Abstract

Canine brucellosis is an infectious disease that produces reproductive disease in both males and females. Although Brucella canis is more common, the infection by Brucella abortus is more frequent in dogs sharing habitats with livestock and wild animals. We decided to investigate the role of dogs in the maintenance of Brucella spp. in the Pantanal wetland. Serum and whole blood samples were collected from 167 dogs. To detect antibodies against B. abortus and B. canis, buffered acidified plate antigen (BAPA) and agar gel immunodiffusion (AGID) tests were performed. To detect Brucella spp., B. abortus and B. canis DNA, PCR was performed using the bcsp31, BruAb2_0168, and BR00953 genes, respectively. To confirm the PCR results, three bcsp31 PCR products were sequenced and compared with sequences deposited in GenBank. The seropositivity rates of 7.8% and 9% were observed for the AGID and BAPA tests, respectively. Positivity rates of 45.5% and 10.8% were observed when testing bcsp31 and BruAb2_0168, respectively, while there was no positivity for BR00953. The sequenced products had 110 base pairs that aligned with 100% identity to B. abortus, B. canis, and B. suis. Considering our results, dogs may be acting as maintenance hosts of Brucella spp. in the Pantanal region.

Keywords: Brucella spp., Reservoir host, Serology, Molecular tests, Pantanal

Introduction

Canine brucellosis is an infectious disease that produces late abortions in females, epididymitis, and prostatitis in males, as well as nonspecific symptoms, such as fever, lymphadenitis, lameness, uveitis, polyarthritis, discospondylitis, paresis, and ataxia [1]. The etiological agent Brucella canis is transmitted through direct contact with genitourinary secretions of infected dogs, aborted placental and fetal material, and vaginal, prostate and seminal fluids [1].

Outbreaks of canine brucellosis have been recently reported around the world, resulting in economic losses for kennel owners [2–6]. Moreover, the occurrence of B. canis in humans suggests that this infectious agent is an emergent zoonosis, with veterinarians and animal handlers being particularly at risk [7–12].

Although B. canis is typically associated with dogs, three other species have been reported to infect dogs, B. melitensis, B. suis, and B. abortus [13–18]. Of these additional species, B. abortus is most commonly found in dogs, especially in enzootic environments where domestic animals are in close contact with livestock and wildlife species [19, 20].

The Pantanal is the largest wetland ecosystem in the world and is a region in which cattle ranching is the principal economic activity, with an estimated cattle population of four million [21, 22]. In this region, distinctive flood and dry seasons occur that greatly vary in intensity from year to year [21]. With approximately 160,000 ha in the core of South America, this region shelters a rich and dense wild mammalian fauna that shares the same habitat with domestic animals [22]. Cases of brucellosis caused by B. abortus have been reported in the Pantanal region that affect some species of domestic animals and wildlife [23–27]. Although Furtado et al. (2015) [27] previously reported that dogs are exposed to Brucella spp. in the Pantanal, as determined by serology, the role of this domestic species in the enzootic persistence of brucellosis in this region remains unknown. In this sense, we aimed to detect Brucella spp. in dogs in the Pantanal wetland using serological and molecular tests, identifying the role of dogs in the maintenance of Brucella spp.

Material and methods

Samples

Between August 2013 and July 2014, we collected serum and whole blood samples from 167 dogs from the Nhecolandia subregion (18° 59′ 15″ S; 56° 37′ 03″), of the southeastern Pantanal. The sample size was determined by a non-probabilistic method. All procedures were performed in accordance with the Ethics Committee for Animal Use of the Universidade Católica Dom Bosco (001/2013).

Serology

Agar gel immunodiffusion (AGID) and buffered acidified plate antigen (BAPA) tests were performed to detect antibodies against B. canis and B. abortus, respectively. The antigen used in the AGID test consisted of proteins and lipopolysaccharides from B. ovis (strain Reo 198), and the antigen used in the BAPA assay consisted of inactivated B. abortus (strain 1119–3), both produced by the Instituto de Tecnologia do Paraná (TECPAR®). Both techniques were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Molecular tests

The DNA extraction was performed according to Sambrook and Russel (2001) [28]. The concentration and purity of the extracted DNA were determined using a spectrophotometer (Biodrop® Denville Scientific Inc. Holliston, MA 01746) at an absorbance of 260 nm and by electrophoresis. PCR was performed using the primers listed in Table 1. As positive controls, we used B. abortus (strain S2308) and B. canis (strain SG 771) genomic DNA. The products were subjected to electrophoresis at 100 V for 40 min on a 1.5% gel agarose, which was then stained with ethidium bromide, visualized under an ultraviolet transilluminator, and documented.

