Abstract

Neuronal polarity is involved in multiple developmental stages, including cortical neuron migration, multipolar-to-bipolar transition, axon initiation, apical/basal dendrite differentiation, and spine formation. All of these processes are associated with the cytoskeleton and are regulated by precise timing and by controlling gene expression. The P-Rex1 (phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate dependent Rac exchange factor 1) gene for example, is known to be important for cytoskeletal reorganization, cell motility, and migration. Deficiency of P-Rex1 protein leads to abnormal neuronal migration and synaptic plasticity, as well as autism-related behaviors. Nonetheless, the effects of P-Rex1 overexpression on neuronal development and higher brain functions remain unclear. In the present study, we explored the effect of P-Rex1 overexpression on cerebral development and psychosis-related behaviors in mice. In utero electroporation at embryonic day 14.5 was used to assess the influence of P-Rex1 overexpression on cell polarity and migration. Primary neuron culture was used to explore the effects of P-Rex1 overexpression on neuritogenesis and spine morphology. In addition, P-Rex1 overexpression in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) of mice was used to assess psychosis-related behaviors. We found that P-Rex1 overexpression led to aberrant polarity and inhibited the multipolar-to-bipolar transition, leading to abnormal neuronal migration. In addition, P-Rex1 overexpression affected the early development of neurons, manifested as abnormal neurite initiation with cytoskeleton change, reduced the axon length and dendritic complexity, and caused excessive lamellipodia in primary neuronal culture. Moreover, P-Rex1 overexpression decreased the density of spines with increased height, width, and head area in vitro and in vivo. Behavioral tests showed that P-Rex1 overexpression in the mouse mPFC caused anxiety-like behaviors and a sensorimotor gating deficit. The appropriate P-Rex1 level plays a critical role in the developing cerebral cortex and excessive P-Rex1 might be related to psychosis-related behaviors.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12264-019-00408-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: P-Rex1, Neurodevelopment, Polarity, Lamellipodia, Psychosis-related behavior

Introduction

The function of mammalian cerebral cortex is closely related to neurodevelopment, including neuronal proliferation and migration, as well as axon/dendrite polarization and spine formation [1, 2], all of which are important for establishing neural circuits and indispensable for brain functions [3, 4]. Recent studies have revealed that neuronal polarity is critical in many developmental stages, such as cortical neuron migration, axon initiation, apical/basal dendrite differentiation, and spine formation [5, 6]. So far, abnormal neuronal polarity-related developmental phenotypes have been found in many neuropsychiatric diseases, such as lissencephaly [7–9], epilepsy [10, 11], schizophrenia [12–14], and autism [15, 16]. For example, altered neuronal polarity and position have been found in patients with schizophrenia [17, 18]. Patients with autism also display irregular lamination and aberrant neuron size and density [19–21]. However, although great progress has been made in understanding the relationship between brain disorders and neurodevelopment, the key mechanisms remain unclear.

Postmortem brain research and neuroimaging studies have revealed that neuropsychiatric diseases are associated with the cerebral cortex, especially the function of medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) [20, 22]. Relevant processes include neuronal migration [23, 24] and dendrite and dendritic spine development [25], as well as disruption of the neuronal cytoskeleton [26, 27], which plays a vital role in neuronal physiology by sustaining the polarity of structure and highly dissymmetric neuronal morphology [28]. The coordination of actin and microtubules, which directs neuronal morphogenesis including growth cone advancing and filopodia/lamellipodia turning, has been shown to be involved in neuronal migration, axon/dendrite polarization, and synapse formation [29, 30]. Studies have discovered that neuronal polarity is regulated by genes related to cytoskeletal regulation pathways, such as myocardin-related transcription factors [31], nerve growth factor [32], and the Rho GTPase-related signaling pathway [33], which are known to regulate actin and microtubule interactions as well as the establishment of neuronal polarity. Nevertheless, the underlying mechanism has not yet been entirely clarified. Thus, it is of great importance to explore the exact functions of new genes in neurodevelopment.

As one of the upstream signaling pathways of Rho-family GTPases, phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent Rac exchange factor 1 (P-Rex1) exerts its guanine nucleotide exchange factor activity due to the Rac small GTPase to undergo rapid spatiotemporally coordinated cycles of activation and inactivation, thereby regulating key aspects of actin cytoskeletal dynamics. P-Rex1 regulates cell motility and migration in polarized and non-polarized cells, including melanoma cells [34], neutrophils [35], PC12 cells, and cultured cortical neurons [36]. In polarized cells such as neurons, P-Rex1 knockout causes the complete loss of F-actin polymerization, while its overexpression results in excessive F-actin polymerization and decreased neurite differentiation in culture [37].

In mouse brains, P-Rex1 is strongly expressed in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum [36]. Mice without P-Rex1 (P-Rex1−/−) exhibit defects in Purkinje cell dendrite morphology and display cerebellar dysfunction [38]. In addition, our group previously found that P-Rex1−/− mice show autism-like social behavior, and altered AMPA receptor endocytosis resulting in long-term depression in the CA1 region of the hippocampus [39]. In the cerebral cortex, dysregulation of P-Rex1 leads to the abnormal migration of embryonic cerebral cortical neurons in mice [36]. However, the influence of P-Rex1 overexpression on neuronal migration, neurite outgrowth, and spine development in the cerebral cortex and the psychosis-related behaviors in mice remain unclear and need to be further investigated.

Therefore, in this study, we set out to explore the effects of P-Rex1 overexpression on cerebral development in mice, including its role in neuronal development in vitro and in vivo, as well as mouse behaviors.

Methods and Materials

Animals

The Department of Laboratory Animal Science at Peking University Health Science Center provided the animals for our study. Their living conditions were as follows: temperature, (22 ± 1) °C; relative humidity, (50 ± 1)%; a 12/12-h light/dark cycle; and food and water ad libitum. All animal experiments were performed in strict accordance with the Peking University institutional animal care and use guidelines and approved by the Animal Care Committee.

The day when vaginal plug was detected was defined as embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5). Postnatal day 0 (P0) was assumed to be E19. ICR mice were used for in vivo electroporation and neuron culture; male C57BL/6 mice were used for virus injection and behavioral tests; and Thy1-GFP transgenic mice on the C57BL/6 background were used for spine measurements in vivo.

Plasmids

The pcDNA3-Myc-P-Rex1 plasmid was a gift from Dr. Heidi Welch (The Babraham Institute, Cambridge, UK). The Myc-P-Rex1 encoding sequence was cloned into the pCAGGS-IRES-EGFP vector (a gift from Prof. Yuqiang Ding, Tongji University, Shanghai, China). The plasmid pCAGGS-IRES-EGFP was used as the Mock plasmid. In addition, Myc-P-Rex1 was cloned into NeuroD: IRES-EGFP plasmid (a gift from Dr. Franck Polleux, Neuroscience Center, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, USA).

