time (P < .001). Psychosocial functioning was 71.13 at baseline, 74.81 at time 1, and 79.94 at time 2. Trends were similar by gender. | |||||||

| Internalizing symptoms: Child and Adult Behavior Checklists | Internalizing symptoms linearly decreased over time (P < .001). Average internalizing symptoms were 60.83 at baseline, 54.42 at time 1, and 50.45 at time 2. Trends were similar by gender. Overall, prevalence of clinical levels of internalizing symptoms significantly decreased from baseline to time 1 (30.0% vs 12.5%), plateauing at time 3 (10.0%). | |||||||

| Internalizing symptoms: Youth and Adult Self-Reports | Internalizing symptoms had quadratic trends over time (P = .008), decreasing from baseline to time 1 (55.47–48.65), and increasing at time 2 (50.07). Trends were similar by gender. Overall, prevalence of clinical levels of internalizing symptoms significantly decreased from baseline to time 1 (30.0% vs 9.3%), but time 2 prevalence (11.6%) was similar to both previous time points. | |||||||

| Externalizing symptoms: Child and Adult Behavior Checklists | Externalizing symptoms decreased linearly over time (P < .001; 57.85 at baseline, 53.85 at time 1, and 47.85 at time 2). Trends were similar by gender. Overall, the prevalence of clinical levels of externalizing symptoms was not significantly different from baseline to time 1 (40.0% vs 25.0%) but was significantly lower at time 2 (2.5%). | |||||||

| Externalizing symptoms: Youth and Adult Self-Reports | Externalizing symptoms did not have linear (P = .14) or quadratic (P = .09) trends. But linear trends differed by gender (P = .005): for transmen, there were linear decreases (57.16 at baseline; 52.64 at time 1; and 50.24 at time 2); for transwomen, symptoms were lower at baseline and time 1 (46.00 and 44.71) than at time 3 (50.24). Overall, prevalence of clinical levels of externalizing symptoms did not significantly change (21.0% at baseline; 11.6% at time 1; 7.0% at time 2). | |||||||

| Diamond et al30 | Aimed at reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms among SMY, this intervention tested a form of Attachment-Based Family Therapy specifically tailored to the needs of SMY and their families. Attachment-Based Family Therapy is an empirically informed, manualized family-based treatment, but this specific intervention was adapted by researchers and clinicians who had experience working with SMY. All therapy sessions were delivered in person by a PhD-level clinical psychologist. Sessions were provided to adolescents by themselves, parent(s) by themselves, and an adolescent and their parent(s) together. This intervention was guided by attachment theory, structural family therapy, multidimensional family therapy, and emotion-focused therapy. | Completing at least 8 sessions was considered a full intervention dosage. The No. sessions per participant ranged from 8 to 16, with an average of 12 sessions per family. Sessions were ∼60 min in length and were conducted on a weekly basis. | This was a 1-group pretest-midtest-posttest design. Research assistants naïve to the study purpose administered assessments at baseline, 6 wk later (halfway through intervention), and 12 wk later (postintervention). | Patients were recruited from 2 private psychiatric hospitals in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where participants had been admitted for suicidal ideation or attempts. Social work staff employed by the hospitals screened potential participants 1 wk before their discharge, and youth endorsing significant levels of suicidal ideation (per a score ≥31 on the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Junior) were referred to the study. | Youth participants had to self-identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual and had to report significant levels of suicidal ideation as evidenced by a score ≥31 on the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Junior. Youth were excluded if they had current psychosis or mental retardation. Youth and their parents gave informed consent. | The total sample contained 10 youth participants. Regarding parental participation, 40% of youth completed the intervention with 2 parents, and 60% completed the intervention with their mother only. Total sample: N = 10; mean age: 15.10 y at baseline (range: 14–18 y); gender: 80% female and 20% male; sexual orientation: 30% identified as exclusively gay or lesbian, 10% identified as primarily gay and also attracted to girls, and 60% identified as primarily lesbian and also attracted to boys; race and/or ethnicity: 20% white, 50% African American, 20% multiracial, and 10% other. | Depressive Symptoms: Beck Depression Inventory-II | Average depressive symptoms decreased over the course of treatment; F2,18 = 4.59; P = .03; d = 0.90. |

| Suicidal ideation symptoms: Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Junior | Average suicidal ideation decreased over the course of treatment; F2,18 = 18.78; P = .001; d = 2.10. | |||||||

| Lucassen et al31 | Aimed at reducing depressive symptoms for SMY, this intervention used a 7-module computerized cognitive behavioral therapy intervention delivered via CD-ROM on personal computers and a paper-based user notebook. This intervention used the medium of a fantasy world where the user’s avatar is faced with a series of challenges to rid a virtual world of gloom and negativity. On the basis of cognitive behavioral therapy theories and adapted from an efficacious intervention (SPARX), this intervention was tailored to the needs SMY by having them contribute to the adaptation process. Participants could choose whether to complete the program at home, at a youth-led organization for SMY, at a selected high school, or on a dedicated computer where the study was based. | Each of the 7 modules took ∼30 min to complete. Participants were instructed to complete 1 or 2 modules per wk and to finish all modules within 2 mo. | This was a 1-group pretest-posttest-posttest design. Youth participants completed questionnaires at baseline, immediately postintervention, and 3 mo postintervention. | One youth-led organization for SMY and 4 high schools promoted the study in Auckland, New Zealand. The study was also advertised and endorsed by sexual-minority media. | Youth participants had to be attracted to the same sex, both sexes, or not sure of their sexual attractions; 13–19 y old; have depressive symptoms (i.e., Child Depression Rating Scale, Revised, raw score ≥30) at baseline; and living in Auckland, New Zealand. SMY with severe depressive symptoms or at risk for suicide or self-harm were eligible if they reported receiving support from a school guidance counselor, therapist, or general practitioner. Those receiving antidepressant medication or other relevant therapies were able to take part; these additional treatments were documented at the preintervention assessment. For youth <16 y, youth and their parents gave informed consent. For youth ≥16 y, only youth gave informed consent. | The total sample contained 21 youth. Total sample: N = 21; mean age: 16.5 y at baseline (range: 13–19 y); gender: 47.6% female and 52.3% male; sexual orientation: 47.6% had same-sex attractions, 47.6% had both-sex attractions, and 4.8% were not sure; race and/or ethnicity: 71.4% New Zealand European, 9.5% Māori, 4.8% Pacific ethnicity, and 14.3% Asian. | Depressive Symptoms: Children’s Depression Rating Scale, Revised | Depressive symptoms decreased significantly from baseline to immediate postintervention (mean change = −7.43; 95% CI: −10.79 to −4.07; P < .0001; d = 1.01). Depressive symptoms remained similar from immediate postintervention to 3 mo postintervention (mean change = −0.62; 95% CI: −5.82 to 4.58; P = .81). |