Table 1.

Primers used in molecular tests to detect different Brucella species in dogs from the Pantanal region

| Primer | Species | Sequence (5′–3′) | Amplicon | Region | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BruAb2_0168f | B. abortus | GCACACTCACCTTCCACAACAA | 81 bp | Chromosome II, BruAb2_0168locus | [29] |

| BruAb2_0168r | CCCCGTTCTGCACCAGACT | ||||

| B4f | Brucella spp. | TGGCTCGGTTGCCAATATCAA | 223 bp | bcsp 31 | [30] |

| B5r | CGCGCTTGCCTTTCAGGTCTG | ||||

| BR00953f | B. canis, B. suis e, B. neotomae | GGAACACTACGCCACCTTGT | 272 bp | Chromosome I, polA | [31] |

| BR00953r | GATGGAGCAAACGCTGAAG |

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

For sequencing, we used the amplified products from the bcsp31 PCR due to the greater number of base pairs present compared to the BruAb2_0168 products. Three PCR products with high concentrations and absence of nonspecific bands were purified with Kit Qia Quick PCR purification columns (Qiagen® Hilden, Alemanha) and sequenced with the same forward and reverse primers used in the initial PCR amplification. A Big Dye terminator cycle sequencing kit version 3.1 (Applied Biosystems® Foster, California, EUA) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

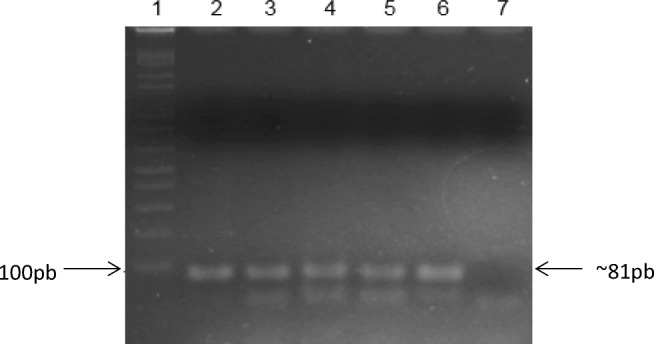

To determine if the amplified products matched Brucella spp. sequences, a basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) was used, comparing the sequenced samples to sequences deposited in GenBank. An alignment of the bcsp31amplified sequences with some Brucella species, including B. abortus (CP008774.1), B. suis (CP009096), and B. canis (CP007629), was performed using Clustal W (ftp://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/software/clustalw2/).

Statistical analysis

Cohen’s kappa statistic was used to evaluate the degree of concordance between all diagnostic assays with positive results using R version 3.3.1 program [32].

Results

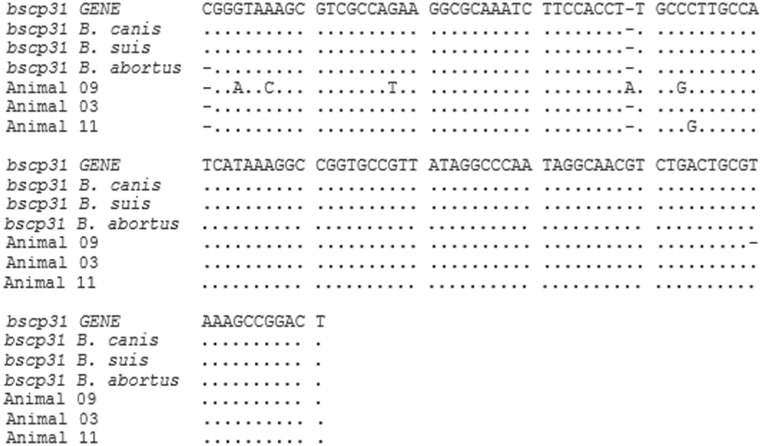

We observed a 7.8% (13/167) seropositivity rate using the AGID test (CI = 2.24–9.55%) and a 9% (15/167) seropositivity rate using the BAPA test (CI = 5.29–14.64%) (Table 2). All samples testing positive by AGID tested negative using BAPA and vice versa. Regarding the molecular tests, using the B4/B5primer pair, 45.5% (76/167) (CI = 37.85–53.37%) of dogs tested positive, while using the primers to amplifyBruAb2_0168, 10.8% (18/167) (CI = 6.69–16.74%) of dogs tested positive (Fig. 1). There were no positive results using the primers to amplifyBR00953.

