Abstract

Humans have a remarkable capacity to mentally project themselves far ahead in time. This ability, which entails the mental simulation of events, is thought to be fundamental to deliberative decision-making as it allows us to search through and evaluate possible choices. Many decisions that humans make are foraging decisions, where one must decide whether an available offer is worth taking, when compared to unknown future possibilities (i.e., the background). Using a translational decision-making paradigm designed to reveal decision-preferences in rats, we found that humans engaged in deliberation when making foraging decisions. A key feature of this task is that preferences (and thus, value) are revealed as a function of serial choices. Like rats, humans also took longer to respond when faced with difficult decisions near their preference boundary, which was associated with prefrontal and hippocampal activation, exemplifying cross-species parallels in deliberation. Furthermore, we found that voxels within visual cortices encoded neural representations of available possibilities, specifically following regret-inducing experiences, in which the subject previously rejected a good offer only to encounter a low-valued offer on the subsequent trial.

Keywords: deliberation, episodic simulation, foraging, regret, fMRI, neural decoding

Introduction

Humans have the remarkable ability to mentally travel in time (Suddendorf, 2013). This capacity for episodic simulation affords individuals the cognitive and behavioral flexibility to anticipate and evaluate potential outcomes when making decisions (Buckner & Carroll, 2007a; Gilbert & Wilson, 2007; Schacter, Addis, & Buckner, 2008). This flexibility is especially relevant to deliberative decision-making, which entails the mental simulation and evaluation of distinct, imagined future possibilities. Many choices that humans make are foraging decisions, and involve choosing whether to take an available offer or not (i.e., the foreground option) compared against unknown future outcomes (i.e., the background; Charnov, 1976; Stephens, 2008). Foraging decisions occur in a variety of real-world contexts, e.g., humans forage for food in harsh environments, such as arctic hunters (Smith, 1991), taxi cab drivers forage for passengers in a city (Camerer, 1997), humans decide what food to purchase (Riefer, Prior, Blair, Pavey, & Love, 2017), and drug users forage for heroin in a black market (Hoffer, Bobashev, & Morris, 2009). However, it remains unknown what roles (if any) deliberative decision-making plays in foraging behaviors.

Foraging decisions are often characterized by the prey-selection model in which one makes sequential accept/refuse choices (Stephens, 2008; Wikenheiser, Stephens, & Redish, 2013). Limited resources impose trial interdependence across a session, where maximizing gains depends on comparing current offers against expected but unknown future options, and resources spent on one offer are not available for future offers. Many such experimental tasks include a time constraint, asking subjects to maximize gains within a specific time window, where time (or another limited resource) spent on one option is then unavailable for future options.

A fixed economy can reveal a subject’s preferences by measuring their willingness to endure the cost to attain some but not all rewards. For instance, during the neuroeconomic Restaurant Row task (Steiner & Redish, 2014), rats had a limited time to cycle between four feeders and collect different flavored food pellets available after variable delays. Rats revealed their preferences (or thresholds) by being willing to wait for different delays for each flavor; in turn, good offers were those with delays below threshold and bad offers were those above threshold. A key aspect of the Restaurant Row task is that the flavor order was held constant, while the delays were random, i.e., rats knew the location of the flavors but not the specific delays it would encounter on arrival. Thus, to accept the current cherry offer meant that the rat would have less time available to spend at the chocolate restaurant that would come up next. Critically, the sequential task design separates out past (the offer just left), current (the offer available to the rat), and future (the next offer that will be available); neural signatures could then be tracked in a circular format to indicate whether a rat was contemplating the current versus alternative offers. This sequential structure led to novel discoveries regarding deliberation and regret in rats; i.e., scenarios in which a rat turned down a good offer on the previous trial only to encounter an unfavorable offer on the subsequent trial.

Human neuroimaging and non-human neurophysiology findings inform our investigation of the neural circuits that underlie human episodic simulation during deliberation. Higher-level visual cortices may support the representation (and distinguishing) of complex visual stimuli (Haxby et al., 2011; Norman, Polyn, Detre, & Haxby, 2006), including regions like the lateral occipital cortex and fusiform gyrus (Grill-Spector & Weiner, 2014). Sensory cortices may also play a role. For instance, Doll et al. found that binary decisions that depend on planning activate the sensory cortical representations of those outcomes (Doll, Duncan, Simon, Shohamy, & Daw, 2015); this finding is consistent with evidence that overlapping neural systems are involved in past recall and future simulation (Hassabis & Maguire, 2007; Schacter & Addis, 2007b; Schacter et al., 2012), and when imagining and perceiving a stimulus (Pearson, Naselaris, Holmes, & Kosslyn, 2015). Additionally, human fMRI studies and neural recordings from rodents implicate the hippocampus and parahippocampus in deliberation (Buckner & Carroll, 2007a; Hassabis, Kumaran, Vann, & Maguire, 2007; Redish, 2016). The hippocampus supports the formation of internal cognitive maps and the evaluation of potential options (Kaplan, Schuck, & Doeller, 2017; Wang, Cohen, & Voss, 2015): individuals may use cognitive maps during deliberation to extract key information from prior experiences, to guide future choices, and to more efficiently encode new experiences.

In non-human animals deliberation is intimately tied to the difficulty of a choice. Rats faced with difficult choices, just above the decision threshold, spend more time deliberating over those choices (Steiner and Redish, 2014; Sweis et al., 2018), and exhibit a behavioral process termed “vicarious trial and error” (VTE; Tolman, 1939). Similarly, humans making difficult choices show lengthened reaction times (Shenhav, Straccia, Cohen, & Botvinick, 2014). Because VTE is implicated during uncertainty and in difficult decisions, it is thought to capture the indecision that underlies deliberation (Redish, 2016). During VTE, hippocampal place cells show forward-sweeping representations that alternate between options, suggesting the rat is mentally simulating possible outcomes (A. Johnson & Redish, 2007). These forward sweeps are evident during challenging choices requiring more deliberation, and fade out as decision behaviors become more automated (Johnson & Redish, 2007; Smith & Graybiel, 2013; van der Meer, Johnson, Schmitzer-Torbert, & Redish, 2010). The hippocampus may serve an analogous role in humans, although this theory has not been tested directly.

In the current study we employed a human version of the Restaurant Row task, called the “Web-Surf Task” (Figure 1) (Abram, Breton, Schmidt, Redish, & MacDonald, 2016). Humans had a fixed amount of time to forage for videos across four serially-presented “galleries” (i.e., video categories: kittens, dance, landscapes, and bike accident videos). Based on previous data that animals, tools, bodies, and scenes are represented differently within cortical circuits (Haxby et al., 2011, 2001; Reddy, Tsuchiya, & Serre, 2010; Tong & Pratte, 2012), we first hypothesized that we could differentiate representations of the four categories with fMRI. After confirming that humans made internally-consistent foraging decisions and that neural representations of categories were dissociable, we tested for evidence of episodic simulation during deliberation. We hypothesized that in foraging decisions, deliberation should be more about the upcoming offer (i.e., foreground option) than the alternatives (i.e., background), and that deliberation would be supported in visual cortices known to represent complex visual stimuli. Additionally, we anticipated that hippocampal regions would be involved in making difficult choices (requiring more deliberation).

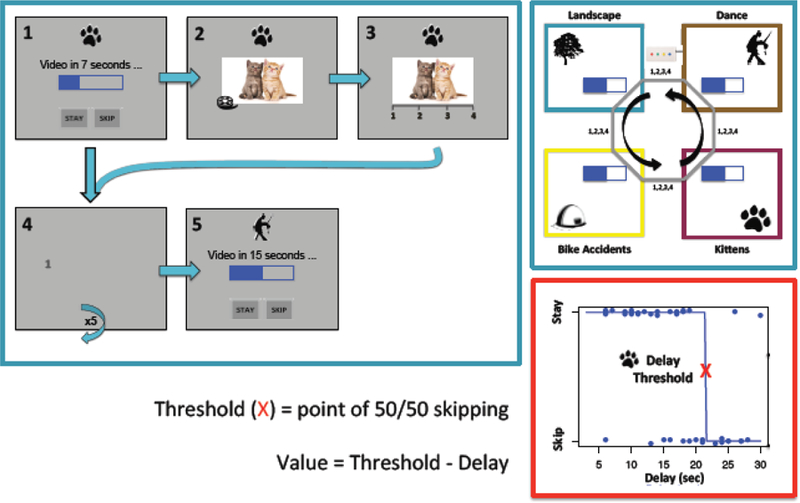

Figure 1.

MRI Web-Surf Task Layout and Flow-diagram

Flow diagram illustrates differences between a stay and skip trial (left). If the subject stays (1), they wait through the delay, view the 4-sec video clip (2), and rate the video (3). If they instead choose to skip, they proceed through the cost phase (4), and arrive at the next offer (5). Schematic of Web-Surf Task. Subjects had 35 minutes to cycle between the four video galleries in the depicted order (upper right). Example of delay threshold computation for a single subject (bottom right).

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Twenty-nine healthy volunteers were recruited for the current study. Twenty-five subjects were retained for analysis (52% male, age range = 20 to 39 years old, mean age = 28 years, all right-handed), after excluding one subject for excessive head motion (i.e., mean movement greater than 3 mm, or 1.5 times the voxel size), one for claustrophobia, and two for invalid behavioral data. Subjects were recruited via Craigslist (an American classified advertisements website) and reported no prior history of neurological disease or severe mental illness and no first-degree relatives with a severe mental illness. Subjects completed a urine drug screen prior to participation and only those with a negative screening continued. All subjects provided written informed consent and the study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Minnesota.