Viral Vector

The P-Rex1 overexpression lentivirus, pLenti-hSyn-myc-prex1, was provided by OBiO Technology Corp., Ltd (Shanghai, China). The mock virus was pLenti-hsyn-mcherry (The plasmid for virus production was a gift from Prof. Zilong Qiu, Institute of Neuroscience, Shanghai Institute of Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China).

Antibodies

The primary antibodies used were as follows: rabbit anti-GFP (Invitrogen, 1:2000, Carlsbad, CA, USA), rabbit anti–βIII tubulin (Cell Signaling, 1:1000, Danvers, MA, USA), mouse monoclonal anti-Nestin (Millipore, 1:100, Billerica, MA, USA), rabbit monoclonal anti-GRASP65 (Abcam, 1:1000, Cambridge, MA, USA). F-actin was stained with Alexa-555 phalloidin (Molecular Probes, 1:100), apoptosis was analyzed using a TUNEL staining Kit (Roche, Southern San Francisco, Californi), nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Sigma-Aldrich, 1:2000, St. Louis, MO,USA), Bovine serum albumin (BSA, 3%) and TritonX-100 (0.3%) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Mouse P-Rex1 monoclonal antibody (1:500) was generated as previously described [39].

The secondary antibodies for immunostaining were Alexa 488 or 555 anti-rabbit IgG and Alexa 488 or 555 anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen, 1:500, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

In Utero Electroporation

Pregnant ICR mice at E14.5 were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (40 μg/g body weight). Then, the abdomen was sterilized and an incision was made to expose the uterus. A high concentration of plasmid DNA with Fast Green (0.01%, Fluka) was injected into the lateral ventricles of intrauterine embryos through a polished glass micropipette. Mock (2 μg/μL) or P-Rex1 OE plasmids (2 μg/μL) with CAG-driven enhanced green fluorescent protein expression vector (CAG-EGFP) were used for in utero electroporation. The electroporator (ECM 830, BTX Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA) parameters were as follows: 31 V, 50 ms, 950-ms intervals, 4 times. The uterus was then returned to the peritoneal cavity and the abdominal wall and skin were sutured. Electroporated mice were sacrificed at E16.5 or P0.

Immunostaining

Animals were anesthetized and embryos were collected at E16.5 or P0. Embryonic brains were fixed in 4% PFA (paraformaldehyde) at 4 °C overnight, then transferred into 30% (wt/vol) sucrose, and dehydrated at 4 °C for 48 h. All brains were embedded in OCT compound and stored at − 80 °C for sectioning.

Brains were coronally sectioned with the thick of 25 μm on a freezing microtome (Leica VT1200S, Wetzlar, Germany). The sections were then washed twice (15 min each) in PBS to remove the OCT, and blocked and permeabilized in PBS with 3% BSA and 0.3% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 for 20 min at room temperature. Thereafter, sections were directly transferred into primary antibody solution and incubated at 4 °C overnight.

Then the sections were washed twice (15 min each), and incubated in a mixture including the appropriate secondary antibodies (1:500) and Hoechst (1:2000) for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the sections were washed twice in PBS (15 min each) and mounted on slides (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with coverslips (Fisherbrand) and anti-fade solution (Applygen, Beijing, China). Images were captured under a confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Thy1-GFP mice were euthanized at 6–7 weeks, and were operated on following the above procedure to spines.

Primary Neuron Culture

Electroporated or unelectroporated E14.5 embryonic cortex was isolated and cut into small pieces, then treated with 0.25% trypsin for 6 min at 37 °C until most were dissociated into single cells. Neurons were suspended in medium containing Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s high-glucose medium and 20% (vol/vol) FBS, then plated on 35-mm glass dishes pre-coated with poly-D-lysine under 5% CO2/95% air at 37 °C. After 4 h, new complete medium composed of Neurobasal medium, B27 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and L-glutamine MAX was used to replace the old medium. Thereafter, half of the old culture medium was replaced by new medium every 48 h.

Stage Definition in Primary Neuron Culture

Differentiation stages in cortical neuron culture were defined by their polarization. Stage 1 neurons (E14.5+0 days in vitro (DIV)) had lamellipodia and filopodial protrusions; stage 2 neurons (E14.5+1-2 DIV) showed multiple immature neurite extensions; stage 3 neurons (E14.5+2-4 DIV) showed breaking of symmetry and specification; stage 4 neurons (E14.5+4-15 DIV) had axon and dendrite outgrowth and branching; and stage 5 neurons (E14.5+15-25 DIV) showed spine morphogenesis and synapse formation.

Calcium Phosphate Transfection of Primary Cortical Neurons

Calcium phosphate transfection was performed at DIV4 to reveal neuronal morphology. The culture medium was changed to fresh medium 2 h before transfection. Briefly, 4 μg plasmid DNA and 6 μL 2 mol/L CaCl2 were mixed with H2O to a total volume of 61 μL and added to an equal volume of 2 × Hanks Balanced Salt and then left for 20 min. The primary cortical neurons were treated with calcium phosphate-DNA suspension by gently shaking the dish. Transfected neurons were incubated under 5% CO2/95% air at 37 °C for 1 h, then the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium.

Immunofluorescence

To measure neurite growth at different stages, neurons were fixed with 4% PFA at 37 °C for 15 min at different days. After blocking in BSA, neurons were incubated in the primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight.

F-actin was stained by phalloidin on DIV4. Cultured neurons were washed with PBS, fixed in 4% PFA for 10 min, and washed with PBS at room temperature. After that, samples were treated with phalloidin solution (1:200 in PBS) for 40 min at 37 °C. Neurons were washed 3 times in PBS, then incubated with Hoechst (1:1000) for 15 min at room temperature. Finally, the neurons were washed 3 times in PBS (5 min each), then mounted for photography under a confocal laser scanning microscope (FV1000, Olympus).

Imaging

Images of sections and primary cortical neurons were captured on the confocal laser scanning microscope or an Olympus IX 71 microscope. Only the color balance, contrast, and brightness were optimized after imaging. EGFP+ cells within the cortex at different positions were counted for fluorescence quantification (mean ± SEM). Analyses for each condition were based on no less than 4 animals from 3 independent experiments.

Neurite Growth Analysis

We examined the morphology of primary cultured neurons at different early stages after P-Rex1 overexpression. We first calculated the percentages of transfected neurons at different stages on DIV3. Meanwhile, the lamellipodia protrusion area of stage 1 neurons, the number of neurites of stage 2 neurons, and the axon length and the number of other neurites of stage 3 neurons were analyzed. We evaluated stage 4 dendrites according to four criteria: number of branch points, length of the longest dendrite, total number of intersections, length of the longest dendrite, and total length of dendrites.