| Depressive Symptoms: Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale | Depressive symptoms decreased significantly from baseline to immediate postintervention (mean change = −7.90; 95% CI: −12.17 to −3.64; P = .001; d = 0.84). Depressive symptoms remained similar from immediate postintervention to 3 mo postintervention (mean change = −0.86; 95% CI: −5.41 to 3.70; P = .70). | |||||||

| Depressive Symptoms: Mood and Feelings Questionnaire | Depressive symptoms decreased significantly from baseline to immediate postintervention (mean change = −6.19; 95% CI: −11.13 to −1.25; P = .02; d = 0.57). Depressive symptoms remained similar from immediate postintervention to 3 mo postintervention (mean change = 0.67; 95% CI: −5.58 to 6.92; P = .83). | |||||||

| Anxiety symptoms: Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale | Anxiety symptoms decreased significantly from baseline to immediate postintervention (mean change = −7.86; 95% CI: −11.62 to −4.10; P < .0001; d = 0.95). Anxiety symptoms were not assessed 3 mo postintervention. | |||||||

| Hopelessness: Kazdin Hopelessness Scale for Children | Hopelessness scores decreased significantly from baseline to immediate postintervention (mean change = −1.43; 95% CI: −2.43 to −0.43; P = .008; d = 0.65). Hopelessness was not assessed 3 mo postintervention survey. | |||||||

| Painter et al32 | This program provided youth with services and supports through the Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children with Serious Emotional Disturbances Program, more commonly known as the Children’s Mental Health Initiative. Guided by the “systems of care” framework, this program provided coordinated networks of community-based services tailored to youth. The interventions considered the unique strengths and needs of the youth target population and incorporated cultural, racial, ethnic, and linguistic diversity of the local environments, which included awareness of, sensitivity toward, and confidentiality for SGMY. The participants served by this program received a wide variety of specific interventions, including individual therapy, medication treatment, case management, group therapy, recreational activities, inpatient hospitalization, vocational training, family support, and residential treatment. | Interventions widely varied in length. For example, 6 mo after enrollment, those who received medication treatment had an average of 4.5 visits, those who received individual therapy had an average of 16.1 sessions, and those who were part of a therapeutic group home spent on average 124.7 d receiving the intervention. Treatment plans were created on an individual basis and constrained by the locally offered services and supports. | This was a 1-group pretest-midtest-posttest design. Youth and their caregivers completed questionnaires at baseline, 6 mo after baseline, and 12 mo after baseline. | Youth and caregivers were recruited within the 47 systems of care grantee communities from 2010 to 2014. | Youth had to be age 11–21 y, have a serious emotional disturbance, have entered Children’s Mental Health Initiative care services through 1 of 47 systems of care grantee communities from 2010 to 2014, have participated in the national evaluation, and identify as a sexual or gender minority. | The total sample contained 482 youth participants. Total sample: N = 482; age: 8.7% aged 11–12 y, 28.6% aged 13–15 y, 42.9% aged 15–17 y, and 19.7% aged 18–21 y; gender: 22.6% male, 68.3% female, 1.0% transgender female, 2.3% transgender male, 4.6% not sure, and 1.2% other; sexual orientation: 15.4% mostly heterosexual, 49.8% bisexual, 5.0% mostly homosexual, 12.0% homosexual, 5.4% other, and 12.4% questioning; race and/or ethnicity: 3.7% American Indian or Alaskan native, 25.5% African American, 0.4% native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, 42.9% white, 17.0% Hispanic or Latino, and 10.4% multiracial. | Anxiety symptoms: Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale, Second Edition | Anxiety symptoms significantly decreased across time: F2,167 = 5.59; P = .004. |

| Depressive symptoms: Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale, Second Edition | Depressive symptoms significantly decreased across time: F2,198 = 5.16; P = .006. | |||||||

| Global functioning impairment: Columbia Impairment Scale | Global functioning impairment symptoms significantly decreased across time: F2,212 = 60.02; P < .001). | |||||||

| Internalizing and externalizing symptoms: Child Behavior Checklist | Internalizing symptoms (F2,242 = 9.34; P < .001), externalizing symptoms (F2,214 = 15.73; P < .001), and total internalizing and externalizing symptoms (F2,251 = 15.78; P < .001) significantly decreased across time. | |||||||

| Substance use and/or substance abuse symptoms: Substance Use and Abuse Scale-9 (GAIN Quick-R) | Substance use and/or substance abuse symptoms significantly decreased across time: F2,147 = 5.33; P = .006. | |||||||