Web-Surf Task Layout

Subjects had 35 minutes to cycle between four video categories (i.e., kittens, dance, landscapes, bike accidents) presented using PsychoPy (Peirce, 2009). Categories were indicated by the symbol at the top of the screen (Figure 1), and appeared in a fixed order. On arrival at a category, subjects were presented with a “download bar” (the offer) that indicated how long they would have to wait (delays ranged 3–30 seconds) for a given reward (i.e., 4-second video clip). If they elected to stay, the delay counted down, the subject watched the video clip, and then rated it on a 1–4 scale. If the subject chose to skip, they proceeded to the next category and received a new offer. The period between the start of a trial (i.e., arrival at a category) and the subject’s stay/skip choice was defined as decision, and the period between the start of a video and the subject’s rating was defined as consumption. When traveling between categories, subjects had to click the numbers 1–4 as they randomly appeared around the screen; this represented a travel cost. Numbers were presented in dark grey against a grey screen to increase the difficulty. Trials were presented in 9 minute blocks, with 45 seconds of a fixation cross-hair shown in between blocks. All subjects completed both in- and outside of scanner practice.

Web-Surf Preview Task

Before the main task, subjects completed a Preview Task that presented a fixed set of ten 4-second video clips from each category; categories appeared in the same order as the main task, and the video clips were randomly ordered within each category. Subjects rated each video using the same scale as the main task. A fixation cross-hair appeared between videos for 3–6 seconds (durations were randomized). Total task time was approximately 7 minutes. This task provided baseline estimates of preference and neural activation for each category, in the chance that a subject skipped all offers from a particular category during the main task.

fMRI Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Neuroimaging data were collected using a 3-Tesla Siemens MAGNETOM Prisma with a 32-channel head coil at the University of Minnesota’s Center for Magnetic Resonance Imaging. A high-resolution T1-weighted (MPRAGE) scan was collected for registration [repetition time (TR) = 2.5 ms; echo time (TE) = 3.65 ms; flip = 7°; voxel = 1 × 1 × 1 mm]. The main task was collected using a single whole-brain echo planar imaging (EPI) run, with the following sequence parameters: TR = 720 ms, TE = 37 ms, flip angle = 52°, voxel size = 2 × 2 × 2 mm (approximately 3500 volumes), multiband factor = 8; these same parameters were used for the preview task EPI sequence (approximately 500 volumes) and an additional short reverse phase-encoded EPI sequence used for distortion correction (10 volumes). The entire scanning session lasted one hour. The order of acquisitions was as follows: three-axis localizer scan, AA Scout [aligned slices to the anterior commissure – posterior commissure (AC-PC) line], T-1 MPRAGE, reverse phase-encoded EPI sequence, Preview Task, and then the Web-Surf Task; there was no set spacing between scans.

We carried out standard preprocessing using the FMRIB Software Library (FSL version 5.0.8; Jenkinson, Beckmann, Behrens, Woolrich, & Smith, 2012), which included brain extraction, motion correction1, prewhitening, high-pass temporal filtering with sigma of 50s, spatial smoothing with a 6 mm FWHM Gaussian kernel, and spatial normalization and linear registration to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) 152 standard brain. We also employed FSL’s topup functionality to correct susceptibility induced distortions. This entailed collecting a reverse phase-encoded EPI sequence with distortions going in the opposite direction, which was paired with both the main task and Preview Task. The susceptibility-induced off-resonance field was estimated from these pairs using a method similar to that described in (Andersson, Skare, & Ashburner, 2003). The images were then combined into a single corrected one.

Value Computations

Value was computed as the category-specific threshold minus delay, where thresholds indicated the delay time at which a subject reliably began to skip offers for a particular category. Delay thresholds were computed separately for each trial, per category, using a leave-one-out approach: to obtain the threshold for trial i, we fit a Heaviside step function to all trials in category c excluding trial i. This produced a vector of thresholds with length equal to the number of trials in category c, and we used the average of that vector in subsequent analyses. We used a Heaviside step function as an alternative to the logistic fit function described in (Abram et al., 2016), as the Heaviside step function can better handle extreme cases (i.e., when a subject stays or skips all offers in a category). In such instances, the Heaviside step function produces a reasonable value (e.g., 3 or 30), reflecting the range of possible delays, whereas the logistic fit function is likely to produce a value approaching infinity. Values then ranged from approximately −27 to 27 (e.g., 30 second delay with a threshold of 3 seconds versus a 3 second delay with a threshold of 30 seconds), and a value of 0 meant that the offer was equal to the threshold.

Behavioral Validity Analyses

We first asked whether humans made internally-consistent foraging decisions, by correlating subject-derived delay thresholds with measures of reward liking (i.e., average category ratings, post-test category rankings). These methods are the same as those previously described (Abram et al., 2016).

Learning Analyses

We next investigated cross-session learning effects, given that subjects skipped more as the session progressed, potentially due to satiation.2 We were specifically interested in whether we could detect behavioral changes as subjects became more familiar with the task (i.e., a switch from more deliberative to less deliberative decision processes). To this end, we compared decision reaction times against trial number, and then conducted follow-up analyses to understand how learning impacted relations between reaction times and value. We performed these same analyses using video rating reaction times, to assess whether cross-session shifts were similar for the decision and consumption phases. We also examined the extent to which video ratings fluctuated across the session, with consideration of subject-specific preferences.

Preview Task General Linear Model Analyses

Functional data from the Preview Task was first analyzed at the group-level using a whole-brain voxelwise general linear model (GLM) approach to assess for category-relevant activation. Here we used the fMRI Expert Analysis Tool (FEAT) within FSL. We modeled the video viewing and rating for each category as separate events (yielding four regressors of interest), as well as the six standard motion parameters as confound regressors. The events were convolved using a double-gamma hemodynamic response function (HRF), and a threshold of z > 3.1 and a whole-brain, corrected cluster-extent threshold of p < 0.01 was applied.

Decoding Validity Analyses

We used a multi-voxel pattern analysis decoding method, which offers a unique approach for probing episodic memory in humans, and is useful for identifying category-specific representations. In particular, we employed the Sparse Multinomial Logistic Regression (SMLR) (Krishnapuram, Carin, Figueiredo, & Hartemink, 2005) classifier available in the PyMVPA machine-learning package (Multivariate Pattern Analysis in Python, http://www.pymvpa.org) (Hanke et al., 2009). We selected this classifier given its computational efficiency and good classification performance (Krishnapuram et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2009). The SMLR classifier utilizes multiple regression to predict the logarithm of the odds ratio of belonging to a particular class. This ratio is then transformed into a probability via a nonlinear transfer function that ensures all classification probabilities sum to one. The sparsification component promotes a more parsimonious and generalizable solution. For the present analyses we used the default lambda penalty setting (λ = 1).

Decoding was conducted on a subject-by-subject basis and included the previously pre-processed fMRI data. We trained the classifier on the Preview Task data for all decoding analyses, because: (1) each subject saw the same set of videos during the Preview Task,3 (2) the Preview Task contained trials from every category (whereas subjects could elect to skip all videos from a category during the main task), and (3) this provided a separate training set so we did not have to create a cross-validation set from the main task data.

In step (1), we determined whether stimuli from the four categories were distinguishable via SMLR decoding using only the Preview Task data, as the subsequent analyses hinged on successful category separation. The first step in this process entailed fitting a GLM to the Preview Task data to obtain linear model activity estimate images (i.e., parameter estimates), which were then supplied as examples to the classifier. Each video category was modeled as a separate event, and we also included a regressor to account for the fixation periods between the videos; this event was considered the other category and provided a control from which to compare the four video categories. For this analysis, samples were ‘chunked’ to create groups of samples for cross-validation, each of which included two video samples from each category, as well as the fixation periods between those samples; the scan duration of a chunk ranged from approximately 60 to 80 seconds depending on the fixation lengths between videos. All trials in a given loop (or complete pass through all four categories) were included in the same chunk, as well as four trials from a different loop. We averaged two samples per category when forming chunks, as this approach produces less noisy examples (Pereira, Mitchell, & Botvinick, 2009). After fitting the model, we z-scored the data separately for each chunk.4 We performed 60/40 cross-validation, i.e., left two chunks out, on the Preview Task parameter estimate maps.5

In step (2), we tested whether we could predict which video a subject had viewed during the main task after training the classifier on the Preview Task data. We again fit a GLM to acquire a parameter estimate map for the video consumption time; we scaled the resulting parameter estimates to the training data, as the training data included an equal number of data points per condition. We then predicted which category the consumption time best represented (i.e., kittens, dance, landscape, bike accidents, or non-video), and extracted the corresponding probability estimates (one per category). The final step entailed combining the subject-specific data and re-organizing the probabilities according to the subjects’ location within the loop of video categories. Given that categories were presented in a fixed cycle (e.g., kittens, dance, landscapes, bike accidents, then back to kittens), we could organize the decoding results using previous, current, next, opposite, or non-video labels to indicate a subject’s location within that cycle and track past, current, or future representations as the subject traversed the task. As an example, for a subject at the kitten category, the obtained probabilities were labeled as follows: bike accidents (previous), kittens (current), dance (next), and landscapes (opposite). For a subject at the dance category, the obtained probabilities were labeled as follows: kittens (previous), dance (current), landscapes (next), bike accidents (opposite), or non-video (for when the data did not correspond with any of the video categories neural signatures).