Sholl analysis was used to assess the neuronal dendritic branching patterns. The intersects between neurons and the circles were counted and plotted.

Morphological Analysis of Spines

The neurons in the virus injection site were chosen to investigate the influence of P-Rex1 overexpression on spine development in the mPFC of Thy1-GFP mice. For in vitro and in vivo morphological analysis, a spine was defined as mushroom-shaped/stubby protrusion with a distinct head or thin protrusion with a small head [40, 41]. Based on previous research [42, 43], at least three images were chosen from each animal to compute the average. Due to the high density of dendrites, it was difficult to identify cells individually, so we chose dendrites that were clearly visible to calculate the mean spine density by their total length; isolate spines were chosen to measure mean spine area [43]. The height was the distance between the top of a spine and the central line parallel to the direction of dendritic extension, and the width was the greatest diameter of a spine. Image-Pro Plus 6.0 was used for all measurements.

Virus Injection into the mPFC Region

P-Rex1 overexpression virus was injected into the mPFC on both sides in male C57BL/6 mice at P7 for behavioral tests at P42. Mice were anesthetized by pentobarbital sodium (4 μg/g body weight), fixed in a stereotactic apparatus, and a craniotomy performed. Microsyringes (5 μL; Hamilton Instruments, Cinnaminson, NJ, USA) were used to inject virus into the mPFC at 0.1 μL/min by an injection pump (RWD, Shenzhen, China). After injection, we left the needle for 10 min to ensure the virus was absorbed, then drew it out slowly. There were two injection sites (1 μL/site) in the left and right mPFC at AP − 2.3 mm, ML ± 0.35 mm, DV 2.2 mm from bregma.

Thy1-GFP transgenic male mice were used to observe the spines after virus injection. Mice were injected with Mock virus in the left mPFC and P-Rex1 overexpression virus in the right mPFC at P7. The injection sites were: left mPFC: AP − 2.3 mm, ML + 0.35 mm, DV 2.2 mm; right mPFC: AP − 2.3 mm, ML − 0.35 mm, DV 2.2 mm from bregma. The injection volume was 1 μL per site.

Behavioral Tests

Two groups of mice underwent the behavioral tests, each performing to the same sequence of tests. To minimize the influence of repeated test exposure, we arranged them from least to most invasive [44]. The order was: open field test, light-dark box, elevated plus maze, three-chamber social interaction, courtship UltraSonic Voices, repetitive behavior tests, and pre-pulse inhibition (PPI). When each experiment was completed, the mice were rested for 2 days. Mice were labeled on the tail to identify the test order in advance.

Open Field Test

The open field test was performed as previously described [45]. We set the central zone at 40% of total area of the box. The whole test lasted 60 min and the animals were allowed free movement. During the test, we put a mouse in the center of the chamber and used a video camera to record its movements. We analyzed the percentage of time spent in the central zone during the first 10 min, as well as the total movement distance.

Light-Dark Box Test

The light-dark box test was performed as previously described [45]. The chamber allowed animals to shuttle back and forth between the light and dark chambers. Mice were allowed to move freely for 5 min. A translocation occurred when all feet were in one chamber. We recorded the time spent in the light chamber.

Elevated Plus Maze Test

The elevated plus maze test was performed as described [39]. The whole test lasted 5 min. We placed a mouse on the central area (the overlap of the open and closed arms) and used the EthoVision 7.1 video-tracking system (Nodules) to record the time spent in the open arms.

Pre-pulse Inhibition

The PPI test was performed and the PPI ratio (% PPI) was calculated as previously described [45]. The day before testing, mice were placed in the box for 30 min to adapt to the environment. The baseline, the 110 dB startle pulse, and the pulse after the pre-pulse (70, 74, or 82 dB) were recorded. We analyzed the startle response amplitude and PPI.

Three-Chamber Social Interaction Test

The equipment and protocol were as described [39]. Male mice 6–7 weeks old with virus injected into the mPFC were used for the social interaction test. The total test included 3 trials of 5, 10, and 10 min. Stranger 1 and stranger 2 were also 6–7 week old male mice never seen by subject mice. During trial 1, the test mouse was placed in the center of the middle chamber and allowed to freely explore each chamber. During trial 2, stranger 1 was placed in a grid enclosure, and the sniffing time of stranger 1 and another empty grid enclosure were recorded. During trial 3, new stranger 2 was placed in the other grid enclosure and the sniffing times of stranger 1 and stranger 2 were recorded. The Ethovision 7.1 video-tracking system (Nodules, Leesburg, VA, USA) was used for all tests.

Courtship USV

First, the test mouse was alone in a new cage for 5 min, then a female mouse was put in for another 5 min. Audio was recorded by an Avisoft SASLab Pro Recorder. All parameters were set as follows: 300 kHz sampling frequency; 1,024-point fast Fourier transform length; format 16-bit.

Repetitive Behaviors

For the grooming and digging test, the test mouse was put into a new cage with new bedding and recorded for 20 min. We recorded the time mice spent in grooming and digging. For grooming behavior, we recorded the time when mice used two forelimbs to stroke or scratch the body, head, and face, or licked body parts. For digging behavior, we recorded when bedding materials were dig out or displaced by the fore or hind limbs.

For the hole-board test, mice were put in the center of a square board with 16 holes, and allowed to explore each hole freely. We counted the total time of exploration and the time of exploring to the same hole. We defined twice or more times in the same hole as repetitive behavior.

Western Blot

Western blotting was used to assess the P-Rex1 expression after virus injection into the mPFC. The injected area was isolated and dissolved in RIPA lysis buffer with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 1X protease inhibitor (Roche). P-Rex1 protein in the mPFC was blotted with anti-P-Rex1 (1:1,000) antibodies.

Statistical Analysis

During all testing and counting, the investigator was blind to the kind of virus injected. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. SPSS 20.0 (SPSS) was used for statistical analyses. We considered a difference significant at P < 0.05. Data with a normal distribution were analyzed by Student’s t test. Data without a normal distribution were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney test.

Results

P-Rex1 Overexpression Impedes Neuronal Migration by Inhibiting Multipolar-to-bipolar Transition

To explore whether P-Rex1 overexpression affects neuronal migration, we performed in utero electroporation at E14.5 with P-Rex1 overexpression and Mock plasmids expressing the GFP reporter gene to identify transfected cells. We analyzed the distribution of GFP+ cells at P0 and found that a majority neurons with Mock plasmids migrated to the upper cortical plate (CP). However, most neurons overexpressing P-Rex1 accumulated in the intermediate zone (IZ) and only a few neurons migrated to the upper CP (Fig. 1A, B). These results suggested that P-Rex1 overexpression inhibits cortical neuronal migration.