| Substance dependence symptoms: Substance Dependence Scale-7 from (GAIN Quick-R) | Substance dependence symptoms significantly decreased across time: F2,149 = 7.93; P = .001). | |||||||

| Total substance use and/or substance abuse symptoms and substance dependence symptoms: GAIN Quick-R Total Substance Problems Scale | Total substance problems significantly decreased across time: F2,193 = 5.15; P < 0.01). | |||||||

| Raifman et al33 | This intervention was the presence of a US state-level policy that granted same-sex couples equivalent marriage rights as opposite-sex couples. | This was a 1-time enactment of state-level policy. | This was an interrupted time series design using serial biennial cross-sectional data before and after policy intervention implementation. | Data were collected in the United States via the biennial state YRBSS from 1999 to 2015. YRBSS uses a 2-stage sampling of schools and classrooms to obtain a representative sample of students in grades 9–12 in public schools. A total of 47 states were included, and 25 states collected information about sexual identity in 2015. | Youth were included if they were in grades 9–12 in a sampled public school and classroom. YRBSS uses active or passive parental permission depending on the administering state. Student surveys are anonymous and voluntary. | The total sample contained 762 678 youth. The intervention and control groups differed by age and race and/or ethnicity but not gender. Information about group differences by sexual identity were not included. In 2015, 12.7% identified as sexual minorities: 2.4% as gay or lesbian, 6.4% as bisexual, and 4.0% as not sure. Intervention: n = 546 276; mean age: 15.9 y (SD: 1.2 y); gender: 49.7% male and 50.3% female; race and/or ethnicity: 58.4% white, 11.3% Hispanic, 14.3% African American, and 16.0% other. Control: n = 216 402; mean age: 16.0 (SD: 1.2 y); gender: 49.6% male and 50.4% female; race and/or ethnicity: 55.0% white, 16.1% Hispanic, 18.6% African American, and 10.3% other. | Suicide attempts: “During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?” This was coded as any versus none. | Across all states before implementation of same-sex marriage policies, 28.5% of SMY and 8.6% of all youth reported having at least 1 past-year suicide attempt. After implementation among SMY, there was a significant decline in past-year suicide attempt prevalence (net change = −4.0; 95% CI: −6.9 to −1.2; P < .01), which is equivalent to a 14% relative decline in the proportion of SMY reporting at least 1 past-year suicide attempt. After implementation, there was also a significant decline in past-year suicide attempt prevalence among all youth (mean net change = −0.6; 95% CI: −1.2 to −0.1; P < .05). |

| Schwinn et al34 | Aimed at reducing substance use among SMY via an online intervention, this intervention had an animated young adult narrator guide youth through interactive games, role-playing, and writing activities. Activities focused on skills for identifying and managing stress, making decisions, addressing drug use rates, and teaching drug refusal skills. This intervention was guided by a social competency skill-building strategy and minority stress theory. | Three sessions were completed throughout a 4-wk period. Youth completed each session in 14 min, on average. | This was a randomized controlled trial using a pretest-posttest design. Youth completed online questionnaires at baseline, immediately postintervention, and 3 mo postintervention. Youth completed follow-up questionnaires ∼1 mo and 4.5 mo after baseline. Authors only reported baseline and 3-mo postintervention results. | Youth were recruited from across the United States through Facebook advertisements posted to the pages of 15- and 16-y-old youth. Six advertisements ran for 9 d in the spring of 2014. | Youth were included if they were 15 or 16 y of age, a US resident, had access to a personal computer, and identified as gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, or questioning. Youth had to correctly answer a 5-question quiz on study procedures to participate. This study had a waiver of parental permission. | The total sample contained 236 youth. The intervention and control groups did not differ by demographics at baseline. Intervention: n = 119; mean age: 16.05 y at baseline (range: 15–16 y); gender: 32.1% male, 49.6% female, and 18.3% queer, fluid, or other; sexual orientation: 39.4% had same-sex attractions, 49.5% had both-sex attractions, 5.5% had opposite-sex attractions, and 5.6% were unsure; race and/or ethnicity: 66.1% white, 12.8% Hispanic, 7.3% African American, 6.4% Asian American, and 7.4% other. Control: n = 117; mean age: 16.10 y at baseline (range: 15–16 y); gender: 33.3% male, 52.2% female, and 4.5% queer, fluid, or other; sexual orientation: 37.9% had same-sex attractions, 49.1% had both-sex attractions, 6.9% had opposite-sex attractions, and 6.1% were unsure; race and/or ethnicity: 58.1% white, 13.7% Hispanic, 12.0% African American, 8.5% Asian American, and 7.7% other. | Alcohol use: No. times drank in past 30 d | At baseline, there was not a significant difference for intervention versus control groups (P = .09). At 3-mo follow-up, there was not a significant difference for intervention versus control groups in mean alcohol use frequency (1.29 vs 1.10; P ≥ .05; t = 0.66). |

| Cigarette smoking: No. times smoked in past 30 d | At baseline, there was not a significant difference for intervention versus control groups (P = .82). At 3-mo follow-up, there was not a significant difference for intervention versus control groups in mean cigarette smoking frequency (0.72 vs 0.90; P ≥ .05; t = 0.59). | |||||||

| Marijuana use: No. times used in past 30 d | At baseline, there was not a significant difference for intervention versus control groups (P = .51). At 3-mo follow-up, there was not a significant difference for intervention versus control groups in mean marijuana use frequency (1.63 vs 1.74; P ≥ .05; t = 0.41). | |||||||