We computed mixed-effects logistic models to compare probabilities between the locations using the lme4 package in R (Bates, Maechler Martin, & Walker, 2016). Specifically, we regressed the SMLR probabilities on location, with subject as a random effect. In the main text we report F-statistics to indicate whether there were overall probability differences between the locations. For significant overall models, we used two-tailed chi-square tests to determine which locations had probabilities above chance, i.e., 1/5 = 0.20 (4 video categories and 1 control category). Finally, for locations with probabilities above chance, we used follow-up one-tailed chi-square tests to determine whether that location’s probabilities were greater than the additional locations (e.g., for a model with only the current category attaining probabilities above chance the contrasts would be current > previous, current > next, and current > opposite, current > non-video); we report original p-values as well as false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted p-values using Benjamini and Hochberg’s FDR control algorithm (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995) for follow-up between-location comparisons.

Decoding Deliberation Analyses

Our primary aim was to test for evidence of deliberation during decision-making. We employed a comparable approach to that described under step (2), but instead fit GLMs to the decision phase of the main task data when acquiring the activation maps for the classifier (again scaling these maps to the training data).

We used mixed-effects logistic models and chi-square tests (as described above) to first identify which location(s) (i.e., previous, current, next, opposite, or non-video) were best represented across all the trials, and then by different decision conditions (e.g., stay versus skip choices). In follow-up analyses, we capitalized on the sequential task structure by evaluating relations between serial actions and deliberation, based on foundational work by Steiner and Redish (2014) using the rodent Restaurant Row task. To this end, we used mixed-effects logistic models to compare decision decoding probabilities and decision response times across four conditions: skip previous + skip current, stay previous + skip current, skip previous + stay current, stay previous + stay current; importantly, we considered the value (i.e., threshold – delay) of the past offer, as the decision to reject a good versus bad offer should yield differential effects (Steiner & Redish, 2014; Sweis, Redish, & Thomas, 2018; Sweis, Thomas, et al., in 2018).

Choice Difficulty General Linear Model Analyses

Lastly, we compared the above decoding results with a traditional GLM approach that pinpointed activation related to difficult choices. This model included four regressors (choice, delay, video viewing/rating, and travel), plus motion parameters. We weighted each decision and video-viewing event by its distance from the respective category threshold, such that events closer to threshold were weighted more heavily. Decisions in this model were isolated to the last second of the choice phase (given that reaction times differed systematically by value). Events were convolved using a double-gamma HRF and evaluated with a threshold of z > 3.1 and corrected cluster-extent threshold of p < 0.01.

Results

Choices Predict Reward Likability

Initial behavioral analyses revealed that people typically made choices consistent with offer value, i.e., threshold minus delay, where thresholds represented the point at which a subject reliably began to skip offers from a particular video category (see Figure S1 for plots of each subject’s thresholds). Foraging decisions conformed to a sigmoid pattern, where subjects typically accepted offers above threshold (offers valued greater than 0), and declined those below threshold (Figure S2A). This suggests our threshold metric was a good indicator of value-based decisions. To test the correspondence between subjects’ decisions and their liking of rewards, we correlated the four category thresholds with average category ratings and post-test category rankings separately. We found that 76% of the average rating correlations were above 0.5 and 88% of the post-test ranking correlations were above 0.5 (Figure S2B); these values are comparable to those previously reported (Abram et al., 2016). We also note that on average, subjects rated all categories between 2 and 3 (Figure S3), indicating that subjects generally found the video stimuli rewarding.

Cross-Session Characteristics

We observed a strong downward trend in decision reaction times as the session progressed (β = −0.002, p < 0.001; Figure 2A). In the first half of the session, reaction times were consistently slow for low valued trials, versus having a more peaked formation around threshold in the second half; further, reaction times were lower overall in the second half (paired-t = 11.92, p < 0.001). These patterns could reflect the process of adjusting one’s threshold, with subjects showing a much clearer understanding of their thresholds later in the session.

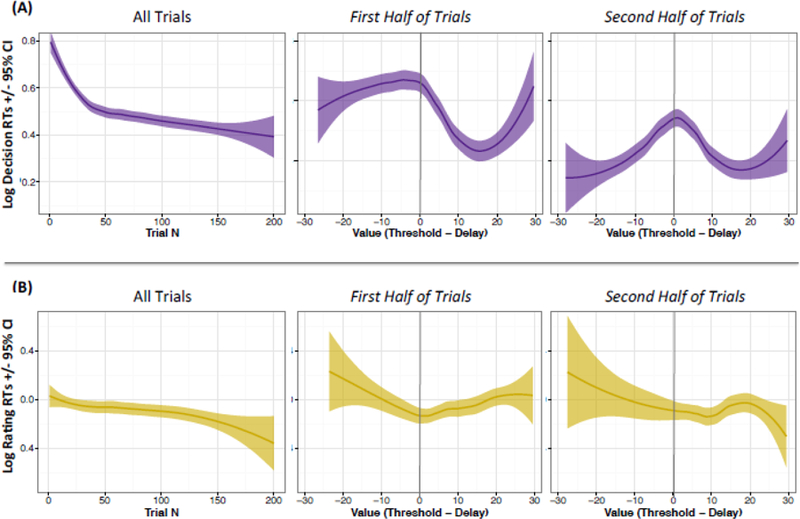

Figure 2.

Cross-session Behavioral Shift

(A) Decision reaction times show the steepest decline in the first 50 trials (left); Decision reaction times are consistently slow for low valued trials in the first half of the session (middle), versus a sharp peak at threshold for the second half (right). (B) Video rating reaction times do not significantly decline across the session (left); video rating reaction times are less driven by value (middle and right). Threshold indicated by vertical line at 0; shaded bands represent 95% confidence intervals.

We also point out that the increased reaction time is analogous to the VTE pattern observed in rats and mice during Restaurant Row (Steiner and Redish, 2014; Sweis et al., 2018): subjects took longer to make choices for offers that approached threshold, and were fastest for those significantly above or below threshold (Figure 2A). Consistent with the rodent data, reaction time remained high for lower-value offers (above threshold) more than for higher value offers (below threshold) during the first half of the session; this suggests that offers just above threshold (i.e., small negative values) were especially challenging and required more thoughtfulness.

In comparison to decision reaction times, rating reaction times did not significantly decline as a function of trial number (β = 0.000, p = 0.15; Figure 2B). Rating reaction times were also less impacted by offer value, suggesting that learning is more relevant to decision-making and not post-consumption evaluation.

Subjects also showed a slight decline in ratings across the session (β = −0.002, p < 0.001; Figure S4), with relatively similar declines across the four categories; however, when considering rating shifts by preference, we see that the top two preferred categories showed a sharper drop off in the second half of the session than the lesser preferred categories.

Distinguishability of Video Categories

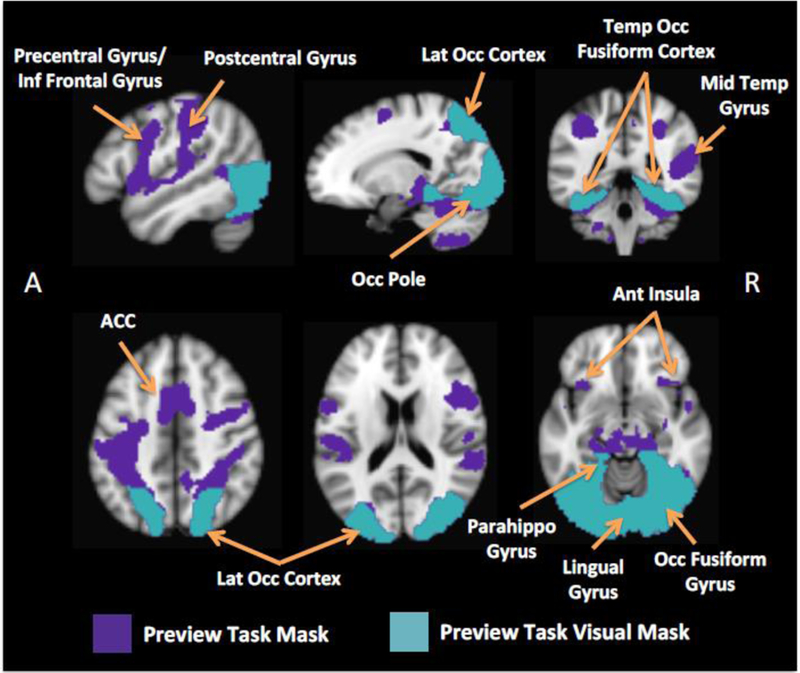

To test for deliberation, it was critical that we could discriminate the four video categories based on their neural signatures. An initial evaluation of the Preview Task data showed similar activation patterns across the video categories (Figure S5; Table S1; regions included the anterior insula, pre/postcentral cortex, hippocampus/parahippocampal gyrus, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), lateral occipital cortex, lingual gyrus, and inferior frontal gyrus). Further, comparing signal changes across the categories using an ANOVA revealed only trend-level differences (F3,96 = 2.73, p = 0.05).6 Given the large overlap in activation across the categories during the Preview Task, we created a cumulative mask for decoding that entailed merging the four main effect maps, i.e., the Preview Task mask (Figure 3). However, because the Preview Task mask extended beyond the visual cortex (into more anterior substrates), we compared its decoding performance to a second mask, i.e., the Preview Task Visual mask, which we restricted to higher-level visual regions known to represent complex visual stimuli (Haxby et al., 2011).