Table 2.

Frequency of dogs testing positive in different diagnostic methods. Results are expressed by the number of positive animals followed by the percent testing positive

| Diagnostic test | Positivity | Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| AGID | 13/7.8% | (CI = 2.24–9.55%) |

| BAPA | 15/9% | (CI = 5.29–14.64%) |

| B4/B5 | 76/45.5% | (CI = 37.85–53.37%) |

| BruAb2_0168 | 18/10.7% | (CI = 6.69–16.74%) |

Fig. 1.

Electrophoresis of the PCR product in a 2% agarose gel. Lane 1: 100 bp molecular marker (Invitrogen®); lanes 2 to 5: positive samples of BruAb2_0168 (B. abortus); 6: positive control; 7: negative control

Comparisons among the different diagnostic tests showed a slight agreement between the B4/B5 and BruAb_0168PCRs (κ 0.07, CI = − 0.09–0.23), but no agreement between the BAPA test and the BruAb_0168PCR (κ − 0.04, CI = − 0.37–0.29) or between the AGID test and the BAPA test (κ − 0.06, CI = − 0.47–0.34).

The three sequencedB4/B5 PCR products had 110 bp that aligned with 100% of identity to the bcsp31 genes of B. abortus, B. canis, and B. suis (best hits nr access | e-value 3e-49) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Multiple sequence alignment of bscp31 Brucella genes (from samples 03, 09, and 11, and B. canis, B. abortus, and B. suis from GenBank) using the MEGA 6.0 program

Discussion

We demonstrated that, in addition to reports of dogs having been exposed to Brucella spp. in the Pantanal wetland [27], they can also present bacteria in the bloodstream, as shown by the positive results from the molecular methods used in this study. Furthermore, this is the first study that reports the sequencing of the Brucella bcsp 31 gene from dogs in the Pantanal region.

This gene codifies the Brucella cell surface 31 kDa protein and has been used as a target since the end of the 1980s to detect Brucella spp. [30, 33], providing high diagnostic sensitivity and specificity [34, 35]. Brucella spp. show a high degree of phylogenetic similarity to a free-living genus of saprophytes Ochrobactrum spp. [36], and the B4/B5 primers can hybridize to the genomes of these species [37]; however, false-positive PCR results can be discarded when examining natural infections, since this bacterium does not replicate within eukaryotic cells [38].

The difference in the detection of Brucella by B4/B5 (45.5%) and BruAb2_0168 (10.7%) PCRs may be explained by their specificity. Indeed, unlike the B4/B5primer set, the BruAb2_0168 primers detect a region of a transposon insertion site that is only present in B. abortus strains [39]. Considering that BR00953 detect B. canis, B. suis, and B. neotomae [31, 40], and no positive results were generated with this primer, dogs in the studied area may be infected by another species of Brucella.

Although our results demonstrated an alignment between B. abortus, B. canis, and B. suis (Fig. 2), it is not enough to discriminate Brucella species because different species of Brucella present a high degree of similarity (98 to 99%) [41]. Nevertheless, our sequencing analysis confirmed that Brucella spp. was found infecting dogs in the Pantanal region.

The lack of agreement between the serological and molecular diagnostic methods, as demonstrated by the Kappa test (p > 0.05), is acceptable in natural infections because detectable amounts of IgG in the serological tests are only expected during the chronic phase of infection. Thus, during the acute phase, which is characterized by bacteremia and an absence of detectable IgG, positive PCR results and negative serological results are expected. In contrast, because of the absence of bacteria in the bloodstream of infected animals during the chronic phase, negative PCR results and positive serological results would be expected. As our statistical analysis showed a lack of agreement between the serological and molecular tests, the diagnosis of Brucella spp. infections must be done by a combination of both methods.

In the case of B. canis infections, our results showed that seropositive dogs are chronically infected, since they did not test positive by PCR using the BR00953 oligonucleotides. Although whole blood is considered a good template for the isolation and molecular detection of B. canis due to the prolonged initial bacteremia produced by this species, the sampling of animals during the chronic phase may cause false-negative results. After an initial oronasal exposure, dogs are bacteremic for 7–30 days (acute phase); in the first 3–4 months, the bacteremia declines, and the organisms become localized in the targeted reproductive tissues, with intermittent bacteremic episodes that can last for years (chronic phase) [42]. As described above, the interpretation of the diagnostic results should be made with an attempt to yield a precise diagnosis.