Fig. 1.

P-Rex1 overexpression inhibited the radial migration of cortical neurons by impairing neuron polarity. A Representative images of E14.5 mouse cortices electroporated with P-Rex1:OE and Mock plasmids at P0. Representative coronal sections at P0 stained with antibodies to GFP (green) and counterstained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bar, 50 μm. B Percentages of GFP cells in each region [379 cells from 9 embryos (Mock); 238 cells from 7 embryos (P-Rex1:OE)]. Data are represented as the mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Student’s t test. C, D Enlarged images of electroporated neurons after the overexpression of P-Rex1 that inhibited the formation of leading processes and changed neuronal polarity. Scale bars, 50 μm. E Representative images showing the morphology of neurons in layers II–III and V–VI of P2 cortex. Scale bar, 50 μm. F Representative images showing the Golgi apparatus localization of electroporated neurons in the IZ (arrows) (E14.5–E16.5). Scale bar, 50 μm. G Radially migrating cells defined as the percentage of cells with Golgi apparatus facing the cortical plate. Mock cells from 12 slices; P-Rex1:OE cells from 16 slices. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Pearson’s χ2 test. Data represented as the mean ± SEM. H Representative images showing the migration of cortical neurons electroporated with NeuroD:: IRES-EGFP and NeuroD: P-Rex1-IRES-EGFP (E14.5-P0). Scale bars, 50 μm. I Percentages of GFP+ cells in each region (E14.5-P0) [93 cells from 5 embryos (NeuroD::IRES-EGFP); 182 cells from 6 embryos (NeuroD::P-Rex1-IRES-EGFP)]. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Mann-Whitney test. Data represented as the mean ± SEM.

Furthermore, we observed the morphology of neurons residing in the IZ (Fig. 1C). Most of the neurons in the Mock group showed a radial distribution and normal polarity. In the Mock group, neurons showed bipolar morphology with a straight and thick leading process towards the cortical surface and a trailing process towards the ventricular zone. Neurons overexpressing P-Rex1 were multipolar, especially those retained in the IZ, having lost the normal leading process and the radial direction of migration (Fig. 1D). Besides, we observed the morphology of neurons in layers II–III and V–VI of P2 cortex, and found that neurons overexpressing P-Rex1 showed increased branches in the leading process with excessive lamellipodia (Fig. 1E).

During neuronal migration, neurons in the subventricular zone and IZ move randomly towards the CP. Meanwhile, the centrosomes and Golgi reorient in the same direction. In this study, we determined the direction of neuronal migration by staining the Golgi protein GRASP65 in the IZ of E16.5 embryonic brains that were electroporated at E14.5. Only neurons with Golgi apparatus located ahead of the nucleus and with an angle towards the pial surface of < 90° were defined as migrating radially (Fig. 1F). The percentages of cells with the Golgi facing the CP were significantly lower in the group overexpressing P-Rex1 than in the Mock group (Fig. 1G).

To exclude the effect of P-Rex1 overexpression on progenitor cell-division or the radial glial cytoskeleton during neuronal migration, we introduced P-Rex1 overexpression plasmid under the control of the NeuroD promoter to express this gene in postmitotic migratory neurons [46, 47]. We performed in utero electroporation with the plasmid NeuroD::P-Rex1-IRES-EGFP on E14.5 to overexpress P-Rex1 only in postmitotic neurons. The plasmid NeuroD::IRES-EGFP was used as control. Then we observed the position of GFP+ neurons (Fig. 1H) and analyzed the distribution of GFP+ neurons at P0 (Fig. 1I). The results showed that most control neurons were located in the upper IZ and CP, but the majority of neurons overexpressing P-Rex1 were found the in IZ, suggesting a cell-autonomous role of P-Rex1 overexpression in neuron migration.

Due to the abnormal development of radial glial cells, neuronal proliferation and apoptosis can impair neuronal migration. In this study, we stained the radial glial cells with Nestin (Fig. S1A), neuronal proliferation with BrdU (Fig. S1B and S1C), and apoptosis with TUNEL (Fig. S1D). We found no abnormalities, which further indicated that P-Rex1 overexpression inhibits the radial migration of cortical pyramidal neurons rather than radial glial cells, neuronal proliferation, or apoptosis.

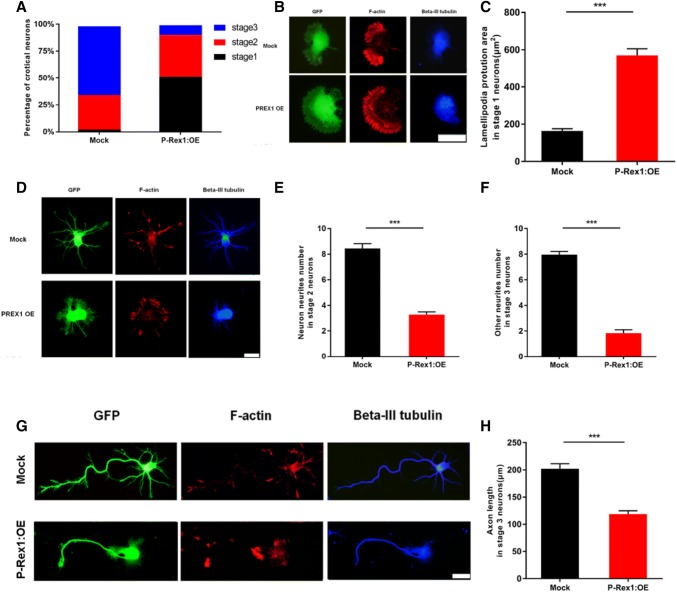

P-Rex1 Overexpression Results in Aberrant Neurite Initiation by Altering Cytoskeletal Dynamics In Vitro

We found that P-Rex1 overexpression inhibited the migration of cortical neurons by abnormal morphology and migration direction in vivo. To further identify the influence of P-Rex1 overexpression on the early neuronal development, we cultured electroporated cortical neurons at 0 days (DIV0) and DIV3. About 64% neurons in the Mock group were found to develop to stage 3 at DIV3; conversely, most neurons overexpressing P-Rex1 remained at stages 1 and 2 (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

P-Rex1 overexpression impeded neurite initiation through cytoskeletal change. A Percentages of primary cortical neurons at different developmental stages (DIV0-3) [846 Mock cells and 782 P-Rex1:OE cells from 3 independent experiments analyzed using two-way ANOVA. Interaction effect: F (2, 36) = 82.340, P < 0.001. Data represented as the mean ± SEM. B, C Stage 1 neurons, and lamellipodia protrusion area in stage 1 neurons [59 Mock cells and 49 P-Rex1:OE cells from 3 independent experiments]. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Student’s t test. Scale bar, 20 μm. Data presented as the mean ± SEM. D, E Stage 2 neurons, and numbers of primary neurites in these neurons. P-Rex1 overexpression regulated F-actin and influenced neurite initiation. Scale bar, 20 μm; 43 Mock cells and 52 P-Rex1:OE cells from 3 independent experiments; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Student’s t test. Data presented as the mean ± SEM). F–H Stage 3 neurons, and quantification of other neurites and axon length in these neurons (scale bar, 20 μm; DIV0-3; 130 Mock cells and 97 P-Rex1:OE cells from 3 independent experiments: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Mann-Whitney test. Data presented as the mean ± SEM).