Figure 3.

Decoding Masks

Abbreviations: Inf = inferior; Lat = lateral; 0cc = occipital; Temp = temporal; Mid = middle; Ant = anterior; ACC = anterior cingulate cortex cortex; Parahippo = parahippocampal. Illustrations of the two masks used for the decoding analyses. The Preview Task Visual Mask is a restriction of the Preview Task Mask that includes only visual areas.

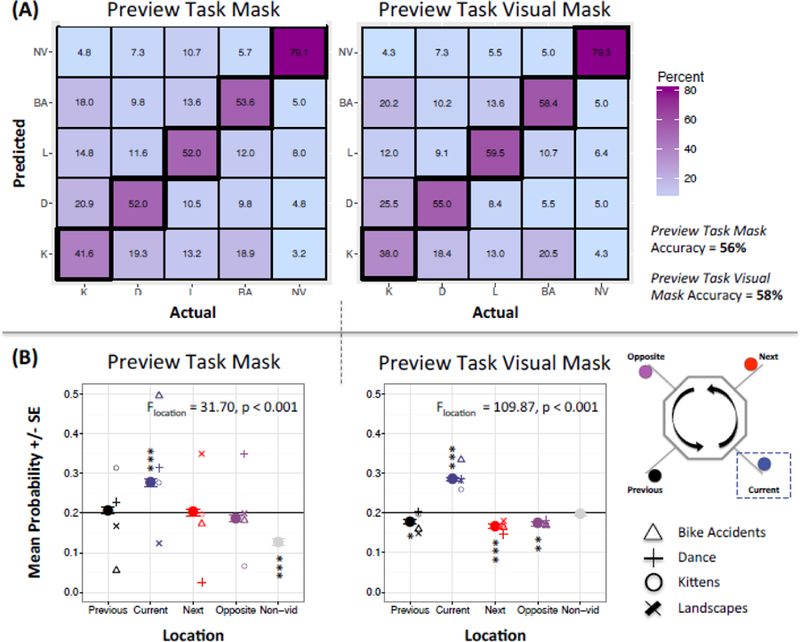

Initial validity analyses showed that the visually-restricted mask outperformed the broader Preview Task mask for dissociating categories (Figure 4). First, the Preview Task Visual mask had better accuracy overall when decoding the Preview Task data (4A), with approximately 53% accuracy for predicting each video category, roughly 80% accuracy for classifying the fixation periods between videos (i.e., the control condition), and an overall accuracy of 58% (compared to a chance level of 20%). Thus, stimuli were distinguishable via decoding despite their spatially similar activation maps.7

Figure 4.

Validity of Decoding Method

Abbreviations: K = kittens; D = dance; L = landscapes; BA = bike accidents; NV and Non-vid= non-video. (A) The four video categories were dissociable using decoding methods for both the Preview Task and Preview Task Visual masks. Predictions were based on training with 60% of the sample and testing on 40% of the sample over 10 iterations. Probabilities based on four video and one control (non-video) category, yielding a chance level of 20%. (B) Decoding using the Preview Task and Preview Task Visual masks represents the current category during video consumption. Chance indicated by horizontal black line at 0.2. Error bars reflect within-subject standard errors; asterisks reflect locations with probabilities significantly different than chance (5 follow-up χ2-tests performed per each significant model, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001).

Decoding of the main task consumption phase (i.e. while video viewing) was also used as a positive control, given that both the training and test data also entailed video viewing. Figure 4B shows that decoding of consumption-related activation using the Preview Task mask indicated a significant difference between locations (F4,7954 = 31.70, p < 0.001), with the best representation of the current location (i.e., location with probability above chance; mean current_PreviewTask = 0.277, SE current_PreviewTask = 0.009; χ2 = 58.19, p < 0.001; Table S2), and the non-video location falling below chance. In comparison, we observed significantly better decoding8 using the Preview Task Visual mask (F4,7954 = 109.87, p < 0.001; mean current_PreviewTaskVisual = 0.285, SE current_PreviewTaskVisual = 0.005; χ2 = 71.31, p < 0.001; Table S2); we note that both models reported in Table S2 include 4 pairwise comparisons (i.e., current versus the other four categories).

Based on the stronger performance of the Preview Task Visual mask for decoding both the Preview Task and main task consumption data, all remaining analyses focused solely on this mask.

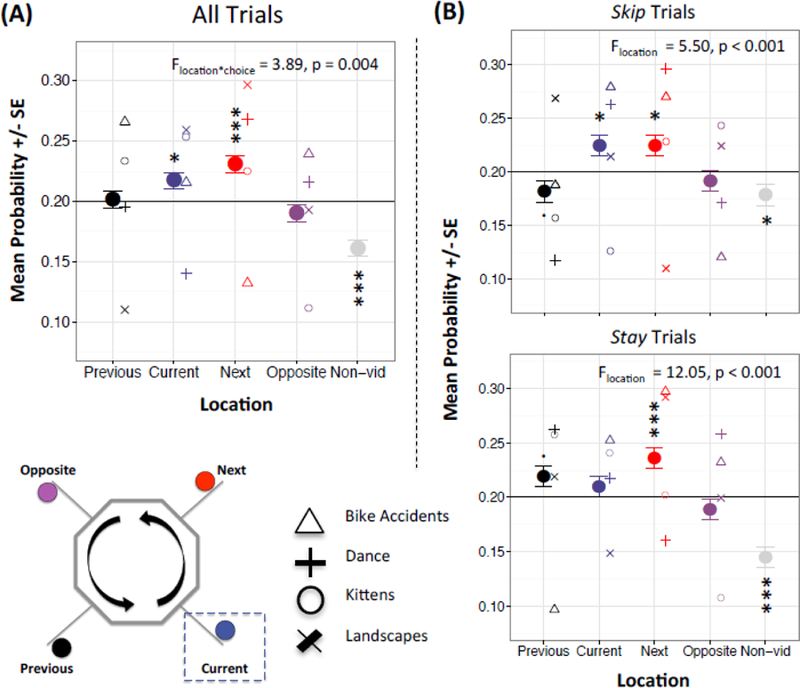

Visual Cortices Track Upcoming and Future Locations During Foraging Decisions

Decoding using the Preview Task Visual mask revealed the strongest representation of the next (F4,15259 = 14.51, p < 0.001; Figure 5A; Table S3; mean next_PreviewTaskVisual = 0.23, SE next_PreviewTaskVisual = 0.007; χ2 = 17.67, p < 0.001) followed by the current location (mean current_PreviewTaskVisual = 0.22, SE current_PreviewTaskVisual = 0.007; χ2 = 5.51, p = 0.02); we then performed 7 follow-up pairwise comparisons based on this model (Table S3). We also detected a significant location x choice interaction (F4,15259 = 3.89, p = 0.004); post-hoc analyses showed representations of both current (current_PreviewTaskVisual = 0.22, SE current_PreviewTaskVisual = 0.01; χ2 = 5.46, p = 0.02) and next (next_PreviewTaskVisual = 0.22, SE next_PreviewTaskVisual = 0.01; χ2 = 5.20, p = 0.02) during skip decisions (F4,7289 = 5.50, p < 0.001; Figure 5B; Table S3), versus next (next_PreviewTaskVisual = 0.24, SE next_PreviewTaskVisual = 0.009; χ2 = 13.00, p < 0.001) and previous at a trend level (previous_PreviewTaskVisual = 0.22, SE previous_PreviewTaskVisual = 0.009; χ2 = 3.66, p = 0.06) during stay decisions (F4,7949 = 12.05, p < 0.001; Table S3; Figure 5B); we similarly conducted 7 pairwise comparisons for each of the stay and skip models (Table S3).

Figure 5.

Decision Decoding with the Preview Task Visual Mask

Abbreviations: Non-vid = non-video. (A) Decoding using the Preview Task Visual mask during the decision phase best represents the current and next locations for all trials, collectively. (B) Decoding using the Preview Task Visual mask during the decision phase best represents the current and next locations for skip trials (top), versus the previous and next locations for stay trials (bottom). Probabilities are based on four video and on control (non-video) category); Chance indicated by horizontal black line at 0.2. Error bars reflect within-subject standard errors; asterisks reflect locations with probabilities different than chance (5 follow-up χ2-tests performed per each significant model, . p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001).

We also note that representations were stronger during the first (F4,1647 = 16.00, p < 0.001; Figure S7; Table S4) versus second half of the session (F4,1411 = 2.62, p = 0.03; see Supplemental Materials, Cross-session Shifts in Deliberation).