The infection of dogs by B. abortus in the Pantanal wetland could occur via the oral route for two reasons. First, dogs are fed raw meat from slaughtered cattle, and strains of B. abortus produce urease that protects the bacteria during its passage through the stomach [16, 20, 43]. Second, since antibodies against B. abortus S19, which is used to immunize livestock [44], can be detected via a BAPA test [45], we did not rule out the presence of this strain in the sampled animals because vaccinated cattle can act as a source of B. abortus S19 contamination of the environment [46, 47]. This is especially the case during periods of flooding, when domestic animals and wildlife come into close contact [22], favoring the horizontal transmission.

In the Pantanal wetland, B. abortus has already been identified in crab-eating foxes (Cerdocyon thous), brown-nosed coatis (Nasua nasua), and pampas deer (Ozotoceros bezoarticus) [25, 26], and its occurrence in cattle was reported [23, 24]. Thus, the contact of dogs with wildlife and cattle may promote the transmission of B. abortus among them, as was reported in Egypt [20]. Since infected dogs can eliminate Brucella spp. through secretions and excretions, especially during recurrent episodes of bacteremia [42], this domestic host species may have an important role in the spread of Brucella spp. to livestock in the Pantanal region.

Considering our results, dogs in the Pantanal wetland may be acting as maintenance hosts for Brucella spp. in the natural environment. The dogs in this region would likely be primarily infected by B. abortus due to close contact with infected livestock and wildlife, which often occurs during the wet season.

Acknowledgements

We like to thanks Dra. Lara Borges Keid, who provided the positive controls used in molecular tests.