| Other drug use: No. times used in past 30 d | At baseline, there was not a significant difference for intervention versus control groups (P = .31). At 3-mo follow-up, intervention group participants had significantly lower mean other drug use frequency than control group participants (1.03 vs 1.09; P < .05; t = 2.16; d = 0.34). | |||||||

| Perceived stress: scores ranged from 1 (low) to 5 (high) | At baseline, there was not a significant difference for intervention versus control groups (P = .72). At 3-mo follow-up, intervention group participants had significantly lower mean perceived stress than control group (3.05 vs 3.33; P < .05; t = 2.27; d = 0.34). | |||||||

| Seelman and Walker35 | The 2 interventions were (1) the presence (versus absence) of a US state-level general antibullying law and (2) the presence (versus absence) of a US state-level antibullying law that enumerated sexual orientation as a protected class. | This was a 1-time enactments of the 2 different state-level laws. | This was an interrupted time series design using serial biennial cross-sectional data. | Data were collected in the United States via the biennial state YRBSS from 2005 to 2015. YRBSS uses a 2-stage sampling of schools and classrooms to obtain a representative sample of students in grades 9–12 in public schools. A total of 22 states were included. Only 3 states had data from both before and after enactment of the general antibullying law, and 4 states had data from both before and after enactment of the enumerated antibullying law. | Youth were included if they were in grades 9–12 in a sampled public school and classroom. YRBSS uses active or passive parental permission depending on the administering state. Student surveys are anonymous and voluntary. | The total sample contained 286 568 youth. Information about demographic differences by states with and without the intervention laws were not included. Total sample: N = 286 568; mean age: 16.0 y (SD: 0.02 y); gender: 50.6% male and 49.4% female; sexual orientation: 10.5% identified as lesbian or gay, bisexual, or not sure (henceforth referred to as questioning) and 89.5% identified as heterosexual. | Bullying victimization: “During the past 12 months, have you ever been bullied on school property?” This was coded as any versus none. | General antibullying laws were associated with reductions in bullying victimization among LGB youth (b = −0.055; SE = 0.023) and LGBQ youth (b = −0.072; SE = 0.024). In states with general antibullying laws, 6.4% fewer LGB youth and 7.5% fewer LGBQ youth were bullying victims. Enumerated antibullying laws were also associated with reductions in bullying victimization among LGB youth (b = −0.056; SE = 0.023) but not LGBQ youth by (b = −0.016; SE = 0.016). In states with enumerated antibullying laws, 5.1% fewer LGB youth were bullying victims. The protective associations of both general and enumerated antibullying laws were pronounced among LGB and LGBQ boys <16 y old. |

| Threatened or injured with a weapon: “During the past 12 months, how many times has someone threatened or injured you with a weapon such as a gun, knife, or club on school property?” This was coded as any versus none. | Neither general nor enumerated antibullying laws were associated with being threatened or injured with a weapon among LGB or LGBQ youth (data not provided). However, there was a protective association for general antibullying laws among LGBQ boys <16 y old: in states with general antibullying laws, 13.8% fewer LGBQ boys <16 y reported being threatened or injured with a weapon. This protective association was not found when examining the same group of only LGB boys. | |||||||

| Suicidal ideation: “During the past 12 months, did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?” This was coded as any versus none. | Neither general nor enumerated antibullying laws were associated with suicidal ideation among LGB or LGBQ youth (data not provided). These associations were similar by sex and age. | |||||||

| Suicide attempt: “During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?” This was coded as any versus none. | General antibullying laws were not associated with suicide attempts among LGB youth (b = 0.009; SE = 0.023) or LGBQ youth (b = 0.005; SE = 0.019). Enumerated antibullying laws were associated with reductions in suicide attempts among LGBQ youth by 3.3% (b = −0.037; SE = 0.015; P < .05), but not among only LGB youth (b = 0.009; SE = 0.022). |

CD-ROM, compact disc read-only memory; CI, confidence interval; DSM-IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV Text Revision; GAIN Quick-R, Global Appraisal of Individual Needs–Quick-Revised; LGBQ, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning; SPARX, Smart, Positive, Active, Realistic, X-factor; YRBSS, Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System.

Authors of all the GMY-specific interventions examined transition-related gender-affirming care interventions (ie, puberty suppression, crossgender hormones, gender affirmation surgery, and psychological support following the Standards of Care of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health [WPATH]).27–29,36 Authors of 2 studies27,28 examined the effects of puberty suppression (ie, the provision of gonadotropin-releasing hormone [GnRH] analogs that delay the physical changes associated with puberty36) on mental health. Specific clinical criteria must be met to receive puberty-suppressing hormones.27,28,36 Should those clinical criteria not be met, youth receive psychological support as standard of care; therefore, authors of 1 study27 had a 2-group design in which they compared the effects of a psychological-only intervention to a psychological and puberty suppression intervention. The other study28 had a 1-group design, observing only youth who received puberty suppression. Authors of the third study29 examined the effects of crossgender hormones and gender affirmation surgery on mental health using a subset of participants from the previous study.28 All of the intervention studies for GMY followed WPATH Standards of Care,36 and all participants received ongoing medical or psychological care from baseline through final posttest assessment.27–29

Among the SMY-specific interventions, there was a therapist-administered family-based intervention to reduce mental health problems,30 a self-administered computer-based intervention to reduce mental health problems,31 a self-administered online intervention to reduce substance use and stress,34 a state-level policy granting same-sex marriage,33 and state-level general and enumerated antibullying laws.35 The state-level interventions consisted of one-time policy enactments.33,35 Both the self-administered interventions31,34 were shorter in duration and smaller in dosage than the therapist-administered intervention.30 The self-administered interventions used three 14-minute modules delivered during a 1-month period34 or seven 30-minute modules delivered during a 2-month period.31 The therapist-administered intervention had between 8 and 16 weekly in-person sessions that lasted for 1 hour.30 The nonpolicy interventions had specific theoretical underpinnings.30,31,34 One intervention incorporated input from youth during development,31 and 1 used input from clinicians.30