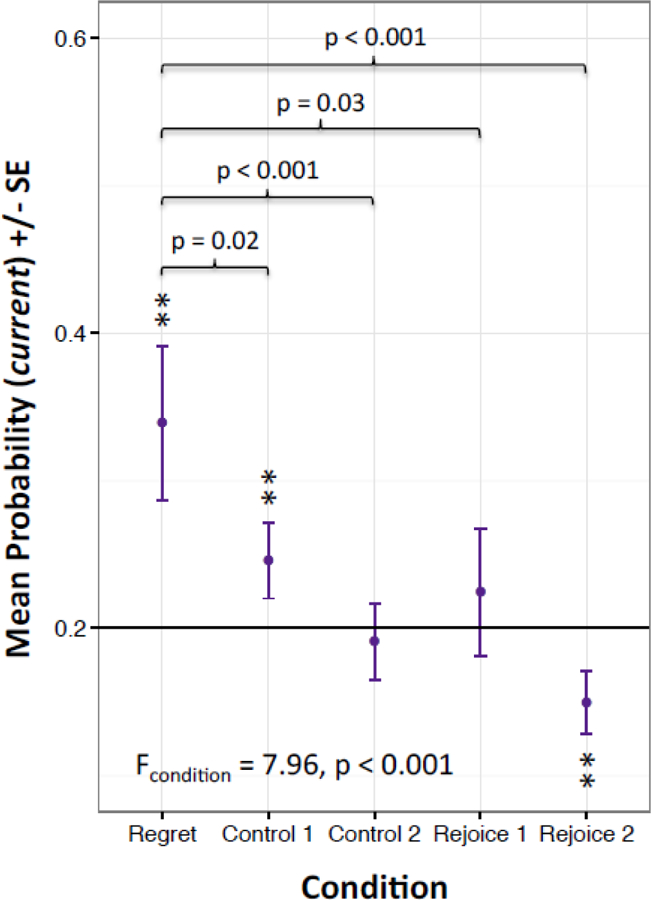

Regret Uniquely Impacts Deliberation While Foraging

The prior analyses suggest that competing representations of past and future outcomes guide an agent’s choice to stay or skip (e.g., on a skip choice subjects may ponder: “do I accept this offer or try my luck at the gallery?”), but to what extent does that agent’s past actions impact deliberation? If we consider time as a limited resource, then trials become interdependent, and past actions may impact future decision-making. To answer this question, we first tested whether past decisions impacted neural representations during the decision time. As shown in Figure S8, rejection of a good offer (value > 0) on the last trial was associated with the strongest representation of the current location, particularly when the subject also chose to skip the current offer (orange box in top left cell). This could suggest that a subject’s realization that they just made an error led to more deliberation about whether they should reject the new offer. Subjects were also slowest when making a skip decision if they had stayed on the last trial (F3,15155 = 40.03, p < 0.001), followed by skip decisions when they had stayed on the last trial (Figure S9; see Supplemental Materials, Decision Times in Response to Sequential Choices).

We hypothesized this sequencing finding was akin to experiences of regret, defined here as the realization that one’s own actions yielded a more unfavorable result, i.e., an alternative action would have led to a preferred outcome (Bell, 1982). More specifically, a regret-inducing scenario occurred when a subject skipped a high-valued offer only to encounter a low-valued offer on the subsequent trial. We thus explored the possibility that humans showed more deliberation following regret (than other serial outcomes) using criteria from Steiner and Redish (2014). Table S5 provides detailed descriptions of regret and the four comparison conditions, where control 1 and control 2 reflect disappointment (i.e., agent encounters an unfavorable offer after making the correct choice on the last trial), and rejoice 1 and rejoice 2 reflect receipt of good offers after skipping the last trial. We used mixed-effects logistic models to assess for between-condition effects (i.e., regret versus controls) for each of the 4 locations plus non-video control (e.g., previous, current, next, opposite, non-video), yielding 5 models. We found that current representations were strongest for regret-inducing scenarios (F4,2084_current = 7.96, p < 0.001; current_PreviewTaskVisual_regret = 0.34, SE current_PreviewTaskVisual_regret = 0.05; χ2 = 7.73, p = 0.005; Figure 6), followed by control 1 (current_PreviewTaskVisual_control1 = 0.25, SE current_PreviewTaskVisual_control1 = 0.03; χ2 = 8.63, p = 0.003). We then tested whether regret representations were greater than each of the 4 other conditions using one-tailed tests, finding that regret representations significantly exceeded each of the other conditions: control 1 (z-ratio = 2.08; p = 0.02, p-adj = 0.03), control 2 (z-ratio = 3.39; p = 0.0003, p-adj = 0.0006 ), rejoice 1 (z-ratio = 1.84; p = 0.03, p-adi = 0.03), and rejoice 2 (z-ratio = 4.51; p = 0.0001, p-adj = 0.0004). Comparatively, neural representations following regret instances were not above chance for any of the other locations (Figure S10); however, we did find overall differences for the opposite and non-video models, with control 1 above chance for the opposite model (opposite_PreviewTaskVisual_control1 = 0.23, SE current_PreviewTaskVisual_control1 = 0.03; χ2 = 4.27, p = 0.04).

Figure 6.

Regret-including Experiences Enhance Deliberation

Decision decoding probabilities from the current location using the Preview Task Visual mask for regret versus the control conditions. Chance indicated by horizontal black line at 0.2. Error bars reflect within-subject standard errors; asterisks reflect locations with probabilities different than chance (5 follow-up χ2-tests performed. ** p < 0.01). Additional p-values reflect one-tailed odds-ratios that compare regret to the four control conditions.

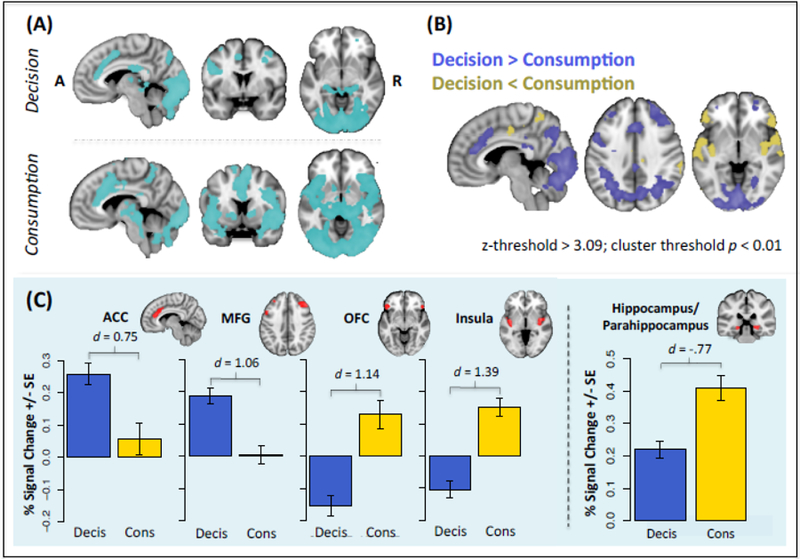

Neural Activation for Difficult Choices

We then investigated which brain areas were associated with difficult choices on the main task. Figure 7A shows that decision-making recruited the ACC, MFG, bilateral hippocampus, PCC, and lingual gyrus (Table S6). Likewise, video viewing after delay recruited the ACC, hippocampus, and visuospatial areas, as well as bilateral portions of the orbitofrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, amygdala, insula, and thalamus; we note that in the case of consumption, these regions may reflect more intensive post-consumption valuation processes rather than greater difficulty (as the subject is long past the decision phase). An intersection mask revealed that both decisions and consumption evoked the ACC, bilateral hippocampus/parahippocampus, and visuospatial areas (Figure S11); follow-up analyses showed that both decisions and video viewing led to increased hippocampal/parahippocampal activation (Figure 7C). While it is possible that signals from consumption were erroneously attributed to decisions (or vice versa) given the sluggish nature of the hemodynamic response and some shorter wait times (Lindquist, Meng Loh, Atlas, & Wager, 2009), we note that subjects did not always elect to view a video on a prior trial and we intentionally introduced jitter between trials (i.e., cost phase shown in Figure 1) to help separate these events.

Figure 7.

Neural Activation Related to Difficult Choice

Abbreviations: Decis = decision; Cons = consumption; ACC = anterior cingulate cortex; MFG = middle frontal gyrus; OFC = orbitofrontal cortex. (A) Activation main effects related to difficult choices during decision-making (top) and consumption (bottom). (B) Contrasts showing differential activation for decision-making and consumption as related to difficult choices. (C) Contrasts reveal which cognitive and sensory areas are associated with difficult choices during decision-making versus consumption (left). Both decision-making and consumption recruited voxels within the hippocampus and parahippocampus (right). Error bars reflect between-subject standard errors.

Lastly, we contrasted choice and video viewing to determine the extent to which challenging offers were associated with different brain structures at different points in the decision process. Here, we observed increased ACC and MFG activation during decision-making, versus increased OFC and posterior insula activation during consumption (Figure 7B and C).

Discussion

Recent theories posit that humans engage in future-oriented thinking during deliberative decision-making (Buckner & Carroll, 2007; Gilbert & Wilson, 2007; Kurth-Nelson, Bickel, & Redish, 2012; Schacter & Addis, 2011). This entails imagining rich and concrete future representations (Peters & Büchel, 2010; Redish, 2016). These processes have been directly observed in rats during foraging decisions (Steiner & Redish, 2014), and yielded important insights as to how an agent’s awareness that they made an error, i.e., experience of regret, could drive episodic simulation during deliberation. Using the Web-Surf Task, a sequential foraging paradigm with real-time costs and rewards, we discovered a set of human decision-making mechanisms indicative of deliberation while foraging. Our unique task design allowed us to differentiate representations of the foreground versus background options as humans cycled between four video categories that appeared in a constant order, but varied trial-to-trial with regards to the specific delay. We used multi-voxel pattern analysis decoding to uncover categorical representations within a category-selective mask that contained key visual regions and found that choices following regret-inducing experiences led to better representations of the current offer.