During neurodevelopment, cytoarchitecture and dynamics changes are essential for neurite extension and polarization. Neuritogenesis depends on cytoskeletal adaptation, so we observed the cytoskeleton after Mock and P-Rex1 neuronal overexpression. We observed cytoskeletal changes of early-developing neurons at DIV3 (stages 1–3) (Fig. 2B, D, G) and found that neurons with P-Rex1 overexpression exhibited excessive F-actin assembly at the growth cone compared with Mock neurons, as well as reduced branches and length of βIII-tubulin.

Meanwhile, we measured the protrusion area of lamellipodia in stage1 neurons and found that the area in neurons overexpressing P-Rex1 was larger than in the Mock group (Fig. 2C). We also counted the number of primary neurites in stage 2 neurons, and the number of other neurites and axon length in stage 3 cortical neurons at DIV3; all of them were lower in neurons overexpressing P-Rex1 than the Mock group (Fig. 2E, F, H). These results suggested that P-Rex1 overexpression influences the early development of neurons by changing cytoskeletal dynamics.

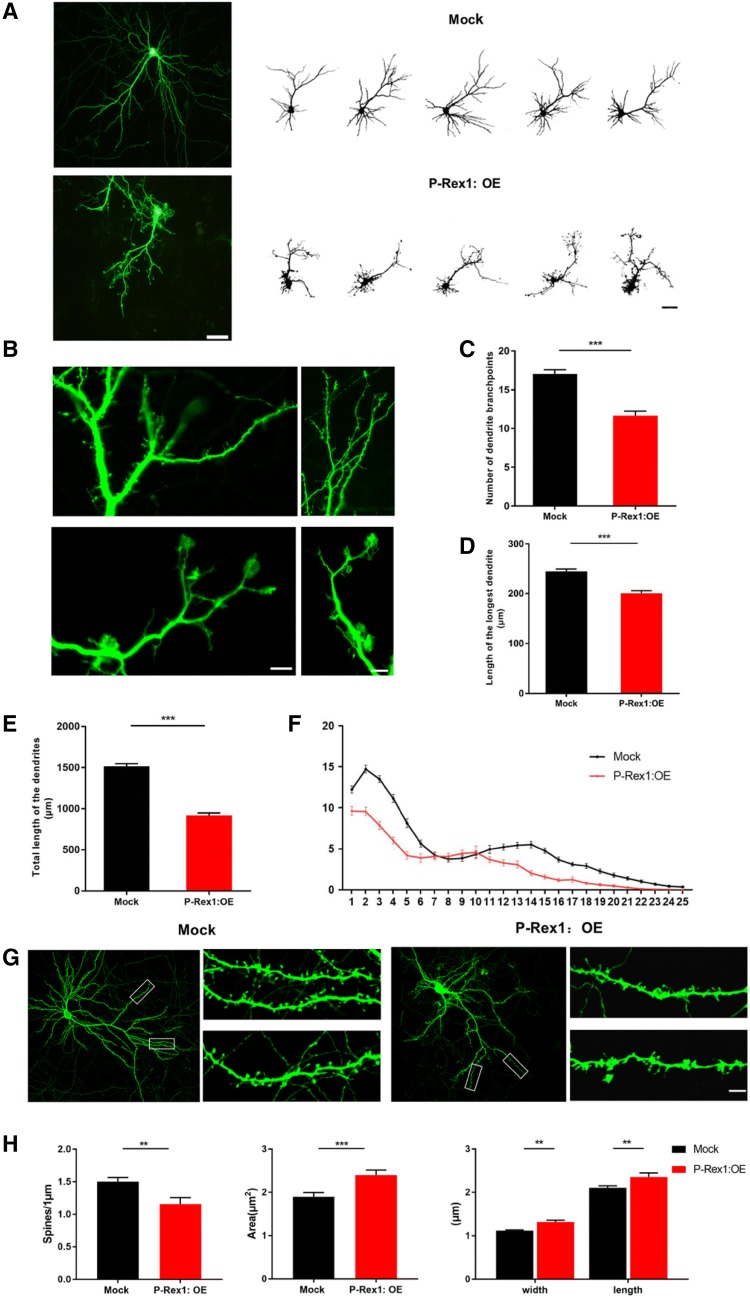

P-Rex1 Overexpression Results in Excess Lamellipodia and Influences Spine Morphology

To explore the effect of P-Rex1 overexpression on the later developmental stages of primary cortical neurons, neurons were transfected at DIV4 and collected at DIV10. We found that overexpression of P-Rex1 induced excess lamellipodia formation on both apical and basal dendrites (Fig. 3A). High-magnification images also showed marked lamellipodia formation in dendrites of cells overexpressing P-Rex1 (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

P-Rex1 overexpression led to excess lamellipodia and abnormal spines in vitro. A Representative images of cortical neurons transfected with Mock and P-Rex1 at DIV 4 for 10 days (OE plasmids by calcium phosphate transfection; scale bar, 50 μm). B High magnification images showing marked lamellipodia formation in the dendrites of rat primary cortical neurons overexpressing P-Rex1 (DIV4–10; scale bar, 10 μm). C–E Numbers of dendrite branch points, length of the longest dendrites, and total dendritic length (DIV4–10; Scale bars, 10 μm; 59 Mock cells and 50 P-Rex1:OE cells; OE cells from 3 independent experiments; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Student’s t test). Data presented as the mean ± SEM. F Sholl analysis showing numbers of dendritic intersections and total number of dendritic intersections (DIV4-10; cells from 3 independent experiments; main effect of group, F (1, 2676) = 357.411, P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA). Data presented as the mean ± SEM. G, H Dendritic spine morphology at DIV10–18 (scale bar, 5 μm; 216 Mock cells and 122 P-Rex1:OE cells from 3 independent experiments; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Student’s t test). Data presented as the mean ± SEM.