Evaluation Designs

A randomized controlled study design was used in 1 study,34 a nonrandomized comparison group design was used in 1 other study,27 an interrupted time series design was used in 2 studies,37,38 and a 1-group design was used in 5 studies.28–32 Two studies had a pretest-posttest design,28,34 1 had a pretest-posttest-posttest design,31 3 had a pretest-midtest-posttest design,29,30,32 1 had a pretest-posttest design with >2 posttests.27 The interrupted time series designs varied in their number of pretest and posttests depending on the states and policy enactment dates, and the authors of these studies used serial cross-sectional data without the ability to track individual participants across time.33,35 For the longitudinal studies tracking participants, the average length between baseline and the final posttest ranged from 0.230 to 7.129 years.

Sampling and Recruitment Procedures

In 2 of the SMY-specific interventions, authors used probabilistic sampling frames from public high schools via the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System.33,35 In 6 studies, various forms of convenience sampling were used: GMY-specific interventions27–29 recruited participants from clinics, and, of the remaining SMY-specific interventions, 1 study recruited from clinics,30 1 from Facebook,34 and 1 from high schools, a local SGMY organization, and SGMY media.31 Authors of the SGMY-inclusive study omitted their specific sampling strategy but recruited participants who accessed services and supports from 47 communities across the United States.32 The GMY-specific interventions were conducted in Europe,27–29 with 1 in England27 and 2 in the Netherlands28,29; 4 of the SMY-specific interventions were evaluated in the United States30,33–35 and 1 was in New Zealand.31

Inclusion Criteria

The SGMY-inclusive intervention was provided to all youth with serious emotional disturbance (wherein the most commonly reported problems being depression, anxiety, and conduct and/or delinquency) but included only SGMY in analyses.32 The GMY-specific interventions was only implemented with youth who had a gender identity disorder diagnosis as identified through the criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition.27–29 In the SMY-specific interventions, 2 studies included all youth with subanalyses on SMY,33,35 1 study included only SMY with significant suicidal ideation,30 1 study included only SMY with depressive symptoms,31 and 1 study did not have any eligibility criteria related to mental health.34

Sample Characteristics

The included studies27–35 had 1 050 339 total participants with a median of 20127 participants and a range of 1030 to 762 76833 participants. The average age of participants was 15.95 years (ranging from 11 to 21).27–35 Four samples included only youth <18 years of age.27–29,34 Participants’ gender identity or assigned natal sex were reported in all studies.27–35 Participants’ sexual orientation was reported in 7 studies28,30–35: in 3 studies, only sexual attractions were reported28,31,34; in 3 studies as well, only sexual identities were reported32,33,35; and in 1 study, both were reported.30

Outcome Measures

Mental health outcomes were examined in all studies27–35: depressive symptoms were examined in 5 studies,28–32 anxiety symptoms were examined in 4,28,29,31,32 internalizing and externalizing symptoms were examined in 3,28,29,32 psychosocial functioning was examined in 2,27,29 hopelessness was examined in 1,31 perceived stress was examined in 1,34 suicidal ideation was examined in 2,30,35 and suicide attempts were examined in 2.33,35 Mental health outcomes were assessed by using reports from participants, parents or caregivers, clinicians, and researchers.27–35 In 2 studies, self-reported substance use outcomes were examined,32,34 including frequency of use and substance abuse and/or dependence symptoms. In 1 of the included studies, authors examined bullying victimization and being threatened or injured with a weapon on school property.35

Intervention Results

Painter et al32 found that the Children’s Mental Health Initiative, which provided coordinated networks of community-based services and supports across the country to children with serious emotional disturbances, significantly improved all measured outcomes throughout a 1-year time period for SGMY. This program decreased symptoms of anxiety, depression, global functioning impairment, internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and substance abuse and dependence symptoms among SGMY.32

De Vries et al28 showed in their 1-group pretest-posttest study that initiation of pubertal suppression reduced depressive, internalizing, and externalizing symptoms, but not anxiety symptoms. De Vries et al29 also conducted a follow-up study using data from a subset of these participants as they initiated crossgender hormones and gender affirmation surgery. By using a 1-group pretest-midtest-posttest study across 7.1 years, participants were assessed at baseline (before initiating puberty suppression), midintervention (just before initiating crossgender hormones), and postintervention (1 year after gender affirmation surgery).29 Over time, psychosocial functioning increased linearly, whereas internalizing and externalizing symptoms from the Child and Adult Behavior Checklists decreased linearly.29 Depressive symptoms and internalizing symptoms from the Youth and Adult Self-Reports decreased from baseline to midintervention but increased slightly at postintervention.29 For both measures of internalizing symptoms and externalizing symptoms from the Child and Adult Behavior Checklists, the percentage of participants in the clinically significant range decreased over time.29 Although the aforementioned results were similar for transmen and transwomen, some results were moderated by gender: anxiety and externalizing symptoms from the Youth and Adult Self-Reports decreased linearly for transmen but increased after gender affirmation surgery for transwomen.29

Costa et al27 compared GMY who received a psychological-only intervention to those who received a psychological support and puberty suppression intervention. The 2 nonrandomized groups did not significantly differ in average psychosocial functioning at any assessment point (ie, baseline, 6-, 12-, and 18-month follow-ups).27 Within-group analyses revealed that for participants in the psychological-only intervention group, average psychosocial functioning improved after initiating the psychological intervention and plateaued thereafter.27 For participants in the psychological and puberty suppression intervention group, average psychosocial functioning did not improve after initiation of the psychological intervention but did significantly improve after initiating puberty suppression.27