Our initial decision decoding findings depict overall effects for all trials, and then separately for stay and skip choices. The results suggest the possibility for competing representations when making a choice: we found the best representations of the current and next location during skip trials, versus the representations of the previous and next for stay trials. These initial results diverged somewhat from our expectation that foraging decisions should be more about the upcoming offer (i.e., foreground option) than the alternatives (i.e., background), implying that current representations would exceed the other options. Instead, our results suggest that during skip decisions, subjects waver between whether the current offer is worth it or if they should take their chances with the next offer; this could be explained by slower responses on skip trials (mainly during the first half of the session), suggesting more difficulty in rejecting versus accepting offers. Comparatively, background offers (i.e., previous, next) were better depicted on stay trials, which may point to broader task representations coming on line. These choice-specific differences may also be understood in terms of default foraging behaviors, where the default action is to engage with an offer (while continued foraging requires an over-ride of the default option; Kolling, Behrens, Mars, & Rushworth, 2012; Sweis, Abram, et al., 2018; Sweis, Thomas, et al., 2018). Our data suggest that the default option in our task would be to stay and the non-default to skip. It is possible that on skip trials, stronger current and next representations emerge as the subject overrides the default (and more automatic) action; this effect may be even more amplified in situations where the subject elected to skip after having just skipped a high-valued offer (Figure S8).

We also found that decoding of the different locations was more clearly distinguished in the first than the second half of the session (Figure S7). Similar to our reaction time results (Figure 2A), we can conceptualize this finding as a shift from a deliberative to more rule-based approach, whereby earlier trials required more thoughtfulness. Subjects may think more deeply on earlier trials, i.e., reflecting on whether a particular offer is “worth it,” before thresholds are well-established. This finding also fits with the hypothesis that repeated trials with the same (or similar) questions can yield the development of “associations.” Subjects can then draw from the association while making a decision, rather than needing to retrieve an episode (Zentall, 2010). Perhaps as subjects gain experience on the task, they form associations with the category and delays that limit their reliance on episodic simulation processes.

A more nuanced assessment of our data also highlighted the need to account for how past actions influence deliberative processes. More specifically, we observed the strongest representations of the current option when a subject rejected a good offer only to encounter a low-valued offer; this suggests one’s awareness that an alternative action would have been better (i.e., one’s experience of regret; Bell, 1982) led to more thoughtfulness about the current option. This regret effect was greater than the disappointment control conditions, where a subject encountered an unfavorable outcome but had not made an error (though we note that one of these controls had overall probabilities above chance, suggesting that deliberation may generally be needed for evaluating low-valued offers).

Mental Time Travel in the Context of Reinforcement Learning

At least three cases have been suggested for modeling episodic simulation. These include deliberative model-based learning where a subject uses an internal map to guide goal-directed behaviors, reflexive model-free strategies where learning occurs outside of a model and instead on a trial-and-error basis, and a hybrid of model-based and model-free approaches (Dyna-Q) that utilizes off-line replays, i.e., replays when the subject is not moving (Cazé, Khamassi, Aubin, & Girard, 2018; Redish, 2013; Schacter & Addis, 2007a; Suddendorf, 2013). Critically, model-based learning involves using past memories to construct future possibilities, which is most likely to occur during decision making and thus most likely what we are observing in the current task. In comparison, reactivation of representations driving model-free strategies, which involve updating expectations after recent feedback are more likely to occur after consumption (e.g., phasic dopamine signals during learning; Foster & Wilson, 2006; Montague, Dayan, & Sejnowski, 1996; Schultz, Dayan, & Montague, 1997), while Dyna-Q learning likely occurs off-line (Cazé et al., 2018; Adam Johnson & Redish, 2005). And as can be seen in Figure 7C, hippocampus can be present in both decision and consumption, i.e., providing prospection during decisions and re-activation during consumption.

Prospection versus Retrospection versus Perception

Our results for episodic simulation during deliberation can also be framed in terms of prospection, retrospection, and perception (Schacter et al., 2008), a framework that in many ways map onto the reinforcement learning models described above. Episodic prospection, or the anticipation of future events, hinges on a system that can flexibly recombine elements of past experiences to guide decision-making (i.e., model-based learning; Redish, 2016; Schacter and Addis, 2007a, 2007b; Zeithamova et al., 2012). Here we found the strongest representations of the subsequent location (i.e., next) in several instances (Figure 5), with the exception of regret scenarios (Figure 6). This suggests subjects engaged in future-oriented thinking while deliberating at the choice point. At least two features of our analysis support our theory: (1) subjects had more complete knowledge of the current offer (i.e., they knew the type of video and delay) compared to the subsequent offer (i.e., they knew the type of video but not delay), and (2) we trained our classifier on a separate but categorically-similar set of videos, meaning that subjects did not encounter identical video rewards during the training and test phases. Because subjects did not have complete knowledge of the subsequent offer (i.e., the delay was unknown and the specific video was always novel), we suspect that subjects utilized imaginative processes shaped by prototypical information (e.g., by imagining what a typical instance of what a category event would be; Kane, Van Boven, & Mcgraw, 2012): “what offer might be available at the next gallery? How might I respond to a high versus low delay for that kind of video? Will I enjoy another kitten video as much as the last kitten video?” The notion of episodic prospection during deliberation also fits with recent findings that model-based choices involve prospective neural signals (Doll et al., 2015).

In contrast to prospection, retrospection (or episodic memory) entails the use of past memories to execute current decisions (Zentall, 2010). Many researchers argue that imaging the future depends on recalling the past (Addis, Wong, & Schacter, 2008; Busby & Suddendorf, 2005; Kwan, Carson, Addis, & Rosenbaum, 2010; Mullally & Maguire, 2014). Recalling the past and imagining the future also evoke similar neural processes (Addis, Wong, & Schacter, 2007; Buckner & Carroll, 2007b; Schacter et al., 2012), and in the visual-spatial context, both visual memory and visual imagery may depend on similar regions, including occipital-temporal sensory areas (Slotnick, Thompson, & Kosslyn, 2012). Compared to prospection, retrospection may be more akin to retrieving rather than reconstructing historical information (Kane et al., 2012). Given that subjects encountered a range of offers within each category (i.e., delays were random), deliberation on this task seems more likely to reflect flexible reconstruction processes than solely a reactivation or replay of past experiences.

Our findings regarding regret-inducing situations indicated the strongest representations of the current (versus next) location. One might argue this finding is not evidence of prospection but instead perception, i.e., the mental representation of a current event is considered perception (Gilbert & Wilson, 2007). However, in our study we tested for deliberation at the choice point where subjects had a cue indicating the type of video and delay but were not actually yet experiencing the reward. This could mean that the representation of the current while at the choice point is still a form of episodic prospection (as one is imagining their experience of a future reward available after enduring some cost); though we note that simulation of future events is supported by some of the same underlying processes that support perception (Kosslyn, Ganis, & Thompson, 2001). We suspect that decoding during the consumption phase, when subjects were actually experiencing video rewards, may be more akin to perception.

Prospection and Planning

Prospection is an umbrella term that encompasses a range of future-oriented cognitions related to episodic simulation, including planning and remembering intentions (Schacter et al., 2008; Szpunar, Spreng, & Schacter, 2014). Planning broadly entails the identification and organization of steps needed to achieve a specific goal, while episodic planning refers to the identification and sequencing of steps towards a specific autobiographical future event (Spreng, Gerlach, Turner, & Schacter, 2015). Autobiographical planning, in particular, draws from self-relevant memory and goal-directed planning processes, and the planning of specific autobiographical outcomes may evoke the same brain regions involved in prospection and goal-directed cognition (Szpunar et al., 2014). However, it is worth noting that contemplating future plans can actually create a cost to ongoing performance (Marsh, Hicks, & Cook, 2006; R. E. Smith, 2003): that is, actively maintaining future intentions can deplete current attentional resources. One way to reduce performance interference is by associating the intention with a specific future context. Gollwitzer calls this process “implementation intentions” or plans that connect intentions with specific anticipated events, e.g., “if faced with a delay above 15 on a bike accident video, I will skip” versus broader goal intentions like “I intend to skip many of the bike accident videos” (Gollwitzer, 1999). It is possible that implementation intentions enhance performance because an intention is linked with a specific mental representation about the future that can later cue that intention (Schacter et al., 2008). Taken together, prospection and planning may intersect in the realm of implementation intentions. We theorize that subjects on our task formulated these plans across the session, evidenced by downward shifts in reaction times and diminished mental representations at the decision time.

Comparisons with Rodent Literature

We detected several behavioral and neural cross-species parallels with respect to deliberative decision-making: First, reaction-time patterns in humans were analogous to rodent vicarious trial and error (VTE) behaviors during Restaurant Row (Schmidt, Duin, & Redish, n.d.; Steiner & Redish, 2014; Sweis, Thomas, et al., 2018), as indicated by longer reaction times on offers just above threshold, i.e., more difficult choices. This pattern is also analogous to the slower response latencies observed when humans make decisions with uncertain outcomes (Satterthwaite et al., 2007), which fits with notions that VTE reflects the uncertainty that drives deliberation (Redish, 2016). Though we again note that this pattern was more pronounced in the first half of the session for our human subjects.