In addition, the group overexpressing P-Rex1 showed fewer dendrite branch points, fewer dendritic intersections, shortened length of the longest dendrites, and a shortened total dendritic length than the Mock group at DIV10 (Fig. 3C–E). Moreover, Sholl analysis showed that neurons overexpressing P-Rex1 exhibited reduced dendritic complexity (Fig. 3F). These results suggested that P-Rex1 overexpression induced excess lamellipodia formation to influence dendrite outgrowth and branching.

Besides, we analyzed the spines in cultured neurons by transfecting the P-Rex1 overexpression plasmid at DIV10. At DIV18, the neurons overexpressing P-Rex1 exhibited a decreased spine density with increased head area, height, and width (Fig. 3G, H).

Mice with P-Rex1 Overexpression in the mPFC Displayed Abnormal Dendritic Spine Morphology and Psychosis-Related Behaviors

To further investigate the influence of P-Rex1 overexpression on dendritic spine morphology in vivo, a viral vector for P-Rex1 overexpression was injected into Thy1-GFP transgenic mice. The injection site was checked in brain sections (Fig. 4A), and the expression of P-Rex1 after virus injection was verified using western blot (Fig. 4B). After analyzing the spine morphology in the mPFC, we found a decreased spine density with increased head area, height, and width (Fig. 4C, D), consistent with the presentation in vitro.

Fig. 4.

P-Rex1 overexpression in vivo caused abnormal spines and abnormal behaviors. A Virus overexpressing P-Rex1 injected into the mPFC (scale bar, 500 μm). B Western blot result of the virus injection site in the mPFC after the behavioral tests. C Morphology of dendritic spines in Mock and P-Rex1:OE group (scale bar, 5 μm). D Dendritic spine density, height, width, and head area were greater in the P-Rex1:OE group (135 mock cells and 114 P-Rex1:OE cells from 3 independent experiments; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, Student’s t test). Data presented as mean ± SEM. E The open field results did not different between the Mock and P-Rex1:OE groups (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, Student’s t test; Mock, n = 16, P-Rex1:OE, n = 19). Data presented as the mean ± SEM. F The time in open arms was significantly lower in the P-Rex1:OE group (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Student’s t test; Mock, n = 13, P-Rex1:OE, n = 15). Data presented as the mean ± SEM. G The time in the light box was lower in the P-Rex1:OE group (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Student’s t test; Mock, n = 17, P-Rex1:OE, n = 17). Data presented as the mean ± SEM. H Performance of P-Rex1:OE mice was abnormal in PPI. P-Rex1:OE mice showed a significant reduction in the ability to gate the startle response, as indicated by decreased pre-pulse inhibition at three kinds of startle (70, 74, and 82 dB) (main effect of group: F (1, 60) = 16.709, P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA; Mock, n = 12; P-Rex1, n = 10). Data presented as the mean ± SEM.

Next, we explored whether P-Rex1 overexpression influenced higher brain functions and psychosis-related behaviors in mice. Although the open field was not affected (Fig. 4E), we found a significant effect of P-Rex1 overexpression on the elevated plus maze (Fig. 4F) and light-dark box behavior (Fig. 4G), which suggested anxiety-like behavior. In addition, we found a significant effect of P-Rex1 overexpression on PPI (Fig. 4H), which further indicated that mice with P-Rex1 overexpression in the mPFC showed sensorimotor gating deficits. Besides, we found no significant difference in PFC-dependent spatial working memory (Y- maze; Fig. S2A), stereotyped behaviors (grooming, hole detection, and digging; Fig. S2B–D), social communication (ultrasonic voice test; Fig. S2E), and social interaction (Fig. S2F, G).

Discussion

Deficiency of P-Rex1 has been shown to impair cell motility and neuron migration, as well as synaptic plasticity and mouse behaviors [36, 37, 39]. Nevertheless, the role of P-Rex1 was not fully understood due to a lack of research on the effect of P-Rex1 overexpression on cortical development. In the present study, we found that P-Rex1 overexpression caused altered neuronal polarity, manifested as an increased percentage of multipolar cells and excessively branched leading processes of bipolar cells during radial migration. In addition, primary neuronal culture showed that P-Rex1 overexpression impeded the development of neurite initiation and dendritic spine formation by a cytoskeletal change. Furthermore, P-Rex1 overexpression in the mouse mPFC caused anxiety-like behaviors and sensorimotor gating deficits.

Insufficient P-Rex1 causes abnormal neuronal migration and polarization [36, 48, 49] as well as abnormal neurite morphology during cortical development [37]. In our study, we found that P-Rex1 overexpression showed similar phenotypes. Therefore, excessive or deficient of P-Rex1 might be prejudicial to neuronal development. P-Rex1 regulates the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton by the dynamic assembly or disassembly, as well as reorganization [50]. Meanwhile, it has been reported that P-Rex1, a sensitive activator of Rac1, regulates the cytoskeleton depending on Rac1 activation, while insufficient or superfluous Rac1 has adverse consequences for neurodevelopment [36, 51–53]. Studies have suggested that both deficient and excessive P-Rex1 cause a consistent change in the Rac1 activation level [33]. Consequently, our findings indicated that an appropriate level of P-Rex1 is required for normal development of the cerebral cortex, which might involve P-Rex1-related signaling pathways such as P-Rex1-Rac1 signaling.

It is generally believed that the lamellipodia can attach and pull the cell body to drive cell migration [54], and the actin network provides powerful protrusive force to command forward movement [55], especially the polymerization of actin filaments [56]. Meanwhile, lamellipodia play an important role in neurite initiation by transforming them into smaller structures to form growth cones [57]. A substantial body of research has shown that insufficient lamellipodia impair cell migration [58, 59] and the initiation of neurite protrusions [50, 60]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no reports on the effects of excess lamellipodia on neurodevelopment. In the present study, we found that excess lamellipodia had negative implications for cytoskeleton-mediated neuronal polarity including, migration, neuritogenesis. and dendritic spine formation. We demonstrated that excess lamellipodia impede neuronal development.

It has been shown that P-Rex1 is necessary for downstream Rac1 activation. P-Rex1-Rac1 signaling is critical for the regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics in the central nervous system [61]. However, since a similar impairment of Rac1 activation occurred with disruption of P-Rex1, our findings of excess lamellipodia during dendritic outgrowth and the enlarged spines caused by P-Rex1 overexpression were not so markedly represented in Rac1 overexpression [62]. These results suggested that, in addition to this signaling pathway, other signaling pathways might be involved, such as RhoG, which is directly activated by P-Rex1 to regulate Rac signaling and actin polarity [49]. In addition, the effect of P-Rex1 overexpression on mouse behavior had not yet been reported, and our study revealed that mice with P-Rex1 overexpression in the mPFC displayed anxiety-like behaviors, as well as impaired PPI. Further studies are required to investigate other molecules downstream of P-Rex1 and to establish the mechanisms underlying these psychosis-related behaviors.