Compliance with ethical standards

All procedures were performed in accordance with the Ethics Committee for Animal Use of the Universidade Católica Dom Bosco (001/2013).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Carmichael LE, Green EG. Canine brucellosis. In: Greene CE, editor. Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1990. pp. 248–257. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brennan SJ, Ngeleka M, Philibert HM, Forbes LB, Allen AL. Canine brucellosis in a Saskatchewan kennel. Can Vet J. 2008;49(7):703–708. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gyuranecz M, Szeredi L, Rónai Z, Dénes B, Dencso L, Dán Á, Pálmai N, Hauser Z, Lami E, Makrai L, Erdélyi K, Jánosi S. Detection of Brucella canis-induced reproductive diseases in a kennel. J Vet Diagn Investig. 2011;23(1):143–147. doi: 10.1177/104063871102300127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hofer E, Bag ZN, Revilla-Fern Ndez S, Melzer F, Tomaso H, Pez-Go L, II, et al. First detection of Brucella canis infections in a breeding kennel in Austria. New Microbiol. 2012;35(4):507–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gyuranecz M, Rannals BD, Allen CA, Jánosi S, Keim PS, Foster JT. Within-host evolution of Brucella canis during a canine brucellosis outbreak in a kennel. BMC Vet Res. 2013;9:76. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-9-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaden R, Ågren J, Båverud V, Hallgren G, Ferrari S, Börjesson J, Lindberg M, Bäckman S, Wahab T. Brucellosis outbreak in a Swedish kennel in 2013: determination of genetic markers for source tracing. Vet Microbiol. 2014;174(3–4):523–530. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lucero NE, Corazza R, Almuzara MN, Reynes E, Escobar GI, Boeri E, et al. Human Brucella canis outbreak linked to infection in dogs. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138(2):280–285. doi: 10.1017/S0950268809990525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nomura A, Imaoka K, Imanishi H, Shimizu H, Nagura F, Maeda K, Tomino T, Fujita Y, Kimura M, Stein GH. Human Brucella canis infections diagnosed by blood culture. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(7):1183–1185. doi: 10.3201/eid1607.090209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angel MO, Ristow P, Ko AI, Di-Lorenzo C. Serological trail of Brucella infection in an urban slum population in Brazil. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2012;6(9):675–679. doi: 10.3855/jidc.2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marzetti S, Carranza C, Roncallo M, Escobar GI, Lucero NE. Recent trends in human Brucella canis infection. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;36:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krueger WS, Lucero NE, Brower A, Heil GL, Gray GC. Evidence for unapparent Brucella canis infections among adults with occupational exposure to dogs. Zoonoses Public Health. 2014;61(7):509–518. doi: 10.1111/zph.12102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dentinger CM, Jacob K, Lee LV, Mendez HA, Chotikanatis K, McDonough PL, et al. Human Brucella canis infection and subsequent laboratory exposures associated with a puppy, New York City, 2012. Zoonoses Public Health. 2015;62(5):407–414. doi: 10.1111/zph.12163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forbes LB. Brucella abortus infection in 14 farm dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1990;196(6):911–916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baek BK, Lim CW, Rahman MS, Kim CH, Oluoch A, Kakoma I. Brucella abortus infection in indigenous Korean dogs. Can J Vet Res. 2003;67(4):312–314. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hinic V, Brodard I, Petridou E, Filioussis G, Contos V, Frey J, et al. Brucellosis in a dog caused by Brucella melitensis Rev 1. Vet Microbiol. 2010;141(3–4):391–392. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cadmus SI, Adesokan HK, Ajala OO, Odetokun WO, Perrett LL, Stack JA. Seroprevalence of Brucella abortus and B. canis in household dogs in southwestern Nigeria: a preliminary report. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 2011;82(1):56–57. doi: 10.4102/jsava.v82i1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mor SM, Wiethoelter AK, Lee A, Moloney B, James DR, Malik R. Emergence of Brucella suis in dogs in New South Wales, Australia: clinical findings and implications for zoonotic transmission. BMC Vet Res. 2016;12(1):199. doi: 10.1186/s12917-016-0835-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.James DR, Golovsky G, Thornton JM, Goodchild L, Havlicek M, Martin P, Krockenberger MB, Marriott DJE, Ahuja V, Malik R, Mor SM. Clinical management of Brucella suis infection in dogs and implications for public health. Aust Vet J. 2017;95(1–2):19–25. doi: 10.1111/avj.12550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Truong LQ, Kim JT, Yoon BI, Her M, Jung SC, Hahn TW. Epidemiological survey for Brucella in wildlife and stray dogs, a cat and rodents captured on farms. J Vet Med Sci. 2011;73(12):1597–1601. doi: 10.1292/jvms.11-0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wareth G, Melzer F, El-Diasty M, Schmoock G, Elbauomy E, Abdel-Hamid N, et al (2017) Isolation of Brucella abortus from a dog and a cat confirms their biological role in re-emergence and dissemination of bovine brucellosis on dairy farms. Transbound Emerg Dis 64:e27–e30 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Pozer CG, Nogueira F. Flooded native pastures of the northern region of the Pantanal of Mato Grosso: biomass and primary productivity variations. Braz J Biol. 2004;64(4):859–866. doi: 10.1590/S1519-69842004000500016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alho CJ, Camargo G, Fischer E. Terrestrial and aquatic mammals of the Pantanal. Braz J Biol. 2011;71(Suppl 1):297–310. doi: 10.1590/S1519-69842011000200009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chate SC, Dias RA, Amaku M, Ferreira F, Moraes GM, Costa Neto AA, Monteiro LARC, Lôbo JR, Figueiredo VCF, Gonçalves VSP, Ferreira Neto JS. Epidemiologic situation of bovine brucellosis in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec. 2009;61(Suppl 1):46–55. doi: 10.1590/S0102-09352009000700007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Negreiros RL, Dias RA, Ferreira F, Ferreira Neto JS, Gonçalvez VSP, Silva MCP, et al. Epidemiologic situation of bovine brucellosis in the state of Mato Grosso. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec. 2009;61(Suppl 1):56–65. doi: 10.1590/S0102-09352009000700008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elisei C, Pellegrin A, Tomas WM, Soares CO, Araújo FR, Funes-Huacca ME, Rosinha GMS. Molecular evidence of Brucella sp. in deer (Ozotoceros bezoarticus) of the southern Pantanal. Pesq Vet Bras. 2010;30(6):503–509. doi: 10.1590/S0100-736X2010000600006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dorneles EMS, Pellegrin AO, Shabib-Péres IAHF, Mathias LA, Mourão G, Bianchi RC, et al. Serology for brucellosis in free-ranging crab-eating foxes (Cerdocyon thous) and brown-nosed coatis (Nasua nasua) from Brazilian Pantanal. Ciência Rural. 2014;44(12):2193–2196. doi: 10.1590/0103-8478cr20131167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Furtado MM, Gennari SM, Ikuta CY, Jácomo AT, de Morais ZM, Pena HF, et al. Serosurvey of smooth Brucella, Leptospira spp. and Toxoplasma gondii in free-ranging jaguars (Panthera onca) and domestic animals from Brazil. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0143816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambrook J, Russel DW. Rapid isolation of yeast DNA. In: Sambrook J, Russel DW, editors. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 2001. pp. 631–632. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hinic V, Brodard I, Thomann A, Cvetnic Ž, Makaya PV, Frey J, et al. Novel identification and differentiation of Brucella melitensis, B. abortus, B. suis, B. ovis, B. canis, and B. neotomae suitable for both conventional and real-time PCR systems. J Microbiol Methods. 2008;75(2):375–378. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baily GG, Krahn JB, Drasar BS. Stoker NG. Detection of Brucella melitensis and Brucella abortus by DNA amplification. J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;95(4):271–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ortiz LF, Muskus C, Sánchez MM, Olivera M. Identification of Brucella canis group 2 in Colombian kennels. Rev Colom Cienc Pecua. 2012;25(4):615–619. [Google Scholar]