Second, hippocampal task-based activation scaled with choice difficulty during decision-making and consumption, revealing a novel neural signature of deliberation that translates across species. Difficult choices also recruited the ACC and MFG (including the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex [dlPFC]) more strongly during the decision phase. These areas are involved in cognitive control and conflict monitoring, and might respond to the uncertainty and error potential of difficult trials (Botvinick, Cohen, & Carter, 2004); previous research also implicates the ACC in decision difficulty during a foraging task (Shenhav et al., 2014), and in tracking value in an uncertain reward environment (Behrens, Woolrich, Walton, & Rushworth, 2007). Moreover, the MFG is theorized to initiate VTE (Redish, 2016; Schmidt et al., n.d.; Wang et al., 2015). This follows from rodent findings that disrupting hippocampal representations actually increases VTE, making the hippocampus an unlikely candidate for initiating the VTE process (Bett, Murdoch, Wood, & Dudchenko, 2015). Instead, the rodent prelimbic cortex, arguably homologous to aspects of human PFC, might initiate this process, given its role in outcome-dependent decisions and influence on goal-directed activity in the hippocampus (Ito, Zhang, Witter, Moser, & Moser, 2015; Killcross & Coutureau, 2003; Spellman et al., 2015). Findings from nonhuman primates that the dlPFC generates action plans prior to action execution further support this theory (Mushiake, Saito, Sakamoto, Itoyama, & Tanji, 2006). Compared to decision-making, consumption led to more activation in the lateral orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) for difficult trials. This aligns with rodent findings that implicate the OFC in post-decisional outcome evaluation (Stott & Redish, 2014). Taken together, VTE may represent a cross-species mechanism that underlies deliberation during foraging decisions.

One notable cross-species divergence comes from our regret results. In humans, we found that regret instances led to greater representation of the current location, whereas Steiner and Redish (2014) found that in rodents such instances were linked to better representation of the previous location, i.e., the counterfactual offer. One possibility is that experiences of regret foster more present-focused deliberative processes in humans, whereby humans become more attentive to the current decision.

Conclusions

The current study employed a sequential experiential foraging paradigm to evaluate episodic simulation during deliberative decision-making in humans. Our results revealed that visual cortices represented the current or foreground offer during the decision phase, particularly following regret-inducing experiences. Furthermore, humans demonstrated comparable behavioral and neural signatures of VTE, which could suggest a common mechanism of decision-making that translates across humans, rodents, and monkeys.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the TRiCAM lab for assistance with data collection, with special thanks to Yizhou Ma and Amanda Reuter. We also thank both the TRiCAM and Redish labs for providing helpful discussion. This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) to Samantha Abram (F31-DA040335) and A. David Redish (R01-DA030672), grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) to A. David Redish (R01-MH112688; R01-MH080318), funds from the German federal state of Saxony-Anhalt and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), Project: Center for Behavioral Brain Sciences to Michael Hanke, as well as a CLA Brain Imaging project grant (University of Minnesota) to Angus MacDonald. Writing of this manuscript was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations, the Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment, and the Department of Veterans Affairs Sierra-Pacific Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Open Practices Statement

The data and materials for all experiments are available upon request. None of the experiments were pre-registered.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Average absolute (mean = 0.57 mm) and relative (mean = 0.09 mm) head displacement.

A mixed-effects logistic model has a negative slope, indicative of more skip choices across the session (β = −0.005, p < 0.001).

The first three subjects were excluded from this analysis as they completed a version of the Preview Task with half the number of trials; this resulted in a sample of N=22.

This approach prevents an outlier from dragging down the global mean.

Two chunks constituted 40% of the data, as the Preview Task was separated into five chunks total.

Post-hoc Tukey HSD analyses revealed trend-level differences for bike accidents > dance (p = 0.08) and bike accidents > landscapes (p = 0.08)

Of note, probabilistic masks of the orbitofrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens, i.e., the regions investigated by Steiner and Redish (2014), showed poor decoding performance (Figure S6), which could represent a possible cross-species divergence in the neural mechanisms involved in foraging.

AICPreviewTaskMaskModel =6356.5, logLikelihoodPreviewTaskMaskModel = −3171.2, deviance PreviewTaskMaskModel =6342.5; AICPreviewTaskVisualMaskModel = −3343.5, logLikelihoodPreviewTaskVisualMaskModel = 1678.2, deviance PreviewTaskVisualMaskModel = −3357.5, p < 0.001