In summary, our findings suggest that P-Rex1 overexpression results in deficits in neuron migration and neurodevelopment through altered neuron polarity, neurite initiation. and dendritic spine development. Our results highlight the vital role of P-Rex1 in the developing cerebral cortex, which might be related to psychosis-related behaviors.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Prof. Lin Xu for valuable help in suggesting the experimental design. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81730037, 81871077, and 81671363), the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Project (Z181100001518001), and the Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program By China Association for Science and Technology (YESS20160068).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Dai Zhang, Email: daizhang@bjmu.edu.cn.

Jun Li, Email: junli1985@bjmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Rakic P. Mode of cell migration to the superficial layers of fetal monkey neocortex. J Comp Neurol. 1972;145:61–83. doi: 10.1002/cne.901450105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rakic P, Stensas LJ, Sayre E, Sidman RL. Computer-aided three-dimensional reconstruction and quantitative analysis of cells from serial electron microscopic montages of foetal monkey brain. Nature. 1974;250:31–34. doi: 10.1038/250031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Craig AM, Banker G. Neuronal polarity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1994;17:267–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.001411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kon E, Cossard A, Jossin Y. Neuronal polarity in the embryonic mammalian cerebral cortex. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017;11:163. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nadarajah B, Alifragis P, Wong RO, Parnavelas JG. Neuronal migration in the developing cerebral cortex: observations based on real-time imaging. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13:607–611. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.6.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grigor MR, Bell IC., Jr Synthesis of fatty acid esters of short-chain alcohols by an acyltransferase in rat liver microsomes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973;306:26–30. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(73)90204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar RA, Pilz DT, Babatz TD, Cushion TD, Harvey K, Topf M, et al. TUBA1A mutations cause wide spectrum lissencephaly (smooth brain) and suggest that multiple neuronal migration pathways converge on alpha tubulins. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:2817–2827. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reiner O, Albrecht U, Gordon M, Chianese KA, Wong C, Gal-Gerber O, et al. Lissencephaly gene (LIS1) expression in the CNS suggests a role in neuronal migration. J Neurosci. 1995;15:3730–3738. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03730.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keays DA, Tian G, Poirier K, Huang GJ, Siebold C, Cleak J, et al. Mutations in alpha-tubulin cause abnormal neuronal migration in mice and lissencephaly in humans. Cell. 2007;128:45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qin R, Cao S, Lyu T, Qi C, Zhang W, Wang Y. CDYL deficiency disrupts neuronal migration and increases susceptibility to epilepsy. Cell Rep. 2017;18:380–390. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penagarikano O, Abrahams BS, Herman EI, Winden KD, Gdalyahu A, Dong H, et al. Absence of CNTNAP2 leads to epilepsy, neuronal migration abnormalities, and core autism-related deficits. Cell. 2011;147:235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones EG. Cortical development and neuropathology in schizophrenia. Ciba Found Symp. 1995;193:277–295. doi: 10.1002/9780470514795.ch14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nopoulos PC, Flaum M, Andreasen NC, Swayze VW. Gray matter heterotopias in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1995;61:11–14. doi: 10.1016/0925-4927(95)02573-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou D, Pang F, Liu S, Shen Y, Liu L, Fang Z, et al. Altered motor-striatal plasticity and cortical functioning in patients with schizophrenia. Neurosci Bull. 2017;33:307–311. doi: 10.1007/s12264-016-0079-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang R, Zhang HF, Han JS, Han SP. Genes related to oxytocin and arginine-vasopressin pathways: associations with autism spectrum disorders. Neurosci Bull. 2017;33:238–246. doi: 10.1007/s12264-017-0120-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu X, Qiu Z, Zhang D. Recent research progress in autism spectrum disorder. Neurosci Bull. 2017;33:125–129. doi: 10.1007/s12264-017-0117-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uhlhaas PJ, Haenschel C, Nikolic D, Singer W. The role of oscillations and synchrony in cortical networks and their putative relevance for the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:927–943. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schulte JT, Wierenga CJ, Bruining H. Chloride transporters and GABA polarity in developmental, neurological and psychiatric conditions. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;90:260–271. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simms ML, Kemper TL, Timbie CM, Bauman ML, Blatt GJ. The anterior cingulate cortex in autism: heterogeneity of qualitative and quantitative cytoarchitectonic features suggests possible subgroups. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118:673–684. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0568-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bailey A, Luthert P, Dean A, Harding B, Janota I, Montgomery M, et al. A clinicopathological study of autism. Brain. 1998;121(Pt 5):889–905. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.5.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santana J, Marzolo MP. The functions of Reelin in membrane trafficking and cytoskeletal dynamics: implications for neuronal migration, polarization and differentiation. Biochem J. 2017;474:3137–3165. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Devoto P, Flore G, Saba P, Scheggi S, Mulas G, Gambarana C, et al. Noradrenergic terminals are the primary source of alpha2-adrenoceptor mediated dopamine release in the medial prefrontal cortex. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;90:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iritani S, Torii Y, Habuchi C, Sekiguchi H, Fujishiro H, Yoshida M, et al. The neuropathological investigation of the brain in a monkey model of autism spectrum disorder with ABCA13 deletion. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2018;71:130–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adhikari A, Topiwala MA, Gordon JA. Single units in the medial prefrontal cortex with anxiety-related firing patterns are preferentially influenced by ventral hippocampal activity. Neuron. 2011;71:898–910. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chidambaram SB, Rathipriya AG, Bolla SR, Bhat A, Ray B, Mahalakshmi AM, et al. Dendritic spines: revisiting the physiological role. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;92:161–193. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hori K, Hoshino M. Neuronal migration and AUTS2 syndrome. Brain Sci. 2017;7:54. doi: 10.3390/brainsci7050054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang Q, Yang H, Wang M, Wei H, Hu F. Role of microtubule-associated protein in autism spectrum disorder. Neurosci Bull. 2018;34:1119–1126. doi: 10.1007/s12264-018-0246-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benitez-King G, Ramirez-Rodriguez G, Ortiz L, Meza I. The neuronal cytoskeleton as a potential therapeutical target in neurodegenerative diseases and schizophrenia. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2004;3:515–533. doi: 10.2174/1568007043336761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geraldo S, Gordon-Weeks PR. Cytoskeletal dynamics in growth-cone steering. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3595–3604. doi: 10.1242/jcs.042309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsuboi D, Kuroda K, Tanaka M, Namba T, Iizuka Y, Taya S, et al. Disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1 regulates transport of ITPR1 mRNA for synaptic plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:698–707. doi: 10.1038/nn.3984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trembley MA, Quijada P, Agullo-Pascual E, Tylock KM, Colpan M, Dirkx RA, Jr, et al. Mechanosensitive gene regulation by myocardin-related transcription factors is required for cardiomyocyte integrity in load-induced ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation. 