Diamond et al30 showed that SMY who participated in an in-person family-based therapy intervention had significant decreases in average depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation symptoms across the pretest, midtest, and posttest. Lucassen et al31 showed SMY who participated in the computerized cognitive behavioral therapy intervention also had significant decreases in average depressive symptoms (across 3 different measures), anxiety symptoms, and hopelessness from baseline to immediate postintervention. Average depressive symptoms plateaued from immediate postintervention to 3-month postintervention.31

According to a randomized controlled trial conducted by Schwinn et al,34 an online intervention aimed at reducing substance use revealed that compared with control participants, intervention participants had significantly lower perceived stress and past-month frequency of other drug use (ie, use of inhalants, club drugs, steroids, cocaine, methamphetamines, prescription drug, or heroin) at 3-month follow-up. However, there were no significant differences between intervention and control groups in past-month frequency of alcohol, cigarette, or marijuana use at 3-month follow-up.34

Raifman et al33 found after the implementation of a policy granting same-sex couples equivalent marriage rights as opposite-sex couples, there was a significant decline in past-year suicide attempt prevalence among SMY. The enactment of such policy induced a 14% relative decline in the proportion of SMY reporting at least 1 past-year suicide attempt.33 For heterosexual youth, the passage of same-sex marriage policy was also associated with a significant decline in past-year suicide attempt prevalence.33

Seelman and Walker35 found that the enactment of state-level general antibullying laws was associated with a reduction in bullying victimization among SMY. Although general antibullying laws were not associated with being threatened or injured with a weapon among all SMY, there was a protective association for general antibullying laws among sexual minority boys <16 years old.35 General antibullying laws were not associated with suicidal ideation or suicide attempts among SMY.35

Seelman and Walker35 also investigated changes in these outcomes related to the enactment of state-level antibullying laws that enumerated sexual orientation as a protected class. Enumerated antibullying laws were associated with reductions in bullying victimization among lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) youth and suicide attempts among SMY and questioning youth.35 However, enumerated antibullying laws were not associated with suicidal ideation or being threatened or injured with a weapon.35

Ratings on the Quality of Evidence

Table 2 reveals the methodologic quality of the studies rated across several dimensions.26 One study received a strong global rating,33 1 study received a moderate global rating,35 and 7 studies received weak global ratings.27–32,34 Regarding selection bias, 2 studies with probabilistic sampling were strong,33,35 and 7 studies were weak because their samples were not necessarily representative of their target populations or they had low or unreported participation rates.27–32,34 Study designs ranged from moderate to strong.27–35 The 1 study with a strong rating was a randomized controlled trial,34 and the studies with moderate ratings were interrupted time series designs33,35 or longitudinal study designs with 1 or 2 groups.27–32 Regarding confounders, 1 was strong,33 but all other studies were weak because the authors failed to control for important potential confounders such as age, sex, and race and/or ethnicity35 or only reported unadjusted associations.27–31,34 Blinding procedures (ie, blinding data collectors to participants’ intervention status and blinding participants to the study’s primary research question) were strong across 2 studies33,35 and moderate across 7 studies.27–32,34 Data collection methods were strong in 8 studies because they used valid and reliable measures.27–33,35 One study had weak data collection methods because it was unclear if the authors used valid and reliable measures.34 Withdrawals and dropouts were strong in 3 studies that had ≥80% of participants complete the final study assessment.30,31,34 Four remaining studies were rated as weak because of substantial attrition.27–29,32

TABLE 2.

Summary of Methodologic Quality Ratings by Study

| Source | Global Rating | Selection Bias | Study Design | Confounders | Blinding | Data Collection Method | Withdrawals and Dropouts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costa et al27 | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Weak |

| de Vries et al28 | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Weak |

| de Vries et al29 | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Weak |

| Diamond et al30 | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Strong |

| Lucassen et al31 | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Strong |

| Raifman et al33 | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Strong | Moderate |

| Painter et al32 | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Weak |

| Schwinn et al34 | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Strong |

| Seelman and Walker35 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate |

Methodologic assessments were determined according to the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies checklist.

Discussion

With this systematic review, we identified the scarcity of interventions for SGMY evaluated in peer-reviewed scientific literature. Specifically, we found 9 interventions for mental health problems,27–35 2 for substance use,32,34 and 1 for violence victimization.35 One study had strong methodologic quality and found that state-level marriage equality laws significantly reduced suicide attempts among SMY.33 One study had moderate methodologic quality and found that state-level general and enumerated antibullying laws significantly reduced bullying victimization for SMY.35 Although the other 7 interventions made significant improvements in mental health problems and substance use,27–32,34 these studies’ results must be interpreted cautiously because of suboptimal methodologic quality.26 For example, although it would be decidedly unethical to withhold medical care from youth who need it, the lack of a comparison or control group threatens internal validity. Without a comparison or control group, participants’ improvements may be attributable to pubertal maturation39 or historical social climate.40–42 By using comparison or control groups, authors can more accurately assess the direct benefit of the intervention under investigation. Altogether, this small collection of diverse evidence-based interventions is likely insufficient to mitigate the substantial population-level inequities present among SGMY in substance use, mental health problems, and violence victimization.