References

- Abram SV, Breton Y-A, Schmidt B, Redish AD, & MacDonald AW (2016). The Web-Surf Task: A translational model of human decision-making. Cognitive, Affective and Behavioral Neuroscience, 16(1). 10.3758/s13415-015-0379-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addis DR, Wong AT, & Schacter DL (2007). Remembering the past and imagining the future: common and distinct neural substrates during event construction and elaboration. Neuropsychologia, 45(7), 1363–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addis DR, Wong AT, & Schacter DL (2008). Age-related changes in the episodic simulation of future events. Psychological Science, 19(1), 33–41. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02043.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson JLR, Skare S, & Ashburner J (2003). How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: Application to diffusion tensor imaging. NeuroImage, 20(2), 870–888. 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00336-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Maechler Martin, & Walker S (2016). Package “lme4”: Linear Mixed-Effects Models using “Eigen” and S4. CRAN Repository, 1–113. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens TEJ, Woolrich MW, Walton ME, & Rushworth MFS (2007). Learning the value of information in an uncertain world. Nature Neuroscience, 10(9), 1214–1221. 10.1038/nn1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell DE (1982). Regret in Decision Making under Uncertainty. Operations Research, 30(5), 961–981. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, & Hochberg Y (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B 10.2307/2346101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bett D, Murdoch LH, Wood ER, & Dudchenko PA (2015). Hippocampus, Delay discounting, And vicarious trial-and-error. Hippocampus, 25(5), 643–654. 10.1002/hipo.22400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick MM, Cohen JD, & Carter CS (2004). Conflict monitoring and anterior cingulate cortex: An update. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 10.1016/j.tics.2004.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, & Carroll DC (2007a). Self-projection and the brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(2), 49–57. 10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, & Carroll DC (2007b). Self-projection and the brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11, 49–57. 10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busby J, & Suddendorf T (2005). Recalling yesterday and predicting tomorrow. Cognitive Development, 20(3), 362–372. 10.1016/j.cogdev.2005.05.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Camerer C (1997). Taxi drivers and beauty contests. Engineering & Science, 60(1), 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Cazé R, Khamassi M, Aubin L, & Girard B (2018). Hippocampal replays under the scrutiny of reinforcement learning models. Journal of Neurophysiology, 120(6), 2877–2896. 10.1152/jn.00145.2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charnov EL (1976). Optimal Foraging, the Marginal Value Theorem. Theoretical Population Biology, 9(2), 129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll BB, Duncan KD, Simon DA, Shohamy D, & Daw ND (2015). Model-based choices involve prospective neural activity. Nature Neuroscience, 18(5), 767–772. 10.1038/nn.3981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster DJ, & Wilson MA (2006). Reverse replay of behavioural sequences in hippocampal place cells during the awake state. Nature, 440(7084), 680–683. 10.1038/nature04587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DT, & Wilson TD (2007). Prospection: Experiencing the Future. Science, 317(5843), 1351–1354. 10.1126/science.1144161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer PM (1999). Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. American Psychologist, 54(493–503). 10.1037/0003-066X.54.7.493 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grill-Spector K, & Weiner KS (2014). The functional architecture of the ventral temporal cortex and its role in categorization. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 10.1038/nrn3747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanke M, Halchenko YO, Sederberg PB, Hanson SJ, Haxby JV, & Pollmann S (2009). PyMVPA: A python toolbox for multivariate pattern analysis of fMRI data. Neuroinformatics, 7(1), 37–53. 10.1007/s12021-008-9041-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassabis D, Kumaran D, Vann SD, & Maguire EA (2007). Patients with hippocampal amnesia cannot imagine new experiences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(5), 1726–1731. 10.1073/pnas.0610561104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassabis D, & Maguire EA (2007). Deconstructing episodic memory with construction. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(7), 299–306. 10.1016/j.tics.2007.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby JV, Guntupalli JS, Connolly AC, Halchenko YO, Conroy BR, Gobbini MI, … Ramadge PJ (2011). A common, high-dimensional model of the representational space in human ventral temporal cortex. Neuron, 72(2), 404–416. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.08.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby JV, Gobbini MI, Furey ML, Ishai A, Schouten JL, & Pietrini P (2001). Distributed and Overlapping Representations of Faces and Objects in Ventral Temporal Cortex. Science, 293(5539), 2425–2430. 10.1126/science.1063736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffer LD, Bobashev G, & Morris RJ (2009). Researching a local heroin market as a complex adaptive system. American Journal of Community Psychology, 44(3), 273–286. 10.1007/s10464-009-9268-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito HT, Zhang S-J, Witter MP, Moser EI, & Moser M-B (2015). A prefrontal–thalamo–hippocampal circuit for goal-directed spatial navigation. Nature, 522(7554), 50–55. 10.1038/nature14396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJ, Woolrich MW, & Smith SM (2012). FSL. NeuroImage 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A, & Redish AD (2005). Hippocampal replay contributes to within session learning in a temporal difference reinforcement learning model. Neural Networks, 18(9), 1162–1171. 10.1016/j.neunet.2005.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A, & Redish AD (2007). Neural Ensembles in CA3 Transiently Encode Paths Forward of the Animal at a Decision Point. Journal of Neuroscience, 27(45), 12176–12189. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3761-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane J, Van Boven L, & Mcgraw AP (2012). Prototypical prospection: Future events are more prototypically represented and simulated than past events. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42, 352–362. 10.1002/ejsp.1866 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan R, Schuck NW, & Doeller CF (2017). The Role of Mental Maps in Decision-Making. Trends in Neurosciences 10.1016/j.tins.2017.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killcross S, & Coutureau E (2003). Coordination of actions and habits in the medial prefrontal cortex of rats. Cerebral Cortex, 13(4), 400–408. 10.1093/cercor/13.4.400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolling N, Behrens TEJ, Mars RB, & Rushworth MFS (2012). Neural Mechanisms of Foraging. Science, 336, 95–98. 10.1126/science.1216930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosslyn SM, Ganis G, & Thompson WL (2001). Neural foundations of imagery. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2, 635–642. 10.1038/35090055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnapuram B, Carin L, Figueiredo MAT, & Hartemink AJ (2005). Sparse multinomial logistic regression: Fast algorithms and generalization bounds. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 27(6), 957–968. 10.1109/TPAMI.2005.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth-Nelson Z, Bickel W, & Redish AD (2012). A theoretical account of cognitive effects in delay discounting. European Journal of Neuroscience, 35(7), 1052–1064. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08058.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan D, Carson N, Addis DR, & Rosenbaum RS (2010). Deficits in past remembering extend to future imagining in a case of developmental amnesia. Neuropsychologia, 48(3179–3186). 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist MA, Meng Loh J, Atlas LY, & Wager TD (2009). Modeling the hemodynamic response function in fMRI: efficiency, bias and mis-modeling. NeuroImage, 45(1 Suppl), S187–S198. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.10.065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh RL, Hicks JL, & Cook GI (2006). Task interference from prospective memories covaries with contextual associations of fulfilling them. Memory and Cognition, 34(5), 1037–1045. 10.3758/BF03193250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague PR, Dayan P, & Sejnowski TJ (1996). A framework for mesencephalic dopamine systems based on predictive Hebbian learning. The Journal of Neuroscience, 16(5), 1936–1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullally SL, & Maguire EA (2014). Memory, imagination, and predicting the future: A common brain mechanism? Neuroscientist, 20, 220–234. 10.1177/1073858413495091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mushiake H, Saito N, Sakamoto K, Itoyama Y, & Tanji J (2006). Activity in the Lateral Prefrontal Cortex Reflects Multiple Steps of Future Events in Action Plans. Neuron, 50(4), 631–641. 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman KA, Polyn SM, Detre GJ, & Haxby JV (2006). Beyond mind-reading: multi-voxel pattern analysis of fMRI data. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 10.1016/j.tics.2006.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson J, Naselaris T, Holmes EA, & Kosslyn SM (2015). Mental Imagery: Functional Mechanisms and Clinical Applications. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 10.1016/j.tics.2015.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce JW (2009). Generating Stimuli for Neuroscience Using PsychoPy. Frontiers in Neuroinformatics, 2, 10 10.3389/neuro.11.010.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira F, Mitchell T, & Botvinick M (2009). Machine learning classifiers and fMRI: a tutorial overview. NeuroImage 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J, & Büchel C (2010). Episodic Future Thinking Reduces Reward Delay Discounting through an Enhancement of Prefrontal-Mediotemporal Interactions. Neuron, 66(1), 138–148. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy L, Tsuchiya N, & Serre T (2010). Reading the mind’s eye: Decoding category information during mental imagery. NeuroImage, 50(2), 818–825. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.11.084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redish AD (2013). The Mind Within the Brain: How We Make Decisions and How Those Decisions Go Wrong (1st ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Redish AD (2016). Vicarious trial and error. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 17(3), 147–159. 10.1038/nrn.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riefer PS, Prior R, Blair N, Pavey G, & Love BC (2017). Coherency-maximizing exploration in the supermarket. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(1), 0017 10.1038/s41562-016-0017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satterthwaite TD, Green L, Myerson J, Parker J, Ramaratnam M, & Buckner RL (2007). Dissociable but inter-related systems of cognitive control and reward during decision making: Evidence from pupillometry and event-related fMRI. NeuroImage, 37(3), 1017–1031. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.04.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacter DL, & Addis DR (2007a). Constructive memory: The ghosts of past and future. Nature 10.1038/445027a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacter DL, & Addis DR (2007b). The cognitive neuroscience of constructive memory: remembering the past and imagining the future. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 362(1481), 773–786. 10.1098/rstb.2007.2087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacter DL, & Addis DR (2011). On the Nature of Medial Temporal Lobe Contributions to the Constructive Simulation of Future Events. In Predictions in the Brain: Using Our Past to Generate a Future (pp. 1245–1253). 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195395518.003.0024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacter DL, Addis DR, & Buckner RL (2008). Episodic simulation of future events: Concepts, data, and applications. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1124, 39–60. 10.1196/annals.1440.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacter DL, Addis DR, Hassabis D, Martin VC, Spreng RN, & Szpunar KK (2012). The Future of Memory: Remembering, Imagining, and the Brain. Neuron, 76(4), 677–694. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt BJ, Duin A., & Redish AD (n.d.). Disrupting the medial prefrontal cortex alters hippocampal sequences during deliberative decision making. Journal of Neurophysiology [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schultz W, Dayan P, & Montague PR (1997). A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science, 275, 1593–1599. 10.1126/science.275.5306.1593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenhav A, Straccia MA, Cohen JD, & Botvinick MM (2014). Anterior cingulate engagement in a foraging context reflects choice difficulty, not foraging value. Nature Neuroscience, 17, 1249–1254. 10.1038/nn.3771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotnick SD, Thompson WL, & Kosslyn SM (2012). Visual memory and visual mental imagery recruit common control and sensory regions of the brain. Cognitive Neuroscience, 3, 14–20. 10.1080/17588928.2011.578210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EA (1991). Inujjuamiunt Foraging Strategies: Evolutionary Ecology of an Arctic Hunting Economy New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Smith KS, & Graybiel AM (2013). A dual operator view of habitual behavior reflecting cortical and striatal dynamics. Neuron, 79(2), 361–374. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.05.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RE (2003). The Cost of Remembering to Remember in Event-Based Prospective Memory: Investigating the Capacity Demands of Delayed Intention Performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning Memory and Cognition, 29(3), 347–361. 10.1037/0278-7393.29.3.347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spellman T, Rigotti M, Ahmari SE, Fusi S, Gogos JA, & Gordon JA (2015). Hippocampal–prefrontal input supports spatial encoding in working memory. Nature, 522(7556), 309–314. 10.1038/nature14445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreng RN, Gerlach KD, Turner GR, & Schacter DL (2015). Autobiographical planning and the brain: Activation and its modulation by qualitative features. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 27(11), 2147–2157. 10.1162/jocn_a_00846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner AP, & Redish AD (2014). Behavioral and neurophysiological correlates of regret in rat decision-making on a neuroeconomic task. Nature Neuroscience, 17, 995–1002. 10.1038/nn.3740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens DW (2008). Decision ecology: Foraging and the ecology of animal decision making. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience, 8(4), 475–484. 10.3758/CABN.8.4.475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stott JJ, & Redish AD (2014). A functional difference in information processing between orbitofrontal cortex and ventral striatum during decision-making behaviour. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369, 20130472–20130472. 10.1098/rstb.2013.0472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suddendorf T (2013). The Gap: The Science of What Separates Us from Other Animals New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, van Erp TGM, Thompson PM, Bearden CE, Daley M, Kushan L, … Cannon TD (2009). Elucidating a Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Based Neuroanatomic Biomarker for Psychosis: Classification Analysis Using Probabilistic Brain Atlas and Machine Learning Algorithms. Biological Psychiatry, 66(11), 1055–1060. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweis BM, Abram SV, Schmidt BJ, Seeland KD, MacDonald AW, Thomas MJ, & Redish AD (2018). Sensitivity to “sunk costs” in mice, rats, and humans. Science, 361, 178–181. 10.1126/science.aar8644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweis BM, Redish AD, & Thomas MJ (2018). Prolonged abstinence from cocaine or morphine disrupts separable valuations during decision conflict. Nature Communications, 9(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweis BM, Thomas MJ, & Redish AD (2018). Mice learn to avoid regret. PLoS Biology, 16(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szpunar KK, Spreng RN, & Schacter DL (2014). A taxonomy of prospection: Introducing an organizational framework for future-oriented cognition: Fig. 1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(52), 18414–18421. 10.1073/pnas.1417144111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman EC (1939). Prediction of vicarious trial and error by means of the schematic sowbug. Psychological Review, 46(4), 318–336. 10.1037/h0057054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tong F, & Pratte MS (2012). Decoding Patterns of Human Brain Activity. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 483–509. 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meer MAA, Johnson A, Schmitzer-Torbert NC, & Redish AD (2010). Triple dissociation of information processing in dorsal striatum, ventral striatum, and hippocampus on a learned spatial decision task. Neuron, 67(1), 25–32. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]