2018;138:1864–1878. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heidemann SR, Joshi HC, Schechter A, Fletcher JR, Bothwell M. Synergistic effects of cyclic AMP and nerve growth factor on neurite outgrowth and microtubule stability of PC12 cells. J Cell Biol. 1985;100:916–927. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.3.916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall A, Lalli G. Rho and Ras GTPases in axon growth, guidance, and branching. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a001818. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindsay CR, Lawn S, Campbell AD, Faller WJ, Rambow F, Mort RL, et al. P-Rex1 is required for efficient melanoblast migration and melanoma metastasis. Nat Commun. 2011;2:555. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pantarelli C, Welch HCE. Rac-GTPases and Rac-GEFs in neutrophil adhesion, migration and recruitment. Eur J Clin Invest. 2018;48(Suppl 2):e12939. doi: 10.1111/eci.12939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoshizawa M, Kawauchi T, Sone M, Nishimura YV, Terao M, Chihama K, et al. Involvement of a Rac activator, P-Rex1, in neurotrophin-derived signaling and neuronal migration. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4406–4419. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4955-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waters JE, Astle MV, Ooms LM, Balamatsias D, Gurung R, Mitchell CA. P-Rex1 - a multidomain protein that regulates neurite differentiation. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:2892–2903. doi: 10.1242/jcs.030353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donald S, Humby T, Fyfe I, Segonds-Pichon A, Walker SA, Andrews SR, et al. P-Rex2 regulates Purkinje cell dendrite morphology and motor coordination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4483–4488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712324105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J, Chai A, Wang L, Ma Y, Wu Z, Yu H, et al. Synaptic P-Rex1 signaling regulates hippocampal long-term depression and autism-like social behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E6964–6972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512913112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holtmaat AJ, Trachtenberg JT, Wilbrecht L, Shepherd GM, Zhang X, Knott GW, et al. Transient and persistent dendritic spines in the neocortex in vivo. Neuron. 2005;45:279–291. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berry KP, Nedivi E. Spine Dynamics: Are they all the same? Neuron. 2017;96:43–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Radley JJ, Rocher AB, Rodriguez A, Ehlenberger DB, Dammann M, McEwen BS, et al. Repeated stress alters dendritic spine morphology in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2008;507:1141–1150. doi: 10.1002/cne.21588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hsia AY, Masliah E, McConlogue L, Yu GQ, Tatsuno G, Hu K, et al. Plaque-independent disruption of neural circuits in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:3228–3233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McIlwain KL, Merriweather MY, Yuva-Paylor LA, Paylor R. The use of behavioral test batteries: effects of training history. Physiol Behav. 2001;73:705–717. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00528-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Z, Zheng F, You Y, Ma Y, Lu T, Yue W, et al. Growth arrest specific gene 7 is associated with schizophrenia and regulates neuronal migration and morphogenesis. Mol Brain. 2016;9:54. doi: 10.1186/s13041-016-0238-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang HP, Liu M, El-Hodiri HM, Chu K, Jamrich M, Tsai MJ. Regulation of the pancreatic islet-specific gene BETA2 (neuroD) by neurogenin 3. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:3292–3307. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.9.3292-3307.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jossin Y, Cooper JA. Reelin, Rap1 and N-cadherin orient the migration of multipolar neurons in the developing neocortex. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:697–703. doi: 10.1038/nn.2816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Welch HC, Condliffe AM, Milne LJ, Ferguson GJ, Hill K, Webb LM, et al. P-Rex1 regulates neutrophil function. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1867–1873. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Damoulakis G, Gambardella L, Rossman KL, Lawson CD, Anderson KE, Fukui Y, et al. P-Rex1 directly activates RhoG to regulate GPCR-driven Rac signalling and actin polarity in neutrophils. J Cell Sci. 2014;127:2589–2600. doi: 10.1242/jcs.153049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flynn KC. The cytoskeleton and neurite initiation. Bioarchitecture. 2013;3:86–109. doi: 10.4161/bioa.26259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuhn TB, Brown MD, Wilcox CL, Raper JA, Bamburg JR. Myelin and collapsin-1 induce motor neuron growth cone collapse through different pathways: inhibition of collapse by opposing mutants of rac1. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1965–1975. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-01965.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dietz DM, Sun H, Lobo MK, Cahill ME, Chadwick B, Gao V, et al. Rac1 is essential in cocaine-induced structural plasticity of nucleus accumbens neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:891–896. doi: 10.1038/nn.3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hua ZL, Emiliani FE, Nathans J. Rac1 plays an essential role in axon growth and guidance and in neuronal survival in the central and peripheral nervous systems. Neural Dev. 2015;10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13064-015-0049-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamaguchi H, Condeelis J. Regulation of the actin cytoskeleton in cancer cell migration and invasion. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:642–652. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alblazi KM, Siar CH. Cellular protrusions–lamellipodia, filopodia, invadopodia and podosomes–and their roles in progression of orofacial tumours: current understanding. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:2187–2191. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.6.2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bryce NS, Clark ES, Leysath JL, Currie JD, Webb DJ, Weaver AM. Cortactin promotes cell motility by enhancing lamellipodial persistence. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1276–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dehmelt L, Smart FM, Ozer RS, Halpain S. The role of microtubule-associated protein 2c in the reorganization of microtubules and lamellipodia during neurite initiation. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9479–9490. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-29-09479.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bergert M, Chandradoss SD, Desai RA, Paluch E. Cell mechanics control rapid transitions between blebs and lamellipodia during migration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:14434–14439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207968109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dimchev G, Steffen A, Kage F, Dimchev V, Pernier J, Carlier MF, et al. Efficiency of lamellipodia protrusion is determined by the extent of cytosolic actin assembly. Mol Biol Cell. 2017;28:1311–1325. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E16-05-0334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lewis AK, Bridgman PC. Nerve growth cone lamellipodia contain two populations of actin filaments that differ in organization and polarity. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:1219–1243. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.5.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ridley AJ. Rho GTPases and actin dynamics in membrane protrusions and vesicle trafficking. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:522–529. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Luo L, Hensch TK, Ackerman L, Barbel S, Jan LY, Jan YN. Differential effects of the Rac GTPase on Purkinje cell axons and dendritic trunks and spines. Nature. 1996;379:837–840. doi: 10.1038/379837a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.