Our review, however, is not without limitations. It was impossible to include intervention evaluations still under review at scientific journals or evaluations still underway. In this review, we also do not capture interventions without evaluations or those with evaluations published outside of the peer-reviewed scientific literature. Conducting and publishing evaluations in the scientific peer-reviewed literature is important for both understanding intervention effectiveness and dissemination. For example, without a peer-reviewed publication of evaluation results, interventions cannot be included in national intervention registries (eg, the Evidence-Based Practices Resource Center), thereby hampering the widespread implementation of potentially effective interventions. Additionally, bias toward publishing only significant efficacious or effective results may have limited the number of studies included, potentially limiting our knowledge about ineffective interventions. Finally, studies evaluating the effectiveness of universal interventions likely include SGMY and GMY as participants; however, researchers must explicitly include items that assess sexual and gender minority statuses to test whether these interventions are also effective for SGMY.

There are likely many other substantial reasons why we found few interventions evaluated for SGMY, not the least of which are the unique barriers in reaching SGMY. Such barriers include SGMY being a minority of the population,43 the fact that SGMY are often still developing their identities and as a result may not be “out” yet,44,45 and structural barriers, such as the presence of anti-SGMY attitudes and policies42 and the historical lack of SGMY-affirmative school practices and funding directed toward SGMY health interventions.46,47

Despite these barriers, there are many ways to advance the field of SGMY intervention research for reducing substance use, mental health problems, and violence victimization. Investigators can:

examine the efficacy of existing interventions (eg, refs 48–50) that included youth in their studies but failed to meet our Cochrane-informed19,20 age eligibility criteria;

evaluate the efficacy of interventions designed and implemented by community-based organizations (eg, ref 51);

conduct outcome evaluations for interventions currently only examined via process evaluations (eg, ref 52);

conduct natural experiments and quasi-experimental studies for additional policy changes (such as those found in this review33,35);

adapt existing interventions (eg, refs 30,31) to incorporate SGMY-specific content;

test whether universal interventions targeting all youth (eg, ref 53) are efficacious specifically for SGMY; and

develop, implement, and evaluate new interventions specifically tailored for SGMY (eg, refs 34,54).

It remains unclear whether universal or targeted interventions are more effective at reducing SGMY health inequities, but findings from our review suggest that both approaches are likely beneficial.27–35 Moreover, as investigators begin to develop, implement, and test interventions among SGMY, they ought to draw on best practices from intervention science to advance the field more rapidly. Some of these practices include collaborating with participating community members to incorporate their perspectives into intervention development, implementation, and evaluation, which increases the intervention’s relevance and protections of participants’ rights55; using theoretical foundations of behavior change to build more efficacious interventions56; and carefully developing feasibility pilot studies used to document the intervention’s successes and failures to inform future intervention research of SGMY.57

Interventions can also incorporate knowledge gained from the extant epidemiological literature to increase intervention reach, target SGMY during specific periods of the life course, and incorporate specific population needs. Regarding intervention reach, interventions can target SGMY in myriad contexts: SGMY usually live with families (although living in homelessness is heightened among SGMY58) and also attend school for >1000 hours each year,59 providing ideal settings for implementing interventions with SGMY. Additionally, SGMY are present in afterschool programs, community-based organizations, sport programs, churches, and medical clinics. Because most youth use the Internet,60 Internet-based intervention methods may be a particularly effective way to reach SGMY. Prevention interventions may also benefit from targeting SGMY as early as possible in the life course because across all youth, bullying victimization is more prevalent at younger ages,6,61,62 and SGMY have earlier substance use initiation than their peers.6,63,64 Finally, SGMY are not homogenous: the needs of bisexual youth deserve particular attention because they are the largest SMY subgroup65 and often have worse health outcomes than their gay and lesbian counterparts.2–4,65 The needs of SGMY of racial and/or ethnic minority groups also warrant careful consideration because many health outcomes and risk factors vary by race and/or ethnicity among SGMY.63,66–68

Future interventions can also benefit from reducing known risk factors and enhancing protective and resilience factors to improve health among SGMY.38,69 Stigma and discrimination are the fundamental causes behind SGMY health inequities in substance use, mental health problems, and violence victimization70,71; thus, developing interventions to reduce stigma and discrimination is critical. Because stigma and discrimination are multidimensional, existing at multiple levels (ie, individual, interpersonal, organizational, and structural) and in multiple forms (ie, covert and overt biases),72 reducing stigma and discrimination for SGMY will require multilevel, multipronged approaches.38,73,74 Enhancing protective factors and resiliencies may also reduce SGMY health inequities. Such factors include adult and peer support, adaptive SGMY-specific coping strategies, and SGMY-affirmative school climates, programs curricula, and policies.37,65,75–82

Conclusions

With few effective interventions for SGMY, inequities in substance use, mental health problems, and violence victimization for SGMY are likely to persist. To advance the field of intervention science for SGMY more rapidly, researchers can engage in community-based research and use the extant literature to rigorously design, implement, and evaluate interventions, all in an effort to foster health equity for SGMY.