- 32.R Main Development Team (2011) A: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. URL: http://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 3 Dec 2017

- 33.Mayfield JE, Bricker BJ, Godfrey H, Crosby RM, Knight DJ, Halling SM, et al. The cloning, expression, and nucleotide sequence of a gene coding for an immunogenic Brucella abortus protein. Gene. 1988;63(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90540-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Queipo-Ortuño MI, Colmenero JD, Baeza G, Morata P. Comparison between light cycler real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay with serum and PCR-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with whole blood samples for the diagnosis of human brucellosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(2):260–264. doi: 10.1086/426818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zamanian M, Hashemi Tabar GR, Rad M, Haghparast A. Evaluation of different primers for detection of Brucella in human and animal serum samples by using PCR method. Arch Iranian Med. 2015;18(1):44–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gee JE, De BK, Levett PN, Whitney AM, Novak RT, Popovic T. Use of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for rapid confirmatory identification of Brucella isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(8):3649–3654. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.8.3649-3654.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Da Costa M, Guillou JP, Garin-Bastuji B, Thiébaud M, Dubray G. Specificity of six gene sequences for the detection of the genus Brucella by DNA amplification. J Appl Bacteriol. 1996;81(3):267–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1996.tb04328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scholz HC, Pfeffer M, Witte A, Neubauer H, Al Dahouk S, Wernery U, et al. Specific detection and differentiation of Ochrobactrum anthropi, Ochrobactrum intermedium and Brucella spp. by a multi-primer PCR that targets the recA gene. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57(Pt 1):64–71. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47507-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cha SB, Rayamajhi N, Lee WJ, Shin MK, Jung MH, Shin SW, Kim JW, Yoo HS. Generation and envelope protein analysis of internalization defective Brucella abortus mutants in professional phagocytes, RAW 264.7. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2012;64(2):244–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.García-Yoldi D, Marín CM, de Miguel MJ, Muñoz PM, Vizmanos JL, López-Goñi I, et al. Multiplex PCR assay for the identification and differentiation of all Brucella species and the vaccine strains Brucella abortus S19 and RB51 and Brucella melitensis Rev1. Clin Chem. 2006;52(4):779–781. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.062596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al Dahouk S, Hofer E, Tomaso H, Vergnaud G, Le Flèche P, Cloeckaert A, et al. Intraspecies biodiversity of the genetically homologous species Brucella microti. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78(5):1534–1543. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06351-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hollett RB. Canine brucellosis: outbreaks and compliance. Theriogenology. 2006;66(3):575–587. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sangari FJ, Seoane A, Rodríguez MC, Agüero J, García Lobo JM. Characterization of the urease operon of Brucella abortus and assessment of its role in virulence of the bacterium. Infect Immun. 2007;75(2):774–780. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01244-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brasil. Programa Nacional de Controle e Erradicação da Brucelose e da Tuberculose Animal – PNCEBT. Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento, Brasília, 188pp, 2006

- 45.Nielsen K. Diagnosis of brucellosis by serology. Vet Microbiol. 2002;90(1–4):447–459. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(02)00229-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miyashiro S, Scarcelli E, Piatti RM, Campos FR, Vialta A, Keid LB, Dias RA, Genovez ME. Detection of Brucella abortus DNA in illegal cheese from São Paulo and Minas Gerais and differentiation of B19 vaccinal strain by means of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) Braz J Microbiol. 2007;38(1):17–22. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822007000100005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pacheco WA, Genovez ME, Pozzi CR, Silva LM, Azevedo SS, Did CC, et al. Excretion of Brucella abortus vaccine B19 strain during a reproductive cycle in dairy cows. Braz J Microbiol. 2012;43(2):594–601. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822012000200022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]