Glossary

- GMY

gender minority youth

- GnRH

gonadotropin-releasing hormone

- LGB

lesbian, gay, and bisexual

- SGMY

sexual and gender minority youth

- SMY

sexual minority youth

- WPATH

World Professional Association for Transgender Health

Footnotes

Dr Coulter led the study conceptualization and design, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of the article; Drs Egan, Kinsky, Eckstrand, Friedman, and Ms Frankeberger conducted data extraction and data interpretation and contributed to the writing and editing of the article; Ms Folb conducted the literature searches and contributed to the writing and editing of the article; Drs Mair, Markovic, Silvestre, Stall, and Miller contributed to the study conceptualization, data interpretation, and writing and editing of the article; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (award F31DA037647 to Dr Coulter), the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (TL1TR001858 to Dr Coulter), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (K01AA027564 to Dr Coulter), and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K24HD075862 to Dr Miller). The opinions expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the funders. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, et al. . Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: a meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction. 2008;103(4):546–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marshal MP, Dietz LJ, Friedman MS, et al. . Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: a meta-analytic review. J Adolesc Health. 2011;49(2):115–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Guadamuz TE, et al. . A meta-analysis of disparities in childhood sexual abuse, parental physical abuse, and peer victimization among sexual minority and sexual nonminority individuals. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(8):1481–1494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reisner SL, Greytak EA, Parsons JT, Ybarra ML. Gender minority social stress in adolescence: disparities in adolescent bullying and substance use by gender identity. J Sex Res. 2015;52(3):243–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coulter RWS, Bersamin M, Russell ST, Mair C. The effects of gender- and sexuality-based harassment on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender substance use disparities. J Adolesc Health. 2018;62(6):688–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark TC, Lucassen MF, Bullen P, et al. . The health and well-being of transgender high school students: results from the New Zealand adolescent health survey (Youth’12). J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(1):93–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veale JF, Watson RJ, Peter T, Saewyc EM. Mental health disparities among Canadian transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60(1):44–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garofalo R, Wolf RC, Kessel S, Palfrey SJ, DuRant RH. The association between health risk behaviors and sexual orientation among a school-based sample of adolescents. Pediatrics. 1998;101(5):895–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pérez-Stable EJ. Director’s message: sexual and gender minorities formally designated as a health disparity population for research purposes. 2016. Available at: https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/directors-corner/messages/message_10-06-16.html. Accessed November 8, 2017

- 11.US Department of Health and Human Services Healthy People 2020. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coulter R, Egan J, Folb B, Friedman MR, Kinsky S Interventions for preventing and reducing violence, mental health problems, and substance use for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: a systematic review. 2016. Available at: www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42016034164. Accessed July 15, 2018

- 13.Reeves BC, Higgins JP, Ramsay C, Shea B, Tugwell P, Wells GA. An introduction to methodological issues when including non-randomised studies in systematic reviews on the effects of interventions. Res Synth Methods. 2013;4(1):1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Cochrane Review Group What study designs can be considered for inclusion in an EPOC review and what should they be called? 2016. Available at: https://epoc.cochrane.org/sites/epoc.cochrane.org/files/public/uploads/Resources-for-authors2017/what_study_designs_should_be_included_in_an_epoc_review.pdf. Accessed January 2, 2017

- 15.Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9(11):e1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCambridge J, McAlaney J, Rowe R. Adult consequences of late adolescent alcohol consumption: a systematic review of cohort studies. PLoS Med. 2011;8(2):e1000413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merline AC, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Substance use among adults 35 years of age: prevalence, adulthood predictors, and impact of adolescent substance use. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(1):96–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gomez AM. Testing the cycle of violence hypothesis: child abuse and adolescent dating violence as predictors of intimate partner violence in young adulthood. Youth Soc. 2011;43(1):171–192 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richer L, Billinghurst L, Linsdell MA, et al. . Drugs for the acute treatment of migraine in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(4):CD005220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawton K, Witt KG, Taylor Salisbury TL, et al. . Interventions for self-harm in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(12):CD012013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JG, Matthews AK, McCullen CA, Melvin CL. Promotion of tobacco use cessation for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(6):823–831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Midgley G. Systemic Intervention: Philosophy, Methodology, and Practice. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cochrane Community Glossary. 2017. Available at: https://community-archive.cochrane.org/glossary. Accessed March 2, 2017

- 24.Lee JG, Ylioja T, Lackey M. Identifying lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender search terminology: a systematic review of health systematic reviews. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0156210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med. 2005;37(5):360–363 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. 1998. Available at: www.ephpp.ca/tools.html. Accessed July 15, 2017

- 27.Costa R, Dunsford M, Skagerberg E, Holt V, Carmichael P, Colizzi M. Psychological support, puberty suppression, and psychosocial functioning in adolescents with gender dysphoria. J Sex Med. 2015;12(11):2206–2214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Vries AL, Steensma TD, Doreleijers TA, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Puberty suppression in adolescents with gender identity disorder: a prospective follow-up study. J Sex Med. 2011;8(8):2276–2283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Vries AL, McGuire JK, Steensma TD, Wagenaar EC, Doreleijers TA, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Young adult psychological outcome after puberty suppression and gender reassignment. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):696–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diamond GM, Diamond GS, Levy S, Closs C, Ladipo T, Siqueland L. Attachment-based family therapy for suicidal lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents: a treatment development study and open trial with preliminary findings. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2012;49(1):62–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lucassen MF, Merry SN, Hatcher S, Frampton CM. Rainbow SPARX: a novel approach to addressing depression in sexual minority youth. Cognit Behav Pract. 2015;22(2):203–216 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Painter KR, Scannapieco M, Blau G, Andre A, Kohn K. Improving the mental health outcomes of LGBTQ youth and young adults: a longitudinal study. J Soc Serv Res. 2018;44(2):223–235 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raifman J, Moscoe E, Austin SB, McConnell M. Difference-in-differences analysis of the association between state same-sex marriage policies and adolescent suicide attempts [published corrections appear in JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(4):399 and in JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(6):602]. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(4):350–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwinn TM, Thom B, Schinke SP, Hopkins J. Preventing drug use among sexual-minority youths: findings from a tailored, web-based intervention. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(5):571–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seelman KL, Walker MB. Do anti-bullying laws reduce in-school victimization, fear-based absenteeism, and suicidality for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning youth? J Youth Adolesc. 2018;47(11):2301–2319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.The World Professional Association for Transgender Health Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender nonconforming people, version 7. 2011. Available at: https://www.wpath.org/media/cms/Documents/SOC v7/Standards of Care_V7 Full Book_English.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2017